5 minute read

Bohemian dance

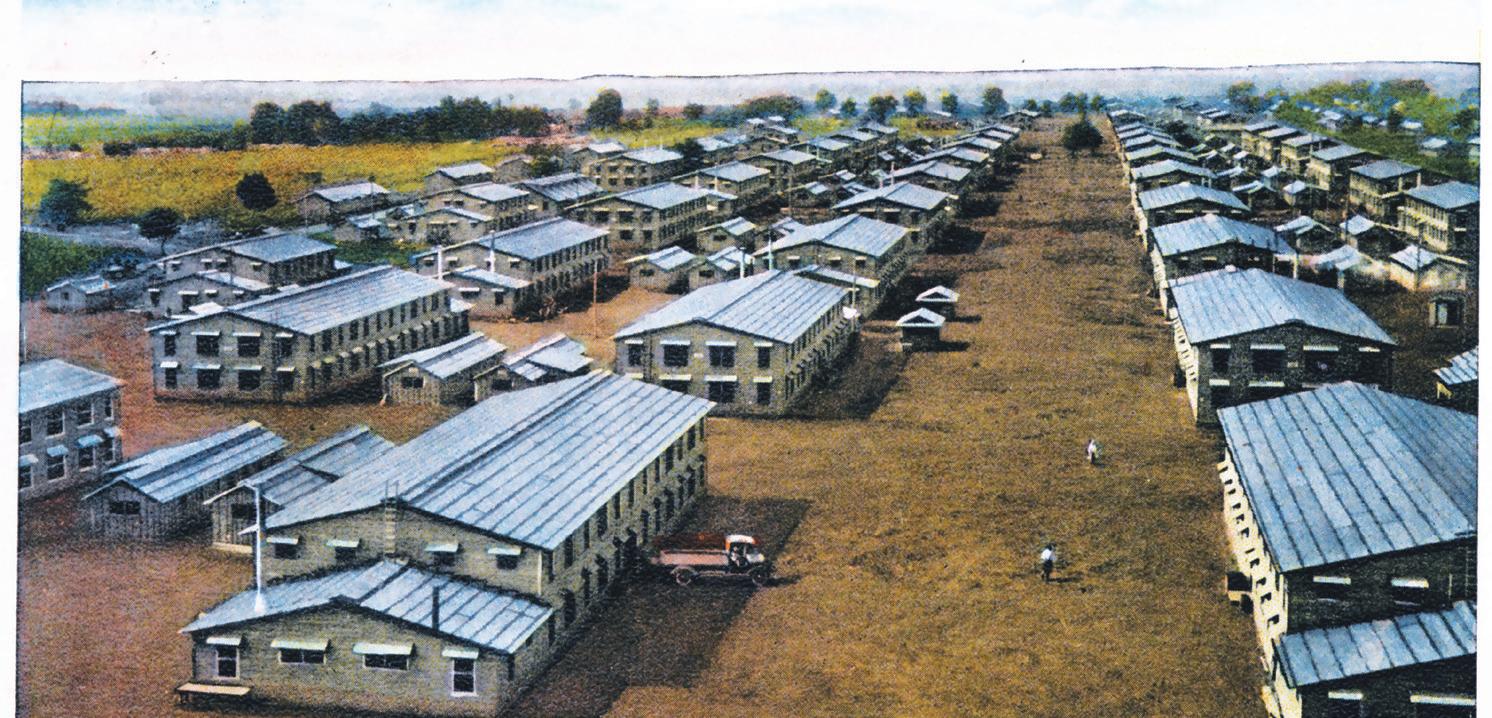

PAST TENSE World War I Camp Gordon continues after war ends

VALERIE BIGGERSTAFF

World War I ended on Nov. 11, 1918, but Camp Gordon, a military training camp built in Chamblee, continued for almost three years. Today, much of that land is home to DeKalb Peachtree Airport. In June of 1919, Camp Gordon was designated a permanent cantonment – good news for Chamblee and Atlanta. The Atlanta Constitution announced, “Thousands of soldiers who were discharged have again re-enlisted in the Army in order to continue in the work they like best.”

The 1920 Census includes 78 pages of those working or associated with Camp Gordon for a total of 3,487 people. Most of those were soldiers living at the camp, but there were also civilians working in jobs such as cooks, laundry, finance, supplies and security. Some of the listings includes wives and children.

Thirty-nine civilians are listed as watchmen, including Edward Clinton Daniel Sr. of Chamblee, who was assigned to guard warehouses near the railroad. The Daniel family history, held by Clint Daniel, shows that Edward Clinton Daniel Sr. was born in 1864 and moved from Greene County, Georgia, to Chamblee in 1908. The family farm was located where Skyland Shopping Center was later built. When post-war work became available at Camp Gordon, Daniel seized the opportunity.

The February 1920 “Society at Camp Gordon” column in the Atlanta Constitution painted a picture of life at post-war Camp Gordon. The hostess house was still entertaining soldiers, the hospital was operational, various sports teams continued, and a Valentines ball was recently held complete with entertainment by a jazz orchestra.

The Educational and Vocation School of Camp Gordon opened in early 1920. Atlanta Mayor James L. Key gave an address to the 200 soldier students receiving certificates from the school in June. (Atlanta Constitution, June 14, 1920, “Certificates awarded 200 soldierstudents at vocational school”)

An announcement of instructions to abandon and salvage Camp Gordon was made in August of 1920, but the city continued to fight to keep it open. Mayor Key went to Washington D.C. to try and save Camp Gordon. (Atlanta Constitution, August 7, 1920, “Strong efforts to retain Gordon”)

By September of 1921, all efforts by the City of Atlanta had failed and an auction date of Oct. 10, 1921 was set. The advertisement listed between 2,500 and 3,000 acres of land to be sold, followed by sale of lumber from barracks. Each barrack consisted of about 66,000 feet of lumber, plus plumbing and a furnace.

DeKalb County bought 300 acres of former Camp Gordon land in 1940 for a future airport. The Navy chose this site to build a Naval Aviation Reserve Base in 1941, which became Naval Air Station Atlanta in 1943.

U.S. Army Cantonment Camp Gordon, circa 1920

PRIVATE POSTCARD COLLECTION

You can email Valerie at pasttensega@ gmail.com or visit her website at pasttensega.com.

Some people never live to enjoy fairness

I got a call from a friend this week to tell me that one of his employees was in the hospital and was not going to survive the next couple of days. He passed away on Thursday. The employee, Jesús, was 36 years old – a couple years older than me – and had been battling cancer for the last 2 months. He didn’t last long.

Jesús left behind two children, ages 13 and 7, and had been their sole caretaker for a while now. Jesús does not have family in the United States, and barring some miracle, his children will end up in the foster care system.

I met Jesús several times when my friend’s company did some work for me. I got to know him a little bit and see firsthand what a good person he was, how hard he worked, and how much my friend admired and appreciated him.

I can still see his sheepish smile and hear his good natured humor. Life, sometimes, is just not fair.

I’ve thought a lot in the last few months about fairness and privilege.

A few weeks ago, while at home for lunch, a door-to-door salesman came by my house to try and sell me a subscription to his food delivery service.

Gregory was middle aged, Black, and frankly, not in great shape. His hair was a mess and he was missing a few teeth. But he was dressed in a suit and tie, had clearly rehearsed and mastered his sales pitch and was invested in the success of his startup company.

We talked for a bit about the company, how he got started, and what he was looking to achieve. He explained that his goal was to recruit 12 new customers a day.

It was hot outside, and I asked him if he’d like a glass of water. He happily accepted – apparently, none of my neighbors had offered.

As he drank the water and we continued to talk, he looked around at my house, at the car sitting in my driveway, and asked me a question.

“Do you have any advice for me? How do I achieve what you have?”

I wasn’t sure what to say. I was maybe 10 years his junior and it’s an awkward question anyways, though I didn’t mind him asking. I imagine he’d had a lot of doors shut in his face and probably appreciated someone engaging in conversation with him.

I wasn’t about to tell this man, who was working his butt off in the hot Georgia sun and had clearly experienced obstacles in life I could only imagine, that he just needed to work hard.

Clearly, he works hard, and so do I, but we have landed in two entirely different positions.

I had the benefit of growing up in a safe community, with great schools, in a well off family. My parents could afford to send me to college and support me so that I didn’t graduate with a mountain of student debt. He didn’t

have any of that. How can anyone say that that has not made all the difference? I think part of the conversation today about fairness and privilege is that it is perceived by some to be an accusation that they haven’t earned what they have in life. I have worked hard for and earned HANS APPEN most of what I’ve received as a consequence of my education and employPublisher hans@appenmedia.com ment. I believe that. But I also believe that I got a head start before I set foot in a classroom or in a workplace that has nothing to do with what I deserve. And it’s a head start that Jesús or Gregory were not given. Two things can be true at once: Some of us receive a head start and make the most of it. Others do not, and have to play catchup. Defending the merits of our own successes, and who deserves what, is a distraction from what should be the ultimate goal: to figure out how we can pay it forward and give good people like Gregory and Jesús a head start, too.

I’m thinking that’s an overstatement, too.