REDEFINING CONTEMPORARY

NEW LINEA COLLECTION IN NEPTUNE GREY

Our range of appliances in Neptune grey is unmatched with a new shade of grey, deep and opaque, together with Galileo multicooking technology redefines culinary experience with contemporary style. Also available in Black.

FOREWORD

04

Adam Haddow RAIA

EDITORIAL

07

Matida Gollan RAIA David Welsh RAIA

R ESILIENCE IN THE FACE OF CLI m ATE , FIRE , AND FLOOD

10

Coastal Resilience

Words: Nicole Larkin

14

Resilience in Western Sydney and Wianamatta

Words: Scott Davies Aff. RAIA

18

Brisbane flood-resilient ferry terminal Review: Jamileh Jahangiri RAIA

20

Do no harm

Interview: Claire Mccaughan RAIA with Lachlan Delaney of Sago Collective

24

Architects Assist

Interview: Elise Honeyman RAIA with Jiri Lev

28

Building more resilient infrastructure

Words: Alexa McAuley

ARCHITECTURE BULLETIN

VOL 80 / NO 1 / 2023

Official journal of the NSW Chapter of the Australian Institute of Architects since 1944.

The Australian Institute of Architects acknowledges First Nations peoples as the Traditional Custodians of the lands, waters, and skies of the continent now called Australia. We express our gratitude to their Elders and Knowledge Holders whose wisdom, actions and knowledge have kept culture alive. We recognise First Nations peoples as the first architects and builders. We appreciate their continuing work on Country from pre-invasion times to contemporary First Nations architects, and respect their rights to continue to care for Country.

32

Creating climate-ready environments

Words: Carol Marra

34

Sandbags and seawalls: Designing a different adaptation future

Words: Kate Rintoul

38

Resilience and heritage

Words: Jennifer Preston FRAIA

40

Resilience, health and equity

Words: Andy Marlow RAIA

44

An architect on the ground after the Lismore floods

Words: John de Manincor RAIA

46

What does climate adaptation mean for design, architecture, and building?

Words: Elizabeth Mossop

48

Energy efficiency, bushfire and budget: Where are the overlapping wins?

Words: Sarah Lebner RAIA

50

Disruption, regeneration and our socio-ecological systems

Words: Mark Gazy

54

Bushfires, pandemic, floods

Words: Gerard Reinmuth FRAIA with Andrew Benjamin

56

A red tin shack: Scale Architecture

Words: Matt Chan RAIA and Georgia Forbes-Smith

60

Healthy placemaking partnerships in South Western Sydney

Words: Scott Sidhom and Jennie Pry

64

Net-zero ready for Sydney: Innovating policies and buildings in a climate crisis

Words: HY William Chan RAIA

68 Leave no-one behind in 2023

Words: Anna Rubbo LFRAIA

2023 N SW ARCHITECTURE AWARDS

70

Awards and commendations

OBITUARIES

91 Vale Peter Myers

93 Vale Peter Neil Muller AO FRAIA

People often ask me why I nominated for Chapter President. A simple question but with so many layers. As an introduction to you, I thought I’d offer a short explanation.

Growing up in a rural town, so much attention was given to the city that the regions often felt forgotten. Regional development needs to capture what the regions are about, not simply replicate the city from which the development flows. Housing affordability is the biggest challenge in ensuring we have access to basic services and retain our talent. Looking back, the reason we couldn’t get services was mostly because of a lack of housing options. Not only was there only one type of housing – a house on a block, but there was also little of it, and most of it poorly conceived. There were no apartments, no terrace houses, and the only form of retirement was the place you went to die. Great cities need a wide range of housing types across all economic bands – free to market, affordable and social housing. Housing that meets the needs of the community – in all its forms.

My upbringing also taught me inherent sustainability. We had to do more with less. There was no department store or Bunnings. A quick trip to pick up something could be a three-hour roundtrip to the next town. My memories of youth are punctured with making things out of something else, something close, something that someone else no longer needed – making do by stretching out the life of the thing we needed to keep working. We recycled and reused; replacement was not a word we knew. Good learning for where

we find ourselves now. We are a remote continent with remote cities. We need to think locally and be determined to do more with less. To use local resources from our doorstep rather than fly/ship/buy them in. As a profession we will be most successful if our focus is about lengthening the lives of buildings: adapting, reusing, re-imagining, rather than starting again.

It’s these three things that I would like to address during my time as Chapter President; growth and support for the regions, housing and sustainability. We cannot live in a safe, equitable and fair society without addressing these issues. As an institute we can lead the way. I look forward to working with you all to ensure that the built environment and the Institute itself are more resilient.

This edition also showcases the NSW Architecture Awards, which offers the collective opportunity to see what we’ve delivered; first through a critical lens, then through one of appreciation. Every team on a nominated project deserves praise for their contribution; our city is the sum of its parts and together we are an incredible force. Thank you to everyone involved in the awards program this year. Our convivial and collaborative culture is made from these moments of exchange, and we owe thanks and praise to the Institute for continuing to cultivate that. ■

Adam Haddow RAIA NSW Chapter PresidentEDITORIAL DIRECTOR

Emma Adams

EDITORIAL COMMITTEE

Matilda Gollan (Co-chair)

David Welsh (Co-chair)

Cate Cowlishaw

Nathan Etherington

Sarah Lawlor

Kieran McInerney

CREATIVE DIRECTION

Felicity McDonald

DESIGNER

Andrew Miller

SUBSCRIPTIONS

nsw@architecture.com.au

+61 2 9246 4055

PUBLISHER

Australian Institute of Architects NSW Chapter 3 Manning Street Potts Point, Sydney NSW 2011

COVER IMAGE:

Aija’s Place by Curious Practice. 2023 Newcastle Awards sustainable and residential category winner. Commendation in the 2023 NSW Architecture Awards. Photo: Alex McIntyre.

ADVERTISE WITH US

Contact Joel Roberts: joel.roberts@architecture.com.au

PRINTER Printgraphics

REPLY

Send feedback to bulletin@architecture.com.au. We also invite members to contribute articles and reviews. We reserve the right to edit responses and contributions.

ISSN 0729 08714 Architecture Bulletin is the official journal of the Australian Institute of Architects, NSW Chapter (ACN 000 023 012). © Copyright 2023. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form without the written permission of the publisher, unless for research or review. Copyright of text/images belong to their authors.

DISCLAIMER

The views and opinions expressed in articles and letters published in Architecture Bulletin are the personal views and opinions of the authors of these writings and do not necessarily represent the views and opinions of the Institute and its staff. Material contained in this publication is general comment and is not intended as advice on any particular matter. No reader should act or fail to act on the basis of any material herein. Readers should consult professional advisers.

The Australian Institute of Architects NSW Chapter, its staff, editors, editorial committee and authors expressly disclaim all liability to any persons in respect of acts or omissions by any such person in reliance on any of the contents of this publication.

WARRANTY

Persons and/or organisations and their servants and agents or assigns upon lodging with the publisher for publication or authorising or approving the publication of any advertising material indemnify the publisher, the editor, its servants and agents against all liability for, and costs of, any claims or proceedings whatsoever arising from such publication. Persons and/or organisations and their servants and agents and assigns warrant that the advertising material lodged, authorised or approved for publication complies with all relevant laws and regulations and that its publication will not give rise to any rights or liabilities against the publisher, the editor, or its servants and agents under common and/ or statute law and without limiting the generality of the foregoing further warrant that nothing in the material is misleading or deceptive or otherwise in breach of the Trade Practices Act 1974.

AUSTRALIAN ARCHITECTURE CONFERENCE

Reflect on what has come before, focus on how we face the future and shape what is yet to come. Register today at architecture.com.au/conference

As architects look for ways in which to reduce the impacts of our built environment, we must also prepare for the inevitability of a changing climate. In Australia, drought, flooding, extreme weather events and bushfires have all presented as threats and they are likely to do so in the future.

The callout for this edition was originally “Resilience in the face of natural disaster” very quickly it became clear that the idea of resilience when applied to architecture encompasses more than how we as a profession cope with the effects of climate change.

Contemplating the resilience of our built environment has become a critical design driver from concept to completion, affecting the form, engineering, material choices and siting of any project. There are many facets to designing for resilience, including capacity of a structure to adapt to an altered environment or withstand extreme weather events; but also, to support community resilience in the face and aftermath of such events.

Resilience as a virtue, value or aspiration is a word applied to many situations, circumstances and activities. Like the concept of sustainability, it could quickly become meaningless – perhaps due to the breadth of what these terms seek to describe – yet at their core both set out to describe a range of urgent situations that talk about the wellbeing of humanity, and the delicate environment in which we exist that we have pushed to its limits.

It is often designers working in rural areas who are faced with the task of designing for the effects of a changing climate, many of whose stories are featured in this edition. In this issue we explore lessons learned from rebuilding after recent fire and flood events in NSW. We also hear from thought leaders who advocate for designing more resilient structures which can withstand and adapt to our changing environment. Built examples from here and overseas are explored, as are teaching and research practices at our universities where architecture is taught. Coastal resilience, infrastructure resilience and healthy placemaking are all discussed, along with the importance of how Designing with Country methodologies offer important insights that by their nature can build resilience into our built environment.

While difficult to define under a single descriptive umbrella, we can glean from the breadth of articles in this issue is that considering resilience as an approach rather than through discrete initiatives might be the most successful strategy in creating a truly resilient built environment. It’s an incredibly difficult and diverse subject matter, yet it’s essential to what we do, and will sit at the core of what we as architects need to consider for our foreseeable future. ■

Matilda Gollan RAIA, David Welsh RAIA Editorial Committee Co-chairsRESILIENCE

Coastal resilience

WORDS: NICOLE LARKINThe coast is an iconic and highly-valued landscape in Australia. It’s one of our most productive and abundant places environmentally, culturally and economically. For millennia, the coast has been a place of continuous use and habitation. We are a nation of coastal dwellers with 85% of the population living within 50km of the ocean. If our surroundings speak of who we are, this tells of our love affair with the water’s edge.

In 2016 the Federal Government published a revision of the State of the Environment Report which flagged that we are currently at risk of “loving the coast to death”. Multiple competing factors which converge on the coast place

enormous pressure on the landscape, both natural and built. To add to this, climate change and sea level rise have begun to take hold along our foreshores putting further pressure on the coast.

Coastal resilience is about as complex a problem as they come. Our beaches and foreshores draw a significant level of scrutiny as public open spaces. At odds with this, private waterfront properties represent the highest value real estate in Australia. Together these factors often drive a socio-political divide between local communities. The coast is also a place of legacy issues. Where once it may have been acceptable to build on the foreshore, we have realised this

landscape is fragile, abundant in biodiversity and subject to significant cyclical changes. The coast is incredibly dynamic and is now under significant pressure due to climate change as seen in the aftermath of recent damaging east coast lows.

Ultimately, we can’t hold back the tide along our coast or retreat landward into already densely developed areas perched along the water’s edge. In addition to this, is the complex balance between protection and our community values. Increasingly we seek to conserve the coast in its current state, which is a positive step for environmental values but can also be at odds with necessary adaptation measures.

We understand what it means to protect and conserve the natural beauty of the coast in its current form. We understand less about what coastal adaptation and future proofing might look like. Increasingly, we find that where our relationship to the coast has failed is where we have seen it as a hard line instead of a zone.

The construction of a seawall at Collaroy in Sydney’s Northern Beaches has been at the centre of this debate in NSW and is an example of one approach to coastal hazards. This hardengineered response illustrates the complex challenges communities are grappling with when future proofing the foreshore. Approved under a development application by the Northern Beaches Council, the seawall protects private, water-front properties which back onto the beach. The rear yard for each property is level, resulting in an approximately 8m vertical seawall to the sand below. Since construction of the wall, east coast lows and wave action have periodically scoured sand from the base of the wall including the footings below. The outcome of the wall has been a diminished beachfront, impacts on the surf zone and, at times, restricted public foreshore access. It demonstrates the risks of engineered hard boundaries which protect built structure (private or otherwise) at the cost of diminished public amenity and the natural character of coastal landscapes.

As a built outcome, it lays bare a gap in NSW’s current coastal planning controls. As such, these controls are poised to benefit from an integrated, mutual-by-design approach for coastal infrastructure. This would place a positive duty on coastal development to deliver outcomes for both the built environment and the natural coastal environment. What this looks like in broad terms is still emerging across the world as we grapple with sea level rise and the impacts of climate change.

WORDS: NICOLE LARKIN

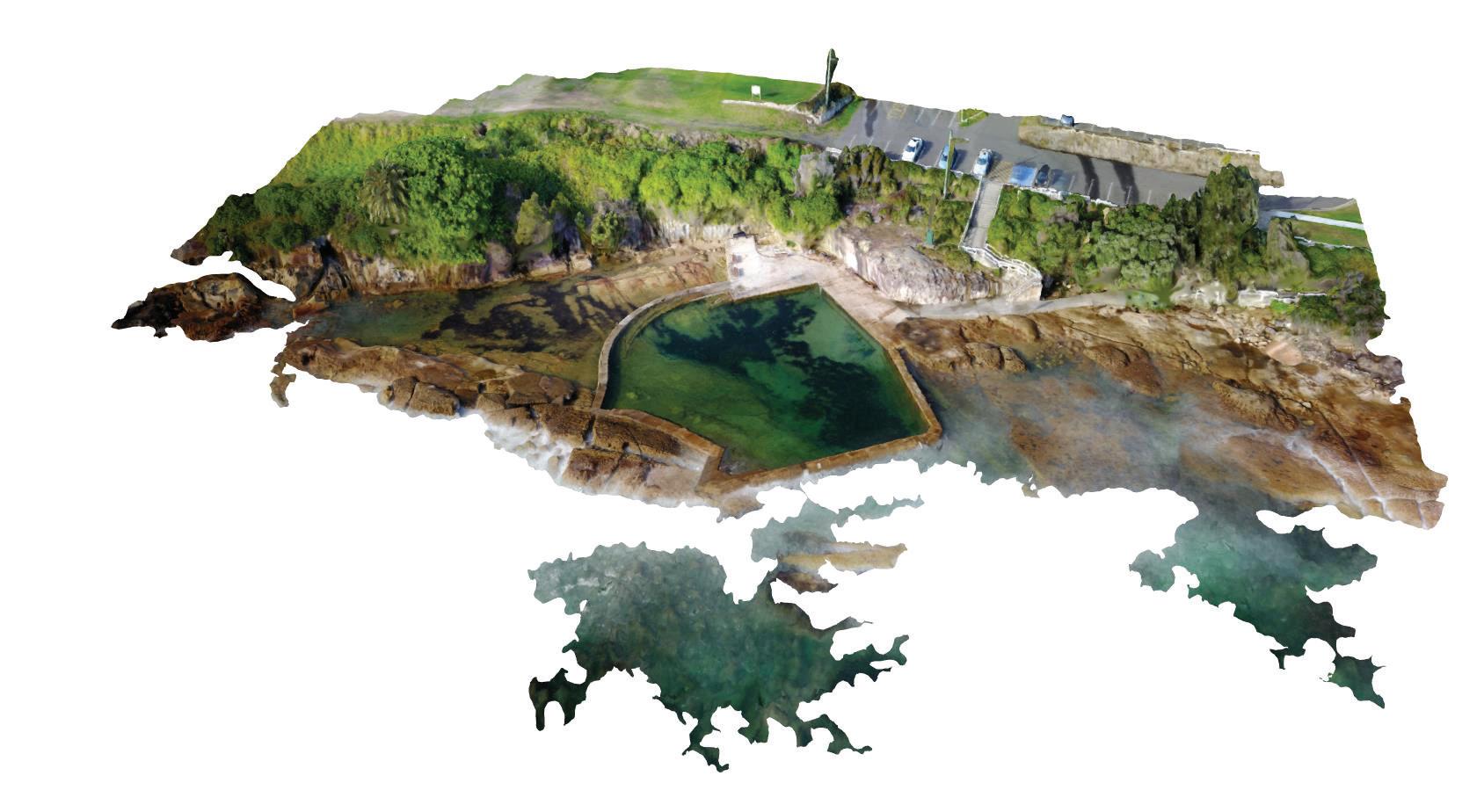

However, in Australia this is not a novel concept. In fact, a commonplace yet iconic example of this can be found among our extensive collection of tidal pools, particularly in NSW. While tidal pools are not strictly defensive structures (although they have the capacity to do so), they illustrate the potential of this approach. Central to this is an aesthetic which does not dimmish the natural landscape. Tidal pools reflect this and are distinctly of their place in Australia as a result.

Nationally we have over 120 ocean and harbour pools, many built in the interwar years as public works projects. They are paired back, introducing structure only as necessary to create a swimming enclosure within a rock platform. Their robust but simple character is secondary to the innate natural beauty of the coast and is distinctly separate from the aesthetic of a municipal pool. Functionally, they are free, public assets that improve access to the coast. They provide protected ocean and harbour swimming for the community, including cohorts who may be less confident in open waters such as young children or older swimmers. The pools by necessity don’t impede natural coastal processes, even filling with sand on occasion only to be drained, dug out and restored to regular use by local councils. They serve as hosts for marine life and are an extension of intertidal habitats which gravitate to natural rock platforms. Tidal pools are integrated with coastal

ecologies while enhancing amenity, access and safety for beach goers. As a group they illustrate one example of how we can manage, site and design foreshore structures to protect and mutually enhance the coast.

As a framework, these unique structures are one example of the potential for a contemporary approach to coastal resilience in NSW. Coastal planning policy (at state and local levels) is poised to address this by providing controls and guidance on desirable built and landscape outcomes, particularly as infrastructure and urban areas are upgraded to adapt to climate change. This is a continually evolving part of our coastal planning framework. If it is to reach its potential, it can serve to ensure our beaches and foreshores are resilient public landscapes which maintain the character of a world-class coastline now and into the future. ■

Byera Hadley, WildEdge. Digital.Nicole Larkin is an architect currently based in the Illawarra region of New South Wales. In 2017 Nicole was the recipient of the Byera Hadley Scholarship. Nicole’s practice encompasses coastal strategy, design and planning – focusing on how we inhabit and manage coastal areas. She has contributed to the NSW State Government’s Coastal Design Guideline, and is widely recognised for her expertise and commitment to coastal design strategy and the revival of ocean and harbour pools in Australia.

Kiama, Werri Beach. Photo: Nicole LarkinTypology Overview

Resilience in Western Sydney and Wianamatta

WORDS: SCOTT DAVIESWestern Sydney, with a population now over 2.6 million people1, would be Australia’s third largest city – just larger than Greater Brisbane with 2.5 million people2, and Greater Perth with 2.1 million people.3 Western Sydney’s communities are among this nation’s most vulnerable. In the lead up to the recent NSW state election, the Western Sydney Regional Organisation of Councils (WSROC), the peak body representing councils in Greater Western Sydney, identified climate change and resilience as one of the most critical issues to be addressed in forward planning.4

“Western Sydney communities are being battered by climate change, having endured unprecedented bushfires, floods and heat stress… Heat stress kills more Australians than floods, fires and storms combined. We need the NSW Government to make heat resilience a Premier’s Priority” – Councillor Calvert, WSROC President.

To put some specific metrics around this, the Australia Institute regularly updates research on extreme heat in Western Sydney.5 We know that Western Sydney already experiences temperatures 6 to 10 degrees higher than Eastern Sydney during extreme heat events. And the number of days per year over 35 degrees has increased from an average of 9.5 days in the 1970s to 15.4 days today. By 2090, days over 35 degrees could more than triple to a projected 52 days. CSIRO and the Bureau of Meteorology project that across Western Sydney between a quarter and a third of summer days will be over 35 degrees by 2090.6

A city of this size demands significant design focus to ensure that it is liveable and resilient to climate change. Resilience is therefore a critical driver to the design and planning of Western Sydney, and to one of its key emerging precincts – the Western Sydney Aerotropolis/Wianamatta.

The approach to resilience throughout the Aerotropolis is complex and requires coordination across a range of government agencies and stakeholders. From a design perspective, policy settings relating to bushfire risk, flooding, stormwater, ecology and heritage have influenced the design thinking. But it’s the overarching approach to design with Country and with landscape that underpins everything –and allows the emergence of a city resilient to future climate change risks.

The urban design and landscape structure of the Aerotropolis plan has been underpinned by Country, specifically water, landscape, topography, soil, heritage and culture.

Precinct planning has prioritised protection of and access to green (open space), blue (water) and pink (social) infrastructure for future residents and workers to ensure a liveable and resilient urban system. By listening to and learning from Indigenous Elders, resilient, sustainable and liveable neighbourhoods is an inevitable consequence.

Dr Danièle Hromek of Djinjama brings a Countrycentred approach and Designing with Country methodology to built environment projects. This is based on the understanding that Country intuitively has its own methodology – a relational methodology guided and inspired by Country itself. Danièle’s approach – based on First Nations Knowledge systems grounded on the land – embeds a holistic understanding of the world and everything in it into the design process. “We know Country is alive and sentient and can communicate, and along with guidance from key Knowledge Holders into Country, we are guided into the process.” Enabling this approach in projects such as the Aerotropolis ensures community, culture and kin are inherently considered as part of Country.

DESIGN WITH COUNTRy

The physical elements of hills, ridgelines, alluvial creeks, dams, open parkland and forested areas give rise to the intangible and the visible: a connection with Country, a Cumberland Plain character, and landscape elements that foretell of this being a place like no other. This is undeniably Western Sydney – the Parkland City.

A connected natural system of blue and green infrastructure is the key structuring element of the urban fabric of the Aerotropolis. The main creeks – Wianamatta – South, Badgerys, Kemps, Cosgroves and Duncans become the spine of the Aerotropolis Parkland City. Smaller creek tributaries then define the public domain and open space framework.

This framework creates a foundation for a wellconnected, walkable and liveable city. It retains and re-establishes healthy, interconnected blue-green and soil systems. This ensures the ongoing resilience, balance and health of the whole system that preserves landscape’s capacity to retain water, provides biodiversity

Access to high quality public space enhances opportunities for urban cooling and resilience. Image source: Hassell.

Access to high quality public space enhances opportunities for urban cooling and resilience. Image source: Hassell.

corridors for wildlife and reconnects remnant endemic fauna and flora communities. And importantly, this offers an urban framework that has capacity to remain cooler during hot summer periods.

A NEW APPROACH TO BLUE AND GREEN INFRASTRUCTURE

The Aerotropolis will have compact urban form –a place where centres and local communities are connected by walking, cycling, interaction and collaboration. A compact urban form minimises the urban footprint and leaves more land for open spaces, waterways, and recreation areas. It allows people to access a diversity of uses within walking distance of centres, open space, or transport.

Open space throughout the Aerotropolis needs to accommodate a range of functions to ensure resilient, place-based and sustainability outcomes. This includes:

• water detention and stormwater-flow paths along ephemeral creek corridors to the Wianamatta system

• perviousness – areas of landscape where rainwater can permeate the soil profile, helping minimise stormwater run-off and keep urban neighbourhoods cool

• urban cooling – areas for tree canopy and green spaces that provide transpiration to cool surrounding areas

• heritage – celebrating culture and promoting access to Country through the cultural landscape – including heritage-listed sites

• biodiversity – providing a foundation for the conservation and enhancement of important vegetation communities, and

• corridors for wildlife migration.

Connecting and designing with Country is a process to truly connect with place and allow the creation of resilient neighbourhoods. It’s a method to learn from the oldest culture on earth. And critically, it’s a method to help us move towards sustainable development.

NOTES

The Aerotropolis precincts seek to support a net positive outcome across ecological, social and economic sectors. By listening to and designing with Country, this early planning phase of the Aerotropolis sets up a foundation for future sustainability. ■

Scott Davies Aff. RAIA is an urban designer at Hassell creating healthier, more resilient and connected communities across projects of every scale – from broad regional strategies to community-led revitalisation. Hassell led the urban design approach across the Aerotropolis. The design with Country approach was undertaken in collaboration with Djinjama. Precinct planning was undertaken in collaboration with Hill Thalis Architecture and Urban Projects and Studio Hollenstein.

1 https://profile.id.com.au/cws#:~:text=The%20Western%20Sydney%20(LGA)%20Estimated,rolled%20out%20across%20this%20site

2 https://www.abs.gov.au/census/find-census-data/quickstats/2021/3GBRI

3 https://www.abs.gov.au/census/find-census-data/quickstats/2021/5GPER

4 https://wsroc.com.au/media-a-resources/releases/support-for-vulnerable-communities-tops-western-sydney-election-wish-list

5 https://australiainstitute.org.au/report/heatwatch-extreme-heat-in-western-sydney-2022/

6 chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://australiainstitute.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/HeatWatch-2022-WEB.pdf

Brisbane flood-resilient ferry terminal

BRENDAN GAFFNEy DIRECTOR COX ARCHITECTURE AND ARNE NIELSEN DIRECTOR AURECON WORDS: JAmILEH JAHANGIRIArchitecture plays a critical role in responding to the needs of those affected by natural disasters. Through design, architects can help to mitigate the impacts of climate events by offering adaptive and resilient strategies, often developed as part of disaster recovery solutions. One such approach is evident in the Brisbane ferry terminal redevelopment project by Cox Architecture in collaboration with Aurecon.

Cox Architecture and Aurecon’s solution for the Brisbane ferry terminal creates simple, resilient infrastructure that uses a series of simple responses to natural environmental processes, such as tidal changes and river surges to provide a new typology for ferry terminals that is simultaneously beautiful, accessible and sustainable. By carefully observing the causes behind the destruction of the ferry terminals by the 2011 Brisbane floods, the project radically questioned the typical ferry terminal design. The competition-winning model consists of three key innovations highlighting the lessons learned and the benefits of designing futureresilient projects.

The first concept involved analysing the shape of the ferry pontoons, replacing the existing square-shaped pontoons with a simple boatshaped pontoon instead. The project team discovered that this new platform shape would naturally provide less resistance to flooding. By questioning the business-as-usual practice, the Cox team with Aurecon were able to develop disaster-risk reduction and recovery strategies.

Secondly, by reviewing the current structural solution, the project questioned the need for the number of piers commonly incorporated in typical ferry terminal design. By locating a large singular pier at the upstream end of the pontoon, the project minimised the provision required for a structurally stable yet resilient ferry terminal. The reduced number of piers also increased the ability for the structure to deflect debris and vessel impact. To facilitate this solution, the Cox team with Aurecon challenged the normal build and adapted an alternative method of design and production. For the team of Cox Architecture with Aurecon, rather than using the previous design method of a ribbon of pylons, they completely reimagined the concept of a ferry terminal structure, resulting in a solution that focuses on a singular sculptural pylon that provides a structurally stable system with minimal assembly.

The third innovation was to challenge the existing gangway model which sat transversely to flood flow and acted like a dam for debris, exacerbating destructive downstream forces. With the integration of a buoyancy tank and some clever mechanical engineering to allow decoupling, the new gangway swings downstream in a flood, allowing the flood and debris to pass through rather than standing dam-like against it. This integrated structural innovation now allows the gangway to rotate during floods and be re-positioned after flood waters recede. This solution is the result of a multidisciplinary-design approach that combines the knowledge of architects and structural and mechanical engineering to design for flood and climate-change events. ‘Go with the flow’ became the project description, referencing the futility of fighting against nature, and its immense and invincible forces.

Pursuing an integrated, multidisciplinary process from the outset, Aurecon’s expertise in designing marine structures was critical to the success of the project. Together with Cox the ferry terminal design sets a new benchmark.

The connection between intelligent architectural design and environmental performance is fundamental to a climate-responsive built environment. From bushfires, floods and heat stress, the world is experiencing an increasing number of disasters. As designers, a focus on smarter and more resilient outcomes is required. Architects, urban planners, landscape architects and engineers, need to work collaboratively using our capacity to work with disaster-prone or impacted communities and develop wellintegrated responses that will guide disaster-risk reduction and reduce long-term rebuilding postdisaster. If we can go with the flow and work with nature in a more agile and intelligent way, we may be able to be more economical with our structures, rather than building taller, more substantial, or exponentially stronger. ■

Do no harm

INTERVIEW: CLAIRE mCCAUGHAN WITH LACHLAN DELANEy OF SAGO COLLECTIVEWhen we consider a commitment to Net Zero Emissions by 2050, how do we stop doing something that is known to be harmful? That is the precept for an ethical framework within climate change.

Broadcast by the Canadian Centre for Architecture: How to do no harm, is a vivid diary of an architect in an ethical crisis. One entry starts: “It is not easy to accept that one’s profession causes harm. We like to think of ourselves as good people–and most of us are. But we live in systems that we did not choose, feel unable to change, or may not even perceive.”

Claire McCaughan interviewed Lachlan Delaney of Sago Collective to discuss how their for-profit and not-for-profit entities have evolved under these ethical pressures.

Claire McCaughan (CM): Why did you start Sago?

Lachlan Delaney (LD): Sago Network was formed by three architects, Rosemary Korawali, Brendan Worsley and me, after we undertook design-build volunteer work in Papua New Guinea (PNG). Prior to forming Sago Network, Rosemary grew up in PNG with a lived awareness of the development challenges faced by her country, and she became PNG’s third

registered female architect. Brendan and I had undertaken community development work throughout indigenous Australia and Africa. We certainly didn’t see architecture as the answer to community development challenges, but we did see the architect’s skillset as able to contribute to capacity-building with communities. As young architects we saw community work as a long-term commitment that would bring balance and purpose to our practice. Sago Network emerged as an effort to address PNG’s community development challenges. Our name is inspired by the creative use of the sago palm, which local people refer to as the ‘tree of life’ which provides various crafted building materials (woven walls and roof thatching) and staple foods.

CM: How has Sago changed since you started in 2008?

LD: Initially Sago relied on volunteer weekends and leave from full-time architecture work but over fourteen years the network has evolved into Sago Collective spanning three purposedriven entities and an amazing team of 37 full-time team members (including 22 PNG nationals) with diversity spanning from architects and carpenters to community development professionals, water and sanitation specialists and a registered nurse. Our mission to address development challenges with greater impact and scale has not only resulted in a diverse team well beyond architecture but has also prompted us to question how design thinking can impact communities at scale to improve village health. This thinking led to the development of a manufactured product, the Sago Dry Toilet, a waterless sanitation solution that is locally manufactured and accessible to communities via hardware stores throughout the country.

CM: Can you explain more about your work in capacity-building for communities, and leaving our design hats at the door?

LD: To be an effective collaborator, we have to realise that conventional architectural outcomes, such as a well-crafted building, is often not the most relevant contribution to community development challenges. For instance, 85% of PNG’s population (approximately 6.6 million people) do not currently have access to a sanitised toilets and 13% of all child deaths under the age of five (approximately 1400 children per year) die from diarrhoea and dysentery which is attributed to informal water and sanitation.

Our early work in PNG perhaps made the mistake of taking too much of an architectural approach when we designed and built aid-posts for primary healthcare delivery. Our team quickly came to realise that stopping the need for the aid-post was the higher-order priority and, thus, water and sanitation became our focus. The Sago team has come to realise that listening, analysing, collaborating and coordinating lesstangible outcomes is what communities often require. We think of this as “designing the invisible” because it relies on identifying causal relationships, engaging in community dynamics, connecting people and developing collaborative ideas to overcome challenges together. This still utilises architects’ skillsets, but it doesn’t always result in architectural outcomes. Paul Pholeros and the exemplary work of Healthabitat were the leaders of this thinking in Australia and our close relationship with Paul was hugely formative.

CM: It’s difficult to see a strong approach to generosity and giving in Australian architecture practices, so it could appear to emerging architects and students that balancing profit with social-driven missions is difficult. How do you do it?

LD: Sago’s founders have always found a rewarding balance between our architecture work and our community work which quickly became reflected in our organisational structure as a not-for-profit NGO and for-profit design-build entities. Today, Sago Network operates as a financially sustainable NGO with our community work having gravitated from its volunteer origins to the current 24 employees across PNG and Australia. Our community work is supported by the Sago Design and Sago Build teams in Sydney who devote part of their time toward innovative ideas that support Sago Network’s community agenda. These ‘ideas for impact’ enrich the professional experience of our architecture and construction teams and they strengthen Sago Network’s community offering in PNG but the operational model is now such that the NGO is financially sustainable in its own right. ■

Claire McCaughan RAIA is an architect, co-director of Archrival and director at Custom Mad. Claire’s focus on ethics frameworks is driven by ambition to find spatial justice for the human and non-human.

Lachlan Delaney is director at Sago Collective, an interconnected team of architects, builders and community development professionals who work across the three entities of Sago Design – a residential architecture practice, Sago Build – a residential construction company, and Sago Network – a not-for-profit (NFP) community development non-government organisation (NGO).

Architects Assist

INTERVIEW: ELISE HONEymAN WITH JIRI LEV

Last year Elise Honeyman connected with Jiri Lev, founder of Architects Assist, to learn about the Australian Institute of Architects initiative, its implementation and lessons learned since its inception in January 2020. The conversation touches upon the catalyst for its creation and the various ways architects can make an impact by providing alternative pricing structures, including pro-bono, delayed or reduced-fee services.

Can you tell me a bit about Architects Assist and why you were inspired to create the initiative?

Architects Assist came about during the 2019/2020 bushfires. The awful stories of families losing their homes was reinforced by the inescapable smoky skies that affected Australia, keeping it in the forefront of our minds. As an architect with a background in web development, I created a simple website to connect architects with clients who suffered during the fires to form a partial or full pro-bono working relationship. There’s no shortage of official disaster recovery organisations with big names, funding and politics, however, I saw the need for something that struck a balance between a larger organisation and a coordinated grassroots solution. Architectural registration numbers are required for accountability yet ultimately it comes down to individuals just helping one another.

The response was quicker than expected, with no shortage of volunteers – I think it’s just human nature to do something to help.

Very quickly the process became unmanageable as I was individually emailing and connecting architects and pro-bono clients. With the Australian Institute of Architects, we decided the initiative would move underneath the Institute’s banner to increase the potential for an even broader impact. In time Architects Assist also expanded to include professionals from planning and landscape architecture. At the time of this interview, 636 architects, planners and landscape architects have registered with Architects Assist.

What type of building typologies have been built through the program?

The projects that can be built through Architects Assist is broad. Clients are often individuals, community groups and sometimes even councils. It can be anything from park shelters to a community hub workshop facility, to small cabins in the bush. There were a large proportion of regular homes that were rebuilt as modest sensibly designed BAL 40 and BAL FZ homes, appropriate to their context.

Something that can have a huge impact and is almost second nature to architects, is guidance for individuals on their next steps. Our knowledge of the industry, lingo and approvals bureaucracy is absolutely priceless. Sharing our professional expertise through an initial meeting or chat can provide a sense of direction and increase the client’s ability to make informed decisions, which means a lot to someone who has been through so much.

Why is pro-bono work so important and what do you think it is about architects that make them uniquely placed and enthusiastic to provide assistance?

Firstly, while we know the modern definition for pro-bono work, I’d like to emphasise the Latin meaning – for the public good. Our industry attracts a lot of individuals who have a sense of idealism and seek to do work that positively impacts the public. As Architects Assist demonstrated there is no shortage of willing architects and having an impact for good, during such a tumultuous time in people’s lives is payment enough. A large portion of the housing stock in Australia doesn’t last long or work very well, architects are uniquely placed to slowly but surely shift this. Not only can our services benefit individuals affected by natural disasters, but we can more broadly improve our housing stock, one project at a time. Our idealism and work in the pro-bono sector can make the world a better place.

Following the establishment of Architects Assist, you toured through regional Australia to promote it. What were some of the challenges and barriers to completing these projects?

Funding is always a problem, there’s never enough money for these projects, and often the plans and grant submissions are required before any money can be accessed. That is, however, an area where architects can help.

I also found the big challenge when travelling to these affected areas was dealing delicately with people who have been through an intense and emotional experience. Our day-to-day profession requires us to act as mediator in many ways, but this was amplified. It may be cliché but you must be a good listener and not overload the clients with multiple ideas and solutions. These clients have been through traumatic experiences and need a more measured empathetic approach –often a step-by-step road map to help navigate

may be perceived as only working on projects on the other extreme of the social ladder – building facilities for those in extreme disadvantage.

One of the biggest opportunities to improve housing standards, including through the provision of pro-bono work lies within the huge middle ground – simple to construct, humble and affordable buildings, designed to be functional, durable, comfortable and beautiful. They may not be highly acclaimed award-winning designs, yet we can have a far more significant impact through well-designed common buildings on the lives of individuals and the general housing stock. This idea can be applied to how we practice in general.

their way through a problem they never expected to have. It is a privilege to be invited in to help people during their time in need. It still makes me emotional three years on.

Another barrier was occasionally a lack of engagement from local governments, media and individuals when it came to spreading the word about the availability of Architects to help through Architects Assist. My understanding was this came down to the perception of architects only building million-dollar homes and therefore not really being helpful in these situations.

How can we position ourselves to help more effectively in these instances?

I think the public can misunderstand what an architect does. This is worsened by a perception of professional pride and archi-talk being inaccessible. This adds to the problem of poor housing stock in suburbia, not only because clients can’t see how an architect could help them, but these simple projects may been seen as less desirable to an architect.

As a profession we have an obsession with the 2% of projects that are full of expensive materials and difficult detailing. Alongside big commercial projects, we present these projects as if they are what we solely do. Pro-bono work

In disaster recovery projects, we should not underestimate the ways our industry knowledge and expertise can have an impact. The work done through Architects Assist varies greatly from beautifully finished projects to guidance through a grant application, to an initial chat, which gets a family on the right path to rebuilding in a clear and confident way. Our advice can help find a good, efficient and effective solution rather than a quick-fix reaction that compromises quality and eventually ends up in landfill. ■

Elise Honeyman RAIA is an architect and director of emerging practice, Abask Studio, founded in Newcastle NSW, after practicing across London and Sydney. She is a current member of the Australian Institute of Architects Regional Committee, was formerly the cochair of the Editorial and Communications Committee and was the founding General Manager of the Sydney Chapter of Women in Design and Construction.

Jiri Lev is an architect, urbanist, heritage advisor and educator. He is the founder of ArchiCamp, a grassroots architecture festival benefitting disadvantaged communities, the founder of Architects Assist (Australia) and Architekti Pro Bono (Europe), uniting hundreds of architecture practices for disaster recovery assistance, and the founder of Cohousing.com.au, an initiative for cohousing and ecovillage development.

Building more resilient infrastructure

WORDS: ALEXA mCAULEyIn 2022, it was reported that 68% of Australians lived in a local government area affected by natural disaster, mostly flooding,1 and in its 2021-22 annual report, Treasury reported that natural disasters cost the Federal Government $5.5 billion. Most of this is directed at disaster recovery. There is increasing recognition, including in Australia’s 2021 State of the Environment Report, that in a changing climate, which is bringing natural disasters of increasing frequency and severity, we need to invest more into building resilience, and that this will require a more collaborative approach between government, industry and community to absorb, recover and prepare for future shocks.

Resilience can be considered at multiple scales from local to global, and in many different types of systems, including natural and built environments. Extreme shocks such as natural disasters highlight the interconnectedness of these systems, with the potential for impacts in one area to have significant knock-on effects in others. Therefore, resilience of human settlements is supported by resilience in all their interconnected systems.

Resilient ecosystems support resilient human settlements by performing services such as slowing runoff, retaining and cleaning polluted water, and attenuating wave energy. Therefore, important ecosystems are protected and we invest in their ongoing care. Smaller pockets of urban bushland may not have the same legislative protection but are highly valued by the community, and they also support resilience by enhancing recreational opportunities, with benefits for physical and mental health.

Ecologists study resilience in ecosystems to understand their sensitivity to shock and stress and aid their recovery. Across a range of studies in many different types of ecosystems, there is broad consensus on the main attributes of resilient ecosystems: they are well-connected, spatially heterogeneous, and biodiverse. They are also adapted to variable conditions and have a level of redundancy in how their key functions are performed.2 In response to a shock, resilient ecosystems can quickly adapt to maintain their key functions. For example, after a bushfire, colonising plant species grow quickly, maintaining critical functions which enable other species to recover over a longer period.

Above: Restored wetland at mountain View Reserve, Cranebrook.

Photo: Paul mcmillan

Right: Reconstructed creek and wetland at Blackman Park, Lane Cove West.

Above: Restored wetland at mountain View Reserve, Cranebrook.

Photo: Paul mcmillan

Right: Reconstructed creek and wetland at Blackman Park, Lane Cove West.

Principles from ecological resilience (connectivity, diversity, adaptability and redundancy) can be applied to built infrastructure. For example, significant changes are needed to our energy infrastructure to incorporate renewables, and resilience is a key consideration in this transition. Renewable energy sources will add diversity to the system, which will require increased connectivity in the grid. The transition to renewable energy also highlights how, while it has been relatively straightforward to add new features such as rooftop solar panels, this creates new challenges as the system is increasingly made up of diverse and decentralised infrastructure. A whole-ofsystem approach is needed to design a more resilient electricity grid.

Resilience also needs to be improved in water supply systems, which are increasingly impacted by climate shocks. For example, Bermagui’s water became undrinkable during the Black Summer bushfires and Dubbo’s water became undrinkable due to flood-related contamination in 2022.3 Recent droughts have also impacted on water supplies in many parts of the country, leading to restrictions on water use while communities are facing hotter conditions and heatwaves. A more resilient approach to water supply would include more diverse water sources, such as rainwater tanks and other small-scale decentralised water treatment and reuse systems. Even very simple measures that retain more water in the landscape, such as passive irrigation, would reduce the impacts of drought and heat on living infrastructure, supporting community resilience.

Architects can learn from the principles of ecological resilience by designing to create diversity in urban design and built form, and by designing a level of redundancy into living and built infrastructure, supporting future flexibility and adaptation. For example, recent floods have highlighted a need for housing that is more flood-resilient, including the use of materials more resistant to inundation, and structures that enable easier evacuation, such as egress onto the roof. Architects should also recognise the need for collaborative, whole-of-system approaches to support management of diverse, decentralised assets in complex, interconnected systems. Working at the intersection between government, industry and community, architects are well placed to play a greater role in fostering high-quality cooperation, collaboration and partnership between these sectors, to support improved management of healthy ecosystems, decentralised infrastructure and resilient communities. ■

Alexa McAuley is an environmental engineer and director of multi-disciplinary design consultancy Civille. She works to create more sustainable, liveable cities by integrating environmental engineering with urban ecology, landscape and urban design.

NOTES

1 ABC News 2023 ‘East coast flooding saw majority of Australians covered by natural disaster declaration in 2022’, accessed 16 January 2023, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2023-01-13/majority-australians-live-disaster-zones-2022-floods/101851620.

2 Cassin, J and Matthews, J H 2021 Chapter 4, Nature-based solutions, water security and climate change: Issues and opportunities Pages 63-79, Nature-based Solutions and Water Security Editor(s): Jan Cassin, John H. Matthews, Elena Lopez Gunn. Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-819871-1.00017-8

3 Guardian Australia 2022 ‘NSW city goes a week without drinkable water after floods cause contamination’, accessed 16 January 2023, https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2022/jul/13/nsw-town-goes-a-week-without-drinkable-water-after-floods-cause-contamination.

Creating climate-ready environments

WORDS: CAROL mARRAClimate change, it in its various guises, throws at us sea-level rise, coastal erosion, bushfires, heatwaves, increased rain, flooding, winds and cyclones. The problems faced are not only varied but complex and interrelated. Concurrently, we are faced with biodiversity loss, an aging population and the ever-present affordability of housing. Strained and stressed, nature and humans muddle along on a trajectory lacking clarity and purpose.

While climate change is now mostly acknowledged as fact and we are seeing the consequences, the knowledge of climate change is anything but new. Alexander von Humboldt, the 18th century German naturalist, explorer and polymath, travelled through the Americas and observed firsthand the effects of colonialism on nature. True to his time he used Western scientific methods to study nature from the poles to the tropics. Humboldt came to the same insight that First Nations peoples have long held – nature was an indivisible entity, a web of life, including humans, where everything is connected to everything else. He was critical of the exploitation of nature, and correctly posited that the activities of men had the potential to affect the climate both on a local and global scale.

Though he was much admired, having influence both within the scientific establishment and the imperial court, the status quo carried on paying scant attention to his insights. No doubt the resources of nature, and its capacity to deal with abuse, seemed infinite at the time but humanity was set on an unsustainable path, the consequence of which, climate change, is our unwanted inheritance.

The Churchill Fellowship I received some years ago continues this tradition of observation and investigation in foreign climes, in the hope new insights might inform a way forward. I travelled to China, Japan and the Philippines to investigate vernacular design strategies to cope with extreme climate events. The overarching conclusion of this research was that human ingenuity worked best when nature was not cast as the enemy but rather was understood and respected. In some places this attitude went as far as the worship of nature. Simple but effective design strategies do not attempt to overcome or dominate nature but create buildings with in-built adaptation and mitigation techniques. For example, courtyard building forms in China that provide effective freeboard during high rainfall events, collect and store rainwater, and incorporate durable materials which can be subject to wet/dry cycles. Or in the Philippines, houses incorporating sophisticated but low-tech ventilation techniques to remain cool during the oppressive heat and humidity without resorting to air conditioning.

The pace of change requires us to reconsider our tools of governance, and our belief in technological solutions and breakthroughs. It requires design and nature-based solutions which do not privilege humans at the expense of all else in the natural environment. It requires principles and strategies that provide guidance without being didactic. One such effort in our practice is research into and the creation of a design guide for climate resilient housing funded by an Alastair Swayn Foundation grant.

The guide will be informed by historical and vernacular precedents as well as current best practice, mining past knowledge and experience to develop design-for-resilience principles, strategies and techniques for designers in the age of climate change.

Architecture needs to once again become a broad art, concerned with subjects both laterally and in depth – to be aesthetic, functional, innovative and sustainable in equal measure. It is time to move climate to the forefront, not just one of many issues to consider, but the key driver of built environment design. We can either design our buildings to mitigate and adapt to climate change, or climate change will design a world in which our built environment will cease to cope. ■

Carol Marra is a Churchill Fellow and architect at Marra + Yeh Architects working across practice, education and government. She has contributed to the Environment Design Guide, served as a juror for the NSW Architecture Awards and as a member of the Peer Review Committee for the 2023 UIA World Congress of Architects.

Sandbags and seawalls: Designing a different adaptation future

WORDS: KATE RINTOULThose of us who act as custodians of coastal places have some hard decisions to make. Damaging winds, extreme rainfall and sea-level rise are triggering coastal erosion and inundation that will effectively re-draw our foreshores. Design thinking offers a valuable approach to decision making, posing questions from many angles and hearing from diverse voices as a way of developing a creative approach to the problem itself.

Consider a beach on the NSW South Coast. There’s the beach itself, the dunes, a shared path, a surf club, a carpark and an ocean pool. As a connected place this set of assets is of high value. The local council maintains the place using local rate-payer funds for a user population that is roughly 60% locals and 40% visitors. Let’s assume the surf club is also heritage listed, the dunes are home to an endangered ecological community and the area is of significant Aboriginal cultural value. Climate modelling shows that the risk of these assets being inundated due to sea-level rise is high.

What do we do, and how?

There’s something seductive about designing our way out of a crisis. It’s the stuff of postapocalyptic speculative fiction, we’re fascinated by the concept of re-engineering our places to sustain some semblance of those things that we value in the face of fundamental change. But when does adaptation begin to erode the value we seek to protect? What dangers might there be in the justification to remodel or relocate buildings and infrastructure for their own good?

Increases in sea level, flooding, storm-tide inundation, erosion, bushfire and land-surface temperature are all present impacts of climate change. For coastal areas with significant river and creek systems, the first four threaten a broad array of building assets, infrastructure and natural places of high value. Many of these are publicly owned and managed: schools, social housing, harbours, ports, sewerage treatment plants, boat ramps, beaches, open spaces, ocean pools, roads and carparks to name a few.

Local governments are at the pointy end of public space and asset management. Many are making good ground declaring climate emergencies, reviewing their assets and prioritising adaptation actions. Climate adaptation plans commit councils to considering climate change in all relevant decisions, from broad-scale strategic plans to routine maintenance. NSW coastal councils are required to prepare Coastal Management Programs to consider the impacts of sea level rise and appropriate management responses, and adopted programs open the opportunity for state grant funding of endorsed actions.

The bigger picture strategic planning is easy to envisage but difficult to implement. We know that certain low-lying coastal areas will experience more frequent and more intense flooding, and changes to zoning and other development controls would be a rational response. But limiting housing supply in the current planning climate is an unpalatable position. And that is to say nothing of the political, administrative, economic and social impacts of reducing development rights or implementing compulsory acquisition.

SEAWALLS: DESIGNING A DIFFERENT ADAPTATION FUTURE

WORDS: KATE RINTOUL

Let’s bring it down to a smaller scale and consider those individual assets that local governments have responsibility for. At what point should a council decide that it is not viable to keep investing in the assets that serve climate-vulnerable areas? Will it depend on how loudly those communities complain or how adept they are at mobilising political will? It’s an awkward question, but one that will surely be factored into asset-life calculations and maintenance plans moving forward, if it isn’t already.

These kinds of decisions and the frameworks that guide them are subject to astute technical investigation, cost benefit analysis and community input. A large team of technical specialists will have input into the risk modelling, the asset life calculations, the public value determination and the range of engineering scenarios that will be held up as possible solutions. What is often lacking from this process and team is input from a built environment designer – an architect, an urban designer, a heritage architect or a landscape architect. These actors typically only enter the arena once the design requisition is written, often by an engineer.

Designers offer the most value when they are involved from the very beginning. Good built environment designers see the whole picture

and are able to unpack and question a brief in order to neatly articulate the problem to which a design solution is to be applied. Even better than being retrospective authors of reverse briefs, designers should be involved from the beginning, informing the definition of the problem itself. Designers are trained to be adept storytellers, communicating with a broad range of stakeholders about place and crafting a value proposition from an invisible future. And, critically, good designers are creators of whole places – places that are contextual, well performing, inclusive, liveable, functional and engaging. Their role in shaping adaptation responses to our coastal places is critical. Yet, in local government, these professionals are thin on the ground.

Let’s think back to that beach on the South Coast and consider the frameworks we might use to make decisions about its future. Commonly, a protect, accommodate or abandon framework would be applied in such a scenario. Do we protect the beach and shared path with structurally engineered seawalls to prevent erosion and wave overtopping? Do we accommodate the changing conditions by modifying floor levels and access ways, and designing new infrastructure to be light and relocatable? Or do we abandon the place, leaving the assets at the water’s edge to the elements, or shifting them inland?

“

... good designers are creators of whole places – places that are contextual, well performing, inclusive, liveable, functional and engaging. Their role in shaping adaptation responses to our coastal places is critical. Yet, in local government, these professionals are thin on the ground.

Given a voice, and a role in decision making, architects and designers might ask some of the following questions:

• what makes the place valuable, and how is that value understood and appreciated by those who know and use it? Is it the assets that people value, or the broader natural environment in which those assets are sited?

• what are the spatial interdependencies that contribute to the place’s value? How has the place been designed to respond and relate to its natural setting? Does the place play a part in a larger system or network? Could modifying or relocating aspects of the place compromise those interdependencies or networks?

• what future state would see the value of the place maintained? What might an evolved version of the beach, its pools and surf club and other assets look like? How might that picture change over time, as it responds to a new climate normal? And how might that vision be informed by and owned by the community?

As we continue to understand and address the impacts of climate change, government agencies are well positioned to make decisions that will result in positive outcomes for local communities. Built environment designers can bring much value to this process and should be encouraged to step into strategic, asset design and management positions in local government. And government agencies should be looking for ways to attract and retain them. ■

Kate Rintoul is an architect working in strategic planning for local government. Kate is co-chair of the Designers in Government group which seeks to create community, share insight and experience, and raise the profile of design and designers in a government setting.

Resilience and heritage

WORDS: JENNIFER PRESTONfor our built heritage confronted by bushfires in 2019/2020. What made this historic town resilient was its water supply, airstrip and the availability of the RFS in sufficient numbers.

During the 2019/2020 bushfires in New South Wales, many heritage buildings, sometimes entire towns, came under threat with historic buildings destroyed and damaged. More recently, in the 2022 floods around Lismore, devastating damage was done to infrastructure and buildings. It’s clear that the resilience of our heritage assets, their capacity to withstand or successfully recover from disasters, depends largely on the measures put in place to protect them.

The historic town of Yerranderie, an old silvermining town in the Burragarong Valley was surrounded by the Green Wattle Creek blaze that raged south-west of Sydney for two months from late November 2019. Although it sustained an extended onslaught from the fire it was a town that the Rural Fire Service were able to defend with a tanker for each building and utilising the town’s private airstrip with a dozen aircraft. This was one of the good news stories

Not all towns were so fortunate. The town of Cobargo, west of Bermagui, was severely impacted by bushfire losing much of the Main Street Conservation Area and at least four heritage-listed buildings. Buildings on the Princes Highway and Bermagui Road that were previously in excellent condition with a high degree of historic integrity were completely destroyed. These included the former grain store, the timber building of the former Australian Joint Stock Bank built in 1882 and two double-storey weatherboard buildings with traditional shopfronts from the 1880s. The damage in Cobargo was so extensive because of a poor water supply, unusually dry conditions, heavy fuel loads, an unusually high number of thunderstorm-ignited fires and challenges the NSW Rural Fire Service had not experienced before. The damage was compounded when electricity and phone wires were destroyed by the blaze.

In the alpine areas of NSW and the ACT in Kosciuszko and Namadgi National Parks, more than ten historic alpine huts were destroyed, and the Kiandra Courthouse was severely damaged. Great effort was put into protecting many of the huts through a variety of mitigation measures by NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service and ACT Parks and Conservation. These included establishing bare-earth lines where graders were used to create fire breaks, clearing fuel loads, installing and activating hoses and drip systems, placing buoy walls containing 48,000 litres of water to be deployed by sprinkler, removing timber infrastructure, and literally wrapping entire buildings in fire retarding foil.

Despite these efforts many of the historic huts including Pattinsons Hut, Wolgal Lodge, Mathews Cottage, Delaney’s Hut, Sawyers Rest House, Hill Rest House, Happy’s Hut, Brooks Hut, Round Mountain Hut, Bradley and O’Brien’s Hut and Four Mile Hut were all severely damaged or destroyed.

One of the buildings severely damaged was the Kiandra Courthouse. It was designed by the New South Wales Government Architect, James Barnet, in 1859 and built during the period when the area experienced a short gold rush. It was added to the State Heritage register in 1999 and many of the 1960 additions were removed. Not only was the courthouse building severely damaged to the point where it may not be feasible to restore it, but the collection of historic material related to the area’s mining and recreational history that was housed within the courthouse was also lost. Kiandra Courthouse, Patterson’s Hut and Wolgal Hut had been conserved and restored over the past decade following damage during the 2003 bushfires.

In February and March of 2022, the area around Lismore was inundated by unparalleled flooding and many historic buildings were impacted. In the clean-up process, as more recent plasterboard linings and false ceilings were removed, the beauty of the original structure and its detailing was revealed. It also became clear that the original buildings with their tiled walls, asbestos floors, high pressed-metal ceilings and solid hardwoods such as cedar and oak had been designed to be resilient to flooding. Later alterations and decorative linings had increased many buildings’ susceptibility to flood damage. As part of effective flood mitigation strategies, we need to understand the natural function of floods, natural flood behaviour and risk. We also need to look at our heritage structures in flood-prone areas and understand the design elements that have enabled them to survive past inundations. Once collected and analysed, this knowledge can help us to build new developments outside known flood zones to mitigate the impact of potential future flooding extremes.

It is stating the obvious to say that not all loss of heritage assets occurs through natural disasters. Human-made disasters seem to occur on a regular basis whether through neglect or deliberate action. The recent fire and partial collapse of an old RC Henderson hat factory in Randle Street Surry Hills vividly illustrates how vulnerable buildings are when left empty. This is particularly true of vacant buildings that provide free-sleeping accommodation for the homeless, and of mysterious, intriguing, and sometimes spooky heritage structures which provide the temptation to break in and explore and then post discoveries on social media. This then amplifies the risk.

To help our built heritage to be resilient and have the capacity to withstand or recover from disasters, whether natural or human created, we need to plan not only for its protection now but maintain those plans consistently into the future. The ability to muster the full resources of the RFS can save an entire town as was the case with Yerranderie, but as the fight for Cobargo illustrates, if the resources including an adequate water supply are not available the results can be disastrous. Measures such as sprinkler systems can make a real difference and for smaller buildings, temporary buoy walls with associated sprinkler systems can be moved into place ahead of the threat or the entire building can be wrapped in fire retardant foil which may prevent or at least reduce the severity of the damage. All heritage buildings in bushfireprone areas require a bushfire-management strategy and those in flood-prone areas require a flood mitigation strategy. Practises of cultural burning, where small blazes are used to clear underbrush, are likely to reduce the likelihood of catastrophic fires. These strategies need to be well-thought-out, practical and regularly checked and updated. ■

Resilience, health and equity

WORDS: ANDy mARLOW

Architecture has the potential to contribute positively over the next few decades as humanity adapts to the changing world we have co-created. While the resilience of our current building stock is poor, we have an opportunity to improve it and create new buildings that are appropriately resilient to the future we face.

Responses to climate disasters, unsurprisingly, garner most attention and while incredibly important they only tell part of the story. Buildings that resist the physical impacts of fire, flood and storm are required in certain locations, although there will be increasing calls to retreat from some, yet many places will not be impacted in these ways.

The chronic stresses are ones that will be more geographically dispersed – increasingly long and intense heatwaves and, as we saw in 2019/2020, the impacts of bushfires significantly beyond the fire front itself.

The role of architecture positively impacting on the health of a building’s occupants would be one measure of success. Responding to the climate crisis presents the opportunity to not only address these newer stresses but also to remedy those previously created.

Historically, and even today at a residential scale, architecture has relied on natural ventilation for maintaining indoor air quality. While effective when conditions are favourable, it is a driver of poor outcomes in many situations.

Airtight, appropriately ventilated buildings provide great indoor air quality year-round while also allowing for natural ventilation when the

Huff’n’Puff Haus by Envirotecture, a strawbale house that is off-grid with completely self-sufficient power, water and waste. The certified Passivhaus building focuses on being healthy, natural and non-toxic. Photo: marnie Hansonexternal environment is desirable. Increasingly in Australia, architects have been embracing the Passivhaus standard as a low risk, high-reward pathway to delivering health and comfort for their clients.

The data above shows the impacts of airtightness and ventilation in dramatically reducing the inflow of particulate matter (PM2.5 and smaller) into a Canberra home during the Black Summer bushfires. Many Passivhaus projects now have additional HEPA filters that can be easily inserted during smoke events to further reduce indoor pollution.1

While focus on extreme events garners attention, some existing stresses are far less publicised. Australia has the highest prevalence of asthma in the world and while the causes are varied, poor indoor air quality is a factor.

As this article reaches you, winter will be setting in and many will be remembering that even in our own wonderful state it does get cold, if only for a few short months. With most older

homes not being fully heated, most are not consistently warm nor inadequately insulated. The cold surfaces of the walls befriend warm, humid air and condensation and/or mould. Instinct prevents people from opening windows due to cool outdoor temperatures, resulting in increasing humidity levels (from breathing, cooking, showering) which exacerbates the impacts.

While higher humidity may cause mould where the surfaces are cool, for those wealth enough to afford the energy bills, this can be avoided by heating rooms sufficiently regardless of the building’s levels of insulation and ability to retain that warmth.

Unfortunately, the lack of reliable ventilation also causes carbon dioxide levels to rise – 1000ppm is generally accepted as a maximum for good indoor air quality. Research on my own house showed that a non-mechanically ventilated bedroom in a leaky (10ACH50) house can reach 2400ppm overnight. Data from the monitoring of various schools shows classrooms reaching over 5000ppm.

/ RESILIENCE, HEALTH AND EqUITY

WORDS: ANDY MARLOW

Mechanical ventilation and secondary glazing have provided a temporary fix for my child’s room, yet it is not a holistic or efficient solution. The Passivhaus standard with its interrelated principles of airtightness, insulation, appropriate windows and shading, minimisation of thermal bridges and mechanical ventilation underpin my strategy.2

When implemented consistently, these principles deliver not only healthy and comfortable homes but also efficient ones. Airtightness equals control which you would think could appeal to the stereotypical architect! However, choosing some principles while ignoring the others, will have undesirable consequences, as decades of building science have shown.

As the global response to the climate crisis evolves, the smarter reactions have been blending mitigation and adaptation. Low energy buildings are a critical aspect of mitigation and net zero buildings are a subset of those when appropriate amounts of renewable energy generation are paired with them. It is important to remember that resilience is not net zero but it is an appropriately performing thermal envelope. Solar panels alone will not save us.

The UK cities of Exeter and Norwich have been leading the way. All new social housing constructed is now designed and built to meet the Passivhaus standard. In 2019, the Mikhail Riches designed Goldsmith Street Housing took out the Stirling Prize, RIBA’s highest accolade.

The climate crisis is an opportunity for architects to equip society with the best chances of success. We can embrace the (building) science and apply our skills to create a beautiful future that allows us all to thrive; the data has been in for decades. Can we please accept it as we have accepted gravity and create the future we need – everything, everywhere, all at once. ■

1 https://renew.org.au/renew-magazine/efficient-homes/keeping-the-smoke-out/

2 https://www.envirotecture.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/S56-EE-Andy-on-air-quality-in-increasingly-airtight-homes.pdf

An architect on the ground after the Lismore floods

WORDS: JOHN DE mANINCORThis story starts 40 million years ago when Gondwanaland was covered in rainforest. Fast forward past the invasion of 1788 to the 1840s when cedar getters began clearing the “Big Scrub”, an area of approximately 75,00 hectares of remnant rainforest near Byron Bay, Ballina and Lismore: Bundjalung Country. By 1900 forestry and agriculture had wiped out 99% of the forest.

My part of this story starts a few years back when my family and I moved to a remote valley in the region where we are regenerating a small patch of the Big Scrub. More specifically, it starts on 28 February 2022 when the region experienced intense, prolonged rainfall.1 The biggest flood event recorded in colonial history swept through Lismore, where our own office building is located, displacing thousands from their homes and causing hundreds of million dollars’ worth of damage – directly or indirectly as the result of colonisation and climate change. What’s fascinating, if not concerning to me is that during the multiple community events on building resilience I’ve attended since the floods, everyone seemed to be talking about building

back better but save for JDA Co’s wonderful publication on flood resilient detailing, rarely were architects or architecture discussed.2