Woman warrior (onna bugeisha)

Russell Kelty There are quite a few women who are the heads of castles. They brought silver or provisions from their family, took the castle or territories as security, and virtually managed the castle.1

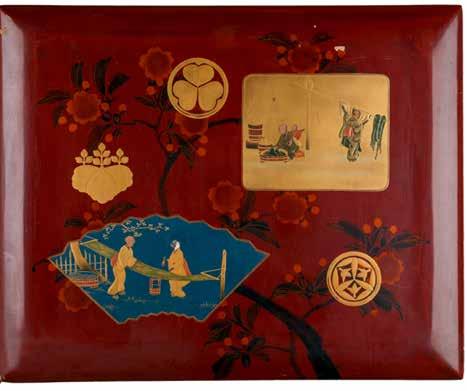

The predominant image of the samurai is a Japanese male in a suit of armour carrying a pair of swords. Dispersed throughout history are accounts of samurai who do not fit that description, such as Yasuke (c.1550–c.1582), an African-born retainer to Oda Nobunaga (1534–1582), as well as samurai-class women, known as onna bugeisha, who inspired their own legends.2 The earliest documented evidence of a female warrior appears in The account of ancient matters (kojiki) written in the eighth century.3 Empress Jingū (c.169–269 CE) is one of the most prominent figures portrayed in The account and describes her military exploits. Empress Jingū was the consort and court shaman of Emperor Chuai (149–200 CE). On advice from the gods, Jingū raised a fleet and invaded the kingdoms of the Korean Peninsula, donning men’s armour and while she was heavily pregnant. Her conquest was swift and successful and she returned to give birth to the future Emperor Ōjin (c.200–310 CE), quell an uprising initiated by her husband’s older sons, and rule until her own death seventy years later.4 In the nineteenth century, Empress Jingū appeared in numerous woodblock prints as a symbol of national pride and by 1881 she was the first woman to be featured on a banknote, her image conceived by an Italian painter. This image of the Empress, created by Katsukawa Shuntei (c.1824), depicts her dressed in fine armour and holding a bow, while a Korean emissary humbles himself before her (fig. 1). During times of warfare, women were often responsible for managing the castle and preparing troops, but at times they also entered the field of battle. Samurai-class women used a long pole with a curved blade at the top, known as a naginata, which became their symbol. In addition to their other responsibilities, they would have been trained as young women to use the nagainata to enhance their martial spirit, with one included in their wedding dowry, along with a small dagger (kaiken) to protect themselves outside the house.5 During the tempestuous sixteenth century, women were placed in control of castles when the head of the clan was away and they became a more prominent part of vast armies of infantry, at times forming their own gunnery detachments. As peace returned to the archipelago, women were expected to be faithful and subservient to their husbands and wear clothing appropriate to his status. Luxurious garments and lacquer ware were their only possessions and displayed prominent emblems of power and prestige (figs 2, 3). 36

fig. 1: Katsukawa Shuntei, born Japan 1770, died Japan 1820, Empress Jingū, no. 1 from the series Triad of martial valour (Buyû sanban tsuzuki), 1820, Japan, colour woodblock print (nishiki-e); ink and colour, blind printing, silver & gold on paper, 21.3 x 18.9 cm (shikishiban) 21.3 x 18.9 cm (image & sheet); Gift of David Button 2004 1 Luis Frois, Historia de Japam, ed. Josef Wicki, Biblioteca Nacional, Lisbon, 1976–84. 2 Thomas Lockley & Geoffrey Girard, Yasuke: a true story of the legendary African samurai, Sphere, London, 2019. 3 Sachiko Hori, ‘The roles of women in the samurai class’, in J. Gabriel-Mueller, Art of armor: Samurai armor from the Ann and Gabriel Barbier-Mueller Collection, Yale University Press, New Haven, 2011, p. 53. 4 Emily Blythe Simpson, Crafting a goddess: divinization, womanhood and genre narrative of Empress Jingu, University of California, Santa Barbara, 2019, p. 4. 5 Sachiko Hori, ‘The roles of women in the samurai class’, in J. Gabriel-Mueller, p. 54.