TAMERLANO

Tamerlano

GEORGE FRIDERIC HANDEL

A FOREIGN LAND

history

Imagine entering the world of Handel’s Tamerlano as entering a foreign country. In order to understand this foreign land, you must first understand its history. The winding and complex plot of Handel’s Tamerlano is rooted in ancient eastern history. In bringing the story to life on stage, directors must take great care not to lose the audience as a host of characters with bizarre names travel to a multitude of ancient eastern locations.

In addition to its intricate plot, Tamerlano features a musical style that may not be familiar to you. Handel composed operas nearly 400 years ago, so his works have a distinctly different sound and structure from the more well known operas composed during the last 200 years. Though Tamerlano may be as foreign to you as a far off country, understanding what Handel meant to portray in this ancient story will make your journey rich and memorable.

HISTORY INFLUENCES STORY

The protagonist in Tamerlano is based on a historical figure, Timur “the lame.” He was a Turkish nomadic bandit who became emperor of Central Asia during the later half of the 14th century. He conquered an empire that, in modern times, encompasses southeastern Turkey, Syria, Iraq, Kuwait, Iran, Kazakhstan, Afghanistan, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Pakistan, northwestern India, and southwest China.

Many artists throughout history have been inspired by Timur’s story. Christopher Marlowe, a contemporary of William Shakespeare, wrote a play depicting his conquests called Tamberlaine; Edgar Allen Poe wrote a poem entitled Tamerlane; and even Microsoft created a videogame, “Age of Empires II,” featuring a hero named Tamerlane. Handel’s opera is based on Jacques Pradon’s play, Tamerlan, ou La mort de Bajazet. To the western world, this story of a bandit rising to become an emperor in the Middle East was an exotic and fascinating spectacle—perfect subject matter to captivate an audience.

BAROQUE MUSIC

Handel was a composer during what is now referred to as the Baroque period in music. The Baroque style was also manifested in such artistic forms as architecture and visual art. The defining characteristic of all art forms during this period was ornamentation; basic artistic structures and forms grew in complexity and there was an increased reference to such grand emotions as love and revenge. It was during this period that opera was born. This early example of opera is now referred to as opera seria. The term “baroque” comes from the Italian word barocco, which philosophers used to describe a contorted idea or a long, involved thought process. Aptly describing baroque opera seria, this new art form meant to instruct the audience using a format that echoes ancient Greek tragic theater.

Ancient Greek Statue

OPERATIC STRUCTURE

Seeking to bring back the conventions of Greek tragedy also explains the formal structure of baroque opera. Greek tragedy alternated between episodes (spoken monologue or dialogue) and stamisa (songs sung by the chorus). Baroque opera is similarly made up of recitative (sungspoken dialogue with minimal accompaniment) and da capo arias (songs with a specific three-part structure).

The three-part structure breaks down like this:

- The first section of a da capo aria could, in theory, be sung on its own and not sound like anything was missing.

- The second section compliments the first but varies in tempo, musical texture, and mood (similar to a “bridge” in contemporary musical form).

- The third section is the da capo, which is Italian for “back to the beginning.” The first section is sung a second time, but the melody is improvised on (or “ornamented”) by the singer in order to show off their vocal acrobatics.

You may hear a similar technique in jazz. The first part of the song is played “straight up” or as written and is followed directly by the bridge. The song returns to the “head” or beginning, but the original melody is improvised on by the lead instrument or vocalist. A vocalist improvises by “scatting” around the melody while still keeping it recognizable.

In baroque opera, the alternation of recitative and da capo arias is used deliberately. Recitative is dialogue or monologue that advances the action of the plot. During an aria, no action takes place. This is the moment where the character steps out of the action and sings about his or her emotions. The reason the aria’s first section is repeated in the

da capo is not only to give the singer a chance to display their vocal skill, but also to delve deep into the emotion exploring each nuance and bringing it forward through expression to the audience.

THE HEROIC HIGH VOICE

The characters of Andronico and Tamerlano in Tamerlano are each sung by countertenors, men who sing in a high range similar to a soprano. In baroque opera seria, the countertenor role is usually the hero. Handel departed from the norm and wrote the part of the hero for a tenor voice. This does not mean, however, that Andronico and Tamerlano lack heroic qualities. Handel preferred to paint these two characters in a more controversial light, highlighting both their heroic and barbaric traits.

Although, at first, countertenors may seem like men singing like women, take a moment to think about songs you know where the lead male singer sings in falsetto, hitting high notes. Operatic roles for this voice type have always been rare, but, in contemporary music, men who sing in falsetto are common. You might agree that even today these stars have a heroic quality to them. Although this voice and its heroic nature can be traced as far back as ancient Middle Eastern and African religious and cultural traditions, listen to the following songs from the 20th century. Other artists who have mastered the high range in popular music include Justin Timberlake, Michael Jackson, Queen, The Bee Gees, and Frankie Valli.

SIDE NOTE:

In Washington National Opera’s 2008 production of Tamerlano, the part of Andronico is sung by a woman. In opera this is referred to as a “trouser role.” Although not entirely unheard of in Handel’s time, women singing the roles of young men in opera became more common several hundred years later and the tradition is still honored today.

CONTEMPORARY EXAMPLES OF THE HEROIC HIGH VOICE

SONG TITLE: ARTIST/ALBUM:

CULTURE WARS

The history of humankind reveals a perpetual struggle between the cultures of dominant societies and weaker societies. From Babylon to Egypt, Carthage to Greece, Greece to Rome, Europe to North Africa, Spain to England, England to France, France to Germany, China to Japan, Europe to the United States, history can be benchmarked by a succession of one culture’s dominance over another.

It naturally follows that artistic works celebrate the dominant culture, which is driven by people in power who are influenced by love, greed, jealousy, envy, and, of course, pure power itself. Tamerlano, in essence, is such an artistic creation illustrating how these human emotions drove those in power to seek dominance over others.

VIRTUAL TAMERLANO!

(Inspired by Age of Empires II)

Once again, imagine you are entering a “new world” of Tamerlano, but this time it is a virtual world. Pick a character from the list below, and imagine that strangers from across the world have assumed the roles of the other characters. Each character has certain traits. Add to your character’s list of traits, filling in such details as: How would your character dress or act? What is your character’s history? Under what circumstances did he or she grow up? What beliefs does the character hold dear? What grudges, if any, does the character have?

CHARACTERS

Tamerlano:

All powerful conqueror

Engaged to marry Irene

Strongly attracted to Asteria

Andronico:

Best Friend of Tamerlano

In love with Asteria

Told to marry Irene

Bajazet:

Prisoner of Tamerlano

Father of Asteria

Proud even in defeat

Irene:

Engaged to marry Tamerlano

Friends with Andronico

Friends with Asteria

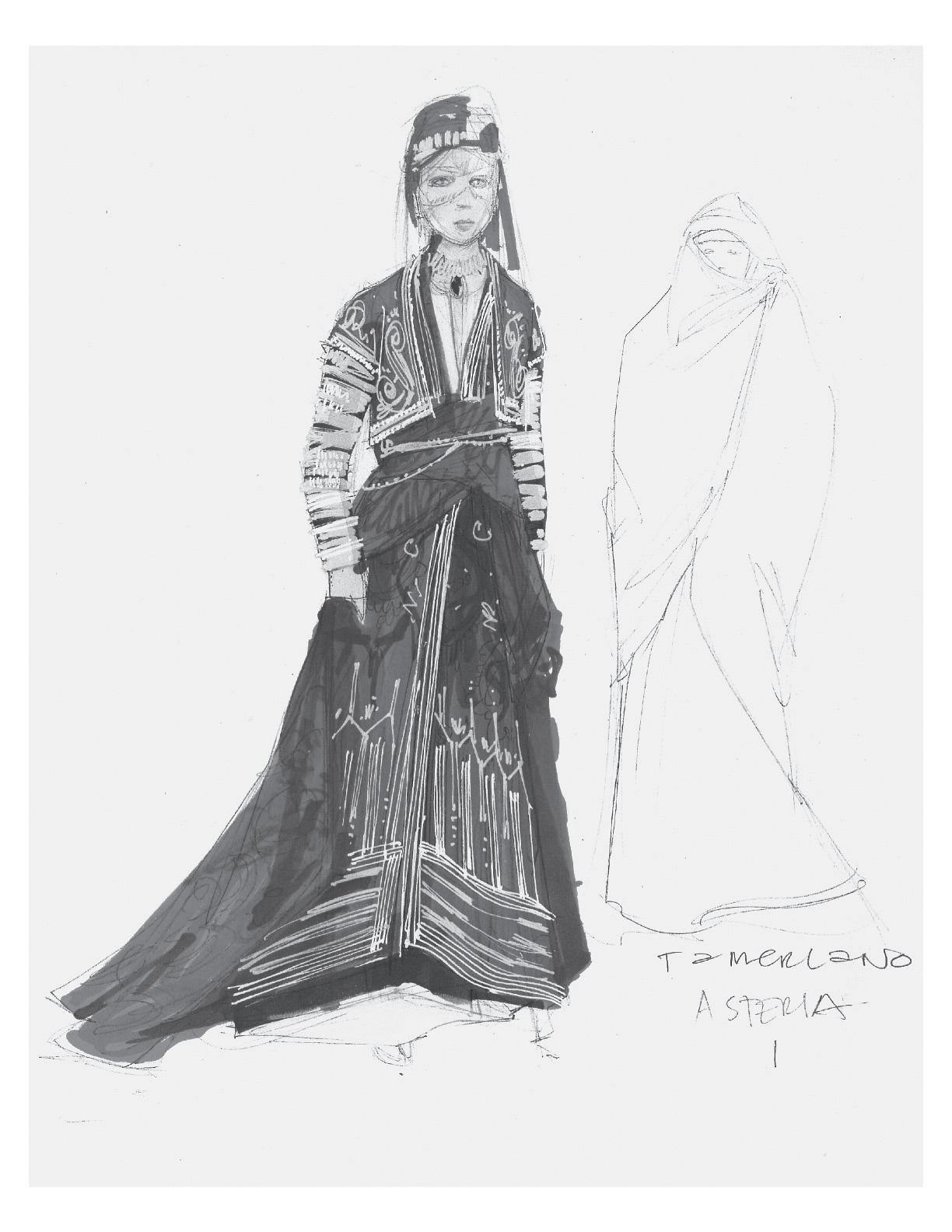

Asteria:

Daughter of Bajazet

In love with Andronico

Faithful to those she loves

Leone:

Friend of Andronico

Wants to help Irene

Wise, but has no influence over others

MOTIVATIONS

Someone…

• wants to kill someone else

• wants to assassinate a leader

• wants to commit suicide

• takes poison because they have no other option

• hopes that love will win over revenge

• pleads for mercy for someone else

• manipulates a friend to get what he/she wants

• disguises him/herself to find out more information

In what ways could this story unfold with these characters and plot turns? Use these puzzle pieces of a plot to create your own story, and, when you see the opera, compare it with the story you created. How does your story end? Who wins, and what does it mean to win?

A BAROQUE OPERA IN A MODERN DAY SETTING

design

Tamerlano is about the title character brutally overthrowing different rulers, showing no mercy, and appropriating lands as his own. If we were to see this story unfold as it did in the ancient Middle East, it would look very bloody and even barbaric to us now. However, that does not mean that one culture or country dominating another no longer exists. On the contrary, it is only much more subtle. In modern day diplomacy, the international “playing field” may seem much more even, but just because everyone dresses the same and knows the conventions of a business meeting, does not mean that each player holds the same amount of power. These subtleties are addressed in the opera in order to make a social comment on contemporary society and to point out that issues of cultural dominance are still relevant today.

Baroque opera must also be adapted musically. Not only is there a difference in how the instruments are built and tuned today, but the standard pitch is nearly one half step higher than it was when Handel originally composed the music. Most of the orchestra is made up of stringed instruments, including one not normally found in a standard orchestra called an archlute, which is related to a lute and has a very long neck in order to play a large range of notes.

SET DESIGN ILLUSTRATES MORE THAN SETTING

In life and on stage, the setting has a greater impact on how you feel and than you may be aware of. Imagine that you are visiting another country and going through customs. The customs officers decide to question you further and bring you into a private room. The room is stark and virtually empty with no place to sit down, no décor, and no windows. How might you feel in that situation? Do you think you would feel differently if you had a plush couch to sit on and there were fresh cut flowers on a coffee table?

Think about the industry of interior design. Why is it that people make so much money advising others on how to decorate a room? Atmosphere can be created by what is or is not in a space and how they relate to other things in the space. These details can evoke emotion from the people in that space. On stage, the setting not only helps you know where the story takes place, but is also used to enhance emotions that can sometimes be so subtle that you would not notice the effect unless the setting were taken away. Think in what other ways your surroundings affect the way you feel in certain locations.

COMPOSER AND LIBRETTIST

If you turn on the radio around Christmas time, you are likely to hear the “Hallelujah Chorus” from Handel’s Messiah, one of the most popular works associated with the Christmas season.

Messiah was composed by George Frideric Handel, born in Germany in 1685. While in his late 20s, Handel moved to London, England, where he lived the rest of his life. He wrote 42 operas, 29 oratorios, and countless other shorter works. Many of his operas were sung in Italian. Curious why a Germanborn composer would compose operas to be sung in Italian for an English audience? Such is the nature of opera as an international Western art form.

It was in London where Handel met Nicola Francesco Haym, an Italian artist-of-all-trades (composer, librettist, musician, stage manager, etc.), born to German parents, who also moved to London in the early 1700s. They were colleagues and often collaborated on operas.

These “Italian style” operas that Handel wrote were extremely popular in London at the time. Many of them, however, required a singer who was the fashionable equivalent of a countertenor, called a castrato. Through voluntary castration, a castrato’s voice was artificially maintained into adulthood from the high range he had as a boy soprano. When the castrato went out of fashion, so too did most of these operas.

Today, we know Handel’s music primarily through his Messiah and several orchestral works, such as Water Music and Music for the Royal Fireworks He also wrote an anthem that is performed at every coronation of a British monarch. His music continues to challenge singers with its highly ornamented, melismatic style, which calls for exceptional breath control. This style of singing is still practiced by cantors in Jewish synagogues, muezzins at Muslim mosques, and soloists at gospel concerts.

George Frideric Handel

George Frideric Handel

AT THE OPERA HOUSE

You will see a full dress rehearsal, an opportunity to get an insider’s look into the final moments of preparation before an opera opens. The singers will be in full costume and makeup, the opera will be fully staged, and a full orchestra will accompany the singers, who may choose to “mark,” or not sing in full voice, in order to save their voices for the performances. A final dress rehearsal is often a complete run through, but there is a chance the director or conductor will ask to repeat a scene or two. This is the last opportunity the performers have to rehearse with the orchestra before opening night, and they therefore need this valuable time to work. The following will help you better enjoy your experience of a night at the opera.

• Dress in what is comfortable for you, whether it is nice jeans or a suit, keeping in mind this is an opera house. Please do not take off your shoes or put your feet on the seat in front of you. Live theater is usually more formal than a movie theater.

• “Dressy-casual” is usually what people wear - unless it is opening night, which is typically quite formal. Any night at the opera can be a fun opportunity to get dressed in formal attire.

• Arrive on time. Latecomers will be seated only at suitable breaks and often not until intermission.

• Please respect other patrons’ enjoyment by not leaning forward in your seat so as to block the person’s view behind you, and by turning off cell phones, pagers, watch alarms, and other electronic devices that make noise.

• At the very beginning of the opera, the concertmaster of the orchestra will ask the oboist to play the note “A.” Listen carefully. You will hear all the other musicians in the orchestra tune their instruments to match the oboe’s “A.”

• After all the instruments are tuned, the conductor will arrive. Be sure to applaud!

• Feel free to applaud (or shout Bravo!) at the end of an aria or chorus piece to signify your enjoyment. The end of a piece can be identified by a pause in the music. Singers love an appreciative audience!

• Go ahead and laugh when something is funny!

• Taking photos or making audio or video recordings is strictly forbidden.

• Do not chew gum, eat, drink, or talk during the performance. If you must visit the restroom during the performance, please exit quickly and quietly. An usher will let you know when you can return to your seat.

• Let the action on stage surround you. As an audience member, you are a very important part of what is taking place. Without you, there is no show!

• Read the English supertitles projected above the stage. Operas are usually performed in their original language. Opera composers find inspiration in the natural rhythm and inflection of words in particular languages. Similar to foreign films, supertitles help the audience gain a better understanding of the story.

• Listen for subtleties in the music. The tempo, volume, and complexity of the music and singing depict the feelings or actions of the characters. Also, notice repeated words or phrases; they are usually significant.

• Have fun and enjoy the show!!

EDUCATION AND COMMUNITY PROGRAMS DONORS

$50,000 and above

Mr. and Mrs. John Pohanka D.C. Commission on the Arts and Humanities and the National Endowment for the Arts

$20,000 and above

John and Cora H. Davis Foundation

Friedman Billings Ramsey

The Morningstar Foundation

$10,000 and above

Clark-Winchcole Foundation

Jacob & Charlotte Lehrman Foundation

The Honorable and Mrs. Jan M. Lodal

Prince Charitable Trusts

The Washington Post Company

$5,000 and above

I-Education Holdings

Mr. and Mrs. Louis R. Cohen

Theodore H. Barth Foundation Humanities Council of Washington, D.C.

$2,500 and above

Mr. Walter Arnheim

The Max and Victoria Dreyfus Foundation Industrial Bank

Target

The K.P. and Phoebe Tsolainos Foundation Wachovia Foundation

$1,000 and above

Mr. and Mrs. Robert H. Craft, Jr. CareFirst BlueCross BlueShield

Dr. and Mrs. Ricardo Ernst

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Professor Martin Ginsburg Horwitz Family Fund

Founded in 1956, Washington National Opera is recognized as one of the leading opera companies in the United States. Under the leadership of General Director Plácido Domingo, Washington National Opera continues to build on its rich history by maintaining consistently high artistic standards and balancing popular grand opera with new or less frequently performed works.

As part of the Center for Education and Training at Washington National Opera, Education and Community Programs provides a wide array of programs to serve a diverse local and national audience of all ages. Our school-based programs offer students the opportunity to experience opera through in-depth, yearlong school partnerships: the acclaimed Opera Look-In, the District of Columbia Public Schools Partnership, and the Kids Create Opera Partners (for elementary schools), and the Student Dress Rehearsal (for high schools) programs. Opera novices and aficionados of all ages have the opportunity to learn about the season through the Opera Insights series, presented on the Kennedy Center Millennium Stage. All Insights are free, open to the public, and archived on the WNO website. Outreach to the greater Washington D.C. community is achieved through our public Library Program, the Family Look-In, and the Girl Scout Program. Our summer training programs give youth age 10-18 an opportunity to experience first-hand what goes into an opera performance through Opera Discovery Camp, and Opera Institute for Young Singers. For more information on the programs offered by Washington National Opera, please visit our website at www.dc-opera.org.

CREDITS

Authors:

Rebecca Kirk

Education and Community Programs Associate

Bruce D. Taylor

Associate Director, Education and Community Programs

Editors:

Michelle Krisel Director, Center for Education and Training

Stephanie M. Wright

Assistant Director, Education and Community Programs

Catherine Zadoretzky

Editorial Assistant

Graphic Design:

Ceci Dadisman

CeciCreative

General Director Placido Domingo