SHOWROOM

Mondoluce is the sole importer and distributor for iGuzzini in Western Australia.

2016 WA ARCHITECTURE AWARDS, WINNERS IN THE FOLLOWING CATEGORIES: GEORGE TEMPLE POOLE AWARD | MARGARET PITT MORISON AWARD FOR HERITAGE | COLORBOND® AWARD FOR STEEL ARCHITECTURE | MONDOLUCE LIGHTING AWARD | COMMENDATION FOR INTERIOR ARCHITECTURE

This landmark heritage / hotel project Como The Treasury at the State Buildings, stands out for the consistently high level of lighting design throughout its interior spaces and the high quality of the external lighting.

The external lighting makes legible the three historic buildings in an elegant and understated manner, taking into consideration the ambient street light and dealing with the constraints of hotel facade lighting. At street level the entrances are warm and welcoming. Lamps to the St. Georges Terrace frontage have been carefully reinstated, based on historic photographs.

The internal lighting is an essential element in creating an atmosphere of relaxed sophistication, which is appropriate for a luxury city hotel of this calibre. In all of the spaces – ground floor lobbies, restaurants, corridors, private dining facilities and guest rooms – the lighting design has been highly considered and forms an integral part of the interior design. The lighting design uses reoccurring geometries and themes found in other elements of the interior design. It is clearly contemporary, whilst remaining respectful to the historic context.

CLIENT FJM Property ARCHITECT Kerry Hill Architects HERITAGE ARCHITECT Palassis Architects BUILDER Built

DESIGNER DJ Coalition with Best Consultants CUSTOM LIGHT FITTINGS Flynn Talbot ELECTRICAL ENGINEER Best Consultants ELECTRICAL CONTRACTOR Williams Electrical PHOTOGRAPHER Ron Tan

the humble brick + imagination

The possibilities are endless

Making a striking contemporary impact is not always about using the latest high-tech material.

Today we see stunning visual effects, breathtaking architecture and extraordinary innovations all inspired by the humble brick. This outdoor feature wall is a perfect

example, showcasing just how flexible and creative bricks can be. All you need is a little imagination and great bricks.

To find out how we can help you bring your creative ideas to life, call Midland Brick on 13 15 40 and talk to one of our special project consultants or visit us at midlandbrick.com.au

midlandbrick.com.au

The Official Journal of the Australian Institute of Architects: WA Chapter

CONTENTS

4 contributors

5 editor’s message

7 WA chapter president’s message

gender equity

10 gender and architecture

14 architecture: where are the women? 2003 and 2015

18 ‘filling the pool’ – an update

20 national committee for gender equity

24 the hours

socio-economic access

30 are we out of touch? or out of time?

32 architects and housing affordability

34 the nightingale model

40 foundation housing – bennett street

44 304 south terrace

48 academic access at UWA

50 roebourne children and family centre

54 design does matter, but

opportunities and support

60 emerging, emerged, established

64 sprout hub

68 studio, shared

74 on registration

78 3 over 4 under 80 AIA vs ACA

82 more virgins please

88 ten from ten 100 equal access

CONTRIBUTORS

Tanya Trevisan

‘Architecture: Where are the Women? 2003 and 2015’

Tanya is a registered architect and Chief Operating Officer at TRG Properties

Emma Williamson

‘Australian Institute of Architects National Committee for Gender Equity’

Emma is Practice Director and co-founder of CODA Studio

Kieran Wong

‘Are we out of Touch? Or out of Time?’

Kieran is Design Director and co-founder of CODA Studio

Justine Clark / Dr Gill

Matthewson

‘Gender and Architecture’

Justine is an architecture writer, critic, researcher and editor of Parlour: women, equity, architecture / Gill is a researcher, architect and educator based at Monash University and a founding member of Parlour: women, equity, architecture

Marion Fulker

‘’Filling the Pool’ – an Update’ Marion is the founding Chief Executive Officer of the Committee for Perth

Stephen Hicks

‘Architects and Housing Affordability’

Stephen is a Registered Architect

Kerryn Edwards

‘Foundation Housing –Bennett Street’

Kerryn is Projects Manager at Foundation Housing

Bonnie Herring

‘The Nightingale Model’

Bonnie is an Associate at Breathe Architecture

Andrew Mackenzie

‘More Virgins Please’

Andrew is an architectural writer and publisher and Director of City Lab

Dimmity Walker

‘304 South Terrace’ Dimmity is an Architect at spaceagency

Dr Judy Skene

‘Academic Access at UWA’

Judy is Associate Director and Equity and Diversity Adviser at Student Support Services, UWA

Adrian Iredale

‘Roebourne Children and Family Centre’

Adrian is a Director of iredale pederson hook architects

Warranty: Persons and/or organisations and their servants and agents or assigns upon lodging with the publisher for publication or authorising or approving the publication of any advertising material indemnify the publisher, the editor, its servants and agents against all liability for, and costs of, any claims or proceedings whatsoever arising from such publication. Persons and/or organisations and their servants and agents and assigns warrant that the advertising material lodged, authorised or approved for publication complies with all relevant laws and regulations and that its publication will not give rise to any rights or liabilities against the publisher, the editor, or its servants and agents under common and/ or statute law and without limiting the generality of the foregoing further warrant that nothing in the material is misleading or deceptive or otherwise in breach of the Trade Practices Act 1974.

Important Disclaimer: The views expressed in this publication are those of the individual authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Australian Institute of Architects. Material should also be seen as general comment and not intended as advice on any particular matter. No reader should act or fail to act on the basis of any material contained herein. Readers should consult professional advisors. The Australian Institute of Architects, its officers, the editor and authors expressly disclaim all and any liability to any persons whatsoever in respect of anything done or omitted to be done by any such persons in reliance whether in whole or in part upon any of the contents of this publication. All photographs are by the respective contributor unless otherwise noted.

Michelle Bui

‘Design does Matter, But’ Michelle is a final year architecture student and activist with the Refugee Rights Action Network

Jaxon Webb

‘Emerging, Emerged, Established’

Jaxon is a Designer at Post- Architecture

Kate Fitzgerald

‘Sprout Hub’

Kate is Director of Sprout Ventures and Whispering Smith Architects

Beth Parker / Nic Brunsdon

‘Studio, Shared’

Beth is Community Manager of Claisebrook Design

Community / Nic is co-founder of Spacemarket and Director at Post- Architecture

Mimi Cho

‘3 Over 4 Under’

Mimi is Chair of EmAGN WA

Graham Edwards AM ‘Equal Access’ Graham is the former State President of the Returned and Services League of Australia (WA)

Editor Olivia Chetkovich

Managing Editor

Michael Woodhams

Editorial Committee

Emma Brain

Jaxon Webb

Adriana Chiera

Magazine Template Design Public Creative www.publiccreative.com.au

Proofreading

Martin Dickie

Publisher Australian Institute of Architects WA Chapter

Advertising Kim Burges kim.burges@architecture. com.au

Produced for Australian Institute of Architects WA Chapter 33 Broadway Nedlands WA 6009 (08) 9287 9900 wa@architecture.com.au www.architecture.com.au/wa

Cover Image 'Plaster and Roofing, Lakewood, California' (1950) by William Garnett. Source: J Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Internal Covers

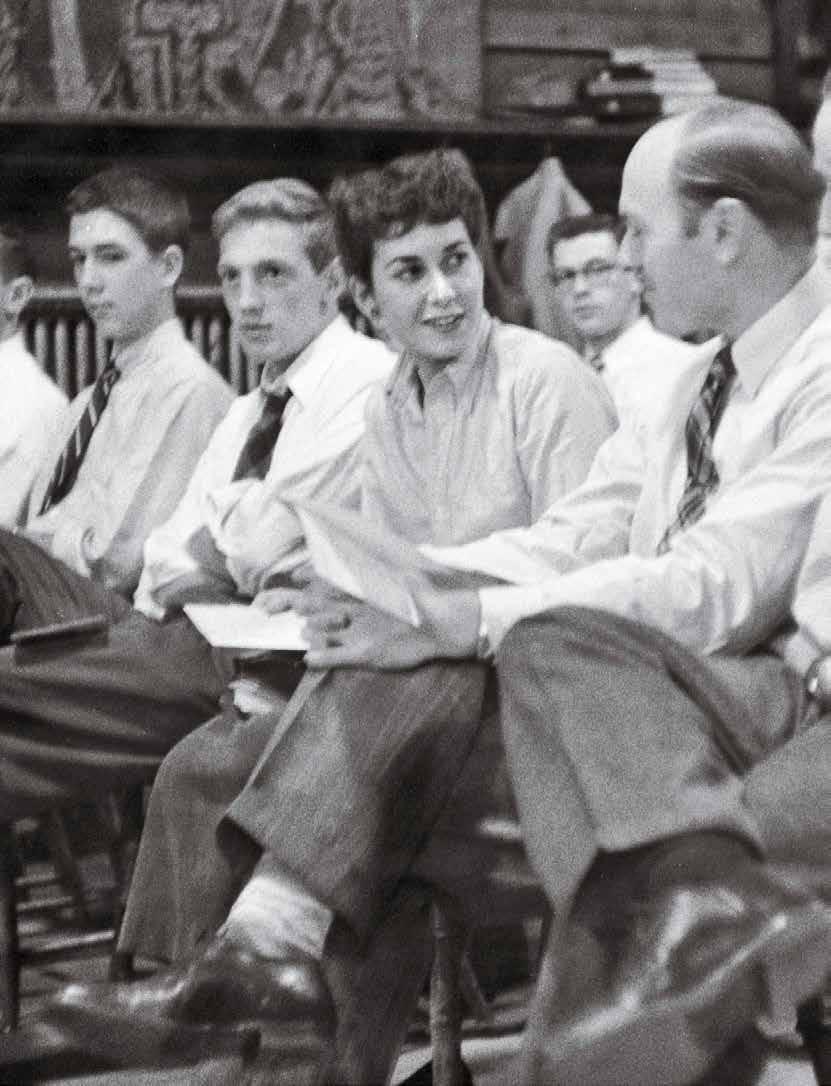

1: 'Nancy Fisher '54 sits in on a Lecture with Harvard men'.

Source: Radcliffe Archives, Schlesinger Library

2: 'Foundation and Slabs, Lakewood, California' (1950) by William Garnett.

Source: J Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

3: 'Cheerleaders: Human Pyramid'. Source: East Tennessee State University

Price: $10 (inc gst)

AS ISSN: 1037-3460

editor’s message

Author Olivia ChetkovichI had been wanting to do an issue of The Architect on gender equity for some time and as I started to think about this more seriously earlier this year I felt I was seeing this topic everywhere. And it wasn’t just Trump delivering an outrageous sexist comment every few weeks, cranking the media machine. On the ABC particularly I was seeing and hearing more women - for example the visible increase in the number of female hosts and commentators on current affairs programs and the election campaign coverage on TV and radio.

As we worked on this issue of The Architect I conceded this may have just been frequency illusion at play. And then in September John Howard said: ‘It is a fact of society that women play a significantly greater part of fulfilling the caring role in our communities, which inevitably places some limits on their capacity’. He went on: ‘Some people may say, “What a terrible thing to say”, and it’s not a terrible thing to say, it just happens to be the truth and occasionally, you’ve got to recognise that and say it’. Of course, he’s not wrong. And yes, we do need to recognise issues of inequity – Howard’s comment was in relation to his belief that the Liberal Party is unlikely to ever achieve its goal of equal gender representation in Parliament. However, it is one thing to recognise and accept a fact of societal inequity, and another to recognise and address it.

As we brainstormed the development of a ‘gender equity’ issue for The Architect, our concerns around issues of equity naturally expanded to encompass many other forms of equity in architecture. It became obvious that we were talking about some broader themes: access, opportunities, support, flexibility, innovation. The Spring 2016 issue of The Architect thus examines EQUITY in architecture in terms of gender equity in the profession, socio-economic access to architecture, and opportunities and support for practitioners. Each section of the issue has a headline piece introducing the angle of EQUITY, providing some context to the issue and prompting thought. How we as an industry further examine, respond to or tackle the issues follows with a variety of initiatives, projects and propositions. Not just recognition of an issue of equity, but how we address it. Our regular ‘ten from ten’ feature examines equity a little more broadly and we have insights from within and outside the architecture community.

In light of some of the questions asked in this issue, it has been interesting to consider the difference between ‘equality’ and ‘equity’. The former is a state of parity – of being the same as, the latter a quality of fairness. They are not the same thing and I feel that addressing issues of (in)equity is necessary to realise a state of genuine equality. Do we need to treat people differently in order for them to be treated the same? Questions of affirmative action and the semantic minefield of ‘merit-based selection’ continue to polarise positions on this topic.

As the issue came together and I reviewed the content, it became apparent that ‘equity’ was as much about ‘access’ as anything else. Access to a career path, access to quality design (although is this always the most important issue for clients?), access to home ownership, access to the market. Our back page piece addresses access in design head on. And in promoting access in the profession comes support - how we support each other to maintain a diverse, responsive and fair industry which benefits not just practitioners, but also clients.

Of course, this is just a sliver of the work in this field, but I hope it prompts thought, debate and hopefully action in our readers. •

chapter president’s message

Author Philip GriffithsEquity in our profession was sparked by a discussion on gender equity, which rapidly transitioned into workplace equity. Gender was a very important starting point and remains a significant issue, with many young male and female architects looking for flexibility.

The biggest bugbears are pay and opportunity inequalities, together with regaining a place in the profession after significant periods of absence, or the desire for part-time engagement. Parlour and Committee for Perth’s ‘Filling the Pool’ have identified the issues and some pathways towards more equitable and diverse workplace arrangements, and while some large companies are acting on the actions identified, many architecture firms are not. The Male Champions of Change publication ‘Accelerating the Advancement of Women in Leadership; Listening, Learning and Leading’ was also very enlightening.

One of the significant gaps in equity is in child rearing years when many – a lot of women and some men – either leave the workforce or want to play a more significant role in the raising of their children which means that part-time work suits best. There is a perception that this won’t work, but that’s not the case in my own experience. Part-time means being well organised and often means five days of work achieved in less.

Affirmative action on equity issues causes a philosophical divide and is best avoided. A more proactive

engagement where industry leaders adopt an approach aimed squarely at equity might work better. If that does not significantly improve things, some form of affirmative action may be required, but I would hope we can transform practice in a way that avoids quotas. Institute members would do well to apply the 10-point statement of principles on gender equity developed during Paul Berkemeier’s presidency in 20131

Ensuring that our workforce is diverse and provides opportunities for all throughout their careers means a better balance during times when energies are required for parenthood, retention of talent in the industry, and a better prospect of returning to full-time engagement. With changes in technology and workplace mobility, it has never been easier to contemplate and implement a diverse and equitable workplace. Diversity and flexibility make happy workplaces. They change behaviour and create a richer, more considerate environment.

We are also looking at socio-economic access to architecture, a discussion that has been prompted in part by housing affordability and a degree of dissatisfaction with the product delivered by developers. This has led to more group development and bottomup design to get away from standard and often unaffordable options. Kristian Ring recently gave a stimulating Dean’s lecture on the topic based on her practice in Berlin. In this issue some of the alternative options for delivery are explored, including the Nightingale model. This offers the option of exploring how we really want to live and how we might do it in a collective way, with the prospect of developers’ margins being invested in the outcome, rather than being pocketed.

I must finally mention that we have been pursuing and assisting the State Government with the development of a planning policy on apartment standards. Our aim was to have a scheme that sets minimum requirements, design review through skilled panels, and the mandatory use of architects on projects above a threshold. The base model was the New South Wales State Environmental Planning Policy No. 65 (SEPP 65) Design Quality of Residential Apartment Development and much work has been done by all industry players to achieve a robust and useful policy. We look forward to the draft being advertised and trust that you will be supportive. •

gender equity

PERCENTAGE OF REGISTERED ARCHITECTS WHO ARE WOMEN

gender and architecture

Authors Dr Gill Matthewson and Justine ClarkOn gender

First, a few caveats. Talking about gender and architecture is not the same thing as talking about women in architecture. Gender is not a synonym for women: gender-based stereotypes also constrain men, and gender inequity is a societal problem that needs to be addressed by us all. Gender is also not a simple or straightforward binary. That said, a large proportion of the research, resources and discussion about genderbased effects in architecture is about women. This includes our own research and much of the advocacy and activism undertaken by Parlour1. This is because women, as a group, experience more severe career constraints than men as a group. It is important to note that talking about women and men as groups can lead to generalisations that might not chime with our own particular experiences. But by looking at the experiences of groups we can identify structural factors and by attending to career stories other than our own we build empathy and acknowledge a diversity of experiences. So, with those caveats out of the way, what is the situation for women in Australian architecture, how are things changing, and what can we all do to improve things?

Women in Australian architecture

Women have been active participants in Australian architecture for over a hundred years. The numbers of women in architecture grew steadily over the last century, and escalated steeply from the 1990s onwards. Yet all is not rosy. Both statistics and qualitative findings suggest that many women have unequal opportunity in the profession. Despite rising numbers women still lag behind men in every measure of participation, and the rates of women becoming registered architects have not kept pace with increasing graduation rates.

Women have comprised over 40% of architectural graduates in Australia for more than two decades and women are well represented, and active, as student and graduate members of the Australian Institute of Architects2 However, following graduation women start disappearing from professional demographics – they lag significantly in registration statistics and they are under-represented in Institute membership categories available to registered architects. Women are also more likely to be employees than employers, and those who are directors of practices are most often found in smaller practices. There is clear

evidence of gender-based pay gaps, and women comprise a much larger component of the profession’s ‘informal’ workforce: the Census identifies twice as many women working in architecture as there are female registered architects3

All of this points to a gap between education and opportunity which emphasises two things. Firstly, that the absence of women in the profession, and particularly at senior levels, is not a result of too few women studying architecture. Secondly, conditions within the profession constrict and impede women’s careers in architecture. That is, women are slow to progress, or leave altogether, because of structural and cultural factors within architectural workplaces and professional cultures. These factors are complex and intertwined. The structures of the profession are still geared towards the tradition of linear, rising career trajectories. This kind of career is aided by long working hours and social connections that favour men in the male-dominated construction and developer industries. This has a detrimental effect on many women (and some men), regardless of their talent, commitment, expertise and experience.

1 See Parlour: women, equity, architecture http://archiparlour.org/. Research conducted as part of the research project ‘Equity and Diversity in the Australian Architecture Profession: Women, Work, and Leadership’. Led by Dr Naomi Stead (University of Queensland), the team included Justine Clark, Dr Karen Burns and Professor Julie Willis from the University of Melbourne; and Professor Sandra Kaji-O'Grady, Professor Gillian Whitehouse, and Dr Amanda Roan from the University of Queensland. Gill Matthewson undertook doctoral studies associated with the project at the University of Queensland 2011–2015. The research was funded by an Australian Research Council Linkage Grant and included five industry partners, the Australian Institute of Architects, Architecture Media, BVN Architecture, PTW Architects and Bates Smart.

2 Gill Matthewson “Updating the Numbers: At School” http://archiparlour.org/updating-the-numbers-at-school/ ; “Updating the Numbers: Institute membership” http://archiparlour.org/updatingthe-numbers-part-3-institute-membership/

3 Gill Matthewson, “Mind the Gap” http://archiparlour.org/mind-the-gap/; Gill Matthewson and Justine Clark “The Half Life of Women Architects”, http://archiparlour.org/the-half-life-of-womenarchitects/.

Other factors include: relatively low pay rates across the industry, a paucity of meaningful part-time and flexible work options, entrenched long-hours cultures in many practices, and the multiple impacts of implicit gender bias. Of those who leave, some women move into other, related, areas where they do great work and find new opportunity. But others feel forced out and are left disillusioned and dispirited by the structural factors that leave them unable to fulfill their potential in architecture.

The loss of women in a workplace or profession is sometimes explained as a result of women’s ‘choice’, but there are numerous complexities and constraints around the notion of choice4. For example, the argument that women leave architecture firms or the profession ‘by choice’ puts the responsibility on the women in question, rather than seeing the structural issues in the firm or the profession. Choices are made within the complex contexts of both architecture and wider society. These nudge women (and men) one way or another because of gender-based assumed ‘natural’ abilities, behaviours, inclinations, values, psychologies, personalities, and attributes. In actuality, gender is seldom a single contributing factor, and most often

interacts with the complicated economic, political, and social imperatives that control much of the work of the architecture profession. As such, bias due to gender is able to be obscured, and then dismissed, as not existing.

On a more positive note, an enormous amount of work and action over the last few years has greatly increased awareness of the issue, with many people in many places working to transform the profession. In our work, Parlour has pursued a strong advocacy program, and developed tools such as the Parlour Guides to Equitable Practice, which aim to provide practical strategies to help the profession move towards more equitable work practices, and thereby a more robust and inclusive profession. Other groups have formed across the country.

The Institute now has a Gender Equity Policy, a very active National Committee for Gender Equity, and a number of newly formed state-based Gender Equity Taskforce groups, including the NSW one, which has initiated a Male Champions of Change program. There are also statistical indications of change: recent registration figures show a dramatic increase in the numbers of women becoming registered architects5. This recent flourish of activity builds on

decades and decades of activism and advocacy of women (and men) who have gone before us.

Entrenched issues

Regardless of all this work, we still encounter the persistent belief that gender equity has been achieved because promotion, opportunities, and success are merit-based6. This is something of a curiosity: it is the way we think the world should work but all the evidence suggests that it is not the case. Indeed, the very idea of ‘merit’ is highly problematic – Australian National University Professor of law Margaret Thornton simply calls it a mirage7. She argues that any evaluation of someone’s achievements and abilities is made by fallible people who can only ever be a product of their culture and society –one that consistently exhibits gender bias. Indeed, some might argue that gender inequity structures our society.

The mirage of merit hides the structural issues that impact on everyone’s careers, for good or ill, and doesn't prepare architects with the political and social skills they need to navigate a career. This is important because inequity is experienced differently at different career moments, and both advantage and disadvantage build up over time through the accumulation of many small things.

4 Gill Matthewson, “Architecture and the Rhetoric of Choice.” Parlour: women, equity, architecture. October 6, 2013. http://archiparlour.org/architecture-the-rhetoric-of-choice/.

5 Gill Matthewson, “ The Parlour Effect”, http://archiparlour.org/the-parlour-effect/ .

6 Emilio J. Castilla and Stephen Benard, “The Paradox of Meritocracy in Organizations,” Administrative Science Quarterly 55, no. 4 (2010): 543.

7 Margaret Thornton, “The Mirage of Merit: Reconstituting the ‘Ideal Academic’,” Australian Feminist Studies 28, no. 76 (2013). Also Ruth Simpson, Anne Ross-Smith, and Patricia Lewis, “Merit, Special Contribution and Choice,” Gender in Management: An International Journal 25, no. 3 (2010).

Gender bias means that it is more difficult for women to demonstrate competence in a workplace, particularly when they are few in number. Women tend to be judged on their accomplishments, but men on their potential. Virginia Valian cites numerous studies to show that, despite stated beliefs in equality, people tend to underestimate the abilities of women and overestimate those of men8. Although such estimates can be quite small and individually seem insignificant, Valian argues that they add up over time to become decisive, and men’s accumulated advantages result in better opportunities and greater success. Gendered under- and over-estimation of abilities can also be internalised, affecting individual confidence levels, often negatively for women. In addition, gender bias means that the mistakes women make are less easily forgiven or forgotten than the mistakes of men. This is because women are subjected to heightened scrutiny over their performance. Moreover, male success is often attributed to skill, but female success to luck. Finally, the stereotypical expectation that men will be more competent at a particular job –especially those related to construction – affects the even application of ostensibly objective rules. Because of these gender biases, women are required to constantly prove and prove again

their competence. The criteria and tests used to measure and assess merit are unable to be free of both conscious and unconscious bias, and what we think of as merit is far less about ability and experience and far more about connections and political behaviour.

For women to be able to participate to their fullest capacity we need to address these issues. We need to see structural change, to shift what is valued in the profession and how this value is expressed. There also needs to be serious workplace change – particularly to redress the pressing issues of long hours, low pay and the lack of availability of meaningful part-time work. Addressing these problems is essential to the ongoing viability and sustainability of the profession as a whole.

There is also a now well-established ‘business case’ for gender equity, which goes something like this: a more diverse workforce, especially at senior levels, delivers better outcomes for multiple reasons. Diverse voices lead to more creative approaches to problem solving, more robust overall decisions, and better economic performance. A diverse, inclusive culture helps avoid ‘groupthink’, and brings significant gains in retaining staff and reducing ‘churn’9. These findings are relevant

8 Virginia Valian, “Sex, Schemas, and Success: What’s Keeping Women Back?” Academe 84, no. 5 (1998): 54.

to architecture – creative problem solving and better overall decisions are obvious assets in architectural practice – but they are also relevant to the wider profession. The attrition of highly educated and skilled architects who happen to be women diminishes architecture’s potential for change and renewal. If the profession is to adapt effectively to new environments we need more people who think in diverse ways, not fewer.

Architects are trained to question the assumptions that determine the way the built environment is organised and constructed. Greater equity and diversity in the profession broadens the scope of that questioning through a wider range of perspectives and that range also assists with answering those questions. But to achieve this we need to do some questioning ourselves. We need to examine how the profession itself is organised because it currently produces working conditions that specifically exclude women. Addressing the lack of equity and diversity in the profession is clearly a worthy challenge for creative professionals.

Architecture must find new modes of work that will ensure a robust, viable and sustainable future for the profession. •

9 Justine Clark, “Architecture, Gender, Economics”, published in Architecture Australia as “Engendering Architecture” (May 2012) and available online http://archiparlour.org/gender-architectureeconomics/Special Contribution and Choice,” Gender in Management: An International Journal 25, no. 3 (2010).

where are the women?

Author Tanya TrevisanIn 2003 and again in 2015, Tanya Trevisan asked the question: ‘Architecture: Where are the Women?’. Here we re-present her investigations.

ARCHITECTURE:

WHERE ARE THE WOMEN? (2003)

Approximately a year ago at the endof-year barbecue at the University of Technology, Sydney, a trio of female architectural students banded together and asked me what it was like to be in the profession as a female architect. They asked me if among architects in practice, there is gender equality and equal opportunities – What is it like? How disappointing it is to reveal that inequalities exist when the universities to a great extent are sheltered from this fact. Why is it then that the workplace is not? To help answer this I emailed a short questionnaire to many architectural practices throughout the Sydney area. The responses seem to confirm that in 2003 there is still great inequality for women, certainly within the profession of architecture.

The questionnaire

Part One

Q1: How many architects work in your organisation?

Q2: Out of that total how many are women?

Q3: How many architects are in management type positions within your organisation (ie associate, director level, etc)?

Q4: Out of this number, how many are women?

Part Two

Q5: In your opinion, why do women represent such a small percentage of the architectural profession?

Q6: In your opinion, why do women represent such a small percentage of the management structure within professional organisations?

Responses were received from architects within 17 architectural practices. The responses came from people who work in practices of all sizes: from sole-practitioners to large practices that employ more than 50 architects with many practices falling in between these two extremes. The time in which this information has been collated is short and the number of responses is relatively small (24). It is therefore arguable that this may not be representative of the true picture; however for the record these are the results.

Results for Part One

Q1: Total architectural workforce for the 17 practices that responded is 688 architects.

Q2: Total of female architects within these practices is 191.

Q3: Total number of managers (ie associates, directors etc) within these practices is 188.

Q4: Total number of female managers within these practices is 29.

Statistically within the limitations of this model:

male architects make up 72% of the workforce

female architects make up 28% of the workforce managers make up 27% of the total workforce of these managers, female architects represent 15% of these managers, male architects represent 85%.

These figures are at odds with the student female-to-male ratios at the two universities where information was readily available: the Faculty of Architecture at the University of Technology, Sydney and the Faculty of Architecture at the University of New South Wales.

New entry in 2003: 70 female students (41%) and 101 male students (59%). Final graduation in 2002: 61 female students (46%) and 72 male students (54%).

Female architectural graduates from this limited survey represent 46% of the total of students graduating, yet in practice female architects represent 28% of the total within the workplace and only 15% of the total of management within that structure.

Results for Part Two

Interestingly, the answers to the questions within Part Two were reasonably consistent within the female responses and also consistent within the male responses. However, the female and male responses were quite different from each other.

The issues related to caring for a young family, taking time off to have children and making the choice to work part-time came up much more in the male responses to both questions than the female responses, in fact almost exclusively. These issues were acknowledged by the female respondents, however this apparent gender inequality was also attributed to other issues, which were given greater or equal importance. These other issues deemed to be important are: the lack of female role models the perception that women tend not to promote themselves or their particular skills in the same way that men do that most workplaces are dominated by men who have different values from women.

A colleague recently gave me a copy of an article entitled ‘A Glassbreaker's Guide to the Ceiling’ by Myra H Strober, David L Bradford and Jay M Jackman (Stanford University, California, 1992). This article argues that, contrary to popular myth, time alone will not create equality within the workplace. According to their research there are a number of key changes that need to occur sociologically and within the structure of the workplace to allow women to participate as actively as, and equally with, their male counterparts should they choose to do so. The article calls for organisational change and support in order that women have the choice to both fulfil a childbearing role and contribute as an active professional.

The article also cites more than just the traditional childcare role as the cause of this inequality, noting that there is need for change on both sides, within both male and female behavioural patterns which to some extent are perpetuating gender stereotyping.

On a personal note I wish to acknowledge that there are a great number of women in both small and

large practices who are achieving noteworthy results within the practice of architecture; results irrespective of gender. This article does not intend to undermine those achievements, but it does seek to highlight the current situation as it exists. Thank you to all those who responded to the questionnaire.

ARCHITECTURE: WHERE ARE THE WOMEN? REVISITED (2015)

When I wrote the article ‘Architecture: Where are the Women?’ in November 2003, Facebook was still three months away from being invented, the global use of email and the internet was still in its early days, and societies and media interacted in a very different way from today. This last decade has been one of enormous social change led, I believe, by the communication revolution.

I note the rainbow colours on my friends’ profiles sweeping through Facebook almost within a 72-hour period – friends from different phases of my life and unknown to each other, as far removed as Berlin to Sydney, embracing the anti-prejudicial stance

of equal rights to marriage, a stance I need to say that I support fully and unreservedly.

At the same time, the ABC news confirmed women in Australia in 2015 are paid 70% of men’s salaries when compared like for like. Disturbingly the gap has been widening since 2004. This news didn’t even generate a frontpage headline. The Matildas soccer team, ranked 10th globally, go on strike because they are paid 15 times less than their male counterparts. At $21,000 for a full-time job, this is substantially less than the minimum wage in Australia. Oscar-winning US actress Jennifer Lawrence made headlines for taking her industry to task over gender inequality and sexism, a practice made public by the Sony hacking incident in 2014. All this news has emerged in the last two months and has disappeared without controversy or discussion.

In Australia in 2015 more than 60% of law graduates are female yet as things stand, less than 20% will make it to partnership positions. According to 2015 Parlour research, architecture practices have very similar ratios: the majority of architecture graduates are female and

only a tiny minority of those make it to senior directorship level. Imagine for a minute if you changed the headline of the ABC salaries article from ‘women’ to any sort of minority group. What sort of reaction would there be? Yet not one person I know changed their Facebook profile to make a fuss about this or even commented on it. Women in Australia are arguably treated more fairly than in most other countries and we have laws set up to protect every Australian against discrimination of this sort, so what is this about? I don’t understand it. I look at positive discrimination requirements in relation to board representation and I admit I am not totally comfortable with this. I believe that it undermines the real full-value contribution women make irrespective of gender. However, I equally acknowledge the article ‘A Glass breaker’s Guide to the Ceiling’ which argues contrary to popular myth that time alone will not create equality within the workplace – something I frustratingly now believe to be true.

So when Justine Clark of Parlour asked me if she could re-publish ‘Architecture: Where are the Women?’ and if I would write a preamble, I reflected on what has

changed. Twelve years is a long time. Since writing the article, what’s changed for me is that my five-year-old daughter is now approaching her final year of school, full of enthusiasm and huge potential. I am not going to accept that she experiences this sort of prejudice and neither should anyone else. I believe we really need to start making a lot more of a fuss because the low-key approach is simply not working.

‘Architecture: Where are the Women?’ was originally published in Architecture Bulletin (the official journal of the NSW Chapter of the Australian Institute of Architects) in June 2003. ‘Architecture: Where are the Women? Revisited’ was originally published by Parlour in November 2015. •

COMBI-STEAM W/ DOOR KIT

Multifunction oven with steam for professional results

SPEED OVEN W/ DOOR KIT

Conveniently reduces cooking times by up to 30%

60CM THERMOSEAL OVEN The seal of taste

THE BEST THING NEXT TO A SMEG OVEN – IS ANOTHER SMEG OVEN

‘filling the pool’ - an update

Author Marion FulkerThe Committee for Perth’s landmark gender equality report ‘Filling the Pool’ recently celebrated its first anniversary1. Since June last year what has followed could only be described as a phenomenal response. In the months after the report came out you couldn’t go to a meeting on the Terrace without it being discussed. In the year since, I have been kept busy presenting the report’s findings and recommendations roadmap. To date, I have done 67 presentations and, pleasingly, not only here in Perth but also in Geelong and Sydney. It is gratifying that a report that was specifically ‘by Perth, for Perth’, has resonated so strongly at home and also across the Nullabor.

The two year-long research effort was to understand why women in Perth don’t get ahead and therefore don’t occupy enough influencing and decision-making roles. Its qualitative approach placed women at the core of the subject and their stories, provided through 150 interviews, were then checked against the facts. What has resulted is a body of evidence that is irrefutable, with a clear pathway forward, proposed through 31 practical and actionable recommendations in which Government, businesses, leaders and women all have a role to play.

One of the very first organisations that asked for a briefing on ‘Filling the Pool’ was the WA Chapter of the Australian Institute of Architects. If you haven’t read the report here is what you need

to know: getting more women into the workforce and, importantly, progressing their careers has a number of structural barriers and social norms that need to be overcome.

Unfortunately, the trajectory that leads to gender inequality starts in early childhood and continues during the formative years. As parents, it comes from the decisions we make in raising our children and the subjects we guide them to take. It arises from the professions that are deemed acceptable and suitable for one gender over another. It is exacerbated by the emphasis placed on mothering rather than parenting by society as a whole. In essence ‘pink vs blue’ biases exist everywhere.

Women make up 51% of the nation’s population and below is a list of lead indicators that demonstrate the magnitude of gender inequality in Australia:

women take on 97% of the primary care-giving role whether they are working or not women make up 46% of the Australian workforce yet hold only 4% of CEO positions, 16% of directorships and 5% of board chair roles

the gender pay gap continues to increase, going from 14.9% in 2004 to 18.9% in 2014

55% of university graduates are female. In most degree areas 55% of women make up the graduate pool except in the areas of science and

engineering. This has been the case for more than two decades.

Looking at those figures is illuminating. Another gem from our researchers is that at the current glacial rate of change it will take 300 years to have an equal number of men and women in CEO roles. Based on the above, it is fair to say that a woman who graduated some time over the past 30 years who has been able to capitalise on her abilities and forge a career that takes her all the way to the C-Suite and boardroom and who has been also able to balance that with the needs of her family would be rare. I am not sure the same could be said of her male counterparts.

‘Filling the Pool’ deliberately concentrated on the corporate sector, the place where the most change could be effected that would lead to large scale transformation. However, that barriers need to be overcome so that women can take an equal seat at the table is an issue for all parts of our economy and society.

The study found that the four pillars that need to be working in concert so that a woman can successfully return to work are:

spouse support family support external childcare providers flexible employment.

Two of the four pillars relate to individuals and their circumstances, the third to government and the

marketplace and the fourth is where organisations have a role to play. Access to flexible work arrangements, not necessarily less hours or responsibility, is crucial for balancing career and caring.

At the Australian Institute of Architects presentation last year, two primary concerns were raised about moving from a traditional practice environment. I have listed these and offered an update about what is happening more broadly in the Perth business community:

Issue: Offering flexible working arrangements to a woman returning to work will be inequitable for others.

Update: Organisations that are focused on keeping a talented workforce are deploying flexible conditions for all and are gaining a reputation for being employers of choice.

Issue: Client work with deadlines cannot be done flexibly.

Update: All professional service firms face this challenge; however there have been a number which have deployed an

‘all roles flex’ policy even in litigation areas of law firms.

A central recommendation of ‘Filling the Pool’ was to create ‘targets with teeth’ in order to achieve gender equality in each workplace. Here are some good first steps for all organisations, regardless of size: undertake a gender count to understand your workforce composition analyse the gender count to ascertain the number of women and men in all roles within the organisation create strategies to move women through the pipeline where any imbalance occurs undertake a like-for-like pay gap analysis where there is a pay gap for women undertaking the same roles with the same accountabilities as their male counterparts, close the gender pay gap

be accountable and transparent with the results and communicate regularly with your staff.

Critical to the roadmap is the interlocking nature of the recommendations for governmentbusiness-women. Without all parts pulling together with a sense of shared responsibility the desire for a Perth in which men and women have equal opportunity will not be realised.

A lack of action will result in current and future generations of women continuing to squander their education and not fully realise their goals and ambitions. What a shameful underutilisation of female talent, particularly when Perth faces some significant challenges growing to a region of 3.5 million people. This is a time in which we need diversity of thought around the table in order to devise workable, actionable, intergenerational solutions. •

australian institute of architects national committee for gender equity

An interview with Emma WilliamsonCan you describe the purpose of the committee?

The National Committee for Gender Equity was established in 2013 and through a couple of somewhat unexpected twists and turns (read pushes and prods) I found myself on the committee and then as the founding chair.

The mandate for the committee is to enact the Australian Institute of Architects Gender Equity policy, looking at the practices of the Institute itself as well as developing ways to make the profession more equitable. Despite a 50/50 split of men and women entering architecture schools, and a relatively even split of graduates there is an alarming drop in women’s participation in the profession after 30 years of age. This represents a major loss of talent, experience and competency within the profession and the Institute rightly takes this very seriously.

What was your particular stance on the issues of equity in architecture prior to joining? What did you think that you personally could bring to the committee? These are so many cultural constructs that create inequity between men and

women, which are in no way unique to architecture. I see the issue as not just about creating more opportunities for women, but about creating the same opportunities for men and women. This may sound like a subtle difference but it’s a big one. Annabel Crabb’s The Wife Drought captures and articulates this position perfectly. It's easy to refer to the lack of opportunity for women, but how about the pressure on men to maintain full-time work, or the negative bias toward men who seek more flexible arrangements?

In my early career as an academic I had my first taste of the limitations of career progression that resulted from part-time work. Now as a practice owner I feel the complex relationship between time, money and competition that ultimately impacts on the quality of work (trying to do things quickly because there are no fees) and the (un)desirability of the profession for people seeking a balanced life.

Although I was initially resistant to the idea of being part of the committee, I did eventually feel that it was better to put some positive energy into making change rather than observing from the

sidelines. Surely, we could capitalise on the conversations that are happening across the board about equity?

As chair, I set an agenda of combining long term strategic moves with ‘quickwins’ with the idea that these would energise the committee and create an environment of change. We were extremely fortunate to be able to operate in the slipstream of energy and action created by Parlour.

The committee is intentionally made up of men and women from small, medium and large practices as well as academia from all over Australia. This has helped to ensure that we consider the impact of equity from all angles. As a director of a medium sized practice, as an employer and as a working mother I think I have been well placed to contribute to the space that lies between the sole practitioner and the corporate practitioner. I have also learned a great deal from the other committee members and their experience in the profession.

What do you think are the key issues in architecture to do with equity right now? Each time I have made a presentation of the work of the committee I started by

including some of the diagrams that had come out of the detailed and in-depth Parlour research, as a background to our work and approach. Despite the overwhelming evidence, each time I did this it seemed to spark a question and then a debate about why we have this problem, or why we still have this problem, or if it is a problem, or what is the problem or how do we tackle such a big problem.

In practice the question of how we tackle wicked problems can be stifling, yet as architects we are trained to solve complex problems! Whilst the issue of equity is firmly part of the public discourse, it does challenge so many professional norms and can lead to a type of practice paralysis! It's difficult to know where to start, but the committee did take the broad view that if there is a problem and it has been identified then there is also an appetite for change.

Nowhere have the issues around equity and architecture been more succinctly articulated than in the Parlour ‘Guides to Practice’. Broken down into bite size chapters, the guides cover pay equity, the culture of long hours, part-time work, flexibility, recruitment, career

progression, negotiation, career break, leadership, mentoring and registration. Each chapter reveals a depressing truth but amazingly manages to present it in such a pro-active way that one instantly feels empowered to make change.

Unfortunately, it’s difficult to unpack and address one of these issues without revealing more about the state of the profession as a whole. How is it that we have managed to make ourselves so spectacularly undervalued whilst maintaining a culture of long hours? How can we offer so little in the way of contemporary work practices, and take on more and more liability, not only for our work but for the work of our consultants?

I believe a radical shift in the leadership within the profession is required to embrace change and make ourselves relevant again. Doing this requires not only recognition of equity but also diversity. Within the senior ranks of the vast majority of large practices in Australia there are VERY few women. In fact, they are largely made up of white men.

Study after study shows that we tend to employ people in the image of ourselves. This human tendency toward an unconscious bias means that there is little on the horizon in terms of real leadership shifts without some serious policies being put in place by practices. Proposing such a change requires courage and executing it is even more challenging – but I think it can be done! I would like to see more practices taking this on board and seeing the effect of having more women in leadership positions. These women would need to be supported in their roles and allowed to contribute to a shift in what we see as the cultural norms in architecture. I believe this top down approach will help to create better pathways for both women and men. To do this we need to reimagine a professional life that is more flexible, that repositions itself in a way that can communicate the value in the work that we do.

The thing that I love about architecture is the challenge and the opportunity of problem solving. There are so many complex, layered and unique challenges in each project. In designing a building we have to ensure it stays relevant for many, many decades. It's these skills

in imagining a future that need to be brought into play to re-think practice.

How effective do you think the various initiatives of the committee have been so far?

I feel very proud of the work of the committee and feel that the conversation around equity has made a dramatic shift in the past three years. The Institute has been very supportive of our recommendations and, at a time of contraction, realised the importance of a partnership with Parlour in order to reach out to non-members and to demonstrate its work in this area. It is important to note that Parlour is completely independent of the Institute and the NGEC. The work of Parlour has been so influential in our thinking and approach. The initial research project demonstrated compelling evidence of the need for change within our profession and we respect the significant groundwork that led to the formation of the committee. I am so pleased that as a committee we have managed to establish and maintain a strong working relationship with Parlour, and that we are able to use the Parlour website as a major communication channel to reach out to members and non-members.

We have established The Paula Whitman Prize for Leadership in Gender Equity which was launched this year. We have started a range of communications initiatives that look to raise the profile of women within the profession and outside; in part, we recognise that this has allowed us an opportunity to broaden the definition of an architect.

Significantly, we successfully lobbied for a mandatory 30% representation by men and women on the new Board of Directors of the Institute.

Although we cannot take credit for it, we were extremely pleased to see the appointment of a female CEO this year.

What do you imagine should be the ongoing priorities for the committee in the future?

The role of the committee is strategic and we will continue to raise the profile of women and push for equity. Our priority is to help more women become leaders, to keep mid-career women engaged and valued and to help changes in practice culture that will keep more women contributing to the built environment.

We also have a mandate to keep checking in on the equity of the Institute and this lens is being applied to every aspect of Institute operations from its own employment policies to the equitable representation of men and women in CPD events and to the composition of award juries.

The committee reports directly to the National Council but we are also uniquely positioned to connect with each chapter. Now that we have a few big runs on the board I think it is time for us to combine these bigger picture moves with what’s happening locally. Our ambition is to have more women who are visible in architecture and to help women find a workable solution for their mid-career. Every little thing helps. •

A lot of commentary surrounding gender equity in architecture, as with other professions associated with long hours, points towards flexible working arrangements as a strategy to support working parents and redress the disappearance of women from the workforce at this stage, resulting in inequities in pay and underrepresentation in senior roles. Here we present reflections on two examples of flexible, family-friendly working arrangements: experience in working in architecture in Norway, and arrangements established in a Perth law firm.

BEKK CROMBIE

Architecture in Norway

Could you please paint a picture of the typical working week you experienced in Norway? As far as you know, does this apply to all office-based professions (including architecture)?

The typical working day was from 8am to 4pm and this is the national average across all disciplines in both the private and public sector. Flexi-time is standard. My colleagues rarely worked overtime and this was discouraged. The directors would rather hear about your evening stroll through a national park than how you worked all evening (at a 25% productivity rate).

Working in architecture is often associated with heavy workloads and project-driven deadlines resulting in long hours and overtime. How were these pressures addressed in the firm you worked for and a typical Norwegian office?

There is an enormous focus on resource management and open lines of communication. In weekly staff

the hours

meetings the directors and the executive assistant ran through every project and quickly addressed any issues the project teams were having. Being honest and outspoken was encouraged and as a result we all knew what was going on and were able to play off each other’s strengths and weaknesses. There was very little ego or bravado, just a workforce driven to all get the job done together. Projects always ran on time.

Could you please describe your working week, including coordinating out-of-work commitments - such as childcare? How did the working environment in Norway facilitate or support this?

Oh my goodness, this was so easy!

The local barnehage (kindergarten) opened from 7am to 4:30pm which aligns with the standard working day allowing parents to easily coordinate pick-ups and drop offs between themselves, or even manage it solely. Pretty much every Norwegian child attends staterun and subsidised barnehagen from the age of one until school age. There is no stigma, no guilt associated with dumping your kids at these Montessoriesque wonderlands. And, compared to Australia, it’s really affordable!

What do you think are the major benefits of the working environment you experienced?

The money that the Norwegian government invests in providing job security for working mothers through paid maternity (and paternity) leave (one whole year!) and subsidised childcare is offset by the increase in GDP these working mothers (and fathers) contribute by returning to fulltime work within a year or so. It helps to uphold a happy, healthy and skilled workforce which is good for everybody.

Reflecting on the general work environment in Australia, and particularly in industries typically associated with long hours - such as architecture or law, where do you feel the major differences lie?

All industries in Norway enjoy these conditions and so there is really no need to stay at work much later than 4pm. The directors, QS, builder, project manager, engineers and client are all sitting at home eating dinner by 4:30. And the major difference is of course that what is underpinning this societal norm is a massive state funding allocation (and high taxes!).

What lessons, if any, have you been able to apply to your own attitude to work-life balance, or would you like to pass on to others?

I took work-life balance for granted in Norway. It was passive; a societal norm. Back in Australia I have to ensure that I am fulfilled and focused at work which in turn enables me to be relaxed and able to focus on my loved ones outside work hours.

Where do you think major changes are required in our industry to support worklife balance, families or flexible working arrangements?

A defining memory from my first day of uni was stepping into my design studio and counting five mattresses propped against the wall. Long hours are par for the architecture course and the real life workplace is no different. I believe attentive resource management and good communication is key to running an efficient, happy and healthy workforce. A little groundwork goes a very long way.

What aspect of the working environment you experienced in Norway did you appreciate the most?

Not feeling guilty at home or at work. My circumstance, as a mother of two young children under the age of five, wasn’t extraordinary or a hindrance because everybody (married, single, new parent, grandparent etc) enjoyed the same workplace entitlements. I was in a supportive, nurturing, compassionate place at work and, in turn, I was able to be a lovely, nurturing and compassionate mummy at home.

Bekk Crombie is a Graduate of Architecture working at Taylor Robinson.

CATRIONA MACLEOD

Cullen Macleod

Could you please provide an overview of the flexible working arrangements at Cullen Macleod?

We have 25 staff (including the two director-owners) and only 11 of them work traditional hours (8.30am to 5pm, five days per week). So 14 out of 25, or just under 60%, and across all areas from practice manager to solicitors to support staff, are on flexible work hours. That gets even broader when taking into account staff taking extended leave. The flexibility includes: people working anything from three days a week to working a nine-day fortnight, early start and finish times to enable family friendly hours, and hours that change at various times in the year to enable staff to study or teach. We also have flexibility of place as well as time: working from elsewhere, not in the office. Although, this is more relevant to the solicitors as the support staff usually assist several people and need to be physically available to them.

What is the philosophy behind taking this approach?

It is less a philosophy and more just a practical reflection of the world that we all live in. In this day and age the workforce, and the potential workforce that is out there, are made up of people of all ages, from all backgrounds, with a whole variety of different lives. Offering flexibility in working arrangements means we can accommodate all of these differences, recognise that people have lives outside work, and offer working hours that enable them to successfully combine a life and a job. Ultimately employees (and owners of businesses!) are people who (mostly!) work in order to be able to have happy, fulfilled lives with their family and friends. That includes seeing those family and friends and having the time to do things with them. Dependant on the individual, this can mean starting and finishing early in order to see their young child before bedtime, going on extended travel overseas, or just having a nine-day fortnight which means every second weekend is a long weekend. All of the options are basically about quality of life. I strongly believe that, as simple as it sounds, we work to live, not live to work.

Law is an industry associated with long hours. How did Cullen Macleod engineer this shift? Are there any particular measures you have had to put in place or new practices you had to introduce? For us there was no ‘shift’. As our firm started as a brand new company, we could start as we meant to go on without any previous perceptions or mandates about the way things ‘should’ be done or ‘have always’ been done. The three founding owners all had lives, young families and outside interests. Therefore they were always keen to work

efficiently whilst in the office and then go home. There was never the culture that dominates some large firms where doing long hours was seen as a badge of honour. That said, the owners also made a very specific economic decision which continues to this day that enabled that to occur. Law firms are largely based on a solicitor doing a certain amount of ‘billable’ hours per day. The standard is from 6 to 7.5 per day, which will require anything from 10 to 14 hours in the office per day, sometimes more. Cullen Macleod only ask their solicitors to do five hours billable work. This results in a lower profit level in the business, but far more sustainable and honest work practices, and allows staff to work normal work hours, which is healthy for the employees, good for the clients, and ensures long term sustainability for the business.

In implementing flexible working arrangements, how do you manage clients' and employees' expectations?

There are two aspects to this: employee and client. I will deal with employee first, which is also directly linked with employer expectations. This has been a difficult one, and an ever-learning curve. It was much easier when we were much smaller, for example when we only had five to ten staff. That needed very little ‘overseeing’ or ‘policy’ because it was easy to see when it was working, or not. And generally it did work. It has become more difficult with 25 people and such an array of different working hours. With more people, more administrative time and parameters are needed to make it work. We are currently working on this drafting an internal policy to set out expectations and understanding between employees and the business. But generally the philosophy is the same: the employees

are expected to look after their clients and manage their workload, we trust them to do that, and they have always achieved that outcome.

Regarding clients’ expectations, my experience is that as long as clients are secure that their work is being looked after by the right person, will be carried out on time, and will be done to the standard required, they are happy. We have clients from small businesses to ASX listed national companies. Overall, my experience is that they care less (often if at all) about the where, when and how, and more about the outcome achieved. Get the outcome right and the process in getting there is largely a moot point.

How do you think flexible working arrangements benefit your firm, your employees, and your clients? Ultimately it results in a far better overall service to the clients, and that is the core of any business. This is because the work is carried out by people who are happy to be at work, are refreshed and are focused. People who have balanced lives, including flexible work practices, stay in the business longer so we get the benefit of their extended learning and experience, they make better decisions, and because they are more content, they work better together as a team. The clients get the benefits of a long-term team of people with combined skills and experience, who really want to be at work and who really want to be working on their matter. This benefits the employees almost for the same reasons: they have a much better time when they are at work, they are more refreshed and focused when they are here, and they simply enjoy work more. People who enjoy what they do are also always better

at what they do. How all of that then benefits our business is simple: happy successful employees = happy successful clients = a successful business!

On the practical level we have one of lowest staff turnovers of any law firm I know, which has economic benefits to us and the direct benefit of offering a high level of skill and experience to our clients. This also has a strong impact on attracting and retaining top level people to come to, and stay with, our business. The flexible work arrangements have been a significant factor in retaining our key staff and attracting the kind of people we want to come and work with us, whether they are parents with children or 20-somethings who want to travel the world, or anything in between.

What are the major differences you have observed by employing this approach? This is probably answered by the above answers? One difference is that we attract a diverse range of people: from parents, to young people, to people whose families are grown up and gone. The diverse range of experiences and skills that this brings together under one roof makes Cullen Macleod an interesting place to work and provides a better service to our clients. Compared to other law firms where flexibility is either only offered to very senior people, or perhaps more of a ‘lip-service’, I have noticed that there can often be a more ‘generic’ workforce than in our business. I believe that being able to view any transaction or problem from a variety of perspectives enables a better outcome. Having flexible work arrangements attracts (and keeps) diverse people, and diversity of people enables that diversity of perspectives. In the last few years this has also clearly been a major

factor in attracting top level lawyers to our business. Seven out of nine of the solicitors who have approached us in the last 18 months seeking consideration to join our firm have stated that our work culture, including flexible working arrangements, has been a factor in their choice. This ties in to retention: many law firms I know who insist on strict adherence to traditional working models and long hours are losing their staff, from junior level to senior practitioners, who see no benefit in it and are moving out of top tier firms to smaller boutique firms to have that true work-life balance. We are seeing the benefit of this as they approach us to work here! Similarly, our staff appreciate the way that flexibility enables them to live their out-of-work lives and are staying with us.

'Flexible working hours' is often posited as a strategy to address issues of gender equity and career development. Are there any other approaches you feel should be considered?

Absolutely. Flexible work practices are critical to dealing with gender equity. Only when we make allowances for the fact that people have a broad variety of lives, backgrounds and needs can we then start moving towards meaningful workplace equality. Diversity is now globally acknowledged as bringing benefits to the workplace and business success - from diversity on boards, to government, to employees. The only true way to guarantee that diversity is to cater to the needs of the manyvaried employee of today, which may be enabling school drop-offs and varied hours so mums (still usually the primary caregiver) do not have to choose between being a parent or having a job. Keeping those parents (male or female) in the workplace is critical to gender

equity, and also to career development. For lawyers (and most professionals) to develop their careers, they need to go ‘above and beyond’ their daily obligations, such as (primarily) bringing in clients, speaking at seminars, building a profile. We need to work out ways to assist with that. Flexible working arrangements are just one aspect.

Other approaches I believe that are needed include changing the way people carry out business development, hence building and progressing their careers. Too often this is based around some kind of after work function that usually includes drinking. This is simply not an option (or a very difficult and limited one) for many working parents, and especially working mums who more often than not have a partner who is full-time, so by default they are the parttime/flexible parent who deals with the majority of the child care. This approach advantages the full-time working male, or the junior male or female lawyer who, as yet, has no major commitments requiring them to be at home by 4pm. We need to entirely change the way we think of business development and networking events to include ways that are friendly to the part-time parent. Otherwise they often drop out of the workforce or their careers are impacted by their inability to attend events and bring in new business and develop new contacts. A great example I saw of this recently is an initiative by a Perth lawyer, Kimberley Morrison, who started up a ‘Netwalking’ lunchtime group so people can combine exercise with networking at lunchtime. A brilliant idea. And a great example of the new approach that we need.

One of the aspects that is relevant in any discussion of flexible working arrangements is the challenges to the businesses using them. The benefits are quite clear; the challenges need to be worked through. The difficulty is in persuading more ‘traditional’ business owners that the benefits merit these challenges. I have no doubt that this is the case - we just need to think laterally, because we really have no choice. If we want to attract and keep good people, provide that diversity to clients, and obtain the benefits of that diversity, this is just a factor of running a business in the 21st century.

The main challenge for a business for offering flexible working arrangements is that it takes more time within the business to organise flexible staff hours and this can be seen as having an immediate negative effect on profitability and income generation. This is why it is critical to think longterm and realise that these changes are just the way the world is, and to obtain all the benefits, businesses need to rise to the challenge and realise this has a long term benefit to the employee, the client, and ultimately therefore the business.

The extra administrative time ranges from ensuring the right staff are available at the right time and coordinating who is working when, to payroll time in administering flexible times, to issues with office space.

For example, a business runs on return on investment. If we view the investment as the costs in providing the income (salary, cost of office space, associated operating costs etc), then if a solicitor only works three days per week but takes up a five-day-per-week

office, that space is only returning 60% of the ‘output’ a full-time five-dayper-week person would return on that office. Small businesses particularly face more difficulties in being able to deal with these types of issues. For example: a small law firm with ten solicitors, three of whom are part-time (three days per week) each with their own office. These employees would then collectively be generating output equivalent of 1.8 solicitors (three employees at 60% output), while taking up the income generating office space of three solicitors who would otherwise work full-time and produce the output of three solicitors. One option that we are looking at with two prospective new employees who are both part-time working mums and who both would work probably three days per week is to share an office and have one of the solicitors work one day per week from home, which she would like to do and would assist with the office space issue.

These kinds of issues, and solutions, require lateral thinking and innovative solutions. In my opinion they are required in order to gain all the benefits outlined: from diversity in staff, to long term staff retention, to ultimately, benefits to the clients. If staff and clients are the most important aspect of any business, working out what benefits both makes good business sense. Flexible working arrangements are at the core of that.

Catriona Macleod is a Director and co-founder of Cullen Macleod. •

socio-economic access

are we out of touch? or out of time?

a challenge of relevance

Author Kieran WongIn Perth I think the great challenge of our time is the growth of our city, and how to make it more inclusive, denser through better designed infill and with higher community amenity. This is a vital and urgent conversation that architects need to be part of. So why are we struggling to get an influential seat at the table? How can our profession maintain its relevance, its credibility and be responsive to the changing needs of society? How can we influence the future of our cities?

I truly believe that design thinking and our skills as architects are an essential part of the mix in working on the complex problems that we face as a society. This includes the increasingly important challenge around infill and the densification of our city, but our experience at the front line reveals both community unease and a general ambivalence towards our profession.

When I speak to other architects there is a sense of frustration in the system (beyond the usual craziness of the ‘Utopia’ TV show antics of working with any bureaucracy) about how our voices, our skills and our ability to synthesise, intuit and respond to the complex problems of our cities are ignored. Much has been written about this and the hand-wringing is often prefigured by a nostalgic gaze, but we need to build a positive relationship with the future of our profession and its ability to be useful, generous and (if needed) stealthy.

A few years ago I attended ‘Transform: Altering the Future of Architecture’, an amazing pre-conference event for

the national Australian Institute of Architects conference in Melbourne. Organised by Parlour, the discussions and the presentations were amongst the best I’ve seen at a conference of architects. One comment in particular stuck in my mind, confirming some of my long held suspicions. Karen Burns, Parlour co-founder, academic and researcher summarised the findings of the Parlour research, outlining the shocking disparity and inequity of our profession along gender lines. But at the end of a compelling slideshow, describing the equity challenge of women in senior roles, the long working hours culture, the lack of flexibility, the cliff of motherhood, and its disproportionate impact upon working women in the profession, she said (and I paraphrase): ‘after all this research, and a career of looking at this problem as a feminist, I’ve started to think that this is less a problem of gender, and more a problem of class.’

Architecture as a profession is most certainly inequitable along lines of gender. The proportion of women in senior (equity-principal or director) positions in Australian practices is tiny. But the challenge of diversity, of equitable representation in our profession, is broad. On so many levels we are failing to represent the communities we serve and it is possible that this is challenging our relevance.

A couple of years ago, Emma and I taught a design studio for Masters of Architecture students looking at the possible growth and infill of Perth transport corridors. These corridors

are spread across the breadth of metropolitan Perth and previously identified as growth corridors by a joint project of The Greens and the Australian Urban Design Research Centre. The students were asked to research a corridor each with a view to selecting a key site along its length. In our first session I asked the students to place a pin where they lived on a large map of Perth. There was a tight cluster of pins in the western suburbs, one in Fremantle and one in Scarborough. Interestingly each student chose a site at the closest point to the CBD or western suburbs that their corridor would allow. No one chose a fringe suburb or a site on the outskirts. Was it that it was not relevant to them, or do such flat suburban landscapes offer little in the way of architectural heroics?

I was reminded of Karen Hitchcock’s memorable piece in The Monthly on medical students: