Lawyer The Arkansas

PUBLISHER

Arkansas Bar Association

Phone: (501) 375-4606 Fax: (501) 421-0732 www.arkbar.com

EDITOR

Anna K. Hubbard

EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR

Karen K. Hutchins

PROOFREADER

Cathy Underwood

EDITORIAL BOARD

Caroline R. Boch

William Taylor Farr

Anton L. Janik, Jr.

Jim L. Julian

Tory Hodges Lewis

Drake Mann

Tyler D. Mlakar, Chair

Michael A. Thompson

Brett D. Watson

Amie K. Wilcox

David H. Williams

Nicole M. Winters

OFFICERS

President

Kristin L. Pawlik

President-Elect

Jamie Huffman Jones

Immediate Past President

Judge Margaret Dobson

President-Elect Designee

Representative Carol Dalby

Secretary

Glen Hoggard

Treasurer

Brant Perkins

Parliamentarian

Brent J. Eubanks

YLS Chair

Frank LaPorte-Jenner

BAR ASSOCIATION STAFF

Executive Director

Karen K. Hutchins

Director of Operations

Kristen Frye

Finance Administrator/CPA

Staci Clark

Director of Government Affairs

Leah Donovan

Publications Director

Anna K. Hubbard

Executive Administrative Assistant

Michele Glasgow

Office & Data Administrator

Cynthia Barnes

Professional Development Coordinator

Lisa McCormick

Information Technology Specialist

Rachel Henderson

Lawyer The Arkansas

11

Lawyer Legislators serving in the 95th General Assembly 12

Artificial Intelligence 101: the Good, the Bad and the (Un)Ethical, By W. Taylor Farr

18

AI Will Change How Law is Practiced By Professor Jordan Wallace-Wolf

22

FinCEN Warns Financial Institutions of Fraud Schemes Arising from Deepfake Media Using Generative Artificial Intelligence By Anton L. Janik, Jr.

24

Much Ado About Algorithms: A Practical Guide to Vetting AI Vendors for Your Law Practice By Meredith Lowry and MaryScott Timmis

28

Rushing to Regulate: the Shifting Legal Landscape Surrounding Digital Asset Mining in Arkansas By Tylar Mlakar

The Arkansas Lawyer (USPS 546-040) is published quarterly by the Arkansas Bar Association. Periodicals postage paid at Little Rock, Arkansas. POSTMASTER: send address changes to The Arkansas Lawyer, 1401 W. Capitol Ave., Suite 170, Little Rock, Arkansas 72201. Subscription price to nonmembers of the Arkansas Bar Association $35.00 per year. Any opinion expressed herein is that of the author, and not necessarily that of the Arkansas Bar Association or The Arkansas Lawyer. Contributions to The Arkansas Lawyer are welcome and should be sent to Anna Hubbard, Editor, ahubbard@arkbar. com. All inquiries regarding advertising should be sent to Editor, The Arkansas Lawyer, at the above address. Copyright 2025, Arkansas Bar Association. All rights reserved.

Contents Continued on Page 2

Lawyer The Arkansas

Advertise in the next issue of The Arkansas Lawyer magazine

President: Kristin L. Pawlik; President-Elect: Jamie Huffman Jones; Immediate Past President: Judge Margaret Dobson President-Elect Designee: Carol Dalby; Secretary: Glen Hoggard; Treasurer: Brant Perkins Parliamentarian: Brent J. Eubanks; YLS Chair: Frank LaPorte-Jenner

Trustees:

District A1: Elizabeth Esparza, Geoff Hamby, William M. Prettyman, Lindsey C. Vechik

District A2-A3: Matthew Benson, Evelyn E. Brooks, Jason M. Hatfield, Christopher M. Hussein, Michelle Rene’ Jaskolski, Sarah C. Jewell, George Rozzell, Russell B. Winburn

District A4: Kelsey K. Bardwell, Craig L. Cook, Brinkley B. Cook-Campbell, Dusti Standridge

District B: Randall L. Bynum, Mark Kelly Cameron, Thomas M. Carpenter, Tim J. Cullen, Bob Edwards, John A. Ellis, Bobby Forrest, Michael K. Goswami, Steven P. Harrelson, Michael M. Harrison, Jim Jackson, Anton L. Janik, Jr., Victoria Leigh, Skye Martin, Kathleen M. McDonald, J. Cliff McKinney II, Jeremy M. McNabb, Molly M. McNulty, Meredith S. Moore, John Ogles, Casey Rockwell, Lauren Spencer, Aaron L. Squyres, Caitlin Campbell Stepina, Jessica Virden Mallett, Danyelle J. Walker, Patrick D. Wilson, George R. Wise

District C5: William A. Arnold, Joe A. Denton, John T. Henderson, Brett D. Watson

District C6: Bryce Cook, Paul N. Ford, Jeffrey W. Puryear, Paul D. Waddell

District C7: Kandice A. Bell, Robert G. Bridewell, Sterling T. Chaney, Taylor A. King

Delegate District C8: Amy Freedman, Connie L. Grace, John S. Stobaugh, Josh Thane

Ex-officio Members: Judge David McCormick, Judge Chaney W. Taylor, Vicki S. Vasser, Dean Cynthia Nance, Dean Colin Crawford, Denise Reid Hoggard, Eddie H. Walker, Jr., Christopher M. Hussein, Karen K. Hutchins

ArkBar at ABA

Kristin Pawlik, Denise Hoggard and Jamie Jones;

Jamie Jones, Glen Hoggard and Kristin Pawlik;

Pawlik (fourth from left) at the Southern Conference of Bar Presidents at the National Conference of Bar Presidents meeting

ArkBar President Kristin Pawlik, Past President and ArkBar Delegate to the American Bar Association (ABA) Denise Hoggard, President-Elect Jamie Jones and ArkBar Secretary and ABA Delegate Glen Hoggard proudly represented the Arkansas Bar Association at the American Bar Association’s Mid-Year Meeting in Phoenix, Arizona, this February.

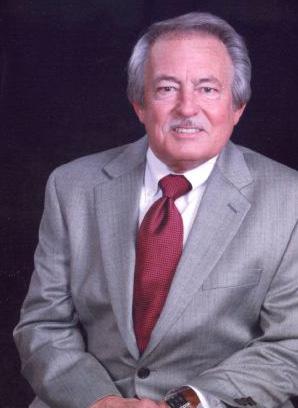

Gift Endows and Names the John Gill Pre-Law Program at Hendrix College

The Hendrix College prelaw program has been named in honor of ArkBar Past President John P. Gill, thanks to a generous gift from his brother and sister-in-law, George and Sallie Gill, of Barrington, Illinois. John Gill has been a pillar of the Arkansas legal community for over 60 years and founded the law firm now named Gill Ragon Owen, P.A. in 1986. John attended Hendrix and is a graduate of Vanderbilt University School of Law.

Board of Trustees Election:

Contested Race in District C7

Candidates for District C7 (One Open Seat)

Members of District C7 will select one candidate from the following two:

• Ledly Jennings

• Clay Sexton

The candidate with the most votes will secure the seat.

Voting Deadline: March 3

Make your voice heard—vote and shape the future of the Board of Trustees!

Oyez! Oyez!

APPOINTMENTS AND ELECTIONS

Jennifer Haltom Doan of Haltom & Doan in Texarkana, Texas, was installed as national president of the American Board of Trial Advocates. Cynthia Nance, Dean of the University of Arkansas School of Law and the Nathan G. Gordon Professor of Law, has been elected to serve a one-year term as president of the College of Labor & Employment Lawyers Board of Governors.

WORD ABOUT TOWN

Rose Law Firm announced that Ty Bordenkircher joined the firm as its newest member. Hall Booth Smith announced that Chris Stevens has joined the Little Rock office as Of Counsel. Kutak Rock announced the following new partners: Nathan R. Finch in Rogers, Caleb S. Sugg in Fayetteville and Timothy J. Harper in Little Rock. The firm also announced new associates: Makyla Jackson in Fayetteville, and Mason Arterbury, Lauren Campbell, Tim Igo and Alex Jones in the Little Rock office. Wright Lindsey Jennings welcomes back attorney Jennifer L. Smith. Hosto & Buchan, PLLC has changed its name effective December 2, 2024, to Hosto & Cardis, PLLC.

Send your oyez to ahubbard@arkbar.com

Historic Statue of U.M. Rose now on Display at the Rose Law Firm

Paul

firm

and historian, providing an overview of the statue’s and its namesake’s historical importance at its arrival ceremony; center: the firm’s newest member Ty Bordenkircher and his wife Mary, and Betsy Baker head of litigation; right: Editorial Advisory Board Chair Tyler Mlakar.

The Arkansas Bar Association thanks Rose Law Firm, Uriah M. Rose’s greatgreat granddaughter and bar member Dana Nixon, and Past President Brian Rosenthal for their efforts in arranging to display the Uriah M. Rose statue. As the first president of the Arkansas Bar Association and a recent inductee into our Legal Hall of Fame, Mr. Rose’s legacy as a legal pioneer continues to inspire. Rose was the head of the three-person delegation to the Second Hague Peace Conference in 1907. Congratulations on this historic homecoming!

This statue was created by the sculpture artist Frederick Ruckstull. It was placed in the United States Capitol’s National Statuary Hall in Washington, D.C. and resided there from 1917-2024. Any member of the bar is welcome to come see the statue; contact Brian Rosenthal at brosenthal@roselawfirm.com for an appointment.

We are Hiring.

If you have a passion for helping the injured and wronged, then we have a lot in common and should set a date to get together. 3-5 years civil litigation experience is appreciated but not required. If you are interested, please let us know by emailing Sarah Jewell at sarah@mcmathlaw.com. All inquiries will be kept confidential.

Transformative Times

As 2025 begins, the transitions happening in our profession are as subtle as the sudden shifting of tectonic plates beneath our feet. Perhaps I tend towards the dramatic, but at times it’s hard to fight the urge to duck as the changes hurtle our way. I have the following news to report:

The Arkansas Bar Association moved to our new offices on West Capitol Avenue in the Victory Building. ArkBar staff have created a welcoming space for members to gather and to conduct bar business within view of the Capitol and the Justice Building. The proximity to the courts and the work of the state legislature is already making it easier for bar leadership and staff to effectively work for you.

The General Assembly is back in session, so, each week, your Legislation Committee reviews each and every bill which is filed to determine whether the proposed legislation impacts the administration of justice or the practice of law. The committee selects bills to send to the sections for review and comment. I encourage members to check ACE each Friday to read bills of interest, share with your colleagues, and send your comments back to Leah Donovan and the committee. Input and interest from the membership are necessary to guide the committee’s work on your behalf.

Members of ArkBar’s Artificial Intelligence Task Force—which is charged with examining the use of AI in the legal field and developing recommendations and resources to educate our members on its use—are delivering on ArkBar’s commitment to prepare lawyers for the lightning-fast changes this technology is bringing to our profession. Both the shifting legal landscape of digital asset mining and the potential impact of AI on the practice of law are examined in this issue of The Arkansas Lawyer. Professor Jordan WallaceWolf observes in his article, AI Will Change

Kristin Pawlik is the President of the Arkansas Bar Association. She is a partner at Miller, Butler, Schneider, Pawlik & Rozzell, PLLC in Northwest Arkansas.

How Law is Practiced, that for most of us, practicing law is “a transformative way to do justice.” As AI transforms the way we practice law, lawyers must understand how to responsibly introduce the technology into our practices. I am so grateful to our colleagues on the task force who have taken away from their practices, courtrooms and classrooms to assist our members in understanding, adapting to, and benefitting from these developments. Stay tuned for recommendations from this talented group of volunteer leaders as they continue to evaluate the need for potential changes to the Rules of Professional Conduct to adapt to the use of this novel tool.

Finally, it is certainly no secret that the administration of justice in Arkansas is experiencing the strain of a transition as well. As the challenges in the halls of the Justice Building spill into the public discourse, I encourage our members to speak with the respect due to the institution of the Supreme Court of Arkansas, and to adhere to the Rules of Professional Conduct when speaking of the controversies.

There is no more important time for us to speak with care and deliberation about the vulnerabilities now visible in the administration of our Justice system. It is crucial that we encourage support, respect and confidence in the institutions to anyone who might be willing to listen. As members of the bar of Arkansas and ArkBar, as officers of the Court, we are the system. It is our professional obligation to demand excellence from each other, from our Judges, our Justices and our administrative system. The voters have spoken. Transitions can be uncomfortable, awkward, and difficult. But they inevitably lead to a redesign, a fresh look, and ideally, an elevation to the next level of performance. Your Arkansas Bar Association is committed to delivering the resources and guidance you need to elevate

your practice while fostering collaboration, innovation and professionalism in the profession. ■

Arkansas Rules of Professional Conduct Preamble: A

Lawyer’s Responsibilities

[1] A lawyer, as a member of the legal profession, is a representative of clients, an officer of the legal system and a public citizen having special responsibility for the quality of justice.

[5] . . . A lawyer should demonstrate respect for the legal system and for those who serve it, including judges, other lawyers and public officials. While it is a lawyer’s duty, when necessary, to challenge the rectitude of official action, it is also a lawyer’s duty to uphold legal process. . .

[6] As a public citizen, a lawyer should seek improvement of the law, access to the legal system, the administration of justice and the quality of service rendered by the legal profession. As a member of a learned profession, a lawyer should cultivate knowledge of the law beyond its use for clients, employ that knowledge in reform of the law and work to strengthen legal education. In addition, a lawyer should further the public’s understanding of and confidence in the rule of law and the justice system because legal institutions in a constitutional democracy depend on popular participation and support to maintain their authority. . .

Rule 8.2. Judicial and Legal Officials

(a) A lawyer shall not make a statement that the lawyer knows to be false or with reckless disregard as to its truth or falsity concerning the qualifications or integrity of a judge, adjudicatory officer or public legal officer, or of a candidate for election or appointment to judicial or legal office.

Predications from a Young Lawyer

As the chair of the Young Lawyers Section, I have the fortune of getting to speak with a broad range of lawyers throughout the state. As part of our executive board, I regularly meet with the board of trustees, members who have been a part of the profession and the Association for years. I’m also afforded the opportunity to meet with law students and newly graduated attorneys at our various social programs and through the law school’s student events. In many ways, my job and the job of YLS is to help bring these two groups together to help improve the professional opportunities for new attorneys and to recruit them into the organization. With this in mind, I wanted to share some of my perspectives from spending time in the middle of these two groups, and my thoughts as to where the profession is headed.

Young lawyers today value their time. A lot of the conversations I have with law students today center on what the Arkansas Bar Association is, and how it can help them professionally. There is an abundance of student and professional organizations out there today that are all seeking to recruit from the same incoming group of students and lawyers every year. There are also a lot of first-generation law students and attorneys joining the profession that do not have any history with the Association. Because of this, I spend a lot of my time talking to students explaining who we are, and what we provide for our members. Students today want to focus their precious time on the activities that will give them the greatest return, including their participation in professional organizations. While we all could give our own perspective about the value that this

organization provides, one area of opportunity for us going into the future will be to streamline how we can show this value to new attorneys and students. This would start with us improving our presence, both in person and on social media. YLS does a great job of hosting social events throughout the year, but we must provide other opportunities for people to get to know us if they aren’t able to make it. We’ve started to put more time and resources into our online presence, and I am certain that social media will be a key recruitment tool going into the future. And as we continue to grow our social media presence, please take some time to follow our group and share our content; it will

Frank LaPorteJenner is the Chair of the Young Lawyers Section. Frank is a managing partner of LaPorte-Jenner Law, PLLC.

help us to broaden our reach to new and future members.

This leads me to my next prediction: it is going to take more effort to reach attorneys across the state. We have a lot of advantages in central and northwest Arkansas, thanks in part to the strong legal communities and the law schools. This isn’t the case, however, for the rest of the state. Our organization does not get many opportunities to visit the other corners of Arkansas, but I predict that it will be more important now than ever for us to do so. Going back to my earlier point, the competition for people’s time is only getting stiffer. We will need to make it easier for lawyers across the state to spend time with the organization, including events that take the Bar Association to them.

Connecting with attorneys across the state should be easier than ever, at least in theory, thanks to social media and remote work practices. Social media will allow us to interact with our members across the state, while remote meetings like Zoom will give those same attorneys the opportunity to join in our pro bono events. The tools are out there; we just need to rely on them more. ■

The Arkansas Bar Association works full time to monitor legislation impacting the administration of justice and the legal profession. In addition to providing a full-time lobbyist who represents the Association before the General Assembly, the Association offers legislative resources to members, including a Legislation Committee that proactively reviews every bill filed during a legislative session, as well as a Jurisprudence & Law Reform Committee which reviews and recommends legislation for the Association’s legislative package.

ArkBar's Legislative Resources website is your source for current legislation issues affecting justice and the legal profession. Members can login to https://www.arkbar.com/legislativeresources/home.

Lieutenant

Attorney

Representative

Artificial Intelligence 101: The Good, The Bad, and the (Un)Ethical

By W. Taylor Farr

W. Taylor Farr is an attorney advisor in the Clerk’s Office of the United States Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit. He additionally serves as an adjunct legal research and writing professor at the University of Arkansas School of Law.

“AI won’t replace lawyers . . . . Lawyers who use AI will replace those who don’t . . . .”1

The phrase “artificial intelligence” or “AI” can be extremely exciting or terrifying. “Exciting” because it continually demonstrates its ability to tackle Herculean tasks. “Terrifying” because it exponentially evolves, leaving people feeling overwhelmed, behind, and potentially threatened. Regardless of the emotion artificial intelligence evokes, two things remain true: artificial intelligence is a present reality, and it is rapidly affecting the practice of law.2 Accordingly, lawyers must take time to understand the technology and determine whether it would be beneficial to integrate it into their practices. This is not a mere business consideration; attorneys arguably have an ethical duty to stay abreast of emerging technologies that impact the practice of law.3 This article is intended to bring lawyers up to speed on the developments in artificial intelligence by identifying possible use cases, current shortcomings, and ethical landmines.4 Whether you are an early adopter of technology or a proud Luddite, this article will hopefully make artificial intelligence more approachable for you and provide you with practical guidance for you to take under advisement in your practice.

Artificial Intelligence: What Is It?

Artificial intelligence can refer to a variety of technologies dating back to the 1960s.5 However, this article explores the more-recent development of “generative artificial intelligence” or “Gen AI.” In simple terms, GenAI creates new content—whether writings, images, audio, or video—by extrapolating from data used to train the program.6 News headlines are littered with stories about ChatGPT, DALL-E, and Codex, examples of GenAI developed by the company OpenAI.7 GenAI also powers the chat bots that have been recently integrated into social media apps, such as Meta AI (Facebook and Instagram) and Grok (X, formerly known as Twitter).8 Different companies have developed GenAI programs and assistants specific to their own products, such as Copilot (Microsoft), Gemini (Google), Apple Intelligence (Apple), and, as particularly relevant to the bar, Co-Counsel (Thomson Reuters/Westlaw) and Lexis+ AI (LexisNexis). Importantly, Arkansas Bar Association members have access to vLex Fastcase, which includes a GenAI assistant, “Vincent AI.”9 But how do these programs actually work? In the chat-box, research, and writing context (which this article focuses on), the simplest answer is “large language models,” which are computer models trained to predict the next word in a given writing. Based on billions of data points accessed from the Internet and elsewhere, these models, like humans, have built relationships between words and use those relationships to generate responses by associating the information inputted by the user with words and concepts from the training data.10 For the average individual (and lawyer), that is as much knowledge as one needs regarding the technology. Indeed, “no one on Earth fully understands the workings of [large language models]” at their most complex level.11

The Good: Use Cases for AI in Legal Practice

As one can imagine, there are plenty of ways that this powerful technology can be leveraged to enhance the efficiency of legal practices. The following are just a few:

Legal Research. Legal research is an area where most professionals should feel comfortable adopting GenAI on some level. For one, companies like Westlaw and LexisNexis have been using artificial intelligence and machine learning in their platforms for years. The real benefit to GenAI in legal research is that it makes the process more conversational. When querying “What are the elements of an intentional infliction of emotional distress claim in Arkansas?” for example, GenAI will simply provide the elements (and a citation reference) instead of a list of cases for the lawyer to search through. And because the program remembers the queries and answers, lawyers can subsequently build off the program’s responses by asking more specific questions or adding additional information.12

Document Review. Through training, GenAI programs can identify patterns in more than just words; they can also identify patterns in document structure. This enables appropriately trained programs to effectively and efficiently scan through material and identify relevant information based upon language and where it is located

in the document. Accordingly, attorneys can use GenAI programs to reduce time conducting diligence13 (in the corporate law context) and discovery14 (in the litigation context). For example, a professional could ask the program to identify contracts that include a change-of-control provision; it would then scan the documents provided, identify language associated with such provisions, and return those documents to the reviewer.

Summarization. GenAI programs are relatively proficient in summarizing provided information. Of course, attorneys can use GenAI to brief caselaw. However, GenAI programs can also handle more gargantuan documents, such as deposition or court transcripts. These programs can provide summaries of these hundred-page documents in varying lengths depending on one’s needs. This talent is not limited to documents summarizations: GenAI programs have also been developed to summarize recordings and web pages.

Brief or Memo Drafting. One of the most exciting (and terrifying) use cases for GenAI is its ability to draft briefs or memos on nuanced legal matters. Capitalizing on their review of thousands of legal documents, GenAI programs can (in theory) digest facts of a provided case, apply those facts to relevant case law, and generate a court brief or client memo similar to those it has been trained on. An attorney can even tailor the generated products to

"GenAI programs still require a practitioner’s knowledge, experience, and humanity to serve the ends of justice. Better equipped with a knowledge of the technology, its uses, its pitfalls, and the ethical considerations, hopefully Arkansas practitioners can stand at the forefront of this technological shift in the practice of law."

match his or her own writing product by training a program on previously written work product. While these programs may be far away from producing error-free, fileready products—and attorneys are even further away from trusting the programs for producing such products—they can at least produce a rough draft for attorneys to review and polish.15

Correspondence. Like brief and memo drafting, GenAI programs can also assist attorneys with correspondence in a variety of ways. If a lawyer falls behind on his or her emails, the program can provide a summary and flag action items. Professionals can also use GenAI to draft emails to clients, modify the tone of their emails, and review their word choice and the conciseness of their writing. Similar to Meta and X, firms can incorporate GenAI chatbots into their websites and take initial case information from potential clients.16

Administrative Tasks. The foregoing list targets practice-of-law use cases for GenAI. There are many other cases that could aid professionals in streamlining the administrative tasks that lawyers daily face.17 Firms can also incorporate GenAI programs into their billing and accounting, human resources, and document management systems, providing them more time and resources to focus on the nuanced and complex legal problems they are specialized to solve.

Of course, in its current form, GenAI presents problems that developers are attempting to address. Until solutions are found, lawyers who utilize GenAI programs need to be familiar with their shortcomings, as to avoid malpractice and embarrassment. The following is a list of issues of which attorneys should be aware.18

Nonlegally Trained Programs. Not all GenAI programs are created equal, nor are they meant to be. Different programs are designed—or more aptly put, trained—to address different problems, as well as the needs of particular industries. Accordingly, lawyers should be mindful that programs trained with original legal materials, such as court opinions, as opposed to secondary sources, such as commentary on court opinions, will likely produce a higher quality product. For example, when prompted to “In three sentences, summarize State v. Bailey, 2024 Ark. 87[,]” ChatGPT returned the following:

In State v. Bailey, 2024 Ark. 87, the Arkansas Supreme Court addressed the standard for determining a probationer’s residence in relation to warrantless searches. The court reversed a lower court’s suppression of evidence obtained during a search of Bailey’s residence, ruling that the standard should be based on the totality of circumstances rather than a strict probable cause requirement. This decision clarifies the legal standards for probation-related searches in Arkansas, aligning with prior state rulings on reasonable expectations of privacy for probationers.19

Compare the foregoing with Lexis+ AI’s response to the same prompt:

In State v. Bailey, 2024 Ark. 87, the Arkansas Supreme Court held that law enforcement must have a reasonable suspicion to believe that the place to be searched is the probationer's residence

when conducting a search under 16-93-106. Warrantless search by any law enforcement officer of probationer, parolee, or person on post-release supervision.. [sic] The statute mandates that the search be conducted in a reasonable manner, aligning with the Fourth Amendment's requirement for government searches to be reasonable. This decision emphasizes the necessity of reasonable suspicion and the reasonableness of the manner of the search[.] State v. Bailey, 2024 Ark. 87.

Notwithstanding the grammatical errors (which are created from hyperlinks to the source material), Lexis+ AI correctly surmises from the case that officers need only a reasonable suspicion that the place to be searched is the probationer’s residence when conducting a search pursuant to Ark. Code Ann. § 16-93-106. ChatGPT wholly omitted this standard, simply responding that officers must consider the totality of the circumstances (which is true regardless of the standard applied). Lawyers should keep this example in mind before relying too heavily on GenAI explanations of law, especially by programs not reliant on primary legal sources.20

Hallucinations. The potential of hallucinations is a more-newsworthy pitfall of GenAI.21 Hallucinations, or imaginary cases cited by GenAI programs, occur because GenAI programs (at least these earlier iterations) do not associate case citations with specific cases. Instead, they view them as a Bluebook formula. The program “says” to itself, “Legal documents contain the sequence [a name] [v.] [a name], [a number] [Ark.] [another number] [a year] after a statement of law, so I need to add those elements,” but it does not recognize that this relates to an actual case that supports the preceding sentence. The result? GenAI will state a—likely— correct proposition of law but then declare that the proposition is supported by a nonexistent, Bluebook-styled case. Westlaw and LexisNexis have attempted to reduce hallucinations by, again, training their programs on primary sources.22 An attorney

cannot treat make-believe citations like a technical error; putting them before the court could violate an attorney’s ethical duties (as noted below) and open him or her up to sanctions.

Bias. Recall that GenAI programs are trained on pre-existing, human-generated material. So, while GenAI programs systematically return a response based upon formulas and algorithms, the training material, plagued by intentional and unintentional human biases, may result in a skewed, discriminatory, or flawed response.23 Combatting bias requires attorneys to reject GenAI responses as gospel and incorporate careful, thoughtful review of the result.24

The (Un)Ethical: Professional Responsibility and AI

So far, this article has presented more business-like considerations for lawyers to consider when determining whether and how to incorporate GenAI into their practices. But there are also ethical considerations under the Arkansas Rules of Professional Conduct that attorneys must account for when dealing with GenAI.25 The following is a nonexhaustive list of these considerations:

Confidentiality.

Pursuant to Rule 1.6, “[a] lawyer shall not reveal information relating to representation of a client unless the client gives informed consent, the disclosure is impliedly authorized in order to carry out the representation or the disclosure is permitted [by Rule 1.6].”26 Open-source GenAI programs “generally use inputted data, often share the data with third persons, and may lack reasonable security measures.”27 Therefore, lawyers should be wary of providing a client’s confidential information or work product to these programs. Transactional attorneys should also be mindful of their (and their clients’) confidentiality obligations under nondisclosure agreements and whether using GenAI programs to conduct diligence, for example, would run afoul of such agreements. To avoid ethical dilemmas, attorneys should consider: (1) avoiding disclosing confidential information; (2) utilizing a closed-source system trained on inter-firm data; and (3)

obtaining GenAI-specific informed consent from the client.28

Candor. As already noted, GenAI programs may produce false or misleading responses and cite nonexistent case law. Should an attorney move forward with such work product without independently checking the veracity of its contents, he or she may violate multiple Rules. Most obvious is Rule 3.3, which prohibits lawyers from “mak[ing] a false statement of fact or law to a tribunal” and “fail[ing] to correct a false statement of material fact or law previously made to the tribunal by the lawyer.”29 However, depending on the severity of GenAI’s error, lawyers may also be pursuing or defending a proceeding or an issue that has no basis in law or fact, violating Rule 3.1’s mandate to pursue meritorious claims.30

Obligations of candor extend outside the courtroom. Under Rule 4.1, “[a] lawyer is required to be truthful when dealing with others on a client’s behalf,”31 and, under Rule 8.4, lawyers have a general obligation to avoid “conduct involving dishonesty, fraud, deceit or misrepresentation.”32 Thus, attorneys should carefully review GenAIproduced communications with the same care as court filings.

Ethical rules aside, by signing a paper filed with the court, an attorney certifies that “the claims, defenses, and other legal contentions are warranted by existing law” and “the factual contentions have evidentiary support.”33 If the filing contains GenAI errors or legal or factual hallucinations, attorneys may open themselves up to sanctions.34 Moreover, attorneys may now have an obligation to double-check that their expert witnesses are not relying on nonexistent GenAI-created research articles or materials.35

Use of AI. Because lawyers must “reasonably consult with the client about the means by which the client’s objectives are to be accomplished” under Rule 1.4,36 lawyers should disclose the use of GenAI in their practice to clients and inform them of the potential benefits and risks of the technology. And while much has been discussed about Rule 1.5 and the billing practices associated with the current use of GenAI,37 the technology may eventually call into question the reasonableness of “the

time and labor required, the novelty and difficulty of the questions involved, and the skill requisite to perform the legal service properly.”38 Further, the efficiency of GenAI may implicate an attorney’s duty to “make reasonable efforts to expedite litigation consistent with the interests of the client” under Rule 3.2,39 or at least undermine requests for postponement based on time constraints.40

Conclusion

GenAI has enormous benefits for the practice of law, and it will likely become as commonplace as Microsoft Word. However ubiquitous the technology’s presence, attorneys cannot abandon their ethical obligations and the practical considerations in using GenAI programs. GenAI programs still require a practitioner’s knowledge, experience, and humanity to serve the ends of justice. Better equipped with a knowledge of the technology, its uses, its pitfalls, and the ethical considerations, hopefully Arkansas practitioners can stand at the forefront of this technological shift in the practice of law.

Endnotes:

1. Lisa Willis, AI Won’t Replace Attorneys— But Tech-Savvy Lawyers Might, Nat'l Law J. (Mar. 13, 2024) (quoting Francisco “Frank” Ramos Jr. of Clarke Silvergate in Miami, Florida), https://www.law.com/ nationallawjournal/2024/03/13/a-i-wontreplace-attorneys-but-tech-savvy-lawyersmight/?slreturn=20241115103658.

2. Multiple legal sources have reported that lawyers are quickly exploring the technology. See Generative AI for Legal Professionals, Thomson Reuters (May 20, 2024), https://legal.thomsonreuters.com/ blog/generative-ai-for-legal-professionalstop-use-cases/ (“[Forty-one percent] of respondents [in 2024] said their firm was considering whether to use GenAI, compared with 30% in 2023.”); AI for Legal Professionals, Bloomberg Law, https://pro. bloomberglaw.com/insights/technology/ ai-in-legal-practice-explained/#what-isartificial-intelligence (“Forty-two percent of survey respondents said they’ve used generative AI personally to just try it out, but only 14% reported that they’ve used the technology to perform work tasks . . . .”)

(last visited Nov. 11, 2024); What Is AI and How Can Law Firms Use It?, Clio, https:// www.clio.com/resources/ai-for-lawyers/ lawyer-ai/ (“[A]ccording to our latest Legal Trends Report, 79% of legal professionals have adopted AI in some way, and one in four use it widely or universally in their law firms.”) (last visited Nov. 11, 2024).

3. “To maintain the requisite knowledge and skill, a lawyer should keep abreast of changes in the law and its practice, including the benefits and risks associated with relevant technology, engage in continuing study and education, and comply with all continuing legal education requirements to which the lawyer is subject.” Ark. R. Pro. Conduct 1.1 (emphasis added).

4. For our previous article on artificial intelligence, see generally Devin R. Bates & Sainabou M. Sonko, ChatGPT: A Lawyer’s Friend or Ethical Time Bomb? Professional Responsibility in the Age of Generative AI, 58 Ark. Law. 24 (Fall 2023).

5. Greg Pavlik, What Is Generative AI (GenAI)? How Does It Work?, Oracle (Sept. 15, 2023), https://www.oracle.com/ artificial-intelligence/generative-ai/what-isgenerative-ai/#how-does-gai-work.

6. See id.

7. See G. A. Walker, Artificial Intelligence (AI) Law, Rights & Ethics, 57 Intllaw 171, 210–11 (2024).

8. LinkedIn has incorporated a variety of GenAI tools as well; however, it has not marketed them under an umbrella identity such as Meta and X.

9. Members must pay a subscription fee to enjoy the full benefits of Vincent AI.

10. See Timothy B. Lee & Sean Trott, A Jargon-Free Explanation of How AI Large Language Models Work, Ars Technica (July 31, 2023), https://socialmarketing90.com/ openai-products-use-cases/.

11. Id. (providing a more-technical understanding of the technology).

12. This type of research will require lawyers to pick up a different type of legal writing: “[p]rompting, the process of giving a large language model natural language instructions on what text to produce.” See Kirsten Davis, A New Parlor Is Open: Legal Writing Faculty Must Develop Scholarship on Generative AI and Legal Writing, 7 Stetson L. Rev. Forum 1, 9 (2024). Instead of simply knowing the right search terms,

lawyers will have to step into the shoes of a legal writing professor and be able to clearly instruct the model on the problem, its parameters, and the expected output (i.e., what the final product should look like).

13. For example, DealRoom AI claims to reduce contract review time by 80%. AI Analysis, Dealroom, https://dealroom.net/ product/ai#:~:text=Diligence%20reviews%20 can%20be%20overwhelming,to%20 focus%20on%20strategic%20tasks (last visited Nov. 14, 2024).

14. Anecdotally, one firm claimed that by using GenAI in its eDiscovery process, it was able to exclude 200,000 documents, saving the attorneys 8,000 hours of review and the client roughly one million dollars. Karl Sobylak, AI in eDiscovery: A Law Firm’s Guide to Assessing Efficacy, JD Supra (Aug. 28, 2024), https://www.jdsupra.com/ legalnews/ai-in-ediscovery-a-law-firm-sguide-to-1230014/.

15. Professor Kirsten K. Davis of Stetson University College of Law has proposed that the use of GenAI may fundamentally shift an attorney’s role in the drafting process. Instead of drafting, “revising and editing a document might be[come] a more humancentered stage.” Davis, supra note 12, at 8. 16. These chatbots must be thoughtfully limited in their responses. Otherwise, they may inadvertently provide prospective clients with faulty legal advice and subject the firm to ethical reprimand or malpractice liability.

17. See Bates & Sonko, supra note 4, at 25 (noting that attorneys are “using [GenAI] to do background research on outside counsel before hiring them, critique attorney work product, respond to e-mails, and predict outcomes”).

18. For additional pitfalls, see id. 19. ChatGPT, chatgpt.com (enter “In three sentences, summarize State v. Bailey, 2024 Ark. 87.” into the provided prompt field) (citing Justia Law and Court Bulletin) (last visited Nov. 11, 2024). Do not be shocked if you try the foregoing prompt and get a different response. Indeed, Judge Kevin Newsom of the Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals recently noted how he ran the same prompt through three different GenAI models 10 times and received answers that were different not only from each model but also from query to query within the same model. See United States v. Deleon, 116 F.4th 1260, 1272–75 (11th Cir. 2024) (Newsom, J., concurring).

20. That said, even models relying solely on legal sources occasionally miss the mark, failing to pick up nuances in opinions. We asked vLex Fastcase’s Vincent AI to provide the holdings of Sowell v. Evergreen Packing, LLC, 2024 Ark. App. 498, a case concerning review of a Workers’ Compensation Commission opinion. It stated that “[t]he court confirmed the admissibility and relevance of the functional capacity evaluation (FCE) while addressing the appellant’s argument regarding its subjectivity and implications for workers’ compensation claims.” The problem? The court did not say that. In fact, the court did not make any substantive holdings because the appellant’s brief was deficient. These were the findings of the Workers’ Compensation Commission; Vincent AI conflated the underlying opinion with the appellate court’s opinion.

21. See generally, Mata v. Avianca, Inc., 678 F. Supp. 3d 443 (S.D.N.Y. 2023); Sharon D. Nelson, et al., What Could Possibly Go Wrong When a Lawyer Relies on ChatGPT to Write a Brief?, Above the Law (May 30, 2023), https://abovethelaw.com/legal-innovationcenter/2023/05/30/what-could-possibly-gowrong-when-a-lawyer-relies-on-chatgpt-towrite-a-brief/.

22. A recent Stanford University study found that Lexis+ AI hallucinated 17% of the time and Westlaw’s program hallucinated 34% of the time, compared to general chatbots, which hallucinated between 58% and 82%. For clarity, the study defined “hallucinations” as either (1) an incorrect description of the law or a factual error or (2) a citation to a source that does not support the claim. Varun Magesh, et al., AI on Trial: Legal Models Hallucinate in 1 out of 6 (or More) Benchmarking Queries, Stanford University (May 23, 2024), https://hai. stanford.edu/news/ai-trial-legal-modelshallucinate-1-out-6-or-more-benchmarkingqueries.

23. For example, The Correctional Offender Management Profiling for Alternative Sanctions, or COMPAS, routinely “overestimates recidivism among African American defendants compared to Caucasian Americans.” Vera Lúcia Raposo, The Digital “To Kill a Mockingbird”: Artificial Intelligence Biases in Courts, 54 Cal. W. Int'l L.J. 459, 474 (2024).

24. Id. at 482. Indeed, deferring to GenAI responses without any overview would

likely undermine an attorney’s ethical duty to “exercise independent professional judgment.” See Ark. R. Pro. Conduct 2.1.

25. For additional ethical considerations, please see Bates & Sonko, supra note 4, at 25–26.

26. Ark. R. Pro. Conduct 1.6.

27. Nathan M. Crystal & Francesca Giannoni-Crystal, The Duties of Competency and Confidentiality in the Use of Generative Artificial Intelligence, 35 S.C. Law. 12, 15 (March 2024).

28. Id.; see also Bates & Sonko, supra note 4, at 26 (describing best practices with GenAI use).

29. Ark. R. Pro. Conduct 3.3.

30. See generally Ark. R. Pro. Conduct 3.1.

31. See generally Ark. R. Pro. Conduct 4.1.

32. See generally Ark. R. Pro. Conduct 8.4.

33. Ark. R. Civ. P. 11(b)(2)–(3) (emphasis added).

34. See generally Wadsworth v. Walmart Inc., Case No. 2:23-CV-118-KHR (D. Wyo. Feb. 6, 2025) (ordering plaintiffs to show cause why sanctions or discipline was not appropriate after eight out of nine cases cited in their motions in limine were hallucinations).

35. The Attorney General of Minnesota called an expert witness to defend the constitutionality of a law prohibiting certain “deepfake” content, which can be generated through the use of GenAI. See Kohls v. Ellison, Case No. 24-cv-3754 (LMP/ DLM), 2025 WL 66514 (D. Minn. Jan. 10, 2025). The expert witness, a Professor of Communication at Stanford University and Director of the Stanford Social Media Lab, was “a credentialed expert on the dangers of AI and misinformation.” See id., at *1, *3. However, in ironic fashion, the district court noted the expert witness’s affidavit contained citations to GenAI-created academic articles. Id., at *1. The district court suggested that Rule 11 (under the Federal Rules) was likely implicated. Id., at *4.

36. See generally Ark. R. Pro. Conduct 4.1.

37. See, e.g., Bates & Sonko, supra note 4, at 26.

38. Ark. R. Pro. Conduct 1.5.

39. Ark. R. Pro. Conduct 3.2.

40. Moreover, “lawyers for criminal defendants must consider whether and in what contexts using generative AI might result in an ineffective assistance of counsel claim under the Strickland test.” See Davis, supra note 12, at 19. ■

Unraveling the Facts. Delivering the Truth.

What We Offer

Expert Testimony: Unbiased, clear, and professional expert testimony in court to support your legal cases

Forensic Investigations: Comprehensive analysis of accidents, mechanical failures, product defects, and more.

Detailed Reports: Thorough and scientifically backed reports that stand up to legal scrutiny

Consultation Services: Collaborate with attorneys to develop a sound legal strategy with solid engineering expertise.

Why Choose Us?

Years of Experience: Our team of forensic engineers brings years of hands-on experience in the field.

Credibility in Court: Trusted by top law firms for delivering concise, accurate, and compelling testimony that juries and judges can understand

Timely & Professional Service: We work diligently to meet your deadlines while maintaining the highest quality standards

Expert Witness Testimony

Mechanical Equipment Failures

VAR- Accident Reconstruction

Agriculture Accidents and Equipment

HVAC Fires & Product Liability

AI Will Change How Law Is Practiced

By Professor Jordan Wallace-Wolf

Jordan WallaceWolf received his J.D. and Ph.D. from UCLA. He is on the AI committee at Bowen law school and writes primarily about torts, privacy, and the role of law in fostering free thinking and first amendment values.

Artificial intelligence will change how law is practiced.1 That much seems clear enough, but the nature and magnitude of the change is much harder to predict. This is because the effect of artificial intelligence on legal services is likely to be realized through different interlocking mechanisms. For instance, artificial intelligence will plausibly change who practices law, and how, and these changes will create corresponding demands on how the practice of law is taught. On the other hand, artificial intelligence will also have direct consequences for how law is taught, and hence, indirectly and eventually, on who practices law and how. In what follows, I review some of the current thinking about how these changes will play out. It should be regarded as, at most, informed speculation about dynamic and unpredictable territory.

AI and Legal Practice

The direct effects of artificial intelligence on the legal profession are already being felt. Indeed, some commentators have argued that the legal profession is in the middle of a “great disruption” provoked by advances in information processing, of which artificial intelligence is just the latest iteration.2

The underlying basis for these claims is that lawyers “work with text.” And since advances in generative artificial intelligence primarily concern the ability to manipulate and respond to text, they enable machines to more cheaply do the work of attorneys.3 The seemingly inevitable result is some degree of “technological unemployment” as human work is replaced by machine work.

Of course, not all legal tasks can be done by artificial intelligence. But some can be, and they are labor intensive. Hence, using artificial intelligence to do them would be attractively labor-saving.

One example is document review. Since artificial intelligence can be readily trained to recognize words and phrases, some kinds of document review can be done by computers, “freeing up” humans to do more “high-end” work.4 A second, related example is due diligence and contracts analysis. For those who deal with a large volume of contractual language, artificial intelligence presents a means of flagging various terms and clauses, thereby streamlining review.5

Even more strategic, judgment-requiring tasks, like drafting a case analysis memo or a complaint, may become much less labor intensive with the help of artificial intelligence.6 They may also be done better, due to the synergy of combining human and artificial intelligence. AI optimists emphasize this latter, cooperative, aspect of AI usage. They point out that humans can do more, and perhaps do better, if they can use artificial intelligence to aid them.7

These examples demonstrate that the effect of artificial intelligence on legal jobs is likely to be appreciable, especially given that artificial intelligence will improve with time, thus replacing human labor for even more tasks over the long term.8

Still, the amount of attorney labor that can be replaced with technology is hotly debated, partly because most research into technological unemployment is not specific to legal jobs and partly because artificial intelligence is improving so rapidly.

Notwithstanding these complications, recent studies predict that artificial intelligence will be impactful. One recent study finds that 19% of workers in the U.S. workforce may see at least 50% of their tasks impacted by AI, and that “higher income jobs” will potentially face “greater exposure” to generative artificial intelligence capabilities.9 Another recent study, conducted by the IMF, finds that “in advanced economies, about 60 percent of jobs are exposed to AI, due to prevalence of cognitive-task-oriented jobs.”10 Lawyers, the study finds, are in a fairly unique position. On the one hand, they are highly susceptible to having some of their work done by artificial intelligence, but on the other hand, lawyers as a profession are also very well-positioned to benefit from the technology in the form of increased wages and productivity.11 A kind of super-elite profession may emerge, with possible consequences for democracy and justice.

A further reason for uncertainty about the economic effects of artificial intelligence is that even if it displaces some attorney labor, it will also likely create the need for new labor that maintains and enables it.12 For example, artificial intelligence systems will have to be effectively utilized, as well as designed, maintained, and trained. Consequently, whether artificial intelligence cuts down on the number of legal jobs will depend not just on what tasks these systems can take over, but also on what tasks they make newly necessary.13

Crucially though, the human labor that AI makes necessary may bear little resemblance to the work of a “traditional” lawyer.14 Unlike lawyers who use artificial intelligence to augment their research, client consultation, and brief writing, those who utilize, develop, and maintain legal AIs will probably perform a more diverse set of tasks, many of which will be less related to law, and more focused on computer science, data analysis, and other cognate fields. They may be, at least in part, more like data/ computer scientists who know some civil procedure than litigators who know a bit about computing.15

These changes present “downstream” challenges for law schools. If tasks that were previously assigned to new associates can be done more cheaply by artificial intelligence, then how will young lawyers gain experience?16 One hypothesis is that associates will be paid much less, until they can be trusted with more important jobs.17

A second downstream effect concerns access to legal services. Arguably, artificial intelligence will make law cheaper and more intelligible to nonspecialists. This will be a great benefit. It will contribute to the rule of law, in the form of a shared understanding of how law works, as well as shared access to the tools of remediation and response that it provides. Insofar as artificial intelligence makes “law” more accessible, it may achieve the good of recentering the legal profession on its core competency; namely, providing ethical and wise counsel in regard to complicated problems.

"Those who study the evolution of the legal profession are right to remind us that change, whether driven by artificial intelligence or some other factor, is not just a matter of more or less lawyers, but also a question about the evolving nature of useful legal work, as well as the social and institutional frameworks in which it happens."

AI and Educational Practice

AI-driven changes to legal practice will have concomitant effects on law schools. After all, if it becomes routine for lawyers to use AI in their jobs, law school graduates will arguably need to have skills in that area as well. Some worry that law schools are not recognizing this changing dynamic, and that they are creating “twentieth century lawyers and not twenty-first century lawyers.”18

Moreover, if artificial intelligence changes legal practice by making a new mix of skills necessary, then law students will have to be taught those skills. Law schools may need to teach (or presuppose) technical skills like writing and researching with artificial intelligence, coding, and data analysis. However, some advances in artificial intelligence will have direct effects on how education happens, including legal education. The result will be that future law students will be differently prepared than previous generations of lawyers, not just because they will have been trained in how to coax good outputs from AI tools, but also, because they will have been taught with AI tools.

From one perspective, an educational environment that includes AI tools is disconcerting. This is because they can be misused.

One kind of misuse is outright cheating. A recent study found that it is very difficult to predict when a student has generated a piece of writing using artificial intelligence and that artificially-generated assignments receive high grades.19 This problem is

currently the focus of many law schools as they adjust their code of conduct and sharply curtail take home exams and other unsupervised forms of writing. UALR’s Bowen law school, where I work, recently updated its honor code to explicitly name “artificial intelligence tools” as a means of cheating. Clarifications by professors are necessary too, to make it clear what counts as a student’s own work in their classes.20

Even when students are not using AI to violate academic rules, their use presents pedagogical pitfalls. This is because learning, especially learning to communicate clearly and persuasively, requires struggle.21 The need for struggle or “friction” requires that students be motivated to face the discomfort of trying, failing, and trying again, often in interpersonal settings. AI offers relief from this uncomfortable cycle, and hence a temptation toward “frictionless learning.” This is a contradiction in terms. A recent example of the temptation posed by AI comes from Arkansas. A philosophy professor at UALR recently asked her students to “introduce yourself and say what you’re hoping to get out of this class.” To her surprise, many students responded with AI-generated answers.22

On the bright side though, artificial intelligence can also be used to deepen learning.23 One kind of improvement is through customized learning. Students can use artificial intelligence to clarify concepts, create tailored practice problems, and critique their work.24 If the functionality and accuracy of artificial intelligence improves more than it already has, it may enable more flexible forms of legal education, such as asynchronous or remote courses.25 These kinds of courses present serious challenges, not least of which is the risk of cheating with AI, but they also broaden access to legal education.

Other uses of artificial intelligence are geared toward the “teacher side” rather than “student side.” For example, I have recently used AI to enhance my teaching in three ways. First, I fed in the transcript of one of my lectures to a large language model, and told it to use the text from the lecture to simulate me. In testing, the model was able to answer questions about the lecture and direct the user to concepts or ideas that are important. I’m still fine-tuning it,

but ultimately, I hope it will be a kind of “debrief bot,” which can work with students after lecture to help them process what I said more fully.26

I have also used AI as an aid for creating hypotheticals and other materials. I used an AI chatbot to create fictional depositions for my torts and remedies finals (I disclosed this fact to the students), with impressive results. Being able to create natural and expressive dialogues elevates legal problems, and helps students practice ferreting out factual claims from ordinary conversations. These changes to legal training are important in themselves, but they also dovetail with the goals of the NextGen bar, which will almost certainly come to Arkansas in the near term. Essay questions on the NextGen bar are designed to more directly and holistically test legal skills, such as by providing students with case materials that must be interpreted in light of the relevant law.27 Artificial intelligence makes preparing for these questions much more feasible.

Third, I have used AI as a focal point for student critique. I asked an AI to analyze the fact pattern of a simple tort case (Gerber v. Veltri).28 I then worked with the class to identify weaknesses in the AI’s response, as well as to elicit better answers. In this exercise, the students gained greater confidence with tort doctrine, but also a critical attitude toward AI outputs. The former is a part of mastering important legal subject matter (and it’s easier if you can critique a robot and not your peers), and the latter is a part of successfully working with AI, with discernment.

Legal Practice and Legal Education

Those who study the evolution of the legal profession are right to remind us that change, whether driven by artificial intelligence or some other factor, is not just a matter of more or fewer lawyers, but also a question about the evolving nature of useful legal work, as well as the social and institutional frameworks in which it happens. The second, more complicated question, is the better one to consider. However, we should also complicate our thinking about changes to the legal profession in a second way. We should resist the temptation to treat the practice of law and the learning of law as undesirable

but necessary chores that we should shorten as much as possible. To the contrary, learning and practicing law are both transformational activities for the people who engage in them. Law school is how one learns law, of course, but it is also how one confronts justice and injustices, takes on civic responsibility and joins a community. Likewise, practicing law is not just about producing motions and reaching settlement. Rather, for many lawyers, practicing is an enjoyable and transformative opportunity to do justice—to be involved in that enterprise in a fundamental way.

Artificial intelligence can surely live alongside these distinctly “human” aspects of legal practice, but it does not secure them on its own, no matter how many briefs it can help us write.

Endnotes:

1. Michael Legg & Felicity Bell, Artificial Intelligence and the Legal Profession (2020); Richard Susskind, Tomorrow's Lawyers (3rd ed. 2023).

2. John O. McGinnis & Russell G. Pearce, The Great Disruption: How Machine Intelligence will Transform the role of lawyers in the delivery of legal services, 82 Fordham L. Rev. 3041–3066; Susskind, supra note 1, at 1.

3. Jose Antonio Bowen & C. Edward Watson, Teaching with AI (2024).

4. Chris Villani, Better, Faster, Stranger: What Attorneys Think of Our AI Future, Law360 (Nov. 27, 2024); John Armour et. al., Augmented Lawyering, 2022 U. Ill. L. Rev. 71 (2022); Susskind, supra note 1, at 75.

5. Armour et. al., supra note 4 at 89.

6. Villani, supra note 4. See also Stephen McConnell, Some Semi-Intelligent Takes on Artificial Intelligence, Drug & Device Law Blog, Dec. 11 2024, available at https:// www.druganddevicelawblog.com/2024/12/ some-semi-intelligent-takes-on-artificialintelligence.html.

7. Bowen & Watson, supra note 3, at Ch. 4. 8. Unconfuse Me, YouTube (2024), https:// youtu.be/IwU0Eqe9v6A (“This is the stupidest these models will ever be”).

9. Tyna Eloundou, et al., Gpts are gpts: An early look at the labor market impact potential of large language models, Cornell University, arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.10130 (2023).

10. Mauro Cazzaniga, Florence Jaumotte, Longji Li, Giovanni Melina, Augustus J. Panton, Carlo Pizzinelli, Emma J. Rockall, and Marina Mendes Tavares, Gen-AI: Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Work, Staff Discussion Notes 2024, 001, 2 (2024), https://doi. org/10.5089/9798400262548.006.

11. Id.

12. See Armour et. al., supra note 4; Daron Acemoglu, The Simple Macroeconomics of AI, NBER Working Paper (May 2024), available at https://www.nber.org/papers/w32487.

13. Armour et al., supra note 4.

14. Susskind, supra note 1, at 24 (“most lawyers do now accept that technology will affect them. But they expect its main impact will be in automation of what they already do today….What many lawyers miss is the possibility and likelihood of innovation…a mindset shift is needed.”.)

15. Armour et al., supra note 4.

16. Susskind, supra note 1, at 232 (2023); Jeff Neal, The Legal Profession in 2024: AI, Harvard Law Today, Feb. 14, 2024, available at https://hls.harvard.edu/today/ harvard-law-expert-explains-how-ai-maytransform-the-legal-profession-in-2024/.

17. Susskind, supra note 1, at 232. 18. Id. at 225.

19. Peter Scarfe, Kelly Watcham, Alasdair Clarke, and Etienne Roesch, A Real-World Test of Artificial Intelligence Infiltration of a University Examinations System: A “Turing Test” Case Study, 19 PLoS ONE (2024).

See also, Bowen & Watson, supra note 3, at 106–131 (explaining the difficulty in detecting AI writing).

20. Bowen & Watson, supra note 3, at 132.

21. See Roger Traynor, Some Open Questions on the Work of State Appellate Courts, 24 U. Chi. L. Rev. 211 (1957) (“I have not found a better test for the solution of a case than its articulation in writing, which is thinking at its hardest. A judge ... often discovers that his tentative views will not jell in the writing. He wrestled with the devil more than once to set forth a sound opinion that will be sufficient unto more than the day.”).

22. Jaures Yip, Teacher’s Post About Students Using ChatGPT Sparks Debate, Sept. 8 2024, available at https://www.businessinsider. com/students-caught-using-chatgptai-assignment-teachers-debate-2024-9 (paywall).

23. B. Ward, D. Bhati, F. Neha & A.

Guercio, Analyzing the Impact of AI Tools on Student Study Habits and Academic Performance (No. arXiv:2412.02166), Cornell University (2024), available at arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/ arXiv.2412.02166.

24. Stephen McConnell, Some SemiIntelligent Takes on Artificial Intelligence, Drug & Device Law Blog, Dec. 11 2024, available at https://www. druganddevicelawblog.com/2024/12/ some-semi-intelligent-takes-on-artificialintelligence.html (students using artificial intelligence to critique their arguments).

25. Susskind, supra note 1, at 68.

26. Tim Lindgren, How to Create Custom AI Chatbots that Enrich Your Classroom, Harvard Business Publishing, May 15, 2024, available at https://hbsp.harvard.edu/ inspiring-minds/how-to-create-custom-aichatbots-that-enrich-your-classroom.

27. Elizabeth Sherowski, Gen Z Meets NextGen: Using Generation Z Pedagogy to Prepare Students for the NextGen Bar Exam, U. Det. Marcy L. Rev. 333, 342 (2024).

28. 203 F. Supp. 3d 846 (2016). ■

FinCEN Warns Financial Institutions of Fraud Schemes Arising from Deepfake Media Using Generative Artificial Intelligence

By Anton L. Janik, Jr.

This article was originally published in the the Mitchell Williams Law Firm’s Between the Lines blog on November 13, 2024, and is reprinted here with permission.

Today the U.S. Department of Treasury’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) issued an Alert to help financial institutions identify fraud schemes relying in part on the use of deepfake media created through generative artificial intelligence (GenAI). FinCEN specifically notes seeing “an increase in suspicious activity reporting by financial institutions describing the suspected use of deepfake media, particularly the use of fraudulent identity documents to circumvent identity verification and authentication methods.”

The FinCEN Alert states that beginning in 2023 and continuing into this year, FinCEN has noted an uptick in suspicious activity reporting by financial institutions that describe the use of deepfake media in fraud schemes targeting their institutions and customers. The schemes include the altering or creation of fraudulent identity documents to circumvent authentication and verification mechanisms, which has been enabled by the recent rise of GenAI tools. Using those tools, perpetrators can create high-quality deepfakes (highlyrealistic GenAI-generated content), including false identity documents and false video content for secondary visual identification, that is indistinguishable from documents or interactions with actual verifiable humans. “For example, some financial institutions have reported that criminals employed GenAI to alter or generate images used for identification documents, such as driver’s licenses or passport cards and books. Criminals can create these deepfake images by modifying an authentic source image or creating a synthetic image. Criminals have also

combined GenAI images with stolen personal identifiable information (PII) or entirely fake PII to create synthetic identities.”

FinCEN is aware of situations where accounts have been successfully opened using such fraudulent identities and have been used to receive and launder the proceeds of other fraudulent schemes, including “online scams and consumer fraud such as check fraud, credit card fraud, authorized push payment fraud, loan fraud, or unemployment fraud. Criminals have also opened fraudulent accounts using GenAI created identity documents and used them as funnel accounts.”

FinCEN advises re-reviews of account opening documents, including performing a reverse image search of identity photos to see if they match any online galleries of faces created with GenAI. To the extent capable, financial institutions may find examining the image metadata or using software engineered to find deepfakes to be assistive. FinCEN cautions financial institutions to watch for identity discrepancies between account documents, and consider evaluating IP address discrepancies from normal customer IP address usage, patterns of coordinated activity among multiple similar accounts, high volume payments to gambling websites or digital asset exchanges, high volumes of chargebacks or rejected payments, patterns of rapid transactions in newly opened accounts, and patterns of withdrawing funds immediately after depositing funds in situations where the ability to reverse a payment is difficult (including through use of international bank transfers or payments

to offshore digital asset exchanges and gambling websites).

FinCEN identifies certain best practices to help financial institutions reduce their risk, including the use of multifactor authentication and phishing-resistant multifactor authentication as well as live verification checks where identity is confirmed using live video or audio. When live video or audio is used, FinCEN advises watching for claimed technical glitches preventing such verification, and the same during such video or audio verification, which may help identify that GenAI is in use.

FinCEN continues to investigate the scope of this issue and requests that financial institutions reference this alert in SAR field 2 (Filing Institution Note to FinCEN) and the narrative by including the key term “FIN-2024DEEPFAKEFRAUD” when reporting suspected deepfake activity. ■

Anton L. Janik, Jr., an attorney at Mitchell Williams in Little Rock, has a specialized practice in complex litigation, tax controversies and information privacy, security and data rights law. He is also certified as an Artificial Intelligence Governance Professional.

63rd natural resources institute

march 5-7, 2025, oaklawn resort, Hot springs

PRESENTING SPONSOR

Title Guaranty of Columbia County

McGowan Working Partners

Hardin, Jesson & Terry, PLC

Daily & Woods, PLLC

Joseph Hickey, P.A.

J. David Reynolds Company

Weiser-Brown

WCW Land Company

Much Ado About Algorithms: A Practical Guide to Vetting AI Vendors for Your Law Practice

By Meredith Lowry and MaryScott Timmis

Meredith Lowry is a partner at Wright, Lindsey & Jennings, LLP and a registered patent attorney practicing intellectual property and data protection.

MaryScott Timmis is an associate attorney at Wright, Lindsey & Jennings, LLP and a registered patent attorney practicing intellectual property and data security.

“Your Honor, my AI assistant objects!” While we haven’t quite reached that level of artificial intelligence (“AI”) in the courtroom or in business, AI tools are rapidly becoming as essential to law practices as coffee makers in the break room. We have grammar assistants suggesting the next word for a brief, algorithms combing through centuries of case law in seconds, and AI scribes dutifully taking notes during client meetings—they’ll even tell you who talked the most during the conference and how participants reacted to the discussion.

Each day comes with the promise from a digital assistant vendor that this new assistant will revolutionize the practice of law. However, before entrusting your firm’s sensitive information to an AI vendor, it’s crucial to consider some risk management tips to ensure you’re not accidentally pleading guilty to poor due diligence.1

The ethical stakes are high. High-profile incidents involving AI legal research have placed these tools under intense judicial and professional scrutiny. But that’s just the start of the concern. When AI systems are used to process sensitive client communications or privileged information, a misstep in vendor selection isn’t just a technical glitch— it could be a violation of the Arkansas Rules of Professional Conduct or a breach of client confidentiality. AI vendors might promise capabilities that sound like science fiction, but attorneys must approach these tools with the same careful scrutiny we’d apply to cross-examining a witness.

The Arkansas Bar Association (“ArkBar”) recognizes the challenges for our Arkansas attorneys in navigating the risks and the potential for AI in the legal practice. In 2023, ArkBar formed the Artificial Intelligence Task Force, which is charged with researching AI and developing recommendations and resources to educate the membership on the use of this technology. Our key elements for study are guardrails for AI in the legal profession, how AI can benefit our members, and ethical considerations for the use of AI in legal proceedings. This author (Meredith Lowry) has the privilege of leading the task force for the 2024–2025 term and working with a dedicated group of attorneys to provide education and guidance to the Bar for potential changes to the Rules of Professional Conduct and risk management concerns for AI use in the practice of law.

This article focuses on those risk management guardrails related to AI, specifically what practitioners need to consider in regard to the accuracy and bias of the AI-generated work product, the data security and confidentiality of client information, and the ownership of the work product returned by the vendor. Recognizing these concerns is essential not only for maintaining ethical compliance, but also for leveraging AI technology to enhance legal practice while minimizing professional risk.

What does AI do?

But before we talk about risks, we need to discuss what an AI tool actually can do. An AI tool is similar to a highly-capable law clerk. AI can process vast amounts of information and perform specific tasks— but like law clerks, AI lacks experience to see bias in a witness or understand the weight of professional ethics.

AI operates through sophisticated pattern recognition rather than genuine understanding. Just as a law clerk might cite relevant cases by identifying legal precedents, AI systems recognize patterns in data to perform tasks. Large Language Models (LLMs) are a specific type of AI that specialize in processing and generating human language—this is why we call them generative AI. LLMs are the AI that can read virtually every legal document, brief, and transcript available in their training

data and provide feedback on this training data—but they don’t comprehend the law in the way human attorneys do. Instead, they use statistical patterns to predict what words should come next in any given context. When an LLM takes notes during your client meeting, it’s not really “understanding” the conversation in the way a human would. Instead, it is using its pattern recognition capabilities to identify important points based on repeated topics and predicting the next word that makes sense in that context.

Accuracy and Bias

Accuracy and bias are typically the first concern for a practitioner considering the use of an AI tool. The legal profession has witnessed cautionary tales of AI-generated legal research, most notably the infamous ChatGPT case where fabricated citations led to significant professional embarrassment.2 These AI-generated falsehoods, known as “hallucinations,” are not mere errors, but often elaboratelyconstructed fictional legal narratives complete with seemingly legitimate case citations.

The root of this problem lies in AI’s predictive nature. Trained on vast datasets of legal materials, these models can remarkably approximate legal language, creating case summaries that appear credible at first glance. However, this training process reveals a more insidious

"Attorneys must neither blindly embrace AI as a panacea nor reflexively reject its potential. Instead, the most effective strategy lies in intelligent, measured integration."

challenge: the potential perpetuation of systemic biases embedded in historical legal decisions. An AI model trained on decades of case law following an older and now overruled decision risks amplifying outdated case law or longstanding discriminatory patterns in areas critical to justice—from criminal sentencing recommendations to civil rights interpretations and employment law analyses.

While we scoff at the use of a mainstream AI model like ChatGPT or Claude for legal research, our traditional tools of LexisNexis and Westlaw have recently started offering AI-assisted research and may pose similar risks. These tools pull from a narrower data set focusing on the law, so there is more precision with the results by a dedicated legal AI tool. But recent research shows that while Lexis+ AI and Westlaw AI-Assisted Research hallucinate less than general-purpose AIs, each hallucinated between 17% and 33% of the time and these hallucinations showed significant flaws, from misunderstanding holdings to outright fabrications.3 These established platforms also still grapple with bias—their AI features may inadvertently favor certain jurisdictions, legal theories, or demographic outcomes based on their training data.

Dedicated AI tools for lawyers represent the most promising current solution for use by attorneys. Attorneys considering

these tools should therefore conduct thorough due diligence of the vendor and the solution. Vendors should be asked to provide not only the accuracy of the AI solution and hallucination rates, but also the vendor’s strategies and processes for minimizing hallucinations and bias risks.

The goal is not to reject AI technology, but to implement it intelligently. By demanding transparency and rigorous validation, attorneys can leverage AI as a powerful research tool while maintaining the highest standards of professional responsibility.

Confidentiality and Data Security

In the legal profession, client confidentiality is not just an ethical obligation—it’s a sacred trust. The integration of AI tools introduces complex new challenges to this fundamental principle. LLMs operate through statistical pattern recognition, drawing from vast training datasets that can potentially include user-provided information. This creates a critical risk: the inadvertent exposure of sensitive client data.4

Let’s jump back to our explanation of how AI works—AI uses statistical patterns to predict what words should come next in any given context and those patterns are based on the training data provided to it. If an AI tool incorporates client communications, case details, or strategic discussions into its learning model, there’s a genuine risk of that confidential information being reproduced in responses to other users. Alarming research has demonstrated that AI models can memorize and potentially reproduce granular details—even sensitive information like social security numbers—if prompted strategically.5 Luckily, many AI vendors with legal tools provide information to prospective users on sources of the training data and whether the tool incorporates user inputs into its training data.