Plot Rigoletto GIUSEPPE VERDI

PLOT

Setting: Place – Mantua, a city and province in Italy (also mentioned in Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet as the place where Romeo was exiled after he killed Tybalt)

Time – Mid-1500s (Approximately 100 years before the Mayflower arrived at Plymouth Rock)

ACT I, scene 1: The Duke of Mantua’s palace, during a formal party.

As the performance begins, the action revolves around the two dominant characters of this story. One is the ruler of the entire region, the Duke (in the 1500s, a duke was one step below a king), and the other is Rigoletto, the Duke’s hired full-time jester. The term “jester” refers to someone who performs for a patron’s amusement. In this case, the Duke enjoys Rigoletto’s biting comments and insults delivered to the Duke’s subjects.

During the party, what is played out on stage underscores a very important

aspect of the Duke and his relationship with Rigoletto – absolute power. The Duke has it and Rigoletto is protected by it. You also discover in the beginning that the Duke uses this power to satisfy his lust for women. Rigoletto mocks those at the party who are the boyfriends, husbands, and fathers of women of whom the Duke has taken advantage.

The men at court are called “courtiers,” similar to today’s lobbyists who sell access and information by seeking favors from people in power. Royal courts were centers of political activity and courtiers were often powerful people of influence. It is not a very wise idea to make them angry, but Rigoletto feels he can get away with it because he is one of the Duke’s favorites. One of the courtiers, Count Monterone, crashes the party to confront the Duke and condemn him for violating his daughter. Monterone is cruelly mocked by Rigoletto. Blinded by rage, humiliation, and disgust, Monterone calls down a curse (“maledetto” in Italian) upon Rigoletto.

Keep in mind, 500 years ago people believed that such a curse would be fulfilled.

Nowadays, people just get offended. This curse is a critical element in the plot. In fact the original title Verdi wanted for his opera was “La Maledizione,” or, “The Curse.”

ACT I, scene 2: An alleyway next to a house.

Earlier at the party, several men heard gossip that Rigoletto was secretly seeing a young woman. Now, they plan to kidnap her.

On his way home after the party (remember, after dark is a dangerous time in Medieval Europe), Rigoletto meets Sparafucile, a hired killer, who offers his services. (The name “Sparafucile” happens to mean, “to fire a gun.”) Rigoletto declines the offer, but remembers Sparafucile’s name.

In the house, the woman who everyone else believes Rigoletto has been secretly visiting is neither his lover nor his wife, but rather his daughter, Gilda. Unfortunately, the Duke has also met Gilda earlier that day in church and returns to seduce her posing as Gualtier Malde, a poor student. He does not know that Gilda is Rigoletto’s

daughter. His plan of seduction is interrupted by the arrival of a gang of men. The Duke, not wanting to be discovered, leaves knowing that Gilda has fallen in love with him.

The men abduct Gilda and encounter Rigoletto on their way out. They blindfold him and tell him that their victim is someone else in order to convince him to help them. After the men run off with Gilda, Rigoletto removes his blindfold and finds his daughter’s scarf in the street. He suddenly realizes they have abducted Gilda. He cries, “Ah, ah! The curse of Monterone!” as the curtain falls.

ACT II: The palace.

Having brought Gilda back to the palace, the kidnappers inform the Duke of what has taken place. Excitedly, he goes to where she is being held. Meanwhile, Rigoletto, in a panic, rushes in desperately looking for his daughter. The courtiers have their turn at ridiculing Rigoletto in revenge for his past performances at their expense. Upon learning that Gilda is with the

Duke, Rigoletto pleads to know where she is. But he is only taunted while the Duke is, at that very moment, alone with Gilda in his chambers.

Gilda escapes the Duke and rushes into Rigoletto’s arms. As Rigoletto swears retaliation for the Duke’s crime, Monterone is led to his imprisonment (the Duke wasn’t too happy about being insulted) and the despair of the two fathers contrasts with Gilda’s inexplicable pleading for her father to forgive the Duke.

ACT III: An inn by the river.

Rigoletto has brought Gilda to an inn along the river in a rundown part of town. It belongs to Sparafucile and his sister Maddalena. It is obvious that these two engage in a variety of criminal activity, probably including prostitution. The Duke arrives and Rigoletto forces his daughter to watch the Duke’s behavior through a crack in the wall of the building so she will realize the true nature of the man with whom she is in love.

Figuring that his daughter has seen

enough, Rigoletto orders Gilda to leave and turns back to hire Sparafucile to kill the Duke. As a storm gathers, he tells Sparafucile that he will come back at midnight to retrieve the corpse in a sack.

Maddalena, however, has also fallen in love with the Duke and convinces her brother, Sparafucile, to kill the next person who comes into the tavern and stuff that body in the sack instead. Gilda, who has slipped back, overhears their conversation. Convinced that it is the only way she can spare the Duke’s life, Gilda chooses to become Sparafucile’s next victim. As the storm grows more and more violent, she is murdered.

Rigoletto returns to claim his prize. As he begins to drag the sack to the river for disposal, he hears the Duke’s voice singing in the distance and realizes that the body he is carrying is not the Duke’s. He rips open the sack and discovers, to his horror, his beloved Gilda. In agony, he cries once again, “the curse, the curse of Monterone!”

THE DUKE OF MANTUA (Alter Ego: Gaultier Malde, a poor student)

RIGOLETTO

The Duke’s jester

GILDA Rigoletto’s daughter

GIOVANNA Gilda’s nurse

MONTERONE Courtier of the Duke

SPARAFUCILE Professional Assassin

MADDALENA Sparafucile’s sister

GILDA Rigoletto’s daughter

GIOVANNA Gilda’s nurse

MONTERONE Courtier of the Duke

SPARAFUCILE Professional Assassin

MADDALENA Sparafucile’s sister

COMPOSER: GIUSEPPE VERDI

Verdi

Giuseppe Verdi (Italian for Joe Green) lived during a pivotal and tumultuous time for his country, for Europe, and for the arts, especially opera. He was born in 1813 and died in 1901. Over that span of time, Italy developed from a collection of city states into a unified country. Europe recovered from the chaos caused by the Napoleonic wars and entered into a period of great economic growth driven by rapid industrialization. The arts shifted from the Classical Style to the Romantic, which was characterized by less of a concern with formal construction and strict rules and an emphasis on strong emotions and personal experience.

Prior to Verdi’s birth, the French general, Napoleon Bonaparte, started numerous wars with most of France’s neighbors, particularly England. These conflicts caused great turmoil throughout Europe and drained much of their financial resources fighting for and against Napoleon’s aggression. Napoleon invaded Italy and was able to crown himself (a Frenchman) King of Italy because of the power vacuum created by competing city states. It wasn’t until 1861 (the beginning of our own Civil War) that Italy was unified by the Savoy Monarchy.

social order. Verdi’s works, in particular, became immensely popular during a period in which operas were the most accessible entertainment of the time, similar to the blockbuster films or Broadway musicals of today. Verdi was also very active politically and held progressive views on the rights of people and freedom of belief. He possessed a strong sense of nationalism.

Verdi’s career as a composer spanned over 60 years and his work reflected the tremendous cultural and political changes of his era. One of his earlier operas, Nabucco, was embraced by the Italian people because it gave a musical voice to their own sense of despair and oppression at the hands of various European powers. In particular, a chorus piece from the third act, “Va, pensiero” (which refers to thoughts and memories of a beloved homeland by those in exile), became a de facto national anthem. In fact, the entire city of Milan sang it during Verdi’s funeral procession.

With the advent of industrialization and a broader distribution of wealth, artists no longer had to be so dependent upon royal patronage and could work for themselves. This led to creations which were more individualistic and often critical of the established political and

Rigoletto illustrates the composer’s work as it evolved into a much more Romantic style. This opera deals with extremes of emotion and profound tragedy. The style of composition necessitates a more “veristic” approach in the acting (from the Italian word “verismo” meaning realistic).

In his final years, Verdi returned to his lifelong admiration for and study of

Friend Gilda Rigoletto & Gaultier Malde on Facebook!

the plays of Shakespeare and composed Otello and Falstaff, which were deeper, richer, and more complex than his previous work. Indeed, Verdi, whose career spanned

almost a half century of evolution of this powerful art form, was an inspiration for many of the composers that followed.

WHAT’S IN A NAME?

The title of the opera, Rigoletto, is from the French word “rigoler,” which means “to laugh.” It is ironic that, though Rigoletto’s profession is to make the Duke laugh, his own life is no comedy. Verdi wanted to name the opera after the curse Monterone puts on Rigoletto. However, after the censors reviewed his work, they required Verdi not only to change the title, but also to change the jester’s name from Triboulet (the name of the historical jester of François I) to Rigoletto.

LIBRETTIST:

Piave

FRANCESCO MARIA PIAVE

“Libretto” is the Italian word for “little book” and refers to the booklet in which the lyrics of the opera are written. In contrast to most of today’s songwriters, the majority of opera composers hired someone else to create the words sung by the performers. The relationship between librettist and composer is often a difficult one –especially for the librettist.

with one of history’s most demanding composers of opera, Piave established a close friendship with Verdi. Perhaps Verdi’s operas would not have become so successful or popular without Piave’s contributions.

This was certainly the case for Francesco Maria Piave. Verdi was a demanding taskmaster, insisting on economy of language. Giving explicit instructions for what the characters would express, he often dictated long passages in prose that he demanded be put into arresting poetic language. Verdi harassed Piave unmercifully until he got his way. He would even give Piave’s drafts to other librettists to revise and edit!

Fortunately, Piave was not only a clever poet with an extensive vocabulary, but also an experienced stage director. He possessed a solid foundation in theatrical expertise and understood how a theater functions; he could see in his “mind’s eye” how his words could be brought to life. All this enabled Piave to maintain a long and fruitful 23-year-long partnership with Verdi, collaborating on many of the composer’s important works, including La Traviata and Macbeth.

Victor Hugo (1802-1885) was a French poet, novelist, statesman, and playwright. In fact, one of his novels, Les Misérables, was the inspiration for the Broadway musical of the same name. He was a political activist and a passionate believer in free thought and democratic principles.

In particular, Hugo was particularly opposed to the “divine right” of kings and the monarchy in general. He believed the French Revolution (17891799), which brought down the French King Louis XVI, was a great event in the history of civilization.

His hostility to royalty was amply revealed in his play, Le Roi s’amuse, which dealt with the life of the sixteenth century king, Francois I. Hugo portrayed this royal personage as frivolous, capricious, self-indulgent, and petty – in short, a lousy ruler. However, by the time the play opened in 1832, the monarchy was restored in France, and the aristocracy did not like being “dissed.” France’s king at the time, Louis-Phillipe, banned the play from being performed. Naturally, Hugo was upset. He went to

Sadly, in 1867, Piave suffered a massive stroke that left him unable to speak or walk. Unable to work, he was generously supported by Verdi until his death in 1876. In spite of the difficulty of working

court to have the ban removed, lost the lawsuit, and the play remained unperformed in France for the next 50 years, although it was very popular in print and was staged in the United States. Hugo

INSPIRATION: VICTOR HUGO

Artists are often inspired by current or historical events and may also be inspired by an existing work of art. Some of today’s films, for instance, are inspired by novels (Pride and Prejudice), musicals (Sweeney Todd), comic books (Batman, Superman), or even a theme park ride (Pirates of the Caribbean). In the case of Rigoletto, Verdi was inspired by the play by Victor Hugo, Le Roi s’amuse (loosely translated, The King’s Amusement).

Verdi, a contemporary of Hugo, adapted the play into an opera. Remember that Verdi, too, was a firm believer in people’s freedom and was a statesman, as well. Verdi, too, was censored and forced to change the names and location of the story (from France to Italy) in order for the opera to be permitted to open. Ironically, Verdi’s opera was performed over 100 times in Paris during the period in which Hugo’s play, the inspiration of the opera, was still banned!

Hugo was annoyed by the popularity of the opera until he went to see a performance for himself. He enjoyed it so much that his annoyance changed to admiration for the operatic treatment of his work. Subsequently, Verdi also turned to two other of Hugo’s plays into operas, Ernani and Lucrezia Borgia. The latter opera will be part of Washington National Opera’s 20082009 season featuring Renée Fleming, one of today’s operatic stars.

Censor

CENSORSHIP

A significant issue surrounding the creation of Rigoletto is the subject of censorship (refer to the section about Victor Hugo). Censorship strictly defined (dictionary.com) means, “the suppression or deletion of objectionable information, as determined by a censor.” Throughout the history of the arts and of society, in general, there has been a tension between agents of the state (e.g. royalty or politicians) and artists who use their work to criticize policies or behavior with which they disagree or condemn and, conversely, to promote behavior and practices that comment on an existing norm.

Because of the arts’ power to emotionally engage others, people in positions of authority have always been wary of artists. Often censorship swirled around issues of morality. Michelangelo’s monumental painting on the Sistine Chapel’s ceiling was condemned by some because of its depiction of nudity. In literature, there was the late 18th-century publication of Thomas Bowdler’s Family Shakespeare that deleted all references to violence and sex from the playwright’s works. And, of course, every time a new style of music presents itself, efforts are made to restrict its availability.

During the 20th century, in Stalin’s Russia, Hitler’s Germany, Mussolini’s Italy, and Mao’s China, the arts were seen as tools that should only be used to glorify the state or political system. Artists who felt otherwise were often brutally suppressed. Thus, books such as Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s The Gulag Archipelago were banned in the Soviet Union, avant-garde visual art (termed “degenerate art” by Hitler) was destroyed by the Nazis, art was subverted by Mussolini to function as propaganda, and artists were slaughtered and imprisoned during China’s “Cultural Revolution.” These are just a few examples of totalitarian regimes’ efforts to bend art and artists to their own purposes.

The conflict between those in authority who seek to maintain what they determine to be acceptable and artists, who disagree, is an ageold struggle that continues today.

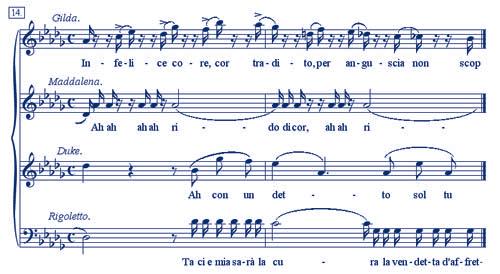

VERDI’S MASTERY: THE QUARTET

Quartet

Verdi was a musical pioneer. He built upon the conventions of past and present composers, but he was one of the first to consciously compose the music in direct support of the dramatic emotions in the story. Verdi gave special attention not only to the musical elements, but also to the staging, lighting, and the dramatic tension with which the singers delivered the music. Although he may have been very difficult to work with, his attention to detail paid off; the quartet in the final act of Rigoletto is one of Verdi’s many triumphs.

Think about what it would be like if you had four people simultaneously reciting a different monologue contemplating their inner turmoil, such as “To be or not to be…” from Shakespeare’s Hamlet Would you be able to understand any of it, much less understand why four people should be speaking at the same time anyway? This is the beauty of music as an artistic medium. Verdi is able to take the emotions of four different characters and weave them together so that each one can be understood on its own. At the same time, all four parts enhance and support each other melodically to sound beautiful together.

The first part of the quartet is bantering between the Duke and Maddalena, and the music reflects this: the voice parts have short, irregular chunks of melody, and the real tune is in the orchestra. It is as though the characters were just talking and flirting casually at a party, with music playing in the background.

Eventually, the Duke decides to end the casual conversation and take charge. He does so with an over-thetop romantic move: he sings a serenade

just like a song on the radio today.

The other characters are silent while he sings a whole verse by himself. When they join in, each weaves a unique musical line around the Duke’s song, a line that reflects their own particular feelings. Maddalena, who is laughing at being serenaded like a highborn lady, has a tune that is always bouncy, fluttering up and down like laughter. Rigoletto, planning revenge against the Duke, has a part that is centered on the

to Maddalena, calling her “Bella figlia dell’amore,” or “beautiful child of love.”

This is the first thing in the quartet we could call a song: it has regular four-bar phrases and repetition in the melody,

dark low notes of his voice, muttering and growling, holding back his rage. Only while singing the words “Io saprò lo fulminar,” (“I will strike him down!”) does he burst into his high register, close to losing control. Gilda, betrayed, demonstrates her pain in long notes that soar over the ensemble. Her melodic lines are repeatedly interrupted by rests, as though her voice is broken by sobbing.

Four people are singing at once, each with different text, so it is impossible to hear every word from every character. But by giving each of them a distinctive musical line and blending those lines together, Verdi allows us to grasp all their emotions at once. It is a stunning achievement that is only found in opera and musical theater.

Opera

AT THE OPERA HOUSE

You will see a full dress rehearsal, an opportunity to get an insider’s look into the final moments of preparation before an opera opens. The singers will be in full costume and makeup, the opera will be fully staged, and a full orchestra will accompany the singers, who may choose to “mark,” or not sing in full voice, in order to save their voices for the performances. A final dress rehearsal is often a complete run through, but there is a chance the director or conductor will ask to repeat a scene or two. This is the last opportunity the performers have to rehearse with the orchestra before opening night, and they therefore need this valuable time to work. The following will help you better enjoy your experience of a night at the opera.

• Dress in what is comfortable for you, whether it is nice jeans or a suit, keeping in mind this is an opera house. Please do not take off your shoes or put your feet on the seat in front of you. Live theater is usually more formal than a movie theater.

• “Dressy-casual” is usually what people wear - unless it is opening night, which is typically quite formal. Any night at the opera can be a fun opportunity to get dressed in formal attire.

• Arrive on time. Latecomers will be seated only at suitable breaks and often not until intermission.

• Please respect other patrons’ enjoyment by not leaning forward in your seat so as to block the person’s view behind you, and by turning off cell phones, pagers, watch alarms, and other electronic devices that make noise.

• At the very beginning of the opera, the concertmaster of the orchestra will ask the oboist to play the note “A.” Listen carefully. You will hear all the other musicians in the orchestra tune their instruments to match the oboe’s “A.”

• After all the instruments are tuned, the conductor will arrive. Be sure to applaud!

• Feel free to applaud (or shout Bravo!) at the end of an aria or chorus piece to signify your enjoyment. The end of a piece can be identified by a pause in the music. Singers love an appreciative audience!

• Go ahead and laugh when something is funny!

• Taking photos or making audio or video recordings is strictly forbidden.

• Do not chew gum, eat, drink, or talk during the performance. If you must visit the restroom during the performance, please exit quickly and quietly. An usher will let you know when you can return to your seat.

• Let the action on stage surround you. As an audience member, you are a very important part of what is taking place. Without you, there is no show!

• Read the English supertitles projected above the stage. Operas are usually performed in their original language. Opera composers find inspiration in the natural rhythm and inflection of words in particular languages. Similar to foreign films, supertitles help the audience gain a better understanding of the story.

• Listen for subtleties in the music. The tempo, volume, and complexity of the music and singing depict the feelings or actions of the characters. Also, notice repeated words or phrases; they are usually significant.

• Have fun and enjoy the show!!

EDUCATION AND COMMUNITY PROGRAMS DONORS

$50,000 and above

Mr. and Mrs. John Pohanka D.C. Commission on the Arts and Humanities and the National Endowment for the Arts

$20,000 and above

John and Cora H. Davis Foundation

Friedman Billings Ramsey

The Morningstar Foundation

$10,000 and above

Clark-Winchcole Foundation

Jacob & Charlotte Lehrman Foundation

The Honorable and Mrs. Jan M. Lodal

Prince Charitable Trusts

The Washington Post Company

$5,000 and above

I-Education Holdings

Mr. and Mrs. Louis R. Cohen

Theodore H. Barth Foundation Humanities Council of Washington, D.C.

$2,500 and above

Mr. Walter Arnheim

The Max and Victoria Dreyfus Foundation Industrial Bank

Target

The K.P. and Phoebe Tsolainos Foundation Wachovia Foundation

$1,000 and above

Mr. and Mrs. Robert H. Craft, Jr. CareFirst BlueCross BlueShield

Dr. and Mrs. Ricardo Ernst

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Professor Martin Ginsburg

Horwitz Family Fund

Founded in 1956, Washington National Opera is recognized as one of the leading opera companies in the United States. Under the leadership of General Director Plácido Domingo, Washington National Opera continues to build on its rich history by maintaining consistently high artistic standards and balancing popular grand opera with new or less frequently performed works.

As part of the Center for Education and Training at Washington National Opera, Education and Community Programs provides a wide array of programs to serve a diverse local and national audience of all ages. Our school-based programs offer students the opportunity to experience opera through in-depth, yearlong school partnerships: the acclaimed Opera Look-In, the District of Columbia Public Schools Partnership, and the Kids Create Opera Partners (for elementary schools), and the Student Dress Rehearsal (for high schools) programs. Opera novices and aficionados of all ages have the opportunity to learn about the season through the Opera Insights series, presented on the Kennedy Center Millennium Stage. All Insights are free, open to the public, and archived on the WNO website. Outreach to the greater Washington D.C. community is achieved through our public Library Program, the Family Look-In, and the Girl Scout Program. Our summer training programs give youth age 10-18 an opportunity to experience first-hand what goes into an opera performance through Opera Discovery Camp, and Opera Institute for Young Singers. For more information on the programs offered by Washington National Opera, please visit our website at www.dc-opera.org.

CREDITS

Author:

Bruce D. Taylor

Associate Director, Education and Community Programs

Editors:

Rebecca Kirk

Education and Community Programs Associate

Michelle Krisel Director, Center for Education and Training

Stephanie M. Wright Assistant Director, Education and Community Programs

Catherine Zadoretzky Editorial Assistant

Graphic Design:

Ceci Dadisman

CeciCreative