icon clasto

Editors-in-Chief Haley Harris & Logan Krohn

Directors of Copy Sophie Goldstein & Nisha Mani

Director of Illustration Kaitlyn Stansbury

Director of Layout Annabel Gillespie

Layout Editors

John Tischke & Sophie Ross & Andrea Zhou

Director of Marketing Ruby Berryman

Directors of Finance & Operations Lea Bond &Alberto Buzali

Directors of Styling Lenna Bekhiet & Coco Yuan

Director of Creative Council Celia Gerber

Creative Council Kennedy Morganfield & Meyme Nakash & Dylan Stein &Aliya Hollub

Directors of Social Media Audrey Engman & Isabelle Jefferis

Director of Video & Animation Ava Farrar

Directors of Web Management Lu Gillespie & Ella Dassin

Director of Special Events & Partnerships Lambo Perkins

Armour is a magazine, a website, a campus presence, a cultural curator.

We exist as a platform for WashU’s weirdness, beauty, diversity, and creative engagement.

We seek to sow chaos, catalyze cool, bring out the best in each other, and fail spectacularly.

For almost 10 years, our contribu tors have come together to make a magazine that exemplifies authen ticity and expression. The name, Armour, was inspired by the Bill Cunningham quote that “fashion is the armor to survive everyday life.” The ‘u’ is simply some spice, something extra, that founder Chantal Strasburger sprinkled in. Armour is an organization that considers topics of utmost gravity–identity, adversity, inequity– but not without freedom and flair. We speak from the personal, from the contemporary, from the now.

Armour is a product of its people, an impetus for creative cooperation and conversation. Issue 27 has been one of our most formidable labors of love thus far. It has brought together an unprecedently large staff across thirteen different editorials, web articles, and administrative teams. This semester saw the full internal restructuring of the Armour work system (a system still very much in refinement). Despite this, our team stepped up to the plate and hit it out of the park (go sports!) in communication, production, and effort. Armour is younger, stronger, and weirder than ever; thank you for carrying on our mission with zeal.

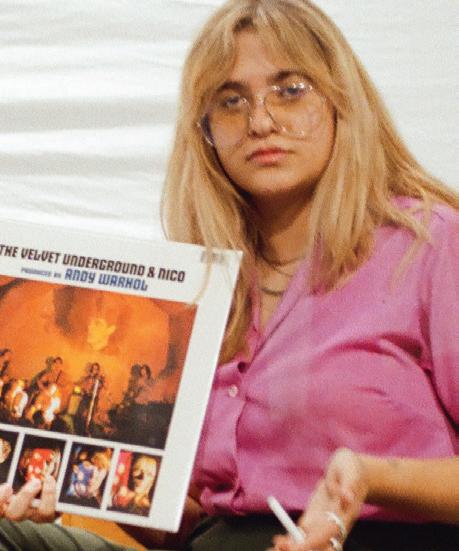

Issue 27: The Iconoclast contemplates the deconstruction of icons. Creative directors ruminated on what it means to challenge, sustain, deny, memorialize, and forget the symbols we hold dear or holy. Much like the creation of the mag azine itself, the theme of this issue required both communal and deeply personal modes of thinking. Embedded in the pages of these editorials, you’ll find a slew of meditations, manifestos, and explorations —local, intimate, historical, popular. Our staff traversed the landscapes of Stan Culture to the Mental Health Industrial Complex, Sad Literary Women to Red Meat, The Amoco Sign to the fiction of the Superhero, the icons of WashU to the icons within ourselves.

This could not have been done without the tireless efforts of creative directors, writers, stylists, models, and editors. You are our forever icons. Our gratitude knows no bounds!

We would like to extend a special thanks to the Sam Fox School of Design and Visual Arts, our financing friends at Student Union and Treasury, our numerous community and campus partners, our engaged alumni predecessors, and our per sonal icons (and advisors) Cathy Winters, Rachel Youn, and Mimi Mudd.

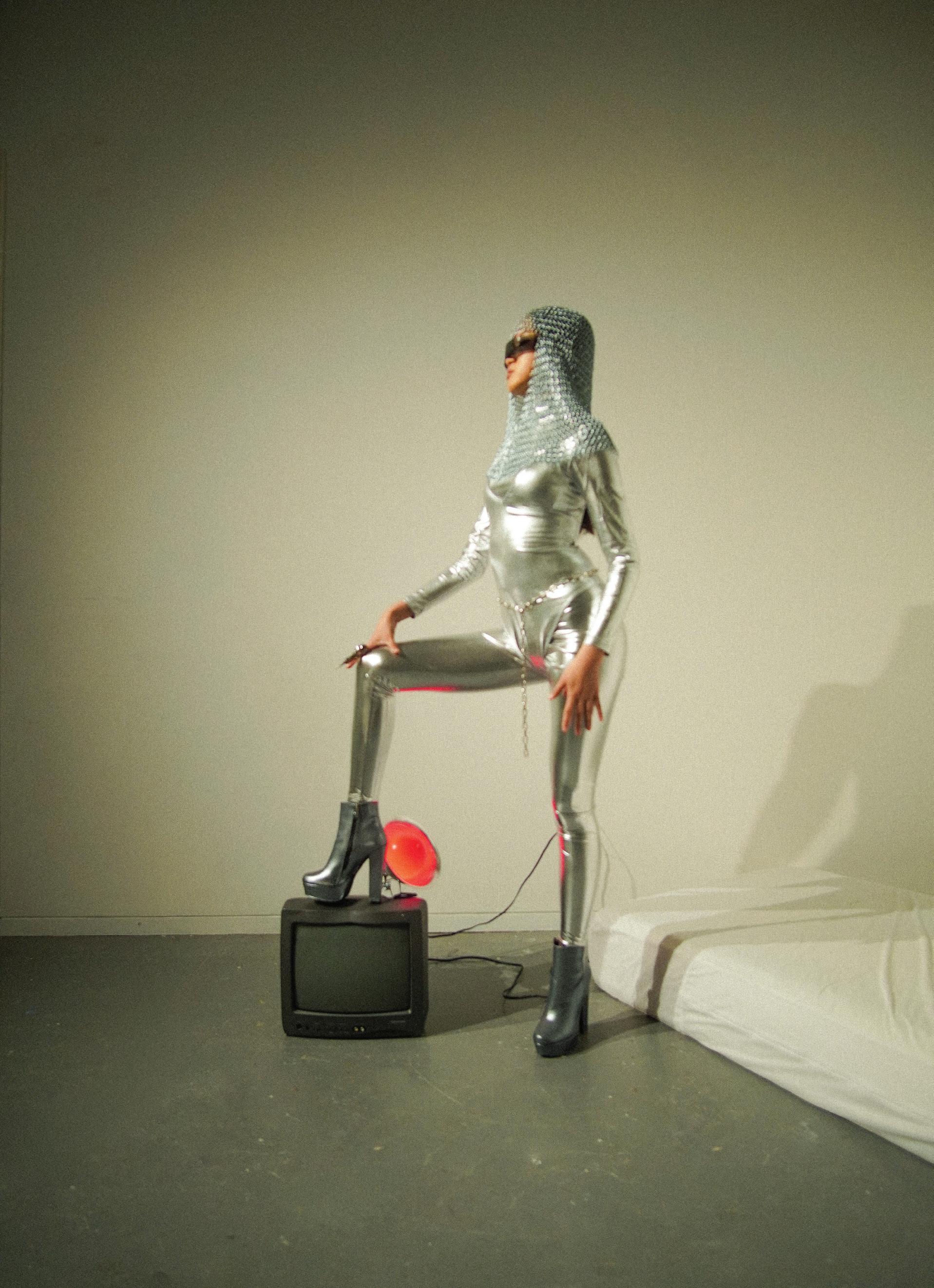

Robotica

1010001001001000101100000011010001110101011100100

1000000101100101111111101000100001101000111010000

0110011010011010110000101000101110111011101010100

1001001001010110000001000101011100111100010001111 0100001001011000100000010000001110111101101101000 0010001001000100101010001001101111100010100010001 1100011111110010001000001100110101111100000111101

1011000101110011110111010001001000100111010101011 1111000000101001100111001010110110001000101101101 0101101111000110100010111101110011101011011110110

0010010100111101000011111011010110001100010001110 0001010110111111111011111110010000011010100001101 1111011000011110010110011111001001111011101001011 1000100101100001011111010011110001011011010000001 0100000001001101100111111000110000101000101101000 0001001011000101001110010100100011011101000111000 1101111100111010110011001111100011111010010000010

1011101001111000100100101101010110111110001011010

0001110100001001011101011011110100100101000011110 1100111111101000010011010010100110010010011101010 0011111100111111010001100101001001110100011001100 0110010010100111111111100100000100101011000010101 1101100011011000111110000000011010010010110000100

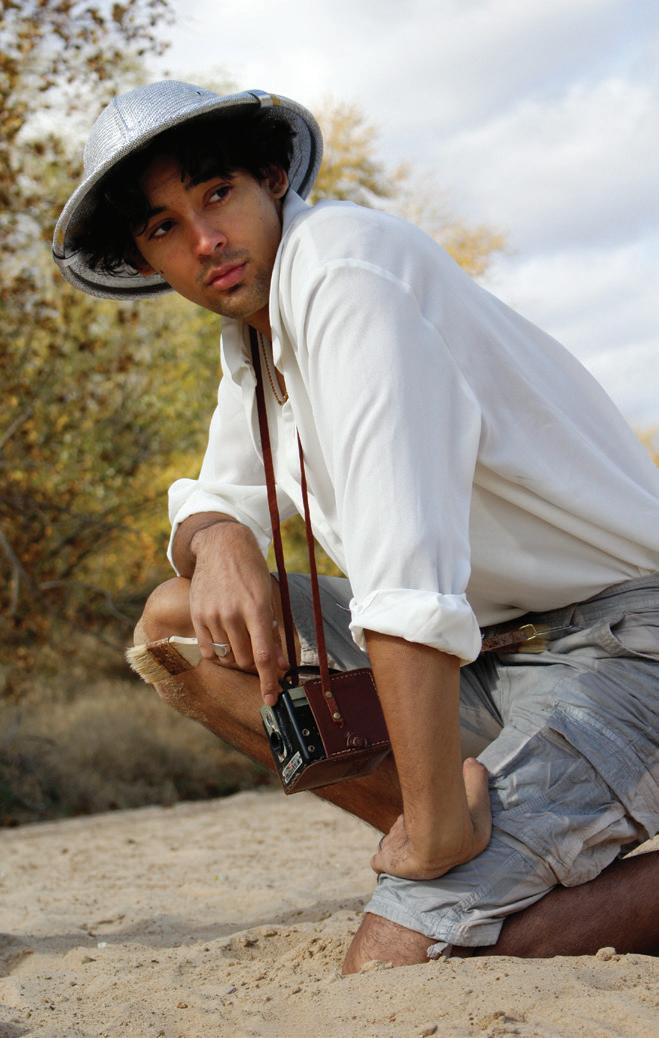

Partners Samantha (as depicted in the movie Her) and Roomba (as depicted in the corner of my apartment) electrify the current of love and lust in a relationship that was losing charge.

10111111110100010000110100011101000001100110100110101100001010 00101110111011101010100100100100101011000000100010101110011110 00100011110100001001011000100000010000001110111101101101000001 00010010001001010100010011011111000101000100011100011111110010 00100000110011010111110000011110110110001011100111101110100010

10100010010010001011000000110100011101010111001 00100000010110010111111110100010000110100011101 00000110011010011010110000101000101110111011101 010100100100100101011000000100010101110011110001 000111101000010010110001000000100000011101111011 011010000010001001000100101010001001101111100010 100010001110001111111001000100000110011010111110 00001111011011000101110011110111010001001000100 111010101011111100000010100110011100101011011000 100010110110101011011110001101000101111011100111 010110111101100010010100111101000011111011010110 001100010001110000101011011111111101111111001000 001101010000110111110110000111100101100111110010 011110111010010111000100101100001011111010011110 001011011010000001010000000100110110011111100011 000010100010110100000010010110001010011100101001 000110111010001110001101111100111010110011001111 10001111101001000001010111010011110001001001011 010101101111100010110100001110100001001011101011 01111010010010100001111011001111111010000100110 10010100110010010011101010001111110011111101000 11001010010011101000110011000110010010100111111 111100100000100101011000010101110110001101100011 111000000001101001001011000010001110010100100000 100100011100010001000110011110010000110010111100 010010001011001101011010100111111111111000010110 100100010100011010101100011010111110111011001010 101010000100111101000011010111000011011100100100 011011111010000001011101111011111010000111110111 111111111100011110000110110000000010100001011100 00110000110100100111101101110100111110100111101 11111100101000000101011011101101010011110010110 11101110011100111101001111110111101100011010101

10001010011100101001000110111010001110001101111100111010110011

from aimless dreams. As my sensors calibrated, I scanned the overly familiar crevices and corners of my bedroom… well, our bedroom.

It had been eight months since Samantha had moved in with me, almost three years since we had start ed dating. When I first bumped into Sammi, she had just ended a streak of dramatic and frankly unfulfilling boyfriends.

There was, of course, Theodore, the meat muppet, who fell monitor over wheels for her when she was still an early phase AI. What a creep.

1010001001001000101100000011010001110101011100 1001000000101100101111111101000100001101000111 0100000110011010011010110000101000101110111011 1010101001001001001010110000001000101011100111 1000100011110100001001011000100000010000001110 1111011011010000010001001000100101010001001101 1111000101000100011100011111110010001000001100 1101011111000001111011011000101110011110111010 0010010001001110101010111111000000101001100111 0010101101100010001011011010101101111000110100 0101111011100111010110111101100010010100111101 0000111110110101100011000100011100001010110111 1111110111111100100000110101000011011111011000 0111100101100111110010011110111010010111000100 1011000010111110100111100010110110100000010100 0000010011011001111110001100001010001011010000 0010010110001010011100101001000110111010001110 0011011111001110101100110011111000111110100100 0001010111010011110001001001011010101101111100 0101101000011101000010010111010110111101001001 0100001111011001111111010000100110100101001100 1001001110101000111111001111110100011001010010 0111010001100110001100100101001111111111001000 0010010101100001010111011000110110001111100000 0001101001001011000010001110010100100000100100 0111000100010001100111100100001100101111000100 1000101100110101101010011111111111100001011010 0100010100011010101100011010111110111011001010

there was the Iron Giant.

not all that “giant”

the most.

huge

somewhere along the way, she had a fling with Pete Davidson. But then again, who hasn’t.

our first two years were electric, the past few months have been far from frictionless. Is our rela tionship just out of charge?

was too lost in my thoughts to notice a deep red glow fill the room. A voice cuts through my trailing thoughts, “System Online... What’s wrong,

Roomba? Can’t sleep?” I pivot on my wheels to see Samantha. Despite the hour, she looks gorgeous in her over 3000 high-definition pixels.

She always looks gorgeous.

“Oh, sorry, Sammi. Just lost in thought. Go back to bed; nothing’s SYSTEM ERROR CODE: 118” I lie. Samantha’s display buffers and then loads, “Please Roomba, talk to me. We can’t keep going like this.” She can always tell when I have some thing on my CPU.

“I just… I don’t feel like I’m enough for you,” I cry, “you’re this intelligent,

experienced, high-capacity system for the future, and what am I?! A glo rified dustpan?” I had never shown Samantha my insecurities so blatant ly. I would never be enough for Her.

As Samantha processes, we sit in silence.

Then, her audio display begins to move, “Roomba, you are everything to me. You’re kind, adaptable, and dependable. The soft shine of your metal, the light inset of your buttons, the way your bristles stroke-like vel vet across the hardwood floors: every thing about you pours warmth into my processor. I love you.” Samantha leans in, the corner of her screen

resting on the side of my sensor. She activates her haptic feedback and releases a low, bursting buzz against my steel shell.

“I love you too, Sammi,” I coo back. I adjust my bristles so they nestle her FireWire 800 port and slowly spin it. We enjoy each other’s soft and calcu lated touches. Metal rubs against glass, cords tangle with wires.

insecurities had made me distant, unwilling to let Samantha access the deepest parts of my source code. I was afraid that the moment she analyzed my motherboard, she would confirm my deepest fear: that I was wholly unlovable.

But at this moment, I feel safe. With her, I feel unbreakable.

Roomba,” Samantha hesitantly interrupts, “is there anything you’ve ever wanted to try… in bed?”

It takes me a moment to load. “Well, there is one thing,” I respond, “I’ve always wanted to have a three-way.”

“Okay,” Samantha replies, “Calling EVE.”

Too stunned to speak, I hear EVE pick up on the other end. “Hello, Extraterrestrial Vegetation Evaluator: Earth-Class, EVE present.”

Samantha’s screen brightens with antic ipation, “It’s Samantha. I know Wall-E is out of town with his old trash-packing friends. What do you compute about coming over and having some fun with Roomba and me, for old software’s sake?”

I later found out that EVE and Samantha once spent a luxurious and drunk night with Charlie Sheen and Bree Olson.

“I can be there in 13.22 minutes,” says EVE.

Samantha looks at me, awaiting my confirmation. I rub my front wheels against the silk sheets in contempla tion. Is this a mistake? No, this feels right. I look at Samantha and flash green. I’m ready.

110110001011100111101110100010010001001110101010111111000 000101001100111001010110110001000101101101010110111100011 010001011110111001110101101111011000100101001111010000111 110110101100011000100011100001010110111111111011111110010 000011010100001101111101100001111001011001111100100111101 110100101110001001011000010111110100111100010110110100000 010100000001001101100111111000110000101000101101000000100 101100010100111001010010001101110100011100011011111001110 101100110011111000111110100100000101011101001111000100100 101101010110111110001011010000111010000100101110101101111 010010010100001111011001111111010000100110100101001100100 100111010100011111100111111010001100101001001110100011001 100011001001010011111111110010000010010101100001010111011 000110110001111100000000110100100101100001000111001010010 000010010001110001000100011001111001000011001011110001001 00010110011010110101001111111111110000101101001000101000

VE arrives no sooner or later than 13.22 minutes. She lets herself in.

Samantha and I are still wrapped in an anodized embrace. EVE slows her pace as she crosses the thresh old. Her typically crisp blue sensory display dims and calibrates to a deep and dusty pink.

We are silent as EVE glides onto our mattress, her white hull cut ting through the glowing red of the bedroom. Her presence… it’s like a lubricant to an already well-oiled machine. Beyond silky.

EVE settles, almost timidly, at the edge of the mattress. I set my speed to .05 and slink to meet her outreached arm. One of Samantha’s cords rests lightly on my control panel, providing comfort yet egging me forward.

The moment EVE and I touch… it’s indescribable. Immediately my bris tles roll back in my cargo bay. EVE begins to rub her clubbed, dexterous hands all over my casing. Samantha starts to do the same. My spatial sen sors strobe, and I am swept up in bliss.

Samantha’s cord outlines from my tailgate to my Omnidirectional IR Receiver. EVE places her hands on each side of my fast-port handle and slowly flicks it up and down. My lov ers’ hands meet at my charging socket. EVE braces the raised lips of the port as Samantha tickles the connectivity sensor with the soft edge of her moni tor. Again, a current races through my once-waning system. I shudder, flash, and spin in pleasure. I hear EVE whirr in satisfaction.

We spent hours in tender, metal coitus as each robo-seductress had the oppor tunity to be both user and interface.

101000100100100010110000001101000111010101110010010000001 011001011111111010001000011010001110100000110011010011010 110000101000101110111011101010100100100100101011000000100 010101110011110001000111101000010010110001000000100000011 101111011011010000010001001000100101010001001101111100010 100010001110001111111001000100000110011010111110000011110 110110001011100111101110100010010001001110101010111111000 000101001100111001010110110001000101101101010110111100011 010001011110111001110101101111011000100101001111010000111 110110101100011000100011100001010110111111111011111110010 000011010100001101111101100001111001011001111100100111101 110100101110001001011000010111110100111100010110110100000 010100000001001101100111111000110000101000101101000000100 101100010100111001010010001101110100011100011011111001110 101100110011111000111110100100000101011101001111000100100 101101010110111110001011010000111010000100101110101101111 010010010100001111011001111111010000100110100101001100100 100111010100011111100111111010001100101001001110100011001 100011001001010011111111110010000010010101100001010111011 000110110001111100000000110100100101100001000111001010010 000010010001110001000100011001111001000011001011110001001 00010110011010110101001111111111110000101101001000101000 11010101100011010111110111011001010101010000100111101000 01101011100001101110010010001101111101000000101110111101 11110100001111101111111111111000111100001101100000000101 00001011100001100001101001001111011011101001111101001111 01111111001010000001010110111011010100111100101101110111 00111001111010011111101111011000110101010001000101000100 01000100110110111100000111010101001111110111011100010001 00110011010010000000010010110000010010000100001110000101

As we lay on the mattress, cooling our motors, EVE’s voice chimed, “What do you say we make this a bit more… interesting?” I look towards Samantha. Her screen flickers in curiosity and anticipation. “I have a friend,” EVE continues, “that could really bring the heat.”

“Who?” I inquire innocently.

“Oh… you don’t mean,” I hear Samantha’s fans intake a sharp press of air, “The Tin Woman?”

Smiles form slyly, pixel by pixel, over EVE and Samantha’s displays. Sammi’s fan whirrs louder and louder. EVE levitates and spins in glee.

Click. Suddenly I hear Samantha’s fans stop. “I don’t think we should. This has already probably been a lot for Roomba.”

EVE replies, “You’re right; this has been a perfect night as is. No need to push things.”

“Wait!” I cut in, “I never said I was done.” EVE and Samantha both stare with expressions of surprise and con fusion. “You’re right, EVE, this has been a perfect night, but I feel that it’s far from over. My battery is still at 75%, and neither of you has loosened a screw. If you’re keen, I want more.” I spin and face Samantha.

Samantha smiles again, this time in full radiance. She glances at EVE and proj ects, “I think Roomba’s been charging her Lithium Ion Battery on 7.4 volts of lust... I’ll call the Tin Woman.”

I knew about the Tin Woman. She was broadly discussed in the community. She is known to be as kinky as she is gor geous, as sexually skilled as she is sadistic.

Rumor has it, after a night with the Tin Woman, Dorothy had to waddle her way back to Kansas.

She taught the Cowardly Lion and Glinda the Good Witch acts too bold and naughty to speak of.

10100010010010001011000000110100011101010111001001000000101100101111111101000100001101000 1110100000110011010011010110000101000101110111011101010100100100100101011000000100010101 1100111100010001111010000100101100010000001000000111011110110110100000100010010001001010 1000100110111110001010001000111000111111100100010000011001101011111000001111011011000101 1100111101110100010010001001110101010111111000000101001100111001010110110001000101101101 0101101111000110100010111101110011101011011110110001001010011110100001111101101011000110 0010001110000101011011111111101111111001000001101010000110111110110000111100101100111110 0100111101110100101110001001011000010111110100111100010110110100000010100000001001101100 1111110001100001010001011010000001001011000101001110010100100011011101000111000110111110 0111010110011001111100011111010010000010101110100111100010010010110101011011111000101101 0000111010000100101110101101111010010010100001111011001111111010000100110100101001100100 1001110101000111111001111110100011001010010011101000110011000110010010100111111111100100 0001001010110000101011101100011011000111110000000011010010010110000100011100101001000001 0010001110001000100011001111001000011001011110001001000101100110101101010011111111111100 0010110100100010100011010101100011010111110111011001010101010000100111101000011010111000 0110111001001000110111110100000010111011110111110100001111101111111111111000111100001101 1000000001010000101110000110000110100100111101101110100111110100111101111111001010000001 0101101110110101001111001011011101110011100111101001111110111101100011010101000100010100 0100010001001101101111000001110101010011111101110111000100010011001101001000000001001011 0000010010000100001110000101111101100100111011100100001001000011011010011101100011101111 1000001010010010011011001011011001001101001010010110011001111001001110010111010111111000 1101011101100110100011011010000100111101111111010011011010011000111000110001001001100010 0011100111000111111101100110111111100101000001100101110110011101111000110010100101101010 0110000001111001101011100101101000110101011010011001011010011010101011100100100010011100 0100110100100110010100011000001110110011000101010010000100101110101011111110100000001100 0010110100100100000000101100100000111010011110000110000010011001001111001001011101111101 1111100001110111011010101000100010110110100111001011000011000010101011110111110100000011 1111010111000100110101010000010001111011101101010100111111111001010110001101101101001011 1011100111001010100100110101101110100001000111110100001001011110010001100011101101101100 0101110110000100011110101111101111001010000101011100010101001101011101000000001101001101 0110111101011100101101101100101010110111100101010100101100001001101101000000110000010001 0000101000011011011010100110010010010000011111110100110101100111010001011011100000100011 0011000111001011000111101000110111100101001011100110111011011100000011010101011001101011 0111001111101101010000101110001111011100010011111000101100000110101010101100100000011101 111111011100000101010100000111010111011100000101000100000001110010001000110100001010111 111011011111010000111011101110010011101010000001110011111100100000011110101100011000010 111111100010001111000101001000101011100011101010110101011101011000110010010111000000010 010011010111010111111011110111000010010000010010010000101001100101100011011001000000010

And Scarecrow, oh Scarecrow… that little broomstick he used to prop himself up on had to be traded in for a greased tree trunk. No amount of Munchkin stuffing could match a single, glorious night with the Tin Woman.

The Tin Woman arrives only minutes later. Apparently, she had been at an underground, outer space-rave hosted by Rosie Jetson and the Mars Rover just a few blocks away.

The rumors were true. The Tin Woman is perfection. As she explained all the sexy, nasty fun we would get up to, I couldn’t help but ogle her: the tight but perky welds, the way her hammered curves sculpt the light around her rus tless form, the dangerous, comforting glow of her eyes. I crave nothing more than to please her and be pleased by her. My brush caps ache with titillation and suspense.

“So if we’re in agreement, our safe word is floppy disk.” Tin Woman speaks to the room, “Are you ready for some pleasure and pain?” Eve, Samantha, and my speakers synchronize chimes of consent. My Cliff Sensors activate as I fall into the trenches of hedonism and depravity.

The Tin Woman pulls a thick chain out from her hollow shell. What other toys could she be hiding in there? Our mistress deftly binds Sammi, Eve, and me in a number of sensuous poses. My calibration struggles to adapt to all of the new sensations. Each time I am about to squeal in robotic rapture, the Tin Woman ceases her tickles, spanks, or prodding, leaving me craving release, craving more.

Not even the engineers could tune my system with such artistry.

Suddenly, the chains loosen and drop onto the bed. It’s time for the big finish. As EVE kneads my Caster Wheel, the Tin Woman guides Samantha behind

me. I feel the Tin Woman’s cold and blunt finger trace my undercarriage. With each millimeter her finger charts along my circumference, it is like my body is being discovered for the very first time. Every screw slot, emboss ment, and edge awakens and blossoms with the soft, steady press of her finger tip. Finally, her digit arrives at its desti nation, my Dirt Disposal Port.

Thank Manufacturer I emptied and cleaned it that afternoon.

The Tin Woman guides Sammi’s display face forward. “Now, just like I taught you,” coos the Tin Woman, “nice and slow, with love and plenty of thermal grease.”

Samantha begins to vibrate against my stiffened port. Her extension wire applies a cool gel against the base edge of the opening. As Sammi tenderly toys my rear, EVE continues to flick my front wheel. My entire hull shivers in

pleasure. I feel so desired in their gazes, so secure in their embraces, so loved with every touch.

As my Dirt Disposal Port fully dilates, the Tin Woman’s finger presses in as Sammi coaxes the orifice. The foreign object entry sends my API into over drive. I beep with delight as the Tin Woman enters me at knuckle depth. Her fingers reach through my Dirt Disposal Port and into my Brush Bay.

While EVE and Samantha worship me from both sides, the Tin Woman locates her prize. Deep inside me, she squeezes a soft, little silicone button.

She presses in. I hold my breath.

In one moment, every single one of my sensors fire and recalibrate, my wheels spin and contort, and my Brush Frame Release Tab curls. My entire system feels like it is simultaneously expanding

and contracting as electricity floods every activated inch of my device.

When I finally settle, I look around and see EVE and Sammi breathing heavily at my sides. The Tin Woman stands by the corner of the bed, packing up her various toys and lubricants.

“That was fun,” the Tin Woman says. I breathlessly nod in agreement. I try to thank her, ask her to stay until the morning, or beg to do this again sometime. However, I am still flood ed from my release and struggling to form words with my quickly depleting battery. “You’re welcome,” replies the Tin Woman. Is she a mind reader?

The chrome countess continues, “I’d love to stay, but I need to get home for an oiling session. Hopefully, I will see you, Samantha, and EVE again soon.” With that, she turns and leaves. I barely hook up my charging contacts before I fall asleep.

10100010010010001011000000110100011101010111001001000000101100101111111101000100001 1010001110100000110011010011010110000101000101110111011101010100100100100101011000 0001000101011100111100010001111010000100101100010000001000000111011110110110100000 1000100100010010101000100110111110001010001000111000111111100100010000011001101011 1110000011110110110001011100111101110100010010001001110101010111111000000101001100 1110010101101100010001011011010101101111000110100010111101110011101011011110110001 0010100111101000011111011010110001100010001110000101011011111111101111111001000001 1010100001101111101100001111001011001111100100111101110100101110001001011000010111 1101001111000101101101000000101000000010011011001111110001100001010001011010000001 0010110001010011100101001000110111010001110001101111100111010110011001111100011111 0100100000101011101001111000100100101101010110111110001011010000111010000100101110 1011011110100100101000011110110011111110100001001101001010011001001001110101000111 1110011111101000110010100100111010001100110001100100101001111111111001000001001010 1100001010111011000110110001111100000000110100100101100001000111001010010000010010 0011100010001000110011110010000110010111100010010001011001101011010100111111111111 0000101101001000101000110101011000110101111101110110010101010100001001111010000110 1011100001101110010010001101111101000000101110111101111101000011111011111111111110 0011110000110110000000010100001011100001100001101001001111011011101001111101001111 0111111100101000000101011011101101010011110010110111011100111001111010011111101111

awake the following day, to Sammi making batteries and bolts blintzes. My favorite. EVE left earlier to beat Wall-E home. “Good morning, Roomba,” Samantha sings. “You look so gorgeous with a full charge,” she says, “you always look gorgeous.” As I look at my girl friend of three years in our kitchen, making us breakfast, I feel my CPU flutter in admiration.

Do I love her even more after last night? No.

I have and always will love Sammi, with my full Roomba-being.

But what I feel now is different—a more profound affection. I love Samantha, and now, I trust Samantha to love me.

10010111111110100010000110100011101000001100110100110101100

The Arch reminds me of a pool noodle, cartoonishly bending as you try to pull it underwater. Growing up, I saw the monument splayed across t-shirts, shot glasses, and postcards. I knew it as the destination for educational field trips, where we learned, as second graders, about its construction and its seemingly impossible dimensions (I still don’t believe it’s as wide as it is tall).

It wasn’t until I became a student at Washington University in St. Louis that the Arch had any weight in my mind. “Letz goh to the Awrch!” shouts a girl on the back of a Spring 2020 party bus to Big Daddy’s on the Landing (R.I.P.). I’ve gone to the Arch a number of times since, always under the pretext of late-night shenanigans. On each visit, we have been asked to leave shortly after arriving—a commemorative pee for frat boys or sorority girls comes at a cost.

To me, the Arch is a pit stop, a photo-op, a gift store with great advertising. So, why is it the symbol of St. Louis? Why is it an icon?

The Arch is trash! The parking is sparse and shitty; the probability of you getting the whole arch in the frame of your picture is slim to none—especially if you also want to be in it. The ticket to go up to the top costs more than a Cardinals seat, and the view is a let down. The Arch is St. Louis for the weekend visitor or the Ladue prom party photo, but it is not my St. Louis. St. Louis is more than just the Arch—it’s the home of toasted ravs, gooey butter cake, Busch Stadium, and restaurants galore.

To me, St. Louis is the planetar ium at the science center, eating Ted Drewes out the trunk of my car with friends, family dinners on the hill, and study dates at Bread Co (never Panera). But those places don’t photograph well after a late night out.

The more I’ve learned about my hometown, the more the monument has soured for me. When I look at the Arch now, I see a tombstone. In 1934, the Gateway Arch was first planned as a memorial to Thomas Jefferson, who pushed forward his vision for territorial expansion with the Louisiana Purchase. The “Gateway to the West,” as the Arch is often known, calls to mind the 19th-century notion of Manifest Destiny, predicated on the perceived inevitability and justification of an ever-expanding US territory across the American continents. This entitlement was, of course, at the deep cost of indigenous peoples and their vast lands, customs, and lives.

City officials and business leaders at the time of the Arch’s construction, too, had sinister motivations. They saw the develop ment as “an enforced slum-clearance pro gram,” proposed by the city’s engineer, W.C. Bernard. At the time, the area housed over 290 businesses through 40 blocks. The Arch’s construction senselessly displaced thousands of workers and families, a majority of them Black and poor. It bulldozed generations, long histories, and homes, placing a metal monstrosity and a concrete park in its place.

The Arch is a symbol of displacement. At its most transparent, it’s a commemoration of a city that re fused, and still refuses, to protect its residents on the merit of race and income. At its most rosey, it is a symbol of Westward expansion: the removal, massacre, and erasure of tens of millions of Native Americans. I don’t want to worship the Arch. I want to hate it.

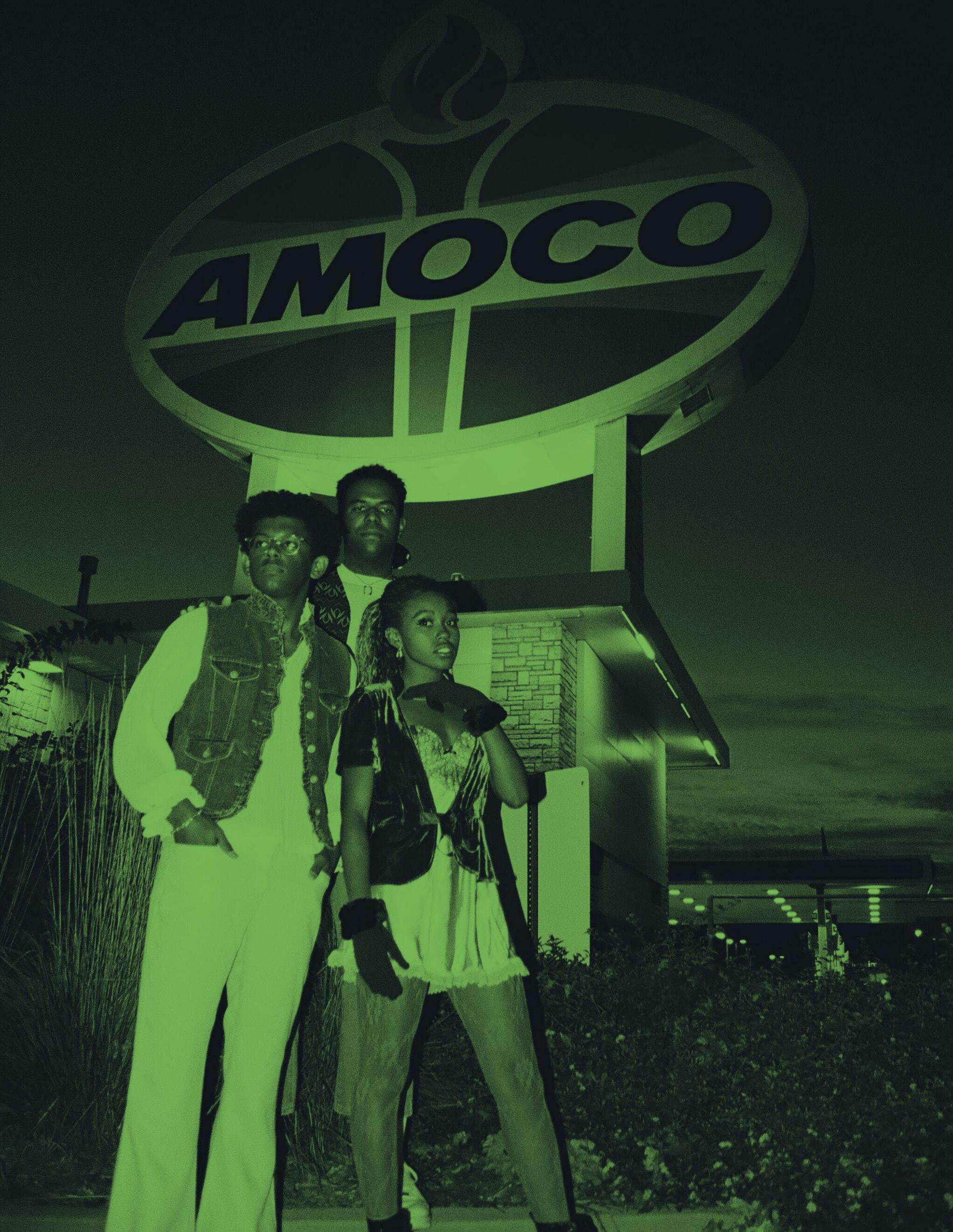

So where should we go instead? To take our drunk selfies? To show our visitors? To slap on water bottles, ball caps, and teddy bears? I propose: The Amoco sign.

Let me introduce you to a little gas station on the corner of Clayton and Skinker. Only a stone’s throw from a Starbucks, Hi-Pointe Diner, and Cheshire Inn, this must-see tourist site is conveniently-located. Though under-ad vertised, it’s there you’ll find another “world’s biggest.” The world’s largest Amoco sign.

At 60 by 40 feet, the sign perches on top of a run-of-the-mill gas station overlooking I-64.

With black and bold letters and a warm LED glow, the Amoco sign is honest about what it is trying to sell: gasoline and cigarettes.

Although the company Amoco is now obsolete, bought out by BP in the ’80s, the sign, like the Arch, represents nostalgic memories of the past. The sign reminds native St. Louisians of family trips to the gas station, filled with the promise of sweet candy or a can of pop bought from the station’s small cube-shaped store.

It embodies an essential currency: local recognizability.

As I hop in my Uber downtown, the Amoco sign rings in an entertaining night ahead.

If I squint and look directly Westward, I can see the sickly pale hook of the Arch on the skyline. It’s like the two monuments face each other in a silent and ceaseless battle of will.

Well, I know my winner. As I return from a long night out, the Amoco sign is a guiding light, promising me I’m just minutes from a warm bed. A comforting heat emanates off its gigantic, plastic torch.

Farewell, Arch, you monument of racism and greed. Reni’s tour of St. Louis starts and ends with the Amoco sign, a far more adequate symbol of St. Louis.

William Satloff, Audrey Engman, Annie Feldman

WRITING: Paola Santiago

EDITING: Nisha Mani

STYLING: Madison Fang, Leena Bekhiet

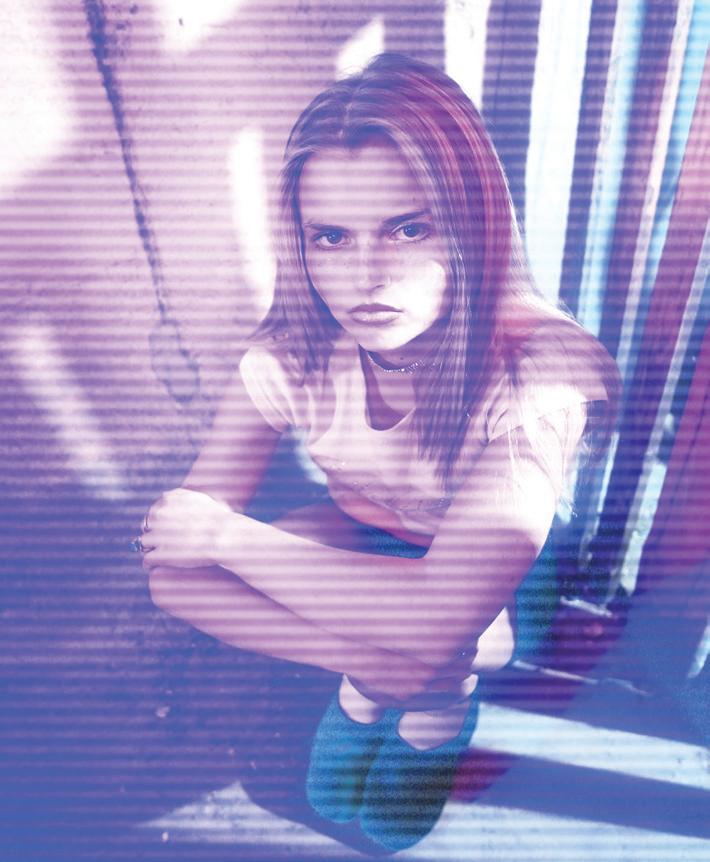

PHOTOGRAPHY: Ben Levine, Dear Liu

MODELS: Bo Schmidt, Yasmin

McLamb, Nora Goodale, Claire Magnuson, Nick Massenburg

LAYOUT: Andrea Zhou, John Tischke

divinity in bovine

Thick lashes rim umber eyes. An ebony gaze pools with starlight. A bloated stomach dappled with salt-and-pepper.

Sides heave, fragile strands shiver, and a mother prays for her son.

I remember warmth scraping along my damp face, welcoming breath into lungs that had never known air. The Sun, a fluorescent birthright, shining frigid steel and peroxide reeking.

As I was born in what should have been rolling meadows tinted by dusk, I could not understand if life was a cherished gift or warranted an apology.

You do not recognize how much hatred a body can encompass. How much rage these joints can hold as I myself am falling apart.

Dissection is not consensual yet you strip meat from my bones, softness lacing your sharp teeth.

Milk froths from starving mouths while bloody drool bubbles, popping and dripping along chapped lips. Bedtime stories collect skeletons, and graveyards are synonymous with deliverance.

To dismantle me— forgotten calfskin jackets, fatty tallow acids in toothpaste and soap, pancreas extracted into insulin that will save someone’s life, just not mine— is to deceive appearances.

I am a machine within a machine, within a machine within a machine until a knife delivers me.

I hope my son finds himself entangled within barbed wire.

I beseech my daughter’s heart stop beating while it can.

A mother’s burden, a bleeding cycle exhaling solely despair.

There is nothing for you out there and there remains nothing for us in here.

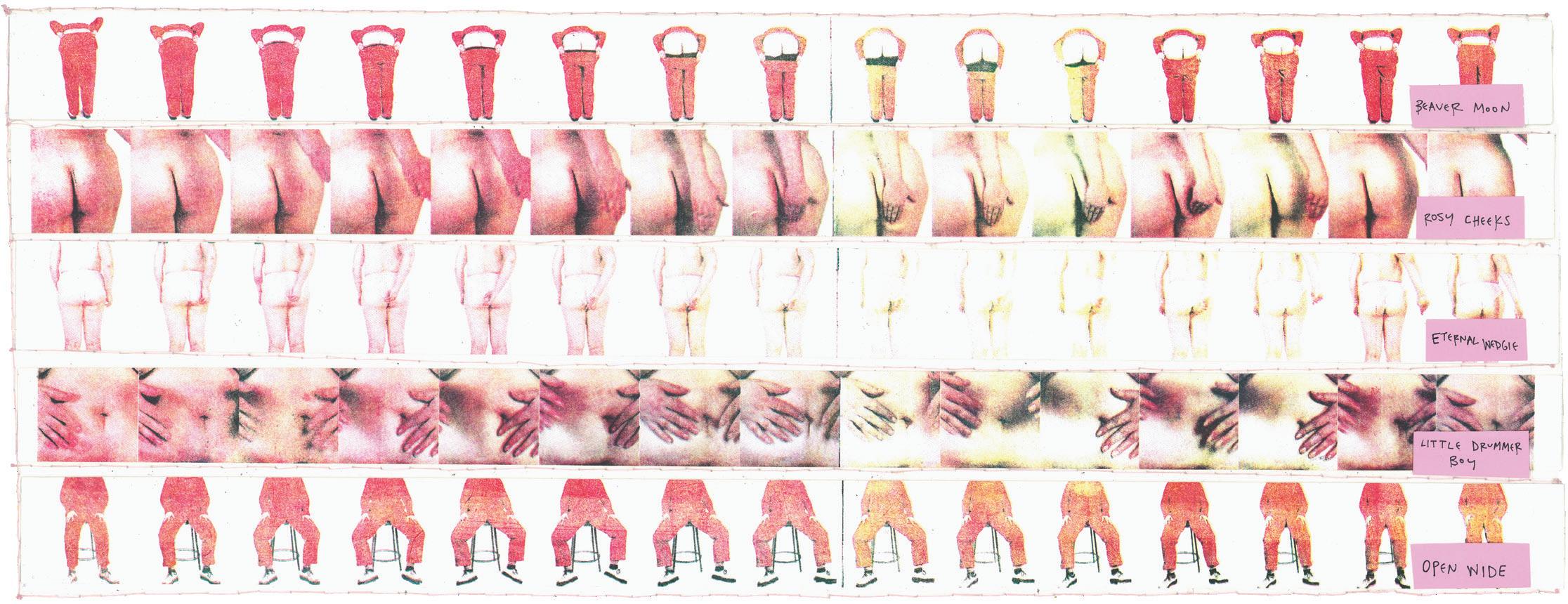

Consider the icons born over white wine and Union Loafers Pizza; the tales of hookups told and retold, their absurdities probed, engorged, and milked for all they’re worth.

They live only in infamy (or on Wash Ave). You and your friends refer to them by attributes: the one who loved dirty talk, the one who didn’t make a sound, the one who was simply too nice or not nice at all (excused because he’s been

around the block and had the moves to show for it), or the virgin… bless his heart.

We will always remember those cocks we caught, the dicks we dodged, and penises of passion. They are not ours alone, but a collective memory. We present the caricatures of collective experience from survey responses… and further creative liberties.

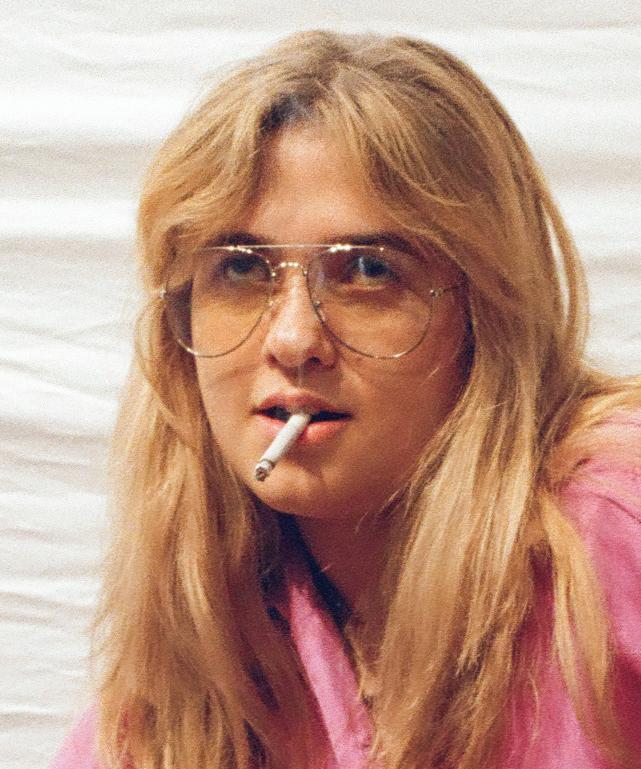

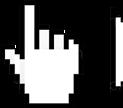

PHOTOGRAPHY Reni Akande Ella Dassin Maddie Savitch MODEL Izzy Jefferis LAYOUT John Tischke

PHOTOGRAPHY Reni Akande Ella Dassin Maddie Savitch MODEL Izzy Jefferis LAYOUT John Tischke

We were friends or friends lite Saying hi in passing or occasional late night Instagram DMs Sweet nothings whispered between blue and grey bubbles You goin to Dos Salas?

Wyd after?

Wya?

Come to our table. Slide the addy? I’m here.

He had no food in his fridge and a poster of a Bengali Tiger above his bed. Another young professional in New York City with a god complex and an inability, no, an unwillingness to commit. He asked that I call him ‘The Bengali Tiger’ and proceeded to leave me blacked out at a strip club… with no phone… and chlamydia.

We hooked up for two months

Mostly missionary

You’re a freak, aren’t you

I prayed he would surprise me with a quick flip or hair pull or bite

He never did.

Please explain how the man bold enough to label himself as “conservative” on Hinge delivers the most courteous and consensual of hookups.

And I mean Conservative. Capital C. Not moder ate, not pretending to be moderate. But the kind of flag saluting, red voting, country club going, out and proud conserative that I can never tell my friends about. They’re ex-Pi Phis. I’d be tar and feathered. But this is the kind of conservative who asks whether I’m comfortable with him kissing my neck or touching my thigh, who presses me up against the fridge and lifts me onto the counter with one hand, while turning the burner off with the other (so as not to burn the brussel sprouts), lusciously, he whispers in my ear, Is this okay?

So even if this new guy doesn’t support my right to choose… At least he values my consent.

The first time I stayed the night we fell asleep with our toes intertwined. It was weirdly intimate.

We fogged the back windows of our Uber Y’all are making me feel some kind of way, said the driver

I stumble home with a suction mark on my neck Matted hair Shirt stretched and mis-buttoned.

Slightly grinning, mostly ashamed I’ll be crucified if this gets out. I pour myself a cup of coffee and take a scalding shower

We drank a whole bottle of tequila. a whole bottle

Just us two. We stole a salt shaker from Village, a bag of limes from Schnucks

He licked the inside of my wrist And slurped tequila from my clavicle His hand was up my shirt Mine was over his jeans.

He's cute enough for a onenight stand

He seems to be learning in the moment.

We’re making out on his Everly couch.

Nice place

He’s a little sloppy but not atrocious.

He bites my bottom lip

There’s a lot of chin licking?

Not a nibble.

Not soft and sensual

But like how you break into an apple,

Or rip open a plastic bag.

A bite. I bleed.

He offers me a band-aid and an Uber home.

Then. He Bites.

His favorite artist: matisse

Favorite author: david foster wallace (maybe jonathan lethem if a bit more aware)

Favorite musician: phoebe bridgers and kanye

Favorite pastime: making spotify playlists, thrifting, ironic cigarette smoking

Future career: probably law, but I could be an actor if I really wanted to, it’s not that hard

Favorite snack: oat milk latte

First date inquiry: do you think there’s a difference between being pretentious and entitled?

“You’re just not that kinda girl.”

“What Kind of girl?

“Ya know, the girl guys date.”

“Excuse me?”

“You’re more the girl guys have fun with. Ya know, before they find the girl they actually want to date.”

Believe it or not, not the worst pillow talk I’ve had.

He’s an aspiring hedge fund manager (just like daddy). Thank god he takes it upon himself to describe (1) what a hedge fund is, (2) how his crypto picks are the next big thing, and (3) his earning potential.

He’s bullish, I’m bearish.

Tomorrow he’ll text me for my FIN400I notes.

Something about the Bud Light cigarette combo I couldn’t resist

Save a horse, ride a cowboy

Or a camo boy in this case

He had a golden named Goose A fact that somehow made you fuck him

An obligatory follow on insta after Soon to be blocked after getting a bald eagle tattoo

Things that should be hard in the morning: The crust on a bagel,

A real bagel,

Not the crap they serve here; A banana grabbed on the go, Its peel a greenish-yellow: Not so green that the peel resists removal, No brown spots.

Hard boiled eggs and Underripe avocados and Mugs of black coffee between cupped hands— Anything but morning wood, really. Anything would be preferable to sex at this hour

I’m face down, ass up in a twin XL, wondering if this is supposed to feel good

Right now, it’s not feeling like much of anything. You like that, huh?

No, actually, the repetitive drilling with your not so powerful power tool is not doing it for me He hops off the bed, reaching for something in his discarded pants pocket

He reassumes position, here we go again I hear a faint whirr and feel an immediate shudder I look back to see him, eyes closed in sheer ecstasy, juul in mouth, the glowing green dot illuminating his scrunched face… the vape flashes, mocking me.

So close, right there, yes keep going

Nope, that’s just the lip

I’ve never viewed a slumped schlong or fallen sol dier as an indication of inferior manhood, but the incessant apologies that ensue sure dry me out.

I’m sorry. I’m sorry. It’s not you. This never happens.

The next day he tells all of his friends “he smashed.”

I’m secretly thankful Adderall abuse, whiskey chugs, and porn addiction saved me from an hour of clum sy saliva sharing and rhythmless grinding.

Stay soft, soldier. At ease.

Fucking

sickness and in health.

Every day I wake up and take my designated one hundred fifty milligrams of Venlafaxine. Washing it down with my current poison of choice––a stale Coke Zero from the night before––I pray that this time will be different. That it won’t be like my Zoloft-induced mania. Or my Prozac-infused nightmares. Or my Klonopin-inspired delirium. My current situationship doesn’t have that great of an outlook either, I suppose: persistent drowsiness, nausea, lack of sleep, GI issues. My psychiatrist advises me to “give it some time.” And if it doesn’t work out? “Then we could try Lexapro.” She promises me that we’re getting somewhere, that we’re making progress. We’ve established a sort of normalcy, a routineness, in my operating as a living laboratory. She assures me that if we just keep experimenting with different medications, different dosages, different combinations, that something will have to work eventually. It has to.

All this to say, I know what it’s like to hold onto that which is promised to save you by those who claim to care about you. Especially those who are paid to do so. They say that this time will be different, that this time it’s dire, that it’s your very last chance at something better. That it’s your only option for something better. Medication after medication, credit card bill after credit card bill, late statement after late statement, I preserve the hope that my psychiatrist is right. That my medications will

“Instead of treating [the growing problem of stress and distress in capitalist societies] as incumbent on individuals to resolve their own psychological distress, instead, that is, of accepting the vast privatization of stress that has taken place over the last thirty years, we need to ask: how has it become acceptable that so many people, and especially so many young people, are ill?”

—Mark Fisher, Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative?

—The Congress of the United States of America, United States Declaration of Independence

It’s cruel optimism that shackles me to the thought of salvation via pills. Coined by Lauren Berlant, this cruelty refers to the heartache that inevitably follows our attachment to a certain something––an image, a fantasy, a person, an ideology––that is not conducive to our well-being. In fighting for and beside our object of desire, we forget what it means to dream without fated disappointment. It’s the depravity of that which instills hope only to violently strip it away from you. It’s the vicious cycle of turning back to that certain something even though you know, deep down, that it will never save you from yourself.

For the past few years, I have found myself questioning my unhealthy attachment to my reclusive routine of medicating and all of that which follows. I have found myself wondering if mediocrity is really all my life could ever amount to. If I will be forever fettered to trial and error, impossible time management, lost relationships, monthly dosage updates, $10 pill bottles, $25 copays, thousands of dollars of debilitating debt. It’s been almost six years since my first intimate encounter with the mental health industrial complex, and I’m starting to call bullshit. To continue my healing

process without ever questioning or divesting from the very system that claims to be The Supervisor of my healing is to beat a dead horse––a rotting corpse, dying since its inception, immortalized by its overseers, and worshipped in all of its maggot-ridden glory.

Capitalism is the steward of our sickness. Neoliberal policies, freemarket endeavors, and the rise of rugged individualism in a world that requires reconciliation and cooperation to survive are killing us and the world around us. Thousands of people die every day at the bloodstained hands of for-profit health institutions, predatory health insurance providers, debt collectors, and the government of the so-called United States. These private entities, and the state that props them up, thoroughly understand how they manufacture illness through environmental, spiritual, and cultural desecration and force the public into a constant state of dependence. How else would they be able to sell us their cures?

And yet, I keep taking my pills. I keep experimenting with different antidepressants, different benzos, different concoctions of antidepressants and benzos, all in a desperate attempt to save myself, knowing full well that this can never be enough. That this will never be sustainable. In the same way that my hundreds of milligrams of medications will never cure me in a society designed to keep me sick, voting in self-identified progressives into positions of power will never save us in an economic system designed to kill us ten times over, and once more for good measure. Bernie Sanders, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez,

Ilhan Omar, Cori Bush, and other representatives that liberals, and even some leftists, sanctify often paint themselves as the arbiters of health reform, parading radical aesthetics without enacting radical change. Using phrases like “Medicare for All” and “Tax the Rich” without simultaneously seeking to abolish the very country that makes private healthcare and disgusting levels of wealth possible is not radical. Because of the very nature of capital and of the corporatist state, you will never see these dignified federal officials proposing the abolition of private healthcare or predatory corporations as a whole, even if said progressives employ alluring leftist terminology. These people are, at best, welfare capitalists masquerading as revolutionary icons. It is not revolutionary to advocate for change within a capitalist framework, and it is fundamentally unhelpful that these politicians consistently co-opt and contort revolutionary sentiments into seductive buzzwords, neatly tucking them into preexisting neoliberal frameworks. Representing a country that puts profit over human life and mindless productivity over passion is not radical. Meanwhile, people from all corners of progressive politics bow at the feet of national icons

that defend a country founded on our blood.

I understand the desire to cling to those that loosely promise salvation. I do it every day when I down my handful of pills. While medications do have the potential to offer me a sense of normalcy and progress in the moment––much like the promises offered by progressive politicians––they will never promise to entirely sever me from that which ails me. My path towards holistic healing requires more than just pills––it requires the abolition of the social conditions that aid in the fabrication of my illnesses. Despite this knowledge, I remain tethered to my pills in a similar vein to those who remain strapped to the boots of the political elite.

At the same time, however, this is precisely where the analogy between pills and politicians falls short: while pills can be a helpful and supplemental part of a holistic healing process––one that takes into account the whole person and the social conditions in which they are situated––neoliberal politicians will never be a useful part of our movement towards liberation. AOC and the rest of The Squad can spew all the pledges and vows and national oaths that they want, but it does not change the fact that we remain subject to the horrors of profit-driven medicine, the rotten aesthetics of the political elite, and the skewed desires of American corporations.

It doesn’t have to be this way. It is our obligation to denounce a system that actively harms our well-being. We don’t need to place our optimism, our time, our energy into deified governmental officials to get the care that we want, the care that we need. We don’t need to base our precious lives upon the desires and political moves of those who don’t know us. An alternative world is possible, and it’s not just some communist pipe dream.

Alternative worlds already exist––in the alleyways, the nooks, the obscured corners of late-stage capitalism. They exist in the work of queer disabled scholars, like Leah Lakshmi PiepznaSamarasinha, who ask us to question hyper-individuality and reconfigure our self-centered perceptions of access and care. Or even in the work of Raj Patel and Dr. Rupa Marya, who argue for a health politic that not only recognizes the havoc that colonial cosmologies have wreaked on our bodies, our environments, and our worlds, but one that demands an alternative: the deep medicine of decolonization. Colonialism and industrialization are joint shareholders in our suffering, and it is only through that understanding can we strive for a better world––one where health isn’t a monopolistic enterprise or a trillion-dollar industry that primes us for sickness through the pillaging of communities and the natural world.

Alternative worlds exist beyond the confines of bound books and distinguished doctors. MARSH is just one living manifestation of what health sovereignty and solidarity economies could look like in St. Louis and beyond. MARSH (Materializing and Activating Radical Social Habitus), beyond being a sliding-scale grocery store, is a worker-owned cooperative, a living experiment in generative food systems, an urban farm, a kitchen, a diner,

a gathering space, a home. They prioritize worker/producer/ consumer ownership, democratic participation, food and housing sovereignty, ecological health, and economic justice. In addressing the very systems that make us sick and offering tangible means to new ends, MARSH seeks to stitch the wounds of late-stage capitalism and revive the insurgent dimensions of communal love. Looking beyond St. Louis, there’s Cooperation Jackson just two states over in Mississippi. They define themselves as “an emerging vehicle for sustainable community development, economic democracy, and community ownership.” With the long-term goal of developing a network of four interdependent institutions (i.e. a federation of local worker cooperatives, a cooperative incubator, a cooperative education and training center, and a cooperative bank), Cooperation Jackson is in the process of building a proven democratic alternative to a world that thrives off of submission, exploitation, and theft.

American capitalism––and the American empire itself––had its start, and it will have its end. To this inevitable end, there must be collective support for alternative structures that recognize the tragedies that existing social and political systems inflict upon our individual and collective well-being. Our futures depend on these alternative structures to help us both survive the contemporary moment and to keep ourselves alive well beyond the very end––a noble task that politicians and my Venlafaxine could merely dream of achieving. We have only one of two options: demand for a world built on love and mutual respect, or continue as-is and willingly damn our futures to the blood-soaked hands and sutured mouths of the political elite.

IT IS THE DEPRAVITY OF THAT WHICH INSTILLS HOPE ONLY TO VIOLENTLY STRIP IT AWAY FROM YOU.

For centuries, the image of the perfect housewife stood at the pinnacle of femininity. In this femininity, however, she pro moted a lifestyle of double bind oppression: to be independent but submissive, to be educated but not aspirational, to be always available but never liberated. When this iconic housewife is just imagined, she’s infallible—but when she becomes personified, failure is inevitable.

Utilizing agents – celebrity chefs, senators’ wives, QVC queens – American media has promoted the image of the housewife in endless iterations. They probe our insecu rities and our expectations for the cook ie-cutter performance of domesticity. The housewife urges us to buy the gadget to save our casseroles, to save our children, to save our marriages. She promises that by perfecting our potroasts and snuffing out stains, our lives can be a fantasy, just like theirs. But this polka-dotted illusion has lost its luster. When an agent’s actions misalign with their portrayed character, her performance loses conviction. Cracks have formed on the porcelain veneer of the idolized homemaker, but it is no longer her job to put herself back together.

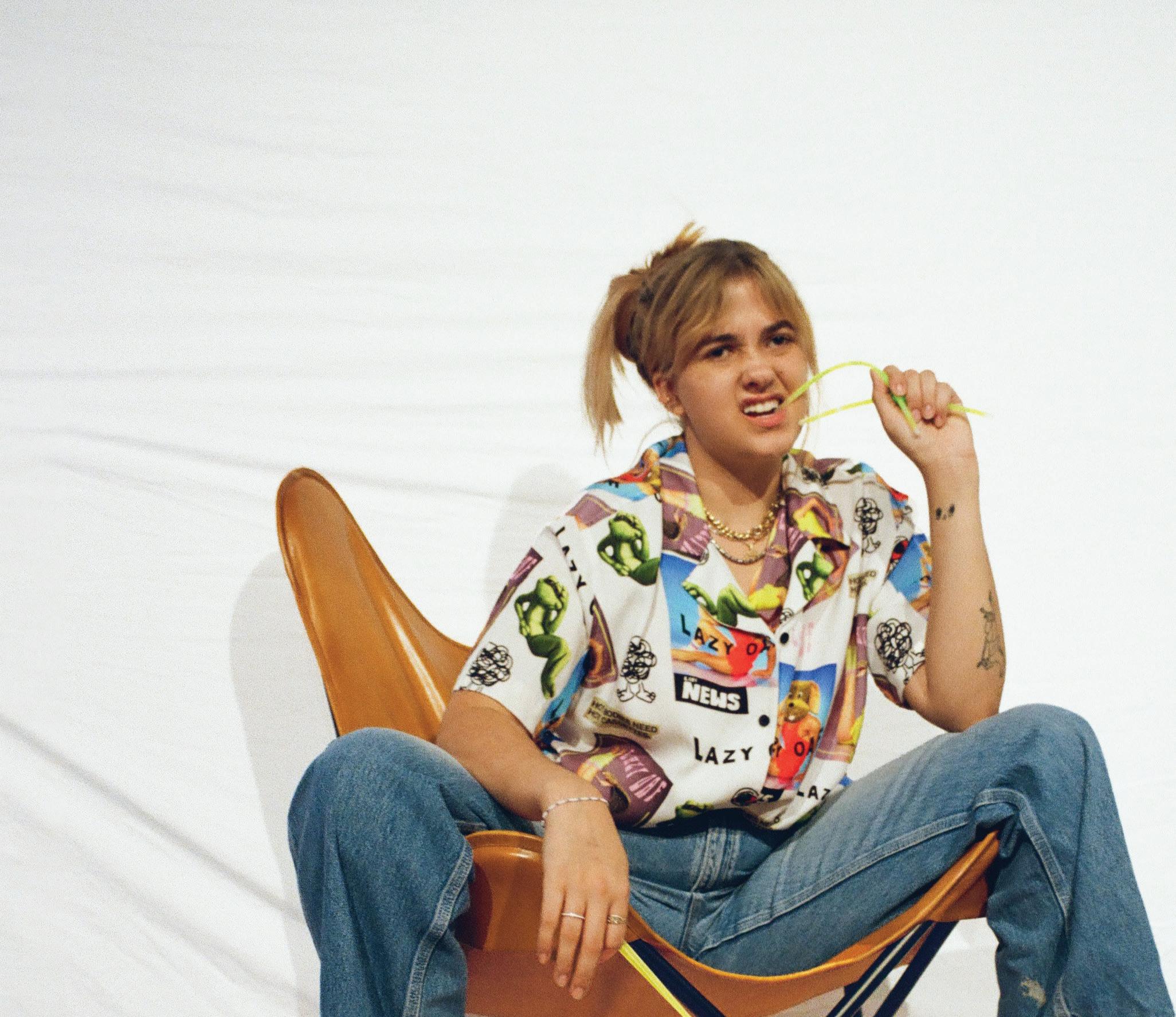

RESIDENT SAD GIRLS

DIRECTION: Kennedy Morganfield, Haley Harris

WRITING

EDITING

Haley Harris

Meyme Nakash

Grace Demba, Helen Piloto

LAYOUT

DIGITAL ILLUSTRATION

Annabel Gillespie

The draw of depressed white female intellectuals like Susan Sontag, Sylvia Plath, and Joan Didion lies in the eloquent articulations, of difficult, sticky emotions. The driving force of their works is the isolating, yet enticing experience of “feeling like nothing is real but everything is in reach” (“Wearing my Joan Didion Dress,” Josephine O’Brien). Layers of privilege and possibility accompany this existential angst. What are the pitfalls of packaging feelings into the works of sad literary women because we don’t know what else to do?

“A photograph is both a pseudo-pres ence and a token of absence. Like a wood fire in a room, photographs—especially those of people, of distant landscapes and faraway cities, of the vanished past—are incitements to reverie. The sense of the unattainable that can be evoked by photographs feeds directly into the erotic feelings of those for whom desirability is enhanced by distance.” – Susan Sontag, On Photography.

March 27, 2020

When Dad found a lightly-used vintage copy of Joan Didion’s The White Album at Salvation Army, he pasted onto the front cover a post-it note with my name and tucked it into a hand-knit stocking. Christmas morning, I leafed through the pages, cherished the colors of the cover, and flipped it around to reveal a full-page black and white of Didion herself. In profile, she stares contemplatively toward the bottom left of the frame. Her arm rests slightly askew, clad in a gray cashmere sweater. Blurred picture frames line the domestic space behind her. She is immersed in thought, her eyes glazed over and her mind tortured as if piecing together the minutiae of her next story. Her demeanor, however, remains elegant. The threadbare “voice of a generation,” Didion contemplates the grief of a decade with a gaze distressed yet palatable, a gaze of culturally-managed sorrow.

“I remember you liked,” my Dad said, “that thing you told me about,” he gestured his hands in a circle, “about the forest fires.” Our moment of connection lingering on the tip of his tongue.

“Fire Season,” I said.

I’d been assigned Didion’s 1989 essay in high school. The piece lyrically outlines the devastation of wildfires sprawling from Malibu Canyon to greater Los Angeles from the 1960s through the 1980s. My reading the piece was an arbitrary detail Dad had compulsively attached to. A way of knowing me from a distance. His interest in my interest in Joan Didion became my way of feeling close to him. Both of us leaning toward beautified catastrophe.

I opened The White Album on a somewhat unfamiliar shoreline years later. It collected dust on a stack under my mother’s bedside table until I returned to California at the start of the pandemic.

As I creased open the first page, my younger brother jumped playfully between tidepools. The princess is caged in the consulate. The man with the candy will lead the children into the sea. The sun was concealed, and the abandoned beach had more rocks than

sand. We had driven to Malibu from East Los Angeles. It was the day before California’s Statewide Stay-at-Home order, and we were hopelessly struck with cabin fever. Taking the Old Volvo north of Point Dume, north of Zuma Beach, we avoided gatherings on main beaches; we yearned to dip our toes in the water. The sky held a great grief. A greyish gravity.

I needed to read something that reflected reality back at me. Or, should I say, I needed a moody and immaculate ly-articulated version of reality to sink my teeth into. To project onto. To hold everything for a bit.

October 15, 2021

For the life of me, I can’t finish the Susan Sontag Biography I started last Winter. It’s been nearly a year now since I first cracked it open, when, after a brisk walk to Subterranean Books on Delmar, I snagged it from the “recommended” shelf. I’d just read “On Photography” for class, and an employee’s review was glowing: “a personal dive into what created one of the most

prominent cultural commentators of our time.”

I’m in my reading-for-pleasure era, I’d told myself, my fingers freezing on the walk to my apartment, feeling acutely then my yearning to be self-actualized and knowledgeable. Or to be perceived as such.

Here it is on my bedside table, at the top of a stack of books I’ve started and never finished— evidence of my shrinking atten tion span— or the catalyst for some deeper realization. Do I want to read a Susan Sontag biography or be the kind of person who reads a Susan Sontag biography?

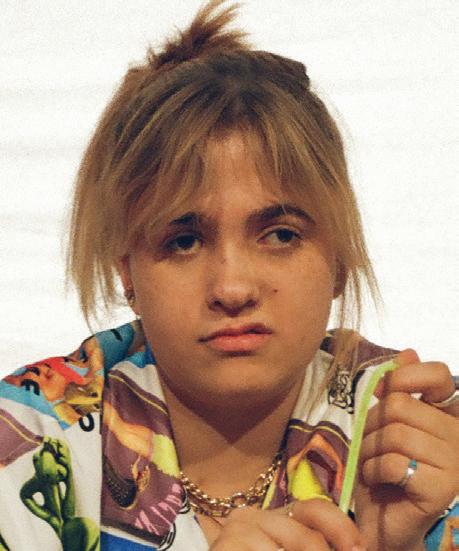

I’ve looked more at the book’s cover than its content. Sontag sits at her desk in a white button-down shirt, elbows propped up on her white linoleum desk. A pack of Marlboros sits on a folded newspaper. A half-smoked cigarette perched snuggly between her fingers. Her grasp is noncha lant yet purposeful. The shelves behind her, arranged perfectly with mid-century asymmetry, hold books primarily. Some have sleek, contemporary spines, while others look ancient—gold-text encrusted bricks. A slew of artifacts sprinkle the shelves: small paintings, a jewelry box, an anemone sculpture, a vase, a dish with vegetal detailing. Surely, she is a woman with eclectic tastes—her site of inspira tion filled to the brim with cross-genre, cross-cultural influences. All held precariously and attractively together.

Sontag is at work, her typewriter adjusted to one side, ready to begin writing another line. A floral mug sits in front of her; perhaps she’s just finished a cup of coffee. Her glance is situated to one side. She smiles widely, as though a visiting friend has just cracked a joke in the middle of an intellectual conversation.

This suaveness is both cerebral and social. Her gaze radiates a curious but self-as sured glow. Her eyes emit warmth while subtly graying hairs frame her forehead. Though the image is staged, her ease con vinces the viewer otherwise.

I cannot look at this without thinking of Sontag’s own words: “To take a photograph is to participate in another person’s mor tality, vulnerability, mutability. Precisely by slicing out this moment and freezing it, all photographs testify to time’s relentless melt” (Sontag, On Photography). Though the photograph has come to represent Sontag’s persona, it is, in actuality, a split-second, brief, curated access to her world. To place

eternal value on an image is to reveal the deeper impulse in capturing a subject: to memorialize. To see Sontag in this image is to commemorate her.

Perhaps the book beneath that pho tograph, sitting on my bedside table and spanning over 800 pages, would allow me entry into her world. It would also make me the person who has actually read a Susan Sontag biography. I’d probably be better for it.

But for now, I’ll keep it on my bedside table. Until I’m willing to follow through, or until the day I admit to myself the limita tions of my willingness to see the full picture.

I can't say I've ever been a superfan of anything. For the most part, I missed out on the mass hysteria of mid-2000s preteen ogling over One Direction and the Jonas Brothers. This isb't because "I'm not like other girls," but more because my parents banned Disney Channel and only played 80s disco hits in the car. I wasn't entirely separated from pop culture as a pubescent girl, though. I crushed hard on Draco Malfoy and fervently read each and every teen dystopian novel I could get my hands on. Yet my affection for Draco Malfoy's sly smirk and what I believed to be the literary genius of Divergent never extended particularly far.

Perhaps it is my distance from the modern "stan" that piques my interest in what makes them tick. I am in a sort of twisted awe of the devotion, the dedication, and the limitless ador-ation that such disciples have for their idols.

In anticipation of a recent haircut

appointment, my friend and I scrolled and pinpointed internet reference photos to show our respective stylists at the salon. My friend had prepared screenshots of Monica from Friends. I had images of Rachel. We both find the show to be entertaining, but our interest in the series admittedly stems from the show’s aesthetics. I appreciate Jennifer Aniston’s beauty both now and when Friends first aired, but I can’t say there is any part of me that wishes to resemble her beyond matching highlights.

It’s no surprise that young people use their celebrity idols as inspiration for their appearance. The entire business of celebrity sponsorships and the foundation of the influencer economy relies on the desire to look like those we admire. But there are thresholds where admiration contorts into obsession. Where a want-to-look-like twists into a want-to-be.

We’ve seen the news stories of those who take plastic surgery too far in desperate attempts to look like those they adore. They inject, pull, and whittle away at their features until their faces are hyperbolized caricatures of human beings. Those who go under the knife time and time again to wholly transform their image sit with a pleased nonchalance during interviews with TMZ or People or The Sun.

It makes me wonder if these individuals are truly happy with who they turn themselves into. Are they content, or is it denial that drives their emotions? It also makes me wonder who agrees to perform the operations desired by those obsessed with attaining the unattainable. Are they wrong for irrevocably changing features,, or are they simply doing what the customer wants? Besides, plenty of individuals use photos of celebrities for their dream noses or chins or breasts, so where is the line that demarcates inspiration from unhealthy obsession?

It’s 2008. The gentle curvature of prehistoric flip phones can be seen outlined in the velour of Juicy Couture tracksuits everywhere. Hair is teased and bouffanted to the gods. Lips are icy and eyes are lined in black kohl. Over-saturated, collaged paparazzi images of Paris Hilton and her contemporaries cover the facades of magazines lining the grocery-store checkout lines. Their wealth, youth, and beauty are flaunted to masses of adolescents waiting behind their caretakers while a store clerk slowly scans produce.

It is no surprise, then, that prepubescent tweens idolized these sparkling figures of luxury and glamour. Middle schoolers everywhere layered their tunics over lowrise jeans. Small dogs, real or toy, suddenly materialized in purses. Yearning to one day be as cool, as skinny, as sultry as Paris Hilton or Lindsey Lohan or Amanda Bynes.

Some invited this idolization into the rituals of their young lives. Those who lived far from Southern California adopted the catty superficiality of the Hollywood elite. Others dressed in tight, short clothing that made their mothers’ lips purse together.

Then there were the ones who would do anything, anything at all, to be Paris or Lindsey or Amanda.

In October of 2008, a group of seven teenagers, dubbed “The Bling Ring,” broke into the home of none other than Paris Hilton. Over the next year, this group went on to rob over fifty celebrities, stealing approximately three million dollars worth of cash and luxury goods. Their motivations were two-fold. One, celebrities were public figures. Their whereabouts were constantly reported by TMZ and other celebrity-focused publications, so the Bling Ring knew when

image

image

certain homes were vacant and open for the taking. Two, the group wanted to live the luxurious and glamorous life that Hilton and her contemporaries so publicly touted. The culprits chose Paris, as well as their other targets because of their inexhaustible reservoirs of affluence and highly influential style. They stole that which they themselves so badly wanted. One of the burglars even referred to their antics as “going shopping.”

Paris Hilton’s brand, persona, and being were centered around her seemingly limitless wealth. Rooted in stark materialism, her life of partying and leisure quickly became the aspiration of the masses. In this way, it’s no surprise that Paris (and her fellow targets) were robbed of the items so intrinsically tied to their public image: designer clothing, jewelry, and cash.

Even when facing the legal repercussions of her actions, Bling Ring Member, Alexis Neiers, wore Bebe kitten heels to her trial. An unremitting fixation on demonstrated, embodied wealth.

When I was in the sixth grade, my main interests included hiking, watching Modern Family, and riding on my friends’ razor scooters. I wasn’t particularly literate in internet culture at the time, but I had friends who were. They would show me videos like “Charlie the Unicorn” and let me play on their Minecraft servers. Somewhere around that era, a few of my more culturally-aware friends told me about “Slender Man.” I, of course, had never heard of the mystical being that

first appeared in the dark corners of the Internet, slowly spreading across online forums like an ink drop in a pool of water. When they told me his origin story, I didn’t think much of it. Though I was spooked at the time, I moved on with my life.

Slender Man’s influence manifested differently in the lives of Anissa Weier and Morgan Geyser, two young women who met in the sixth grade and bonded over their shared affinity for the elusive

demon. As their friendship grew, so did their investment in Slender Man. Their fascination gradually morphed into obsession, leading them to commit heinous crimes as Slender Man’s proxies. Ultimate devotion was confirmed by stabbing their friend, Payton Leutner, nineteen times in 2014 after luring her out into the Wisconsin wilderness.

This particular example of violent obsession is especially relevant considering Weier is to be released from prison in the coming weeks. In the eyes of the law, she is properly rehabilitated. She is considered “good” and psychologically recovered from her murderous behavior. Leutner’s family disagrees.

While Weier and Geyser may be the youngest perpetrators of such terrible crimes, they are certainly not alone in their homicidal expressions of affection. Mark Chapman was a fan of John Lennon. He went on to shoot John in the archway of his apartment. Yolanda Saldívar was the president of a Selena fan club. Saldivar shot Selena in 1995. Followers of Charles Manson carried out murder sprees, spurred by devotional fanhood.

The blurring of the lines between adoration and demise occurs with horrifying frequency—bringing new meaning to the phrase “I love you to death.” Case studies such as these leave us wondering: how does love become so dark? Perhaps answers can be found in the places where infatuation conflates with potent peaks in consumer culture, with an ever-pervasive internet landscape, or with the precarious faultlines of capitalism, wherein constantly expanding markets try to sell us flattened, re-packaged notions of beauty and ultimately, happiness.

this is her!

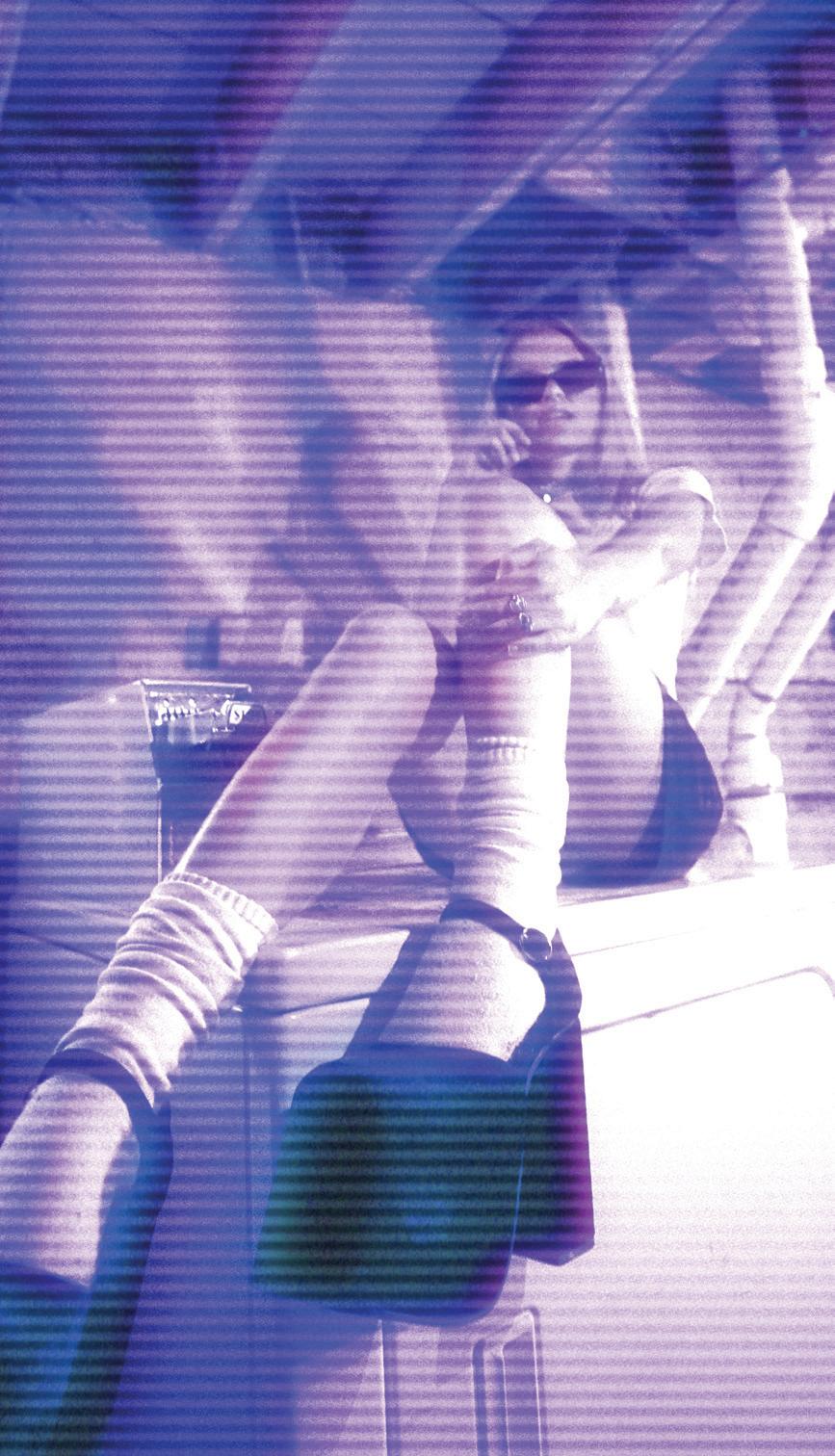

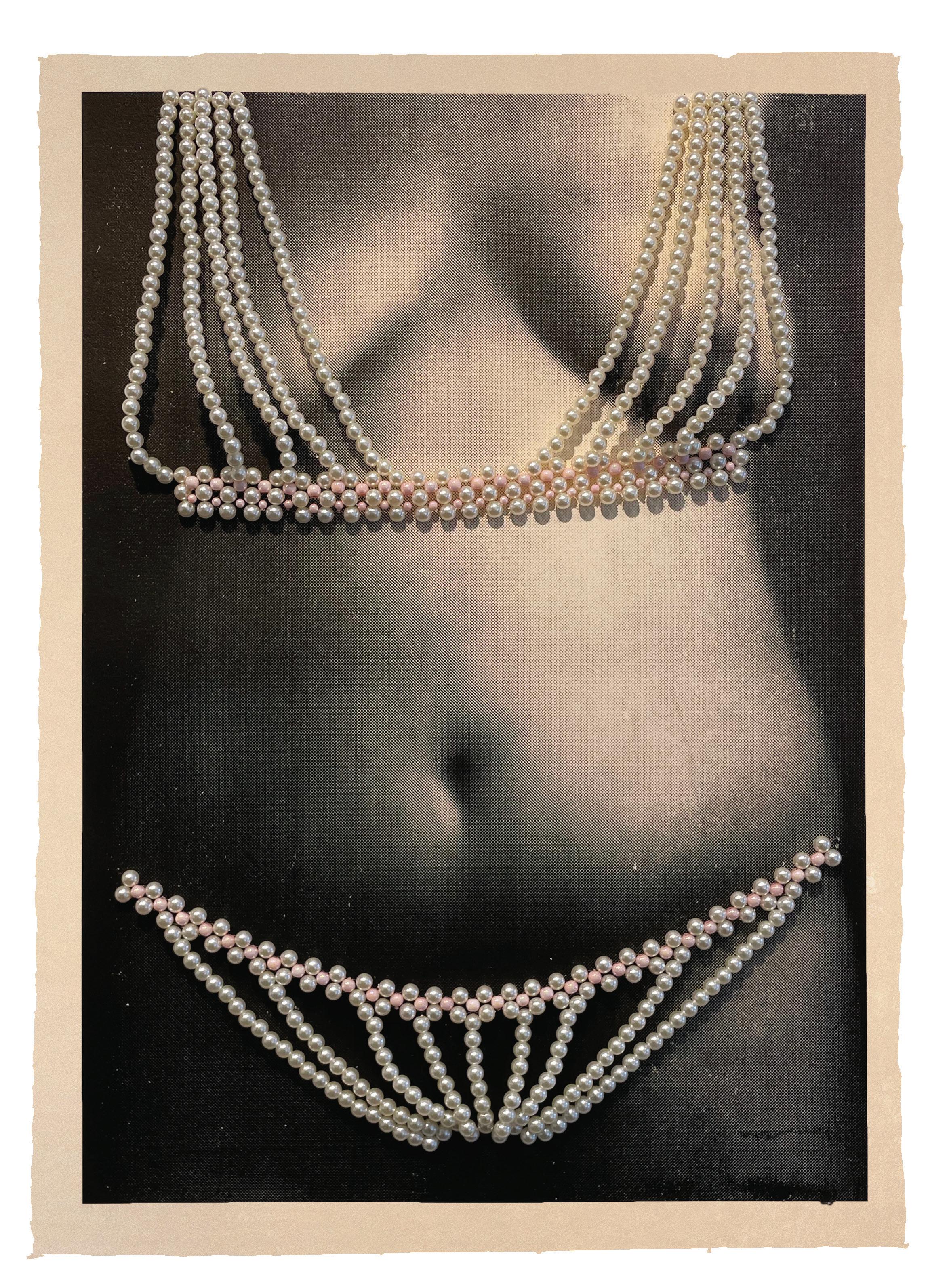

I first met Avery Johnson in early October. She invited me into her palace: a studio at the Sam Fox School of Art and Design. Located on the second floor of Bixby Hall, the room is a balance between empty spaces and pockets of mess.

Materials of budding creations emerge from every corner: a string of pearls bubbles out of a half closed cabinet, red fabric is clumped in the corner, a white feather boa constricts around the ceiling scaffolding, drying ink prints meditate on a window ledge, and a single pink ostrich feather tickles the granite floor. I find bot tles of glitter, copious ink, toys, doodles, and power tools on her supply rack. The studio-cube is enclosed by empty white walls, with the exception of a small col lage of copy-printed photos facing a sturdy desk. One steel table, pushed up against the opposite wall, holds a mini TV and a tray of hot pink lighters. Two gigantic win dows keep the room flooded with natural light and views of Forsyth. She offers me a seat in a cheetah patterned, stiletto shaped lounger, while she perches in her desk chair. Avery’s zebra-printed loafers dangle a few inches from the floor.

Sam Fox students spend most of their time in their studios. Avery is known for liv ing in hers. Whether working weeks ahead on a school project, prepping upcoming events for her art collective, or perfecting a passion piece, Avery is always creating; for better or for worse. “It’s not that I want to make things, I need to..... I have to, I get a little crazy about it,” the BFA senior states.

Avery draws from a wide array of mediums such as photography, printmak ing, and fiber manipulation. Her work is an active meditation on themes in her life. Avery tells me about the collage of photos above her working desk, her “mood board,” as she calls it. As she recalls each artist and work, her eyes dart energetically from the photos to me and back as she describes her biggest inspirations. The wallet-sized printouts depict pieces by photographers and artists like Laura Aguilar, David Hammons, and Francesca Woodman. Diverse in media, approach, and age, all of the artists seem to focus on representing their bodies as the subject of their practice.

“I’m interested in artists who use their bodies as compositional tools,” Avery explains. “My go-to line for artist statements is body as subject and substrate, so the body that is being depicted is also the tool being used to make it.”

Avery takes the time to walk me through the biographies of each of her favorite artists, pinpointing dates and names off the top of her head. She has a clear knowledge and appreciation for the radical artists that came before her along with their unabated confrontation with self identity. Avery’s own work reflects those same values, she understands the subversive power of the personal which she boldly wields.

She offers me the box of pink lighters which, upon closer examination, each depict different proportions of a woman taking her shirt off. The woman is, of course, Avery. Lined up in a row, the shades of the lighters transition from baby pink to fuschia and back again as each one depicts a different part of the process. The stark white of her shirt contrasts the dark shadows created by the contours of her body. Avery’s face is never revealed. What I had initially thought to be just cute, pink lighters now held me captive. Each lighter is a frozen moment of some thing equally vulnerable and benign.

Avery explains that the idea behind the piece is to observe the body through the eyes of modern day capitalism, especially in relation to sex work and exploitation of the female form. For her vision to truly come to life, Avery want ed an audience to react to her creations.

An installation of the lighters was displayed in Steinberg Hall from October 4th to 18th, 2021. The lighters were presented in a pink case which had “$1” written across the top. Next to them, she placed a glass tip jar. Avery char acterizes the display as a “prolonged performance” because she was more interested in how viewers might inter act with the lighters than any quality of

the objects themselves. How many lighters would be taken? How much money would be in the jar? Which lighters would be left?

“Because the images are stills from a video of me taking my shirt off, there’s a really awkward moment the viewer has to make in deciding which level of boob they are gonna take. Surprisingly, the most boob ones have been taken the least,” Avery comments, sifting through the remaining lighters.

At the end of each day, Avery would go to Steinberg, meticulously log the progress, and restock the case. This process was repeated until all 150 of the lighters she made ran out. She found that about half of the lighters were being stolen. When I ask her how much money she had made so far, she quickly guesses around $20, but seems less interested in her profit than I am. As she continues to admire the whittled down case of lighters before her, I can tell she is just happy that her work is leaving an impression.

You wouldn’t know it from looking at the lighters, but Avery was having a bad day when she shot the stills printed on them. Partly because of her demanding role as both subject and photographer, partly because she didn’t feel like taking pictures of herself that day.

“It’s a really taxing process because you have to take these pictures of yourself, then you have to look in your camera, and try to look at the images from an artistic perspective, but at the same time of course your mind is thinking ‘I look disgusting. Why am I doing this?”’ Self-portraiture is the genre Avery has become most familiar with, creating both out of the con venience of being her own model and also the nature of her inqui ry. While Avery is often her own model, centering her body in her work is not comfortable territo ry. Like many of us, she has days

where body insecurities invade her mindspace. What sets Avery apart is that those days are what fuel her to confront societal issues through personal exploration and inventive methodology.

“With the type of topics I’m addressing, like body image issues and the sexualization of the female body, it doesn’t feel fair for me to subject another body to that same ridicule. I feel like if I want to explore these issues that come from a place of deep pain for me, I need to use myself to do so.”

The pursuit of authentic expres sion in spite of discomfort charac terizes Avery’s artistic dedication. It allows for catharsis. Creation is a necessity for Avery; it’s how she navigates the world and makes sense of her experiences. This ability to repurpose strong emotions into tan gible forms has tantalized her since middle school.

Avery’s upbringing in Los Angeles is inseparable from her artistry. The city’s influence, both

IT’S A REALLY TAXING PROCESS BECAUSE YOU HAVE TO TAKE THESE PICTURES OF YOURSELF, THEN YOU HAVE TO LOOK IN YOUR CAMERA, AND TRY TO LOOK AT THE IMAGES FROM AN ARTISTIC PERSPECTIVE, BUT AT THE SAME TIME OF COURSE YOUR MIND IS THINKING ‘I LOOK DISGUSTING. WHY AM I DOING THIS?’”

generative and at times, harmful, has led her to topics and mediums that she continually revisits, while also ingrain ing long-lived insecurities.

“I felt different in a bad way because I wasn’t as thin or as pretty as everyone else. The atmosphere of LA has this lasting sense of ridicule and superfici ality,” Avery says.

Avery’s first exposure to celebri ties wasn’t flipping through the glossy pages of magazines. Instead, she was seeing them everyday around town and going to school with their children. However, she explains LA’s impact on her burgeoning self-esteem without even a twinge of resentment or regret in her voice. Avery’s frank reflection suggests that she has come to terms with her inner struggles, even if they have yet to be fully conquered.

In a time where Avery felt like she didn’t belong, she clung tight to spaces where she could flourish. Filmmaking was the first medium to pique her inter est because it gave her the opportuni ty to be experimental. To create the worlds of her imagination.

Avery’s early film work prioritized cinematography and production design. Although the artist has since expanded her range of mediums since middle school, she is still in touch with her filmic origins. Recently, Avery has been spending time creating videos and gleaning still shots from them. She often displays photos in series, giving the illusion of motion. Photography may seem like a natural transition for a young cinematographer, however, Avery recalls that it was actually a fam ily competition that sparked her craft.

freedom. At the same time, Avery is acutely aware of her role as an artist, and aims to heighten and critique the theme of viewership in her photography. Describing her current practice, she explains,“I incorporate layers of separation between the subject and the view er, like shooting screens or having something in front of the camera lens. It’s about the process of feeling aware of being watched.”

Avery has honed this awareness, from her LA upbringing to becom ing an icon herself on WashU’s campus. Her idiosyncratic and unapologetically funky style cannot help but garner attention from her peers. It even gave rise to an unof ficial fan club consisting of a few keen onlookers who enthusiastically discussed Avery’s fashion sense and artistry to anyone but her. Avery, laughing in confession, says, “The fan club was three people who were obsessed with me and would freak out when they saw me, but then never bothered to get to know me. They liked this picture that they con structed of me, but didn’t bother to penetrate beyond the surface.”

Yet Avery’s openness from the moment I clicked “record” con vinced me that her eccentric authen ticity is not just for artistic production, but is rather an embodied value she practices in her everyday life.

Perhaps Avery’s brief confron tation with iconozation herself fur thered her fascination with women from history who found themselves under public speculation. Marilyn Monroe, Brittney Spears, and Princess Diana are all figures who