+BZ Zhang

+Arnolfo

+office ca

+Niloufar Emami

+BZ Zhang

+Arnolfo

+office ca

+Niloufar Emami

+Besler and Sons

+LAA Office

+Kate McLean

+J. Drew Rogers

The Ricker Report is a student-run journal published by the University of Illinois School of Architecture. Originally founded as Ricker Notes, a periodical edited and published by students, featuring articles, news, poetry, drawings, and book reviews. In 2018, Ricker Notes returned in the form of Ricker Report. The goal of the new Ricker Report is to provide a platform dedicated to exploring cutting-edge topics in architecture, design, and the built environment. Named after Nathan Clifford Ricker, the first architectural graduate in the U.S., the first licensed architect in the state of Illinois, and a pioneer in architectural education who helped establish the architecture program at the University of Illinois. The journal serves as a venue for showcasing innovative research, critical analysis, and creative projects. By fostering a dialogue between academic inquiry and professional practice, the Ricker Report highlights the diverse voices shaping the future of design, sustainability, and urbanism.

To look beyond the silhouette of architecture is to explore ideas and implications of transformation, innovation, identity, adaptation, and space. Viewing architecture as a language allows us to evaluate its strengths and limitations in a modern world.

The following issue of the Ricker Report aims to challenge expectations and translate the various contexts in which architecture can exist. This publication is curated to highlight the messages and missions of our featured artists, architects, researchers, and creatives, while also exploring their proximity to the field through their unique explorations of architecture. We seek to provoke nuanced questioning of the universality of architecture, both as it is traditionally defined in Western society and as its boundaries are interrogated.

The act of translation is a cross-cultural emulsifier—taking something and making it lucid in an alternative language, dialect, culture, ideology, medium, time period, and countless other dimensions. Translation, when treated as transcription, is born with discretion, variation, and limitation, each with its own conceptual and legitimized power. Herein lies the potential of architecture: as a tool, a weapon, a mediator, a creator, and a translator.

Throughout this edition of the Ricker Report, we question whether architecture is universal, or if the uniqueness of each translation—shaped by local culture, labor practices, and environmental conditions—gives a space its identity. These translations seek to explore the nuanced role of architecture as a mediator—an interpreter of culture, imagination, and identity.

In a world where spaces often serve different purposes than originally intended, how does architecture adapt? How does it maintain relevance across diverse settings and truly serve as a universal language?

Editor-in-Chief

Emilie Cooper

Art Director

Xiaoyi Zhu

Director of Operations

Valentina Elias Domiano

Graphic Designers

Franchesca Austriaco

Giorgio Riccardo D’Attoma

Isabella Delgado

Minal Sarkar

Lead Editors

Beni Lawson

Pushpanjli Mehra

Meng-Che Daniel Tsai

Editors

Aiden Callow

Julia Davis

Athena Ly

Brady Monahan

Erin Nibeck

Henry Sloan

Riley Vernon

Faculty Advisor

Joseph Altshuler

Bz Zhang, NOMA, AIA, is a Los Angeles-based artist and architect who employs the tools of architecture to imagine futures beyond settler colonialism, racial capitalism, and cisheteropatriarchy. They organize with Dark Matter U, the Design As Protest Collective, and the Los Angeles Neighborhood Land Trust. Bz is a 2022 JournalofArchitecturalEducationFellow, 2021 USC Citizen Architect Fellow, and a licensed architect in California.

Bz’s professional experience includes collaboration with contractors and fabricators in Philadelphia, architects and nonprofits in the San Francisco Bay Area, and artists and land trusts in Los Angeles. Their teaching practice has developed in collaboration with students and co-instructors at the University of Southern California, California College of the Arts, University of Michigan, University at Buffalo, University of California Berkeley, Jefferson University, and Brown University. Bz received a Master of Architecture from UC Berkeley, and a BA with Honors in Visual Arts from Brown University. In their free time, they enjoy exploring the Los Angeles River in search of birds and discarded objects.

In your past experience, how have you observed your identity and background be translated into spaces?

There’s often an assumption of public spaces as neutral, but they are actually—for a vast majority of people—spaces where, at any moment, you may suddenly feel not totally secure. For me, in both the queer community that I have built and also with my blood-related family, who are Chinese and not necessarily queer, these communities (and others) have been really good at appropriating space and reworking space to serve our desires and needs.

Growing up, my mom was part of founding a Chinese language school, so we would have Chinese school on the weekends, and it would always be in some random place that wasn’t really built for that. And all these aunties and uncles would come in the morning and set everything up. We would have cultural dance classes, we’d be learning the Chinese language, there would be food, and it would feel like its own universe. And then, in the afternoon, everything would get packed away and back into everybody’s cars. It was all gone. I took that for granted for so long without realizing how magical it was.

I think there are so many different instances where, in a world that’s not built for us, we transform space. And that’s also something that I like to uplift because there’s a lot of pressure in architecture to create something new out of nothing, the tabula rasa, the blank slate. And there’s so much magic and joy in taking something that’s there that maybe was never meant to include you and then transforming it somehow. How powerful is that?

Anybody who comes from identities or communities that have been marginalized by the majority will have an experience of translation; we can call it code-switching; we can call it a number of things, but it is essentially knowing that one thing can be said, but it can mean another thing. Yes, we all have that, but to me, I like to name it and contextualize my work in terms of translation. Not as literal translations, but actually, just these small and big moments where we are either aware that a translation is happening of some kind or willfully ignorant of it.

I recently had an example in a project with the land trust, where we were working with our landscape architects who are not Indigenous. In our Western training, we used the word environmental— environmental report, environmental constraints—and we took that to mean the technical details about the industrial history of the brownfield sites with the project. So when we said environmental, we were thinking of federal regulations and so on. Still, we have all of these community partners, including talk about partners where we combed through all of our presentations and reports and changed that word to just “industrial.” Although it wasn’t the correct word when speaking within our fields, it was the better and more appropriate word for our community partners. These little moments, not huge moments, minute by minute, second by second, make a space more inviting and welcoming, allowing a greater number of people to participate.

When I say the ongoing practice of translation as a deep inquiry and how power and narratives shape each other, it is a reminder to myself that it’s an everyday thing. I can just acknowledge that there is some translation happening right now between us, that I can’t assume that what I’m saying makes sense to you or that I understand everything you are saying. And then, in terms of power and narrative, how do we create shared meaning? If we acknowledge that we may not 100% understand each other right off the bat, and there is some kind of translation happening between us, then the creation of shared meaning or mind meanings is created. This is my commitment.

How has your ongoing inquiry into how power and narratives shape one another sparked inner dialogue and external expression?

What pieces of your work represent this commitment most accurately?

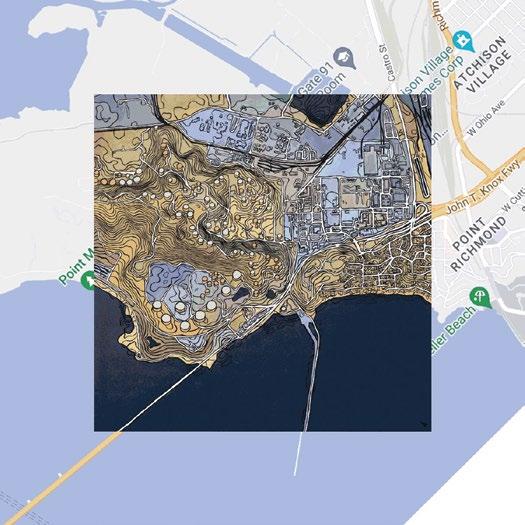

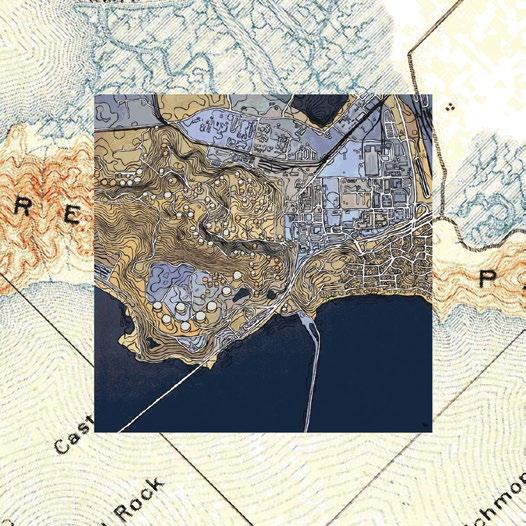

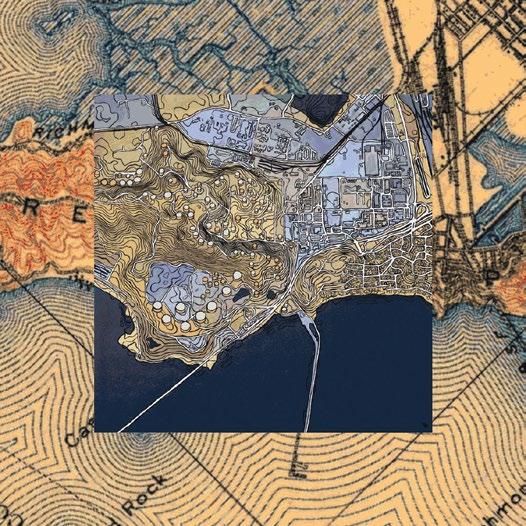

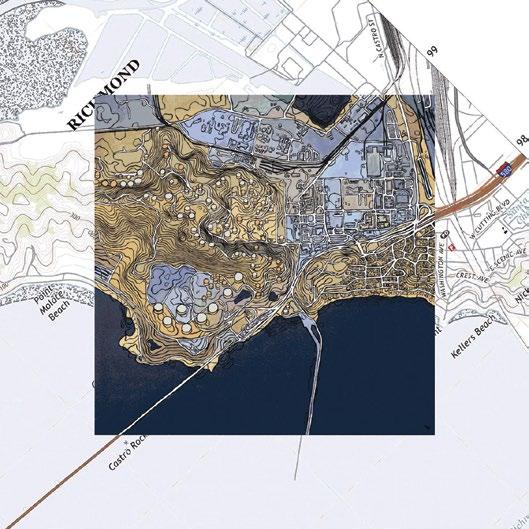

There’s a painting I made recently, Crude Neighbors: Chevron Refinery, Richmond, California (2022). It’s 36 inches by 36 inches, and it’s acrylic on canvas. It’s an oblique parallel projection, set to a scale of 1:250, which is an engineering scale. What I’m depicting here is an oil refinery in the Bay Area using data from OpenStreetMap, USGS, and NASA. And in those publicly accessible open sets of data, they do not include any information on the refinery or representation of it. They include roads, houses, freeways, and railways, and I think that the refinery is an interesting omission. That’s not surprising, because we as the public are not meant to be looking at those kinds of landscapes: these petrochemical landscapes or landscapes where there are so many struggles over resources. In all of these cases, the public is not supposed to know what’s going on. So when we think about translation, we also think about power and narrative; this work is a really big example of me thinking through that.

So there’s a couple layers of translation in this piece. I’m taking datasets that are open source and used all the time by folks in our field, and I’m using them in a pretty different way. It’s not necessarily about being innovative, but it’s about shifting the frame and looking at something else with those same exact tools that we already have. It always makes me wonder what other kinds of things we would see.

In the pragmatic side of my practice, which is working for a land trust, I’m talking to city officials, we’re writing grants, we’re getting public funding, and we’re partnering with community-based organizations. And so in my more research and art practice, I tend to lean towards a more curious and exploratory approach of, “What else does this do?” By “this,” I mean architecture, but what does architecture do besides the literal transformation of physical space into place? What about cultural ideas of space? What about powerful stories that we tell about what’s here and what’s not here? Or what and where do we consider home? And where do we consider away? Or elsewhere? How do we thoughtfully address that reality? Identify where those lines are drawn? And by whom? For what purpose?

Crude Representation(s): Chevron Refinery,Richmond,California, 2022. Acrylic painting framed by various datasets.

So, there’s the translation of the publicly available data, and I’m translating it from a digital set of lines into analog. The tension of taking it out of the digital and putting it into the analog made it less precise. On the other hand, I was able to add elements of what was really there, in terms of the refinery—these huge oil containment tanks and other details that are sort of hidden in there from historical maps—so in one way, it’s become less precise. In another way, the translation becomes more accurate.

This piece is paired with this little animation, showing some of the other sources of what I’ve looked at. I’m reflecting on and wanting to have conversations with other folks about how much we take for granted regarding the models that are given to us about our worlds.

You may notice one of the maps that I am overlaying in that moving image is Google Maps. I always talk about how the most bizarre thing about Google Maps is how these massive freeways are flattened. When we look at it from above, they look like other roads. To me, that kind of softens and hides the violence. What freeways historically have been used for are these settler colonial tools of displacement, moving military, moving capital, and moving oil. That’s what the freeway system was built for: the movement of the army and the violent removal of communities.

What design pieces or specific projects hold personal significance for you? What is the story behind it and inspiration that fueled its development?

The Gender + Sexuality Resource Center was an interior spatial design project that I was invited to do by the Gender + Sexuality Resource Center staff at Princeton University. The building is a historic building, so we couldn’t change anything about the building inside. The 2,500 square feet within the building had been disconnected for a long time and have not been considered as one. It was an LGBT student center on the one hand and then a women’s center on the other hand, and they had different histories. There are a lot of different perspectives that were important here, and there were a lot of concerns about bringing the two centers together. Many of the questions came from a place of wondering what might be gained and what may be lost in merging. Previously, if I am a queer woman or a trans woman, or I am anybody assigned female at birth, do I have to pick one? That was a big concern for a lot of people as to why it makes sense to bring those two centers together.

On the other hand, other people were concerned that this was the university potentially consolidating two affinity groups in order to give them fewer resources, and I think that was also a legitimate concern to me. When I presented it to them, I recognized that a lot of what we’re going to be doing is listening, and not just listening, but synthesizing. Anybody can say I’m listening, I’m hearing you, but it’s the power of translating what was heard into something that actually reflects back to all those stakeholders and what their experience was. We budgeted a lot of time for me to reach out and conduct community interviews to talk to a lot of students along with the staff.

There are certain things that we did, like the removal of a couple of specific doors, which then became the hallway connecting the two centers that were previously separate. In other ways, we maintained privacy with the interior windows connecting the space to the hallway. Nobody is trying to out themselves just by walking into a center to get some information. Between those two details, there isn’t a one-size-fits-all. We know that inherently, as designers, especially when putting that into practice in a place where it’s not entirely safe right now, the stakes can be quite high. As a designer, there’s only so much I can do in terms of using visual strategies. We used a motif of curves nesting and intersecting, which we painted on the walls to sort of draw our eyes and find these little interesting compositions that make us want to look further. They were meant to connect the space and make it feel cohesive and inviting, sparking curiosity to say, “Let me see what’s in that room that’s further down my line of sight.” Other than that, a lot of it was conversations about comfort and ease. To serve the people that we’re designing for, we just need to hear what they’re saying to us.

Detail from redesign of Princeton University Gender + Sexuality Resource Center, 2021.

How do you interpret the term “practice” in your context of architecture? And how do you believe it can be understood and translated to a diverse audience?

When I dream of the future of practice and how I orient myself currently towards that future, I think about widespread accessibility for all communities and all peoples to use the tools and potentials of the design disciplines to transform the world around us. I think it’s a place that we can get to because it’s sort of a place that we came from. We can trace how we got here, which means we can go somewhere else. And the last thing I’ll say about practice for now is that when I use the word practice, I’m thinking about it in terms of practicing, as in repeating and learning to get better and to grow. So both in terms of the practical everyday work of building a house or building a park, but also the everyday and longer-term view of transforming our discipline into one that we all deserve.

“ TO SERVE THE PEOPLE THAT WE’RE DESIGNING FOR, WE NEED TO HEAR WHAT THEY’RE SAYING TO US.”

- BZ Zhang

LAA Office is a multi-disciplinary design studio based in Columbus, Indiana. The studio collaborates with communities of all scales to create public art and shared public spaces.

Lulu Loquidis, PLA, ASLA, is a registered landscape architect and co-founder of LAA Office. As a designer and project leader with international firms such as Hargreaves Associates and AECOM, she has developed a diverse portfolio that includes gardens, streetscapes, urban plazas, waterfront parks, and resilience infrastructure. She believes that contemporary landscape architecture is a vital bridge connecting the environment, art, and human culture. Her current work centers on transforming underutilized spaces through art and design to foster social life and revitalize communities.

Daniel Luis Martinez, co-founder of LAA Office, is an architectural designer and educator. His research and creative work explore the transformation of undervalued sites through the integration of public art and public space design. He currently serves as the Director of Indiana University’s J. Irwin Miller Architecture Program and is a faculty affiliate of the Center for Rural Engagement. In 2022, he participated in Art Omi’s Architecture Residency in New York, was named an Exhibit Columbus University Design Research Fellow in 2019, and received an AIA Henry Adams Medal in 2012. Martinez has worked at leading architectural firms, including Allied Works and Weiss/Manfredi, and his writing has been featured in prominent architectural journals such as Mas Context, San Rocco, Clog, and Drawing Matter.

Why do you believe the intersection of landscape, art, and architecture is so important in your multidisciplinary approach?

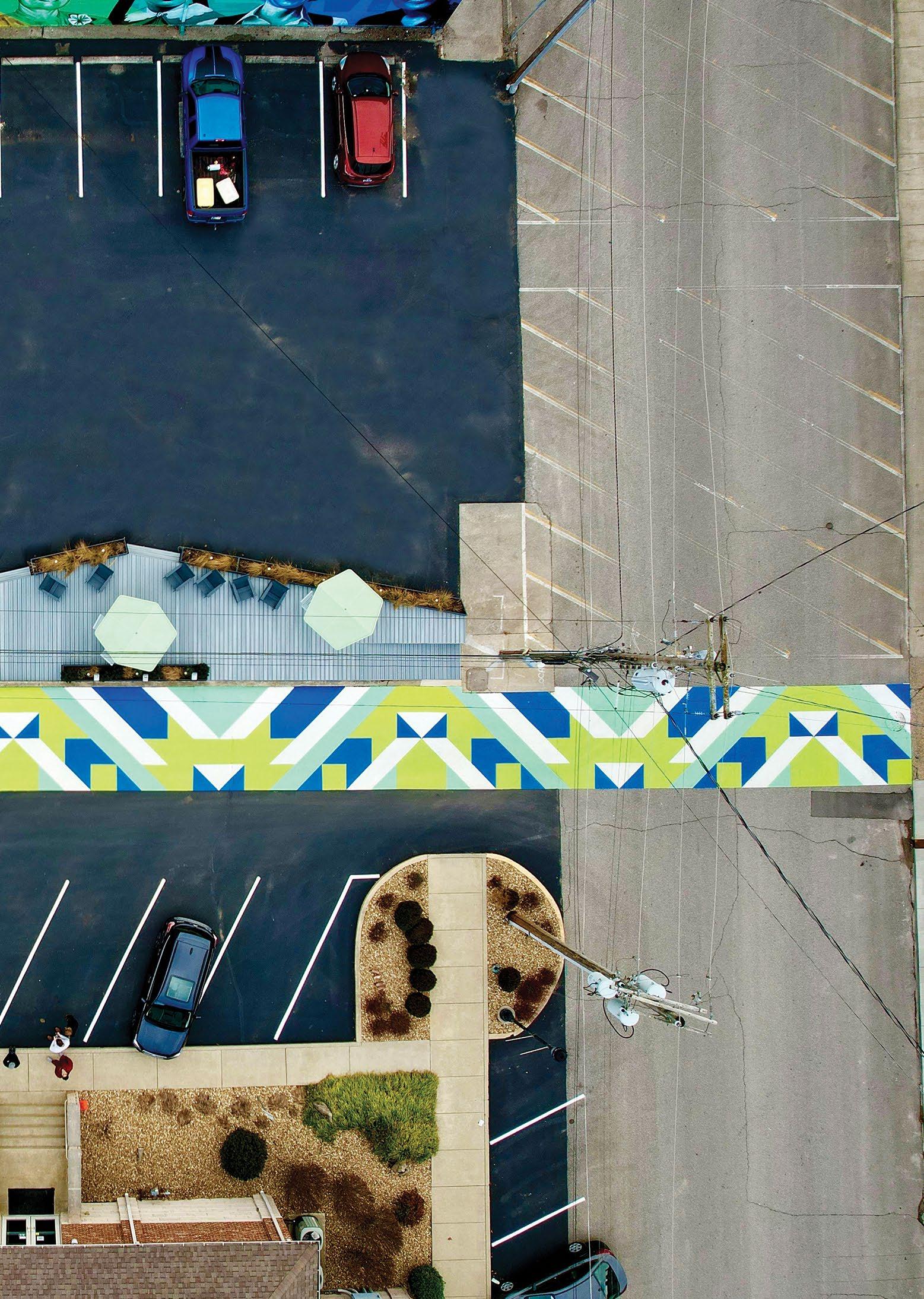

When we had the opportunity to start our practice, we were interested in finding an approach that merged our professional interests with our love for art. An important aspect of our process involves developing artwork to explore design ideas through color and pattern. We did this, for instance, with a public artwork for the city of Ann Arbor called Urban Fetti. In many cases, these early works have been catalytic in driving the final built urban intervention. Heritage Park in Salem, IN, and the 6th Street Arts Alley project in Columbus, IN, both demonstrate how we think of public art as a transformational tool for urban spaces.

The Learning Patterns exhibition, which ultimately ended up driving the 6th Street Arts Alley project, started with an exhibition design showcasing research with the library’s archivist, Tricia Gilson. During our research, we discovered beautiful drawings that I.M. Pei’s studio created while laying out furniture for the library. Those drawings inspired us, and we began rearranging the simple elements of a room to create textile-like paper cuttings. We initially developed a body of work for the gallery but wanted to extend the exhibition to the scale of an urban intervention. This resulted in us scaling up one of the patterns to create a mural on the gallery’s east facade. Soon after the opening, the local Visitor Center reached out and asked us to think about creating a space for dynamic art programming and community activities. The project that emerged from that is now known as the 6th Street Arts Alley.

DANIEL:

We’re interested in how, through shifting scales, we can have a modest studio practice that also addresses something seemingly more daunting, like urbanism. We live in a time where movements like Tactical Urbanism and Creative Placemaking have significantly impacted the way we think about cities. These movements rely on small-scale, incremental, and collaborative approaches to city building. We particularly like the idea of working at the scale of the neighborhood or street and have done a lot with simply painting, for example. The fluidity of painting has provided a chance to flesh out conceptual diagrams at the scale of an urban block with the potential to impact how people see or use that space. The scalar translation of going from something like a quilt, a drawing, or a particular pattern to then asking: how does that work as part of the fabric of a street? We are now having conversations with the Columbus Area Arts Council about the future of 6th Street. We are thinking of orchestrating the largest-ever Sol LeWitt wall drawing on the ground in collaboration with community members. We want to create a situation where many people are responsible for painting a single line. We like that Sol LeWitt worked with scalar translations in similar ways through the instructions and diagrams for his wall drawing series. Could that thinking be used for urban art?

LULU:

The opportunity to work in this manner has allowed us to engage the community in unique ways. For instance, in Salem, IN, we proposed a contemporary design in a context where you may not typically find this design aesthetic. To make it more approachable and meaningful, we worked with the patterns and geometries commonly seen in rural barn quilts. This approach resonated with the community members and softened barriers. The final pattern for the mural was implemented with community involvement and the project ended up being very loved and accepted.

How does the relationship to your work differ in a Midwestern mid-size city compared to other contexts you have worked in?

DANIEL:

The context does differ greatly. In our case, we moved to Columbus from New York City, where we had been working and practicing for about seven years. We worked with some really good offices and talented people who were invested in the public realm and who were also very interdisciplinary. That experience happened at a very high level and was much closer to what some people call Capital-A Architecture. When we landed in Columbus, we realized that we were interested in starting from the opposite side of the discipline to address contexts that are often overlooked or that fly under the radar of the profession.

Columbus, of course, has a rich history in architecture and modernism. The city has realized buildings of great quality here since the 1940s. We were thinking of how to intervene between the architecture as a way of creating a different dialogue while also bringing new ideas and energy that we experienced in New York to Indiana. We wanted to activate our downtown, which is more than a little sleepy. There are many organizations and community leaders in Columbus looking to bring life to our downtown area, and surely, many others in Indiana feel similarly about their homes. There are opportunities within these communities to experiment, borrowing some ideas from Tactical Urbanism, for instance, which is premised on low-risk investment with the potential for very tangible rewards.

We also think that many little points in the constellation of contemporary practice are pushing in exciting new directions beyond the Tactical Urbanism playbook. Things don’t have to be explicitly D.I.Y. or fully participatory and collaborative in the design process. Designers can still retain some authorship, and we certainly do so in our work. But we like the idea of a ground-up approach and thinking outside of the confines of architectur-

al production, which is extraordinarily expensive. How do you bring some interesting vibe and character to a place without investing in a $20 or $30 million-dollar building? The lasting impact of this type of work is far more connected to experiencing a moment and one’s memory of it than the piece itself as a built object. Projects like 6th Street seek to create an architecture that isn’t purely physical.

LULU:

Many of our current projects arise from a strong community need, and funding is always a challenge. Most of our work is funded through grants, and we strive to make as much impact as we can with few resources. Once we have completed the first phase of a project, we hope that the community recognizes the potential and continues to invest in the project. This has been a really interesting way of starting a project and differs significantly from the traditional RFP process that we experienced while working for firms in New York City. Our work is very grass-roots. In many cases, we’re pitching early ideas to mayors, community members, and key stakeholders, then strategizing on how to get it done.

DANIEL

The self-proposed or self-initiated project is related to one interpretation of Placemaking. Rather than thinking of Placemaking as the physical transformation of an underutilized space, which is certainly one valid way of thinking about it, one can think of how people or narratives that are currently omitted from a context can be made visible through a designed intervention. We’ve used this way of thinking for our current project in Marion, as well as Heritage Park in Salem. Visualizing lost or marginalized histories hints at a less physical dimension of Placemaking..

Could you elaborate on the ephemeral quality of your work, especially in the context of public art, landscape, and architecture, and how it intersects with the concept of public memory?

The discipline of architecture has always been influenced by what happens in other areas of the art world. And we are seeing the influence today of what has been happening for several decades through the work of site-specific installation and performance-based artistic practices. Architecture is something that has always been in dialogue with site-specificity, but the impermanence of an installation offers other opportunities that can, at first, seem antithetical to traditional urbanism. I’m excited that this provides different ways to think about urban space and our relationship and engagement with one another in cities.

The 6th Street Mural and the Learning Pattern Mural were never meant to be permanent. Our goal was to push boundaries and see if these ideas and interventions could evolve into something more permanent. We see this project as a catalyst for testing how our community organizations and patrons use the space. Presently, we’re working on a proposal with the city that considers a seasonal street closure. By redoing the mural, partially closing the street, and introducing new programming and activities, there’s potential for this to evolve into a larger project. It’s been fascinating to see how this project began with a mural in an exhibition and has grown into something much larger in scale and scope.

“IF SOMETHING EXISTS, THEN WHAT YOU CAN DO IS ATTEMPT A TRANSLATION OF IT, WHETHER IT IS THROUGH SCALE, MEDIUM, OR YOUR PROCESS.”

- Daniel Luis Martinez

LULU:

Each project brings its own history and inspires us in different ways. It is important to research and learn as much as we can about the history of a site or the specific theme/program that is driving the project. One of our recent projects involved exterior improvements for a new maker space in Columbus, IN, called Propeller. The site has a rich history tied to aviation, so we began with a historical analysis, drawing inspiration from the themes we uncovered during that research. This serves as a starting point, but we also consider the context, nature, and art. Our initial analysis, whether site-specific or historical, informs the early patterns commonly seen in our work and helps ensure the project feels contextual.

DANIEL:

There have been several. We’re influenced by the work of Roberto Burle Marx, for instance, who was a landscape architect and painter who did a lot of work in Rio. He found ways of mixing colonial and indigenous influences through forward-thinking work that blurred the lines between his artistic practice and urbanism. We have also been influenced by conceptual artists (like Sol LeWitt, who we mentioned earlier) and by a combination of Tactical Urbanism, Placemaking, and Site-Specific Installation work that has pushed architects and urbanists into more ephemeral territory.

What were your major inspirations when creating these projects?

Are there any upcoming projects or goals that you are willing to share?

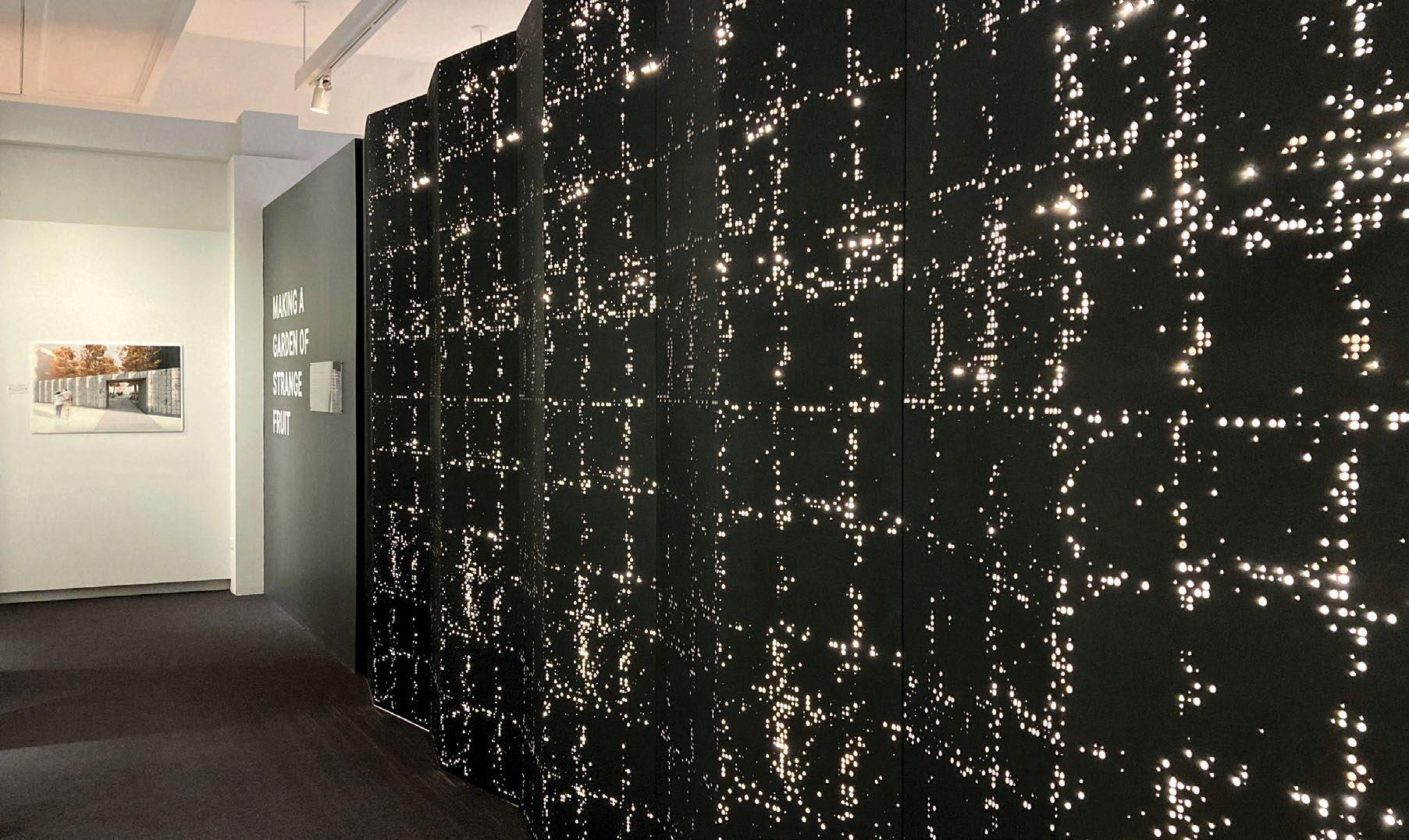

Our project in Marion with Indianapolis-based artist Samuel Levi Jones, which was the subject of our installation for the Chicago Biennial this year, deals with an incredibly tragic history in the town of Marion, where a lynching took place in 1930. That event had the added significance of influencing the lyrics of a poem called “Bitter Fruit” by Abel Meeropol, which was then recorded and performed by Billie Holiday as “Strange Fruit.” This had national resonance with the civil rights movement. We were invited by Levi Jones to collaborate on a memorial project of sorts. His creative process involves stitching and sewing various artifacts together, largely decommissioned law books and encyclopedias, to create abstract surfaces on canvas.

We were asked to translate his artworks into an immersive public installation that would mark and acknowledge this history. The proposal is for an enclosed garden and plaza wrapped by a pleated metal screen whose perforations echo the marks typically found on Levi Jones’ canvases. For the Chicago Biennial, we made an exhibition explaining the project through a full-scale mock-up of the proposed enclosure, as well as a short documentary with the design team and stakeholders. The project is now in the fundraising stage, and we are planning for a second iteration of the exhibition to take place at the Grant County Public Library in Marion.

Using 3D software, we created a series of perforated paper studies based on his abstract paintings. This was a really interesting process, and those early studies inspired the idea of scaling up Sams’s work to create a large-scale public art piece that functions as an enclosure for the garden. We love that, in this case, public art serves as the driver for urban design.

DANIEL:

The project has its own sense of temporality because the garden will be something that changes with the seasons and fluctuates over time. Another artist, Sam Van Aken, has agreed to produce a “tree of strange fruit” for the project, which will be a grafted tree of over forty different species of fruits and flowers. Our work almost always carries a fascination with what we are doing in relation to the urban fabric, which is also deeply tied to the social fabric of a place. That is always part of the conversation and our creative process in the studio. What are we doing to the morphology of the city? How are we altering it? Are we introducing a path that weaves in and out of it? Are we creating an enclosed space to repair the void between buildings? That may be one of the reasons why we think that cities are essentially woven. We simply thread needles in different ways throughout our work.

Erin Besler and Ian Besler are co-founders of Besler & Sons, LLC, a studio based in New Jersey that designs buildings, objects, videos, software, and exhibitions. Their work creates new audiences and opportunities for engagement with architecture through participation with amateur creators, construction trades, and design software.

Their design work has been included in international installations and exhibitions including the Shenzhen and Hong Kong BiCity Biennale of Urbanism/Architecture, The Tallinn Architecture Biennial, MODEL Barcelona Festival, and the Venice Biennale. Their work has been supported by organizations including the Headlands Center for the Arts, the Graham Foundation, and a United States Artists Fellowship. Alongside practice, they pursue design research through teaching and writing, with publications in e-flux, Log, Pidgin, Future Anterior, Project, San Rocco, and Perspecta. Their debut book, BestPractices:ACompaniontoArchitectureandIts Messy Relationship with Building Materials, Signage Systems, CommunicationEquipment,PlantLife,andPeoplewas published in 2021.

How did you come together?

ERIN:

Ian has a BS in Journalism from UIUC and was an editor for the Daily Illini. After Ian graduated, we got married, and then, pretty shortly after that, we moved to Los Angeles. I began in the M. Arch program at SCI-Arc, and Ian was in an MFA program at the Art Center College of Design, Pasadena, California. While Ian was still in graduate school, I would visit the studio at Art Center, and the program director used to joke and say, “Oh, Besler and Sons are here.”

We started working on projects together. In 2015, we were invited to submit a proposal for the MoMA PS1 competition, and we needed to carry $2 million in liability insurance. So, we formed an LLC. To register the business, we needed a name. Besler and Sons seemed fitting. It suggested a small family practice or carpentry business. Now we work on a lot of different things, from house renovations and exhibition design to installations, websites, and objects for the home.

We’re always trying to expand the fields that our projects participate in or that participate in our projects. We try to think of ways architectural projects relate to the worlds of graphic design, interaction design, and web design as a way to think about our audience. We usually pass things back and forth or develop different aspects of projects in parallel.

How could you explain the design philosophy of your firm?

What draws your inspiration for your designs?

The field of architecture is exclusive in a lot of ways, and we try to work against that. We’re more interested in ubiquity than exception. A lot of our projects try to expand who architecture serves; one way we do that is by producing platforms for people to contribute to projects. In a sense, they’re participatory and try to build communities.

Could you talk about one project in particular that exudes your philosophy?

We look at everyday aspects of construction and recognize that people have effects on the built environment without professional training but with ingenuity and creativity. We spend a lot of time looking around and documenting, photographing, and redrawing things that seem like impromptu interventions. It’s just as valuable to look at the building next door as it is to look at a Renaissance palazzo. You can find value in a lot of places.

Right now we’re really focused on rural American barns and how the building of a barn has a history in community building. Barns are sites of learning, skill sharing, and exchange that’s built more on mutualism than it is on profit and individuality.

Can you share an example where community engagement played a crucial role in the design process of your work?

We designed this app called “StudFindr,” which was up at the Chicago Architecture Biennial and is still up online, where anybody can go and draw squiggles that turn into a stud wall room. The app is averaging everybody’s contribution together to make a collective design.

More recently, Storage Ensemble was part of a collective project called Privacies Infrastructure, which was hosted by the organization Materials and Applications and curated by Jia Gu and Aurora Tang in LA. For that, we organized a series of weekend workshops where the local community was invited to come and build storage sheds. At the same time, we were sharing tools and how to use them. It was a bit of a performance, a bit educational. One thing we’ve learned in working with large groups of people on projects is you have to be comfortable with giving up control on some level.

And that’s oftentimes very difficult to confront as an architect or designer because you’ve been taught in school that you should have control over the whole project—like it’s yours. You put it up on a wall; you have to talk about it. And this relates in some way to systems built up around the profession that require architects to assume responsibility and control over a set of drawings in order to stamp them and sign them. And so a lot of the things we’re trying to do put pressure on these aspects of education and practice that try to maintain certain realms of control over a project. Of course things need to be safe; buildings need to stand up. But on another level, there are ways to bring more people into the conversation. Giving up some control means being open to that. Our projects do it in different ways.

Can you expand more on the topic of your vision regarding your projects?

Oftentimes, architecture doesn’t consider participants or considers them as occupants or users at the end of the product. We try to bring people into the process at different points. And we try to bring together some of the divided aspects of architectural production, like between the studio and the construction site. We can let more people into the conversation, not just in a service-oriented setting. These are our clients, and we’re doing work for them. But what would it really mean to work with them? To think about architects as an interface between clients and their programs.

We have a few websites, one being beslerandsons.com, which is the closest that we get to an office website. We also have besleranddaughter.com, where we test ideas about web design. erinbesler. com is an interactive website that allows people to re-visualize the work in different ways by changing colors, fonts, and emojis. We think of our websites as projects.

Does your website support your philosophy that architecture is interactive? Is this why you have many exhibitions?

2020

What was your favorite project?

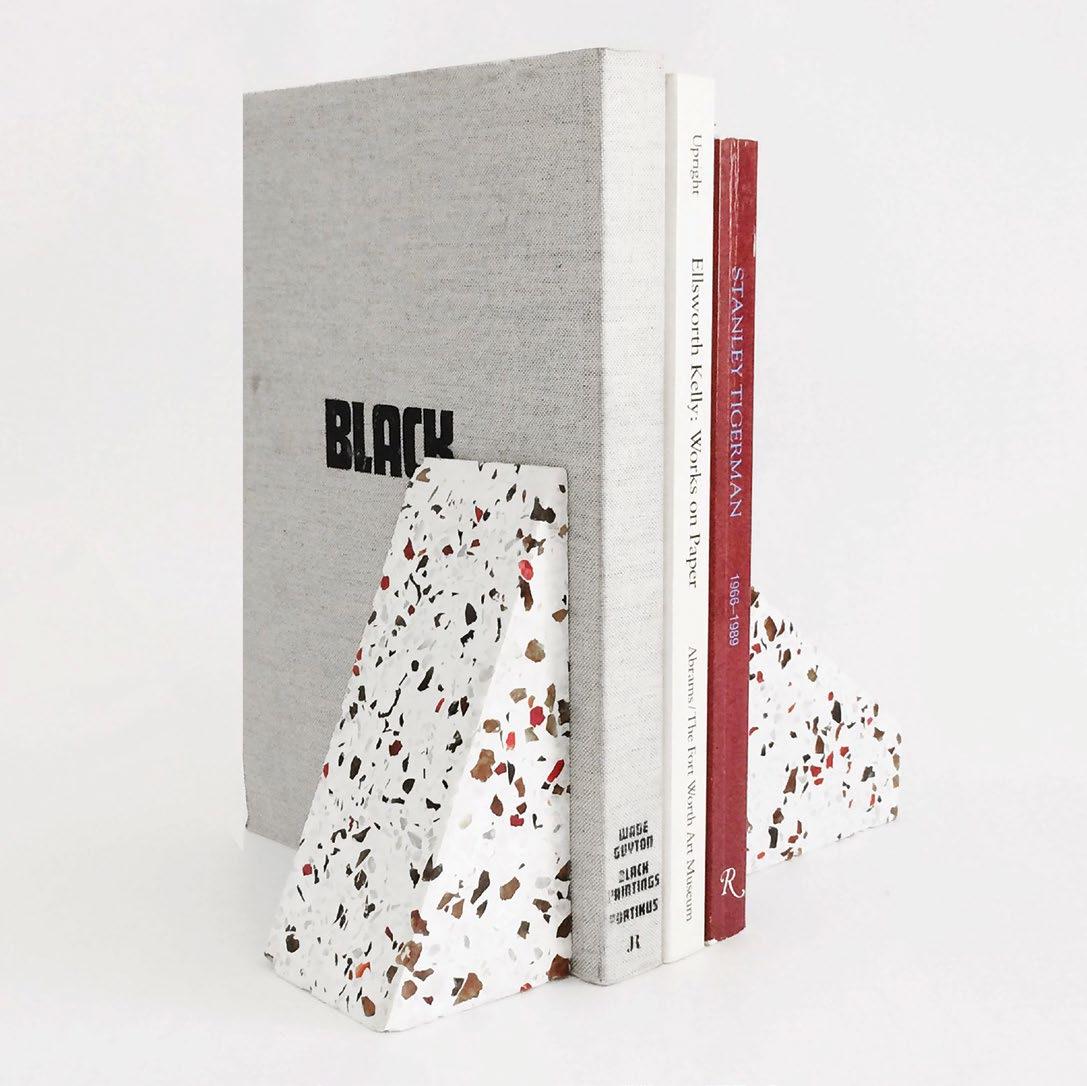

I would say I like all of them, but there was a moment in time when I hated everything. You know, you get done with a project and you don’t want to touch it ever again. You can’t even look at it to put it in your portfolio or something, because you just need to get through it. But now, every project is different; there’s a different set of people you’re working with. There’s a different set of constraints. There’s a different dynamic with the people you’re working with in the office and people you’re working with outside the office. We have this series of Terrazzo (https://www.beslerandsons.com/ projects/props/) objects that started as a self-motivated project. Then they started to show up in museum stores. We paused on that for a bit, and then we were making t-shirts, like house wrap t-shirts, like Tyvek. That was fun and interesting. There are aspects of this in every project we do because we try to expand or multiply the number of things we’re designing in each project. Like if somebody asks us to do a house renovation, we’re also trying to figure out ways to make some kind of pop-up book for it.

That’s a tough question because a lot of what we do is probably against some idea of innovation, just because this idea of progress is so often motivated by a capitalist value system. We take time; we try to slow down and look back. We tend to think about small details or even ways to resolve things through a model. We make a lot of models that are trying to be buildings. So most of what we’re trying to insert into projects is a sense of joy, not so much innovation.

Can you provide an example of a specific project where your team had to innovate or adapt to meet unique challenges?

What trends do you see emerging in architecture?

And how is your firm positioning itself to stay ahead or behind?

I look to students. It seems like they are more interested in forms of collectivity and collaboration. There are a lot more practices coming out of school started by three or four students, not just the kind of single-person offshoot of another practice. Now there is more emphasis on ways to recognize the collective effort and the various levels of contribution that architecture requires. Not just the designer, but the people at the construction site, the people at the quarry, taking stuff out of the ground, and understanding what that means.

Architecture is entwined with very large questions that relate to the environment. It’s not just what material to use, but what the implications of its use are and what people and communities are affected by its production and processing. I hope there’s more attention to those things and more attention to ways that architecture can acknowledge its attachment to those things as opposed to the detachment that it has relied on for a long time.

There’s a push toward recognizing that multiple people are involved in projects, and that’s a good thing. So, more students are collaborating on projects such as their theses at Princeton. That means they’re looking for those forms of collaboration when they come out of school. And collaboration happens on a number of levels, not just as it relates to design but also as it relates to the production of a building. Many people making contributions to a project aren’t acknowledged or even considered. I think collaboration and an idea of community aren’t just about the community that the building’s being built in, but the site of the building as the aggregator of multiple levels of collectivity and community that surround a project that comes before and after construction.

We try to prioritize what is considered by many to be ubiquitous. Like, what can you do with the stuff that’s available to a lot of people? How can we begin to think about these materials not just for new and interesting forms or projects, but also how they’re linked up to material history, sites of extraction, and other things as well? I would say a priority in all of our projects right now is thinking about the interconnected nature of architecture, and you could generalize that by calling it a community project.

Are there social or cultural aspects that your firm prioritizes in its design?

Going back to the StudFinder, do you see a future in AI? What could be your vision for a harder development of your project?

How do you see yourselves engaging with the trend of translation in architecture?

AI is interesting. For a while, we were thinking about a VR for StudFindr because the project proposes that anybody can come and squiggle to contribute. There was also another aspect of it where you could print a plan of your own. And so it seemed like VR would be an interesting kind of overlay to that, bringing an instructional and visualized aspect to the project to allow anyone to build a room of their own.

I think it runs through all our work in different ways. The work we’re doing now is very much focused on forms of communication. The really interesting question becomes: what forms of communication are required to translate something?

It would be great if architects thought more about what maintenance is, or what does it mean to continue updating something, reconstituting something, or building something not so it stays the same way forever, but so there’s some capacity for change or translation, or moving it from one system into another? And what has to happen to move it? What are the mechanisms that allow that to happen? Is it material? Structural? Representational? Is it bureaucratic?

“ONE THING WE’VE LEARNED IN WORKING WITH LARGE GROUPS OF PEOPLE ON PROJECTS IS YOU HAVE TO BE COMFORTABLE WITH GIVING UP CONTROL ON SOME LEVEL.”

- Erin Besler

It would require a lot of new systems of valuation built around risk management and certification. The beam you take out of a building isn’t going to perform the same way somewhere else. What histories are tied to it? Are we recording its material life? Because we haven’t cared about that up to now. But circularity requires the tracking of material life. Frequently, it starts at the building that it came from. But in the circular economy, it proposes that industry is involved, and industry takes back some stuff and re-constitutes it into something else, like carpet. Manufacturers take back their carpet before it reaches the end of its life span, and because they made it, they know how to recirculate it. So, building components start to be redistributed in different ways, and there are whole economies behind that allow for mobility.

I’ve been interested in what happens when we move from one software system to another. And this was part of the origin of the StudFindr project. What happens when you move from Rhino to BIM? Rhino to Revit? One is an information model. When you move from one system to another, some things are gained and lost. I think looking at those things is perhaps the most interesting. We’re trying to not lose anything in translation, but that requires a whole lot of control. What would happen if we just said, “It’s okay if it’s a little different” or something?

Regarding the circularity of materials, do you think these questions have already been answered?

Kate McLean is a practicing designer, cartographer, lecturer, researcher. Regarded as a world expert on smellwalking and on smellscape mapping, she has spent the past 14 years working to understand how humans make sense of their worlds through their noses. She has researched and generated over 30 major public, global smellscape mapping projects in France, Netherlands, Singapore, Switzerland, Ukraine, UK, USA with further work in planning for India. In the process, she has led 170 organized smellwalks with over 2000 people together with smell-related workshops in Norway, Sweden, Morocco, Estonia and Germany. Her smellmap installations have been exhibited in over 20 national galleries and museums worldwide including the Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum New York, MAIF gallery Paris and the National Library of Scotland. Her work has been featured in worldwide media including in New York Times, Guardian, Time Out, WIRED, Sky, BBC, Slate, Atlas Obscura, New Scientist, Telegraph, Washington Post, and ABC News.

As an academic, she has published extensively, including co-editing Designing with Smell: Practices, Techniques and Challenges published by Routledge in 2017. She presents at conferences and regularly advises olfactory research groups. She also consults for olfactory- related industries and is working on an illustrated book on smell.

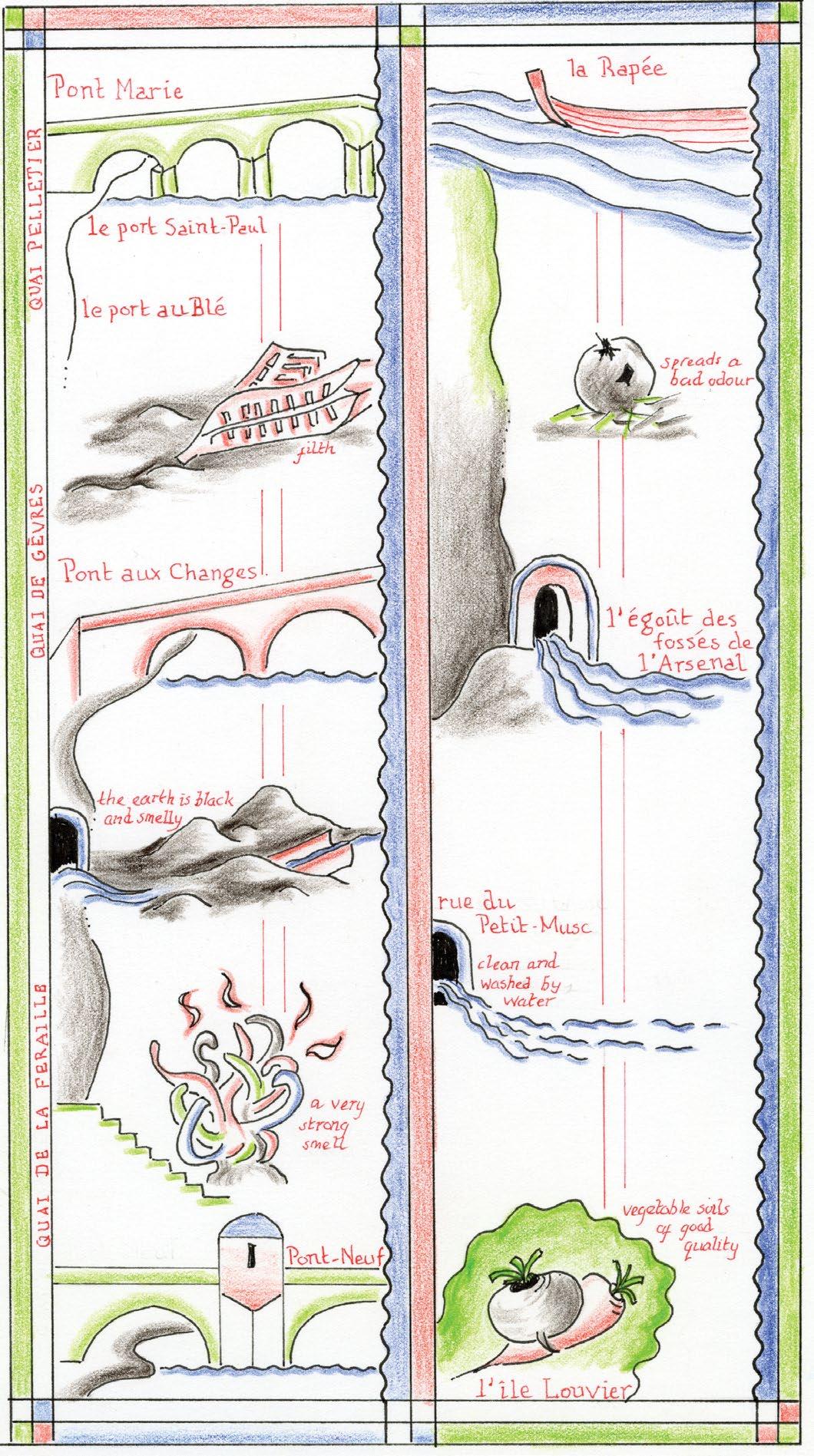

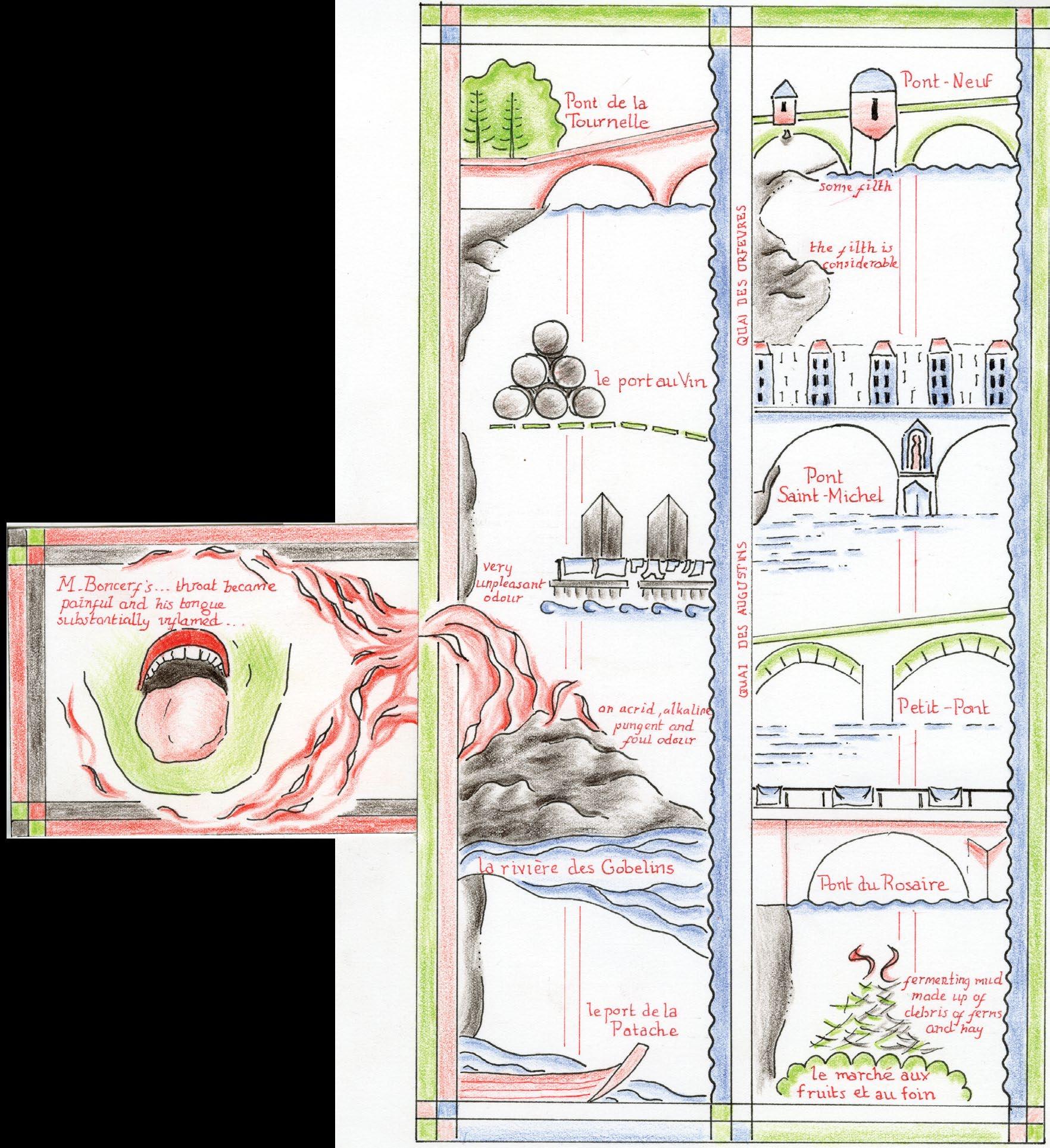

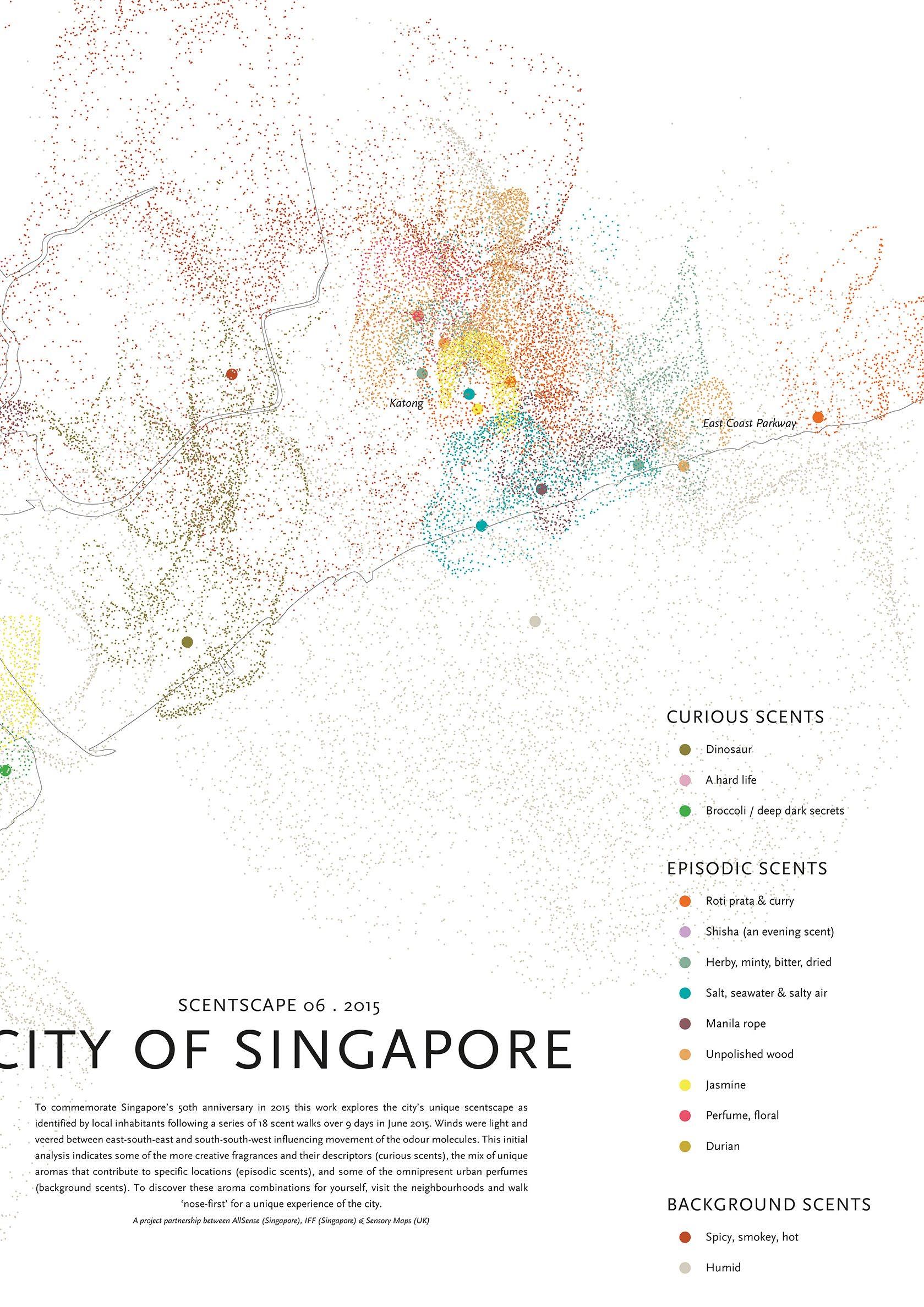

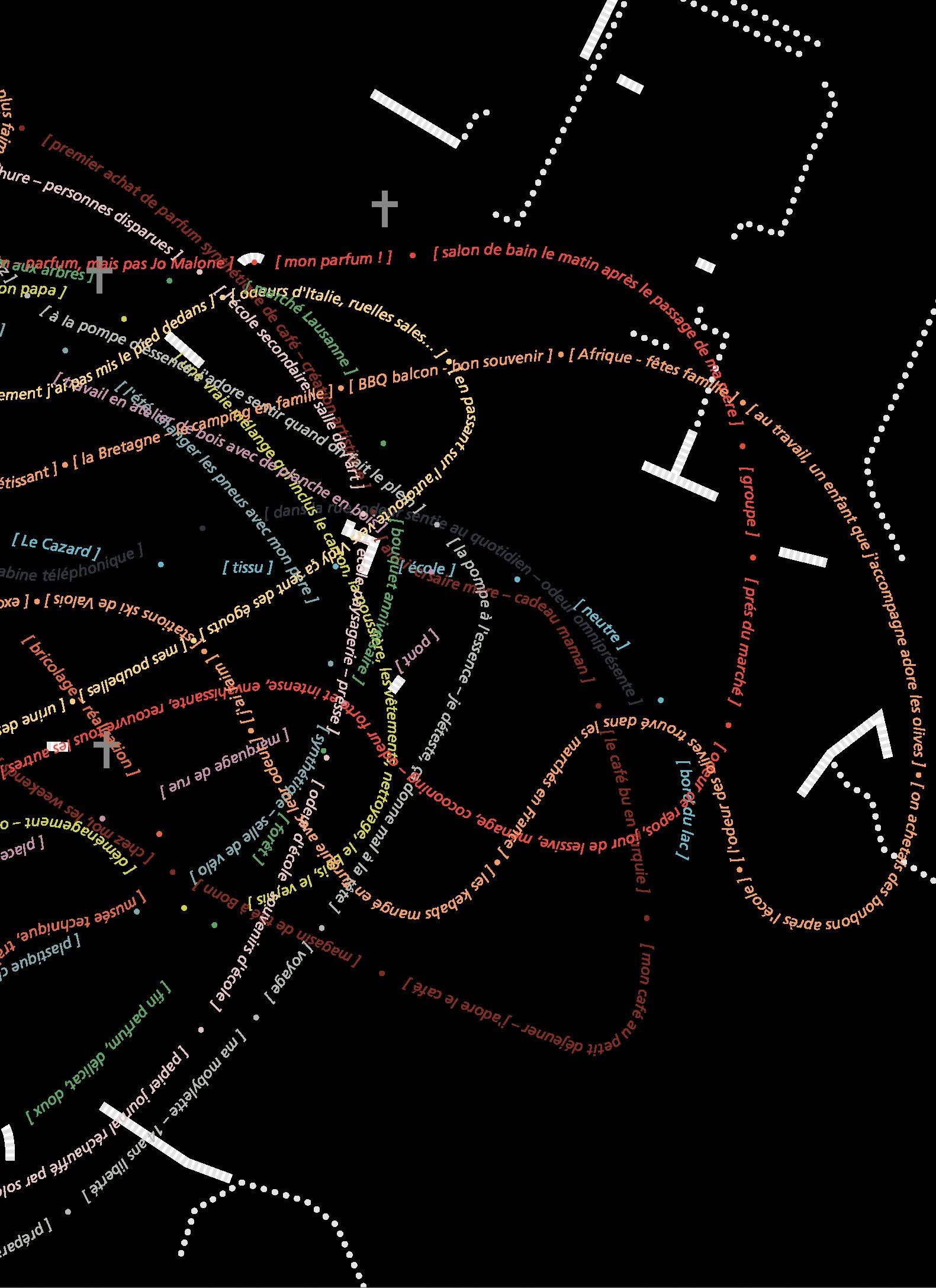

What exactly is a smellscape and how does this play into what makes up a sensory map?

A smellscape is easiest explained as the olfactory equivalent of a landscape. So, where with our eyes, we might see a vista laid out before us, and we might clock different aspects of that. A smellscape is what we might detect through our noses in an area at any given moment in time. It was a term that was first used by human geographers in the mid-1980s. They were just posing questions about what a soundscape is. What is a smellscape? How might these things actually play into our understanding of the world around us? It became much more research in the mid to late 2000s.

From 2010 onwards, there was a lot more work that was starting to happen in that field. I came into it with a project that was essentially looking at engaging the sensory back into graphic design. I was aware at the time that there was a lot of skeuomorphic representation of the real world, and I asked myself a question about how we could actually re-engage the senses into design. It turned out the project moved in the opposite direction, and it became largely about smells, but all the other senses as well, and how each one of them contributed to our understanding of a sense of place. I wanted to encourage people to actually go outside and visit places and use their senses in a way that I was starting to think was just disappearing with the digital age.

So, I had a particular focus on the city of Edinburgh in Scotland, and I was looking to say, ‘What are the tactile descriptors of Edinburgh and how might that play out as a map.’ Then, I was looking at the tastes of Edinburgh and trying to synthesize and summarize how peculiar and specific they were. And then smell came into that equation as well. It’s almost as if I use that idea of graphic design and visual representation to say if I can make this look curious, interesting, and slightly difficult to understand; those elements would actually prompt people to say: “How can this work? How can you show smells on a map?” You can’t show smells on a map. I wanted that argument, and I wanted people to engage with that argument, particularly with smell. How can you show what’s there? Surely, it’s not always there – absolutely, you’re right. That smell that was detected in 2010 may not be there today.

The Sensory Maps is a project that looks at the different senses; it separates them out to an extent but always relies on being able to see the maps or touch the maps as well, so there’s always a multi-sensory aspect to it. The smellscape ones were actually the most difficult to do, so they became the most interesting, and that’s what I’ve followed on through for many years, over about 12-13 years now. It’s looking at the smellscapes of different cities in different places around the world.

What made you interested in exploring this concept of sensory maps?

It really was the idea about how we look at codifying maps to try and understand places that we’ve been. We look at maps to try to understand places that we would like to go to. We imagine ourselves in different worlds through maps. Maps in literature enable us to explore created worlds and mythical worlds.

It’s almost as if I use that idea of graphic design and visual representation to say if I can make this look curious, interesting, and slightly difficult to understand; those elements would actually prompt people to say: “How can this work? How can you show smells on a map? You can’t show smells on a map.” I wanted that argument, and I wanted people to engage with that argument, particularly with smell. How can you show what’s there? Surely, it’s not always there. That smell that was detected in 2010 may not be there today.

That became another part of the project, but it was to engage, capture that interest, and really challenge the way that people engaged with the world through their senses.

The volunteers are amazing because the small project uses the noses of people who are local to a city or a town. There are different ways that different researchers approach them and some go through their own noses and some go through the noses of other people. This project is grounded in the idea that it’s a local population who best knows their smellscape. They own it. They have the reference to be able to say that the smell is of durian, for example, which is not something that, as an outsider to Singapore, I would have known. I would have said it smells different, but it wasn’t something that was in my repertoire.

So, it is essential to the project that local noses are used. Therefore, I work with local groups to get those volunteers, ask them to come on any number of walks, and list down what they smell. And then it’s quite often through the conversations that you have that different elements start to get revealed. People write really interesting things when it comes to smells. And sometimes it’s short descriptions; sometimes, they’re identifying what an element is.

I’ll go back to the Singapore map as an example. It could be something spicy, it could be something herbal, it could be a rope, it could be the sea. Those are all ideas, elements, and aspects of the world around us that we can relate to. We can start to imagine what that’s like regarding smell, but then you get the more interesting ones. You get things like a hard life, and it’s through conversation that I understood what the person was trying to allude to. They said, “Well, we’re in a building at the moment, and this building is at the cheap end of a very expensive street. Smells of cheap massage oil, and the massages are taking place in the basement downstairs, but it also smells like the off-gassing from the plastic pens being sold in this shop. And then when you just stand here, you can smell the cigarette smoke that’s lingering inside the elevator.”

They said all of these elements come together to say that it smells like a hard life in comparison to the other shops down the street. Those are the types of things that I learn about places. Those are the elements that I try to combine with the more traditional and more sort of like standard smells that you might expect in order to generate an idea of a smellscape that has interpretation placed on it, as well as the very fundamental sources of some of the smells.

With these volunteers and with research you’ve done in different cities, different countries, what have you discovered in terms of the relationship between times and smells in a particular space?

What do you think is the most important impact of this type of research?

There are a couple of important impacts. One is it can record change in a way for a sense that hasn’t got a way of being recorded. We can take air profiles and samples, but smellscape mapping enables us to capture moments in time. I describe the works as impressionist paintings. So, they will only capture a specific moment in time, and you could go back the next day and find something completely different. The smellscape is actually really important; it’s a way of visually capturing what some people will write about, like the smells of breweries in the UK, which were huge and dominated many city smellscapes. In recent years, they have become much smaller. Microbreweries have been set up so they don’t emit the same sort of clouds of smell of fermenting beer that once enveloped the city. So, it becomes a way of recording the city’s smellscape. That’s one of the important impacts of the project.

The second is to point out and engage architects, planners, and designers in the importance of smell when it comes to deciding what our cities are going to be like in the future. It has the potential to be a projective research method. It enables people to interact with the population on a very easy and very immediate level. To be able to say, well, you don’t normally think about your nose and what things smell like, but you would tell us if you don’t like it. What happens if you do a smell walk here? You decide what’s important, you decide what you actually value in a place, and then you start to design and create urban landscapes around the other senses as well as the visual.

“YOU DECIDE WHAT’S IMPORTANT, YOU DECIDE WHAT YOU ACTUALLY VALUE IN A PLACE, AND THEN YOU START TO DESIGN AND CREATE URBAN

AROUND THE OTHER SENSES AS WELL AS THE VISUAL.”

- Kate McLean

There’s an interesting one that I’m working on at the moment, which is in a town close to where I live. It’s a town where there used to be a Royal Navy town, and a lot of shipbuilding happened. Then, the shipbuilding stopped, and it became quite economically deprived. It hasn’t particularly picked up for 30 or 40 years.

With it comes issues of pollution, and there’s a lot of car traffic. So, the town itself has various roads that were once used by workers in the docks but are now used by cars to shortcut through different parts of the city. So, I did a project recently, which was to walk with people from there. At the same time, as we were walking, we were actually measuring the air pollution. So, we had air pollution sensors going alongside the noses.

What I’m in the process of doing at the moment is correlating the data from the devices with what people smelled. I’m starting to look to see how much you actually need to record that data from official sensors compared to how good humans are at detecting what’s there, what their interpretation is, and their responses to that. So, in a way, it’s calling out that street as being possibly a marker in the future as to how smell can actually indicate sources of pollution, but also activate and galvanize local community groups to influence local government about what they can potentially do about it. What measures can the people who live there put in place to make it safer for them?

If there’s one thing that I’ve learned from the Sensory Maps project, it is that I was trying to give a voice to smell or a visual voice to smell.

Have you had any current projects or possibly any work that’s working towards making this possible and that are dealing with this?

What is a new aspect of smell that you discovered through this project and how did you expand on this discovery?

What started as being something that I thought would be just fun has ended up having a lot more longevity to it. There’s an element of it that is about memories. Out of all the senses, the smell can be transported to another time and place really quickly.

So, in your lifetime, how do you start to measure how long ago a smell memory was? Suppose you’ve got people of different ages walking. In that case, you can’t say it’s a smell from 10 years ago, so you try to find other categories. So, we ended up doing a lot of work trying to find different types of explanations for smell memory. There’s the immediate past, and then you’ve got childhood because there are a lot of small memories that are created in childhood. Then we had another interim one, which was anywhere between childhood and yesterday as a category. Those then became beautiful descriptions of the smellscape again, but in a slightly different visual form with a gradient on it to know how deep those smell memories were in reflecting what was like around the world. It’s got the memory side of it and it’s got the visual aesthetic side of it. It inevitably has an element of tourism and curiosity about it. It also has this community engagement element. A simple Smell Map can become quite wide-ranging in its capacities.

With such an allencompassing project, even if it’s just focusing on smell, how do you translate all of these different elements and aspects of smellscapes into something cohesive?

It’s scary because it started off as being a simple exploration. Suddenly, you start to see how it can be applied. It can be used in healthcare, and it can be applied to wellbeing. We’ve got a book proposal that is going to go out to publishers in the new year. That will look at these different aspects of the smellscape mapping project, and it will have examples from other places and spaces that start to join it all up.

I’ve always been really interested in meteorology and maps. One thing that those two disciplines share is the idea of the isoline, which is those contour lines that go around, and the closer they are together, the more intense whatever is happening. So, in meteorology, those isolines come together to indicate that this is where winds will be extreme. In geography, it means a very steep slope. I was thinking about what smells were like in terms of the fact that they seem to cross over themselves and each other. I wanted to show one smell on top of another one and where that combination might happen because many of the smells that we detect are not single instances. They are complex.

Now, how do we depict that? You can’t take every single smell and say, ‘Okay, here’s this combination, here’s this one, here’s this one.’ So, I was looking for a way of separating them and indicating that at any particular place, you might get this transect of a number of smells coming through. And the contour lines, those isolines really did it in terms of that.

I’ve always been really keen to move smells into a register that actually enabled us to engage with them in slightly different ways. So, the color schemes on each of the maps reflect the town where the maps are created. It pulls from the local landscape, the local architecture, and the local environment. It also draws from sources of some of the smells, so that’s why I like to visit the places where the smell maps are.

Then I do the data analysis on it, and here’s a common smell; here’s one that’s recognized by a lot of people. What color is it? Where is its source? Where does it come from? How might we relate to that as a color? So, the color comes from the landscape. The symbols come from a desire to communicate the movement of the smells, along with the fact that they started from a central point and very much had a size to them. They spread over a geographic area, but then the wind moved them, and you are still determining where they’re going to end up.

The smell is the underrepresented sense, and it’s quite nice to be able to say then say: well, we’re all ordinary human beings. We all have this capacity to identify smells. We don’t often think about what else we can give a voice to? How can we actually be active in our local areas?

How did you come up with the design of those sensory maps?

Gaetano Trovato is a celebrated Italian chef renowned for his masterful interpretation of Tuscan cuisine. Born and raised in Sicily, Trovato developed an early passion for cooking, inspired by the rich culinary heritage of his homeland. He honed his skills under the guidance of esteemed chefs in Europe. In 1982, Trovato opened Arnolfo Ristorante in Colle di Val d’Elsa, Tuscany, a region famous for its traditions and breathtaking landscapes. The restaurant quickly became a beacon of Italian fine dining, earning two Michelin stars under Trovato’s leadership. In the year of Arnolfo’s 40th anniversary, the restaurant moves to a new location, a modern structure designed and built by the Trovato brothers, Gaetano and Giovanni, while keeping open the historical mansion located in the center of Colle di Val d’Elsa, with its 4 iconic rooms facing the Tuscan hills. Beyond the kitchen, Trovato has authored cookbooks and participated in culinary events worldwide, sharing his philosophy of connecting people through food.

Alice Trovato is the daughter of renowned chef Gaetano Trovato and a devoted member of Arnolfo. Growing up in the vibrant atmosphere of culinary arts, Alice developed a deep appreciation for her father’s work and dedication to upholding a family legacy.

Could you please introduce Arnolfo?

ALICE:

Arnolfo Ristorante was founded in 1982 by Gaetano Trovato. In the beginning, it was just him. He was around 22 years old, and after gaining some experience abroad, he returned and wanted to give it a shot. The restaurant was named Arnolfo, after Arnolfo di Cambio, a historic architect of Florence, reflecting the chef’s passion for architecture. He is an aesthete and often says, “If I had not been a chef, I would have been an architect because it is just a crazy passion.” He appreciates the details and studies them meticulously.

In 1994, he decided to undertake his first restaurant project in a historical location. He took a 16th-century building that was completely in ruins and slowly restored it year by year. This has become a family tradition: every year, we fix a little something. First, there was a general renovation, followed by a meticulous focus on every detail. The restoration began in 1992, and in 1994, we moved to the historic site. The restaurant received its first Michelin star in 1996 and its second star in 1997.

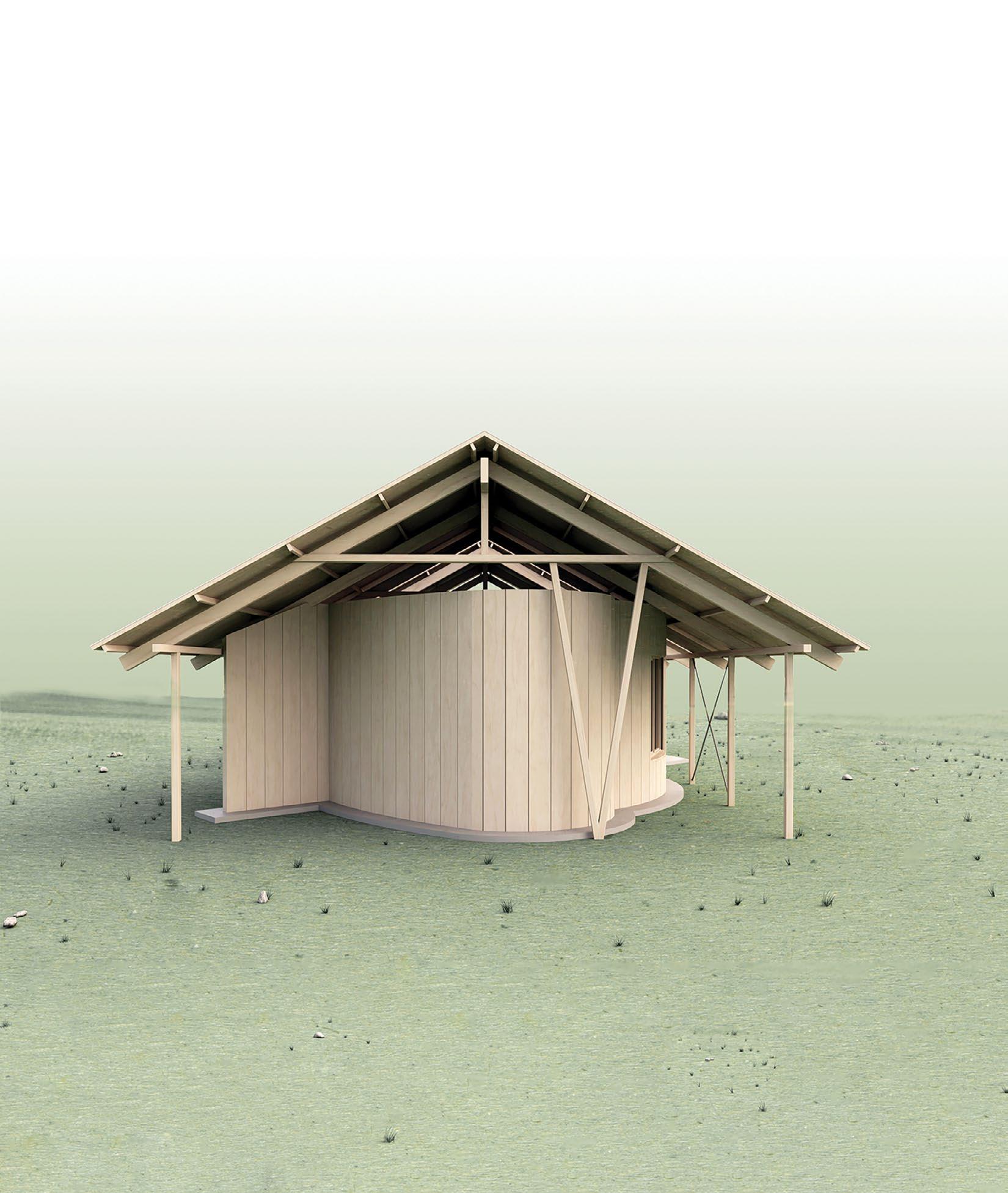

As early as 2010, the dream for a new restaurant began to take shape. This project had been a long-held dream of my dad (Gaetano) since he was a child. He envisioned creating a restaurant from the ground up because, typically, restaurants and kitchens are repurposed from existing structures, which often come with wonders on one side but also compromises on the other.

For the new location, he initially sought land in the area but was open to moving further afield as well. He explored options around Florence and San Gimignano. However, he always returned to Colle Val d’Elsa, a town where he had invested and cared for many years. While we are Sicilian by origin, we are Tuscan by adoption. He found wonderful opportunities in Florence, but something inside him told him to stay in Colle.

My dad believes that the best investment in land is having a great view, whether from a house or a workplace; it always needs to have an amazing view. He thinks that location is fundamental. It took him ten years to find the right spot for the historical restaurant, as the process did not unfold as he had hoped.

Initially, we worked with an architect from Colle Val d’Elsa, but it was not a good fit. My dad would often say that his drawings looked like a car dealership. The first project was quite poor, so he ended that relationship and called in Milani Studio. Finally, we found the land and also the right project because my dad drew the initial design. The architect then structured it and made it professional. Here, however, the design concept originated with him, so the spaces were thoughtfully planned specifically for the operation. He said, “In my 40 years of doing this job, I know what this, this, and this is for. Now, I’m going to make a restaurant the way I want it.”

It is important to note that out of the 1,000 square meters of the restaurant, only one room is designated for customers; the rest is for staff. This emphasizes how important the working environment and work sustainability are to him. There are large spaces and various kitchen placements, including a cold kitchen, a prep kitchen, and a service kitchen. The kitchens were designed by him, combined with the expertise of engineers from the Polytechnic University of Milan. He really created a kitchen that he envisioned. There are no buttons or pins, so it takes only 20 minutes to clean. Typically, in kitchens, cleaning, scrubbing, and sanitizing take at least an hour before going home after a shift.

The payoff of this project is to inspire young people to fall in love with this work. The goal is strong and clear: there is a way to work, an opportunity to organize the workflow and the spaces, and the staff experience is fantastic. This organization also allows for the reduction of the extra hours that can sometimes extend the workday.

What is the concept of Arnolfo from an architectural perspective?

The concept at the architectural level is that the chef wanted to create a restaurant that reflects his cuisine. Its exterior is modern, creating a detachment from the well-preserved Tuscan architecture. However, we also need little changes every now and then— some movement, right? Some novelty. From the outside, you see it’s a new, modern restaurant, but when you come inside, you encounter all the materials that originate from no further than Volterra, a nearby town.

For example, when you try a modern dish with a nice dynamic aesthetic, you also taste the territory. That’s kind of the idea. The chef envisioned the restaurant this way, and this is the first part of it. The raw materials are sourced from the neighboring territory, and we have 90% Italian products, mostly from Tuscany.

Another key concept in the kitchen and the thinking behind this restaurant is transparency—because you see everything; there is a clear line, and nothing is hidden. Total transparency. In his kitchen, the chef focuses on three ingredients, allowing you to taste the raw flavors. He often says, “I don’t have to cover you with other ingredients. I don’t need to cover a piece of fish with sauce. You have to taste the fish; you have to appreciate all the ingredients to enhance the experience. Therefore, total transparency.”

What were the main differences between the old location and the new location?

One of the biggest surprises I had was the excitement of coming to the new place, but there was also some fear. It was all new, and we didn’t know what to expect. From the common fire stove to the induction stove, there were a lot of changes. We understood many things later, as time went on. They obviously knew what they were designing; they had a clear vision of the spaces and the movements, and we didn’t even realize how easy it was to work there. I told my father and uncle, “The comfort you gave us is the greatest wealth of this place. It is unbelievable.”

Specifically, we came in August, in the middle of the season. From Monday, we were in the old restaurant, and by Thursday, we had moved to the new place. The effort that our great employees put into it—mamma mia, it was crazy! However, it was truly wonderful; we realized that. Whenever we got to work, it felt like we had been there before. I was amazed and thought, “Wow! When can architecture be both wonderful and functional?” Most of the time, we see beauty in architecture, but sometimes it feels almost detached from function. Instead, it’s critical when the two coincide, because architecture has to be both usable and beautiful. There is room for everything beautiful; however, here, you also have to be careful about function. I must say that, in this case, we have succeeded.

No, it’s definitely influenced by the comfortable environment and the view. Let’s remember that kitchens are usually underground and dark. Here, where they work, is in the historic center, and they have windows everywhere. This, in my opinion, is very important because comfort is key. Arnolfo Ristorante believes in sharing knowledge as a key to success. Unfortunately, in the culinary world—and certainly in many other fields—there is often a lot of jealousy and a desire to keep knowledge to oneself, a bit of greed, where people might say, “Oh wait, I created these recipes over 20 years; now you do it yourself.” Here, I have never encountered this problem. Gaetano, the chef, always tells you, “What I know, I must share, because if I don’t share it, it will be lost.” We are especially lucky to share our traditions. Italy is a country founded on food, so if we don’t carry on our traditions and the ways our grandmothers used to cook, and if I feel jealous and keep it to myself, the next generation will lose both tradition and culture. I believe this act of sharing has been fundamental to the success of the chefs.

There is no hierarchy; while that is fundamental in a group context, at a table, we all sit at the same height. The menu is created together, and the ideas are approved collectively; the chef does not dictate. This approach gives everyone the opportunity to express themselves, which is why we don’t focus solely on having phenomenal workers. We care about having kind, respectful, intelligent people who are willing to challenge themselves so we can grow together. In my opinion, the human aspect is the most important factor that has allowed my dad to educate many young people and help them on their paths in the culinary world.

How did the restaurant produce so many Michelin-starred chefs, is it due to your father’s working method or does architecture play a part as well?

“MOST OF THE TIME, WE SEE BEAUTY IN ARCHITECTURE, BUT SOMETIMES IT FEELS ALMOST DETACHED FROM FUNCTION. INSTEAD, IT’S CRITICAL WHEN THE TWO COINCIDE, BECAUSE ARCHITECTURE HAS TO BE BOTH USABLE AND BEAUTIFUL.”

- Gaetano Trovato

Personally, I love the lines in this restaurant. If you look from a small square just below the restaurant, you will see lines that extend in many directions, and I find that amazing. This area is one where no one ever passes through; however, in my opinion, the view is very beautiful, especially when combined with the elements of Siena yellow marble, which was my dad’s choice. In the evening, it becomes breathtaking and captivates you before you even step into the restaurant. I also really like the bookstore when you enter. This structure is beautiful and was crafted by a local carpenter. In my opinion, it is quite nice, and the material is interesting.

If I may share from my limited experience in this field, the professionalism of architecture lies in the ability to combine beauty and aesthetics with functionality. It’s important to ask the person in charge, “What do you need? What do you want?” In this case, I had my dad and my uncle, who had very clear ideas in their heads. However, it’s crucial to understand that the needs are not only aesthetic but also functional. For example, the wine racks have specific spacing and are tilted at an angle that allows the bubbles (in sparkling wines) to settle at the neck. Each rack holds six bottles, which constitutes a case of wine, and you can easily see the vintages. The bottles are organized from bottom to top by vintage, which means you don’t have to be a sommelier to retrieve them; even a waiter could find the right bottle, as it is organized in a clear system. I truly believe the key is to understand what the needs are. You might come in and say, “Wow, the wine rack looks beautiful.” But it’s not just beautiful; it’s also functional, and that is crucial for us.

What are some architectural features or design elements that are important in the restaurant?

I always say this restaurant is like my dad. If my dad were a structure, it would be this. It reflects the transparency I mentioned earlier—it’s about reaching a certain point in one’s career where you no longer need to prove yourself. You arrive at a stage where you simply are. My dad has reached that point; he can confidently say, “This is my home, this is my project, and this is what I want to give to the world.” His extensive research into terroir, the choice of raw materials, and transparency clearly reflects his ambition. That’s why I believe this restaurant truly represents him; it embodies the fruit of 40 to 45 years of working in kitchens, including experience abroad.

How does the contemporary design at the restaurant reflect its 40 years of history?

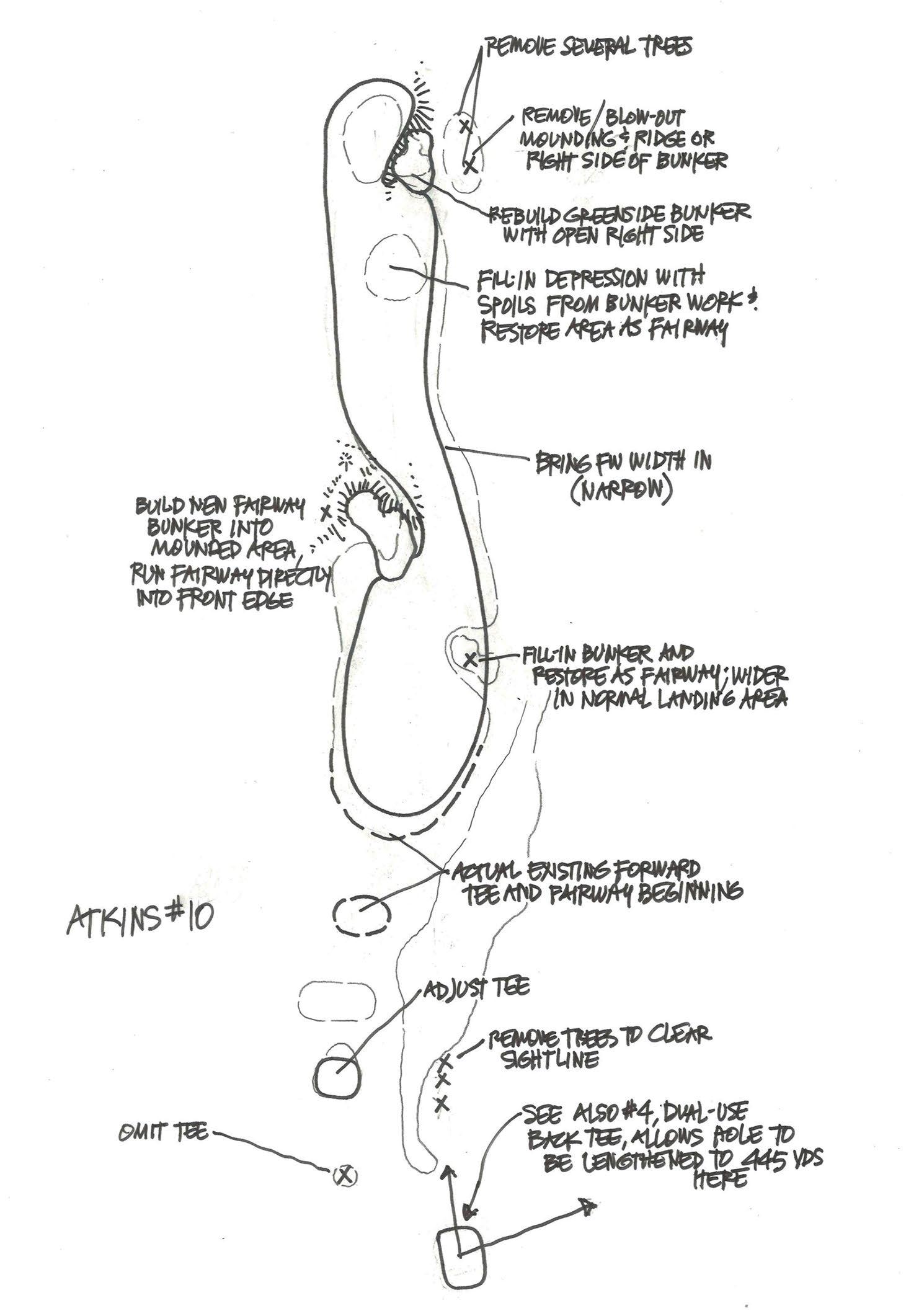

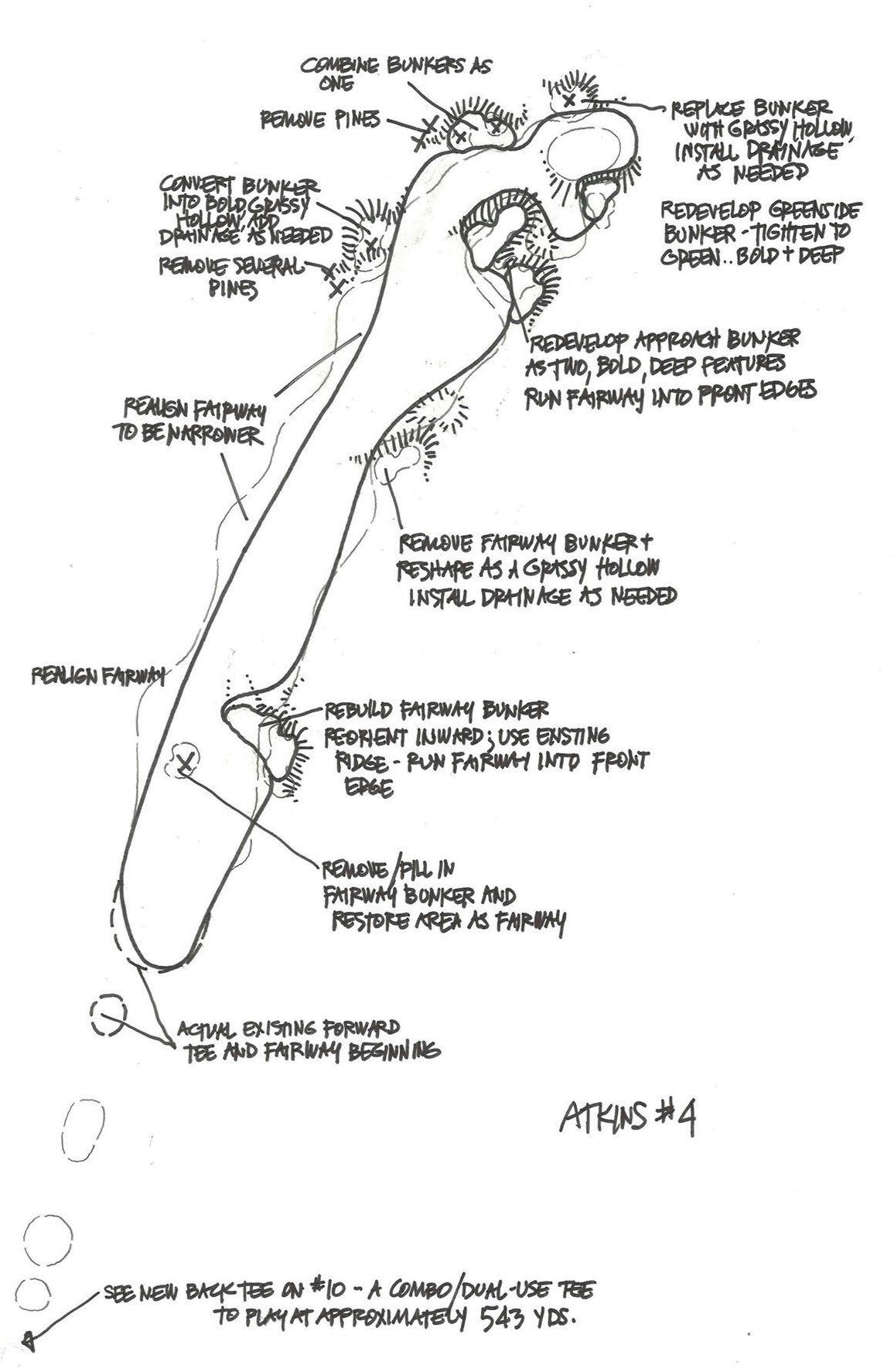

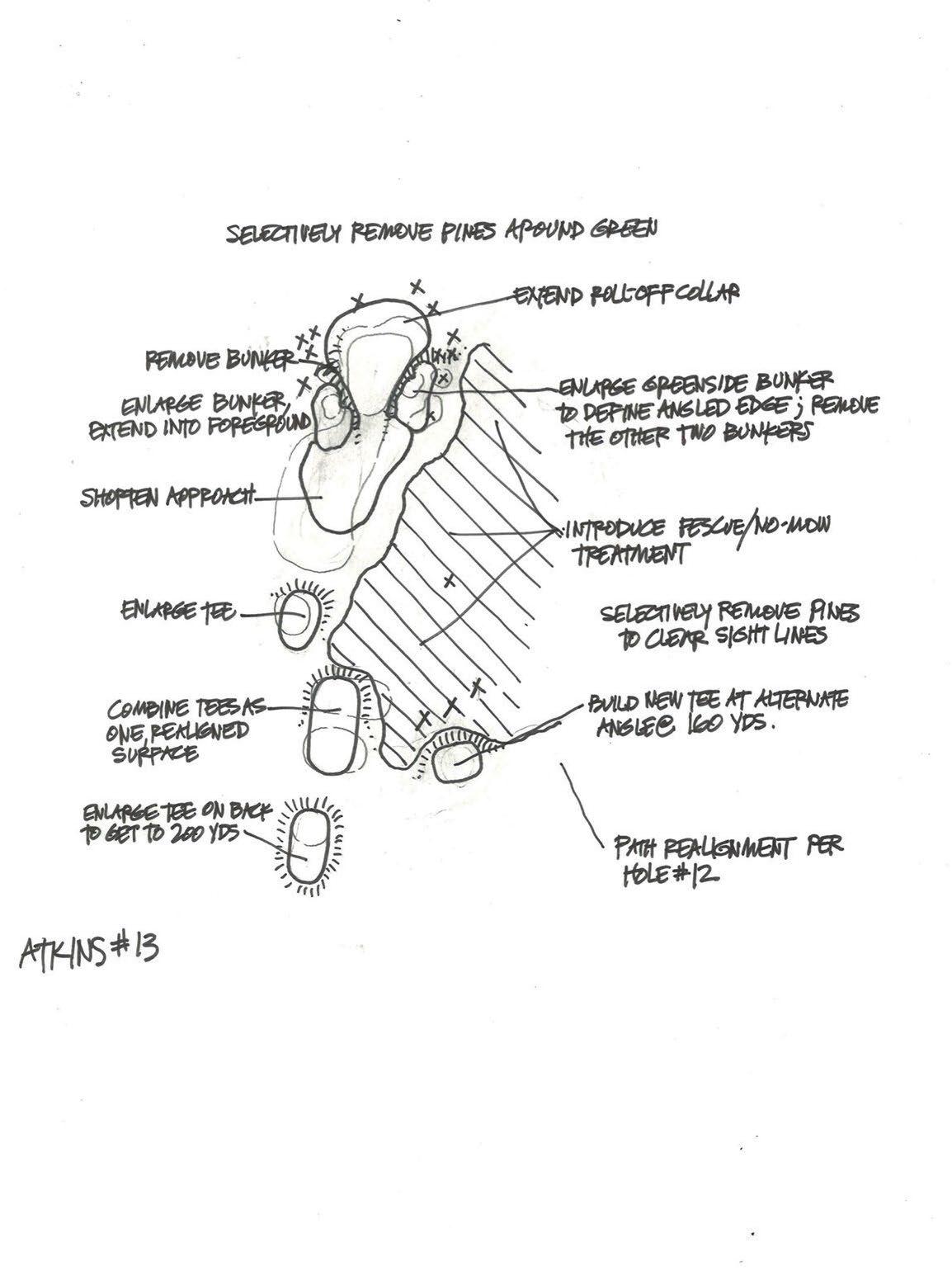

J. Drew Rogers studied landscape architecture at the University of Kentucky, earning his degree in 1991, and at the same time was getting practical experience working on maintenance crew on a golf course. After college, he acquired a design position with golf course architect Arthur Hills, who he would work with for 19 years before starting his own practice in 2010. Additionally, he gained membership in the American Society of Golf Course Architects, ASGCA, in 2001 furthering his credentials. The course is host to an annual collegiate tournament, the Fighting Illini Spring Collegiate, and provides a challenging experience to golfers of all skill levels. This was the main mission of Rogers’s in the renovation: to create a challenging track for the high-caliber college golfer while still maintaining a high-quality course for the everyday golfer to enjoy.

What were the steps you took to reach where you are today?

I always wanted to do what I’m doing right now. It’s highly unlikely that ever happens, but even more unlikely was the fact that I actually got to do it. There’s only about 200 of us in the United States. You got to be really driven, really focused, and pretty lucky too. Things have got to go your way. I was just fortunate.

I graduated out of college, and in less than a year I had landed this job, actually working for another firm at the time, Arthur Hills. It was a dream, and every other week I’ll get somebody sending me an email or reaching out to me in some way, saying, “How do I get involved in this profession?” And even though it’s unlikely, I never turn anyone away because I always think you might be the one. You might be the person that’s going to make it happen.

I studied landscape architecture at the University of Kentucky, and at the same time I was getting practical experience working on a maintenance crew on a golf course. I was getting a lot of hands-on, and at the same time I was getting more of the professional training. Although everything that you do in your major in pursuit of a degree has nothing to do with golf, you take all the skills that you learn at school and then you apply them to the game of golf and all the practical experience that you’ve accumulated. It’s pretty unique that way.

If you’re in the field of golf course architecture, it’s a group that you want to be a part of. When I was just becoming acquainted with the profession, it was a goal from the get-go. It’s a professional organization, and there is a pretty substantial process that we go through to gain acceptance into the group. It begins with following a pretty stringent set of criteria as far as projects completed, types of projects, and what you did on those projects. Then you get interviewed by your peers and voted on.

So it’s a lengthy process, but we have to make sure the people that get in are the real deal. Then we get together every year at least once for an annual meeting, and that’s usually the highlight of the year because everybody converges on a location. It might be Pinehurst, it might be Pebble Beach, it can be anywhere. Sometimes we go overseas and conduct our meetings and continuing education, but then we’re in the golf business, so we play golf, so that’s kind of fun too.

Could you explain what the ASGCA credential is?

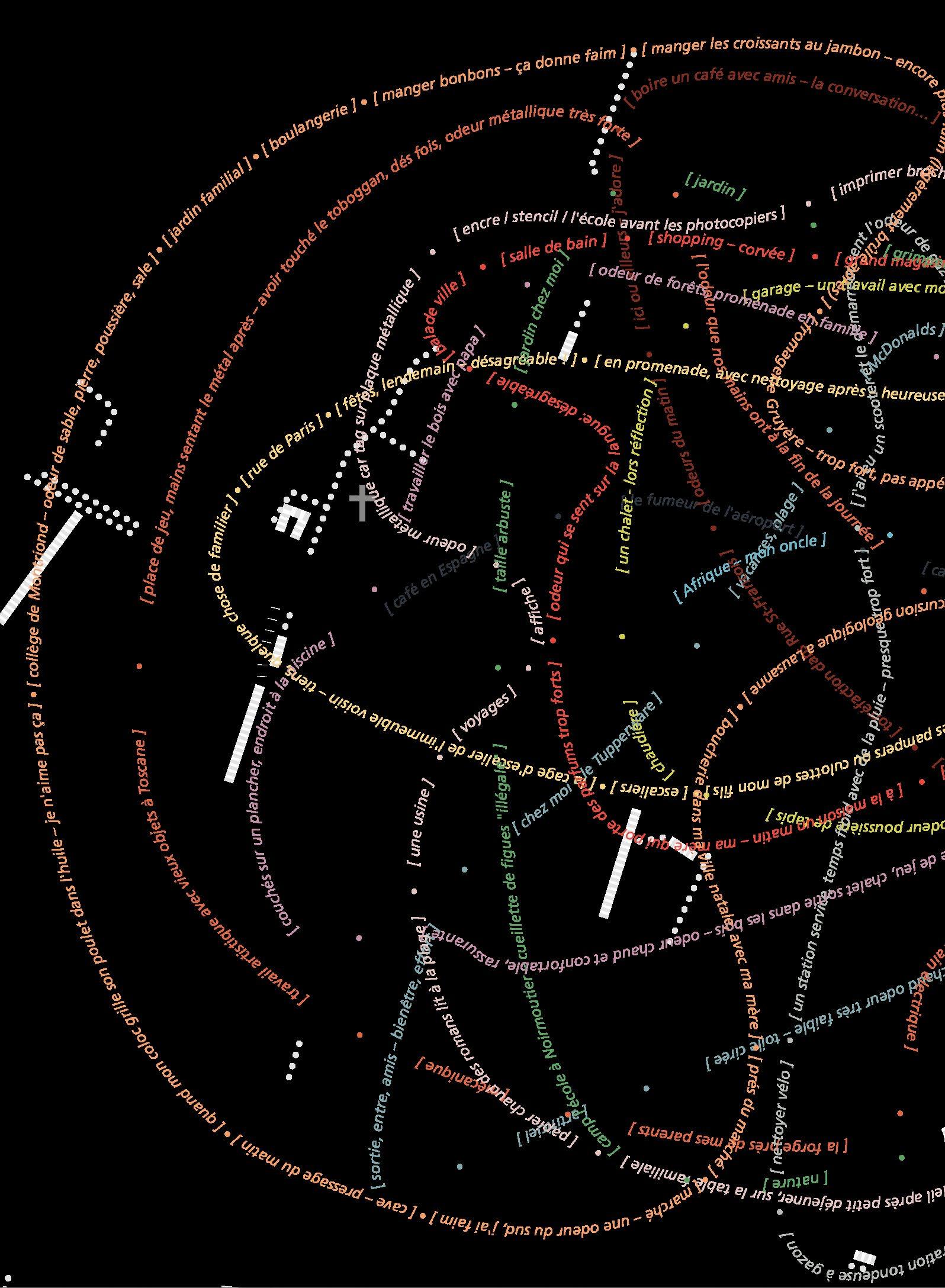

Atkins Golf Course concept sketches

In 2010, you started your own design practice. What was the big step or decision that influenced you to start your own business?

It all started in 2008 with the economic crash. A lot of the work we were doing in golf was related to real estate. We were doing golf communities, golf courses that have some sort of place in a residential development, and then all of a sudden those developments were not being developed any longer, or they’ve been halted.

That really put a clamp on the things that we were doing. So, over the course of two years, we basically took a staff of 15-16 designers, and we had to thin everything out to just the partners. We were left wondering, “How can we keep this alive?” There just wasn’t enough work, and so we all kind of had to scatter and go after a business in our own individual ways. That was something I really wanted to do anyway, but I had been under the comfort wings of a larger firm for 19 years, so it also seemed like a good time to go give it a shot.

In essence, that awful occurrence that happened in our economy was also like this invitation of let’s go see if we can do this. It was just like anybody else starting a business; you have modest beginnings; it’s stressful; we kind of had to start really slow and build up. We made it work, and now it’s as busy as ever. That was very rewarding; stressful, but I’m living the dream.

It was a little bit of a challenge for me because it was a public access facility. It was for the university and their golf teams, obviously looking to have a new place to call home.