Pierre Huyghe

Life or something like it…

Pierre Huyghe

Life or something like it…

To enjoy the artwork you need to stand on the DLR platform (towards Woolwich Arsenal) between 8.30 to 10:00 AM on weekdays. Look at the legs going towards the Jubilee Line through the glass wall to your opposite. One could make a video artwork out of it. But I would prefer the live artwork in person.

S. R. Jimmy

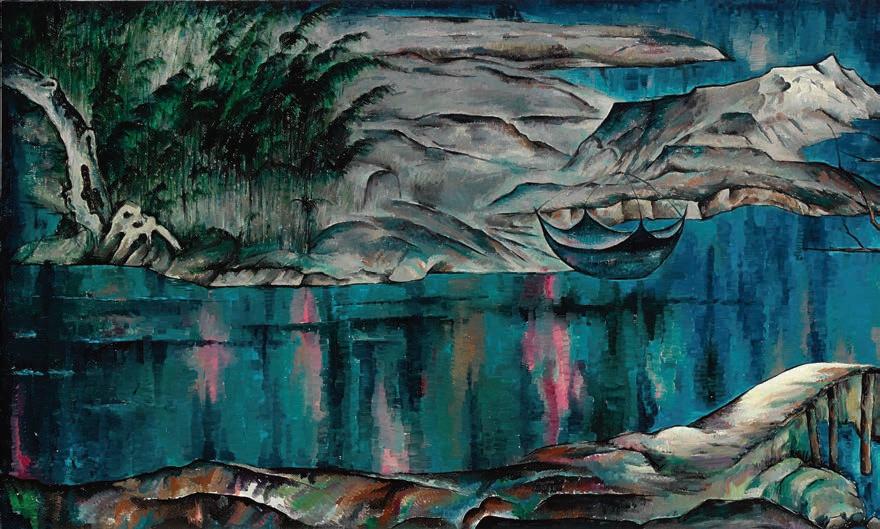

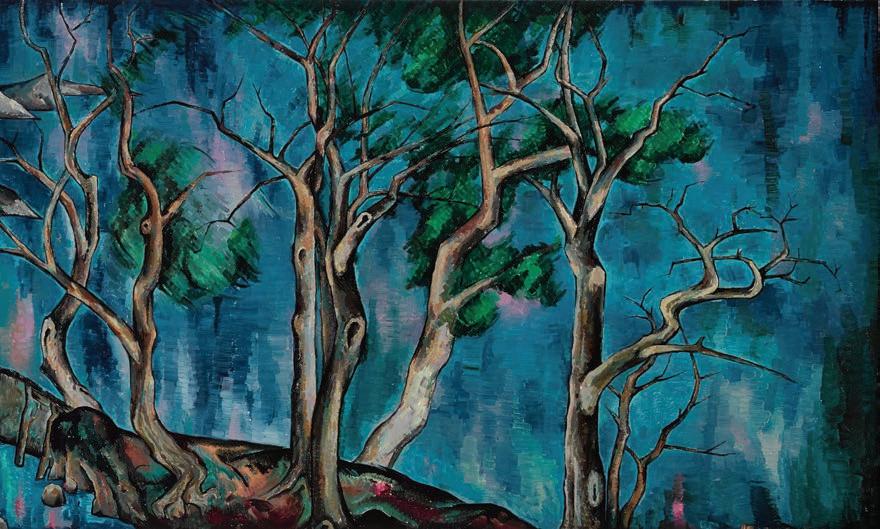

Unknowability is hardwired into the world. Chaos theory tells us that the complex systems shaping our experience of the world cannot perfectly be predicted; recent financial and ecological crises have provided ample proof of humanity’s hubris in presuming otherwise. It is impossible to know, when the butterfly flaps its wings in Brazil, whether or not a tornado will ensue in Texas, and so, while the gap between what should and what will happen may be infinitesimally narrow, it remains unbridgeable to anything but God. Pierre Huyghe creates situations in which these conditions operate on a smaller scale, alerting us to the fact that we can never fully grasp the world or know what the future holds.

During a 30-year career the artist has created a body of work encompassing environmental installations ranging in scope from domestic aquaria to abandoned ice rinks, the documentation and reenactment of a research trip to Antarctica, innumerable works in diverse media playing on the themes of memory and identity, and open-ended collaborations between human and nonhuman intelligences such as the masked monkey pottering around what appears to be the Fukushima Exclusion Zone in the 2014 film Human Mask. In each of these the artist-as-creator is figured as something between watchmaker and gardener, creating systems and setting in motion their constituent parts without intervening to dictate their behaviour. He describes his position in relation to the work as being “upstream” from it; his role is, he tells me by email, to “conceive the conditions” in which things happen “rather than trying to invent for the sake of it”. He builds worlds and watches them play out.

I remember entering one of them on a sunny afternoon six years ago. A friend and I were walking through a field of wildflowers on the outskirts of Kassel, past a heap of stone debris and stacks of concrete

slabs, when we came upon a clearing charged with the warm buzz of bees. Beside an uprooted oak tree was a cast-concrete sculpture of a reclining female nude with an ovoid honeycomb hive for a head –source of the hum – past which trotted an elegant white greyhound with a pink-painted foreleg. We knew that these diverse elements constituted an installation by Huyghe for Documenta 13 with the double-take title Untilled (2011–12), but there was little way of knowing where the artwork ended and the outside world began.

The dissolution of boundaries between reality and representation has characterised Huyghe’s practice from the start. For Chantier Barbès-Rochechouart (1994), one of a series of billboard projects, Huyghe photographed actors posing as labourers at a construction site. The image was then posted onto a hoarding overlooking the location so that the real workers, when they returned to the site, were confronted by their own reconstructed selves. Remake (1994–95) restages Alfred Hitchcock’s Rear Window (1954) using amateur actors; for No Ghost Just a Shell (1999–2002) Huyghe and Philippe Parreno purchased an off-the-shelf manga character named Ann Lee and loaned her out to artists including Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster and Liam Gillick. The equally slippery A Journey that wasn’t (2005) started with Huyghe embarking on an expedition to the Antarctic in speculative pursuit of an albino penguin, an evolutionary detour of the artist’s own invention, and ended with a hulking mechanical version of the animal clambering across the ice rink in New York’s Central Park during an operatic production based on the journey. Huyghe told the art historian George Baker in a 2004 interview that ‘we should invent reality before filming it’, and these works go beyond the mere confusion of fact and fiction to question how our experience of the world is constructed.

Back in 2012, my friend and I struggled through a thicket of brambles in pursuit of the pink-legged dog (named, we later discovered,

The artist relinquishes a degree of control over the scenarios he has created, so the viewer is encouraged to give up any illusion of fully understanding her place within and influence upon them

by Mark Rappolt

by Mark Rappolt

‘With-it art worldlings have known for a while that the toughest, hairiest, of the searchingest, outpost of the avant-garde is the Jean Freeman Gallery at 26 West 57th St.,’ claimed Grace Glueck in The New York Times of 24 January 1971. Since the summer prior the gallery had been advertising in Artforum, Art in America, Arts Magazine and ART news with stylish, if unremarkable, black-and-white photos of Land art accompanied by an address in the de rigueur sans serif. As Christopher Howard writes in The Jean Freeman Gallery Does Not Exist, the fact that there was no number 26 (and thus no gallery) on 57th – then the commercial centre of the New York artworld – seemed only to intensify the sense of intrigue around the gallery.

The subject of Howard’s book is Terry FugateWilcox, a moderately successful but little-known and little-remembered Land artist, and his Jean Freeman Gallery, a space that existed, unbeknownst to most people at the time, in print only. Through archival deep-diving, Howard recounts the work that went into this brief but curious hoax – articles were submitted under pseudonyms, opening parties were held with the fictional artists apparently in attendance and a redirection for a fake address was set up. Remarkably, Fugate-Wilcox was rewarded with cheques from collectors reserving unseen artworks and slides from artists seeking representation – and enough credibility to warrant

investigation by a particularly inquisitive New York Times journalist, who, in the article mentioned above, called it ‘the non-gallery of no art’. But enquiries continued to arrive.

The work of Fugate-Wilcox is less engrossing than the way in which Howard places it in a curious time in the artworld and uses it to illustrate the self-imposed paradox of Conceptual art: the need for documentation, and the inadequacy of that documentation as proof that the object portrayed exists. This was a movement reliant on the art magazine to prove both its existence and its worth, as demonstrated by the Jean Freeman artists’ use of media such as the air above the Empire State Building or a lawn mown in a particular direction – works that, even if the gallery had existed, would have only been shown via their documentation.

‘Jean Freeman existed for anyone who suspended disbelief and understood the ads, press releases, and image sheets as a true space for exhibiting art,’ writes Howard. That Conceptualism allowed artists and artworks to be ‘fictional yet no less genuine’ is fairly straightforward, but in this tightly researched and compelling investigation into the brief moment in which Fugate-Wilcox (and others such as Dan Graham) co-opted advertising as a fine-art medium, Howard draws out a pertinent, if cynical, point about the ecology of art magazines – that there

is no clear delineation between the artwork and the advert. Galleries are commercial businesses selling luxury goods, and they sell their goods and massage the egos of their customers (and artists) as any other business would – through advertising. The artworld considers itself above commerce, Howard continues, but ‘only reluctantly acknowledges that a signature style is also a brand’. A dispute over a billboard Fugate-Wilcox used as the site for public sculpture, in breach of government regulations, saw his lawyers argue that artwork, as self-promotion, is advertising. On the surface the Jean Freeman project is an amusing practical joke at the expense of the art establishment’s bureaucracy, patrons, collectors and hangers-on. And it is true that Howard’s research into Fugate-Wilcox’s career reveals a history of orchestrated piss-taking: submitting passport headshots in which he and his wife appeared to be nude – and consequently ending up on a fraud watch-list – or selling shares in San Andreas Fault via the pastiche legalese of the fictitious ‘Crack in the World Company’. But in The Jean Freeman Gallery Does Not Exist, Howard deftly threads this not particularly momentous (or much-noticed) project into the development of Conceptual art, showing it to be a particularly hard-nosed impression of more-celebrated artists’ attempts to dispense with the act in favour of the idea. Lucy

WatsonInvited to contribute a social study about African Americans to the 1900 Exposition Universelle in Paris, specifically the Exposition des Nègres d’Amérique, which was intended to showcase to the ‘thinking world’ the range of black American achievement in the 35 years since the end of slavery, sociologist W.E.B. Du Bois, together with his team of researchers and designers at Atlanta University, created 60-plus data visualisations that charted, in bold colours and highly expressive graphics, the results of investigations into the black American experience. Though widely known and studied, particularly

in the context of Du Bois’s proclamation that ‘the problem of the 20th century is the problem of the color-line’ – that the legacy of the Atlantic slave trade, as opposed to any innate failing, and in the face of ‘scientific’ views positing the race’s status in social Darwinist terms, was responsible for the precarious state of African American life in 1900 – these 63 infographics are published here, according to this work’s editors, for the first time in full-colour book form. Essays by sociologist Aldon Morris and cultural historian Mabel O. Wilson provide background on the bar charts, cartography, spiral diagrams and ‘heat’ maps,

framing their cultural and historical impact, while designer Silas Munro analyses their aesthetic significance, introducing the plates and providing detailed captions that comment on media, tools, style, design traditions and history, and interpretations. Here the experience of reading charts not for the information they were intended to convey but for the forensically revealed details of their creation bumps up against content, elegantly encapsulating the evocation of a ‘nation within a nation’ that Du Bois and his team masterfully presented in Paris at the turn of the last century. David Terrien