MIGRATION. WOMEN. ARCHITECTURE. + Architecture from Sibling Architecture, Nervegna Reed, Foomann Architects

Edition 2 / 2023

MIGRATION. WOMEN. ARCHITECTURE. + Architecture from Sibling Architecture, Nervegna Reed, Foomann Architects

Edition 2 / 2023

Our range of appliances in Neptune grey is unmatched with a new shade of grey, deep and opaque, together with Galileo multicooking technology redefines culinary experience with contemporary style. Also available in Black.

We acknowledge First Nations peoples as the Traditional Custodians of the lands, waters, and skies of the continent now called Australia. We express our gratitude to their Elders and Knowledge Holders whose wisdom, actions and knowledge have kept culture alive. We recognise First Nations peoples as the first architects and builders. We appreciate their continuing work on Country from pre-invasion times to contemporary First Nations architects, and respect their rights to continue to care for Country.

33 Matsuyama + architect Hiroshi Sambuichi Saran Kim

38 Versailles + architect Anatomies d'Architecture Marie Le Touze

41 Levići + architect Ljiljana Bakić Milana Lević

44 Palawan + architects Khadka and Eriksson Furunes Audrey Leonore Lopez

47 Sampang + architect YB Mangunwijaya Niea Nadya

50 Saigon + architect A21 Studio Khue Nguyen

53 Penang + architect Eleena Jamil Jaslyn Ng

56 Chennai + architect Chitra Vishwanath Sri Akila Ravi

59 Beirut + architect Josiane Adib Torbey Nadine Younès Samaha

62 Bangkok + architect Rachaporn Choochuey Shanica Saenrak Hall

65 São Paulo + architect João Filgueiras Lima Daniela Schnaidman

68 Tehran + architect Kamran Diba Golbarg Shokrpur

71 Penang and Jakarta + architect Eka Permanasari

Bella Singal

74 Hargeisa + architect Rashid Ali

Mulki Suleyman

77 Siedmiorogow Drugi + architect Jadwiga Grabowska-Hawrylak

Paula Sumińska

80 Colombo + architect Minnette De Silva

Thisuni Binali Welihinda

83 Hong Kong + architect Raymond Fung Wing Kee

Phoebe Wong

86 Contributors Architecture

88 Darebin Intercultural Centre by Sibling Architecture

Nikita Bhopti

96 Central Goldfields Art Gallery by Nervegna Reed

Phillip Pender

102 Haines Street by Foomann Architects

Phillip Pender

108 At home with photographer Dan Hocking

113 Office of the Victorian Government Architect Growing cultural competence

In a legislative process coordinated across most of Australia, the Victorian Government in February this year passed legislation entitled the Building and Planning Legislation Amendment Bill 2022, which amended the Architects Act 1991 to provide for automatic mutual recognition (AMR). Subject to notification and public protection requirements, AMR allows architects from participating states and territories to use their state registration to work in other Australian jurisdictions without the need to apply for registration or pay annual registration fees. The Federal Government has similarly been looking at better recognising architectural qualifications internationally, but at this stage recognition pathways exist only with the United Kingdom, United States, Canada, New Zealand, Singapore and Japan. Even then, it’s not possible for an Australian architect to simply practice in those countries with an Australian registration or vice versa. It’s necessary to follow the particular recognition requirements applicable to that country.

While caution is understandably applied before an architect trained in a foreign context can refer to themselves as an architect here or elsewhere, there needs to be increased willingness and equity in recognising the experience, skillsets and character that internationally trained architects bring to our state, particularly in our current industrious circumstances. In addition, simpler visa arrangements would also benefit our profession in times of peak demand. The last few years have seen a cavalcade of parliamentary inquiries and regulatory reviews into building industry practices from 2018’s Building Confidence report, the Parliamentary Inquiry into Apartment Standards and the expert panel’s framework for reform that is still ongoing, and in particular is examining professional registration models. Maintaining high practice standards is of critical importance.

As can be seen in the following pages in this issue, the fascinating accounts of architects from places as diverse as Afghanistan to France, Somalia to China, the breadth of experience is significant and incredibly enriching to our profession, as well as our community. Our own Chapter Council benefits from the knowledge and perspectives of a Councillor from Korea in Gumji Kang, and a Councillor from Lebanon in Nadine Younès Samaha. Nadine has contributed her own story and that of Lebanese architecture to this issue of Architect Victoria. Equally, our Institute has an International Chapter that is larger than several state chapters and provides opportunities for internationally located, Australian-trained architects to gather in places as diverse as Singapore, Hong Kong, Dubai, London or Vancouver while retaining a connection to Australian architecture.

We are truly diversely internationally connected. It is a culturally exciting time to be a Victorian – and indeed a Victorian architect – and we look forward to continuing to work with architects from many different places while maintaining the high standards of architectural practice and output that our community expects.

We live in a world more connected than ever – through travel, the internet, and communication systems that enable the breadth and diversity of our international community to more richly engage with and inform our lives. This issue of Architect Victoria explores the innumerable permutations and combinations available to our community through engagement and specifically through the knowledge and lived experience of architects who have migrated to Victoria from a myriad of locations. Those from a context outside Australia can contribute cultural and educational learnings that inform and diversify our design thinking and problem solving to the benefit of our architectural discourse and built environment.

29 – 31 October 2023

Canberra, ACT

Reflect on what has come before, focus on how we face the future and shape what is yet to come.

Register today at architecture.com.au/conference

Shine Dome | Roy Grounds of Grounds, Romberg and Boyd, Architects | Photographer: Darren Bradley

Shine Dome | Roy Grounds of Grounds, Romberg and Boyd, Architects | Photographer: Darren Bradley

Guest editors

Editorial director

Emma Adams

Editorial committee

James Staughton FRAIA (Chair)

Nikita Bhopti RAIA

Elizabeth Campbell RAIA

Yvonne Meng RAIA

John Mercuri RAIA

Justin Noxon RAIA

Phillip Pender RAIA Grad.

Guest editors

Marika Neustupny FRAIA

Mirjana Lozanovska

Maryam Gusheh

Associate guest editors

Helen Duong

Sonia Sarangi RAIA

Publisher

Australian Institute of Architects

Victorian Chapter, 41 Exhibition Street Melbourne, Victoria 3000

State Manager

Daniel Moore RAIA

Creative direction

Annie Luo

On the cover

Reena Saini Kallat, Woven Chronicle 2018 , Art Gallery of New South Wales, purchased with funds provided by the Roger Pietri Fund and the Asian Art Collection Benefactors

We acknowledge the Traditional Owners of Country throughout Australia and pay our respects to Elders past, present and emerging. We support First Nations peoples in their fight for equity, fairness and justice.

We support an Indigenous Voice to Parliament. Yes.

In the early weeks of February when we invited expressions of interest for contribution to this edition of Architect Victoria (AV), we weren’t sure what to expect. Our publication schedule was fast-paced and we had a very short time to receive EOIs –but when the applications reached over a hundred in just over a week, we knew we were on to something: that there is certainly a critical mass of women architecture graduates from culturally diverse backgrounds who want to speak. That they are willing to share their knowledge and that architecture provides a powerful medium for their stories. We sincerely thank all who expressed interest in contributing. We were moved by the response and generosity.

In keeping with the scope of this double-issue, we bring twenty-four accounts of migration, culture and place through the lens of architecture. We are grateful to our extended team of Helen Duong and Sonia Sarangi. We each worked with a group of four or five contributors over several weeks of intensive engagement. We thank our contributors for their investment in this project. We hope that through these reflections, we can learn and expand our understanding of cultural diversity and its interplay with architecture in Australia.

The cover of this issue is Woven Chronicle, the 2018 installation by artist Reena Saini Kallat, at the Art Gallery of New South Wales. We found great resonance with this work and are grateful for the generous permission to present it here.

This publication is copyright

No part of it may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, mechanical, microcopying, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the permission of the Australian Institiute of Architects Victorian Chapter.

Disclaimer

Readers are advised that opinions expressed in articles and in editorial content are those of their authors, not of the Australian Institute of Architects represented by its Victorian Chapter. Similarly, the Australian Institute of Architects makes no representation about the accuracy of statements or about the suitability or quality of goods and services advertised.

Warranty

2018 © Reena Saini

Kallat, image © Art Gallery of New South WalesPrinting Printgraphics

Persons and/or organisations and their servants and agents or assigns upon lodging with the publisher for publication or authorising or approving the publication of any advertising material indemnify the publisher, the editor, its servants and agents against all liability for, and costs of, any claims or proceedings whatsoever arising from such publication. Persons and/or organisations and their servants and agents and assigns warrant that the advertising material lodged, authorised or approved for publication complies with all relevant laws and regulations and that its publication will not give rise to any rights or liabilities against the publisher, the editor, or its servants and agents under common and/ or statute law and without limiting the generality of the foregoing further warrant that nothing in the material is misleading or deceptive or otherwise in breach of the Trade Practices Act 1974.

“Multiple inhabitance as I am conceiving it here involves the capacity to experience occupying two places at the same time and being situated in them simultaneously without having to move between them.”

– Ghassan Hage

“It is the shift in our own vantage point that changes the way we see the world.”

— Reena Saini Kallat

A place and space to speak

This edition invites migrant women architects and professionals from non-English speaking backgrounds to reflect on and introduce a place and the work of a significant architect from their country of origin. Our intention is for a double reveal: to give voice to, and celebrate, cultural diversity within the Victorian architecture community, and at the same time introduce the AV readership to significant international architects who may be less well known to an Australian audience.

The three pillars set out in the title of this issue –migration, women and architecture – are integral to us as people and to our work as practitioners, researchers and educators in architecture. Our own formative experiences of migration, coupled with engagement with recent women migrant architects and architecture students, motivated us to consider diversity in architecture through the lens of culture and place, alongside gender. We feel this intersection can add insight into the opportunities as well as barriers and inequities that can be experienced by women in architecture and add nuance to the role that cultural difference brings to this dynamic. We want to advocate for and share migrants’ knowledge and capacities, and≈to highlight the creative potential of cultural exchange. Most importantly, we want to use architecture as a medium to build awareness and curiosity, to demystify cultural difference and foster acceptance and exchange.

Our early conversations about the shape and direction of this issue were warm and lively! We are connected by a shared drive to recalibrate the value of cultural diversity to the Australian architecture profession. Our own work, our reflections on migration and our positions of arrival, all informed these initial dialogues. We spoke of experiences spanning many decades, cultures and places.

In November 2019, I attended the Parlour symposium, Transformations: Action on Equity. Over two days, excellent panels and presentations captured important research on gender and equity in the Australian architecture profession. Breakout groups invited participants to reflect on emerging themes and challenges. Drawn to the cultural diversity session, due to my half-Japanese, half-Czech heritage, I was excited to engage with a room full of women architects of migrant background and their allies. But while familiar with many of the challenges facing ethnic minorities, I was shocked to realise that the standout issue of interest was the difficulty in finding work after study. I reflected on my own experience sponsoring a work visa and the emotional and financial impact on both employer and employee. I imagined the hundreds and thousands that endured that process. I thought about the many firstgeneration migrant students I had taught over the years, and how challenging their pathways must have been after study. I thought about the steady increase in the number of fee-paying international students, who invest in our architectural education system but experience little support for their integration within the profession. I realised that the financial risks of running an architectural practice can be amplified for newcomers. In my conversations with the women in that room, the clear need for further work on culture and social class, as it intersects gender, was intensely felt.

I have also spent many years reflecting on Asianness in architecture through research and practice. Using collaborative teaching methods, I have studied the direct vernacular impact of Asian immigration on Melbourne’s urban fabric. Through documenting the physical characteristics of suburbs of Melbourne with large Asian migrant populations. this work has searched for clues on how migrant knowledge and cultural expression have been carried to the Melbourne context.1

2019In doing so, the wonderful inventiveness that resides at the intersection of the built and lived cultures is revealed. For me, such methods are powerful means of advocacy for cultural diversity within the architecture profession. Thinking through ways in which to integrate the values and processes about the work and practice of architecture, together with discussions on culture, gender and social class, crystalised the early ideas for this special issue.

About two decades earlier in 2002, I guest edited the first issue of AV dedicated to architecture and culture. Interviews with architects Marika Neustupny and Eli Giannini, among others, were linked to the exhibition 1st, 2nd, 3rd Generation Australian Architects, alongside the academic conference, Building Dwelling Drifting: Migrancy and the Limits to Architecture. My curiosity in architecture and culture had been first stirred by the migrant houses of my childhood built in the 1960s in the inner northern suburbs – later to become a ‘cosmopolitan multicultural’ destination – in Melbourne. While similar to brick-veneer houses or workers cottages, these houses were also noticeably distinct, and everyone knew it!

My early impressions formed the foundation of postgraduate and ongoing research, working with the premise that migrant houses staged new lives in an unfamiliar context. My work pioneered and forms a significant part of a thriving field of research on migration and architecture in Australia. 2 This includes work on WWII émigré architects, mostly from central Europe, many of whom could not register as architects due to legislation, but found alternative outlets for their architectural visions – Ernest Fooks (Ernest Fuchs) wrote the book, X-Ray the City, and George Molnar (György Molnár) contributed over 3000 cartoons to the Daily Telegraph/Sydney Morning Herald and was later appointed to teach at university. At the level of everyday multiculturalism, this work has highlighted the architectural legacies of ordinary people, most from low socio-economic backgrounds – they reinvigorated local streets with cafes and restaurants; they transformed our suburbs with new architectures, places to worship and ‘open’ housing with terraces right on the street; they planted edible landscapes in backyards and along railway lines; they had cinemas, dance halls and collective picnics in parks. This body of research has further helped demystify migrant success stories by revealing the back-breaking labour of immigrants in nation-building industries, often in regional or remote settings. It has shed light on longer migration spatial histories of Afghan and Indian cameleers who worked with Indigenous peoples in the mid-1800s to navigate the interior of the continent; and Chinese migrants who had moved beyond the search for gold in the late 1800s cultivating market gardens and new enterprises. There is a 20-year gap between 2002 and this edition. Australian scholars informed by research on postcolonial, race, migration and cultural theories, are now changing education with new history programs and design studios – providing an immense resource for the profession.

About two decades earlier in 1983, the Sydney Opera House turned ten. 1983 was also the year when I arrived in Sydney with my family, and set up home at Endeavour Migrant Hostel, Coogee. In what I now think of as a quintessential 1980s Bob Hawke moment, the anniversary of the Opera House was marked by an expansive and inclusive community mural – a temporary installation, 66-metres long and 6-metres tall, resting against the gentle arc of the Tarpeian Rock, the bold sandstone rockface along the north-bound approach to the Opera House. Directed by the Public Art Squad, the project was designed to include contributions by over 150 members of the community, especially young people from High Schools across the city. 3 The mural depicted the Opera House as the background for everyday life and jubilation, fun, humour and colour. There was the portrait of J Ø rn Utzon, projected over his extraordinary work, smiling; the forecourt and cascading steps were filled with figures of all creeds, silliness, weddings, joggers, Matisse’s dancers, tall palms, and significant to our story here, hundreds of balloons floating high above the Sydney blue sky. It was these floating bubbles of white space that were given over to High Schoolers, each asked to paint their own story and expression of identity. The Public Art Squad had held a workshop at my intensive language school only weeks after my arrival in Sydney, later inviting me to contribute to the mural with a motif from my home country of Iran. I vividly recall my nervous excitement as I was hoisted up high on the mural scaffold to illustrate two figures in vernacular dress – folkish, distinctive!

The intersection of migration and architecture has stayed with me and preoccupies my work in many respects. If I was to briefly characterise my research in this area, I would use three words: how ideas travel! And in those animated conversations with Marika and Mirjana, my early experience of migration felt particularly resonant. In 1983, in what now seems like the golden age of multiculturalism in Australia, a community art group designed a light-hearted but ambitious mural as a tribute to the Danish architect J Ø rn Utzon and his magical, fraught, iconic and ultimately beloved work of architecture. Alongside that, they offered a place and space for a diversity of voices, a place and space to speak.

We dedicate this issue to our mothers: Reiko Neustupny, Trajanka Lozanovska, Parivash Parsanejad, Le Kieu Tran, Manjula Sarangi. In particular we have shared memories of Reiko Neustupny, who left us in the early weeks of working on this issue. Her spirit has been with us in the making of this project.

– Guest editors: Marika Neustupny, Mirjana Lozanovska, Maryam Gusheh with Helen Duong and Sonia Sarangi.

Marika Neustupny FRAIA is a director at NMBW Architecture Studio and co-chair of the National Committee for Gender Equity, Australian Institute of Architects.

Mirjana Lozanovska is a professor in architecture at Deakin University.

Maryam Gusheh is an associate professor in architecture at Monash University. She is practice critic at Neeson Murcutt + Neille Architects.

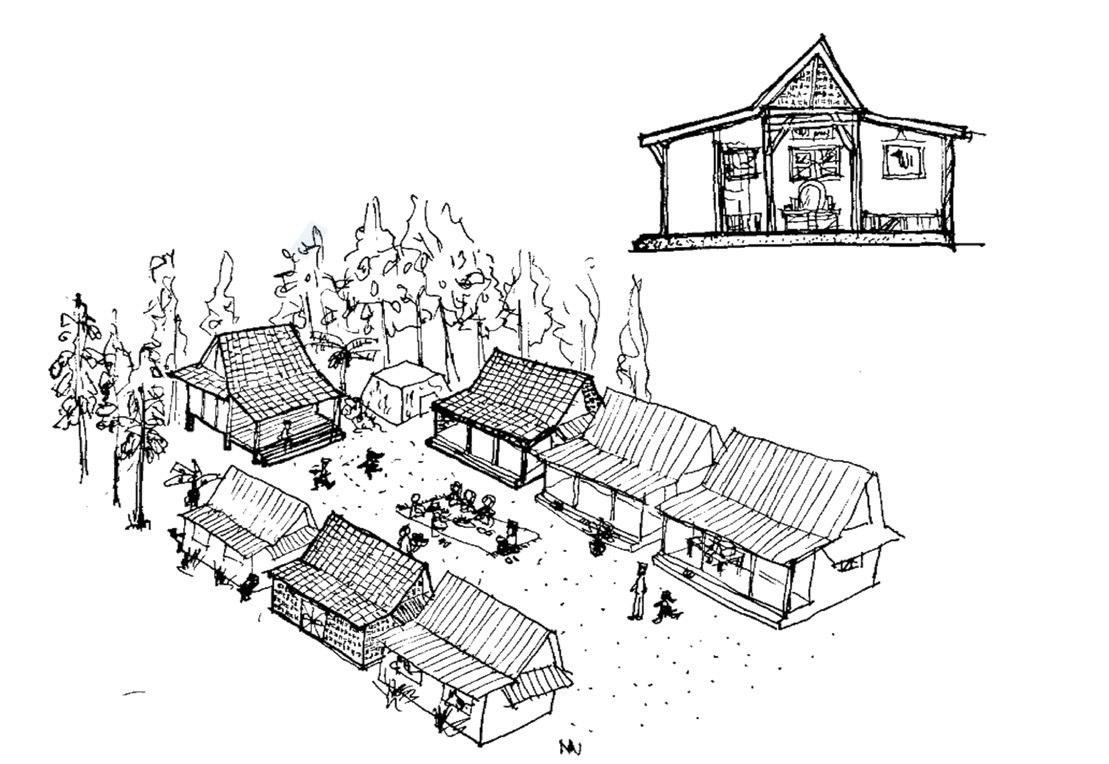

Above Morava Revival, Milana Lević, Masters Thesis, Deakin University, 2022. In this project Milana Lević examines a site between Ballarat and Geelong, long held onto by the Serbian community but in need of reinvigoration. Beginning with an analysis of Morava style of religious buildings in Serbia, the project employs experimental design methods to develop a trans-cultural aesthetic for a contemporary Australian setting.

Notes

1 See: Parlour, https://parlour.org.au/parlour-live/careers-research/; Neustupny, M, “Water + House: The Architectural Design of Water Infrastructure in Urban Dwellings,” PhD Dissertation (University of Queensland, 2019); Neustupny, M and L Harper, “Asian Melbourne: Report on the Beginnings of a Design Research Project,” Fabrications 30:2, 2020, 276–280

2 See: Lozanovska, M, Migrant Housing: Migration, Dwelling, Architecture (London: Routledge, 2019); Levin, I, Migration, Settlement, and the Concepts of House and Home (London: Routledge, 2016); Pieris, P, M Lozanovska, D Beynon, A Saniga and A Dellios, Architecture and Industry: Immigrants’ Contribution to Nation-Building 1945-1979 (ARC DP190101531); https://msd.unimelb. edu.au/research/projects/current/architecture-and-industry-the-migrant-contribution-to-nationbuilding

3 See: Public Art Squad, https://www.publicartsquad.com.au/

HD + SS: In 2002 you spoke with Mirjana Lozanovska in relation to the 1st 2nd 3rd Generation Australian Architects Exhibition (interview published in Architect Victoria, April, 2002). At that time you spoke evocatively about the relationship of migration, culture and architecture. We are grateful you could join us today to reflect on these themes once more, now after two decades of spirited advocacy and practice.

HD: Let’s start with your migration story? When did you arrive? What was it like?

I migrated from Rome to Melbourne with my family when I was 15. I had no desire to move and to be honest it was something of a shock. But as a young person, I didn't have a choice and tried to make the best of it. We arrived in 1971. I finished Year 10, failed my first attempt at the High School Certificate (HSC) because I didn't have enough English – and there was no English language support in those days. You had to write like a native English speaker and compose essays with sophisticated ideas! Besides, I found the curriculum limiting. Back in Italy, I had been engaged in subjects I was interested in, and by contrast found the Australian system generic. I felt constrained – less able to pursue what I wanted to do. So at first, it was a struggle. Then, I changed tack, completed the HSC at a different school and successfully applied to study architecture. It's what I always wanted to do and things started to right themselves after that.

HD: To what extent do you connect these early challenges to the particularities of the Australian environment? Do you feel Australia has since changed?

Australia is a very different place now, but It wasn't so much that 1970s Australia was a difficult place to live. It was more that the Rome I knew was so amazing. Rome has evolved through

centuries, with incredible layers of history and art. I felt like I had been ripped away from my native environment. The mental picture you have of your birthplace is composed of beautiful parts. I still miss the walls of Rome, those walls are so ancient, they make you feel part of the place. It wasn't until I found the incredible beauty of the Australian outback that I felt a similar connection. Of course sometimes it takes time to find and make your own little niche. Our office is in the Melbourne CBD, a fantastic place which I learnt to love gradually. Sometimes you need patience to learn about a place, to understand where the good parts are. Sometimes you work within this grain to craft your own place – the city that you shape and where you belong.

SS: It is moving to hear you talk about the grief of being torn away from your homeland, even now after five decades. The process of adapting to a new culture and environment can sometimes mask the ongoing connection we feel to our country of origin. What are the prompts that take you back and forth between cultures?

I didn't realise at the time, but the experience of migration was actually a gift. I was forced to adapt from one culture to another, and this was difficult, but beneficial. While I felt torn from Italy, I now can’t separate the Italian me from the Australian me. I can now go forwards and backwards between two discrete cultures and see each with fresh eyes.

I'm interested in Italian architects, their work, the materials – there's always something there that somehow finds its way into the work. Like the external stair, which is a building element that doesn't commonly exist in Australia – although my mother lives in a little apartment with an external staircase! I'm sure one of the reasons she bought this house was because it reminds her of traditional Italian houses and spaces. The spatial arrangements that I think about, and can relate to, are also those

An example of an external staircase in an Italian house typology.

Architect: Casa Baldi, Paolo Portoghesi, 1961.

An example of an external staircase in an Italian house typology.

Architect: Casa Baldi, Paolo Portoghesi, 1961.

that are dear to me, those that I know from Italy. On the other hand my approach to architecture was very much shaped in and by Mebourne. I was very lucky to study architecture at RMIT and be taught by people like Peter Corrigan, Peter Elliott and Ian McDougall, and later work for Peter Williams and Garry Boag. These influences, those from Rome and Melbourne have somehow blended into my approach. For example, I draw on typologies in my work, partly because that was what I learnt at RMIT, but also because typology is a traditional method of working in Italy. We would understand building types through their traditional lineage.

HD: It’s interesting that even while studying in Australia, you still felt architecturally linked to Italy. Would you say teachers like Peter Corrigan helped foster confidence in exploring your Italian connection and developing a new language for architecture in Melbourne?

Yes! This was what was great about Peter Corrigan, he always championed the underdog. He purposely brought out people's diverse backgrounds. He encouraged us to learn from that difference. That was his gift.

HD: I think Peter Corrigan's studios were quite rare in that personal history and opinions were always encouraged; diverse backgrounds openly discussed. Do you feel that this kind of approach informs the architecture profession more broadly today? Is there a willingness to embrace ideas from other places?

Peter Corrigan felt that Australia's diversity could inform an inherently Australian architecture, it was his way of framing the local. I don't think this question is present in people's minds anymore. Today with the internet and access to international media, there seems less of a desire to look at our own cultural identity. I think, sadly our views are now blending in with views from elsewhere.

SS: It's sometimes difficult to stand up for the value of cultural connections, experiences and knowledge. What helped you do so?

I go back to the business of having mentors and role models. I had lived in Australia for over 20 years when I first met Anna Castelli Ferrieri, at an intensive winter school by the Milan-based Domus Academy. A significant architect and industrial designer, she was especially well known for her experiments with new materials and furniture design for Kartel. I still remember the sensation that came over me when I met her. Like a shock! She was 75 and I was in my 30s – and I thought: I can be like her. It was a lightbulb moment! It was the first time I identified with someone that I wanted to be like. I'd never met an architect that was Italian, was a woman and was successful at what she did. Maybe we need to invite more international architects to speak or teach here, those who we may not necessarily know about. Maybe we need to help the emerging generation to connect with

those that reflect their culture and sensibility, their ambitions and aspirations.

SS: You really can't be who you can't see. The visibility of diversity has motivated us in this issue. To offer examples of people and models of practice that others may identify with.

Find your tribe, I say. I know that this can be very stultifying because you don't want to put yourself in a tunnel vision. But it can give you that confidence, knowing that someone like you exists out there. And they're a role model to you or a mentor. It just validates you.

SS: You've been working as an architect for over three decades now and speak very positively about your lucky moments in Australia and in architecture, but I'm curious about the professional challenges – along your path to the architectural veteran you are now.

In architecture, like in a lot of creative professions, the rejections are challenging. Rejected applications, running second in competitions, or being completely overlooked. Rejection in a creative field can of course be informative. You see what other people do and learn from it, recognise that your entry didn't hit the important points, and so on. But rejections can also be damaging – when you know that there's no level playing field, when you know that you will go to an interview, and they look at you and ask upfront "Where's your male fellow director? We wanted to speak to them, not you." And then you just feel bamboozled by that rejection because you go, "Hang on. I know things are not equal, but are they this bad?" That's the thing that I've found hardest in my career. Having that moment of confrontation where you think they're not even going to listen.

HD: I think these experiences are shared. When you enter a meeting and your colleague or boss has to say "Oh, actually, Helen's the project architect." How do you respond?

Just keep going. I mean, that was my modus operandi. I just kept going. And at the same time, I also have to say that sometimes being the person that's different in the room – whether it's being a migrant, or because I'm a woman, or because I'm short, I don't know – maybe has some advantages. People do want to be generous, and people do want to do the right thing. Sometimes that has its positive side. Getting my first job as an architect was quite advantageous to be a woman because people were looking for diversity of viewpoints. Architects are generally quite progressive as a profession, so they can be welcoming of diversity, of difference.

SS: I'd like to return to your experience of adapting to English, including expectations around use of architectural vocabulary at university as something that many migrants struggle with. It takes a long time to be admitted to language subsets.

During my first ten years in architecture, we were encouraged to speak in obscure, jargony ways. But after my undergraduate years, during my Master of Urban Design Research I found it difficult to develop a direct vocabulary for architecture and was using excessive florid language which of course made me feel so incredibly clever! I remember putting my work in front of my sister-in-law, who is an editor, thinking "Oh, she'll just do some punctuation and tell me to modify my expression. Instead, she said, "You're going to have to rewrite this from scratch" and knocked it right out of me. I had to work out what I wanted to say in a manner that was accessible and clear. It was a big lesson to learn for myself.

HD: Let’s go back to Rome, was your interest in urban design research connected to your experience and memories of Rome? I don't think there's quite enough conversations about the embodied knowledge that can inform our approach to design, for example the knowledge that comes from lived experiences developed through living in and understanding a city

Definitely. At the time of my master’s, we were talking about the growth of Australian cities. The growth of a city like Rome has been highly problematic because the development of the city periphery has been poor and performed badly. Here in Australia, it's not just the periphery that is growing, everything is growing! So both the similarities and differences between the two cities were very interesting to me. The city is the context of architecture and I wanted to do some work on the context first, so I could better understand how the architecture would fit. My thesis was called Metroscape, it was a way for me to make sense of Melbourne via examples from elsewhere. Sometimes comparisons bring clarity.

SS + HD: We would like to orient our final question towards the contributors to this Architect Victoria issue, to the migrant women architects who have shared their stories and knowledge with the journal audience. What is the one piece of advice you would share with our contributors?

Believe in yourself. Really. The only way you're going to do it is by believing in yourself. And it's terribly hard to do that when you feel like you're just starting and you don't have a lot of knowledge. But one step at a time. Believe that you will get that knowledge and then you will do something good with it. And that you'll succeed in whatever way success looks like for you. Don't take other people's models of success as your model of success. And you have to have that, because as an architect there is the possibility of many negative experiences. So, you just have to quietly keep going.

And I have to say something else. Be kind. Try to be kind in every circumstance. Because there are people like yourself, who have doubts and you don't know the circumstances of people's lives, where they've come from, what they have experienced. Through kindness, I think we can do a lot.

Eli Giannini AM LFRAIA is a principal of MGS Architects.

Helen Duong is director at Pyke + Duong Architecture and associate lecturer at RMIT. Helen is a second generation migrant from Vietnam and China. Having grown up in ethnic markets and restaurants, the intersection between class, cultural exchange and spatial inventiveness continue to preoccupy her teaching and research.

Sonia Sarangi RAIA is a director at Andever, board member (Architeam and AusdanceVIC) and a sessional teacher of architecture at the University of Melbourne. Sonia often thinks of herself as a double-migrant. She is the child of South Asian immigrants to the Middle East, born shortly after they arrived in Dubai. She then undertook her own migration journey to Singapore and finally Melbourne. The duality of being an insider/ outsider as a result of these multiple journeys is one that has deeply shaped her and her practice.

Badru Ahmed

I was born and raised in Dhaka, Bangladesh. After brief periods in Portugal and Sri Lanka, I came to Australia as an international student in 2017. My decision to pursue a career in Australia, and by extension, call it my home, was pragmatic. In comparison with many of my life experiences, Australia felt like a utopia: a place with abundant opportunities and endless rewards for those that work hard.

Introducing my Dhaka

My hometown Dhaka, Bangladesh was put on the modern architectural map by American architect Louis Kahn’s magnum opus: the National Assembly Building of Bangladesh (19611982). It stands like an alien yet majestic monument among the mundane urban fabric of the densely populated Dhaka. My earliest childhood memories of this building include visiting the red-brick paved forecourts with my parents on warm summer evenings, and chasing my sister to the edge, where the iconic concrete forms rise like monolithic giants from the water.

Yet, as awed and enamoured as I was, and in some ways remain by this architectural masterpiece, personal and professional experiences at home and abroad have made me realise that Bangladeshi architecture is practical, resilient, and humble – much like the lives of ordinary Bangladeshis. A generation of Bangladeshi architects, embedded within the chaotic cities and the hot and humid regions, have quietly yet brilliantly addressed local context and the comfort of users and communities at the forefront of their projects.

Below left

Louis Khan’s major work, the National Assembly Building, Dhaka, Bangladesh, 1982. Photographer: Cyrus S Khan, 2010.

Below right

My chaotic yet beautiful hometown, Dhaka, Bangladesh. Photographer: Badru Ahmed, 2016.

Interior of Bashirul Haq home and studio, Dhaka, Bangladesh.

Architect: Bashirul Haq, 1981.

Interior of Bashirul Haq home and studio, Dhaka, Bangladesh.

Architect: Bashirul Haq, 1981.

Introducing architect Bashirul Haq

Architect Bashirul Haq (1942-2020) trained in Lahore, Pakistan (1964) before the political birth of Bangladesh in 1971, and in the US between 1971-1975. After a brief professional stint in the US, Haq made a definitive decision to return home in 1977 to build his practice in Dhaka. Peer and compatriot FR Khan, of Skidmore Owings & Merrill (SOM) in the US, the Bangladeshitrained structural engineer, had advised Haq against it. With a flourishing career at SOM, Khan would later be celebrated as the "father of tubular designs" for high-rise buildings and encouraged Haq to follow suit and build an international career. For Haq, however, the return home was necessary, and a resistance against the drain of local expertise. He was committed to reshaping the newly independent Bangladesh.

Throughout his decades-spanning career, Haq has consistently approached architectural works with a quiet humility, regardless of the scale or program. I was a young impressionable student when I visited his residence and office project. The natural red bricks contrasted the overgrown vegetation and the continuous flow of the terracotta as it bled from the forecourt along the facade and into the interiors –as if the whole form was generated from the same material, the same story of the land. The modest entry arches triggered

a subconscious reference to Louis Kahn’s grand arches. Haq’s were scaled to suit human proportions.

The residence and office are framed around a courtyard, perpendicular to each other, separating functions through form and composition. Carefully placed lightwells, recessed windows and thick walls provide passive environmental control and thermal comfort, representing a sensitive adaptation of Bengali vernacular. Haq’s formal expressions and efficient spatial layouts achieved the precarious balance between local identity and a contemporary approach. Perhaps this experimentation and synthesis cemented his decision to return home.

Architects’ works often reflect their personalities. I first met Haq as a visiting architect for one of my undergraduate courses in 2013, a soft-spoken and patient person, never dismissive and always receptive to the ideas presented by young minds. Haq passed away in 2020 and left a legacy of works that have inspired the next generation of Bangladeshi architects, many of whom have received considerable international exposure in recent years, including the recipients of the Aga Khan Award for Architecture, Marina Tabassum and Kashef Chowdhury.

I am Wenjie and I migrated to Melbourne in 2015 to pursue a Master of Architecture at the University of Melbourne. My childhood was spent moving around due to my family's work arrangements, which took us to various cities and provinces in China, such as Hubei, Fujian, Guangdong and Beijing. Each of these places had its own distinct dialects and cultures – such as Min Nan, Cantonese, and Mandarin – which I found fascinating.

Introducing my Guangzhou Guangzhou, my hometown and where my grandparents live, is the capital and largest city of Guangdong province in southern China. It is a bustling city with commercial developments yet filled with hidden gems that retain a traditional heartland. As a child and adolescent, I spent most weekends visiting my grandparents. They lived in an apartment building in the city's inner areas, surrounded by older buildings. From their apartment window, I would gaze at the contrast between the changing city skyline and the quieter inner-city suburb. The Pearl River quietly snakes its way through the heart of the neighbourhood. Despite the fact we are very used to living in high-rise apartments in such a densely populated city, our traditional cultural values still persist and influence the design of residential buildings. For instance, apartment facades are dominated by rows upon rows of balconies and awnings. Inadvertently the balcony becomes the most obvious and important element in the elevation design. All apartments come with spacious balconies because drying clothes under the sun is a highly-valued ritual. On the other hand, due to the humid and wet climate, we strongly rely on expansive awnings outside each window to protect the indoor spaces from heavy rainfall and frequent thunderstorms. As a teenager, I often listened to the raindrops falling on the awning – a sound I found both soothing and comforting. It often reminded me of the ancient Chinese poem "listening to the raindrops tapping against the banana trees, I have sorrows, yet no sorrows".

Wenjie Cao Golden Ridge upper-cloister, Mountain Golden Ridge, Chengde, China.

Architect: Atelier Deshaus, 2022.

Golden Ridge upper-cloister, Mountain Golden Ridge, Chengde, China.

Architect: Atelier Deshaus, 2022.

This deep connection to culture is evident in the work of one of my favourite architectural practices, Atelier Deshaus, who seeks to explore Chinese cultural identity and values with modern technology. Their impressive work on Golden Ridge Upper Cloister reflects a profound understanding of the spiritual connection between nature and humanity.

The most remarkable aspect is the upper cloister’s unique roof design. Made from a series of steel trusses, then a thin concrete shell and covered with a layer of local stone, it appears to float effortlessly above the ground plane. The weightless appearance is not only visually striking, but also structurally sound and earthquake resistant.

The upper cloister is seamlessly integrated into the surrounding mountain landscape. Gently nestled into the mountain, the temple carefully crafts courtyards and walkways that invite contemplation and reflection. This relationship between the building and the mountain is reminiscent of the Chinese Shanshui painting tradition, where the mountain is not just a static object, but a living and ever-changing part of nature. Similarly, the upper cloister breathes with the rain and the wind, hiding in the mountain's shadow.

As I reflect on my experience of migration, in our era of evolving technologies and ever-changing urban development, my cultural roots continue to provide a sense of belonging and comfort as a strong foundation.

Wenjie Cao is an architect currently working on residential and childcare projects.

Zahra Dhanji

At approximately six years of age, I discovered that the apartment below my family home was occupied by an architectural practice. Its director was the female architect Shama, who became a close friend of my mother’s. From my first visit I was mesmerised – an open-to-sky verandah at the basement led us to a warm and welcoming space, lit gently and delicately with lamps. So began my dream to study architecture. In January 2022, at age 35 and after travelling back and forth to Melbourne, I completed my degree at the Indus Valley School of Art and Architecture, Karachi, and migrated to Melbourne.

Introducing my Gharibabad-Karachi

Gharibabad is a kutchi abaadi – an urban settlement that grows informally in empty large blocks within a planned city, lacking infrastructure or basic facilities. Migrants who come to the city looking for work from the rural areas but cannot afford proper housing settle in these urban gaps; they provide blue collar services to the white collar population living in the

formal settlements. I studied the walls of Gharibabad and saw a multifunctional architectural element on/beside/within it: clothes are hung, livestock is sheltered, vehicles are parked, a portal is carved as an entryway – and also delivers ventilation and light. In essence the wall wears the scars and marks of the present history of its dwellers. It grows with them and supports their life.

Gizri is another kutchi abaadi, this time in the western part of Karachi, just across the main street from where I was living. The intimate streets are almost always for pedestrian use and seem to generate interaction and a strong network of community. They feel like meso-spaces between inside and outside, with temperatures and noise levels much lower than the surrounding formal city due to their compactness and density. During COVID-19, I was isolated for five months in one

SINA-CLF Clinic Momin Adamjee

Centre, Karachi, Pakistan.

Architect: Kamil Khan Mumtaz, 2014.

SINA-CLF Clinic Momin Adamjee

Centre, Karachi, Pakistan.

Architect: Kamil Khan Mumtaz, 2014.

Architecture

of nine formal parts of Karachi managed by the army known as the Defence Housing Authority; I looked towards Gizri and thought about women like me: a mother, a wife, a daughter and a girl with dreams.

In 1957 Kamil Khan Mumtaz started studies at the Architectural Association in London. After returning to Pakistan Mumtaz questioned the validity of his training and its application in a local context. His architecture has evolved from modernist principles towards an interest in the traditional and vernacular and speaks of local building methodologies, heritage and materials as well as spiritual aspects inspired by Mughal and Islamic traditional geometry. Yet including modern technologies makes his work unique and regional. Kamil Khan Mumtaz works with his son at their practice in Lahore, having major works in Lahore and its surroundings. There is phenomenal knowledge contained in his book Architecture in Pakistan 1

I have visited his SINA-CLF Clinic Momin Adamjee Centre, Karachi (2014). As well as contributing through design, Mumtaz’s office aided the establishment of this facility, which provides the only medical amenities in the area. The work is a renovation of an existing courtyard building in Shirin Jinnah Colony, a kutchi abaadi near the coast of Karachi. Catering to the surrounding lower income population of 400,000 residents, it is around 200 sqm with four rooms. The clinic preserves the existing typology of high walls, low relief arched panels with geometric patterns in colour matt-plaster work on the exterior walls and a significant portal for the door to the entrance. On entry the courtyard area feels cool and the shadows of the tree create a peaceful space disconnected from the noise of the lively abaadi outside. A reinforced concrete modular lattice, locally produced, provides ventilation. The materials and human scale are welcoming and the structure feels embedded into the environment of the kutchi abaadi

Zahra Dhanji is a graduate of architecture and founder of Mappedpk. Zahra is currently working in finance and looking for work in her field of architecture.

Alexandra Anda Florea

I left Cluj-Napoca, Romania in 2013, more than two decades after the fall of communism. For me the rigid thinking and inequities of the communist order lingered and remained limiting. I chose Melbourne for my doctoral studies, a place of radically different cultures, systems and society. A place that could offer new experiences.

Introducing my Cluj-Napoca

For over two decades prior to migration, I lived in Cluj-Napoca’s Zorilor neighbourhood, on the outer rim of the historic centre, built during the 1980s. My home was a two-room apartment (49 sqm including a small balcony), one room for me and one for my parents, the latter also doubling as a living space, separated from the kitchen and bathroom with a connecting hallway. All my friends lived in similar apartments and the streets and green areas between the blocks were ours to run around and play in – an austere but spirited urban playground across the whole precinct. Zorilor is representative of a communist development pattern where individual houses with large gardens had been demolished to make room for modern dwellings. Today, the evaluation of this approach has been mixed. Critics point to the profound trauma faced by the villagers who were forcefully removed and the oppressive approach of top-down housing. Such criticisms seem a little reductive, as they limit our potential to learn from the history of the recent past.

Looking back at Zorilor, through the lens of lived experience, I don't see this modern neighbourhood as erasure of tradition. The success and qualities of our domestic world relied upon a proximity to the old city – the contrast and complementary adjacency between the two was enriching. In my daily life, the fine grain of the city offered a break from the brutalist works. In many ways, memories of life in Zorilor continue to dictate my expectations of the livable city: a modest but lively domestic realm alongside historic structures for education, health, leisure and commerce.

Public space with commercial precinct in the background, Zorilor neighbourhood, Cluj-Napoca, Romania.

Architect: Emanoil Tudose. Photographer: Unknown, 1980s. Courtesy of Asociatia Minerva Cluj.

Introducing architect Emanoil Tudose Emanoil Tudose, an architect with an interest in urbanism and systematisation, designed the Zorilor masterplan. He had worked on similar neighbourhoods such as Manastur (1973) and Marasti (1971) in Cluj-Napoca, receiving prizes for components of the Manastur developments in the 1970s. While the majority of these works suffered from incoherent realisation and densification, Zorilor was built as planned and has further evaded contemporary and significant additions and deterioration. With little change to the built inventory of the 1980s, this neighbourhood stands as a clear account of the modernist principles that were inscribed and materialised.

In his design for Zorilor, Tudose contrasted modest and repetitive housing blocks with a generous network of open circulations and in-between courts. In this schema, unprogrammed external void spaces provided a lively support for collective activities, such as playgrounds, meeting spaces, pedestrian pathways and greenery. Such varied programs created a sense of community within this otherwise rational precinct.

The importance of the project lies precisely in the integration of architecture and infrastructure, designed hand in hand and as complementary elements. The design of the car park spaces, for example, illustrate this thinking. Located at the basement of the apartments, the car park absorbed the topographic level change, allowing pedestrian street entry at the front and access to the car park at the lower concourse at the rear. While the formal decisions seem logical and direct, such a solution could not be approved without the support of the Road Department, the agency in charge of vehicular infrastructure in the newly developed precinct. The synthesised approach to the design of architecture, urban design and urban infrastructure delivered by such communist housing models, balanced the regulated measure of the home with generosity and freedom of the urban environment. For me this juxtaposition led to an extraordinary blend of intimacy and vastness.

Right Mix-use blocks with ground level public programs and housing above, Zorilor neighbourhood, Cluj-Napoca, Romania. Architect: Emanoil Tudose. Photographer: Unknown, 1980s. Courtesy of Asociatia Minerva Cluj. Credit Thanks to Asociatia Culturala Minerva Cluj for assistance with the photographs held in their archive. I also appreciate Monica and Patricia Balea’s assistance with the scanned photographs from my parents’ collection. Alexandra Anda Florea is a research fellow at Deakin University.Rehila Hydari

I’m Rehila (pronounced: Ra-he-la); I was born in Afghanistan, in a small town in the district of Jaghori in the province of Ghanzi. Due to conflict and unrest brought on by the Taliban, my family migrated to Melbourne, Australia in 2005. In some ways, it was the experience of a radically different place that drew me to the study of architecture; a sense of curiosity about why we construct environments the way we do and how the built environment can support diverse ways of living.

Introducing my Jaghori

My family home in Jaghori, Ghazni, is now home to my great aunt. A two-storey dwelling, it rests on the side of a hill, a topography which defines two villages. Like many nearby dwellings, it is assembled of local materials, clay, and straw. Immediately in front of the house, a narrow stream flows from a natural spring, the water source for the whole village and their crops. Water distribution is visible on the ground surface, a network of narrow streams, together with a watering schedule that

ensures equitable sharing. The house is in immediate proximity to the village mosque, used for prayer, and in addition, as a classroom, collective ceremonies and guest accommodation. I left my home at the age of four, and before returning in 2015 my memory of the place had faded – but a few visceral recollections remain. Clear memories of a small room at ground level held the details of its earthen floor heated by channels of warm air from a dug-out kiln. My four siblings and I were born on this floor. The only frame for natural light within this intimate room was a singular small window. The wooden balustrades, not polished or neatly cut, but made from branches of nearby trees are retained in my memory through their grooves and texture, the shape and touch.

Temporary installation for No Show exhibition, Sydney Carriageworks, Sydney, Australia.

Architect: Youssofzay + Hart, 2021.

Temporary installation for No Show exhibition, Sydney Carriageworks, Sydney, Australia.

Architect: Youssofzay + Hart, 2021.

This house, this room, and the spot under the small window capture dwellings as primordial support for human life –a recollection of the magical and intelligent network of local streams, the ability to build from materials of the land, and the proximity of a generous public room. These architectural lessons inform my work and invigorate my approach to contemporary architecture. When visiting this home, I think of the sheer resilience of my mother and father to pack what little they could and leave their home.

When the Taliban took over Afghanistan in 2021, many of the Afghan diaspora were concerned about the safety of loved ones that still lived there, and the broader cultural erasure that could follow – as it had occurred two decades earlier. It was at this time that I came across architect Belqis Youssofzay of the Sydney-based practice Youssofzay and Hart. She was working alongside a group of Afghan-Australian artists, poets and lawyers to advocate for the preservation and awareness of Afghan culture. Youssofzay was born in Afghanistan and moved to Australia at a young age. I felt a strong sense of affinity and admiration for her as an Afghan Australian, but also for her social and environmental advocacy through the practice of architecture.

By introducing Youssofzay here, I want to draw attention to the significance of Afghan role models here in Australia. My sense of cultural and ethical alignment with Youssofzay's work enables me to imagine a positive and powerful engagement in the professional world. Such role models are critical to the making of a rich and diverse architecture profession.

The diversity of Youssofzay and Hart’s work and their commissions is impressive – there are small exhibition designs and large-scale collaborative public commissions. Their recent temporary installation, No Show at Sydney’s Carriageworks (2021) speaks to a number of priorities within and across their work. No Show comprises a temporary scaffold for artworks, and has a gentle formal integrity as well as an ability to recede and host work by others. The project evokes a delicate response to the setting, elegant material detailing with respect for sustainable material choices and lifecycle principles. It carefully mediates the human scale and larger shared environment – at once, contemporary, sustainable and sensitive.

Constanza Jara Herrera

After a professional degree in architecture at Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Valparaiso (PUCV), Chile, I started working in landscape architecture, collaborating on public realm design projects while teaching at PUCV. I decided to study a master’s degree in landscape architecture at the University of Melbourne. I have twice represented the University of Melbourne as a student at World Congresses of Landscape Architecture.

I am currently undertaking doctoral studies in the co-design of cultural landscapes with/for First Nations while working as an urban designer in Melbourne.

Introducing my Valparaiso

Composed of forty-four hills and a flat area oriented to the bay, the busy and sometimes worn-down working port of Valparaiso, Chile, is a natural amphitheatre with an urban fabric that clings to steep cliffs and dramatic hills. Its vernacular landscape is tailored to its topography and challenges gravity, creating a spatiality where the old and the new, the poor and the rich crossover a handmade urban design.

Every time I walked Valparaiso’s streets, something new revealed itself. Social relationships emerged and responded to the city’s geometries. Every element of this city was customised by an often-precarious materiality, engineered to adjust to its particular terrain.

I learned the poetics of space in Valparaiso. I moved to the city when I was 18 years old. My curiosity about the artisticphilosophical approach led to PUCV where the curriculum was based on learning to see the world anew and the interrogation of design generators through observation. We often explored unconventional spatial exercises in order to delve into phenomenological understandings, such as drawing the same space multiple times over a period of 24 hours. The concept of ‘letting appear’ is one of the design principles promoted by PUCV – that a design project must be conceived in relation to its context.

Introducing my Valparaiso + architect Cazu ZegersArchitect Victoria

Hotel Tierra Patagonia, Torres del Paine, Chile.

Architect: Cazu Zegers, 2011.

Hotel Tierra Patagonia, Torres del Paine, Chile.

Architect: Cazu Zegers, 2011.

Cazu Zegers, a Chilean architect trained at PUCV, has explored this principle by applying vernacular approaches to built-form projects which merge with the landscape. Since 1991, Zegers’s Santiago-based practice has focused on residential, large-scale built form and large-scale landscape projects, national and international, in an architecture industry traditionally led by men.

Hotel Tierra Patagonia, Torres del Paine, Chile (2011), Zegers’ first hotel, is conceived from the shapes of the wind and the vast landscape of Patagonia. Stone and timber build a structure that embeds itself into a slight slope in the National Park Torres del Paine. The hotel’s building extends into and maintains a dialogue reflecting the magnitude of its territory. At the same time the building is anchored to the earth, giving shelter and embracing the human scale.

Zegers also leads a set of projects called etnoarquitectura (ethno-architecture) that seek to integrate

vernacular techniques by working with Indigenous communities to allow traditional knowledge to reveal itself during the design process. Elements of orientation and symbols present in the designs for a birthing centre, community centres, and hiking routes are expressive without trying to convey a style or represent historical periods. Zegers intends for the design and materials to speak directly to their users.

For me, the attributes of good design include dialogue with the landscape, honest design intent, simple use of materials, localism, spaces that sing, respectful partnerships with collaborators and places that reflect identity and belonging. Vernacular approaches, such as those practised in Valparaiso, encourage such attributes – and perhaps this is why Valparaiso is the principle setting for the enquiry at PUCV. Zegers and her team are an example of how Chilean architecture embraces a spatial-poetic approach to design.

Dragana Jovanovska

The first time I migrated to Australia I was two years old and had no memories of my country of birth, the Republic of Macedonia. Thirty years later, I migrated to Australia again, with a load of memories that did not fit in a suitcase. I was born in Bitola, a city with rich cultural and building history that inspired me to study architecture. Seeing the endless flat terrain, I found my new place to be the complete opposite of Bitola's narrow streets and ancient buildings.

Introducing my Bitola

Bitola was founded in the middle of the 7th century, near the former city of Heraclea Lyncestis (the ancient city dating from

the 4th century BC). I was born and lived in this city surrounded by neo-baroque and neo-classical buildings.

I was intrigued by the detailed facades as well as the design of distinctive traditional houses with upper levels wider than the ground, overhanging the footpaths. Широк Сокак (Wide Alley) is the main street and the centre of Bitola and is a place where I hardly missed a day to walk along. Широк Сокак is where we caught up with friends after school or went for a stroll on our way back home.

The street is graced with neo-classical buildings –retail, cafes and restaurants on the ground floors and residential on the upper levels. To have an espresso in a cafe on Широк Сокак at around midday is a well-known tradition in Bitola;

Stara Carsija (Old Bazaar), late 19th to early 20th century.

Architect: unknown.

Architect: unknown.

on the weekends, the street is buzzing with people, and the cafes are full. Walking along the street, I enjoyed observing the distinct aesthetic and ornamental detail of each building’s facade. The much-loved Стариот Театар (old National Theatre) in Bitola, where theatrical production began, was located here. Unfortunately, some parts of this street were changed forever in the 1950s and 1960s. The old National Theatre building was demolished (overnight) and replaced with a modern cultural centre.

Introducing architect Dimitar Dimitrovski

Dimitar Dimitrovski, has had a significant role in protecting historical buildings in Bitola, and submitting their registration to cultural heritage lists. This role was especially important during the post-war period when many old buildings were demolished and wide-open squares were created for social events or gatherings and political and promotional speeches. It was the socialist era in my country.

At the time when instructions were received to demolish the Star Naroden Teatar (Former National Theatre) in Bitola, Dimitrovski was the director of the Museum for Protection of Cultural Monuments. Dimitar fought against this directive and argued his case with the heritage authorities that were sent from the capital, Skopje. He was told this was a directive from the party in power and had to be implemented.

Dimitar criticised the political intervention in what he regarded as his field of protection and expertise, and argued against state-level authorities that this process of decision making did not value or respect his profession or expertise. He resigned from his position over this significant issue. The Naroden Teatar building was demolished (at night), and his activism has gone down in history, influencing professional standards. Dimitrovski succeeded in protecting many significant buildings that are now heritage-listed, including the Old Bazaar in Bitola. The Old Bazaar is now one of the largest and bestpreserved bazaars in the region.

Saran Kim

Words by Saran Kim

Words by Saran Kim

Although born and raised in Japan, being a zainichi Korean Japanese with a Korean surname has always made me question the relationship between my racial identity, nationality and cultural heritage. In a country where anyone with a nonJapanese name is assumed to be a foreigner, I have embraced Japanese culture and philosophy and feel Japanese, regardless of people’s perceptions. In Australia, where everyone has a unique background, I feel accepted as a person with Japanese heritage. Furthermore, deep connections with Australian architects with Japanese philosophy at their heart has made me better appreciate my cultural heritage.

Introducing my Matsuyama

I arrived in Australia with one suitcase in 2011, straight after finishing primary school in rural Japan. My Japanese language within the English-only environment was helped by haiku poetry. My hometown, Matsuyama, on Shikoku Island, is known as the City of Haiku, with heritage architecture associated with notable haiku poets. Since I was ten years old, haiku became a way of seeing the world – infusing my own sensory experience into the observation of everyday life in 17 syllables. The practice of weaving seasonal words into haiku – learning myriads of names for rain, clouds, air and light – led me to be mindful of changes in the landscape, ultimately informing how I approach architecture.

Whenever I return home to Matsuyama, I visit Dogo, an old part of the city, known for one of Japan's three oldest hot springs, Dogo Onsen. The district encompasses Buddhist temples, Shinto shrines, several bathhouses, a castle ruin and rampart gardens, as well as the Shiki Museum, where haiku poets gather together on special occasions. It is not necessarily the individual buildings, but sensory memories of historical architecture – the smoothness of timber grains, the softness of bath water and the resonance of stone steps – that engender a continuum of time of Dogo within me. Praying at Isaniwa Shrine

in the New Year, appreciating cherry blossom season in Dogo Park (Yuzuki Castle ruin), and cleaning my family gravestones at Hogonji Temple deepened my relationship with the district over time, even since moving to Australia.

Rokko Shidare Observatory, Kobe, Hyogo, Japan.

Architect: Sambuichi Architects, 2010.

Rokko Shidare Observatory, Kobe, Hyogo, Japan.

Architect: Sambuichi Architects, 2010.

Across the Seto Inland Sea from my hometown on Shikoku Island is the mainland city of Hiroshima, where Hiroshi Sambuichi practices. His projects focus on inviting people to understand the forces of nature. Architecture of the Inland Sea1 is his exhibition catalogue, a reflection of his deep understanding of the Seto Inland Sea, the landscape that, although close to my hometown, I knew only on a superficial level. The book has become a portal into rediscovering the landscape in place of visiting in person. The catalogue introduces the Rokko Shidare Observatory (Kobe, Hyogo, 2010) – two hand-sketched sections (summer and winter) showing Mt Rokko, Kobe, the Seto Inland Sea and Shikoku Island illustrate the movement of water to Mt Rokko is enabled by the sun and winds. Focusing on the unique appearance of frost (soft rime) in winter, the catalogue

investigates the condition for the ice to grow – when the air with almost 100% humidity, at below five-degrees temperature, collides with an object at approximately five metres per second. A veil of short wooden sticks are effective in retaining moisture for frost to grow on the observatory while letting air through. The catalogue portrays Sambuichi’s architecture as a series of gentle gestures taking care of place and its microclimate referring to how the Seto Inland Sea and surrounding landscape, including winds, water and the sun, have always been moving and continue to move. His architecture is rational yet poetic, contemporary yet deeply rooted in the memories of the landscape. Sambuichi’s observation of landscape resonates with haiku – situating human experience in nature and admiring a moment in time, and helps me better read, understand and appreciate the sea that is so close to my home.

Saran Kim RAIA Grad. is a graduate of architecture at Architectus and a research assistant at the University of Melbourne.

Below left

Sectional sketches illustrating the movement of water in summer and winter from Mt Rokko across the Seto Inland Sea, Japan. Illustration: ©Sambuichi Architects 2011.

Below right

Soft rime emerges only when the specific conditions of temperature, relative humidity and wind speed are met. Slabs of ice are cut out of the stepped ice terrace in winter and stored in the underground ice room until summer, when they are utilised for conditioning the air. Rokko Shidare Observatory, Kobe, Hyogo, Japan. Architect: Sambuichi Architects, 2010. Photographer: ©Sambuichi Architects 2011.

Notes

1 Hiroshi Sanbuichi, Architecture of the Inland Sea (Tokyo: TOTO, 2016).

Marie Le Touze

Words by Marie Le Touze

Words by Marie Le Touze

I was born in Versailles, France and studied architecture there, for four years, and in Montreal and Buenos Aires before settling in Bordeaux, France. In 2009 I started a nonprofit organisation in architecture, focusing on temporary installations while working for a local office and passing the French architectural registration. My Australian chapter started in 2011, and now represents a third of my life.

During my architecture studies I looked out a window which faced the castle of Versailles. The National School of Architecture of Versailles is in the old royal stables, built between 1679 and 1682. Generations of architects, including my parents, have studied here since it was turned into a school in 1969. My desk was in one of the student workshops located on the first floor. The workshops were not classrooms but double-storey rooms, filled with mezzanines, and the centre of activity with tables, dusty couches, fridges, and old bits of models everywhere. They were open 24/7 to students

and managed by them. Teachers almost never entered this intimidating zone.

Lots of long and late nights have been spent between the thick walls. Generations of students have been working together or celebrating and dancing to the rhythm of the brass bands traditionally created by students of architecture in France. The whole time, the castle of Versailles was always in the background. This huge edifice (which looks so small from my window) still influences, and impacts everything around it, including the local architects whose dilemma it is to build next to such a thing. The profession feels sclerosed by the weight of historical heritage in this town.

This opulent precedent of architecture has been sitting at the back of my mind since I left the benches of my school. Sometimes as a reminder of the weight that history can bear on architecture. Other times as a testament to how well-built things can last! Perhaps coming to Australia was a way to escape an oppressive feeling or maybe developing a passion for light and temporary structures was my way to cope with it.

Le Costil House Renovation, Sap-en-Auge, France.

Architect: Anatomies d’Architecture, 2022.

Le Costil House Renovation, Sap-en-Auge, France.

Architect: Anatomies d’Architecture, 2022.

On 20 June 2022, I went back to this school to visit my friend who is now teaching there. She had organised a lecture for her students to think about alternative ways to build houses in France. I discovered Anatomies d’Architecture (Ad’A), a young architectural practice including a director with a training in anthropology. Their focus was on ecological houses, and selfbuild in France, with a book on this topic, including careful documentation and engaging illustrations.1 Their first and so far only project was the refurbishment of a dilapidated farmhouse located in the domain of the castle of Costil in Normandy. Ad’A approached the renovation of the 83m sq traditional brick house with unprecedented ambitions: 0% concrete, 0% plastic, and 100% natural materials sourced within a radius of less than 100km.

To meet this challenge Ad’A worked with local farmers, lumberjacks, sawmills, quarrymen, masons, historians, researchers, apprentices, and volunteers. They looked deeply into the regional resources, and turned back towards traditional,

sometimes ancestral techniques of construction: hemp insulation, raw-earth coatings, timber frames made of local chestnut and oak, reuse of traditional bricks, recycled corks, foundations made of locust tree trunks, floors made of reused wood windows. For two years, Ad’A carried out the construction themselves while constantly trying to find alternative and local solutions to conventional building. The result is contemporary and sets a precedent for an architecture that takes control of today’s energy building requirements without applying the norm. Given the level of care, time, and involvement they provide at every step of the design and construction process, how will Ad’A proceed – will their business model, in the long term, allow them to maintain this standard for every project? These questions were raised by Ad’A, and resonate with the questions at Bush Studio, where directors Naomi Brennan and myself pay attention to sustainable and locally sourced architecture that often challenge construction industry conventions in remote or regional parts of Australia where we work.

Milana Lević

Words by Milana Lević

I was born and raised in South Australia to two Serbian immigrant parents. Serbian culture was vibrant within our home – my father didn’t speak much English and my grandparents lived next door. The sight of a Serbian Church became associated with my ancestral culture and identity, I felt at home with the people, and I fell in love with the striking ecclesiastical murals that decorated the interior of Byzantine domes and the adorned frescoes at the Woodville Serbian Orthodox Church. My curiosity for architecture flourished and I completed a Master of Architecture in 2022. For my final design thesis project, I explored architecture through a lens of aesthetic and cultural traditions, overlaying architecture and traditional folk costume that highlight Serbian migration and the cultural footprint in Victoria’s architectural landscape.

Introducing my Levići

My father took us back to his birthplace of Levići in the Šumadija region of Serbia in June 2000. The Lević family home, where my father and uncle grew up, was a double-storey stone house painted yellow and had been damaged due to a series of earthquakes. I remember playing in the plum orchards and cucumber fields, and the sweet smell of my grandmother's krofne in the outdoor kitchen. The region is a mosaic of farmlands that sit within a valley abundant with pine, oak, acacia, beech, hornbeam, and linden trees. Monasteries in the unique Morava architectural style are scattered throughout this region. The St Sava Monastery in Elaine, Victoria, founded in 1973, designed by architect Bogosav A Radovanovic, with the addition of the St Alypius Church built in 1981, is a variation of the Morava style. For some time, this Monastery became a social hub for the Serbian Community in Victoria. Its rural setting, fresh air, and surrounding pine and fruit trees aim to replicate the traditional Serbian landscape, and when the community gathers here, it transports me back to Serbia.

Introducing architect Ljiljana Bakić Serbia's architectural history is a melting pot of different styles which, with the modernisation of Yugoslavia, resulted in the cultural and architectural footprint of the late architect Ljiljana Bakić and her husband Dragoljub. The Bakićs who worked at the state-owned firm Energoprojekt, were invited to work in Zimbabwe for the country's newly formed government. As part of Yugoslavia's leading role in the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM), they were called upon to contribute to the decolonisation of newly formed nations.

Zimbabwe’s pathway to independence, like many other newly formed states, found architecture a significant way to articulate and narrate its symbolic status. Ljiljana and Dragoljub were known for their innovative approach, and this cultural

exchange resulted in the golden icon of the Rainbow Towers Hotel in Harare, redefining then typical Yugoslavian style. Expanding on the variations of brutalism, the hotel’s architecture was transformed with round, soft edges and exterior material presenting layered gold tones. These export architectures often developed a modernist extravagance which is also carried through to the internal spaces where more gold creates a celebratory opulence, an economy of glamour, stylishness, and prosperity. Winning several awards in Serbia and Africa, the Bakićs were guided by ideas about the psychological and sociological impact of architecture. Their membership and participation in several African and European architectural communities and educational settings testify to their influence in Yugoslavia and beyond.

Milana Lević is a graduate of architecture.

Words by Audrey Leonore Lopez

Words by Audrey Leonore Lopez

Audrey Leonore Lopez