Cities and Urbanism & Research and Methodologies

Figure 1.1. Times Square Drawing. Source: https://brentyezek. files.wordpress.com/2010/05/nyc.jpg Artist: Brent Yesek10

Photo 1.1. Chuo-dori in Ginza, Tokyo. Source: National Geographic Photographer: David Guttelder 11

Figure 1.2. Couples dancing Latin American Rhythms in Belgium. Source: https://www.visitbruges.be 12

Figure 1.3. Central de Abastos, Mexico. Source: www.forbes. com.mx 12

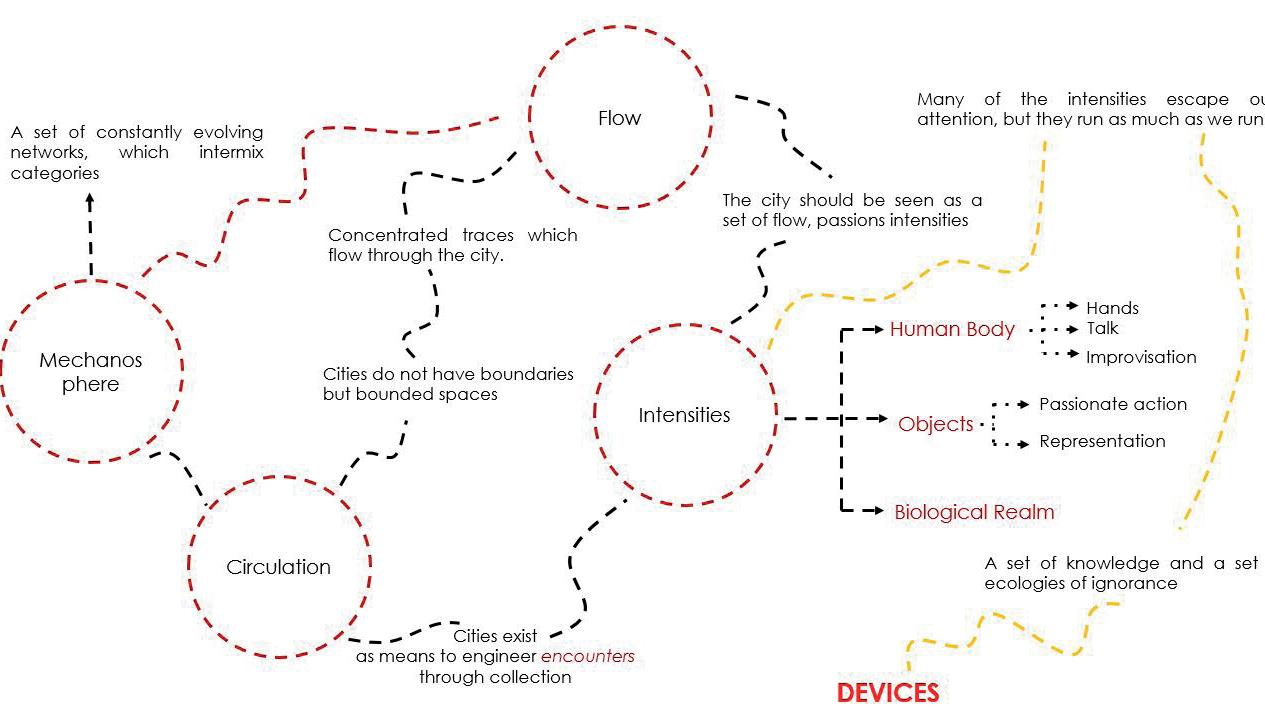

Figure 1.4. Devices enable City’s encounters to be recorded. Source: Reimagining the Urban - Book Presentation 13

Photo 1.2. Night Markets in South Korea: Namdaemun Market. Source: https://global-geography.org 14

Photo 1.3. Placemaking in Nairobi. Source: https://medium. com/placemakingx/leading-urban-change-with-peoplepowered-public-spaces-e77a23c07731 15

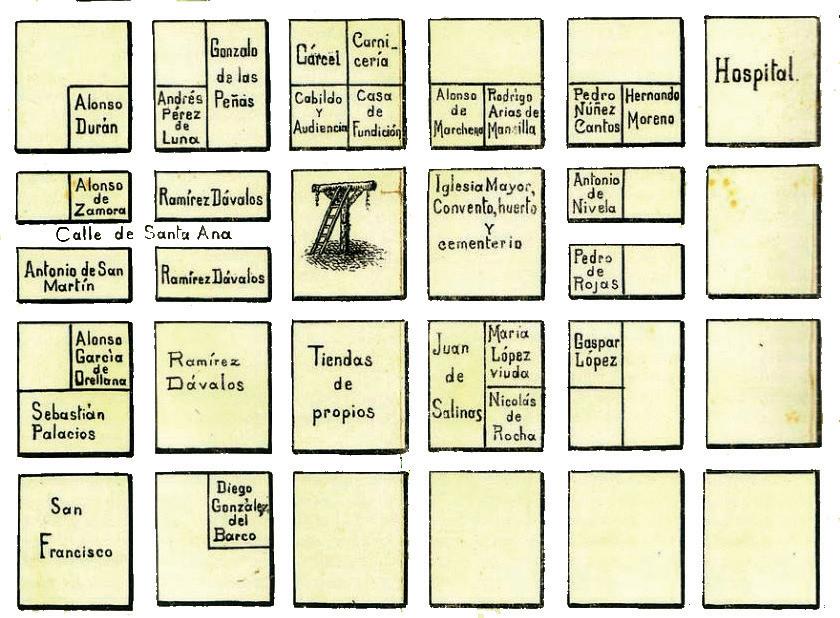

Figure 2.1. First plan of Cuenca-Ecuador with names of specific places, 1915. Source: Municipio de Cuenca 18

Photo 2.1. People queing for Wimbledon Tournament, 2018. Source: https://www.eturbonews.com/227048/fans-andtourists-queue-early-for-wimbledon-2018/ 19

Figure 2.2. “Distanciated”communities and economies form places which result in cities. By author. 21

Photo 2.2. Community engagement in Vancouver-Canada. Source: https://vancouver.ca/your-government/how-we-docommunity-engagement.aspx 23

Photo 2.3. Children from Cuyabeno-Ecuador returning to their homes. Photographer: Segundo Espín 27

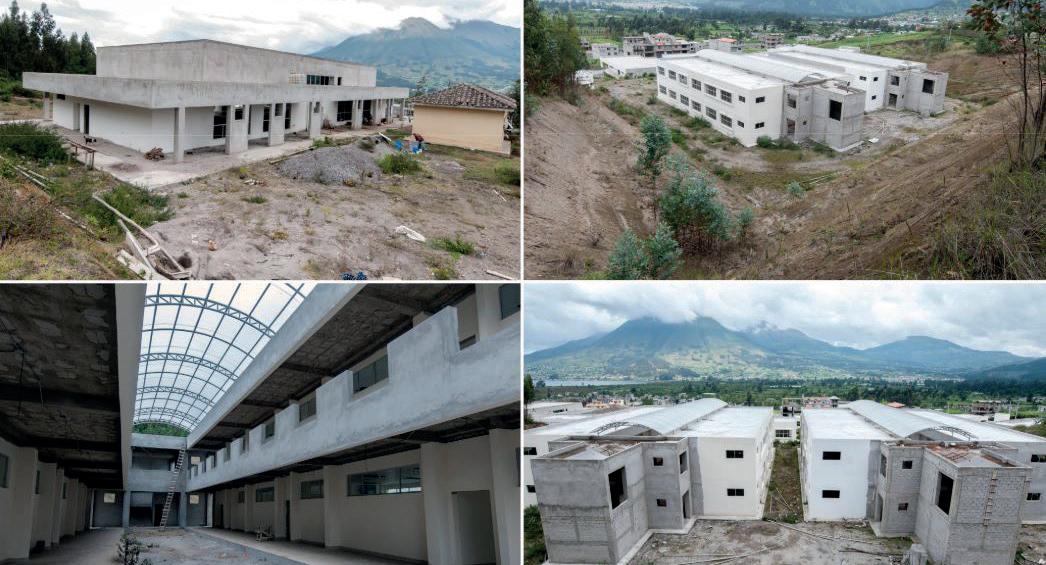

Photo 2.4. Abandoned school in Otavalo-Ecuador, requires 4 million USD to complete its construction. Photographer: Segundo Espín 27

Figure 2.1 Research’s Methodology utilized in Studio A and Dissertation. By Author 29

Photo 2.1. Fallowfield Loop in Levenshulme.By Author32

Figure 2.2 Allotments brief. Source: MA A+U Studio A’s projects’ brief, 2019. 32

Figure 2.3. Case comparison between Manchester and Bristol. Source: Studio A: Group 2, 2019 33

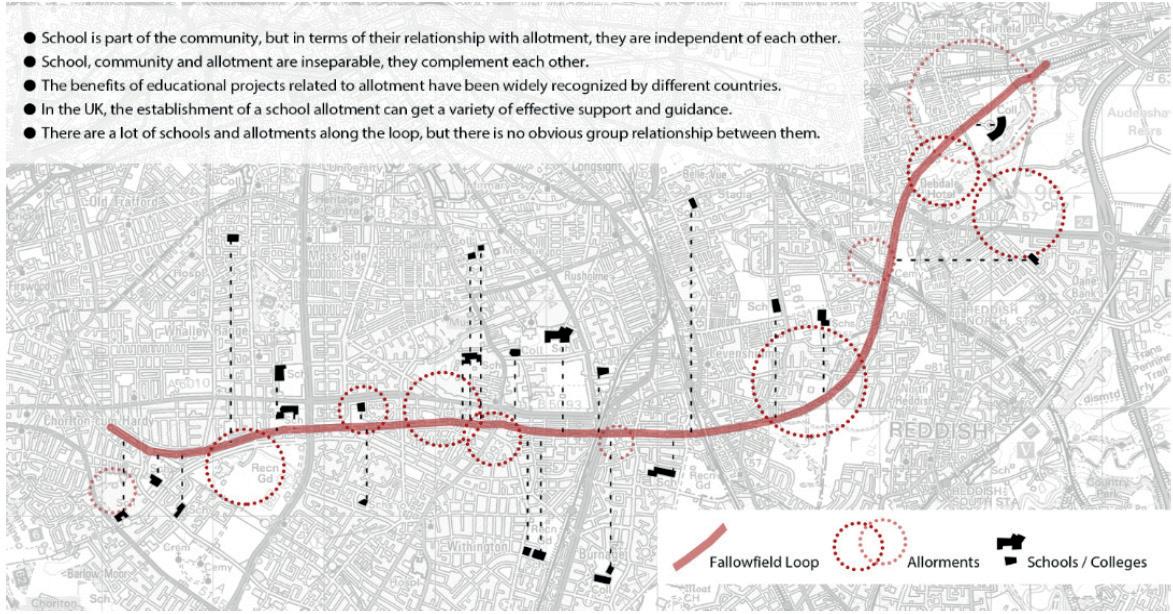

Figure 2.4 Schools proximity to the allotments and Fallowfield Loop. Source: Studio A: Group 2, 2019. 34

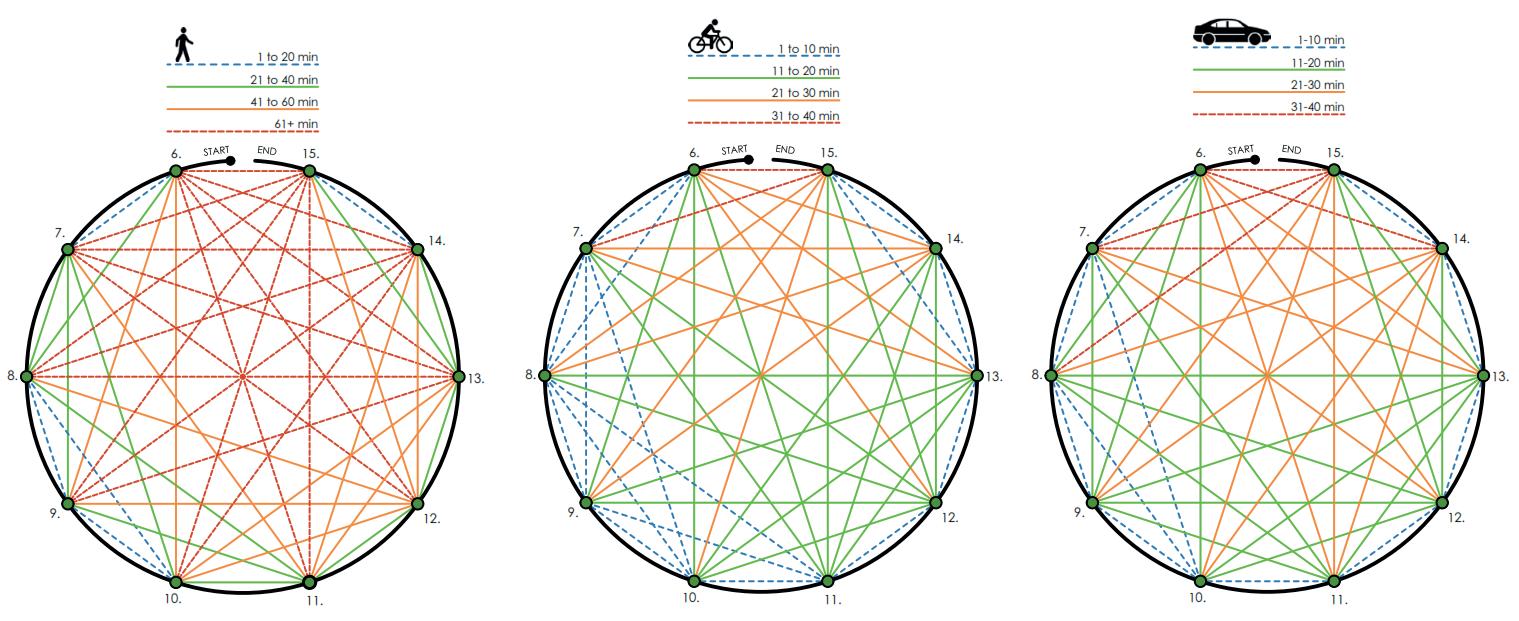

Figure 2.6. Time of travel with different means of transportation within Allotments near the Fallowfield Loop. Source: Studio A: Group 2, 2019. 35

Figure 2.5. Time of travel from Picadilly Gardens to the Allotments. Source: Studio A: Group 2, 2019. 35

Figure 2.7. Research Process followed in Dissertation. By Author. 38

Figure 2.8. Al Zahia Case Study. Source: Sharjah Holding, 2017 39

Photo 2.2. Surveys being held. Source: Research Group of the University of Cuenca, 2018 40

Figure 2.9. First page of Survey . Source: Research Group of the University of Cuenca, 2018 41

Written by Ash Amin and Nigel Thrift, Cities: Reimagining the Urban presents a fresh and almost complicated perspective of the cities. The book, which uses examples mainly from northern cities, presents a contemporary theory based on human connections rather than those constructed on nostalgia. It explains how cities are more than spatial formations. Their density, heterogeneity and networks of communication throughout them are the result of diverse social interactions (Amin and Thrift, 2002). Making it complicated to agree on what counts as a city. This book has rich and complicated terms making it a difficult read. But the authors divided it in two parts, where the first one presents new ways of reading cities while the other presents themes of

analysis, such as: distanciation of economic activity and relations, the new atmosphere for interactions made through technology, power and democratic citizenship (Stevens, 2003). This essay reviews the book’s content in a synthetized way so the reader would appreciate this new way of observing cities and engage them to read it for its important and valuable input for understanding the urban.

The authors by compiling new ways of imagining the cities, have opened the door for new questions and possibilities for research. While learning how different human activities and interactions shape cities, this essay also makes a comparison with the book written in 1982 by Aldo Rossi: “The Architecture of the City”.

a. The Legibility of the Everyday City

b. Propinquity and Flow of the City

c. Cities in a Distanciated Economy

d. The Machinic City

e. Powerful Cities

Cities had become permeable both geographically and socially, they are a group of fragmented processes and social heterogeneity. And in order to explain and develop a contemporary theory about them, the authors avoid essential readings so they can focus on the mobility of the urban, in terms of flow and everyday practices. This New Urbanism is explained through three metaphors:

Transitivity, or porosity. Usually measured by the ‘walker’, whose direct contact with the city provides a linked sensibility with the space, language and subjectivity, aspects needed to read cities. Therefore gender should be taken into consideration as well, for its significance due to different perspectives and experiences provided by both men and women (Photo 1.1).

Rhythms; everyday life has different dimension and

flows at different frequencies; and these rhythms can be present and absent at the same time i.e. traffic light times, opening schedules for schools and shops, etc. The pulses of the city make people order and frame the urban experience (Figure 1.1).

Most spaces of the city have Footprints of simultaneity loaded with spatiotemporal tramlines, meaning that no matter where a space is located its history, trajectories and practices will cross them. And by understanding this, cities cannot be seen as an “ordered and segregated pattern of mobility”, instead it allow us to have a vision of cities with stretched patterns of communication.

With these new metaphors, the authors open the topic of how cities cannot be linked to just one way of reading them, consequently the city is a complex and abstract group of networks and encounters.

Source: https://brentyezek.files.wordpress.com/2010/05/nyc.jpg

In the second chapter, the authors continue the argument of cities as “sites of extension and extensive sites” by exploring the meaning of propinquity. For this they divide into four parts:

The Nostalgic City; a review to past urban theory, like the one written by George Simmel or Walter Benjamin, where the modern city is more loss than gain. Where past authors are against technology and ignore the possibilities that it has to create new forms of human communication.

Near and Far; there is a numerous variety of spaces and even the smallest ones can produce important social consequences. Because spaces, no matter their proximity, interact with each other.

Distanciated Communities; there are different types of communities, and nowadays they do not need to be physically present to co-exist. The internet has created a platform for people to socialize and form communities across the world. Groups of people can gather for small periods of time and disperse again, being part of a site for periods of time.

The Restless Site. Contemporary architecture has taken interest in creating places which can embody spatial stories, and spaces of belonging.

https://www.visitbruges.be

The concept of distanciation, which is based on the understanding of Urban Communities and how they can be measured and persist at a distance (Figure 1.2), has important consequences in the way we think about spatiality in the city.

Instead of seeing cities as Puntual Economies, the authors observe them as assemblages of distanciated relations of economies with different intensities. Because when we start to see clustered economic activities, after examinating them we find multiplicity of sites. The book presents three ways of reading the urban economy:

Cities as Sites of Economic Circulation, where the cities could be seen as sources of knowledge or sites of sociability where economic transactions can take place. Once we consider the growth of economic organization, the city divides into strong local interdependencies, making them sites of economic power.

Routinization of site practices, by observing the density of institutions that are placed around economic life.

Urban consumption is less through Local Provision. Cities become generators of demand becoming circuits of provision. Where the demand cannot be met through local supply alone (Figure 1.3). After seeing the impact of firms and how they are connected through different scales of economy, the authors question if local economies support firms in other ways.

Is difficult to theorize how this knowledge translates into economic benefit. And another aspect is that cities are not economic in a business sense, they are economic because they intertwine social and business scenarios. Cities and their business/source of income are dependent on the social nature of humans. These interactions are not forced on

In chapter 4, the city is seen as a mechanosphere, a set of constantly evolving networks, where technical is a fundamental part of life. This mechanosphere is composed by flows and intensities full of potentials. Something that can be explained through the notion of circulation.

Circulation is a central characteristic of the city. Cities exist as means of movement, as means to engineer encounters through collection, transport and collation. Cities do not have boundaries but bounded spaces, which are concentrated traces. These traces flow through the city. City becomes a set of flows, intensities that construct our everyday

life. And the everyday life as we know it today was born in the city through the invention of a world of objects. These objects, are devices that enable city’s encounters to be recorded.

Cities’ movements consists of many unintentional body movements which have been taught to us from early ages. Therefore it is complex to order or restrain bodies in a space of circumstance. Hence the growth of internet and computing development provide informational devices (Figure 1.4), which produce a structure of expectation and measure the ordinary.

Domination and power should be considered as impulses, passions that construct the world in particular ways. Such perspective is best seen by the Foucauldian idea of the diagram, understood as an impulse without determinate goals. There are different forms of governance such as bureaucracy, production, sensuality and imagination.

However, modern cities offers means of escaping governance in three ways. The first way of escaping power is by night (Photo 1.2). It provides spaces into which the forces of law can be regulated to a degree. People feel free, relaxed and less restrained during the night. The second way is by sound Today everything is structured around vision and observation. But governance does not just take place in the visual register, there is always the sound of

conversations and talking. It is impossible to detach the visual register from the other sensory registers. Finally is fantasy. Dreams and fantasies can only be partially controlled because they are partially conscious. City exists everywhere, in the mind of people, in postcards, in images and people trying to identify themselves through the indefiniteness of their cities.

To romanticize escape can become extremely dangerous. And it may seem that the city offers escape only by name. Urban spaces are not predictable machines for reproducing bounded and controllable relations. People experience cities in different ways, they use spaces not always for the purpose of their design.

This chapter argues an extension of universal rights in order to allow citizens to engage in politics because democracy lies in the democratization of the terms of engagement (Civic empowerment, and participation). Participation for some commentators promises the return to community and for others it promises a politics of difference based on plural cultural expression and identification. The authors discuss three influential visions of urban Democracy:

Public space / Public Sphere: Referring to public usage of open shared spaces with the emphasis on the construction of a civic public through mingling and interaction (Photo 1.3). Where public thing by themselves, not depending on their riches. And city spaces are seen as generators of new shared meanings and hybrid cultures arising from intermingling.

Deliberation: Is the practice for conflict resolution and problem solving. Community-based planning that is interactive and people-center through:

Listening, talking, being there, learn to read symbolic and nonverbal evidence and intermediating between stakeholders and community.

Radical Democracy: It refers to the democratization of institutions and empowerment of lower class voices in a political of vigorous but fair contest between diverse interests. And a way to achieve it would be by building a consensus around difference, and challenge oppressive power relationships.

The purpose of this chapter is to understand that institutionalized actions enhance individual and social capabilities. Citizens should not be counted as numbers of vote only but as active participants in the way a city forms. Democracy should not be seen as a menace to institutional activity, on the contrary, every person is bonded and connected to institutions and people’s opinion and best interest should be taken in consideration while taking

Source: https://medium.com/placemakingx/leading-urban-change-with-people-powered-

a. Locus and Propinquity

b. Architecture and Democracy

Locus as defined in Rossi’s book, is the relationship between a specific location and the buildings in it, both singular and universal (Figure 2.1). A place in time and city. Most of the buildings are placed around the urban fabric depending on different factors, but most take notable importance of the surroundings. In The Architecture of the City, there is the idea that singular points exist because particular events might have occurred, and they translate those by analyzing physical artifacts and their surroundings, in order to understand the locus.

Propinquity, on the other hand, is defined in Reimagining the Urban as the phenomena that can be measured and exists despite being distant to its origins. For this, they explain it while using Communal bonds which exist in the city and are represented in different ways:

• Planned Community; Such as tracking of motion elements like postcodes, surveys, census, polls,

• Post Social and post human; where all relations are modified by technology, making humans interact with objects.

• New Forms; where groups are gathered for a period of time and then they disperse again, and also within groups that depend on technologies to overcome distance such as the internet to survive, like people who like pets, vegetarianism, food blogs, etc.(Photo 2.1)

• Diasporic Communities; Connections created by human mobility.

• Everyday life; what is left over, a community that cannot be classified. A community where people co-exist without sharing any representable conditions of belonging.

Figure 2.1. First plan of Cuenca-Ecuador with names of specific places, 1915. Source: Municipio de Cuenca

https://www.eturbonews.com/227048/fans-and-touristsqueue-early-for-wimbledon-2018/

• Sympathy; where people through media can connect and create organizations and other support groups to help communities across the world.

All these in group, form the 3 R’s of new urban life: New Social Relationships, New Means of Representation and New Means of Resistance (Amin and Thrift, 2002). Generating a more “Distanciated” mode of belonging. A first person’s perspective sort of speak, to explain how cities are more than just buildings.

While Cities: Reimagining the Urban presents a contemporary theory of reading and understanding cities, Rossi’s book focuses on the Locus and Urban artifacts, an external viewer perspective. Where architecture is the tool to comprehend the history and take the latter as a structure for urban development. As Viollet-le-Duc stated‘…the house offers the best characterization of the customs,

usages, and tastes of a population; its structure, like its functional organization, changes only over long periods of time.’ Le-Duc talks about typologies, and architectural principles. Grids and plans. Where they could get a glimpse of the history of social classes based on reality, anticipating social geography.

Aldo tries to emphasize the fact that through architecture, perhaps more than any other point of view, one can arrive at a comprehensive vision of the city and an understanding of its history. But he also states: “Ecology as the knowledge of the relationships between a living being and his environment cannot be discussed here. This is a problem which has belonged to sociology and natural philosophy ever since Montesquieu, and despite its enormous interest, it would take us too far afield”.

Such discussion takes place in Cities: Reimagining the Urban. While those relations and interactions

have been overlooked for being distinct to architecture and urbanism, in reality they develop the basis of the architectural form and urban. Cities has definitely proposed a way of understanding that human connections are invisible but palpable. Cities are not only seen but also felt with our other senses, through sounds, experiences or life itself. And in previous theories these invisible aspects are the result of architecture, and in Cities’ new theory, spaces are shaped because humans exist and interact.

Rossi’s tries to explain the Locus between the space through architecture and the city, meaning that one specific place is bounded to others through its structure and experience. Comparing the Locus to Propinquity, both talk about connection and links. Rossi’s perspective is more spatial while in Cities is more community focused.

Relations between spaces can be seen through plan analysis and map viewings, but communities need patience and special attention to different connections that are invisible and have not been taught, like it was mentioned before, there is multiplicity of communities and its visible result is often seen as understandings or participations, but not as graphical as architecture.

Aldo believes that architecture responds to a specific time both socially and in history. That any change or evolution can be seen on the level of aesthetics. And for Rossi there is a clear difference between urban artifacts and urban design, for which he explains that the first one seeks laws, orders from a plan; and they are acceptable when they only approach one part of the city. When in reality, as Reimagining the

Urban has established, the city is a complex mesh of networks and it works as a whole. We cannot think of urban design by dividing the city, because it merely has clear boundaries to delimit it. While Rossi’s thinking may seem reasonable, the reality is often more difficult. Urban artifacts allow us to read the history of a city but urban design is responsible of combining new ways of understanding and solving the city while respecting our past. As Rossi states “…forms in the very act of being constituted go beyond the functions which they must serve; they arise like the city itself”, meaning that architecture is the scenario in an ongoing play, with different actors and stories. Cities cannot be defined by solely form or function, neither controlled or organized and be separated from buildings. They need understanding from multidisciplinary perspectives in order to construct a responsive city.

Aldo’s point of view is architectonic. Buildings have their value and should not be ignored in the city. Amin and Thrift’s one is palpable. It connects architecture through human interactions as they shape spaces. Adds value to the human nature while describing the places and instances where it gathers. Both perspectives are different but equally important. As architects we are responsible of solving problems for different users and parts of the urban, by understanding it and making it a basis of project, we are also responsible of designing little pieces that would be part of the city.

The main difference between Locus and Propinquity is how they are read in the city. Both terms are bounded to proximity and distance, to an interrelation despite a separation. One is based on infrastructure

while the other one is related to socio-economic networks. While the first one will help to understand the formality of the city, how buildings are linked to history and the individuality of cities, we should not forget the function, and for that Cities has shown that architectural occupation is beyond its walls, and human behavior has important results in the way cities are shaped. Their activities, relationships and desires are within cities and mold the urban while

they exist. Individuals form communities despite the location, meaning that a city’s individuality is in a way the particularity of these groups (Figure 2.2). Its characteristics and values vary in number and appearance across the world and for that, urbanism and architecture books from the past, might have disregarded its importance of analysis.

Once again, in terms of politics, both books observe it from different perspectives. As Aldo mentions in his book, urban development depends on the nature of forces but also on the context where the city rises. It is essential to establish a connection between these two aspects and one way to do so is formulated in Cities, through various ways of linking both infrastructure growth and communities.

In Rossi’s book, he is interested in exploring the relation between urban growth and land speculation. He uses a couple of thesis based on economics to provide insights into the nature of urban artifacts.

The first one is Halbwachs thesis, and it talks about the nature of expropriations and how economic conditions arise of necessity. And expropriations occur when economic growth demands it.

Halbwachs mentions that the increase of institutions changes the order and aesthetics of the city, and it needs to be analyzed, if after all the economy aspects are deleted, what is the true value of buildings.

Rossi touches a good point by mentioning that “… the collective consciousness can be mistaken; the city can be induced to urbanize lands where there is no tendency to expand or to build streets where none are really needed…” In Cities, they mention that citizens should not be counted as numbers only,

their opinion needs to be taken in consideration at the moment of making decisions, especially in terms of city growth and infrastructure. Urban growth due economic factors arrives from resolutions or choices that not necessarily involve the population of a particular region, therefore we result with useless infrastructure for its immediate communities.

“A modern study of this type derives considerable support from the study of urban plans for expansion, for development and so on. In substance these plans are closely linked to expropriations, without which they would not be possible and through which they are manifested.” The essence of this chapter is the purpose of expropriations and its basis on urban development. How without them, many urban and architecture projects would not be plausible nor built.

Bernoulli’s thesis states that private land ownership and its parceling are the principal evils of the modern city since the relationship between the city and the land it occupies, should be of fundamental and indissoluble character. He therefore argues that the land should be returned to collective ownership.

Cities compose themselves with layers of history and infrastructure. Expropriation removes existing spaces to create new ones, and many of those extractions

“Expropriation does not occur in a homogeneous way in all parts of the city, however, it changes certain urban districts completely while respecting others more.” (Rossi, 1982)

are done without citizen’s opinion nor best interest (Jácome, 2017). Social participation, as stated in Cities, covers a wide range of personal interactions where consensus can be reached, therefore cities can be constructed with a strong societal basis.

Urban growth and Socialization should be bonded. They should be in a mutualism relationship, where both parts can benefit. A city’s development cannot exist without valuing and enhancing citizenship.

In Cities they use three examples to show that socializations is vital within urban development:

• Publicity: Projects should be published in order to inform people about new interventions. The use of media must be potentiated so distant communities can be involved as well. Personal engagement should also be part of a project’s development.

• Sociability: Using measures of conviviality which produces public events, and opportunities to create new sustainable projects (Figure b.1).

• Civic Duty: In order to involve people as politic elements, they need to “experience negotiating diversity and difference” And one way to encourage them is through accessible incomes, such as education access, training certifications and such.

Through the methods mentioned above, expropriations and urban growth can fully be responsive to its citizens, who will be actively involved and equally responsible for a city’s progress.

Across urban literature, there is always differences, points of inflection and similarities. By reading the books mentioned before, the differences are clear. Architects and urbanists are generally interested in the connections and formalities that influence the shape, space and development of cities. While not completely ignoring, but definitely overlooking the power of invisible connections, such as the ones mentioned in Cities: Reimagining the Urban. The latter should definitely be taught between architecture schools to bond the professional and the citizenship in a more sustainable manner. We should ask the city what it wants and it will definitely answer back, and with our profession, canalize those needs and questions into factual institutions or policies, so we can construct and progress into more inclusive cities.

While the book Cities is from the early millennia, it is important how much of its content adds to contemporary urban analysis. It is significant how in some places around the world, in order to go forward with urban or architecture projects, they involve the citizens from the area in order to socialize with them the aspects and benefits of said project. While this is an important and positive step, there is no guarantee that people in charge of such socializations would listen or pay any

attention to the communities involved. In many cases, they will just comply with an agenda and do what the head in command dictates. Such is the case of public schools in some cities in EcuadorSouth America, where a new populist government, under its new “inclusive” and “accessible” lemma, built educational institutions with a socialization based on the hopes for the future, where no real aspects where mentioned, such as how they were going to close some schools in the rural area so all the children can move to a bigger school, distant from their homes, making them wake up and get ready in unreasonable hours in order to arrive early. This example, not only happened with schools, but also with bigger urban projects where costs and benefits were mentioned but not obeyed at the end, concluding with overpriced buildings that were soon closed due to its incompletion or inoccupation (Figures 2.3 and 2.4) (Pérez, 2019).

Urban projects have changed its way to be thought and developed in the last decades, while there is hope that we could involve more citizens and communities in the process, we should be careful and more alert with authorities, politics and people in charge essentially, so we can guarantee a successful and sustainable urban growth.

In Studio A, the project was focused on the Allotments of Manchester while the Dissertation was about a contextualization of an international assessment method in a local context; the factors that play in order to measure its indicators and how sustainability is measured. The following figure (Figure 2.1) shows the aspects that were considered for methods such as Literature review, case studies and interviews. The approaches between the

- History of the Allotments

- Benefits of using them

- Changes through history and their current policies

Remote

- Greater Manchester Allotments

- Bristol Allotment and Urban Farming

Personal

Interviews + Surveys

- 1 to 30 people

Personal

- Site visits while establishing journeys

- Photographs of the place

-Sensorial experience of the cycling route

Issues and potentialities for an architectural and urban intervention

projects were different because their aims were so. Consequently it can be seen in the figure what the results were of utilizing both quantitative and qualitative approaches.

This essay describes the research methods and methodologies used in Studio A and Dissertation. How these relate to the context and what aspects they cover in order to find the aims of the designated work.

- Definition of Sustainability

- Sustainability Assessment Methods

-Sustainable development and its meaning

-Objectivity in Sustainability

-BREEAM method and background

-BREEAM definitions of sustainability

-BREEAM certified Projects Remote

- 132 residents of the project

- 1 to 3 developers of the project Personal

- Evaluation of BREEAM sustainability method when applied to a local context

Analysis of the results of an evaluation that will help to determine the flexibility of a sustainability assessment method when applied to a local context

Figure 2.1 Research’s Methodology utilized in Studio A and Dissertation. By Author

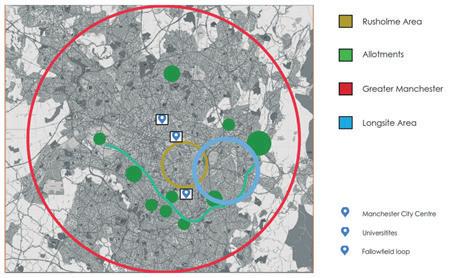

Studio A’s project was focused on the Allotments located in Greater Manchester. Their importance as plots of land that functioned as places for working the land and feeding the country. Furthermore serving as places for gathering people, enhancing communities and giving room to important social movements due its nature of public spaces for the working class. The allotments in Manchester suffered a change and became plots of rent that privatized the activities that held place in them. In the first approach to the project, it was necessary to understand the history and the changes that the allotments went through in Manchester along with their location and proximity in the city (Figure 2.2).

As part of the research process, a mixed method was applied, meaning that both qualitative and quantitative research were used to find the problematic and develop strategies (Creswell, 2014:32). Methods such as literature review, case studies, personal experience, and data collection allowed the group to find and categorize issues and strategies to advance with the project. The process was structured in a way that with literature review we could revise the antecedents of the topic; with interviews and site visits, witness the present conditions and by looking at case studies, portray an image of what the project would look like in the future. Literature review, according to Creswell “… provides insight into ways in which the researcher can limit the scope…”; and for Studio A, was used to find the history and the importance of the allotments and the behavior of people around it, allowing us to have a previous idea of what issues and subjects could be researched.

Along with the site visits in Manchester (Photo 2.1), a case study in Bristol was selected to find the similarities and differences between these two cities (Figure 2.3). Case studies have proven to be methods of evaluation, which means that they represent a time and an activity, allowing the researcher to collect detailed information about a specific period of time (Creswell, 2014), and comparing the Bristol case study, it revealed how the allotment model was applied in different settings and how the results were aimed to different scales of people. For example in Bristol, had economic gains alongside volunteer work, something that was not implemented in

Manchester and could play an important addition to the allotment dynamic. These types of findings could only be achieved by seeking similar projects and analyzing them. Therefore, literature review provided a sufficient background, but the case comparison allowed the project to be witnessed in different settings. Additionally, questions are aroused about its importance in today’s society, such as why they are limited to private use, their location near the Fallowfield Loop and their disconnection with the former train line, and most importantly their potential to regain importance as plots of land that gather communities and enhance a sustainable way of living while encouraging people to grow their own food.

Therefore, the group discovered the issues while experimenting them. Maps were tools used to mark issues that could not be acquired in any library or archive. Meaning that, after visiting multiple times, we could see the potential and what the project could become. For example, the visit to the Fallowfield Loop brought a number of possibilities to reactivate its use and connect the allotments in the process.

After a number of visits, photographs and conversations with allotments owners and visitors, the issues and problems converted into strategies. The visits to the allotments and Fallowfield Loop, gave us the experience of the user, the people that had to live there on a daily basis, allowing us to connect with the project and the people. In a way, we discovered what the project needed while learning more about the context.

Several topics were picked in order to categorize the information and make maps and plans of action. For example, in terms of education, maps of its proximity to the allotments definitely helped to propose the utilization of the allotments as teaching tools for future generations (Figure 2.4). Or in the case of mobility, Figure 2.5 and 2.6, the allotment owner or visitor could use either a vehicle or a bike and reach the same destination at the same time. By providing a safe biking path, emissions would be reduced without impacting travel time to destinations. On the other hand, information about how the allotments were used as therapeutic tools

was used to back up the implementation of public allotments as a service to its citizens.

In conclusion, a mixed research methodology did not limit the amount and variety of information that the project provided, on the contrary, it helped to complement the sensorial experiences with data and statistics. This resulted in a multidisciplinary project with different research areas and personal opinions. The findings varied in scale, from mobility to owners’ perspectives, and they provided more context than literature review only. An urbanism and architecture project of this kind is difficult to achieve without sensorial experience and direct contact with

the people of the area. It is possible to document this, but over time these perspectives change so when a design is ready for proposal, records of these perspectives should always be updated, and this is only possible by contacting the user with the idea of the project in mind, so their input can be considered regarding a direct topic.

Most of the methodology for this project was qualitative with some quantitative complements. But when talking about architecture and urban projects, qualitative methods help the researcher to engage with the context, allowing the group to address aspects that were common alongside the Fallowfield Loop and the allotments, and also appointed separate scales of intervention so the project could answer the needs and concerns of its context and people.

Several sustainability assessment methods have appeared since sustainability became an aspiration in different countries, generating political summits to create commitments to achieve sustainability standards. Sustainability assessment methods gained traction as tools to achieve the aforementioned standards(Bond et al., 2012), but their credibility still remains questioned. BREEAM is the first international sustainable building assessment and they have certified projects around the globe (BRE Global Limited, 2012). Which not only shows their “flexibility” as a tool to measure sustainability in different contexts, but also demonstrates how several building developers have used their tool to certify projects across the world. Nowadays, BREEAM has a technical manual that according to its name, can be applied internationally, in order to measure sustainability in developments, understanding the latter as neighborhoods. In the dissertation work the proposed questions came to place in order to understand more about these tools and how helpful they really are:

Topics with Literature Review

• Is BREEAM Communities International applicable to local contexts?

• How flexible they are as a sustainability measurement tool?

• What are the repercussions of using them to assess sustainability in different contexts?

In order to answer those, it was necessary to elaborate on the topic, starting from the term that BREEAM uses in its entirety of the technical manual: Sustainable Development. Next, analyze certified projects and their similarities. And finally understand the local context where BREEAM will be used to measure sustainability and analyze the results of that operation (Figure 2.7).

The methodology used for this work was determined by literature review, analysis of cases and the application of the assessment method in a local context.

Analysis of indicators through surveys and interviews + Results

As a work based mostly on theory, the literature review was focused on the terms that BREEAM utilizes and how these methods came to be. First, sustainability, the compilation of articles is the only way to determine a definition and what aspects are important to reach sustainability, as it is theory and it is difficult to experience in order to elaborate an argument. Its value relies in scientific research and evidence, and after analyzing the term Sustainable Development, it was clear that the only way to make it objective was if all parts that use the term share the same interests and aims, which in the case of real estate is difficult to achieve, especially when using a tool to measure sustainability that is not being analyzed thoroughly and has proven to give prestige to the buildings that own sustainable certifications. Therefore, by finding articles that study the topic it was helpful to guide the scope of further analysis as well, for there was no scientific evidence that utilizing this type of tool will definitely improve the built environment and enhance sustainability. The literature review for this step of the research was key to finding what other authors have found about these assessment methods and what their questions were after finalizing their analysis. This helped to

redirect the research from finding which indicators could be applied in local contexts to questioning the reasons why BREEAM has an international assessment method and what makes it so.

The case studies allowed us to show the context where BREEAM was applied (Figure 2.8). Its size and cost of the project permitted us to find the common factors that certified projects had. By analyzing the cases, it could be seen what kind of projects were the ones that had more possibilities of achieving a sustainability certification. It also demonstrated that BREEAM was being applied in other contexts and certifying projects, which indicated that there was a chance that BREEAM could be applied internationally as its name says, but also it also revealed that most of the projects were freshly designed and built, meaning that they started an urban development using BREEAM certification as a goal.

Finally, the analysis of BREEAM indicators in a local context (Cuenca-Ecuador) was done with the help of the Research Group of the University of Cuenca, who provided the data collection from surveys and interviews with developers. The data collection

was guided by BREEAM’s indicators requirements, meaning that BREEAM’s technical manual was analyzed in order to determine what requirements were needed to achieve points in their rating system for BREEAM International Communities (BCI). Therefore, two groups of people were surveyed and interviewed: the residents of the urban development where BREEAM was going to be applied (Miraflores) and the developers of it. The surveys were held according to what BREEAM asked in their indicators, this interview was guided by a university tutor accompanied with researchers of the group (Photo 2.2 and Figure 2.9), who recorded the answers provided by government workers that were part of the development. The surveys, also conducted by the Research Group, were done by interns and members of the group. From 182 housing units, 132 were surveyed, and the purpose of the surveys and interviews was to collect information that will help measure indicators such as general comfort with their housing unit, mobility patterns and means of transportation, number of family members, etc. None of which could solely be collected by checking maps or taking photographs. BCI does assess developer analysis, but as these records are not available to the general public, an interview was the only means of obtaining this information.

The analysis showed BCI's broad scope may negatively impact projects, for instance in terms of sustainability, there are no generic terms, and everything is bonded to a context. In the case of Miraflores, several factors were measured but important ones were also left out. Working with the help of the university not only allowed for the collecting of information, but curation as well

since several people work on the project and their commitment to provide scientific evidence is strong and reliable.

Therefore, the research for the dissertation was separated between the literature review and the survey compilation. And the analysis was determined by the results of the survey with the theoretic background. Combining those two methods did not change the results of the analysis, on the contrary, they supported some claims that were found on the literature review.

participar en esta encuesta…

¿Se realizó un proceso de retroalimentación con las personas involucradas en el proceso de consulta, para detallar cómo se considerarán sus contribuciones?

¿La consulta consideró aspectos para la gestión del mantenimiento y cuestiones operativas?

18.4 ¿Se informó cuáles sugerencias se acataron y se justifican por qué no se consideraron

mantuvo informado sobre el progreso del proyecto?

The aims for Studio A and Dissertation were different, but similar methods were used allowing to reach those objectives. Three methods were common in both Studio A and Dissertation: Literature Review, Case studies, and Interviews.

For Literature review, in Studio A, it helped to guide the research and provide a background. In dissertation it was used to integrate what other authors have done and said, preparing the reader for the terms, and topics that will be addressed later. This method is essential in any research process, because it provides context around topics that will be looked into and have been addressed by other authors, it helps to see other points of view that could bring more research topics and finally because it shows how other authors approached their researches and help to shape the writing and presentation of similar works (Turabian, 2007). Therefore, there is no complete research without literature review.

“Research based on in-depth interviewing is labor intensive” (Seidman, 2013:115). In order to direct an interview to a large group such as the one addressed in the Dissertation, there were multiple steps that took place before the act of surveying the residents. Steps like designing the survey taking in consideration the indicators that can be measured based on resident’s participation and responses; additionally establishing the access to the community to finally be able to do the surveys. These processes were key in the methodology for the Dissertation for it needed to be done so the responses could generalize the results of the project’s population. It is important to note that after interviewing people, the

organization and management of the collected data is crucial, for it will allow the researcher to access the responses in an organized manner keeping track of changes. This process is also time demanding, and that is why the university besides numbering the questions, grouped them in categories so databases of each category will be created, in order to separate the questions and make it easier to tabulate them. But this process presented some inconveniences, when superiors of the research group revised the interviews and the tabulated data, which had errors and made the group seek more people to tabulate in order to meet the deadline. Which proves that, while it covers a larger sample of people, managing their responses is not always airtight. On the other hand, the interviews addressed in Studio A, were held as conversations where their answers were recorded but the questions were directed in a more organic way, with no prior design. This was because of the amount of time that we had for the project. It is different to transcribe 2 hour interviews than 10 minutes, and according to Irving Seidman “…it will normally take from 4 to 6 hours to transcribe a 90-minute tape”. Time is the main reason why surveys and interviews are held in different samples of people. One took more than a year to reach while the other one had to be done in less than a month. While both data sets were extremely helpful to each research work, a larger sample of people will produce more truthful results (Kelley et al., 2003), it has been proven that larger number of people provide better estimates but the resources needed for it are far larger than the interviews that could be done for Studio A.

Lastly the analysis of case studies was used for both works. There is a process to select a case study and one of the parts that are important to consider is how bonded they are to the research, meaning that a case study needs to have connections to our project of research and it can be through time, space and activity (Harrison et al., 2017). Which was done for both Studio A and Dissertation. In Studio A, the case study was visited and analyzed in situ, which provided qualitative information as well because personal experience was part of the research. While in the dissertation, case studies were selected according to their BCI evaluation and certification, and due to time and expenses, it was impossible to visit them and analyze them in person; therefore most of the analysis was done through online databases, which are not always updated and in one of the case studies, it is currently under construction and not finished. This made it particularly difficult to access to users’ perspectives and opinions. This was something that did not happen in Studio A and on the contrary it helped to materialize all the

concepts and knowledge that were acquired during the literature review. This is why it is important to visit the case studies, because they can also shape the approach of the research (Harrison et al., 2017). However, their use for research approaches can be done even without visiting them, as proven in the dissertation, but their value to any type of research gains more insight if they can be accessed in person.

In conclusion, while the scopes and methods were different, similar tools were applied that have proven to be essential in different methodologies. Complementary methods were used, but in both cases, the research was mandated by the opinion and answers of the people that lived in the area of study. Which shows that no matter the research process a project has, the user and resident’s opinion cannot be overlooked, for they live in the site and they know better than anyone the issues that they have.

AMIN, A. & THRIFT, N. 2002. Cities: Reimagining the Urban, Cambridge, United Kingdom, Polity Press.

BOND, A., MORRISON-SAUNDERS, A. & POPE, J. 2012. Sustainability assessment: the state of the art. Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal, 30, 53-62.

BRE GLOBAL LIMITED 2012. BREEAM Communities International: Technical Standard. Watford, United Kingdom.

CRESWELL, J. 2014. Research Design. Qualitative, quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, SAGE.

HARRISON, H., BIRKS, M., FRANKLIN, R. & MILLS, J. 2017. Case Study Research: Foundations and Methodological Orientations. Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 18.

HOLDING, S. 2017. Sharjah Investment Rationale. In: HOLDING, S. (ed.). https://www.alzahia.ae/en/discover/ invest.

JÁCOME, E. 2017. Expropiaciones inclonclusas durante 28 años. El Comercio.

KELLEY, K., CLARK, B., BROWN, V. & SITZIA, J. 2003. Good practice in the conduct and reporting of survey research. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 15.

PÉREZ, A. 2019. El verdadero costo de las Escuelas del Milenio [Online]. Available: https://www.connectas. org/especiales/escuelas-del-milenio/ [Accessed January 7th, 2020].

ROSSI, A. 1982. The Architecture of the City, Chicago, Illinois, The Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies.

STEVENS, Q. 2003. Book Reviews. Cities: Reimagining the Urban. Urban Policy and Research, 21, 217-222.

SEIDMAN, I. 2013. Interviewing as Qualitative Research: A guide of Researchers in Education & The Social Sciences.

TURABIAN, K. 2007. A Manual for Writers of Research Papers, Theses, and Dissertations.

No portion of the work referred to in the thesis project has been submitted in support of an application for another degree or qualification of this or any other University or other institute of learning.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without permission of the copyright holder, the author.

Copyright © 2020 Manchester, England, United Kingdom.

All right reserved.

Manchester School of Architecture

Manchester Metropolitan University University of Manchester

Copyright reserved by Andrea Estefanía Calle Bustamante

MA Architecture + Urbanism

MMU ID: 19005358

UoM ID: 10611399