THE FUTURE AUSTRALIAN DESIGN ETHOS

A biography about the life and legacy of Ted E.H. Farmer

Advanced Topics in Australian Architecture : ARCH9113

Antony Fenhas : 490480496

Introduction Allison Page & Paul Memmott

New South Wales’ invisible bureaucratic architecture, often repurposed, reused, or built around until near unrecognition, they are never too far from view. Remnants, in their hundreds scattered throughout the state of the golden age from one of the world’s last standing architectural bureaucracies, the NSW Government Architect’s Office.

A key figure in the story of this longstanding colonial branch is that of Ted E.H. Farmer, NSW’s 16th Government Architect, holding office from 1958 to 1973, a period acknowledged as the branch’s ‘golden era’ of design. Born in Perth, Western Australia in 1909, the only child of Herbert Farmer a public servant, and Alice May1. His parents had separated before his first birthday, Whereby Farmer and his mother moved to Melbourne to live with his maternal grandmother and maiden aunts. He was educated at the Melbourne Grammar School, whereby the school placed a strong emphasis on classical literature and the humanities, possibly one of the earlier influences on Farmer from a young age. Upon completing his higher educational studies, Farmer spent a year abroad with his family before beginning his tertiary education in architecture, at the University of Melbourne.

At that time of Farmer’s studies, the faculty did not have a Dean of Architecture, however the Dean of engineering who acted as the Ex-Officio dean of architecture is quoted saying – “and the Architectural students were subjected to a most rigorous science-based course for three years while doing architectural subjects at night classes”2. It is no surprise then seeing this ‘rigorous science-based course’ shaping Ted Farmer’s deep understanding of building integrity through

1

“E. H. (Edward Herbert) Farmer - papers, 1825-1996, including papers of the Farmer and Thistlethwaite families, together with letters of John Le Gay Brereton, 1901-1933,” State Library of NSW Archives, Accessed April 13, 2022, https://archival.sl.nsw.gov.au/Details/archive/110330524

2 Russel C. Jack, “The Works Of The NSW Government Architect’s Branch – 1958-1973” (M.Arch Degree Thesis, The University of NSW, 1980)

honest expression of structure, seen in his future career and designs. It is through his studies at the University of Melbourne where Farmer first met Leighton Irwin, who ran the design atelier at the university which farmer attended at night. First his educator, then later his employer, Ted Farmer joined the firm of Leighton and Co. in 1934 prior to his graduation, often working through the day at the firm and studying at night. The firm specialised in the design of hospitals throughout Melbourne, working on a number of hospitals of significant importance, leading to Farmer’s first exposure to public architecture. The director, Leighton Irwin studied European Modernism with Arthur Stephenson, another significant Australian architect, where after serving in the army during WW1, he trained at the Architectural Association School in London. Irwin’s mentoring to the young Ted Farmer encouraged aesthetic experimentation and a strong focus on construction detailing, lessons that remained with farmer throughout his career as he pushed for the importance of architectural detailing and structural honesty seen later in his Government Architect role.

In 1936, Farmer was transferred from Melbourne to singlehandedly open and run Leighton Irwin’s Sydney Office without even a secretary to maintain admin duties. This was no easy feat undertaking this on his own relatively early in his career. He is quoted saying in his farewell

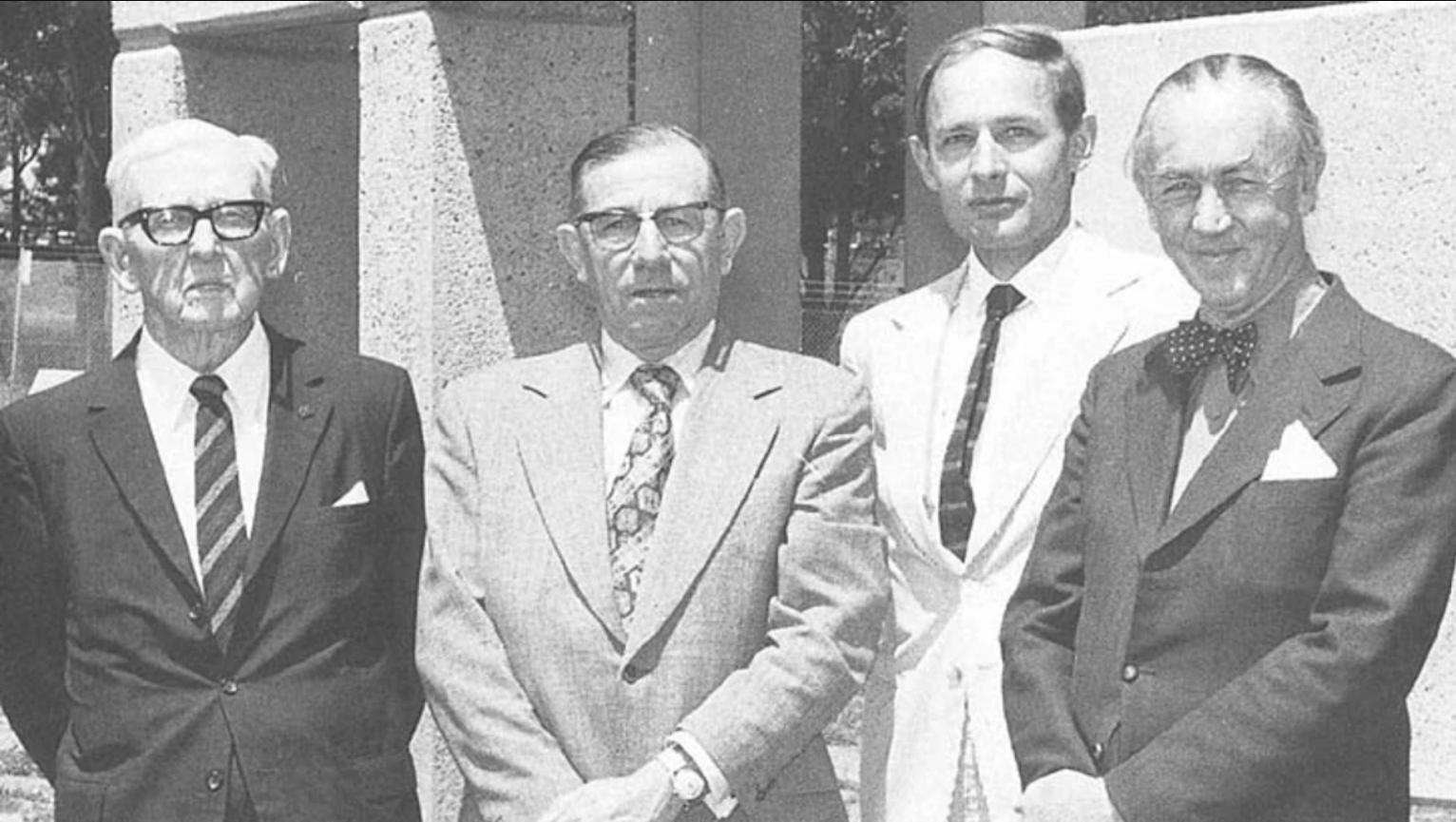

The Design Room Architects. (In order from left to right): Cobden Parkes, Charles Weatherburn, Peter Webber and Ted Farmer. Photographer Unknown

The Design Room Architects. (In order from left to right): Cobden Parkes, Charles Weatherburn, Peter Webber and Ted Farmer. Photographer Unknown

speech to his GANSW staff in 1973, “This had been a singlehanded effort in which I was everything from typist to principal, from design architect to fighting with contractors and it was a tough life; so tough that I left it and joined the Department after three years of struggling with it at much personal cost.”3 In 1939, Farmer graduated from the University of Melbourne with a degree in Architecture, and after 3 years of running the Sydney office, he resigned from Leighton and Co.’s firm to begin his career at the Government Architect’s office of NSW. This departure from private practice was instigated by two main factors, the first being the wide range of building types and experiences that the Government Architects office branch could offer, where he could continue his work with hospital design; the second being his dissatisfaction with working in the private sector, saying “because I am not a salesman and I am afraid that a private architect has got to be a salesman.”4 His leave from private practice however was not bitter, where Farmer is quoted multiple times expressing his respect for Irwin and his teaching, saying “I admired and still admire Irwin’s Hospital design[s]... Which had a lightness, a grace and humanity about them.”5

It is this grace and humanity which can clearly be seen driving Farmer’s design philosophy throughout his career.

The Branch

Upon joining the NSW government Architect’s Office, Farmer’s ideals and desires were to improve the environment for all, not just the individual client. This was well suited for a role at the Government Architect’s branch as their main programs undertaken varied greatly, from schools, hospitals, community centres, to police stations, and court houses. The Government office that Farmer joined at that time however was not the same as one he retired from 34 years later. The branch at that time was largely conservative6, where architecture awards were not applied for, and controlled by bureaucratic order of seniority. Describing his seniors in his farewell speech as

“They seemed to me funny old men living in a kind of ancient Public Service fog... The whole show was based on established precedent, immutable procedures, avoidance of responsibility and anything for a placid and uneventful life.”7

To fully understand and appreciate the impact Ted Farmer had on the branch by the end of his career, one must first delve into the operations of the Government Architect’s Office at the time leading up to Farmer’s appointment. During the 40’s and 50’s after the war the GA’s office was not

an attractive place to work for students and architects at the time. The work produced by the branch was seen as rigid and institutional, producing low quality work that was out of touch with contemporary architectural ideas of the time. This was largely due to the lack of enthusiastic and inspired architects being employed at the department at the time, which created a cycle that deterred young, creative, and enthusiastic architects.

Fisher Library, University of Sydney, 1963. Photographer Unknown. Courtesy of the State Library of NSW

It was not until the time of Harry Rembert, the senior design architect under the Government Architect Cobden Parkes in the late 40’s that the branch saw radical change that brought it new life. The office introduced the traineeship program in 1948, which would seek out school leavers looking to study architecture, interview and select one each year. These trainees would then be supported financially through their studies, including their university fees and a small living allowance, in return the students would thus be bonded to the department for 5 years upon graduation, as well as working at the office during semester holidays. This program proved to be a great success, where in 1948 there were three applicants for the role, and by the end of the 1960’s, 1500 school leavers had applied for 12 available positions. This thus not only saw young creative designers enter the department to bring in new life, but it saw the growth of the elite ‘Design Room’ architects which came up through the trainee program to become the branch’s most influential designers. Formed in 1952 by Rembert, the ‘Design Room’ consisted of a group of architects nicknamed the ‘Young Turks’ which included Peter Hall, Ken Wooley, and G.P. Webber. It is without doubt that without the creativity and passion of the ‘Young Turks’ alongside the leadership of Ted Farmer, the branch may have never reached it’s great achievements in the late 60’s.

Farmer at the GAO

Joining the branch in 1939 at the age of 30, Farmer was one of the younger designers to work in Rembert’s ‘Design Room’, alongside Ken Wooley, Michael Dysart, Peter Hall and others significant architects of the time. Farmer’s extensive skill and interest in hospital design gained from his years working for Leighton Erwin earned him his appointment as charge of hospital

work in the mid 1950’s. At the time, Farmer and his colleagues in the design room were heavily influenced by Scandinavian architecture and modernism, where architects such as Alvar Alto played a huge role in this influence. Their designs thus carried a poetic expression of structure, an emphasis on local materials, and an intention to build on context. The goal was to create architecture that evokes a sense of place, not just stripped, functionalist, machine aesthetic to keep up with the Modernist international style8. This clearly aligned with Farmer’s humanistic concept of design, where he strongly believed that design solutions must go beyond form follows function but have a guiding and influential role in communities. Later in his career, Farmer was to write an article on his branch’s position in the community, and outline his design philosophy, where his passion for structure can be seen, and goal of a humane architecture9. Ted Farmer’s competence and passion in his role at the branch was recognised by those around him. When it came time for Cobden Parkes to retire, Harry Rembert had preferred not to be considered for the role due to his ill health at the time. Parkes was then eager for Farmer to take over his role, whereby he was selected for the Government Architect position over five more senior contenders. Thus becoming the state’s 16th Government Architect in 1958, holding the position for 15 years.

Upon being appointed as Government Architect, Ted Farmer had a new attitude of how things should run opposed to the branch under Parke’s time, from entering architectural awards to appointments, and separation of drawing rooms. Ted Farmer retained the design room, working alongside the group of remarkable architects to produce some of the branch’s most notable projects. Immediately upon taking up the new role, he saw a number of issues that he believed hindered the office from reaching its full potential, as well as coping with the large and varied workload to be undertaken. Believing if the office was to achieve his great ambitions of producing notable first-class work, change would have to come to the bureaucratic organisation of the time. He

Penant Hills High School, 1967. Photo: Max Dupain & Associates

Architects’ drafting office during construction of the Sydney Opera House, 1963. Photo: Don Mcphedran saw numerous good architects in low positions where their talent was being wasted, denied promotions due to the bureaucratic order of seniority and rigidity of the office. Another major issue was the fragmentation of the office, whereby detailing was separated from documentation, as well as the design offices. In addition, he could not tolerate the distance between the architects and the consultant engineers, thus preventing coordination and mutual interchange of ideas, between the various architecture drawing rooms as well as the engineers. Rembert and the former Government Architect Parkes harboured these mutual concerns but were however unable at the time to undertake radical changes to the branch. Farmer then undertook combating the bureaucratic order, making appointments, and promoting architects in which he saw potential. To make these changes was unusual and several appeals at the time by those displaced or bypassed were made, however Farmer’s determination surpassed the objections raised. Farmer had to battle with seniority and precedent to make these staff changes, however the same way that he was appointed, the public service act stated “...special ability shall take precedence over seniority”. In addition, Farmer integrated the fragmented drawing offices to be under control of a design architect, which could oversee all the aspects of the project, and ensured oversight of the detailing and documentation alongside those working on the main documents. In addition, Parkes had not allowed the office to enter projects for architectural awards, however under Farmer’s leadership the branch began submitting projects for awards. To his immediate success, Ken Woolley’s design of the Fisher Library in the University of Sydney was the first project from the office to win an award, receiving the Sulman award in 1962 From the Royal Institute of Architects.

Undated photograph of a model of the doughnut schools designed by Michael Dysart, NSW Government Architect’s Branch. Photo: Max Dupain & Associates

Change came slow, however support for Farmer’s vision was endorsed by the ‘Design Room’ staff as well as Rembert. The success of the re-organisation of the office was seen by all over time as the overall quality of design and services provided by the branch was recognised. The realisation of a number of successful projects such as University of Sydney’s Chemistry school (1958) designed by Ken Wooley, and Goldstein Hall (1962) in the University of NSW, made the branch much more attractive to potential staff, and the drawing rooms were an overall happier and more efficient office under Farmer. Post war demand saw the need for a large number of new schools to be built, to accommodate for the rising population in both urban centres and regional towns. As the office received much of that work, Farmer formed ‘The School Section’ where a more organised approach to design and documentation of schools could take place, in order to raise the standard of the work. Previously the branch was not split into sections by programs, whereby the design of schools was fragmented across various drawing offices with no coordination or contact between the groups. The section was thus headed by R. Kirkwood, who had studied school design overseas with Clive Hadley, the secretary of the education department.

Specialisation such as this had only become possible after the re-organisation of the branch, but also as the total number of staff grew.

As time went on the size of the office and amount of work produced rapidly grew, whereby 1967 the branch grew to become the largest architectural firm in the country, and one of the largest in the world at the time. Handling hundreds of projects simultaneously, largely comprised of schools and public works, more buildings of recognised design merit were produced. Increased demand and growth of staff numbers, saw the formation of program specific research groups.

This thus allowed for the innovation of designs to excel and specialisation of architects to examine new principles and solutions for projects. One of the first noteworthy results of this research was Michael Dysart’s ‘Doughnut Design Solution’ for schools, allowing for good ventilation and double-sided natural lighting. This specialised research into innovative designs was only possible due to the large size of the overall office, which wouldn’t be possible in a small practice setting of many private firms. Farmer saw the importance for this continual education of staff through the sharing of skills, which would allow the branch to excel in the design of specific programs and increase the number of skilled architects. The high quality of the designs coming out of the branch was not only recognised nationally but reached international recognition at the height of their golden era. One of the leading British architectural journals ‘The Architectural Review’ published a four-page illustrated article on the works of the NSW Government Architects Office in 1967.

Tensions With The Private Profession

Although the profession recognised the high quality of work being produced by the NSW Government Architect’s office during Farmer’s leadership, the branch’s growth did not come without discontent. A growing number of practices from the private sector had begun voicing their concerns about the influence of the branch and its impact on the profession, where many believed there should be greater sharing of public works with the private sector. These growing concerns however were not an entirely new matter, the Government Architect’s Office throughout its history has always had a tense relationship with the private sector. During the 1860’s the Colonial Architect of the time ‘James Barnet’ was never admitted to become a member of the Institute of Architect’s NSW solely due to his position bureaucratic position. It was not until after his retirement from colonial architect that he was accepted as a honorary member10.

Other Government Architect’s such as Francis Greenway (1816-1822) and Mortimer Lewis (1835-1849) also faced criticism from the private sector.

Throughout the majority of Western countries, the design of government buildings and public works is generally undertaken by private architects through competitions, tendering, or patronage. The need for a bureaucratic colonial government architect had seen a downfall in popularity around the world as well as in most Australian states since the 1900’s, being surpassed by private practices. The deep rooted historical tensions and unconventional control over the design of the majority of government buildings, highlights the unorthodoxy of the authority the NSW branch had over public works. The prominence of the Government Architect’s office came about in early colonial NSW, where the lack of a mature design and building industry led to the appointment

of the first government architect in 1816 to fill the vacuum11. Since then, the branch’s profile saw varied success and falls through the years. The two decades between the World Wars saw them decrease in popularity until the rise in recognition during Ted Farmer’s lead. Over time, many architects from the profession believed the need for the branch’s focus to shift from design and construction, to becoming more of an authority which undertakes research and prepares briefs for consultants. There were multiple attempts over the years to reduce the high percentage of public buildings totally designed and documented by the Colonial Government Architects. To reduce tension a policy of sharing of works by allocation was instituted in 1905, to ensure a more even balance between the private and public sectors. After the second World War, Farmer’s former GA Cobden Parkes made genuine efforts to aid and support the private sector, maintaining close links and believing that the branch should work closely with the outside profession.

During Parkes’ time as Government architect, architectural consultants were often engaged to undertake drawing and specification of projects designed and superintended by the branch. He believed their collaboration was essential and avoided regarding them as merely draftsmen on the project, but architectural consultants. It was part of Parkes and Rembert’s vision for the branch to become an authority that focuses on preparing briefs, research and occasionally design projects

Government Architect Ted Farmer (Right) and Assistant GA Charles Weatherburn on the construction stite of the State Office Block Site, 1960s. Photographer Unknown. Courtesy of the Government Architect’s Office

Government Architect Ted Farmer (Right) and Assistant GA Charles Weatherburn on the construction stite of the State Office Block Site, 1960s. Photographer Unknown. Courtesy of the Government Architect’s Office

University of New England, 1960-1964.

GAO (Michael Dysart).

Photo: Max Dupain & Associates

that were out of the ordinary, a position the private profession supported. Parkes had seen this system used by the British Ministry of works, making an impression on him. During his career however he was unable to make this complete transition but gradually increased the amount of work given to private practitioners to support young architects struggling after the war.

Along with Ted Farmer’s appointment as Government in 1958, he brought along a new vision regarding the operations of the branch. Not only did Farmer disagree with the bureaucratic hierarchy, and organisation of the drawing rooms, but he also had an opposing vision for the branch’s relationship to the sharing of work with the private industry. Farmer held firm beliefs that the branch should operate as a normal architectural office instead of a brief preparing authority, with the private profession rarely providing aid. And most significantly, to the dissatisfaction of profession, he saw that the most prestigious and experimental works should be handled inside the branch. Upon taking up the office, Farmer began by scrapping the existing ballot system for selecting architectural consultants, which allowed for all approved consultants equal chance to be selected out of a ballot. Quoted saying that it had become ridiculous, Farmer instead created a list of approved architects, which would be selected from based on the direct project; not only were the firms handpicked, but Farmer nominated a partner from the firm to be in charge of the project. These rapid changes resulted in the frustration of the private sector at the new attitudes of the branch, which they saw as unreasonable and over-reactive, resulting in a bitter start to Farmer’s role.

The winning of awards in the early 1960’s and the recognition the office had received only acted to support Farmer’s views on the sharing of work, considering the work of the branch as being above the standard of the overall profession. The office’s ability to provide efficient and economic projects with high speed of delivery whilst maintaining high quality, public infrastructure meant that the branch had an upper hand over private practices. The re-use of details, consistency in applications of materials throughout the state12, and overall extensive experience allowed for a speed of production on projects that could not be achieved elsewhere. The repetition of details sometimes led to almost identical designs being echoed hundreds of kilometres apart throughout NSW13. This was rare however and Farmer and his staff placed especially strong influence on creating designs that were place specific, and sympathetic to their local environment. With hundreds of projects being completed under Ted Farmer’s time as government architect, the office was shaping rural, suburban and urban cities across NSW. Whereby projects completed in rural New South Wales often set the example for the town to follow. The tension between the branch and the private profession was thus often overshadowed by the recognition of their high quality of work.

The 1960’s saw a turbulent time for the office as a number of changes took place in the branch. The mammoth growth of the office in both the number of staff and projects handled was not embraced by all, especially the team of architects from The ‘Design Room’. In 1963, Ken Woolley was the first of the ‘Young Turks’ to leave the branch to pursue a career in private practice, closely followed by Peter Hall in 1966. Farmer was disappointed by the lead designer’s departure but was however grateful that they had planted the seed in many great younger architects working at the office under their wing. Finally, after a long and influential career at the branch, Harry Rembert retired in 1964, whereby his position was taken over by G.P Webber, later to become government architect in 1973. The growth of the branch had led many to fear that it would become impersonal and that the work produced might suffer from the load, views that Farmer didn’t agree with. In 1965 Farmer was appointed as the RAIA representative on the National Trust Council due to his interest in heritage and conservation in architecture, a position he held until his retirement in 1972. A Heritage Section was introduced to the office led by Peter Bridges, thus allowing for the branch to become closely involved with heritage issues, as well as act as an advisor for the National Trust on its programme of restoration. Following Jørn Utzon’s resignation from the Sydney Opera House in 1966, Farmer was placed in the awkward position

on the panel to select the architect to complete stage two of the work, in which Farmer’s former colleague Peter Hall was appointed.

“It was a time of great strain for E H Farmer, the chief of the New South Wales Government Architect’s Branch. He was Naturally consulted closely by the Minister, as to who could take Utzon’s Place - and he also had to receive petition signed by seventy to eighty of his own staff saying They believed Utzon was the only architect able to complete the job”14

By the 1970’s towards the end of Ted Farmer’s career, the branch had grown to become the largest architectural office in the world at the time, and had accumulated more RAIA awards and Sulman medals than any other practice in NSW to date. Finally, after 19 years of working at the branch as an architect, and a further 15 years as the appointed Government Architect, Farmer retired on December 7th, 1973 at the age of 64.