STEPHEN ONGPIN FINE ART

Cover:

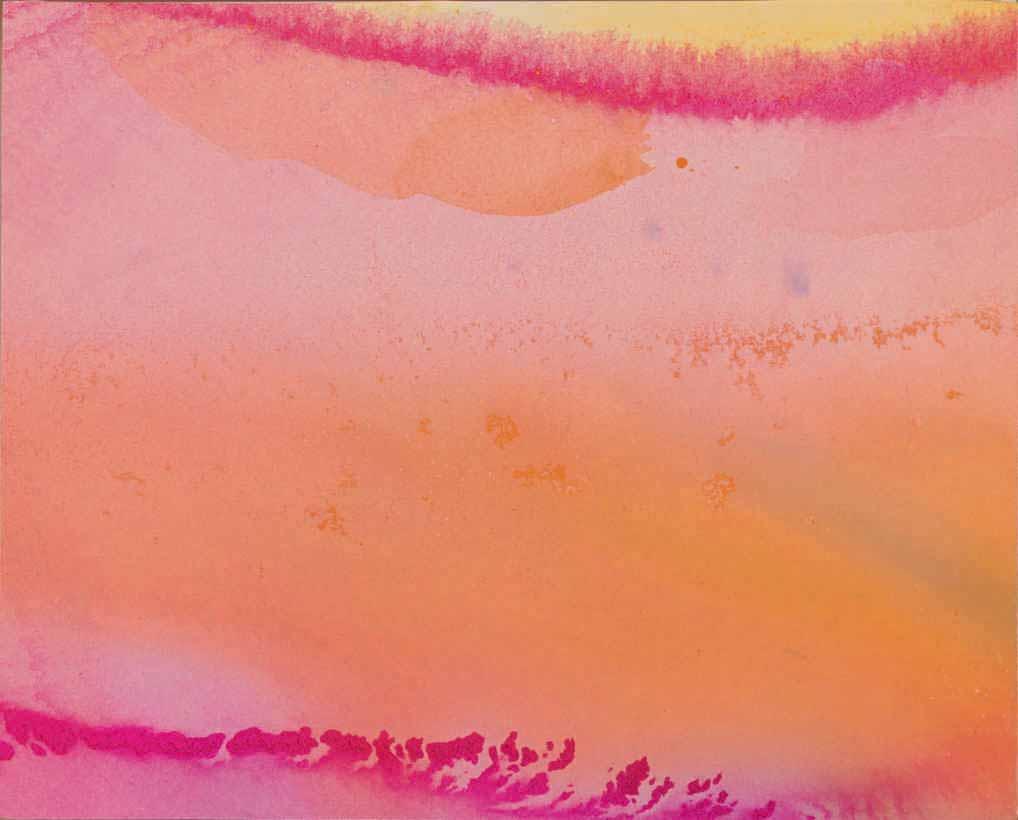

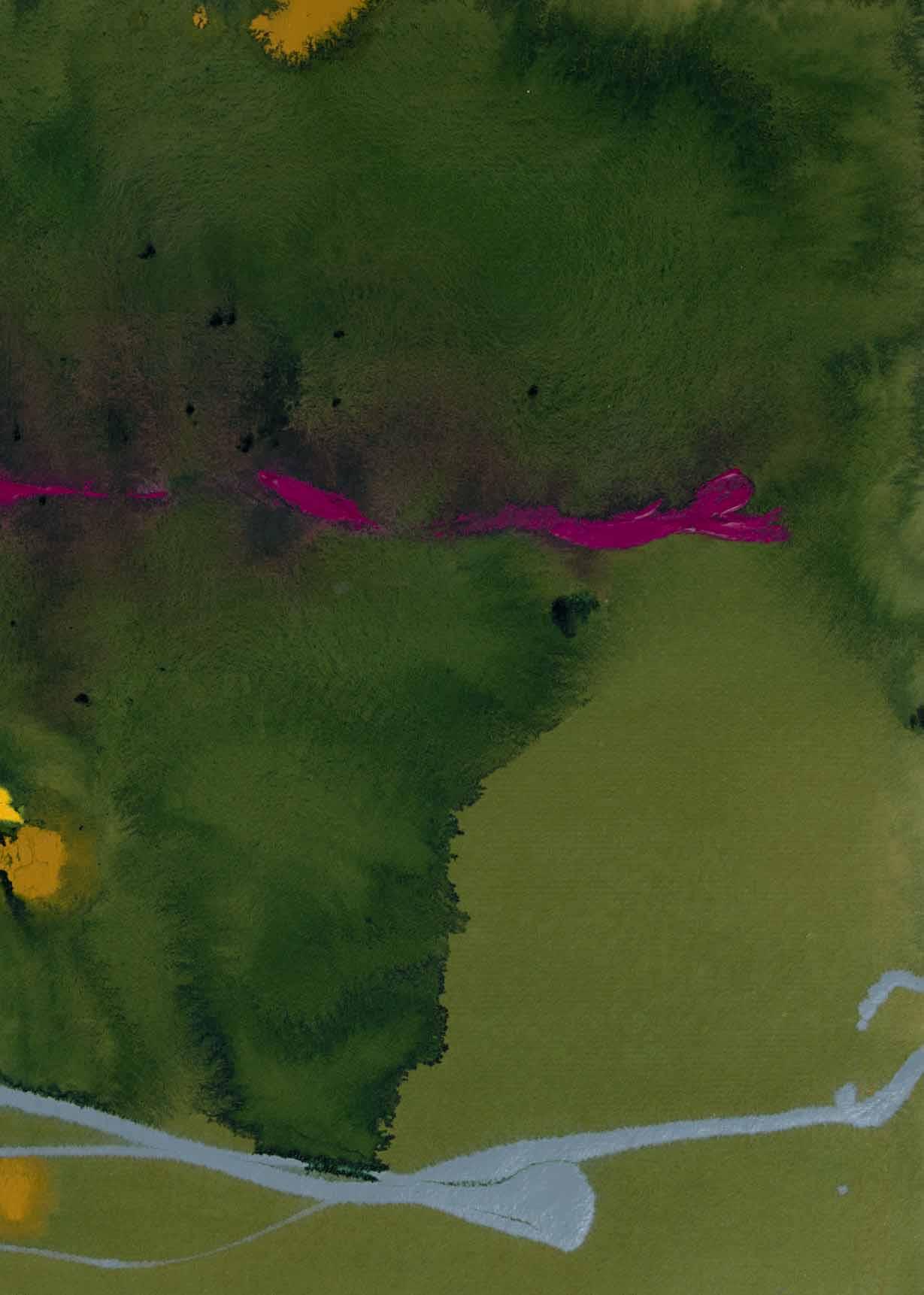

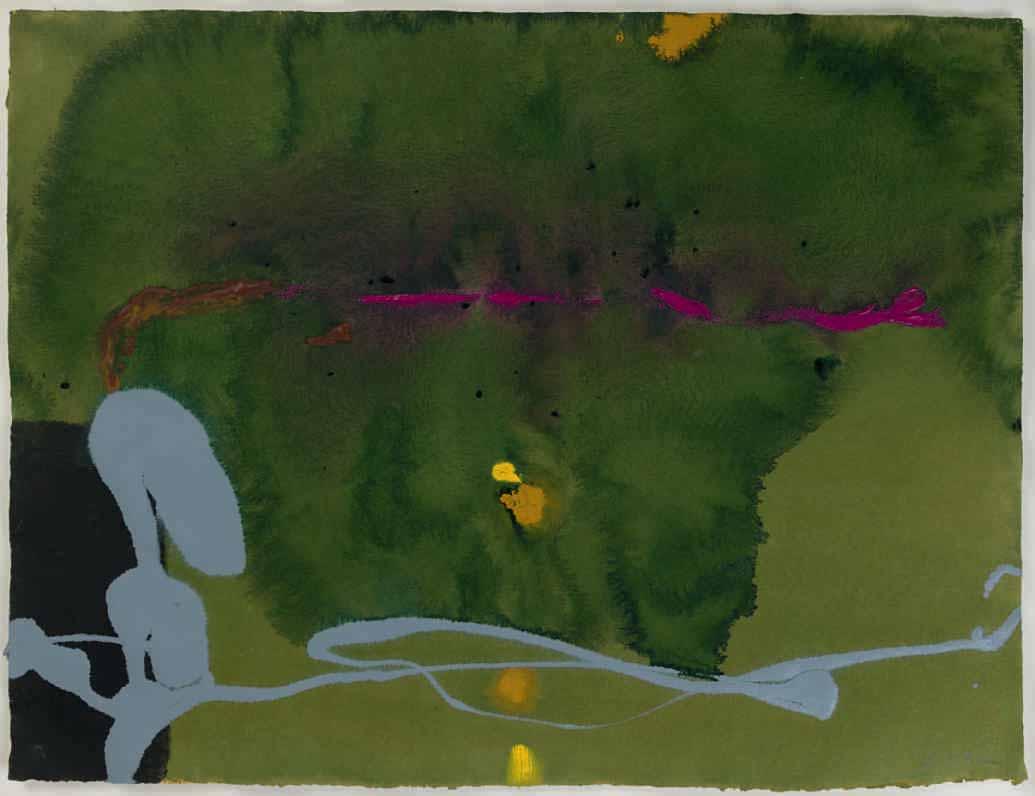

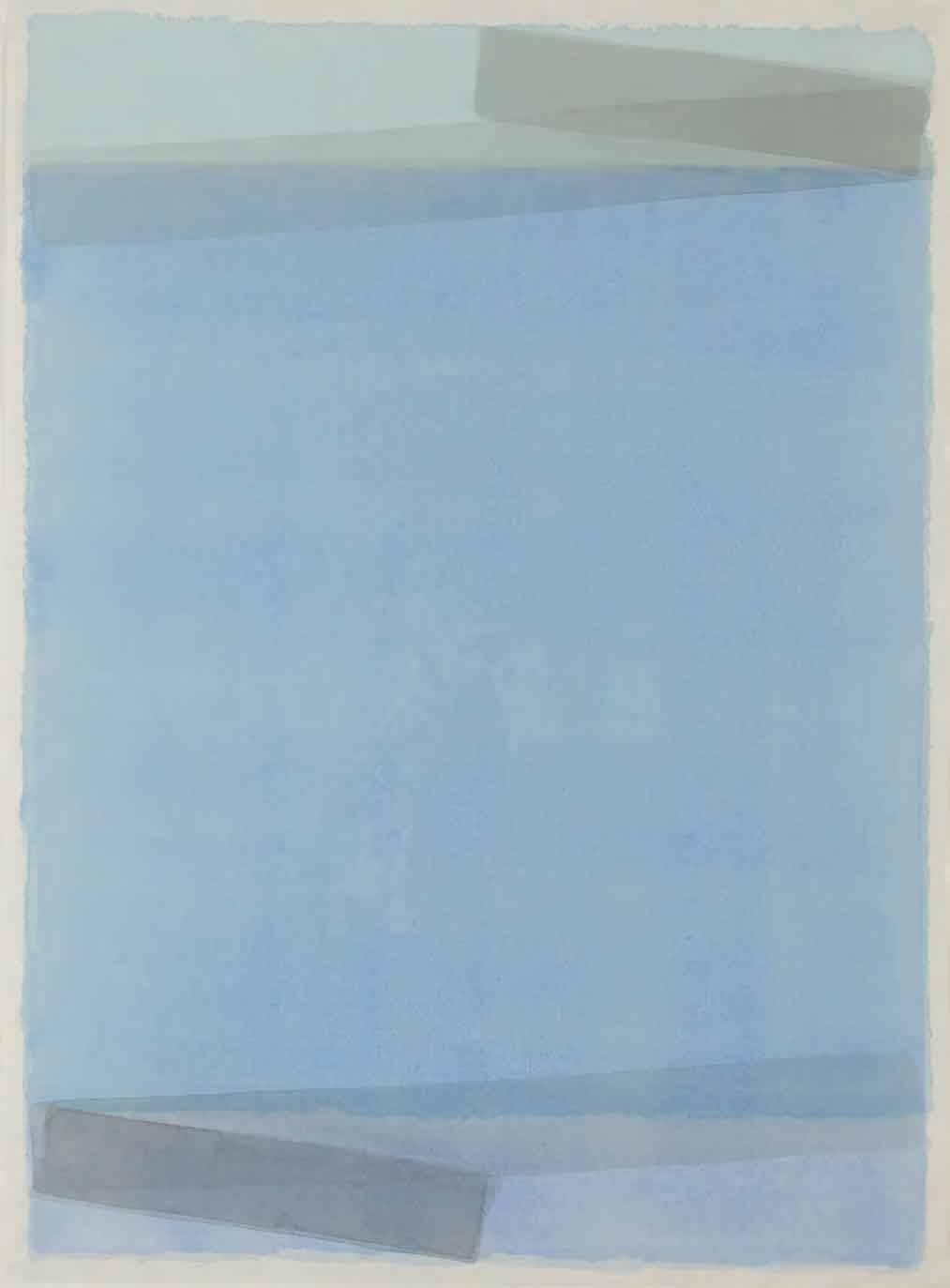

Helen Frankenthaler (1928-2011)

Untitled (P91-20), 1991

No.25

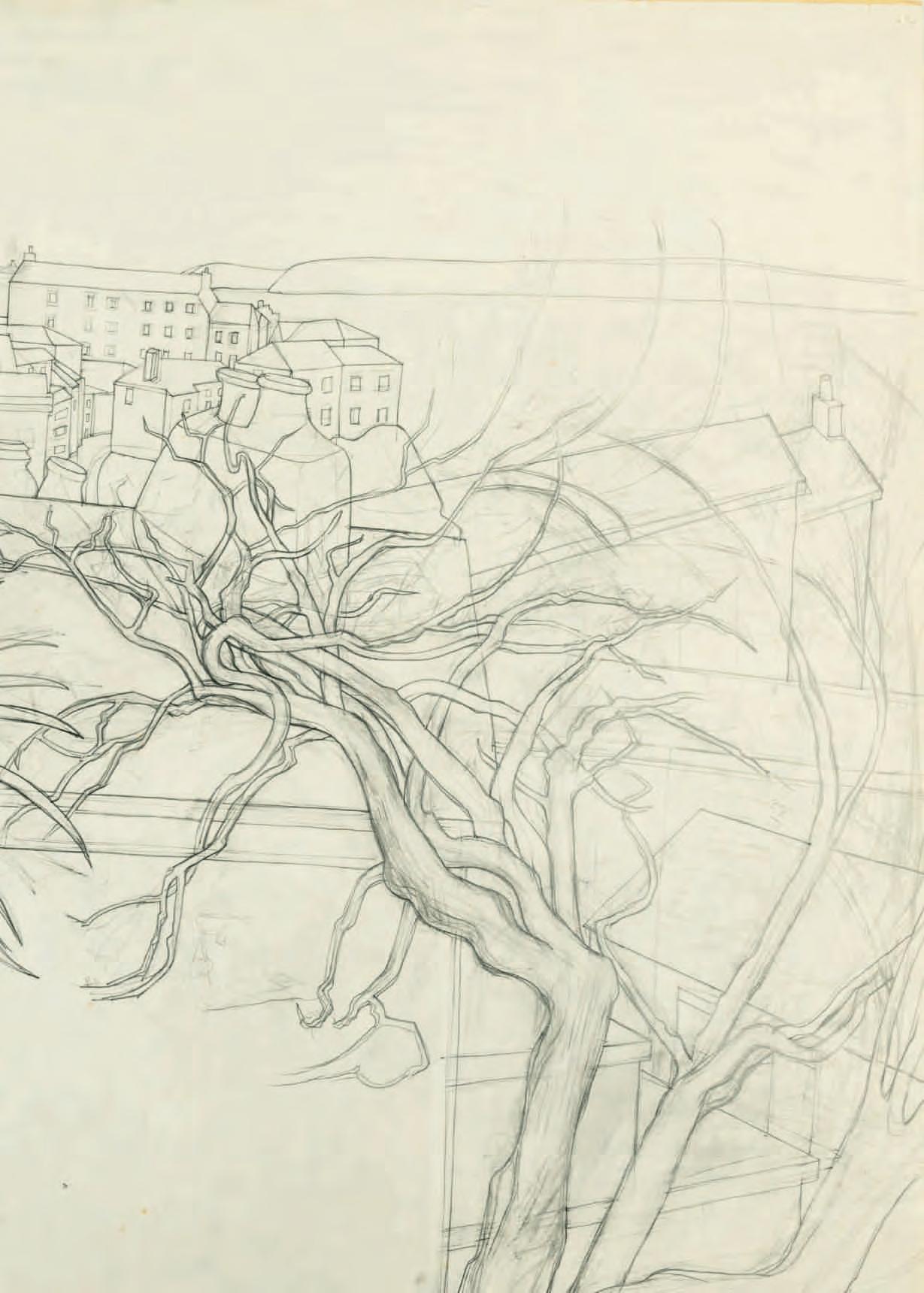

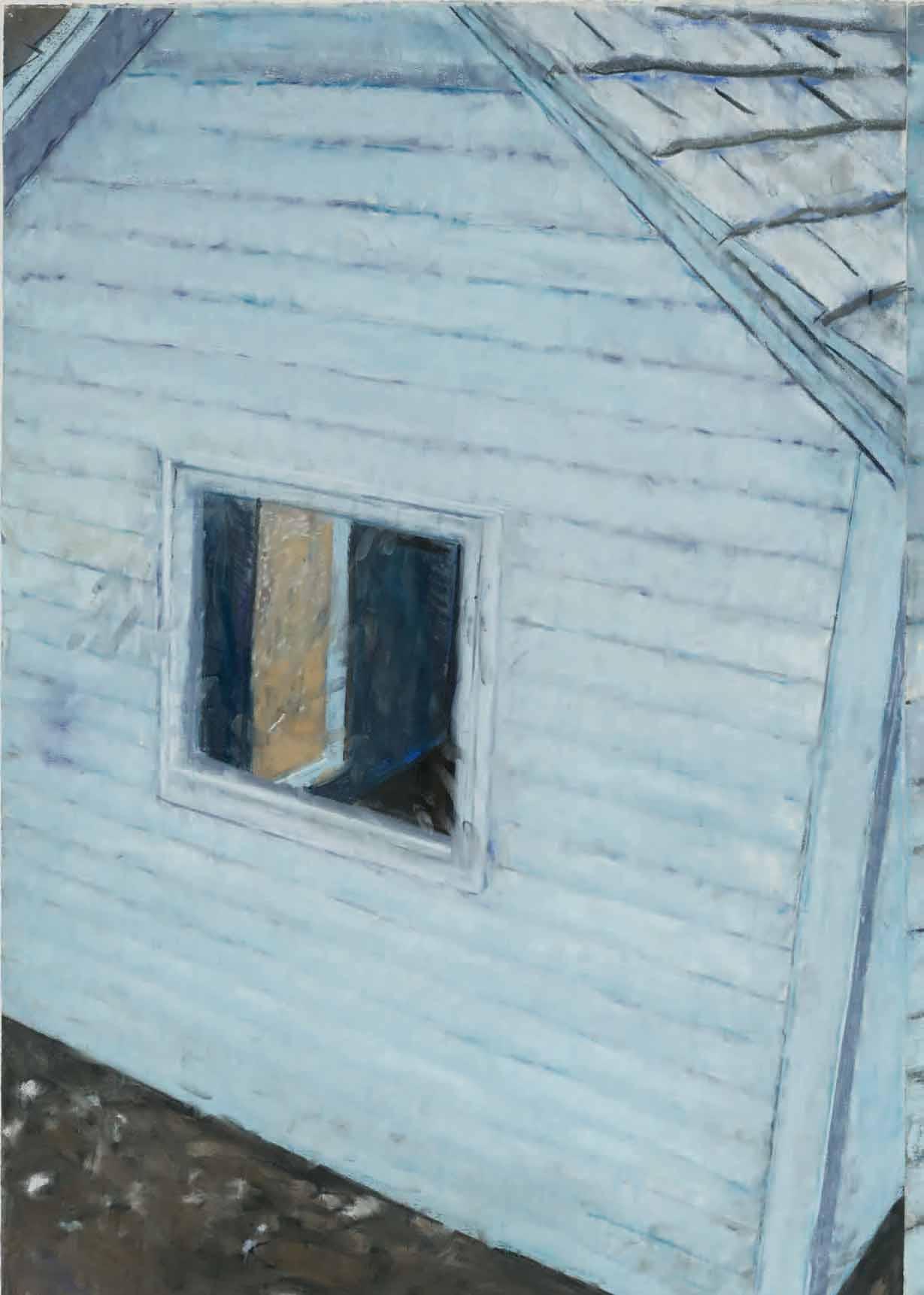

Wilhelmina Barns-Graham CBE (1912-2004)

Three Trees (St. Ives)

Cover:

Helen Frankenthaler (1928-2011)

Untitled (P91-20), 1991

No.25

Wilhelmina Barns-Graham CBE (1912-2004)

Three Trees (St. Ives)

‘There is a thing about beauty. Beauty is always associated with the male fantasy of what the female body is. I don’t think there is anything wrong with beauty. It’s just what women think is beautiful can be different. And there can be a beauty in individualism. If there is a wart or a scar, this can be beautiful, in a sense, when you paint it.’ (Jenny Saville, 1994)

I am grateful to my wife Laura for her support during the period that I was working on this catalogue. I am also greatly indebted to Team SOFA – Alesa Boyle, Eilidh McClafferty and Megan Corcoran Locke – for their assistance in every aspect of preparing this catalogue and the accompanying exhibition. At Healeys printers, I would like to thank in particular Sarah Ricks, as well as Alastair Frazer. The indefatigable Andrew Smith has photographed the works, and has been tireless in the fundamental task of colour-proofing the catalogue images against the original artworks. In addition, I would like to thank the following people for their help and advice in the preparation of this catalogue and the works included herein: Alexis Ashot, Deborah Bates, Eve Campbell, Cristina Colomar, Anne Connell, Savannah Downs, Rachel and Ben Elwes, Cheryl and Gino Franchi, Lavinia Harrington, Úrsula Romero and Jack Wakefield.

Stephen OngpinDimensions are given in millimetres and inches, with height before width. Unless otherwise noted, paper is white or whitish.

Please note that drawings are sold mounted but not framed. High-resolution digital images and framed images of the drawings are available on request.

All enquiries should be addressed to Stephen Ongpin at Stephen Ongpin Fine Art Ltd. 82 Park Street London W1K 6NH

Tel. [+44] (20) 7930-8813 or [+44] (7710) 328-627

e-mail: info@stephenongpinfineart.com website: www.stephenongpin.com

Watercolour, pen and brown ink and brown wash, over traces of a pencil underdrawing. Laid down. 190 x 273 mm. (7 1/2 x 10 3/4 in.) [sheet]

PROVENANCE: The estate of the artist, and by descent to her daughter, Merle Elspeth Taylor, Kirkcudbright; Her sale, Glasgow, Sotheby’s at the Charles Rennie Mackintosh Society, 21 June 1977 [lot unidentified]; Aitkin Dott & Son, Edinburgh; Private collection, Scotland.

Born in Dunbartonshire, Jessie Marion King studied at Glasgow University and the Glasgow School of Art in the early 1890s, concentrating on drawing and illustration. In 1898 she won a silver medal in the South Kensington National Art Competition, and also earned a travelling scholarship that allowed her to visit France and Italy. She was much admired for her highly individual illustrative style, characterized by a pen and ink technique akin to that of Aubrey Beardsley. In 1899 King joined the staff of the Glasgow School of Art, teaching book decoration and design. By 1902 her work was the subject of an article in The Studio magazine and she had won a gold medal in the category of book design at the International Exhibition of Decorative Art in Turin. King’s work in the years between 1898 and 1905 is characterized by fine detail and meticulous technique. Her compositions were sometimes heightened with gold, while many of her drawings and illustrations were executed on vellum. She was also active as a designer of textiles, jewellery, wallpaper, posters, wall tiles, theatrical costumes and book covers.

In 1908 King married a fellow artist, Ernest Archibald Taylor, and in 1911 the couple moved to Paris, where they established an art school known as the Shealing Atelier. Living in Montmartre, they became friendly with several artists, including Henri Matisse, Maurice Utrillo and Théophile-Alexandre Steinlen, as well as fellow Scots Samuel John Peploe and John Duncan Fergusson, and King’s work became stronger in colour and line. With the outbreak of the First World War, the couple moved back to Scotland, living near Kirkcudbright and setting up a summer school on Arran. In 1915 King drew colour illustrations for Oscar Wilde’s House of Pomegranates, and in later years produced landscape paintings and designs for batik fabrics. Although she died in relative obscurity in 1949, a reassessment of King’s oeuvre was begun in the 1970s, when commemorative exhibitions were held by the Scottish Arts Council and the Fine Art Society in London in 1971-1972, and at the National Library of Scotland in Edinburgh in 1978.

During her time in Paris, one of the projects King worked on was a commission for eighteen watercolour illustrations for a book about the bridges of the city. Another book, planned but never published, was to be devoted to views of Paris churches. As the scholar Colin White has noted, ‘Jessie drew two rather formal illustrations of the Sacré Coeur and St Germain des Prés and then decided to expand the idea to include any buildings in the city she found interesting. She began to go on sketching walks, starting with the district around their own apartment at the back of the Luxembourg Gardens and progressing in everwidening circles. She filled her sketchbooks with drawings in soft pencil which ranged from characters in the streets and architectural details of rooftops or shop fronts to such monuments as the Opéra, the Panthéon and the splendid Fontaine Carpeaux in the Jardins themselves...She also caught the feel of a more private Paris…She made each scene a personal vision and discarded even finished drawings if she felt dissatisfied with their balance or texture. Altogether she completed around 100 drawings.’1

This watercolour is likely to have been drawn on one of King’s sketching outings in Paris. While three of her drawings were included in Paris Past and Present, a book written by her husband that appeared in 1915, most of her drawings of Paris were never published or reproduced.

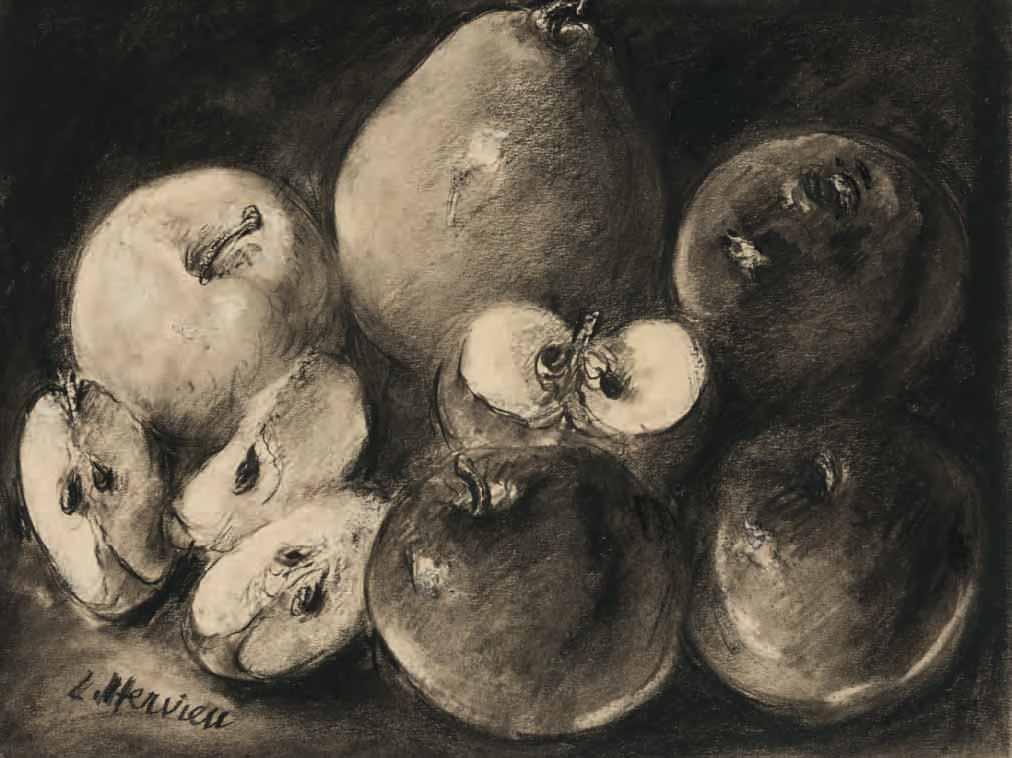

Still Life with Apples and a Pear

Charcoal and stumped black chalk. Signed L. Hervieu in charcoal at the lower left. 252 x 325 mm. (9 7/8 x 12 3/4 in.)

PROVENANCE: Jean-Claude Barrie, the Barrie-Chevalier collection, Saint-Amans-des-Cots (with the collection stamp, not in Lugt, on the old backing board).

An extraordinary figure in the artistic and literary circles of Paris in the first half of the 20th century, Louise-Jeanne-Aimée Hervieu took up painting around 1905, having studied with Lucien Simon, André Dauchez and René Ménard. She participated in the Salon des Indépendants in Paris, and in 1910 had a one-woman exhibition at the Galerie Eugène Blot in Paris. After this, however, she abandoned painting at the insistence of her parents, although she continued to make charcoal drawings and pastels – often of female nudes, still lives and interior scenes – as well as lithographs. Hervieu soon came to the attention of the critic Félix Fénéon, who in 1917 organized the first of several exhibitions of her drawings at the Galerie Bernheim-Jeune. Fond of intense chiaroscuro techniques, she achieved remarkable effects of mood and mystery in her work, often using a razor blade to rub and scratch the surface of her drawings to heighten their visual impact. She became friendly with such artists as Félix Vallotton, Pierre Bonnard and Edouard Vuillard, and provided illustrations for several books, including Charles Baudelaire’s Les fleurs du mal in 1920 and Le spleen de Paris in 1922.

Born with congenital syphilis and always in very poor health, Hervieu was, by her forties, confined to her room and had largely withdrawn from the world. As a result of chronic meningitis, her eyesight gradually deteriorated, and by the early 1920s she had abandoned working in colour. By 1927 she was almost completely blind and had stopped drawing altogether; indeed, the catalogue of her retrospective exhibition at Bernheim-Jeune that year was prefaced by a statement intended by the artist as a sort of artistic ‘farewell’. Hervieu had by then turned to writing, and in 1925 her book L’âme du cirque was published, accompanied by illustrations by Bonnard, Maurice Denis, Picasso, Georges Rouault and André Lhote. In 1936 her novel Sangs won the Prix Fémina; this was followed by Le crime, published in 1937, Le malade vous parle in 1943 and La rose de sang in 1953.

The 20th century art historian and critic Claude Roger-Marx, a close friend and admirer of the artist, published his Éloge de Louise Hervieu in 1953, a year before her death. In it he described her monochromatic drawings, which he likened to those of Odilon Redon and Georges Seurat: ‘Dark curtains open and we enter a world where Love and Death speak in hushed tones.’1 The following year, in his book Maîtres du XIXe siècle et du XXe, he added that, ‘Drawing, for Louise Hervieu, is really about taking possession of the world by giving the word its complete physicality.’2 Roger-Marx also wrote the preface to a posthumous exhibition of Hervieu’s drawings and paintings at the Galerie Marie L. André in Paris in 1969.

In 1978 Roger-Marx bequeathed a very large drawing by Hervieu of seashells and a pearl necklace to the Louvre3, which owns two further drawings by the artist. Other drawings by Louise Hervieu are in the collections of the Musée National d’Art Moderne in Paris and the museums of Bordeaux, Caen and Nantes.

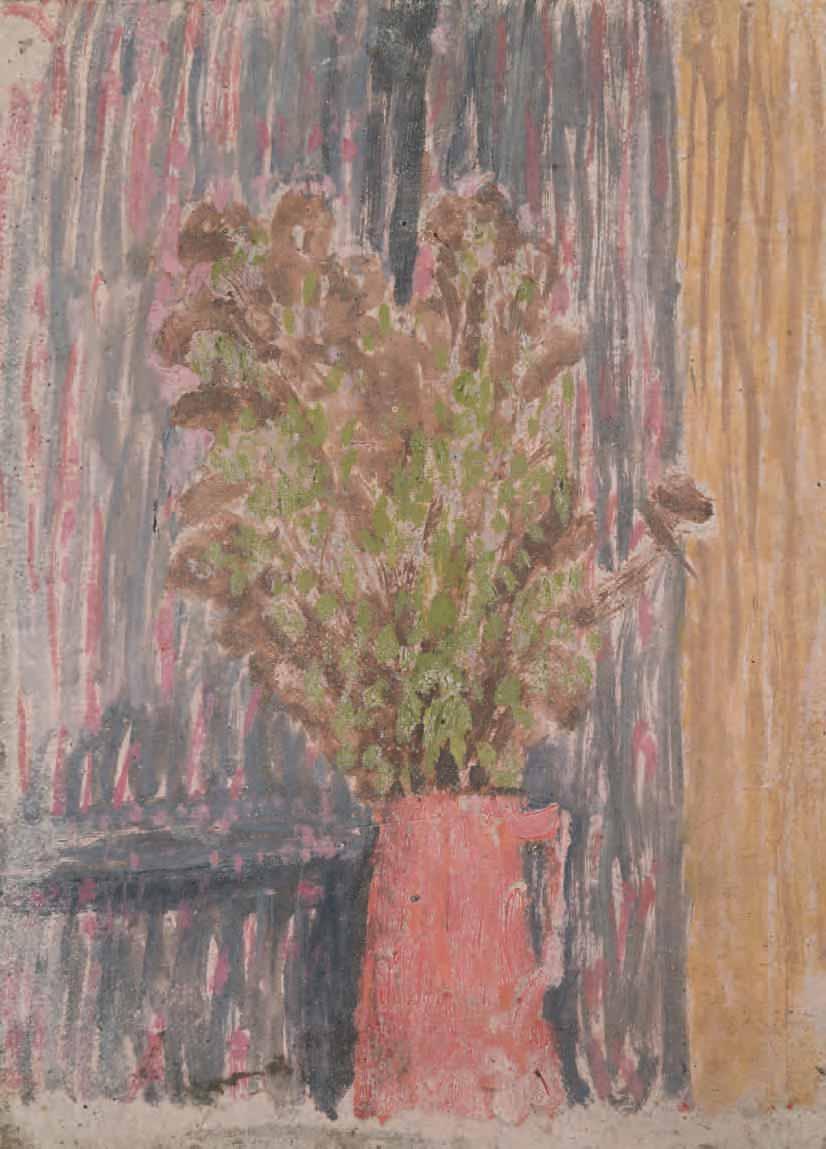

Flowers in a Pink Jug

Gouache on buff paper. 191 x 145 mm. (7 1/2 x 5 3/4 in.)

PROVENANCE: The estate of the artist; Browse and Darby, London; Private collection, London.

Born in Wales, Gwendolyn Mary John drew from an early age, and in 1895 began a course of study at the Slade School of Fine Art in London, where her younger brother Augustus had enrolled the previous year. After leaving the Slade in 1898, Gwen spent six months in Paris, studying at James McNeill Whistler’s short-lived school of painting, the Académie Carmen. Back in London, she exhibited twice yearly at the New English Art Club between 1900 and 1902, and also showed three paintings as part of an exhibition of Augustus’s work in London in 1903. The following year, at the age of twenty-seven, John settled in Montparnasse in Paris, where she earned a living by modelling for artists. Among these was the renowned sculptor Auguste Rodin, with whom John had a long and intense love affair that lasted some ten years, although the true nature of their relationship was known only to a handful of the sculptor’s close friends.

John lived in France for the remainder of her career, over the course of which she produced no more than two hundred paintings. Her subjects were mainly portraits of solitary women and girls, as well as landscapes, interiors and still life compositions, while following her conversion to Roman Catholicism in 1913, paintings and small-scale gouaches of figures at Mass also began to appear in her work. In 1911 the artist moved to Meudon, in the southwestern suburbs of Paris and near Rodin’s country house. By this time she had been introduced to John Quinn, a prominent American collector of modern art who was to become her most significant patron. From 1912 onwards Quinn sent her a yearly stipend, and between 1911 and his death in 1924 acquired almost every painting she wished to sell1

Throughout her career John worked mostly in isolation, having chosen to withdraw from both society and artistic circles, first in London and later in Paris. (As one scholar has noted, ‘She cultivated privacy, and a sense of privacy is one of the dominant feelings of her painting...she always worked in solitude, and took only the little she wanted from the great years of the modern movement in the arts.’2) Although John continued to show at the NEAC in London and also exhibited at the Salon des Tuileries and the Salon d’Automne in Paris, she seems to have been largely unconcerned with making her work better known. Only one solo exhibition was held in her lifetime, at the New Chenil Galleries in London in 1926, which included over forty paintings and watercolours and several albums of drawings. By around 1930, however, John had largely ceased to paint3. Her last datable work was done in 1933, and she seems to have stopped working almost entirely for the last five or six years of her life.

This small still-life may likely be dated to the final decade of Gwen John’s career, when she produced a number of freely-painted gouaches of flowers in a jug. As the artist’s biographer has noted of this period in the early 1930s, ‘Flower studies…[were] repeated time and again and growing smaller. It was as if painting had become for Gwen John what saying the rosary is to others.’4 A closely related composition, of identical dimensions, was at one time with the Browse and Darby Gallery in London5

Two Houses in a Landscape

Gouache on buff paper. Stamped with the estate stamp Gwen John at the lower left. 160 x 123 mm. (6 1/4 x 4 7/8 in.)

PROVENANCE: The estate of the artist; Davis & Langdale Company, Inc., New York; Private collection, New York; Anonymous sale, Hillsborough, NC, Leland Little Auctions, 10 June 2015, lot 532; Jill Newhouse, New York, in 2019; Anonymous sale, Chicago, Hindman, 10 May 2022, lot 49; Private collection, London.

EXHIBITED: New York, Davis and Langdale Company, Inc., Gwen John 1876-1939: Paintings, Watercolors, Drawings, 1993, no.43 (as Cottages Behind a Wall, Meudon).

Although over the course of her career Gwen John was always overshadowed by her younger brother Augustus John, a larger-than-life character who enjoyed success and notoriety, in recent years her critical reputation has come to surpass his, and she has been celebrated as one of the most significant British artists of the 20th century. (Indeed, this is something Augustus himself had foretold, once stating that ‘In fifty years’ time I will be known as the brother of Gwen John.’) At Gwen John’s death in 1939, at the age of sixty-three, the vast majority of her output remained in her ramshackle studio in Meudon, the village just southwest of Paris that she had moved to nearly thirty years earlier. The following year an exhibition of paintings and drawings from the artist’s estate, which had been inherited by her nephew Edwin John, was held under the auspices of the Matthiesen Gallery in London; this was followed in 1947 by a large retrospective exhibition at the same gallery and later at the Arts Council.

John’s beautiful, enigmatic and delicately painted intimist works are almost always modest in scale and subdued in tonality. She painted very slowly and never signed or dated her work, so establishing a chronology for her oeuvre is not always straightforward. John also often repeated a composition, sometimes producing several variants of a particularly successful painting. A late work by the artist, datable to the early 1930s, this small, impressionistic landscape is likely to have been painted at Meudon, where she had lived and worked since 1911. Although always a person who preferred solitude, by the beginning of the 1930s John had become more and more reclusive, and was often in poor health. She had largely stopped painting in oils by this time, although she continued to draw. As the scholar Cecily Langdale has noted of John’s late works, ‘The last colored works on paper are executed in gouache…, in a combination of gouache and watercolour…, or even occasionally in a mixture of gouache and oil… As opaque as any oil painting, they were done about the time she ceased to use oil, and may have been a substitute for her work in that medium. Earlier, her painting and drawing were separate areas of endeavor, with little specific relationship between them. Several of Gwen John’s final works epitomize the convergence of those hitherto distinct areas.’1

A closely related composition of a Cottage Behind a Wall is in a private collection2, while two others were formerly with the Browse and Darby Gallery in London3. All of these may be related to a sheet of compositional sketches by John, today in the collection of the National Library of Wales in Aberystwyth4, which includes seven similar sketches of houses behind a wall. The setting is probably the rue Terre Neuve in Meudon, the same street where the artist lived until 1932.

The Moroccan Bride

Black chalk on paper; a page from a sketchbook. A slight sketch of a standing youth drawn in pencil on the verso. Numbered 403 in pencil at the bottom and (8) in pencil on the verso. 300 x 229 mm. (11 3/4 x 9 in.) [sheet]

PROVENANCE: By descent in the family of the artist.

The daughter and pupil of the painter Norman Garstin, Mary Dochie Alethea Garstin began painting seriously at the age of sixteen, and two years later had a work accepted by the Royal Academy Summer exhibition. She often accompanied her father when he undertook the summer schools of painting that he held almost every year in northern France between 1899 and 1927. The Garstin family settled in Cornwall, where Alethea lived for most of her life. Her first gallery exhibitions were joint shows with her father, in London in 1921 and 1924, and she had her first solo gallery exhibition in 1940. Garstin travelled throughout Britain, often using her small red Morris Eight car as a mobile studio, and also made trips to France, Belgium, Italy, Morocco, Kenya, Tanzania and Australia. She remained active well into old age, with her final painting trip abroad undertaken at the age of eighty-two. In 1978, the year of her death, a large retrospective exhibition of work by both Norman and Alethea Garstin was held in St. Ives, Dublin and London.

Alethea Garstin’s paintings, usually on a small and intimate scale, are characterized by a lightness of touch and a freedom of execution. They have been likened to the intimiste paintings of Edouard Vuillard by the artist Patrick Heron, who championed her work. Writing just before her death, Heron noted, ‘I say Vuillard in view of the basic means employed by Alethea throughout sixty years of painting small, delectable, ever-different pictures…I have taken Vuillard as a peg – and if there are for some time to come those who think the comparison with such a master is simply a gratuitous gift to Alethea Garstin… – I shall have no reply, save only to invite contemplation of her output as prolonged and intent as that devoted to her by her smallish band of intense admirers.’1 Paintings by Garstin are today in the Bristol Museum and Art Gallery and the Royal West of England Academy in Bristol, the Plymouth City Museum and Art Gallery, the National Trust and the Government Art Collection.

This chalk drawing is a preparatory study for the painting The Moroccan Bride (fig.1), formerly in the possession of the artist’s descendants and sold at auction in 20142. Garstin first visited Tangier in 1928 and returned there each year for the next three years3.

Watercolour over a pencil underdrawing. Inscribed in red ink at the top. Signed in brown ink at the lower right. 280 x 203 mm. (11 x 8 in.)

The Ukrainian-born artist Lidia Zholtkevich was the daughter of the Revolutionary sculptor Alexander Zholtkevich, who lived with his family in Paris between 1908 and 1917. The young Lidia began her artistic training in Paris, first exhibiting her drawings in 1914. The following year she entered the private Académie Colarossi, which was known for accepting female students and allowing them to conduct life drawing from the posed male nude. In 1917 Zholtkevich returned to Russia, and later enrolled at the Vkhutemas art and technical school in Moscow. With a curriculum similar to that of the Bauhaus, Vkhutemas (an acronym for Vysshiye Khudozhestvenno-Tekhnicheskiye Masterskiye, or ‘Higher Art and Technical Studios’) was established in Moscow in 1920 as ‘a specialized institution that would prepare qualified master artists, professors, and directors to work in both industry and higher education. It aimed to fulfill the state’s goals for efficiency and production by linking art with politics.’1

Zholtkevich entered Vkhutemas shortly after Alexander Rodchenko had joined the faculty, at a time when he was moving away from abstract painting towards the Russian avant-garde movement to be known as Constructivism, characterised by bold colours, simple typefaces, and geometric shapes and compositions. The professors of Vkhutemas, mainly leftist artists, led the development of agitational art and propaganda, with the first works of the movement appearing soon after the Revolution of 19172. In 1925 Zholtkevich married the graphic artist, printmaker and illustrator Georgy Alexandrovich Echeistov, and completed her studies in 1929, graduating with a speciality in woodcut prints. Shortly thereafter, between 1930 and 1931, she accompanied the Belarussian painter Meir Axelrod to Crimea to create an artistic record of agricultural achievements in collectivisation. Zholtkevich had begun exhibiting with the Association of Graphic Artists at the House of Printing during her time at Vkhutemas, and in the 1930s received a number of official commissions. Her most substantial work for the government were designs for silk-screened panels for the Soviet pavilions at the International Exhibitions in Paris in 1937 and New York in 1939.

This drawing is likely to date from the 1930s, and may possibly be related to Zholtkevich’s work on behalf of the People’s Commissariat for Food Industry for the Russian pavilion at the 1937 Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques dans la Vie Moderne in Paris. The Soviet pavilion, awarded a gold medal by the organizers, commemorated the twentieth anniversary of the 1917 October Revolution. The front of the pavilion was dominated by a monumental, twenty-four metre high statue of The Worker and the Collective Farm Woman by Vera Mukhina, while the interior contained several halls featuring industrial models and social-realist murals3

Adapting the visual language of the revolutionary movement of the 1920s, the present sheet – drawn with two bold colours of black and red, highlighted by a striking teal – depicts a female worker, with the prominent text translating as ‘Voice of the Sugar Factory Worker’. She is presented in a monumental stance, and wears the red headscarf of a supporter of Socialism. The image likely refers to a telegram sent in September 1917 by the workers of the Georgievsky Company Sugar Factory in Petrograd (today Saint Petersburg) to the Russian Provisional Government in the city, condemning the possibility of a corrupt military dictatorship while underscoring the workers’ stance as worthy and principled Socialists. In the telegram, the workers of the Georgievsky Factory declared their full support of the Government: ‘we have utter confidence that only a unitary power in the person of the Provisional Government can save the homeland and the gains of the revolution, and that it will not allow a return to the past and thus assured we continue each in his own place to work calmly and with full energy for the good of the homeland.’4

7 A Derelict Farmhouse

Watercolour and gouache, with pen and brown ink and brown wash. Signed and dated I. Gerhardt / 1948 in brown ink at the lower right.

176 x 266 mm. (6 7/8 x 10 1/2 in.)

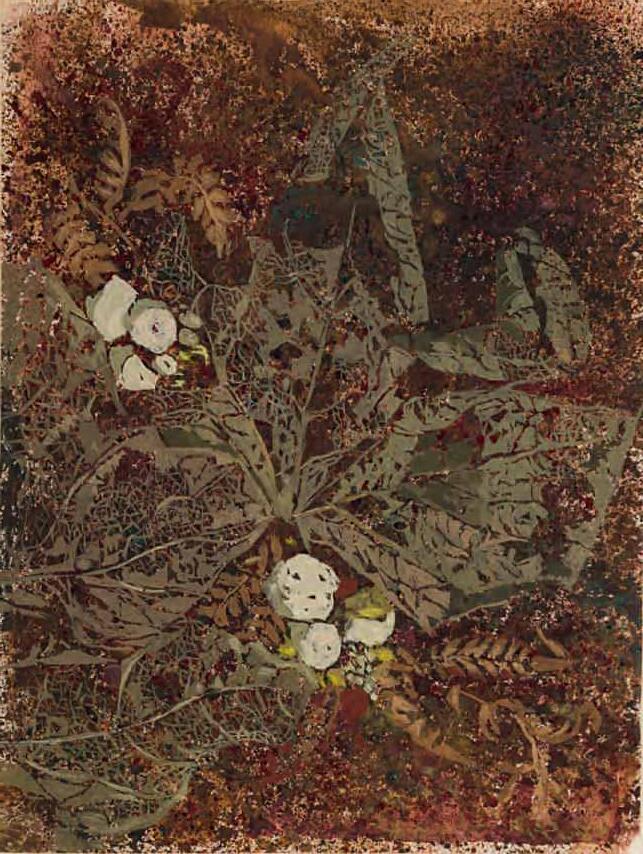

8 A Study of Foliage with White Berries

Watercolour and gouache.

221 x 167 mm. (8 3/4 x 6 5/8 in.)

9 Landscape with a Bridge over a Stream

Watercolour and gouache, with pen and brown ink and brown wash, on pale grey paper. A study of a haystack(?) in pencil on the verso.

192 x 292 mm. (7 5/8 x 11 1/2 in.)

Almost nothing is known of the German artist Ingrid Gerhardt. She studied at the free art school established by the painter Jo Strahn in Düsseldorf in the 1940s and lived for much of her later life in France, in the département of Ille-et-Vilaine in Brittany. That she was also active as a printmaker is evidenced by a woodcut of a puppet-master, published in the newsletter of a German amateur theatrical society in 19551.

9.

8.

9.

8.

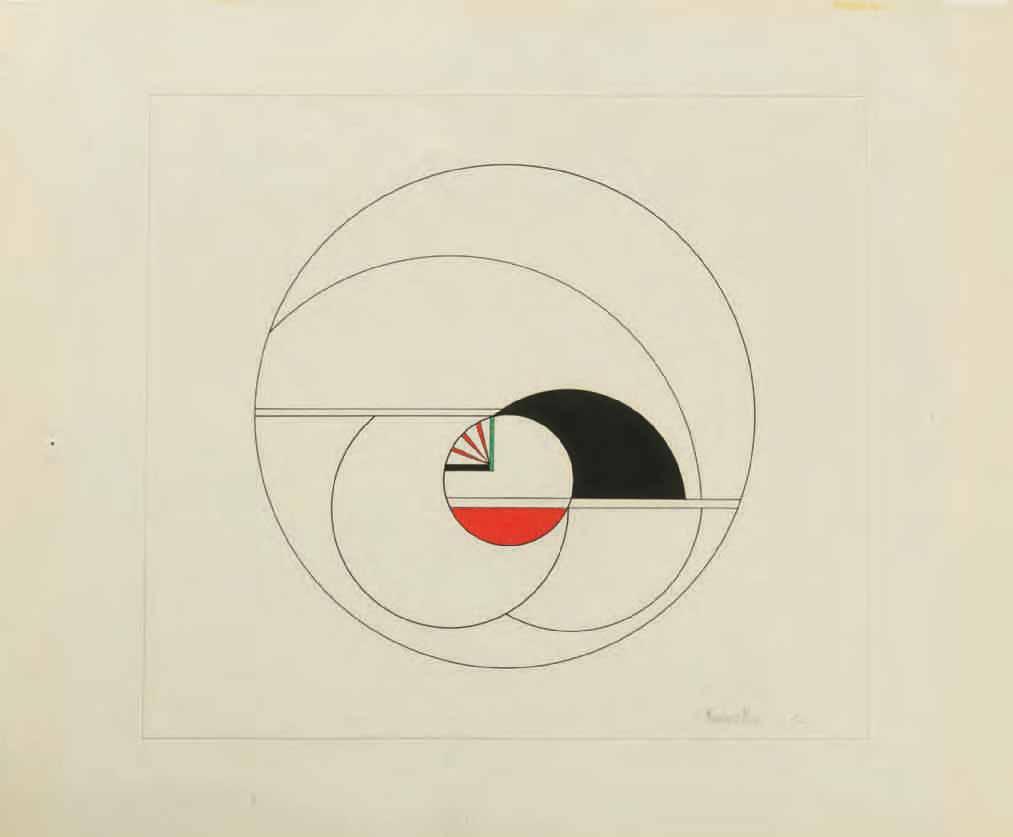

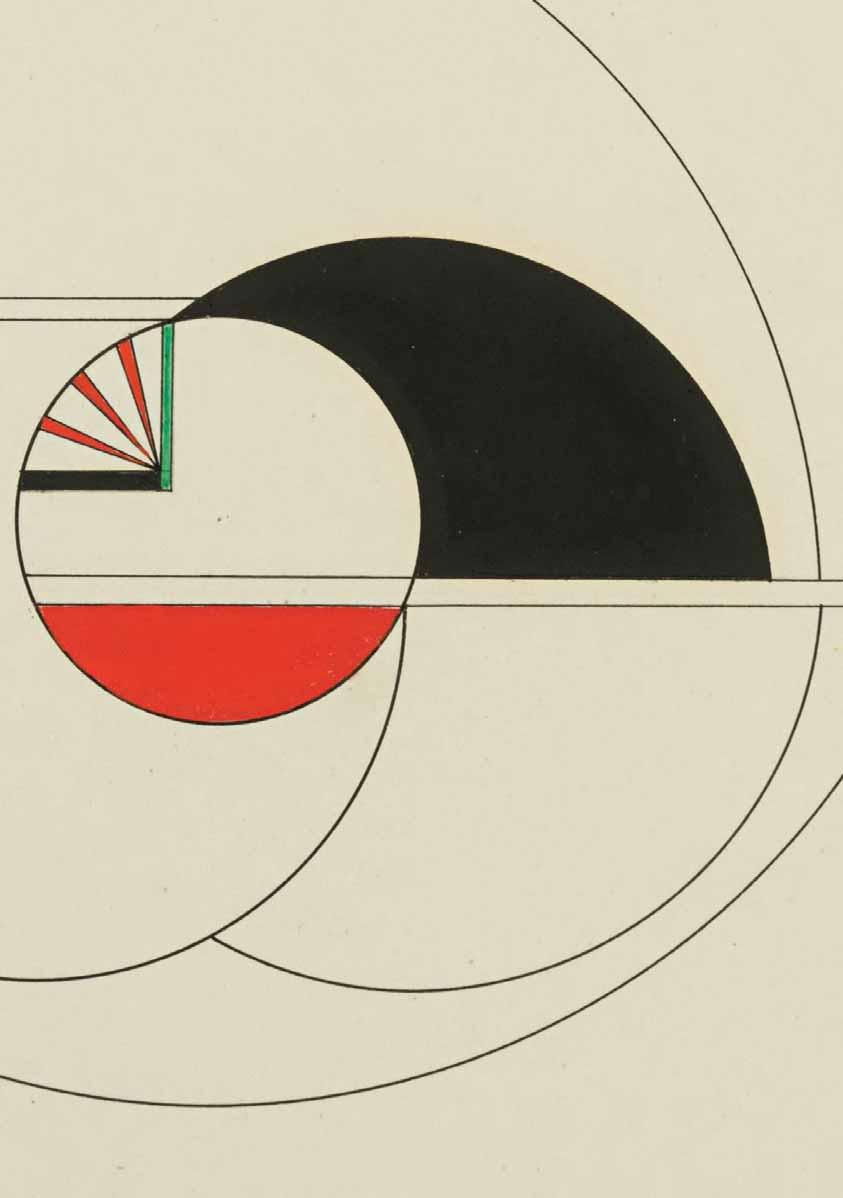

MARLOW MOSS

London 1889-1958 Penzance

Untitled, 1950

Black ink, pencil and tempera, with a framing line in pencil, on stamped Bristol board. Signed and dated Marlow Moss 50. in pencil at the lower right. Illegibly inscribed and numbered C 17 in pencil on the verso.

241 x 271 mm. (9 1/2 x 10 3/4 in.) [image]

318 x 384 mm. (12 1/2 x 15 1/8 in.) [sheet]

PROVENANCE: Carus Gallery, New York, in 1979; Sid Deutsch Gallery, New York; Private collection, Virginia.

LITERATURE: Lucy Howarth, Marlow Moss (1889-1958), unpublished Ph.D thesis, University of Plymouth, 2008, Vol.I, p.288, note 182, Vol.II [Catalogue raisonné], unpaginated, no. Wop 25 (as location unknown, and incorrectly dated 1949).

EXHIBITED, New York, Carus Gallery, Marlow Moss 1890-1958, 1979, no.16.

A British Constructivist artist and a significant figure in the development of non-figurative art in Europe, Marjorie Jewel Moss was born in Kilburn in north London. She was in her late twenties when she began studying at the St. John’s Wood Art School, leaving after a year to enrol at the Slade School of Fine Art in 1917. She remained there until 1919, when, at the age of thirty, she seems to have experienced a mental breakdown. Sometime around 1920 she adopted the gender-neutral first name ‘Marlow’, and also began habitually dressing as a man, sporting closely-cropped, pomaded hair and wearing a cravat, hunting jacket and jodhpurs; as she is said to have later explained, ‘I destroyed my old personality and created a new one.’.

In 1927, at the relatively advanced age of thirty-eight, Moss moved to Paris and studied under Fernand Léger and Amedée Ozenfant at their private art school, the Académie Moderne. It was at around this time that she met her lifelong partner, the Dutch writer Antoinette (‘Netty’) Nijhoff-Wind. Moss was already working in a non-figurative manner when she encountered in Paris the work of the Dutch painter Piet Mondrian, whose artistic theory of Neoplasticism – a purified, rational abstract art of straight lines and simple shapes, combined with black, white and primary colours – had led to the foundation of the De Stijl group in 1917. Moss immediately fell under the influence of the De Stijl aesthetic and produced her first Neo-Plasticist painting in 1929. The following year she introduced close parallel lines (a socalled ‘double line’) into her abstract compositions; an innovation that brought her to the immediate attention of Mondrian. At his suggestion Moss became, in 1931, one of the founding members of the Abstraction-Création group, alongside Jean Arp, Jean Hélion, Naum Gabo, Auguste Herbin, Kurt Schwitters and the De Stijl artists Mondrian, Theo van Doesburg and Georges Vantongerloo, who became a close friend of Moss. Abstraction-Création was dedicated to the promotion of non-figurative art through exhibitions and publications, and Moss was the only British artist, and the only woman, whose works were included in all five of the group’s annual cahiers, the last of which appeared in 1936.

Between 1927 and 1940 Moss lived between Paris and Normandy. Her long friendship with Mondrian, although never warm – in his letters to her, Mondrian always addressed her as ‘Miss Moss’ – lasted throughout her time in France. The two artists looked closely at each other’s work, and Mondrian came to adopt the double line in his own paintings, although it was claimed by Vantongerloo that he did so without crediting Moss for her initial inspiration. As Nijhoff noted of Moss, ‘She understood Mondrian very well and vice versa. They were very well matched…a pair of extraordinary lone wolves.’1

Given her identity as a cross-dressing Jewish artist, it was not surprising that Moss felt compelled to return to Britain in 1940, with the outbreak of the Second World War in Europe, and in 1941 she settled in the village of Lamorna on the far west coast of Cornwall. She worked there in near-isolation,

despite initially reaching out to Barbara Hepworth and Ben Nicholson, who lived not far away at St. Ives, but who seem to have rejected her overtures. Moss studied architecture at the Penzance School of Art and continued to live a somewhat reclusive life in Cornwall. Tragically, the vast majority of her work from before 1940 was lost when her former home and studio in the village of Gauciel in Normandy was destroyed during a bombing raid in 1944. As a result, ‘All that remained from this early period were works no longer in her possession and photographs of works, which she had sent to art associations and interested parties for publication purposes or in the hope of being able to participate in exhibitions.’2 Apart from her Constructivist paintings, based on mathematical principles and with a colour palette limited to black, white, blue, red and yellow, Moss also produced a number of freestanding sculptures and white painted relief works in the 1940s and 1950s. As Nijhoff has quoted the artist: ‘I am no painter, I don’t see form, I only see space, movement and light.’3

After the war, Nijhoff re-joined Moss in Cornwall, though the couple returned several times to Europe, visiting Paris and Holland. The last decade of Moss’s career was a very productive one, perhaps the result of her attempt to make up for the loss of almost her entire earlier output during the war. She exhibited at the Salon des Réalités Nouvelles at the Galerie Charpentier in Paris in 1946 and 1950, and had solo exhibitions at the Hanover Gallery in London in 1953 and in 1958, a few months before her death from stomach cancer. Moss bequeathed her entire estate to Nijhoff’s son, and in 1962 a major retrospective exhibition of her work was mounted at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam. Moss’s home in Lamorna was taken over by another radical queer artist, the painter known as Gluck, whom Moss may have known.

Until relatively recently, Marlow Moss has remained a very obscure figure, particularly in her native country; indeed, only a handful of her works are to be found in public collections in Britain. (The artist was much better known in Holland, where exhibitions of her work were held in the 1960s, 1970s and 1990s.) As the scholar Lucy Howarth has noted, ‘Moss disrupted and subverted her surrounding narratives; she was a British artist in Paris and a European in Cornwall; she was a female artist amongst men, but can be regarded as a pseudo-man amongst female artists. This resistance to categorisation is a large factor in Moss’s obscurity; she is omitted from the histories because she does not fit in.’4 Paintings and sculptures by Moss are today in the collections of the Tate in London, the Henry Moore Institute in Leeds, the Israel Museum in Jerusalem and the Museum of Modern Art in New York, as well as in several Dutch museums, notably the Rijksmuseum and the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, the Gemeentemuseum in The Hague and the Kröller-Müller Museum in Otterlo.

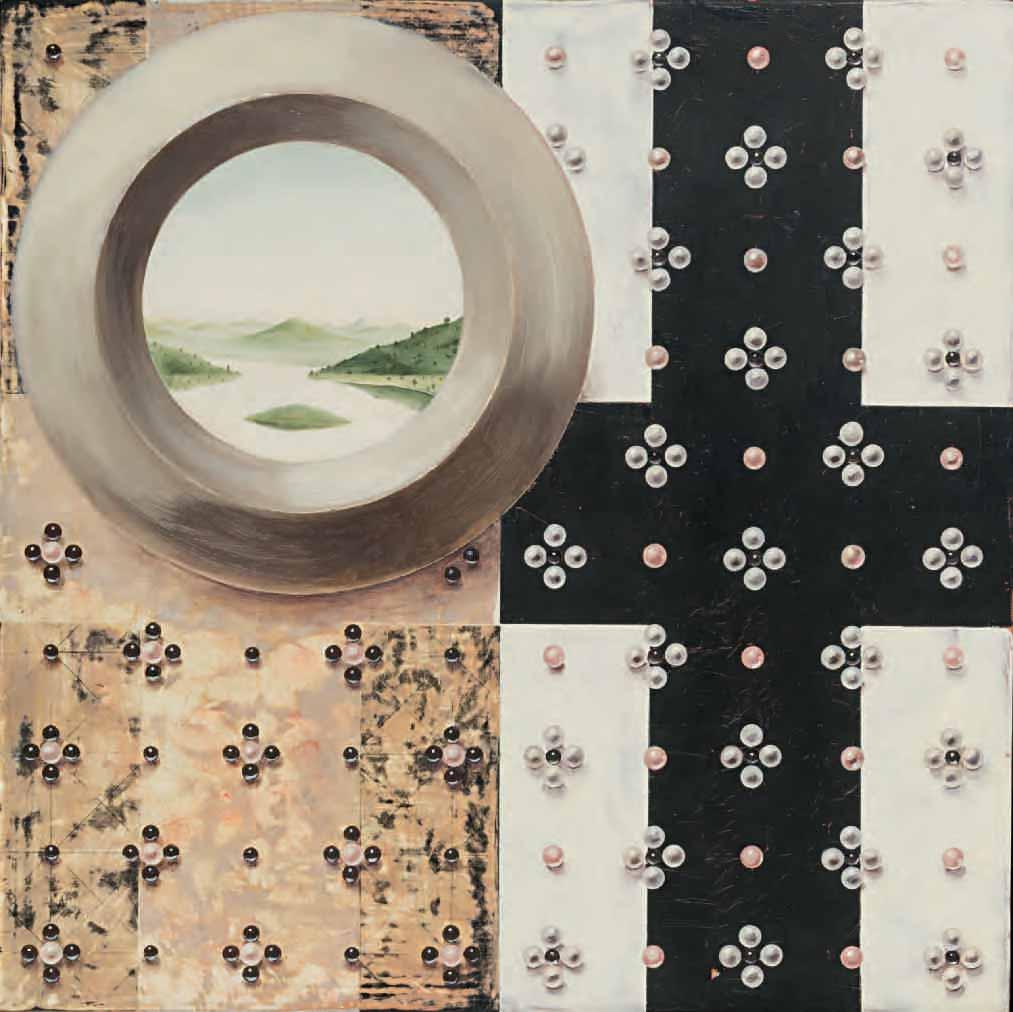

Moss’s work as a painter and sculptor was founded on a rigorous approach to drawing. As Howarth has described the artist’s working process, ‘A work began with thumbnail sketches, in watercolour and gouache, dabs of colour, tentative and playful. From the initial sketches Moss then progressed to a working drawing, finding the mathematical relationships between the areas. In contrast to the freedom of the initial sketch, the working drawings are precise, executed with a sharp pencil, ruler and compass. These drawings are edged with notes and calculations in pencil. Often she collaged on coloured paper, further refining the divisions. Once the complete composition was arrived at, the drawing was transferred to the prepared canvas. The final painting was then executed; with layer after layer of thin translucent paint Moss gradually arrived at the desired intensity of colour, a concrete realisation of her a priori scheme.’5 Apart from two drawings in the Musée de Grenoble and another two sheets only recently acquired by the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam6, however, almost none of Moss’s works on paper are in public collections today.

The present sheet may be grouped with a small number of independent works on paper by Moss that have been aptly described by Howarth as ‘optical diagrams’7. As she further notes, drawings of this type – of which she lists just twenty-six examples in her catalogue raisonné of the artist’s work8 – ‘are the most undocumented section of Moss’s oeuvre [and] have received scant attention in Moss scholarship... They are distinctly complete works, as opposed to the preliminary sketches and working drawings that were made in preparation for paintings…and they represent perhaps the most overtly experimental section of Moss’s output, reminiscent as they are of Bauhaus student exercises.’9 The use of the colour green in this drawing exemplifies a feature that is only found in a handful of Moss’s autonomous works on paper, since in her painted work the artist adhered to a strict use of only the primary colours of blue, red and yellow, along with black and white.

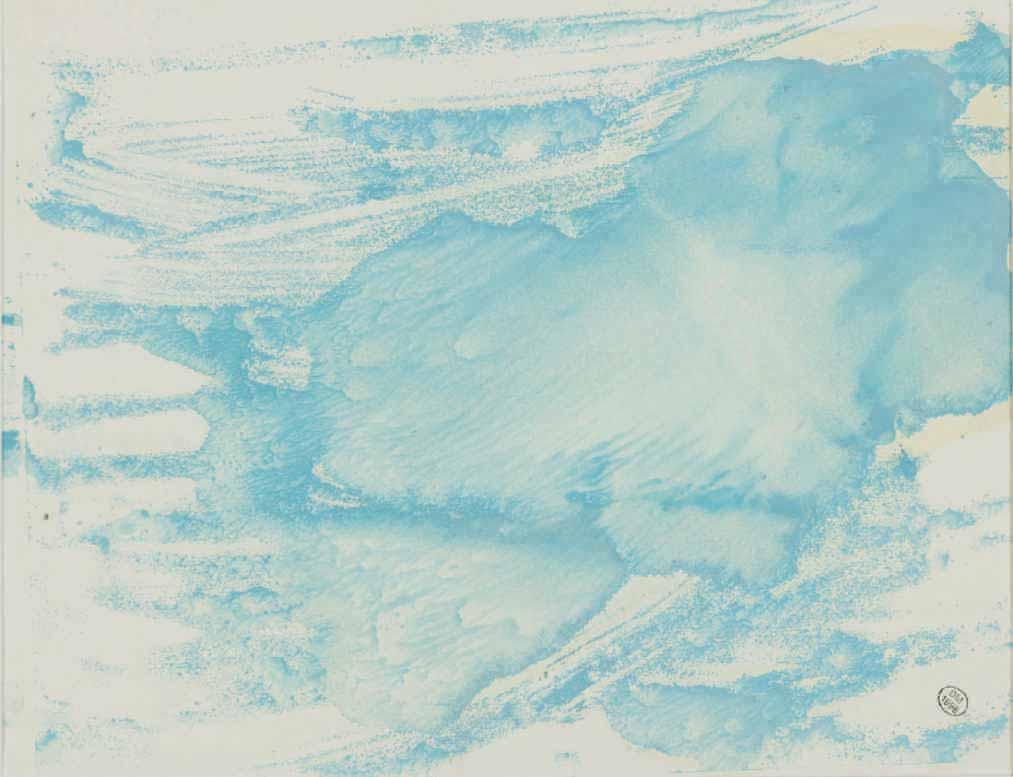

Untitled, c.1959

Watercolour. Inscribed LD - PW. 188 in pencil on the verso. 165 x 290 mm. (6 1/2 x 11 3/8 in.)

PROVENANCE: The estate of the artist; Private collection, Maine.

Born in south-eastern Virginia, Lynne Mapp Drexler studied at the Richmond School of Art, graduating with a degree in Fine Art in 1949. After two trips to Europe in the early 1950s, during which she spent a considerable amount of time in London, she began to study painting seriously. In late 1955 she decided to move to New York City to study with the German-born painter and renowned art teacher Hans Hofmann, enrolling in his school in February 1956 and also earning a scholarship to his summer class in Provincetown, Massachusetts, in 1957. (Among his students, Hofmann counted several of the most significant women artists of the period, including Nell Blaine, Ray Eames, Marisol Escobar, Helen Frankenthaler, Jane Freilicher, Lee Krasner and Mercedes Matter. Joan Mitchell attended one class at Hofmann’s school but never returned, apparently explaining that, ‘I couldn’t understand a word he said so I left, terrified.’) Hofmann taught Drexler to focus on painting in terms of colour, form and space, and his theories about musical analogies in chromatic scales resonated with the younger artist.

When Hofmann closed his New York school, and at his recommendation, Drexler began studying with the Abstract Expressionist painter Robert Motherwell at Hunter College. Both Hofmann and Motherwell strongly supported and encouraged the artist in her work, whose qualities they readily recognized. (However, when she told Motherwell that she was thinking of becoming a teacher herself, he is said to have replied, ‘I’ll flunk you out of here before I see you go to teach. You’re too good a painter.’) As a disciple of both Hofmann and Motherwell, Drexler became associated with the second generation of Abstract Expressionist painters. By the late 1950s she had come of age as an artist, and her first solo exhibition of eleven brightly-coloured abstract paintings was held at the artist’s cooperative Tanager Gallery in New York in 1961, although none of the works sold.

The following year Drexler married the abstract painter John Hultberg, whose career was much more established, since he had gained the support of the gallerist Martha Jackson. In 1961, with Jackson’s help, Hultberg had bought a summer house on Monhegan Island, several miles off the coast of Maine, and he and Drexler spent the summer of 1963 there. They returned to Monhegan almost every year thereafter, and much of Drexler’s later work was inspired by the landscape of this small and remote island. The couple spent some of the next few years on the move, usually due to Hultberg’s teaching commitments, and lived briefly in Mexico before settling in San Francisco. It was in California that Drexler produced her first lithographs, at the Tamarind Lithography Workshop in Los Angeles in 1963.

In 1965 Drexler had her second solo exhibition at a gallery in Los Angeles, which was well reviewed by local critics. (The art critic of the Los Angeles Times noted of Drexler that ‘the artist impresses by her technical virtuosity and her distinctively personal, highly exuberant poetry. Essentially a colorist to whom texture is nearly as important as tonality, this painter manages to sum up characteristic facets of landscape experience ranging from an almost blinding stridency to calculatedly lyrical subtleties.’1) After some time in Hawaii, where Drexler had another exhibition of her work, she and Hultberg settled in New York City in 1967, living at the Chelsea Hotel, where her paintings were hung in the lobby alongside those of other artists who resided there, notably Larry Rivers. Apart from an obvious debt to nature, Drexler’s works were sometimes inspired by her abiding love of classical music, and she would often sketch while listening to concerts and performances at Carnegie Hall or the Metropolitan Opera.

Drexler spent the summer months on Monhegan Island sketching outdoors, creating a repertory of images that would provide the basis for larger abstract paintings created in the winter months in New York. By this time, however, Hultberg’s alcoholism was proving very difficult for her to cope with, so much so that summers with him on Monhegan were often miserable experiences for Drexler, and she sometimes avoided spending time there with him. In 1970 she was hospitalized for severe depression; as she wrote in a letter to Hultberg at around this time, ‘my belief in my own creativity keeps me going but who will know or care 100 years from now?’ Between 1969 and 1975 Drexler showed her colourful paintings in a series of four critically-praised exhibitions at the Alonzo Gallery on the Upper East Side; this period marks the highpoint of her commercial and critical success during her lifetime. However, she was never able to gain gallery representation and support, and struggled to achieve wider recognition. Nevertheless, she once noted that, ‘I’ve always felt deeply within myself I was a damn good artist, though the world didn’t recognize me as such. I wasn’t about to play their game.’

In 1983 Drexler abandoned New York to settle permanently on Monhegan Island, where she lived and worked alone for the last sixteen years of her life. (She and Hultberg eventually separated in 1984, though they never divorced.) The artist was happy there and began to sell her work to a handful of Maine collectors. The scenery of Monhegan was a continuing inspiration, and she became a firm part of the tiny, closely-knit community of people who lived on the small, rocky island year-round. As she pointed out, ‘There is no isolation in a place like this – impossible to find – but solitude is respected…I am not rich…but I have what I want. I mean, as long as I have food, heat, roof over my head, food for the cat and paint, I am happy. Oh, and Jack Daniels.’2 By the early 1990s Drexler’s work had become more stylized and representational, though still brilliantly coloured and, as always, anchored in a love of nature. She continued to work productively, content in the solitude of her beloved Monhegan Island, until her death, while listening to Mozart’s opera Don Giovanni, in December 1999, at the age of seventy-one.

Following Drexler’s death, stacks of unframed paintings and watercolour and gouache drawings, dating from the 1950s to the 1990s, were discovered in her home. Gradually her work began to attract a new audience, initially in Maine and then well beyond the state. In 2008 the first museum retrospective of Drexler’s oeuvre, numbering some fifty paintings, drawings and textiles, was presented at the Monhegan Museum and the Portland Museum of Art in Maine. More recently an exhibition devoted to the artist’s abstract works of the late 1950s and 1960s was held jointly at the Mnuchin and Berry Campbell galleries in New York, while another exhibition of her works was mounted at Bonhams auction house in New York. Paintings, drawings and prints by Drexler are today in the permanent collections of, among others, the Brooklyn Museum, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., as well as the Bates College Museum of Art, the Farnsworth Art Museum, the Monhegan Museum and the Portland Museum of Art, all in Maine.

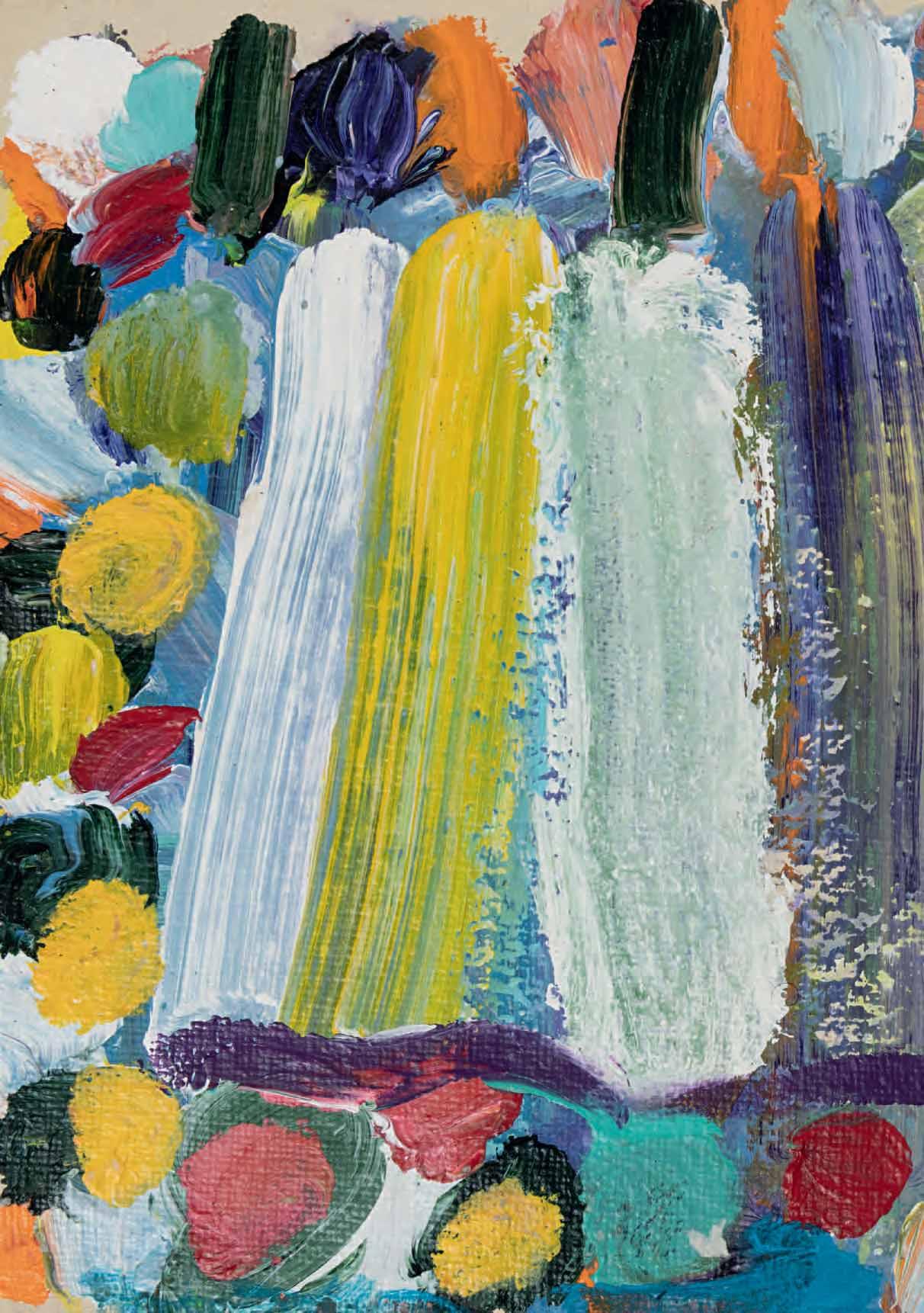

Lynne Drexler’s work was always first and foremost about colour. The artist’s characteristic use of squarish patches of vibrant colour, applied with short brushstrokes, is seen to brilliant effect in this early watercolour, which is datable to c.1959. The present sheet also reflects something of the influence on Drexler of her training with Hans Hofmann, notably his particular emphasis on a rhythmic approach to composition and a vibrant colour palette. This devotion to colour was something that Drexler also admired in the work of such artists as Vincent van Gogh and Henri Matisse3, with both of whom her works were often likened by later writers. A number of stylistically comparable drawings in watercolour or gouache of the same date remain in the artist’s estate4, while others are in private collections.

Pencil and coloured chalks on buff paper, within a fictive drawn mount with double framing lines in pencil. Signed with the initial G. in pencil at the lower right. Inscribed Cornwall / by Gluck in blue ink at the lower right corner of the sheet.

64 x 121 mm. (2 1/2 x 4 3/4 in.) [image]

179 x 253 mm. (7 x 10 in.) [sheet]

PROVENANCE: Michael Palmer, in March 1991; Private collection.

EXHIBITED: Unidentified exhibition A Century of Change, (c.1991?), no.47 (according to a typewritten label attached to the reverse of the frame).

Born into a wealthy Jewish family in London, as a teenager Hannah Gluckstein rebelled against her conservative upbringing, cutting her hair, dressing in men’s clothes and rejecting her given name, eventually insisting on being referred to simply as ‘Gluck’. She attended the St. John’s Wood Art School and, on a visit to the artist’s colony of Lamorna in Cornwall, befriended the painters Alfred Munnings, Samuel John ‘Lamorna’ Birch, and Laura and Harold Knight, who encouraged her in her desire to become an artist. Another early supporter was the department store magnate Gordon Selfridge, who set up a studio within his store for Gluck to paint portraits in one sitting, although she soon abandoned this as she felt it was making her work too slick, and because she preferred to choose her own subjects.

Over the course of her career, Gluck painted landscapes, theatrical scenes, exquisite floral still lives and, most significantly, a series of superb and stylish portraits. She worked very slowly, and chose to only have solo exhibitions, refusing to take part in group shows. Her first exhibition was held at the Dorien Leigh Galleries in 1924, and all sixty works in the show were sold. A second exhibition was mounted at the Fine Art Society in 1926, and again met with critical and commercial success. Around the same time Gluck moved into a large house in Hampstead and had a modern and airy studio built in the garden. She lived there with her lover, the society florist Constance Spry, whose work inspired her to paint the large flower compositions for which she became well known. For her next exhibition in 1932, she transformed the galleries of the Fine Art Society into a ‘Gluck room’, decorated with wall panels and pilasters in a muted colour scheme to create a harmonious arrangement of interior decoration. She also had her paintings framed in a special white, three-stepped frame of her own patented design, which came to be known as the ‘Gluck frame’ and was used for all her work from then on. The exhibition of twenty-nine paintings, including many of flowers, was again a huge triumph, and was followed by another equally successful show in 1937.

In between these two exhibitions Gluck met the socialite and philanthropist Nesta Obermer, with whom she was to have an intense relationship until 1944, and who remained a lifelong friend. After the 1937 exhibition, Gluck spent most of her time travelling with Nesta and seems to have only completed one painting before the outbreak of the Second World War, which shattered the world of high society and style that she had flourished in. Leaving London, she worked on portrait commissions, but began suffering from what seems to have been panic attacks that prevented her from being very productive. In 1944 Gluck settled in the West Sussex town of Steyning, where she lived with the sisters Nora and Edith Shackleton Heald; the latter was to become the artist’s partner for the rest of her life. She painted relatively little, however, and instead focussed her attention on a campaign to improve the quality of fine artist’s materials and establish a recognized British standard for them. Gluck did not show her work in public in London for over thirty-five years, until a retrospective exhibition at the Fine Art Society in 1973, which included mainly works from the 1920s and 1930s, along with some recent paintings. Notwithstanding the huge success of the exhibition, Gluck suffered from poor health and was unable to work again. She died in January 1978, at the age of eighty-two.

Pencil and coloured chalks on buff paper, within a fictive drawn mount with triple framing lines in pencil. Inscribed Cornwall / by Gluck in blue ink at the lower right corner of the sheet. Further inscribed Cornwall / Painted / by Gluck (artist) / or Gluckstein. in blue ink on the verso.

59 x 116 mm. (2 1/4 x 4 1/2 in.) [image]

178 x 253 mm. (7 x 10 in.) [sheet]

PROVENANCE: Michael Palmer, in March 1991; Private collection.

EXHIBITED: Unidentified exhibition A Century of Change, (c.1991?), no.48 (according to a typewritten label attached to the reverse of the frame).

It was in her early years as an artist in the small fishing village of Lamorna that Gluck first developed an abiding love of landscape, inspired by the light and scenery of this area of Cornwall. Indeed, she came to love Cornwall and kept a studio there throughout her life. Her landscape compositions were almost always characterized by a large expanse of sky above a very low horizon. In some unpublished ‘Notes on Landscape Painting’, written in 1940, she recalled of the work she produced in Cornwall: ‘My landscapes were the first that truthfully showed the immediate impression one gets there – that of very little land and great expanses of sky...The sky is a bowl, not a flat backcloth and its colour and light reflect in every blade of grass, every twig…the colour of the sky permeates the landscape under that sky…Wind and weather change continuously, a landscape is chameleon to the light.’1 Gluck kept a studio at Lamorna until 1947, and in 1953 acquired a cottage in the nearby village of St. Buryan.

Although it is often difficult to date the artist’s landscapes, or to identify their exact location, the present sheet is very closely related to a small Cornish landscape painting of 1964, today in a private collection, in which the same tower – perhaps the granite tower of the late 15th century parish church of St. Buryan – appears on the horizon2. (It has also been suggested that the tower depicted may be Prospect Tower, an 18th century architectural folly on the grounds of the Cotehele Estate in eastern Cornwall.) A small ink and wash drawing on blue paper by Gluck of an identical composition – although of a square rather than rectangular format, and with a greater expanse of sky (fig.1) – is in a private American collection3.

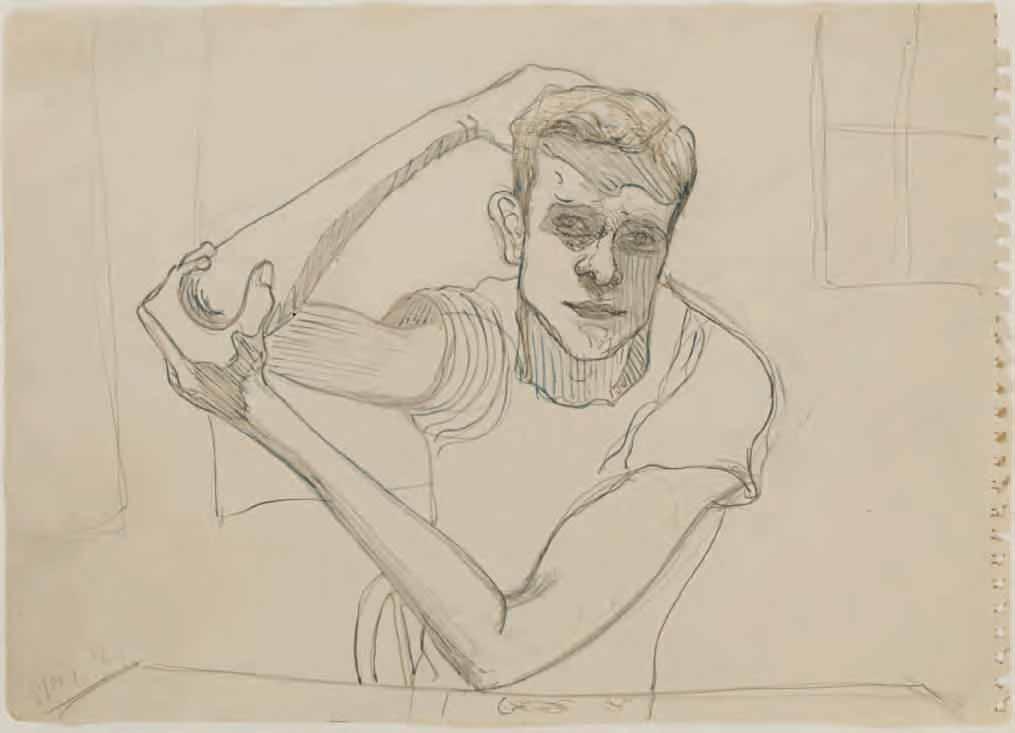

Gladwyne (Merion Square) 1900-1984 New York

Richard Gibbs

Pencil and ink on paper; a page from a sketchbook. Signed and dated Neel ’64 in ink at the lower left. 249 x 350 mm. (9 3/4 x 13 3/4 in.)

PROVENANCE: Robert Miller Gallery, New York; Private collection, United Kingdom.

Although Alice Neel’s career spanned much of the 20th century – she was born in a town in southeastern Pennsylvania three weeks into the new century – it was not until she was already in her late sixties that she began to enjoy critical acclaim, after working for much of her life in relative obscurity. Neel received her artistic training at the Philadelphia School of Design for Women, where she studied between 1921 and 1925. She then spent two important and formative years in Havana, where she lived with her husband, the Cuban artist Carlos Enriquez, with whom she had two daughters. Neel participated in a number of exhibitions in Cuba before eventually returning to America and settling in New York City, which was to be her home – and constant muse – for the remainder of her life. In 1930 she suffered a nervous breakdown, caused by Enriquez’s abandonment of her and his return to Cuba with their second daughter Isabetta. (Their first child had died of diphtheria in 1927.) By 1932 Neel was living in Greenwich Village, surrounded by a vibrant community of artists, intellectuals and political activists, many of whom sat for her. She exhibited in a number of group shows and had relationships with a series of lovers, all of whom appeared in her work. (One of these, Kenneth Doolittle, in a rage, destroyed over three hundred drawings and some fifty paintings in her studio in 1934.) During these years at the height of the Great Depression, Neel worked for the government’s Public Works of Art Program and later the Federal Art Project, part of the Works Progress Administration, with which she remained associated until 1943.

Throughout Neel’s nearly seven-decade career she expressed a particular concern with issues of social justice and civil rights, and much of her work made manifest a kind of radical humanism. A member of the Communist Party since 1935, she was involved with leftist and socialist movements throughout her life. In 1938 Neel had her first solo exhibition at a gallery in New York, and the same year moved uptown to Spanish Harlem. For the next twenty-four years she lived and worked there, in the area of the east side of Manhattan known to its inhabitants as El Barrio, which became the setting for many of her paintings of cityscapes and genre scenes. Her studio was her large living room, and it was there that she painted numerous portraits of her Black and Puerto Rican neighbours, some of which were included in a solo exhibition at the A.C.A. Gallery in 1950. As a review of the exhibition in the New York Times noted, ‘Her approach is frankly expressionistic; she uses a great deal of black, accentuating profile lines, and catches figures in strongly individual poses. And its dramatic intensity succeeds because of unmistakable artistic sincerity.’

Although Neel’s paintings were occasionally included in group exhibitions and she had further solo exhibitions in 1951, 1954, 1960 and 1962, her work garnered relatively little critical attention until an article on her portraiture was published in Art News in 1962. The following year Neel began to be represented by the Graham Gallery in New York, which mounted several exhibitions of her work between 1963 and 1980.

Neel continued to work mainly as a painter of portraits, one of which was used for the cover of Time magazine in 1970; while the same year she painted one of her best-known works, a striking portrait of Andy Warhol. She regularly gave slide lectures about her work throughout the country; these presentations were always highly entertaining and proved very popular. A long-overdue retrospective exhibition of Neel’s oeuvre, numbering fifty-eight paintings, was mounted at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1974, while another large exhibition of over eighty paintings was held at the Georgia

Museum of Art the following year. By the middle of the 1970s Neel was widely recognized, albeit belatedly, as one of most significant figurative painters of the post-war era, and was the recipient of a number of awards and honours. In 1982 she began being represented by the Robert Miller Gallery, and also contributed to the first illustrated monograph of her oeuvre, which appeared the year before her death from advanced colon cancer in 1984. Today, Neel’s work is held in countless museums in America and Europe, while in recent years she has been the subject of major museum exhibitions in Bilbao, Edinburgh, The Hague, Hamburg, Helsinki, Houston, London, Malmö, New York, Paris, Stockholm and Washington, D.C.

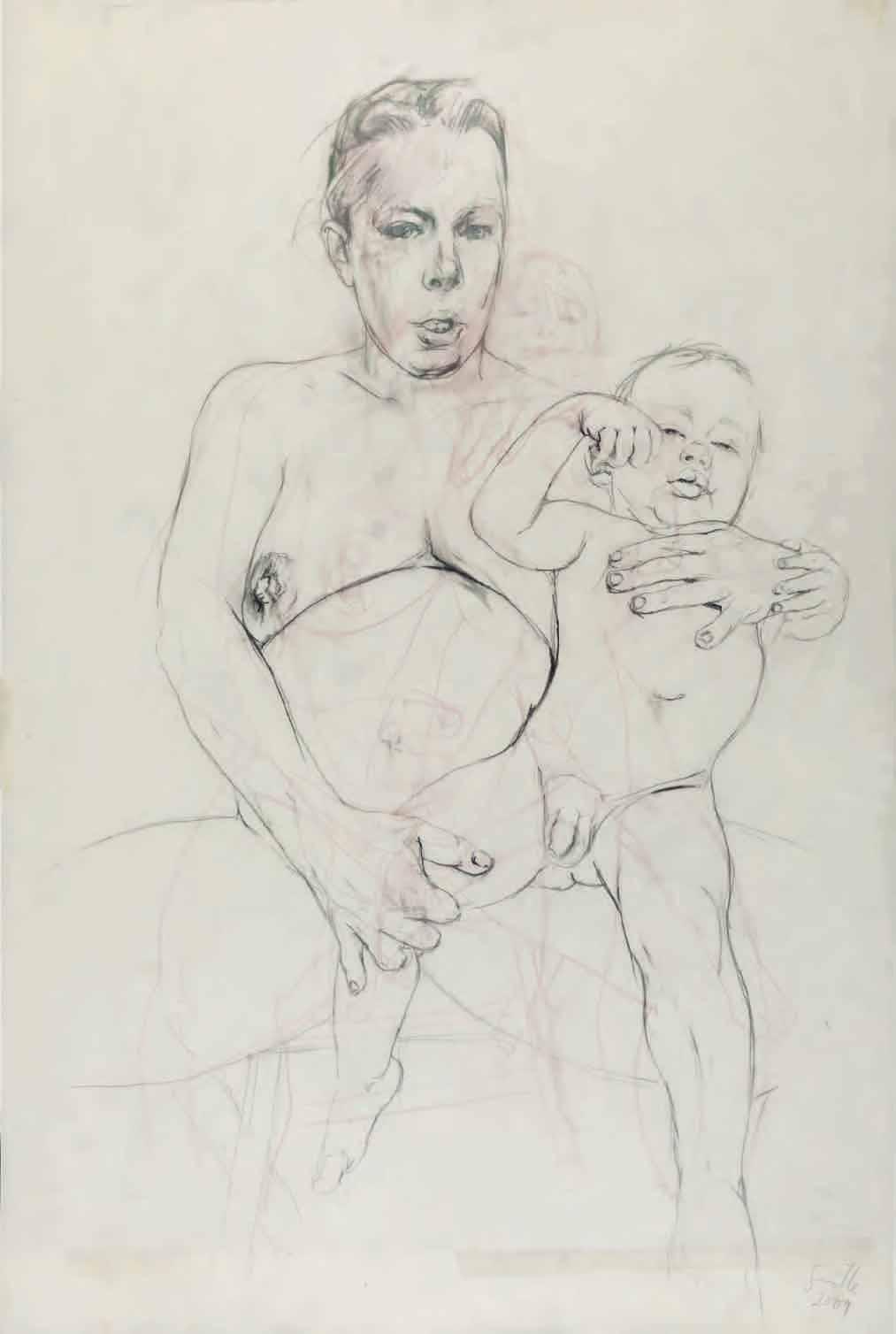

Alice Neel tended to reject the label of portraitist, preferring to describe her work as ‘pictures of people’. The artist’s biographer Phoebe Hoban has recently written that ‘Her stated goal was to chronicle the Zeitgeist, and Neel was, from the very start, fiercely democratic in her subjects, portraying her lovers, her children, pregnant nudes, fringe characters, and famous art-world figures. Neel’s art provides a vivid lens with which to view the twentieth century…Few portrait painters besides Lucian Freud have been as unflinching in their gaze. But while Freud is a clinician, his cold dissection of his subjects often chilling, Neel is an avowed humanist, interested not only in her subjects’ physiognomy but in their heart and soul…“That is the microcosm,” she said. “Everything can be there – the person, his position in life, how he feels, how he thinks, what life does to him, how he retaliates, the spirit of the times, everything.”’1

In general, Neel did not prepare her canvases with preparatory studies on paper, preferring instead to draw with paint directly on the canvas. (As Hoban has pointed out, however, ‘even in her paintings, drawing remained, for Neel, the starting point, the compass through which she navigated her craft. One only has to look at the video snippets of Neel, wielding her brush like a pencil, as she tackles an empty canvas.’2) Nevertheless, drawing played an important role in her artistic practice, the immediacy of the process allowing her to quickly capture a sitter’s pose or a subject seen on the street. As the scholar Jeremy Lewison has noted, ‘the activity of drawing on paper filled the interstices of time; it allowed her to work on other ideas simultaneously, and sometimes more experimentally or casually…It is [the] combination of the detailed and the economical that characterises Neel’s work as both a painter and a draughtsman…Neel’s approach to drawing and painting, if not experimental, is authoritative, distinctive and engaged with a long tradition that she sought to develop rather than overthrow.’3

A committed draughtsman, Neel produced a large number of drawings and watercolours, although several hundred sheets were destroyed by Doolittle in her studio in 1934. While her relatively few surviving drawings of the 1920s and early 1930s were typically executed in watercolour, by the late 1930s she was working mostly in pencil or black ink, and her drawings remained largely monochromatic, with some exceptions, for the remainder of her career. Neel regarded her drawings not as studies for paintings but as fully independent works. For much of her career, however, her drawings were also very private, intimate works, and not intended to be exhibited in public. In 1978 the first retrospective exhibition of Neel’s works on paper was held at the Graham Gallery, and after the artist’s death further gallery and museum shows devoted solely to her drawings and watercolours followed in 1986, 2003, 2008, 2013 and 2015.

Drawn in 1964, on a page from one of the artist’s sketchbooks, the present sheet depicts Richard Gibbs, about whom very little is known. Neel painted several portraits of Gibbs, including works dated 19614 and 19655, while a very large canvas, executed in 1968, is today in a private collection in Minneapolis6. It remains unclear who Gibbs was, however. Neel often painted friends and neighbours, as well as more obscure figures, but nothing further is known of this particular sitter.

In the brochure accompanying the first exhibition devoted solely to drawings by Neel at the Graham Gallery in 1978, the art historian Ann Sutherland Harris wrote of the artist that ‘We realize again that her paintings are full of visible drawing, sketched passages, emphatic contour lines…we are reminded that Neel was trained to draw by the most academic and traditional of methods and that she knows her craft. But her formidable gifts have never been used to describe the surface of life. Her drawings, as much as her paintings, probe for the truth and contribute to her incisive, idiosyncratic but compassionate record of life in America in this century as she had seen it and as she continues to see it.’7

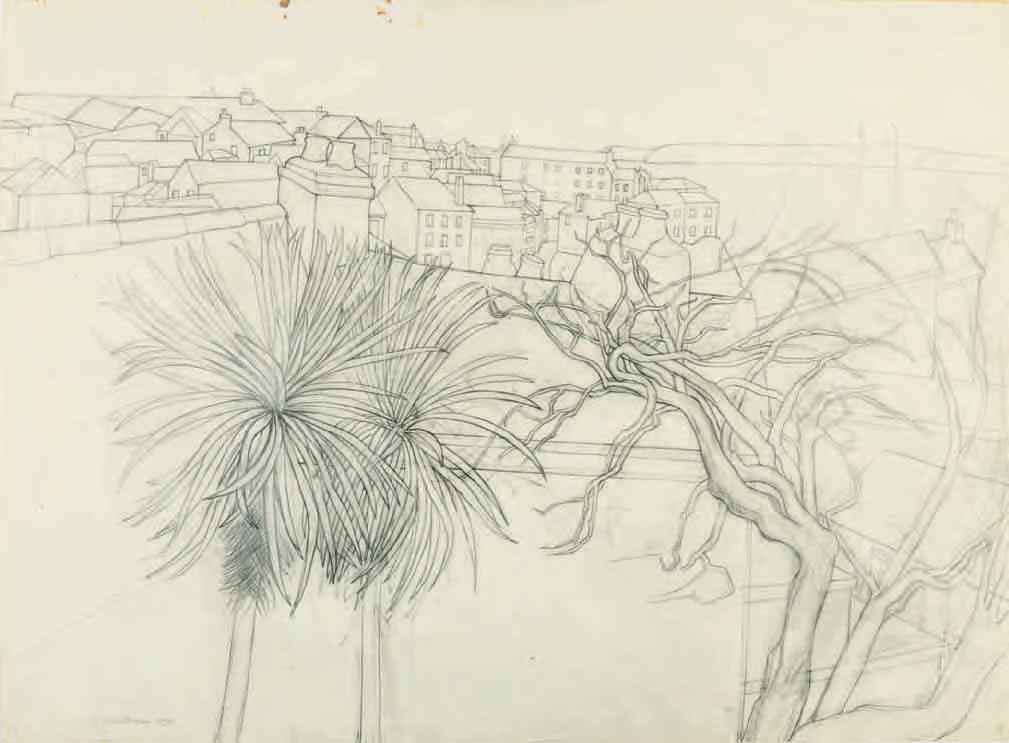

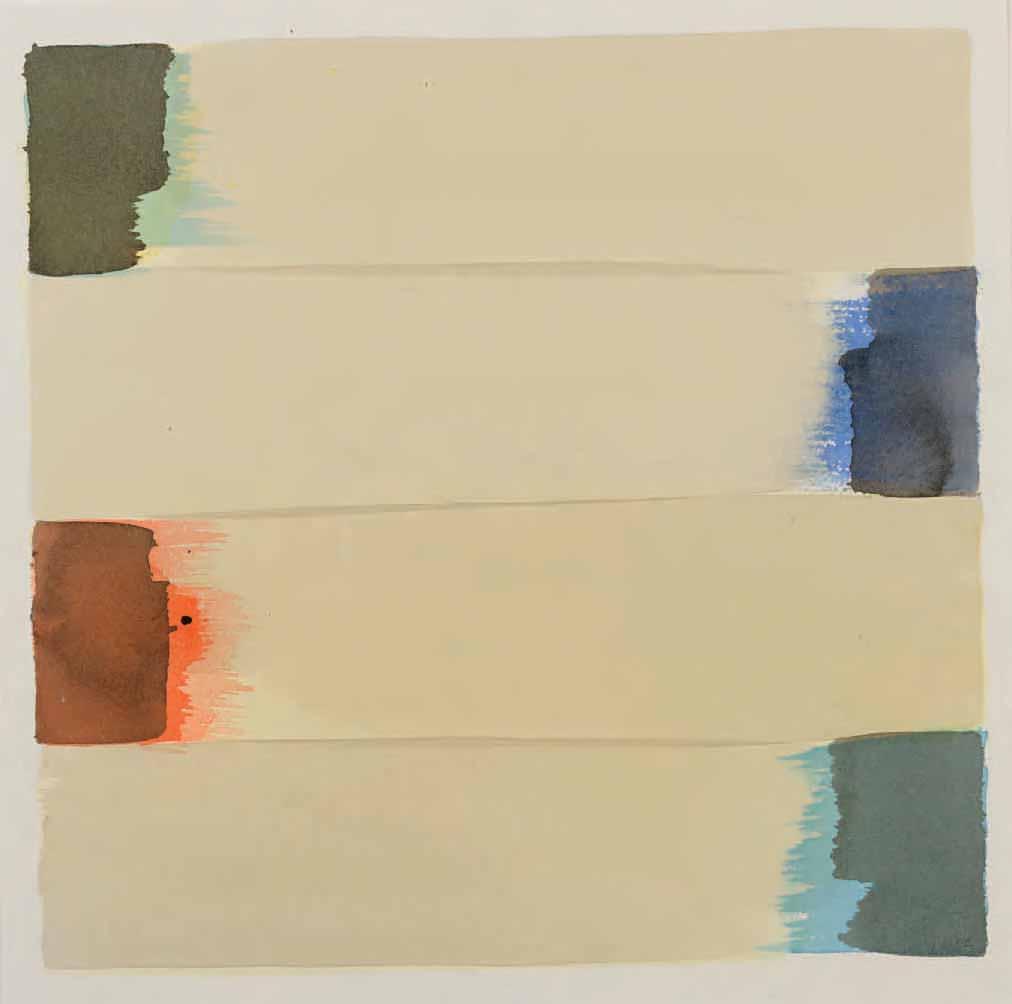

St. Andrews 1912-2004 St. Andrews

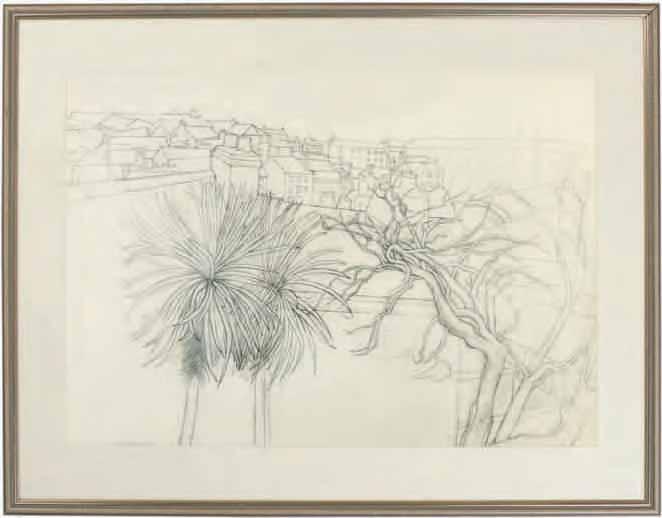

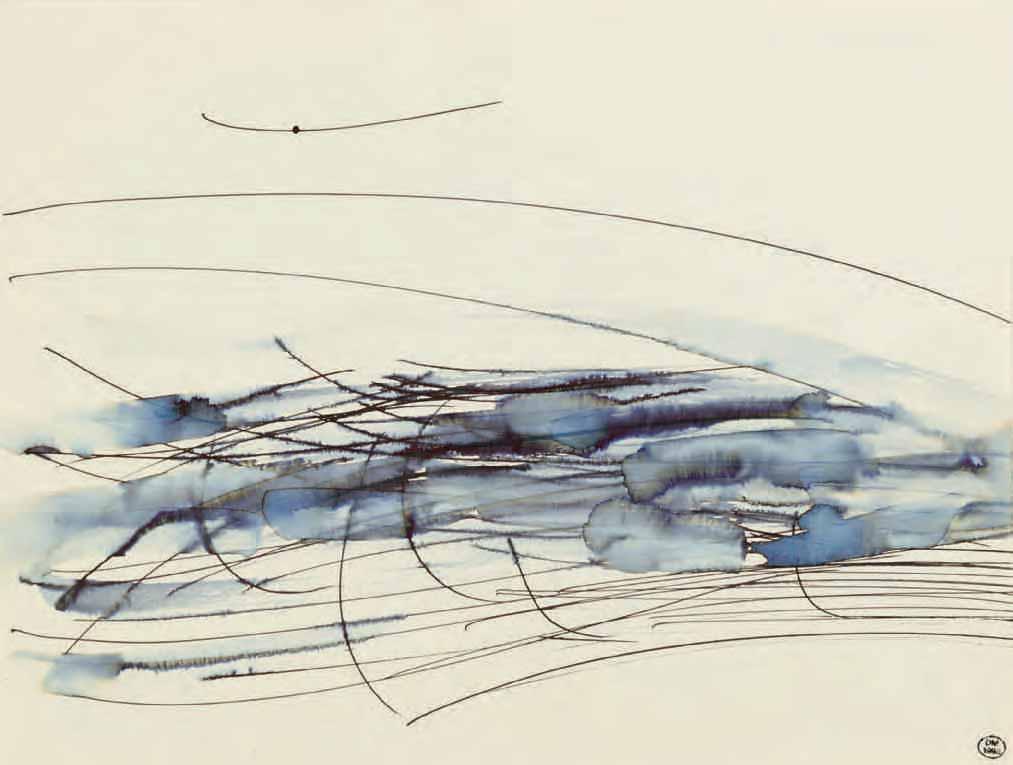

Three Trees (St. Ives)

Pencil, with stumping, on paper. Signed and dated W. Barns Graham 1971. in pencil at the lower left. Further extensively inscribed TITLE THREE TREES (ST. IVES) (FROM GOONHILLY BEN NICHOLSONS HOUSE) ST. IVES CORNWALL / DATE 1971 / SIZE WORK. 54 x 74.5 cms. (FRAMED. 71 x 92 cms) or work 21 1/4” x 29 3/8”, Framed 28 1/8” x 36 1/4” / MEDIUM PENCIL DRAWING ON PAPER / ARTIST W. BARNS-GRAHAM [with signature] / 1 BARNALOFT / ST IVES / CORNWALL / CAT NO 02/71/D in black ink on the backing board.

530 x 755 mm. (20 7/8 x 30 in.) [image]

560 x 761 mm. (22 x 29 3/4 in.) [sheet]

PROVENANCE: Acquired in the late 1980s, possibly directly from the artist, by Lea Ford, London; Anonymous sale, London, Sotheby’s, 20 March 2019, lot 209; Private collection, London.

The Scottish painter, draughtsman and printmaker Wilhelmina (known as ‘Willie’ to friends) BarnsGraham was born in St. Andrews in Fife and studied at the Edinburgh College of Art between 1931 and 1937, her tenure sometimes interrupted by recurring health issues caused by weak lungs. While at the College she earned several awards and travel scholarships, and had her work included in the annual Summer Exhibitions of the Royal Scottish Academy. In March 1940, the twenty-seven-year-old artist moved to St. Ives in western Cornwall, where she met Ben Nicholson, Barbara Hepworth and Naum Gabo, as well as the local ‘primitive’ painter Alfred Wallis and the potter Bernard Leach. Barns-Graham maintained a studio in St. Ives for the rest of her long career, which was to last almost eight decades. In 1942 she became a member of the St. Ives Society of Artists and the Newlyn Society of Artists, exhibiting paintings influenced by Cornish landscapes at both institutions between 1942 and 1949.

After participating in numerous group exhibitions in Cornwall and Edinburgh, Barns-Graham had her first solo exhibition at the Downing Gallery in St. Ives in 1946, followed by a second show there two years later. In 1949 she left the St. Ives Society of Artists and became a founding member of the more progressive breakaway group, the Penwith Society of Artists, where she was to exhibit regularly for the next fifty years. Her work began to be included in group shows in London and she also spent some time in Grindelwald in Switzerland, inspiring a series of paintings, drawings and gouaches of glaciers executed between 1948 and 1952. In 1950 Barns-Graham’s painting Upper Glacier was acquired by the British Council, and the following year her large painting Porthleven won the St. Ives Festival of Britain prize for painting, while the same year her work was included in Herbert Read’s book Contemporary British Art

In 1952 Barns-Graham had her first solo exhibition in London, at the Redfern Gallery. Her travels took her to Paris, Venice and Tuscany, and by 1956 her work was regularly being exhibited in London. Although she was fully integrated into the modernist milieu of St. Ives, with the arrival of artists such as Peter Lanyon, Roger Hilton, Terry Frost and Bryan Winter, Barns-Graham often felt at a disadvantage in the competition for recognition and contacts with dealers in London and abroad. She was also unfairly regarded, by some critics and scholars, as a relatively minor member of the St. Ives school1. In 1960 Barns-Graham began to divide her time between Cornwall and Scotland, having inherited a house near St. Andrews. (She also rented a studio in London between 1961 and 1963.) In 1963 the artist moved into a studio at No.1 Barnaloft on Porthmeor Beach in St. Ives, and by the mid 1960s she had begun to work in a severely geometrical mode of abstraction.

Throughout the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s Barns-Graham’s paintings were shown widely in galleries in Cornwall, London and Scotland, as well as in touring group exhibitions organized by the Arts Council. Although by this time her reputation was largely established as an abstract artist, she continued to paint

representational subjects, notably the Cornish landscapes that had been the subject of her first solo exhibitions. (The artist’s landscapes, which later included views of Scotland, Italy and Switzerland, often led in turn to more abstract compositions.) The late 1980s found Barns-Graham producing a vast array of freely-painted, colourful abstract paintings, usually executed on paper rather than canvas, as well as screenprints, which introduced her work to a new audience and market. In 1989 a retrospective exhibition of fifty years of her work was held in museums in Penzance, Edinburgh, St. Andrews, Perth and Ayr, followed three years later by another travelling exhibition on the occasion of the artist’s eightieth birthday. As she stated in 2001, the same year that she was awarded a CBE, ‘In my paintings I want to express the joy and importance of colour, texture, energy and vibrancy, with an awareness of space and construction. A celebration of life.’ Barns-Graham continued to work on her vibrant paintings and screenprints until her death in January 2004, at the age of ninety-one.

Barns-Graham was a draughtsman of considerable talent. As she stated in 1989, ‘I have always been interested in drawing and have spent considerable time constructing my compositions…After sessions of drawing, I turn my back on the experience and return to painting in the abstract, where there is a meeting point of abstracted ideas. This swing between outward observation and inward perception, or vice versa, has always increased my awareness.’2 Her drawings were admired by Ben Nicholson, with whom she shared a similar approach to the depiction of landscape in her works on paper, and the two artists often went on sketching expeditions together. As has been noted by one scholar, ‘a natural draughtsman, she quickly mastered the ability to resolve a landscape into a few significant lines...The Nicholson approach treated the land as sculpture, not as a plane laid out under the sky, and this necessitated the characteristic high viewpoint of both Nicholson and Barns-Graham. The experience [of sketching alongside Nicholson] encouraged her to seek out places where these sculptural forms were found in nature, whether in Cornwall, the Scillies, the Grindelwald glacier, the clay workings of Palinuro, the rocks of Formentera or later the landscape of Orkney. Her encounter with these places forms a constant background to her work.’3

The view depicted in this large drawing, as noted on the backing board, was taken from the terrace of Ben Nicholson’s former home in the centre of St. Ives. Nicholson had moved to the house, then called Trezion, in 1955, and had renamed it Goonhilly, a Cornish name. As Nicholson described the view, in a letter of February 1955 to Herbert Read, ‘It’s an absurd place, almost as if one had made it and its surroundings oneself – v. romantic and with a whole series of different levels from which one sees between rooftops the Atlantic, the Island, St. Ives Bay, Godrevy & finally, from the topmost ‘lookout’ level, slap down into the harbour itself.’

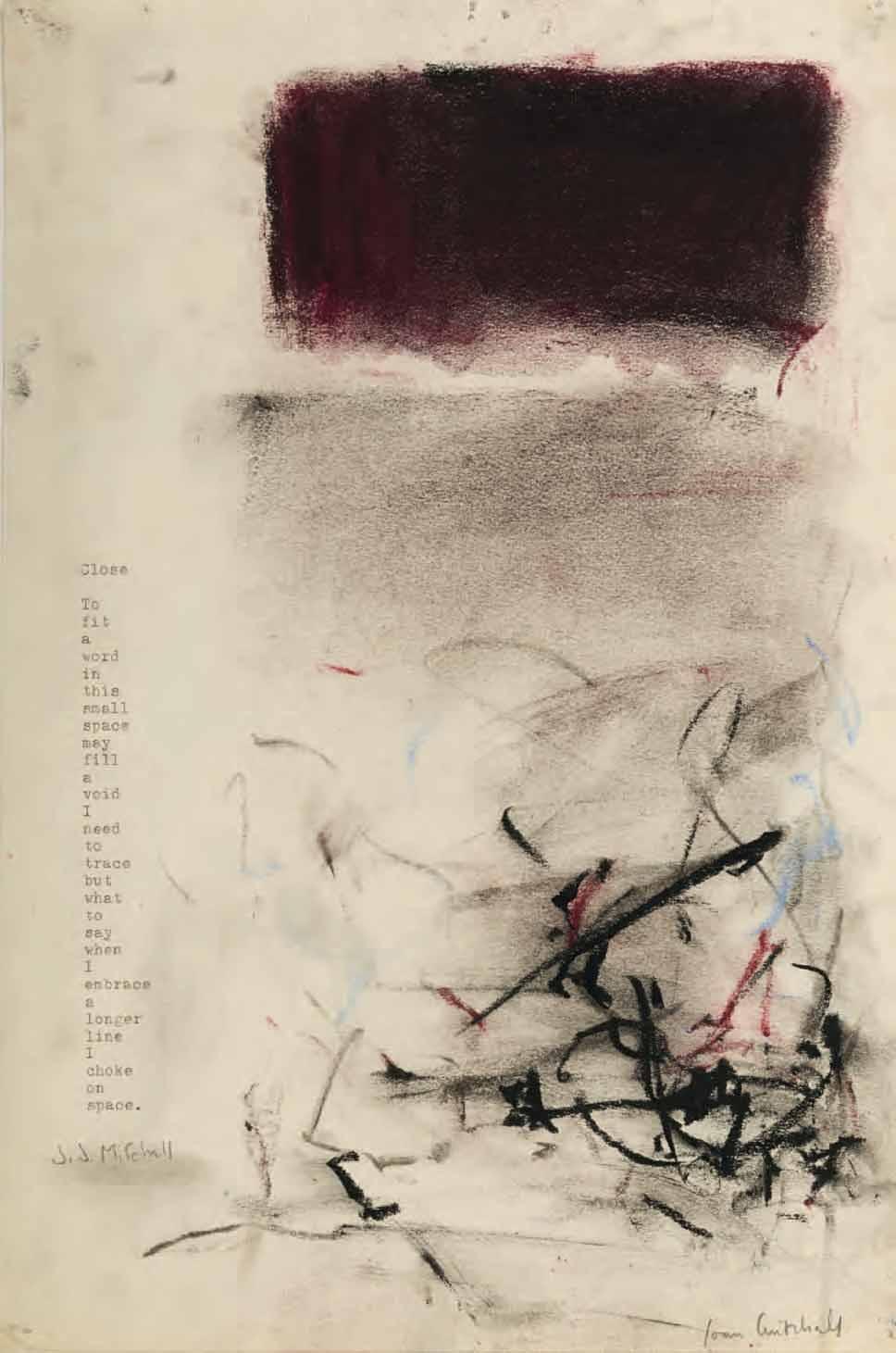

Pastel and typewriter ink on paper; a page from a sketchbook. Signed Joan Mitchell in pencil at the lower right. A poem by J. J. Mitchell entitled Close typewritten along the left edge of the sheet: Close / To / fit / a / word / in / this / small / space / may / fill / a / void / I / need / to / trace / but / what / to / say / when / I / embrace / a / longer / line / I / choke / on / space. Signed J. J. Mitchell in pencil at the lower left. 353 x 235 mm. (13 7/8 x 9 1/4 in.)

PROVENANCE: Acquired from the artist by a private collector, New York; Thence by descent.

One of the foremost American Abstract Expressionist painters, Joan Mitchell produced a superb body of oil paintings, pastels and prints between the 1950s and the 1980s. Trained at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, from which she graduated in 1947, Mitchell spent time living and working for brief periods in Mexico, Paris and the south of France before settling in New York. 1950 marks the true start of her career as a painter, with the early influence of artists such as Willem de Kooning, Arshile Gorky and Franz Kline visible in her work. She became a habitué of the Cedar Tavern in Greenwich Village, a popular meeting place for avant-garde artists and writers, and was friendly with such painters as de Kooning, Kline, Phillip Guston, Grace Hartigan and Helen Frankenthaler, as well as the poets Frank O’Hara and John Ashberry. In 1951 Mitchell took part in the seminal Ninth Street Show, organized by the artist’s group known as ‘The Club’ and the art dealer Leo Castelli. She had her first solo exhibition at Eugene Thaw’s New Gallery in New York in 1952, which was a critical if not commercial success, and the same year moved into a studio on St. Mark’s Place that she would keep until the early 1980s, even when living and working abroad.

Although Mitchell had a series of seven solo exhibitions at the Stable Gallery in New York between 1953 and 1965, by 1955 she had also begun to divide her time between New York and Paris. There she met the French-Canadian painter Jean-Paul Riopelle, with whom she would have a long and often fractious relationship. Her work began to be included in group shows and museum exhibitions, notably at the Jewish Museum in New York in 1957, the Venice Biennale in 1958, Documenta II in Kassel in 1959 and the Guggenheim Museum in New York in 1961. By this time her paintings had been acquired for the collections of both the Whitney Museum of American Art and the Museum of Modern Art in New York, as well as the Art Institute of Chicago. After 1959 Mitchell painted almost all of her work in France, and she was to spend the last thirty-five years of her career there, supported by the French dealer Jean Fournier, at whose eponymous Parisian gallery she exhibited from 1967 until her death.

When Mitchell’s mother died in 1966 she inherited part of a family trust, and the following year purchased a large house, known as ‘La Tour’, at Vétheuil, a town on the banks of the Seine about sixty kilometres northwest of Paris. Mitchell and Riopelle lived there together, and she had a separate large studio behind the house. The size of the Vétheuil studio enabled her to work on a grander scale than before, and the first works she produced there reflected ‘the artist’s determination to allow her new, bucolic environment at Vétheuil to take her in new directions. Her move from Paris to the quiet and always beautiful two-acre property overlooking the Seine afforded her a new privacy and a physical connection with the landscape.’1 The paintings Mitchell produced at Vétheuil have a more expansive approach –perhaps partly inspired by the changing landscape, with a broad view of the Seine river, that she could see from the windows of her new home – than the works she had produced in her Paris studio. She was also able to create works in a diptych or triptych format, and sometimes even larger, fourpanel compositions, characterized by bright colours and bold, energetic brushstrokes. The first major retrospective of Mitchell’s paintings took place in 1974 at the Whitney Museum.

In 1979 Mitchell and Riopelle separated, and for some time thereafter she found herself unable to work on large canvases. She took a small studio in Montparnasse in Paris, and there began to work on a series of pastel drawings. As the scholar Jane Livingston has written of these works, ‘Mitchell’s work on paper was something she separated entirely from her painting activity and an endeavor about which she apparently had mixed feelings. She would say that her pastels were “lady paintings”. She did not want to be called a lady painter unless she was using the term herself, nor did she truly invest her deepest energies or intellect in these drawings…Although making drawings probably never rivaled printmaking in her own priorities, her place in Montparnasse gave her respite, and a way of continuing to work that seems to have been cyclically therapeutic. Ironically, her activity in this studio was literally toxic to her; she worked in a badly ventilated space, using powdery substances, including cadmium, which certainly exacerbated the lung problems that became more and more debilitating.’2

With the loyal support of her dealers Jean Fournier in Paris and Xavier Fourcade in New York, Mitchell’s work was acquired by a network of private collectors in America and Europe. Soon after returning to large-scale painting around 1980, the artist had her first European museum exhibition at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris. The early 1980s found her creating some of her finest works, notably the Grande Vallée series of twenty-one lyrical canvases painted during the period of just over a year, between 1983 and 1984. She also began producing a series of colour lithographs at the Tyler Graphics studio in upstate New York. Health issues and a cancer diagnosis, however, meant that there were long periods when the artist was unable to work as before. Another major retrospective exhibition travelled throughout the United States in 1988-1989, and Mitchell continued working on paintings and prints until the very end of her life. She died, of advanced lung cancer, in October 1992, at the age of sixty-six.

Mitchell’s works on paper – mainly executed in pastel, but also in watercolour, charcoal, ink and wax crayon – were widely exhibited both during and after her career. A retrospective exhibition devoted to her pastels was held at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1992. In the catalogue of that exhibition, Klaus Kertess wrote of her pastels that ‘They have an elemental directness as well as a sensuous, chromatic braveness not customarily associated with the pastel’s paler and politer proclivities. They are at once vulnerable and defiant. Mitchell has fully exploited the fragile powdery effusiveness of pastel – the way it fugitively settles into and illuminates the nap of the paper surface. Pastel’s willing responsiveness to the varying pressures of the hand has been deployed in a startling panoply of mark making, from blurred staccato tracks, to amorphous wisps, to sinuous trajectories of athletic aggressiveness. These pastels have a kind of velvet fury.’3

Similarly, in a review of the 1992 Whitney exhibition, one critic noted of Mitchell’s pastels that ‘Essential to all of her work is the attention she gives to the physical weight of pigment. The pastel is applied in thick, emphatic strokes here, tangles of loose calligraphic thread there, with a judicious use of rubbing, smudging and overdrawing throughout. The interwoven colors are many and rich, with a bias toward vegetable hues – succulent greens, dark reds – that make a few of these drawings look like informal but exotic bouquets.’4

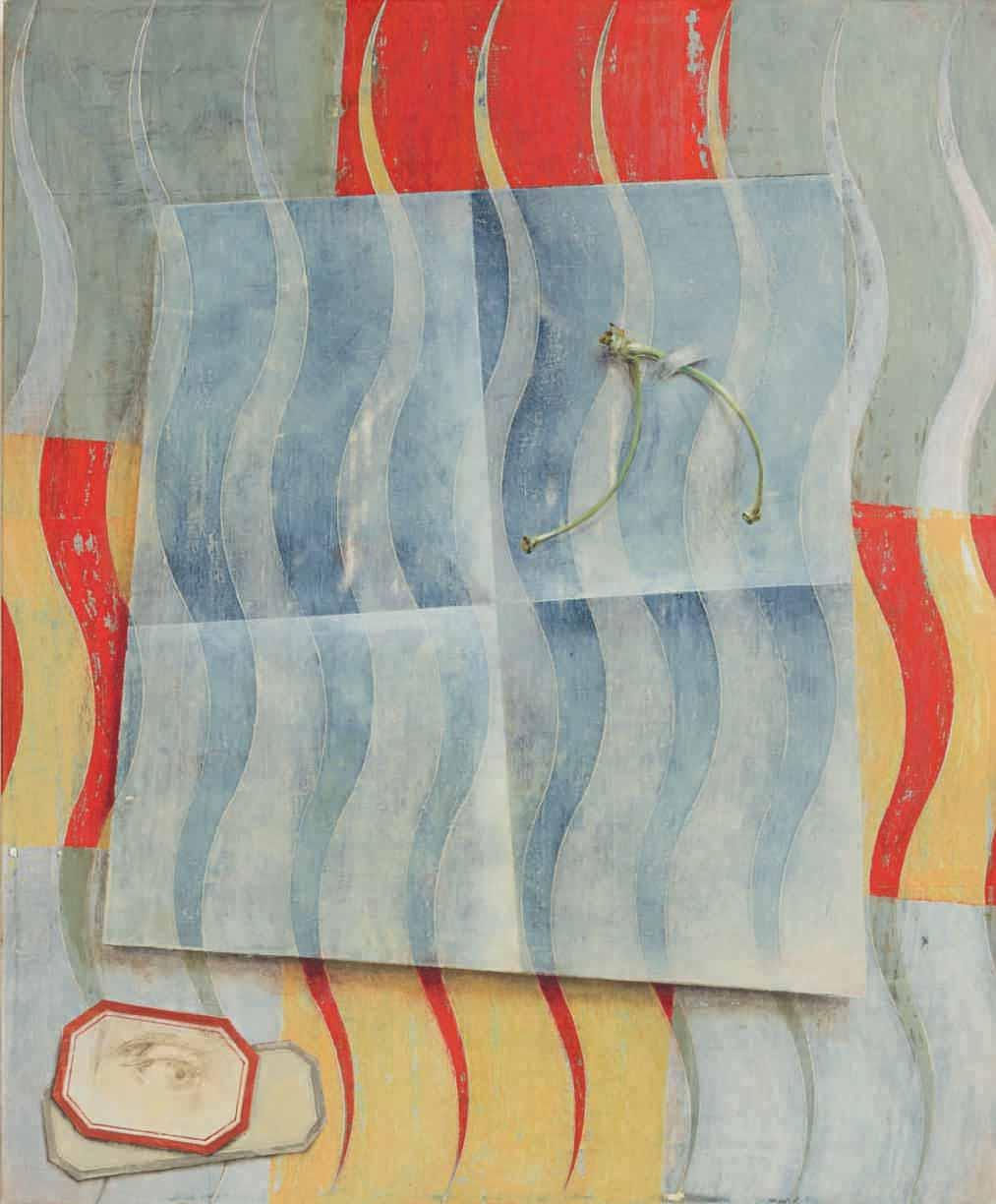

Drawn in 1975, this is one of Joan Mitchell’s ‘poem pastels’; a series of unique abstract pastel compositions incorporating typewritten free-verse poems by five of her poet friends – James Schuyler, Jacques Dupin, J. J. Mitchell, Chris Larson and Pierre Schneider5. The artist referred to this group of pastels, in a letter to her New York dealer Xavier Fourcade, as ‘colour abstracts.’ As Jane Livingston has noted ‘The pastels she did for special occasions, particularly the ones made collaboratively with five of her poet friends…had a special meaning for her that set them apart from the small drawings done in series.’6

The present sheet incorporates the poem Close by the writer and poet J. J. Mitchell (1940-1986), a close friend of Frank O’Hara, who stayed with Joan Mitchell at Vétheuil from the summer of 1974 to the end of 1975.

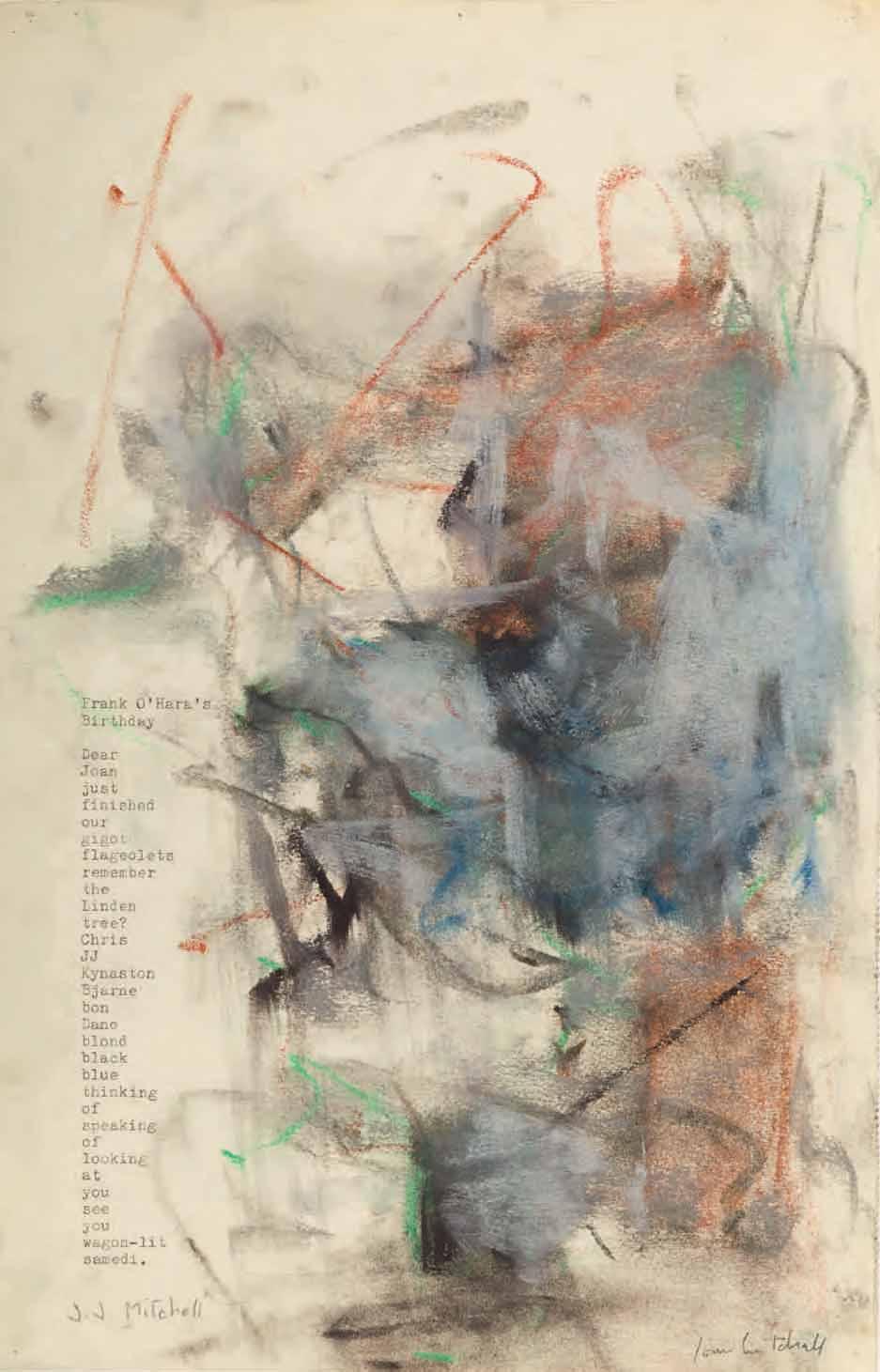

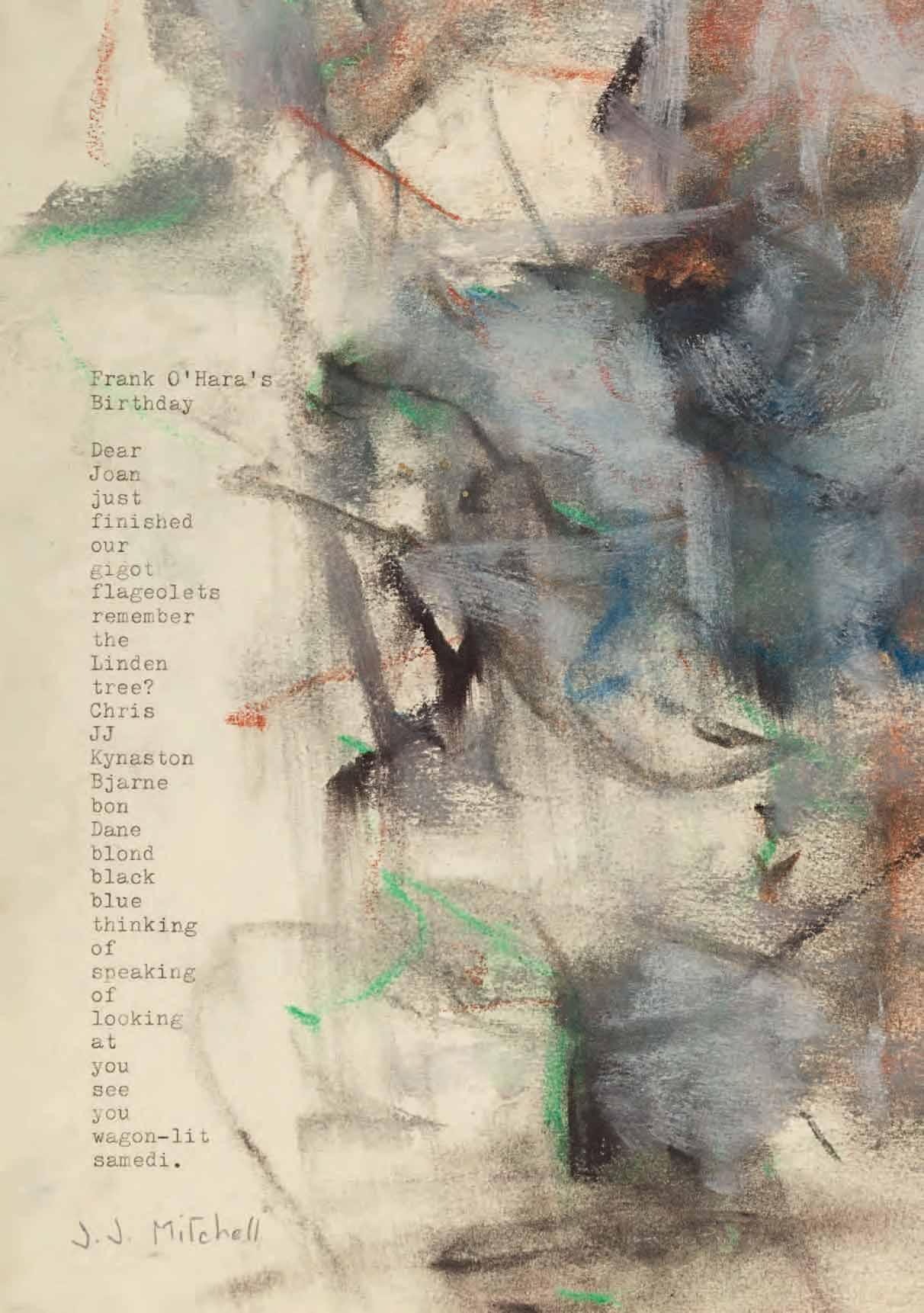

Pastel and typewriter ink on paper; a page from a sketchbook. Signed Joan Mitchell in pencil at the lower right. A poem by J. J. Mitchell entitled Frank O’Hara’s Birthday typewritten along the left edge of the sheet: Frank O’Hara’s / Birthday / Dear / Joan / just / finished / our / gigot / flageolets / remember / the / Linden / tree? / Chris / JJ / Kynaston / Bjarne / bon / Dane / blond / black / blue / thinking / of / speaking / of / looking / at / you / see / you / wagon-lit / samedi. Signed J. J. Mitchell in pencil at the lower left. 365 x 236 mm. (14 3/8 x 9 1/4 in.)

PROVENANCE: Acquired from the artist by a private collector, New York; Thence by descent.

LITERATURE: Jenni Quilter, ‘“Love Is the Condition of Arriving at Infinity”: Joan Mitchell and Poetry’, in Sarah Roberts and Katy Siegel, ed., Joan Mitchell, exhibition catalogue, San Francisco and Baltimore, 2021-2022, p.197.

Joan Mitchell once stated that ‘Music, poems, landscape, and dogs make me want to paint...And painting is what allows me to survive.’ The artist had a deep and abiding love of English and French literature and, in particular, poetry. She had grown up in a literary household in Chicago; her mother edited Poetry magazine and was a poet, writer and playwright herself, while the Mitchell home was often visited by such writers as Dylan Thomas, Thornton Wilder, T. S. Eliot and Edna St. Vincent Millay. At the age of ten, Mitchell had one of her own poems published in Poetry magazine.

Mitchell was close friends with a number of writers and poets, including John Ashbery, Samuel Beckett, Jacques Dupin, Frank O’Hara, Nathan Kernan, Pierre Schneider and James Schuyler. Her work was often directly inspired by poetry, and indeed she once described her painting as ‘more like a poem’. As she added, in a 1957 interview, ‘My art embodies the qualities that differentiate a line of poetry from a line of prose.’ In 1988 Mitchell collaborated with the poet Charles Hine on Smoke, a book of his verse illustrated with aquatints by the artist, while another collaborative project, Poems, with colour lithographs by Mitchell alongside poetry by Nathan Kernan, was to be her final work, appearing just before her death in 1992. As has been noted of the artist, ‘For Mitchell, poetry was a call across water, a model for hailing one another. It gave her a form in which to feel the world.’1

The present sheet is another of Joan Mitchell’s ‘poem pastels’ of 1975, and likewise incorporates a poem by J. J. Mitchell (no relation to the painter), who stayed with the artist at Vétheuil for several months between 1974 and 1975, during which time they collaborated on a series of pastel compositions featuring his poems. As Erin Kimmel has noted, the artist embarked on this group of pastels ‘when she was struggling to paint. Accustomed to switching modes when stuck, she asked J. J. Mitchell…a young writer who was moonlighting as her dog walker, confidant, and secretary of sorts, to use her mother’s Hermes typewriter to type up some of the poems he had written while staying at La Tour in Vétheuil. She took the pages and added pastel. Pleased with the result, she expanded the collection to include works that feature the poetry of other poet-friends, including Jacques Dupin, Pierre Schneider, and Chris Larson, as well as [James] Schuyler. Mitchell later objected to describing these works as collaborations. “I just took the poems,” she said.’2

In these distinctive works, it was usually the painter who directed where on the sheet of paper the typewritten poem should go; ‘In a letter to Xavier Fourcade, Mitchell referred to these [poem pastels] as “color abstracts” that respond to the “shape of the poem itself.”’3 In a letter to another poet, Karen Edwards, written at the end of 1975, Mitchell suggested that it was working on these ‘poem pastels’ that allowed her to return productively to painting: ‘Working with other people’s feelings – i.e. their poems, has helped a lot.’4

As Kimmel has written of the poet J. J. (John Joseph) Mitchell (1940-1986), ‘A younger member of the New York School, J. J. deftly chronicled daily life at La Tour in his poems, moving seamlessly between comedy and pathos. From the fits and starts of Mitchell’s creative process to the comings and goings of Jean Paul Riopelle to the wisdom of Mitchell’s cherished German shepherd, Iva, they track the entire reality of Mitchell’s newly consolidated life in the country, including the dark, alcohol-drenched intimacy she shared with J. J.’5

The present poem, Frank O’Hara’s Birthday, must have had a special significance for both Mitchells, who were each close friends of the poet and museum curator Frank O’Hara. Indeed, J. J. Mitchell was with O’Hara on the night of July 24th, 1966, when O’Hara was hit by a dune buggy on a beach on Fire Island in New York, dying the following day in hospital of internal injuries. Joan Mitchell later used the date of O’Hara’s death as the title of a suite of paintings dedicated to him.

As Sarah Roberts has pointed out, ‘A former partner of O’Hara’s, J. J. wrote light, crisp poems that often directly addressed Mitchell and her dogs, like affectionate notes to a friend.’6 His poem Frank O’Hara’s Birthday is addressed to the painter, and is a tender evocation of the time they were spending together at Vétheuil, as well as of memories which both artist and poet shared of O’Hara and of mutual friends, on a day that would otherwise have been a cause for celebration (‘black / blue / thinking / of / speaking / of / looking / at / you ’). Given the title of the poem, it is likely that it was written on or around March 27th, 1975, on what would have been O’Hara’s 49th birthday. Two further ‘poem pastel’ versions of Frank O’Hara’s Birthday, each with a different composition, are known7

Another example of Joan Mitchell’s and J. J. Mitchell’s ‘poem pastels’ from this 1975 series, entitled Blue, is today in the Museum of Modern Art in New York8. Three others, all from the collection of the artist’s friend Joseph Le Sueur, appeared at auction in New York in 20079, while another, entitled Drowned, was sold at auction in Philadelphia in 200410. A further ‘poem pastel’ by Joan Mitchell and J. J. Mitchell, entitled What Makes This, is in a private collection11

Seventeen of Joan Mitchell’s collaborative ‘poem pastels’, incorporating poems by both J. J. Mitchell and James Schuyler, were shown at the Tibor de Nagy Gallery in New York in 2002. As a New York Times review of the exhibition noted, ‘These paintings don’t necessarily illustrate the poems directly; in fact, in some cases it isn’t clear whether text or image came first. But more often than not the components share a mood.’12