5 minute read

Math Past

0, 9, 8, 7, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1

Where did the numerals we use today come from? What’s the same and what’s different about the numeral systems we’ve studied?

We have learned a lot about how people throughout the world, both in the past and today, write and talk about numbers! We learned about Chinese number rods.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

We also learned about Maya numerals, which use the shell symbol for 0.

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

We learned about the Yoruba people and how they describe 15 as 5 before 20. We even learned about why the number 12 was important to ancient Egyptians, which is why we see it on our clocks!

All of this leads us to wonder: Where did the numbers we use come from? It turns out to be a complicated story that’s missing a few pieces!

The numerals we use today were created and developed by mathematicians and astronomers in India. They were later passed on to Europeans through translations of texts that were written during the Islamic Golden Age. Because of these two sources, they are called the Hindu-Arabic numerals.

A key person in the development of the Hindu-Arabic numerals in India was the mathematician Brahmagupta (c. 598–670). His book Brahma Sphuta Siddhanta (The Opening of the Universe) appears to be the original text that brought Indian mathematics and their numerals to the Islamic world.1

Another important person in the story is Abu Ja’far Muhammad ibn Mūsā al Khwārizmī, usually shortened to al Khwārizmī. His book On Indian Numbers, which was later translated into Latin, became one of the main sources Europeans used to learn the Indian numerals.2

In fact, according to some scholars, the word algorithm also comes from the work of al Khwārizmī, but only because of a mistake. Some of the translations of his work were not very good ones, and one even identified the author as Algor, a former king of India. Because On Indian Numbers taught people throughout Europe how to do arithmetic and algebra with Hindu-Arabic numerals, the word algorithm came to be named after Algor, since Europeans thought he had written the book!3

Guide students to compare the Hindu-Arabic numerals with some of the other systems they have studied. Show students the following table of the numerals 9, 10, and 11. Explain that the first row shows the Hindu-Arabic numerals, the second row shows the same numbers represented by Chinese number rods, and the bottom row shows the Maya numerals for 9, 10, and 11.

1 Jeff Suzuki, Mathematics in Historical Context, 78–79. 2 Suzuki, Mathematics in Historical Context, 86. 3 Suzuki, Mathematics in Historical Context, 86.

9 10 11

Ask students what they notice about the three different ways to write 9, 10, and 11. What’s the same about each system? What is different? Remind students that the boxes used with Chinese number rods are not part of the number but are used to show place value.

Students might notice when looking at the column for 10 that the Chinese number rods do not have a symbol for 0. Instead, the box is empty. They might also notice that Hindu-Arabic numerals and Chinese number rods both use a new place once they get to 10, while the Maya numerals keep going without a new place.

Next, show students the different ways of writing 19, 20, and 21. Again, ask students what is the same about the numerals and what is different about them.

19 20 21

Students might notice that the Maya numerals use a symbol for 0, a shell. They might also notice that starting with 20 Maya numbers show the larger place value vertically. The dot in the Maya number 20 has a value of 20. Similarly, with the Maya number 21, the dot on top has a value of 20, and the dot on the bottom has a value of 1. Our system uses place values based on the number 10, but Mayan place values are based on 20. Ask students what they think is useful about the different numeral systems. You can also ask students these questions to prompt discussion: Why do you think the systems have so much in common even though they look different? Why did we end up using Hindu-Arabic numerals instead of another system, like Maya numerals?

The Hindu-Arabic numerals and the Maya numerals developed independently. Because the Maya people are located in Central and South America, as far as we know, there was no contact between the people there and the people of India until centuries after the development of both numeral systems.

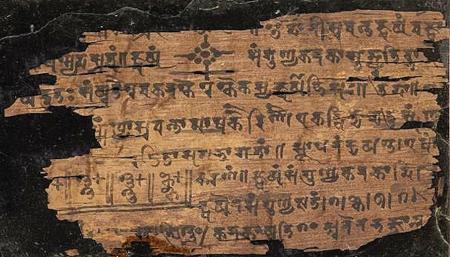

The relationship between the Hindu-Arabic numerals and the Chinese numeration system is less clear, however. There is evidence that these groups of people shared ideas, mostly due to the spread of Buddhism from India to China in the first century CE. However, the historical record isn’t clear on who contributed what to the numeral systems and when.4 The Bakhshali manuscript, shown here, is one of the earliest known examples of Hindu-Arabic numerals. As you can see, they look very different from the numerals we’re used to!

None of these systems is better or worse than any of the others. We use Hindu-Arabic numerals in America because they spread

4 Suzuki, Mathematics in Historical Context, 78–79.

throughout Europe in the period of time just before various European countries colonized other parts of the world. During that time, Europeans replaced the indigenous numeral systems with Hindu-Arabic numerals because they were used to them. This is similar to how Europeans forced the replacement of indigenous languages with their own languages, such as English, Spanish, and French. The Hindu-Arabic numerals weren’t created all at once. Instead, they developed in a similar way as language, over time, and with different people contributing to their development. New ideas were added as they were needed. As we’ve seen throughout the year, incorporating different perspectives of mathematical thinking makes us stronger mathematicians!