The Architect's Newspaper

In late September 2022, a large hall in a former textile factory in Mexico City’s Colonia Doctores was festively decked out. For the uninitiated, the party appeared to be a bunch of people over 30 mingling, with drinks and a good sound system. But to anyone with some knowledge of the architecture world, it was an impressive assembly. Here in the same room were Mauricio Rocha and Alberto Kalach, perhaps Mexico’s most revered living architects, conversing jovially with peers and friends.

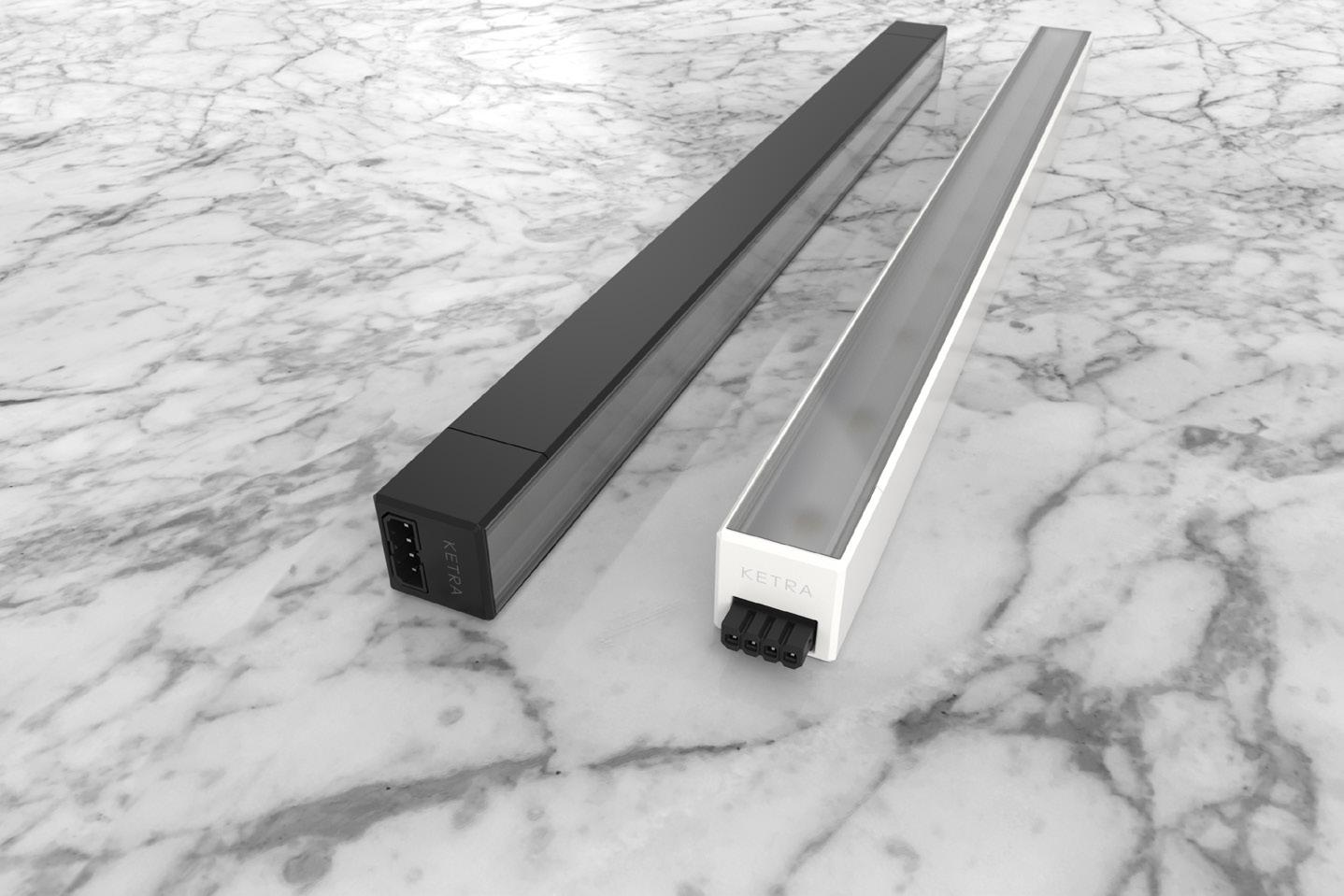

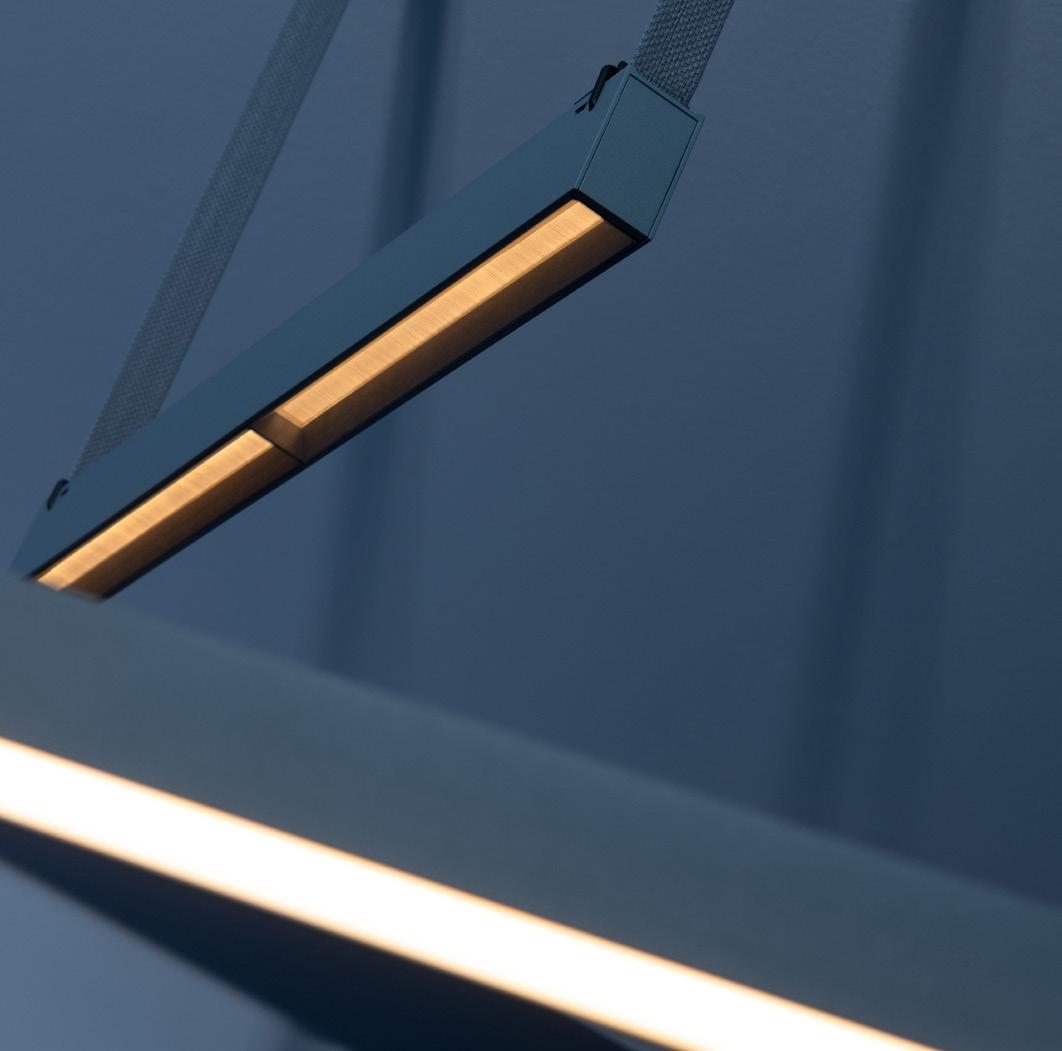

Tatiana Bilbao and Martino Stierli—the former was an honoree of the evening— were also present, as were rising and established architects from Munich, London, and Santiago. The lighting (courtesy of Lutron, a sponsor) was considered, the delicious menu created by a star chef, and the fluid, light ambience interrupted only by a few solemn speeches.

The starry affair was a testament to the prestige enjoyed by continued on page 12

In “When the Battle Is Over,” the introductory essay in the catalogue accompanying Young Lords and Their Traces, Theaster Gates explains that the genesis for the exhibition was the loss of two dear friends: curator, writer, and critic Okwui Enwezor and feminist theorist bell hooks. Gates states that with this exhibition, the New Museum temporarily becomes a site of mourning and communing but also mischief and conjuring. The show recognizes the recent loss of a roster of Black Young Lords, including polymath designer Virgil Abloh, theorist Greg Tate, painter Sam Gilliam, and ceramicist Marva Lee Pitchford-Jolly, in addition to Gates’s father, Theaster Gates Sr. It also marks the absence of other influences on Gates’s practice, such as film theorist Robert Bird, painter Agnes Martin, and artist Joseph Beuys.

The power of Young Lords is Gates’s transmutation of both loss and the museum itself. continued on page 49

The Embrace, by Hank Willis Thomas and MASS Design Group, opens in Boston page 9

The Embrace, by Hank Willis Thomas and MASS Design Group, opens in Boston page 9

The new Lincoln Center David Ge en Hall, designed by Diamond Schmitt and Tod Williams/Billie Tsien Architects, was decades in the works but completed ahead of schedule and under budget since the pandemic forced the closure of the Avery Fisher Hall.

The first priority was to improve and revitalize the acoustics inside the main theater, to make sure it was the best-in-class acoustic experience for the New York Philharmonic. What resulted is a completely new theater inside the building, not just a renovation, creating an intimate and inclusive experience for the audience.

Everything in the building, from door handles to floorboards to railings, feels reassuringly solid. Pulp Studio fabricated over 8,700 square feet of flat and curved, laminated glass railings, using an acid etch glass to meet the design aesthetic and provide an enhanced level of privacy. The bent glass was chemically strengthened for increased surface protection and Pulp Studio’s proprietary Precision Edge® technology was used on all the flat glass for a refined and professional look.

Social/Public Spaces: Tod Williams Billie Tsien Architects / Concert Hall: Diamond Schmitt

Photos: Michael Moran Glass: Lafayette Metal & Glass Company – Hauppauge, NY

Owner Rep: CMDC Consulting, LLC / Acoustics: a-‘ku-stiks/ Theatre: Fisher Dachs Associates

Mechanical/Electrical: Kohler Ronan, LLC

Cofounder and CEO

Diana Darling

Editor in Chief

Aaron Seward

Art Director

Ian Searcy

Managing Editor

Jack Murphy

Web Editor

Kristine Klein

Contributing Editor

Samuel Medina

Market Editor

Sophie Aliece Hollis

Associate Newsletter Editor

Paige Davidson

Interim Associate Editor

The first issue of The Architect’s Newspaper was published on November 10, 2003. It was characterized as a “soft launch,” but that issue set the tone for all that has followed, making 2023 for all intents and purposes the publication’s 20th year. We will be celebrating that milestone in grand fashion come November. In the meantime, it’s worth contemplating what’s changed in two decades of publishing the paper, as it is affectionately known internally.

In that inaugural issue, founding editors William Menking and Cathy Lang Ho wrote in this column that the idea for the paper had been born in part out of “frustration” over the dearth of design coverage in the mainstream media. The flurry of interest that surrounded the competition to design a new World Trade Center from the wreckage of the old only highlighted how little attention was given to architectural and urban projects beyond Ground Zero. Publishing in a tabloid format, with a biweekly schedule, the paper proposed to fill that gap with stories that reveal “how architecture gets built and how a city takes shape.” The sensibility, Menking and Ho proclaimed, was to be catholic, open to the broad range of topics that the design community ought to know to do its work. They even included a list of these topics, indicated as tentative by the inclusion of a question mark: “real estate, landscape, preservation, art, film, ecology, law?” Not to leave architecture itself out, they promised to keep readers informed about new projects, on the boards and coming out of the ground; profile local practices; indulge in gossip from around the design world; review new books, exhibits, and buildings; run listings of design-related events; and provide a platform for voices from the profession.

From that set of ingredients, it seems little has changed in two decades. But of course, so much has changed—not really in the types of things we cover, but certainly in the way that information is shared. While we still publish a tabloid, we no longer do so on a biweekly schedule. The drumbeat of the news is no longer kept by print’s timpani tap, but by the endless EDM of the internet. We disseminate ours online via archpaper.com, a veritable flotilla of email newsletters, and, of course, social media. The print edition of the paper, still a cherished object, comes out only seven times per year, bolstered by its biannual sister magazine AN Interior , which covers the world of interiors by architects, and the end-of-theyear Best Of issue that publishes the winners, honorable mentions, and editors’ picks of our three annual awards programs: Best of Practice, Best of Products, and Best of Design. Menking and Ho also said in their first editors’ note that the paper would be focused on the design community of the New York region. As the paper grew, it did so regionally, with print editions eventually dedicated to covering the West Coast, Midwest, and, finally, Southwest.

While we now publish a single national print edition (and often look beyond the continent for content), we continue to maintain regional focuses through our email newsletters. This regionality is a part of the paper’s DNA, realized by our openness to cover stories both global and local, as in our international economy, any regional focus must necessarily consider broader happenings.

Menking and Ho ended their first editors’ note with a hope that the paper would become a “platform for information, dialogue, and debate.” They also asked readers to “tell us what you think.” From my perspective, here on the cusp of AN’s 20th birthday, their hope has been fulfilled. But don’t take it from me. Turn the page—or if you’re seeing this online, keep clicking—read what’s on offer, and, as always, tell us what you think.

Aaron SewardIn 2003, Bill Menking and I never imagined that our seed idea of starting a regional architecture publication would succeed and grow into one of the world’s best-known architecture media resources. Bill brought the architectural history, and I knew branding, marketing, and finance. It proved to be a winning combination. When I look back now on the first issues, I remember the excitement of developing design ideas for print and websites, working from our loft in Tribeca, making huge efforts to make sure that AN was known wide and far, and scraping together money to cover operating costs and pay employees.

Many things about the business have changed since then, but the basic principle that we started with remains: AN covers the things happening in architecture and design that our AEC audience wants to know about! Over the past 20 years, our business has expanded to include the well-known Facade+ conference; AN Interior ; the continuing-education platform CE Strong; a technology conference, Tech+; and our awards programs.

Time has flown. Sometimes I cannot believe all the challenges we’ve weathered over the past two decades: ups and downs in the economy, the COVID-19 pandemic, and Bill’s death in 2020. I wish Bill could be here to celebrate this anniversary, because he loved architecture, finding the stories, going to parties and events, and keeping up with the gossip. He loved our readers and supporters.

I am still here, each and every day. I love the challenge of the business, and I appreciate the employees who have contributed their time and creativity to making us what we are today. I want to extend a heartfelt thank-you to all who have helped us make AN a success.

Stay tuned for exciting news about our 20th anniversary celebration in November. I hope to see you there. Diana Darling

Audrey Wachs

Vice President of Brand Partnerships (Southwest, West, Europe)

Dionne Darling

Manager of Brand Partnerships (East, MidAtlantic, Southeast, Asia)

Tara Newton

Brand Partnerships (Midwest and Canada)

Neill Phelps

Sales Manager

Heather Peters

Assistant Sales Coordinator

Izzy Rosado

Program Director

Marty Wood

Program Assistant

Chris Walton

Audience Development Manager

Shabnam Zia

Events Marketing Manager

Charlotte Barnard

Business Office Manager

Katherine Ross

Design Manager

Dennis Rose

Graphic Designer

Carissa Tsien

Associate Marketing Manager

Sultan Mashriqi

Marketing Associate

Anna Hogan

Media Marketing Assistant

Trevor Schillaci

General Information: info@archpaper.com

Editorial: editors@archpaper.com

Advertising: ddarling@archpaper.com

Subscription: subscribe@archpaper.com

Vol. 21, Issue 1 | January/February 2023

The Architect’s Newspaper (ISSN 15528081) is published 8 times per year by The Architect’s Newspaper, LLC, 25 Park Place, 2nd Floor, New York, NY 10007.

Presort-standard postage paid in New York, NY. Postmaster, send address changes to: 25 Park Place, 2nd Floor, New York, NY 10007.

For subscriber service: Call 212-966-0630 or fax 212-966-0633.

$3.95/copy, $45/year; international $160/ year; institutional $160/year.

Entire contents copyright 2023 by The Architect’s Newspaper, LLC. All rights reserved.

Please notify us if you are receiving duplicate copies.

The views of our reviewers and columnists do not necessarily reflect those of the staff or advisers of The Architect’s Newspaper.

AN’s Best of 2022 print issue mistakenly included the Churchill Meadows Community Centre by MJMA Architecture & Design as a Project of the Year finalist. The actual fourth Project of the Year finalist was the Church Hill North Community Hybrid by O’Neill McVoy Architects, seen in the image above.

The Invisible Wall - occasionally imitated, never equaled. Proven and tested since 1992, with over 60,000 units installed in over 60 countries. Featuring many beautiful innovations that you would only expect from Goldbrecht.

A cozy bar in East Hollywood by Design, Bitches is a cider lover’s dream. Hear something? Say something: eavesdrop@archpaper.com

Earlier this year, AN published reporting about the latest travails of Alejandro ZaeraPolo, including news about his pending lawsuit and online activities. Zaera-Polo, a former dean and architecture professor at the Princeton University School of Architecture, has registered his distaste for contemporary academia in two different courts: Last August, he filed a suit in Mercer County Superior Court against the Trustees of Princeton University, university administrators, and former colleagues Mónica Ponce de León, Elizabeth Diller, and V. Mitch McEwen, among others, alleging wrongful termination, breach of contract, discrimination and defamation, the creation of a hostile work environment, and other violations.

More recently, Zaera-Polo’s efforts are also being heard in the court of public opinion via a Twitter exchange with McEwen. In a multitweet reply to McEwen, Zaera-Polo led with an apology of sorts and encouraged his former colleague to publicly apologize for her comments in the Daily Princetonian . He added: “Lesson #1: free ride is over, from now

Already 2023 has yielded two improvements in architectural websites.

on white males answer back.”

After AN ’s article was published, ZaeraPolo chimed in on January 12 via Twitter to share his response: Despite not reaching out to him for a comment, AN did “a good job. Everything they write is true.” He continued: “In fact they have done such a good job that they disclose facts that are not publicly available yet. Which means that one of the architects’ defendants has been disclosing information to AN . To the Princeton legal team: you are leaking badly.” Reader, AN ’s sources only included publicly available information.

Zaera-Polo did offer a useful clarification. AN ’s reporting mentioned his Twitter profile picture, a Guy Fawkes mask from V for Vendetta , which has become a symbol for anti-establishment movements, including the hacktivist collective Anonymous. He stated that the mask “has been there since 2013, when I was dean at the SoA, and I organized a conference called ‘Anonymous’, to which, whether you believe it or not, I invited Mitch McEwen. So it was not personal, and it is not a vendetta as AN implies… .” Point taken.

Alma’s 904 North Virgil Avenue Los Angeles

323-522-3362

almasonvirgil.com

Design: Design, Bitches

Early versions of the fermented apple-juice drink now known as cider were being brewed before Jesus Christ was born. Its popularity has waxed and waned over the millennia, but by the 1980s, the historic beverage had gained a reputation as a “cheap loony juice for teenagers to glug in bus shelters,” according to pommelier Jane Peyton. Thanks in part to the craft beer revival and enthusiasm for gluten-free vittles, today cider is one of the hottest beverages in the U.S. market, with more varieties and flavors than ever before.

The cider revival is in full swing at Alma’s, a Los Angeles bar designed by local firm Design, Bitches that squeezes more than 100 ciders into a 558-square-foot storefront in Virgil Village. The noirish, monochrome dark interior, assembled from three shades of blue, puts the focus on gold and amber bevs from all over the world.

Should the eye wander, there’s a parrot tank over the bar and miniature town dioramas under the street-facing seating fashioned by Alma’s co-owner Lee Briante to admire. Decorwise, bright cider bottles and cans shelved from the bar counter up to the wood-paneled ceiling are the center of attention, especially as seen from the clubby backless chairs at the curved wood bar. The funky labels on display are complemented by a space-age chandelier over the bar

extension that sits across from a narrow, wallto-wall banquette lined with tables for two.

Although the space is small, it feels bigger and brighter thanks to diagonal mirrors in the corners that bounce outside light around, while the reed glass on the front door and one of the front windows keeps the coziness locked in.

“We were inspired by the quirkiness of the neighborhood and the owners to create a local bar steeped in references to East Hollywood past and present,” Design, Bitches cofounder Rebecca Rudolph told AN. “It was important to us that it be a world unto itself, brought to life through a monochromatic color palette and custom-designed pieces including three-dimensional dioramas, mirrors, and built-in furniture.”

Alma’s opened slowly and carefully, given the strictures of the pandemic. It quickly became a neighborhood favorite for its signature ciders as well as its hefty beer list and nosh, like cheese plates and mini waffles. “If you love getting drunk on cider, this is the best place in L.A.,” one Google review gushed. “So when the crushing weight of despair becomes too much to carry, head over to Alma's and find sparkling salvation in a bottle.” Audrey Wachs

Earlier this month, BIG debuted a new website. When announcing this update on Twitter, the firm noted that its original website was made during the 2000s Flash era. The new site marks the shift in the company’s direction since its founding. A statement on the website from Founder and Creative Director Bjarke Ingels said, “Our latest transformation is the BIG LEAP: Bjarke Ingels Group of Landscape, Engineering, Architecture, Planning and Products.” (Sustainability is listed on the page as one of the key disciplines of the firm, but this didn’t make it into the new acronym. �� )

True to the old website’s styling, where color-coded projects were represented by pictograms stacked in a Tetris-like, periodic table arrangement, each project on the new site has its own unique icon. The redesign also scuttles the Millennial loading screen, a display programmed in several iterations that spelled out “Loading” in block letters as a percent ticker below gradually inched up to “100%.” While the new site is an undoubted improvement that shows a serious portfolio of built and proposed work, the cheeky big.dk URL remains the same.

Herzog & de Meuron (H&dM) also has a new website design. At the top of the homepage page, site categories (news, projects, monographs) sit in solid oval bubbles above topics/subcategories (art space, sport, residential) in their own dotted-line ovals. On the old site, the menu was on the left side of the page, with projects in a nested menu.

H&dM’s website, topped with navigational “pills,” lands tiles in a grid, while BIG’s opts for the single-column approach. BIG uses custom icons for each project, while H&dM numbers everything in ascending order (they’re up to 578 so far). Beyond that, the home pages are mildly similar, with logos in black top-left and categories in the middle.

The sites compile hundreds of projects for design-forward companies that are now

XL operations: BIG has over 700 employees, H&dM more than 600. It appears that they’ve discarded their more oddball prior expressions for formats that are encyclopedic, professional, and handsome.

These improvements have Eavesdrop missing the early internet days of architecture websites. Who remembers the awkward art-project pages of yesteryear’s starchitects?

Alissa Walker wrote in 2010 that at the time only two of the most recent 15 winners of the Pritzker Prize had websites with “easy navigation and proper URLs.” Jean Nouvel Zaha Hadid, Renzo Piano, and OMA all had Flash-reliant websites that used “label-less maps, wordless grids, sketches and other graphic devices with rollovers as navigation, with no easy way to locate or share projects. Two sites took a full minute to load. One had–gasp!–a pop-up window. It was so 1998!”

In the 13 years since, some quick searches reveal that the situation has improved. Most extant offices have something , even if it’s a straightforward portfolio grid, and the more corporate outfits have massed impressive resources to showcase their work and tell their story. Holdouts remain. SANAA only has a single-slide placeholder. Amateur Architecture Studio doesn’t have a website, nor does Eduardo Souto de Moura. While Glen Murcutt also doesn’t have a website, there is a dedicated domain for his folio, a boutique treatment of his work published by 01 Editions. (The cheaper version is ~$1,250 plus shipping.)

Peter Zumthor, that Luddite, still doesn’t have an online presence. Zumthor.org is operated by one Thomas Bjørkan, who writes: “As an admirer of his works I found it suprisingly [sic] difficult to find good and coherent information online, so I decided to try and make his works more accessible through this private project.” A fan-curated Instagram account of Zumthor’s work has over 114,000 followers.

It’s now 2023. It seems the role of a website for an architecture office—much like that of a monograph or even a building—is in flux, just like everything else.

Snøhetta taps its Norwegian roots for an open-air museum in Iowa. Portland Museum of Art selects LEVER Architecture to design its campus expansion project.

Vesterheim in Decorah, Iowa, houses one of the largest collections of Norwegian-American artifacts, so when the cultural institution was looking to revamp its campus, it naturally selected Norway- and United States–based architecture firm Snøhetta. Vesterheim translates to “western home” in Norwegian, a fitting name for a location that shares the histories and details of Norwegian-American culture and immigration in the U.S. The campus comprises several historic buildings, many of which were built by Norwegian immigrants, as well as facilities for the National Norwegian-American Museum and Folk Art School.

The institution’s history and origin trace back to Luther College in 1877. Laur Laursen, the university’s president at the time, began collecting everyday objects from Norwegian immigrants who had settled in the area. His successor, C. K. Preus, turned the growing collection into an open-air museum, showcasing both objects and buildings.

“As a Norwegian-American company, Snøhetta is grateful and excited to play a part in recontextualizing the experiences, art, and crafts of Norwegian immigrants here in Iowa,” Craig Dykers, Snøhetta founding partner, said in a statement. “We hope and expect that The Commons and Heritage Park will create new opportunities for considering and understanding the experience of immigrants to the United States.”

Snøhetta produced a master plan for the site in 2019 that brings together the extant facilities and buildings with a plan for a “unified campus.” Among the additions to the site are a new 8,000-square-foot building dubbed The Commons and a series of green spaces, part of Vesterheim’s reimagined open-air museum, Heritage Park. The additions are respectful in their scale and materiality so as to match the existing historic structures.

“We began working with Vesterheim in 2018 to envision a campus master plan that reunites and enhances the museum and educational facilities through a memorable campus landscape,” Snøhetta partner Michelle Delk explained. “By adding new out-

door gathering areas that extend Heritage Park to Water Street, Vesterheim Commons creates new interior and exterior public spaces where people can come together to enjoy the museum’s vibrant collections.”

The Commons takes cues from the surrounding wooded landscape. Its mass timber frame will be constructed using wood sourced from Albert Lea, Minnesota, and will be complemented by a brick volume sourced from Adel, Iowa. At street level a wood canopy with a sweeping curvature will shelter the all-glass lobby volume while also creating a striking point of interest.

Within the lobby, windows surrounding the interior will provide views out to the streetscape and the abutting wooded landscape. At the center of the atrium, a woodclad oculus bathes the interior in natural light. The space doubles as an event venue and has passageways leading off to the Westby-Torgerson Education Center and Vesterheim’s Folk Art School.

On the upper floors of The Commons, exhibition spaces will be equipped with digital facilities and a production studio. Galleries on the second floor will accommodate a study room envisioned to work in tandem with the new technology to augment researchers’ experience with Vesterheim’s collections.

Minneapolis-based landscape firm Damon Farber worked with Snøhetta to revamp the green space for Heritage Park, making it an “urban woodland” with scenery that references Norwegian forests and the Driftless Area, a topographical and cultural region in the Midwest comprising northeastern Iowa that lacks glacial deposits known as drift because of a lack of ice coverage in the last ice age.

The reimagined landscape was completed in August 2021 and features permeable pavers, native plantings, and a runoff mitigation and stormwater management system. As for The Commons, construction kicked off on the building in 2022, and Snøhetta anticipates completion this summer. Kristine Klein

The Portland Museum of Art (PMA), a Mainebased art and cultural institution, has selected the team led by LEVER Architecture to realize The PMA Blueprint, a plan that will more than double the size of the 140-year-old museum located in downtown Portland.

The Campus Unification + Expansion International Design Competition, managed by Dovetail Design Strategists in partnership with the PMA, was launched in June 2022 and garnered over 250 submissions. The submissions were whittled down to four finalists: Adjaye Associates, MVRDV, LEVER Architecture, and a team co-led by Toshiko Mori Architect, Johnston Marklee, and Preston Scott Cohen. The four schemes were unveiled to the public in November, entered a public comment period, and were ultimately evaluated by the design jury, with LEVER’s team coming out on top.

The $100 million PMA Blueprint project comes in response to record museum attendance, a diversified collection, and community feedback. Design competition guidelines asked for submissions to most importantly consider inclusivity. The winning design would be one that considered the campus in its entirety but also thought about the larger city and the state of Maine, with a goal of being inviting for all the museum’s communities.

“We were fortunate to be able to respond to a brief that looks at a museum in a way that foregrounds community and thinks about flipping the narrative of how we traditionally think about museums. That was the original brief: How do you create a museum that’s about art for all?” LEVER Architecture cofounder Thomas Robinson told AN

LEVER tapped a team of codesigners and community resources including Simons Architects as executive architect; Unknown Studio as landscape architect; Once-Future Office as signage, graphics, and wayfinding consultant; Studio Pacifica as accessibility and universal design consultant; and a team of engineers and project consultants including Atelier Ten, Guy Nordenson and Associates, Thornton Tomasetti, Altieri Sebor Wieber, Arup, Woodard & Curran, Simpson Gumpertz & Heger, Stuart-Lynn, and Openbox.

Also among these consultants was Indigenous Inclusion Adviser Chris Newell, a Wabanaki consultant from the Akomawt Educational Initiative. The Wabanaki people occupy much of the Indigenous-owned land in Maine. In conversations with Newell, LEVER observed the deep connection the state of Maine and the Wabanaki have with “celestial bodies,” in particular their engagement with sunrise.

“Chris Newell, our Wabanaki adviser, talks about Maine being the ‘Dawn Land’ that the Wabanaki people have inhabited for the last 11,000 years; their focus has been to greet the dawn, and that’s been integral to their culture,” Robinson continued.

To replicate this phenomenon within its design, LEVER has proposed a timber addition with a scooping roofline curved to align with the sun’s positioning on the summer solstice. Similarly, during the winter solstice, the sun beams through the facade facing Free Street and Spring Street, allowing light to enter the museum complex through Congress Square and a new cutout arch on the Pei Cobb Freed–designed Payson Building.

LEVER’s scheme doesn’t just expand the museum by an additional 60,000 square feet, offering more public and gallery space: It will also unify the campus, currently marked by four disparate structures built in different centuries in varying architectural styles. The new archway through the existing Payson Building toward Congress Square will allow visitors to circulate into the sculpture garden, bringing the city into conversation with the entire museum campus.

While LEVER’s plan underwent public comment and a jury review, it is still very much a work in progress, with design and material decisions still to be made. The firm is eager to source timber and terra-cotta for the PMA within Maine.

Robinson noted: “There’s an incredible amount of momentum in the Northeast around sourcing regionally. I think this building could be a catalyst for moving that forward.”

In addition to considering low-carbon building materials, LEVER’s scheme includes a closed geothermal loop system that will harvest heat from deep within the earth.

By creating a seamless circulation pattern from the street through to the buildings and the interstitial locations staged throughout, the entire campus will become more connected and flexible. Large glazing installed within the addition allows visitors to see into makerspace studios and community galleries, and a rooftop deck offers a place for hosting events, staging art installations, or observing the serene landscape below.

“We want to sort of create a design where you can see yourself in the museum and can see activity happening. You can see people sitting on the terrace, and you would actually say, ‘Hey, that’s a place that I feel like I belong, that’s really part of my life and the community as a whole,’” Robinson said. KK

At the end of 2022, Cathleen McGuigan stepped down from the role of editor in chief of Architectural Record, a post she had held since 2011. Josephine Minutillo, who has been with the publication since 2001, has now taken over the job. To celebrate this changing of the guard at the U.S.’s oldest continuously publishing architecture magazine, AN’s editor in chief Aaron Seward spoke with McGuigan to discuss her career, the state of architecture, and her plans for the future. Their conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

tor in chief job in 2011. I was able to bring experience both as a journalist covering the field and as an editor, managing a staff.

AS: It’s interesting that you started at Newsweek, which is obviously a general-interest publication with a broad readership, and then moved to Record, which is a specialized publication with mainly an audience of architects. Did that affect the way you approached journalism? Or do you feel like there was a continuum in terms of the way you cover the subject?

ties of color and how little representation people of color have in the profession.

AS: From our point of view at AN, there’s also a desire to have more representation from different voices in architectural journalism and criticism. Do you see that that’s changed much at Record?

Aaron Seward: Some of our readers might not know you or your background, so could you give us a brief history of how you got into design journalism?

Cathleen McGuigan: After college, I began freelancing for newspapers and little magazines. Then I came to New York and worked at Newsweek , which was great training in journalism. I started as a researcher for the art critic and the architecture critic. I liked interviewing architects because they were good talkers—they have to know how to sell their projects to clients, and in that way aren’t like artists, who often can be at a loss for words. And though I continued to write about various aspects of culture, I kind of revived the architecture beat at the magazine, long after the old critic had left.

I spent a year at the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD) as a Loeb Fellow and learned so much more about the field—before that, I used to say that I was practicing architectural journalism without a license. At the GSD, I could indulge in my longtime interest in the evolution of cities and in urban design. I wrote a series of big stories on cities for Newsweek, such as Barcelona preparing for the ‘92 Olympics, and the transition of Berlin from a divided city to the new capital of a united Germany, exploring not only new architecture but how the politics and history of Germany would be reflected in the renewed city. And then for seven years I was also the arts editor, running all the cultural coverage.

I knew Architectural Record, of course— and felt very honored to be offered the edi-

CM: Both. We absolutely have a primary audience of architects, and what we write is at a more sophisticated and professional level than what I did at Newsweek , where, as you say, I was explaining architecture and urbanism to a more general audience. At Record we focus, of course, on what matters to architects, such as structure and materials. That was a learning curve for me. The first piece I wrote for Record was on the Rothschild Bank in London designed by Ellen van Loon of OMA. I was going to be edited by Suzanne Stephens; she is a great editor, and though I was technically her boss, I was terrified I was going to say something stupid or get something wrong. I really worked on reporting the details of the structure and the construction, which was interesting because the building is inserted into an almost impossibly tight site behind a beautiful little Christopher Wren church. It was fun to write about, but challenging because we have such high standards for getting everything right. I brought wider journalistic interests to Record too. I was thinking about identifying trends in the field and also about the larger context of architecture and the question of how we could bring the social and political aspects that surround building to our readers.

AS: Where did you find the architecture profession when you started editing Record? How have you seen the profession change over these years?

CM: In the last decade, we’ve been living through an interesting period in architecture where concerns about urbanism, social issues, and sustainability have grown dramatically. When I was writing about architecture for Newsweek in the late 1980s, critics were mostly writing about buildings as objects, and architects were designing buildings as objects. And though they still are—and that’s fine—our values have changed. Not just in terms of energy savings but also considering the embodied carbon of materials, how design and construction affect the climate crisis, and how architects can have a positive impact. Equity of the public realm and the idea that design is for everybody is something that the whole profession has become more conscious of. We have extensively covered women in architecture, and though I think we’ve not seen enough change, there is still quite significant progress for women advancing in firms and in closing the pay gap, especially after the #MeToo movement erupted. And after the murder of George Floyd in 2020, we had a whole new movement looking at how poorly architecture often serves communi-

CM: I feel that the young journalists really help refresh our vantage point. One of our young reporters actively covered the architecture unionization movement, and she and one of her peers are especially sensitive to issues of gender and race. This is what’s so great about having a robust website. On the one hand, we’re putting out a monthly magazine that’s very carefully considered, and at the same time we’re essentially running a daily newspaper online, and this gives us the ability to cover a wide spectrum of issues, news, and terrific architectural projects.

AS: You came from a world of strictly print, and now we’re in this hybrid world where print is still relevant but digital has taken a huge part of the market share. How do you see these two platforms functioning together today?

CM: They function together, but the biggest challenge is how to better knit them together. Our print issue is still the anchor of what we do. Our owners and our publisher want that. But we have many, many more eyeballs online globally, and that’s very exciting. One of the challenges is when you do certain classic magazine features that might have several pieces to them, how do you present all that content in a digital format so that relevant stories are linked together but it’s not a 5,000-word read? That’s one thing that we’ve been working on and is sure to be a priority going forward for the next editor, Josephine Minutillo—who is great, by the way.

AS: This sounds like what we discuss at AN Speaking of which, in our chat earlier you spoke of Record and AN as “friendly competitors.” Obviously, Record is over 130 years old and AN is just turning 20, but what is your perspective on our publication?

CM: The Architect’s Newspaper became essential reading from the moment it appeared because it is a newspaper, with a wide range of coverage about firms, practice, trends, as well as projects—and gossip, let’s not forget about gossip! I really liked and admired your cofounder Bill Menking for all that he did.

AS: What are your plans now after stepping down as Record’s editor in chief?

CM: I’m going to continue as a consulting editor, and I will continue to run Record ’s Women in Architecture Forum & Awards, which we started nine years ago. I’m very proud of the fact that we honored Carol Ross Barney as Design Leader last October and two months later AIA gave her the Gold Medal; I feel like we’ve been ahead of the curve. We give five awards annually, so at this point it’s a fascinating group of 45 terrific architects doing a variety of really interesting work.

I also have my own independent writ -

ing projects. And I want to continue to be an advocate for some of the areas that we focused on at Record , especially affordable housing, which we all know is at a crisis point. There are solutions in other parts of the world that we find very difficult to bring to the U.S. Obviously, it’s not just a matter of architecture, it’s also a matter of policy and economics, but thoughtful design can have a powerful role.

AS: Could you speak a little bit about the value of having a global perspective when you’re covering architecture?

CM: It’s absolutely essential. It can be really inspiring, if you are trying to design affordable housing in the U.S., for example, to see some of the projects that come from France, Finland, or the Netherlands, where architects manage to create beautiful, humane housing that’s not super expensive. We’ve seen some fantastic architecture come out of China recently. We’ve seen interesting projects come out of Latin America. And we’re turning our gaze toward Africa, which is so exciting, because it’s a part of the world most of us know so little about. The upcoming Venice Architecture Biennale, curated by Lesley Lokko, founder of the African Futures Institute, will be especially interesting, I think. It’s very positive for architects— young architects in particular—to see a whole range of buildings and a variety of viewpoints. And that is the most exciting thing about covering architecture today.

AS: That loops back to our earlier discussion about considering urban and social contexts when we review individual projects. It’s certainly what makes this world of architectural journalism exciting to me: the idea that architecture is something that touches us all and we all have the authority to assess it, to judge it, and to find different things about it that delight us as well as make us upset. Long live architectural journalism.

CM: Carol Ross Barney said that she likes doing public projects not only because she’s an architect but because she’s also the client. She’s part of the public. She’s a citizen. I think that we journalists reflect that audience too—the audience that is in architecture and that is for architecture.

A new sculpture and plaza on the Boston Common honors Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s life and legacy.

MASS Design Group, in collaboration with the City of Boston and local nonprofit Embrace Boston, has unveiled a sculpture and supporting landscape on the Boston Common honoring civil rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

The Embrace, an artwork by Brooklyn artist Hank Willis Thomas, sits in the middle of the 6,000-square-foot 1965 Freedom Rally Memorial Plaza, a circular area decorated with over 1,300 granite stone pavers arranged in a quilted star pattern symbolizing collectivity and unity. The pattern responds to a passage from King’s 1963 Letter from Birmingham Jail about how people are “tied in a single garment of destiny.”

Close to the sculpture, the ground rises and falls to create circular seating near The Embrace for visitors to reflect on King’s activism and message. A wall encircling the plaza features a quote from King’s wife, Coretta Scott King.

MASS worked with Embrace Boston, which honors and advances the work of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Coretta Scott King, on the plan for the sculpture and surrounding plaza, which is located in Boston Common.

Solicitations for the project began at the end of 2017, when Embrace Boston put out a request for proposals for a public monument. In March 2019, it chose The Embrace, a proposal from Willis Thomas, out of more than 100 submissions. In 2021, the Boston

Art Commission voted to approve the final design of the memorial.

“The Embrace is a testament to what we can achieve when we come together,” the artist said in a press release. “The sculpture embodies people’s capacity for love, change, and hope for the future.”

The massive 38,000-pound, 20-by-25-foot bronze sculpture depicts the way the Kings held each other after Dr. King won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964. Made from more than 600 individual pieces, the sculpture is the first new monument on the Common in over 30 years.

A bronze plaque erected within the plaza honors 64 of Boston’s civil rights leaders who joined Dr. King in the fight for equality and civil rights.

Martin Luther King Jr. and Coretta Scott King met and married in Boston while they were students. A little over a decade later, on April 23, 1965, Dr. King stood on the Common to address a crowd of 22,000, calling on the city and its leaders to live up to its highest ideals.

“The Embrace will be a revolutionary space in our country’s oldest public park for conversation, education, and reflection on the Kings’ impact in Boston and the ideals that continue to shape the fabric of our city,” Mayor Michelle Wu said in a press announcement.

Martin Luther King III shared via a press release that his “parents’ time in Bos-

ton is regularly a forgotten part of their history—and the history of the movement they helped inspire. The Embrace is a commemoration of their relationship and journey and represents the meaningful role Boston served in our history.”

of Destiny, with the Kings surrounded and uplifted by local civil rights heroes from Boston, it’s the scale, the optimism, the authenticity, the honesty of it,” MASS Design Group principal and lead architect Jonathan Evans added. “You can’t help but feel something. You can’t help but want to actually do something about it. It’s a call to action.” AW

Feature Walls in Modular, Glass-Reinforced Gypsum. Over 60 designs!

At the corner of Montgomery and Washington streets, the shadowy wind tunnel of San Francisco’s financial district suddenly opens and the historic neighborhood around Jackson Square begins. The buildings drop down to two, three, and four stories, and an earlier architectural pattern of brick, stone, and wood-framed windows replaces concrete and steel. Two quiet blocks up, 840 Montgomery has been home to William Stout Architectural Books since 1984. On the December day I met Bill Stout and Erik Heywood there, jazz played amid the floor-to-ceiling stacks and tables spread with books. Stout and Heywood were behind the counter, looking at blueprints of Le Corbusier’s Villa Roche that the latter had brought from the former’s warehouse. The long-running store is going strong, but it now operates as part of the Eames Institute of Infinite Curiosity.

In October 2022, the organization acquired Stout Books, an act that followed its purchase of his personal collection of over 4,000 architectural monographs, books on history and theory, and graphics. The institute, led and curated by the Eameses’

granddaughter Lisa Demetrios, exists to preserve the Eames Ranch in Petaluma and its collection. “The reason for the acquisition is preservation. Stout Books is spiritually attached to our mission for how it contributes to the world of architecture and design,” Heywood told AN. As the institute’s retail director, he’s helming the bookstore, drawing on his experience as the founder of the Oakland-based Book/Shop. Going through the Eameses’ materials at the ranch, Heywood realized that their design process began with models and mock-ups. They made things first, and the drawings came later. “We love the idea that as a designer and an architect, you still have permission to roll up your sleeves, get out some colored paper and a pair of scissors, and go to town,” he said. An enormous amount of care and creativity wove through everything the Eameses did: When they wrote a letter, it was handwritten, collaged, with drawings. “Going there you see a soulful, heartfelt imagination that’s often missing now in design practice. Bill’s bookstore is very much in that spirit.”

Bill Stout began collecting architecture books in the 1970s to build his own library, assuming other architects would want the same. Over the past 48 years, across multiple Bay Area locations and branches of work, he has curated a vast collection of books related to architecture, all facets of design, and planning with an architect’s sensibility.

Stout first began selling out of an apartment he shared with friend (and now renowned architect) Steven Holl at 1218 Montgomery; they were open at midday so architects could come by at lunch. It was just new books at the time, sourced from Europe and the first publisher he carried, Futagawa, from Japan. Chuck Bassett in SOM’s San Francisco office soon became Bill’s biggest patron. He was building a library at work and didn’t want his library committee spending too much time at Off Center—as Stout and Holl called the bookstore then—so he asked Stout to bring down a box of books every two months for them to consider and selectively purchase.

Returning from one such delivery, Stout spotted what would become his first real shop on Osgood Street. There was a beautiful garden in the back and an apartment above that he lived in—like Off Center and the Jackson Square basement where we spoke. He began adding out-of-print books and buying libraries, beginning with an incredible collection of Frank Lloyd Wright from a German professor then teaching at the University of Washington. At that time, he remembered that “there might have been 50 to 80 architectural offices—and probably ten or so just in the area. There was a lot of traffic.” He was at the epicenter of paper architecture—a movement of architectural writing and thinking that was

Starting in the early 1990s, Stout published books and research materials under his eponymous imprint, focusing on local architects and regional architecture, “things that might not get covered by the New York press.” He worked with Marc Treib on a series of titles drawing on the archives of UC Berkeley’s College of Environmental Design on architects like Bernard Maybeck, Joseph Esherick, and Garrett Eckbo. Among the last books he did was a monograph on Donald Olsen by Pierluigi Serraino and another by Dung Ngo, William Turnbull Jr.: Buildings in the Landscape. Jill Stoner’s Poems for Architects, based on the author’s use of poems as project prompts for her architecture students, is another one Stout likes to cite.

“We were rolling right along,” Stout recalled, “and then Amazon blew us out of the water.” Still, he held on, maintaining his price structure and approach, even as the coterie of independent bookstores in the Bay Area and around the country dwindled.

“There aren’t a lot of places where you can really dig into and explore design anymore,” Heywood said. When Stout’s library and his bookstore were in danger of disappearing, the Eames Institute entered the picture in the role of a preservationist

at its height. Susie Coliver from ARCH Art & Drafting Supply moved in next door; Dan Friedlander opened Limn nearby; and Andrew Batey, Mark Mack, and others started Archetype magazine. He helped Peter Eisenman of the Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies in New York when IAUS put the Bay Area on its lecture circuit and sold its journal Oppositions and its books. By the time he moved to the current location, the neighborhood had changed—lawyers replaced the architects—and his own collection and activities were expanding. From early on, Stout sent out extensive catalogs in the mode of Wittenborn to clients worldwide and the 200 libraries he stocked. Stout also wrote essays to preface the catalogs he did over the decades. Those essays are among the things that the Eames Institute hopes to resurface from all the work Stout has done over the years. “There is so much there,” Heywood said.

seeking to keep the bookstore and library intact for researchers and people interested in architecture and design. “Having the Eames Institute involved is more of a hands-on process—experiences that can seep into people’s design thinking and practice—rather than a school where you are learning things in a very rational way that never works,” Stout explained.

For him, the acquisition is a perfect fit. “The institute now has a place in the city where they can have lectures and exhibitions. My libraries reinforce their attitude toward an institution that can research not only industrial design and design thinking but also architecture. And that is a pretty exciting idea, especially here in Northern California, because there isn’t anything like that.”

“Optimism is at the heart of the Eames Institute,” Heywood noted. “In the world right now, design needs optimism, interaction, and happiness to breathe new life into it. Our hope with what we are doing at the institute and this bookstore is that there is a flame that we keep going.”

Architecture Sarasota explores tropical modernism in search of key lessons for addressing the climate crisis.

There’s no question that climate change is intensifying. If we’re not experiencing a record-breaking deep freeze in the winter, we’re dealing with scorching heat waves. One of the most serious outcomes of this ecological crisis is the growing number of powerful storms we’re witnessing.

Nowhere is this more evident—at least now—than in the low-lying coastal areas of southern Florida. Last September, Hurricane Ian wreaked havoc on the state’s western seaboard and left a whopping $50 billion of damage in its wake. Though predicted to sustain the worst of the impact, the midsize city of Sarasota was miraculously spared.

Situated between Tampa Bay and the Fort Myers–Naples metro area, the mini-metropolis serves as a cultural hub for the region. Made famous in the early 20th century for its connection to the circus industry, the city currently boasts a number of performance venues and museums that cater to a mostly, but not exclusively, retired population originating from the Midwest.

However, the coastal town is best known for having served as the center of what became known as the Sarasota School of Architecture. Renowned practitioners like Ralph Twitchell, Jack West, Victor Lundy, and perhaps most famously Paul Rudolph enacted their own versions of modernism within the city proper and its outlying barrier islands from the 1940s to the ’60s. Through various—and at times opposing—methodologies, these established and budding practitioners created buildings that translated International Style principles to a subtropical climate. Key to this output was the philosophy of industrial functionalism put forward by the Bauhaus but also the more place-based ideology demonstrated in Frank Lloyd Wright’s Usonian typology.

Homes, schools, and even beach clubs were constructed with integrated overhangs for better shading, open layouts for

more flexible use, and pilotis to safeguard against potential flooding. Arguably, the most critical characteristic of the 50 or so structures erected during this period was the concept of bringing the outdoors in. This overarching strategy ensured that buildings could not only facilitate ample ventilation—in a time before air conditioning was widely accessible—but also remain permeable and, in turn, resilient to the unpredictable forces of nature.

Thanks to preservation efforts made in part by recently established not-for-profit Architecture Sarasota, iconic sites like Rudolph’s groundbreaking Healy Guest House (Cocoon House) remain intact today. Built in 1948, the bungalow first gained recognition for its innovative integration of an inverted catenary roof but also its seamless connection to the Bay Isle canal it abuts. Other exemplary properties he designed and that have since been restored include the model Revere Quality House and a monumental addition to Sarasota’s central high school. Real estate developer Philip Hanson Hiss III was instrumental in supporting the movement by establishing the Lido Shores development, a reclaimed sandbar that became a sort of canvas for many of the aforementioned architects’ revolutionary ideas. Some of their experimental designs are still standing in this tight-knit island community, albeit next to bulging Tuscan-style McMansions.

Seated in the downtown Sarasota School–era McCulloch Pavilion, the organization hosts exhibitions, conferences, and the annual SarasotaMOD Weekend. Anchored by ticketed home, trolley, and kayak tours, the festival wraps up with a thought-driven conference that always draws back to this rich local heritage. The most recent edition—held from November 10 to 13, 2022—focused on the topic of tropical modernism and the relationship between climate and design. The theme was relevant not only given recent events but also the announcement of Morris Hylton

III, the former Historic Architect for Climate Change at the National Park Service, as Architecture Sarasota’s new president.

“The organization’s purposefully bifurcated but interrelated mission resonates with who I am and the driving force of my 25-plus-year-old career: preserving the past and cultural heritage to inform the present and future,” he told AN. Though a Kentucky native like Rudolph, Hylton has taken this new appointment as a kind of homecoming.

It was on a trip to Sarasota with his parents 40 years ago that he fell in love with architecture and its historical significance.

After studying at Columbia University, he became a strategic initiatives manager for the World Monuments Fund, an NGO tasked with saving endangered cultural heritage sites around the world. He helped create the Modernism at Risk project dedicated to addressing the specific challenges of preserving modernist architecture.

He also spearheaded the Restoring a Sense of Place initiative in New Orleans and on Mississippi’s Gulf Coast to recover historic buildings and communities affected by Hurricane Katrina. “I experienced firsthand that the region’s shotgun houses, Creole or American cottages, and other coastal structures that retained their original designs and materials were the most resilient and more easily recovered.”

Hylton soon formed an interest in climate-responsive design as well as preservation. “I realized that regional movements of modernism like the Sarasota School of Architecture were inspired, at least in part, by the vernacular designs of the South,” he adds. “For example, Paul Rudolph’s Umbrella House (1953) in Lido Shores is a modern version of the dogtrot-type residence that has a central breezeway to promote cross-ventilation.”

After bringing this dynamic perspective to roles at the National Park Service and the University of Florida in recent years, taking on his new position at Architecture Sarasota has allowed Hylton to come full circle: “Our mission is to conserve the legacy of the Sarasota School while sustain-

ing that continuum of innovative design and providing a forum that encourages forward-thinking architecture on a regional, national, and even global scale.”

Complementing a comprehensive exhibition on view through February 25, Hylton programmed the 2022 Sarasota MOD Weekend Tropical Modernism: Climate and Design symposium with this vision in mind. Looking at how shared environmental conditions across the Global South have influenced both aesthetic and functional design decisions, speakers like Dr. Vandana Baweja explored the implications that colonial constructs have had in this context. While Dr. Sonia Chao looked at the historical correlations between southern Florida and Cuba in addressing climate challenges, Dr. Daniel Barber explored the history of air-conditioning in defining our expectation of comfort and how cooling solutions for our interiors that emit less carbon could be derived from buildings constructed in Florida, West Africa, and Brazil.

One of the main takeaways from the conference was that these practices could be introduced beyond the tropics and subtropics. As the climatic regions ultimately extend farther north and south, there will be a growing need for new cooling solutions. Overall, there was a consensus not only that tectonic strategies such as overhangs, raised volumes, and slatted windows could help alleviate extreme heat but also that the use of vernacular and Indigenous knowledge could play a significant role.

In a final audience Q&A session, Barber offered up an additional proposal. For him, as climate change and the migration it will undoubtedly induce worsen, architecture might become less concerned with creating structures anew and more focused on radical adaptive reuse through tasks like transforming existing structures into ones that can quickly accommodate displaced peoples. Hylton agreed: “The greenest buildings are the ones already standing.”

In Mexico City, LIGA celebrates its first decade of producing architectural discourse and settles in to its new space at La Laguna.

continued from cover LIGA, the small notfor-profit organization whose tenth anniversary the party served to celebrate. The platform—officially LIGA, Space for Architecture—launched in 2011 as Mexico’s first independent venue dedicated to promoting contemporary Latin American architecture through exhibitions and conferences.

LIGA was created by PRODUCTORA (the architecture practice led by Carlos Bedoya, Wonne Ickx, Victor Jaime, and Abel Perles) and Ruth Estévez, who felt that their hometown—and Latin America in general—lacked a space where the concerns and themes animating the region’s practices could be laid out and discussed freely. The group aimed to forge connections with colleagues from Guatemala to Tierra del Fuego, address essential questions affecting their profession, and construct a locally rooted architectural discourse. Importantly, LIGA’s founders hoped that by defining where Latin American architectural production stands from within, they would help balance foreign assessments that were often condescendingly clichéd.

In its early years, LIGA’s operations were shaped by its idiosyncratic location. Until 2017, LIGA’s nominal home was a 160-square-foot trapezoidal space with big strip windows on the street level of a paradigmatic modernist tower designed by Augusto H. Álvarez and Sordo Madaleno in the late 1940s. (LIGA was named after the Bible league that previously occupied the commercial space.) From the start, the magic of LIGA’s straightforward program was the way it made an asset out of its restrictions. Every three months, a different emerging architect or architecture office from Latin America was invited to design a mini-exhibition for the peculiar space. The brief was both simple and limiting: The site-specific installation had to elaborate on an idea crucial to the architect or firm’s practice yet avoid presenting the studio’s work too literally. Plans and maquettes were discouraged in favor of brainy explorations of themes like permeability, water, and manual labor.

As one would expect, the 35 exhibitions showcasing architects from 13 countries that LIGA has hosted so far have varied in legibility, wit, and overall success. Some architects are better than others at extrapolating key threads of their work to a setting where a compelling and concise—yet large-

ly abstract—exposition is paramount. The main formal challenge is how to exhibit architecture without showing architecture.

LIGA’s inaugural exhibition set a high standard for everything that has followed and remains one of its most influential to date. Conceived by Pezo von Ellrichshausen as a play on scale, spectatorship, expectation, and representation, it offered one possible template for presenting architecture conceptually without resorting to photographs by Iwan Baan or models—well, at least not the models one would expect. In fact, Pezo von Ellrichshausen did construct a miniature building, a fictive “museum,” in LIGA’s gallery. The studio’s proposition referred to the elephant in the room, an inherent dilemma that has been around as long as architecture exhibitions: If the architectural object itself is invariably a representation and, by necessity, absent, how does one represent it in an exhibition? And, by extension, does or should one even try to represent it at all?

The following year, the Brazilian architect Carla Juaçaba distilled her architectural thinking, specifically the idea of equilibrium, into a poetic installation that delivered the kind of forceful statement LIGA hoped to elicit: Juaçaba developed a topically relevant theme present in her work—the notion of physicality and tension, expressed here through long metal elements delicately suspended in midair with magnets—and inserted it into a transnational conversation among architects and anyone interested in the intellectual framework of building design today.

Over the years, other architects have reacted to LIGA’s space in original ways. Some decided to negotiate the unique situation of LIGA’s first home between two much-transited streets (and on the border between the culturally rich, dynamic neighborhoods of Condesa and Roma) by incorporating that traffic into their exhibition proposal. Openings not only spilled onto the sidewalk but continued in PRODUCTORA’s office on the ninth floor and in the building’s penthouse, where ancillary activities like talks took place. The social impact of these activations of public and private space can’t be underestimated, as they offered a valuable forum for cross-pollination to architects early in their careers used to working in isolation, with little knowledge of what preoccupies a fellow

young architect in, say, Bogotá or Lima. As a result, both concrete and virtual networks were created. (Every exhibition is accompanied by a text commissioned by the invited architects, adding another layer to the web.)

The platform’s prescient curatorial vision is evident in the roster of architects who have participated. For its sixth exhibition, realized in 2012, Frida Escobedo—at the time a largely unknown talent—tackled notions of cultural identity and questioned the purported neutrality of the modernist glass boxes that are ubiquitous in the Mexican capital. Escobedo’s exploration was typically astute and thoughtful, and the architect reprised the investigation behind her LIGA exhibit in subsequent projects. Regarding the impact of this show on her trajectory, Escobedo shared with AN:

My LIGA exhibition came at an important moment in my career. I had just completed a pretty theory-focused master’s program [at Harvard GSD]. My return to Mexico was a return to reality. I was asking myself how to produce architecture while continuing to question it. Showing at LIGA helped me with that transition—it allowed me to present more conceptual ideas while becoming re-entrenched in my day-to-day work life. The experimental nature of the exhibitions forces you to really distill and analyze where your practice stands, and the conversations that take place around the exhibition itself are particularly enriching. That platform to question what you’re doing, and get clarity and feedback about the direction you’re taking, is what makes LIGA so valuable.

Currently Escobedo is designing the modern and contemporary art galleries in the Oscar L. Tang and H. M. Agnes Hsu-Tang Wing for the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Being featured at LIGA has become an aspirational milestone for studios throughout the region. “Exhibiting at LIGA was a dream that became a reality [last] year,” said Fernando Martirena, whose Havana-based firm Infraestudio, founded and directed with Anadis González, is the subject and author of LIGA’s most recent exhibition, In Your Mind/En Tu Mente. “Since its beginning it has been the place in Latin America that guided our obsessions, a mirror where we hoped to

be reflected,” Martirena said. Infraestudio’s exhibit adds Cuba to the list of countries that have been represented at LIGA and poignantly addresses the idealism required to practice in a state where private architecture is forbidden by law. To do so, Martirena and González showed nine sculptures conveying incipient architectural projects, formally and materially unspecified but sufficiently implied for the viewer to infer the resourcefulness at the heart of the studio’s existence. “Circumstances force us to discreetly explore the edges of a discipline that at times seems rigid,” Martirena remarked.

As the profile of LIGA has grown, its focused mission has perhaps lost some of its novelty. Yet even as a natural disaster and the COVID-19 pandemic affected the organization, it remains steadfast in its commitment to promote young firms, and its modest, precise format (and tight $2,000 budget per exhibition) hasn’t changed. After its first location sustained structural damage during the earthquake that struck the city in September 2017, LIGA, along with PRODUCTORA, moved to a new home at La Laguna, an old lace factory that has been reimagined as a contained production campus. LIGA’s anniversary dinner, delayed a year by the pandemic, took place at La Laguna, whose other tenants include a furniture brand, a coffee roastery, and other creative ventures.

LIGA’s current exhibition space, a 280-square-foot shoebox, is less exposed to the street than its first venue, and, at first glance, it can feel as if something was lost in the move. Indeed the sui generis space on Insurgentes Avenue—perhaps stemming from its small size and relation to the busy urban life outside—was a vital aspect of LIGA’s appeal. And yet from its beginning, LIGA has operated as something bigger than its limited physical footprint. In a way, the space where LIGA’s exhibits take place is incidental to its larger purpose, which is to initiate dialogues that can’t be contained in one room and in fact extend across time zones and borders.

In its first decade, LIGA put Mexico on the map as a participant in a global discourse about how to exhibit architecture, all while raising awareness of the urgent issues concerning architects in Latin America. This regional emphasis sets LIGA apart and unifies a broad area’s current production. Nonetheless, the organization’s more tangible impact has been local: Prior to LIGA, Mexico didn’t have a space dedicated to the exhibition of contemporary architecture. (The underfunded, state-run National Museum of Architecture at the Palacio de Bellas Artes mounts mainly historical surveys.)

Since 2011, Mexico City can call itself home to a small but world-class dedicated space for encounter and reflection around architecture. “The idea that architects can conceive of space critically and reflectively, without the need to design actual space, is incredibly powerful,” Escobedo said. In addition, LIGA has emerged as a nexus for social and professional links, a lifeline for the capital’s vibrant design community. Beyond the metropolis, LIGA has undeniably played an important role in fostering the interconnected architecture scene that exists today across Latin America.

operadora. realizes a house in which its plan mirrors its elevation.

Throughout his career spanning the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Mexican painter José María Velasco developed an iconic vision of the Mexican landscape. His work won him multiple national accolades and international recognition, and through it he ultimately created a symbol of national identity out of the geography of Mexico. The painting El Valle de Mexico is considered one of his most important works. In all seven versions of this painting, the elements of the composition remain consistent: the sky, mountains on the horizon, the valley, rocks, vegetation, and vernacular architecture.

The anonymous structures that inhabit Velasco’s rendition of the Valley of Mexico are the departure point for the project of a small house on a ranch in Singuilucan, Hidalgo.

The house takes the development of its facade as a medium to replicate the informal aggregation of volumes and horizontality characteristic of the architectural features in Velasco’s paintings. This irregular silhouette organizes the program linearly in a plan that mirrors the outline of the facade. In an attempt to further emphasize the flatness of the building, the wall extends beyond the limits of the rooms containing the program, creating a linear datum. The limited programmatic requirements of the house are stretched out in a 100-footlong irregular enfilade, incorporating a storage room at one end of the house and two outdoor spaces adjacent to each of the bedrooms.

operadora. is a creative practice based in Mexico City and Syracuse, New York. Established in 2014, operadora. is led by Edgar Rodriguez, Alexis Ávila, and José Juan Garay.

the topic of “Magical Urbanism: Latinos Reinvent the U.S. Big City.” I attended the lecture and afterward I tried to greet him, but the line was so long that I gave up. The next day, as I was standing in front of my house on Washington Avenue in the Irish Channel, I noticed someone jogging by in jogging shorts. It looked like Mike, but clearly, I thought, Marxists don’t wear such scanty jogging shorts—or do they? “Hey, Mike!” I yelled, and he turned around. Two hours later we were still standing in the middle of Washington Avenue talking about the history of the city, the neighborhood, and its people.

Reading City of Quartz: Excavating the Future in Los Angeles (1990) changed everything. In it two radically different worlds were brought together, each of which I had known only separately. When the book was published, I was living in Alphabet City on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, where a considerable number of my neighbors were squatters and anarchists. Marxist literature was common among the books we read and discussed. In a separate world I had been schooled in architecture and design, which had nothing to do with Marxism—or so we thought. In City of Quartz, these two worlds collided. It was exhilarating to read.

While critics in architecture were exploring deconstructivism and its exalted “shattering of form,” Mike was discussing the “deconstructed Pop architecture” of “Frank Gehry as Dirty Harry.” Few critics had studied contemporary architecture in its urban context and discussed it as “barricades of exclusion” as Mike did. If contemporary urban theory had been “strangely silent about the militarization of city life” and the “destruction of public space,” following City of Quartz we witnessed the rise of a new critique in architecture, most patently in Variations on a Theme Park: The New American City and the End of Public Space (1992) along with a list of other books that followed.

When considering graduate studies, I visited architecture schools across the country and my last stop was the Southern California Institute of Architecture

(SCI-Arc). I was convinced by the program, and Mike Davis taught there. While I was enrolled in his class, which explored Los Angeles and its native ecosystems, he put forth a fascinating analysis of the city that engaged subjects ranging from the dispossessed, luxury urban developments, native cultures, and geology to wildlife. Driving home from school late one night on Interstate 10, I was mesmerized by the surreal scene of massive glowing flames dancing in the distance beyond the Santa Monica Mountains. A few days later, Mike walked into class and handed out photocopies of a draft manuscript titled “The Case for Letting Malibu Burn,” which left everyone in the class stunned.

In the mid-1990s I taught the “Oakwood Seminar,” which Mike and other SCI-Arc faculty had established, a multidisciplinary program that involved working directly with minority youth ex–gang members, artists, architects, and community activists. The craft of breaking down barriers to connect with ordinary people, their common struggles and transformation, was at the heart of the project. This SCI-Arc and Venice Community Housing Corporation study-training-housing initiative gained national recognition as a model program.

In 1996 I left Los Angeles and moved to Rotterdam and lost contact with Mike. A few years later I moved back to Louisiana, my home state. While living in New Orleans I heard that Mike was scheduled to give a lecture at Tulane University on

On August 29, 2005, Hurricane Katrina made landfall near New Orleans, followed by unprecedented destruction. I got a call from Mike, who asked simply, “What are we going to do?” He flew into Baton Rouge, and we began reporting from New Orleans. We interviewed everyone we encountered in the near-deserted streets, from displaced residents, relief workers, and community activists to the bartenders of one of the last standing bars in the city. Observing Mike, I learned what it means to listen carefully to ordinary people and to connect their stories to larger narratives. One of the first articles released was “25 Questions About the Murder of New Orleans,” published in The Nation, which opened with “New Orleans did not die an accidental death-it was murdered by deliberate design and planned neglect. Here are twenty-five urgent questions.…” Moving seamlessly between analyses of the urban and political conditions, Mike had an astonishing ability to access the specifics of the situation, always informed by an encyclopedic knowledge of any subject he turned his attention to. It is almost impossible to describe what it meant to have such a warm and accomplished comrade, hailed as the “most fascinating interpreter of the American metropolis,” join me amid the mass devastation, and its ensuing trauma, as it unfolded in a city that I called home, 80 percent of which had been submerged. Mike’s thinking was always clear and sharp as we grappled with the extraordinary urban, social, and political disasters while trying to communicate their implications.

We traveled to Acadiana, to my hometown of Ville Platte, to interview local citizens who had taken their boats to New Orleans to rescue people stranded on rooftops. While we were there, Hurricane Rita made landfall on September 24, 2005, and we were trapped for days. Mike became part of the family as we all hunkered down to endure the first night of the howling winds of the ensuing storm. We woke up to no electricity and a house full of people, including cousins, friends, and neighbors, many of whom had nowhere else to go. We had generators while many others did not. As we examined the damage in the area, my mother began cooking a seafood gumbo to comfort everyone. Mike was deeply touched by the experience of the place, which was chronicled in the article “Hurricane Gumbo,” featured in The Nation

In Ecology of Fear: Los Angeles and the Imagination of Disaster (1998), Mike explored the relationship between politics and disasters—real and imagined. While some shortsightedly branded him the “Prophet of Doom,” others understood his

critical project of “excavating the future” in an era of endemic calamity, including Adam Shatz in his insightful profile “The American Earthquake: Mike Davis and the Politics of Disaster” (1997). Amid the chaos and devastation following Katrina, Mike noted that a new kind of disaster was unfolding, one spearheaded by advocates of neoliberalism, resulting in the gutting of public institutions in New Orleans, including public schools and housing. In countless ways, he outlined the thesis of “disaster capitalism” as it unfolded in New Orleans in the aftermath of the storm, which was fully explored later by Naomi Klein in The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism (2007).

Michael Sorkin, Carol McMichael

Reese, and I edited New Orleans Under Reconstruction: The Crisis of Planning, published by Verso in 2014, and Mike graciously agreed to write the foreword, which he titled “Sittin’ on the Porch With a Shotgun.” In it he delivered a devastating blow aimed at the misguided reconstruction practices of the powerful real estate establishment of New Orleans, particularly Pres Kabacoff, whom he described as a “developer-gentrifier and local patron of the New Urbanism.” In little more than six pages, Mike’s “Gentrifying Disaster” manifesto was enough of a menace to incite Kabacoff to threaten Verso with a lawsuit unless it immediately recalled the book, which it did. The online version, the only edition now available, features an altered essay. Always tactical and precise, Mike used words in the way some might use car bombs.

Mike appeared most comfortable as an outsider, acting as a counterforce to received discourse. He remained committed, with astonishing rigor, to a method of analysis that allowed us to see emerging structures of the present, often establishing new connections along a dizzying spectrum of issues related to cities, geography, ecology, and politics while considering their relationship to past and present social movements. He made evident the arbitrariness of disciplinary boundaries, which, not unlike political boundaries, too often divide collective struggles. From Prisoners of the American Dream: Politics and Economy in the History of the U.S. Working Class (1986) to Buda’s Wagon: A Brief History of the Car Bomb (2007), his method remained clear.