From novice to knowledgeable

5 survival strategies for new district leaders

Addressing the downturn

Experts share their pro tips for responding to declining enrollment

From novice to knowledgeable

5 survival strategies for new district leaders

Experts share their pro tips for responding to declining enrollment

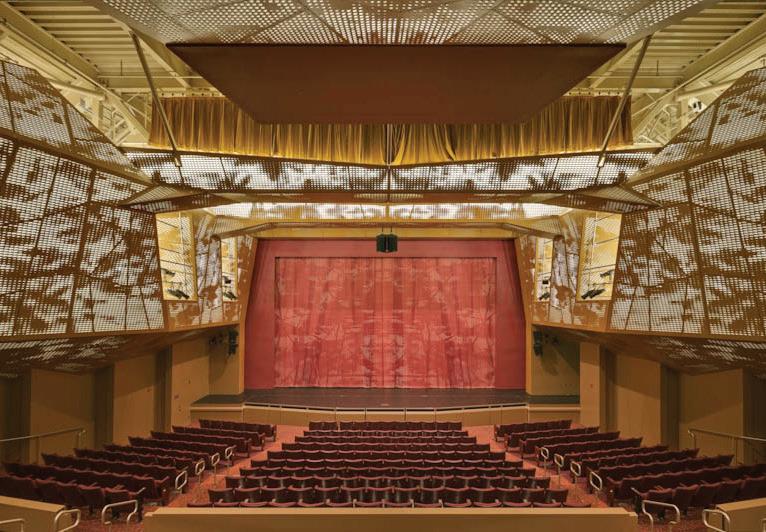

Whether it’s a single room or an entire campus, a school is more than an educational resource. A school is a community where people thrive. Faculty, administrators and parents team up and rally around a common goal: wholly enrich the lives of their students.

So, when it comes to the facilities that house your school community, be sure to partner with a firm you can trust: Blach Construction. With 50+ years of proven education construction experience, Blach will empower you to deliver safe and healthy spaces that inspire learning, creativity and growth – for each and every student.

Team up with Blach and together, we will build bright futures.

CHERYL JORDAN Superintendent, Milpitas Unified School DistrictEveryone learns, and our most impactful learning experiences are shaped by our environment.

The California Association of School Business Officials is the premier resource for professional development in all aspects of school business. Founded in 1928, CASBO serves more than 24,000 members by providing certifications and training, promoting business best practices, and creating opportunities for professional collaboration. CASBO members represent every facet of school business management and operations. The association offers public school leaders an entire career’s worth of growth opportunities.

As the recognized authority in California school business, CASBO is a member-driven association that promotes ethical values; develops exceptional leaders; advocates for, and supports the needs of, members; and sets the standard for excellence through top-quality professional development and mentorship, meaningful collaboration and communication, and unparalleled innovation.

For the past 16 years, CASBO has been dedicated to the organizational planning discipline as a method for guiding the association into a successful future. Last year, the association completed its sixth such plan, CASBO by Design 2.0, a living, breathing document that guided the association in its long-term planning process, which is grassroots in nature, invigorating in procedure and motivating in outcome. Work on our next strategic plan began in 2021.

CASBO has long been committed to organizational planning because the approach has consistently helped the association envision its future and determine the clear steps to get there. The road map that strategic planning provides has allowed CASBO to remain focused on its unique mission, goals and objectives and to respond effectively to a continually changing environment.

For more information on CASBO by Design, visit casbo.org > CASBO + You > About > CASBO By Design.

Stay connected casbo.org

Publisher

Tatia Davenport

Features editor

Julie Phillips Randles

Contributors

Jennifer Fink

Nicole Krueger

Jennifer Snelling

Art Director

Sharon Adlis

Ad Production

Tracy Brown

Advertising sales manager

Cici Trino Association Outsource Services, Inc. P.O. Box 39 Fair Oaks, CA 95628 (916) 961-9999

President

Tina Douglas

San Dieguito Union High School District

President-elect

Eric Dill Carlsbad Unified School District

Vice president

Aaron Heinz Colusa County Office of Education

Immediate past president

Diane Deshler

Lafayette School District

Published September 2023

More than 4,000* school districts prefer our industry-leading benefits education and enrollment support. American Fidelity can work alongside your current Health Trust or Broker to help with:

• Comprehensive benefits planning

• Guided one-on-one benefit reviews (virtual or in-person)

• Ongoing employee benefits education

We’re partnering with school districts in your region. We can work with you too. [americanfidelity.com/state] *American

As the smell of freshly sharpened pencils wafts through the air and the hallways buzz with the excitement of the start of a new school year, it’s easy to get lost in the whirlwind of preparation and organization. But let's pause for a moment and reflect upon something equally profound – the community we’ve built not just as professionals, but as individuals.

The back-to-school season isn't merely about students returning to classrooms, it’s a symbolic representation of new beginnings and the continual cycle of learning. Similarly, our professional network is about much more than just work. It’s about mutual growth, learning from each other, and pushing boundaries to remain relevant in an ever-evolving landscape.

While our primary focus is often on ensuring that schools operate efficiently and effectively, we also have an opportunity – rather a responsibility – to develop ourselves. Our community is one where personal development is championed. We grow not just in our roles, but in understanding ourselves better, in becoming more resilient, more innovative, and, importantly, in finding joy in what we do.

It’s remarkable how much we can learn from our colleagues. From best practices to personal anecdotes, every conversation is an opportunity to gain knowledge. But beyond the professional insights, there’s an undercurrent of camaraderie and friendship that makes our network truly special.

Have you ever stopped to consider the laughs you've shared with a colleague over a cup of coffee? Or the times you’ve exchanged stories from your weekend? These moments, though seemingly mundane, breathe life into our day to day, transforming work from a series of tasks to a journey filled with memories and relationships.

So, as we step into this new academic year, I urge you to also cherish the professional friendships you’ve forged. Reach out to that colleague you haven’t spoken to in a while. Share your recent successes, challenges or a simple, “How have you been?” Let's ensure that while we invest in our students' futures, we also invest time in nurturing our connections and our personal development.

Here’s to another year of growth, learning and finding joy and friendship in our work! z z z

Tatia Davenport CEO

Does

As a Third-Party Administrator (TPA), SchoolsFirst Plan Administration expertly manages the day-to-day responsibilities of California school employee retirement plans.

Districts choose us for:

• Established expertise in administering school employee retirement plans since 1982.

• Extensive knowledge of California school districts.

• Our commitment not to charge district fees.

• Education tools and guidance to help employees with their retirement strategies.

We’re honored districts trust us to operate their plans with the highest level of service and integrity.

We want to help your district too.

As I write this, our schools are experiencing the quiet summer months. Students and many staff are enjoying time off, while classified staff are preparing for a new school year. They’re cleaning classrooms, deploying laptops, ordering textbooks and supplies, and setting the stage for a happy and productive learning environment in the year ahead.

As the new school year dawns, let’s take a moment to appreciate all the hard work we do as classified staff. Our hard work over the summer will make all the difference over the next nine months.

At the start of this new school year, I encourage you to walk around campus and see how excited staff and students are to be back. Look at all the smiling faces, the high fives and the hugs. This excitement is all thanks to the dedication of each and every classified staff member.

As CASBO president, I invite you to celebrate yourself and all classified employees in this pivotal moment. Take pride in your work and take a moment to acknowledge your many accomplishments. Celebrate the classrooms cleaned, the meals prepared and the transportation provided. Celebrate each other for

all you do to support our students and the school business profession.

Let a colleague know how much you appreciate their work. Thank a coworker for making time to meet. Show a colleague appreciation by offering to help them with a task.

These small but significant celebrations demonstrate that you care and are committed to making a difference in public education and the future of our students.

They matter. You matter. And your efforts make all the difference! z z z

Tina Douglas President

Take pride in your work and take a moment to acknowledge your many accomplishments.

Automation is everywhere these days. While economists often consider the effects of automation in terms of whether it creates or destroys jobs, less attention is paid to how it changes jobs and the wages paid to the workers that perform them. While there are cases where automation can create higher-paying jobs, more often it drives wages down. For companies considering automation, this can seem like a boon, as cost savings on labor can increase margins. But, there are also potential downsides, as companies may find themselves in trouble when automated systems falter. Firms should ask themselves three questions when deciding to automate:

1) What are the limits of the technology? 2) How do those limits impact the operation? 3) How does the cost of overseeing technology affect its value proposition?

The COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated the adoption of cutting-edge technologies. From contactless cashiers to welding drones to “chow bots” – machines that serve up salads on demand – automation is fundamentally transforming, rather than merely touching, every aspect of

daily life. This prospect may well please consumers. Forsaking human folly for algorithmic (and mechanistic) perfection means better, cheaper and faster service.

But what should workers – who once provided these services – expect?

Can they also benefit from technological progress? If so, how?

The labor market impact of technology is often viewed through the lens of job creation or job destruction. Economists – with near ubiquity – treat technology as being either labor displac-

ing or labor reinstating. If technology displaces workers, jobs are lost. If technology creates (or reinstates) work, jobs are created. Under this dichotomy, the key question is whether technology creates more jobs than it destroys. The World Economic Forum estimates that by 2025, technology will create at least 12 million more jobs than it destroys, a sign that in the long run, automation will be a net positive for society.

Technology’s job-boosting ability is often touted by tech advocates. Take Waymo, the Google backed startup developing driverless taxis. In recent years, the company’s sensor-laden, white minivans have become a common sight in some American suburbs. However, mobility sans driver raises concerns about job losses. What will otherwise would-be cab (or more likely Uber and Lyft) drivers now do? Waymo’s response? Take up new jobs created by self-driving technology, gigs like self-driving fleet technicians, rider support operators and software engineers. “We can be helpful as a company that creates jobs,” noted one Waymo exec.

Job creation isn’t everything, however. Equally important is what workers can earn for working those jobs. Do wages rise or fall owing to technological progress?

Wages – conventional economic theory posits – are dictated by supply and demand. When jobs require specialized skills, wages rise because fewer people can meet demand for these skills. Wages also rise when workers are – regardless of requisite skill – scarce because there are fewer people available to supply their labor. This explains why pilots earn more than plumbers, chemists more than cashiers. Pilots require more specialized skills than plumbers and chemists are

(in part because of pricy education requirements) less plentiful than cashiers.

Work by the late Alan Krueger hinted at automation’s wage-boosting abilities. Krueger found that computersavvy workers – laborers who worked alongside automation – commanded wage premiums of 10% to 15% more than their computer-illiterate counterparts. Economic historian James Bessen has suggested that over the past two centuries, wages have risen 10-fold owing to technological progress. Bessen credits wage growth for many ordinary workers to new technology. It’s an encouraging story, but unfortunately, it’s also an incomplete one.

Bots may well boost wages, but they can also depress them. Daron Acemoglu and Pascual Restrepo recently found that laborers displaced from jobs owing to automation are often forced to compete with other workers for whatever jobs are left. For example, clerical workers who have been replaced by automation may subsequently seek employment in sectors that have not been automated; say retail work. Their entry into the retail sector causes wages in this sector to drop as clerical and retail workers undercut one another for employment.

But even these findings don’t fully capture the wage impact of automation. The transportation sector – which my colleagues and I have been studying closely – provides a vivid example of yet another way in which technology can depress wages. During the birth of commercial flying, pilots commanded a minimum salary of $2,000 annually ($30,000 today). However, aviators willing to fly at night could earn between at least $2,400 and $2,800 annually. The reason? Night flying was considered more dangerous. Back then, taking flight after dusk required specialized skills and temperament, attributes that were in

short supply. Firms responded by paying hefty salaries to aviators who had these attributes.

However, as technology improved –air traffic-control systems became more mature, aircraft engines more reliable, and cockpit displays more accurate – the risk associated with night flying diminished. Lower risk lessened the necessity for specialized skills and temperament required to manage that risk. The result? A gradual elimination of the skills-based wage premium. Today, pilots who fly at night earn no more than those who fly during the day. Nor do they command a wage premium for flying over hazardous terrain (like mountains). That’s something early aviators could also count on for added earnings because it was considered more dangerous (and hence required more skill).

The wage-hindering effects of technology have been observed in other industries. Cab drivers in London could once command a hefty wage premium. The reason? Becoming one wasn’t easy. Would-be cabbies had to demonstrate encyclopedic mastery of London’s streets, and few could do so. The result was an earnings boost for cabbies: Scarcity after all, breeds value. But along came Uber. The ride-hailing giant equips its drivers with a powerful smartphone app that provides turn-by-turn instructions on where to go and how to get there. Landmarks, street names and routes are all laid out in meticulous detail.

That should benefit aspiring cabbies. And it did. Uber has – since its 2012 entry into London – created jobs for more than 40,000 drivers. It has afforded these drivers an opportunity to “make money and support my family,” as one driver told the BBC. But by purging the need for specialized knowledge, by making ferrying passengers around London easier, the Uber app also purged

the need for encyclopedic mastery that had historically commanded a wage premium. The result? Accusations (and plenty of litigation to boot) that the ride-hailing giant underpays its drivers.

Technology can boost earnings particularly when using that technology demands specialized skills and knowledge. But bots can also depress wages by making some jobs easier to perform. If a job is simple, anyone can do it. And if anyone can do it, why pay some workers a premium? When the market demands fewer skills, workers with anything extra become less valuable. This prospect may please firms. Paying workers less is a surefire way to boost margins. But this strategy is also risky. Technology does not purge the need for human labor but rather changes the type of labor required. Autonomous does not mean humanless. Technology can and will fail. And when it does, firms will confront the prospect of making

nice with the very workers who – during automation’s better days – were shortchanged. In 2018, “Flippy,” a hamburgerflipping robot was forced to the sidelines after one day after being unable to keep up with customers orders. The restaurant’s response? Asking human cooks to step in.

Automation can increase productivity, improve efficiency and reduce errors. Robots can, and should, occupy professions that are too risky for human workers to perform, offer little in the way of purpose and deprive human workers of the joys of free living. Machines have – as Bertrand Russell aptly noted – “given us the possibility of ease and security for all.” Ignoring this reality, reasoned Russell, makes us foolish, “but there is no reason to go on being foolish forever.”

Yet the long-term benefits of forsaking humans for robots are hardly guaranteed. Firms stand to lose cash should the productivity benefits of technology adoption dwarf costs. These costs (and there’s always a cost) are typically discounted by firms keen to show solvency. But adopt-

ing bots can push firms further into the red. Technological singularity – the idea that machines know all, and can fix call –remains, despite what we’re told, a long, long way away.

Firms should consider this reality when adopting technology. Execs should ask themselves three questions when scrutinizing the value of bots. First, what can’t technology do? Technological valor may be dizzying but it too – much like humans – has limits. What are they? Second, how do those limits impact the operation? Investing in tech can boost productivity but only up to a point. What does that point look like and is it acceptable to shareholders? And third, how does the cost of overseeing technology affect its value proposition? Technology should be observed and kept in check. This is particularly true in safety critical industries like transportation, energy, and healthcare. What is the cost of doing so and how does it impact a bot’s cost advantage?

Asking these questions may reveal surprising answers about when (and under what conditions) forsaking human muscle for algorithmic prowess makes sense. There is, as Nicholas Carr notes, no economic law that says that everyone, or even most people, automatically benefit from technological progress. z z z

A version of this article appeared in the November 2, 2021, issue of Harvard Business Review. Reprinted with permission.

©2023 Harvard Business School Publishing Corp.

Automation doesn’t just create or destroy jobs – it transforms them

Piper Sandler is a leader in providing financial services to California schools. Our team of dedicated K-14 education finance professionals has more than 150 years of combined experience and service to the education industry.

General Obligation Bonds | Certificates of Participation | Mello-Roos/CFD Bonds Interim project financing | Debt refinancing/restructuring | Tax & Revenue Anticipation Notes

Timothy Carty MANAGING DIRECTOR +1 310 297-6011 timothy.carty@psc.com

Christen Gair MANAGING DIRECTOR +1 310 297-6018 christen.gair@psc.com

Rich Calabro MANAGING DIRECTOR +1 310 297-6013 richard.calabro@psc.com

Celina Zhao ASSOCIATE +1 310 297-6019 celina.zhao@psc.com

Jin Kim MANAGING DIRECTOR +1 310 297-6020 jin.kim@psc.com

Mark Adler MANAGING DIRECTOR +1 310 297-6010 mark.adler@psc.com

Ivory Li MANAGING DIRECTOR +1 415 616-1614 ivory li@psc com

Pam Hammer OFFICE SUPERVISOR +1 310 297-6023 pamela.hammer@psc.com

MIGRATING ONE OF THE STATE’S largest school districts to a new financial management system is no small feat. But this isn’t Kristi Blandford’s first trip around the block.

Her last district was still relying heavily on paper processes when she came on board and shepherded the transition to digital. Before that, she helped build a $150 million bond program from scratch. Now, neck-deep in the third major financial system upgrade of her career, she’s frenetically busy – and in her element.

“Starting up new things and being that strategic thinker is what I really love,” says the director of fiscal services for San Juan Unified School District. “Give me a project and I’m really happy.”

Blandford’s ability to both wade through the weeds and zoom out to see the big picture stems from her hunger to understand every department her work touches. In more than 15 years with the district, she’s worked in six different positions, including accounts payable, grants and bond analysis.

“I love learning something new. I always wanted to do more,” she says. “I don’t think anything is a waste of time if it helps you see the bigger picture.”

Blandford started her career in school business while taking accounting courses at the local community college. Her mother and stepfather worked for San Juan Unified, so she applied for an entry-level position in accounts payable, where she asked to shadow her supervisor so she could learn more.

She climbed her way through the ranks to accounting supervisor before leaving the district to serve as fiscal support manager for Folsom Cordova Unified School District – a position she occupied for just six months before becoming director of fiscal services.

Two years ago, she returned to San Juan just in time to shepherd the district through another major transition.

“I like being part of the change,” she says. “It’s not always easy, but I’d rather be part of it and make sure it’s done well than have somebody else tell me to change without knowing the why.”

Blandford’s skills as a change leader have translated to her service in CASBO, where she revived the Accounting Professional Council – a committee of one when she began – before becoming president of the Sacramento Board of Directors.

“I’m big on professional development, and I’m excited about getting people to go to CASBO training,” says Blandford, now the Sacramento Section State Director. “I want to grow people. My managers have always grown me for the next position, and I want to do that for other people. I’m really looking at who I’m bringing up behind me.”

In addition to bringing up her successors at work, she’s also been busy bringing up three kids, all in their 20s now. They spend much of their spare time outdoors, camping or attending disc golf tournaments – when they’re not busy serving California’s students. Her husband and oldest son both work in the district, and her son plans to become a teacher.

Although she’s never been interested in teaching herself, Blandford enjoys knowing her work will ultimately help local children succeed.

“It’s my way of helping people and giving back to the kids,” she says. “I love making sure they have what they need and getting as many dollars into their little hands as we can.” z z z

She’s passionate about being part of the change

Over 470 California public school districts have joined together to make SISC what it is today.

We have a 44 year history of providing our members with coverage for workers’ compensation, property and liability and health benefits.

Districts join SISC for our consistently low rates, but they will tell you our service is the reason they stay for decades. We’d love to serve you, too.

Interested in membership?

Let’s talk. Call us at (800) 972-1727 or visit www.sisc.kern.org.

A Joint Powers Authority administered by the Kern County Superintendent of Schools Office, John G Mendiburu, Superintendent

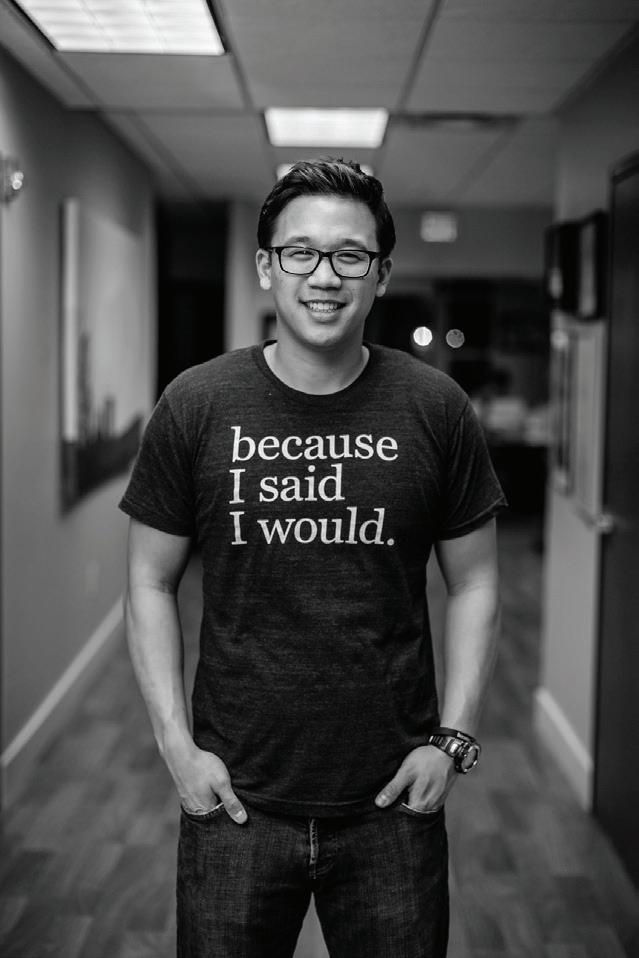

JON PATTERSON FINDS FAMILY wherever he goes, whether it’s in the exhibit hall at the CASBO conference or in a board room demonstrating software to help school districts manage their capital building projects.

It might be a skill he developed while living in close quarters on a submarine in the U.S. Navy. Perhaps he honed it while traveling between California and Hawaii, connecting people with speech-generating devices to help them overcome communication difficulties.

Whatever the case, Patterson has found his professional home as director of business development for Colbi Technologies, a leading provider of capital building management software for school districts. After more than a decade, he knows he’s there to stay.

“It was a match made in heaven,” says the CASBO associate member, who had his first child on the way and wanted to spend more time with his own growing family when he joined the team at Colbi. “They were looking for a salesperson, and I had experience talking with schools. Meeting new people and talking to people is one of my favorite things. It puts me in my element.”

Because the company’s software tools serve a specific niche – districts with an active bond over $30 million – his approach to sales is inquisitive rather than aggressive.

“If they don’t report their spending right, they risk jeopardizing their state funds. If they’re getting a $25 million match from the state and someone screws things up, they can lose that $25 million,” he says. “Our full focus has been on developing relationships and really connecting with school districts to see if we might be a good fit for them.”

Many of those relationships have been the result of his involvement in CASBO, where Patterson has spent the past several years helping the Eastern Section put on events and attract sponsors. One of his favorite times of the year is when he gets to attend the CASBO Annual Conference & California School Business Expo and reconnect with the clients and exhibitors he has come to think of as family.

“I think every single person who works in an administrative position at a school needs to be there,” he says. “The information provided in the sessions alone can help make sure they’re steering their school district in the right direction.”

Patterson, a father of three who spent time as a Navy crewman and an entrepreneur before finding his niche in technology sales, never forgets who the end beneficiaries of his company’s products are. He derives satisfaction from knowing that the building projects he helps facilitate will result in new buildings for kids across the state.

“We’re all doing this for the kids, making sure they have adequate facilities to learn in,” he says. “The kids we’re helping today could be the doctors who are treating us tomorrow or the lawyers we need to defend us against injustice. One new building, one new science lab could inspire them to go down a different path. You never know how it will affect the future.” z z z

He doesn’t have clients or colleagues – he has family

To transform learning through cloud technologies, you need IT Orchestration by CDW®.

The cloud helps keep classrooms connected — no matter where learning takes place. From secure, real-time collaboration among students to enhanced workflows for administrators, see how CDW can help your organization leverage cloud technologies and accomplish more every day.

See how at CDW.com/education

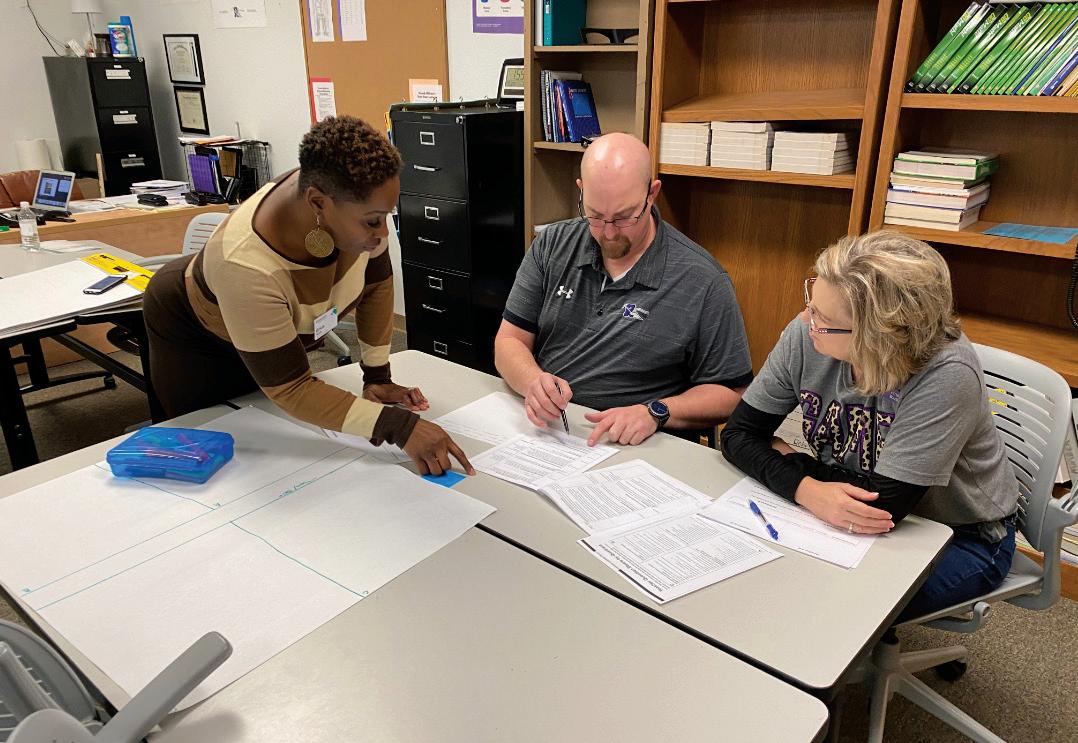

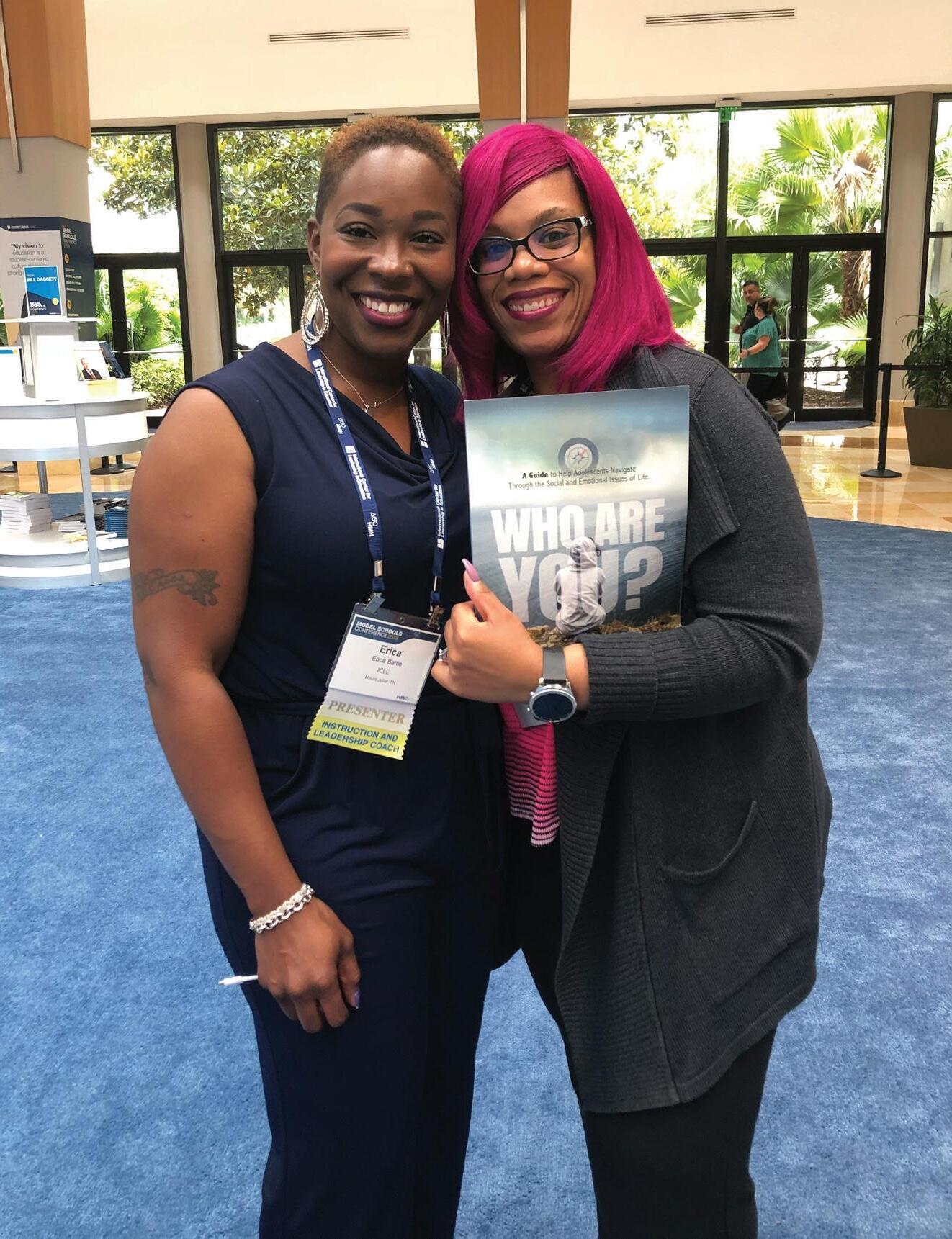

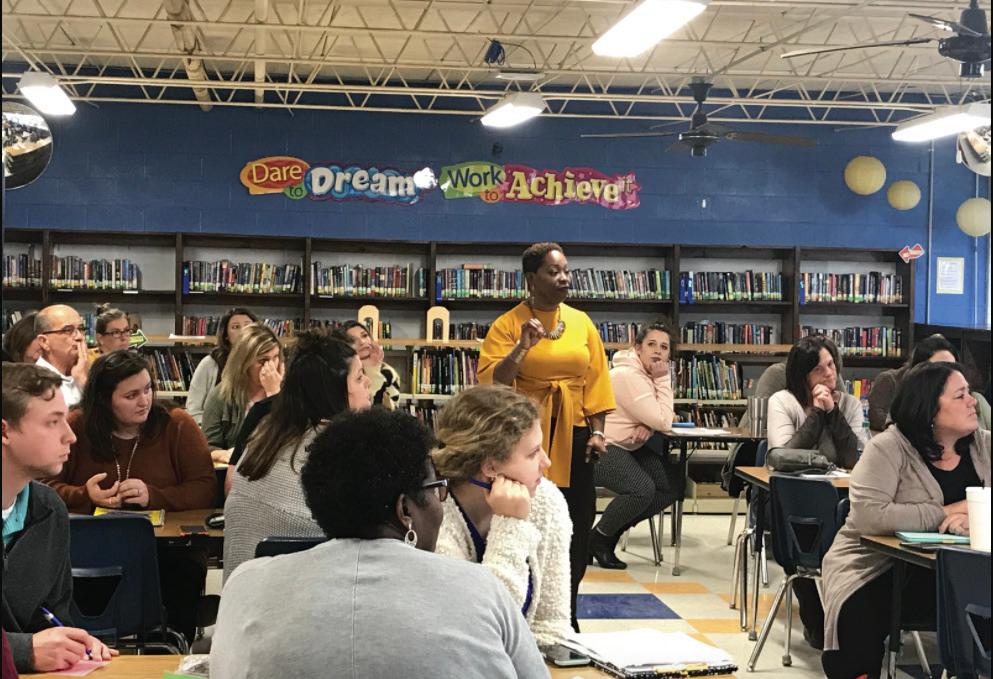

Photography by Kimberly Taylor

@ KimazingPhotography

Photography by Kimberly Taylor

@ KimazingPhotography

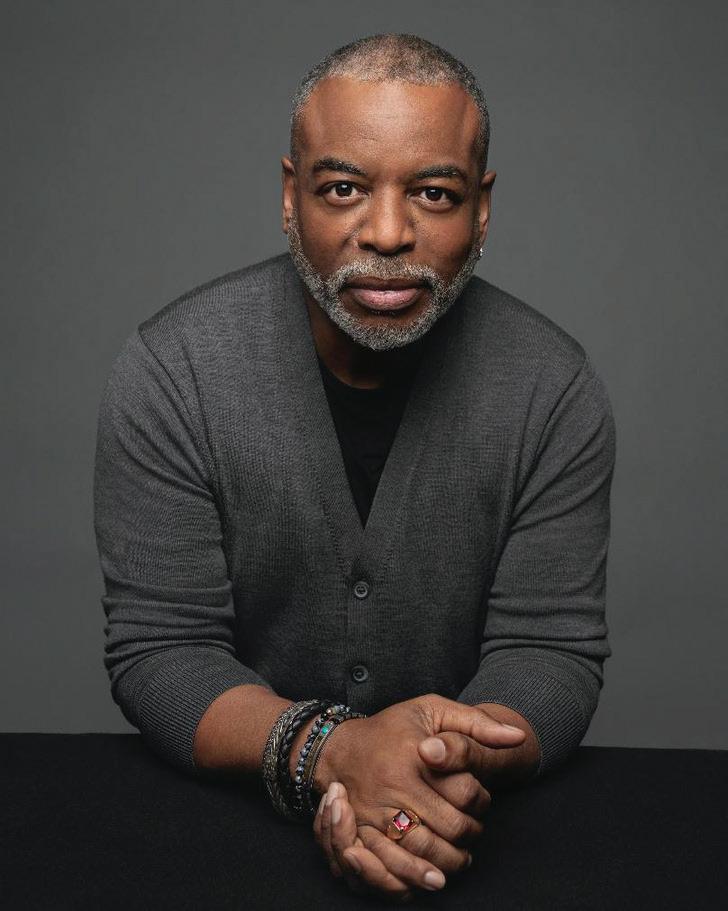

“The best teachers are those who show you where to look but don’t tell you what to see.”

Erica Battle may not have been the first to say this, but she’s definitely the embodiment of this quote she shares on social media. As the leadership coach and thought partner who launched Nashville, Tennessee-based Life Changes in Progress, her focus is on data-driven instruction, but her mission is to uncover the gaps that exist between teaching and learning.

In other words, Battle gives life to phrases like “social and emotional needs of students,” “identifying bias” and “how school culture contributes to student success.”

Take her list of strategies to use in the classroom:

• Make real-world connections.

• Engage in hands-on activities.

• Cultivate critical thinkers.

• Bridge the gap between field trips and guest speakers.

• Harness the power of technology.

• Encourage students to apply their knowledge practically.

• Empower students to work on extended projects that require practical skills, collaboration and problem-solving.

• Authentic assessments.

• Adapt teaching for diverse learners.

The list is neither intimidating nor overwhelming, but in Battle’s hands,

these tools become solutions in the real world.

It’s the wisdom of a woman who began her career in education more than 15 years ago as a substitute teacher, while working her way through college at Tennessee State University to earn a bachelor’s in communications. But her public relations position was soon downsized, and just like that, her career path led back to the classroom.

From that launch, she became an instructional specialist, a teacher mentor and a director of literacy –opportunities that revealed her passion for helping other educators realize their full potential. Along the way, she received a master’s in education at Trevecca Nazarene University, then a

– Alexandra K. Trenfor

master’s in educational leadership at Lipscomb University.

Today, Life Changes in Progress has made a difference in helping educators at Metro Nashville Public Schools, Palm Beach Schools in Florida, the National Elementary Honors Society and the National African American Music Museum, among others. She’s also published a self-discovery book, Who are You? A Guide to Help Adolescents Navigate Through the Social and Emotional Issues of Life

And Battle herself could be considered the ultimate user. She recently gave her first high school commencement speech, where she promised the graduates, “On the other side of failure is success if you don’t give up.”

“It felt like a full circle moment,” she notes.

CASBO sat down with Battle to talk about skills for aspiring leaders, social-emotional learning (SEL), education equity and more.

What’s the best advice you ever received?

I can point to two great pieces of advice that have been extremely helpful in my career in education: Remain flexible and don’t take things personally.

Things are ever changing in education and if we hold on too tight, we’ll miss the important things, so we have to remain flexible.

When it comes to not taking things personally, we have to separate things that are said in regard to practice versus things that are said about you as a person. Feedback or advice about practice is not about you as an individual. It’s meant to provide guidance or assistance, and we have to remember it’s not about your person or character.

What’s one thing you believed that you found out you were wrong about?

When I first started teaching, I was working in a school with a large proportion of students of lower socio-economic status and one of the narratives was that these students didn't want to learn. We were wrong about that. They wanted to learn, but because of their environments and where they came from, they received a message that they couldn't learn.

Kids will rise to expectations, and what I quickly found out was these students wanted to learn just like any other student, but they were never expected to. They were always held to this low expectation, so that's how they performed. It wasn’t until I shifted my expectations of

If excellent communication is not there or you’re not able to read the room, a lot of things get lost in translation.

them – and didn’t lower my expectations based on what others might have said or what their environment indicated –that they quickly rose to the expectations I set.

I had to shift my thinking by putting “best intentions” first.

What are the most important skills for aspiring district office executives to develop?

In answering this, I’m thinking about the various leaders I’ve worked with – the ones who are successful and the ones who are less successful – and considering some of the differences.

One of the biggest differences is communication. District leaders who are extremely successful have mastered the art of effectively communicating with their stakeholders, including their immediate boss, community leaders and school-level leaders. If excellent communication is not there or you’re not able to read the room, a lot of things get lost in translation.

Another thing leaders need to think about, particularly those that have gone from being site-level leaders to district leaders, is that they are now charged with helping achieve the academic goals and student outcomes for the entire district. It’s easy to forget that you’re no longer making decisions for isolated sites, but instead for everyone, so they must be strategic and provide opportunities for everyone.

So, I have to think critically about how decisions will impact the entire district population and I have to recognize the trends in the district and look for opportunities that exist within those trends in order to make decisions that will be best suited for the entire district, and not just a single population.

And I also go back to those great pieces of advice I was given – to be adapt-

able and flexible. The ever-changing nature of education makes those traits a must.

How can school district leaders support the implementation of SEL in schools?

This is a tricky topic because sometimes we think we know what SEL is but, often, we don't have a foundational understanding of what it means to truly address our students’ SEL needs. For example, I’ve seen districts at the beginning of the school year say “We’re going to take the first two weeks to

Remain flexible and don’t take things personally.

establish relationships and determine our students' SEL needs.” My reaction is, well, that’s not really effective because those needs are ongoing, and I might need you to address one competency in the SEL framework one day, and a different one another day.

SEL is a progression, and if as a district the goal is to address students’ SEL needs, there has to be a vision and some objectives in place. And you have to look at your data, and I don’t necessarily mean achievement data. Let's look at the other data that the district has around things like attendance, behaviors and suspensions, and then let’s create an SEL

vision that is connected to those benchmarks and set some objectives.

With this districtwide vision, there needs to be some flexibility and autonomy for schools to say, “Hey, these are the things specifically happening at our site that relate to SEL” and then be able to address the needs of that site.

There also needs to be some professional development, because when we hear terms like SEL, rigor or differentiation, they are all talked about in a context. Often, we don't do the extra work needed to really understand what these things mean. What does it mean when I'm addressing SEL? Sometimes SEL is talked about in the same sentence as mental health and they are not the same thing. Sure, there’s an intersection between them, and it’s true that if we don’t address student SEL, a student might have some mental health problems down the road, but they are not synonymous.

And that's where a lot of the work comes in. We have to create a vision and there has to be some flexibility, but at the same time the district has to do the work of providing leaders with much-needed PD. Perhaps they haven’t been in the classroom in some time, or the student population has changed or needs have changed. We have to provide the learning needed so that everyone feels comfortable addressing SEL.

And then on the back end, after the implementation has taken place, leaders need to be sure they’re allowing the space for collaboration and reflection, and time to make adjustments. They need to ask: What’s working? What’s not working? What do we need to modify? What do we need to abandon? And what resources can we turn to?

I hear a lot that educators don’t have the financial resources to support SEL work. To support the vision, leaders have

Sometimes SEL is talked about in the same sentence as mental health and they are not the same thing.

to put the money where their mouths are and provide the monetary resources to really fulfill implementation.

It might look like this: We implement. We get some data. We review the data. We celebrate the successes we have. We abandon the things that are not working, and we tweak the things that are working to ensure we’re doing better.

What are some specific strategies leaders can use to create more equitable learning environments? One of the biggest things leaders and other educators can do is create an environment where all students, all teachers, everyone feels as if they belong, because belonging is what allows opportunity for the relationship to blossom.

When I have a relationship, whether it’s with my students, my teachers or my leaders, I can see where their deficits are, and I can see where I need to support them. If I don't have an environment where people feel that they belong, there's no trust – so I might never scratch the surface to figure out what areas someone needs support in.

At the same time, you have to set expectations – and I suggest setting high expectations and making it clear that everyone can achieve them. When I first left the classroom and became an instructional coach, my teachers thought I didn’t provide much flexibility. But I told them, “I’m holding you guys to high expectations just like you hold your students to high expectations.” What ended up happening was that our literacy goals, for example, increased dramatically. A lot of that had to do with acknowledging the challenges but keeping expectations high.

Often, when we think about equitable instructional practices or even just the word equity, we automatically go to race;

equity has become synonymous with race. But when we talk about equitable practices, it goes beyond race – it goes back to are we addressing our students' SEL needs? Are we addressing implicit bias within our district? Everybody has a bias. We try to say that we don't, but because we're all raised differently, we all come with a bias. Now is that either good or bad? Well, it could be a negative thing if we don't confront it and address it, because we might not even know it exists.

So, when we talk about equitable practices, it includes addressing the implicit bias that we may have in our district. Are we differentiating our practices based on the needs of our students? And again, I bring up flexibility because what one school site needs in order for practices to be equitable might not be what another site needs.

As a district leader, you have to look through all lenses and be sure you’re considering what will be most successful across all school sites, and ask whether you’re recognizing the different communities inside of the district and what their needs are.

In your TED Talk, you discuss the importance of owning your story. What does that mean and how does it apply to district leaders? When I first started in education, I would never have imagined giving a TED Talk or doing magazine interviews or contributing to journals. I wasn't even an on-time high school graduate, but I have to own that because it’s a part of my life that really fuels the passion that I have now. It’s my story.

It wasn’t that I was not capable of graduating high school on time, it was that when I was in middle school, I had some things happen in my personal life that affected my academic outcomes. But no one took the time to figure out what

If I don't have an environment where people feel that they belong, there's no trust – so I might never scratch the surface to figure out what areas someone needs support in.

was going on with me as a student who had straight A’s and then all of a sudden couldn’t make good grades. When I finally finished high school, I didn't get my first degree until 10 years later. Most people wouldn't know that because I stand on these stages before thousands of educators and I can really speak to the issues with clarity in a way that makes sense.

So that’s part of my story that I initially didn’t want to tell because it didn’t feel good. But if we’re honest and we understand that what fuels our passion is recognizing that sometimes we have hiccups, that really helps fuel who we are as leaders. It’s those hiccups that drive the passion!

Similarly, students sometimes fall victim to their environment, but that does not dictate who they are. So as leaders, we can't forget that we’ve had some curves in the road, some hiccups that we had to overcome to get to this place. It’s about remembering what it took to get you there, while understanding that the people you’re leading and the people they are leading may also be having some hiccups in the road and they may need support, along with the understanding that they are working with their best intentions.

You’ve said failure, disappointment and rejection are good learning tools. What can leaders learn from this triad? I recently gave a commencement address and I told the graduates that failures are opportunities in disguise, they're not opportunities to quit. I believe that if something doesn't work, that means we need to go back and evaluate why it didn't work and determine whether it’s a practice that we need to abandon, tweak or come back to later.

If something is implemented on a district level and it’s not successful, district leaders immediately feel the effects of the failure, and they're the ones who are blamed. They automatically feel rejected. That’s why we have to compartmentalize rejection. Are they rejecting you as a person? Are they rejecting you as a leader? Or are they rejecting the idea that was not successful?

So, again, going back to that advice I shared earlier, practice is not personal. Rejection can feel personal, especially when it’s your idea. As leaders, we have to learn how to compartmentalize those rejections. Was it the idea that was just rejected because your district wasn’t ready yet? Was this failure a direct response to the rejection? What exactly happened?

Leaders should be paying attention to the voices of the teachers and administrators who are expected to implement the decisions leaders make, those who are the boots on the ground.

Are we personalizing it and lamenting in it versus evaluating, looking at the data and finding the opportunities in the failures, finding the opportunities in the rejection, finding the opportunities in disappointments?

For leaders, it can feel personal because they’re responsible for so many people, including students, families and staff. But it can’t be taken personally. Instead, it’s about evaluating and adjusting based on data and the needs of the district.

As a former teacher and frequent educator coach, what’s one thing you think district-level leaders should pay more attention to?

Leaders should be paying attention to the voices of the teachers and administrators who are expected to implement the decisions leaders make, those who are the boots on the ground. Sometimes, decisions are made without the perspective of the people who are responsible for the implementation of the decision. This creates a sense of having to “do what I say” versus creating a community of educators and learners.

We have the opportunity to hear the voices of the actual community at board meetings, but how often do our teachers come to the school board meeting to lend their voices or their perspectives? Not very often. How often do we hold focus groups with our teachers and staff about decisions that we’re thinking about making beyond curriculum selection?

We have to consider what things teachers should have a voice in to ensure decisions aren’t one sided. Before making decisions, leaders should be asking questions like: What’s the underlying trend? Will this decision be beneficial for everyone? What are the perspectives and opinions of the people who are expected to implement the initiative?

You’ve said education equity requires us to meet young people where they are, as they are, and that equity isn’t something you do, it must be who you are. What does that look like for school district leaders?

This looks like recognizing that students come to school with different lenses. If I teach outside of my own culture, say I’m teaching in a lower income school but I grew up middle class, there will be some cultural differences. No. 1, I have to go into that environment thinking that all kids come to learn. Then, I recognize that some kids are going to need a little bit more assistance, without feeling as if I’m giving them a handout. I recognize that I'm going to have to operate in empathy, not in sympathy.

Sympathy is feeling sorry for my kids, but empathy is recognizing that their circumstances may not be the best, but that I’m here to equip them with the necessary skills and strategies so they can be successful. not only academically, but in life.

I also have to recognize that I'm not taking from one group or one population to give someone else a little bit more. What I’m interested in is the deficits that a group or population may have, and providing what they need so they have the opportunity to be successful.

It's almost as if I'm walking into my school district, no matter the demographic makeup, no matter the socio-economic status of the parents, and I’m thinking of their best intentions, and I'm doing whatever is necessary for the success of the students and teachers in my organization. z z z

I also have to recognize that I'm not taking from one group or one population to give someone else a little bit more.Photo by DeMario Howard

New to school leadership? You’re not alone. Approximately one in five chief business officers (CBOs) in California have been in that role for less than two years, according to a 2022 study conducted by CASBO and WestEd.

Many school superintendents and principals are new as well. In fact, across California (and throughout the United States), dedicated, determined professionals are stepping into school leadership roles, often with less on-thejob experience than their predecessors.

While school superintendents, business officers and principals once spent years developing their skills before ascending to leadership roles, today’s school leaders are “put into executive position in a shorter time frame” because retirements and resignations have created vacancies that must be filled, says Edgar Zazueta, Ed.D., executive director of the

Association of California School Administrators (ACSA).

“Before, you might start as an assistant principal, then become a principal, then move up to the central office, become a director, put in some time there and then, maybe, become a deputy superintendent,” Zazueta explains.

Only a few of today’s school leaders have had the luxury of a multi-year informal apprenticeship before being handed the reins. The rest are scrambling to learn as they lead.

“There has definitely been an uptick in demand of people looking for support, and I think it’s a sign of the times,” Zazueta says. “People are eager for leadership and skills training.”

Fortunately, CASBO and other education-focused organizations offer programming to help new leaders develop the skills and confidence neces-

sary to succeed on the job. Experienced school leaders are typically eager to share their advice and hard-won expertise as well.

Use these five strategies to navigate your new role:

The best plans and initiatives won’t be successful if you don’t have buy-in from essential stakeholders. So dedicate considerable time to meeting and establishing relationships with them.

“Any new leader, especially in public education, has to understand the stakeholders who are involved,” says Bill McQuire, a retired CBO and former CASBO president who has served as a mentor to many school leaders.

New CBOs and superintendents often join pre-existing teams, which can

be a challenge. “The culture is there, and it is your job, as the new person, to establish relationships which will effectively continue to bring the team together,” McQuire says.

He recommends that new leaders start meeting and talking with “everybody in the district,” so they can learn about the district’s culture, assets and challenges. “Learn from people before you start making assumptions,” McQuire says. “Ask people, what do you like about your job? What do you like about the district? What don’t you like?” Staff answers will help you better understand the challenges and opportunities that lie ahead.

Get out of your office and meet staff and stakeholders on their turf. “The world does not happen in the business

office,” McQuire says. “Go to the cafeterias. Go with maintenance and operations; go on a bus ride.”

You’ll certainly want to learn about school operations, but don’t forget to connect with the humans who make the school run. Learn their names, what interests them and what they care about. Express genuine interest and concern.

Do the same in the community at large. Connect with stakeholders in business and government. Spend time with students and families. Include time on your calendar for regular meetings and check-ins with stakeholders; relationships (and trust) are built over time.

Relationship building is a foundational part of your job. “If you don’t have good, workable relationships with your stakeholders, how can you possibly

Get out of your office and meet staff and stakeholders on their turf.

support them or provider services that they need?” asks Karen

Stapf Walters, executive director of California County Superintendents.

As an educational leader, you have certain legal and regulatory obligations. County superintendents, for example, have assigned statutory functions, and CBOs also have defined responsibilities. McQuire advises new leaders to “take care of compliance first.” Then, he says, “we can be innovative.”

If you’re not entirely sure what your roles, responsibilities and legal obligations entail, seek support. California County Superintendents maintains “a document that we call the statutory functions document,” Walters says, and each year, the organization updates it to reflect any changes in the law. One of the first things a new county superintendent should do, she says, is get a hold of the most current version of that document. (The organization is happy to share it and answer questions.)

Establishing solid, workable systems that support compliance is a non-glamorous task, but dedicating time to it now can improve efficiency later. “So many people try to take things to the next level first, without creating a solid foundation,” McQuire says. “If we get our ship in order and have our systems running, then we can take it to the next level.”

Similarly, new CBOs can seek support and training to gain a better understanding of their obligations and responsibilities.

“That’s what CBO training is all about,” McQuire says. “It gives you the foundation of what you need to do to be successful, and teaches you what you need to know about all the different areas you’re responsible for.”

CASBO offers a CBO Business Executives Leadership (BEL) Program (bit.ly/3Kq73z0) to help working CBOs obtain practical knowledge and skills in finance, business development and accounting, human resources and more. Individuals who complete the program are eligible to take CASBO’s CBO Certification exam.

Let’s be real: One of the reasons there are so many new leaders in education is because many veteran leaders experienced significant burnout during the pandemic and retired or stepped back. Educational leadership is a tough job that’s only gotten tougher in recent years as demands increased and politicization invaded educational conversations.

Because you are responsible to so many stakeholders, you may feel that it’s necessary to be on call 24/7. That’s a mistake. You, too, deserve rest and relaxation – and, in fact, can only do your best work when you are well-rested and reasonably relaxed.

“Doing a good job requires work-life balance,” McGuire says. “You need to compartmentalize your life: I’m going to get these things done here and do this over here.”

Take care of compliance first. Then, we can be innovative.

Edgar Zazueta, ACSA executive director, encourages school leaders to treat their socio-emotional needs as seriously as they do students’ socioemotional needs. “You can’t take care of others if you don’t take care of yourself,” he says. “Don’t take your health for granted. Make sure you dedicate time for your family and your mental health.”

In fact, educational leaders should create personal wellness goals alongside their developmental goals. “Think about what you’re going to do to take care of yourself over the course of the year,” Zazueta says. “Plan that out and carve out that time, just as you would for anything else in your professional life.”

You may be tempted to skimp on self-care in your early days (and weeks) on the job because you likely feel a mix of excitement, energy, ambition and urgency. Don’t. Prioritizing self-care from the start is one of the best things you can do to sustain your passion and energy.

“You don’t have to do this all by yourself,” McQuire says. Connect with others who can help, advise and support you.

Increasingly, organizations that support educational leaders are offering formal and informal mentorship programs. The Fiscal Management and Crisis Assistance Team (FCMAT) has a year-long CBO mentor program that includes 12, two-day sessions of training; participants are also matched with a qualified and experienced CBO who are available for personal support and assistance. ACSA also has a mentor program that’s open to ACSA members in their first or second year in any administrative position. CASBO is creating, and soon launching, a mentorship program and a coaching program.

You can ask experienced mentors to provide broad support and specific in-

Make sure you dedicate time for your family and your mental health.

When a school district’s plan to secure new Chromebooks with federal funding for its K–12 students was nearly derailed by microchip shortages, ODP Business Solutions delivered.

The school district was set to purchase $6.5 million of new Chromebooks for students in 2021; however, 2020’s global manufacturing strain caused a shortage in microchips that the original equipment manufacturer (OEM) needed to build the Chromebooks. This disruption meant the OEM would miss the district’s deadline, leaving nearly 15,000 students and teachers without vital technology.

Fortunately, ODP Business Solutions already had a solid relationship with the school district, and the teams agreed that keeping the current timeline and working with a new supplier was the best option.

Leveraging its industry experience and connections with other OEMs, ODP Business Solutions quickly found another supplier that had the technology available and could meet the timeline. Once the Chromebooks were delivered, ODP Business Solutions connected with a local Disabled Veteran Business Enterprise (DVBE) to provision each device and rewire 401 carts at the district’s schools to enable charging and safekeeping.

The project was bigger than the delivery of Chromebooks: Its success meant that students and teachers could return to school with the technology they expected.

sight. For instance, if you’re considering implementing a new payroll system, ask your mentor if they have any experience with the systems you’re considering. Their input can help you avoid costly mistakes and inspire you to consider solutions you might not otherwise discover.

It’s equally important to network with other professionals in similar roles. These are the individuals who understand the challenges you face every day, and they can provide support you may not be able to get elsewhere.

“As a leader, you’re supposed to be the person with the answers,” Zazueta notes. “You need someone who’s not attached to your district, someone you can share your vulnerability with and candidly talk through some of your challenges. Find a community of colleagues who will share your struggles and celebrate your successes.”

You likely have a lot to learn – and that’s OK. Tatia Davenport, CASBO’s CEO, advises new leaders to “work with your supervisor to develop a very distinct plan

to grow your skills and knowledge most effectively.”

Together, decide what skills and knowledge you need, and then seek out courses or training. CASBO offers a wealth of learning opportunities, including CBO certification classes; CASBO School Business University (learn.casbo. org), an online portal featuring selfpaced, on-demand courses in accounting, payroll, risk management and more; and CASBO’s professional roundtables, which allow professionals to connect with (and learn from) other professionals in similar roles.

ACSA also offers job-specific academies in 10 different administrative leadership specializations. (There’s a Principles Academy, for instance.) These academies are year-long programs that use a cohort model, so participants also develop close connections with their colleagues.

Additional learning opportunities are under development, so check with your professional organization to see what’s available. Your mentor and colleagues can also point you toward helpful resources.

Work with your supervisor to develop a very distinct plan to grow your skills and knowledge most effectively.

Davenport encourages new leaders to define a learning plan for their first 90 days on the job; this plan should also include times to discuss your learning with your supervisor or mentor. After 90 days, revisit the plan, evaluate your learning and create a new learning plan to address your evolving needs.

You already have the passion and determination necessary to succeed. Use these strategies to beef up your skills and smooth your transition to leadership. z z z

Jennifer Fink is a freelance writer based in Mayville, Wisconsin.

What tips do you have for new school business leaders? Post on X using @ CASBO to share your ideas.

For the 2022-23 school year, Torrance Unified School District (TUSD) tried something it had never done before. It marketed its schools beyond the district boundary, promoting its dual immersion programs and announcing open houses and registration dates on social media.

The small pilot project netted a 40% click-through rate, according to Keith Butler, Ph.D., TUSD’s chief business officer. And the promotion efforts led to enough new enrollments to pay for the social media campaign.

“The beauty of people coming for the first year of kindergarten or transitional kindergarten is that they continue with you,” he says. “The positive impact continues for many years.”

That positive impact is something many California districts are desperately seeking in an era of declining enrollment statewide and nationwide. Michael H. Fine, CEO of the Fiscal Crisis and Management Assistance Team (FCMAT), reports that California's growth rate has gone from 49% in the 1950s to an expected 5.2% between 2020-30, and 3.6% in 2030-40.

In addition to a decline in population growth, the Public Policy Institute of California (PPIC) reports that international immigration to California has slowed, and that 6.1 million people have moved out of California in the last decade, while only 4.9 million moved into the state.

The decline in the growth rate translates to a decrease in the number of students enrolled in the state’s schools. Fine reports that California schools have been in an era of declining enrollment since 2004, with the state losing 475,000 K-12 students.

To make matters worse, the rate of decline accelerated significantly during the pandemic years. For instance, traditionally, kindergarten and transitional kindergarten make up 8.5% of total K-12 enrollment, which has held steady for many years. That number dropped to 7.7% during the pandemic, meaning almost 70,000 fewer kindergarten or transitional kindergarten students. This year, the total two-year kindergarten numbers have returned to 8.5%, indicating stabilization.

“In school business, transitional kindergarten is your first exposure to families. It sets the stage for the train going forward. If your graduating class is higher than your net kinder class, that is a problem,” says Fine.

TUSD is looking at an 18% decline in enrollment over 10 years. Butler recognized the impact decreased enrollment will have on district facilities and services

for students. The decline means a lower average daily attendance (ADA) rate, which translates to less funding.

“That’s why declining enrollment hurts so much,” says Butler. “You are losing a student and that income, but you still have excessive operating costs for the number of students you have. It benefits districts to grow at the margin and hurts to shrink at the margin.”

For example, says Butler, if TUSD brings in 100 new students, the cost of administrating education for those students will mostly stay the same because the district likely won’t need to add new facilities. In contrast, losing 100 students leads to a painful loss of funding.

California is not the only state to face this issue. Population decline is happening on a national level. “While declining enrollment is a national issue, California has more resources to counter it,” says State Superintendent of Public Instruction Tony Thurmond. “For example, we provide preschool for every 4-year-old, two meals a day for every hungry student, and provide a billion a year for arts and music education money.”

The state acknowledges the challenges created by declining enrollment and is taking the following steps to help:

Task Force on Declining Enrollment. Superintendent Thurmond convened a task force charged with developing a toolkit to assist districts. CASBO CEO Tatia Davenport serves as co-chair of the task force, which is also developing a statewide marketing plan for public education.

Hold harmless legislation.

The state passed a law in 2022 that holds districts harmless for declining enroll-

“ In school business, transitional kindergarten is your first exposure to families. It sets the stage for the train going forward.”

ment and allowing districts to compute ADA using the best of three methods of calculations. Historically, funding was based on the current year or prior year’s ADA. If a district is growing, it uses the current year. Declining districts use the prior year to give themselves time to adjust. The state allowed districts to calculate ADA using the average of the three prior years (2019-2022). Districts used whichever number was greatest.

Fine warns that this mitigation strategy is coming to an end. Although the strategy has provided a softer landing, by 2024-25, there will be no pre-pandemic higher ADA years to include in the average.

“The state gave districts one temporary mitigation that has positive consequences for years to come, but

will come home to roost in 2024-25,” says Fine.

Family town hall.

The California Department of Education (CDE) recently held a virtual town hall that garnered more than 30,000 attendees. The listening session explored what districts are doing to keep current students and attract new ones. The Task Force on Declining Enrollment will use this information to develop the tool kit for districts.

Parents said they needed schools to be more welcoming, flexible and help them meet the demands of their family schedules. The state provided $4 billion to help schools make the school day longer and offer better support to families.

“

While declining enrollment is a national issue, California has more resources to counter it.”

Finding unhoused youth. The CDE is preparing to hold a summit on supporting unhoused youth. There are 200,000 unhoused students in the state, many of whom are no longer checking in with schools.

“We are planning to work with districts where unaccounted students are, including homeless students, to get them more resources, transitional housing, money from the federal government to support our homeless count and services for homeless students in our state,” says Thurmond.

Education for district leaders. The CDE recently held a webinar for districts called “Show Me How” to highlight programs that can counter declining enrollment. Featured programs included STEAM/STEM academies, dual language immersion programs and International Baccalaureate programs.

Funding for program improvements. The state allocated money to help schools seeking to convert to dual language immersion programs. In addition, the Reading by Third Grade bill provided $250 million for districts to hire reading coaches and specialists. A 13% increase to the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF) is also intended to help districts provide services.

“We recognize families are making choices, and we have to give them a reason to want to come back to our schools,” says Thurmond. “We are giving schools resources to meet their needs and build programs that will help attract families back.”

Davenport and Butler have several helpful suggestions for what districts can do to continue offering high-quality

“ We recognize families are making choices, and we have to give them a reason to want to come back to our schools.”

Plus, keep your students better focused with the more intuitive user interface, simpler organization, and effortless navigation of Windows 11 Pro.

education that keeps current students and attracts new ones.

Know and understand your enrollment and attendance data. Sometimes the birth rate in a community decreases or families leave the area for less expensive living conditions. Other times, districts may be losing students to private schools or homeschooling. Collect and analyze data to understand what interventions will be helpful.

“Each district has a unique story. Some losses you can control, others you can’t,” says Butler. “Know your community, know the competition, and know why Bobby didn’t show up in August as a third grader. If Bobby is now enrolled at a nearby charter school, what were we not doing for Bobby that the charter school is? Put your creative hats on and be strategic in going about all this.”

Improve school culture and strengthen programming.

During the state’s listening session, parents and students said they wanted a school with a welcoming and inclusive

atmosphere where students feel supported and valued. To achieve this, Davenport recommends programs that promote social-emotional learning, antibullying and mental health awareness. Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief Fund (ESSER) dollars provided an opportunity for many districts to implement those programs.

Other opportunities include offering middle college and early college programs, Expanded Learning Opportunities Programs (ELO-P), STEAM/ STEM academies or career pathway programs, all of which provide additional options for students.

TUSD is in its third year of providing dual language immersion classes at two of its schools. The district has also implemented an early college program in cooperation with El Camino College. And because TUSD recognized parents needed more flexibility for wraparound care before and after the school day, it’s implementing 6 a.m.-6 p.m. supervision for students.

Davenport also suggests offering various learning options, such as online

“ Each district has a unique story. Some losses you can control, others you can’t.”

November 28 - 30

The Premier Tech Conference for IT Professionals in Education

Join us for breakout sessions, hands-on labs, workshops, networking, and much more!

One year of CITE Membership is included with full conference registration.

cite.org/2023conference|@CITE_EDU

or blended learning, advanced courses, and vocational or technical programs to cater to the student body's diversity.

Keep on top of staffing. Butler recommends being aware of where you have temporary and nonclassroom assignments. Business and human resources departments can work together to provide right-sized, highquality staffing. And when it comes to conversations with labor partners, declining enrollment is forcing everyone to adjust expectations.

Theoretically, fewer students mean fewer employees are needed. But as

school leaders know, that’s only part of the story. If a school loses 10 kids across eight grade levels, how does it decide which staffing to cut?

For example, San Bernardino City Unified is projected to lose almost 1,000 students annually over the next 10 years. One thousand kids across a large district with lots of schools only allows for a small reduction in staff, but the 10-year loss of 10,000 will require staff reductions. Staying on top of that as much as possible is key, says Butler.

“TUSD has a history of adjusting classroom staffing based on actual enrollment. As enrollment has declined,

we have adjusted certificated classroom staff accordingly,” says Butler. “These people have lives outside the school, and we care about them. When we have to lay off anyone, it affects us all.”

Address infrastructure.

Make sure facilities are clean, safe and conducive to learning, suggests Davenport, ensuring district schools are as appealing as possible to families. Finally, it may be time to look at letting go of surplus property, as Butler is doing in TUSD. “No one likes closing schools, neither staff nor community like it,” says Butler. “But with declining enrollment, every district will have to look at it.”

Address chronic absenteeism.

Improving options and creative programming can be a way of connecting with students who need to be more engaged in school. Davenport also recommends the following for reaching students who are not showing up to school:

• Comprehensive student and family support services.

• School-based wellness and mental health programs.

• Tiered interventions for positive attendance and behavioral support in a Multi-Tiered Systems of Support (MTSS) or Response to Instruction/ Intervention (RT) program design.

• Coordination of Services Team (COST) interdisciplinary collaborative intervention teams.

• Coordinated home visits and outreach programs.

• School Attendance Review Team (SART) and School Attendance Review Board (SARB) intervention programs.

• Mentoring programs.

Engage the community and market schools.

Butler says there are two things any CBO looks at when there are fiscal challenges. While you must keep tabs on declining revenue, you can also look at ways to enhance revenue.

“In Torrance, we realized we could do a better job with enrollment marketing,” says Butler. “Besides the social media campaign, Torrance looked at the boundary area and targeted families who might want to transfer students into the district.”

Davenport recommends seeking grants or collaborating with other institutions to secure additional support for school improvement efforts. She suggests that school leaders work with local and state policymakers to address broader social issues impacting enrollment, such as affordable housing and economic development.

“Schools are not only going to have to offer programs we know parents want, but also do this thing that schools haven’t had to do, and that’s market,” says Superintendent Thurmond. “You used just to go and enroll in your neighborhood school, but now people have choices, and schools have to learn how to market. We are looking for ways to help our districts have the best programs, promote the best programs, and listen to the needs of parents and families so they feel supported and the barriers get removed so they stay in our schools.” z z z

“ Schools are not only going to have to offer programs we know parents want, but also do this thing that schools haven’t had to do, and that’s market.”

SELF was established to ensure that schools could secure coverage and never have to face the uncertainty of the insurance markets again. Nearly four decades later, the organization continues to be a dependable source of coverage, protecting California’s schools from catastrophic liability losses.

It’s a journey where the people you meet and connections you make will support you for a lifetime ... and where you’ll get the exceptional professional development, advocacy and networking services you need to grow your career and build healthy organizations.

That’s our mission, and we remain committed to walking with you on that path.

If you haven’t already, we invite you to renew your relationship with CASBO. Whether you’re an individual, local education organization or business, we hope you’ll continue to play a critical role in our network!

Stifel is the leading underwriter of California K-12 school district bonds.* We assist local districts in providing financing for facility projects and cash flow borrowing, including new construction, modernization, renovation, and technology improvements. Our work with California school districts includes:

■ General Obligation Bonds

■ Mello-Roos Bonds

■ Certificates of Participation/Leases

■ Short-Term Notes and TRANs

■ Refinancing or Restructuring of Previously Issued Bonds

We give back to the communities we serve by providing college scholarships to graduating high school seniors through Stifel’s annual Fabric of Society essay competition and by supporting school-related foundations and functions with charitable contributions.

* Source: Thomson Reuters SDC, Ranked No. 1 in California K-12 bonds by par amount and number of issues in 2022.

Stifel, Nicolaus & Company, Incorporated

Member SIPC & NYSE | www.stifel.com

Northern California | San Francisco Office

Bruce Kerns Managing Director (415)364-6839 bkerns@stifel.com

Erica Gonzalez Managing Director (415)364-6841 egonzalez@stifel.com

Roberto Lee-Ruiz Managing Director (415) 364-6856 rruiz@stifel.com

Southern California | Los Angeles Office

Dawn Vincent Managing Director (213)443-5006 dvincent@stifel.com

Frank Vega Managing Director (213) 443-5077 vegaf@stifel.com