470 BC | 8.26 CM WIDE RED FIGURE POTTERY

Provenance

Early 20th century collection

Subsequently, in the collection of Myra Karp (b. 1939), Seattle, Washington, acquired 1980s

Displaying the heights achieved by the most talented painters of the Classical Period, this precious fragment from the interior of a kylix (wine cup), depicts a nude athlete preparing for competition by tying a kynodesmē, a thin leather cord used to maintain male modesty. The fragment embodies the aesthetic values and cultural ideals placed on athletics in Greek society. The confident brushstrokes and raised details reveal the skilled hand of the Pistoxenos Painter, celebrated for his refined portrayal of the human form and mastery of intricate detail.

£28,000

2 ND MILLENNIUM BC | 29.8 CM WIDE COPPER

Provenance

The Guennol Collection, acquired prior to 1969, and thence by descent

Published

The Guennol Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Alastair B. Martin, New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1969, no.109, p.12

A. Poster, The Guennol Collection, Vol. II, New York, 1975, pp 55-58

D. Fane & A. Poster, The Guennol Collection: Cabinet of Wonders, Exhibition Catalogue, Brooklyn Museum, 2000, p. 93

Exhibited

‘The Guennol Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Alastair B. Martin’, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1969, no.109 Brooklyn Museum, New York, 1970-2024

An abstract ritual object from one of the earliest South Asian civilisations. Objects of this type are seldom, if ever, seen on the market with a good provenance. This piece was exhibited and published as a highlight of one of the greatest private collections of ancient art ever assembled.

This captivating abstract figure represents a stylised human with gracefully curved, outstretched arms, and is a notable example of Indian Bronze Age ritual art. This dynamic sculpture reflects the advanced metallurgical skills of the late Harappan civilisation and is thought to have played a significant role in ancient ceremonial practices.

These figures have been found primarily in the Ganga-Yamuna Doab region of North India, particularly in Uttar Pradesh, often discovered in riverbeds or marshes, suggesting ritualistic deposition. Anthropomorphic copper figures like this one - part of what is known as the Copper Hoard Culture - date back to the late Harappan period (around 1500-1200 BC). These artifacts are usually flat and vary in size, typically between 25 to 40 cm in length and weighing around 2 kg. They often feature a semi-circular heads, curled arms, a short torso, and extended, splayed legs.

Scholars have long debated the purpose of these anthropomorphs. Some, like P. K. Agrawala in Early Indian Bronzes (1977), suggest they might have served as early religious symbols, possibly precursors to the shrivatsa symbol, seen on the chest of the Hindu god Vishnu. Tapan Kumar Das Gupta, in Der Vajra: Eine Vedische Waffe (1975), posits that they could be early forms of the vajra symbol, a ritual thunderbolt.

These figures, often found alongside other copper objects such as harpoons, antenna swords, and bar celts, suggest a society with advanced copper-working skills and a complex ritualistic culture.

The Guennol Collection is one of the most celebrated private collections of ancient art ever assembled. Meticulously curated over several decades by Alastair Bradley Martin and his wife, Edith Martin, the collection embodies their mission to preserve cultural treasures of remarkable historical and aesthetic significance.

The Guennol Anthropomorph was exhibited alongside other key pieces in the collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art from November 1969 to January 1970, where it was described as ‘one of the most dynamic yet enigmatic objects in the collection’. It was subsequently placed on display in the Indian Galleries of the Brooklyn Museum, where it remained for over fifty years, until earlier this year. Today the Guennol Collection is synonymous with exceptional works of art, including the most valuable ancient sculpture ever sold - the Guennol Lioness.

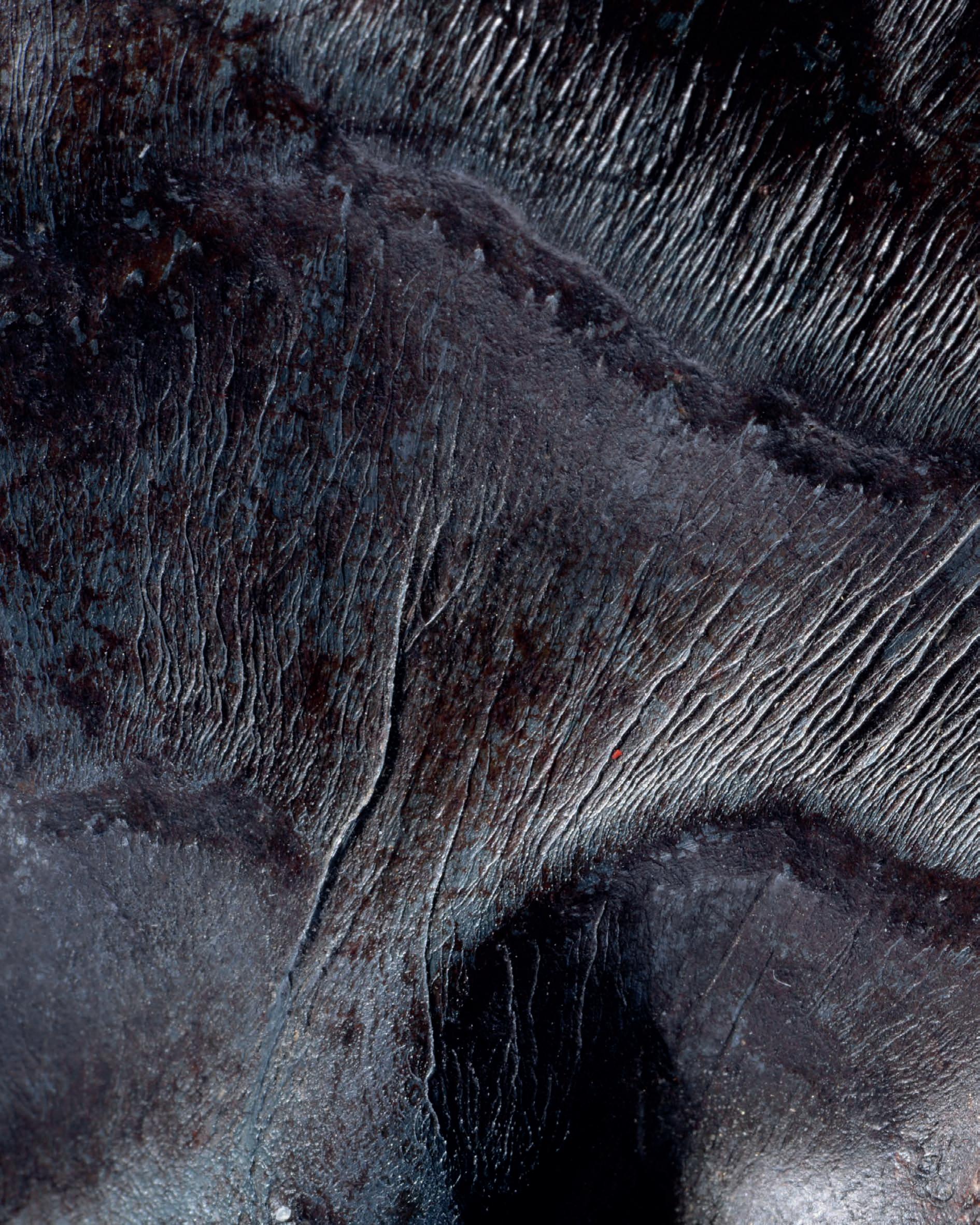

Top The Indian Galleries of the Brooklyn Museum. The Guennol Anthropomorph can be seen at the top of the far right cabinet.

Bottom Title page of the catalogue for the exhibition of the collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 6 November 1969 - 4 January 1970.

Provenance

From the collection of Comte René d’Auxais (1877-1928), Normandy, France

Subsequently by descent to his niece, Antoinette de Bertier de Sauvigny (19061999), Île du Levant, France

Subsequently by descent to Caroline Sénécal, Caen, France

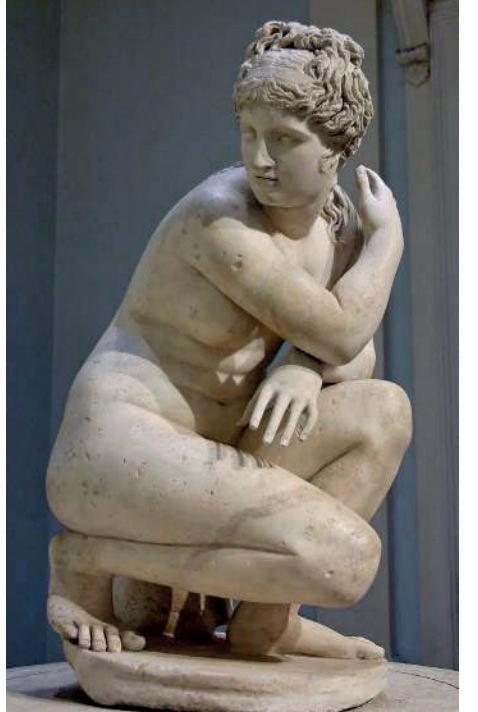

This life-sized sculpture is sensuously modelled, with remarkable attention to detail and naturalism. Preserving the nude, lower torso of the goddess of love, the softly curved stomach, rounded hips, back dimples, and full buttocks are confidently carved and enhanced by a fine polish. Venus stands with her weight on her left leg, with the right leg slightly raised in a graceful pose. A small patch of fragmented stone on the pubis suggests the placement of the now-lost right hand, likely positioned to gently cover the deity’s modesty.

£175,000

‘From the white-crested waves rose Aphrodite, her form radiant and perfect. With one hand she modestly covered her breast, and with the other, she shielded her lower body. The water glistened on her skin as she stepped onto the shore.’

Pseudo-Apollodorus, Bibliotheca, Book 1, Chapter 4

2100 - 1850 BC 23 CM HIGH | POTTERY

Provenance

Collection de Mme S.; Objets de Haute Curiosité et d’Archéologie, Hôtel Drouot, Paris, 2 June 1967, Lot 99

Collection of Jacques and Françoise Martinet, acquired at the above sale

Thence by descent

An exceptional example of a plank figure, the iconic form of human representation from Bronze Age Cyprus. Characterised by its flat, rectangular body and elongated neck, the intricate, incised decoration still retains traces of lime-filled inlay. Artists of prehistoric Cyprus mastered the abstraction of human form, distilling it into this minimalist, geometric style, which was used predominantly in ritual and funerary contexts. This figure is notable for its extraordinary preservation, a rarity given the fragility of its low-fired ceramic medium, together with its well-documented provenance.

£120,000

4.5B YEARS BEFORE PRESENT 6.3 CM DIAMETER, 1.05 KG IRON - IIE

Provenance

Discovered in Xinjang Province, China

This extraterrestrial iron sphere is from the Aletai meteorite, first discovered in northern China in the 1920s. The iron here was originally shattered from the core of a large, differentiated asteroid before being hurled into an Earth-crossing orbit and experiencing a fiery descent at an unknown date in prehistory. The Aletai meteorite is renowned for displaying some of the most striking Widmanstätten patterns - intricate crystalline structures that form only in the vacuum of space, over millions of years.

£9,500 EACH

3 RD CENTURY BC - 1 ST CENTURY AD 30.5 CM HIGH ALABASTER

Provenance

Probably from Haid bin Aqil, the necropolis of ancient Timna Collection of Antonin (Tony) Besse (1927-2016) and Christiane Besse (1928-2021), acquired in Yemen in the 1960s and legally exported

Subsequently, Fine Antiquities, Christie’s, London, 16 December 1982, Lot 112

Subsequently, Ancient Sculpture and Works of Art, Part I, Sotheby’s, London, 7 December 2021, Lot 6

Published

Yémen, au pays de la reine de Saba, Exhibition Catalogue, Institut du Monde Arabe, 25.10.1997-28.02.1998, Paris: Flammarion, 1997, p.100

S. Antonini, Repertorio Iconographico Sudarabico I, Paris, 2001, C.111, p. 112, pl.64 inter alia

Exhibited

‘Yémen, au pays de la reine de Saba’,Institut du Monde Arabe, 25 October 199728 February 1998

‘Jemen: Kunst und Archäologie im Land der Königin von Saba’, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Wien, 9 November 1998-21 February 1999 inter alia

An alabaster female figure, displaying the stylised and elegant forms unique to South Arabian art. The figure is standing with extended arms and clenched fists, the sensitively carved and highly polished face exudes power and mystery, with large, almond-shaped eyes, sweeping eyebrows, straight nose, and gently smiling lips. What separates this figure from many, is its exceptional condition and provenance.

£95,000

65M YEARS BEFORE PRESENT | 27.4 CM HIGH | FOSSIL

Provenance

Lance Formation, Marchant Ranch Quarry, Niobrara County, Wyoming

Collected under lease from the above locality by Western Paleo of Salt Lake City in 1992

A stunning fossil matrix, with large Tyrannosaurus rex tooth surrounded by the jumbled remains of two herbivorous dinosaurs, Edmontosaurus and Ankylosaurus, as well as several other terrestrial and acquatic creatures. An aesthetic presentation preserving a cross-section of life immediately preceding the extinction event that killed the dinosaurs.

£95,000

Found in the Lance Formation in the western USA, this fossil matrix gives an incredible insight into the creatures that roamed the Earth at the end of the Late Cretaceous period. Most prominently displayed is the tooth of a near adult sized Tyrannosaurus rex, with its immaculately preserved serrated edges. This tooth would have come from the back half of the T.rex jaw - a jaw which, at the height of adulthood, would have held over 60 such saw-edged teeth and was easily capable of crushing bone. The matrix has also captured the teeth and numerous parts of ossified tendons from one or possibly several hadrosaurs (duck-billed dinosaurs), most likely Edmontosaurus. A large piece of bone at the base of the block is likely the scapula, or shoulder blade of an Edmontosaurus. On the reverse, there is a worn tooth from an ankylosaur (the armoured dinosaur), probably belonging to an Ankylosaurus

Beyond the dinosaurs, other animals are also present. In the centre of the block, there is part of the left jaw of a small mammal bearing a molar, as well as multiple fragments of terrapin plastron (the bottomside of the shell that lies beneath the abdomen). One has a stippled surface, displaying the outside texture of the plastron, whereas another is turned over so the smooth side is visible. The matrix also bears a single, small crocodile tooth, as well as several enamelcovered scales from garfish and other aquatic creatures.

These fossilised specimens are held together by a mixture of sand, mud, and pebbles which is likely the result of a fluvial process, as is the case for almost all dinosaur fossils from the Hell Creek and Lance Formations. These creatures most likely died on a floodplain, where flood waters later washed them downstream into a high energy environment, before they settled and were buried. This resulted in the preservation of land animals alongside freshwater creatures. Providing a rich and varied summary of life 65 million years ago, this matrix displays the remnants of at least three dinosaurs, a mammal, a turtle, a crocodile, and multiple fish.

A remarkable artefact offering an incredible insight into life at the end of the reign of the dinosaurs.

490-470 BC | 10.5 CM HIGH | BRONZE

Provenance

Kunstwerke der Antike. Auktion XXII, Münzen und Medaillen, Basel, 13 May 1961, Lot 72

Subsequently in the collection of Leo Biaggi de Blasys (1906-1979), Lugano

Thence by descent

A precious example of Archaic Etruscan sculpture, depicting one of the most iconic athletes of the ancient world, the discus thrower. Described with admiration by esteemed scholar-dealer Herbert Cahn in 1961, ‘The figure is a masterpiece and illustrates with rare vividness the essence of good Etruscan sculpture...’

£125,000

750-600 BC 68.5 CM HIGH POTTERY

Provenance

Egyptian, Greek, Roman and Cypriot Antiquities, Sotheby’s, London, 11 - 12 November 1926, lot 23, bought by ‘Zachariades’

Subsequently in the collection of Edward Varley Kayley (1900 - 1974)

Thence by descent

This large, exceptionally well preserved bichrome amphora reflects the artistry and originality of the finest Cypro-Archaic pottery. It is richly decorated with bands of intricate geometric motifs and striking lotus patterns, each meticulously painted in vivid colours. The lotus flower, a recurring motif in early Cypriot art, likely held significant chthonic symbolism, representing concepts of life, death, and rebirth.

£50,000

2 ND CENTURY 33.5 CM HIGH | MARBLE

Provenance

19th century European private collection [according to old plaster restorations]

Subsequently with Royal Athena galleries [according to remains of an old sticker on the reverse of the previous base]

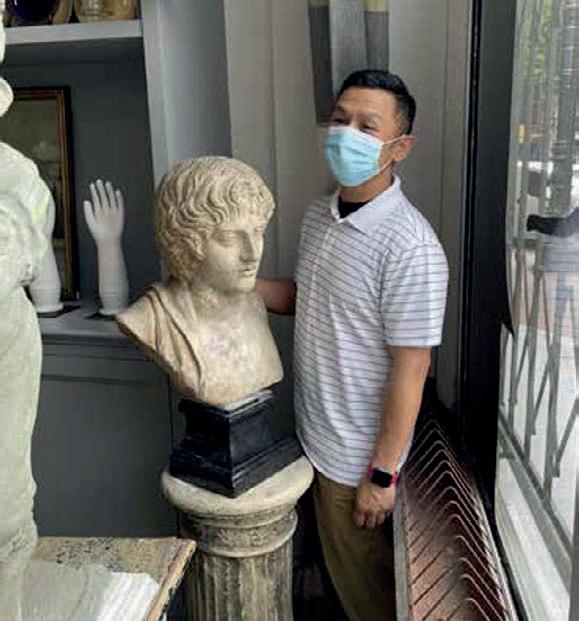

Subsequently, San Francisco art market 2023

An exceptionally fine style marble head of Apollo, the most beauitful of all the Olympian dieties. Once miscatalogued as a 19th-century portrait bust, the present piece was recently rediscovered and its nineteenth century restorations removed to reveal an extraordinary, early Christian carving at the top of the head.

£300,000

The present sculpture, with its elegant features and exceptional style, is a Roman work, likely depicting Apollo. The smoothly carved features perfectly display the ideal of youthful male physical perfection, in contrast with depictions of Zeus or Poseidon, who are typically portrayed older and rugged. The voluminous hair was likely built up further atop the head, consistent with similar depictions of the god of sun, music, prophecy and healing. The back of the head appears roughly shaped, indicating that it would have been made for display in a niche within a temple or shrine. A line indented into the hair was intended to hold a metal diadem or wreath, signifying Apollo’s divine status.

Perhaps once forming part of a public statue, seen and worshipped by thousands, by 2023, this head of Apollo sat in the window of an interior design store in San Francisco, covered in restorations and thought to be a nineteenth century sculpture. Only on removing this restoration, and revealing the original surface and encrustations beneath, was it reidentified as a Roman Apollo.

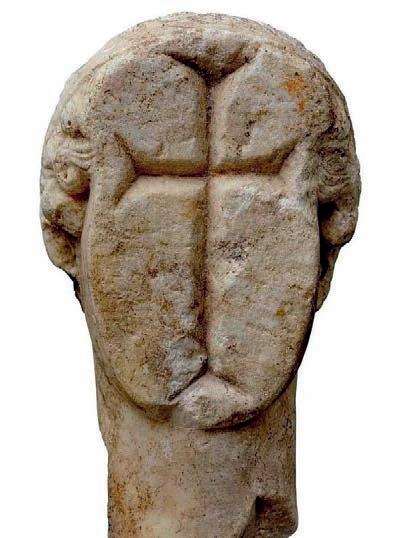

Moreover, on paring back the plaster, a curious break and deep cross carved atop the head was uncovered. Modified for religious reasons by later Christians, the present example is one of a small number of sculptures of this type known to exist. With the rise of Christianity throughout the 5th to 10th centuries AD, such pagan statues were often marked with a representation of the Holy Cross, sometimes drawn equilaterally and ornately carved.

Buried for centuries, it was then likely discovered in the early 18th century and brought to the art market. At that time, the neoclassical movement standardised restoration and modification of ancient sculptures to suit changing fashions. Missing fragments were replaced, and sculptures often ‘improved’ by adding new elements that were not part of the original work. Remnants of a rusted iron pin atop the present head and the original thick, overpainting of plaster, reveals a common restoration technique carried out during this period. With its losses covered, it was later slotted into a separately made bust.

Only by removing the additions of time do we see a breathtaking, if fragmented, ancient sculpture, its scars indicative of the periods through which it has lived. Recognised again as Apollo, it can be understood as a powerful example of the fusion of Greek and Roman cultural and artistic identities.

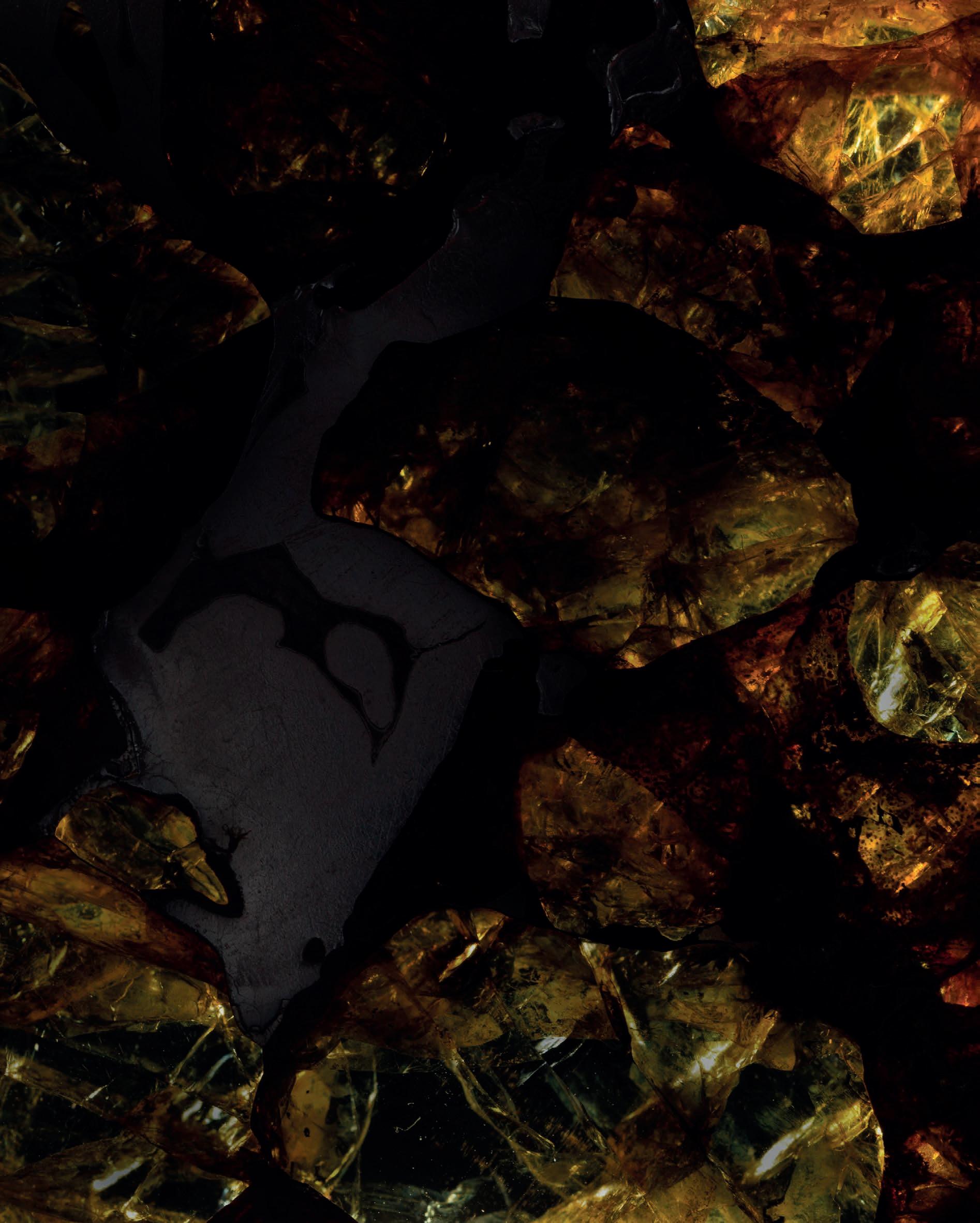

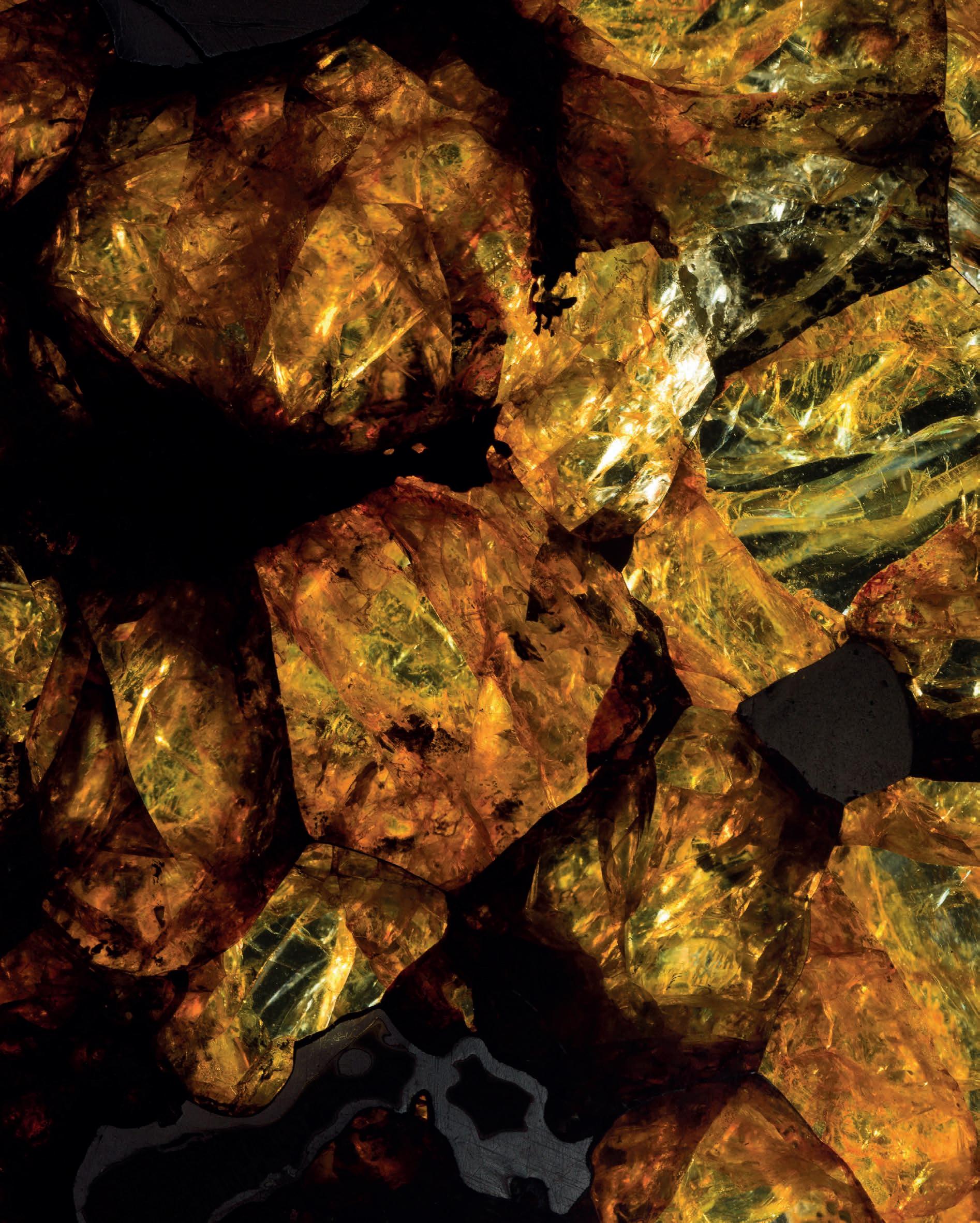

4.5B YEARS BEFORE PRESENT 20.95 CM HIGH, 282 G | PALLASITE

Provenance

Discovered in 1822 in the Atacama Desert, Chile

This complete cross-sectional slice from the Imilac meteorite has been prepared to reveal shimmering olivine and peridot gems embedded in an ironnickel matrix. The magnificent honeycomb pattern shown here is characteristic of pallasite meteorites, of which Imilac is one of the finest. It was found in 1822 in the Atacama Desert – the most arid place on Earth – and is one of the most highly coveted pallasites thanks to its particularly high concentration of translucent olivine.

£30,000

‘This 282 g interior section of Imilac shows a large range of olivine surrounded by a matrix of ironnickel derived from the molten core of a differentiated asteroid.’

Dr Alan E. Rubin, PhD, Department of Earth, Planetary, and Space Sciences, UCLA

2700-475 BC 17.9 CM HIGH ANIMAL BONE

Provenance

Collection of Desmond Morris, acquired prior to 1985

The Art of Ancient Cyprus, The Desmond Morris Collection, Christie’s London, 6 November 2001, Lot 13

Dutch private collection, acquired from Rupert Wace Ancient Art, June 2005

Published

D. Morris, The Art of Ancient Cyprus, Oxford: Phaidon Press, 1985, p.165, pl.190b Eternal Woman, no. 26, Rupert Wace Ancient Art Ltd, London, 2005

Though only known from a handful of examples, these Cypriot bone idols are amongst the most enigmatic figural artworks produced on the island. Variously dated as Bronze Age or Cypro-Archaic, they are ingenious in their simplicity. The ancient artist utilised the natural contours of the cattle bone, incorporating incisions reminiscent of plank figures, to create a stylised human form. This piece was once part of the renowned Desmond Morris Collection, and is published in his landmark book, The Art of Ancient Cyprus

£25,000

500 BC - 400 AD 1 0 CM DIAMETER SILVER

Provenance

Found in Rathcormac, Co. Cork, Ireland (1882–1883)

Collection of Robert Carfrae (1820–1900)

Thence by descent

Antiquities and African & Oceanic Art, Lyon & Turnbull, Edinburgh, 31 July 2024, Lot 96

One of only five known examples, and quite possibly the finest Celtic silver ribbon torc in existence. This iconic piece of Celtic art is a hypnotic masterpiece of ancient precious metalwork, and once formed part of the esteemed collection of the curator of the Museum of Antiquities of Scotland, Robert Carfrae.

£95,000

Throughout the course of the first millennium BC, a civilisation, emerging from the headwaters of the Rhine, the Rhône and the Danube, erupted in all directions across Europe. Their skilled metallurgical abilities, particularly in making iron weapons, established them as a powerful force to be reckoned with, and in their advance through Europe they left an indelible impression on the renowned empires of the day. While known to us today as a savage and bellicose race on account of surviving Roman and Greek sources, their material culture, and more precisely, their mastery of metalwork, places them among the very be st of ancient craftsmen, whose creations are still celebrated and copied today.

Foremost among Celtic metalwork - and arguably on par with their weaponry - was the torc (or torque). As a key marker of social status, they were widely worn and created in a range of metals, no doubt selected to reflect the wealth of the owner. Their importance is also indicated by their depiction on gods and goddesses of Celtic mythology. Indeed, the cauldron of Gundestrup, found in Denmark in 1891, details the god Cernunnos wearing a torc around his neck, and holding one in his right hand. They similarly appear in Roman sculpture as signifiers of Celtic identity.

The Rathcormac Hoard, County Cork, 1883

In 1883, antiquarian Ralph Westropp presented a ‘twisted silver Torque’, found near Rathcormac, country Cork, to the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland.The torc was found ‘by a peasant, beneath a stone in a field, when ploughing’, with four others ‘of a similar make’, detailing ‘various markings and engravings.’Of the five ribbon torcs described in the 19th century, four are to be found today in museum collections around the world; two are in the collection of the National Museum of Scotland, Edinburgh (acc. nos. X.FD 33 and 34); one in Cork County Museum; and one, reappearing in a 2011 Bonhams auction, was acquired by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (Acc. no. 2013.613). Similarly reappearing earlier this year, 141 years after its discovery, the present torc has been reidentified as the last silver ribbon torc from the 1883 find, and it is the only one remaining in private hands.

The Rathcormac torcs are unique in their design, manufacture, and material; they are the only known silver ribbon torcs in existence. Each piece is crafted from a flat strip of exceptionally pure silver, around 97%, adorned with engraved motifs and carefully shaped into a series of graceful twists. Their uniqueness sugge sts they may have been created for a specific event, ritual, or celebration.

In light of this important rediscovery, the Carfrae torc has been examined by Dr Fraser Hunter, the Principal Curator at the National Museum of Scotland, alongside the two other Rathcormac torcs in the museum’s collection, reuniting them for the first time since 1883. Featherlight, twisted from a long decorated strip and clasped at the ends, the present torc is a remarkable rediscovery, and a very rare example of the talent of the Celtic metalworker.

Top The Carfrae Torc (top) and the two silver ribbon torcs from the Rathcormac Hoard now in the National Museum of Scotland, acc. nos. X.FD 33 (bottom left) and 34 (bottom right). Neil McLean, image © National Museums Scotland.

Bottom The god Cernunnos wearing and holding a torc, on the Cauldron of Gundestrup (200-300 A.D.). Found 1891, Denmark. Now in the National Museum of Denmark, Copenhagen.

2 ND-4 TH CENTURY BC 43 CM DIAMETER PUDDINGSTONE

Provenance

French private collection

Subsequently French art market, April 2023

Exported from France with French Cultural Property Passport 243418

The lower grinding stone from a late Iron Age to early Gallo-Roman quern, a beautiful symbol of daily life from over two millennia ago. An essential tool, the quernstone was used for grinding grain into flour, and this example is carved from puddingstone, a remarkably hard and visually striking sedimentary rock, named for its resemblance to a fruit-filled cake. The stone’s surface is embedded with a mosaic of pebbles in a spectrum of beautiful colours, ranging from soft pinks and deep reds to warm oranges and subtle greys.

£25,000

2 ND - 3 RD CENTURY AD | 19.7 CM HIGH MARBLE

Provenance

Acquired by Henry Howard, 4th Earl of Carlisle, between 1714-1739 during his travels to Rome, and thence by descent Castle Howard, York, Yorkshire, Sotheby’s, 11 November 1991, Lot 44

Published

B. Borg & H. von Hesberg, A. Linfert, Die antiken Skulpturen in Castle Howard, MAR XXI, Wiesbaden, 2005, 69, cat. no. 28, pl. 24 Arachne 3827: Lower part of a statuette of Zeus/Jupiter, Castle Howard, Yorkshire, Western Staircase.

Almost cameo-like in appearance, this fragmentary statuette is rendered in fine-grained white marble, preserving the feet and left leg of Jupiter, god of the sky and King of the Gods, alongside his symbolic eagle and oak tree, representing his divine power and authority over nature. This piece, retaining its original polish, once belonged to Henry Howard, 4th Earl of Carlisle (1694-1758) and was displayed alongside his family’s illustrious collection of antiquities at Castle Howard, North Yorkshire - one of the largest, grandest, and most iconic stately homes in the United Kingdom.

£36,000

945-900 BC | 25 CM HIGH | GESSOED & PAINTED WOOD

Provenance

Collection of Henri Lefort des Ylouses (1882-1978), acquired from ‘Delcourt’ in 1930

Subsequently by descent to Daniel Lefort des Ylouses (1945-2022)

Subsequently by descent to Henri Lefort des Ylouses (born 1977)

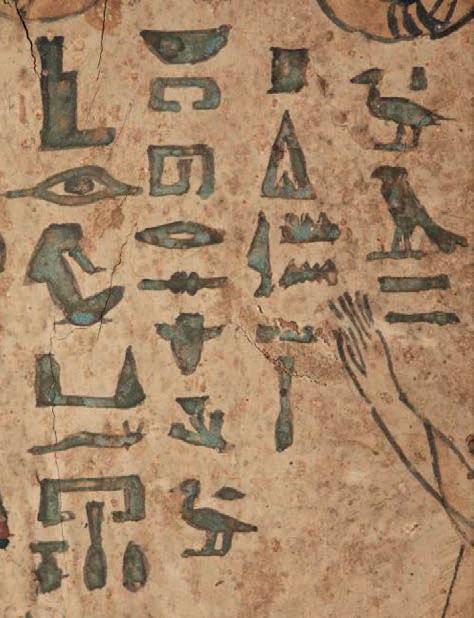

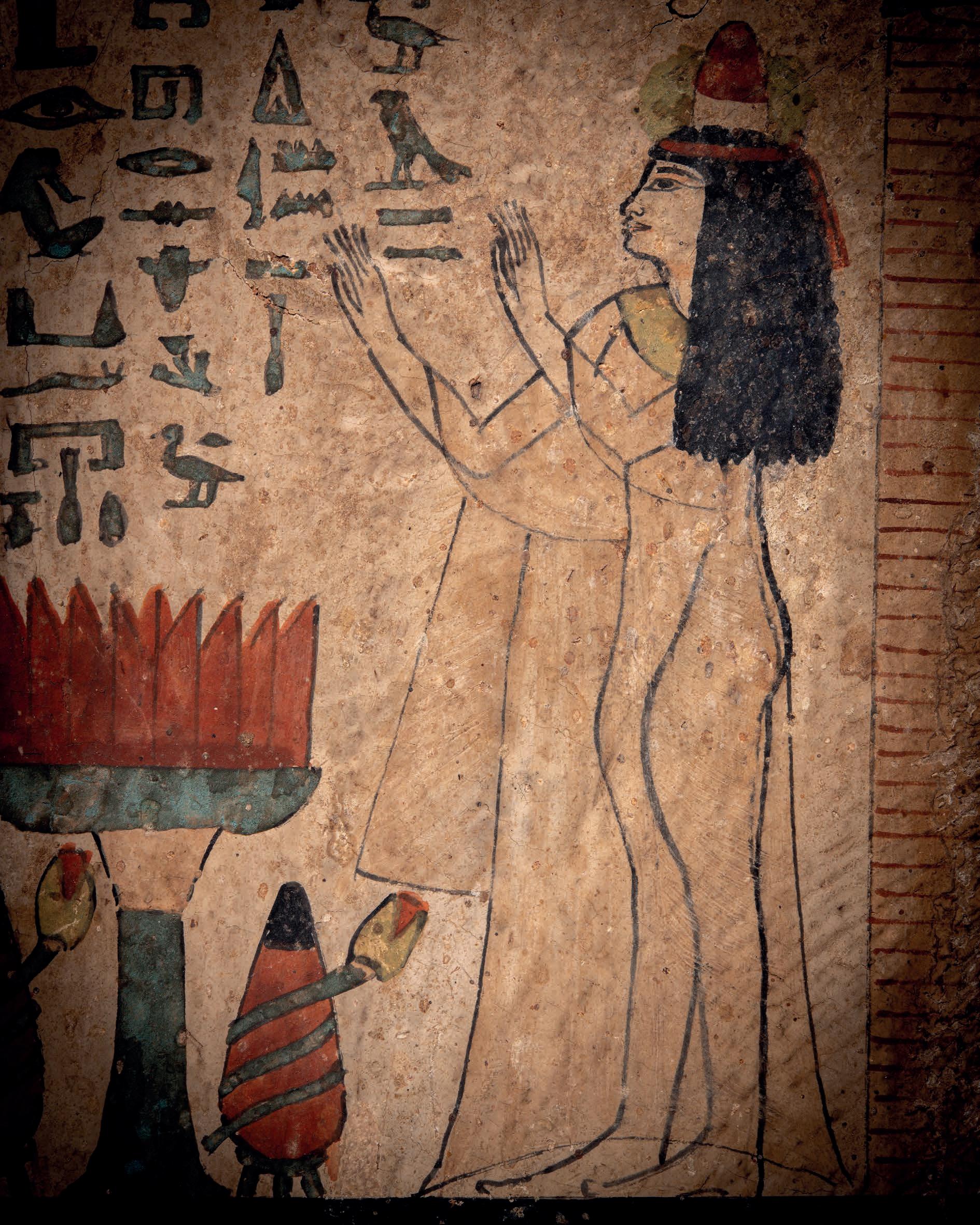

An unusually refined wooden stele dating to the zenith of Egyptian painting during the Third Intermediate Period, remarkably well-preserved with its delicate gesso almost completely intact. The scene depicts Heres, an elite woman from a priestly or noble family, presenting offerings to Osiris, the god of the afterlife. The exceptional quality and preservation of this piece highlight the artistic mastery of the 22nd Dynasty Theban workshops.

£230,000

Heres and her Journey to the Afterlife

A round-topped stele depicting an offering scene, framed by door-leaves, a celestial skyvault and red earth. Adorned in a diaphanous gown, with a perfume cone atop her head, Heres stands with outstretched arms, presenting offerings of wine and bread to the mummiform god Osiris, depicted with a sun-disk. In the lunette lies another sun-disk, accompanied by two uraei, and flanked by offerings of incense and bread. On the table between them, further offerings of bread are depicted, and beneath, two jars of wine wrapped in the twisted stems of lotus flowers. In front of the figure of Osiris, a single line of hieroglyphs reads: ‘Osiris, may he give an invocation offering of bread and beer.’ Facing this, another inscription confirms the name and title of the stela’s owner: ‘The Mistress of the House Heres, daughter of Pa-di-Amun, justified, son of Hor, justified.’

The Third Intermediate Period (c.1070-664 BC) was characterised by profound political and cultural change. Following the political fragmentation of the 21st Dynasty, in 945 BC, Egypt’s throne passed to a powerful family of Libyan descent. Dynasty 22 brought about a reimposition of central authority followed by a period of inevitable cultural transformation, which also extended to burial practices. With elaborate, decorated graves now almost completely abandoned, the deceased were often buried in existing tombs, repurposed for their journey to the underworld. As such, tomb furnishings also underwent significant changes.

While everyday objects were no longer considered important funerary paraphernalia, the two objects which remained crucial to the burial rites were coffins and funerary stelae, which both adopted new significance during this period. Indeed, it was during this period that wooden funerary stelae reached their highpoint. Emerging in the First Dynasty as burial markers, from the Middle Kingdom onwards they became an integral part of burial furnishings, recording the names, titles and representations of the deceased to keep their memory alive. Furthermore, they played a particularly crucial role in the deceased’s journey to the afterlife. Typically showing the stele’s owner before an offering table, piled high with the goods they are presenting to the god opposite, the images and inscriptions served as powerful invocations to the gods, ensuring a safe transition for the departed from the mortal realm to the spiritual one. Stelae also marked the place where the living could come into contact with the dead, offering both physical remembrance and spiritual guidance to the family of the deceased. During their highpoint, the centre of wooden stelae production was in Thebes. Indeed, it is in the Theban necropolis where the majority of such wooden stelae have been found, or have since been attributed to on account of their fine style. In the few cases where the archaeological context has survived, it is suggested that stelae were free-standing objects, placed next to the coffin in the burial chamber.

‘ Osiris, may he give an invocation offering of bread and beer. The Mistress of the House Heres, daughter of Pa-di-Amun, justified,son of Hor, justified.’

Iconography

This stele can be assigned to the Third Intermediate Period, probably Dynasty 22, on account of its unique decorative agenda. It is also particularly notable for its fine craftsmanship, as well as several delicate features which are rarely seen on others of the same period.

On the right, an elite woman, the owner of the stele, is clad in an elaborate, diaphanous dress covered by a sheer mantle. Her clothing’s sole adornment is the green broad collar, symbolic of her rejuvenation in the afterlife, and atop her head she wears a perfume cone, traditionally painted in red and white. The inscription identifies her as ‘The Mistress of the House Heres, daughter of Pa-di-Amun, justified, son of Hor, justified.’ Heres’ name itself means ‘She (i.e. a goddess) is satisfied.’ In keeping with the canon of proportion used in New Kingdom art (c.1570-1069 BC), her shortened torso and elongated legs creates a slender and feminine figure which is further emphasised by the fall and elegance of the diaphanous dress and mantle. Particular care has gone into the depiction of the deceased, exemplified in the delicate addition of makeup, as well as the hatching scratched into the plaster to emphasise the lines of the dress and the sheer fabric. The dating of the piece is further consolidated by her accessories, and in particular the style of the perfume cone - broad at the base, divided in two blocks of colour, and surrounded by green vegetationwhich is again in line with other depictions of the period. This green vegetation is particularly interesting to note, as it has been seen to represent the regeneration of the deceased in the afterlife.

Heres stands, arms outstretched in adoration, opposite the standing figure of the bearded mummiform god, Osiris. The very depiction of Osiris confirms the dating of the stele to early in the Third Intermediate Period (probably Dynasty 22) as, by the 9th century BC, the deity was completely replaced by standing or seated figures of Re-Horakhty. However, it is his depiction here that is particularly unusual. Osiris is more traditionally depicted wearing the Atef crown, the white headdress of Upper Egypt, along with the symbols of his kingship and authority in the underworld, the crook and flail. Yet on the present stele, the figure of Osiris, while holding his crook and flail, is adorned with a sun-disk and uraeus above his head. This is a specific reference to Re, the sun god, under whose control Osiris exercised his power in the underworld. Indeed, in the New Kingdom and its aftermath, Re was believed to be in charge of both the sky and the underworld, while Osiris only had power over the latter. The authority of the sun god is further emphasised by the central dominance of the sun-disk with flanking uraei in the lunette of the stele. That the complementary relationship between the two gods is depicted here is unusual, and is evidence of the complex and interchangeable nature of Egyptian symbolism. Indeed, in addition to these invocations of the sun god, the flesh of Osiris is painted a light green, reflecting his own identity as a god of vegetation and regeneration, and again emphasising the spiritual significance of the stele in ancient Egyptian funerary rites.

Bread and Beer

Standing between Heres and Osiris is an offering table, painted in blue and white, on top of which are offering loaves. Either side of the offering table, sealed jars of wine sit on low stands, and are embellished with lotus flowers symbolic of rebirth, twisted around the body of the vessel. This scene is mirrored by a single line of hieroglyphs in front of the figure of the deity, which reads: ‘Osiris, may he give an invocation offering of bread and beer.’

With funerary wishes for beer and bread common to the burial rite, the specific depiction of other offerings was up to the discretion of the artist. Indeed, in the lunette, and to either side of the dominant sun-disk, are the unusual offerings of incense pots. This iconographic feature first occurs in the lunettes of stelae during the Middle Kingdom, where, in some examples, the incense pots are held by outstretched human arms, mirroring the hieroglyph for henqet, meaning ‘offering(s).’ That these incense pots are meant as further offerings is confirmed by the presence of the bread-loaf hieroglyph, used for the letter t, below each incense pot, serving as feminine phonetic complement for the term for offerings.

This scene of Heres and Osiris is carefully framed to heighten its symbolism, as well as to produce a carefully balanced and visually pleasing composition. Indeed, to the left and right of the scene, door-leaves, painted in beige with fine red lines, symbolise the doors of Heaven. Their inclusion in the decorative agenda of stelae has been identified as a particularly rare one, and dated to the 7th century BC, although earlier examples have been found. Moreover, at their base, a simple band of red and black at the base represents the earth, while at the top, they hold up an overarching band of dark blue representing the vault of the sky. Highlighting the cosmographical setting of the main scene, this clever framing is perhaps also carefully constructed to reflect the journey from the mortal realm to the afterlife that the deceased must now undertake.

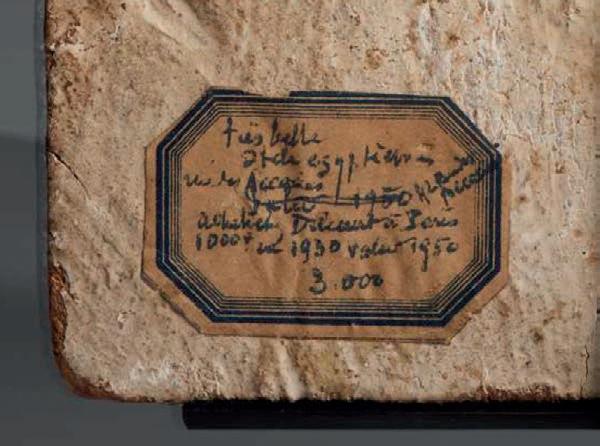

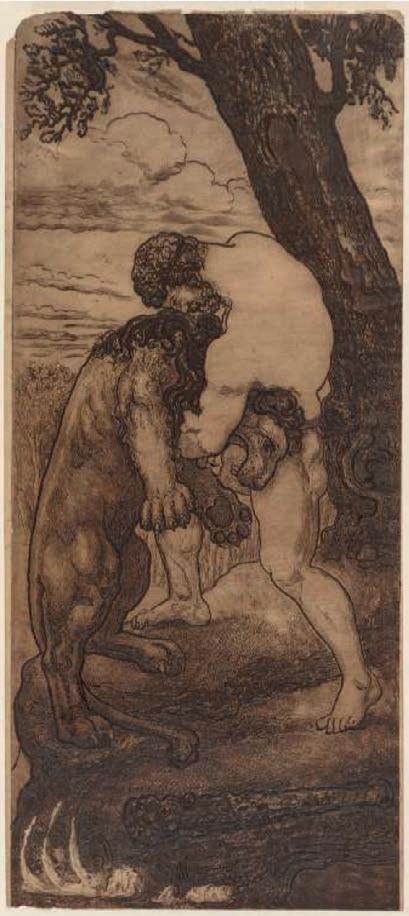

Henri Lefort des Ylouses (1882-1978)

Born in 1882 into an artistic family, Henri Lefort des Ylouses was a Lieutenant in the 85th Infantry Regiment. He was a graduate of the Special Military School of St-Cyr, the most prestigious French military academy, set up in 1802 by Napoleon to train officers and generals. His interest in art was probably conditioned by his father, Arthur Henri Lefort des Ylouses (1846-1912), who was a painter, engraver, ceramist and sculptor. Receiving classical training at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris, under the tutelage of painter Alexander Cabanel, he regularly exhibited in the Salon de Paris’ ceramic section, and his work was rewarded with a silver medal at the Universal Exhibition of 1878. Henri Lefort des Ylouses bought the present piece in Paris in 1930 from ‘Delcourt’, accordingto the inscription.

Top Label on the reverse of the stele detailing the purchase from ‘Delcourt’ in 1930.

Bottom Henri Lefort des Ylouses, Hercules and the Nemean Lion, c.1898. Gypsograph, The Cleveland Museum of Art, 2009.526.

530 BC | 29 CM WIDE BLACK-FIGURE POTTERY

Provenance

English private collection, acquired prior to 1974

A Fine Collection of Classical Antiquities, Part I, Christie’s, London, 10 July 1974, Lot 106 (pl.31), bought by ‘Seegers’

English private collection, acquired at the above sale

Subsequently by descent

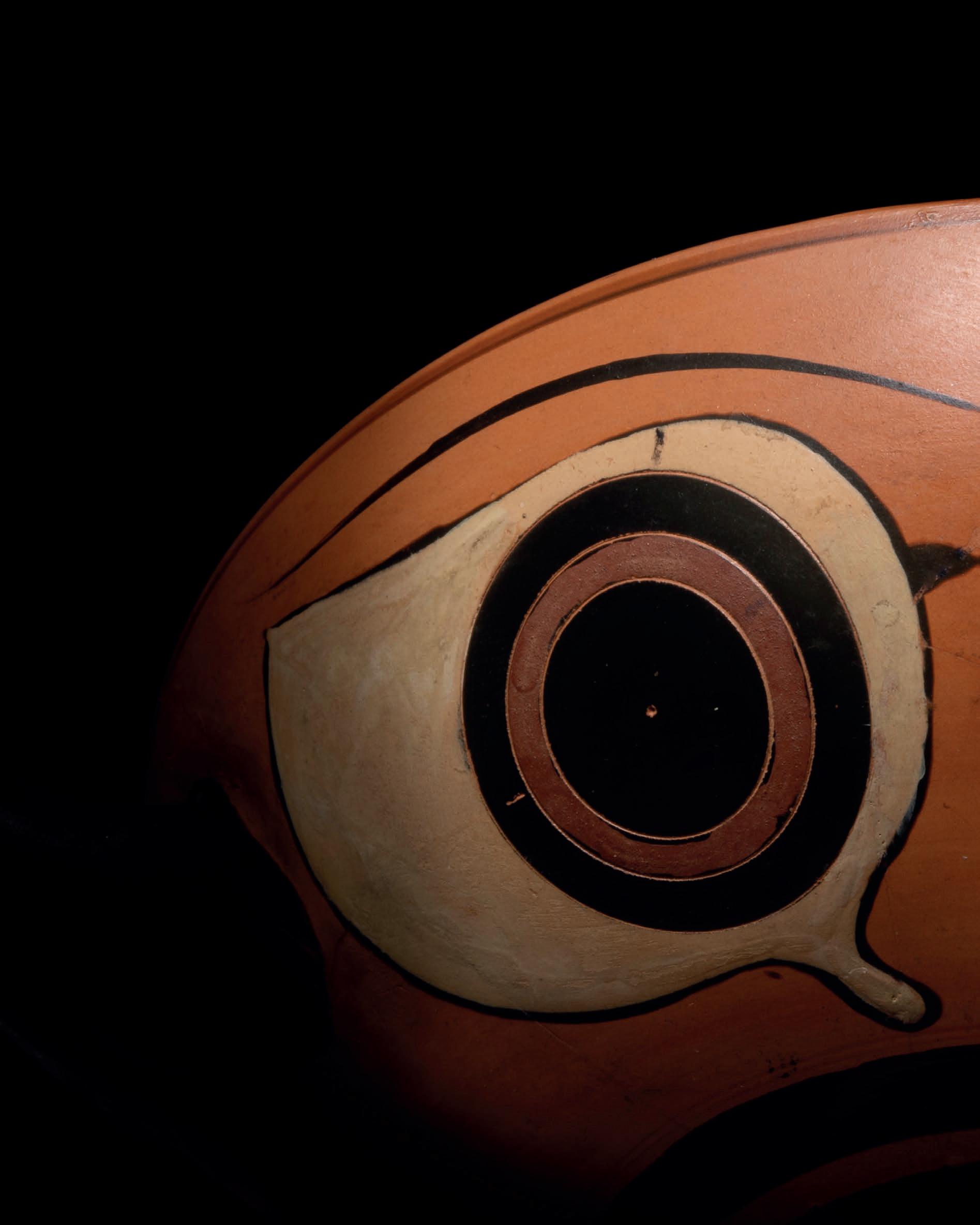

A rare, erotic cup exemplifying the revelry and humour of ancient Greek culture, particularly within the context of symposia - the social drinking parties of the elite. This wine cup features two large eyes on the exterior, which, when tilted up to drink, humorously superimpose themselves onto the drinker’s face. At the same time, the act of drinking reveals the cup’s indecent imagery, perhaps adding an element of playful surprise.

£35,000

50M YEARS BEFORE PRESENT 1 M HIGH | FOSSIL

Provenance

Discovered by Liz Lindgren on Lewis Ranch, in the Green River Formation, Wyoming, 3 August 2021

Exhibited

The counterpart to the present fossil is now exhibited at Fossil Butte National Monument Museum

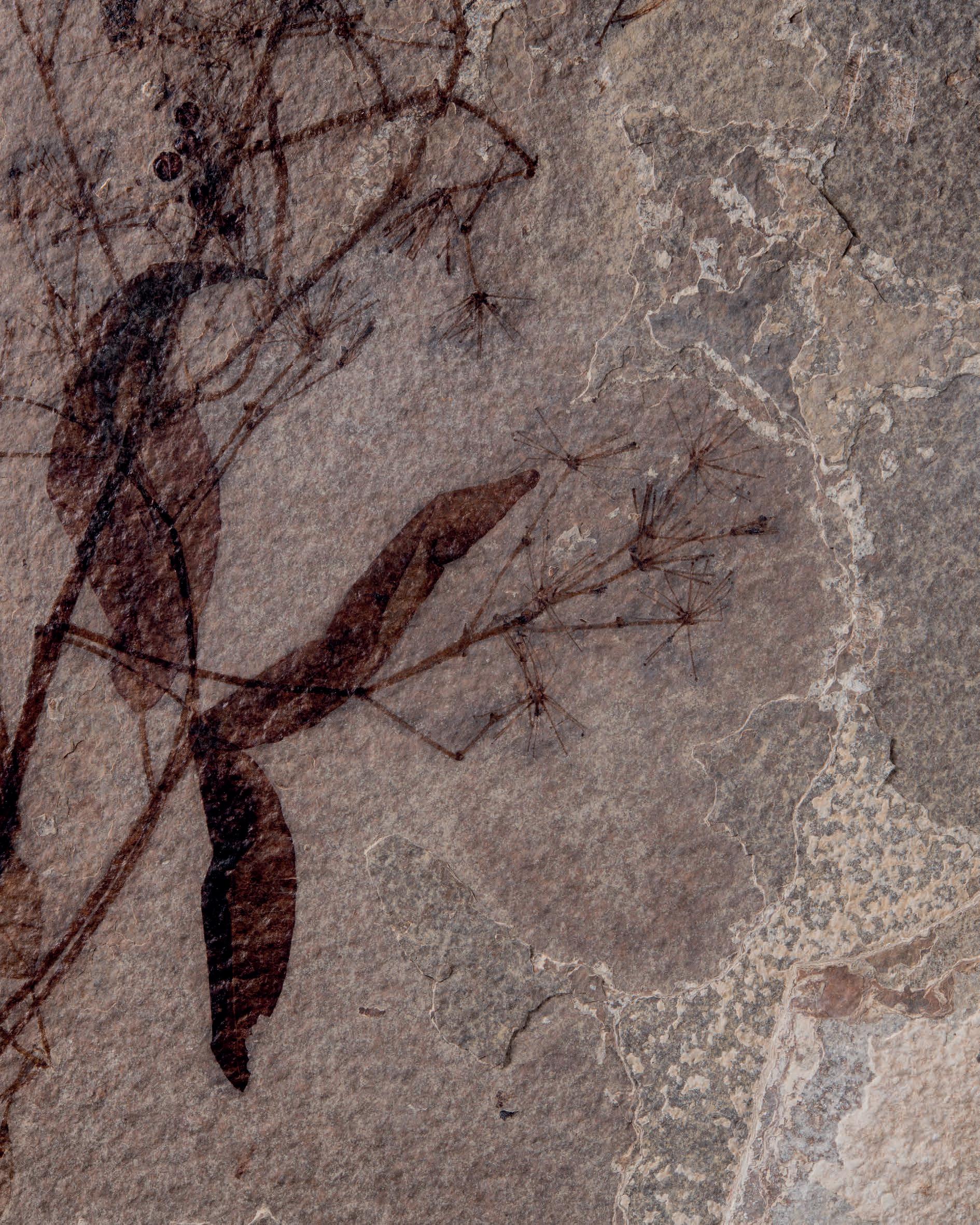

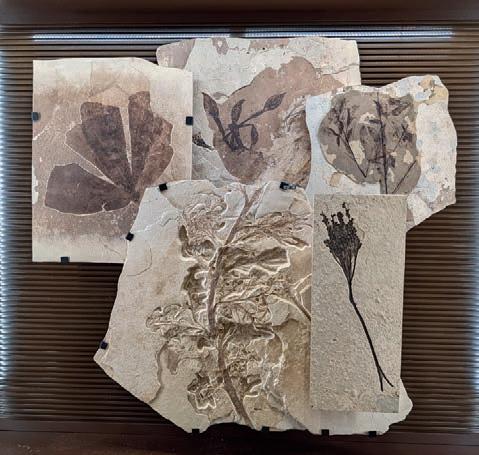

A breathtaking botanical fossil, this piece from the renowned Green River Formation is not only of immense scientific value but also of unparalelled aesthetics. Delicately preserved, the intricate arrangement of leaves and small berries evoke a still life, with each fragile structure rendered in astonishing detail. With its life-like quality, this fossil feels as though it captures a fleeting moment - a glimpse into the natural beauty of the prehistoric world.

Today, the Fossil Basin in southwestern Wyoming, US, is a harsh, mountain desert environment. But 50 million years ago, during the early Eocene, it was a subtropical lake bursting with life and lush vegetation. Arguably the world’s most famous Lagerstätten, or fossil treasure troves, are found here, due to the miraculous circumstances of sedimentation and deposition that has resulted in some of the most remarkable fossils ever found. At its height, the Green River Lake System comprised three lakes - Lake Uinta, Lake Gosiute and Fossil Lake - and is thought to have lasted a phenomenal 12 million years. From the earliest mammals, to the distant ancestors of today’s plant life, buried deep within the limestone deposits of Wyoming’s Fossil Basin, it is a remarkable picture of an ancient ecosystem, and the beginning of life as we know it today.

As noted by Dr Lance Grande, the world’s leading expert on the Fossil Butte Member, extant plant fossils from this locality include a variety of well preserved leaves, pollen grains, flowers, fruits and branches. Unfortunately, ‘these parts are rarely, if ever, found attached to each other,’ hindering scientific analysis. The present fossil however, displays, in perfect and unparalleled detail, the delicate leaves, berries and sprouting formations of this plant, all still attached to the stem. As a remarkable example of one of the most well-preserved prehistoric ecosystems, it displays a beautiful snapshot of life that blossomed after the reign of the dinosaurs.

The present branch has been identified as a member of the Araliaceae family. Made up of flowering, primarily woody plants, the family is sometimes known today as the ‘ginseng family’, on account of its famous species, Panax ginseng. Today, it is commonly found in Southeast Asia and tropical America, but 50 million years ago, the subtropical climate of the Green River Formation provided the perfect environment for its germination. Accompanying this warm climate was the growth of a herbivorous insect population. Evidence of this early insect-plant relationship is preserved in remarkable detail on the present fossil. The successive, scalloped incisions on one of the top leaves’ edge are consistent with damage caused by leafcutter ants. Moreover, at the base of the stem, there is also a partial fossil of a fish, reflecting the abundance and distribution of fish species among the freshwater localities of Fossil Lake. Preserving the tail on the left and head on the right, this has been identified as an early fresh water herring, called Diplomystus dentatus.

The present piece was discovered by fossil hunter Liz Lindgren on Lewis Ranch in the Fossil Butte Member of the Green River Formation on 3 August 2021. Its less complete counterpart now resides in the collection of the Fossil Butte Monument, as a key example of specimens collected from this locality. Over the last forty years, Lewis Ranch has produced some of the most remarkable fossils, including an example of the famous ‘dawn horse’, or Eohippus, discovered by Jim E. Tynsky in 2003.

Of all those to be recovered from the Fossil Butte Member, the present fossil is a particularly remarkable and well-preserved example. Reflective of a world undergoing a process of regeneration and renewal, the present fossil provides an incredible snapshot of prehistoric life, and the rarest example of a plant from the world-famous Green River Formation.

1 ST CENTURY AD | 22 CM HIGH | GIALLO ANTICO & MARBLE

Provenance

19th century European collection [based on restoration techniques and nero portoro socle]

US Private Collection, Texas

Subsequently, Antiquities, Sotheby’s, New York, 12 June 1993, Lot 149

Subsequently, Antiquities, Christie’s, New York, 26 January 2023, Lot 92

Published

Peña, A. and Ojeda, D. ‘Miniature Herms Representing Alexander the Great’, Hesperia, Vol. 89, No. 1, (2020): p. 105, n. 137.

One of the finest extant examples of a beautiful sculptural type, which shows Alexander the Great in rare, coloured stone. Fashioned during the Roman period, it is testament to Alexander’s enduring legacy. Carved in the finest style from giallo antico and carefully polished, the king dons Hellenistic scale armour and an Attic helmet.

£135,000

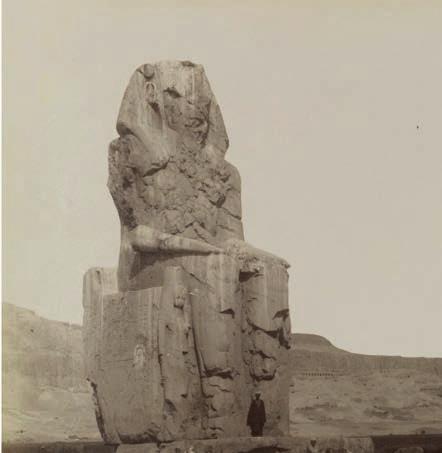

379-360 BC 1.05 M LONG LIMESTONE

Provenance

Recovered from the Serapeum of Memphis, c.1830-1860

Subsequently, English private collection, 19th century [see documentation from auctioneer and surface analysis by Prof. Richard Armstrong]

Subsequently in the collection of South-African born interior designer, Dudley Polpak

Offered for sale by Cheffins Auctioneers, Cambridge, c.2004

Subsequently with Mander Auctions, 25 October 2021, Lot 345 [mis-catalogued as 19th century stone garden models]

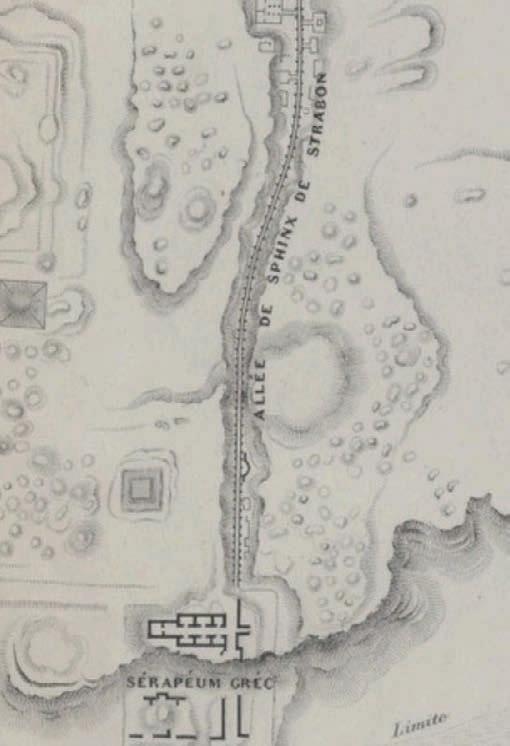

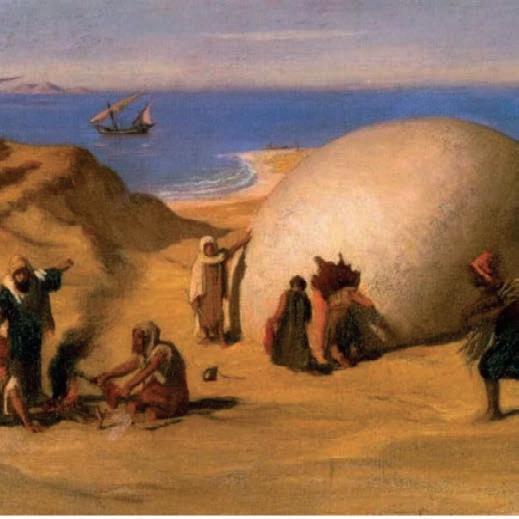

The sphinxes of the Serapeum have captivated travellers since Roman times. However, despite their significance, they remain conspicuously absent from the collections of most major museums. Indeed, their existence in private hands is so improbable, and their imitations so numerous, that the present sphinxes were assumed to be modern copies throughout their recent ownership. Finally recognised and conserved after an extraordinary chance discovery at a garden furniture sale, they are now reattributed as lost Egyptian masterworks from one of Egypt’s most important sites.

A quintessentially Egyptian symbol, the sphinx has fascinated people for millennia. This enigmatic hybrid creature is perhaps best known from the Great Sphinx of Giza, built under pharaoh Khafre during the 4th Dynasty (c.2613 - 2494 BC) and which has become a national emblem of Egypt.

In antiquity, sphinxes were ubiquitous figures of Egyptian religious life. The lion, symbolising divine force, combined with the head of the pharaoh, alluded to the invincible strength of the king. The sphinx was a strong protective figure whose representations frequently served as guardians of sacred places. Nectanebo I (c.379-360 BC) became Pharaoh during a time of political uncertainty, marked by an increasing foreign presence and incursions led by the Persians, who had previously ruled the country between 525 and 404 BC. As a skilled army general, Nectanebo successfully repelled these attacks and established a period of peace and prosperity in Egypt. To cement his reputation as the defender of Egyptian traditions, he patronised a rich artistic production and strengthened religious institutions.

His reign is marked by his ambitious architectural projects, such as the magnificent temple of Isis at Philae and the great sphinx alley leading to the Serapeum of Memphis.

The Serapeum, located at Saqqara, the necropolis of the city of Memphis, was a giant complex of subterranean galleries which served as the burial chambers for the sacred Apis bulls. Only one bull was worshipped at a time and was kept in the temple of Ptah in Memphis. When it died, it was publicly mourned with a lavish ceremonial burial at the Serapeum. These burial rituals lasted for seventy days, culminating in a procession from the temple of Ptah to the Serapeum.

The Serapeum was frequently enlarged and improved by the Egyptian kings over the centuries. During the Heb Sed festival, celebrated during his thirtieth year on the throne, the pharaoh would run a race alongside the Apis bull as part of a series of rituals meant to prove his fitness to rule and restore his powers. This festival was the most important royal celebration in ancient Egypt. It is particularly noteworthy that all foreign dynasties in Egyptian history continued to donate generously to the Apis cult and improve the Serapeum, testifying to the utmost importance of the Serapeum to native Egyptians. The Apis cult was particularly popular during the Late Period, which might explain Nectanebo’s renovation project at the Serapeum, which included enlarging the temple and embellishing its gateway. A new processional alley, which was around 1120 metres long, was flanked by around 370 to 480 sphinxes. The sphinx alley occupied a crucial role in the cult of Apis, protecting the funerary procession bringing the sacred bull to its burial chamber.

The Serapeum was abandoned at the beginning of the Roman period, circa 30 AD, and many of its monuments, including the sphinxes, were progressively covered by the desert sands. Forgotten for centuries, the story of their discovery in the 19th century is both complex and fascinating.

‘There is a Serapeum at Memphis, in a place so very sandy that dunes are heaped up by the winds; some of the sphinxes which I saw were

buried even to the head and others Were only half-visible.’

Strabo, Geography, XVII.32

‘Beneath the Sand Upon Which I Stood...’

The Serapeum and its location in Memphis was known to early Egyptologists from the writings of ancient authors, such as Herodotus, Strabo, Pliny, and Plutarch, however it had long since been buried in the desert sands. Its rediscovery is generally attributed to French Egyptologist Auguste Mariette (1821-1881). A young, self-taught scholar, Mariette had been sent to Egypt by the Louvre in October 1850 to purchase Coptic, Syriac, Arabic and Ethiopian manuscripts. However, this mission quickly turned out to be a failure, and Mariette’s archaeological ambitions soon fixed upon a different objective: the Serapeum of Memphis. The quest to locate the Serapeum was largely inspired by the sphinxes he admired in the gardens of several prominent European men he visited in Alexandria and Cairo. Mariette was told that these sphinxes were sold by Solomon Fernandez, a Spanish-Jewish antiquities dealer who claimed to have discovered the Serapeum.

Hungry for discovery, Mariette set out to find the ancient site. At Saqqara, whilst trying to determine the plan of the tombs, Mariette came across a sphinx similar to those he had encountered in Cairo and Alexandria. According to a well-known legend – now part of Egyptological folklore – this reminded him of a quote by Strabo, which confirmed the importance of his discovery:

‘“One finds,” said the geographer Strabo (1st century AD), “a temple to Serapis in such a sandy place that the wind heaps up the sand dunes beneath which are sphinxes, some half buried, some buried up to the head.” Did it not seem that Strabo had written this sentence to help us rediscover, after over eighteen centuries, the famous temple dedicated to Serapis? It was impossible to doubt it. This buried Sphinx, the companion of fifteen others I had encountered in Alexandria and Cairo, formed with them, according to the evidence, part of the avenue that led to the Memphis Serapeum... Undoubtedly many precious fragments, many statues, many unknown texts were hidden beneath the sand upon which I stood. These considerations made all my scruples disappear. At that instant I forgot my mission (obtaining Coptic texts from the monasteries), I forgot the Patriarch, the convents, the Coptic and Syriac manuscripts... and it was thus, on 1 November 1850, during one of the most beautiful sunrises I had ever seen in Egypt, that a group of thirty workmen, working under my orders near that sphinx, were about to cause such total upheaval.’

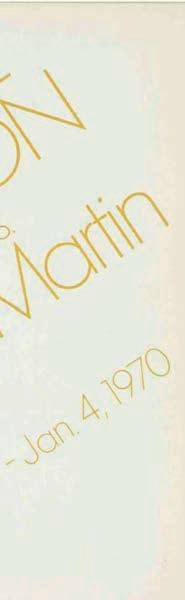

Above The present sphinxes, covered in mosses and lichens and with cement repairs in situ at Mander auctions, amongst miscellaneous garden ornaments. (Sphinx A, front. Sphinx B, behind).

The processional alley leading to the Serapeum has now been lost to the sands once again, and despite academic efforts throughout the twentieth century, it still needs to be fully explored. Full-size sphinxes from the Serapeum are seldom encountered outside of Egyptian museums. With the exception of the Louvre Museum in Paris, Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, and the Berlin Staatliche Museen, they are not represented in any major national museum collection. Indeed, they are notably absent from the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the British Museum, and the Egyptian Museum of Turin.

Whilst the iconic Serapeum sphinxes are absent from many of the leading museum collections of Egyptian art in the West, the present pair reappeared in the most unlikely of circumstances. Mistaken for 19th century copies, they had been used as patio ornaments for decades, before being dispersed in a garden furniture sale in October 2021.

The two sphinxes are depicted conventionally, portraying the face of the Pharaoh Nectanebo I on a lion’s body. They are shown seated, the powerful musculature of the body is finely carved, with tails curled round their haunches and forepaws outstretched. Both wear the nemes, the traditional royal headdress of the Pharaoh. The remnants of the uraeus, a stylised cobra and symbol of sovereignty and divine authority in ancient Egypt, is visible on Sphinx B, while a hollow area where the uraeus would have once been located is visible on Sphinx A. The two faces have been carved in an idealising but naturalistic style, typical of the period. They are broad and rounded, displaying a serene expression, the eyelids, noses, and gently smiling lips softly modelled in the limestone. The eyes have been deeply carved, especially around the canthi. The neck and jawline are soft and have a fleshy appearance.

Now rediscovered, fully researched and conserved, the sphinxes stand once again as icons of ancient Egyptian culture. Like the other sphinxes from this site displayed in the Louvre and Vienna, they bear the marks of graffiti left centuries after their creation by Greek and Roman travellers. Visited and venerated throughout the ages by subsequent pharaohs, later rulers and explorers, the sphinxes of the Serapeum of Memphis remain some of Egypt’s most famous and iconic temple sculptures.

81-78M YEARS BEFORE PRESENT | 50 CM HIGH | FOSSIL

Provenance

Discovered by M. Williams in the autumn of 2012 pursuant to a lease on the Murdock Ranch, Malta, Montana, a private ranch in the heart of the Upper Judith River Formation

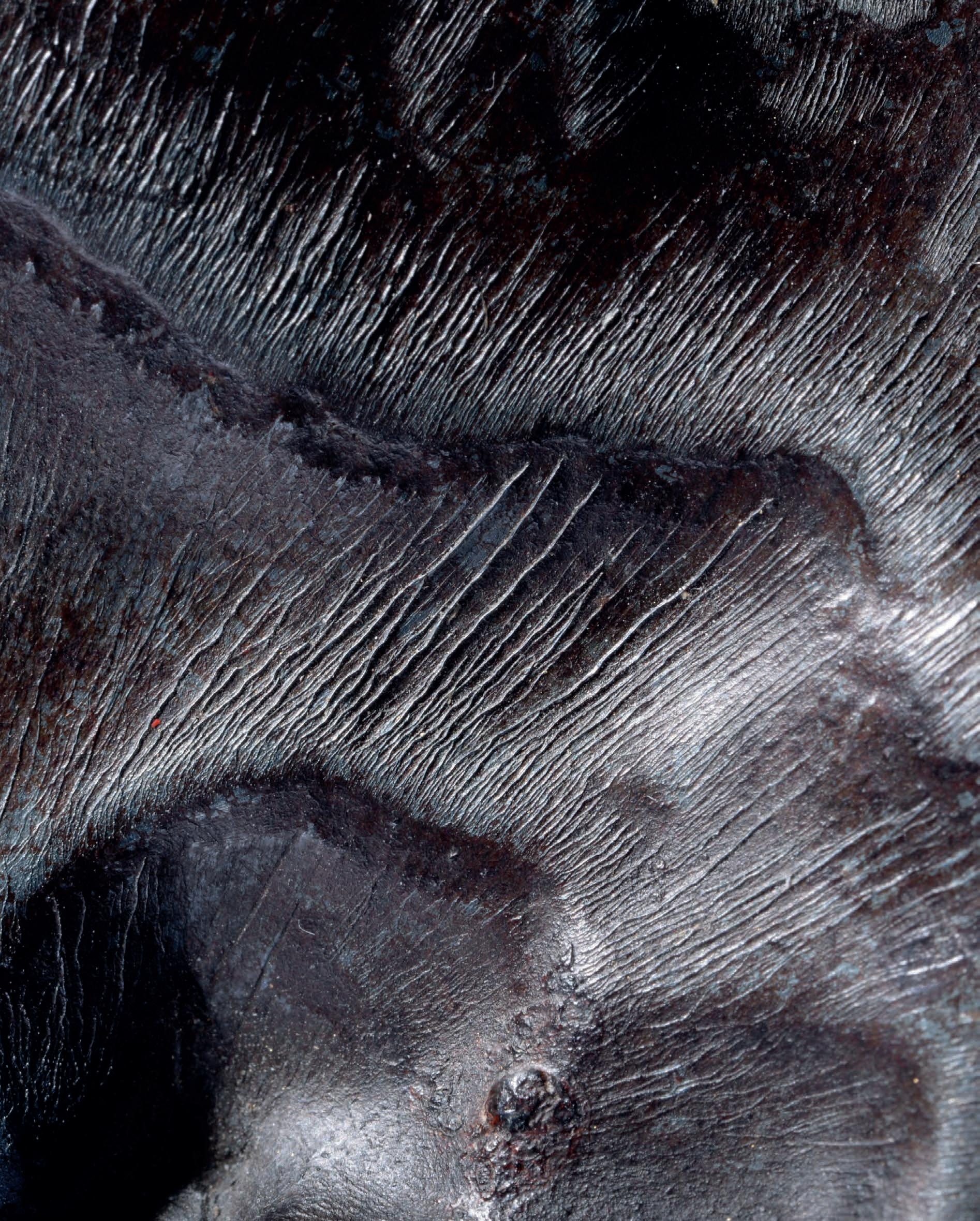

An extraordinarily large ‘mummified’ fossilised tail section from a mature Edmontosaurus, preserving not only the bones and tendons but, most remarkably, intricate skin impressions. Fossils that reveal soft tissue are among the rarest in paleontology, and this specimen is one of the finest known examples. The tail’s surface reveals a well-preserved pattern of polygonal defensive scales, which would have served as armour against predators, such as Tyrannosaurus rex

£110,000

1069-945 BC 16 CM HIGH WOOD & HIPPOPOTAMUS IVORY

Provenance

Acquired by Raoul Lacour (1845-1870) during his travels to Egypt in 1868-1869

Thence by descent

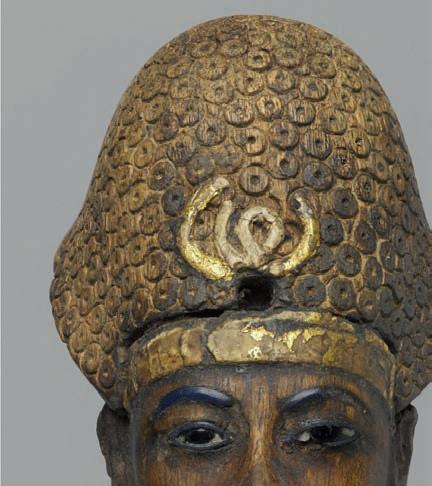

This mask is a glorious example of the technical skill and stylistic heights reached in 21st Dynasty Egyptian funerary art. The fine-grained wood has been meticulously carved and polished to an almost reflective finish, with rich ebony and lustrous hippopotamus ivory inlays enhancing its beauty. The mask’s exquisite craftsmanship and serene expression captures the essence of ancient Egypt’s reverence for perfection, immortality, and the afterlife.

525 BC | 21.6 CM HIGH BRONZE

Provenance

From the collection of Axel Guttmann (1944-2001), Berlin (Inv. no. AG564, H202)

Subsequently, The Art of Warfare: The Axel Guttmann Collection, Part 1, Christie’s, London, 6 November 2002, Lot 46

Subsequently, Antiquities, Christie’s, New York, 26 January 2023, Lot 75

Published

R. Hixenbaugh, Ancient Greek Helmets: A Complete Guide and Catalog, NewYork, 2019, p.390, cat. no. C382

This phase two Corinthian helmet is one of the most ambitious examples to have survived from antiquity. Forged with remarkable skill and polished to a fine lustre, it is further distinguished by its exquisite incised decoration. These engravings identify it as a rare variant of a type depicted on the British Museum’s Armento Rider. This helmet is the finest known example of its kind.

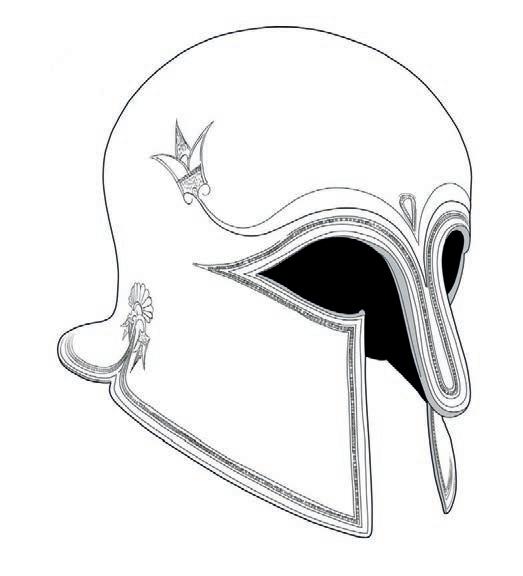

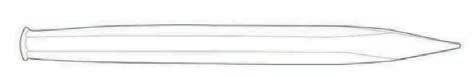

Bottom Line drawing of the present

Cast and hammered in bronze, with thickened nose guard and pointed cheek pieces, the rounded crown curving down into a flared neckpiece. The elegant curvilinear eye holes taper to a point, decorated with a punched and incised border decoration that follows the outer edge of the helmet. The side cut outs adorned with lotus flowers and palmettes above. The bull horns, modelled in light relief, swoop over the brow with finely chased lotus flowers blooming from the ends. An incised motif sits above the nose guard between the brows, probably depicting a lotus bud.

The Corinthian Helmet: The Bronzesmith’s Canvas

By the sixth century BC , decades of battle experience had resulted in further shaping of the first phase Corinthian helmet to better suit the wearer’s skull. This second phase helmet design, to which the present piece belongs, is identified by the elongated neckguard and curvilinear forms. Metallurgical advancements meant that the Corinthian helmet was now cast or hammered from one sheet of metal, which further resulted in the thickened nose guard extant in our example.

Artistically, a phase two Corinthian helmet was the bronzesmith’s canvas. Specifically characterised by greater ornamentation, many phase two helmets also share the archetypal decorative element of the bull horns, which originate from the narrowest point of the nose guard and follow the line ofthe eye cut outs to the edge of the brow. Bull horns were a clear choice for decoration. In many ancient societies, bulls were recognised for their strength and virility, and were widely associated with mythological and supernatural figures.

In wearing a helmet that bore large proud horns, the warrior cast himself as the formidable creature, and undoubtedly struck fear into the hearts of his enemies. The bull horns blossoming effortlessly into a lotus flower, however, is a particularly distinctive design type of the phase two Corinthian helmet.

Remarkably, this very helmet type is known from ‘one of the first and most powerful sculptural productions’ of Greater Greece (Magna Graecia), The British Museum’s Armento Rider. It is likely that helmets such as this were worn by members of the south Italian aristocracy. Only three extant versions preserving this type of ornamentation are known, of which ours is the finest and most complete. The two others are: a helmet fragment in the collection of the Museo Archeologico in Bari, found in Canosa, Italy; and a damaged helmet in the collection of the Musées Royaux d’Art et d’Histoire in Brussels, identified by The British Museum as a find from the ancient Egyptian port of Naukratis.

‘Tell me, Pistias... why do you charge more for your armour than any other maker?”

‘Because mine are better, Socrates.’

Xenophon, Memorabilia, Book 3, Chapter 10

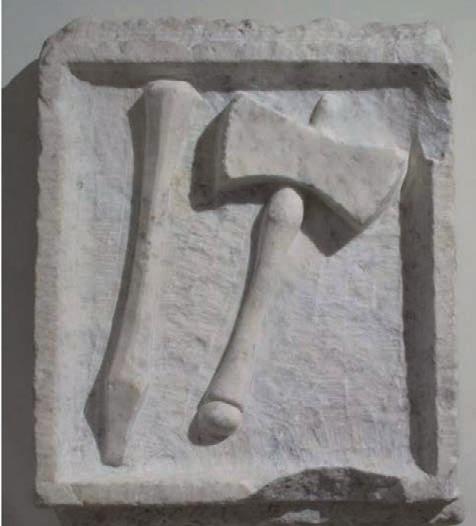

Provenance

Recovered from the River Saône, near Lyon [according to a handwritten inscription on the hilt] Collection of Monsieur F. B. (1950-2009), Normandy, France

Subsequently French art market 2021 Legally exported from France with French Cultural Property Passport 233626

An exceptionally well preserved Late Bronze Age Atlantic sword of the SaintNazaire type featuring finely incised decoration and an expertly cast leaf-shaped blade. Its provenance and golden patina hint to centuries of burial in a river-bed, where it was likely cast as a dedication to the gods .

£55,000

17 TH CENTURY OR EARLIER 28.5 CM HIGH SHELL

Provenance

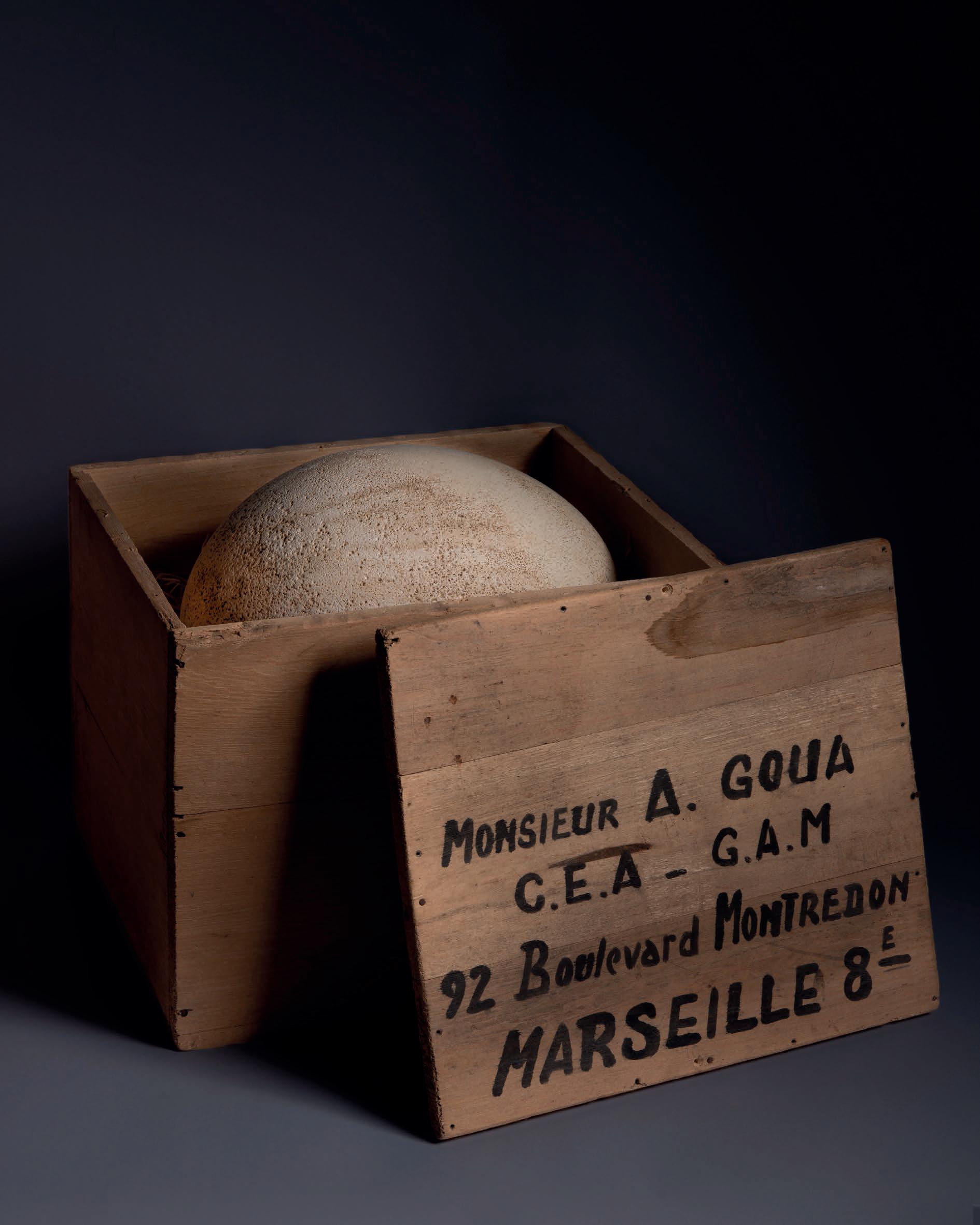

Collected on the island of Madagascar in the early 20th Century Collection of André Goua (1901-1997), acquired whilst working for the French Department of Mining Operations and Research in Antananarivo, Madagascar, between 1955 and 1965

Exported to Marseilles, France by 1965

Thence by descent

One of approximately 50 known intact eggs from the Aepyornis maximus. Prized since their discovery in the 17th century, Aepyornis eggs are the largest laid by any creature that ever existed, well eclipsing the size of any known dinosaur egg. This example is exceptionally well preserved, with a fine surface and original deposits. It is notable for its secure provenance, with original mid-century shipping crate.

£65,000

The now-extinct Aepyornis maximus, or elephant bird, was a quintessentially Malagasy bird, illustrative of the unique fauna and flora which developed on the island of Madagascar after its split from the Indian subcontinent around 88 million years ago. The bird’s Malagasy name was vorompatra (or vouropatra), meaning ‘marsh bird’ or ‘bird of the Ampatres.’ It measured over 3 metres in height and could weigh up to 540 kg. Aepyornis maximus was a flightless and wingless herbivore, and its large size and inability to fly may be the result of evolving on an isolated island with few predators. Instead of wings, however, elephant birds had extremely strong legs and could run at very high speeds.

In 1298, Marco Polo recounted seeing near Madagascar a bird of prey so big that it could carry an elephant in its talons. This bird was known as the roc, or rukh and may have given name to the elephant bird. It is even said that the Mongol Emperor Kublai Khan (1215-1294) sent messengers to Madagascar after having heard of the roc. The messengers brought back to the Great Khan a gigantic bird feather, now believed to have been a raffia palm.

The precise date of its extinction is unknown, with some first-hand sightings of the bird dating to the seventeenth century. In the second half of the nineteenth century, the German-Austrian geologist Ferdinand von Hochstetter wrote:

‘[Tidings] came establishing the fact that very recently a gigantic bird was, and is still existing in Madagascar. This happened thus: Natives of Madagascar had come to Mauritius to buy rum; the vessels they had brought with them to hold the liquor were egg-shells […] They related that those eggs were now and then found among the reeds, and that the bird also was occasionally seen.’

Aepyornis may have suffered from both climate change in Madagascar and the arrival of settlers throughout the centuries. Amongst the local people they were held sacred and it is possible that consuming their meat was taboo. Aepyornis eggs are the largest known across all animal species and are about three times bigger than the largest dinosaur eggs. Their circumference is about 1 metre and when full they weigh 15 kg. When the elephant bird was first scientifically described in the nineteenth century, public attention immediately focused on these enormous and intriguing eggs. Many specimens were brought back to Europe from Madagascar and were highly sought after by museums, universities, and collectors alike. Complete examples of Aepyornis maximus eggs are few and far between. Less than forty specimens are currently preserved in public institutions, many of which are reconstituted.

André Joseph Goua (1907-1997) was a successful and highly decorated French Naval officer. After his retirement from the navy, he led an equally successful career working for the French Atomic Energy Commission (CEA). After 1955, Goua worked in Antananarivo, Madagascar, eventually becoming head of the Africa-Madagascar department of the French Department of Mining Operations and Research (DREM).

He left Madagascar in 1965, and subsequently worked in Marseille, France, where the offices of the DREM were located. The present egg was acquired by Goua in Madagascar and remarkably still retains its original shipping crate.

1525-1425 BC | 28 CM HIGH PAINTED LIMESTONE

Provenance

1960s French private collection [based on notarised statement, surface condition, restorations and extant wooden base]

Subsequently art market, Montpellier France

Robert Shaw antiques, acquired from the above on 11 February 2020

An exceptional example of ancient relief work, carved during the apogee of Egyptian artistic production. Its style and superior material identifies it as being from the private tombs of the Theban necropolis, whose reliefs are widely regarded as the finest of the 18th Dynasty. Preserving a particularly poignant scene from the tomb of a high-status owner, it would have been the focal point of the wall decoration.

£280,000

4 TH - 2 ND CENTURY BC | 34.9 CM HIGH | MARBLE

Provenance

With Athenian dealer Moise Emanuelides, prior to 1924

Ernest Brummer, Paris & New York, acquired from the above, 14 June 1924

Ella Baché Brummer, acquired by descent from the above, 21 February 1964

Thence by descent to her nephew, Dr. John Laszlo, Atlanta, Georgia

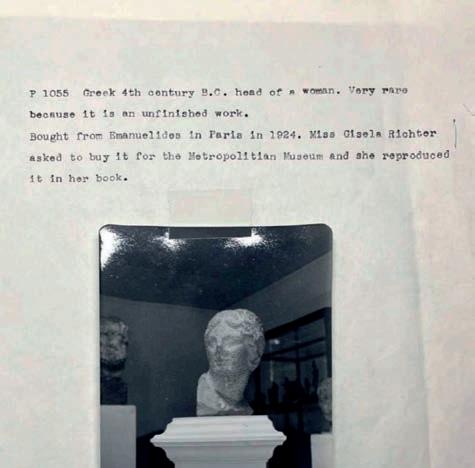

Published

G. Richter, The Sculpture and Sculptors of the Greeks, 3rd Edition, New Haven, 1950, p. 144 and fig. 433.

G. Richter, The Sculpture and Sculptors of the Greeks, 4th Revised Edition, New Havenand London 1970, p. 121 and fig. 472.

The Ernest Brummer Collection: Ancient Art, Vol. II, 16-19 October 1979, Galerie Koller and Spink & Son, Zurich, no. 623 (ill.).

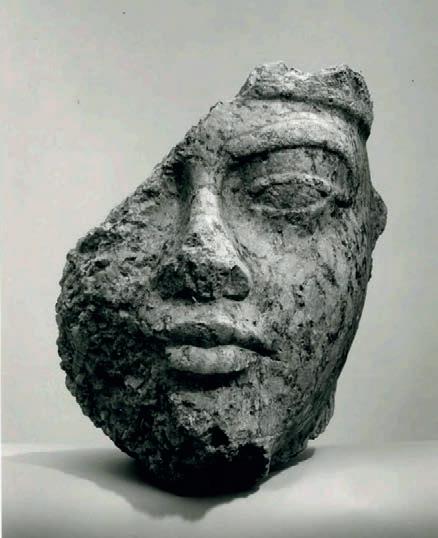

Perhaps the only known unfinished Greek marble head in private hands. An extraordinarily rare survival providing a snapshot of the artistic process at a critical moment in the Western art historical narrative. An evocative sculpture, laying bare the hand of the ancient artist, once in the collection of one of the foremost art dealers of the 20th century, Ernest Brummer.

Art in the Hellenistic Period

Alexander the Great died in 323 BC without an heir, leading to his generals - known as the Successors, or Diadochi - battling to divide his vast empire between them. This resulted in the formation of three main Macedonian kingdoms, and several smaller ones, in which kings ruled with heightened military and economic power. In order to establish themselves, these new realms needed settlers and soldiers, and with mercenaries, went eminent Greek thinkers, writers and artists seeking lucrative employment. As the Hellenistic kingdoms evolved into cosmopolitan centres, artists gained exposure to new cultures and ideas, along with access to a swathe of wealthy patrons. Catering to this new, diverse clientele, the art of the period developed an unprecedented dramatic and emotional quality. The complex composition of the statue of Laocoön and His Sons, the graceful drapery of the Nike of Samothrace, and the melancholy of the Dying Gaul, are all products of this artistic innovation. Moreover, rulers such as the Ptolemies began commissioning their portraits on coinage for the very first time, marking a significant shift in how leaders were represented.

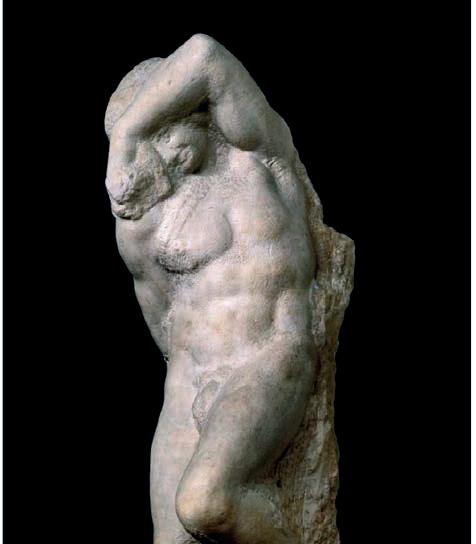

Gods and goddesses similarly began to be depicted as individuals, rather than idealised figures. A variety of new poses for Aphrodite emerged, from Praxiteles’ Aphrodite of Knidos (the first female nude in Greek art), to the depiction of the goddess crouching at her bath. As exemplified in the Lely Venus, her head is turned sharply towards her observer, while her hands cover her breasts in a moment of vulnerability. Technical and stylistic developments of the fifth and fourth centuries BC were crucial to the realisation of these works. In the Archaic period, carving in the round from a block of marble meant sculpting a relief on four planes, with the final figure envisioned from four right-angled positions: the front, the back, and both sides. However, in the fifth century, a decisive change occurred. The sculptor was no longer confined to these rigid views, and he used different perspectives to consider, approach and carve his figure. Such technical advancements culminated in a crescendo of artistic output, reverberating down the centuries and producing some of humanity’s greatest masterpieces.

Top Carnelian ring stone depicting a sculptor modelling a bust, c. 1st-3rd Century AD. D. 1.2 cm. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Acc. no. 81.6.48.

Bottom Statue of crouching Aphrodite, the Lely Venus. 2nd Century BC, 112 cm. British Museum, London.

In describing the Aphrodite of Knidos, Pliny lauded the sculpture as ‘superior to all statues, not only of Praxiteles, but indeed the whole world.’ While ancient writers often heaped great praise on artists and their works, they rarely discussed their methods. What sculptors wrote, such as that by the great Polykleitos in the fifth century BC, has been lost to the passing of time. Therefore, the works themselves, particularly those which still bear traces of chisel marks, become the primary source for understanding how they were made.

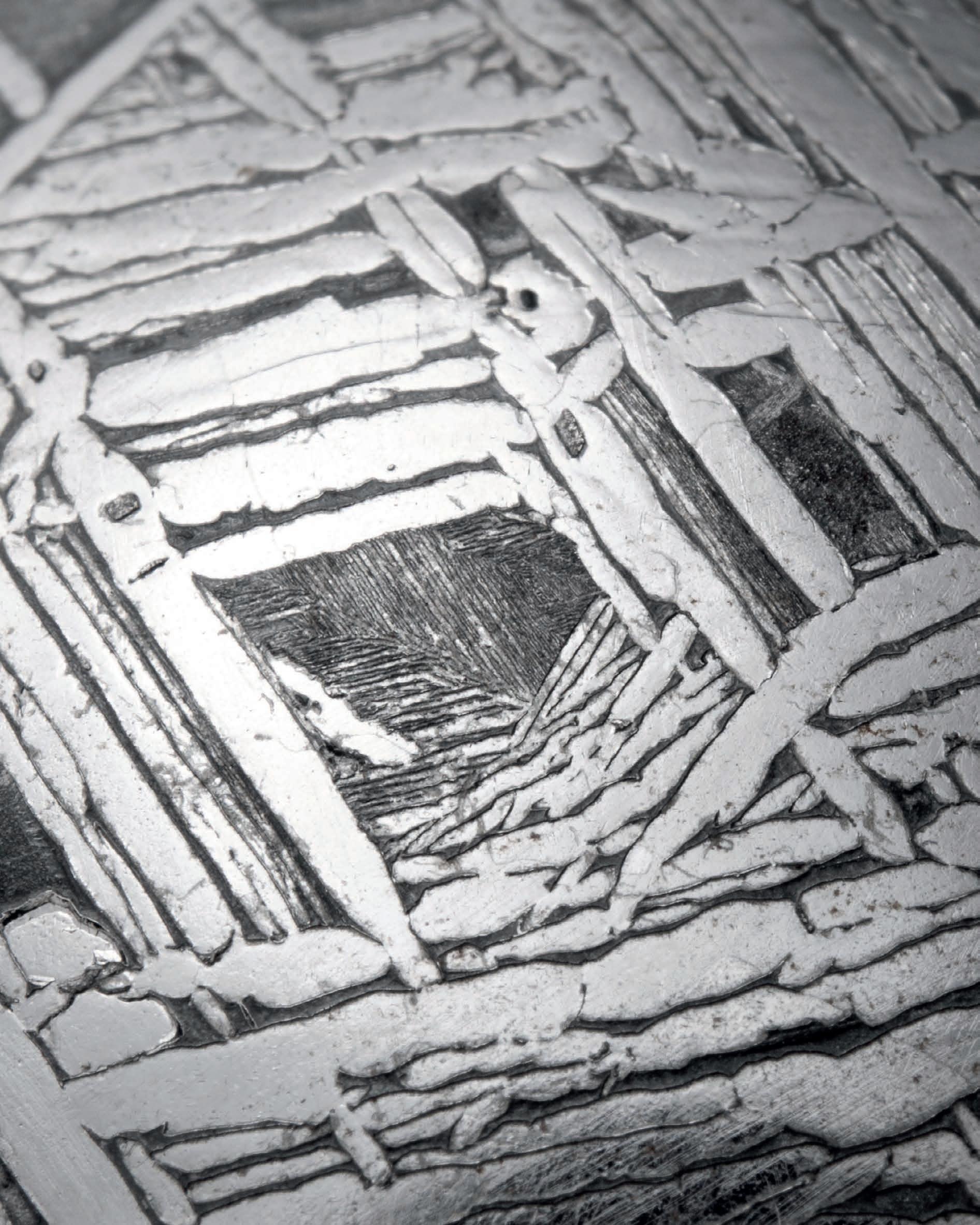

Identified by British archaeologist Gisela Richter as a crucial example, the present piece serves as a witness to this ancient artistic process. The crystalline structure of the stone indicates that Greek island marble was used, most likely either Parian or Naxian. The general employment of marble in Greek sculpture began in the seventh century BC, and was firmly entrenched by the sixth. Marble was quarried along natural fissures within the rock, and then cut into manageable blocks using saws and point chisels, before being transported to the sculptor’s workshop. Once in the workshop, the Hellenistic sculptor would use the point chisel, held at a low angle and skillfully struck with a mallet, to painstakingly remove layer upon layer of marble from the block until his creation was brought to life. Indeed, on the present piece, characteristic remains of the point chisel can be seen on the contours of the face and neck. The short furrows visible here were likely accomplished using the ‘mason’s stroke’, in which the point is held at a high angle to the stone to ensure greater control.

After the point chisel, the Hellenistic sculptor would have progressed to the ‘claw’ chisel. The claw chisel, widely believed to be a Greek invention, enabled the rough furrows created by the point to be broken up into finer and finer surfaces. It was the perfect tool for working sculptures in an intermediate stage, where a point was a riskier option due to its aggressive material removal and rasps would be too slow and inefficient. The present piece shows evidence of the claw chisel, in contrast to the rough furrows of the point.

Due to the value of high quality marble, Greek sculptors often used smaller blocks and skilfully pieced them together once modelling was complete. Heads in particular were often carved separately from the bodies and joined together by marble tenons, metal dowels and/or cement. The rectangular base of the present head was first shaped with the point chisel, before the claw chisel was used to smooth the surface. Although it may have been further narrowed for insertion into the draped neckline of a body, it may also have been intended for insertion as is.

As the sculptor reached closer to the final surface, finer tools were required. Claw chisels with more teeth, flat chisels, files and rasps helped in further modelling the details of the figure, before the surface was polished. Tell-tale marks of the flat chisel are visible here, for example, in the hairline and by the right temple.

This sculpture exemplifies the intermediate stage of creation, capturing the transition from the rough to the refined. While there is evidence of claw and flat chisel work, it remains at a preliminary stage.

The Hellenistic artist responsible for the present piece sat at the beginning of a legacy that reverberated down the centuries. Following the fall of the Roman Empire, the development of sculpture in Italy and Germany throughout the middle ages has been noted as similar to that of the Archaic carvers, while the ‘rediscovery’ of perspective in the Renaissance spurred once again the emergence of dynamic and lifelike creations in stone.

Works of the Renaissance master Michelangelo correspond technically with that of the sculptors of Hellenistic Greece. As with the present piece, this process can be seen in the chisel marks left on his Slaves, as well as other pieces such as his figure of St Matthew, or the Royal Academy’s Taddei Tondo.

The artist also pioneered the technique later known as non finito, deliberately leaving works unfinished to give them an expressive quality of infinite suggestiveness. Later sculptors, such as Auguste Rodin (1840-1917), also used the deliberately ‘unfinished’ technique in homage to the Renaissance master, and as symbols of the process of artistic creation. Rodin himself was similarly inspired by the art of ancient Greece, compiling a collection of over 6000 antiquities by 1900. Of Greek artists he said, ‘They have been and remain my masters.’

Top right Record of the present piece in the Brummer Archives, noting its rarity and offer to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

75M YEARS BEFORE PRESENT 42 CM DIAMETER FOSSIL

Provenance

Discovered in the Blood Reserve, Alberta, Canada With Canadian Export Licence

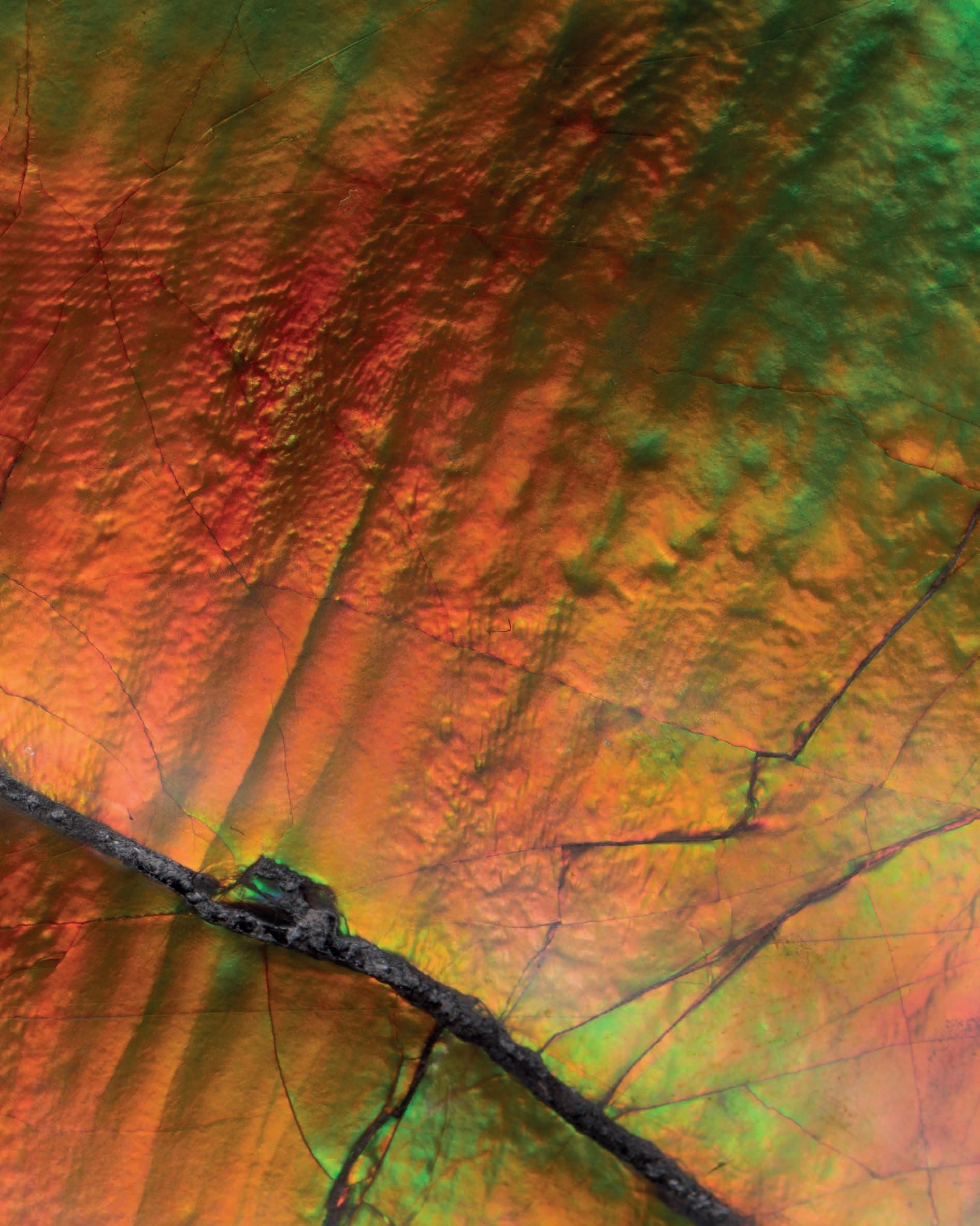

A magnificent example of one of the most spectacular fossils known. Many of the extraordinary ammonites recovered from the Bearpaw Formation suffer from compression and losses, requiring reconstruction from multiple individuals. This specimen is notable for its original condition and intense, unenhanced rainbow iridescence.

£75,000

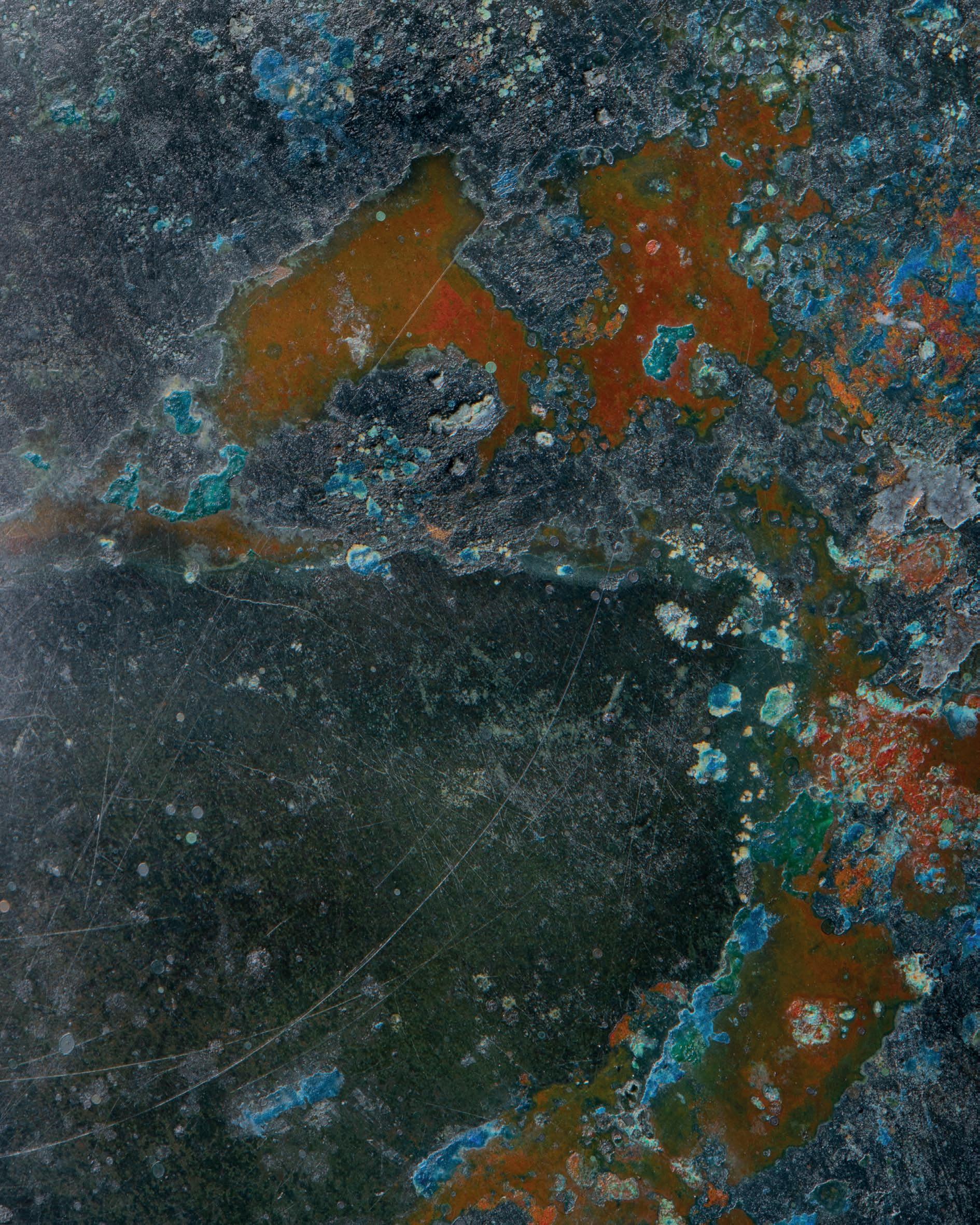

A magnificent example of one of the most spectacular of all fossils - a large and intensely vibrant ammonite, Placenticeras costatum, from the Bearpaw Formation, Alberta, Canada, dating to the late Cretaceous period, around 75 million years before present. The surface of this long extinct marine creature has transformed over millennia into a dazzling, iridescent gemstone, its colours shifting in the light from vivid reds to emerald greens, with flickers of orange and gold, purple and brilliant blues. This effect is a natural result of the fossilisation process, a unique phenomenon only found on ammonites recovered from this location.

The ammonite, an extinct branch of the mollusc family related to the modern octopus, takes its name from an ancient belief, recorded by Pliny the Elder that their fossilised remains were in fact the horns of the ram-horned Egyptian god Ammon, which would bring good fortune to the owner.

‘The Horn of Ammon, which is among the most sacred stones of Ethiopia, has a golden yellow colour and is shaped like a ram’s horn. The stone is guaranteed to ensure without fail that dreams will come true...’

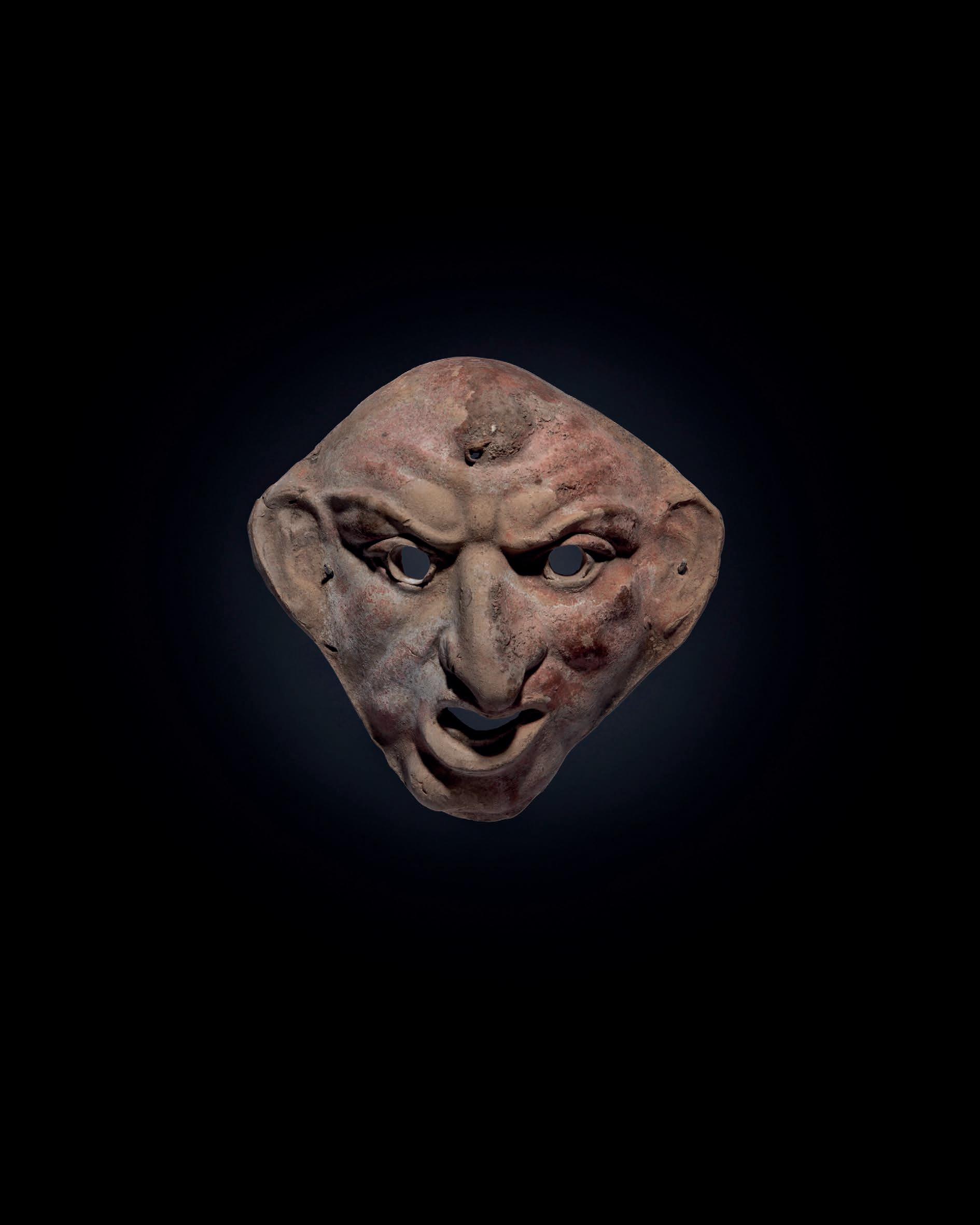

1 ST CENTURY BC - 1 ST CENTURY AD 20 CM HIGH | TERRACOTTA

Provenance

Collection of Louis-Gabriel Bellon (1819-1899), Saint-Nicolas-lez-Arras and Rouen

Thence by descent

This highly expressive terracotta mask is incredibly well preserved - and is perhaps the finest example of all known masks of the Maccus type. It depicts a man with grotesque, comically deformed features. Holes have been pierced through the forehead and on each side of the mask, by which it would once have been attached to a plinth or wall as a decorative object.

£65,000

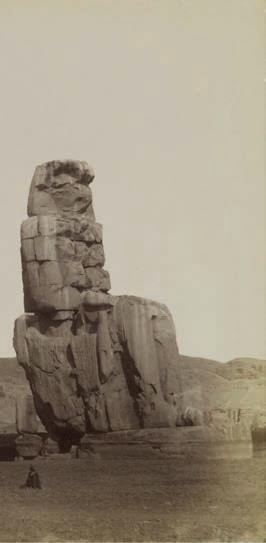

1390-1353 BC 24.4 CM HIGH | ASWAN GRANITE

Provenance

Ernst Kofler (1899 - 1989), Lucerne, Switzerland, by June 1970

Subsequently in the collection of Mr. and Mrs. Richard Manoogian, Michigan, acquired from the above by 23 December 1970

Subsequently, Ancient Egyptian Sculpture & Works of Art, Sotheby’s, New York, 8 December 2015, Lot 5, consigned by the above

Subsequently, U.S. private collection, acquired at the above sale

Published

Detroit Collects: Antiquities, Exhibition Checklist, by William H. Peck, The Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit, 1973, p. 3

J. Malek, et al, Topographical Bibliography of Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphic Tests, Statues, Reliefs and Paintings, Vol. VIII, Oxford, 1999, no. 800-732-720, p. 115

Exhibited

‘Detroit Collects Antiquities’, The Detroit Institute of Arts, 14 March - 29 April 1973

The only naturalistic depiction of Amenhotep III in private hands. An extraordinary masterpiece representing one of the most beautiful artistic styles of ancient Egypt. From an over-life-size statue of the king.

The 18th Dynasty is widely regarded as the zenith of ancient Egyptian culture. Founded by Ahmose I (r.c.1539-1514 BC), he and his successors expanded Egypt’s influence throughout the Near East and established control of Nubia through a series of successful military campaigns. As a result, the pharaohs of the New Kingdom commanded unimaginable wealth, inherent in the magnificent treasures of Tutankhamun’s tomb, which has come to define the dynasty in the popular imagination.

At the height of its political power, and with the support of everincreasing gold, Egypt’s art and architecture flourished. On the east bank of the Nile River, Luxor Temple, connected to Karnak by the Avenue of Sphinxes, stands as an icon of the successive building campaigns of 18th Dynasty pharaohs. This context of peace and prosperity also created an environment that enabled individual rulers to challenge visual traditions that had remained relatively unchanged for millennia. In establishing their own artistic and stylistic identities, the 18th Dynasty pharaohs have become known today as the architects of Egypt’s artistic Golden Age.

Of all the great 18th Dynasty rulers, the artistic production and legacy of Amenhotep III (r.c. 1390-1353 BC) stands unparalleled. Like his father before him, Amenhotep maintained crucial political relationships with external nations, allowing a surplus of peacetime manpower and gold to drive expansion elsewhere. He poured lavish wealth into the arts, financing glassmakers, potters and jewellers, who produced exquisite objects for use in both diplomacy and trade, as well as for the personal satisfaction of the ruler.

Of all Amenhotep III’s projects, his mortuary temple complex on the west bank of Thebes, now Kom el-Hetan, has proved to be his most remarkable achievement, and the jewel in the crown of his artistic legacy. Begun early in his reign, and enlarged throughout subsequent campaigns, it once housed thousands of sculptures, including over seven hundred seated and standing figures of the lion-headed goddess, Sekhmet, which today line the walls of every important public and private collection of Egyptian art all over the world.

Marking the entrance to the vast precinct are two icons of Egyptian civilisation, the Colossi of Memnon. Known as ‘Ruler of the Rulers’, these 21m high, awe-inspiring statues of Amenhotep have remained tourist attractions from Greek and Roman times until the present day. Considered by the ancient Egyptians to be gods in their own right, they now serve as archetypes of Amenhotep’s reign and patronage of the arts. No other New Kingdom pharaoh had such a long lasting impact on the art of ancient Egypt, and later rulers, as if acknowledging his achievements, appropriated Amenhotep’s vast statuary for their own purposes. Amenhotep’s cultural impact is perhaps only paralleled in later times with that of the Sun King, Louis XIV (1638-1715 AD).

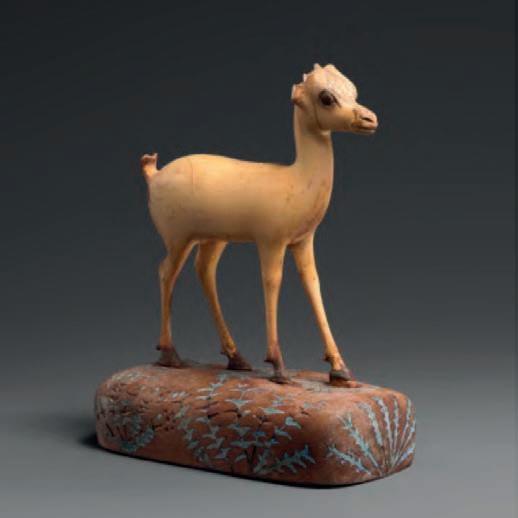

Top Gazelle. New Kingdom, 18th Dynasty, c.1390-1352 B.C. Ivory, wood, blue pigment. H. 11.6 cm. Metopolitan Museum of Art, New York. No. 26.7.1292.

Bottom Detail of Statuette of Amenhotep III, New Kingdom, 18th Dynasty, c. 1390-1352 B.C. Height 26.3 cm. Brooklyn Museum, 48.28.

The wealth that poured into Egypt during the 18th Dynasty also created a suitable atmosphere for artistic development. The increased appetite for luxury and influences from new cultures beyond Egypt drove a bolder use of materials, as well as considerable developments in the applied arts. While traditionally restricted by more formal stylistic conventions and subject matter, skilled Egyptian artisans were now starting to create beautiful objects of vertu as well as works of startling realism.

Identified by scholars to display both emerging trends is the example of an ivory statuette of a gazelle in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum. The same naturalistic treatment is also seen in the decorative agenda for Amenhotep’s Palace at Malkata, where floral and animal motifs in vibrant colours show a more realistic modelling and a freer treatment of the subject matter than the tomb paintings of the period.

While shoots of realism are seen within the decorative arts of the reign of Amenhotep III, there exists only a handful of objects where a naturalistic style can be seen in depictions of the pharaoh himself. Indeed, despite contentions among scholars concerning the various stylistic trends of his reign, Egyptologists and art historians Tom Hardwick, Raymond Johnson and Jacques Vandier agree on a select few portraits which show a naturalistic rendering of the king’s physiognomy.

In stark contrast to the more common ‘classical’ depictions of Amenhotep, with their idealised facial features, this remarkable group shows a strikingly different and nuanced style. These pieces are defined by a fuller appearance of the face, rounded nose, with subtly-modelled nasolabial folds, almond-shaped eyes with heavy upper eyelids at the outer corner, and, perhaps most notably, fleshy lips, which are downturned at the corners.

Represented by only a small number of works in different mediums, arguably the most important depictions of the pharaoh in this fleeting naturalistic style are the gypsum head of Amenhotep III found in the workshop of the master sculptor, Thutmose, and the dyad statue recently discovered at the king’s mortuary temple in Kom el-Hetan. Also noted frequently by scholars is the masterful small wooden statuette of Amenhotep from the Brooklyn Museum, in addition to a further three examples cited by Hardwick and others.

Though not depicting the pharaoh, other manifestations of this naturalistic style can be seen in one of the most well-known depictions of Amenhotep’s wife, Queen Tiye, discovered in the temple of Hathor at Serabit el-Khadim, as well as in a second depiction of her in the Ägyptisches Museum und Papyrussammlung, Berlin. Within Amenhotep’s reign, these works, many of which are masterpieces in the world’s greatest museums, appear to sit at the interlude between the early ‘classical’ style, and the later exaggerated youthfulness of his last decade style. Identified by Johnson, this later style was itself quickly extinguished by the artistic revolution of the Amarna period, under Amenhotep’s successor, Akhenaten. Indeed, this group presents a short period of artistic expression in which sculptors seem to have been unbound by traditional stylistic convention or the drastic revolution that followed. Capturing the reality of those who lived, and ruled, in ancient Egypt, they preserve arguably the most beautiful artistic style of the 18th Dynasty.

When in the possession of the Swiss dealer Ernst Kofler (1899-1989), by the summer of 1970, the present head was referred to as the ‘Amarna head’, most likely on account of the atypical rendering of the features. More recently, however, Tom Hardwick has conclusively identified that the present head is a new addition to this vanishingly rare and beautiful group of naturalistic sculptures dating to Amenhotep III’s reign.

As archetypal of this style, the present piece’s full cheeks and fleshy lips featuring puffy cupid’s bow are clear testimony to the skill of the sculptor, who was talented enough to breathe life into stone. Its stylistic similarity to other examples identified by scholars, such as the head from Thutmose’s workshop, and the statue from Kom el-Hetan, is a clear signifier of the importance of the present piece. On account of the stylistic similarities between this and the dyad statue, Hardwick has suggested that the present piece may also have originally been commissioned for the king’s mortuary temple at Kom el-Hetan.