Art D’Égypte is part of Culturvator, a multi-disciplinary cultural platform that works with private and public entities to activate spaces for cultural promotion across all creative disciplines, spanning everything from visual arts and film to heritage, design, and music.

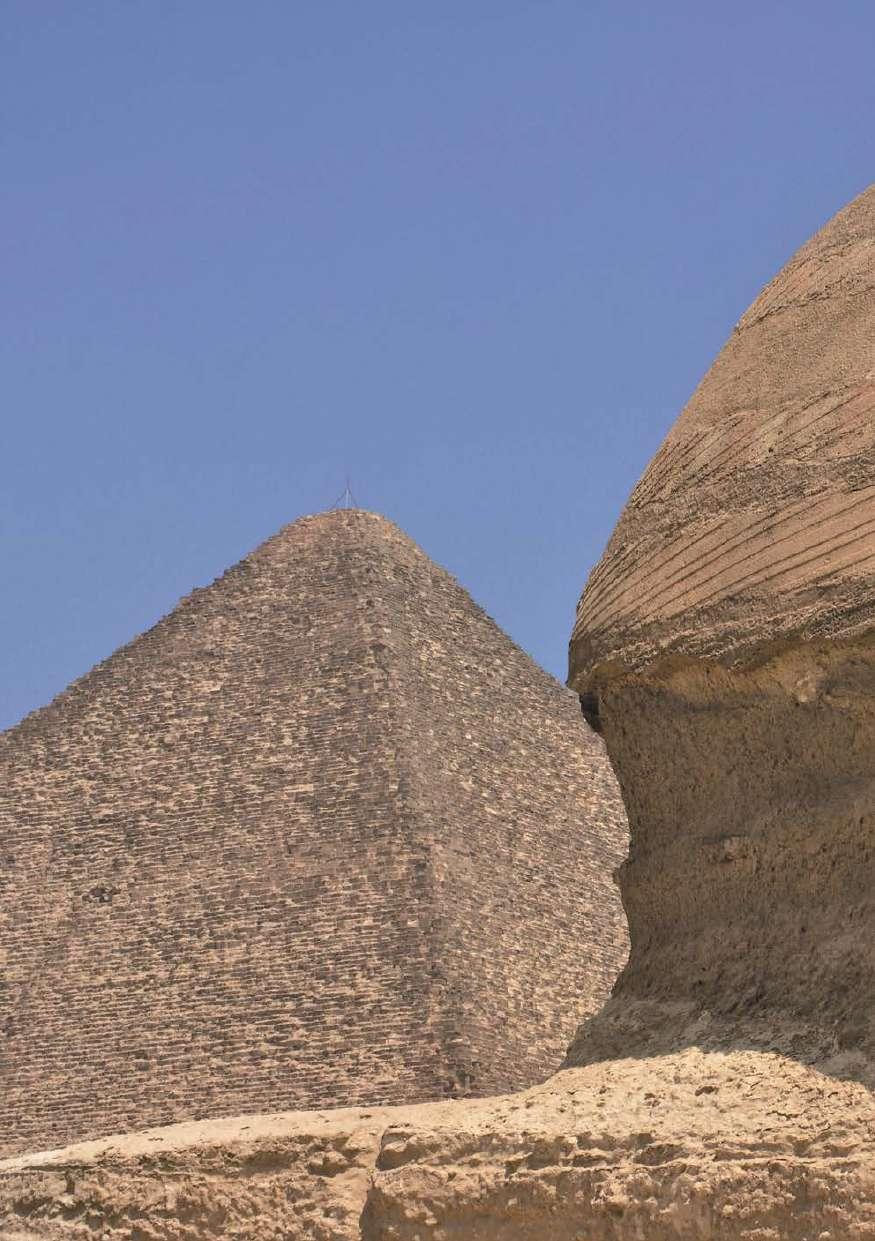

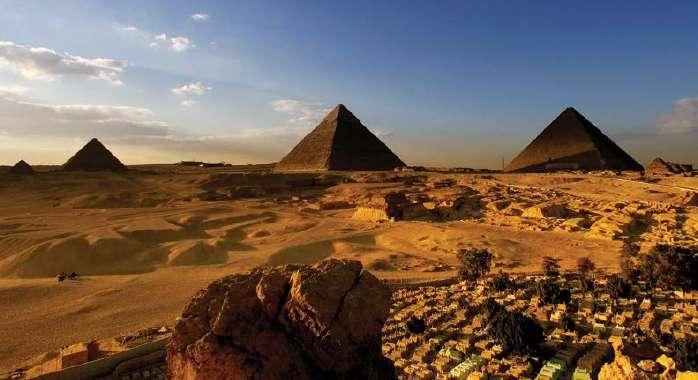

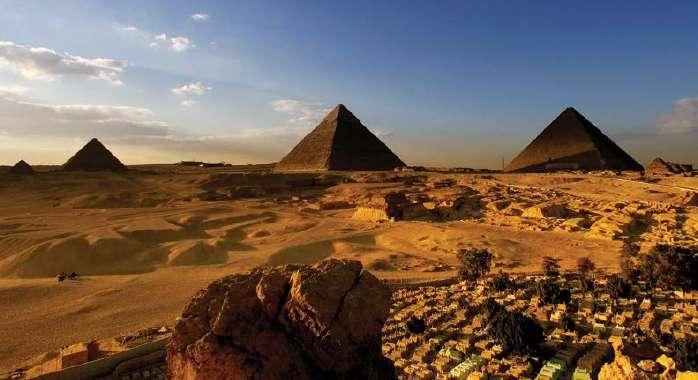

Art D’Égypte’s flagship event is its iconic yearly exhibition in a historic Egyptian location to shed light on the country’s cultural heritage and connect the art of Egypt’s past with that of the 21st century. Forever Is Now .02 is the fifth edition and follows four highly successful iterations: Eternal Light at the Egyptian Museum (2017); Nothing Vanishes, Everything Transforms at the Manial Palace (2018); Reimagined Narratives on al-Mu‘izz Street (2019); and Forever Is Now at the Pyramids of Giza (2021).

By raising awareness, Art D’Égypte’s target is to help preserve Egypt’s heritage and advance the international profile of modern and contemporary Egyptian art, presenting an alternative view of Egypt to the world.

This publication coincides with the exhibition Forever Is Now .02, on view from 27 October until 30 November 2022, at the Pyramids of Giza, Cairo, Egypt.

Curator

Nadine A. Ghaffar

Art D'Égypte

Rawan Abdulhalim

Nada Hassab

Hanya Elghamry

Alaa Elsayegh

Eman Omar

Book Design

Jorell Legaspi

Copyeditor

Nevine Henein

Project Manager

Nadine A. Ghaffar

Sadek El Moshneb

Amira Mostafa

Heidi Nasser

Omar Lotfy

Ayoub Saeed

Shahd Elwardany

Youssef Mansour

Mahmoud Abdel Kader

Ghada Gad

Printed in Egypt by our printing partner: www.saharaprinting.com info@saharaprinting.com

Cover image: MO4 Network

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any manner without permission. Unless otherwise specifed, all images are © the artists, reproduced with the kind permission of the artists and/ or their representatives.

© 2022 Art D'Égypte, Cairo, Egypt.

Polygon Building 6, 2nd foor, Unit D 2 Km 38 Cairo / Alexandria Desert Road +20237900115 / +201224706339 www.artdegypte.org

Every effort has been made to contact copyright holders and to ensure that all the information presented is correct. Some of the facts in this volume may be subject to debate or dispute. If proper copyright acknowledgment has not been made, or for clarifcations and corrections, please contact the publishers and we will correct the information in future reprintings, if any.

FOREVER IS NOW .02

CURATORIAL

ART D’ÉGYPTE

STATEMENT THE ARTISTS & ARTWORKS PARALLEL PROJECTS WRITINGS ON ART & HISTORY CONTRIBUTORS HONORARY CURATING BOARD HONORARY ADVISORY BOARD PATRONS INSTITUTIONAL PARTNERS CULTURE PARTNER EDUCATION PARTNER SPONSORS ART D'ÉGYPTE ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ARTISTS’ ACCOMPLISHMENTS 6 11 73 85 183 188 189 192 194 196 197 198 202 209 218 CONTENTS

Photo: Ted McDonnell on Pexels

Photo: Ted McDonnell on Pexels

FOREVER IS NOW .02

Nadine Abdel Ghaffar

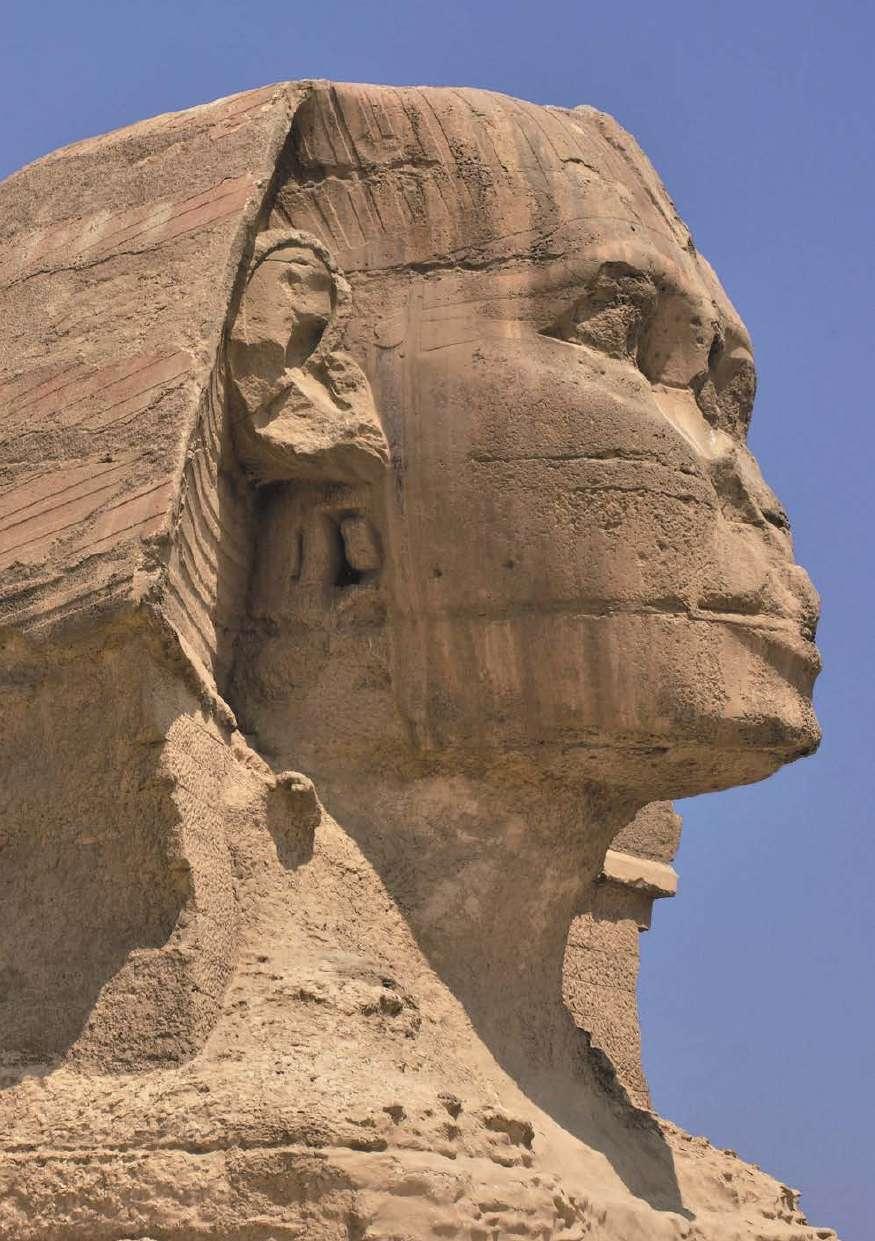

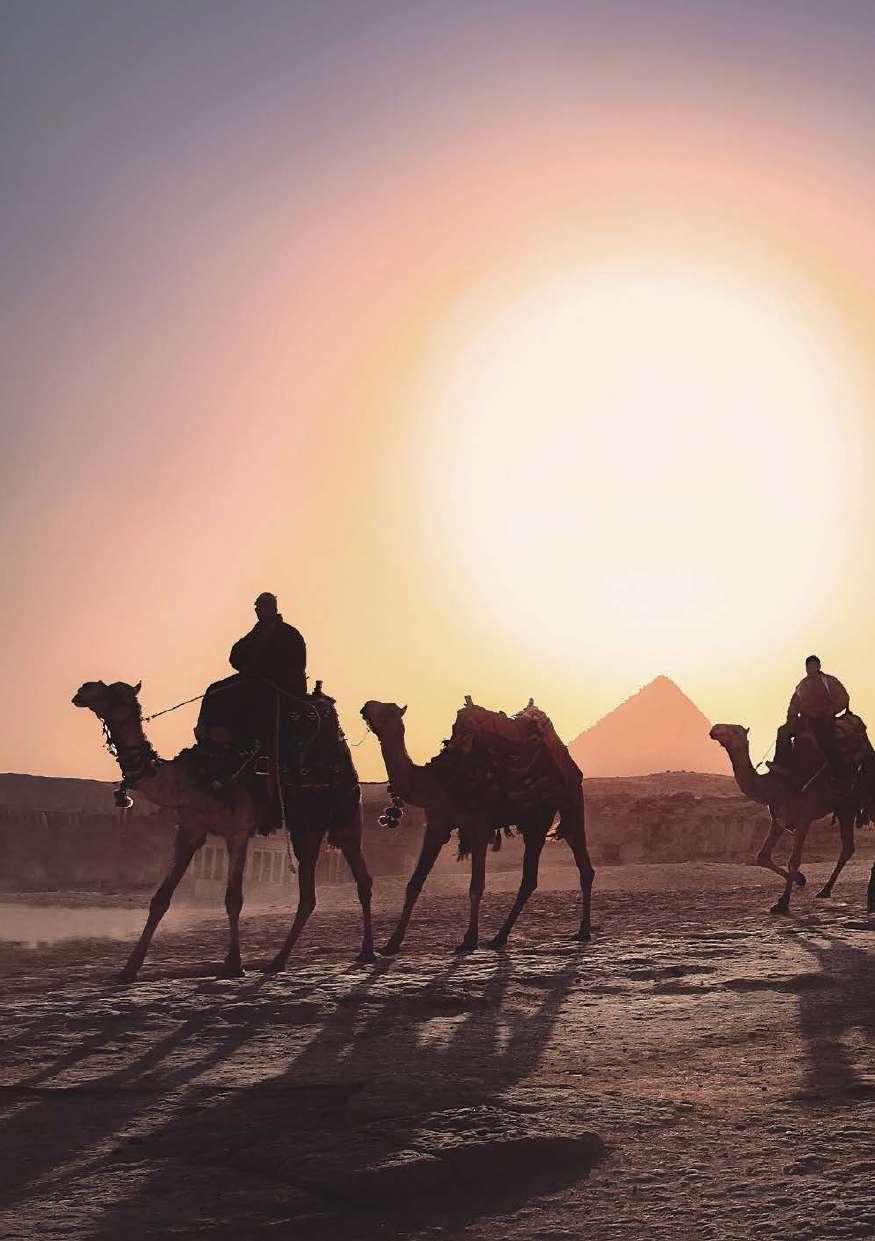

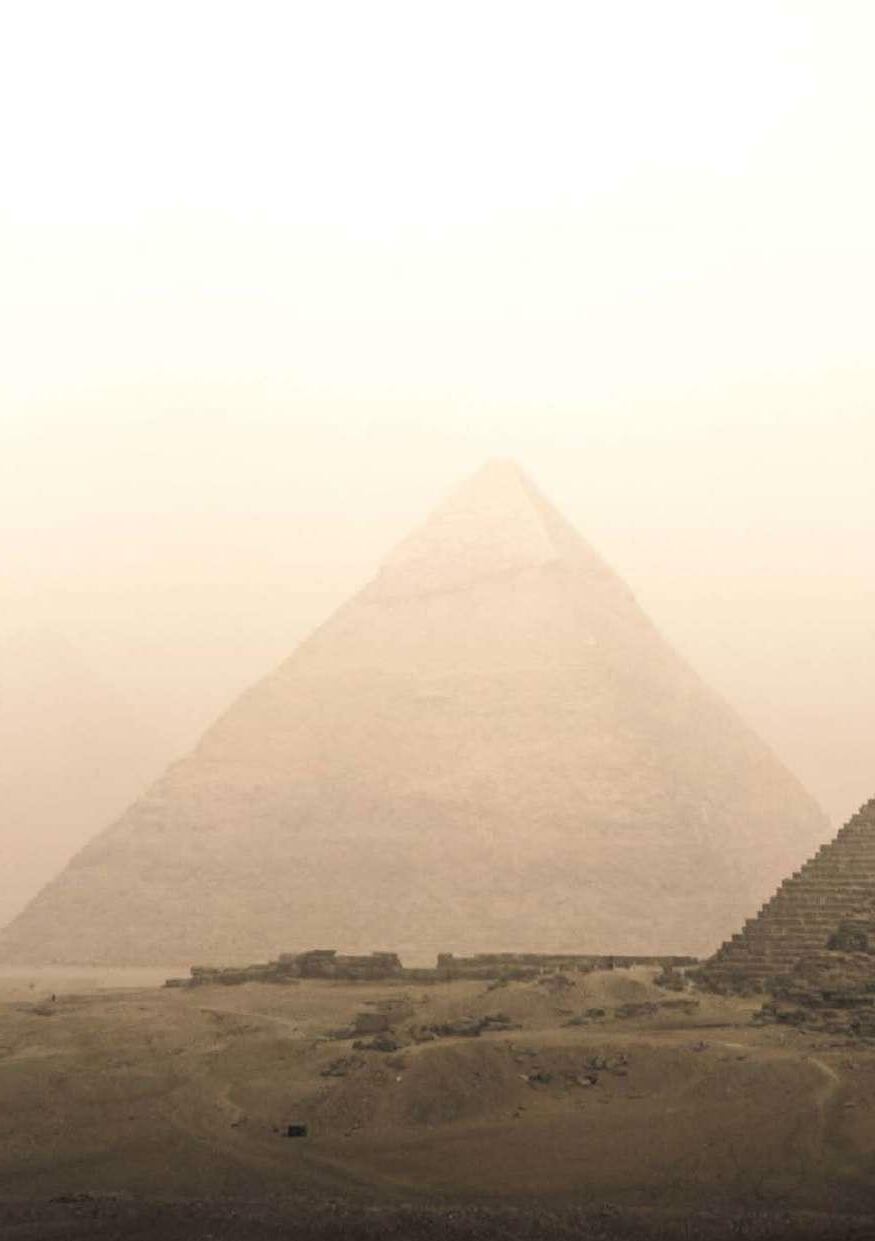

Forever Is Now .02 refects on time and timelessness, land and history, ecology and humanity, situating contemporary artworks at the magnifcent site of the Pyramids of Giza for the second time after the immense success of the frst edition in 2021. Through an immersive experience of public art, the exhibition envisions a future that is anchored in a deep knowledge of the past, indicating that there is no conception of the future without history, and that there is no time without the present.

Forever Is Now .02 is not simply a revival of history, for the past can never be complete in the present. Rather, it adds a contemporary artistic legacy to a place of worldwide signifcance, a place where nature was a divine force, where there were gods of the sun and of vegetation, and where animals were sacred manifestations. The pyramids, built in alignment with the rising and setting sun, point to a cycle of life, death, and rebirth and to the pathways from one world to the next, articulating connections between the terrestrial and the celestial.

The artists showcasing their work in Forever Is Now .02 have created pieces that respond to these links and rituals. Their artworks, made from a combination of natural and industrial materials, are in dialogue with Giza’s 4500-year-old iconic monuments of natural stone, pointing to our past and present conditions and the connections between man and technology, nature and inheritance.

FOREVER IS NOW .02 6

CURATORIAL STATEMENT

They ask questions such as: How do artists navigate between our ancient world and our technological futures, between eternal monuments and endangered environments? How can we move forward without the memory of ancestral teachings? What is the nature of our relationship to land amid our increasingly inhabited digital realities? How do artists become agents of change? How can we reshape the future? This year, Forever Is Now .02 coincides with Egypt’s hosting of the 2022 United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP27) in Sharm El Sheikh, further contextualizing our age of environmental crisis.

The overarching vision behind this project is to build a culture of interconnectivity and understanding, where dreams of the future feature the underrepresented, empower women, and demonstrate respect for the environment and an understanding of what we are leaving behind, both in terms of creativity and destruction. Bringing together these new site-specifc works by artists from around the world, Forever Is Now .02 is intertwined with communal participation. It espouses cross-cultural exchange with the local community and a high level of engagement with different publics, not just visitors but also craftspeople, students, and labourers, providing new ways of accessing contemporary art for the uninitiated.

Forever Is Now .02 is an ode to the transcendental power of art. Historical and global infuence converge and artists become co-creators, collaborators, and protagonists in a larger narrative where art becomes a collective responsibility, a dialogic conversation across time that enables artists to contribute their own story to history.

ART D’ÉGYPTE 7

ﻖﻴﺘﻌﻟا ﺎﻨﻤﻟﺎﻋ بورد ﻂــﺳو ﻦﻴﻧﺎﻨﻔﻟا ﻞﻘﻨﺗ ﺔــﻴﻔﻴﻛ لﻮﺣ تﻻؤﺎــﺴﺗ لﺎﻤﻋ ا ﻚــﻠﺗ حﺮــﻄﺗ ؛ﺮﻄﺨﻠﻟ ﺔﺿﺮﻌﻤﻟا تﺎــﺌﻴﺒﻟاو ةﺪﻟﺎﺨﻟا رﺎــﺛ ا حوﺮﺻ ﻂــﺳوو ،ﻲﺟﻮﻟﻮﻨﻜﺘﻟا ﺎﻨﻠﺒﻘﺘــﺴﻣو ﺎﻨﺘﻗﻼﻋ ﺎﻣو ؟داﺪــﺟ ا ﻢﻴﻟﺎﻌﺗ ةﺮﻛاﺬﺑ ظﺎﻔﺘﺣﻻا نود ﺎــﻣﺪﻗ ﻲﻀﻤﻟا ﺎﻨﻟ ﻦــﻜﻤﻳ ﻒــﻴﻛ نأ ﻦﻴﻧﺎﻨﻔﻠﻟ ﻦــﻜﻤﻳ ﻒﻴﻛ ؟ﺔﻴﻤﻗر ﻢﻟاﻮﻋ ﻞــﺧاﺪﺑ ﺎﻨﻨﻜــﺳ ﺪﻳاﺰﺗ ﻂــﺳو ﺔﻴﻠﻌﻔﻟا ضر ﺎــﺑ ؟ﻞﺒﻘﺘــﺴﻤﻟا ﻞﻴﻜــﺸﺗ ةدﺎﻋإ ﺎﻨﻟ ﻦﻜﻤﻳ ﻒﻴﻛو ؟ﺮﻴﻴﻐﺘﻟا ﻰﻠﻋ ةﺰــﻔﺤﻣ ﻞــﻣاﻮﻋ

ﺞــﺗﺎﻨﻟﺎﺑ

،ﻢﻟﺎﻌﻟا ءﺎﺤﻧأ ﻊﻴﻤﺟ ﻦــﻣ ﻦﻴﻧﺎﻨﻔﻟ ﺔﻴﻧاﺪﻴﻤﻟا لﺎــﻤﻋ ا ﻦــﻣ ةﺪــﻳﺪﺟ . ﺔﻴﻟﺎﻌﻔﻟا ﻲــﻓ ﻢﻬﺘﻛرﺎــﺸﻣ زﺰﻌﺗو ﻊﻤﺘﺠﻤﻟا داﺮﻓأ ﻊﻣ ﺎﻀﻳأ ضﺮﻌﻤﻟا ﺎــﻬﻣﺪﻘﻳ ﻲــﺘﻟا ﻒﻠﺘﺨﻣ كﺮــﺸﺗو ﻲﻠﺤﻤﻟا ﻊﻤﺘﺠﻤﻟا ﻊــﻣ ﻲﻓﺎﻘﺜﻟا لدﺎﺒﺘﻟا أﺪــﺒﻣ ﺔــﻴﻟﺎﻌﻔﻟا ﻰــﻨﺒﺘﺗ ﻚﻟذ ﻦﻤﻀﺘﻳ ﻞــﺑ ،ﻂﻘﻓ ضﺮﻌﻤﻟا راوز ﻚﻟﺬﺑ ﺪﺼﻘﻧ ﻻو ؛ﻊــﺳاو ﻞﻜــﺸﺑ ﺮــﻴﻫﺎﻤﺠﻟا ﻦﻴﺼﺼﺨﺘﻤﻟا ﺮــﻴﻐﻟ ﻚﻟﺬﺑ ضﺮﻌﻤﻟا ﺮــﻓﻮﻴﻟ ،لﺎﻤﻌﻟاو بﻼﻄﻟاو ﻦــﻴﻴﻓﺮﺤﻟا ﺔﻛرﺎــﺸﻣ ﺮﺻﺎﻌﻤﻟا ﻦﻔﻟا ﻊــﻣ ﻞﺻاﻮﺘﻠﻟ ةﺪﻳﺪﺟ ﺎــﻗﺮﻃ ﻦــﻴﺋﺪﺘﺒﻤﻟاو ؛ﻦﻔﻠﻟ ﺔﻴﻣﺎــﺴﺘﻤﻟا ةﻮﻘﻟﺎﺑ نﺎﻓﺮﻋ ةدﻮــﺸﻧأ ﺔﺑﺎﺜﻤﺑ ﻮﻫ ٢ ن ا ﻮﻫ ﺪــﺑ ا ضﺮــﻌﻣ نإ كرﺎــﺸﺘﻴﻟ ﺮﺻﺎﻌﻤﻟا ﻲﻤﻟﺎﻌﻟا ﺮﻴﺛﺄﺘﻟا ﻊــﻣ ﻲﻠﺤﻤﻟا ﻲﺨﻳرﺎﺘﻟا ﺮــﻴﺛﺄﺘﻟا ﺎﻬﺗﺎﻴﻃ ﻲــﻓ ﻰــﻗﻼﺘﻳ ﻪﻧﻮﻛ ﻦﻔﻟا ﺎﻬﻴﻓ ﻰــﻠﺠﺘﻳ ﺮﺒﻛأ ﺔﻳدﺮــﺳ لﺎﻄﺑأ نوﺮﻴﺼﻳو

FOREVER IS NOW .02 8

ﺮﻤﺗﺆﻤﻟ ﺮﺼﻣ ﺔﻓﺎﻀﺘــﺳا ﻊﻣ

ن

ا ضﺮﻌﻣ دﺎــﻘﻌﻧا فدﺎــﺼﺘﻳ ﻰﻠﻋ ﺪﻛﺆﻳ ﺎﻤﻣ ،ﺦﻴــﺸﻟا مﺮــﺸﺑ (٢٧ بﻮﻛ ) خﺎﻨﻤﻟا ﺮﻴﻐﺘﺑ ّ ﻲﻨﻌﻤﻟا ةﺪــﺤﺘﻤﻟا ﻢــﻣ ا ﺔﻴﻘﻴﻘﺣ ﺔــﻴﺌﻴﺑ ﺔﻣزﺄﺑ ﺮﻤﻳ يﺬﻟا ﺎﻧﺮﺿﺎﺣ قﺎﻴــﺳ ﻂﺑاﺮﺘﻟا ﻰﻠﻋ ﺰــﻜﺗﺮﺗ ﺔﻓﺎﻘﺛ ءﺎﻨﺑ ﻲﻓ عوﺮــﺸﻤﻟا اﺬﻫ ءارو ﺔﻠﻣﺎــﺸﻟا ﺔﻳؤﺮﻟا ﻦــﻤﻜﺗ ﻰﻠﻋ ﻞﻤﻌﺗو ،ﺔــﻣﺎﻌﻟا ةﺎﻴﺤﻟا ﻲﻓ ﺎﻠﻴﺜﻤﺗ ﻞــﻗ ا تﺎﺌﻔﻟا مﻼﺣأ مﺪــﻘﺗو ،ﻢــﻫﺎﻔﺘﻟاو ﻖﻠﻌﺘﻳ ﺎﻤﻴﻓ ءاﻮــﺳ ﺎﻧءارو كﺮﺘﻧ ﺎﻤﺑ ﺎﻴﻋوو ﺔــﺌﻴﺒﻠﻟ ﺎﻣاﺮﺘﺣا ﺮــﻬﻈﺗو ،ةأﺮــﻤﻟا ﻦــﻴﻜﻤﺗ ﺔﻋﻮﻤﺠﻣ ﻪﻤﻳﺪﻘﺗ ﻰــﻠﻋ ةوﻼﻋ ﺎﻬﻨﻋ

عاﺪﺑ ا ﻲــﻓ نﻮــﻧﺎﻨﻔﻟا ﻦﻴﻧﺎﻨﻔﻟ ﺢــﻴﺘﻴﻟ ﻦﻣﺰﻟا دوﺪﺣ ﻰﻄﺨﺘﻳ اراﻮــﺣ ﺎﻬﺗﺎﻤﻐﻧ ﻊﻨﺼﺗو ،ﺔــﻴﻋﺎﻤﺟ ﺔﻴﻟوﺆــﺴﻣ ةرﺎﻀﺤﻟا ﺦﻳرﺎﺗ ﻲــﻓ ﺔﻳﺎﻬﻨﻟا ﻲﻓ ﺐﺼﻴﻟ ﻲﺼﺨــﺸﻟا ﻢﻬﺨﻳرﺎﺘﺑ ﺔﻤﻫﺎــﺴﻤﻟا ﻦــﻳﺮﺻﺎﻌﻣ ﺔﻴﻧﺎﺴﻧ ا

اوﺮــﻴﺼﻳ

مﺎﻌﻟا اﺬﻫ

ا ﻮﻫ ﺪــﺑ

ﺮﻔــﺴﻳ ﻲﺘﻟا تﺎﻔﻠﺨﻤﻟا وأ ﻲــﻋاﺪﺑ ا

ﺔﺑﺮﺠﺘﻟا ﻚﺑﺎــﺸﺘﺗ

ضر او ،دﻮﻠﺨﻟاو ﻦﻣﺰﻟا ﻦــﻴﺑ ﺔﻗﻼﻌﻟا ﺔﻴﻧﺎﺜﻟا ﻪﺗرود ﻲــﻓ ن ا ﻮﻫ ﺪﺑ ا ضﺮــﻌﻣ ﻞــﻣﺄﺘﻳ تﺎﻣاﺮﻫأ ﻊﻗﻮﻣ ﻂــﺳو ةﺮﺻﺎﻌﻣ ﺔﻴﻨﻓ ﺎﻟﺎﻤﻋأ مﺪﻘﻴﻟ ؛ﺔﻴﻧﺎــﺴﻧ او ﺔــﺌﻴﺒﻟاو ،ﺦــﻳرﺎﺘﻟاو رﻮﺼﺘﻳ .٢٠٢١ مﺎﻋ ﻲﻓ ﻰــﻟو ا ﻪﺗروﺪﻟ ﻞﺋﺎﻬﻟا حﺎﺠﻨﻟا ﺪﻌﺑ ﺔــﻴﻧﺎﺜﻟا ةﺮﻤﻠﻟ بﻼــﺨﻟا ةﺰــﻴﺠﻟا ﺔﻠﺻﺄﺘﻣ هروﺬﺟ ﺎﻠﺒﻘﺘــﺴﻣ - ﺔﻴﻧاﺪﻴﻤﻟا لﺎــﻤﻋ ا ﻦﻣ ةﺮﻣﺎﻏ ﺔــﺑﺮﺠﺗ ﺮــﺒﻋ - ضﺮــﻌﻤﻟا ﻦﻋ ﺔﻳؤر ﻦﻳﻮﻜﺗ ﻦــﻜﻤﻳ ﻻ ﻪﻧأ ﻰﻟإ ﺮﻴــﺸﻳ ﺎﻤﻣ ،ﻲﺿﺎﻤﻟﺎﺑ ﺔــﻘﻴﻤﻌﻟا ﺔــﻓﺮﻌﻤﻟا ﻲــﻓ نود ﻦﻣﺰﻟا مﻮﻬﻔﻣ ﻰــﻟإ ﺮﻈﻨﻟا ﻦﻜﻤﻳ ﻻو ،ﺦﻳرﺎﺘﻟا ﻲــﻓ نﺎﻄﺒﺘــﺳﻻا

ART D’ÉGYPTE 9

نود ﻞﺒﻘﺘــﺴﻤﻟا ﺔﻴﻧ ا ﺔﻈﺤﻠﻟا ﻰــﻟإ تﺎﻔﺘﻟﻻا نأ اﺪﺑأ ﻦﻜﻤﻳ ﻻ ﻲﺿﺎﻤﻟا ن ؛ﺦــﻳرﺎﺘﻟا ءﺎﻴﺣ ﺔﻟوﺎﺤﻣ دﺮــﺠﻣ ﺲﻴﻟ ٢ ن ا ﻮــﻫ ﺪــﺑ ا ﻦﻔﻟا ﻦﻣ ﺎﺛرإ ﻒﻴﻀﻳ نأ ضﺮــﻌﻤﻟا لوﺎﺤﻳ ﻦﻜﻟو ،ﺮﺿﺎﺤﻟا ﻲــﻓ هﺮــﻳﻮﺼﺗ ﻞــﻤﺘﻜﻳ ﺖﻧﺎﻛ ﻊﻗﻮﻣ ﻮﻫ ،ﻢــﻟﺎﻌﻟا ىﻮﺘــﺴﻣ ﻰﻠﻋ ةﺮﻴﺒﻛ ﺔﻴﻤﻫأ ﻞﻤﺤﻳ ﻊــﻗﻮﻤﻟ ﺮــﺻﺎﻌﻤﻟا ﺲﻤــﺸﻟا ﺔﻬﻟآ ﺎﻬﻧﻮﻀﻏ ﻲﻓ تﺮﻀﺣ ﺔﻴﻬﻟإ ةﻮــﻗ ﺔﺑﺎﺜﻤﺑ ﺮﺒﺘﻌﺗ ﺔــﻌﻴﺒﻄﻟا ﻪــﻴﻓ ﺔــﺳﺪﻘﻣ تﺎﻴﻠﺠﺗ ﺔﺑﺎﺜﻤﺑ ﺎﻬﺿرأ ﻰﻠﻋ ﺶــﻴﻌﺗ ﻲﺘﻟا تﺎﻧاﻮﻴﺤﻟا تﺮــﺒﺘﻋاو ،تﺎــﺒﻨﻟاو ﻰﻟإ - ﺲﻤــﺸﻟا بوﺮﻏو قوﺮــﺷ ﺔﻛﺮﺣ ﻊﻣ يزاﻮﺘﻟﺎﺑ ﺖﻴﻨﺑ ﻲﺘﻟا - تﺎﻣاﺮﻫ ا ﺮﻴــﺸﺗ ﻰﻠﻋ ةﺪﻛﺆﻣ ،ﻪﻴﻟﺎﺗ ﻰــﻟإ ﻢﻟﺎﻋ ﻦﻣ رﻮﺒﻌﻟا قﺮﻃ ﻰــﻟإو ،ﺚﻌﺒﻟاو تﻮــﻤﻟاو ةﺎــﻴﺤﻟا ةرود . يوﺎﻤــﺳ ﻮﻫ ﺎﻣو ﻲﺿرأ ﻮﻫ ﺎﻣ ﻦﻴﺑ ﺔــﻗﻼﻌﻟا ﺎﻟﺎﻤﻋأ ٢ ن ا ﻮﻫ ﺪﺑ ا ضﺮــﻌﻣ ﻲﻓ ﻢﻬﻟﺎﻤﻋأ نﻮﺿﺮﻌﻳ ﻦــﻳﺬﻟا نﻮــﻧﺎﻨﻔﻟا ﻊــﻨﺻ ﻂﻴﻠﺧ ﻦﻣ ﺔﻋﻮﻨﺼﻤﻟا - ﻢــﻬﻟﺎﻤﻋأ ﻞﺧﺪﺗو سﻮــﻘﻄﻟاو تﻼﺼﻟا ﻚﻠﺗ ﻰــﻟإ ﺐﻴﺠﺘــﺴﺗ ﺔﻨــﺳ ٤٥٠٠ ﻰﻟإ ﻊﺟﺮﺗ ﻲﺘﻟا ةﺰﻴﺠﻟا رﺎﺛآ ﻊﻣ راﻮﺣ ﻲﻓ - ﺔــﻴﻋﺎﻨﺻو ﺔــﻴﻌﻴﺒﻃ تﺎــﻣﺎﺧ ﻦــﻴﺑ ﻞﻜــﺷ ﻦﻴﺑ ﺔﻗﻼﻌﻟا ﻰﻟإ ﻚﻟﺬﺑ ةﺮﻴــﺸﻣ ،ﻪﻨﻣ ﺔﻋﻮﻨﺼﻤﻟا ﻲــﻌﻴﺒﻄﻟا ﺮــﺠﺤﻟا ﺐــﻃﺎﺨﺘﻟ ﺔﻌﻴﺒﻄﻟاو ،ﺎــﻴﺟﻮﻟﻮﻨﻜﺘﻟاو نﺎــﺴﻧ ا ﻦﻴﺑ ﺔﻗﻼﻌﻟا ﻰﻟإو ،ﺮﺿﺎﺤﻟا ﻦﻴﺑو ﺔــﻴﺿﺎﻤﻟا ﺎــﻨﺗﺎﻴﺣ هﺎﻳإ ﺎﻨﻔﻠﺨﺗ يﺬــﻟا ثاﺮﻴﻤﻟاو رﺎــﻔﻐﻟا ﺪﺒﻋ ﻦــــﻳدﺎﻧ ضﺮﻌﻤﻟا ﺔﻘــﺴﻨﻣ ﺔﻤﻠﻛ ٢ نﺂــﻟا ﻮﻫ ﺪﺑﺄـــﻟا

Photo: Simon Berger on Unsplash

Photo: Simon Berger on Unsplash

THE ARTISTS & ARTWORKS نو�ا��لا و ����لا

AHMED KARALY

A P YRAMID I N O THER V OCA B ULARIES

Steel, plexiglass

6 m x 9 m x 4 m 2022

'When you are fascinated by something, you see it in everything.

My fascination with the many civilisations of Egypt has made me see them as one entity, each reflecting the other. From another visual dimension, I see them completely intertwined, no matter how different their details are.

This project represents the merging between the ancient Egyptian and the civilisations that followed it in a contemporary rendering that interprets what I see.'

FOREVER IS NOW .02 12

Sponsored by Qatari Diar Egypt Fabricated by Amr Helmy Design House

ﺪﻌﺑ ﻦﻣو . ﺎــﻀﻌﺑ ﺎــﻬﻀﻌﺑ ﺲــﻜﻌﺗ . ﺎﻬﺒﻴﻟﺎــﺳأ ﺖﻔﻠﺘﺧا ﻢﻳﺪﻘﻟا يﺮﺼﻤﻟا ﻦــﻴﺑ ﺞﻣﺪﻟا ﻦــﻣ ﺔﻟﺎﺤﻟا هﺬﻫ ﻞﺜﻤﻳ عوﺮــﺸﻤﻟا اﺬــﻫو

ART D’ÉGYPTE 13 ءﻲــﺷ ﻞﻛ ﻲﻓ هاﺮﺗ ،ءﻲــﺸﺑ ﻦﺘﺘﻔﺗ ﺎﻣﺪﻨﻋ " اﺪﺣاو ﺎﻧﺎﻴﻛ ﺎــﻫارأ ﻲﻨﻠﻌﺟ ﺮﺼﻣ ﺎــﻬﺘﺠﺘﻧأ ﻲــﺘﻟا تارﺎــﻀﺤﻟﺎﺑ ﻲــﻧﺎﺘﺘﻓاو ﺎﻤﻬﻣ ﺎﻣﺎﻤﺗ ﺔــﺟﺰﺘﻤﻣ ﺎــﻫارأ ﺮﺧآ يﺮﺼﺑ

". ﺎﻧأ هارأ ﺎﻣ ﻞﺜﻤﺗ ﺔــﻴﺛاﺪﺣ ةرﻮﺻ ﻲﻓ ﻦــﻜﻟو هﺪﻌﺑ ﺖــﻟاﻮﺗ تارﺎــﻀﺣو سوﺎﻫ ﻦﻳاﺰﻳد ﻲﻤﻠﺣ وﺮــﻤﻋ ﻊﻴﻨﺼﺗو ،ﺮﺼﻣ رﺎﻳد يﺮــﻄﻗ ﺔــﻳﺎﻋﺮﺑ ﻲـــــﻠﻋﺮـﻗ ﺪﻤﺣأ تادﺮـﻔـﻤـﺑ مﺮﻫ ىﺮــﺧأ ﻲــﺴﻜﻴﻠﺑ جﺎﺟز ،ﺐﻠﺻ م٤ × م٩ × م٦ ٢٠٢٢

AHMED KARALY

A PYR A MID I N OTHER

V O C A BUL A RIES

Photo: MO4 Network

ﻲـــــﻠﻋﺮـﻗ ﺪﻤﺣأ تادﺮـﻔـﻤـﺑ مﺮﻫ ىﺮــﺧأ

Ahmed Karaly graduated from the Faculty of Fine Arts in 1994 and participated in the annual Youth Salon exhibition organised by the Ministry of Culture where he received numerous awards. His first solo exhibition took place at the Mashrabia Gallery of Contemporary Art in 2002. He subsequently participated in the Aswan International Sculpture Symposium (AISS), the first of many international symposia for stone sculpture around the world.

In 2005, he received the State Award for creativity and travelled to Italy, where he presented his project al-Masrkhankiyeh , a reconstruction of Islamic architecture in sculptural form, creating a vision for an entire city starting with its gates. The project was presented at the Egyptian Academy of Fine Arts in Rome in 2006 and at the Gezira Centre for the Arts in Cairo in 2008. Karaly is currently working on completing this sculptural city.

FOREVER IS NOW .02 16

ﺔﻠﻴﻤﺠﻟا نﻮــﻨﻔﻟا ﺔﻴﻠﻛ ﻦــﻣ ﻪﺟﺮﺨﺗ ﺪﻌﺑ ﺔــﻴﻨﻔﻟا ﻪﺗﺎــﺳرﺎﻤﻣ أﺪﺑ ﻲــﻠﻋﺮﻗ ﺪــﻤﺣأ ةرازو ﻪﻤﻈﻨﺗ يﺬﻟا يﻮﻨــﺴﻟا ضﺮﻌﻤﻟا ،بﺎﺒــﺸﻟا نﻮﻟﺎﺻ ﻲﻓ ﻪﺘﻛرﺎــﺸﻤﺑ ١٩٩٤ ﻪﻨــﺳ ﺲﺤﻟا ﻪﻳﺪﻟ ىﺮــﺛأ يﺬﻟاو ﺰﺋاﻮﺠﻟا ﻦﻣ ﺪــﻳﺪﻌﻟا ﻰﻠﻋ ﻞــﺼﺣ ﺚــﻴﺣ ،ﺔــﻳﺮﺼﻤﻟا ﺔــﻓﺎﻘﺜﻟا ﺔﻴﻠﺤﻤﻟا ضرﺎــﻌﻤﻟا ﻦﻣ ﺪﻳﺪﻌﻟا ﻲــﻓ ﺔﻛرﺎــﺸﻤﻠﻟ ﻚﻟذ ﺪﻌﺑ ﻪــﻌﻓد ﺎــﻤﻣ ﺔــﻴﻓاﺮﺘﺣﻻﺎﺑ نﺎﻛ ﺎﻤﻛ ،٢٠٠٢ مﺎﻋ ﺔﻴﺑﺮــﺸﻤﻟا يﺮﻴﻟﺎﺠﺑ لو ا صﺎــﺨﻟا ﻪــﺿﺮﻋ نﺎﻛ ﺔــﻴﻟوﺪﻟاو تﺎﻣﻮﻳزﻮﺒﻤــﺴﻟا ﻢﻟﺎﻋ ﻲﻓ لﻮﺧﺪﻠﻟ ىﺮــﺧأ ﺔﻳاﺪﺑ ﺖﺤﻨﻠﻟ ﻲــﻟوﺪﻟا ناﻮــﺳأ مﻮﻳزﻮﺒﻤــﺳ ﻲﺘﻟا عاﺪﺑ ﻟ ﺔــﻟوﺪﻟا هﺰﺋﺎﺟ ﺖﻧﺎﻛو ﻢــﻟﺎﻌﻟا

ART D’ÉGYPTE 17

لود ﻦﻣ ﺪﻳﺪﻌﻟا ﻲــﻓ ﺖــﺤﻨﻠﻟ ﺔــﻴﻟوﺪﻟا أﺪﺑ ﺚﻴﺣ ﻪﺗﺎﻴﺣ ﻲــﻓ ةﺮﻴﺒﻛ ﺔــﻠﻘﻧ ﺎﻴﻟﺎﻄﻳإ ﻰــﻟإ ﺮﻔــﺴﻠﻟ ٢٠٠٥ مﺎﻋ نﺎــﻨﻔﻟا ﺎــﻬﻴﻠﻋ ﻞــﺼﺣ ﻞﻜــﺸﺑ ﺔﻴﻣﻼــﺳ ا ةرﺎﻤﻌﻟا ﺮﻳﻮﻄﺗ ةدﺎﻋإ ﻮﻫو ، " ﺔــﻴﻜﻧﺎﺧﺮﺼﻤﻟا " ﻰﻤــﺴﻤﻟا ﻪﻋوﺮــﺸﻣ ضﺮﻌﻤﻟا اﺬﻫ ضﺮــﻋ ﻢﺗو . ﺎﻬﺗﺎﺑاﻮﺑ ﻦــﻣ اءﺪﺑ ﺔﻠﻣﺎﻛ ﺔﻨﻳﺪﻤﻟ رﻮــﺼﺗ ﺎــﻌﺿاو ﻲــﺘﺤﻧ مﺎﻋ نﻮﻨﻔﻠﻟ ةﺮــﻳﺰﺠﻟا ﺰﻛﺮﻣ ﻢــﺛ ٢٠٠٦ مﺎﻋ ﺎﻣوﺮﺑ نﻮــﻨﻔﻠﻟ ﺔــﻳﺮﺼﻤﻟا ﺔــﻴﻤﻳدﺎﻛ ا ﻲــﻓ ﺎﻬﺗادﺮﻔﻣ ﻞــﻣﺎﻜﺑ " ﺔﻴﺘﺤﻨﻟا ﺔــﻨﻳﺪﻤﻟا " لﺎﻤﻜﺘــﺳﻻ ضوﺮﻌﻟا ﻚــﻟذ ﺪــﻌﺑ ﺖــﻌﺑﺎﺘﺗو ٢٠٠٨ ن ا ﻰﺘﺣ عوﺮــﺸﻤﻟا اﺬﻫ ﻰﻠﻋ ﻞــﻤﻌﻳ لازﻻو

eL SEED SECRETS OF TIME

The Great Pyramids of Giza are a symbol of permanence in a world where lives are short, a visual symbol of power in a world where power is transitory. For centuries, humankind has tried to explain the exact method used to build the Pyramids. It is still mysterious in these modern times of ours. Secrets of Time celebrates the greatness of the Pyramids of Giza and encompasses everything from the country’s ancient civilisation to a long list of Egyptian superlatives and achievements in culture, science, and more.

Inspired by the words of Egyptian novelist Radwa Ashour, time does not disclose its secrets to humankind. The sculpture’s striking colour will contrast with the monochrome beige of the Great Pyramids. The sculpture stands as an invitation to marvel at the Pyramids from a new singular point of view, while offering the viewers the opportunity to delve into an artwork that merges history, culture, and traditions.

FOREVER IS NOW .02 18

Metal 1 m x 6 m x 4 m 2022

تازﺎــﺠﻧ او قﻮﻔﺘﻟا ﻦﻣ ﺔــﻠﻳﻮﻃ ﺔﻤﺋﺎﻗ ﻰــﺘﺣو دﻼــﺒﻠﻟ ﺔــﻤﻳﺪﻘﻟا . ﺎﻫﺮﻴﻏو مﻮﻠﻌﻟاو ﺔــﻓﺎﻘﺜﻟا ﻲــﻓ ﻒــﺸﻜﻳ ﻻ ﻦﻣﺰﻟا " ،رﻮــﺷﺎﻋ ىﻮﺿر ﺔﻳﺮﺼﻤﻟا ﺔــﻴﺋاوﺮﻟا تﺎــﻤﻠﻛ ﺎﻤﻬﻠﺘــﺴﻣ يدﺎﺣ ا ﺞﻴﺒﻟا نﻮــﻟ ﻊﻣ ﺔﺑاﺬﺠﻟا ﺔﺗﻮﺤﻨﻤﻟا ناﻮــﻟأ ﻦــﻳﺎﺒﺘﺗ ، " ﺔﻳﺮــﺸﺒﻠﻟ هراﺮــﺳأ ﺰﻐﻟ ﻰﻠﻋ ةدﺎﻬــﺷ ﺔﺑﺎﺜﻤﺑ ﺔــﺗﻮﺤﻨﻤﻟا ﻒــﻘﺘﻓ ﺔــﻤﻴﻈﻌﻟا تﺎــﻣاﺮﻫ ﻟ ﺔﻄﻘﻧ ﻦﻣ ﺔــﺷﻮﺸﻣ ﺔﻳﺮﺼﺑ ﺔــﺑﺮﺠﺗ ﻦﻳﺪﻫﺎــﺸﻤﻟا ىﺮﻳ ﺎــﻤﻨﻴﺑ تﺎــﻣاﺮﻫ ا . ﺔﻨﻴﻌﻣ ﺔــﻳرﻮﺤﻣ

ART D’ÉGYPTE 19 ﻪﻴﻓ ةﺎﻴﺤﻟا ﻢــﻟﺎﻋ ﻲﻓ ءﺎﻘﺒﻠﻟ اﺰــﻣر ﺔﻤﻴﻈﻌﻟا ةﺰــﻴﺠﻟا تﺎــﻣاﺮﻫأ ﺮــﺒﺘﻌﺗ ﺖﻟوﺎﺣ . ﺔﺘﻗﺆﻣ ﻪــﻴﻓ ةﻮﻘﻟا ﻢﻟﺎﻋ ﻲــﻓ ةﻮﻘﻠﻟ ﻲﺋﺮﻣ ﺰــﻣرو ،ةﺮــﻴﺼﻗ ،تﺎﻣاﺮﻫ ا ءﺎﻨﺒﻟ مﺪﺨﺘــﺴﻤﻟا بﻮﻠــﺳﻻا ﻢﻬﻓ نوﺮﻗ ﺬــﻨﻣ ﺔﻳﺮــﺸﺒﻟا " ﻦﻣﺰﻟا راﺮــﺳأ " ﻞﻔﺘﺤﻳ ﺚﻳﺪﺤﻟا ﺎــﻧﺮﺼﻋ ﻰﺘﺣ ﺎﻀﻣﺎﻏ لاﺰــﻳ ﻻ ﺮــﻣ ا ﻦــﻜﻟو

ﻦﻣ اءﺪــﺑ ءﻲــﺷ ﻞﻛ ﻞﻤــﺸﻳو

تﺎﻣاﺮﻫأ

ﺪﻴـــﺳ لا ﻦــﻣﺰـﻟا راﺮــــﺳأ نﺪﻌﻣ م٤ ×

×

٢٠٢٢

ةرﺎﻀﺤﻟا

،ةﺰﻴﺠﻟا

ﺔــﻤﻈﻌﺑ ﺔﻳﺮﺼﻤﻟا

م٦

م١

eL SEED SECRETS OF TIME

Photo: MO4 Network

Photo: MO4 Network

ﺪﻴـــﺳ لا ﻦــﻣﺰـﻟا راﺮــﺳأ

eL Seed is a contemporary artist whose practice crosses the disciplines of painting and sculpture. He uses the wisdom of writers, poet, and philosophers from around the world to convey messages of peace and to underline the commonalities of human existence. eL Seed uses his art as an echo of the stories of the communities that he meets around the world and aims to amplify their voices. He considers his artwork a way to build links between peoples around the world. Whenever he works within a community, he spends a long time to learn and be inspired by its members, researching to fnd the best art installation to summarise the voice of the community he is working within and to underline his key principals of love, respect, and tolerance.

His work has been shown in exhibitions and public places all over the world including most notably on the facade of L'institut du monde Arabe in Paris, in the favelas of Rio de Janeiro, on the DMZ between North and South Korea, in the slums of Cape Town, and in the heart of Cairo's garbage collectors’ neighbourhood. In 2021, eL Seed was selected by the World Economic Forum as one of the Young Global Leaders for his vision and infuence to drive positive change in the world. In 2019, he won ‘The international award for public art’ for Perception, his project in Cairo. In 2017, he won the UNESCO Sharjah Prize for Arab Culture and was named a Global Thinker in 2016 by Foreign Policy magazine, also for Perception . In 2015, he was recognised as one of the year’s TED Fellows for advocating peaceful expression and social progress through his work. He has also collaborated with Louis Vuitton on their famous Foulard d’artistes .

FOREVER IS NOW .02 22

ﻮﻬﻓ ،ﺖﺤﻨﻟاو ﻢــﺳﺮﻟا تﻻﺎﺠﻣ ﻪﺗﺎــﺳرﺎﻤﻣ ﻰﻄﺨﺘﺗ ﺮــﺻﺎﻌﻣ نﺎــﻨﻔﻛ ( ﺪﻴــﺳ لا ) ﻦﻣ ﻞﻘﻨﻴﻟ ﻢــﻟﺎﻌﻟا ءﺎﺤﻧإ ﻦــﻣ ﺔﻔــﺳﻼﻔﻟاو ءاﺮﻌــﺸﻟاو بﺎﺘﻜﻟا ﺔــﻤﻜﺤﺑ ﻦﻴﻌﺘــﺴﻳ يﺮــﺸﺒﻟا دﻮﺟﻮﻠﻟ ﺔﻛﺮﺘــﺸﻤﻟا ﻢــﺳاﻮﻘﻟا ﻰﻠﻋ اﺪﻛﺆﻣ مﻼــﺳ ﻞﺋﺎــﺳر ﺎﻬﻟﻼﺧ ءﺎﺤﻧأ ﻲﻓ ﺔﻔﻠﺘﺨﻣ تﺎــﻌﻤﺘﺠﻣ ﻦــﻣ تﺎﻳﺎﻜﺤﻟ ىﺪــﺼﻛ ﻪــﻨﻓ ( ﺪﻴــﺳ لا ) مﺪﺨﺘــﺴﻳ ﺔﻴﻨﻔﻟا ﻪــﻟﺎﻤﻋأ ﺮﺒﺘﻌﻳ ﺎــﻤﻛ ،ﺎﻬﺗاﻮﺻأ ﺰﻳﺰﻌﺗ ﻰــﻟإ فﺪﻬﻳو ﺎــﻬﻴﻟإ ﻊﻤﺘــﺴﻳ ﻲــﺘﻟاو ﻢــﻟﺎﻌﻟا ﻢﻟﺎﻌﻟا بﻮﻌــﺷ ﻦﻴﺑ ﺔﻛﺮﺘــﺸﻣ تﺎﻗﻼﻋ ءﺎﻨﺒﻟ ﺔﻠﻴــﺳو ﻊﻤﺘﺠﻤﻟا داﺮــﻓأ ﻦﻣ مﺎﻬﻟ ا ﻰﻠﻋ لﻮــﺼﺤﻟاو ﻢﻠﻌﺘﻟا ﻲــﻓ ﻼﻳﻮﻃ ﺎــﺘﻗو ﻲــﻀﻘﻳ ﻮــﻫ غاﺮﻔﻟا ﻲﻓ ﻲﻨﻓ ﺰــﻴﻬﺠﺗ ﻞﻀﻓأ ﻦــﻋ ﺚﺤﺒﻟﺎﺑ مﻮﻘﻳو ،ﻪــﻠﻤﻋ

،وﺮــﻴﻧﺎﺟ مﺎﻋ ﻲﻓ ةﺮﻫﺎﻘﻟﺎﺑ ﺔــﻣﺎﻤﻘﻟا ﻲــﻌﻣﺎﺟ ﻲﺣ ﺐﻠﻗ ﻲﻓو ،نوﺎــﺗ ﺐــﻴﻜﺑ ةﺮــﻴﻘﻔﻟا ةدﺎﻘﻟا ﺪﺣﺄﻛ ﻲــﻤﻟﺎﻌﻟا يدﺎﺼﺘﻗﻻا ىﺪــﺘﻨﻤﻟا ﻞﺒﻗ ﻦــﻣ ( ﺪﻴــﺳ لا ) رﺎﻴﺘﺧا ﻢــﺗ ،٢٠٢١ . ﻢﻟﺎﻌﻟا ﻲﻓ ﻲــﺑﺎﺠﻳإ ﺮﻴﻴﻐﺗ ثاﺪــﺣإ ﻰﻠﻋ ﻪﺗرﺪﻗو ﻪﺘﻳؤر ﻰــﻠﻋ اءﺎــﻨﺑ ،بﺎﺒــﺸﻠﻟ ﻦــﻴﻴﻟوﺪﻟا " ﺔﺣﻮﺘﻔﻤﻟا ﻦــﻛﺎﻣ ا ﻲﻓ نﻮﻨﻔﻠﻟ ﺔــﻴﻟوﺪﻟا ةﺰﺋﺎﺠﻟا " ﻰــﻠﻋ ،٢٠١٩ مﺎﻋ ﻞــﺼﺣ ﺎــﻤﻛ ةﺰﺋﺎﺟ ﻰﻠﻋ ﻞــﺼﺣ ﺪﻘﻓ ،٢٠١٧ مﺎﻋ ﻲﻓ ﺎــﻣأ ." كاردإ " ةﺮﻫﺎﻘﻟا ﻲــﻓ ﻪﻋوﺮــﺸﻣ ﻦــﻋ مﺎﻋ ﻲﻓ ﻲﻟود ﺮﻜﻔﻣ ﺐــﻘﻟ ﻰﻠﻋ ﻞــﺼﺣو ﺔــﻴﺑﺮﻌﻟا ﺔــﻓﺎﻘﺜﻠﻟ ﺔﻗرﺎــﺸﻟا / ﻮﻜــﺴﻧﻮﻴﻟا عوﺮــﺸﻣ ﻦﻋ ﺎﻀﻳأ ( ﺔﻴﺟرﺎﺨﻟا ﺔــﺳﺎﻴﺴﻟا ) " ﻲــﺴﻴﻟﻮﺑ ﻦﻳرﻮﻓ " ﺔﻠﺠﻣ ﻞــﺒﻗ ﻦــﻣ ٢٠١٦ ﻪﺗﺮﺼﻨﻟ مﺎــﻌﻟا ﻚﻟﺬﻟ TED ءﻼﻣز ﺪﺣﺄﻛ ﻪــﺑ فاﺮﺘﻋﻻا ﻢﺗ ،٢٠١٥ مﺎــﻋ ﻲــﻓ ." كاردإ "

Sponsored by and

ART D’ÉGYPTE 23

ﻪﻴﻓ سرﺎــﻤﻳ يﺬــﻟا ﻪﺋدﺎﺒﻣ ﻰﻠﻋ ﺪــﻴﻛﺄﺘﻠﻟو

ﻲﻓ ﻊﻤﺘﺠﻤﻟا ﻚــﻟذ تﻮﺻ جﺎــﻣدﻻ ( ﻦــﺸﻴﻠﺘﺴﻧا ) . ﺢﻣﺎــﺴﺘﻟاو ماﺮﺘﺣﻻاو ﺐﺤﻟا ﻦﻣ ﺔﻴــﺴﻴﺋﺮﻟا ،ﺎﻫزﺮﺑأو ،ﻢﻟﺎﻌﻟا ءﺎــﺤﻧأ ﻊﻴﻤﺟ ﻲــﻓ ﺔﻣﺎﻋ ﻦﻛﺎﻣأو ضرﺎﻌﻣ ﻲــﻓ ﻪﻟﺎﻤﻋأ ضﺮــﻋ ﻢــﺗ يد ﻮﻳر ﻦﻣ ةﺮﻴﻘﻔﻟا ءﺎــﻴﺣ او ،ﺲﻳرﺎﺑ ﻲــﻓ ﻲﺑﺮﻌﻟا ﻢﻟﺎﻌﻟا ﺪــﻬﻌﻣ ﺔــﻬﺟاو ﻰــﻠﻋ ءﺎﻴﺣ او ،ﺔﻴﺑﻮﻨﺠﻟاو ﺔﻴﻟﺎﻤــﺸﻟا ﺎــﻳرﻮﻛ ﻦﻴﺑ حﻼــﺴﻟا ﺔﻋوﺰﻨﻤﻟا ﺔــﻘﻄﻨﻤﻟاو

يﻮﻟ

رﻮــﻄﺘﻟاو ﻲﻤﻠــﺴﻟا ﺮــﻴﺒﻌﺘﻠﻟ ." ﻦﻴﻧﺎﻨﻔﻟا ﺔﺤــﺷوأ " ﺮﻴﻬــﺸﻟا ﻢﻬﻋوﺮــﺸﻣ ﻲﻓ " نﻮﺘﻴﻓ ﺔﻳﺎﻋﺮﺑ

،ﻪــﻠﻤﻋ

" ﻊﻣ ﺎﻀﻳأ نوﺎــﻌﺗ ﺎﻤﻛ . ﻪﻠﻤﻋ لﻼــﺧ ﻦﻣ ﻲــﻋﺎﻤﺘﺟﻻا

EMILIO FERRO PORTAL OF LIGHT

Corten steel

Structure 1: 0.65 m x 0.65 m x 2.60 m

Structure 2: 1.46 m x 0.40 m x 2.85 m

B ases: variable dimensions 2022

The site-specifc installation Portal of Light by Emilio Ferro explores the imagery of ancient Egypt, contemplating the themes of threshold—as a bridge between the world of the living and the dead—and of light as it relates to the sun worship deities such as Isis and Ra. Inspired by two ancient papyri, the Book of the Dead and the Amduat (also known as the Book of the Hidden Chamber ), Portal of Light follows the orientation of the cardinal points and the transformation of sunlight during the day.

Two metal sculptures generate and expand a beam of light, following the perfect inclination of the three Pyramids of Giza. During the night, spectators can enter the installation under the beam of light and follow its direction, taking part in an immersive adventure to experience the journey into the night sky on the boat of the god Ra, as illustrated in the ancient papyri.

FOREVER IS NOW .02 24

وﺮــﻴﻓ ﻮــﻴﻠﻴﻣإ ﺚﻴﺣ ﻦﻣ رﻮﻨﻟاو ،تاﻮــﻣ او ءﺎﻴﺣ ا ﻢﻟﺎﻋ ﻦــﻴﺑ ﻂﺑﺮﺗ رﻮــﺴﺠﻛ تﺎﺒﺘﻌﻟا ،ﻪــﻟﻼﺧ ﻦــﻣ ﻦﻴﺘﻳدﺮﺑ ﻦــﻣ ﻞﻤﻌﻟا ﻢﻬﻠﺘــﺴﻳ . عرو ﺲﻳﺰﻳإ ﻞﺜﻣ ﺲﻤــﺸﻟا ﺔــﻬﻟآ ةدﺎــﺒﻌﺑ ﻪــﺘﻠﺻ بﺎﺘﻛ " ﻢــﺳﺎﺑ ﺎﻀﻳأ فوﺮﻌﻤﻟا تاود ﻲﻣ ا بﺎــﺘﻛو ﻰﺗﻮﻤﻟا بﺎــﺘﻛ ،ﺎــﻤﻫو ،ﻦــﻴﺘﻤﻳﺪﻗ ءﻮﺿ تﻻﻮﺤﺗو ﺔﻌﺑر ا تﺎــﻬﺠﻟا ﻊﻗاﻮﻣ رﻮــﻨﻟا ﺔﺑاﻮﺑ ﻊﺒﺘﺘﻳ ﺚــﻴﺣ ، " ﺔــﻴﻔﺨﻟا ﺔــﻓﺮﻐﻟا رﺎﻬﻨﻟا لﻼﺧ ﺲﻤــﺸﻟا ﻞﺜﻣ ا ﻞﻴﻤﻟا ﻊــﺒﺘﺘﻟ ءﻮﻀﻟا ﻦــﻣ ﺎﻋﺎﻌــﺷ ﺮﻴﺒﻜﺗو ﺪــﻴﻟﻮﺘﺑ نﺎــﺘﻴﻧﺪﻌﻣ نﺎــﺘﺗﻮﺤﻨﻣ مﻮــﻘﺗ ﻰﻟإ لﻮﺧﺪﻟا ﻦﻣ ،ﻞــﻴﻠﻟا لﻼﺧ ،ﻦﻳﺪﻫﺎــﺸﻤﻟا ﻦﻜﻤﺘﻳ ﺔــﺛﻼﺜﻟا ةﺰــﻴﺠﻟا تﺎــﻣاﺮﻫ ةﺮﻣﺎﻐﻣ ﻲﻓ ﺔﻛرﺎــﺸﻤﻟاو ﻪﻫﺎﺠﺗا ﺔــﻌﺑﺎﺘﻣو ءﻮﻀﻟا عﺎﻌــﺷ ﺖــﺤﺗ ﻦــﺸﻴﻠﺘﺴﻧﻻا

ART D’ÉGYPTE 25 ﻪﻤﻤﺻ يﺬﻟا ( ﻦــﺸﻴﻠﺘﺴﻧﻻا ) غاﺮــﻔﻟا ﻲﻓ ﺰﻴﻬﺠﺘﻟا ﻮــﻫو ، " رﻮﻨﻟا ﺔــﺑاﻮﺑ " ﻒــﺸﻜﺘﺴﻳ ﻼﻣﺄﺘﻣ ،ﺔﻤﻳﺪﻘﻟا ﺮــﺼﻤﻟ ﺔــﻳزﺎﺠﻤﻟا رﻮﺼﻟا ،ﻊﻗﻮﻤﻟا ﻊــﻣ ﻢﻏﺎﻨﺘﻣ ﻞﻜــﺸﺑ

ﻦﺘﻣ ﻰﻠﻋ ﻼﻴﻟ ءﺎﻤــﺴﻟا ﻰﻟإ ﺔــﻠﺣﺮﻟا ﺔــﺑﺮﺠﺗ ضﻮــﺨﻟ

ﺔﻤﻳﺪﻘﻟا تﺎــﻳدﺮﺒﻟا ﻲﻓ ﺢــﺿﻮﻣ وﺮـﻴــﻓ ﻮــــﻴﻠــﻴﻣإ رﻮــﻨﻟا ﺔــــﺑاﻮــﺑ " ﻦﺗرﻮﻛ " ﺐﻠﺻ م٢،٦٠ × م٠،٦٥ × م٠،٦٥ :١ نﺎــﻴﻜﻟا م٢،٨٥ × م٠،٤٠ × م١،٤٦ :٢ نﺎــﻴﻜﻟا ﺔﻔﻠﺘﺨﻣ تﺎــﺳﺎﻘﻣ : ﺪﻋاﻮﻘﻟا ٢٠٢٢

ﻮﻫ ﺎﻤﻛ ،عر ﻪﻟ ا برﺎــﻗ

ةﺮــﻣﺎﻏ

EMILIO FERRO

PO RTA L OF LI G HT

Photo: Roberto Conte

Photo: Roberto Conte

وﺮـﻴــﻓ ﻮــــﻴﻠــﻴﻣإ رﻮــﻨﻟا ﺔــــﺑاﻮــﺑ

Emilio Ferro is an Italian artist whose works investigate the perception of light and space through museum installations and projects designed for natural environments. In 2010, after completing the three-year course in design at IED in Turin, he moved to Berlin to complete his education and started working with MANASAS, supervising and collaborating on over 500 architectural lighting projects in Italy and abroad. In the following years, Ferro's work evolved from design to the realisation of light art installations. In 2019, Ferro was the artist chosen to create the frst chapter of Fondazione Radical Design, an artistic institution created by Charley Vezza and Sandra Vezza, owners of the Gufram and Memphis Milano brands. In 2020, he joined the artists of Studio Studio Studio, the artistic collective created by Edoardo Tresoldi. In 2022, Ferro was commissioned to create Segreto Cardiopulso , the installation for the inauguration of the centenary dedicated to the famous Italian writer Beppe Fenoglio. For several years, he has been pursuing his own independent poetics that feed an artistic language capable of blending light, sound, and visual arts, in the conviction that only the totalizing experience of art can make us understand the profound beauty of nature. By distorting reality through artistic intervention, the artist shares with the viewer what is out of the ordinary.

FOREVER IS NOW .02 28

لﻼﺧ ﻦﻣ غاﺮﻔﻟاو ءﻮــﻀﻟا مﻮﻬﻔﻣ ﻪﻟﺎﻤﻋأ ﺚــﺤﺒﺗ ﻲﻟﺎﻄﻳإ نﺎــﻨﻓ وﺮــﻴﻓ ﻮــﻴﻠﻴﻣإ

مﺎﻋ ﻲﻓ ﺔﻴﻌﻴﺒﻄﻟا تﺎــﺌﻴﺒﻠﻟ ﺔــﻤﻤﺼﻣ ﻊﻳرﺎــﺸﻣو ( ﻦــﺸﻴﻠﺘﺴﻧا ) غاﺮﻔﻟا ﻲــﻓ تاﺰــﻴﻬﺠﺗ ﻲﺑورو ا ﺪﻬﻌﻤﻟا ﻲــﻓ تاﻮﻨــﺳ ثﻼﺛ ةﺪﻤﻟ ﻢﻴﻤﺼﺘﻟا ﺔــﺳارد ﻦﻣ ﻪــﺋﺎﻬﺘﻧا ﺪــﻌﺑو ،٢٠١٠ " ﻲﻓ ﻞﻤﻌﻳ اﺪــﺑ ﻢﺛ ﻪﺘــﺳارد ﻞﻤﻜﻴﻟ ﻦﻴﻟﺮﺑ ﻰﻟإ ﻞﻘﺘﻧا ،ﻦــﻳرﻮﺗ ﺔــﻨﻳﺪﻣ ﻲــﻓ ﻢــﻴﻤﺼﺘﻠﻟ ﺎﻴﻟﺎﻄﻳإ ﻲــﻓ ﺔﻳرﺎﻤﻌﻣ ةءﺎﺿإ عوﺮــﺸﻣ ٥٠٠ ﻦﻣ ﺮﺜﻛأ ﻰﻠﻋ فﺮــﺷأ ﺚــﻴﺣ “ سﺎــﺳﺎﻧﺎﻣ ﻰﻟإ ﻢﻴﻤﺼﺘﻟا ﻦــﻣ ﺔﻴﻟﺎﺘﻟا تاﻮﻨــﺴﻟا ﻲﻓ ترﻮﻄﺗو وﺮــﻴﻓ لﺎﻤﻋأ

." ﻮﻴﻟﻮﻨﻴﻓ ﻪــﻴﺒﻴﺑ " ﺮﻴﻬــﺸﻟا ﻲﻟﺎﻄﻳ ا ﺐﺗﺎﻜﻠﻟ ﺔــﻳﻮﺌﻤﻟا ىﺮــﻛﺬﻟا حﺎــﺘﺘﻓﻻ ، ( ﻦــﺸﻴﻠﺘﺴﻧا ) ﺔﻐﻟ تﺬﻏ ﻲﺘﻟا ﺔﻠﻘﺘــﺴﻤﻟا ﺔﻳﺮﻌــﺸﻟا ﻪــﺴﻴﺳﺎﺣﺄﺑ مﺎﻤﺘﻫﻻا ،تاﻮﻨــﺳ ةﺪﻌﻟ ﻞــﺻاو ﺔﺑﺮﺠﺘﻟا نأ ﺔــﻋﺎﻨﻗ ﻼﻣﺎﺣ ،ﺔﻴﺋﺮﻤﻟا نﻮــﻨﻔﻟاو تﻮﺼﻟاو ءﻮــﻀﻟا جﺰﻣ ﻰــﻠﻋ ةردﺎــﻗ ﺔــﻴﻨﻓ . ﺔﻌﻴﺒﻄﻠﻟ ﻖــﻴﻤﻌﻟا لﺎــﻤﺠﻟا ﻢﻬﻔﻧ ﺎﻨﻠﻌﺠﺗ نأ ﻦــﻜﻤﻳ ﻲــﺘﻟا ﻲﻫ ﻂــﻘﻓ ﻦــﻔﻠﻟ ﺔــﻴﻠﻜﻟا ﻦﻋ جرﺎﺧ ﻮﻫ ﺎﻣ ﻞﻛ ،ﻊــﻗاﻮﻟا ﻒﻳﺮﺤﺗ لﻼــﺧ ﻦﻣ ،جﺮﻔﺘﻤﻟا ﻊــﻣ نﺎــﻨﻔﻟا ﻢــﺳﺎﻘﺘﻳو ﻲﻨﻔﻟا ﻞﺧﺪﺘﻟا ﻖــﻳﺮﻃ ﻦﻋ فﻮــﻟﺄﻤﻟا

Represented by ﻪﻠﺜﻤﻳ نﺎﻨﻔﻟا

ART D’ÉGYPTE 29

ﺖــﻤﻧ جرﺎــﺨﻟاو غاﺮﻔﻟا ﻲﻓ ﺔــﻴﺋﻮﻀﻟا تاﺰــﻴﻬﺠﺘﻟا ﻢﻴﻤﺼﺘﻟا ﺔــﺴﺳﺆﻣ " ﻦﻣ لو ا عﺮﻔﻟا ءﺎــﺸﻧ وﺮﻴﻓ رﺎﻴﺘﺧا ﻢــﺗ ،٢٠١٩ مﺎــﻋ ﻲــﻓ بﺎﺤﺻأ ،اﺰﻴﻓ ارﺪﻧﺎــﺳو اﺰﻴﻓ ﻲﻟرﺎــﺸﺗ ﺎﻫﺄــﺸﻧأ ﺔﻴﻨﻓ ﺔــﺴﺳﺆﻣ ﻲﻫو ، " ﺔﻴﻟﺎﻜﻳداﺮﻟا ﻮﻳﺪﺘــﺳ " ﻲﻧﺎﻨﻓ ﻰﻟإ ﻢﻀﻧا ." ﻮﻧﻼﻴﻣ ﺲــﻴﻔﻤﻣ " و " ماﺮــﻔﺟ " ﻦــﻴﺘﻳرﺎﺠﺘﻟا ﻦــﻴﺘﻣﻼﻌﻟا ﻢﺗ يﺪﻟﻮــﺴﻳﺮﺗ ودراودإ ﺎﻬﻧ ّ ﻮﻛ ﺔﻴﻨﻓ ﺔــﻋﻮﻤﺠﻣ ﻲﻫو ،٢٠٢٠ مﺎــﻋ " ﻮﻳﺪﺘــﺳ ﻮﻳﺪﺘــﺳ غاﺮﻔﻟا ﻲﻓ ﺰﻴﻬﺠﺗ ﻮــﻫو ، " يﺮــﺴﻟا ﺐﻠﻘﻟا ﺾﺒﻧ " ءﺎــﺸﻧﺈﺑ ،٢٠٢٢ مﺎﻋ وﺮــﻴﻓ ﻒــﻴﻠﻜﺗ

JWAN YOSEF VITAL SANDS

Galala limestone

Structure 1: 2.50 m x 1.51 m x 1.40 m

Structure 2: 1.28 m x 2.46 m x 1.02 m

Structure 3: 1.43 m x 2.70 m x 1.27 m

2022

Jwan Yosef's site-specific contribution to Forever Is Now .02 considers the ancient pyramids’ role as conduits to eternity and the everyday wonders of the preserving nature of the environment. Yosef sees the Sahara's terrain as far from barren and focuses on the desert as a source of vitality, acknowledging its part in conserving Egypt's history. Additional inspiration is taken from the fluidity of the sands' shape-shifting capacities, including the ecological marvel of its traveling dust, where its fertile minerals are known to cross land and sea to give sustenance to the Amazon Rainforest.

In Vital Sands , Yosef immerses sculpted aspects of his self-portrait in the remedial sands of time. While the sand and scale poetically abstract the figure, one is left to imagine what rests beneath. The installation presents a different angle from traditional self-portraiture. The abstraction de-centralises the form from hierarchy and recognition, pushing the genre to function as a call for self-reflection and self-care. While the pyramids, in the distance, point to the sky, Vital Sands is a grounding moment for monumental intimacy, welcoming viewers to reflect from within, meditating on the individual's role of care for self, humanity, and nature.

The artist would like to thank and give special recognition to patrons Alberto de la Cruz and Armando Gutierrez for their support and also acknowledge Brianna Bakke, Bruno del Granado, M ARMONIL , and the Embassy of Sweden in Cairo for their agency in the realisation of the project.

FOREVER IS NOW .02

30

ةﺪﻴﻌﺑ ءاﺮــﺤﺼﻟا ﺲﻳرﺎﻀﺗ نأ ﻒــﺳﻮﻳ ىﺮﻳ ﺔﺌﻴﺒﻟا ﺔــﻌﻴﺒﻃ ﻰــﻠﻋ ﻆــﻓﺎﺤﺗ ﻲــﺘﻟا ظﺎﻔﺤﻟا ﻲﻓ ﺎــﻫروﺪﺑ فﺮﺘﻌﻳو ،ﺎﻳﻮﻴﺣ ارﺪــﺼﻣ ﺎﻫﺪﺠﻳ ﻞــﺑ ،ﺔﻠﺣﺎﻗ ﺎــﻬﻧﻮﻛ ﻦــﻋ ﺪــﻌﺒﻟا ﺮﻴﻴﻐﺗ ﻰــﻠﻋ ﺎﻬﺗرﺪﻗو لﺎﻣﺮﻟا ﺔﻴﺑﺎﻴــﺴﻧا ﻦﻣ ﻲــﻓﺎﺿإ مﺎﻬﻟإ ﺪﻤﺘــﺴﻳ . ﺮﺼﻣ ﺦــﻳرﺎﺗ ﻰــﻠﻋ ﻰﻠﻋ يﻮﺘﺤﻳ يﺬــﻟا ﺎﻫرﺎﺒﻏ لﺎﻘﺘﻧا ﻲــﻓ ﺔﻴﺌﻴﺒﻟا ﺔــﺑﻮﺠﻋ ا ﻚﻟذ ﻲــﻓ ﺎــﻤﺑ ،ﺎﻬﻠﻜــﺷ ﺎﻬﻤﻋﺪﺗو ةﺮــﻴﻄﻤﻟا نوزﺎﻣ ا تﺎﺑﺎﻏ ﻰــﻟإ ﻞﺼﺘﻟ ﺮﺤﺒﻟاو ﺔــﺴﺑﺎﻴﻟا ﺮــﺒﻋ ﺔــﺒﺼﺧ ندﺎــﻌﻣ ﺔﻳﺬﻐﻤﻟا ﺮــﺻﺎﻨﻌﻟﺎﺑ ( ﻪﻳﺮﺗرﻮﺑ ) ﺔﻴﺗاﺬﻟا ﻪــﺗرﻮﺻ ﻦﻣ ﺔﺗﻮﺤﻨﻣ ﺐــﻧاﻮﺟ ﻒــﺳﻮﻳ ﺮﻤﻐﻳ ، " ﺔﻳﻮﻴﺤﻟا لﺎــﻣﺮﻟا " ﻲــﻓ ﻞﻜــﺸﺑ ﻦﻳﻮﻜﺘﻟا ﻚﻟذ ﺪﻳﺮﺠﺘﻳ ﻞــﻣﺮﻟا مﻮﻘﻳ ﺎﻤﻨﻴﺑو . ﺔﻴﻓﺎــﺸﻟا ﻦــﻣﺰﻟا لﺎــﻣر ﻲــﻓ ﺔﻳواز ( ﻦــﺸﻴﻠﺘﺴﻧﻻا ) ﻞﻤﻌﻟا مﺪــﻘﻳ . ﻪﺘﺤﺗ ﺪﻗﺮﻳ يﺬــﻟا ﺎﻣ ﻞﻴﺨﺘﻴﻟ ءﺮــﻤﻟا كﺮــﺘﻳ ،يﺮﻌــﺷ ﻞﻜــﺸﻟا ﻚﻴﻜﻔﺘﺑ ﺪﻳﺮﺠﺘﻟا مﻮــﻘﻳ ﺚﻴﺣ ،يﺪﻴﻠﻘﺘﻟا

ART D’ÉGYPTE 31 ﻊﻣ ﻢﻏﺎﻨﺗ ﻲــﻓ ﺔﻣﺎﻘﻣ "٢ ن ا ﻮﻫ ﺪﺑ ا " ﻲــﻓ ﻒــﺳﻮﻳ ناﻮﺟ ﺔﻤﻫﺎــﺴﻣ ﺮــﺒﺘﻌﺗ ﺔﻴﻣﻮﻴﻟا ةﺎــﻴﺤﻟا تاﺰﺠﻌﻣو دﻮــﻠﺨﻠﻟ تاﻮﻨﻘﻛ تﺎــﻣاﺮﻫ ا رود زﺮﺒﺗ ﺚــﻴﺣ ،ﻊــﻗﻮﻤﻟا ﻞﻛ

ﻲــﺗاﺬﻟا ﺮــﻳﻮﺼﺘﻟا ﻦــﻋ ﺔــﻔﻠﺘﺨﻣ تاﺬﻟﺎﺑ ﺔﻳﺎﻨﻌﻟاو ﻞــﻣﺄﺘﻠﻟ يﺮــﺸﺒﻟا عﻮﻨﻟا ﻊﻓﺪﻳو ،كارد او ﺔــﻴﻣﺮﻬﻟا ﺔــﻴﻠﻜﻴﻬﻟا ﻦــﻣ ﻞﺜﻤﺗ " ﺔﻳﻮﻴﺤﻟا لﺎــﻣﺮﻟا " نﺈﻓ ،ءﺎﻤــﺴﻟا ﻰﻟإ ةﺮﻴــﺸﻣ ﻖﻓ ا ﻲﻓ تﺎــﻣاﺮﻫ ا ﻒــﻘﺗ ﺎــﻤﻨﻴﺑو ﻞﻣﺄﺘﻟاو ،ﻖﻤﻌﺑ ﺮــﻴﻜﻔﺘﻠﻟ ﻦﻳﺪﻫﺎــﺸﻤﻟﺎﺑ ﺐــﻴﺣﺮﺘﻟاو ﺔﻔﻟ ا ﺦﻴــﺳﺮﺗ ﻦﻣ ﺔــﻤﻬﻣ ﺔــﻈﺤﻟ . ﺔﻌﻴﺒﻄﻟﺎﺑو ،ﺔﻴﻧﺎــﺴﻧ ﺎﺑو ،تاﺬــﻟﺎﺑ مﺎﻤﺘﻫﻻا ﺚﻴﺣ ﻦــﻣ دﺮﻔﻟا رود ﻲــﻓ زوﺮــﻛ ﻻ يد ﻮــﺗﺮﺒﻟأ ةﺎــﻋﺮﻟا ﻰــﻟإ صﺎــﺨﻟا ﺮــﻳﺪﻘﺘﻟاو ﺮﻜــﺸﻟﺎﺑ مﺪــﻘﺘﻳ نأ نﺎــﻨﻔﻟا دﻮــﻳ ،ودﺎــﻧاﺮﺟ ﻞــﻳد ﻮــﻧوﺮﺑو كﺎــﺑ ﺎــﻧﺎﻳﺮﺑ ﺮﻜــﺷ ﺎــﻀﻳأو ﻢــﻬﻤﻋد ﻰــﻠﻋ ﺰــﻳﺮﻴﺗﻮﺟ وﺪــﻧﺎﻣرأو ﻲــﻓ ﻢﻬﺗﺪﻋﺎــﺴﻣ ﻰــﻠﻋ ةﺮــﻫﺎﻘﻟا ﻲــﻓ ﺪﻳﻮــﺴﻟا ةرﺎﻔــﺳو ،ﻞــﻴﻧﻮﻣرﺎﻣ ﺔﻛﺮــﺷو . عوﺮــﺸﻤﻟا ﻖــﻴﻘﺤﺗ ﻒﺳﻮــﻳ ناﻮــﺟ ﺔــﻳﻮــﻴﺤﻟا لﺎــــﻣﺮﻟا ﺔﻟﻼﺠﻟا يﺮﻴﺟ ﺮــﺠﺣ م١،٤٠ × م١،٥١ × م٢،٥ :١ نﺎــﻴﻜﻟا م١،٠٢ × م٢،٤٦ × م١،٢٨ :٢ نﺎــﻴﻜﻟا م١،٢٧ × م٢،٧٠ × م١،٤٣ :٣ نﺎــﻴﻜﻟا ٢٠٢٢

JWAN YOSEF

V ITA L S A NDS

??????????

Photo:

ﻒﺳﻮــﻳ ناﻮــﺟ ﺔــﻳﻮــﻴﺤﻟا لﺎــــﻣﺮﻟا

Jwan Yosef is a Syrian-born, Swedish-patriated conceptual artist living and working in Los Angeles, California. Yosef’s practice employs a deconstructive modality of rethinking materials, histories, languages, and images to poetically interpret ever-expanding meanings of identity and belonging engendered in art. His examination of the many power constructs behind representational imagery spans from the nostalgic qualities of old family photos to posed publicity images of historical fgures. The ubiquity of images and their hidden agendas and signifers are vital concepts in today’s culture of mediated images. Yosef’s tactical use of abstraction serves opportunities to release entendres and challenge viewers to break from passive gazes towards a plurality of perspectives.

Yosef holds a MFA from Central Saint Martins, London and a BFA from Konstfack, Stockholm. Notable exhibitions include solo presentations at Praz-Delavallade, Los Angeles, CA; Basilica Santa Maria, Rome; The Goss-Michael Foundation, Dallas, TX; Stene Projects, Stockholm; Divus Gallery, London; as well as group presentations with Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris; White Cube, Paris; the Institute of Arab and Islamic Art, New York; Kamarade, Stockholm; Hartslane, London; De Markten, Brussels; and UMELEC, Prague/Vienna, amongst others. He has been awarded the Beers Contemporary Award for Emerging Art and the Threadneedle Prize and is included in the public collections of Karolinska, Solna and Stockholm’s Kulturforvaltning, both in Sweden.

FOREVER IS NOW .02 34

ﻞﻤﻌﻳو ﺶﻴﻌﻳ ،ﺔﻴــﺴﻨﺠﻟا يﺪﻳﻮــﺳو ،ﺪﻟﻮﻤﻟا يرﻮــﺳ ﻲﻤﻴﻫﺎﻔﻣ نﺎﻨﻓ ﻒــﺳﻮﻳ ناﻮﺟ ﺔﺻﺎﺧ ﺔﻴﻜﻴﻜﻔﺗ ﺔــﻐﻴﺻ ﻒــﺳﻮﻳ لﺎﻤﻋأ ﻰﻨﺒﺘﺗ ﺎﻴﻧرﻮﻔﻴﻟﺎﻛ ،سﻮــﻠﺠﻧأ سﻮﻟ ﻲــﻓ يﺮﻋﺎــﺷ ﻞﻜــﺸﺑ ﺮــﺴﻔﻴﻟ رﻮﺼﻟاو تﺎﻐﻠﻟاو ﺦﻳرﺎﺘﻟاو ةدﺎﻤﻟا ﻲﻓ ﺮﻴﻜﻔﺘﻟا ةدﺎﻋﺈﺑ ﺺﺤﻔﺘﻳ . ﻦﻔﻟا ﻲــﻓ ءﺎﻤﺘﻧﻻاو ﺔﻳﻮﻬﻠﻟ ﺖﺛﺪﺣ ﻲــﺘﻟا ﺔﻌــﺴﺘﻤﻟاو ةﺪﻳاﺰﺘﻤﻟا ﻲــﻧﺎﻌﻤﻟا ﻲﻓ ﺔﻠﺜﻤﺘﻤﻟا ﺔــﻴﻟﺎﻴﺨﻟا دﺎﻌﺑ ا ﻒﻠﺧ ﺔــﻨﻣﺎﻜﻟا ةﻮﻄــﺴﻟا تﺎﺒﻴﻛﺮﺗ ﻦﻣ ﺪــﻳﺪﻌﻟا ﻒــﺳﻮﻳ ﺔﻳﺎﻋﺪﻟا رﻮﺻ ﺔﻬﺟاﻮﻣ ﻲــﻓ ﺔﻤﻳﺪﻘﻟا ﺔﻴﻠﺋﺎﻌﻟا رﻮــﺼﻠﻟ ﻦﻴﻨﺤﻟﺎﺑ ةءﻮــﻠﻤﻤﻟا تﺎﻤــﺴﻟا ﺎﻬﺗﻻﻻدو نﺎﻜﻣ ﻞﻛ ﻲــﻓ رﻮﺼﻟا رﺎــﺸﺘﻧا ﺪﻌﻳ ﺔﻴﺨﻳرﺎﺘﻟا تﺎﻴﺼﺨــﺸﻠﻟ ﺔــﺣوﺮﻄﻤﻟا ﺔﻄﻴــﺳﻮﻟا رﻮﺼﻠﻟ مﻮﻴﻟا

؛ﺎﻴﻧرﻮﻔﻴﻟﺎﻛ ،سﻮــﻠﺠﻧأ سﻮﻠﺑ ، " دﻻﺎﻓﻼﻳد – ساﺮﺑ " ﻲﻓ ﺔــﻳدﺮﻓ ضرﺎﻌﻣ ﺎــﻬﻨﻣ ةزرﺎــﺑ ﻊﻳرﺎﺸﻣ ؛سﺎــﺴﻜﺗ ،سﻻاﺪﺑ ﻞﻜﻳﺎﻣ سﻮﺟ ﺔــﺴﺳﺆﻣ ؛ﺎﻣوﺮﺑ ﺎﻳرﺎﻣ ﺎﺘﻧﺎــﺳ ﺔــﺴﻴﻨﻛ ﺔﻴﻋﺎﻤﺟ ضرﺎﻌﻣ ﻰــﻟإ ﺔﻓﺎﺿ ﺎﺑ ؛نﺪﻨﻠﺑ سﻮﻔﻳد يﺮــﻴﻟﺎﺟ ؛ﻢﻟﻮﻬﻛﻮﺘــﺴﺑ ﻦﻴﺘــﺳ ﻲﺑﺮﻌﻟا ﻦﻔﻟا ﺪــﻬﻌﻣ ؛ﺲﻳرﺎﺒﺑ بﻮﻴﻛ ﺖﻳاو ؛ﺲﻳرﺎﺒﺑ نﻮــﺘﻴﻓ يﻮﻟ ﺔــﺴﺳﺆﻣ ﻊــﻣ ﻦﻴﺘﻛرﺎﻣ يد ؛نﺪﻨﻠﺑ نﻼــﺴﺗرﺎﻫ ؛ﻢﻟﻮﻬﻛﻮﺘــﺴﺑ دارﺎﻣﺎﻛ كرﻮﻳﻮﻴﻨﺑ ﻲﻣﻼــﺳ او ﻦﻔﻠﻟ ةﺮﺻﺎﻌﻤﻟا " زﺮــﻴﺑ " ةﺰﺋﺎﺟ ﻰﻠﻋ ﻞﺼﺣ ﺎــﻨﻴﻴﻓ / غاﺮﺑ ﻲــﻓ " ﻚــﻴﻠﻴﻣوأ " و ؛ﻞــﺴﻛوﺮﺒﺑ ﺔﻣﺎﻌﻟا تﺎﻋﻮﻤﺠﻤﻟا ﻲــﻓ ﻪﻟﺎﻤﻋأ ضﺮﻌﺗ ﺎﻤﻛ ، " لﺪــﻴﻧﺪﻳﺮﺛ " ةﺰﺋﺎﺟ ﻚــﻟﺬﻛو ﺊــﺷﺎﻨﻟا ﻲﻓ ﺎﻤﻫﻼﻛو ،ﻢﻟﻮﻬﻛﻮﺘــﺳ ﻲﻓ " ﺞــﻨﻴﻨﺘﻟﺎﻔﻟﻮﻓرﻮﺘﻟﻮﻛ " و ،ﺎﻨﻟﻮــﺴﺑ ﺎﻜــﺴﻨﻴﻟورﺎﻜﻟ . ﺪﻳﻮﺴﻟا

ART D’ÉGYPTE 35

ماﺪﺨﺘــﺳا ﺮﻓﻮﻳ . ﺮﻈﻨﻟا تﺎﻬﺟو ﺔــﻳدﺪﻌﺗ ﻮﺤﻧ ﺔﻴﺒﻠــﺴﻟا تاﺮﻈﻨﻟا ﻦﻣ ﺺﻠﺨﺘﻠﻟ ﻦــﻴﺟﺮﻔﺘﻤﻟا يﺪــﺤﺗو ،نﺪﻨﻠﺑ ﺰﻨﻴﺗرﺎﻣ ﺖﻧﺎــﺳ لاﺮﺘﻨــﺳ ﻦﻣ ﺔﻠﻴﻤﺠﻟا نﻮﻨﻔﻟا ﻲﻓ ﺮﻴﺘــﺴﺟﺎﻣ ﻒــﺳﻮﻳ ﻞﻤﺤﻳ ﺎﺿرﺎﻌﻣ مﺎﻗأ ﻢﻟﻮﻬﻛﻮﺘــﺴﺑ ،كﺎﻔﺘــﺴﻧﻮﻛ ﻦﻣ ﺔﻠﻴﻤﺠﻟا نﻮﻨﻔﻟا ﻲــﻓ سﻮــﻳرﻮﻟﺎﻜﺑو

ﺔﻓﺎﻘﺛ ﻲﻓ ﺔﻳﻮﻴﺣ ﻢــﻴﻫﺎﻔﻤﻟا ﻦﻣ ءﺰﺟ ،ﺔــﻴﻔﺨﻟا ﺎــﻬﺗاﺪﻨﺟأو ﻦﻳﺮﻣﺎﻐﻤﻠﻟ نﺎــﻨﻌﻟا قﻼﻃ ﺎﺻﺮﻓ ﺪﻳﺮﺠﺘﻠﻟ ﻲــﻜﻴﺘﻜﺘﻟا ﻒــﺳﻮﻳ

MOHAMMAD ALFARAJ GUARDIANS OF THE WIND

Steel, plastic, wood, wire 10 sculptures: 2 (2 m x 2 m), 4 (3 m x 2 m), 3 (4 m x 2 m), 1 (5 m x 2 m) 2022

The Thirst series comprises works that are closely and directly related to water and air in addition to the stories that shape human connections to them from a local, global, and cosmic perspective. The Guardians of the Wind is a figurine made from rusted water pipes used in the dried-up springs on rural farms which are transformed into an interactive musical instrument with air, animals, and people. These pipes are covered with various branches of palm trees that make them look like futuristic fossils of mythical creatures making musical sounds as the wind moves through them while people walk between and under them.

The parts of the palm trees and metal/plastic pipes are sourced from the Egyptian countryside. The work is in harmony with its context and the context of ancient Egypt, which was a marvel in irrigation and watering systems. It gazes deeply at space and the stars searching for that knowledge. The shape of the work and the locations of the figures will resemble the locations of the stars used as a guide for irrigation. It is installed on an iron base and covered with sand in order not to affect the archaeological site.

FOREVER IS NOW .02 36

ا هﺬــﻫ ﻰﻠﻋو ءاﻮــﺳ ﺪﺣ ﻰﻠﻋ سﺎﻨﻟاو تﺎﻧاﻮﻴﺤﻟاو ءاﻮــﻬﻟا ﻊــﻣ هﺬﻫ ﻒﻘﺘــﺳ ﺔﻴﻠﺒﻘﺘــﺴﻣ ةرﻮﻔﺣأ وﺪﺒﺗ ﺎﻬﻠﻌﺠﺗ ،ﻞــﻴﺨﻨﻟا ﺮﺠــﺷ ﻦــﻣ ﺔــﻔﻠﺘﺨﻣ ،ﺢﻳﺮﻟا ﻞﻌﻔﺑ ﺔﻴﻘﻴــﺳﻮﻣ ﺎــﺗاﻮﺻأ رﺪﺼﺗ ،ﺔﻳرﻮﻄــﺳأ تﺎﻗﻮﻠﺨﻤﻟ ﺮــﻴﻓﺎﺣأ تﺎﻤــﺴﺠﻤﻟا . ﺎﻬﺘﺤﺗو ﺎــﻬﻨﻴﺑ سﺎﻨﻟا ﻲــﺸﻤﻳ ﻲﺘﻟاو ﺮﺼﻣ ﻲــﻓ ﻒﻳﺮﻟا ﺎﻫرﺪﺼﻣ ﺔﻴﻜﻴﺘــﺳﻼﺒﻟا / ﺔﻳﺪﻳﺪﺤﻟا ﺐــﻴﺑﺎﻧ او ﻞــﻴﺨﻨﻟا ءاﺰــﺟأ ﻲﻓ ﺔﺑﻮﺠﻋأ ﺖــﻧﺎﻛ ﻲﺘﻟا ،ﺔﻤﻳﺪﻘﻟا ﺮــﺼﻣ قﺎﻴــﺳو ﺎﻬﻗﺎﻴــﺳ ﻊﻣ ﻞــﻤﻌﻟا ﺲــﻧﺎﺠﺘﻳ ﻚﻠﺗ ﻞﺟأ ﻦﻣ مﻮــﺠﻨﻟاو ءﺎﻀﻔﻟا ﻲــﻓ ﺔﻨﻌﻤﺘﻣو ةﺮﻇﺎﻧ ،ﺔﻳﺎﻘــﺴﻟاو يﺮــﻟا ﺔــﻤﻈﻧأ ﻲﺘﻟا تﺎﻤــﺴﺠﻤﻟا ﻊﻗاﻮﻣو ﻞﻤﻌﻟا ﻞﻜــﺸﺑ ﻼﻴﻟد ﻚــﻟذ نﻮﻜﻴــﺳ ﺚﻴﺣ

ART D’ÉGYPTE 37 ،ءاﻮﻬﻟاو ءﺎﻤﻟﺎﺑ ةﺮــﺷﺎﺒﻣو ةﺪﻴﻃو ﺔــﻗﻼﻋ ﺎﻬﻟ لﺎﻤﻋﺄﺑ ﻰــﻨﻌﺗ " ﺶــﻄﻌﻟا " ﺔﻠــﺴﻠﺳ ﻲﻤﻟﺎﻋ ﻚﻟﺬﻛو ،ﻲــﻠﺤﻣ رﻮﻈﻨﻣ ﻦــﻣ ،ﺎﻤﻬﺑ يﺮــﺸﺒﻟا طﺎﺒﺗرﻻا ﻞﻜــﺸﺗ ﻲــﺘﻟا ﺺــﺼﻘﻟاو ءﺎﻤﻟا نﻮﻴﻋ ﻲــﻓ مﺪﺨﺘــﺴﺗ هأﺪﺻ هﺎﻴﻣ ﺐﻴﺑﺎﻧأ ﻦﻣ ﻢــﺴﺠﻣ " ﺢﻳﺮﻟا ساﺮــﺣ " . ﻲــﻧﻮﻛو ﺔﻴﻠﻋﺎﻔﺗ ﺔﻴﻘﻴــﺳﻮﻣ ﺔــﻟآ نﻮﻜﻳ ﺎﻣ ﻪﺒــﺷأ ﻰﻟإ ﺔﻟﻮﺤﻣ ﻒﻳﺮﻟا عراﺰﻣ ﻲــﻓ ﺖــﻔﺟ ﻲــﺘﻟا نﺎﺼﻏأ ﺐﻴﺑﺎﻧ

ﺔــﻓﺮﻌﻤﻟا ﻰﻄﻐﺗو ﺔﻳﺪﻳﺪﺣ ةﺪــﻋﺎﻗ ﻰﻠﻋ لﺎــﻤﻋ ا ﺖﻴﺒﺜﺗ ﻢﺘﻴــﺳ . يﺮﻟا مﻮــﺠﻧ ﻊــﻗاﻮﻣ ﻪﺒــﺸﺘﺳ . يﺮﺛ ا ﻊﻗﻮﻤﻟا ﻰــﻠﻋ ﺎﻫدﻮﺟو ﺮﺛﺆﻳ ﻻ ﻰــﺘﺣ ﻞــﻣﺮﻟﺎﺑ جﺮﻔــﻟا ﺪﻤﺤﻣ ﺢــﻳﺮــﻟا ساﺮــــﺣ ﻚﻠﺳ ،ﺐﺸﺧ ،ﻚﺘــﺳﻼﺑ ،ﺐﻠﺻ ( م٢ × م٥ ) ١ ، ( م٢ × م٤ ) ٣ ، ( م٢ × م٣ ) ٤ ، ( م٢ × م٢ ) ٢ : تﺎﻧﺎﻴﻛ ١٠ ٢٠٢٢

MOHAMMAD ALFARAJ

G UA RDI A NS OF THE W IND

Photo: MO4 Network

Photo: MO4 Network

جﺮﻔــﻟا ﺪﻤﺤﻣ ﺢــﻳﺮــﻟا ساﺮــــﺣ

Mohammad Alfaraj was born in al-Ahsa, a palm tree oasis and source of palm oil in Saudi Arabia, where he also lives and works. He studied engineering and grew up loving the camera. Alfaraj’s work can be described as a cinematic collage of media, practices, and ideas that create a world charged with stories, poetry, and a search for truth through exploration, documentation, and interpretation. This results in works that the artist hopes will nurture the imagination and empathy in those who experience them. His use and reuse of organic and manmade waste plays as a physical capsule of memories and time, where these materials and their histories hold a spiritual quality as well. A visual artist who works in film, photography, sculpture, and poetry, He is influenced by his hometown and his travels and constantly attempts to capture the trace, imprint, and impact of life both literally and metaphorically. He also engages in workshops and action-based activities in the community as part of his belief in collective creativity. He is represented by Athr gallery in Saudi Arabia, and his work has been shown at the Saudi Film Festival, the Saudi Art Council, the Sharjah Arts Foundation, ArtJameel, and the Lyon Biennale.

FOREVER IS NOW .02 40

ﺔﻴﻨﻓ تﺎــﺳرﺎﻤﻤﺑ ﻪﻣﺎﻤﺘﻫا تﺬــﻏ ﺔﻨﻳﺪﻣ ﻲﻫو ،ءﺎــﺴﺣ ا ﻲﻓ ﺪﻟو جﺮــﻔﻟا ﺪــﻤﺤﻣ ﻲﻓاﺮﻏﻮﺗﻮﻔﻟا ﺮــﻳﻮﺼﺘﻟاو ﻮﻳﺪﻴﻔﻟاو مﻼــﻓ ا ﺔﻋﺎﻨﺻ ﻦــﻣ ،ةدﺪــﻌﺘﻣ ﺔــﻴﻓﺎﻘﺛو ،ﺺﺼﻘﻟﺎﺑ ﺎﻧﻮﺤــﺸﻣ ﺎﻤﻟﺎﻋ مﺪــﻘﻳ ﺎﻬﻟﻼﺧ ﻦﻣ ﻲــﺘﻟاو ،ﺔــﺑﺎﺘﻜﻟاو تﺎــﺒﻴﻛﺮﺘﻟاو نﺎﻨﻓ . مﺪﻘﺘﻟاو ﺔــﺛاﺪﺤﻟا ﺔﺤﻨﺟأو ،ﺪــﻴﻟﺎﻘﺘﻟاو ءﺎﻤﺘﻧﻻا روﺬــﺟ ﻦﻴﺑ ﺎــﻣ ادوﺪــﺸﻣو ﻪﻟﺎﻤﻋأ ﺐﻠﺻ ﻲــﻓ لﺎﻴﺨﻟاو ضر او ﺔﻴﻧﺎــﺴﻧﻻا ﺔﺑﺮﺠﺘﻟا ﻰــﻠﻋ ﺪــﻤﺘﻌﻳ ،مﻮﻬﻔﻤﻟاو ﻞﻜــﺸﻟا ﻦﻴﺑ ﺔﻗﻼﻌﻠﻟ ﻪﻓﺎــﺸﻜﺘﺳاو ﻪــﺒﻳﺮﺠﺗ ﻮﻫ ﻪﺘــﺳرﺎﻤﻣ ﺮــﻫﻮﺟ ﻦﻣ ﺔﺒﻛﺮﻤﻟا ﻪــﻟﺎﻤﻋأو ةرﺮﺤﻤﻟا ﺔــﻴﻓاﺮﻏﻮﺗﻮﻔﻟا هرﻮــﺻ لﻼﺧ ﻦﻣ ﻪﺘﻳؤر ﻦــﻜﻤﻳ يﺬــﻟاو ﻪﻣﻼﻓأو ،ﺎﻬﻣاﺪﺨﺘــﺳا ﺪﻴﻌﻳو ﺔــﻨﻳﺪﻤﻟاو ﻒﻳﺮﻟا ﻦﻴﺑ

نأ نﺎﻤﻳﺈﺑ ،ﺔﻗﻼﻌﻟا هﺬــﻫ ﺐﻴﺼﻳ يﺬــﻟا ﻞﻠﺤﺘﻟاو ،ىﺮــﺧ ا تﺎــﻨﺋﺎﻜﻟاو ﺔــﻌﻴﺒﻄﻟاو ﻰﻠﻋ ﺔﻤﺋﺎﻘﻟا ﺔﻄــﺸﻧ او ﻞﻤﻌﻟا شرو ﻲــﻓ كرﺎــﺸﻳ ﺎﻤﻛ . ﻤﺋاد ﺎﻨﻳﺪﻳأ ﻲــﻓ صﻼــﺨﻟا ﻲﻓ ﺮﺛأ ضﺮﻌﻣ ﻪــﻠﺜﻤﻳ . ﻲﻋﺎﻤﺠﻟا عاﺪــﺑ ﺎﺑ ﻪﻧﺎﻤﻳإ ﻦــﻣ ءﺰﺠﻛ ﻊــﻤﺘﺠﻤﻟا ﻲــﻓ ﻞــﻤﻌﻟا ،يدﻮﻌــﺴﻟا ﻢﻠﻴﻔﻟا نﺎﺟﺮﻬﻣ ﻲــﻓ ﻪﻟﺎﻤﻋأ ﺖﺿﺮﻋو ،ﺔﻳدﻮﻌــﺴﻟا ﺔــﻴﺑﺮﻌﻟا ﺔــﻜﻠﻤﻤﻟا ﻲﻟﺎﻨﻴﺑو ،ﻞــﻴﻤﺟ ﻦﻓو ،نﻮﻨﻔﻠﻟ ﺔﻗرﺎــﺸﻟا ﺔــﺴﺳﺆﻣو ،نﻮﻨﻔﻠﻟ يدﻮﻌــﺴﻟا ﺲــﻠﺠﻤﻟاو نﻮﻴﻟ

Represented by ﻪﻠﺜﻤﻳ نﺎــﻨﻔﻟا

ART D’ÉGYPTE 41

ﺎــﻣ ﺎﻬﻴﻠﻋ ﺮــﺜﻌﻳ ءاﺰــﺟأو داﻮــﻣ ﺔﻴﻟﺎﻴﺨﻟا تﺎــﻋﻮﺿﻮﻤﻟا ﻦﻴﺑ ﺎــﻣ ﻊﻤﺠﺗ ﻲﺘﻟا ،ةرﻮــﺼﻟاو تﻮــﺼﻟﺎﺑ ﺔﻌﺒــﺸﻤﻟا ةﺮــﻴﺼﻘﻟا ﺎﻫﺮﻴﻏو ﺔﻴﻌﻴﺒﻄﻟا داﻮــﻤﻟا ماﺪﺨﺘــﺳا ﺪﻴﻌﻳو مﺪﺨﺘــﺴﻳ ﺎﻣ ﺎــﺒﻟﺎﻏ . ﺔــﻴﻟﺎﻴﺨﻟا ﺮــﻴﻏو لﺎﻔﻃ ا بﺎﻌﻟأ ﻊــﻣ ﺎﻬﻌﻤﺠﻳو ،ﺎــﻫروﺰﻳ ﻲﺘﻟا نﺪﻤﻟاو ءﺎــﺴﺣ ا ﻲﻓ ةدﻮــﺟﻮﻤﻟا ﺔﻧﻮﺤــﺸﻣ لﺎﻤﻋأ ﻖﻠﺨﻟ ﺔﻟوﺎﺤﻣ ﻲــﻓ ،ﺔﻴﺋﺎﻨﻟاو ةﺮــﻴﺒﻜﻟا نﺪﻤﻟا ﻲــﻓ سﺎــﻨﻟا ﺺــﺼﻗو نﺎــﺴﻧ ا ﻦﻴﺑ

ﺶﻳﺎﻌﺘﻟا ﻦﻣ تﻻﺎﺣو ،ﺔــﻓﺮﻌﻤﻟاو لﺎــﻴﺨﻟﺎﺑو ﺮﻌــﺸﻟاو ةﺮــﻛاﺬﻟﺎﺑ

NATALIE CLARK

S PIRIT OF H ATHOR

Corten steel, Carrara marble

6 m x 2.2 m x 2.2 m 2022

The beloved Goddess Hathor embodies all that is universally feminine—beauty, love, fertility, music, dancing, and pleasure. Loved equally by all women and men, she was the counterpart of the Sun God Ra and the Sky God Horus and honoured as the symbolic mother of the pharaohs.

Strong of spirit, a protector of women in body and soul, for rich and poor alike, Hathor maintained order and harmony, balanced the light and the dark, and was worshipped as the Goddess of the Afterlife.

In the Spirit of Hathor, the sensuously curved interlocking horns reach up to the heavens balancing the implied masculinity of the bold steel in a harmonious union, holding the marble sun on high for all to see while echoing the sacred geometrical lines of the Great Pyramids.

Such is the power of the Goddess Hathor.

FOREVER IS NOW .02 42

ﺔﻜﺑﺎــﺸﺘﻤﻟا قاﻮﺑ ا ﺪﺘﻤﺗ ، " رﻮــﺤﺘﺣ حور " ﻲــﻓ ﺔﻠﻣﺎﺣ ،ﺔﻤﻏﺎﻨﺘﻣ ةﺪــﺣو ﻲﻓ ﺐــﻠﺼﻟا ذﻻﻮﻔﻠﻟ ﺔﻴﻨﻤﻀﻟا ةرﻮــﻛﺬﻟا نزاﻮــﺘﻟ ءﺎﻤــﺴﻟا ﺔﻴــﺳﺪﻨﻬﻟا طﻮﻄﺨﻟا ىﺪﺻ ددﺮﺘﻳ ﺎــﻤﻨﻴﺑ ،ﻊﻴﻤﺠﻟا ﺎــﻫاﺮﻴﻟ ﺎــﻴﻟﺎﻋ ﺔــﻴﻣﺎﺧﺮﻟا ﺲﻤــﺸﻟا . ﺔﻤﻴﻈﻌﻟا تﺎــﻣاﺮﻫ ﻟ ﺔــﺳﺪﻘﻤﻟا

ART D’ÉGYPTE 43 لﺎﻤﺠﻟا - نﻮﻜﻟا ﻲــﻓ يﻮﺜﻧأ ﻮﻫ ﺎﻣ ﻞﻛ رﻮــﺤﺘﺣ ﺔــﺑﻮﺒﺤﻤﻟا ﺔــﻬﻟ ا ﺪــﺴﺠﺗ لﺎﺟﺮﻟا ﻦﻣ ﻞﻛ ﺎــﻬﺒﺣأ . ﺔﻌﺘﻤﻟاو ﺺــﻗﺮﻟاو ﻰﻘﻴــﺳﻮﻤﻟاو ﺔــﺑﻮﺼﺨﻟاو ﺐــﺤﻟاو ﺎﻬﻤﻳﺮﻜﺗ ﻢــﺗو ،سرﻮﺣ ءﺎﻤــﺴﻟا ﻪﻟإو عر ﺲﻤــﺸﻟا ﻪﻟإ ﺮﻴﻈﻧ ﺖﻧﺎﻛ ﺚــﻴﺣ ،ءﺎــﺴﻨﻟاو ﺔﻨﻋاﺮﻔﻠﻟ ﺔــﻳﺰﻣر مﺄﻛ ءﺎﻴﻨﻏ ا ﻲﻤﺤﺗ ،ﺎــﻬﺣورو ةأﺮﻤﻟا ﺪــﺴﺟ ﻲﻤﺤﺗ ﺔﻳﻮﻗ حوﺮــﺑ رﻮــﺤﺘﺣ ﻊــﺘﻤﺘﺗ رﻮﻨﻟا ﻦﻴﺑ ﺎــﻣ نزاﻮﺗو ،مﺎﺠــﺴﻧﻻاو

ﻰﻟإ

رﻮﺤﺘﺣ ﺔﻬﻟ ا ةﻮــﻗ ﻲﻫ هﺬﻫ كرﻼـﻛ ﻲــــﻟﺎــﺗﺎــﻧ رﻮــﺤـﺘـﺣ حور ةراﺮﻛ مﺎﺧر ، " ﻦﺗرﻮﻛ " ﺐــﻠﺻ م٢،٢ × م٢،٢ × م٦ ٢٠٢٢

مﺎﻈﻨﻟا ﻰﻠﻋ ﻆﻓﺎﺤﺗ ،ءاﻮــﺳ ﺪﺣ ﻰــﻠﻋ ءاﺮــﻘﻔﻟاو . ىﺮﺧ ا ةﺎﻴﺤﻟا ﺔــﻬﻟإ ﺎﻫرﺎﺒﺘﻋﺎﺑ تﺪــﺒﻋ ،مﻼــﻈﻟاو

ﻲــﺴﺣ ﻞﻜــﺸﺑ ﺔﻓﻮﻘﻌﻤﻟاو

NATALIE CLARK SP IRIT OF HATH O R

Photo: MO4 Network

Photo: MO4 Network

كرﻼـﻛ ﻲــــﻟﺎــﺗﺎــﻧ رﻮــﺤـﺘـﺣ حور

Natalie Clark .is a classically trained British American sculptor, collector, art advisor, educator, and author. Influenced by extensive travels around the world, her work is a global fusion of modern design, indigenous art forms, and organic inspirations found in nature. Whether travelling to Lima, Peru; Cape Town, South Africa; or the Australian Outback, she recognises common cultural threads and integrates them into her work using organic and man-made materials. Her current work includes large-scale sculpture in a variety of media, including marble, steel, ceramics, and natural materials.

After obtaining a BFA (majoring in sculpture) from Brighton University in England, Clark came to the United States on a full merit scholarship and attained her MFA from the Art Institute of Chicago. Exhibitions in the United States, United Kingdom, Mexico, Canada, Japan, Spain, Australia, and South Africa, as well as international collaborations and commissions for public projects, have cemented her status as a leading contemporary sculptor among important private and corporate collections worldwide.

Clark’s story and innovative sculptures—featured on ‘Good Morning America’, HGTV, nationally syndicated radio programs, interior design magazines, and international newspapers—have garnered ever growing attention to her creative contributions.

FOREVER IS NOW .02 46

ةرﺎــﺸﺘﺴﻣو تﺎﻴﻨﺘﻘﻣ ﺔﻌﻣﺎﺟو ﺔﻴﻜﻴــﺳﻼﻛ ﺔــﺗﺎﺤﻧ ﻲــﻫ كرﻼﻛ ﻲــﻟﺎﺗﺎﻧ ةﺪﻳﺪﻌﻟا ﺎﻬﺗﺎﻳﺮﻔــﺴﺑ تﺮﺛﺄﺗ ﺔــﻴﻜﻳﺮﻣأ ﺔﻳﺰﻴﻠﺠﻧإ ﺔــﻔﻟﺆﻣو ﺔــﻤﻠﻌﻣو ﺔــﻴﻨﻓ تﺎﻤﻴﻤﺼﺘﻠﻟ ﻼﻣﺎــﺷ ارﺎﻬﺼﻧا ﻞــﺜﻤﺗ ﺎﻬﻟﺎﻤﻋأ ﺖــﺤﺒﺻﺄﻓ ،ﻢﻟﺎﻌﻟا ءﺎــﺤﻧأ ﻰــﻟإ ﻒــﺸﺘﻜﺗ . ﺔﻌﻴﺒﻄﻟا ﻦﻣ ﺎــﻳﻮﻴﺣ ﺎﻣﺎﻬﻟإو ،ﺔﻠﻴﺻأ ﺔــﻴﻨﻓ ﻻﺎﻜــﺷأو ،ﺔــﺜﻳﺪﺤﻟا تﺮﻓﺎــﺳ ءاﻮــﺳ ﺔﻔﻠﺘﺨﻣ تارﺎﻀﺣ ﻦﻴﺑ ﺔﻛﺮﺘــﺸﻣ ﺔــﻴﻓﺎﻘﺛ ﺎــﻃﻮﻴﺧ كرﻼﻛ ﺔﻴﺋﺎﻨﻟا ﻖــﻃﺎﻨﻤﻟا ﻰﻟإ وأ ،ﺎﻴﻘﻳﺮﻓأ بﻮــﻨﺠﺑ نوﺎﺗ ﺐــﻴﻛ وأ ،وﺮﻴﺑ ﻲــﻓ ﺎــﻤﻴﻟ ﻰــﻟإ داﻮﻣ ماﺪﺨﺘــﺳﺎﺑ ﺎﻬﻠﻤﻋ ﻲﻓ طﻮــﻴﺨﻟا ﻚﻠﺗ ﺞﻣﺪﺑ مﻮــﻘﺗو ،ﺎﻴﻟاﺮﺘــﺳأ

ﺔﻴــﺳارد ﺔــﺤﻨﻣ

نﻮﻨﻔﻠﻟ ﻮﻏﺎﻜﻴــﺷ ﺪﻬﻌﻣ ﻦــﻣ ﺔﻠﻴﻤﺠﻟا نﻮــﻨﻔﻟا ﻲــﻓ ﺮﻴﺘــﺴﺟﺎﻤﻟا ةﺪﺤﺘﻤﻟا ﺔــﻜﻠﻤﻤﻟاو ﺔﻴﻜﻳﺮﻣ ا ةﺪــﺤﺘﻤﻟا تﺎــﻳﻻﻮﻟا ﻲﻓ ضرﺎــﻌﻤﻟا ﻼﻀﻓ ،ﺎﻴﻘﻳﺮﻓإ بﻮــﻨﺟو ﺎﻴﻟاﺮﺘــﺳأو ﺎﻴﻧﺎﺒــﺳإو نﺎﺑﺎﻴﻟاو اﺪــﻨﻛو ﻚﻴــﺴﻜﻤﻟاو ﺔﺗﺎﺤﻨﻛ ﺎــﻬﺘﻧﺎﻜﻣ ،ﺔﻣﺎﻌﻟا ﻊﻳرﺎــﺸﻤﻟا نﺎﺠﻟو ﻲــﻟوﺪﻟا نوﺎﻌﺘﻟا ﻦــﻋ ﺔﺻﺎﺨﻟا تﺎﻴﻨﺘﻘﻤﻟا تﺎــﻋﻮﻤﺠﻣ ﻲــﻓ ﺎﻬﻟﺎﻤﻋأ ﺖــﻓﺮﻋو ةﺪﺋار ةﺮــﺻﺎﻌﻣ ﻢﻟﺎﻌﻟا ءﺎﺤﻧأ ﻊــﻴﻤﺟ ﻲﻓ ﺔــﻣﺎﻌﻟاو ﺞﻣﺎﻧﺮﺑ ﻲﻓ تﺮــﻬﻇ ﻲﺘﻟا - ةﺮــﻜﺘﺒﻤﻟا تﺎــﺗﻮﺤﻨﻤﻟاو كرﻼﻛ ﺔــﺼﻗ ﺖــﻴﻈﺣ رﻮﻜﻳﺪﻟاو ﻢﻴﻤﺼﺘﻠﻟ ﻲــﻜﻳﺮﻣ ا نﻮــﻳﺰﻔﻠﺘﻟا ةﺎــﻨﻗو ،ﺎﻜﻳﺮﻣا ﺮــﻴﺨﻟا حﺎــﺒﺻ . ﺔﻴﻋاﺪﺑ ا ﺎﻬﺗﺎﻣﺎﻬــﺳﺈﺑ ﺪــﻳاﺰﺘﻣ مﺎــﻤﺘﻫﺎﺑ - HGTV

Thanks to ﺮﻜــﺸﻟﺎﺑ ﺔﻧﺎﻨﻔﻟا مﺪــﻘﺘﺗ

ART D’ÉGYPTE 47

ﻲــﻓ تﺎﺗﻮﺤﻨﻣ ﺔــﻴﻟﺎﺤﻟا ﺎﻬﻟﺎﻤﻋأ ﻞﻤــﺸﺗ نﺎــﺴﻧ ا ﻊﻨﺻ ﻦﻣ تﺎــﻣﺎﺧو ﺔــﻳﻮﻀﻋ مﺎﺧﺮﻟا ﻚﻟذ ﻲﻓ ﺎــﻤﺑ ،ةدﺪﻌﺘﻣ ﻂﺋﺎــﺳو ﻦﻣ نﻮﻜﺘﺗ ﻢــﺠﺤﻟا ةﺮــﻴﺒﻛ . ﺔﻴﻌﻴﺒﻃ داﻮــﻣو ﻚﻴﻣاﺮﻴــﺴﻟاو ﺐﻠﺼﻟاو ﻦﻣ ( ﺖﺤﻧ ﺺﺼﺨﺗ ) ﺔــﻠﻴﻤﺠﻟا نﻮــﻨﻔﻟا سﻮﻳرﻮﻟﺎﻜﺑ ﻰــﻠﻋ ﺎــﻬﻟﻮﺼﺣ ﺪــﻌﺑ ﻲﻓ ةﺪﺤﺘﻤﻟا تﺎــﻳﻻﻮﻟا ﻰﻟإ كرﻼﻛ تﺮﻓﺎــﺳ ،اﺮﺘﻠﺠﻧإ ﻲﻓ نﻮــﺘﻳاﺮﺑ ﺔــﻌﻣﺎﺟ ةدﺎﻬــﺷ ﻰﻠﻋ ﺖﻠﺼﺣو ،ةراﺪﺟ ﻦﻋ ﺎﻬﺘﻘﺤﺘــﺳا ﺔﻠﻣﺎﻛ

تزﺰﻋ

PASCALE M ARTHINE TAYOU DREAMS IN GIZA

Stainless steel, wood 12 m x 5 m 2022

Dreams In Giza is a monumental artwork especially created for Forever Is Now .02 and sponsored by GALLERIA CONTINUA. It’s a perfect union of the colorful and exuberant art of Pascale Marthine Tayou and the majestic and timeless history and culture of Egypt.

Twenty stainless steel tubes rise from the hot sand. Like futes, ancient witnesses of the banquets and celebrations of the pharaohs, these new totems whistle and play with the wind. They are adorned with colored wooden eggs, symbols of good omen, of rebirth, a key element in the works of Tayou but also a reference to ancient Egyptian mythology, where the Cosmic Egg held a central place as a primordial symbol of birth and creation, generating the sun god Ra.

‘This project is an inspired poem, From the verses of the gods because...

Last night I dreamed that I was a baby pharaoh...

Lying in a golden egg-shaped cradle delicately placed in the heart of the treasures of Giza.’

FOREVER IS NOW .02 48

زﺮــﺒﻳ ،مﺪﻘﻟا ﻲﻓ ﻦﻴﻳﺮﺼﻤﻟا ءﺎــﻣﺪﻗ تﻻﺎــﻔﺘﺣاو بدﺂﻣ تﺎﻳﺎﻨﻟا تﺪﻬــﺷ ﺎــﻤﻛو ﻦﻣ نﻮﻠﻣ ﺾﻴﺑ ﺎــﻬﻨﻳﺰﻳ ،ﺢﻳﺮﻟا ﻊــﻣ ﺐﻌﻠﺗو ةﺪﻳﺪﺠﻟا ﻢــﻃاﻮﻄﻟا هﺬــﻫ ﺮــﻔﺼﺗ ﻲﻓ ﻲــﺳﺎﺳأ ﺮﺼﻨﻋ ﻞﻜــﺸﺗ ﻲﺘﻟاو ،ﺚﻌﺒﻟاو ﺐﻴﻄﻟا لﺄــﻔﻟا ﻰﻟإ ﺰــﻣﺮﻳ ﺐــﺸﺨﻟا ﺚﻴﺣ ،ﺔﻤﻳﺪﻘﻟا ﺔــﻳﺮﺼﻤﻟا ﺮﻴﻃﺎــﺳ ا ﻰﻟإ ﺎﻀﻳأ ﺮﻴــﺸﺗ ﺎﻬﻧإ ﺎﻤﻛ ،ﻮــﻳﺎﺗ لﺎــﻤﻋأ قﺎﺜﺒﻧاو ﺔﻘﻴﻠﺨﻟاو ةدﻻﻮــﻠﻟ ﺰــﻣﺮﻛ ﺔﻳﺰﻛﺮﻣ ﺔﻧﺎﻜﻣ ﺔــﻴﻧﻮﻜﻟا ﺔــﻀﻴﺒﻟا

ART D’ÉGYPTE 49 ﺎﺼﻴﺼﺧ نﺎــﻨﻔﻟا ﻪﻤﻴﻘﻳ ﻢــﺨﺿ ﻲﻨﻓ ﻞﻤﻋ ﻮــﻫ " ةﺰﻴﺠﻟا ﻲــﻓ مﻼــﺣأ " ﻮﻫو ، " اﻮﻴﻨﺘﻧﻮﻛ ﺎــﻳﺮﻴﻟﺎﺟ " ﺔــﻳﺎﻋﺮﺑ ﻞﻤﻋ ﻮﻫو ،٢ ن ا ﻮــﻫ ﺪــﺑ ا عوﺮﺸﻤـــﻟ ،ةﺎﻴﺤﻟﺎﺑ ﺾــﺑﺎﻨﻟا نﻮﻠﻤﻟا ﻮــﻳﺎﺗ ﻦﻴﺗرﺎﻣ لﺎﻜــﺳﺎﺑ ﻦﻓ ﻦﻴﺑ يﻮﻗ دﺎــﺤﺗا ﻞﻜــﺸﻳ ﺔﻳﺮﺼﻤﻟا ﺔــﻓﺎﻘﺜﻟاو ﺪﻟﺎﺨﻟا ﺐــﻴﻬﻤﻟا ﺦﻳرﺎﺘﻟا ﻦــﻴﺑو ،ﺔﻨﺧﺎــﺴﻟا لﺎﻣﺮﻟا ﻦﻣ أﺪﺼﻠﻟ موﺎــﻘﻤﻟا ذﻻﻮﻔﻟا ﻦﻣ ﺎــﺑﻮﺒﻧأ نوﺮــﺸﻋ

ﺖــﻠﺘﺣا عر ﺲﻤﺸﻟا ﻪﻟإ ... ن ﺔﻬﻟ ا تﺎﻳآ ﻦﻣ ﺔــﻤﻬﻠﻣ ةﺪﻴﺼﻗ ﻮــﻫ عوﺮــﺸﻤﻟا اﺬــﻫ " ﺮﻴﻐﺻ نﻮﻋﺮﻓ ﻲــﻧﺄﺑ ﺖﻤﻠﺣ ﺔــﻴﺿﺎﻤﻟا ﺔــﻠﻴﻠﻟا ﺐﻠﻗ ﻲﻓ ﺔﻗﺪﺑ ﺔــﻋﻮﺿﻮﻣ ﺔﻀﻴﺑ ﻞﻜــﺷ ﻰﻠﻋ ﻲﺒﻫذ ﺪــﻬﻣ ﻲــﻓ ﻖﻠﺘــﺴﻣ ." ةﺰﻴﺠﻟا زﻮــﻨﻛ ﻮــﻳﺎـﺗ ﻦــــﻴـﺗرﺎـﻣ لﺎـــﻜﺳﺎـﺑ ةﺰــــﻴـﺠﻟا ﻲﻓ مﻼﺣأ ﺐــﺸﺧ ، أﺪﺼﻠﻟ ﻞﺑﺎﻗ ﺮﻴﻏ ﺐــﻠﺻ م٥ × م١٢ ٢٠٢٢

PASCALE M ARTHINE TAYOU DREAMS IN GIZA

Photo: MO4 Network

Photo: MO4 Network

ﻮــﻳﺎـﺗ ﻦــــﻴـﺗرﺎـﻣ لﺎـــﻜﺳﺎـﺑ ةﺰــــﻴـﺠﻟا ﻲﻓ مﻼﺣأ

Pascale Marthine Tayou lives and works in Ghent, Belgium and Yaoundé, Cameroon. Since the 1990s and his participation in Documenta 11 (2002) in Kassel and at the Venice Biennale (2005 and 2009), Tayou has been known to a broad international public. His work is characterised by its variability; he does not confne himself to one medium nor to a particular set of issues. While his themes may vary, they all use the artist himself as a person as their point of departure. At the very outset of his career, Pascale Marthine Tayou added an ‘e’ to his frst and middle names to give them a feminine ending, thus distancing himself ironically from the importance of artistic authorship and male/female ascriptions. This also holds true for any attempt at reduction to a specifc geographical or cultural origin as well. His works not only mediate in this sense between cultures or set man and nature in ambivalent relations to each other but are produced in the knowledge that they are social, cultural, or political constructions. His work is deliberately mobile, elusive of pre-established schema, heterogeneous. It is always closely linked to the idea of travel and of encountering what is other to the self and is so spontaneous that it almost seems casual. The objects, sculptures, installations, drawings, and videos produced by Tayou have a recurrent feature in common: they dwell upon an individual moving through the world and exploring the issue of the global village. And it is in this context that Tayou negotiates his African origins and related expectations.

FOREVER IS NOW .02 52

يﺪﻧوﺎﻳ ﻲﻓو ﺎﻜﻴﺠﻠﺒﺑ ﺖﻨﻴﻏ ﻲــﻓ ﻞﻤﻌﻳو ﺶﻴﻌﻳ ﻮﻳﺎﺗ ﻦــﻴﺗرﺎﻣ لﺎﻜــﺳﺎﺑ ﺬﻨﻣ ﻲﻟوﺪﻟا ىﻮﺘــﺴﻤﻟا ﻰﻠﻋ ﺮﻴﺒﻛ رﻮﻬﻤﺠﻟ ﻮﻳﺎﺗ فﺮﻋ نوﺮــﻴﻣﺎﻜﻟﺎﺑ مﺎﻋ "١١ ﺎﺘﻨﻣﻮﻴﻛود" ﻲﻓ ﻪﺘﻛرﺎــﺸﻣ ﺪﻌﺑ ﺔﺻﺎﺧو ﻲﺿﺎﻤﻟا نﺮﻘﻟا تﺎﻴﻨﻴﻌــﺴﺗ ﻮﻳﺎﺗ ﺰﻴﻤﺗ .(٢٠٠٩ ،٢٠٠٥ ) ﺔﻴﻗﺪﻨﺒﻟا ﻲﻟﺎﻨﻴﺑ ﻲﻓ ﻪﺘﻛرﺎــﺸﻣ ﻢﺛ ،ﻞــﺳﺎﻛ ﻲﻓ ٢٠٠٢ ﻦﻣ ﺔﻨﻴﻌﻣ ﺔﻋﻮﻤﺠﻣ ﻻو ﺪﺣاو ﻂﻴــﺳو ﻰﻠﻋ ﻪﻟﺎﻤﻋأ ﺮﺼﻘﻳ ﻻ ﻮــﻬﻓ ،عﻮــﻨﺘﻟﺎﺑ ﺺﺨــﺷ ﺎﻬﻌﻴﻤﺟ مﺪﺨﺘــﺴﺗ ﺎﻬﻨﻜﻟو ،ﻪﻌﻴﺿاﻮﻣ فﻼﺘﺧا ﻢﻏﺮﺑو ،ﺎﻳﺎﻀﻘﻟا ﻦﻴﺗرﺎﻣ لﺎﻜــﺳﺎﺑ" فﺎﺿأ ،ﻪﺗﺮﻴــﺴﻣ ﺔﻳاﺪﺑ ﻲﻓ قﻼﻄﻧا ﺔﻄﻘﻨﻛ ﻪﺗاذ نﺎﻨﻔﻟا ﻢﻬﺤﻨﻤﻟ Pascale Marthine ﺢﺒﺼﻴﻟ ﻂــﺳو او لو ا ﻪﻴﻤــﺳ “

ﺔﻠﺑﺎﻗ ﻪﻟﺎﻤﻋأ ﺔﻴــﺳﺎﻴﺳ وأ ﺔﻴﻓﺎﻘﺛ وأ ﺔﻴﻋﺎﻤﺘﺟا ﻞﻛﺎﻴﻫ ﻂﺒﺗﺮﺗ ﻲﻬﻓ ،ﺎﻘﺒــﺴﻣ دﺪﺤﻣو ﺲﻧﺎﺠﺘﻣ ﺮﻴﻏ ﻂﻄﺨﻣ ﺎﻫﺮﻃﺆﻳ ﻻو ،ﺪــﻤﻌﺘﻣ ﺔﻳﻮﻔﻌﺑو ﺲﻔﻨﻟا ﻲﻓ ﺮﺧ ا ﻰﻨﻌﻣ ﺔــﻬﺟاﻮﻣو ﺮﻔــﺴﻟا ةﺮﻜﻔﺑ ﺎﻘﻴﺛو ﺎﻃﺎﺒﺗرا ﻦﻣ ﻮﻳﺎﺗ ﺎﻬﺠﺘﻧا ﻲﺘﻟا ﺔﻴﻨﻔﻟا لﺎــﻤﻋ ا ﻞﻤﺤﺗ .ﺮﺑﺎﻋ ﺮﻣأ ﻪﻧﺄﻛو وﺪــﺒﻴﻓ ،ةﺪﻳﺪــﺷ ﻊﻃﺎﻘﻣو تﺎﻣﻮﺳﺮﻟاو (ﻦــﺸﻴﻠﺘﺴﻧا) غاﺮﻔﻟا ﻲﻓ تﻼﻴﻜــﺸﺗو تﺎﺗﻮﺤﻨﻤﻟا ﻢﻟﺎﻌﻟا ﺮﺒﻋ ﻞﻘﺘﻨﻳ دﺮﻓ لﻮﺣ روﺪﺗ ﻲﻬﻓ ،ةرﺮﻜﺘﻣ ﺔﻛﺮﺘــﺸﻣ ﺔﻤــﺳ ،ﻮﻳﺪﻴﻔﻟا ﻪﻟﻮﺻأ قﺎﻴــﺴﻟا اﺬﻫ ﻲﻓ ﺶﻗﺎﻨﻳ ﺚﻴﺣ ،ﺔﻴﻧﻮﻜﻟا ﺔﻳﺮﻘﻟا ﺔﻴﻀﻗ ﻒــﺸﻜﺘﺴﻳو ﻚﻟﺬﺑ ﺔﻄﺒﺗﺮﻤﻟا تﺎﻌﻗﻮﺘﻟا ﻊــﻴﻤﺟو ﺔﻴﻘﻳﺮﻓ ا

Represented by ﻪﻠﺜﻤﻳ نﺎــﻨﻔﻟا

ART D’ÉGYPTE 53

e " فﺮﺣ "ﻮﻳﺎﺗ ﺔﻴﻤﻫأ ﻦﻋ ﺮﺧﺎــﺳ ﻞﻜــﺸﺑ ﻪــﺴﻔﻨﺑ ىﺄﻧ ﻲﻟﺎﺘﻟﺎﺑو ،ﺔﻤﻠﻜﻠﻟ ﺔﻳﻮﺜﻧأ ﺔﻳﺎﻬﻧ يأ ﻰﻠﻋ ﺎﻀﻳأ اﺬﻫ ﻖﺒﻄﻨﻳو ،ثﺎﻧ ا وأ رﻮــﻛﺬﻠﻟ ﻲﻨﻔﻟا ﻒــﻴﻟﺄﺘﻟا ﺐــﺴﻨﻳ نأ ﺎﻌﻗﻮﻣ ﻪﻟﺎﻤﻋأ ﻞﺘﺤﺗ ﻻ .ﻦﻴﻌﻣ ﻲــﻓﺎﻘﺛ وأ ﻲﻓاﺮﻐﺟ ﻞﺻأ لاﺰــﺘﺧﻻ ﺔــﻟوﺎﺤﻣ ﺔﻀﻗﺎﻨﺘﻣ تﺎﻗﻼﻋ ﻲﻓ ﺔﻌﻴﺒﻄﻟاو نﺎــﺴﻧ ا ﻊﻀﺗ وأ تﺎﻓﺎﻘﺜﻟا ﻦﻴﺑ ﺎﻄــﺳو ﺎﻬﻧأ ﺔﻓﺮﻌﻣ ﻞﻇ ﻲﻓ ﺎﻬﺟﺎﺘﻧإ ﻢــﺘﻳ ﻞﺑ ،ﺐــﺴﺤﻓ ﺾﻌﺒﻟا ﺎﻤﻬﻀﻌﺑ ﻊــﻣ

ﻞﻜــﺸﺑ لﺎﻘﺘﻧﻼﻟ

SpY

OR B : U NDER THE S AME S UN

Steel, chrome steel 4 m (diameter) 2022

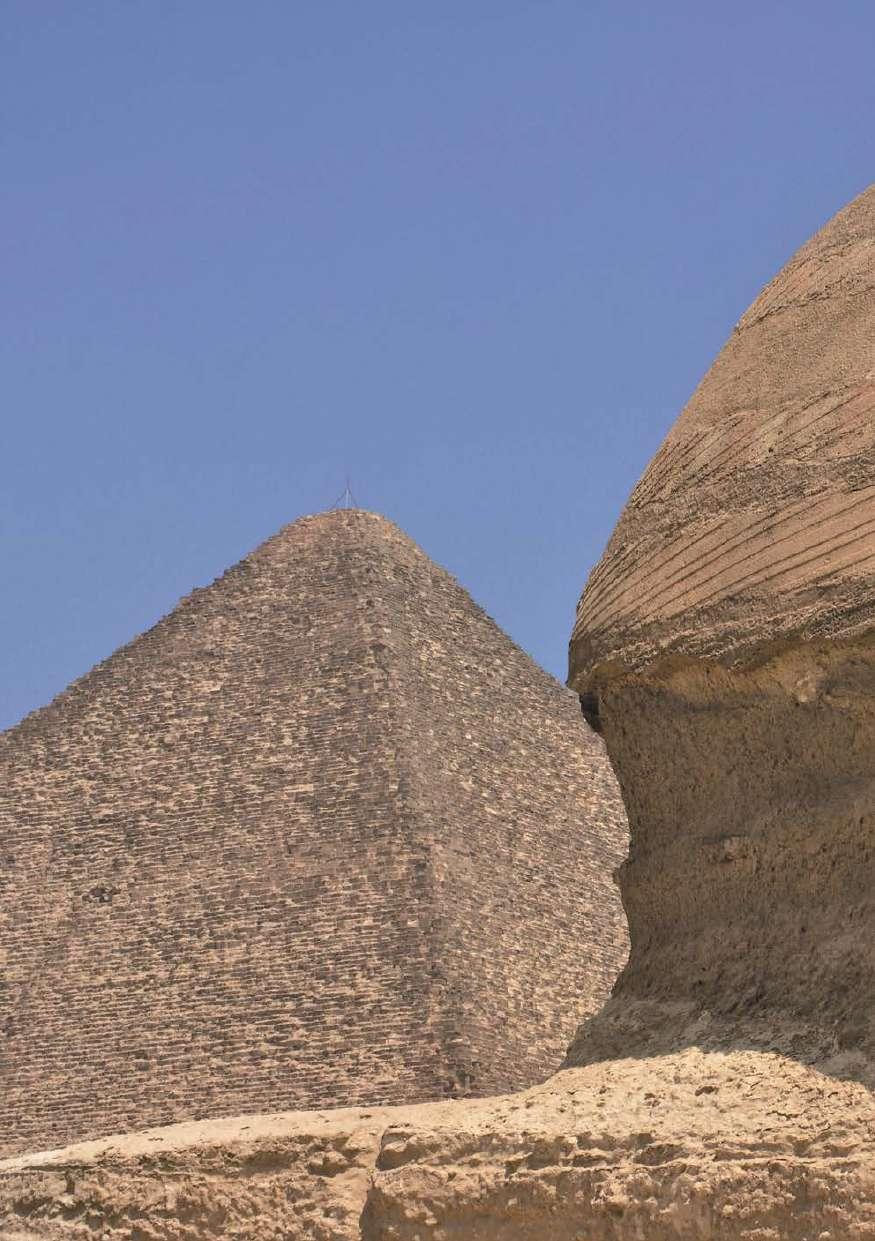

Orb draws its inspiration from the ancient Egyptian heritage around it. The choice of form and materials in the piece is presented as a direct reference to elements of mathematics and symbolism present in ancient Egyptian culture and in the pyramids in particular.

The shape of the piece alludes to the ‘pi’ number concealed in the geometry of the pyramids and found when dividing the perimeter of a pyramid by twice its height. The sphere is an invisible part of the resulting geometry since a sphere with a radius as high as the pyramid would have a circumference very close in length to the pyramid’s perimeter.

The surface of the artwork captures the pyramids, the sky, the surroundings, and the viewers in a multiple fragmented reflection. It references the role of the circular mirror in historical Egyptian symbolism, where it was linked to the sun and conveyed notions of creation and rebirth.

FOREVER IS NOW .02 54

ةﺮﺋاﺪﻟا نأ ﺚﻴﺣ ،ﻲــﺳﺪﻨﻬﻟا ﺞﺗﺎﻨﻟا ﻲــﻓ ﺎﻴﺋﺮﻣ ﺮﻴﻏ ﺎــﺋﺰﺟ ةﺮــﺋاﺪﻟا ﻞﻜــﺸﺗ اﺪﺟ ﺎﻬﻄﻴﺤﻣ لﻮــﻃ بﺮﺘﻘﻴــﺳ مﺮﻬﻟا عﺎﻔﺗرا ﺎﻫﺮﻄﻗ ﻒــﺼﻧ ﻎــﻠﺒﻳ ﻲــﺘﻟا مﺮﻬﻟا ﻂﻴﺤﻣ ﻦــﻣ راﻮﺠﻟاو ءﺎﻤــﺴﻟاو تﺎﻣاﺮﻫ ا ،ﻲﻨﻔﻟا ﻞــﻤﻌﻟا ﺢﻄــﺳ ﻰﻠﻋ ﺮــﻬﻈﻳ ﻰﻟإ ﻚﻟﺬﺑ اﺮﻴــﺸﻣ ،ﺔﻔﻋﺎﻀﺘﻣو ﺔــﺋﺰﺠﻣ تﺎــﺳﺎﻜﻌﻧا ﻲﻓ ﻦﻳﺪﻫﺎــﺸﻤﻟاو ﺎﻬﻄﺑر ﻢﺗ ﺚــﻴﺣ ،ﺔﻴﺨﻳرﺎﺘﻟا

ART D’ÉGYPTE 55 ،ﻪﺑ ﻂﻴﺤﻤﻟا ﻢــﻳﺪﻘﻟا ﺮﺼﻣ ﺦــﻳرﺎﺗ ﻦﻣ ﻪﻣﺎﻬﻟإ ( راﺪــﻤﻟا ) " بروأ " ﺪﻤﺘــﺴﻳ ﺎﻌﺟﺮﻣ ﺔﻌﻄﻘﻟا ﻲــﻓ ﺔﻣﺪﺨﺘــﺴﻤﻟا داﻮﻤﻟاو ﻞﻜــﺸﻟا رﺎﻴﺘﺧا ﺮــﺒﺘﻌﻳ ﺚــﻴﺣ ﺔﻳﺮﺼﻤﻟا ﺔــﻓﺎﻘﺜﻟا ﻲﻓ ةدﻮﺟﻮﻤﻟا ﺔــﻳﺰﻣﺮﻟاو تﺎــﻴﺿﺎﻳﺮﻟا ﺮــﺻﺎﻨﻌﻟ اﺮــﺷﺎﺒﻣ صﻮﺼﺨﻟا ﻪﺟو ﻰــﻠﻋ تﺎﻣاﺮﻫ ا ﻲﻓو ﺔــﻤﻳﺪﻘﻟا ،تﺎﻣاﺮﻫ ا ﺔــﺳﺪﻨﻫ ﻲﻓ ﻦﻣﺎﻜﻟا " ط " ﻢﻗر ﻰــﻟإ ﺔﻌﻄﻘﻟا ﻞﻜــﺷ ﺮﻴــﺸﻳ . ﻪﻋﺎﻔﺗرا ﻒﻌﺿ ﻰــﻠﻋ

ﺪﻨﻋ

ﺔــﻳﺮﺼﻤﻟا زﻮﻣﺮﻟا ﻲــﻓ ﺔــﻳﺮﺋاﺪﻟا ةآﺮــﻤﻟا رود ﺚﻌﺒﻟاو ﻖﻠﺨﻟا ﻢــﻴﻫﺎﻔﻣ ﺖــﻠﻘﻧو ﺲﻤــﺸﻟﺎﺑ يﺎــﺒﺳ ﺲﻤﺸـﻟا ﺲـﻔﻧ ﺖـــﺤﺗ : راﺪﻣ موﺮﻜﻟﺎﺑ ىﻮﻘﻣ ﺐــﻠﺻ ،ﺐﻠﺻ ( ﺮﻄﻗ ) م٤ ٢٠٢٢ Thanks to ﺮﻜــﺸﻳ نﺎﻨﻔﻟا

مﺮﻬﻟا ﻂﻴﺤﻣ ﺔﻤــﺴﻗ

ﻪــﻴﻟإ لﻮﺻﻮﻟا ﻢــﺗ يﺬــﻟاو

SpY

O RB : U NDER THE SA ME S UN

Photo: MO4 Network

Photo: MO4 Network

يﺎــﺒﺳ ﺲﻤﺸـﻟا ﺲـﻔﻧ ﺖـــﺤﺗ : راﺪﻣ

SpY is an international public and urban artist whose work consist s of transforming spaces into experiences through artistic interventions. The contextual art projects of Spanish artist SpY are among the most original and talked-about contributions in the evolution from urban art to public art. Throughout his career, SpY’s practice has developed into an increasingly spectacular body of large-scale installations and interventions, ever more ambitious and impactful, produced in cities across the world.

SpY interpellates viewers while engaging them as active subjects in the artistic process. He works with incisive concepts and strong formal approaches, raising substantial questions about the reality of human relations. His projects dialogue with the urban environment, disrupt its daily routines, and explore it as a playing field full of untapped possibilities.

SpY designs and produces his artistic projects from his platform SpY Studio. The studio is both a laboratory space and an eclectic team of technical specialists and craftsmen and is known for an unparalleled ability for bringing to life alluring and formally solid artistic experiences.

FOREVER IS NOW .02 58

ﻦﻣو ،ﺔﻳﺮﻀﺤﻟاو ﺔــﻣﺎﻌﻟا ﻦﻛﺎﻣ ا ﻲــﻓ ﻞﻤﻌﻳ ﻲﻟود نﺎﻨﻓ ﻮــﻫ يﺎﺒــﺳ ﻦﻣ ﺔﻋﻮﻨﺘﻣ برﺎــﺠﺗ ﻰﻟإ ﺔﻏرﺎﻔﻟا تﺎﺣﺎــﺴﻤﻟا لﻮﺤﻳ ﻮــﻬﻓ ﻪــﻠﻤﻋ لﻼــﺧ . ﺔﻴﻨﻔﻟا تﻼــﺧﺪﺘﻟا لﻼﺧ ،ﺔﻔﻠﺘﺨﻣ تﺎﻗﺎﻴــﺳ ﻰﻟإ ةﺪﻨﺘــﺴﻤﻟا ،يﺎﺒــﺳ ﻲﻧﺎﺒــﺳ ا نﺎﻨﻔﻟا ﻊﻳرﺎــﺸﻣ ﺪﻌﺗ لﻮﺤﺘﻟا ﺺﺨﻳ ﺎــﻤﻴﻓ ﻻواﺪﺗ ﺮﺜﻛ او ﺔــﻟﺎﺻأ ﺮﺜﻛ

ﺔــﻴﻄﻤﻧ

،ﺔــﻳﺮﻀﺤﻟا ﺔﺌﻴﺒﻟا روﺎــﺤﺗ ﻪﻌﻳرﺎــﺸﻣ ﺔﻴﻧﺎــﺴﻧ ا . ﺔﻠﻐﺘــﺴﻤﻟا ﺮﻴﻏ تﺎﻴﻧﺎﻜﻣ ﺎﺑ ءﻲــﻠﻣ لﺎــﺠﻤﻛ ﺎﻬﻔــﺸﻜﺘﺴﺗو ﻮﻫو ، " يﺎﺒــﺳ ﻮﻳﺪﺘــﺳ ” ﻪﺘﺼﻨﻣ ﻦﻣ ﺔﻴﻨﻔﻟا ﻪﻌﻳرﺎــﺸﻣ ﺞﺘﻨﻳو يﺎﺒــﺳ ﻢــﻤﺼﻳ ﻦﻴﻴﻨﻘﺘﻟا ﻦــﻴﺼﺼﺨﺘﻤﻟا ﻦــﻣ ﻲﺋﺎﻘﺘﻧا ﻖــﻳﺮﻓو ﺔﻴﻠﻤﻌﻣ ﺔﺣﺎــﺴﻣ ﻦــﻋ ةرﺎــﺒﻋ ﻰﻠﻋ ﺎﻬﻟ ﻞــﻴﺜﻣ ﻻ ةرﺪﻘﺑ ﻦﻴﻓوﺮﻌﻤﻟاو ،ﺖــﻗﻮﻟا ﺲــﻔﻧ ﻲــﻓ ﻦــﻴﻴﻓﺮﺤﻟاو ﺔﺨــﺳار لﺎﻜــﺷأ تاذ ﺔﺑاﺬﺠﻟا ﺔﻴﻨﻔﻟا برﺎﺠﺘﻟا ءﺎــﻴﺣإ

Represented by ﻪﻠﺜﻤﻳ نﺎــﻨﻔﻟا

ART D’ÉGYPTE 59

ا تﺎﻤﻫﺎــﺴﻤﻟا ﻦــﻴﺑ ﻦــﻣ يﺎﺒــﺳ ﺔــﺳرﺎﻤﻣ ترﻮﻄﺗ ﺔﻣﺎﻌﻟا ﻦﻛﺎﻣ ا ﻦﻓ ﻰﻟإ يﺮﻀﺤﻟا ﻦــﻔﻟا ﻦــﻣ ﻦﻣ ﺔﻠﻫﺬﻣ ﺔــﻋﻮﻤﺠﻣ ﻰﻟإ ،ﺎﻣﺎﻋ ﻦﻳﺮــﺸﻋ ﻦﻣ ﺮﺜﻛأ ىﺪــﻣ ﻰــﻠﻋ ،ﻦــﻔﻠﻟ ﺮﺜﻛأ ﺖﺤﺒﺻأ ﻲــﺘﻟاو ،تﻼﺧﺪﺘﻟاو ، ( ﻦــﺸﻴﻠﺘﺴﻧا ) غاﺮﻔﻟا ﻲــﻓ تاﺰــﻴﻬﺠﺘﻟا ﺔﻔﻠﺘﺨﻣ نﺪــﻣ ﻲﻓ ﺎﻬﺿﺮﻋ ﻢــﺗ ﺪﻗو ،ﻰﻀﻣ ﺖﻗو يأ ﻦــﻣ اﺮــﻴﺛﺄﺗو ﺎــﺣﻮﻤﻃ داﺮﻓﺄﻛ ﻦﻳﺪﻫﺎــﺸﻤﻟا كاﺮــﺷإ ﻰﻟإ يﺎﺒــﺳ فﺪﻬﻳ . ﻢﻟﺎﻌﻟا ءﺎﺤﻧأ ﻊﻴﻤﺟ ﻲــﻓ ﺞﻫﺎﻨﻣو ﺔﺒﻗﺎﺛ ﻢــﻴﻫﺎﻔﻤﺑ ﻞــﻤﻌﻳ ﺚﻴﺣ ،ﺔﻴﻨﻔﻟا ﺔــﻴﻠﻤﻌﻟا ﻲــﻓ ﻦﻴﻄــﺷﺎﻧ تﺎﻗﻼﻌﻟا ﻊﻗاو لﻮــﺣ ﺔﻳﺮﻫﻮﺟ ﺔﻠﺌــﺳأ ﻚﻟﺬﺑ اﺮﻴﺜﻣ ،ﺔﺨــﺳارو

،ﻲﻣﻮﻴﻟا ﺎﻬﻨﻴﺗور ﻞــ ﱢ ﻄﻌﺗو

T HERESE A NTOINE PANTHEONS OF D EITIES

Marble, PLA, steel 8 m x 8 m x 4.5 m 2022

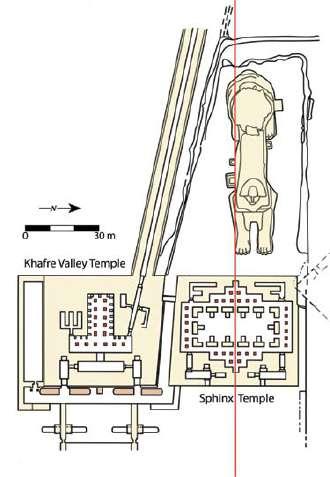

‘There is a strong relationship at the Giza Plateau between the human body and the space itself where human beings stand in connection to nature and the cosmos, and it is TIME that connects everything at this specific location.

I designed the layout of a space represented by a circular plan that refers to a sundial, an instrument used in the past to indicate time by using a light spot or shadow cast by the position of the sun on a reference scale. Taking the concept of the sundial for my installation as a metaphor, I link between the sun, the earth, and the passage of time.

By creating five vertical columns influenced by the ancient obelisk—one at the centre of the circular shape and four at the edge of the outline—I reference the principal points indicating time and the cardinal directions (compass). Only three different shapes are repeated, symbolizing the number of the Great Pyramids of Giza. Those columns represent several significant deities of the Old Kingdom. The first is Ra, the king of the deities, the father of all creation, and the patron of the sun; hence, I chose that the main column be symbolised by the sun disk. The second is Maat, the goddess of truth and the representation of the stability of the universe. Her symbol is the ostrich feather. The third is Osiris, the god of the underworld and of resurrection, symbolised by his Atef crown. Next comes Isis, the queen of gods and the goddess of maternity and birth, symbolised by the throne. And finally, there is Horus, the god of heaven and protection represented by the double crown.

By producing a repetitive production of each form and by showcasing them in an unsystematic and unorganised way, I created a dynamic composition which will help in designing a layout of a new dimension of the space and in building an interactive environment between the audience and the space itself.’

The artist would like to acknowledge and thank for their support in the realisation of this project.

FOREVER IS NOW .02 60

ﺔﻣﺪﺨﺘــﺴﻣ ةادأ

ﺔﻴــﺴﻤﺸﻟا ﺔﻋﺎــﺴﻟا مﻮﻬﻔﻣ تﺬﺧأ . ﻲﻌﺟﺮﻣ سﺎــﻴﻘﻣ ﻰﻠﻋ ﺲﻤــﺸﻟا ﻊــﻗﻮﻣ ﺐــﺴﺣ . ﻦﻣﺰﻟا روﺮﻣو ضر او ﺲﻤــﺸﻟا ﻦﻴﺑ ﻂﺑرو ةرﺎﻌﺘــﺳا ﺎــﻬﻧأ ﻰــﻠﻋ ( ﻦــﺸﻴﻠﺘﺴﻧ ا ) ﻲﻠﻴﻜــﺸﺘﻟا ﻞﻜــﺸﻟا ﻂــﺳو ﻲﻓ ﺎﻫﺪﺣأ : ﺔﻤﻳﺪﻘﻟا ﺔﻠــﺴﻤﻟﺎﺑ اﺮﺛﺄﺗ ﺔﻴــﺳأر ةﺪﻤﻋأ ﺔــﺴﻤﺧ ﺖﻌﻨﺻ ﺪﻘﻟ ﺖﻗﻮﻟا ﻰﻟإ ﺮﻴــﺸﺗ ﻲﺘﻟا ﺔﻴــﺴﻴﺋﺮﻟا طﺎﻘﻨﻟا ﻰﻟإ ةرﺎــﺷإ ﻲﻓ ﻂﻄﺨﻤﻟا ﺔــﻓﺎﺣ ﺪــﻨﻋ ﺔــﻌﺑرأو يﺮــﺋاﺪﻟا دﺪﻋ ﻰﻟإ ﺰﻣﺮﺗ ﻂــﻘﻓ ﺔﻔﻠﺘﺨﻣ لﺎﻜــﺷأ ﺔﺛﻼﺛ راﺮﻜﺗ ﻢــﺘﻳ .( ﺔــﻠﺻﻮﺒﻟا )

ART D’ÉGYPTE 61 ﻒﻘﻳ ﺚﻴﺣ ،ﻪــﺴﻔﻧ نﺎﻜﻤﻟاو نﺎــﺴﻧ ا ﻢــﺴﺟ ﻦﻴﺑ ةﺰﻴﺠﻟا ﺔﺒﻀﻫ ﻲﻓ ﺔــﻳﻮﻗ ﺔــﻗﻼﻋ كﺎــﻨﻫ " اﺬﻫ ﻲﻓ ءﺎﻴــﺷ ا ﻞﻛ ﻂﺑﺮﻳ يﺬﻟا ﻮﻫ ﻦﻣﺰﻟاو ،نﻮــﻜﻟاو ﺔﻌﻴﺒﻄﻟا ﻊــﻣ ﻞﺻاﻮﺗ ﺔــﻟﺎﺣ ﻲــﻓ ﺮــﺸﺒﻟا تاﺬﻟﺎﺑ ﻊﻗﻮﻤﻟا ﻲﻫو ،ﺔﻴــﺴﻤﺷ ﺔﻋﺎــﺳ ﻰﻠﻋ لﺪﻳ يﺮﺋاد ﻞﻜــﺷ ﻲﻓ ﻞﺜﻤﺘﻳ نﺎﻜﻤﻟ ﺎــﻄﻴﻄﺨﺗ ﺖــﻤﻤﺻ ﺪــﻘﻟ نﻮﻜﺘﻳ ﻞﻇ وأ ءﻮــﺿ ﺔﻌﻘﺑ ماﺪﺨﺘــﺳﺎﺑ ﺖﻗﻮﻟا ﻰﻟإ ةرﺎــﺷ ﻟ ﻲــﺿﺎﻤﻟا ﻲــﻓ

ﺔﻴــﺳﺎﺳ ا

. ﺔﻤﻳﺪﻘﻟا ﺔــﻟوﺪﻟا ﺔﻬﻟآ ﻦﻣ ﺪﻳﺪﻌﻟا ةﺪــﻤﻋ ا هﺬﻫ ﻞﺜﻤﺗ ﺚــﻴﺣ ،ﺔــﻤﻴﻈﻌﻟا ةﺰــﻴﺠﻟا تﺎــﻣاﺮﻫأ دﻮﻤﻌﻟا ﺰﻣﺮﻳ

عر ﻮــﻫ لو ا ،نﻮﻜﻟا راﺮﻘﺘــﺳا ﻞﺜﻤﺗ ﻲﺘﻟاو ﺔــﻘﻴﻘﺤﻟا ﺔﻬﻟإ ،ﺖــﻋﺎﻣ ﻮﻫ ﻲﻧﺎﺜﻟاو ،ﺲﻤــﺸﻟا صﺮــﻗ ﻰــﻟإ ﻲــﺴﻴﺋﺮﻟا ﻪﻟ ﺰﻣﺮﻳو ،ﺔﻣﺎﻴﻘﻟاو ﻲﻠﻔــﺴﻟا ﻢــﻟﺎﻌﻟا ﻪﻟإ ،ﺲﻳروزوأ ﻮﻬﻓ ﺚــﻟﺎﺜﻟا ﺎﻣأ ،مﺎﻌﻨﻟا ﺔــﺸﻳر ﻮــﻫ ﺎــﻫﺰﻣرو ﺎﻬﻴﻟإ ﺰﻣﺮﻳو ،ةدﻻﻮــﻟاو ﺔﻣﻮﻣ ا ﺔﻬﻟإو ﺔــﻬﻟ ا ﺔﻜﻠﻣ ،ﺲﻳﺰﻳإ ﻚــﻟذ ﺪﻌﺑ ﻲﺗﺄﺗ ﺾــﻴﺑ ا ﻒــﺗأ جﺎــﺘﺑ جودﺰﻤﻟا جﺎﺘﻟا ﻪــﻠﺜﻤﻳ يﺬﻟا ﺔﻳﺎﻤﺤﻟاو ءﺎﻤــﺴﻟا ﻪﻟإ ،سرﻮــﺣ كﺎﻨﻫ ،اﺮــﻴﺧأو ،شﺮــﻌﻟﺎﺑ ،ﺔﻤﻈﻨﻣ ﺮــﻴﻏو ﺔﻴﺠﻬﻨﻣ ﺮــﻴﻏ ﺔﻘﻳﺮﻄﺑ ﻪــﺿﺮﻋو ﻞﻜــﺷ ﻞﻜﻟ رﺮﻜﺘﻣ جﺎﺘﻧإ لﻼﺧ ﻦــﻣ ،ﺖــﻤﻗ ﺪــﻘﻟ ﻲﻓو نﺎﻜﻤﻠﻟ اﺪــﻳﺪﺟ اﺪﻌﺑ ﻲﻄﻌﺑ ﻂــﻄﺨﻣ ﻢﻴﻤﺼﺗ ﻲــﻓ ﺪﻋﺎــﺴﺘﺳ ﺔــﻴﻜﻴﻣﺎﻨﻳد ﺔــﺒﻴﻛﺮﺗ ءﺎــﺸﻧﺈﺑ ". ﻪــﺴﻔﻧ نﺎﻜﻤﻟاو رﻮﻬﻤﺠﻟا ﻦــﻴﺑ ﺔﻴﻠﻋﺎﻔﺗ ﺔــﺌﻴﺑ ءﺎــﻨﺑ . عوﺮــﺸﻤﻟا ﻖﻴﻘﺤﺗ ﻲﻓ ﺎﻬﻤﻋد ﻰﻠﻋ ﻞﻴﻧﻮﻣرﺎﻣ ﺔﻛﺮــﺷ ﺮﻜــﺸﺗ نأ ﺔﻧﺎﻨﻔﻟا دﻮﺗ نﻮــﻄـﻧأ ﺰــــﻳﺮـﺗ ﺔﻬــﻟ ا ﺔــــﺒـﻛﻮــﻛ ﺐﻠﺻ ،PLA ،ﺮﺠﺣ م٤،٥ × م٨ × م٨ ٢٠٢٢

ﻲﻠﻤﻌﻟ

تﺎــﻫﺎﺠﺗﻻاو

نأ تﺮــﺘﺧا ﻢﺛ ﻦﻣو ،ﺲﻤــﺸﻟا ﻲﻋارو ﺔﻘﻴﻠﺨﻟا ﻮــﺑأو ﺔــﻬﻟ ا ﻚــﻠﻣ

T HERESE A NTOINE

PA NTHE O NS OF D EITIES

Photo: MO4 Network

Photo: MO4 Network

نﻮــﻄـﻧأ ﺰــــﻳﺮـﺗ ﺔﻬــﻟ ا ﺔــــﺒـﻛﻮــﻛ

Therese Antoine is an Egyptian sculptor who lives and works in Alexandria, Egypt. The ability to transform a symmetrical, streamlined body shape into simple abstract, geometrical forms and fgures has always been a great fascination of hers. Lately, she has been intrigued by the concept of the abstraction of the human form as a result of its own psychological infuences and by focusing on the idea of self-documentation of the very personal psychological phases and stages. Uniform repetition, daring confrontation, and issues of identity are the major subjects and tools she employs in her work.

She obtained her BFA in Monumental Sculpture from the Faculty of Fine Arts in Alexandria in 2014. Before completing her BFA, she was part of Mass Alexandria 2013, an independent study program for contemporary arts. After her graduation, she took part in the Aswan International Sculpture Symposium, AISS 20. Two years later, she was selected to be one of the main artists of the Egyptian Delegation at AISS 22. In 2018, Antoine held a solo exhibition at the Institut Francais d’Alexandrie, and a year later, she received an artist residency scholarship at the Cité internationale des arts in Paris from the Institut Français d’Égypte. In 2020, she was selected by the Institut Français d’Alexandrie to hold an exhibition inspired by life during the pandemic.

Antoine has received numerous awards and prizes, including the frst prize at the Adam Henein inaugural competition in 2022. She was subsequently granted an artist residency at the Adam Henein Museum after participating in the second edition and a residency at the Egyptian Academy in Rome after her participation at the 28th Youth Salon. She has exhibited across Egypt and internationally in France, Italy, Ghana, and Lithuania.

FOREVER IS NOW .02

64

ﺎﻬﺗﺮﺤــﺳ ﺎﻤﻟﺎﻃ ﺔﻳرﺪﻨﻜــﺳ ا ﻲﻓ ﻞﻤﻌﺗو ﺶﻴﻌﺗ ﺔــﻳﺮﺼﻣ ﺔﺗﺎﺤﻧ نﻮــﻄﻧأ ﺰــﻳﺮﺗ ﺔﻳﺪﻳﺮﺠﺗ لﺎﻜــﺷأ ﻰﻟإ ﻲﺑﺎﻴــﺴﻧﻻاو ﻖــﺳﺎﻨﺘﻤﻟا ﻢــﺴﺠﻟا ﻞﻜــﺷ ﻞﻳﻮﺤﺗ ﺔﻴﻧﺎﻜﻣإ ﺔﺠﻴﺘﻧ يﺮــﺸﺒﻟا ﻞﻜــﺸﻟا ﺪﻳﺮﺠﺗ مﻮﻬﻔﻤﺑ ،ةﺮــﻴﺧ ا ﺔﻧو ا ﻲﻓ ،ﺖــﻨﺘﻓ . ﺔﻴــﺳﺪﻨﻫو ﻲﺗاﺬﻟا ﻖﻴﺛﻮﺘﻟا ةﺮــﻜﻓ ﻰﻠﻋ ﺰــﻴﻛﺮﺘﻟا لﻼﺧ ﻦﻣو ،ﻪــﺑ ﺔــﺻﺎﺨﻟا ﺔﻴــﺴﻔﻨﻟا ﻪــﺗاﺮﻴﺛﺄﺘﻟ تاود او تﺎﻋﻮﺿﻮﻤﻟا ﻞــﺜﻤﺘﺗ اﺪﺟ ﺔﻴﺼﺨــﺸﻟا ﺔﻴــﺴﻔﻨﻟا راﻮﻃ او ﻞــﺣاﺮﻤﻠﻟ ﺔﺌﻳﺮﺠﻟا ﺔــﻬﺟاﻮﻤﻟاو ﻖﺑﺎﻄﺘﻤﻟا راﺮــﻜﺘﻟا ﻲﻓ ﺎــﻬﻠﻤﻋ ﻲﻓ ﺎﻬﻣﺪﺨﺘــﺴﺗ

تﺮــﻴﺘﺧا نﻮﻄﻧأ ﺖﻣﺎﻗأ ٢٠١٨ مﺎــﻋ ﻦﻳﺮــﺸﻌﻟاو ﻲﻧﺎﺜﻟا ﻲﻟوﺪﻟا ﺖــﺤﻨﻟا مﻮﻳزﻮﺒﻤــﺳ ﻲــﻓ

ﺪﻌﺑ ﺖﻠﺼﺣو ،ﺔﻳرﺪﻨﻜــﺳ ﺎﺑ ﻲــﺴﻧﺮﻔﻟا ﻲﻓﺎﻘﺜﻟا ﺪــﻬﻌﻤﻟا ﻲــﻓ ادﺮــﻔﻨﻣ ﺎــﺿﺮﻌﻣ ﻞﺒﻗ ﻦﻣ ،ﺲﻳرﺎﺒﺑ " نﻮــﻨﻔﻠﻟ ﺔــﻴﻟوﺪﻟا ﺔﻨﻳﺪﻤﻟا " ﻲــﻓ ﺔﻴﻨﻓ ﺔﻣﺎﻗإ ﺔــﺤﻨﻣ ﻰــﻠﻋ مﺎــﻌﺑ ﺪﻬﻌﻤﻟا ﻞــﺒﻗ ﻦﻣ ﺎﻫرﺎﻴﺘﺧا ﻢــﺗ ،٢٠٢٠ مﺎﻋ ﻲﻓ . ﺮــﺼﻤﺑ ﻲــﺴﻧﺮﻔﻟا ﻲــﻓﺎﻘﺜﻟا ﺪــﻬﻌﻤﻟا ءﺎﺑﻮﻟا ءﺎﻨﺛأ ةﺎــﻴﺤﻟا ﻦﻣ ﻰﺣﻮﺘــﺴﻣ ضﺮﻌﻣ ﺔــﻣﺎﻗ ﺔﻳرﺪﻨﻜــﺳ ﺎﺑ ﻲــﺴﻧﺮﻔﻟا ﻰﻟو ا ةﺰﺋﺎﺠﻟا ﻚــﻟذ ﻲﻓ ﺎﻤﺑ ،ﺢﻨﻤﻟاو ﺰــﺋاﻮﺠﻟا ﻦﻣ ﺪﻳﺪﻌﻟا ﻰــﻠﻋ نﻮــﻄﻧأ ﺖــﻠﺼﺣ ﻲﻓ ﺔﻴﻨﻓ ﺔــﻣﺎﻗإ ﺎﻘﺣﻻ ﺖﺤﻨﻣو ٢٠٢٢ مﺎــﻋ ﻲﻓ ﻦﻴﻨﺣ مدآ ﺔﻘﺑﺎــﺴﻣ ﻦﻴــﺷﺪﺗ ﻲــﻓ ﺎﻤﻛ . ﺔﻘﺑﺎــﺴﻤﻟا ﻦﻣ ﺔﻴﻧﺎﺜﻟا ﺔﺨــﺴﻨﻟا ﻲﻓ ﺎﻬﺘﻛرﺎــﺸﻣ ﺪــﻌﺑ ﻦــﻴﻨﺣ مدآ ﻒــﺤﺘﻣ نﻮﻟﺎﺻ ﻲﻓ ﺎﻬﺘﻛرﺎــﺸﻣ ﺪﻌﺑ ﺎــﻣوﺮﺑ

ART D’ÉGYPTE 65

ﻲــﺘﻟا ﺔﻴــﺴﻴﺋﺮﻟا ﺔﻳﻮﻬﻟا ﺎــﻳﺎﻀﻗو ﺔﻴﻠﻛ ﻦﻣ ﺔــﻤﺨﻀﻟا تﺎﺗﻮﺤﻨﻤﻟا ﻲــﻓ ﺔﻠﻴﻤﺠﻟا نﻮــﻨﻔﻟا سﻮــﻳرﻮﻟﺎﻜﺑ ﻰــﻠﻋ ﺖــﻠﺼﺣ ﺔﻳرﺪﻨﻜــﺳا " سﺎﻣ " ﻦﻣ اءﺰﺟ ﺖﺤﺒﺻأ .٢٠١٤ مﺎــﻋ ﺔﻳرﺪﻨﻜــﺳ ﺎﺑ ﺔــﻠﻴﻤﺠﻟا نﻮــﻨﻔﻟا نﻮﻨﻔﻠﻟ ﻞﻘﺘــﺴﻣ ﺔــﺳارد ﺞﻣﺎﻧﺮﺑ ﻮﻫو ،سﻮﻳرﻮﻟﺎﻜﺒﻟا ﻰــﻠﻋ ﺎﻬﻟﻮﺼﺣ ﻞــﺒﻗ ٢٠١٣ ﻲــﻓ ﻢﺛ ،ﺖﺤﻨﻠﻟ ﻲــﻟوﺪﻟا ناﻮــﺳأ مﻮﻳزﻮﺒﻤــﺳ ﻲﻓ ،ﺎﻬﺟﺮﺨﺗ ﺪﻌﺑ ،ﺖﻛرﺎــﺷ ةﺮــﺻﺎﻌﻤﻟا يﺮﺼﻤﻟا ﺪﻓﻮﻟا ﻲــﻓ ﻦﻴﻴــﺴﻴﺋﺮﻟا ﻦﻴﻧﺎﻨﻔﻟا ﻦــﻣ ةﺪﺣاو نﻮﻜﺘﻟ ﻦــﻴﻣﺎﻋ ﺪــﻌﺑ

ﺮﺼﻣ ءﺎﺤﻧأ ﻊــﻴﻤﺟ ﻲﻓ ﺎﻬﻟﺎﻤﻋأ ﺖــﺿﺮﻋ ﻦﻳﺮــﺸﻌﻟاو ﻦــﻣﺎﺜﻟا بﺎﺒــﺸﻟا ﺎﻴﻧاﻮﺘﻴﻟو ﺎــﻧﺎﻏو ﺎﻴﻟﺎﻄﻳإو ﺎــﺴﻧﺮﻓ ﻲﻓ ﻲــﻟوﺪﻟا

ﻚﻟذ

ﺔﻳﺮﺼﻤﻟا ﺔﻴﻤﻳدﺎﻛ ا ﻲــﻓ ﺔــﻣﺎﻗإ ﻰــﻠﻋ ﺖــﻠﺼﺣ ﺪﻴﻌﺼﻟا ﻰــﻠﻋو

ZEINA B A LHASHEMI

C AMOULFLAGE 1.618: T HE U NFINISHED OB ELISK

Reinforced metal rods, camel hides 6 m x 1 m x 1 m 2022

‘Camoulfage’ is a portmanteau, a combination of the words ‘camel’ and ‘camoufage’, inspired by the history and legacy of the camel in the region and the way the animals blend with the desert dunes. The installation strikes the audience as a desert scene from which an abstract camel silhouette emerges. Just as the animal’s natural colouring and form enable it to blend in with its surroundings, so too does the installation meld with its desert backdrop, almost mimicking ancient Egyptian artefacts. In this work, the camels have transformed into an obelisk, revisiting the story of the Unfnished Obelisk in Aswan. In Egyptian mythology, the obelisk symbolised the sun god Ra. The unfnished obelisk is the largest known ancient obelisk and is located in the northern region of the stone quarries of Aswan.

The body of this obelisk is in shades of natural camel hair from different carefully selected camel breeds. Reinforced metal rods, used in all modern construction, are used in mesh form in the obelisk, refecting a scene we witness every day in our modern lives and cities, that of half-done buildings and skeletons of future landscapes.

Camoulfage 1.618 is part of the Camoulfage series and is named after the golden ratio, a special number approximately equal to 1.618 that appears many times in mathematics, geometry, art, architecture and especially in nature. The Great Pyramid of Giza reveals that the positions and relative sizes of the pyramids may be based on the golden ratio. Evidence of the Golden Ratio in the Great Pyramid has been a complex mystery, hence the title Camoulfage 1.618 .

The artist would like to thank Fairouz and Jean Paul Villain; Mana Jalalian and Rami Chedid; Yulia Korienkova; Bahar Goldooz Hassani; Alejandra Castro and Frederic Janssen; and Her Excellency Noura Al Kaabi and the Ministry of Culture and Youth.

FOREVER IS NOW .02 66

) ةدﺮﺠﻣو ﺔــ ّ ﻴﻠﻇ ﻞﻤﺟ ةرﻮﺻ ﻪﻨﻣ ﻖــﺜﺒﻨﺗ ﺎــﻳواﺮﺤﺻ اﺪﻬــﺸﻣ هرﺎــﺒﺘﻋﺎﺑ ﻊﻣ ( ﻦــﺸﻴﻠﺘﺴﻧﻻا ) جﺰﺘﻤﻳ ﻚــﻟﺬﻛ ،ﻪﻄﻴﺤﻤﺑ جﺎــﻣﺪﻧﻻا ﻦﻣ ﻪﻠﻜــﺷو ناﻮﻴﺤﻠﻟ ﻲــﻌﻴﺒﻄﻟا نﻮــﻠﻟا . ﺔﻤﻳﺪﻘﻟا ﺔــﻳﺮﺼﻤﻟا ﺔﻴﻨﻔﻟا ﻊــﻄﻘﻟا اﺪــﻠﻘﻣ ،ﺔــﻳواﺮﺤﺼﻟا ﻪــﺘﻴﻔﻠﺧ ﺔﻠﻤﺘﻜﻤﻟا

اﺬﻫ ﻲــﻓ ،لﺎــﻤﺠﻟا ﺖــﻟﻮﺤﺗ ﺮﻴﻏ ﺔﻠــﺴﻤﻟا ﻊﻘﺗو ،عر ﺲﻤــﺸﻟا ﻪﻟإ ﻰﻟإ ،ﺔﻳﺮﺼﻤﻟا ﺮﻴﻃﺎــﺳ ا ﻲﻓ ،ﺔﻠــﺴﻤﻟا ﺰﻣﺮﺗ ناﻮــﺳأ ﻲﻓ ﺔﻓوﺮﻌﻣ ﺔﻤﻳﺪﻗ ﺔﻠــﺴﻣ ﺮﺒﻛأ ﻲــﻫو ،ناﻮــﺳأ ﺮﺟﺎﺤﻣ ﻦﻣ ﺔﻴﻟﺎﻤــﺸﻟا ﺔــﻘﻄﻨﻤﻟا ﻲــﻓ ﺔــﻠﻤﺘﻜﻤﻟا

ART D’ÉGYPTE 67 ،ﻞﻤﺟ ) يأ ، "Camouflage " و "Camel ” ﻲﺘﻤﻠﻛ ﻦــﻣ نﻮﻜﺘﻳ ،ﻲــﻧاﺮﺘﻗا ﻆﻔﻟ ﻦــﻋ ةرﺎــﺒﻋ ، " جﻼــﻔﻟﻮﻣﺎﻛ " ﻰﻫﺎﻤﺘﺗ ﻲــﺘﻟا ﺔﻘﻳﺮﻄﻟاو ﺔــﻘﻄﻨﻤﻟا ﻲﻓ ﻞﻤﺠﻟا ثرإو ﺦــﻳرﺎﺗ ﻦﻣ ةﺎﺣﻮﺘــﺴﻣ ﻲــﻫو ، ( ﻪــﻳﻮﻤﺗو رﻮﻬﻤﺠﻟا ( ﻦــﺸﻴﻠﺘﺴﻧﻻا ) غاﺮــﻔﻟا ﻲﻓ ﺰﻴﻬﺠﺘﻟا ﻒﻗﻮﺘــﺴﻳ ءاﺮﺤﺼﻟا نﺎــﺒﺜﻛ ﻊــﻣ تﺎــﻧاﻮﻴﺤﻟا ﺎــﻬﻴﻓ ﻦ ّ ﻜﻤﻳ ﺎﻤﻛو .( ﺖﻳﻮﻠــﺳ

ﺮــﻴﻏ ﺔﻠــﺴﻤﻟا ﺔﺼﻗ ﻰﻠﻋ ءﻮﻀﻟا ءﺎــﻘﻟ ﺔﻠــﺴﻣ ﻰﻟإ ،ﻞﻤﻌﻟا

ﺔﻔﻠﺘﺨﻣ

ﺎــﻨﺗﺎﻴﺣ ﻲــﻓ ﺔﻴﻌﻴﺒﻄﻟا ﺮــﻇﺎﻨﻤﻟا ﻞﺒﻘﺘــﺴﻤﻟ صﺎﺧ ﻢﻗر ﻮﻫو ،ﺔﻴﺒﻫﺬﻟا ﺔﺒــﺴﻨﻟا ﻢــﺳﺎﺑ ﻲﻤــﺳو ، " جﻼﻔﻟﻮﻣﺎﻛ " ﺔﻠــﺴﻠﺳ ﻦﻣ ءﺰﺟ ﻞــﻤﻌﻟا اﺬــﻫ ﻞﻜــﺸﺑو ةرﺎﻤﻌﻟاو ﻦﻔﻟاو ﺔــﺳﺪﻨﻬﻟاو تﺎﻴﺿﺎﻳﺮﻟا ﻲﻓ تاﺮــﻣ ةﺪﻋ ﺮــﻬﻈﻳ ،١٫٦١٨ ﺎــﺒﻳﺮﻘﺗ يوﺎــﺴﻳ تﺎﻣاﺮﻫ ﻟ ﺔﻴﺒــﺴﻨﻟا مﺎﺠﺣ او ﻊــﺿاﻮﻤﻟا نأ ةﺰﻴﺠﻟﺎﺑ ﺮــﺒﻛ ا مﺮﻬﻟا ﻲﺣﻮﻳ ﺔــﻌﻴﺒﻄﻟا ﻲــﻓ صﺎــﺧ مﺮﻬﻟا ﻲﻓ ﺔﻴﺒﻫﺬﻟا ﺔﺒــﺴﻨﻟا ﻰــﻠﻋ ﻞﻴﻟﺪﻟا لﺰﻳ ﻢــﻟ ﺚﻴﺣ ،ﺔﻴﺒﻫﺬﻟا ﺔﺒــﺴﻨﻟا ﻰــﻠﻋ ﺔــﻴﻨﺒﻣ نﻮــﻜﺗ ﺪــﻗ ."١،٦١٨ جﻼﻔﻟﻮﻤﻟﺎﻛ " ﺔــﺗﻮﺤﻨﻤﻟا ناﻮــﻨﻋ ءﺎﺟ ﺎﻨﻫ ﻦﻣو ،اﺪــﻘﻌﻣ اﺰــﻐﻟ ﺮــﺒﻛ ا ﺎــﻴﻟﻮﻳ ؛ﺪﻳﺪــﺷ ﻲــﻣارو نﺎــﻴﻟﻼﺟ ﺎــﻧﺎﻣ ؛نﻼــﻴﻓ لﻮــﺑ نﺎــﺟو زوﺮــﻴﻓ ﺮﻜــﺸﺗ نأ ﺔــﻧﺎﻨﻔﻟا دﻮــﺗ ةﺮــﻳزﻮﻟا ﻲــﻟﺎﻌﻣو ؛ﻦــﺴﻧﺎﻳ ﻚــﻳرﺪﻳﺮﻓو وﺮﺘــﺳﺎﻛ ارﺪــﻧﺎﺨﻴﻟأ ؛ﻲﻨــﺴﺣ زوﺪــﻟﻮﺟ رﺎــﻬﺑ ؛ﺎــﻓﻮﻜﻧﺎﻳرﻮﻛ . بﺎﺒــﺸﻟاو ﺔــﻓﺎﻘﺜﻟا ةرازوو ،ﻲــﺒﻌﻜﻟاةرﻮﻧ ﻲــﻤـﺷﺎــﻬـﻟا ﺐﻨـــﻳز :١٫٦١٨ ج ﻼـــﻔﻟﻮـﻣﺎــﻛ ﺔــﻠﻤﺘﻜﻤﻟا ﺮـــﻴﻏ ﺔـــﻠﺴﻤﻟا لﺎﻤﺠﻟا دﻮﻠﺟ ،ﺔﻴﻧﺎــﺳﺮﺧ ﺔﻴﻧﺪﻌﻣ تﺎــﻣﺎﻋد م١ × م١ × م٦ ٢٠٢٢ Thanks to ﺮﻜــﺸﺗ ﺔﻧﺎﻨﻔﻟا

ﻞــﺑإ تﻻﻼــﺳ ﻦﻣ ﻲﻌﻴﺒﻄﻟا ﻞﺑ ا ﺮﻌــﺷ ﻦﻣ لﻼﻇ ﻦﻣ ﺔﻠــﺴﻤﻟا هﺬﻫ ﻢــﺴﺟ نﻮــﻜﺘﻳ ﻊﻴﻤﺟ ﻲﻓ ﺔﻠﻤﻌﺘــﺴﻤﻟا ﺔﺤﻠــﺴﻤﻟا ﺔﻴﻧﺪﻌﻤﻟا تﺎــﻣﺎﻋﺪﻟا مﺪﺨﺘــﺴﺗ . ﺔــﻳﺎﻨﻌﺑ ﺎــﻫرﺎﻴﺘﺧا ﻢــﺗ مﻮﻳ ﻞﻛ هاﺮﻧ اﺪﻬــﺸﻣ ﺲﻜﻌﻳ ﺎﻤﻣ ،ﺔﻠــﺴﻤﻟا هﺬﻫ ﻲﻓ ﻚﺑﺎــﺸﺘﻣ ﻞﻜــﺸﺑ ،ﺔﺜﻳﺪﺤﻟا تاءﺎــﺸﻧ ا ﺔﻌﻗﻮﺘﻤﻟا ﺔــﻀﻣﺎﻐﻟا ﻞﻛﺎــﻴﻬﻟاو ﺔﻠﻤﺘﻜﻤﻟا ﻒــﺼﻧ ﻲﻧﺎﺒﻤﻟا ﻞــﺜﻣ ،ﺎﻨﻧﺪﻣو ﺔــﺜﻳﺪﺤﻟا

ZEINA B A LHASHEMI CA M O UL F L AG E 1.618: T HE U N F INISHED OBELISK

Photo: MO4 Network

Photo: MO4 Network

ﻲــﻤـﺷﺎــﻬـﻟا ﺐﻨـــﻳز :١ ٫٦ ١ ٨ جﻼـﻔﻟﻮـﻣﺎــﻛ ﺔــﻠﻤﺘﻜﻤﻟا ﺮـــﻴﻏ ﺔـﻠﺴﻤﻟا

Zeinab Alhashemi is an Emirati conceptual artist based in Dubai. Since graduating from Zayed University with a BA in arts and science specialising in multimedia design, she has become known for her large-scale contemporary site-specifc installations. Alhashemi is fascinated with capturing the transformation of the UAE and examines the contrast and interdependence between the abstract, geometric shapes of urbanism and the organic forms associated with her country’s natural landscape. Since the days of Alhashemi’s childhood, the familiarity of traditional scenery and nature has largely been disturbed to facilitate the rise of the man-made. In her experimental installations, she searches for a new identity appropriate to the modern condition and deconstructs the viewers’ understanding of their surroundings, introducing an alternative point of view, and creating a new perception of that reality. Drawing inspiration from the natural topography of the UAE, Alhashemi experiments with a variety of materials to position the viewer over the intangible boundary between the natural and the artifcial. While colour and texture make her work reminiscent of the traditional landscape, such familiarity is disturbed by the striking contrast of industrial materials that remind the viewer of human interference. Alhashemi’s work captures the essence of her homeland today, striking a delicate balance between modernism and tradition in an unexpectedly harmonious coexistence. She has participated in numerous art fairs and festivals such as Sikka Art Fair, Dubai Design Week, and Sharjah Biennial 11 and was recently commissioned by the Institute de France and the Department of Culture and Tourism (DCT) Abu Dhabi to showcase her work at the inauguration of the Louvre Abu Dhabi. Currently she is one of the artists in residence for SETI-Institute in San Francisco, and her work was featured in EXPO2020 Dubai at the Sustainable Pavilion. She also participated in Desert X in AlUla, KSA in 2022.

FOREVER IS NOW .02 70

ﺬﻨﻣ ﺖﻓﺮﻋ ﻲــﺑد ﻲﻓ ﺔﻤﻴﻘﻣ ﺔــﻴﻤﻴﻫﺎﻔﻣ ﺔﻴﺗارﺎﻣإ ﺔــﻧﺎﻨﻓ ﻲﻤــﺷﺎﻬﻟا ﺐــﻨﻳز نﻮﻨﻔﻟا ﻲﻓ سﻮــﻳرﻮﻟﺎﻜﺒﻟا ﺔﺟرد ﻰــﻠﻋ ﺎﻬﻟﻮﺼﺣو ﺪﻳاز ﺔــﻌﻣﺎﺟ ﻦــﻣ ﺎــﻬﺟﺮﺨﺗ ةﺮﺻﺎﻌﻤﻟا ﺎــﻬﺗاﺰﻴﻬﺠﺘﺑ ،ةدﺪــﻌﺘﻤﻟا ﻂﺋﺎــﺳﻮﻟا ﻢﻴﻤﺼﺗ ﺺﺼﺨﺗ ﻲــﻓ مﻮــﻠﻌﻟاو طﺎﻘﺘﻟﺎﺑ ﺔــﻧﻮﺘﻔﻣ ﻲﻤــﺷﺎﻬﻟا ﺐﻨﻳز . دﺪﺤﻣ ﻊﻗﻮﻤﺑ ﺔــﺻﺎﺨﻟا ةﺮــﻴﺒﻜﻟا مﺎــﺠﺣ ا تاذ ﺔﻳدﺎﻤﺘﻋﻻاو ﻦــﻳﺎﺒﺘﻟا ﺪﺻرو ةﺪﺤﺘﻤﻟا ﺔــﻴﺑﺮﻌﻟا تارﺎــﻣ ا ﺔﻟود ﻰﻠﻋ أﺮﻄﻳ يﺬــﻟا لﻮــﺤﺘﻟا ﺔﻳﻮﻴﺤﻟا لﺎﻜــﺷ او ناﺮﻤﻌﻠﻟ ﺔﻴــﺳﺪﻨﻬﻟاو ةدﺮﺠﻤﻟا لﺎﻜــﺷ ا ﻦــﻴﺑ ﺔــﻟدﺎﺒﺘﻤﻟا ﺪﻫﺎــﺸﻤﻟا ﺖــﺷﻮﺸﺗ ،ﺔﻧﺎﻨﻔﻟا ﺔﻟﻮﻔﻃ ﺬﻨﻣ ﺎــﻫﺪﻠﺒﻟ ﺔــﻴﻌﻴﺒﻄﻟا ﺮــﻇﺎﻨﻤﻟﺎﺑ ﺔــﻄﺒﺗﺮﻤﻟا ﻮﻫ ﺎﻣ رﻮﻬﻈﻟ لﺎــﺠﻤﻟا ﺔﺣﺎﺗ ﺮــﻴﺒﻛ ﺪﺣ ﻰــﻟإ ﺔــﻴﻌﻴﺒﻄﻟاو ﺔــﻓﻮﻟﺄﻤﻟا ﺔــﻳﺪﻴﻠﻘﺘﻟا

داﻮﻤﻟا ﻦﻣ ﺔــﻋﻮﻨﺘﻣ ﺔــﻋﻮﻤﺠﻣ ﻰــﻠﻋ برﺎــﺠﺗ نﻼﻌﺠﻳ ﺲﻤﻠﻤﻟاو نﻮــﻠﻟا نأ ﻦﻴﺣ ﻲــﻓو . ﻲﻋﺎﻨﻄﺻﻻاو ﻲــﻌﻴﺒﻄﻟا ﻦــﻴﺑ ﺔــﺳﻮﻤﻠﻤﻟا شﻮــﺸﺘﺗ ﺔﻔﻟ ا هﺬﻫ نﺈﻓ ،ﺔﻳﺪﻴﻠﻘﺘﻟا ﺔــﻴﻌﻴﺒﻄﻟا ﺮــﻇﺎﻨﻤﻟا تﺎــﻳﺮﻛﺬﺑ ﻼــﻓﺎﺣ ﺎــﻬﻠﻤﻋ يﺮــﺸﺒﻟا ﻞﺧﺪﺘﻟﺎﺑ ﺪﻫﺎــﺸﻤﻟا ﺮﻛﺬﺗ ﻲﺘﻟا ﺔﻴﻋﺎﻨﺼﻟا داﻮــﻤﻠﻟ ﻞــﻫﺬﻤﻟا ﻦــﻳﺎﺒﺘﻟا ﺐﺒــﺴﺑ ﺔﺛاﺪﺤﻟا ﻦﻴﺑ ﺎــﻘﻴﻗد ﺎﻧزاﻮﺗ ﻖــﻘﺤﺗ ﺚﻴﺣ ،مﻮﻴﻟا ﺎــﻬﻨﻃو ﺮﻫﻮﺟ ﺐــﻨﻳز ﻞــﻤﻋ ﺪــﺴﺠﻳ ﺪﻳﺪﻌﻟا ﻲﻓ ﺖﻛرﺎــﺷ ﻊﻗﻮﺘﻣ ﺮﻴﻏ ﻞﻜــﺸﺑ ﻢﻏﺎﻨﺘﻣ ﺶــﻳﺎﻌﺗ ﻲــﻓ ﺪــﻴﻟﺎﻘﺘﻟاو ﻲﺑد عﻮﺒــﺳأو ،ﻲﻨﻔﻟا ﺔﻜــﺳ ضﺮﻌﻣ ﻞﺜﻣ تﺎﻧﺎﺟﺮﻬﻤﻟاو ﺔــﻴﻨﻔﻟا ضرﺎــﻌﻤﻟا ﻦــﻣ ﻲــﺴﻧﺮﻔﻟا ﺰﻛﺮﻤﻟا ﻞﺒﻗ ﻦﻣ اﺮــﺧﺆﻣ ﺎﻬﻔﻴﻠﻜﺗ ﻢــﺗ .١١ ﺔﻗرﺎــﺸﻟا ﻲــﻟﺎﻨﻴﺑو ،ﻢــﻴﻤﺼﺘﻠﻟ

ART D’ÉGYPTE 71

ةﺪﻳﺪﺟ ﺔﻳﻮﻫ ﻦــﻋ ،ﻲــﺒﻳﺮﺠﺘﻟا ارﻮﺼﺗ ﻖﻠﺨﺗو ﺔــﻠﻳﺪﺑ ﺮﻈﻧ ﺔــﻬﺟو ﻚﻟﺬﺑ مﺪــﻘﺘﻟ ﻢــﻬﻄﻴﺤﻤﻟ ﻦﻳﺪﻫﺎــﺸﻤﻟا ﻢــﻬﻓ ﻊﻗاﻮﻟا اﺬﻬﻟ اﺪــﻳﺪﺟ يﺮﺠﺗو ،تارﺎﻣ ا ﺔﻟوﺪﻟ ﺔــﻴﻌﻴﺒﻄﻟا ﺲــﻳرﺎﻀﺘﻟا ﻦﻣ ﺎــﻬﻟﺎﻤﻋأ ﻲﻤــﺷﺎﻬﻟا ﻢﻬﻠﺘــﺴﺗ ﺮﻴﻏ دوﺪﺤﻟا ﺮــﺒﻋ ﺪﻫﺎــﺸﻤﻟا ﻊﻀﺘﻟ

ﺔــﻓﺎﻘﺜﻟا ةﺮــﺋادو نﺎــﺳ ﻲﻓ " ﻲﺘﻴــﺳ " ﺪﻬﻌﻣ ﻲﻓ ﻦﻴﻤﻴﻘﻤﻟا ﻦﻴﻧﺎﻨﻔﻟا ﻦــﻣ ةﺪﺣاو ﺎــﻴﻟﺎﺣ ﻲــﻫو ،ﻲــﺒﻇ حﺎﻨﺠﻟا ﻲﻓ ﻲــﺑد ٢٠٢٠ ﻮﺒــﺴﻛإ ضﺮﻌﻣ ﻲﻓ ﺎﻬﻟﺎﻤﻋأ ﺖــﺿﺮﻋ ﺪــﻗو ،ﻮﻜــﺴﻴﺴﻧاﺮﻓ ﺔﻴﺑﺮﻌﻟا ﺔــﻜﻠﻤﻤﻟﺎﺑ ﻼــﻌﻟا ﻲﻓ " ﺲﻛأ تﺮﻳﺰﻳد " ضﺮﻌﻣ ﻲــﻓ ﺖﻛرﺎــﺷ ﺎــﻤﻛ ماﺪﺘــﺴﻤﻟا ٢٠٢٢ مﺎﻋ ﺔﻳدﻮﻌــﺴﻟا Represented by ﺎﻬﻠﺜﻤﻳ ﺔــﻧﺎﻨﻔﻟا

( ﻦــﺸﻴﻠﺘﺴﻧﻻا ) غاﺮﻔﻟا ﻲﻓ ﺰﻴﻬﺠﺘﻟا لﻼــﺧ ﻦﻣ ،ﺚﺤﺒﺗ . ﺮــﺸﺒﻟا ﻞــﺒﻗ ﻦــﻣ عﻮــﻨﺼﻣ ﻚﻴﻜﻔﺘﺑ مﻮــﻘﺗو ﺔﺜﻳﺪﺤﻟا فوﺮــﻈﻟا ﻊﻣ ﺐــﺳﺎﻨﺘﺗ

ﻮﺑأ ﺮﻓﻮﻠﻟا ﻒــﺤﺘﻣ حﺎﺘﺘﻓا ﻲــﻓ ﺎﺿﺮﻋ مﺪﻘﺘﻟ ﻲــﺒﻇﻮﺑﺄﺑ ﺔﺣﺎﻴــﺴﻟاو

Photo: Simon Berger on Unsplash

Photo: Simon Berger on Unsplash

عور� ملا ��اوم

لا PARALLEL PROJECTS

JR I NSIDE O UT G I Z A

Interactive Photobooth 11 m x 11 m x 7 m 2022

Inside Out Giza is the frst Inside Out Photobooth installation in Egypt – every participant will visit the pyramid-shaped interactive photobooth and receive a large-scale black and white portrait, that will be pasted onto billboards in front of the Great Pyramids of Giza, making an ephemeral personal statement in front of timeless monuments.

FOREVER IS NOW .02 74 PARALLEL PROJECTS

ART D’ÉGYPTE 75 ﻲﻠﻋﺎﻔﺗ ﺮﻳﻮﺼﺗ ﻚــﺸﻛ م٧ × م١١ × م١١ ٢٠٢٢ ( ﻦــﺸﻴﻠﺘﺴﻧا ) غاﺮﻔﻟا ﻲﻓ ﺰﻴﻬﺠﺗ لوأ ﻮــﻫ ، " جرﺎﺨﻠﻟ ﻞــﺧاﺪﻟا ﻦــﻣ ةﺰــﻴﺠﻟا " مﺎﻘﻣ ﻲﻠﻋﺎﻔﺗ ﺮــﻳﻮﺼﺗ ﻚــﺸﻛ ءﺎــﺸﻧإ ﻢﺘﻳ فﻮــﺳ . ﺮﺼﻣ ﻲﻓ ﻪﻋﻮﻧ ﻦــﻣ ﻰﻠﻋ ﻞﺼﺤﻳو ،ضﺮﻌﻤﻟا ﻲﻓ كرﺎــﺸﻣ ﻞﻛ هروﺰﻴــﺳ ،مﺮﻫ ﻞﻜــﺷ ﻰﻠﻋ ﻰﻠﻋ رﻮﺼﻟا ﻚــﻠﺗ ﻖﺼﻟ ﻢﺘﻳ ﻢــﺛ دﻮــﺳ او ﺾﻴﺑ ﺎﺑ ةﺮﻴﺒﻛ ﺔﻴﺼﺨــﺷ ةرﻮــﺻ كرﺎــﺸﻣ ﻞﻛ ﻲﻟﺪﻳ ﻚﻟﺬﺑو ،ةﺰﻴﺠﻟا تﺎــﻣاﺮﻫأ مﺎﻣأ ﺔــﻴﻧﻼﻋ ا تﺎــﺣﻮﻠﻟا ةﺪﻟﺎﺨﻟا رﺎﺛ ا ﻚــﻠﺗ مﺎﻣأ ﺖﻗﺆﻣ رﻮــﻀﺤﻟ ﺔﻴﺼﺨــﺷ ةدﺎﻬــﺸﺑ يزاﻮﻤﻟا عوﺮﺸﻤﻟا رآ ﻪﻴﺟ جرﺎﺨﻟا ﻰﻟإ ﻞﺧاﺪﻟا ﻦﻣ - ةﺰــﻴﺠﻟا

JR I NSIDE O UT G I Z A

Photo: Hesham Al Saif

Photo: Hesham Al Saif

رآ ﻪﻴﺟ جرﺎﺨﻟا ﻰﻟإ ﻞﺧاﺪﻟا ﻦﻣ - ةﺰــﻴﺠﻟا

JR exhibits freely in the streets of the world, catching the attention of people who are not typical museum visitors, from the suburbs of Paris to the slums of Brazil to the streets of New York, pasting huge portraits of anonymous people, from Kibera to Istanbul, from Los Angeles to Shanghai. In 2011, he received the TED Prize, after which he launched Inside Out, an international participatory art project that allows people worldwide to get their picture taken and paste it to support an idea and share their experience. As of June 2021, over 420,000 people from more than 138 countries have participated, through mail or gigantic photobooths. His recent projects include a large-scale pasting in a maximum security prison in California; a TIME Magazine cover about COVID; a video mural including 1,200 people presented at SFMOMA; a collaboration with New York City Ballet; an Academy Award-nominated feature documentary co-directed with Nouvelle Vague legend Agnès Varda; the pasting of a container ship; the pyramid of the Louvre; giant scaffolding installations at the 2016 Rio Olympics; an exhibition on the abandoned hospital of Ellis Island; a social restaurant for homeless and refugees in Paris; and a gigantic installation at the US-Mexico border fence. As he remains anonymous and doesn’t explain his huge fullframe portraits of people making faces, JR leaves the space empty for an encounter between the subject/protagonist and the passer-by/interpreter. That is what JR's work is about, raising questions...

FOREVER IS NOW .02 78

ﻞﺼﺣ

يﺎﻬﻐﻨــﺷ ﻰﻟإ سﻮﻠﺠﻧأ

ﻰﻔــﺸﺘﺴﻣ ﻪﻴﺟ ن اﺮﻈﻧ .ﻚﻴــﺴﻜﻤﻟاو ةﺪﺤﺘﻤﻟا تﺎﻳﻻﻮﻟا ﻦﻴﺑ يدوﺪﺤﻟا جﺎﻴــﺴﻟا ﺪﻨﻋ ﺔﻗﻼﻤﻋ ةﺄــﺸﻨﻣو ،ﺲﻳرﺎﺑ ،ﻞﻣﺎﻜﻟﺎﺑ ةﺮﻃﺆﻤﻟا ﺔﻤﺨﻀﻟا ﺔﻴﺼﺨــﺸﻟا رﻮﺼﻟا عوﺮــﺸﻣ حﺮــﺸﻳ نأ ﺪﻳﺮﻳ ﻻو ،ﻻﻮﻬﺠﻣ ﻞﻈﻳ نأ دﻮﻳ رآ وﺮــﺴﻔﻣ ،نﻮﻘﻠﺘﻤﻟا يأ ةرﺎﻤﻟا ﻦﻴﺑو ،ﻞﻄﺒﻟا يأ عﻮﺿﻮﻤﻟا

Achievements

2021 JR: Chronicles, solo exhibition, Saatchi Gallery, London, UK

2021 Eye to the World, solo exhibition, PACE, London, UK

2021 Greetings from Giza, Forever Is Now, Art D’Égypte, Cairo, Egypt

2020 Tehachapi, solo exhibition, Perrotin, Paris, France

2020 Omelia Contadina, solo exhibition, Galleria Continua, San Gimignano, Italy

2020 Homily to Country, installation at the National Gallery of Victoria Art Triennial,

Melbourne, Australia

2019 The Chronicles of San Francisco, SFMOMA, San Francisco, CA, USA

2019 JR: Chronicles, solo exhibition, Brooklyn Museum, New York, NY, USA

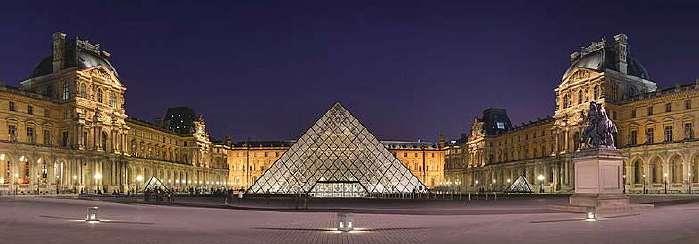

2019 JR au Louvre: le secret de la grande pyramide, installation at the Louvre for the 30-year-anniversary of the Pyramid, Paris, France

2018 Momentum, solo exhibition, Maison Européenne de la Photographie, Paris, France

ART D’ÉGYPTE 79 راوز ﺲﻴﻟو ﻦﻳﺮﺑﺎﻌﻟا صﺎﺨــﺷ ا هﺎﺒﺘﻧا ﺎﺑذﺎﺟ ﻢﻟﺎﻌﻟا عراﻮــﺷ ﻲﻓ ﺔﻳﺮﺤﺑ ﻪﻟﺎﻤﻋأ ضﺮﻌﻳ رآ ﻪﻴﺟ ،ﻞﻳزاﺮﺒﻟا ﻲﻓ ةﺮﻴﻘﻔﻟا ءﺎﻴﺣ ا ﻰــﻟإ ﺲﻳرﺎﺑ ﻲﺣاﻮﺿ ﻦﻣ

بﻮﺠﻳ ﻮﻬﻓ

ﻮﻴﻧﻮﻳ ﻦﻣ

ﻚﻟذو

؛ةﺮﻴﺧ ا ﻪﻌﻳرﺎــﺸﻣ ﻞﻤــﺸﺗ ﺔﻗﻼﻤﻌﻟا ﺮﻳﻮﺼﺘﻟا كﺎــﺸﻛأ وأ ﺪﻳﺮﺒﻟا لﻼﺧ ﻦﻣ ﺎﻣإ ،ﺔﻟود ١٣٨ ﻦﻣ ﺮﺜﻛأ "ﻢﻳﺎﺗ" ﺔﻠﺠﻣ فﻼﻏو ،ﺎﻴﻧرﻮﻔﻴﻟﺎﻛ ﻲﻓ ﺔــﺳاﺮﺤﻟا ﺪﻳﺪﺷ ﻦﺠــﺳ ﻲﻓ ﻊــﺳاو قﺎﻄﻧ ﻰﻠﻋ ارﻮﺻ ﻖﺼﻟ ﻒﺤﺘﻣ ﻲﻓ ﺎﻬﻤﻳﺪﻘﺗ ﻢﺗ ﺺﺨــﺷ ١٢٠٠ ﻢﻀﺗ ﻮﻳﺪﻴﻔﻟﺎﺑ ﺔﻳراﺪﺟ ﺔﺣﻮﻟو ،ﺎﻧورﻮﻛ ﺔــﺤﺋﺎﺟ لﻮــﺣ ﻲﻘﺋﺎﺛو ﻢﻠﻴﻓو ،كرﻮﻳﻮﻴﻧ ﺔﻨﻳﺪﻣ ﻪﻴﻟﺎﺑ ﺔﻗﺮﻓ ﻊﻣ نوﺎﻌﺗو ،ﺚﻳﺪﺤﻟا ﻦﻔﻠﻟ ﻮﻜــﺴﻴﺴﻧاﺮﻓ نﺎــﺳ ﻰﻟإ ﺔﻴﻤﺘﻨﻤﻟا ادرﺎﻓ ﺲﻨﺟأ ةرﻮﻄــﺳ ا ﻪﺟاﺮﺧﺈﺑ كرﺎﺷ يﺬﻟاو رﺎﻜــﺳو ا ةﺰﺋﺎﺠﻟ ﻪﺤﻴــﺷﺮﺗ ﻢﺗ ،ﺮﻓﻮﻠﻟا مﺮﻫو ،تﺎﻳوﺎﺣ ﺔﻨﻴﻔــﺳ ةرﻮﺻ ﻖﺼﻟو ،ﺎــﺴﻧﺮﻓ ﻲﻓ ﺎﻤﻨﻴــﺴﻠﻟ ةﺪﻳﺪﺠﻟا ﺔﺟﻮﻤﻟا ﺔﻛﺮﺣ ﻦﻋ ضﺮﻌﻣو ،٢٠١٦ ﻮﻳر دﺎﻴﺒﻤﻟوأ ﻲﻓ

ﻦﻴﺌﺟﻼﻟ ﻲﻋﺎﻤﺘﺟا ﻢﻌﻄﻣو ،كرﻮﻳﻮﻴﻨﺑ ﺲﻴﻟإ ةﺮﻳﺰﺟ ﻲﻓ رﻮﺠﻬﻣ

ﻦﻴﺑ ﺎﻣ ءﺎﻘﻠﻟ

ﻢﻟﺎﻌﻟا

،ﻦــﻴﻳﺪﻴﻠﻘﺘﻟا ﻒــﺤﺘﻤﻟا ﻦﻣو ،لﻮﺒﻨﻄــﺳإ ﻰﻟإ اﺮﻴﺒﻴﻛ ﻦﻣ ،ﻦﻴﻟﻮﻬﺠﻣ صﺎﺨــﺷ ﺔﻤﺨﺿ ارﻮﺻ ﻖﺼﻠﻳو كرﻮﻳﻮﻴﻧ عراﻮــﺷ ﻞﺧاﺪﻟا ﻦﻣ" ةردﺎﺒﻣ ﺎﻫﺪﻌﺑ ﻖﻠﻃأو ،TED ةﺰﺋﺎﺟ ﻰﻠﻋ ،٢٠١١ ﻲــﻓ

.

سﻮــﻟ صﺎﺨﺷ ﻟ ﺔﺻﺮﻔﻟا ﻲﻄﻌﻳ ﻲﻟوﺪﻟا ىﻮﺘــﺴﻤﻟا ﻰﻠﻋ ﻲﻛرﺎــﺸﺗ ﻲﻨﻓ عوﺮــﺸﻣ ﻮﻫو ، "جرﺎﺨﻟا ﻰﻟإ ﺔﻛرﺎــﺸﻣو ﺎﻣ ةﺮﻜﻓ ﻢﻋﺪﻟ ﺎﻬﻘﺼﻟو ﺔﻴﺼﺨــﺸﻟا ﻢﻫرﻮﺻ طﺎﻘﺘﻟﺎﺑ ﻢﻟﺎﻌﻟا ءﺎﺤﻧأ ﻊﻴﻤﺟ ﻦﻣ ﻦﻣ ﺺﺨــﺷ ﻒﻟأ٤٢٠ ﻦﻋ ﺪﻳﺰﻳ ﺎﻣ عوﺮــﺸﻤﻟا ﻲﻓ كرﺎــﺷ ٢٠٢١

ارﺎﺒﺘﻋا

،ﻢﻬﺘﺑﺮﺠﺗ

ﺔﻗﻼﻤﻋ تﻻﺎﻘــﺴﻟ (ﻦــﺸﻴﻠﺘﺴﻧا) غاﺮﻔﻟا ﻲﻓ ﻢﺨﺿ ﻞﻴﻜــﺸﺗو ﻲﻓ ﻦﻳدﺮــﺸﻤﻟاو

ﺔﻳوﺎﺧ ﺔﺣﺎــﺴﻣ كﺮﺘﺑ ﻪﻧﺄﻓ ﺔﻠﺌــﺳ ا حﺮﻃ ﻰﻠﻋ رآ ﻪﻴﺟ لﺎﻤﻋأ مﻮﻘﺗ ﺚﻴﺣ ،ﻲﻨﻔﻟا ﻞــﻤﻌﻟا ."ﺮﻟزور ارﺎﻧ ﺎﻳﺮﻴﻟﺎﺟ"و ، "اﻮﻴﻨﻴﺘﻧﻮﻛ ﺎــﻳﺮﻴﻟﺎﺟ" ، "ﻲــﺳﺎﺑ" ، "نﺎﺗوﺮﻴﺑ" ﻪﻠﺜﻤﻳ نﺎﻨﻔﻟا

Represented by Perrotin, Pace, Galleria Continua, and Galeria Nara Roesler.

L ITER OF L IGHT T HE P OWER I S Y OURS

Hand-built solar lights assembled by women cooperatives from the UNESCO heritage city of Safi, Morocco; youth; and volunteers. 25 m x 25 m 2022

‘The Power Is Yours’ is one of the most iconic rallying calls for the environment which began 30 years ago with Captain Planet, the frst multi-racial environmental children’s series. Although it only aired for six seasons, this Saturday morning program deviated from the previous focus on a Western-centric hero and is still remembered as the frst exposure to a generation of youth around the world about environmental issues.

The upcoming conference on climate change shifts the perspective of climate issues, allowing voices from Africa, the Middle East, and Asia to be able to be a greater part of the narrative.

This participative solar art installation comprises 1,200 lights built with sustainable materials, pottery, and upcycled plastic bottles, assembled in collaboration with youth volunteers who will each give 30 minutes to make a solar light that lasts for fve years. The lamps for the installation are being produced by a cooperative of 200 ceramic potters from the city of Saf, Morocco, which recently received recognition from UNESCO as a world city for the ceramics industry.

In this collaborative project with SHEMS for Lighting, we are hoping to produce multiple renditions of this human-powered billboard during Forever Is Now .02 , as well as in cultural heritage sites around the region, creating a global link between UNESCO sites to amplify youth voices and express a collective hope for the future, a future where each person knows that they have the power to make a difference.

FOREVER IS NOW .02 80 PARALLEL PROJECTS

ﻖــﻳﺮﻃ

ﻢﻟﺎﻌﻟا بﺎﺒــﺷ

ﻞﻴﺟ ﻊــﻣ ﺔــﻴﺌﻴﺒﻟا ﺎــﻳﺎﻀﻘﻟا ﺶــﻗﺎﻨﻳ رﻮﻈﻨﻣ ﻦﻣ خﺎــﻨﻤﻟا ﺮﻴﻐﺗ لﻮــﺣ مدﺎﻘﻟا ﺮﻤﺗﺆﻤﻟا ل ّ ﺪــﺒﻳ ﻚﻟﺬﻛ . بﺮﻐﻟا ﻦــﻣ ﺲــﻴﻟ نأ ﺎﻴــﺳآو ﻂــﺳو ا قﺮــﺸﻟاو ﺎﻴﻘﻳﺮﻓإ ﻦﻣ تاﻮﺻ ﻟ ﺢﻤــﺴﻳ ﺎﻤﻣ ،خﺎﻨﻤﻟا ﺎﻳﺎﻀﻗ ﺔﻴﻀﻘﻟا ﻦــﻣ ﺮﺒﻛأ اءﺰﺟ ﻞﻜــﺸﺗ ﻰﻠﻋ ﻲﻛرﺎــﺸﺘﻟا ﻲﻨﻔﻟا ( ﻦــﺸﻴﻠﺘﺴﻧﻻا ) غاﺮﻔﻟا ﻲــﻓ ﻞﻴﻜــﺸﺘﻟا اﺬﻫ يﻮــﺘﺤﻳ دﺎﻌﻣ ﺔﻴﻜﻴﺘــﺳﻼﺑ تﺎﺟﺎﺟزو رﺎــﺨﻓو ﺔﻣاﺪﺘــﺴﻣ داﻮﻣ ﻦﻣ نﻮــﻜﻣ حﺎــﺒﺼﻣ ١٢٠٠ ﻢﻬﻨﻣ ﻞﻛ ﺢــﻨﻤﻳ بﺎﺒــﺷ ﻦﻴﻋﻮﻄﺘﻣ ﻊﻣ نوﺎــﻌﺘﻟﺎﺑ ﺎــﻬﻌﻴﻤﺠﺗ ﻢــﺗ ،ﺎــﻫﺮﻳوﺪﺗ جﺎﺘﻧإ ﻢﺘﻳ . تاﻮﻨــﺳ ﺲﻤﺨﻟ ﻪﺗرﺎﻧإ ﺮﻤﺘــﺴﺗ ﻲــﺴﻤﺷ حﺎﺒﺼﻣ ﻊــﻨﺼﻟ ﺔــﻘﻴﻗد ٣٠ ﻦﻣ ﺔﻧﻮﻜﻣ ﺔــﻴﻧوﺎﻌﺗ

ART D’ÉGYPTE 81 ﻞــﺒﻗ ﻦــﻣ ﺎــﻬﻌﻴﻤﺠﺗ ﻢــﺗ ﺎــﻳوﺪﻳ ﺔــﻋﻮﻨﺼﻣ ﺔﻴــﺴﻤﺷ ﺢــﻴﺑﺎﺼﻣ ﻮﻜــﺴﻧﻮﻴﻠﻟ ﺔــﻌﺑﺎﺘﻟا ﺔــﻴﺛاﺮﺘﻟا ﻲﻔــﺳآ ﺔــﻨﻳﺪﻣ ﻦــﻣ ﺔﻴﺋﺎــﺴﻧ تﺎــﻴﻧوﺎﻌﺗ . ﻦــﻴﻋﻮﻄﺘﻣو بﺎﺒــﺷ ﻊــﻣ نوﺎــﻌﺘﻟﺎﺑ بﺮــﻐﻤﻟﺎﺑ م٢٥ × م٢٥ ٢٠٢٢ ﺎﻣﺎﻋ ٣٠ ﻞﺒﻗ تأﺪــﺑ ﻲﺘﻟاو ﻲﺌﻴﺒﻟا ﺪــﺸﺤﻟا تاﻮﻋد ﺮﻬــﺷأ ﻦﻣ " ﻢــﻜﻟ ةﻮــﻘﻟا " ﺮــﺒﺘﻌﺗ ﻰﻠﻋ ﺔﺌﻴﺒﻟا ﻦــﻋ لﺎﻔﻃ ﻟ قاﺮــﻋﻻا دﺪﻌﺘﻣ ﻞــﺴﻠﺴﻣ لوأ ،ﺖﻴﻧﻼﺑ ﻦــﺘﺑﺎﻛ ﻊــﻣ ﺞﻣﺎﻧﺮﺑ لوﺄﻛ ﺮــﻛﺬﻳ لاﺰﻳ ﻻ ،ﻢــﺳاﻮﻣ ﺔﺘــﺳ ﻦﻣ ﺮﺜﻛ ﺚﺒﻳ ﻢﻟ ﻪﻧأ ﻦــﻣ

ﺔﻄــﺳاﻮﺑ ( ﻦــﺸﻴﻠﺘﺴﻧﻻا ) ﻲﻨﻔﻟا ﻞــﻤﻌﻟﺎﺑ ﺔــﺻﺎﺨﻟا ﺢــﻴﺑﺎﺼﻤﻟا ﻦﻣ ﺎﻓاﺮﺘﻋا اﺮــﺧﺆﻣ ﺔﻨﻳﺪﻤﻟا ﺖــﻘﻠﺗ ﺪﻗو ،بﺮﻐﻤﻟﺎﺑ ﻲﻔــﺳآ ﺔﻨﻳﺪﻣ ﻦــﻣ فا ّ ﺰــﺧ ٢٠٠ فﺰﺨﻟا ﺔﻋﺎﻨﺼﻟ ﺔــﻴﻤﻟﺎﻋ ﺔــﻨﻳﺪﻣ ﺎﻬﻧإ ﻰــﻠﻋ ﻮﻜــﺴﻧﻮﻴﻟا ﺦــﺴﻧ جﺎﺘﻧإ ﻲﻓ ﻞﻣﺄﻧ ،ةءﺎﺿ ﻟ ﺲﻤــﺷ ﺔﻛﺮــﺷ ﻊﻣ ﻲﻧوﺎﻌﺘﻟا عوﺮــﺸﻤﻟا اﺬﻫ ﻲﻓ تﺎﻴﻟﺎﻌﻓ لﻼــﺧ ﺔﻳﺮــﺸﺒﻟا ﺔﻗﺎﻄﻟﺎﺑ ﻞﻤﻌﺗ ﻲﺘﻟا ﺔــﻴﻧﻼﻋ ا ﺔﺣﻮﻠﻟا ﻦــﻣ ةدﺪــﻌﺘﻣ ءﺎﺤﻧأ ﻊﻴﻤﺟ ﻲــﻓ ﻲﻓﺎﻘﺜﻟا ثاﺮــﺘﻟا ﻊﻗاﻮﻣ ﻲﻟإ ﺔﻓﺎﺿإ ، "٢ ن ا ﻮــﻫ ﺪــﺑ ا " ﺪﻴﻛﺄﺘﻟ ﺔﻠﻴــﺳﻮﻛ ﻮﻜــﺴﻧﻮﻴﻟا ﻊﻗاﻮﻣ ﻦﻴﺑ ﺎــﻴﻟود ﺎﻄﺑار ﻖﻠﺨﻴــﺳ ﻚــﻟذو ،ﺔــﻘﻄﻨﻤﻟا ﻪﻴﻓ فﺮﻌﻳ ﻞﺒﻘﺘــﺴﻣ ،ﻞﺒﻘﺘــﺴﻤﻠﻟ ﻲﻋﺎﻤﺠﻟا ﻞــﻣ ا ﻦﻋ ﺮــﻴﺒﻌﺘﻟاو بﺎﺒــﺸﻟا تاﻮــﺻأ قﺮﻓ ثاﺪﺣإ ﻰﻠﻋ ةرﺪــﻘﻟا ﻪﻳﺪﻟ نأ ﺺﺨــﺷ ﻞﻛ يزاﻮﻤﻟا عوﺮﺸﻤﻟا ﺖــﻳﻻ فوأ ﺮﺘﻴــﻟ ﻚﺗﻮــﻗ ةﻮــﻘﻟا

ﻢــﻏﺮﻟا ﻞﻄﺑ ﻢﻳﺪﻘﺗ

ﻦﻋ

ﻦﻣ

Liter of Light is an ambassador of the UNESCO International Day of Light. A grassroots solar lighting movement, the organisation teaches people about the challenges we face by sharing innovations that inspire action and build climate resilience.

Liter of Light’s hand-built solar lighting technologies create local jobs, teach green skills, and empower energy-poor communities. Rather than depending on imported, patented, and expensive technologies, its work embodies the principle that anyone can become a solar engineer. Since 2013, the organisation has empowered over one million lives a year across 32 countries.

‘Light It Forward’ – the hybrid digital/offine campaign that Liter of Light launched in 2020 – has given thousands of people a new way to create a more sustainable future. By inviting people to assemble hand-built solar lights, ‘Light it Forward’ reminds each person that they have the power to make a positive impact in the world. The campaign has engaged over 4,000 people and empowered over 75,000 families.

To show the power of collective action, Liter of Light takes its hand-built solar lights and creates some of the largest solar artworks in the world. Through these large-scale lighting installations, the organisation inspires people that innovation can come from anyone, anywhere.

FOREVER IS NOW .02

82

صﺎﺨﻟا ءﻮﻀﻠﻟ ﻲﻤﻟﺎﻌﻟا مﻮﻴﻟا ةﺮﻴﻔــﺳ ﻲﻫ "رﻮﻧ ﻦﻣ ﺮﺘﻟ" وأ ﺖــﻳﻻ فوأ ﺮــﺘﻴﻟ ﻒﻴﻘﺜﺘﺑ ﺔﻤﻈﻨﻤﻟا مﻮﻘﺗ ﺚﻴﺣ ،ﺔﻴــﺴﻤﺸﻟا ةءﺎﺿ ﻟ ﺔﻴﺒﻌــﺷ ﺔﻛﺮﺣ ﻲﻫو ،ﻮﻜــﺴﻧﻮﻴﻟﺎﺑ ﻢﻬﻠﺗ ﺪﻗ ﻲﺘﻟا تارﺎﻜﺘﺑﻻا ﺔﻛرﺎــﺸﻣ ﻖﻳﺮﻃ ﻦﻋ ﺎﻬﻬﺟاﻮﻧ ﻲﺘﻟا تﺎﻳﺪﺤﺘﻟا ﻦــﻋ سﺎــﻨﻟا .خﺎﻨﻤﻟا ﺮﻴﻐﺗ ﻊﻣ ﻞﻣﺎﻌﺘﻠﻟ ﺔــﻧوﺮﻣ ﻖﻠﺨﻟو ﻞﻤﻌﻠﻟ سﺎــﻨﻟا

Achievements

2020 Shedding Light on the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, Makati City Hall and Bonifacio Global City, Metro Manila, Philippines

2020 Light It Forward: Messages of Hope, San Juan, Mandaluyong and Pasay City, Metro Manila, Philippines

2021 Another World Is Possible, Castello Sforzesco, Milan, Italy

2021 Action, Not Words, University of Saint Andrews, St Andrews, Scotland

2021 The Time Is Now, Mission Possible, Opportunity Pavilion, EXPO2020, Dubai, United Arab Emirates

2022 The Future Is In Our Hands, Dar Sultan, Saf, Morocco

ART D’ÉGYPTE 83

ﻦﻣ ﺮﺘﻟ

ﺔﻛﺮﺣ

ةدرﻮﺘــﺴﻣ تﺎﻴﻨﻘﺗ ﻰﻠﻋ دﺎﻤﺘﻋﻻا ﻦﻣ ﻻﺪﺒﻓ ﺔﻗﺎﻄﻟا ﻰــﻟإ ﺮــﻘﺘﻔﺗ ﺎــﺳﺪﻨﻬﻣ ﺢﺒﺼﻳ نأ ﻰﻠﻋ ردﺎﻗ ﺺﺨــﺷ يأ نأ أﺪﺒﻣ ﺮﻘﺗ ﻲﻬﻓ ،ﺔﻔﻠﻜﺘﻟا ﺔﻌﻔﺗﺮﻣو عاﺮﺘﺧا نﻮﻴﻠﻣ ﻦﻣ ﺮﺜﻛأ ﻦﻴﻜﻤﺗ ﻦﻣ ﺔﻤﻈﻨﻤﻟا ﺖﻋﺎﻄﺘــﺳا ،٢٠١٣ مﺎﻋ ﺬﻨﻣ .ﺔﻴــﺴﻤﺸﻟا ﺔﻗﺎﻄﻠﻟ .ﺔﻟود ٣٢ ﻲﻓ ﺎﻳﻮﻨﺳ ﺺﺨــﺷ ﺔﻠﺼﺘﻣ ﺮﻴﻏ (ﺔﻨﻴﺠﻫ) ﺔــﻄﻠﺘﺨﻣ لﻮﺻأ تاذ ﺔﻴﻤﻗر ﺔﻠﻤﺣ ﻦﻋ ةرﺎﺒﻋ "ﺎــﻣﺪﻘﻣ ﻪــﺌﺿأ

ةﺪﻳﺪﺟ ﺔﻘﻳﺮﻃ صﺎﺨــﺷ ا فﻻآ ﺖﺤﻨﻣ ﺪﻗو ،٢٠٢٠ مﺎﻋ "رﻮﻧ ﻦﻣ ﺮﺘﻟ" ﺎــﻬﺘﻘﻠﻃأ ﺖــﻧﺮﺘﻧ ﺎﺑ

ثاﺪــﺣإ

ةﺮﺳأ ٧٥٠٠٠

ﺔﻴﻨﻔﻟا لﺎﻤﻋ ا ﺮﺒﻛأ ﻦﻣ ﺎﻀﻌﺑ "رﻮــﻧ ﻦﻣ ﺮﺘﻟ" ﻖﻠﺨﺗ ،ﻲﻋﺎﻤﺠﻟا ﻞﻤﻌﻟا ةﻮــﻗ رﺎــﻬﻇ ةءﺎﺿ ا تﺎﺒﻴﻛﺮﺗ لﻼﺧ ﻦﻣو ،ﺎﻳوﺪﻳ ﺔﻋﻮﻨﺼﻤﻟا ﺎــﻬﺤﻴﺑﺎﺼﻤﺑ ﻢﻟﺎﻌﻟا ﻲــﻓ ﺔﻴــﺴﻤﺸﻟا ﻪﺑ مﻮﻘﻳ نأ ﻦﻜﻤﻳ رﺎﻜﺘﺑﻻا نإ ةﺮﻜﻔﺑ سﺎﻨﻟا ﺔــﺴﺳﺆﻤﻟا ﻢﻬﻠﺗ ،هﺬﻫ قﺎﻄﻨﻟا ﺔﻌــﺳاو .نﺎﻜﻣ يأ ﻲﻓ ﺺﺨﺷ يأ

"

ﺎﻬﺗﺮﻜﺘﺑا ﻲــﺘﻟا ﺎﻳوﺪﻳ ﺔﻋﻮﻨﺼﻤﻟا ﺔﻴــﺴﻤﺸﻟا ةءﺎﺿ ا تﺎﻴﻨﻘﺗ ﻞــﻤﻌﺗ ﻲﺘﻟا تﺎﻌﻤﺘﺠﻤﻟا ﻦﻴﻜﻤﺗو ءاﺮــﻀﺧ تارﺎﻬﻣ ﻢﻴﻠﻌﺗو ﺔﻴﻠﺤﻣ ﻒﺋﺎﻇو ﻖﻠﺧ ﻰــﻠﻋ "رﻮــﻧ ةءاﺮﺑ ﻰﻠﻋ ﺔﻠﺻﺎﺣ

"

ﺔﻌﻨﺼﻣ ءاﻮﺿأ ﻊﻴﻤﺠﺘﻟ سﺎﻨﻟا ةﻮﻋﺪﺑ ﺔﻠﻤﺤﻟا ﺖﻣﺎﻗ .ﺔﻣاﺪﺘــﺳا ﺮﺜﻛأ ﻞﺒﻘﺘــﺴﻣ ﻖﻠﺨﻟ ةرﺪﻘﻟا ﻪﻳﺪﻟ ﺺﺨــﺷ ﻞﻛ نأ ﺎﻨﻟ تﺪﻛأ ﻚﻟﺬﺑ ﻲﻫو ،ﺔﻴــﺴﻤﺸﻟا ﺔﻗﺎﻄﻟﺎﺑ ﻞﻤﻌﺗ ﺎﻳوﺪﻳ ﺖﻨﻜﻣو ﺺﺨــﺷ ٤٠٠٠ ﻦﻣ ﺮﺜﻛ ﻼﻤﻋ تﺮﻓو ﺪﻗو ،ﻢﻟﺎﻌﻟا ﻲﻓ ﻲﺑﺎﺠﻳإ ﺮﻴﺛﺄﺗ

ﻰــﻠﻋ

ﻦﻣ ﺮﺜﻛأ

WRITINGS ON ART & HISTORY �ا�ا�ك ن�لا � � و ���ا�لا

Christopher Noey

For over 2,000 years, the monumental traces of ancient Egypt have humbled travellers along the Nile. In their presence, we find ourselves – archaeologist or artist, local Egyptian or curious visitor – staring into the immensity of history and wondering if ancient Egypt has a message for us. In the two centuries since the Rosetta Stone began to unlock the culture of ancient Egypt, and the sands revealed its treasures, we have asked, who were these people? What can they teach us? With each new archaeological discovery, we search not only for glimpses of that vanished world, but for clues to making sense of our own contemporary culture.

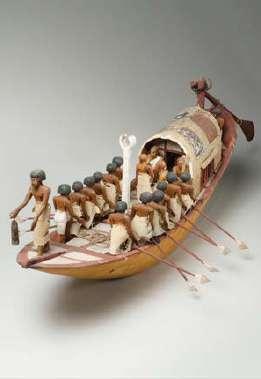

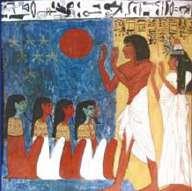

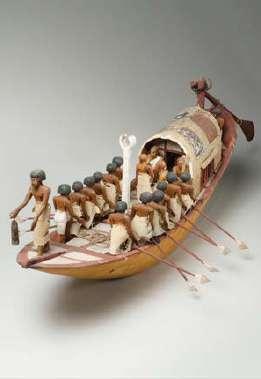

Much of the evidence for the culture of ancient Egypt comes from the tombs and memorial structures that elite patrons constructed to insure a safe passage into the afterlife. Labels at archaeological sites or in museums often tell us that we are witnessing daily life in ancient Egypt, but I approach these objects as extraordinary examples of installation art (even if there was no word for art or religion in this ancient culture). There is no doubt that this material can reveal much to us about life along the Nile millennia ago 1. For example, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and various museums in Egypt contain near perfectly preserved models discovered in the Middle Kingdom tomb of Meketre 2. Among them are tantalizing glimpses of the cattle census used for levying taxes (Fig. 1a), a granary at work (Fig. 1b), and the production of beer and bread (Fig. 1c).

FOREVER IS NOW .02 86 # A NCIENT E GYPT