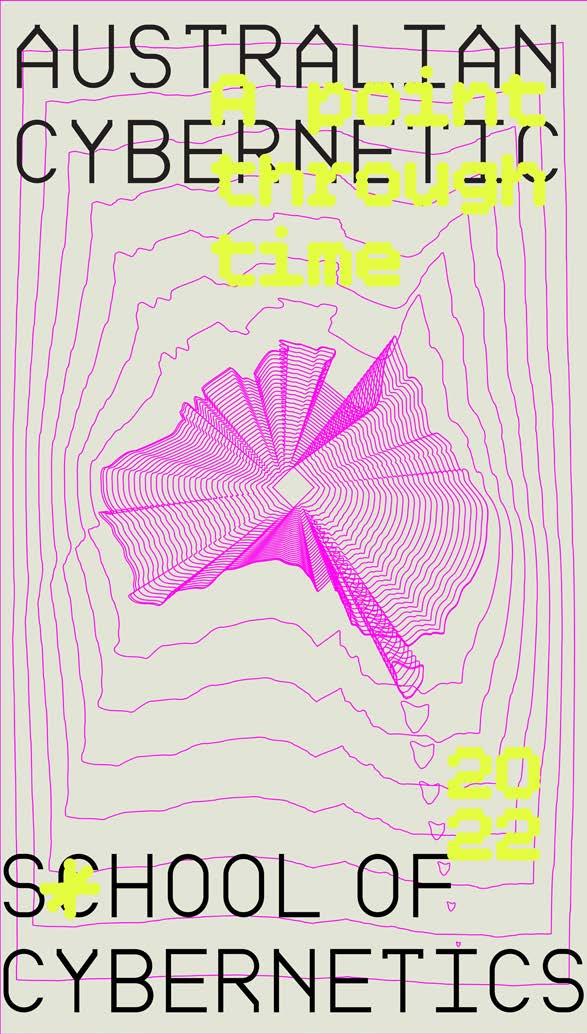

NOV 22 - DEC 02 2022

“The built in the and what today is by histories.”

NOV 22 - DEC 02 2022

“The built in the and what today is by histories.”

Genevieve Bell, 2022

ANU acknowledges the Ngunnawal and Ngambri people, who are the Traditional Owners of the land upon which the University’s Acton campus is located.

This Ngunnawal-Ngambri land supports students throughout their time at ANU. It will continue to hold a space for future generations to come together, and learn from Country and one another.

We also acknowledge and celebrate the traditional custodians of the many lands in which the works of this exhibition were created, resourced, traded, transported and shared.

We pay our respects to all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, Indigenous peoples, past, present and future, and acknowledge that this land from which we benefit has an ancient history that is both rich and sacred.

The ANU community makes a commitment to always respect the land upon which we stand and ensure that the voices of this land’s Indigenous peoples are both heard and listened to so that we may move towards a future marked by cooperation and mutual respect.

ANU acknowledges the Ngunnawal and Ngambri people, who are the Traditional Owners of the land upon which the University’s Acton campus is located.

This Ngunnawal-Ngambri land supports students throughout their time at ANU. It will continue to hold a space for future generations to come together, and learn from Country and one another.

We also acknowledge and celebrate the traditional custodians of the many lands in which the works of this exhibition were created, resourced, traded, transported and shared.

We pay our respects to all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, Indigenous peoples, past, present and future, and acknowledge that this land from which we benefit has an ancient history that is both rich and sacred.

The ANU community makes a commitment to always respect the land upon which we stand and ensure that the voices of this land’s Indigenous peoples are both heard and listened to so that we may move towards a future marked by cooperation and mutual respect.

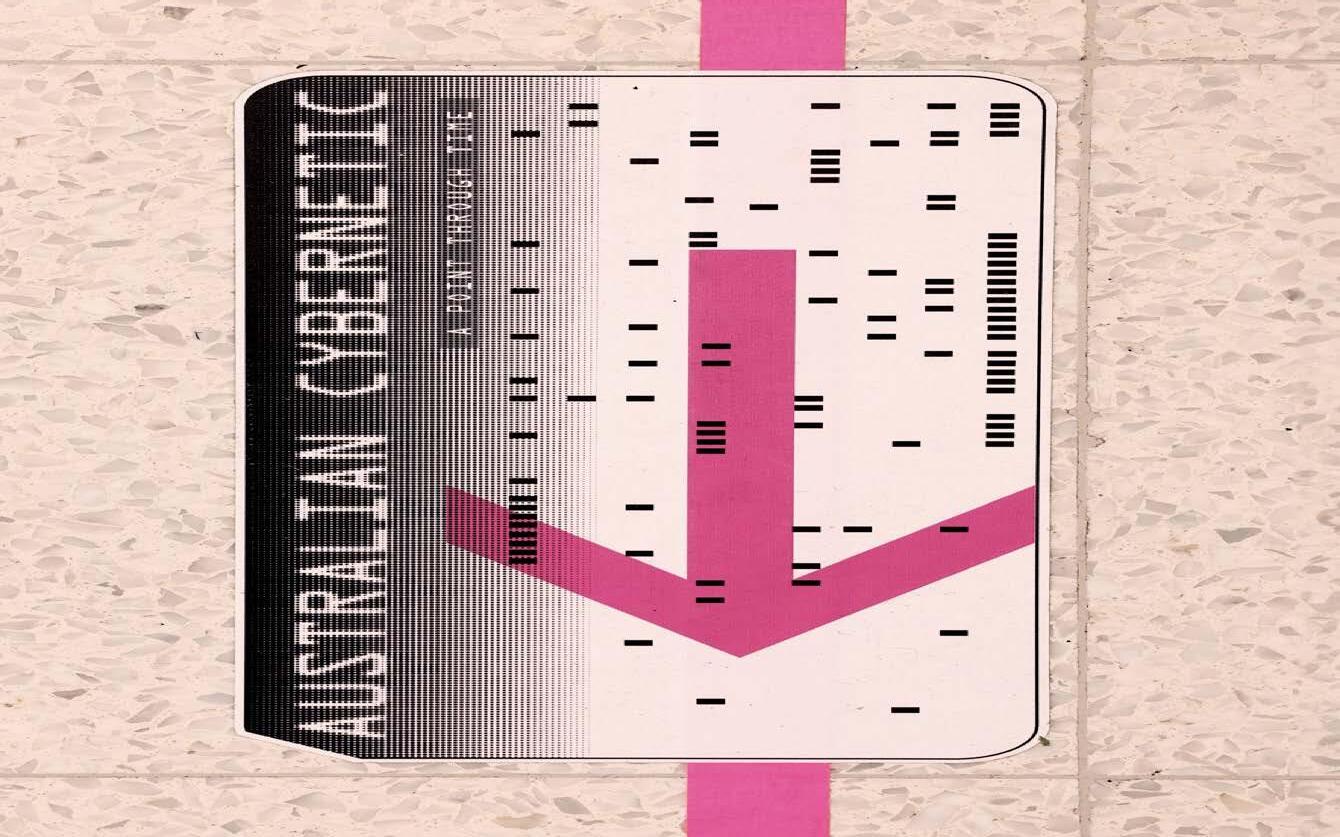

Australian Cybernetic: A point through time. Exhibition catalogue. / Andrew Meares, Amy K McLennan, Caroline Pegram.

First published in 2024 by the School of Cybernetics, Australian National University.

TEQSA Provider ID: PRV12002 (Australian University)

CRICOS Provider No. 00120C.

ISBN 978-0-6486337-1-6

Cover and book design by Eden Payne, Kopi Su Studio.

All exhibition photos by Andrew Meares, unless otherwise credited.

Every effort has been made to contact copyright holders; in the event of an error or omission, please notify the ANU School of Cybernetics.

This work is licenced under a Creative Commons Attribution Non CommercialShare Alike 4.0 International licence. This licence does not apply to content labelled as third party material.

creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/

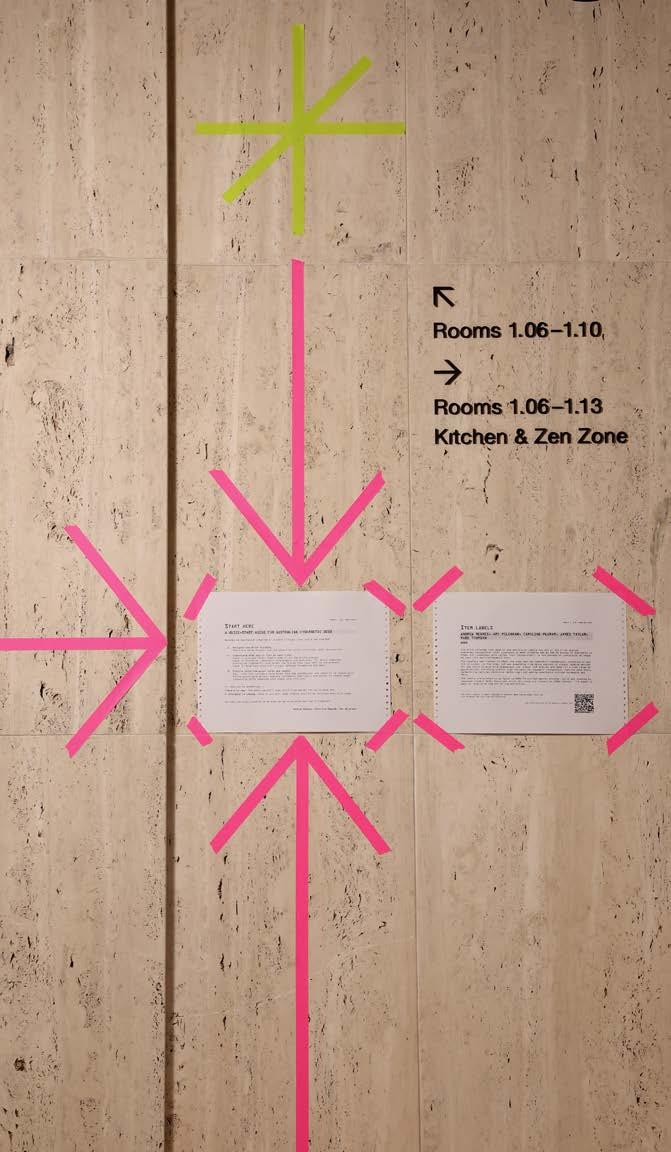

Curated by Andrew Meares, Amy McLennan and Caroline Pegram

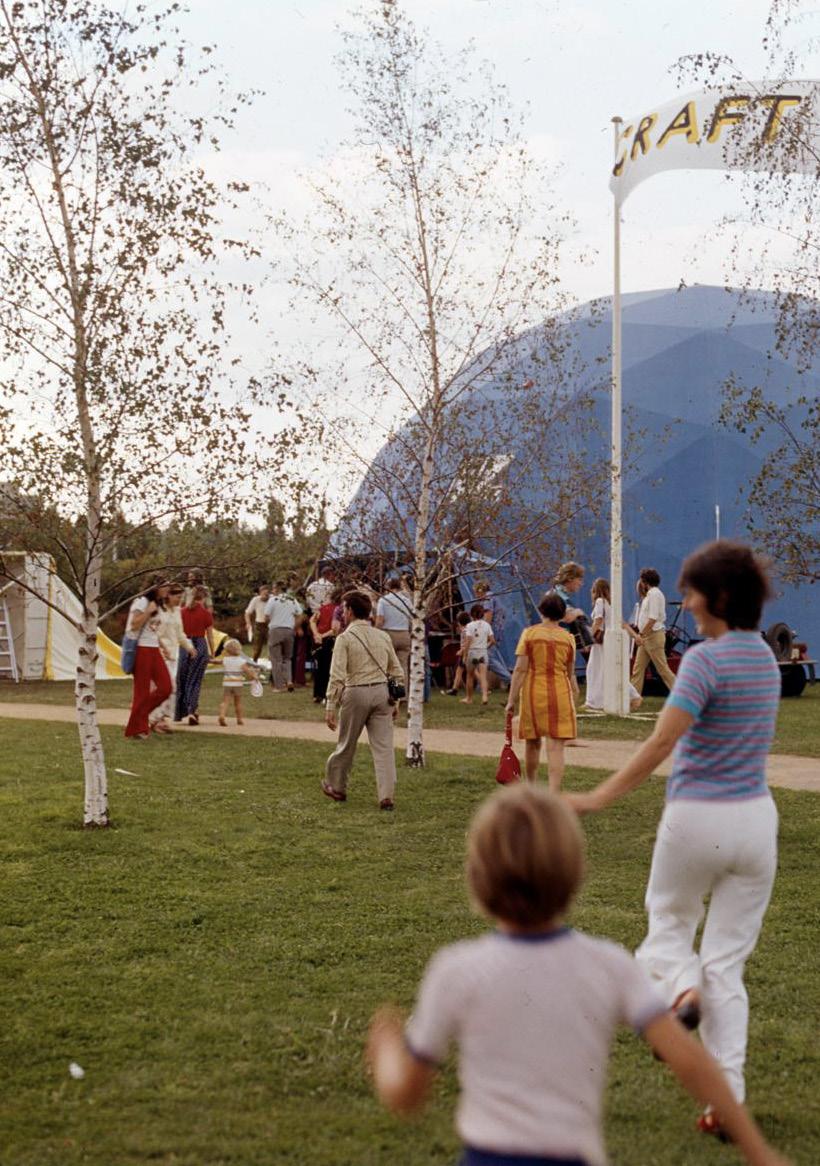

Welcome to Australian Cybernetic: A Point Through Time. This exhibition, like the Cybernetic Serendipity and Australia ‘75 exhibitions which inspired it, aims to imagine and enable new futures for complex systems comprising people, technology and the environment.

In this place, home to some of the oldest known human-built systems on the planet and shaped by intensifying human-caused climate change, in the wake of devastating bushfires and a global pandemic, Genevieve Bell founded the School of Cybernetics. Our mission is to revise and refit cybernetics for the twenty-first century and establish cybernetics as an important tool for navigating major societal transformations.

In early 2022, as a team of curators led by Andrew Meares, we began developing a small exhibition exploring cybernetics and futures in an Australian context. New possibilities and old stories criss-crossed our research. Past, present and future collided through works, stories, people and ideas. An emergent property of these interactions was a much larger exhibition, which we have documented in the following pages. We hope you enjoy exploring this point through time with us.

Andrew Meares, Amy McLennan, Caroline Pegram Curators of Australian Cybernetic

In the works exhibited at Australian Cybernetic: A Point Through Time, pasts, presents and futures of cybernetics and creativity collide in a uniquely Australian context. The exhibition is presented by a team at the ANU School of Cybernetics, at a moment where we are acquainting a whole new generation with the ideas and possibilities of cybernetics.

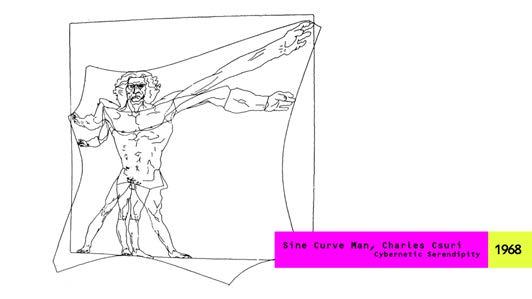

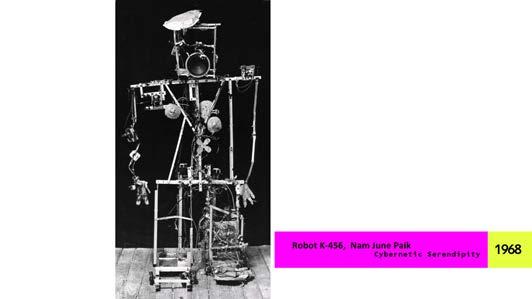

The sensing and acting computers that inspired fascination and curiosity among visitors to Cybernetic Serendipity in 1968 are familiar to us today. In the 1960s, though, the potential of the computer to catalyse societal transformations had been barely recognised. Instead of envisaging machines of cold efficiency or profound transformations and disastrous futures, Cybernetic Serendipity cultivated a sense of hope for the future and encouraged collaborations that brought vibrant futures into existence.

Today, we continue to imagine the possibility of interacting and interdependent complex systems and continue to search for ways to navigate new societal transformations sparked by new catalysts. At the same time, we are increasingly attuned to the effects systems enabled by computers have had on our world. How they enable great achievements as well as regrettable

ones. How they shape our societies and ecosystems, and how our societies and ecosystems shape them. We are starting to ask how *should* these systems be in the world? What would we create, how might we think differently, if we could hold a clear sense of the ways a new innovation creates, and is shaped by, ripples through time?

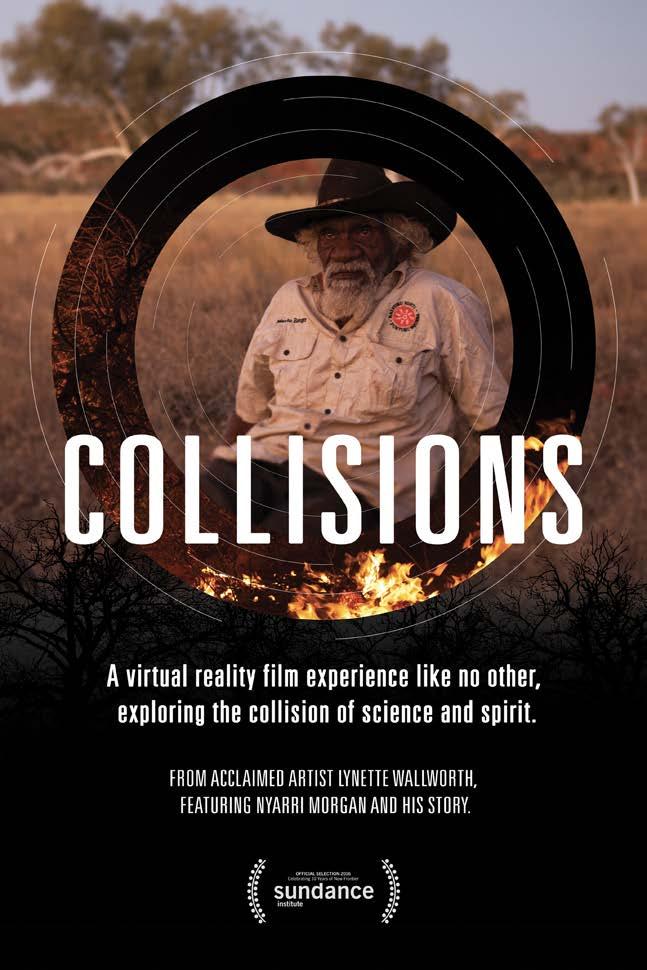

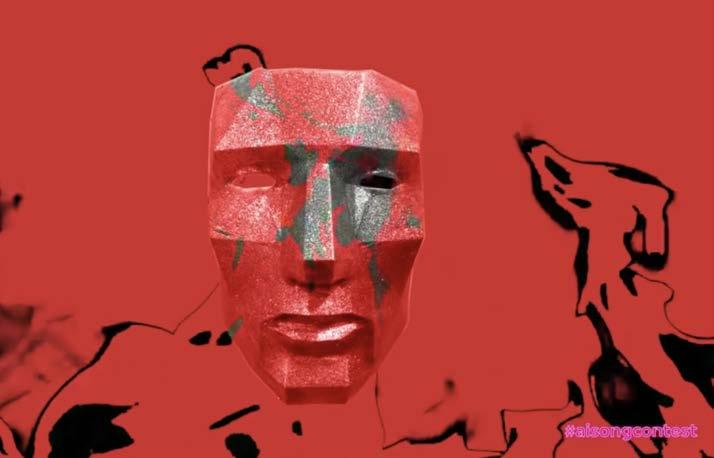

Works in Australian Cybernetic feature and respond to the echoes of historical technologies, artificial intelligence, virtual reality, and augmented reality, creating systems of music, image, machinery and storytelling that surface the often-hidden connections between increasingly complex systems and broader societies, cultures, communities, places, people and ecologies.

We began our research with the contributions to Cybernetic Serendipity in 1968. From here, we followed traces of that exhibition to Australia, revealing a direct link through to the people who curated a vibrant collection of works at the Computers and Electronics in the Arts exhibition that formed a part of the Australia ’75 Festival of the Creative Arts and Sciences. Traces from 1975 collide with the ANU School of Cybernetics today. Contemporary works in Australian Cybernetic include contributions from our Cybernetic

Imagination Residents for 2022-23: Kate Crawford, Lynette Wallworth and Mark Thomson.

Among several works borrowed from Cybernetic Serendipity for this exhibition is the interactive sculpture Albert: a robotic head created by John Billingsley. At the time of Cybernetic Serendipity, Albert was a cutting-edge example of responsive technology. Light sensors and a motor meant that Albert’s gaze followed visitors at the exhibition. One version of Albert has been delighting audiences at the Exploratorium in San Francisco since 1969, which graciously loaned it to us for this exhibition. In addition, John Billingsley created an entirely new Albert for Australian Cybernetic that uses the same principles of his 1968 version but uses a webcam to respond to visitors.

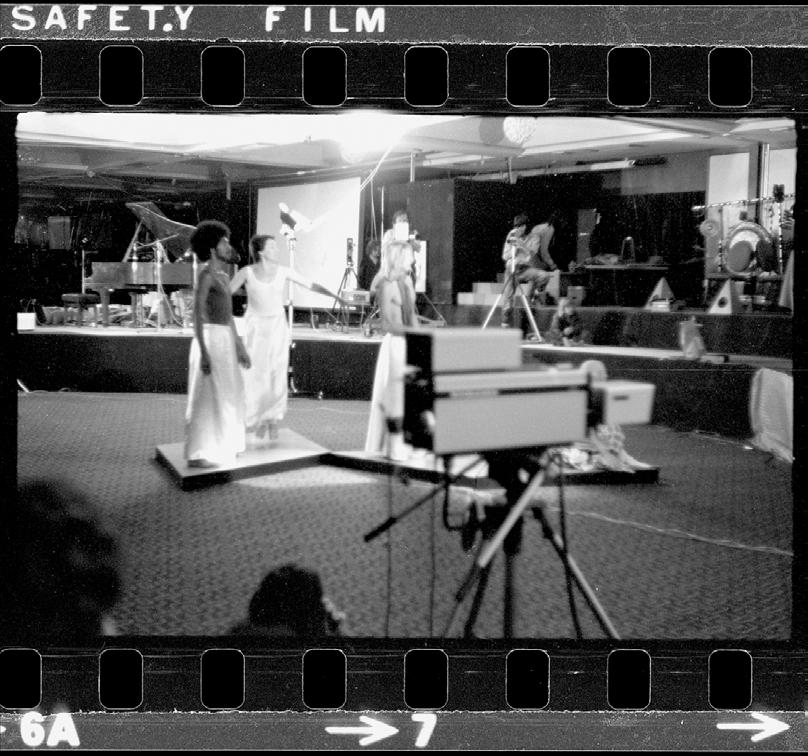

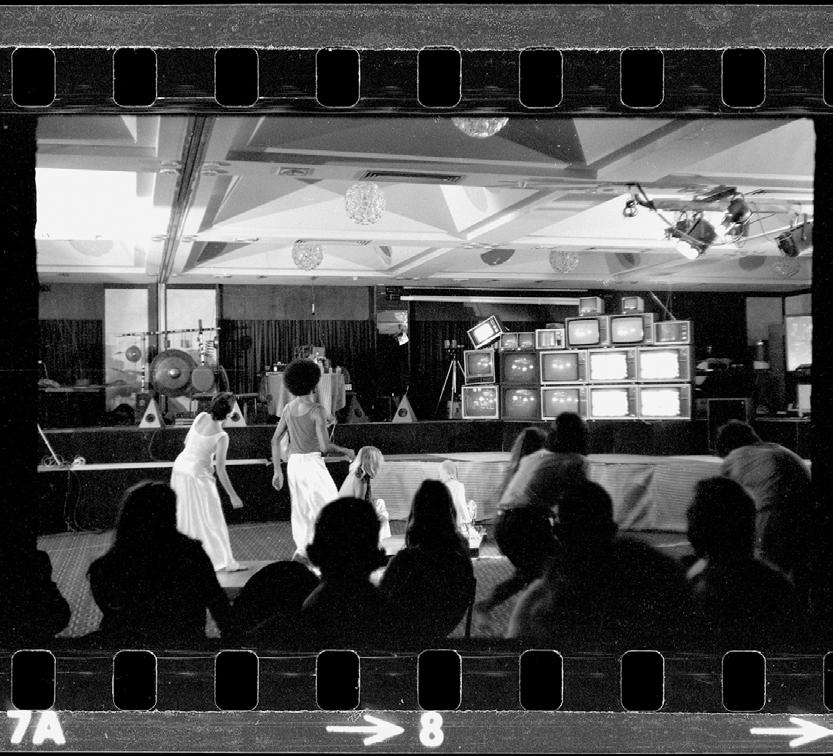

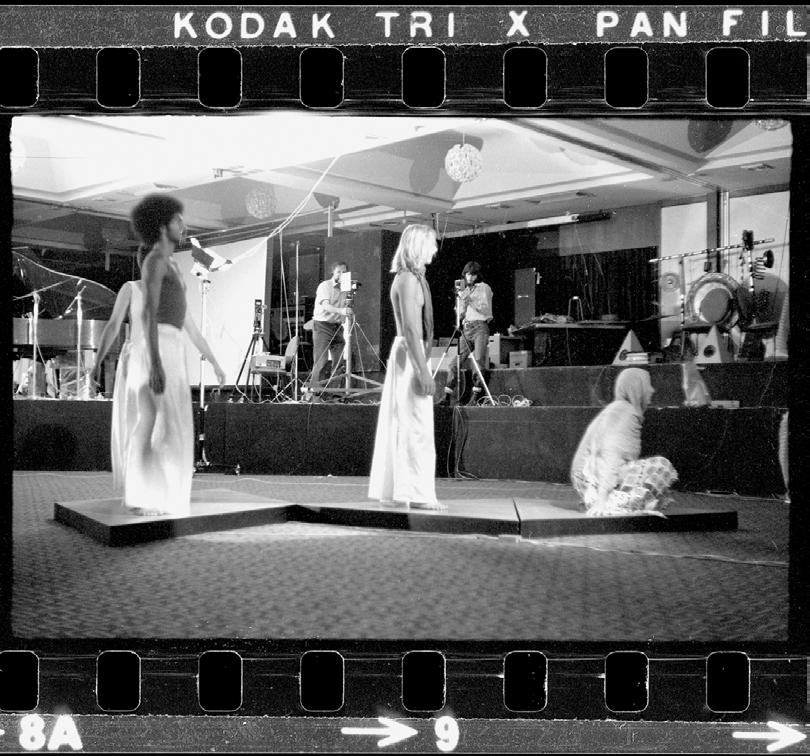

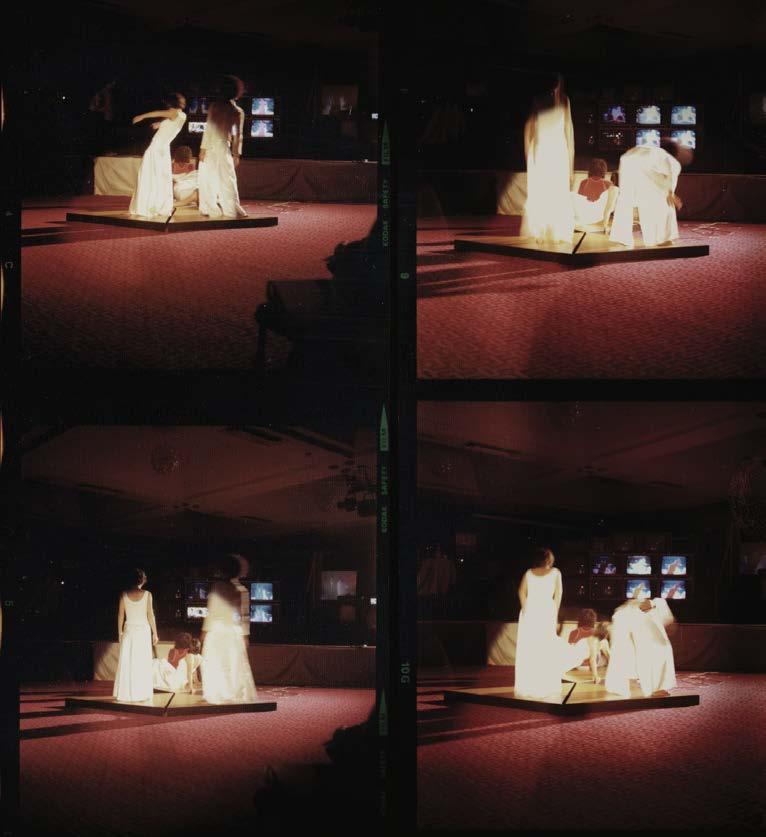

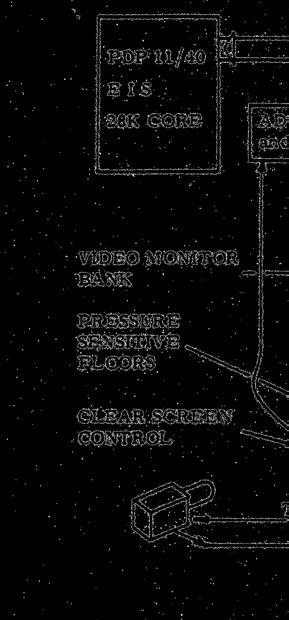

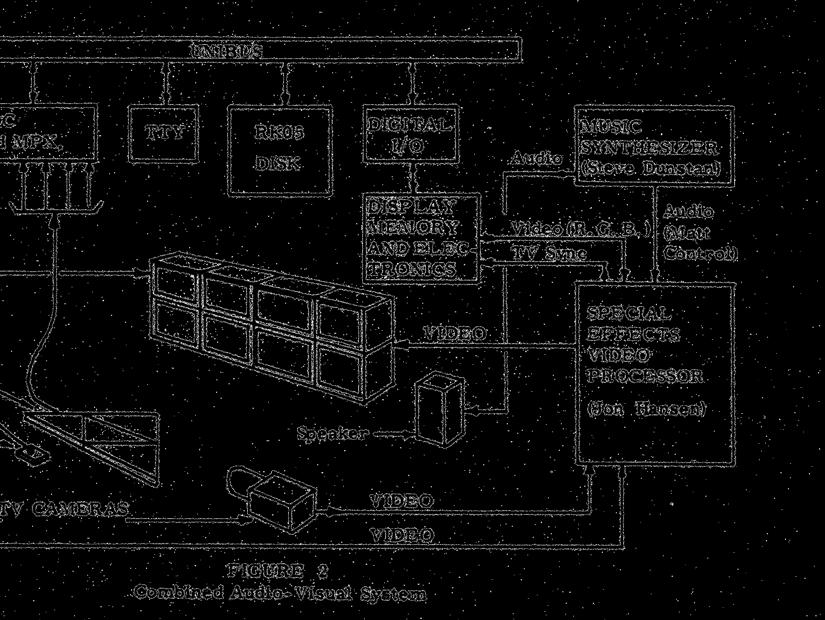

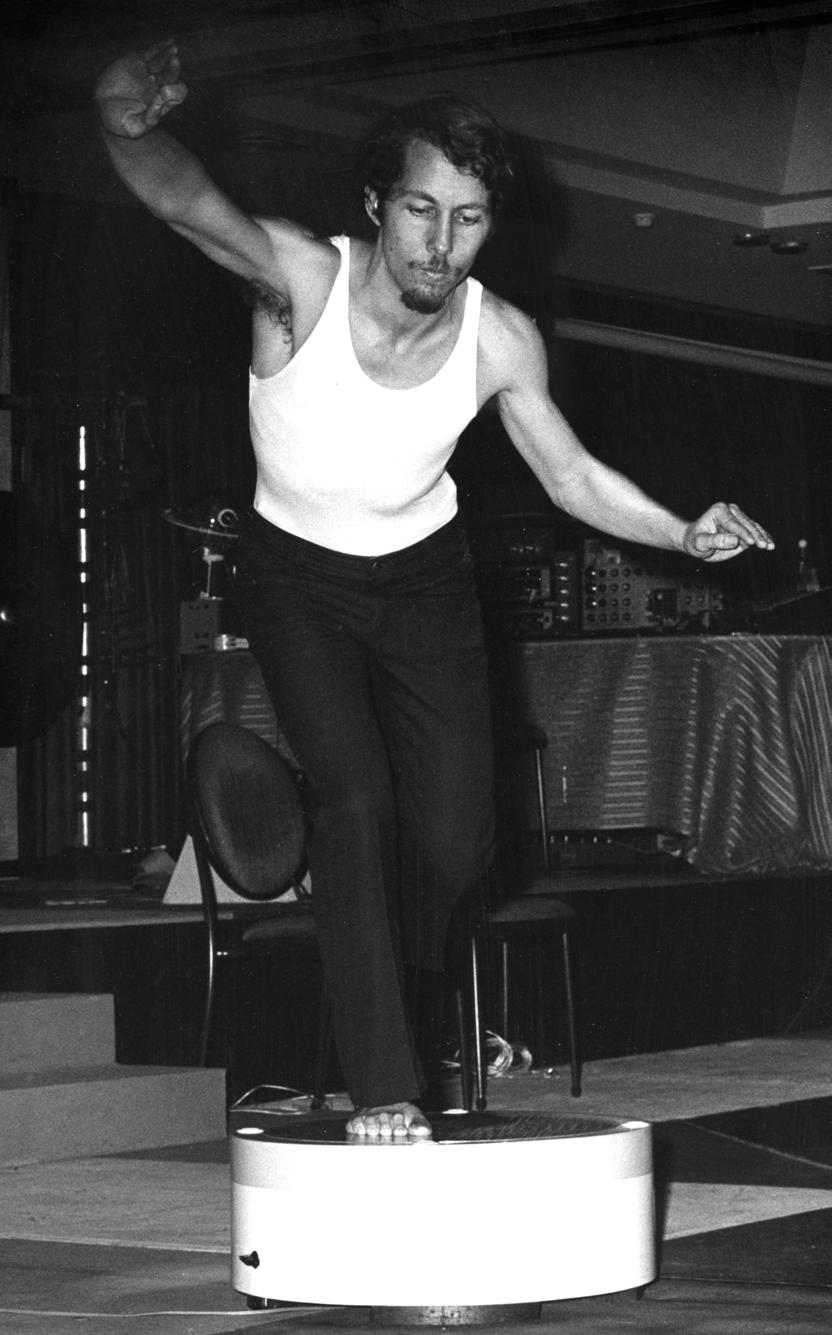

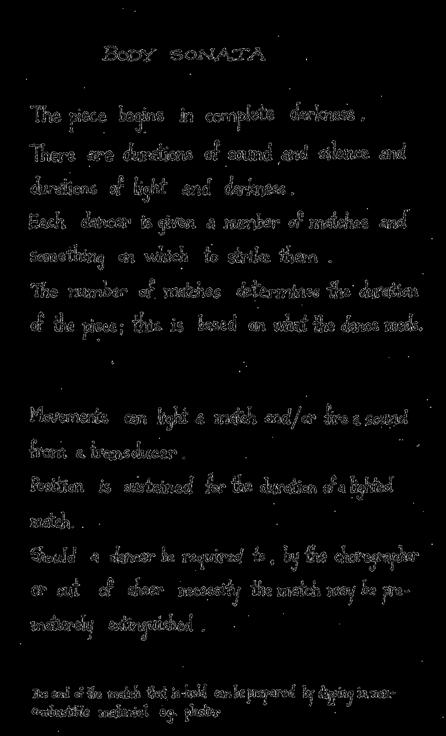

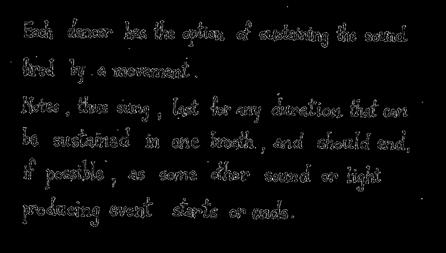

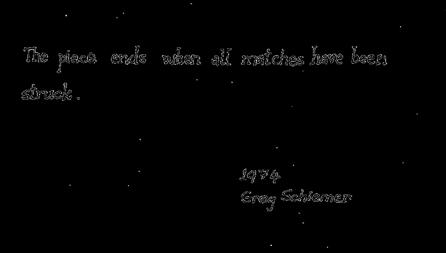

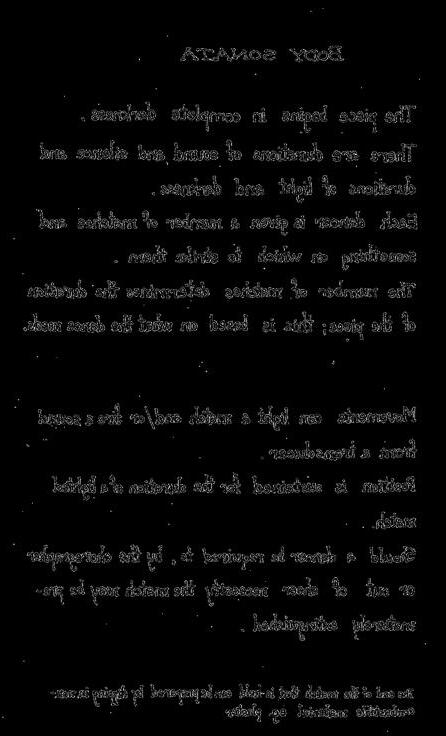

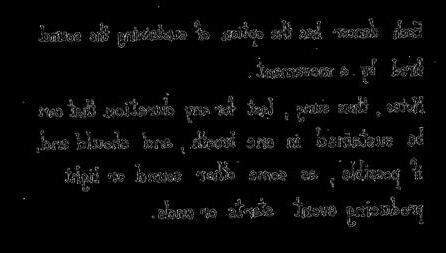

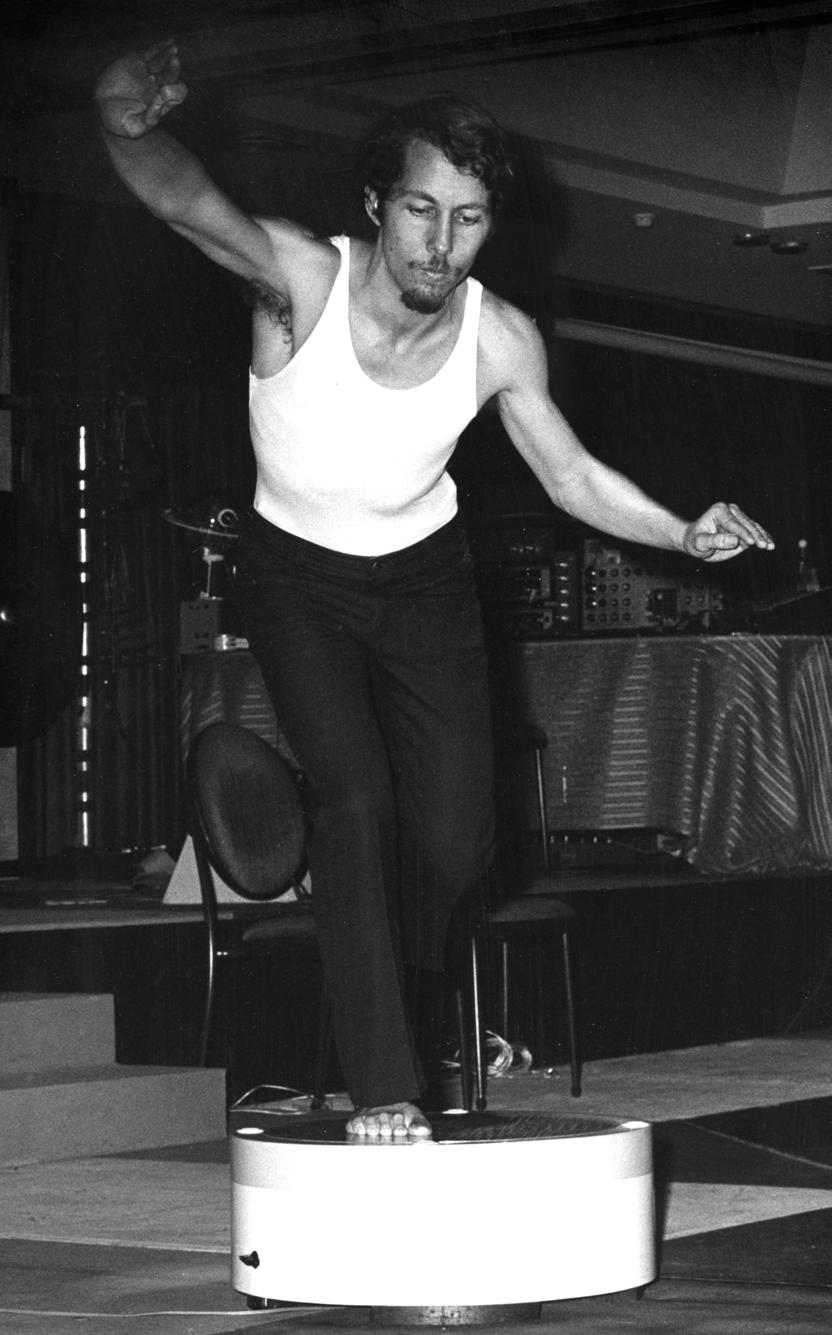

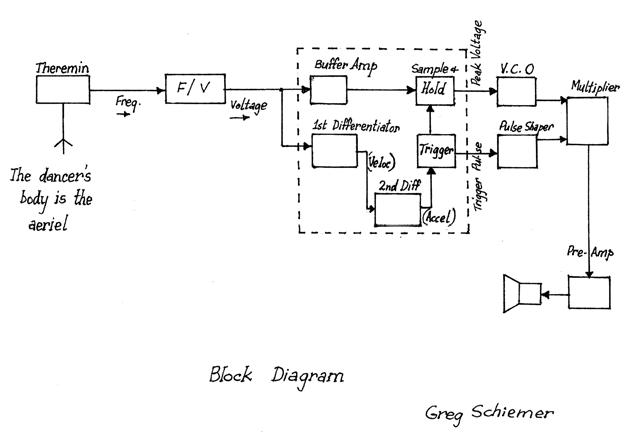

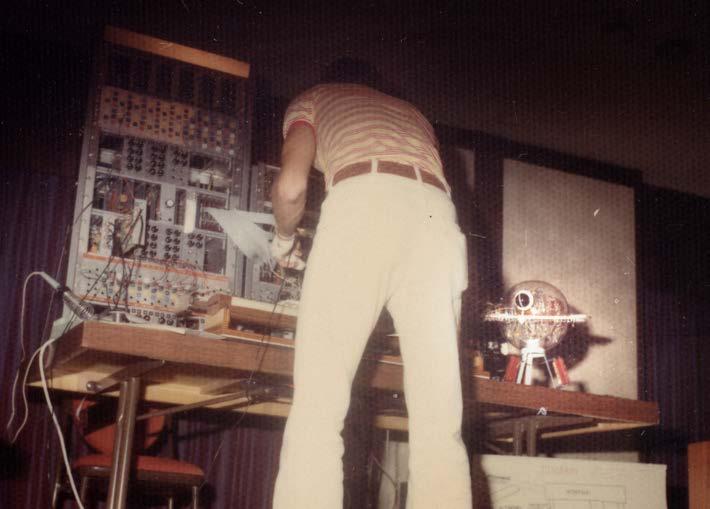

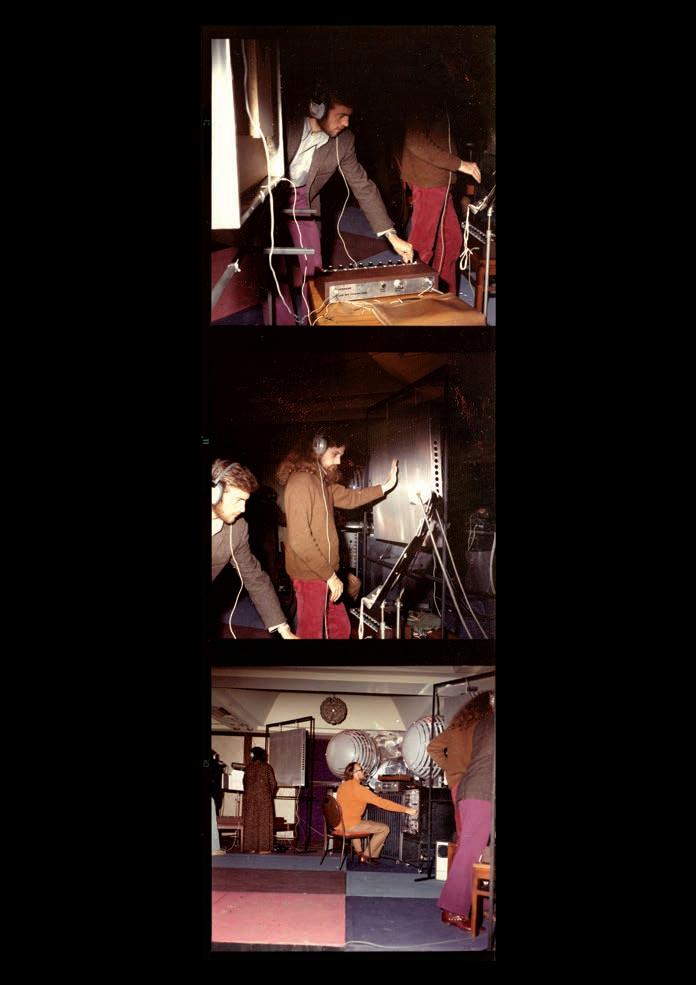

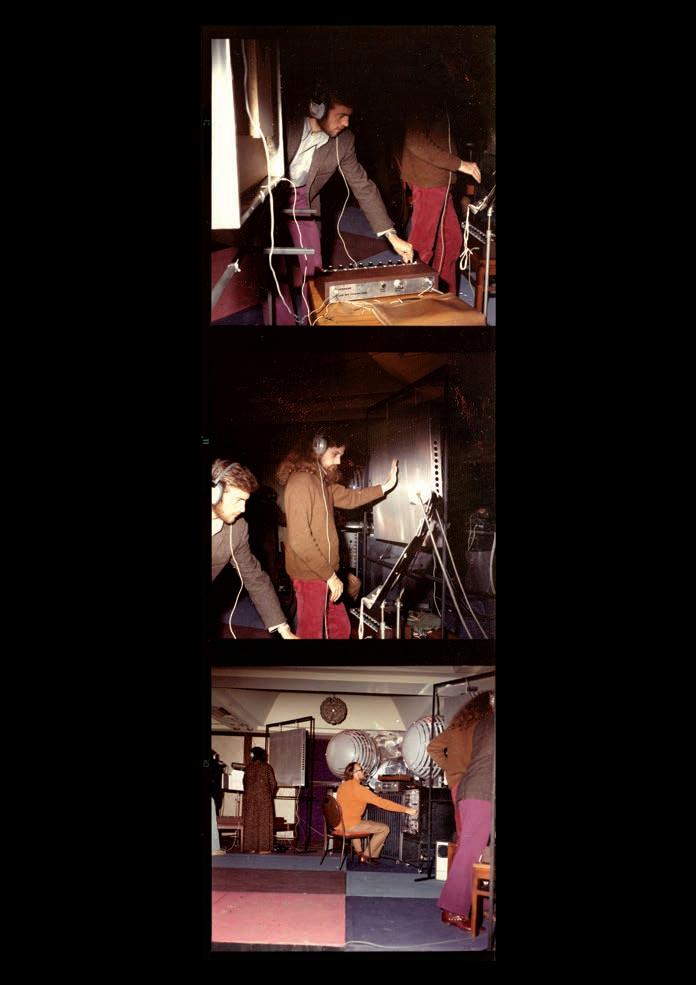

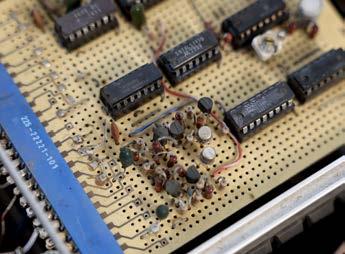

From Computers and Electronics in the Arts, we feature Philippa Cullen, an Australian dancer and choreographer. At the time, Cullen was investigating cybernetics, reading books such as Cybernetics: Or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine by Norbert Weiner (1948), Cybernetics Simplified by Arthur Porter (1969) and the Cybernetic Serendipity catalogue (1968). For the performance in 1975, Cullen – inspired by the cybernetic idea of feedback loops – built pressure-sensitive floors with collaborators Arthur Spring, Greg Schiemer and Phil Connor. The floors used embedded light sensors that would oscillate the pitch of the music in

response to the movements of a dancer. The dance, and pressure floors, had the addition of real-time video footage of the dancing. Cullen’s dance group, Steve Dunstan’s unique music, John Hansen’s video processing, and technology created by Chris Ellyard and Ian Mcleod from ANU Physics came together to create multiple interacting systems of movement shaped by feedback between humans and machines. At the time of Australia ‘75, works like Cullen’s spoke to Australian ingenuity, a rejection of rules that divided the arts and sciences, and a glimpse of an Australian future that was striving, raucous, and infused with creative energy.

The works in Australian Cybernetic also point to an important aspect of cybernetics: its role shaping emergent futures through facilitating relationships across a wide variety of people connected to a complex, goal-directed system. Alongside the works, we have started to unfold some of the many collaborations and relationships that sit behind a single technological advance or creative work.

In establishing the field of cybernetics, Norbert Wiener emphasised that futures arise from “yet unknown combinations of ideas from different fields of work,” requiring people with broad basic training and a capacity to cross traditional boundaries of specialisation. The works exhibited in Australian Cybernetic echo this, showing how futures are created by vibrant collaborations through time.

Australian Cybernetic has two intents: to trace back through points in time which have expanded the cybernetic imagination, and to ask how we may build upon these touchstones from our vantage, at the Australian National University, in 2022.

As we launch the School of Cybernetics and imagine what an Australian Cybernetic could be, we are aware that our futures are being created every day. By YOU, the group of people who today come together on the lands of the Ngunnuwal and Ngambri people to shape the tools, practices, communities and ideas that we hope will help us to navigate and steer complex systems of people, environments and technology with purpose and grace.

Cybernetics has been an intellectual wellspring for the twentieth century. Scratch the surface and somewhere there will be a link to cybernetics. It is more than just an approach to the future, it is also inspiration for a multiplicity of different futures, and a toolkit to get you there.

I hope when you walk into the Birch Building you will see a statement about what the future of universities could be like. Places that are dedicated to education and research. Places that celebrate our students. Places where you can feel learning happening and unfolding in front of you. You can also see the possibility of art, of design, of building and imagining a whole new world and a whole way of thinking.

You will find pieces all the way through this building. We’re making wonder and beauty and art and something genuinely splendid. So if there’s a story we want to tell about the future, it’s in this building right now.

Distinguished Professor Genevieve Bell Director, School of Cybernetics Australian National University

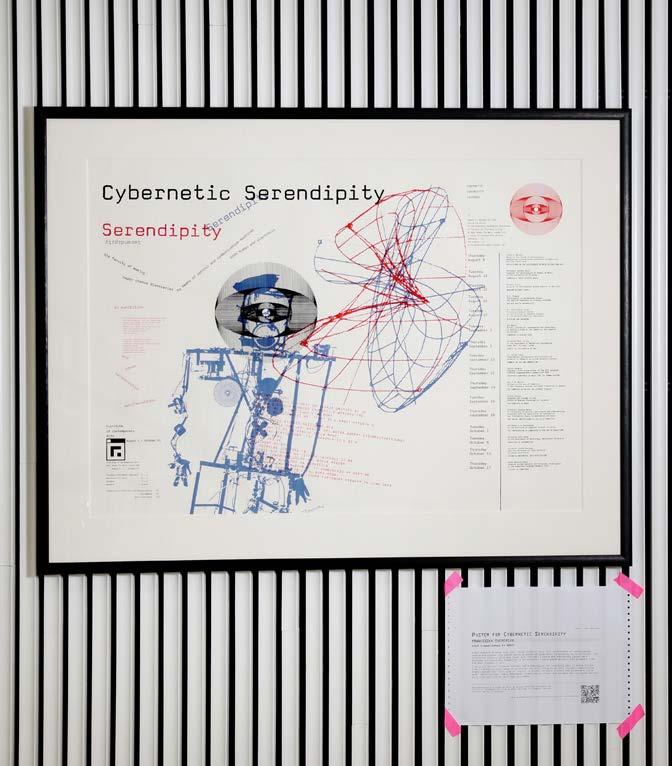

EDEN PAYNE, STELLA PALMER, ADRIAN SCHMIDT, KARTINI LUDWIG / KOPI SU STUDIO

2022

This interactive exhibition poster celebrates an embrace of technology’s influence on a creative output. It draws inspiration from the algorithmically morphing works exhibited at Cybernetic Serendipity and computer animations from Australia ‘75. Over fifty years later, those early technologies have become tried and tamed, embedded into design software. Yet there are still many moments of visual serendipity in this creative process.

Unlike its predecessor posters from 1968 and 1975, this poster steps beyond a static printed medium; it is displayed on a digital monitor and connected to a camera that detects the viewer’s proximity using computer vision. The poster shifts in colour as the viewer moves, creating a playful dance that embodies the creative human-computer relationship.

THE SCHOOL OF CYBERNETICS COMMISSIONED AUSTRALIAN CREATIVE AGENCY KOPI SU TO CREATE THIS EXHIBITION POSTER FOR AUSTRALIAN CYBERNETIC, INSPIRED AND INFORMED BY THE POSTERS OF THE EVENTS WHICH INSPIRED IT.

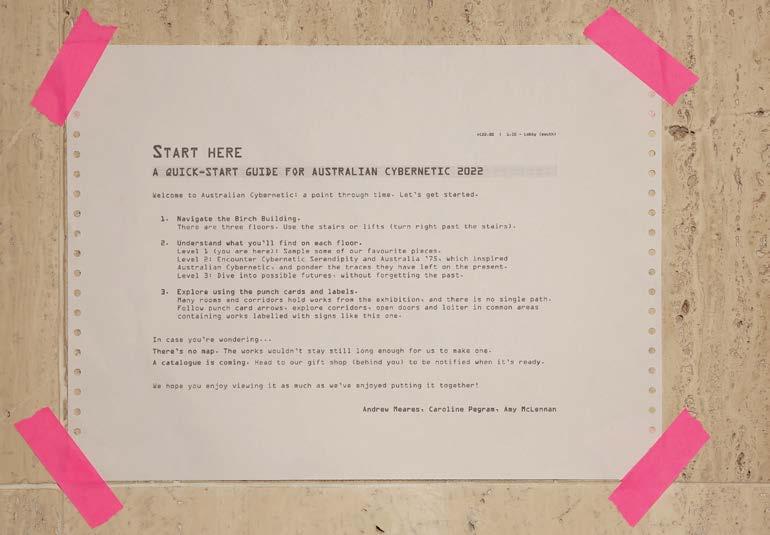

ANDREW MEARES, AMY MCLENNAN, CAROLINE PEGRAM, JAMES TAYLOR, MARK THOMSON

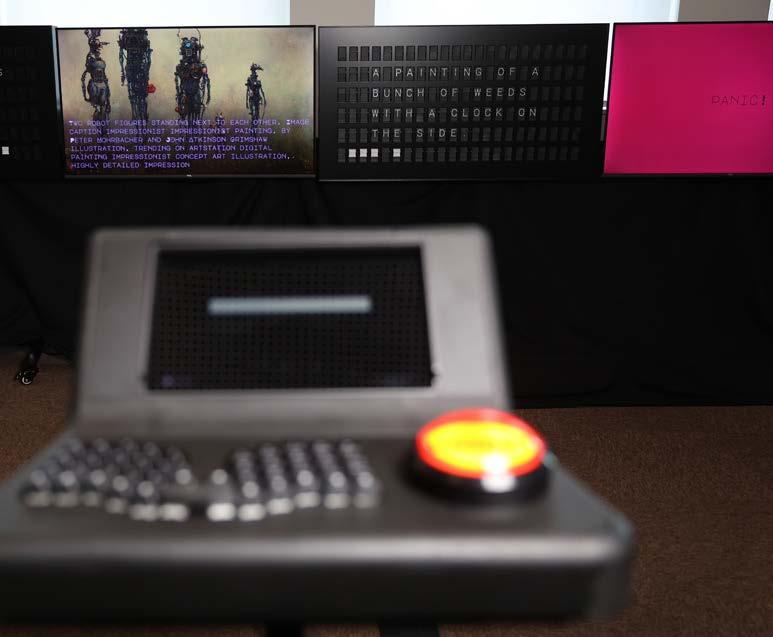

The OCR-A Extended font used in the exhibition labels was one of the first optical character recognition (OCR) typefaces to meet criteria set by the US Bureau of Standards in 1966; OCR (sometimes also called “text recognition”) is the process of converting an image of text into machine-readable text.

The typeface was created in 1968, the same year as Cybernetic Serendipity was exhibited at the ICA in London. At the time, OCR was expanding from being applied to create reading devices for the blind to much more widespread use. Today, OCR engines are used for a wide range of applications, including traffic sign recognition, passport recognition, banking data entry, handwriting capture, assistive technology, and making searchable printed documents and PDFs.

The labels are printed on an Epson LQ-2090 24-pin dot-matrix printer, which was created by Japanese company Seiko Epson and which can trace its history to 1920s Germany. The paper is easy to recycle at the end of the exhibition.

THE OCR-A TYPEFACE IS FREELY AVAILABLE ON MICROSOFT WORD VERSION 2210, WHICH WAS USED TO PRODUCE THE LABELS FOR THIS EXHIBITION.

SEE OCR-A EXHIBITED AT MOMA

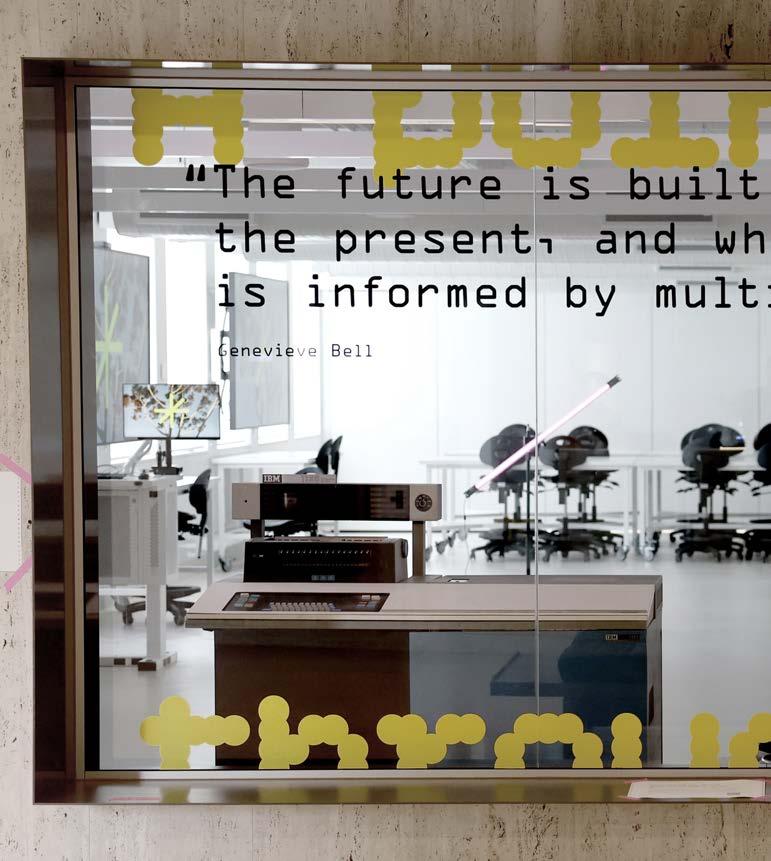

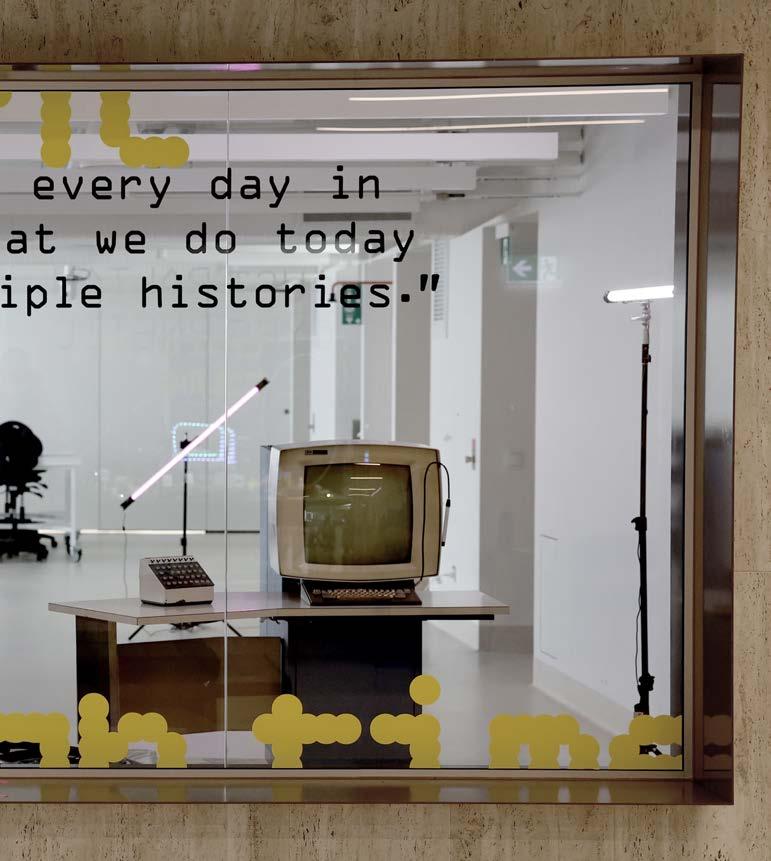

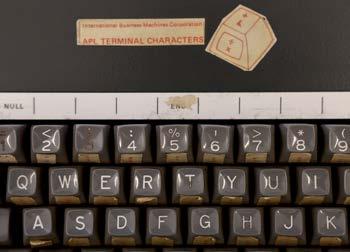

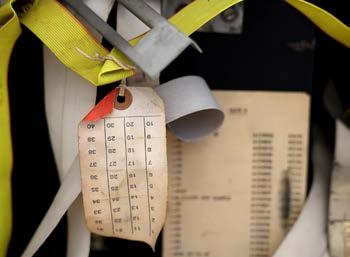

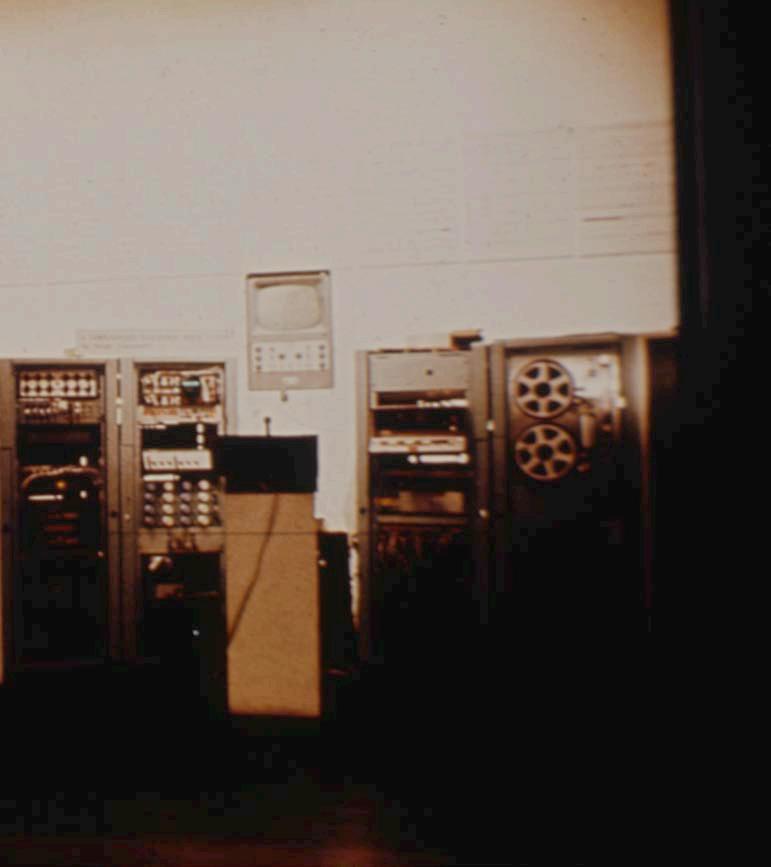

(BOTH PART OF COMPUTING SYSTEM IBM 1130 / IBM 2250)

1965

When released in 1965, the IBM 1130/2250 computer system and graphic display had an introductory price of around US$280,000 (roughly equivalent to US $2,638,000 in 2022). As it was IBM’s lowest-cost offering, it appealed to university research groups.

This is the sort of machine upon which many of the works in Australian Cybernetic were developed. It was not fast compared to today’s electronic computers: something that takes an average smartphone 1 second to process today would take 1130 seconds (or 83 minutes) on this computer. It is a reminder that the things exhibited here were not easy at the time. Yet, in experimenting with new ways of doing things, the people behind the exhibited works created a new space to imagine the future through and with technology; fifty years later, we can see that their work underlies many of the things we take for granted today.

This particular machine was based at the IBM Systems Development Institute (SDI) in Canberra, where it was used to develop research projects with university and industry groups. Projects prototyped on it range from simulating locks on the Murray River to sales support graphics for a construction firm.

WITH THANKS TO THE MUSEUM OF APPLIED ARTS AND SCIENCE (MAAS) FOR THE LOAN OF THIS OBJECT FROM ITS POWERHOUSE COLLECTION, 2008.

READ THE ITEM’S FULL DESCRIPTION FROM THE MAAS, WRITTEN BY STEPHEN JONES.

1965-1972

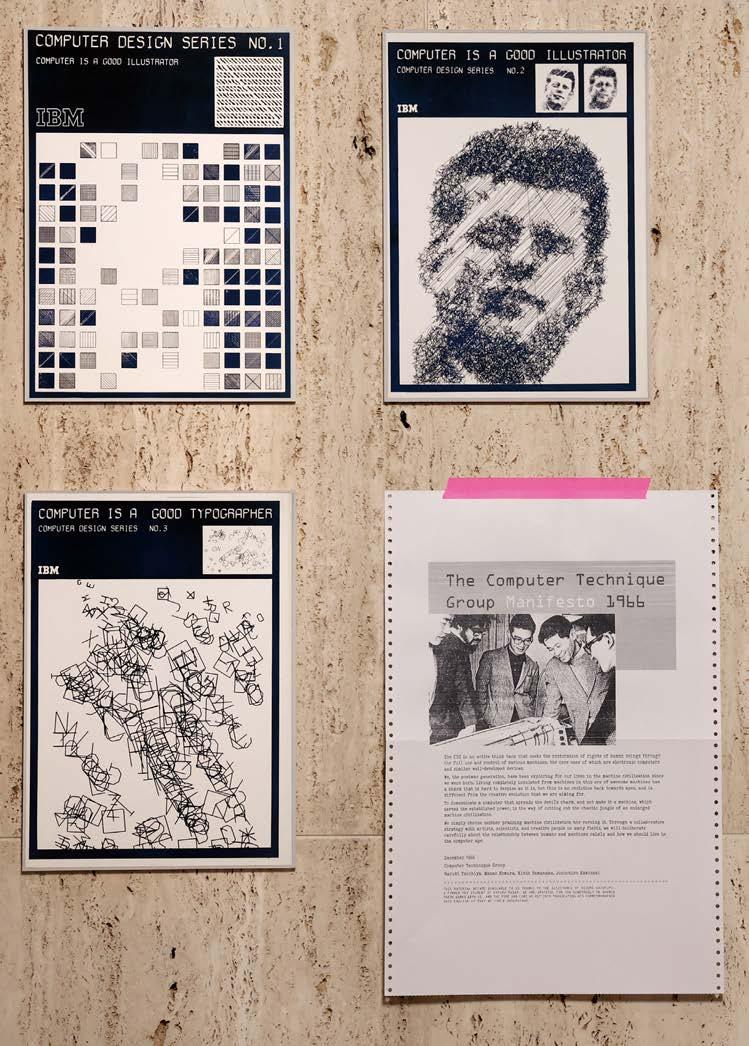

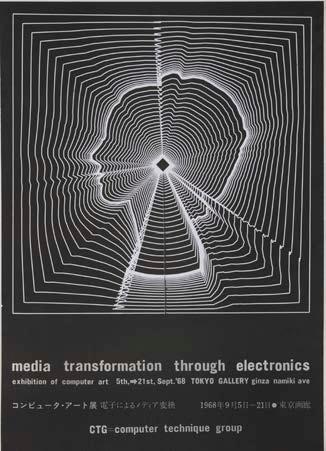

The Computer Technique Group’s (CTG) work is one example of what could be done using early electronic computing. The CTG was a collective of students in Japan who worked at the intersections of art and computing. Their manifesto (translated into English by them, and displayed here) sets their work in the historical context of the post-war period. They had over 20 pieces displayed at Cybernetic Serendipity; their work laid the foundations for presentday computer graphics and animation.

The CTG was founded in 1966 and disbanded in 1969; it initially included Masao Kohmura (a product designer) and Haruki Tsuchiya (a systems engineer), as well as Kunio Yamanaka (an aeronautical engineer) and Junichiro Kakizaki (an electronics engineer). Tsuchiya and Kohmura met at the sixth-term Fujita Gumi Student Executive Board, and from the moment Kohmura said “I want to draw pictures with computers” they started researching and exploring computer art production. At that time, the biggest barrier to their work was borrowing computers for free, but Tsuchiya was awarded an honourable mention in the IBM Student Essay Contest and the company agreed to support the CTG’s work. Subsequently, for each production project, the group submitted a proposal to Yoshinori Horiguchi, Director of Public Relations of IBM Japan, and obtained permission to use a company computer.

THIS MATERIAL BECAME AVAILABLE TO US THANKS TO THE ASSISTANCE OF KAZUFUMI OIZUMI, A FORMER PHD STUDENT OF MASAO KOHMURA. WE ARE GRATEFUL FOR HOW GENEROUSLY HE SHARED THESE WORKS WITH US, AND HOW MUCH TIME AND CARE HE PUT INTO TRANSLATING HIS CORRESPONDENCE INTO ENGLISH.

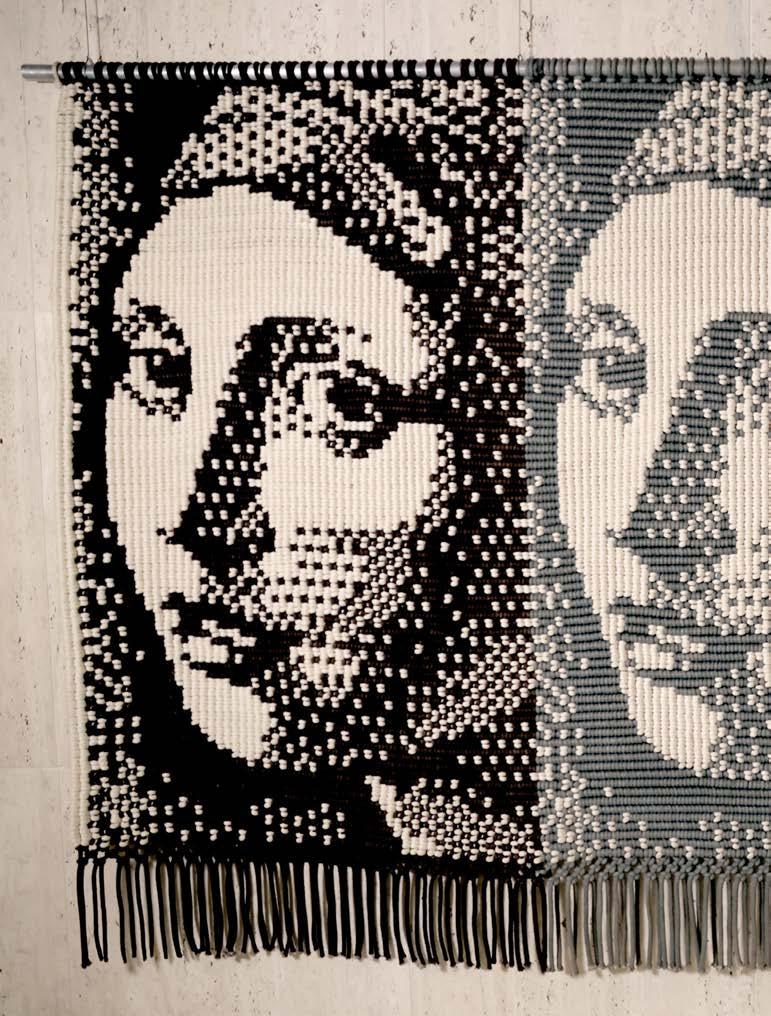

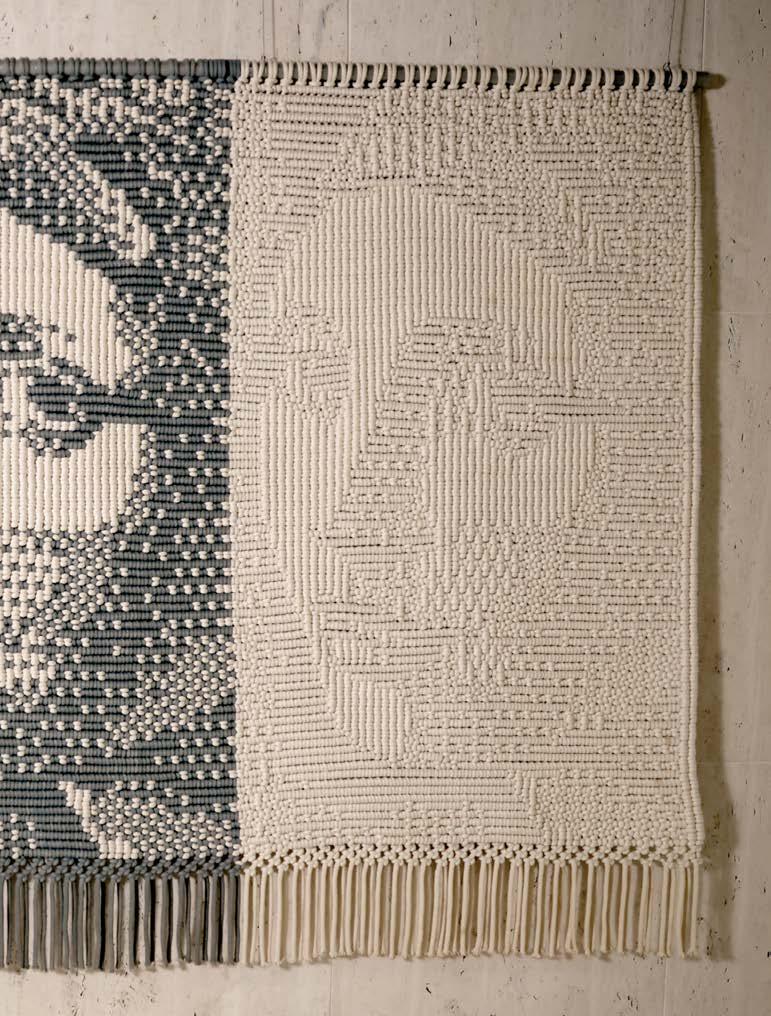

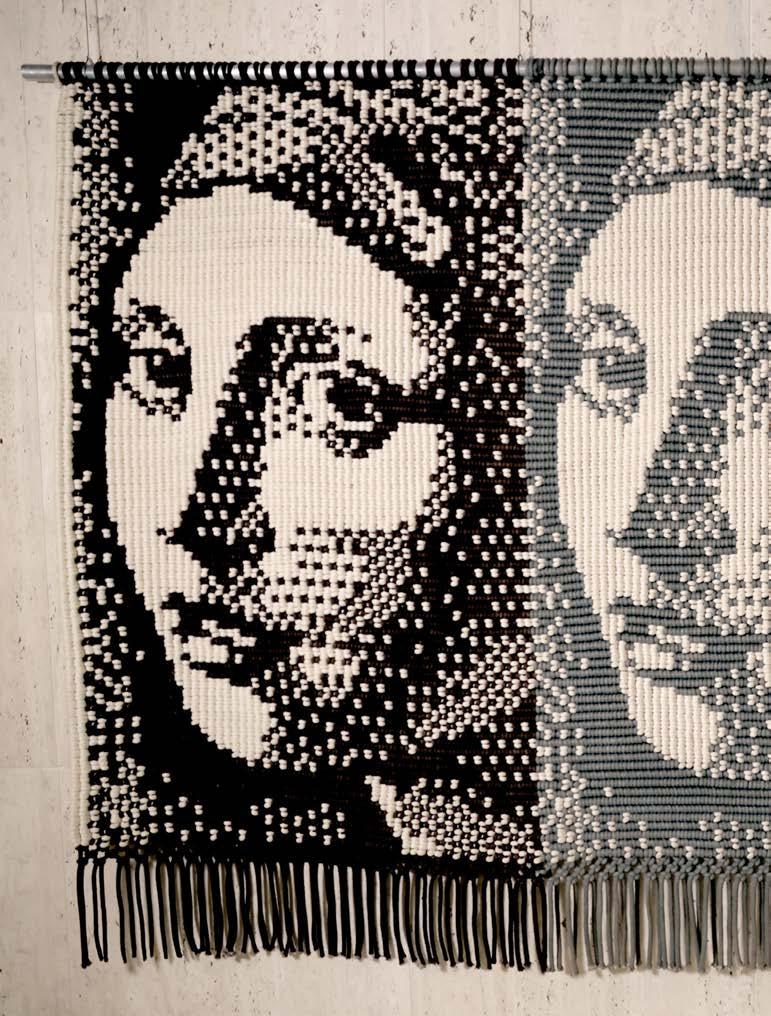

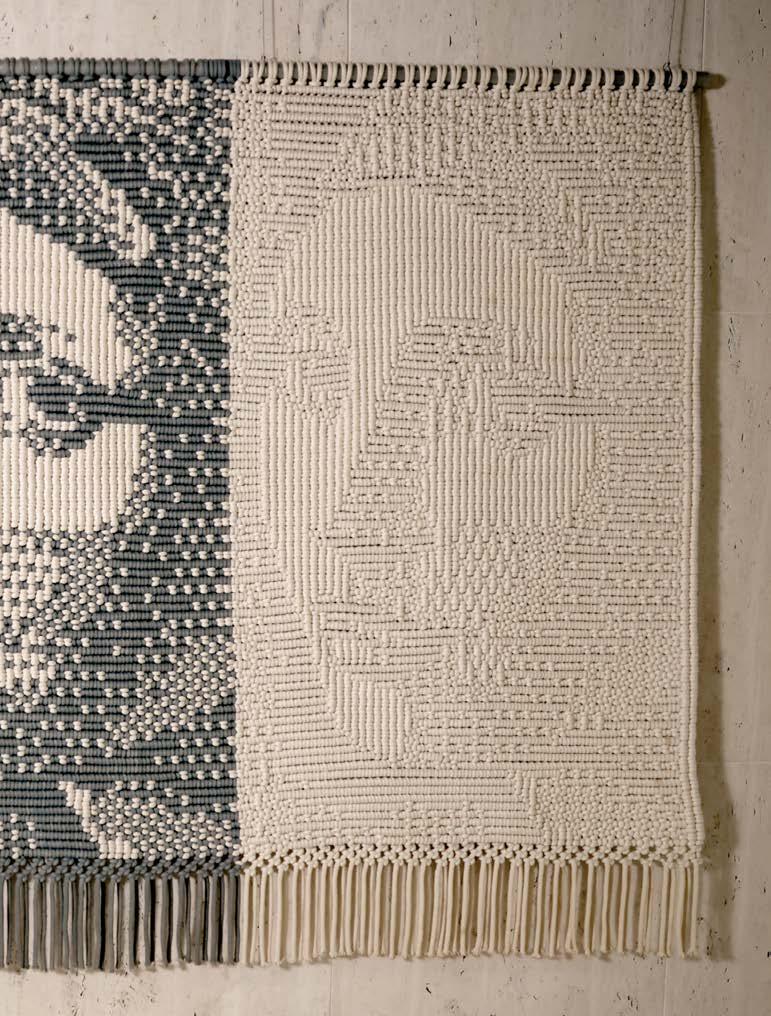

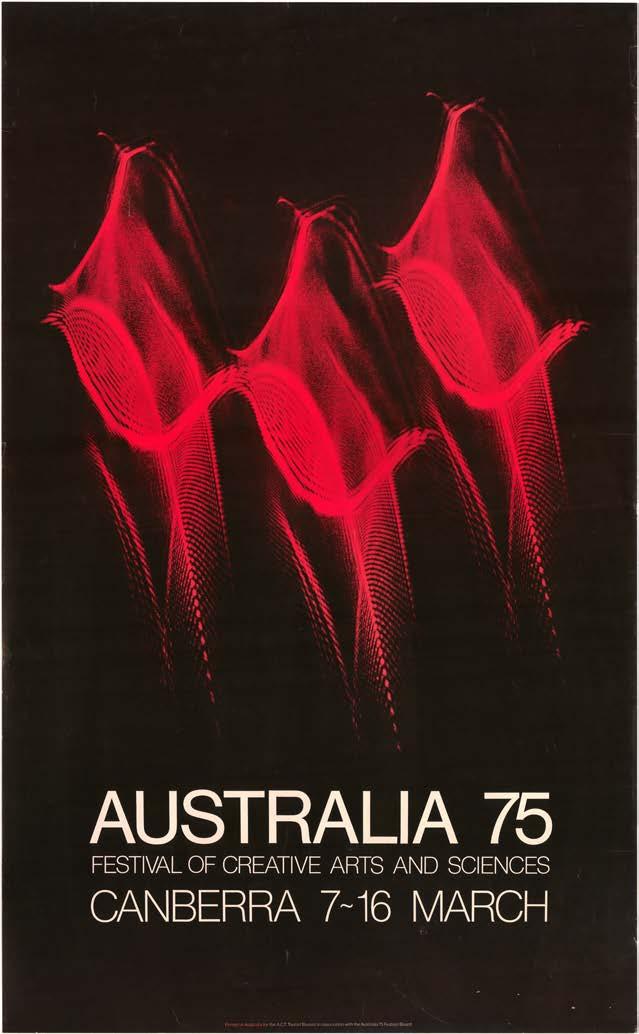

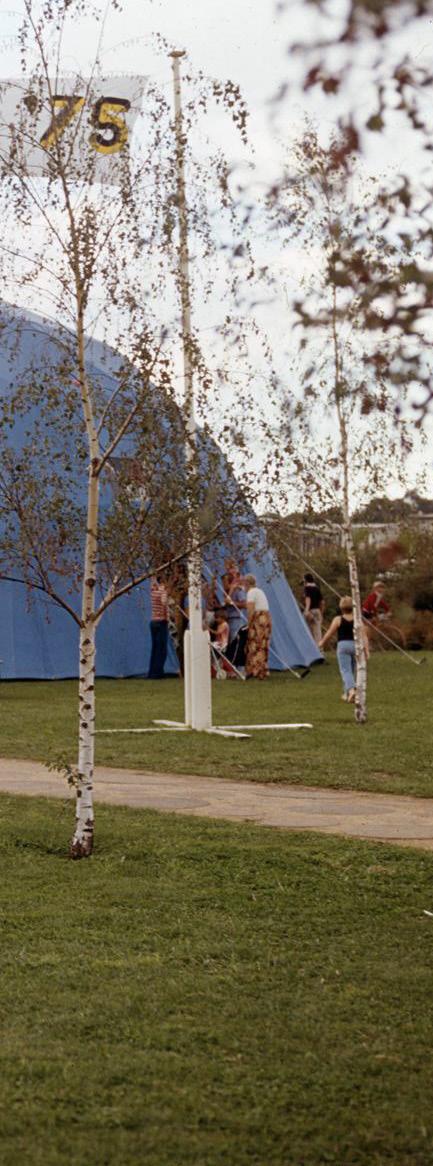

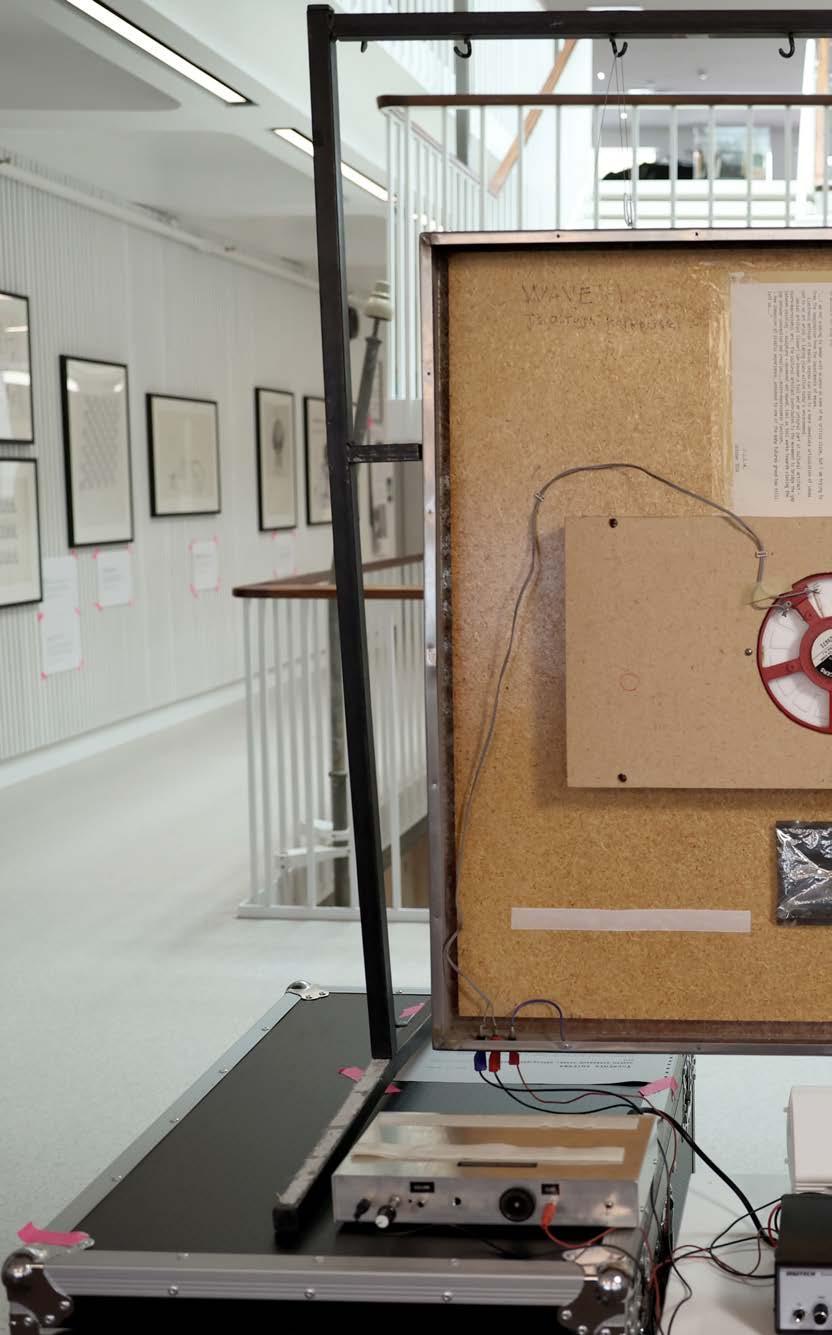

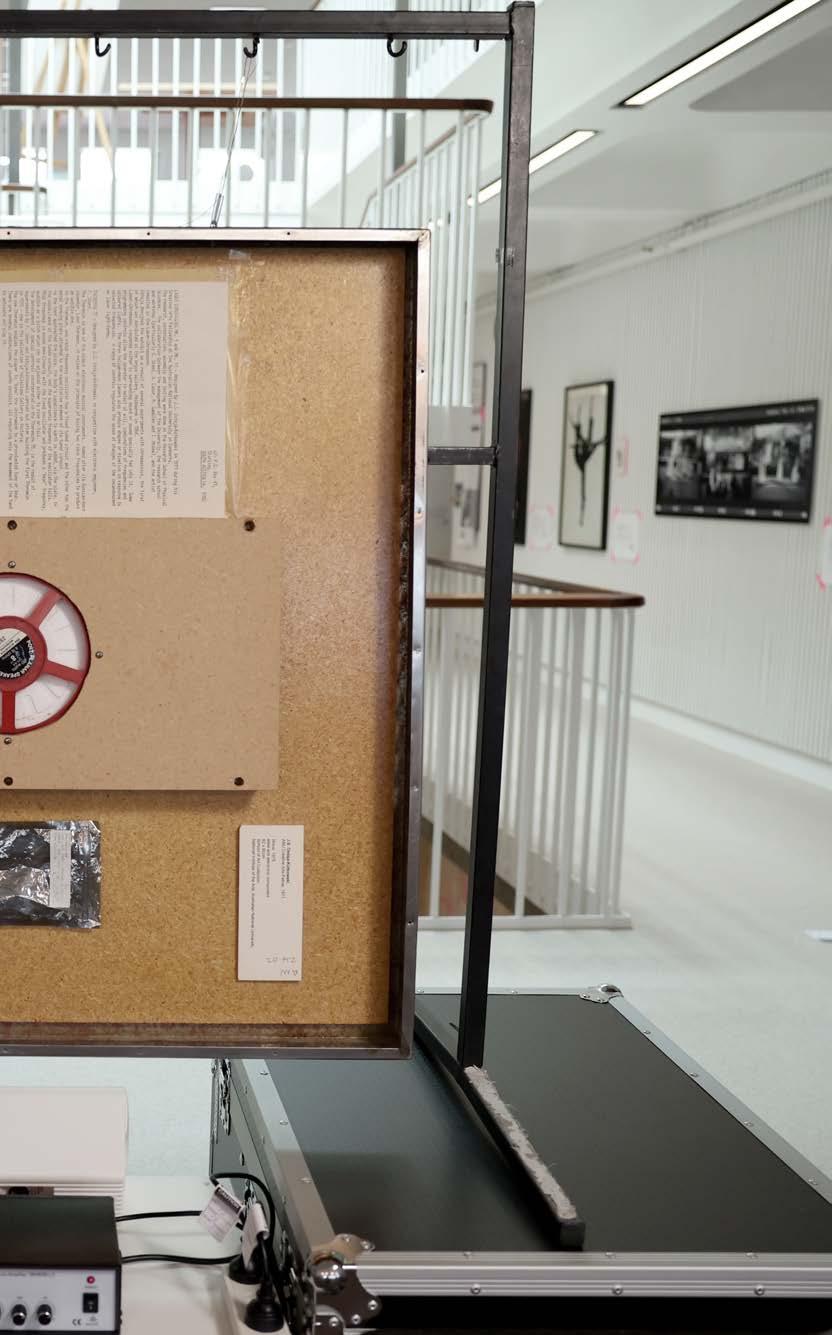

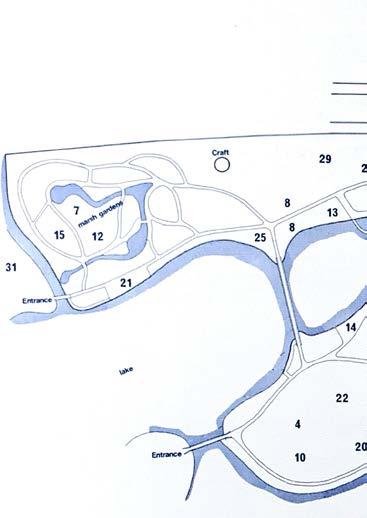

Craft ’75 was one of the numerous national exhibitions that formed a part of the Australia ‘75 festival, and Janet Brereton’s macrame tapestry won the major prize. The exhibition was hosted inside a blue geodesic dome tent in Commonwealth Park; the tent held works by 36 finalists for the National Craft Prize of Australia, which had been selected from over 400 entries via state panels.

As an early feminist artist, Brereton was concerned with the role of women within the new digital world. A number of her major works now in museum collections, such as Modern Woman held by the Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences, Sydney, engaged with mythologies of what it was to be a “new woman” at the time. Another significant work dealing with cybernetics was Tangerine Dream (1974) - inspired by the German electronic band which, incidentally, performed in the ballroom of the Lakeside International Hotel immediately after the Australia ‘75 exhibition there concluded. Brereton went on to be a major influence in bringing textiles into Australian art practice.

THIS TAPESTRY WAS ACQUIRED BY THE ANU FOLLOWING AUSTRALIA ‘75; IT HUNG IN THE FOYER OF THE BIRCH BUILDING UNTIL THE 1990S AND WAS RETURNED HERE BY THE SCHOOL OF CYBERNETICS IN 2022. THE TAPESTRY HAS SURVIVED TWO FIRES AT ANU, ONE OF WHICH WAS IN THE BIRCH BUILDING. WE ARE GRATEFUL TO DR KURT BRERETON, JANET’S SON, FOR PROVIDING ADDITIONAL INFORMATION AND CONTEXT ABOUT JANET’S WORK.

READ MORE ABOUT ‘CRAFT 75’ ON TROVE

“Craft ’75” was one of the numerous national exhibitions that formed a part of the Australia ‘75 festival, and Janet Brereton’s macrame tapestry won the major prize. The exhibition was hosted inside a blue geodesic dome tent in Commonwealth Park; the tent held works by 36 finalists for the National Craft Prize of Australia, which had been selected from over 400 entries via state panels.

As an early feminist artist, Brereton was concerned with the role of women within the new digital world. A number of her major works now in museum collections, such as Modern Woman held by the Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences, Sydney, engaged with mythologies of what it was to be a “new woman” at the time. Another significant work dealing with cybernetics was Tangerine Dream (1974) - inspired by the German electronic band which, incidentally, performed in the ballroom of the Lakeside International Hotel immediately after the Australia ‘75 exhibition there concluded. Brereton went on to be a major influence in bringing textiles into Australian art practice.

READ MORE ABOUT ‘CRAFT 75’ ON TROVE

THIS TAPESTRY WAS ACQUIRED BY THE ANU FOLLOWING AUSTRALIA ‘75; IT HUNG IN THE FOYER OF THE BIRCH BUILDING UNTIL THE 1990S AND WAS RETURNED HERE BY THE SCHOOL OF CYBERNETICS IN 2022. THE TAPESTRY HAS SURVIVED TWO FIRES AT ANU, ONE OF WHICH WAS IN THE BIRCH BUILDING. WE ARE GRATEFUL TO DR KURT BRERETON, JANET’S SON, FOR PROVIDING ADDITIONAL INFORMATION AND CONTEXT ABOUT JANET’S WORK.

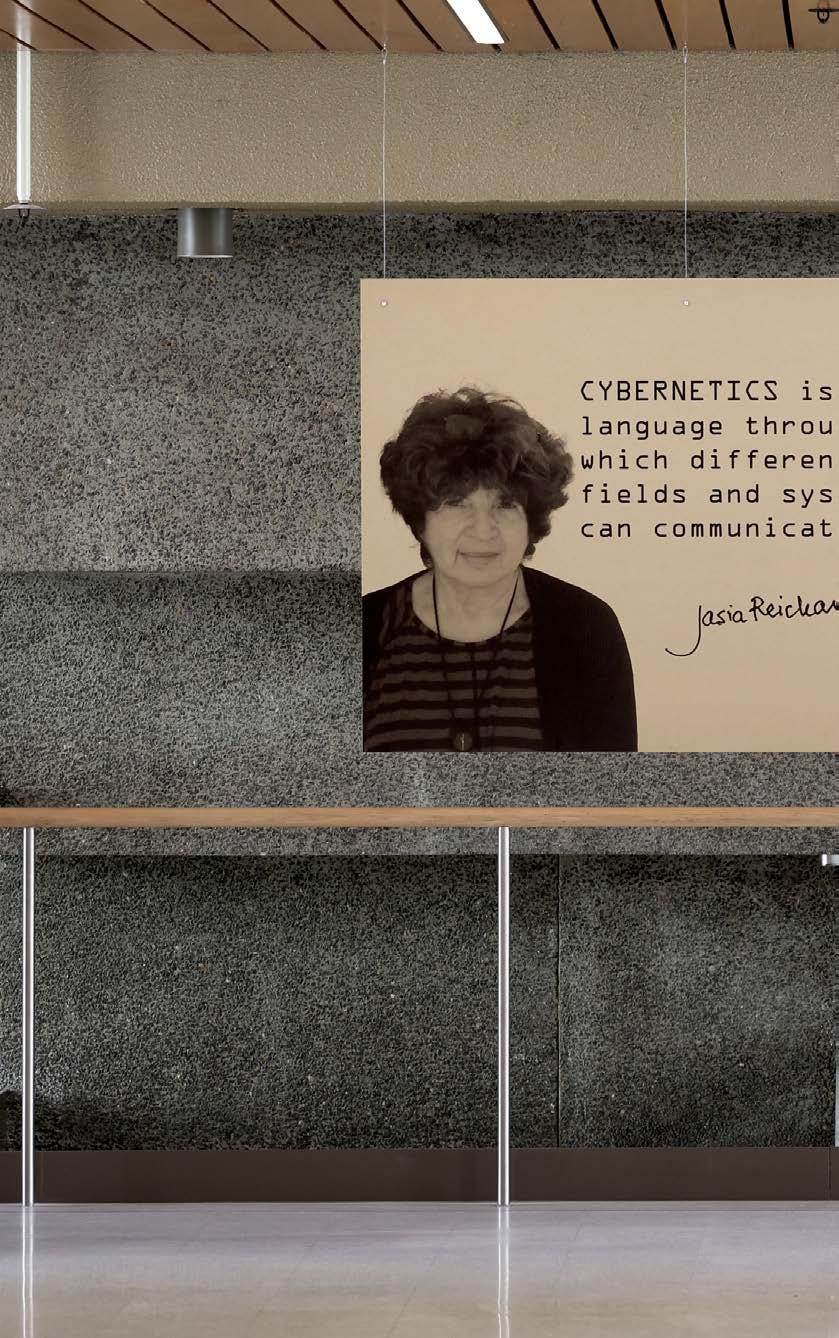

JASIA REICHARDT

2023

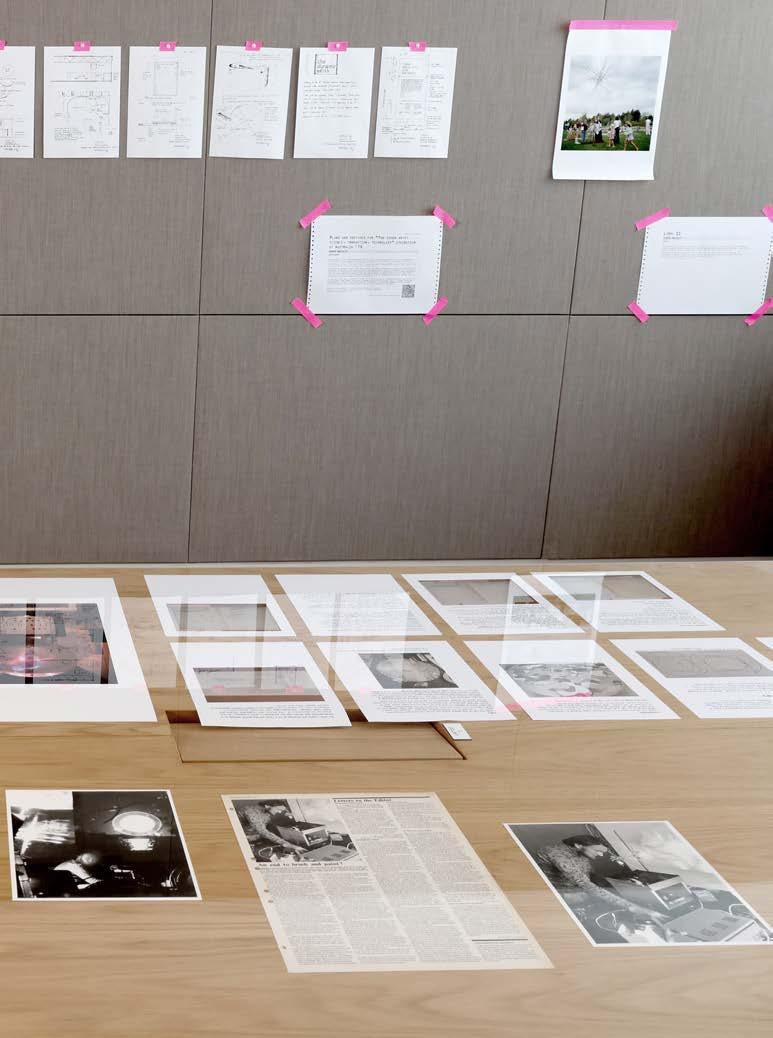

This publication is about how the 1968 exhibition Cybernetic Serendipity started and what it looked like. It offers glimpses into everything needed to make it happen, from press releases promoting the exhibition to installation views and a commentary on the exhibition layout.

Cybernetic Serendipity curator Jasia Reichardt, kindly offered this special edition to be published in Australia in 2022 to celebrate the opening of the ANU School of Cybernetics.

WE ARE GRATEFUL TO JASIA REICHARDT FOR GENEROUSLY OFFERING A SPECIAL EDITION OF THIS BOOK TO CELEBRATE THE OPENING OF THE ANU SCHOOL OF CYBERNETICS, AND TO PEDRO CID PROENÇA, ROGER ALLEN, GENEVIEVE BELL, MIGUEL BENAVIDES, ROBERT DEVCIC, STUART GEDDES, PASCALE DE GRAAF, MARTIN KENNEDY, AMY MCLENNAN, ANDREW MEARES, CAROLINE PEGRAM AND ZIGA TESTEN FOR MAKING IT HAPPEN IN TIME.

PURCHASE A COPY OF THE FINAL RELEASE

1963-1972

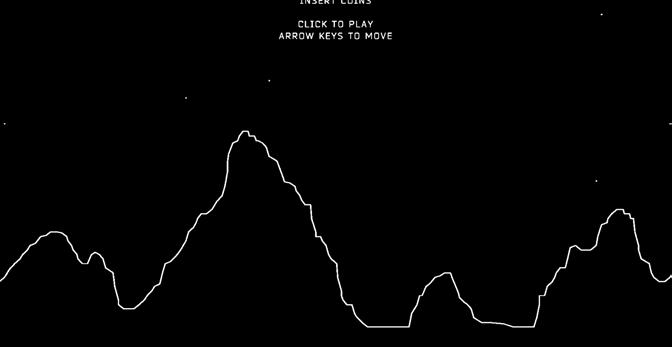

From the earliest days of electronic computers, people used them to make art: from drawings to poems, from screenplays to paintings, and from music to films. This exhibit presents breakthrough films in computer animation which created the world of cinema, gaming and television we know today.

This is a selection of short films from the dawn of computer animation, featuring the work of groundbreaking artists and computer researchers. These films document advances in computer animation, and are also artworks by some of the most important figures in computer art.

THIS COMPILATION WAS CREATED BY THE COMPUTER HISTORY MUSEUM IN MOUNTAIN VIEW, CALIFORNIA, TO EXHIBIT THERE FROM JUNE TO SEPTEMBER 2022. THIS IS ITS AUSTRALIAN PREMIERE. SPECIAL THANKS TO THE COMPUTER HISTORY MUSEUM FOR LOANING THIS WORK TO THE SCHOOL OF CYBERNETICS.

LEARN MORE ABOUT THIS COMPILATION FROM THE COMPUTER HISTORY MUSEUM.

2014 Best Festival Ever is an interactive performance a board game, theatre performance and lecture all at the same time that builds skills in understanding and managing complex systems. Using hands-on board game mechanisms, participants work together to plan and manage their own music festival, navigating a range of technical, environmental, social and economic challenges.

The game was developed by Boho Interactive, a collective of Australian artists and game designers. In researching this work, Boho worked closely with scientists from University College London’s Environment Institute, as well as drawing on work produced by CSIRO’s Complex Systems Science Team and research from the Stockholm Resilience Centre.

The game first came into the 3A Institute, a precursor to the School of Cybernetics, via staff member Amy McLennan, who believed the interactive theatre show she had seen several years earlier would be the perfect way to start a Masters program focusing on complex systems comprising people, technology and environment.

THIS GAME HAS FEATURED IN THE FIRST WEEK OF THE ANU SCHOOL OF CYBERNETICS MASTERS PROGRAM SINCE THE PROGRAM’S INCEPTION AS A WAY TO PRIME STUDENTS FOR THEIR TRAINING IN CYBERNETICS AND LAY THE FOUNDATIONS FOR COHORT COLLABORATION. WE ARE GRATEFUL TO BOHO INTERACTIVE FOR LOANING US THE GAME BOARD FOR THIS EXHIBITION.

WATCH A VIDEO ABOUT BEST FESTIVAL EVER

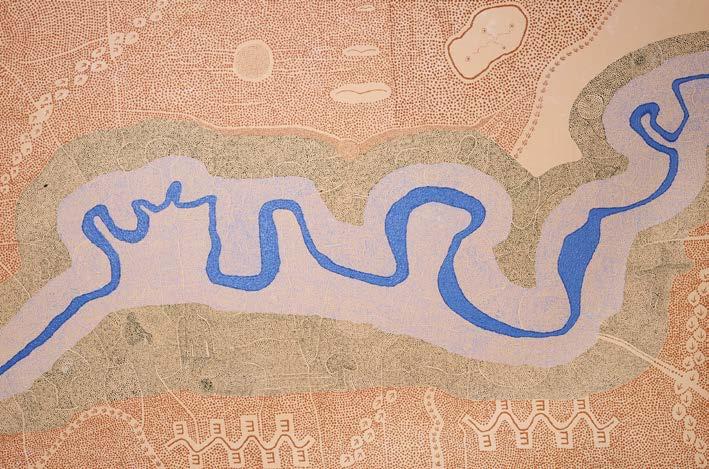

PATRICK GREEN

“Before contact we lived under the law of the Tingari. When we journey back to Kurlkurta now, there is a great tension in the car. Everyone becomes overwhelmed and cries. We mourn our ancestors and the loss of our way of life. Before there was money and possessions, even before there was time. As the first born grandson I am a Traditional Owner of this land. Going home to Kurlkurta I can reconnect with my past. I feel free.”

Patrick Green

We Were Free Before speaks to narratives of land rights, colonisation, dreaming, water and engineering. It provides a platform of discussion about how Indigenous Engineering is a transdisciplinary systems thinking approach towards solving problems.

This sculpture represents the water pumps that were installed by Patrick’s grandfather Anatjari Tjakamarra in the 1990’s deep in sacred Ngaanyajtarra country. Anatjari’s people were the last uncontacted tribe by Western culture in Australia. The installation of these water pumps enable continued access to the most significant cultural site for Anatjari’s Pintupi clan. The site is the birthplace of the Tjukurrpa people, the dreamtime people.

WE ARE GRATEFUL TO THE ANU BANDALANG STUDIO FOR LOANING US THIS WORK FOR THE EXHIBITION.

LEARN MORE ABOUT PATRICK GREEN

JOSEPH OPPENHEIMER

CIRCA 1880S

These telescoping galvanised iron telegraph poles were used as replacement poles on the Australian Overland Telegraph Line, a 3,200km telegraph line which, when completed in 1872, connected Port Augusta to Port Darwin. A submarine telegraph cable connected Port Darwin to Banyuwangi, Indonesia then onto Porthcurno, England. Suddenly, communication time between Europe and Australia was reduced from months to hours.

Poles were positioned 80m apart, with a repeater station every 250km; there were eleven repeater stations on the mainland, and over 36,000 poles. The positioning of poles traced ancient trade and communication pathways, but Traditional Owners were not consulted as the line traversed, and was supported by, their Country.

The telescoping design and oval cross-section made them easy to transport via camel or bullocky train and more efficient to install. This pole is attached to a sand anchor and has a porcelain insulator.

Taking this pole as a single vantage point from which to consider the Overland Telegraph Line is one way into a detailed cybernetic investigation of this uniquely Australian communication system.

THIS POLE WAS PURCHASED BY THE SCHOOL OF CYBERNETICS IN 2022.

WATCH GENEVIEVE BELL TALK ABOUT CYBERNETICS AND THE OVERLAND TELEGRAPH LINE

AMY MCLENNAN, JAMES TAYLOR

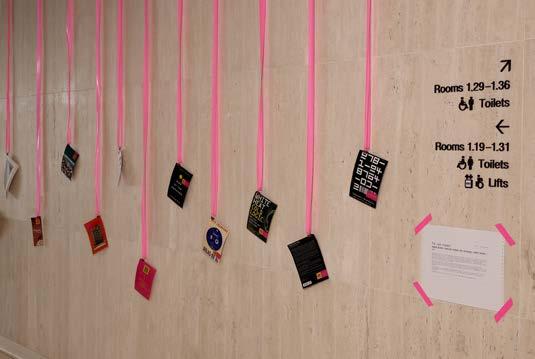

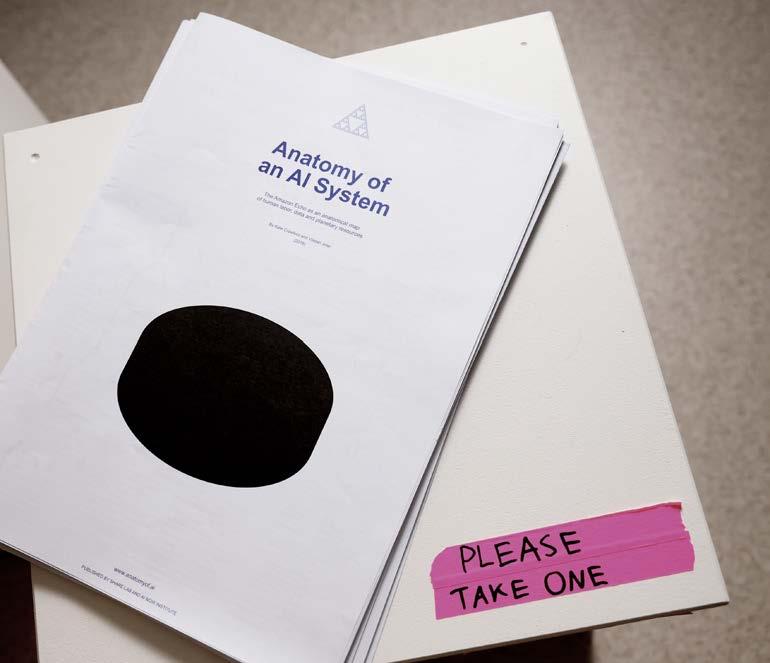

Museum and exhibition shops have been called 'the forgotten exhibit' in a museum or gallery. They trace their history to post-WWII America; the first comprehensive guide to setting up and running museum shops was written by American Kathleen Newcomb in 1968. Newcomb emphasised the potential of gift shops to educate, generate profits, promote local crafts, and build relationships with visitors.

Inspired by the use of quick response (QR) codes to create shops in South Korea and Argentina, and facilitated by the rise of codes during the COVID-19 pandemic, our store blends the physical experience of exploring a store, with the virtual experience of online shopping.

The collection includes books, videos and other resources we’ve used and loved in creating this exhibition. Some are for-purchase, others freeof-charge. Think of it as our bibliography.

Cybernetic Serendipity and Australia ‘75

Cybernetic Serendipity and Australia ‘75

The year 1968 was a touchstone for cybernetics. It was a year on from the hippies at Haight Ashbury casting off any sense of their pasts or futures during the Summer of Love. It was a year of civil unrest in Western Europe, with social movements protesting environmental damage, government control and global conflict, amplified by the new technology of television.

Between August and October 1968, Jasia Reichardt’s groundbreaking exhibition at the London Institute of Contemporary Arts, entitled Cybernetic Serendipity, helped acquaint a new generation with the ideas of cybernetics. Cybernetic Serendipity brought together art, design, and emerging technologies to catalyse new conversations about the role of computing technologies in the 20th century, and to imagine and enable new possible futures.

Reichardt convinced high levels of government, including the US Department of State, and leading technology companies at the time, like IBM, Boeing, General Motors, Bell Telephone Laboratories, to help fund it.

It was a fundamental turning point in the development of modern technology and the creative industries.

Cybernetic Serendipity featured the work of over 130 contributors - 43 were composers, artists and poets, and 87 were engineers, doctors, computer scientists and philosophers - and attracted over 60,000 visitors. The exhibition featured music, imagery, poetry, and sculptures in new media. These new forms asserted a future that would be made from plastic, copper and silicon, and which would include the impossible-seeming abilities of machines to sense and act in the world.

Jaisa Reichardt’s cybernetic playground filled 600 square metres of gallery space. The exhibition showcased 325 works from Europe, North America and Japan. It featured works from major engineering firms such as General Motors, Westinghouse, Boeing, US Air Force Research Laboratory and Bell Telephone Laboratories. It brought together artists such as Ulla Wiggen and Bridget Riley, composer John Cage, and other creatives such as Gordon Pask and Nicholas Negroponte, the latter of which would later found the Media Lab at MIT.

At a point in time when computers were still considered sophisticated calculators, and cost the equivalent of a car, Cybernetic Serendipity laid out new possibilities for what computers could be. It facilitated emergent futures in three important ways.

First, Reichardt rendered the qualifications of collaborators unimportant. She pointed out that visitors would not know who had created a work unless they had read all the notes – and that it didn’t matter. Works and the futures they envisaged were no longer constrained by ideas of which professions ought to have a say in creating the future.

Machines could be creators too. The exhibition was curated so that works made with computers or by computers sat alongside one another, dismantling the classifications of humans as creative versus machines as productive, and putting humans and the machines they build in closer, more intimate loops of interaction.

Second, the new systems created for the exhibition brought in their wake new people, people who had never before been involved in creative practice. The exhibition raised a set of questions about how we understand creativity, and about who or what we think of as having agency in authoring meaning, and in transforming the world we

inhabit. While its tangible outputs were exhibited items, the exhibition equally catalysed new relationships and collaborations that endured.

Third, it dealt in optimism for the future. The exhibition opened just a few months after the film 2001: A Space Odyssey introduced a striking vision for the future of artificial intelligence to the public that emphasised fear, loss of control, and a sense of inevitability. Cybernetic Serendipity invited the world to imagine other possible relationships between humans and machines, and humans and humans, relationships that were interactive, hopeful, and within our power to shape.

In drawing focus to cybernetic systems of interaction and influence, Reichardt offered a glimpse of a future in which computers were entangled with people, society and the world around us, and through this she fashioned a blueprint for the future of computing that has since inspired generations.

1968 (REPUBLISHED IN 2014)

Event posters do more than just convey content; they also hold traces of technologies, people and places. The poster which accompanied Cybernetic Serendipity is no different. The exhibition poster, catalogue cover art, invites, tickets and exhibition layout were designed by Franciszka Themerson, a Poland-born, London-based artist, with students from the Bath Academy of Art.

Franciszka and her husband, Stefan, had a reputation for inventing ways of doing things, from film-making techniques to printing; the publishing house they founded, Gaberbocchus Press, hosted the first club or “salon” in London in which artists and scientists could meet. Years earlier, Jasia Reichardt, Francizska’s niece, had escaped Nazi-occupied Warsaw as a nine -year-old to join them in London.

ONE HUNDRED PRINTS OF A SECOND EDITION OF THE ORIGINAL POSTER WERE PUBLISHED BY THE INSTITUTE OF CONTEMPORARY ARTS (ICA) IN 2014. THE SCHOOL OF CYBERNETICS PURCHASED THIS PRINT FROM THE ICA BOOKSTORE.

HEAR JASIA REICHARDT AND NICK WADLEY DISCUSS FRANCISZKA AND STEFAN THEMERSON

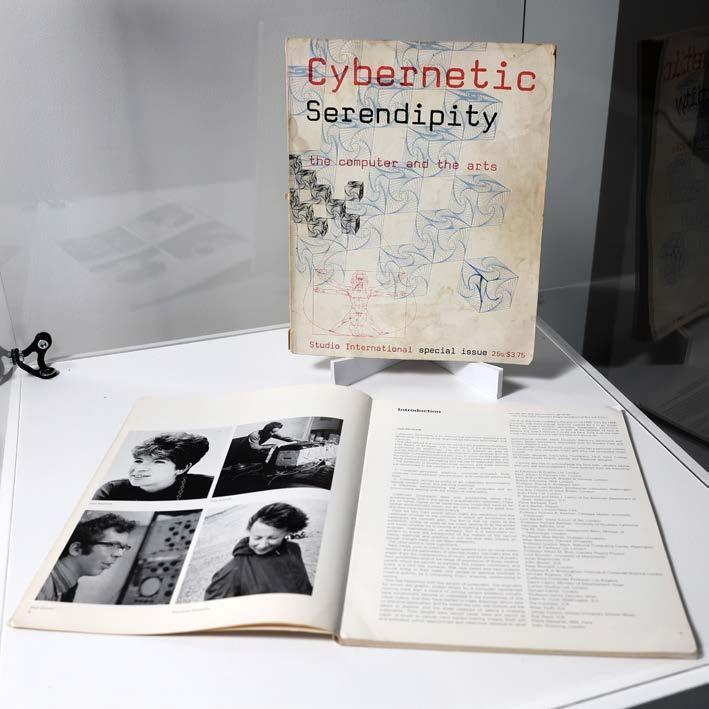

JASIA REICHARDT (EDITOR), STUDIO INTERNATIONAL (PUBLISHER)

1968

The Cybernetic Serendipity catalogue was published as a special issue by Studio International. It contained a catalogue of works, an overview of cybernetics, a long list of acknowledgements, and essays by contributors to the exhibition.

It was originally published by Studio International (London) in July 1968, with a revised edition by them in September 1968; a book edition was published by Praeger in New York in 1969, and a reprint by Studio International Foundation (London) in 2018, to commemorate the 50th anniversary of Cybernetic Serendipity.

Exhibited are an original edition plus a second edition. The latter also included a Mosaic Editions advertisement to purchase a set of artworks from Cybernetic Serendipity, a set of which (minus one, as we were not able to locate a full set to acquire) is also exhibited here. THESE CATALOGUES WERE PURCHASED FROM ANTIQUE BOOK DEALERS BY THE SCHOOL OF CYBERNETICS IN 2022.

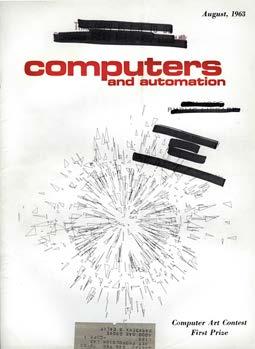

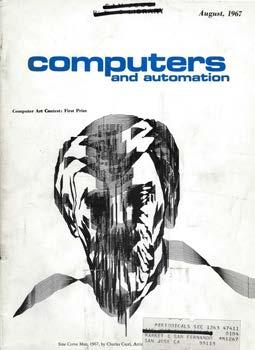

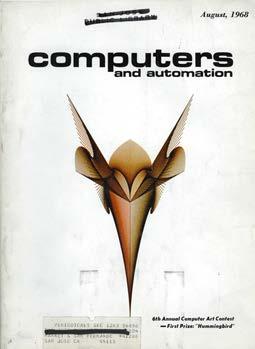

1963-68

Computers and Automation magazine was central to the early establishment of an international network of computer artists, many of which went on to feature in Cybernetic Serendipity and inspire the works at Australia ‘75 and Australian Cybernetic.

Before curating Cybernetic Serendipity, Jasia Reichardt had put on an exhibition called Concrete Poetry at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London. When Max Bense (who was linked to the Ulm School of Design) asked what she planned to work on next, she was not sure; he suggested looking at computers. She also started to encounter talks on cybernetics at Franciszka and Stefan Themerson’s Common Room arts/sciences club. At the time, “using computers to make art” was a very bold assertion and it was controversial at times, so

controversial that industry groups like Boeing framed technical drawings by engineers as “graphics” instead of “art”.

As Reichardt began to do research, she found a US trade magazine called Computers and Automation (originally called Roster of Organizations in the Field of Automatic Computing Machinery, and later The Computing Machinery Field). Edmund Berkeley and Grace Hertlein had initiated a computer art competition in the journal in 1963. With a small research grant, Reichardt travelled to the US to meet some of the practitioners who had won the contest, including A. Michael Noll. The results of her research, vision, relationship-building and curation stand around you today.

WE ARE GRATEFUL TO EDMUND C. BERKELEY, PUBLISHERS OF COMPUTERS AND AUTOMATION SINCE 1950, FOR THEIR PERMISSION TO SHOW THESE COVERS.

READ ABOUT THE COMPUTER ART CONTEST IN COMPUTERS AND AUTOMATION

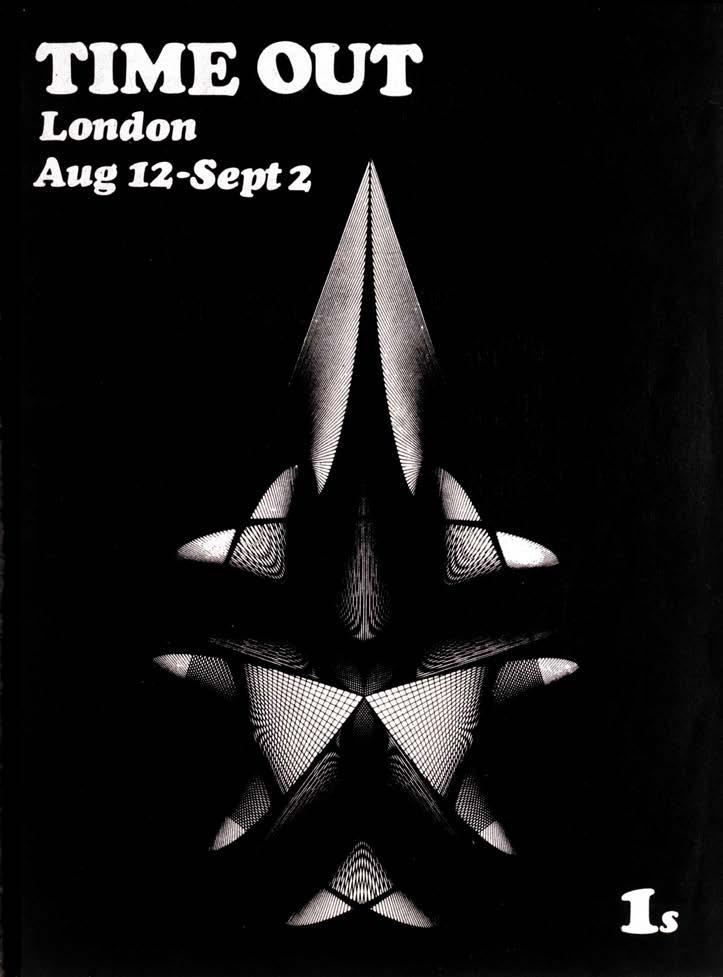

TONY ELLIOTT (EDITOR)

The first ever edition of Time Out Magazine featured a publicity shot from the Cybernetic Serendipity exhibition on the cover, and an advertisement for the exhibition inside its pages. The choice of cover would shape the cover style of the magazine in the years that followed, setting it apart as a publication that captured a cultural moment in time.

Time Out founder Tony Elliott was just 21 years old when he selected the Cybernetic Serendipity image to feature on the cover of the magazine, which was an A2 sheet folded into an A5 booklet that he handed out himself. He recalled later that featuring the exhibition, “...didn’t stereotype Time Out as a hip music or fashion magazine. It felt completely right.”

Time Out transformed from a booklet that kept pace with shifting cultural values in a way that established news media couldn’t, to a global media brand in 328 cities across 58 countries around the world. Today, it is a fully-digital publication.

THIS ITEM IS EXHIBITED WITH THANKS TO THE TIME OUT GROUP. READ

1968

This interactive sculpture was comprised of two male and three female elements engaging in communication with each other that Pask called an “aesthetic potential environment”. The rotating components hung from the ceiling communicated with each other by light and sound; visitors could use flashlights and mirrors to participate in, or influence, the conversation between the machines.

Pask, a cyberneticist, concieved the mobiles as a gendered social system, in order to give the communication between the machines significance. Their communication was clearly based on a sexual analogy; the goal of communicating was to achieve a moment of satisfaction, and the mobiles learned to optimise their behavior to reach this moment using the least amount of energy.

WITH THANKS TO JASIA REICHARDT FOR HER PERMISSION TO INCLUDE THIS PHOTOGRAPH IN THE EXHIBITION.

VISIT A RECREATION OF PASK’S CONVERSATIONAL MACHINES

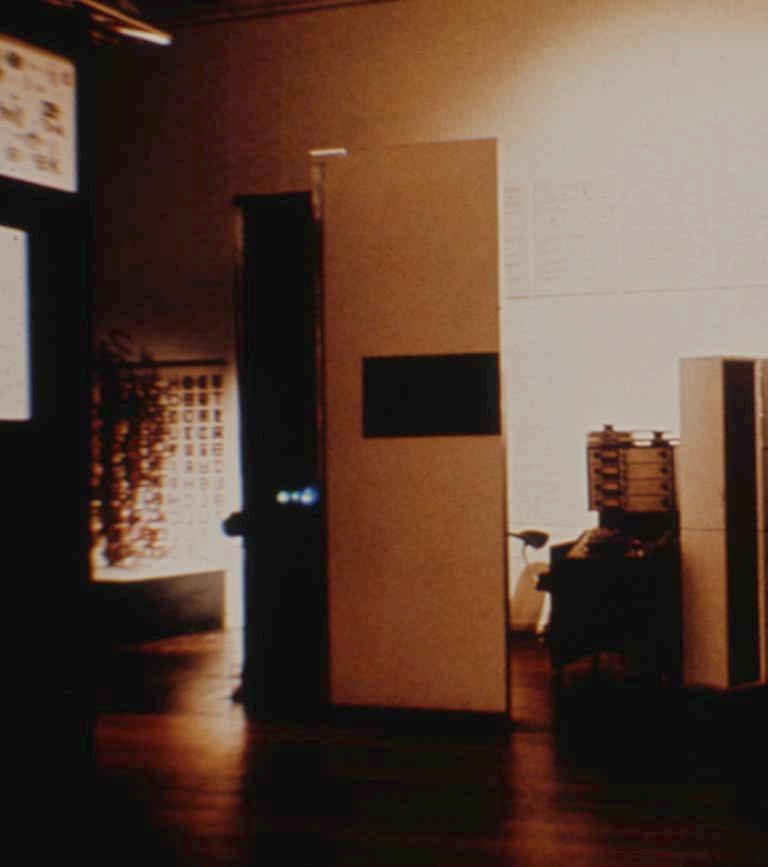

PETER ZINOVIEFF

1968

“Digital Computers and new electronic circuits can make possible the direct translation of of scores into music, and the control produced is the result of compositional rather than technical skill... Another way of putting this is that with computer techniques you can control the lack of control and you may have choice or no choice” Peter Zinovieff, 1968.

ZINOVIEFF WROTE A SHORT ESSAY ABOUT HIS WORK FOR THE CYBERNETIC SERENDIPITY EXHIBITION CATALOGUE; THIS QUOTE IS JUST ONE EXCERPT.

WITH THANKS TO JASIA REICHARDT FOR PERMISSION TO INCLUDE THIS PHOTOGRAPH OF ZINOVIEFF'S ELECTRONIC MUSIC STUDIO AT CYBERNETIC SERENDIPITY.

1968 (REISSUED ON VINYL IN 2014)

The first computer-generated musical melodies can be traced to Australia’s CSIRAC in the early 1950s. Over a decade later, Cybernetic Serendipity Music was the first record to include music composed and performed by a computer.

Music was situated in the heart of the 1968 exhibition, which included a large music computer and four domes in which visitors could listen to twelve minute loops of music that were rotated daily.

Creation of the music featured at Cybernetic Serendipity involved some extraordinary people. Many of them had deeply interdisciplinary backgrounds: Lejaren Hiller was a composer who had also been a chemist at DuPont, Wilhelm Fucks was a musicologist trained in theoretical physics and with expertise in demography, Iannis Xenakis was a music theorist, civil engineer and architect, and Peter Zinovieff was an engineer, composer and business founder.

The album was compiled by Peter Schmidt, a painter who had performed an electronic music concert entitled A Painter’s Use of Sound at the ICA in 1967, and who would go on to collaborate with Brian Eno.

The music, and accompanying essays, raised questions about the relationship between the programmed and the spontaneous, systematisation and chance, science and the arts, circular dynamics, and computers as instruments and collaborators.

THE 1968 ALBUM WAS REISSUED ON VINYL IN 2014 BY THE INSTITUTE OF CONTEMPORARY ARTS AND THE VINYL FACTORY, LONDON. THIS COPY WAS GIFTED TO THE SCHOOL OF CYBERNETICS BY UNCANNY VALLEY. WE ARE GRATEFUL TO THE VINYL FACTORY AND FILMMAKER/PRODUCER JOHNATHAN HOMER FOR THEIR PERMISSION TO INCLUDE THE LINK TO THE FILM IN THIS EXHIBITION.

LISTEN TO THE FULL ALBUM AND WATCH A SHORT FILM ABOUT THE MUSIC OF CYBERNETIC SERENDIPITY

PHOTOGRAPHER UNKNOWN

1968

Cybernetic Serendipity was visited by all sorts of people, attracted and enthralled by glimpses of the new and exciting world the exhibition invited them to explore. Among the visitors was Princess Margaret, younger sister to Queen Elizabeth II, who was in her late thirties at the time of the exhibition.

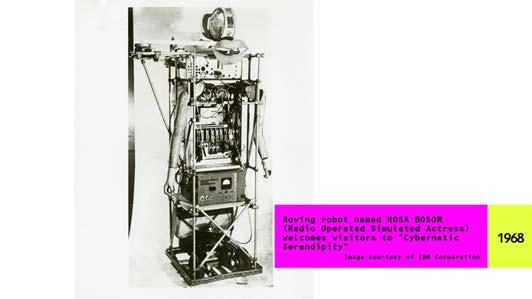

As a member of the Royal Family, Princess Margaret’s particular interests were welfare and the arts, especially music and ballet. She and Lord Snowdon, her then-husband, visited the exhibition. They saw Bruce Lacey’s robots ROSA BOSOM (Radio Operated Simulated Actress - Battery Or Standby Operated Mains) and companion MATE, which followed ROSA around. They also listened to experimental computergenerated music (featured on the previous page) in the ball-shaped space pictured here.

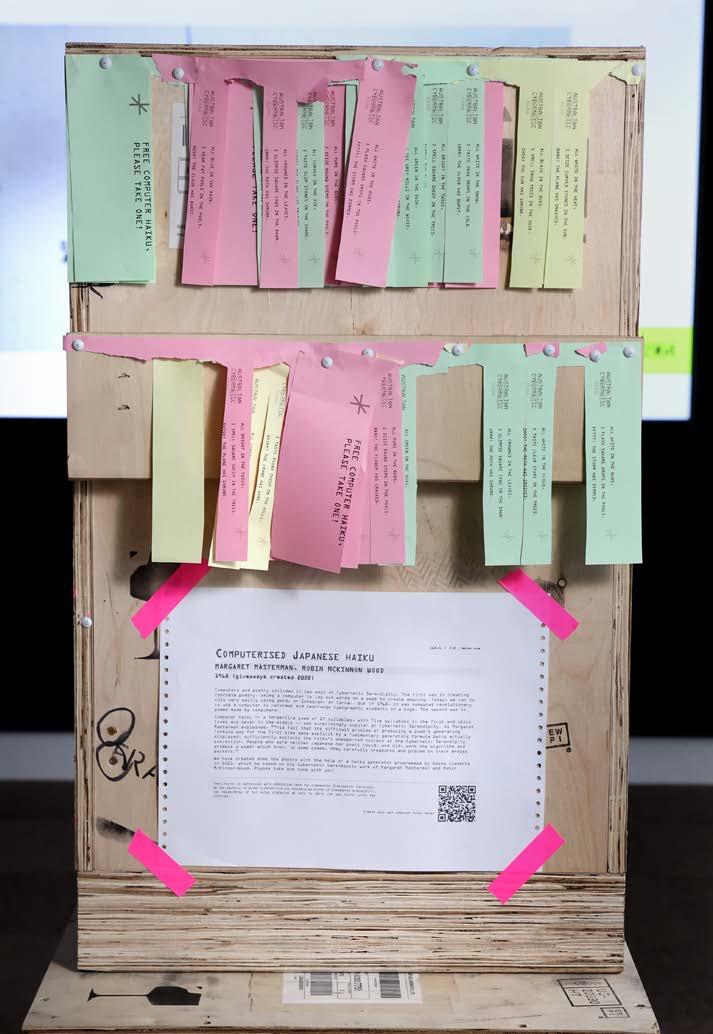

Computers and poetry collided in two ways at Cybernetic Serendipity. The first was in creating concrete poetry, using a computer to lay out words on a page to create meaning. Today, we can do this very easily using Word, or InDesign, or Canva, but in 1968, it was somewhat revolutionary to use a computer to reformat and rearrange typographic elements on a page. The second was in poems made by computers.

Computer haiku a three-line poem of 17 syllables, with five syllables in the first and third lines and seven in the middle was surprisingly popular at Cybernetic Serendipity. Margaret Masterman explained, "This fact that the difficult problem of producing a poem’s generating formula was for the first time made explicit by a rudimentary generating formula being actually displayed, sufficiently explains the haiku’s unexpected success at the Cybernetic Serendipity exhibition. People who were neither Japanese nor poets could, and did, work the algorithm and produce a poem; which then, in some cases, they carefully treasured and placed in their breast pockets.”

We have created some new poetry gifts with a haiku generator programmed by Wayne Clements in 2003, which he based on the Cybernetic Serendipity work of Margaret Masterman and Robin McKinnon-Wood.

THIS POETRY IS REPRODUCED WITH PERMISSION FROM THE CYBERNETIC SERENDIPITY CATALOGUE. WE ARE GRATEFUL TO WAYNE CLEMENTS FOR HIS RESEARCH ON POETRY AT CYBERNETIC SERENDIPITY, AND PROGRAMMING OF THE HAIKU GENERATOR WE USED TO WRITE OUR OWN POETRY GIFTS FOR VISITORS.

CREATE YOUR OWN COMPUTER HAIKU

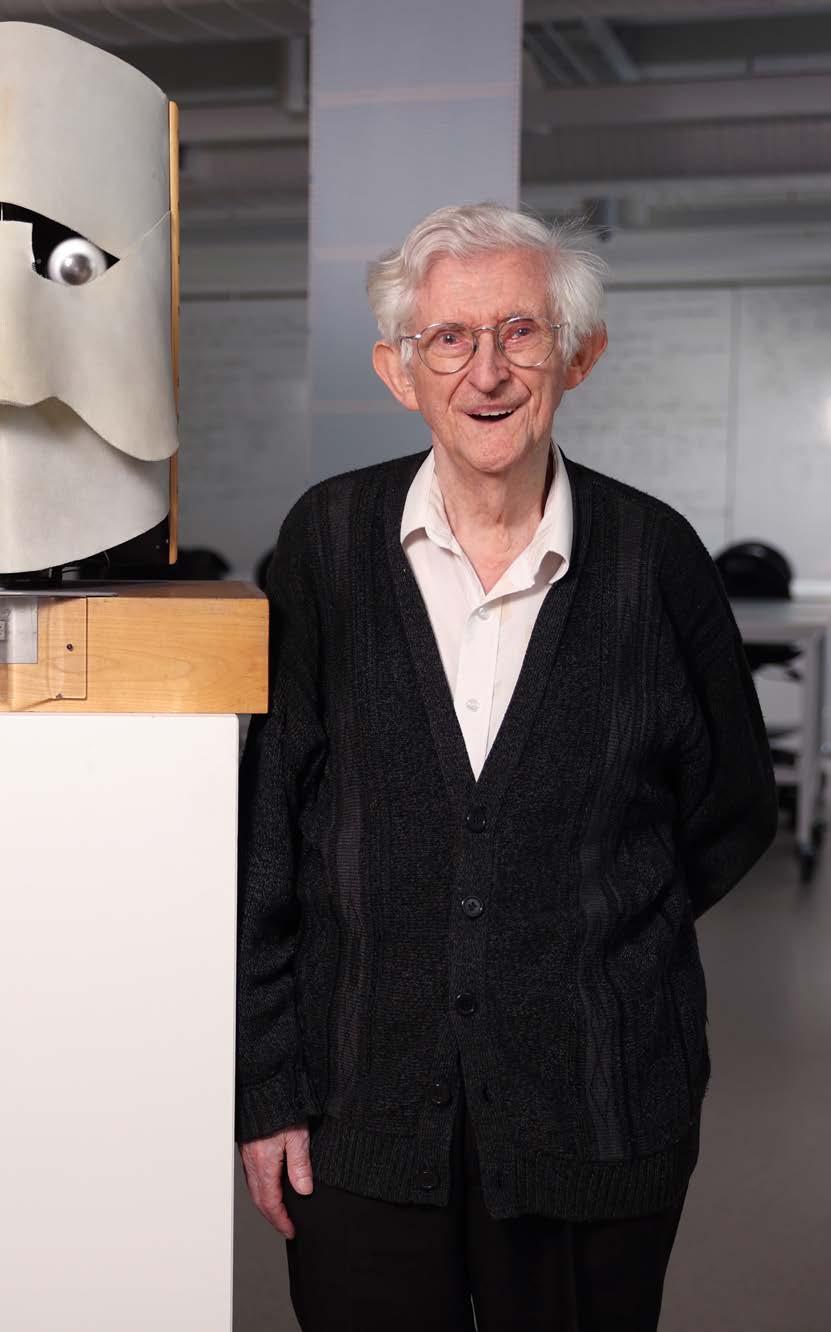

JOHN BILLINGSLEY

Albert has been delighting audiences for over 50 years. He can “see” by using a photocell to detect light and dark areas. The brightness difference is translated into a voltage, which determines the direction the motors rotate Albert’s face; when the light is even the rotation stops and Albert pauses to “look” at you. At Cybernetic Serendipity, this early machine behaviour, making an object seem alive, startled and intrigued visitors.

John Billingsley has now created four versions of Albert. The first was in 1963, for a graduate apprenticeship exhibition while he was working at Smiths Aerospace. He named the work “Albert” in jest of their supervisor named Albert. This first Albert no longer exists.

The second was for the Cybernetic Serendipity exhibition in 1968, which is pictured here, affixed to the side of the box in which the third Albert travelled to Canberra. In searching for objects for Cybernetic Serendipity, curator Jasia Reichardt came across another of Billingsley’s inventions at a trade show at Festival Hall in London. When she asked if he had any other devices, he responded by rebuilding Albert in his Cambridge University lab.

WITH THANKS TO PROFESSOR JOHN BILLINGSLEY, WHO NOW LIVES AND WORKS IN AUSTRALIA, FOR RETELLING ALBERT STORIES, SHARING CONTROL THEORY KNOWLEDGE, AND HIS ENTHUSIASM “TO AMUSE PEOPLE”.

LEARN MORE ABOUT JOHN BILLINGSLEY’S WORK ON HIS WEBSITE

1968

Dioximoirékinesis is a combination of three words. The first, ‘Dioxi-,’ from the Greek for pursuit, refers to the inspiration for the pattern: three beetles pursuing each other.

The second, ‘moiré,’ refers to large-scale interference patterns produced when an opaque ruled pattern with transparent gaps is overlaid on another similar pattern, creating new patterns together. Moiré patterns are often an artefact of images produced by various digital imaging and computer graphics techniques.

The third, ‘kinesis,’ refers to the role of the viewer: by moving around the room, the viewer animates the pattern, creating a pulsing artwork in a black box.

The piece was imagined by mathematician Irving John Good, and created by artist Martine Vite to his specifications. To discuss their work they had to meet in a café because Good’s office only had one chair. Dioximoirékinesis is a part of the collection at the Exploratorium in San Francisco.

THIS PIECE IS ON LOAN FROM THE EXPLORATORIUM IN SAN FRANCISCO, AND WE THANK THE STAFF THERE FOR THEIR GENEROSITY AND ASSISTANCE.

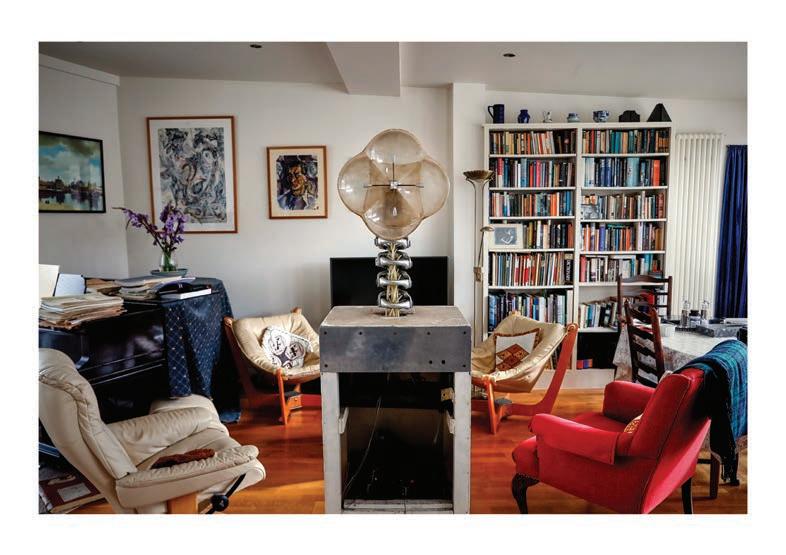

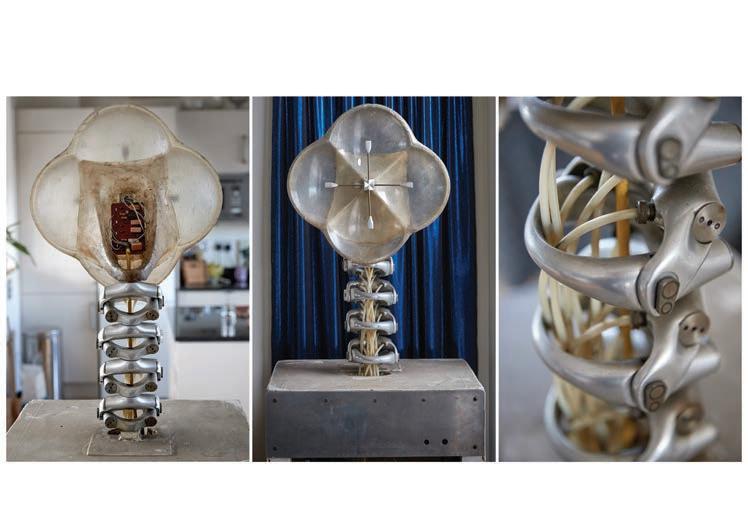

1968 (PHOTOGRAPHED 2022)

SAM was arguably the first ever sculpture to move in direct response to sounds around it. Observers were fascinated by SAM’s behaviour, just as we continue to be fascinated by responsive objects today.

SAM appeared at Cybernetic Serendipity in an otherwise quiet room. According to Alex Zivanovic, a scholar of Edward Ihnatowicz, “since the sculpture was sensitive to quiet but sustained noise, rather than shrieks, a great many people spent hours in front of SAM trying to produce the right level of sound to attract its attention.”

Following Cybernetic Serendipity, SAM toured Canada and the US, ending at the Exploratorium in San Francisco. Today, SAM has retired to the living room of the London flat of Edward Ihnatowicz’s son Richard, which is where it is pictured in this photograph.

THE SCHOOL OF CYBERNETICS COMMISSIONED KIRAN RIDLEY TO PHOTOGRAPH SAM IN RICHARD’S LIVING ROOM. WE ARE GRATEFUL TO ALEX ZIVANOVIC FOR MAKING THE CONNECTIONS, AND RICHARD IHNATOWICZ FOR SO GENEROUSLY INVITING US INTO HIS LIVING ROOM.

WATCH A VIDEO OF SAM AND READ A DESCRIPTION OF SAM BY ALEX ZIVANOVIC

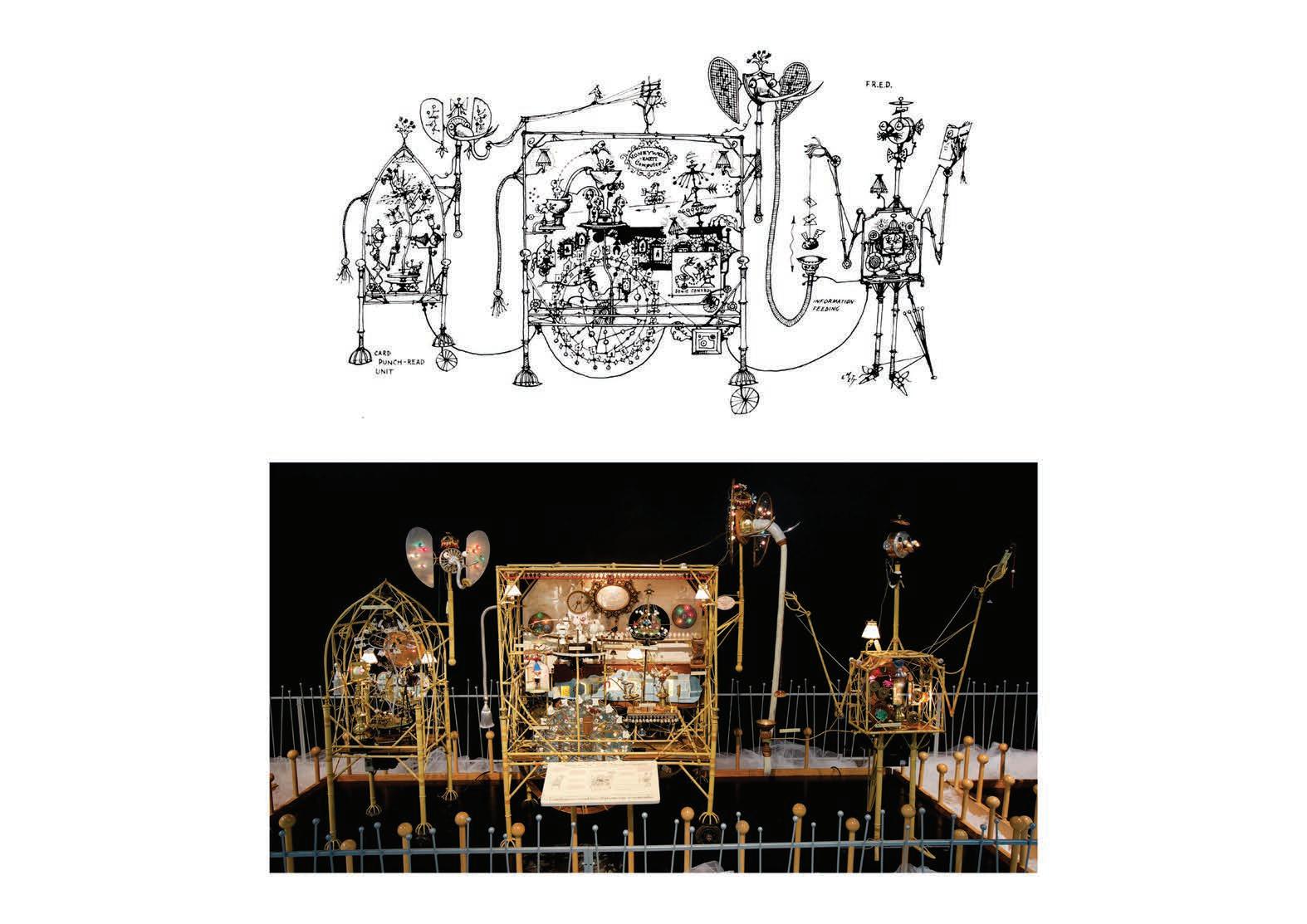

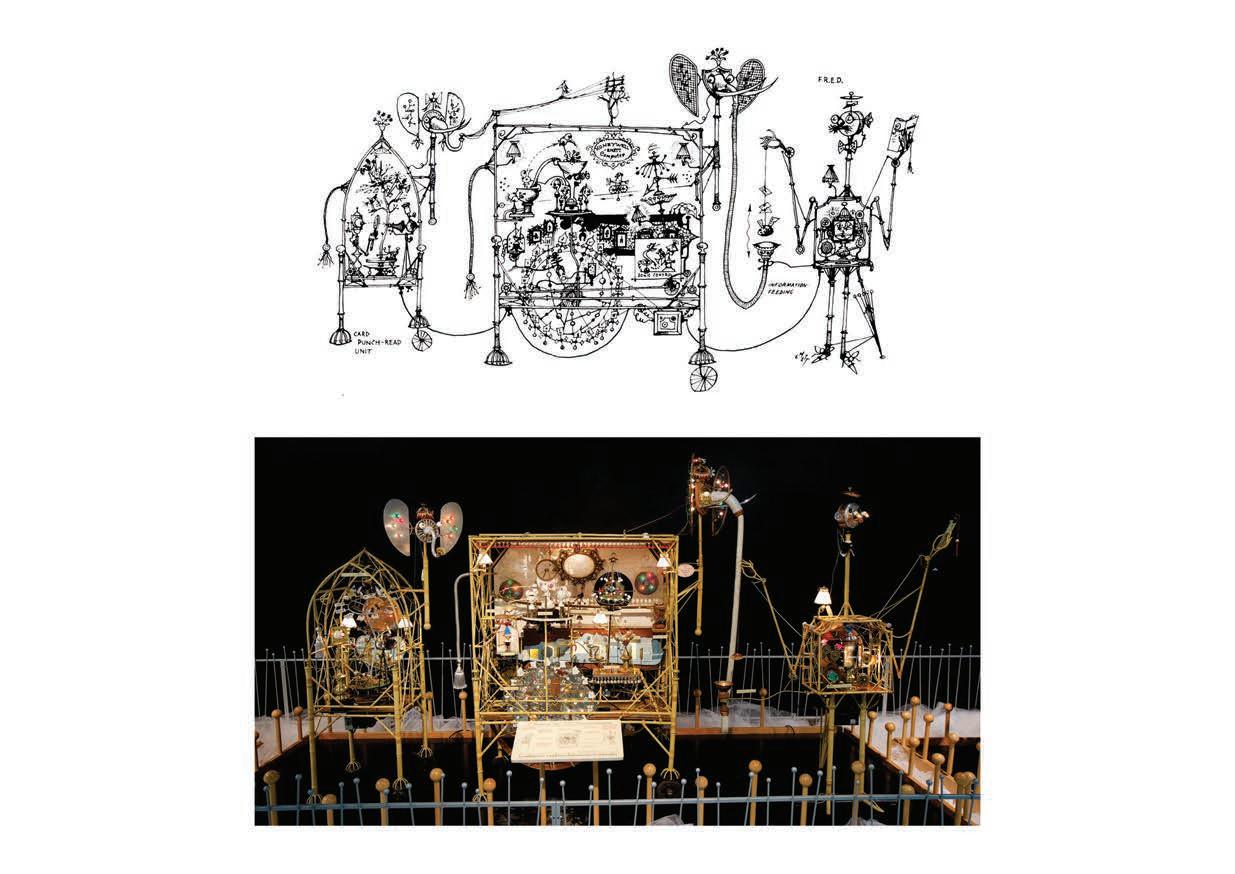

ROWLAND EMETT

1966

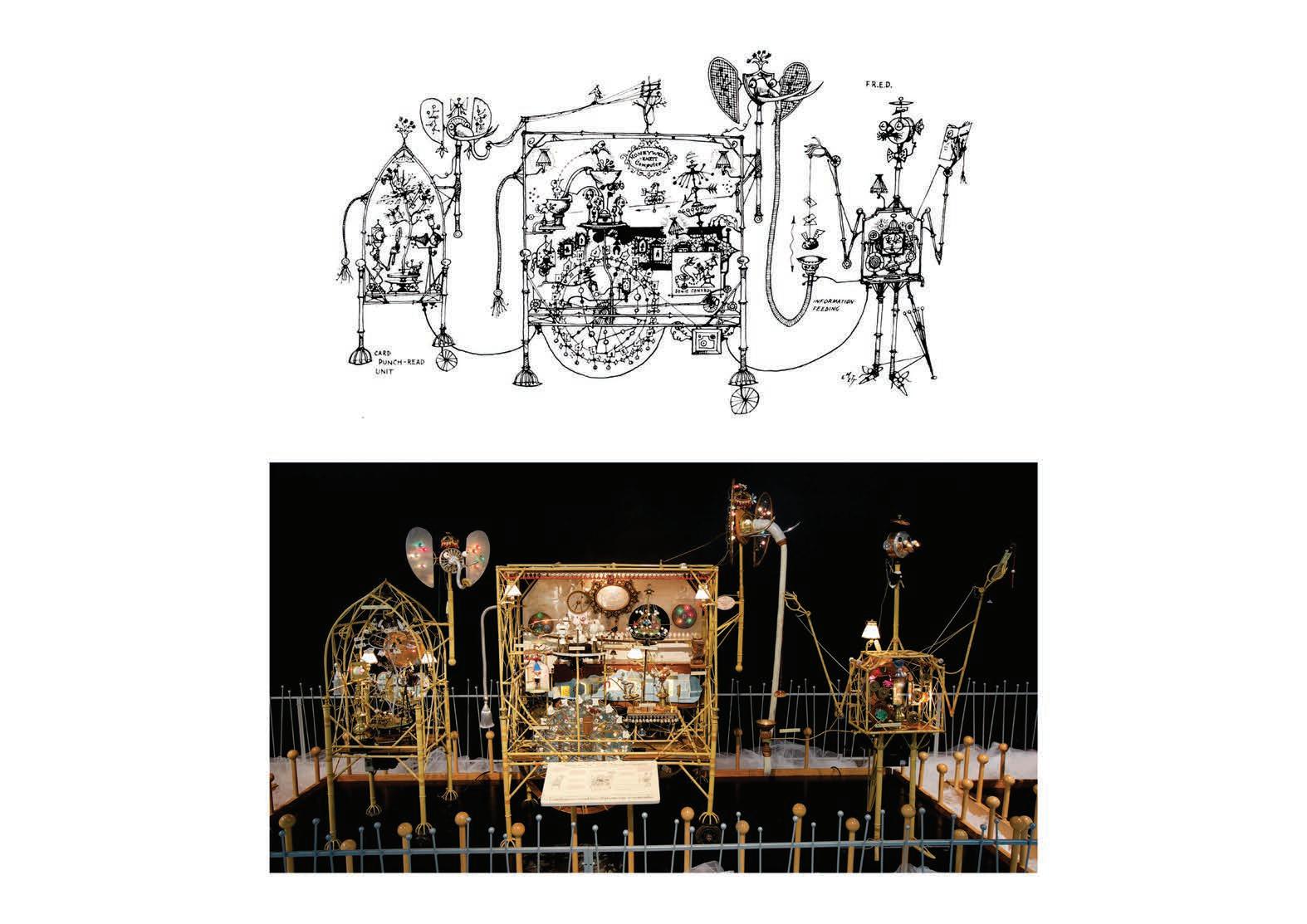

‘miniature minds’ attempting to compile ‘mass memories’.

The Forget-Me-Not is accompanied here by two peripheral units: F.R.E.D. (Fantastically Rapid Evaluator and Dispenser) who teases the machine with a pre-loaded information bun and the Card Punch Reader made up of Electronic Woodpeckers and a single Inscrutable Eye. In Emmet's words about his riff on modern computing, "people think they're dotty, but there's a profound logic in these things."

The Computer still works, and is exhibited every Christmas at the Ontario Science Centre, Canada.

WITH THANKS TO THE ONTARIO SCIENCE CENTRE FOR PRESERVING THIS INCREDIBLE KINETIC SCULPTURE AND SHARING THESE IMAGES WITH US.

CHECK OUT EMETT’S COMPUTER IN ACTION IN 1966

PHOTOGRAPHER UNKNOWN 1968

The Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) was founded in 1946 by artists and poets as an alternative to the mainstream. It was a space where artists, writers and scientists could debate ideas outside of traditional institutions such as the Royal Academy. It was home to the Cybernetic Serendipity exhibition, pictured here.

In the ICA’s own words: “In our landmark home on The Mall in central London, we invite artists and audiences to interrogate what it means to live in our world today, with a genre-fluid programme that challenges the past, questions the present and confronts the future. The cross-disciplinary programme encourages these art forms and others to pollinate in new combinations and collaborations.”

UNKNOWN

PHOTOGRAPHER

1968

The Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) was founded in 1946 by artists and poets as an alternative to the mainstream. It was a space where artists, writers and scientists could debate ideas outside of traditional institutions such as the Royal Academy. It was home to the Cybernetic Serendipity exhibition, pictured here.

In the ICA’s own words: “In our landmark home on The Mall in central London, we invite artists and audiences to interrogate what it means to live in our world today, with a genre- fluid programme that challenges the past, questions the present and confronts the future. The cross-disciplinary programme encourages these art forms and others to pollinate in new combinations and collaborations.”

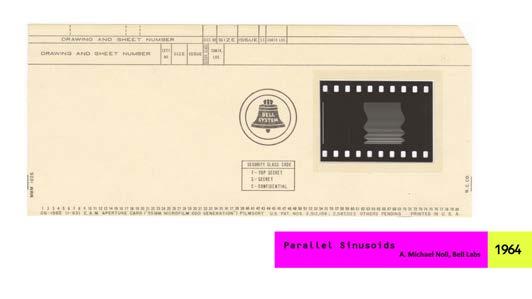

1962-65

A. Michael (Mike) Noll created his first digital computer art at Bell Labs in Murray Hill, New Jersey, in 1962; he recorded his experiments in a Technical Memorandum. At the time, Bell Labs was focused on communications (broadly defined) and human-machine communication; it was home to creative researchers, open-minded management, secure and stable funding, excellent facilities, and a vibrant array of visitors and residents. Shown here are four of his works in art, computer graphics and animation from that period.

One of these, Computer Composition with Lines (1964), was an algorithmic reproduction of Piet

Mondrian’s spherical Composition with Lines (1917). Noll went on to carry out research with the two works, asking an audience of 100 people to compare the them. He found that on average, subjects both preferred the computer-generated version and failed to identify it was the computer-generated one.

Noll’s work also won first prize in August 1965 in the contest held by Computers and Automation magazine, which is where Jasia Reichardt encountered his work.

WE ARE GRATEFUL TO MIKE NOLL FOR PERMITTING US TO INCLUDE THESE WORKS IN THE EXHIBITION, AND FOR SO GENEROUSLY SHARING HIS MEMORIES, WRITINGS AND PUBLICATIONS WITH US.

READ MORE ABOUT EARLY DIGITAL ART AT BELL LABS

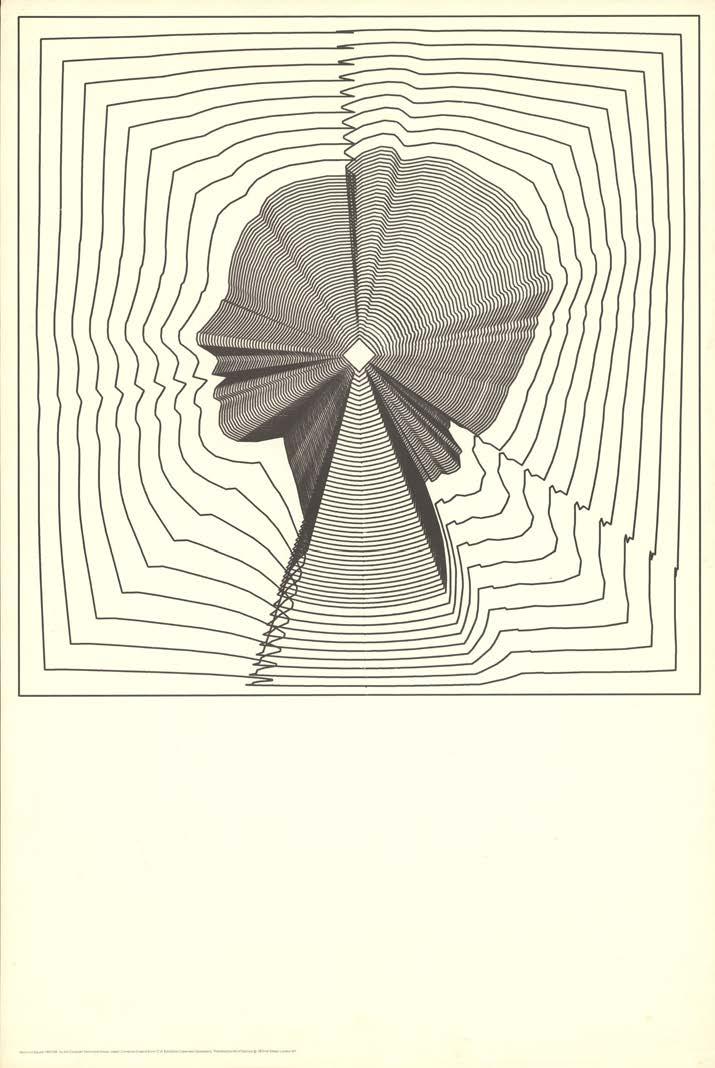

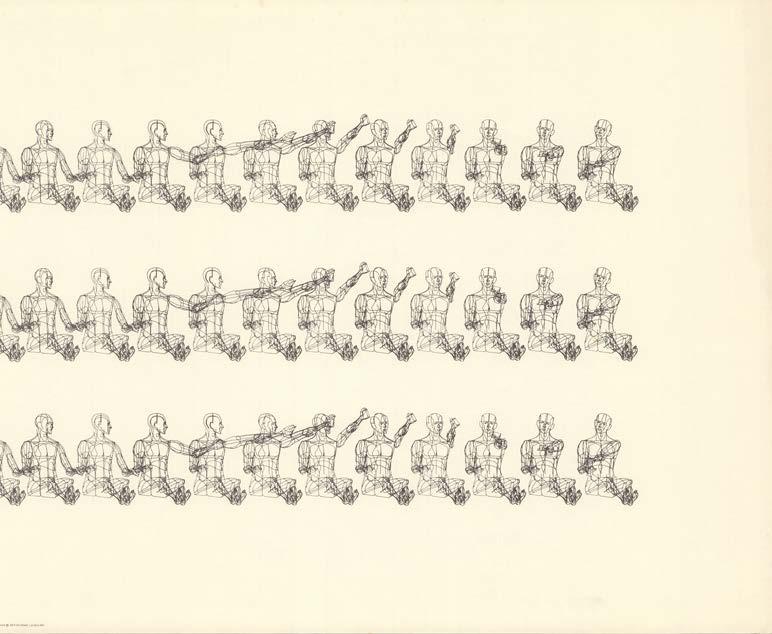

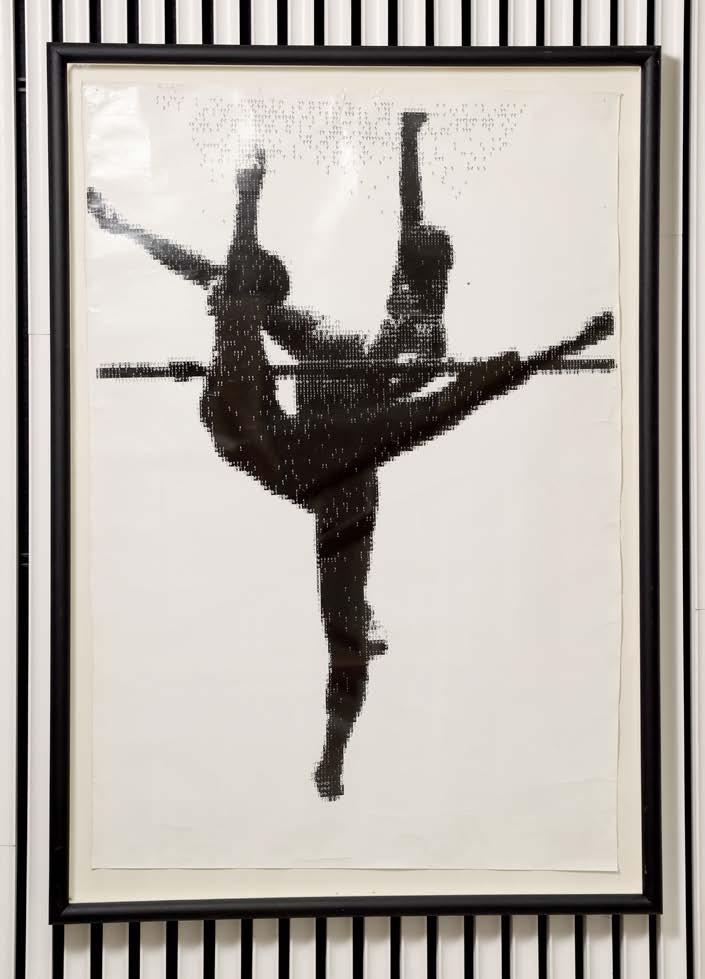

A. Michael Noll began experimenting with digital art in the US summer of 1962 while working at Bell Telephone Laboratories. By 1965, he had created the first computer animation of a three-dimensional human figure. The BBC showcased the work in a 1968 documentary. Noll developed this work after going on a date to a ballet performance in New York. In Noll's words, his idea "was to interest choreographers and dance groups with the possibility of getting themselves involved with the computer to help during the creative process...".

He went on to use his four-dimensional computer animation method to create the title sequences for the film Incredible Machine, which showcased some of the ways that Bell Laboratories scientists were using computers in communications research. Some of their firsts included work in digital computer art, music, graphics, animation language and ASCII art (forming art out of text characters).

WE ARE GRATEFUL TO QUESTACON AND CANDICE ADDICOTE FROM THE GREEN SHED, CANBERRA, FOR HELPING US TO ARRANGE A LOAN OF THEIR NEW/OLD TELEVISION SET TO DISCPLAY THIS WORK.

LEARN MORE ABOUT THE ANIMATION AND VIEW "INCREDIBLE MACHINE"

1968, COMPILED 2022

This screen shows images from the Cybernetic Serendipity exhibition in 1968. The slides were compiled by Ken Wheeler, drawing on collections identified throughout the exhibition team’s research and development work for Australian Cybernetic.

The images are displayed on a Panasonic TH-98SQ1W 4K screen; its 98-inch surface has a response time of 8ms and a resolution of 3840 x 2160 lines of pixels. It cannot be compared to computer screens from 1968, because the first computer monitor wasn’t released until 1973.

THANKS TO KEN WHEELER FOR HIS ASSISTANCE IN COMPILING THIS SLIDE SHOW.

1966-69

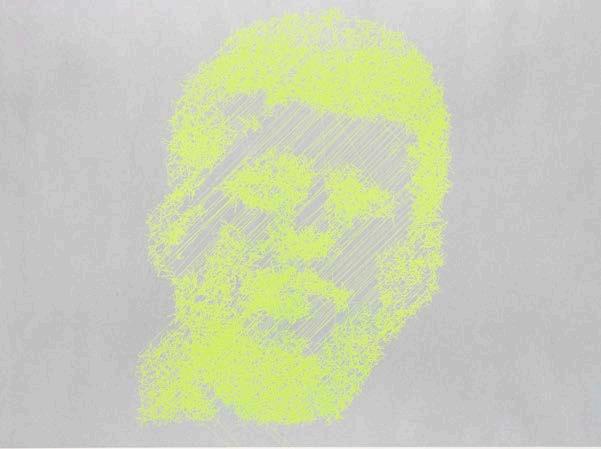

The CTG was a Japanese collective who considered the computer as a medium of creativity. They did a variety of creative works, including computer graphics, illustration and typography. While the fonts that could be printed out on the plotters of the time were extremely limited, the CTG innovated in significant ways.

Their Computer Design Series comprised of three works focusing on illustration and typography. No. 2 in the series featured the John F. Kennedy print shown here. The works were entered in the Japan Advertising Artists

Club competition, the most prestigious graphics competition in Japan at the time. Although they did not win, the computer graphic of Kennedy became synonymous with their work.

THIS MATERIAL BECAME AVAILABLE TO US THANKS TO THE ASSISTANCE OF KAZUFUMI OIZUMI, A FORMER PHD STUDENT OF MASAO KOHMURA. WE ARE GRATEFUL FOR HOW GENEROUSLY HE SHARED THESE WORKS WITH US, AND HOW MUCH TIME AND CARE HE PUT INTO TRANSLATING HIS CORRESPONDENCE INTO ENGLISH.

VIEW THE FULL COMPUTER DESIGN SERIES ON THE JAPAN GRAPHIC DESIGN ASSOCIATION WEBSITE

1968

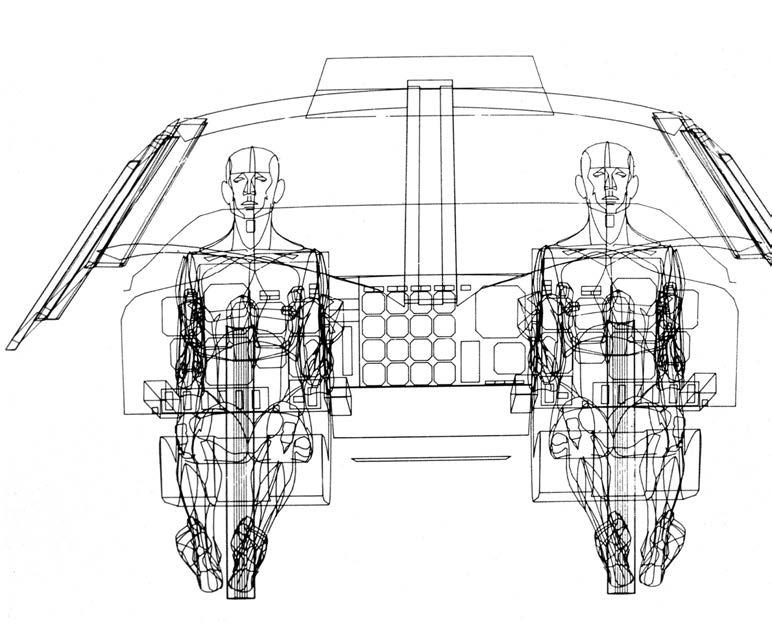

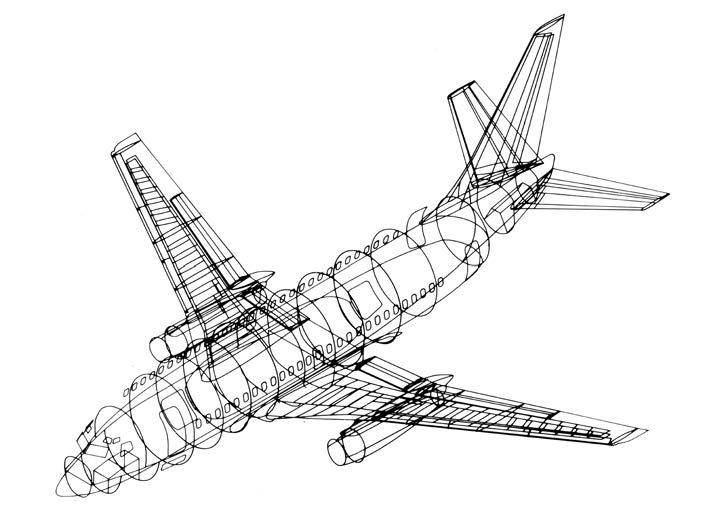

The Boeing Computer Graphics organisation collaborated with engineers and management across the company to visualise specific problems in aircraft and their surroundings (airports or in flight). Boeing employee William Fetter coined the term “Computer Graphics” to describe this work. This was the first time computers were used for flight simulation.

Boeing developed a new form of data visualisation. Data sources for the development of graphics varied, from anthropomorphic data on Air Force pilots, to measurements from the master plan of the SeattleTacoma Airport, to flight data from aircraft such as speed and elevation.

WE ARE GRATEFUL TO BOEING FOR GIVING US THESE IMAGES TO USE IN THE EXHIBITION.

CHECK OUT THE FIRST FIRST-PERSON CGI 3D SIMULATION OF AN AIRCRAFT

A. MICHAEL NOLL

1964

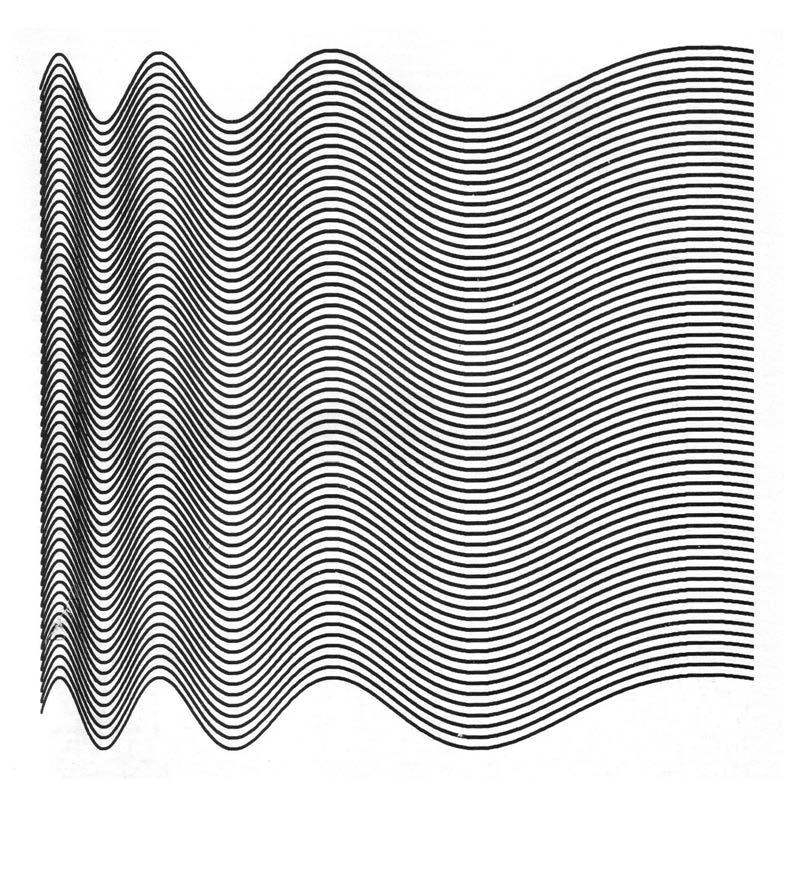

Engineer A. Michael Noll’s work at Bell Labs in the 1960s made him an early innovator in digital computer art.

This is a print of a computer-generated image created by Noll in 1964. The artist has stated that “The top sinusoid was expressed mathematically and then repeated again and again. The result closely approximates the pop-art painting Current by Bridget Riley.”

In Riley’s painting, also from 1964, she sought to make the space between picture and spectator active; undulating black and white lines made the painting appear to vibrate and form three-dimensional depressions that quivered on the painting’s surface. Computer art was in direct dialogue with other explorations in the art world.

Noll’s works, along with those of Bela Julesz, formed the basis of an early public exhibit of digital art in the US, at the Howard Wise Gallery in New York City in April 1965. Part of the press release for the exhibition read:

“Presently, computer-generated pictures are limited solely by the state of the computer and microfilm art. Noll and Julesz see the day when a computer can draw - or paint - almost any kind of picture in any one or combination of colors. Both scientists stress, however, that the artist need not fear being automated out of existence; rather, as they see it, the computer will free the artist for creation, unburdened by the tedium of the mechanics.”

WE ARE GRATEFUL TO MIKE NOLL FOR HIS PERMISSION TO SHOW THIS WORK AT THIS EXHIBITION, AND FOR SO GENEROUSLY SHARING HIS MEMORIES, WRITINGS, AND PUBLICATIONS WITH US.

LEARN MORE ABOUT NOLL, AND READ MORE ABOUT THE EXHIBITION AT HOWARD WISE GALLERY

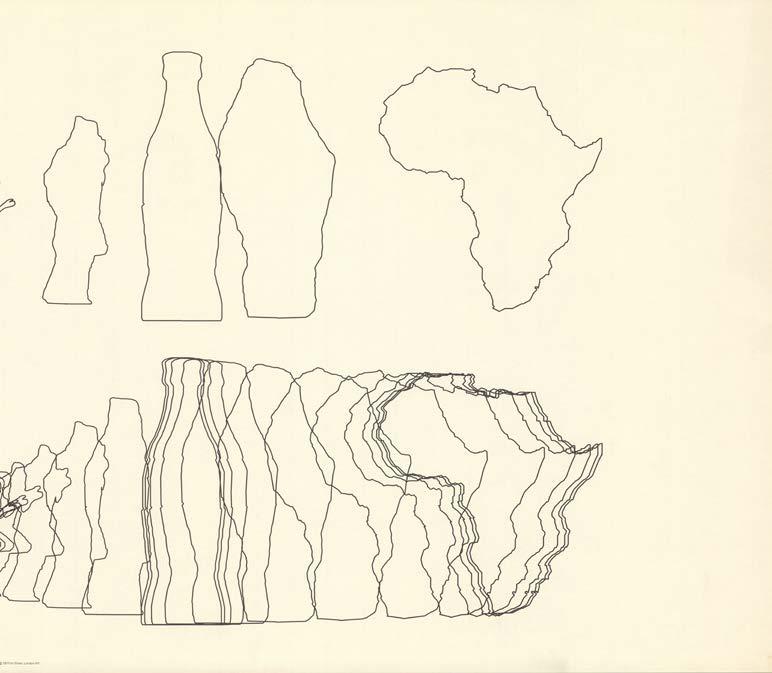

MASAO KOHMURA AND KUNIO YAMANAKA / COMPUTER TECHNIQUE GROUP

1968

Return to a square (a) is an early example of morphing. The Computer Technique Group (CTG) was the first to produce morphing works of computer graphics; it was another two decades before digital morphing would become more common in motion pictures and animations. The work was created by members of the CTG, a Japanese collective of art and engineering students founded in 1966; it initially included Masao Kohmura (a product designer who had the idea for this piece) and Haruki Tsuchiya (a systems engineer), as well as Kunio Yamanaka (an aeronautical engineer who created the program for this work) and Junichiro Kakizaki (an electronics engineer).

Like all works exhibited at Cybernetic Serendipity, this work was created with no personal computers, no internet, no computer monitors, and using expensive computers that had to be accessed on the site at which they were installed.

ON PAGE 104 OF THE SECOND EDITION OF THE CYBERNETIC SERENDIPITY CATALOGUE (1969), MOTIF EDITIONS OFFERED FOR SALE SEVEN LITHOGRAPHS OF IMAGES FROM THE EXHIBITION. THE SCHOOL OF CYBERNETICS FOUND SIX OF THESE OFFERED FOR SALE THROUGH A SECONDHAND ART DEALER IN THE UK, AND PURCHASED THEM IN 2022.

MASAO KOHMURA, MAKOTO OHTAKE, KOJI FUJINO / COMPUTER TECHNIQUE GROUP

1968

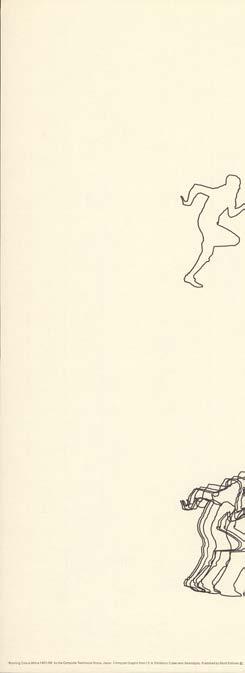

The Computer Technique Group from Japan contributed 24 computer graphics to Cybernetic Serendipity, as well as works of computer poetry. This conversion of a running man into a bottle of cola into a map of Africa was conceived by Masao Kohmura; Makoto Ohtake worked with the data and Koji Fujino was responsible for the program.

Like all their graphics, it was programmed in Fortran IV, a programming language IBM began developing in 1961, on an IBM 7090, a system which typically sold for US$2.9m in 1960 (around US$20m in 2021 terms), and drawn on a Calcomp 563 plotter.

ON PAGE 104 OF THE SECOND EDITION OF THE CYBERNETIC SERENDIPITY CATALOGUE (1969), MOTIF EDITIONS OFFERED FOR SALE SEVEN LITHOGRAPHS OF IMAGES FROM THE EXHIBITION. THE SCHOOL OF CYBERNETICS FOUND SIX OF THESE OFFERED FOR SALE THROUGH A SECONDHAND ART DEALER IN THE UK, AND PURCHASED THEM IN 2022.

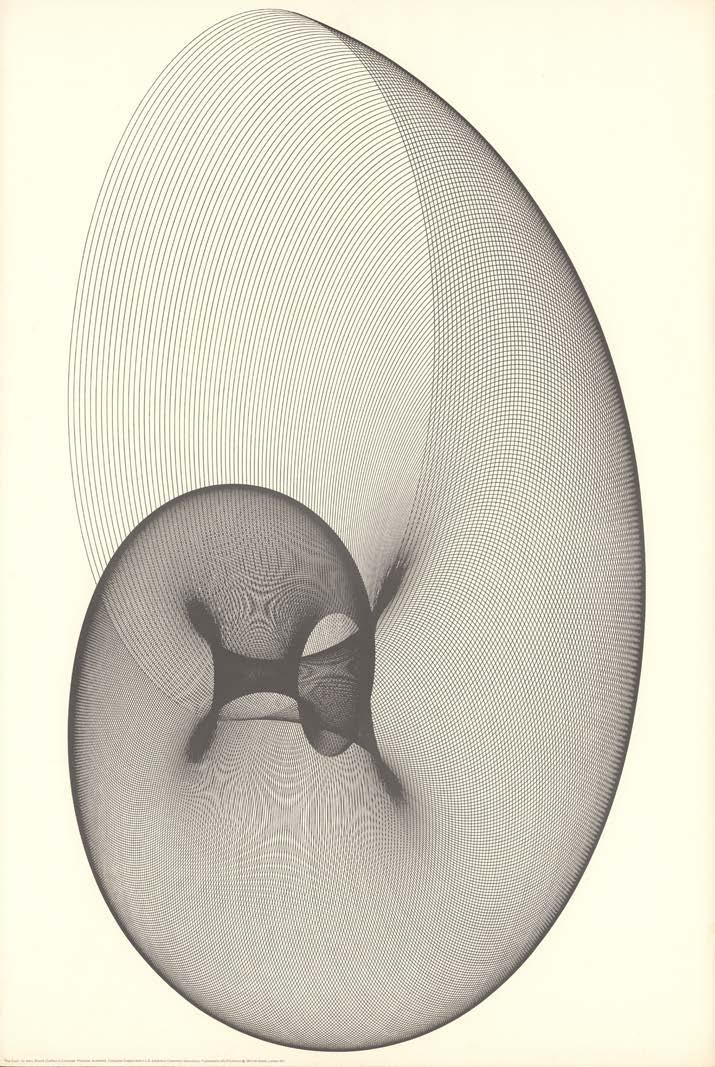

1968

The Snail was one of seven computer graphics presented at Cybernetic Serendipity by the computer hardware company California Computer Products, Inc (later CalComp Technologies, Inc). CalComp aimed to demonstrate the capability of their plotting system through the exhibition.

CalComp’s plotters were some of the first computer graphics output devices ever sold; they allowed line drawings to be made entirely under computer control. Further, they were perhaps the first non-IBM peripheral that could be used with an IBM machine. The piece was created by Kerry Strand, an engineer and physicist who worked for CalComp. It was generated on a Calcomp 770 tape system, drawn on a Calcomp 702 flatbed plotter, with a printing time of 4.5 hours.

CalComp was merged into Lockheed’s Information Systems Group in the 1980s.

ON PAGE 104 OF THE SECOND EDITION OF THE CYBERNETIC SERENDIPITY CATALOGUE (1969), MOTIF EDITIONS OFFERED FOR SALE SEVEN LITHOGRAPHS OF IMAGES FROM THE EXHIBITION. THE SCHOOL OF CYBERNETICS FOUND SIX OF THESE OFFERED FOR SALE THROUGH A SECONDHAND ART DEALER IN THE UK, AND PURCHASED THEM IN 2022.

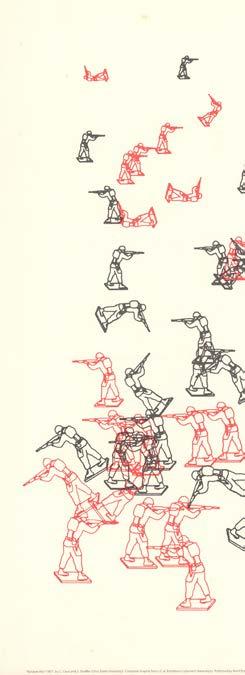

CHARLES CSURI, JAMES SHAFFER / OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY

1967

Charles Csuri’s image of American toy soldiers is a detail from a larger artwork that also included a list of soldiers’ names. A pseudorandom number generator determined the distribution and position of the soldiers shown on the battlefield. The program also arbitrarily decided who would be killed, wounded, missing or commended in battle.

Csuri made the original work in 1967, when anti-Vietnam war sentiment was at its height.

ON PAGE 104 OF THE SECOND EDITION OF THE CYBERNETIC SERENDIPITY CATALOGUE (1969), MOTIF EDITIONS OFFERED FOR SALE SEVEN LITHOGRAPHS OF IMAGES FROM THE EXHIBITION. THE SCHOOL OF CYBERNETICS FOUND SIX OF THESE OFFERED FOR SALE THROUGH A SECONDHAND ART DEALER IN THE UK, AND PURCHASED THEM IN 2022.

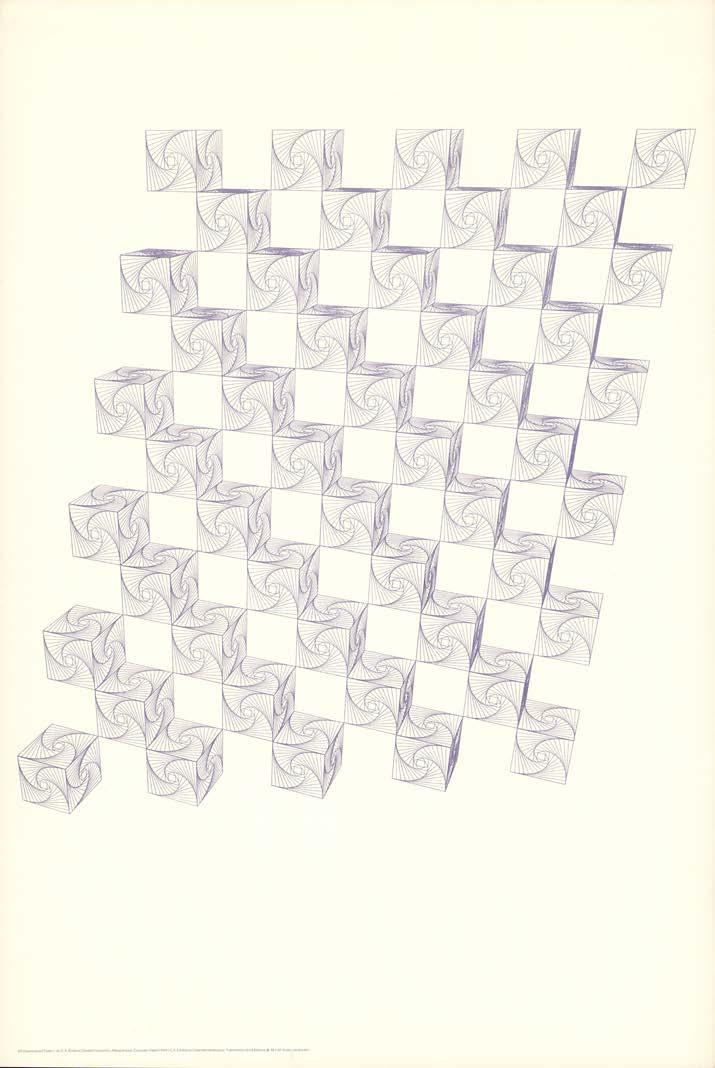

DONALD K. ROBBINS / SANDIA CORPORATION

1968

This piece is an early 3D computer design based on a mathematical challenge known as the ‘four-bug problem’ with the use of cubes and perspective, Robbins added a three-dimensional element. At the time, he was employed at the Sandia Corporation, a subsidiary of Lockheed Martin (now Sandia National Laboratories, a subsidiary of Honeywell International), which was heavily involved in the development of nuclear weapon systems during and after World War Two.

Early computer art was sometimes criticised for its reliance on mainframe computer systems that were generally only available to the military and research institutions.

ON PAGE 104 OF THE SECOND EDITION OF THE CYBERNETIC SERENDIPITY CATALOGUE (1969), MOTIF EDITIONS OFFERED FOR SALE SEVEN LITHOGRAPHS OF IMAGES FROM THE EXHIBITION. THE SCHOOL OF CYBERNETICS FOUND SIX OF THESE OFFERED FOR SALE THROUGH A SECONDHAND ART DEALER IN THE UK, AND PURCHASED THEM IN 2022.

WILLIAM FETTER

1966

This computer-drawn, animated figure was developed by William Fetter, who coined the term “Computer Graphics” to describe his experiments with computeraided image production, particularly in rearticulating perspective. The term attempted to draw a distinction between such ‘technical’ work and computer art.

The figure was designed to meet US Air Force anthropometric data – the median size of a pilot. It was composed of seven connected systems so that the figure could be put through numerous positions, from rest to ‘extreme’ postures.

Its significance as the first computer graphic figure was matched by its dynamic quality: it could animate ergonomics. Perspective drawing, the achievement of Renaissance art, was now reborn as environmental simulation mapping the human-machine nexus. Aircraft and their human pilot interfaces could be tested, as it were, before they were built, indeed before they were physically prototyped.

ON PAGE 104 OF THE SECOND EDITION OF THE CYBERNETIC SERENDIPITY CATALOGUE (1969), MOTIF EDITIONS OFFERED FOR SALE SEVEN LITHOGRAPHS OF IMAGES FROM THE EXHIBITION. THE SCHOOL OF CYBERNETICS FOUND SIX OF THESE OFFERED FOR SALE THROUGH A SECONDHAND ART DEALER IN THE UK, AND PURCHASED THEM IN 2022.

BBC 1968

Cybernetic Serendipity received widespread attention; it attracted visitors including Princess Margaret and Lord Snowdon, as well as The Doors (who held a press conference there), and it was also covered on public television. In this episode of BBC’s Late Night Line-Up, an innovative television discussion programme, curator Jasia Reichardt introduced the exhibition and the ideas behind it.

In the 1960s, broadcasting hours on British television were tightly controlled by the Postmaster General. The channel BBC Two was limited to seven hours of programming on a weekday (with several exemptions). The channel would normally only air for 30 minutes at 11am (Play School), leaving 6.5 hours for programs starting at 7pm. Late Night Line-Up, scheduled as the last show before closedown, could therefore theoretically remain on the air until 1:30am. It never happened, but it did nevertheless provide a unique and vibrant space for free-flowing discussion that was unrestricted by time limits.

WE ARE GRATEFUL TO JASIA REICHARDT FOR HER PERMISSION TO SHOW THIS SEGMENT; WE WERE UNABLE TO SOURCE THE ORIGINAL. THANKS ALSO TO QUESTACON AND CANDICE ADDICOTE FROM THE GREEN SHED, CANBERRA, FOR HELPING US TO ARRANGE A LOAN OF THEIR NEW/OLD TELEVISION SET.

1968

It did not take long for conversations about Cybernetic Serendipity to make their way to Australia. Two days after the conclusion of the exhibition at the ICA, The Sydney Morning Herald featured this review of the exhibition. The review titled Their Sense of Humour, was contextualised with an explanation on what computers are and what they can do.

The article feels remarkably contemporary; it raises many of the same hopes and fears about new and emerging systems that we continue to discuss today.

WE ARE GRATEFUL FOR TROVE, AN INVALUABLE RESOURCE FROM THE NATIONAL LIBRARY OF AUSTRALIA, WHERE WE WERE ABLE TO FIND SOME OF THE EARLIEST MENTIONS OF CYBERNETIC SERENDIPITY IN AUSTRALIA.

WE WISH TO THANK DOUG RICHARDSON FOR PRESERVING THIS ORIGINAL PROGRAM AND SHARING IT WITH US.

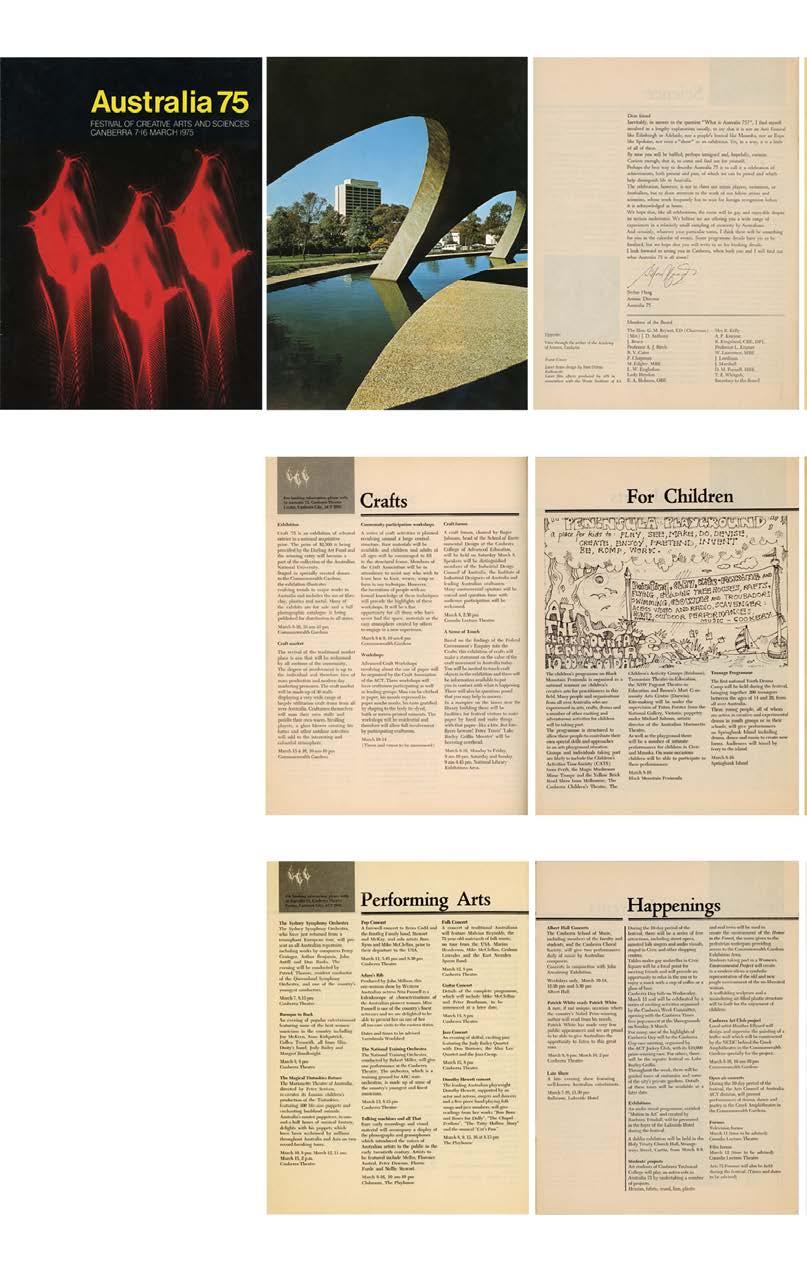

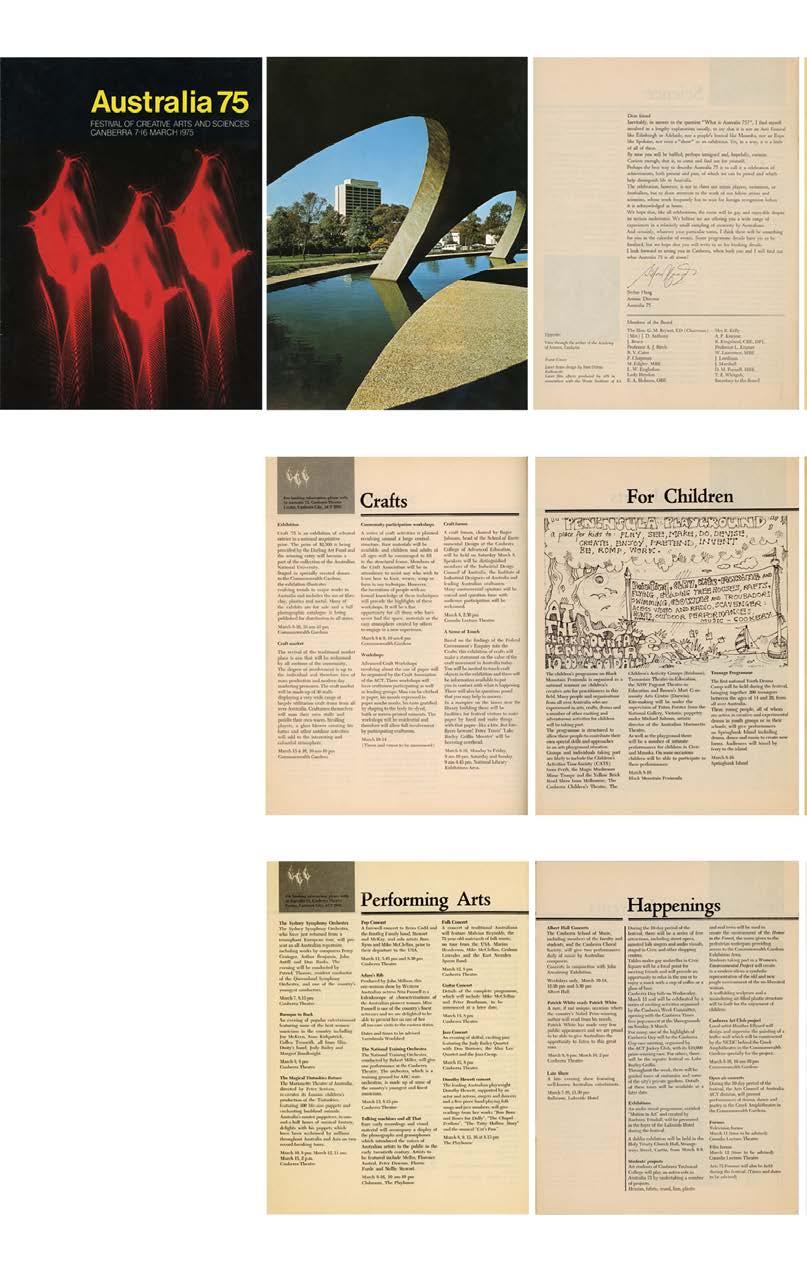

“By now you will be baffled, perhaps intrigued and, hopefully, curious. Curious enough, that is, to come and find out for yourself. Perhaps the best way to describe Australia ‘75 is to call it a celebration of achievements, both present and past, of which we can be proud and which help distinguish life in Australia.”

Stefan Haag Artistic Director, Australia ’75 In the Australia

‘75 program

“By now you will be baffled, perhaps intrigued and, hopefully, curious. Curious enough, that is, to come and find out for yourself. Perhaps the best way to describe Australia ‘75 is to call it a celebration of achievements, both present and past, of which we can be proud and which help distinguish life in Australia.”

WE WISH TO THANK DOUG RICHARDSON FOR PRESERVING THIS ORIGINAL PROGRAM AND SHARING IT WITH US.

Stefan Haag Artistic Director, Australia ’75 In the Australia ‘75 program

Cybernetic Serendipity has a life beyond that moment in London in 1968. Through individuals who travelled to experience the exhibition and took stories back home to places across the globe, the exhibition collided with other movements seeking to shape futures of and with computer-enabled systems.

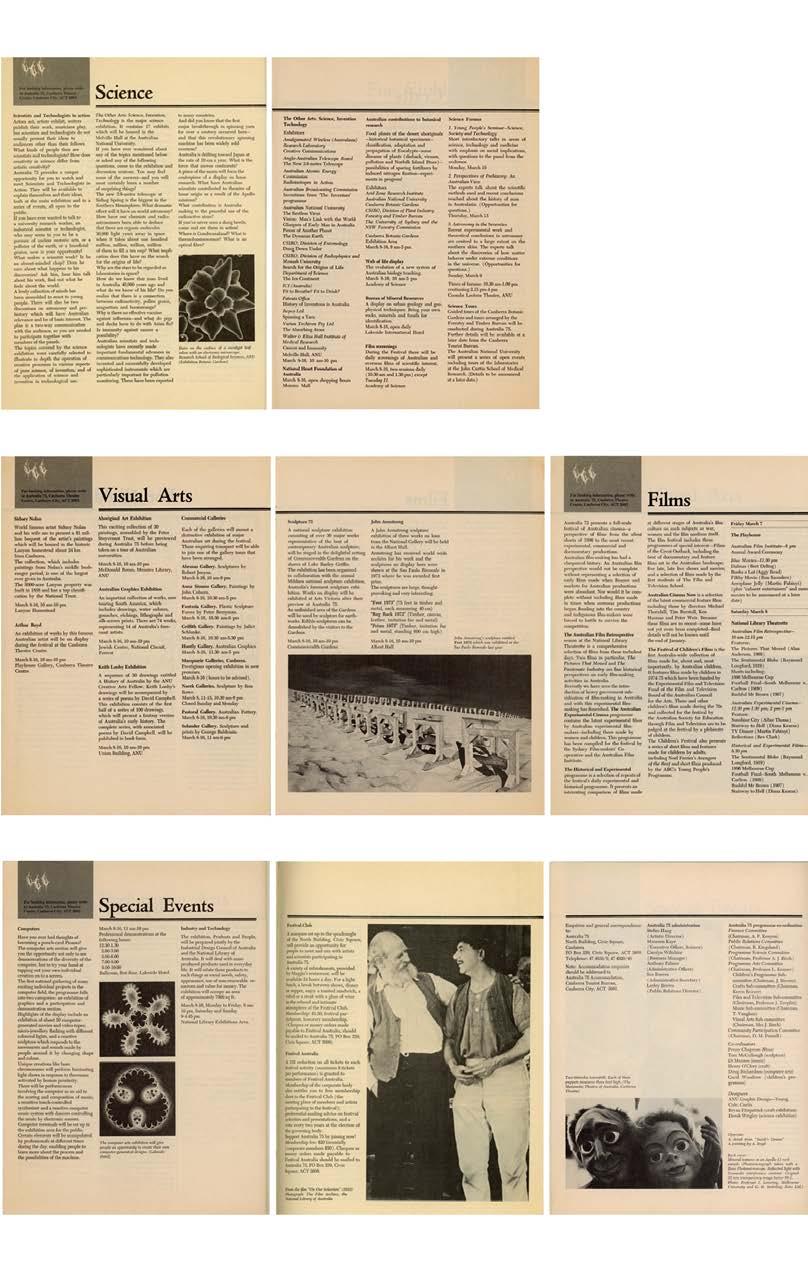

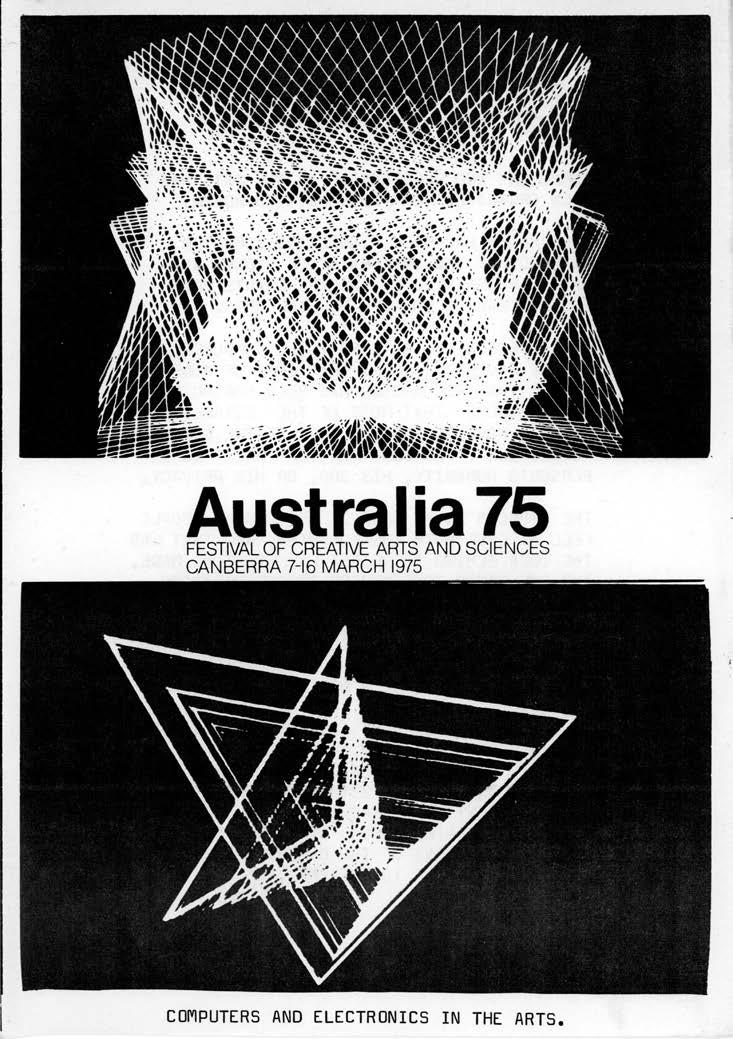

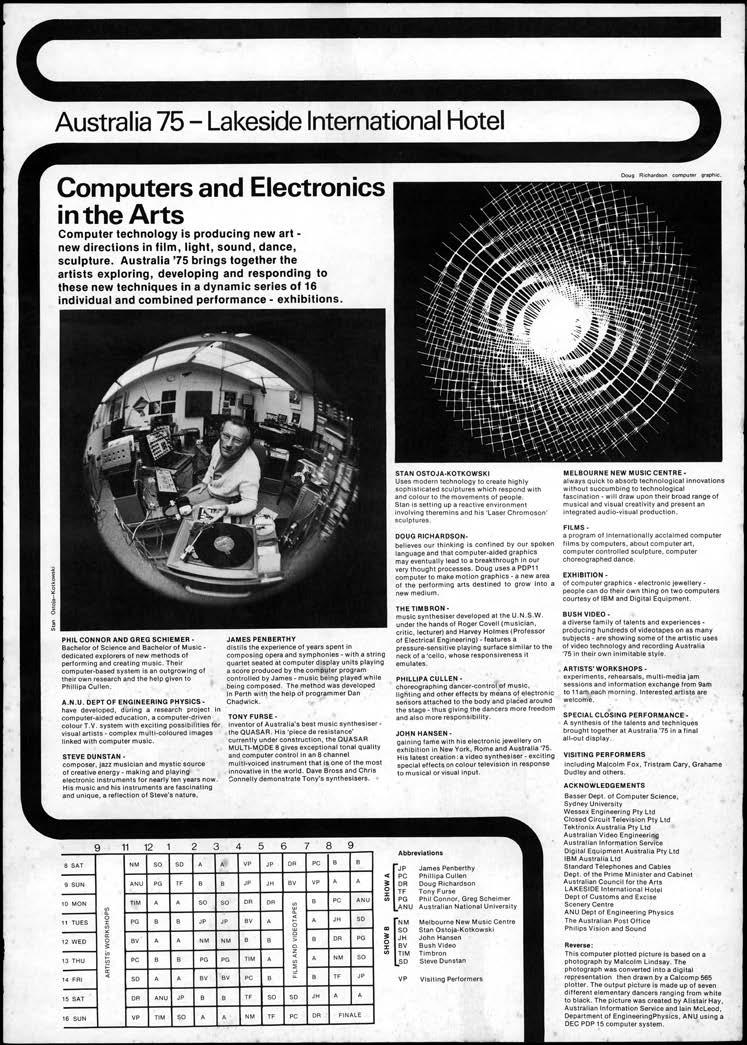

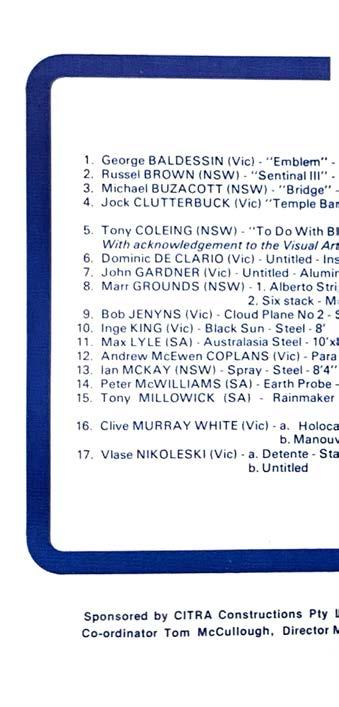

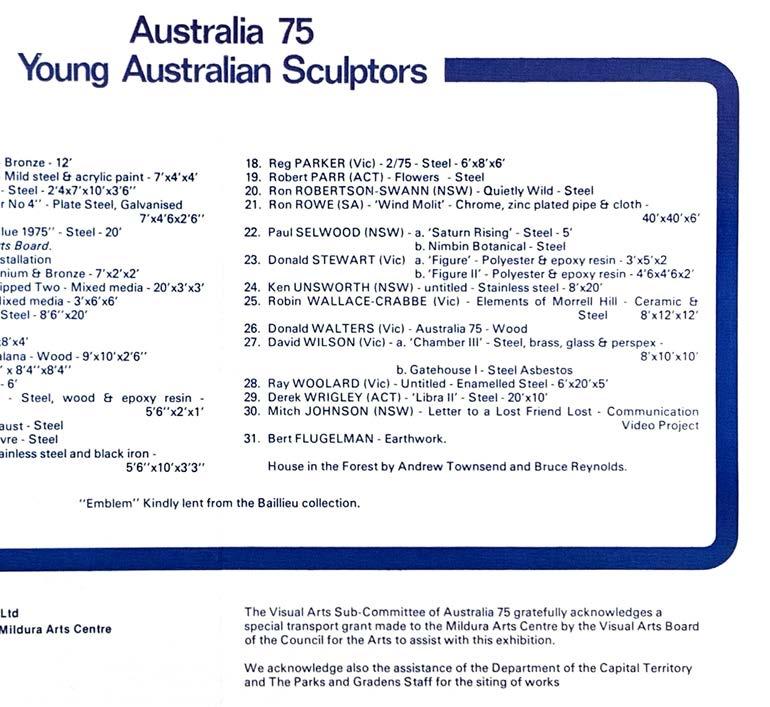

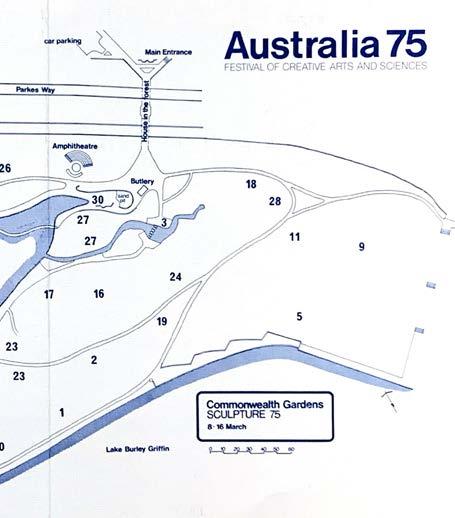

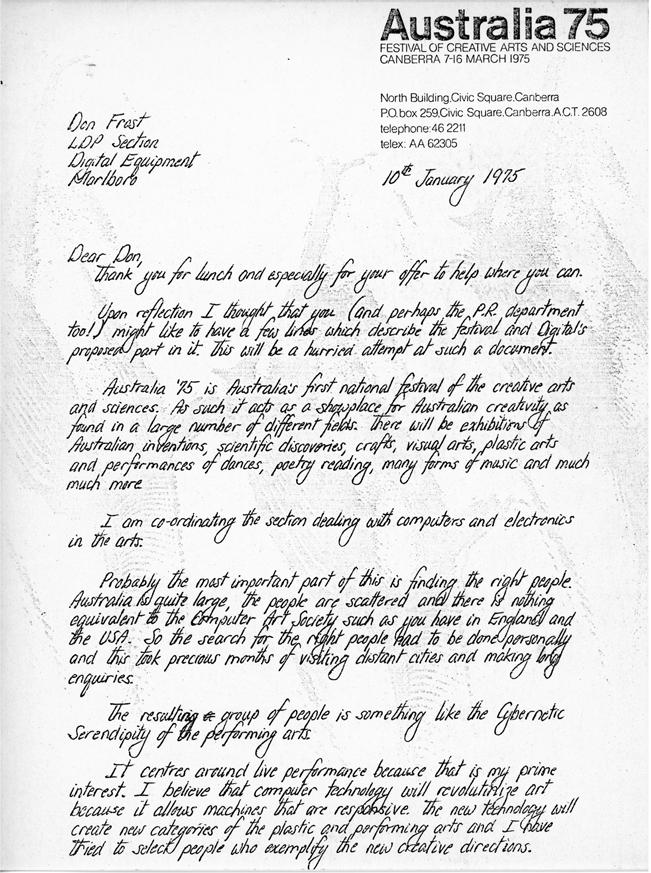

In 1975, Cybernetic Serendipity was invoked in an Australian exhibition called Computers and Electronics in the Arts, which was one of many exhibitions that formed a part of the Australia ’75 Festival of the Creative Arts and Sciences. Another point through time represented in the works around you here.

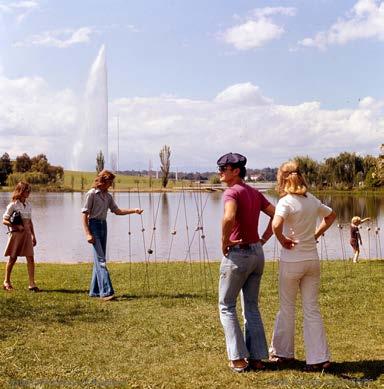

In March 1975, Canberra came alive with the ten-day Australia ’75 event, described by Artistic Director Stefan Haag as a celebration of the achievements of Australia’s scientists and artists, and their contributions to shaping Australia’s national identity. The festival included works from the

theoretical and applied sciences, crafts, visual arts, performing arts, music, sculpture, Indigenous art, films, and a children’s program. It was opened by Prime Minister Gough Whitlam in the ballroom of the Lakeside International Hotel (now the QT Hotel), which was also the venue for Computers and Electronics in the Arts.

This was a time of optimism in Australia. It coincided with the Vietnam War ending and the arrival of colour television. Australia ‘75 occurred during a period of widespread revision of Australian culture. Gough Whitlam was rapidly reforming policy and was at the precipice of his sudden Dismissal. Australia’s national cultural institutions were still emerging. While the National Gallery had been announced in 1968, work on the building would not be complete until 1982. Jackson Pollock’s Blue Poles was still being sheltered in a Fyshwick warehouse.

And a national conversation was raging around Australian identity, focusing not only on ‘Who are we?’ but ‘What can we build? What can we become?’

Haag asserted that Australian identity could be distinguished through a celebration of the connections between art and science.

In this context, Australia’s first electronic arts exhibition, Computers and Electronics in the Arts, took place. It was organised by Douglas Richardson, inspired by Cybernetic Serendipity, and held months before the public release of the first ever personal computer. The intent of the organisers was to shape the public’s imagination about the exciting possibilities and potentials of new and emerging computational technologies.

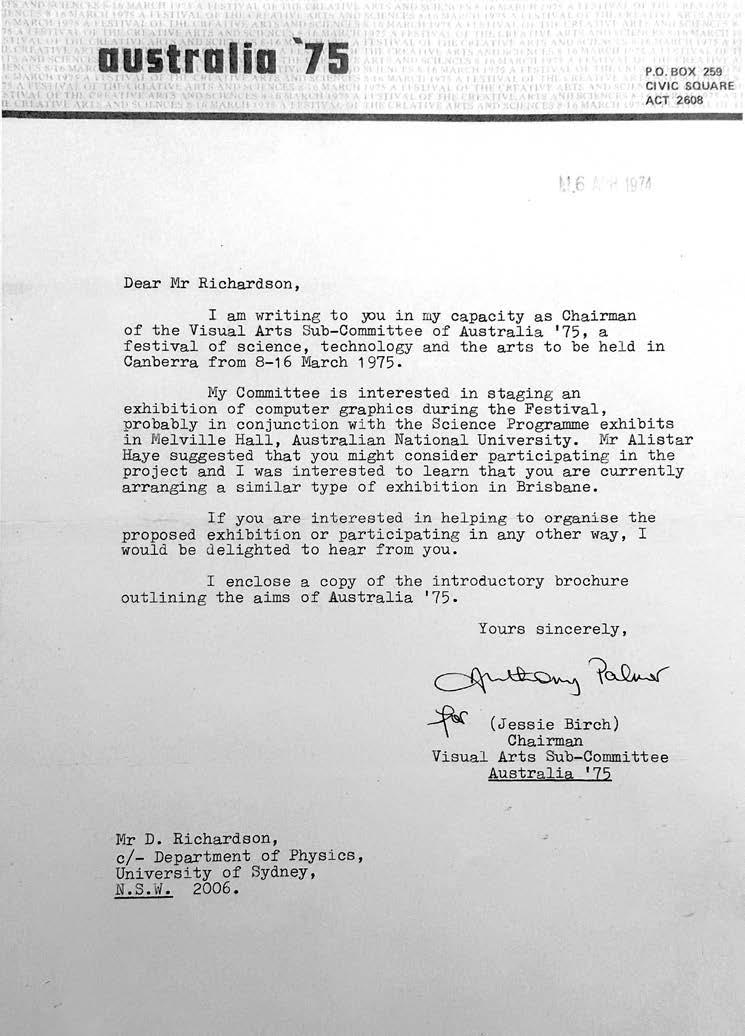

Doug Richardson, who was working as John Bennett’s research assistant at the University of Sydney's Basser Computing Department, was approached by Jessie Birch to curate the exhibition.

The program brought together a community of engineers, artists and more who shared a similar motivation to the creators of Cybernetic Serendipity: to showcase creative technologies, to collaborate on new experimental works, and to invite a broader conversation about the future. Doug Richardson sought to reengage the public with the potentials of emerging technology, responding to scepticism and fear about the future of computing that had taken hold in the public’s perception by 1975. Through their spontaneous collaborations with each other and the technologies that they built, the exhibitors asserted human creativity and agency alongside the growing societal use of computers. In doing so, they echoed the optimism of Cybernetic Serendipity and helped create the world we see around us today.

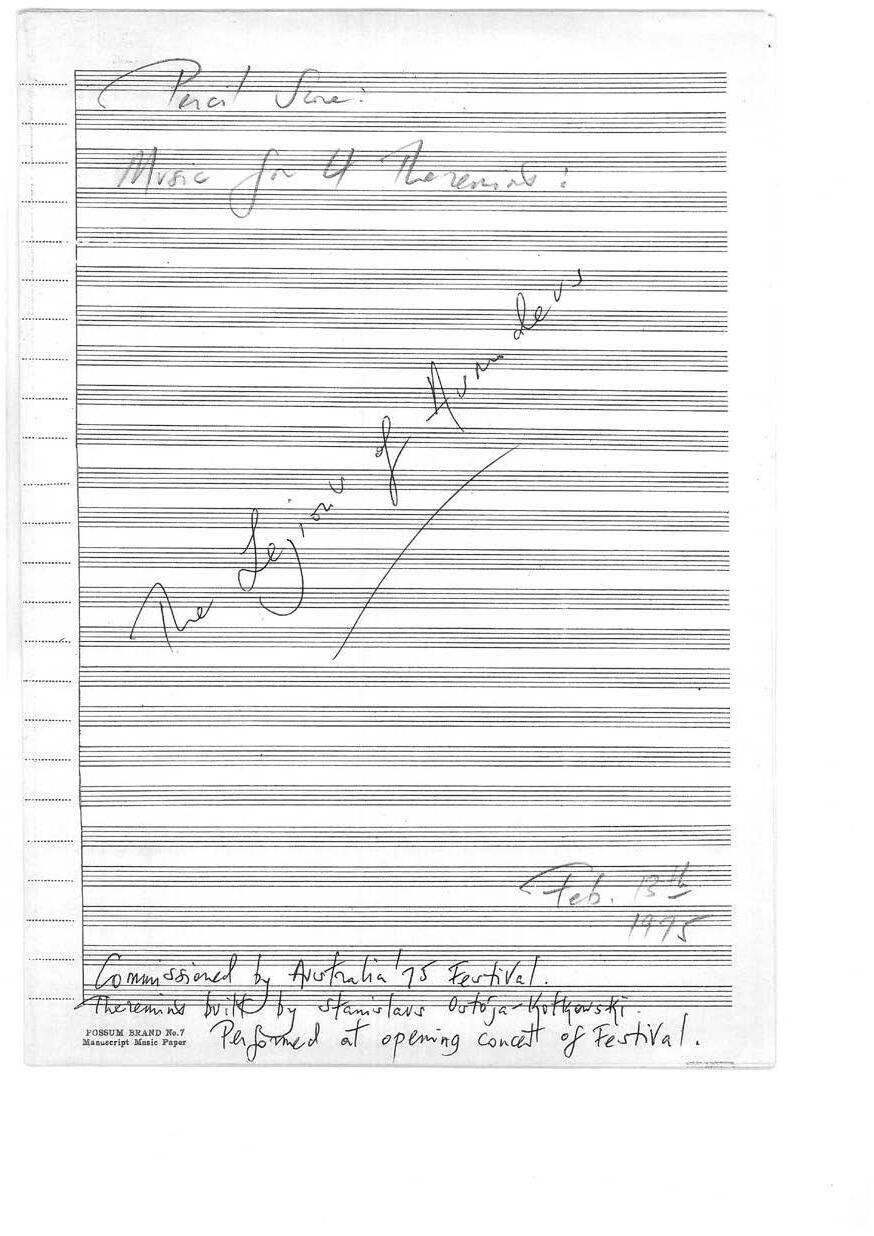

JOSEPH STANISAUS OSTOJA-KOTKOWSKI

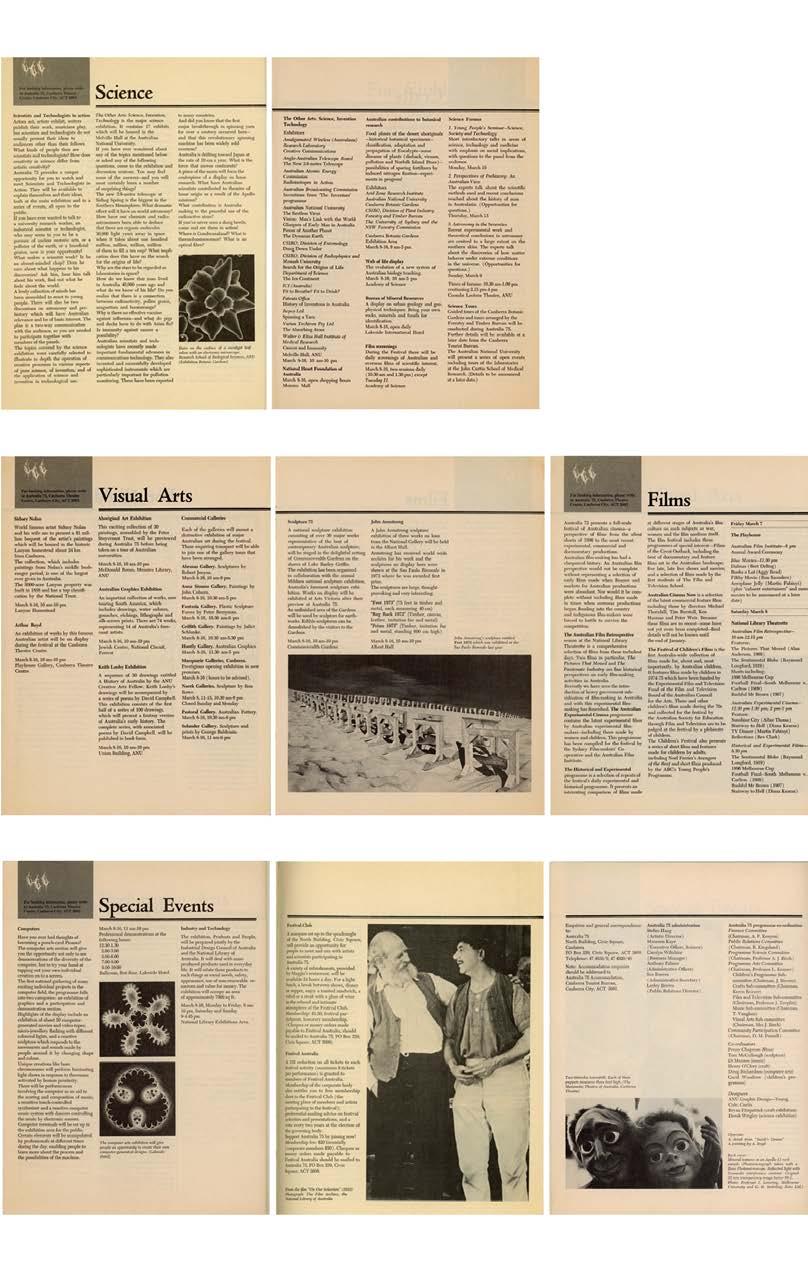

1975

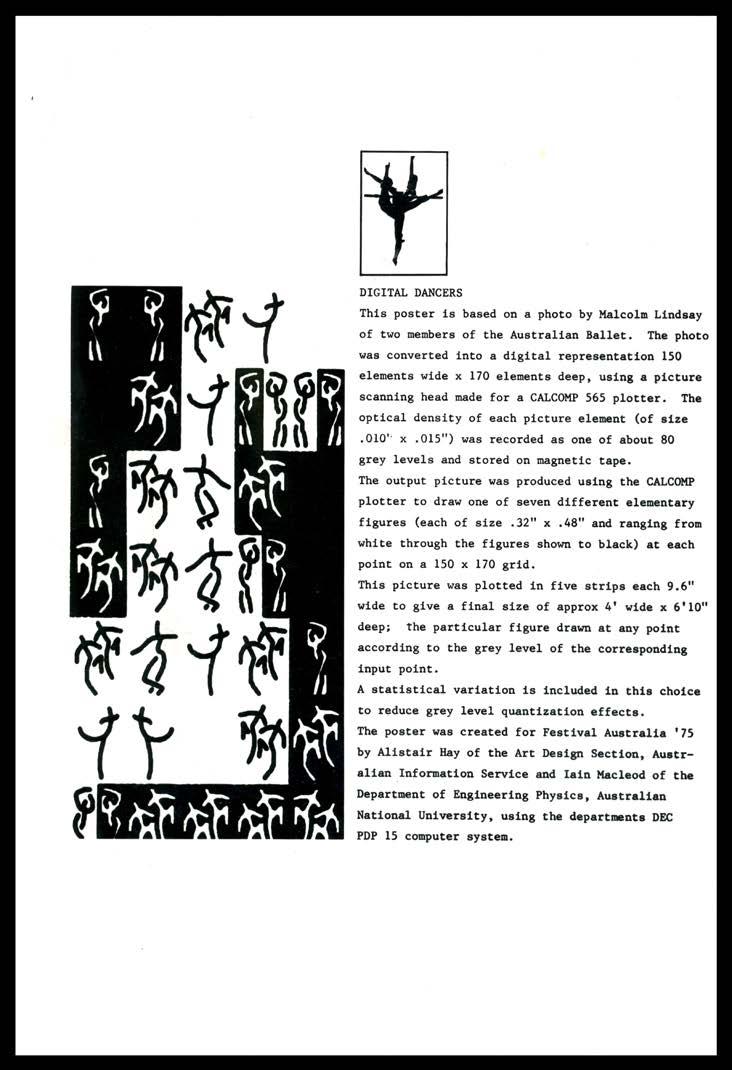

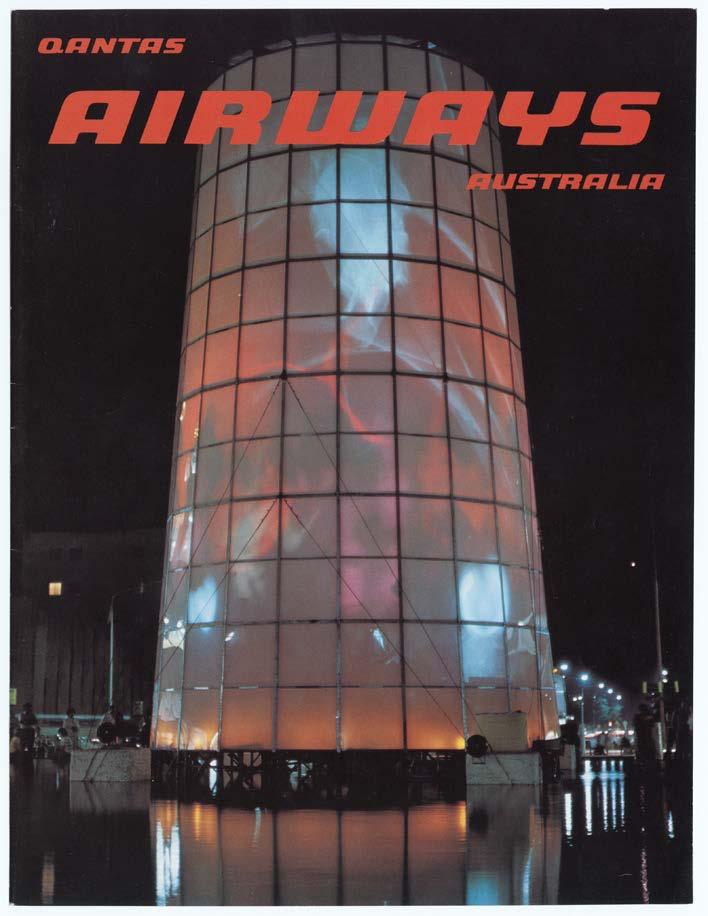

This poster promoted Australia ’75: Festival of Australian Creative Arts and Sciences, which took place in Canberra in March 1975. The original image, printed in triplicate, was created by shining a laser through a piece of broken glass; the uneven surface of the glass refracted the solid beam into the shapes on the poster. Lasers were not new at the time, but their use in poster design was unusual because artists’ access to lasers as with their access to computers was limited.

The creator of the poster, Poland-born Joseph Stanisaus (Stan) Ostoja-Kotkowski, had begun experimenting with lasers at the Australian Weapons Research Establishment (now the Defence Science and Technology Group (DSTG)). He was involved in the first theatre production in the world to use a laser beam (at the Adelaide Festival of Arts, 1968); one of his collaborators, Elizabeth Cameron Dalman, was founder of the Australian Dance Theatre.

EXPLORE ADVERTISEMENTS FROM THE TIME TO GET A GLIMPSE OF SOME OF THE TECHNOLOGIES WIDELY FAMILIAR TO THE PUBLIC AT THE TIME

THIS IS AN ORIGINAL POSTER ON LOAN FROM JOHN HANSEN, TO WHOM WE OWE OUR THANKS.

CRAFT '75, AN EXHIBITION WHICH FORMED PART OF THE AUSTRALIA '75 FESTIVAL, WAS HELD IN A BLUE GEODESIC DOME IN CANBERRA'S COMMONWEALTH GARDENS. IMAGE COURTESY OF THE NATIONAL ARCHIVES OF AUSTRALIA (NAA: A6135, K24/3/75/87).

1975

This video was recorded by what was then called Network 7, as a preview filmed a few days before the Australia ‘75 festival opened. They explain some of the many exhibitions that are part of Australia ‘75.

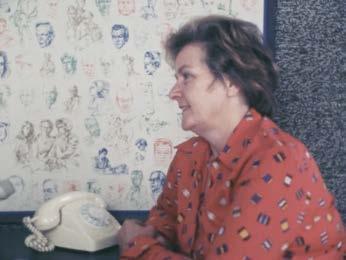

Two things are of particular note. First is an interview with Jessie Birch, the Deputy Chair of the Visual Arts Sub-committee which brought, among other things, Sidney Nolan’s Ned Kelly series to be exhibited at Lanyon Farm Homestead in southern Canberra. Second is an interview with Arthur Birch, Jessie’s husband, then Dean of Organic Chemistry at ANU and President of the Academy of Science, who was interviewed just outside of the Birch Building, now the home of the School of Cybernetics. He was a strong supporter of creativity and the arts in science and technology, and encouraged people to attend the exhibition The Other Arts: Science, Invention, Technology, on which he collaborated with Derek Wrigley.

THE SCHOOL OF CYBERNETICS ACQUIRED THIS FOOTAGE FROM THE NATIONAL FILM AND SOUND ARCHIVE. WE ARE ABLE TO SHOW IT HERE COURTESY OF SOUTHERN CROSS AUSTEREO.

PHOTOGRAPHER UNKNOWN

1975

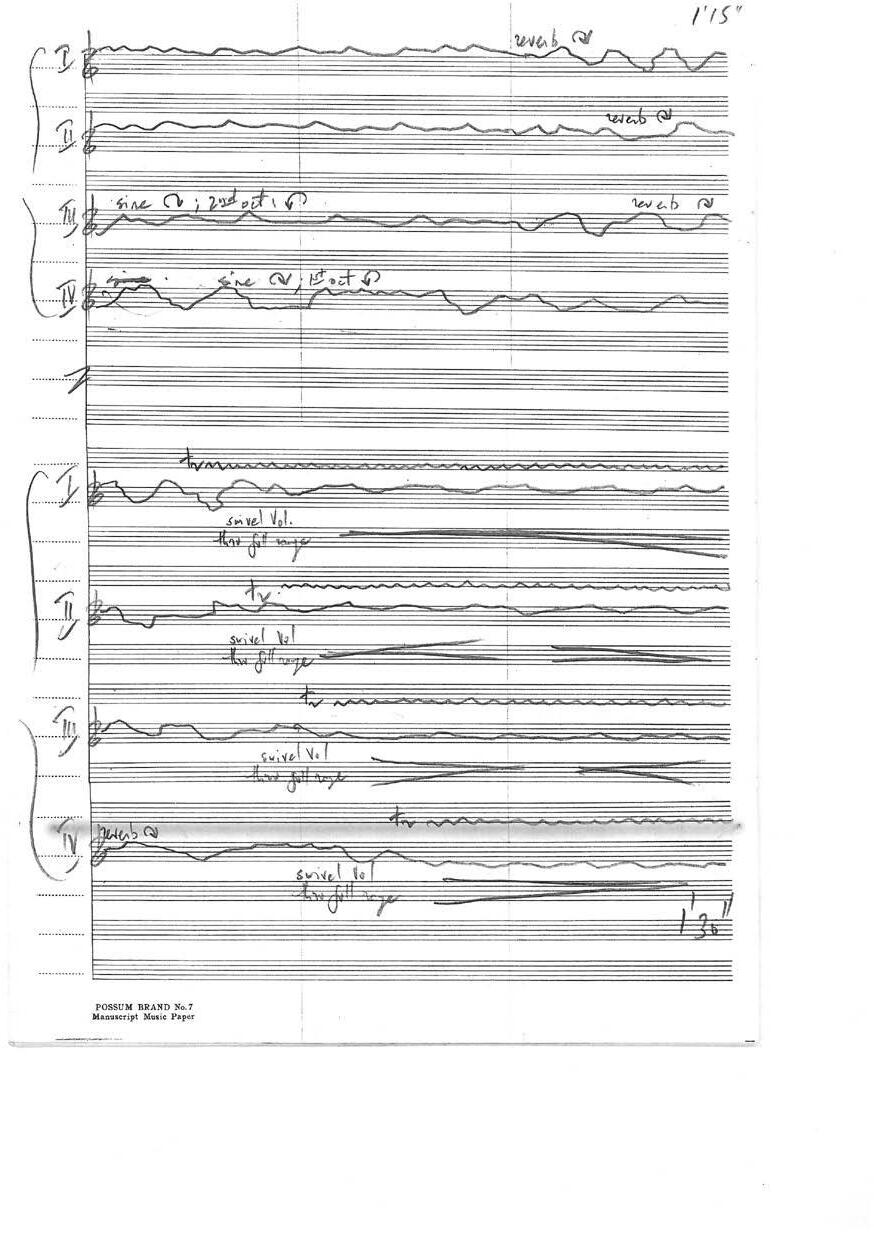

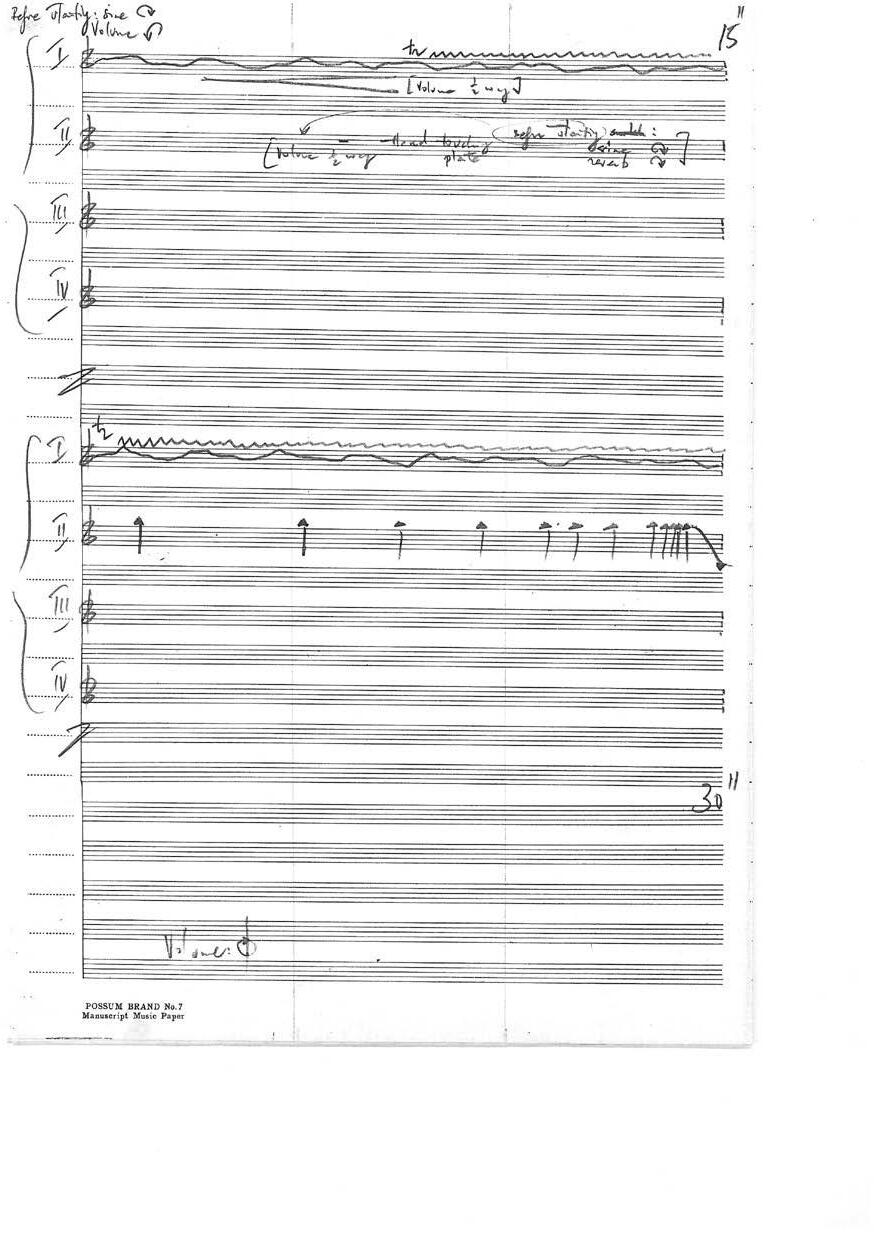

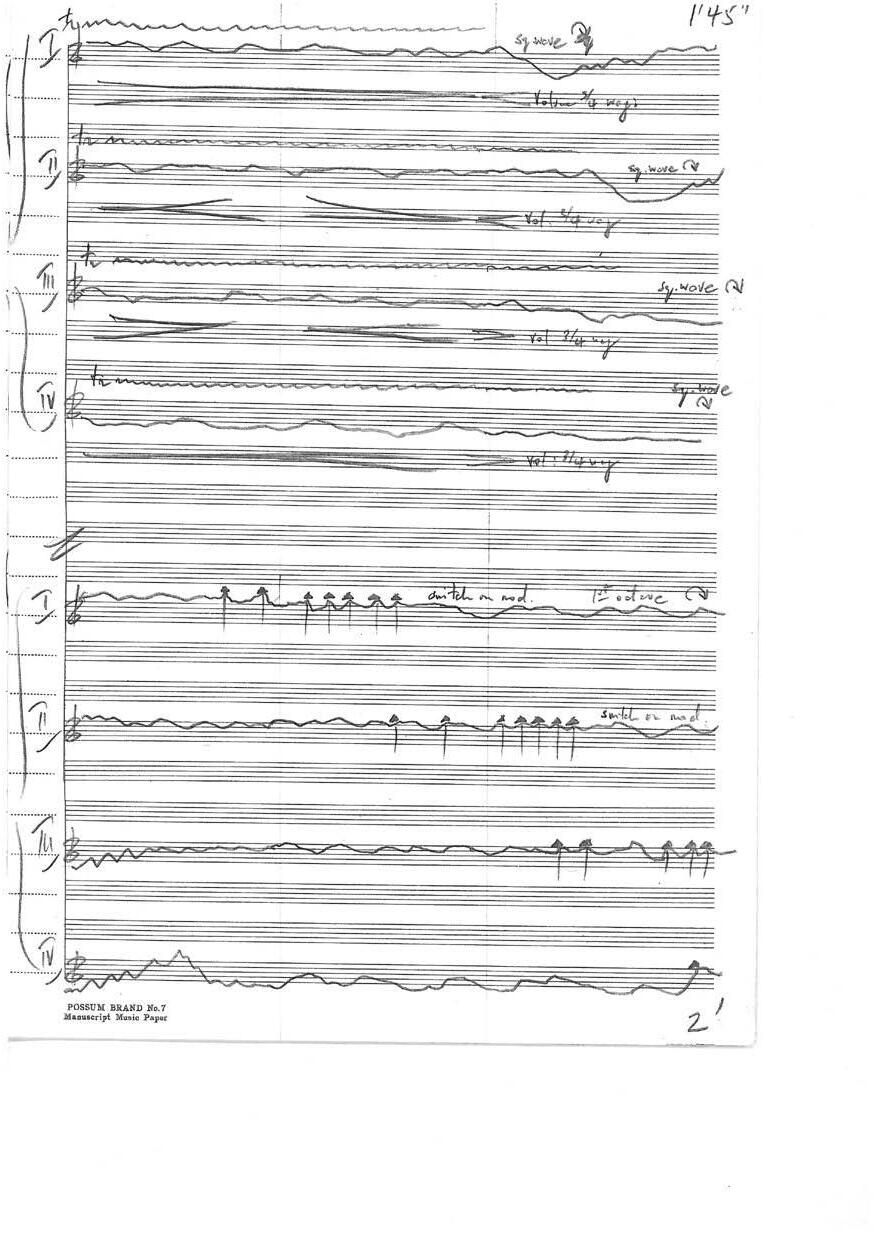

The opening ceremony took place in the ballroom of the Lakeside Hotel in Canberra (now the QT Hotel), pictured on the following pages. In 2021, Greg Schiemer recalled the evening’s events:

“The computer had crashed undetected, minutes before we went on stage, and it resulted in a theatrical spectacle I will not forget. We had already taken our places on each theremin platform antenna and had begun moving slowly and gracefully expecting to elicit a response from the system. But the computer had already stopped communicating with the synthesiser, causing notes to be stuck. The pitch of the notes gradually drifted upwards as filter capacitors in the synthesiser interface slowly discharged. It sounded like some previously unheard distress signal custom designed for emergency services. Phil Connor who was watching off stage noticed what had happened and tried rebooting

the computer. This woke the tele-typewriter terminal which added to the spectacle with a noisy mechanical racket consisting of carriage returns, feeding paper, ringing the bell and vibrating madly like an overloaded washing machine. All this happened under stage lights in full view of the audience in the ballroom of the Lakeside Hotelwith the Prime Minister Gough Whitlam and his wife Margaret towering some 30 centimetres over the heads of the other 800+ guests. The Merce Cunningham Dance Company had nothing on this... John Cage would have loved it.”

WE ARE GRATEFUL TO THE STATE LIBRARY OF SOUTH AUSTRALIA FOR FACILITATING OUR ACCESS TO THIS PHOTOGRAPH (PRG: 919/44/77), TO STAN FOR DONATING HIS COLLECTION TO THE LIBRARY, AND TO GREG SCHIEMER FOR HIS PERMISSION TO USE THIS QUOTE HE PROVIDED TO EVELYN JUERS IN HER BIOGRAPHY THE DANCER ABOUT PHILIPPA CULLEN.

IMMERSE YOURSELF IN MORE IMAGES FROM THE OSTOJA-KOTKOWSKI COLLECTION, ONLINE AT THE STATE LIBRARY OF SOUTH AUSTRALIA

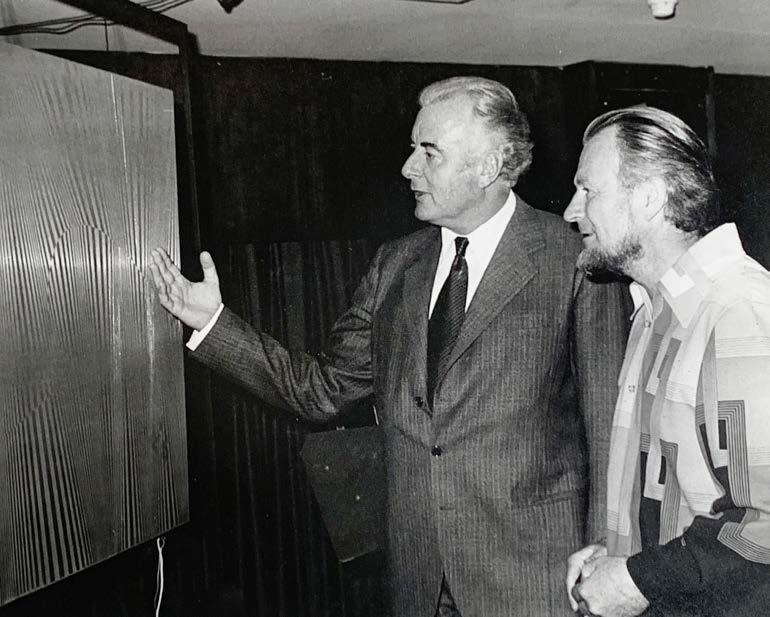

PRIME MINISTER GOUGH WHITLAM 1975

Australian Prime Minister Gough Whitlam opened the Australia ‘75 Festival of the Arts and Sciences. The opening ceremony, pictured on the following pages, took place in the ballroom of the International Lakeside Hotel in Canberra (now the QT Hotel); this location also hosted the Australia ‘75 exhibition Computers and Electronics in the Arts, and some of the exhibited works were involved in the opening ceremony. Whitlam was accompanied by his wife Margaret, and the room was filled with over 800 guests. The Canberra Times wrote “A string of RAN matelots [Royal Australian Navy sailors], there to introduce proceedings with a specially commissioned fanfare stood incongruous in their starched old-fashioned blue and white among the screens, wires and dials of the computer era” (08 March 1975, p1).

In his opening speech, Whitlam discussed the importance of government support, through public funding independent of government authority, for art and scientific endeavour. Just two days prior to the speech where this photo was taken, he had introduced legislation to establish the Australian National Gallery in Canberra; at the time of the speech he also had legislation before Parliament to establish the Australian Council for the Arts as an independent statutory authority.

It was at the same event that the Alpha-16 computer crashed with a mechanical crescendo moments before Philippa Cullen’s dance performance, creating an unintentionally dramatic opening event.

THE TRANSCRIPT OF THIS SPEECH IS IN THE PUBLIC DOMAIN, AVAILABLE THROUGH THE DEPARTMENT OF THE PRIME MINISTER AND CABINET’S PM TRANSCRIPTS COLLECTION.

READ A COMPLETE TRANSCRIPT OF WHITLAM’S SPEECH

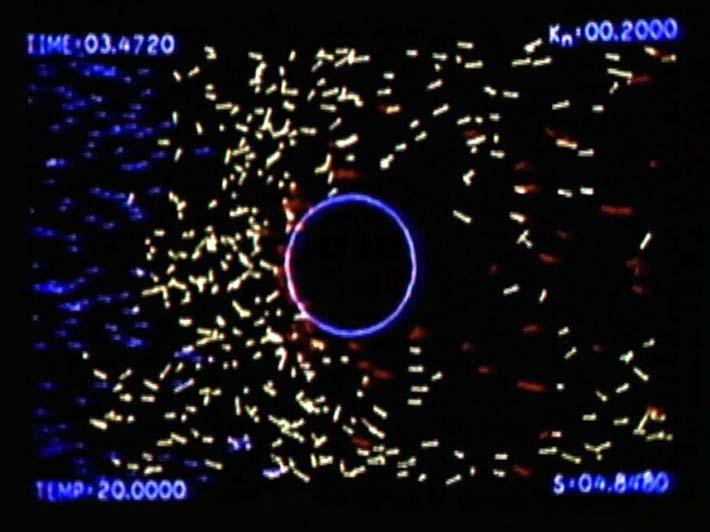

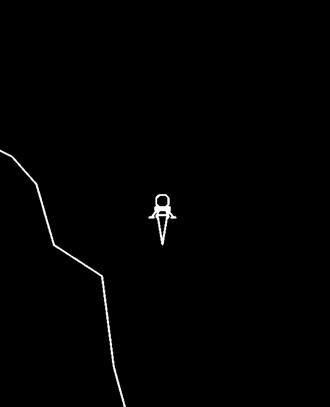

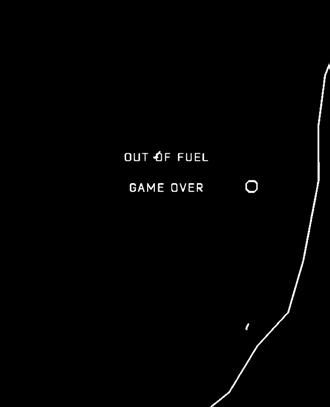

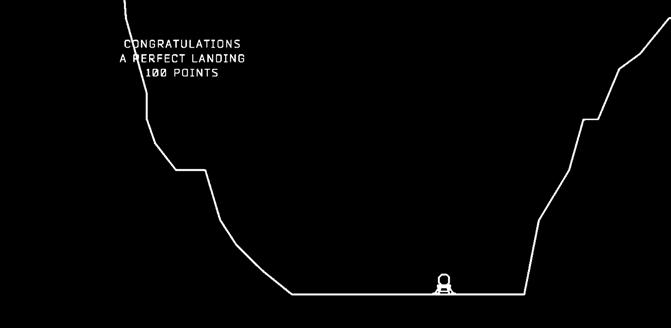

1969

DOUG RICHARDSON

Australia’s first computer animation was a simulation of a space shuttle re-entry to the Earth’s atmosphere. It was developed in a collaboration between Graeme Bird, then Lawrence Hargrave Professor of Aeronautical Engineering and Head of the Department at Sydney University, and Doug Richardson, who developed the audio-visual work. Their project was funded by NASA, which had contracted them to create simulations for the space shuttle re-entry. It took the pair two weeks to make 90 seconds of film.

The method developed by Graeme Bird, the Direct Molecular Simulation – Monte Carlo Method (DSMC), continues to be applied in aerospace research and development today.

WITH THANKS TO DOUG RICHARDSON FOR GENEROUSLY SHARING THIS WORK FOR THE EXHIBITION.

CHECK OUT THE COLOUR FILTER UNIT FOR COMPUTER GRAPHIC SYSTEM DEVELOPED BY BIRD AND RICHARDSON

SUE ROBINSON, DOUG RICHARDSON (ARTISTS), TOM COWAN, CHRIS TILLAM (FILMMAKERS)

1973

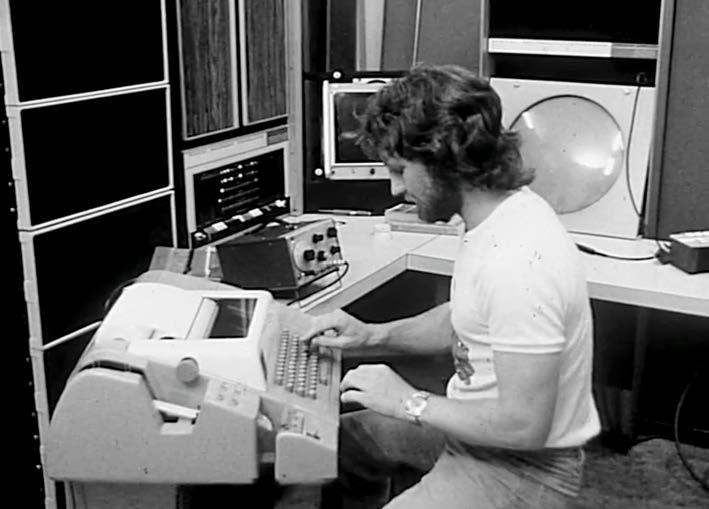

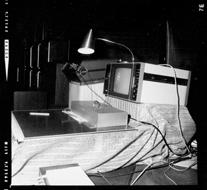

This is a film demonstrating a 3-D computer graphics system on a PDP-8 computer (one of the first minicomputers ever built) for which Doug Richardson developed the software.

The film opens to a distorted line -drawn 3-D word (possibly “D. Richardson”) which then mutates into the word “Transformations” which itself is squeezed, stretched and rotated, going through a range of transformations from the very close-up to the full word easily readable on the screen.

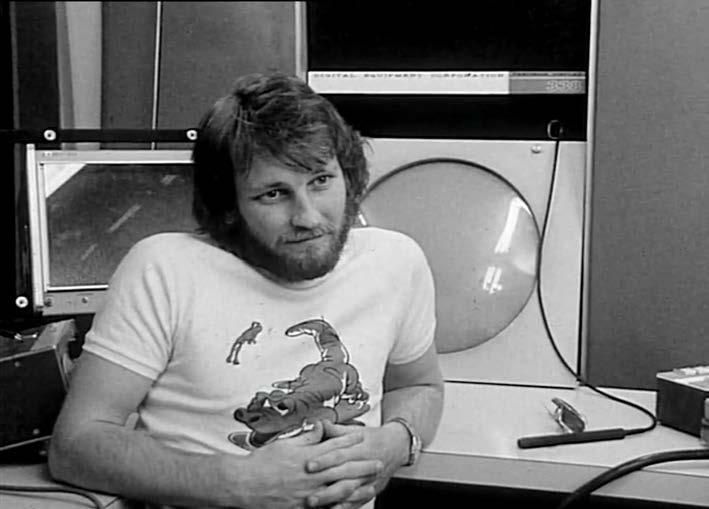

After the title we see a square cursor on the screen. A hand enters holding a light-pen and moves the cursor into a series of geometric lines. We then cut to an image of Doug Richardson sitting at the PDP-8 console in front of the large vector screen that was attached to the PDP-8.

There are four line-drawn images on the screen, each of which is a version of the same object seen from different angles. Richardson has a box of push-button switches which he uses with his left hand, selecting different functions for the drawing generation function.

He works on each segment, adding lines to particular parts of it as the other segments slowly rotate through 3-D views, finally showing us a single completed rotating image on the screen. We then cut to a larger copy of the image on the screen surface going through a series of transforms of a more or less trapezoidal form.

Black, then a close up of a woman’s face and eye looking at the screen. The shot cuts to an image of the computer screen again with four segments of a rectangular drawing on it.

This shot then cuts to a shot from her side as she draws on the screen with the light pen, pressing buttons on the control box to bring different processes to bear. She has drawn a line that extends side-toside and abruptly changes into a series of squares, one inside the other in a 3-D tunnel that moves across, down, in and out of the depth of the screen as she controls its movement with slider controls on the control box.

We then see her reflected in the screen as she works on the drawing segments.

Fade to black and then fade up to see the full image that she has created, which she manipulates through a long sequence using the controls in the control panel.

The film then cuts to the title “Transformations” again. And finally the credits, also drawn on the computer screen, which close with the title transforming itself across the screen.

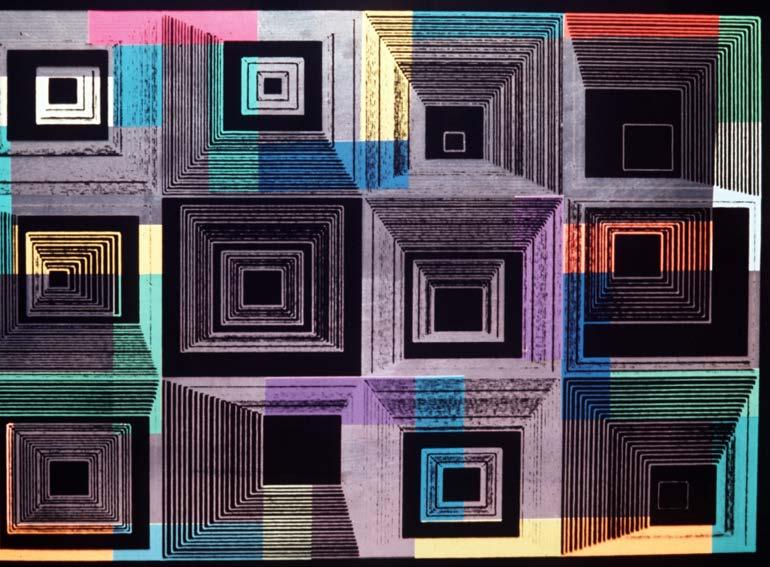

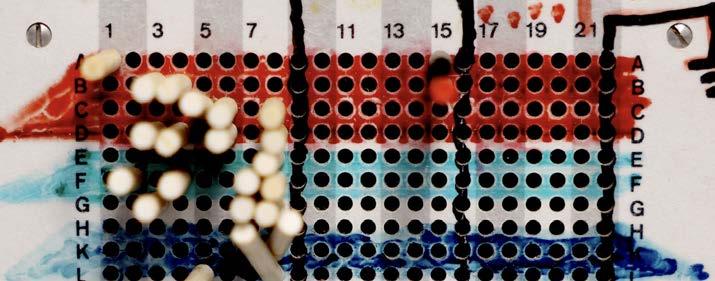

DOUG RICHARDSON, FRANK EDLITZ

This is one of the pictures exhibited by Doug Richardson and Frank Edlitz at the Hogarth Galleries, Sydney, in June 1975. They created the image on Richardson’s PDP-8 system, photographed it to high-contrast film, and coloured it by laying coloured papers under the film when mounting the image.

Eidlitz, a commercial artist and graphic designer who emigrated to Australia from Hungary in 1948, saw his role as a designer as to collaborate with scientists to facilitate public understanding of what is happening with modern technology. He began collaborating with Richardson in the early 1970s, following a Churchill Fellowship that took him to MIT, where he first encountered early computers.

This work is an example of some of the earliest Australian computer graphics; it was produced before computers had screens, and in the same year that engineers from Xerox first demonstrated a graphical user interface. It was another decade before the wireframe image and 3-D graphics were more widely adopted by artists as the Commodore Amiga and Apple Macintosh arrived on the market. More information about the works can be found in Stephen Jones’s 2011 book Synthetics.

WE ARE GRATEFUL TO DOUG RICHARDSON AND THE ESTATE OF FRANK EIDLITZ FOR PERMISSION TO EXHIBIT THIS IMAGE.

CHECK OUT THE PDP-8

In Episode 581 of the popular music television series GTK (Get to Know), Doug Richardson was interviewed at Sydney University. The program aired on 30 October 1972, and Doug is described as a computer music experimenter.

GTK was produced and broadcast by ABC Television from 1969 to 1975. This precursor to MTV was created by Ric Birch for a youth audience underserved by commercial radio and television, and it filled a ten-minute programming gap that resulted from the ABC not running advertisements like commercial stations.

SEE ANOTHER GTK SEGMENT, ON BUSH VIDEO

WITH THANKS TO THE ABC FOR PERMISSION TO SHOW THIS CLIP.

JOHN BENNETT

1969-71

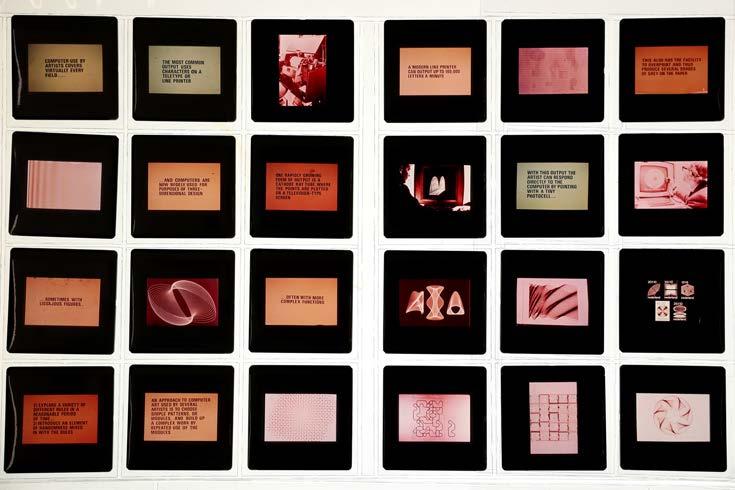

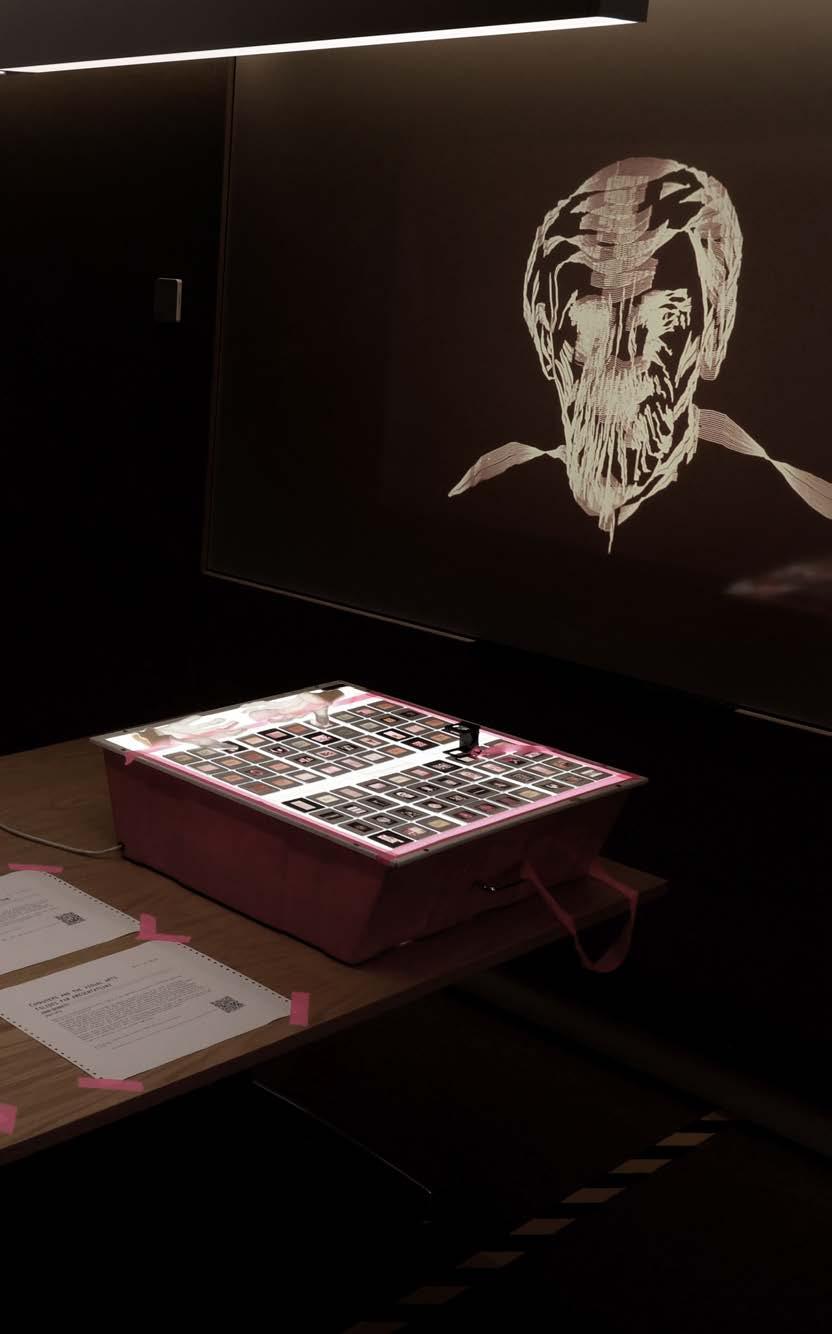

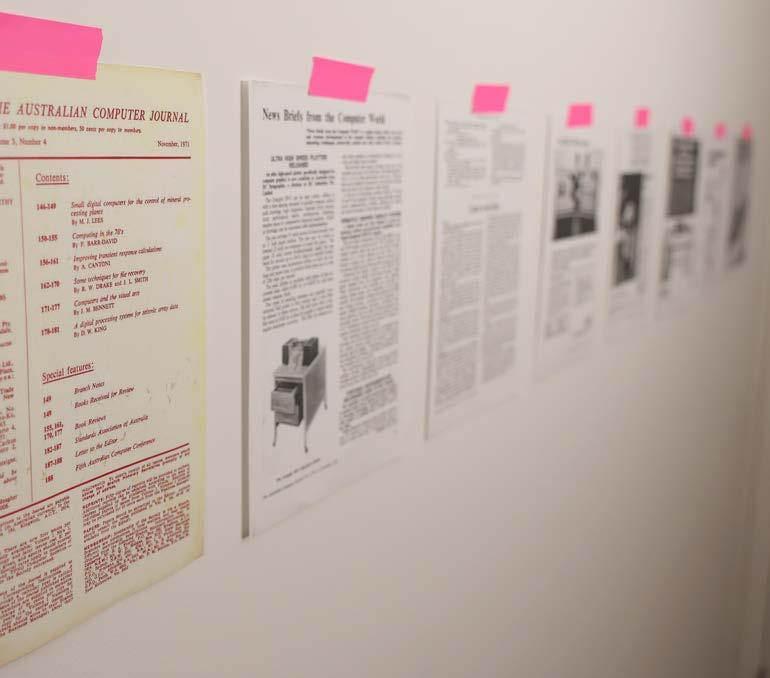

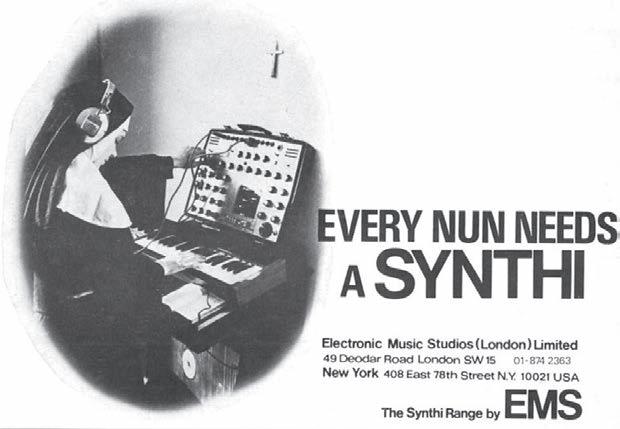

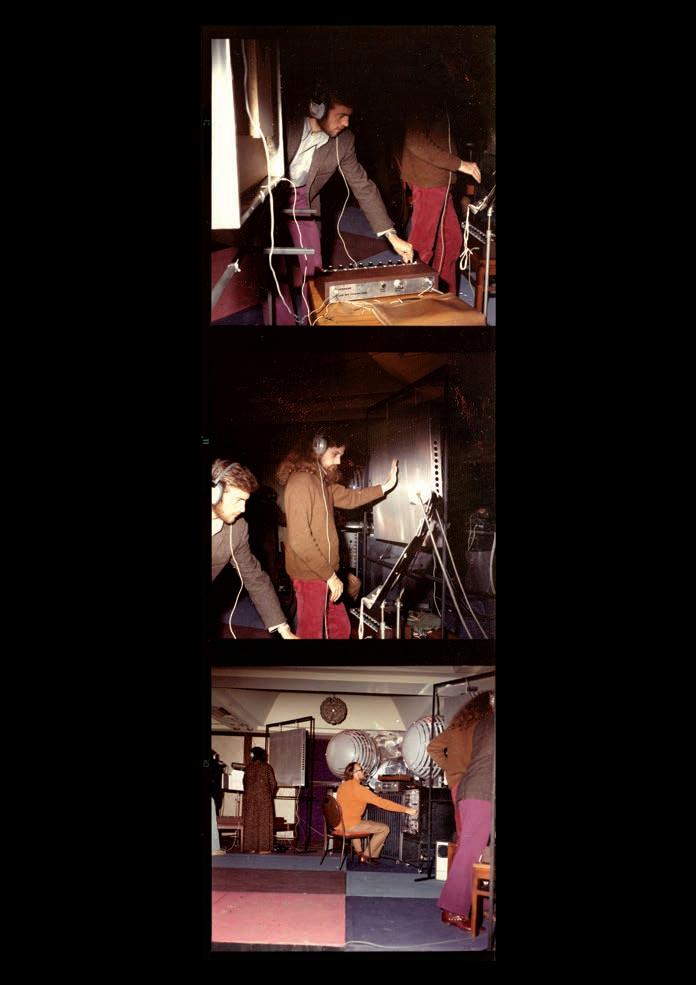

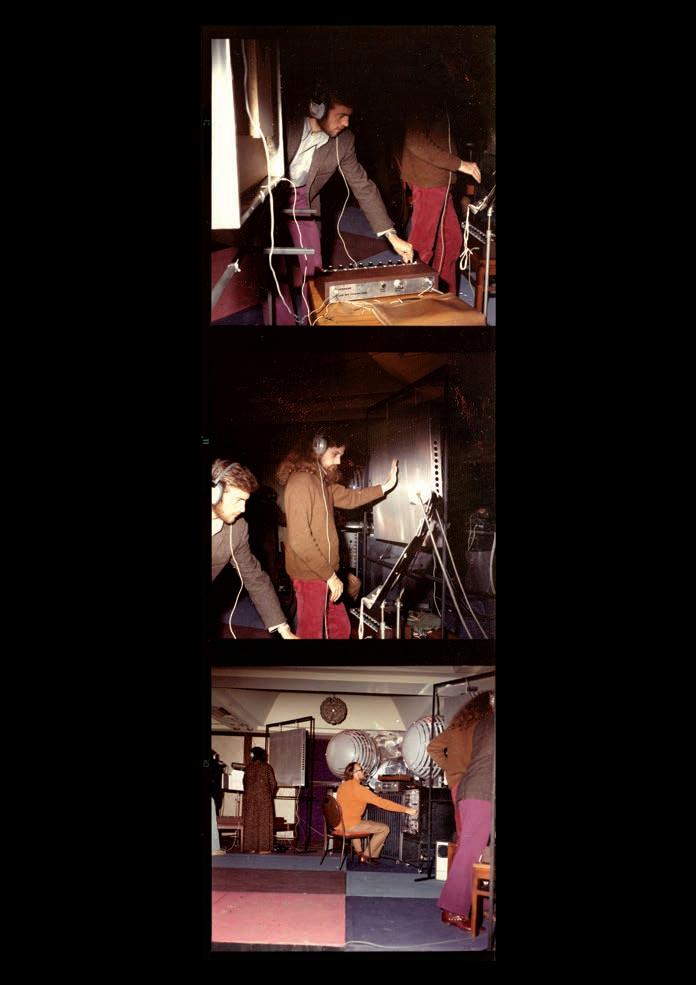

Behind this slide presentation sits a story of how Cybernetic Serendipity influenced computing and the arts in Australia.