Front cover:

Philips Koninck (1618-1688)

Panoramic Landscape with a Watermill No.15

Front cover:

Philips Koninck (1618-1688)

Panoramic Landscape with a Watermill No.15

I am, as ever, grateful to my wife Laura for her counsel, encouragement and patience during the period that I was working on this catalogue. I am also greatly indebted to the indefatigable members of Team SOFA – Alesa Boyle, Megan Corcoran Locke, Emma Ricci and Antonia Rosso – for their invaluable assistance in almost every aspect of preparing this catalogue and the accompanying exhibition. Andrew Smith has photographed all of the drawings to very high standards, and he and Alesa have been stalwart in the fundamental task of colour-proofing the catalogue images against the original artworks to ensure that they are as accurate as possible. In addition, I would like to thank the following people for their help and advice in the preparation of this catalogue and the drawings included in it: Deborah Bates, Babette Bohn, Marco Simone Bolzoni, Angus Broadbent, Julian Brooks, Jane Carter, Isabella Lodi-Fè Chapman, Cheryl and Gino Franchi, Alastair Frazer, Bert Meijer, Jean-Pierre Michel, Sebastien Paraskevas, Miriam di Penta, Sarah Bowler, Andrew Robison, Michel Shulman, Jennifer Tonkovich and Jack Wakefield.

Stephen Ongpin

Dimensions are given in millimetres and inches, with height before width. Unless otherwise noted, paper is white or whitish.

High-resolution digital images of the drawings, as well as framed images, are available on request, and are also visible on our website.

All enquiries should be addressed to Stephen Ongpin at Stephen Ongpin Fine Art Ltd.

82 Park Street

London W1K 6NH

Tel. [+44] (20) 7930-8813 or [+44] (7710) 328-627

e-mail: info@stephenongpinfineart.com

Between 28th January and 11th February 2025 only:

Tel. [+1] (917) 587-1183

Tel. [+1] (212) 249-4987

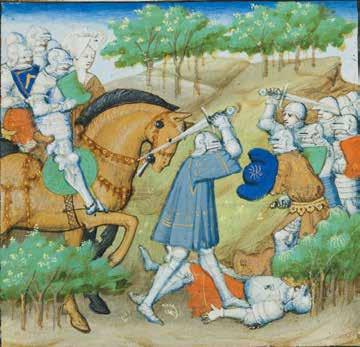

French, active between c.1430 and c.1466

Sir Gawain and his Nine Companions in Search of Lancelot

Illuminated manuscript on vellum, with framing lines in brown ink. The verso with fifteen lines of French text in Gothic script in brown ink, from Le livre du Lancelot du Lac1 87 x 92 mm. (3 3/8 x 3 5/8 in.)

PROVENANCE: Part of an illuminated manuscript of the Livre du Lancelot du Lac commissioned from Jean Haincelin in 1444 by Prigent VII de Coëtivy, Château de Taillebourg and Champtocé-sur-Loire; Probably by descent to his widow, Marie de Laval, Baronne de Retz; The manuscript subsequently broken up, probably in the 16th century, and the miniatures dispersed; The present sheet part of a group of thirty-four miniatures from the Livre du Lancelot du Lac bound into a red Morocco album, by the middle of the 19th century; Joachim Napoléon Murat, 5th Prince Murat, Paris and the Château de Chambly, Oise; By descent to his widow, Marie Cécile Ney d’Elchingen, Paris; The album purchased from her estate by Wynne R. H. Jeudwine, London, and the contents offered for sale individually in 1962; Christopher Pease, 2nd Baron Wardington, Wardington Manor, Oxfordshire; Anonymous sale (‘The Property of a Gentleman’), London, Sotheby’s, 13 December 1965, part of lot 171 (fourteen miniatures from the Livre du Lancelot du Lac, the present sheet as No.2, bt. Maggs); Maggs Bros. Ltd., London; Anonymous sale, London, Sotheby’s, 8 July 1970, lot 22 (bt. T. R. Lacey); Anonymous sale, London, Christie’s, 21 June 1978, lot 260 (bt. De Kesel); Private collection, Belgium; Anonymous sale, London, Sotheby’s, 8 July 2014, lot 17; Les Enluminures, Paris, Chicago and New York, in 2016; Ernst Boehlen, Bern.

EXHIBITED: London, W. R. Jeudwine at the Alpine Club Gallery, Early Fifteenth Century Miniatures, 1962, no.21.

Formerly known as the Chief Associate of the Bedford Master, the Dunois Master was a Parisian illuminator active in the middle of the 15th century, whose name derives from a book of hours made for Jean d’Orléans, Count of Dunois, which is now in the British Library in London. The Dunois Master is regarded as the finest pupil and assistant of the Bedford Master – named for his illumination of two manuscripts commissioned by John of Lancaster, Duke of Bedford – and succeeded him as the leading manuscript illuminator in Paris after the departure of the English from the city in 1436. Like the Bedford Master, the Dunois Master was familiar with the work of such Flemish artists as Jan Van Eyck and Robert Campin, whose influence can be seen in his illuminations. He was employed at the court of King Charles VII, for such important patrons as the aforementioned Jean de Dunois, Jouvenel des Ursins and Etienne Chevalier, and is thought to have also painted a large altarpiece for Notre-Dame. Regarded as one of the leading figures in the field of 15th century French courtly manuscript illumination, the Dunois Master enjoyed a relatively long career until the 1460s. Recent scholarship has posited that the Dunois Master was one Jean Haincelin, who is recorded as an ‘enlumineur’ in Paris in 1438 and 1448. Haincelin may have been the son of the early 15th century Alsatian illuminator Haincelin von Hagenau, who has in turn been tentatively identified as the Bedford Master.

This beautifully preserved cutting is thought to have come from an illuminated manuscript once owned by the Breton nobleman and soldier Prigent VII de Coëtivy (1399-1450), who served Charles VII as Admiral of France from 1439 to 1450. In 1444 Prigent de Coëtivy paid ‘Hancelin’ – assumed to be Jean Haincelin – the large sum of ninety livres, seventeen sous and six deniers tournois for three illuminated manuscripts; a Roman de Tristan, a Roman de Guiron le Courtois and a Livre du Lancelot du Lac. The present sheet comes from the last of these, which is part of an early 13th century French literary cycle of Arthurian chivalric episodes of unknown authorship, which is known in modern terms as the Vulgate Cycle or the Lancelot-Grail Cycle. Although the manuscript of the Livre du Lancelot du Lac commissioned by Prigent de Coëtivy contained over 150 miniatures, it seems to have been broken up as early as the

16th century, and only thirty-four of the miniatures are known today. The extant miniatures from the Livre du Lancelot du Lac are very similar in style, technique and appearance to those which decorate the companion volume of the Roman de Guiron le Courtois, also commissioned by Prigent de Coëtivy from Haincelin, which remains intact and is in the collection of the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris2.

The scene from the Livre du Lancelot du Lac depicted here shows the Arthurian knight Sir Gawain and his companions, who, having met a weeping damsel on a horse, are led by her to a nearby valley where a brave knight is fighting against ten soldiers. The knight has collapsed onto the ground, and Gawain’s companions take on the attackers, who eventually run away.

By the middle of the 19th century, thirty-four miniatures from the Livre du Lancelot du Lac, including the present sheet, had been bound into an album, with an unidentified coat of arms on the cover, which later belonged to Joachim Napoléon Murat, 5th Prince Murat (1856-1932). The album remained with his widow, Marie Cécile Ney d’Elchingen (1867-1960) until her death, and was purchased from her estate by Wynne Jeudwine (1920-1984), a London dealer in drawings, prints and books who exhibited all thirty-four miniatures in a selling exhibition of Early Fifteenth Century Miniatures at the Alpine Club Gallery in London in 1962. The present sheet was probably acquired at that time by the noted collector of maps and atlases Christopher Henry Beaumont Pease, 2nd Baron Wardington (1924-2005), who purchased fourteen of the Livre du Lancelot du Lac miniatures.

Less than a quarter of the miniatures by the Dunois Master from the manuscript of Lancelot du Lac have survived to this day. One of the miniatures is now in the McMullen Museum of Art at Boston College3, while three others are in the collection of the Museo Civico Amedeo Lia in La Spezia4 and a further three are in the Beinecke Library at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut5. Other examples are today in the Liberna (Draiflessen) Collection in Mettingen and in a number of private collections. Four miniatures on vellum from the same manuscript were offered for sale by Maggs Bros. in 19666, while several others have appeared at auction in recent years7

2

Circle of ANTONIO DI PUCCIO PISANO, called PISANELLO

Verona or Pisa 1394-1455 Rome or Naples

Study of the Head of a Greyhound

Black and red chalk. Laid down. 245 x 363 mm. (9 5/8 x 14 1/4 in.)

Watermark: A face in the form of a sun with eight rays (close to Briquet 13941; probably Italian [Cibinio(?)], 1554).

PROVENANCE: Charles Molinier, Toulouse (Lugt 2917)1; Acquired from him or his heirs by Lucien Guiraud, Paris2; By descent to his widow; Her posthumous sale (‘Collection Lucien Guiraud’), Paris, Hôtel Drouot [Ader], 14-15 June 1956, lot 61 (as Pisanello); Anonymous sale, Paris, Christie’s, 1 April 2016, lot 4 (as follower of Pisanello); Peter Silverman and Kathleen Onorato, Paris.

LITERATURE: Maria Fossi Todorow, I disegni del Pisanello e della sua cerchia, Florence, 1966, p.176, no.357, illustrated pl.CXXIX, fig.357 (as not by Pisanello); Vittorio Sgarbi, ed., Rinascimento segreto, exhibition catalogue, Urbino, Pesaro and Fano, 2017, pp.104-105, no.39 (entry by Franco Moro).

EXHIBITED: Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale, Exposition de l’oeuvre de Pisanello: Médailles – dessins –peintures, 1932, p.57, no.146 (as Pisanello); Urbino, Palazzo Ducale, Sala del Castellare, Rinascimento segreto, 2017, no.39 (as Follower of Pisanello).

A painter, draughtsman and medallist, Antonio di Puccio, known as Pisanello, enjoyed a long and highly successful career. He was probably born and grew up in Verona, but nothing is known of his training or early life before 1424, when he appears in a document already described as a ‘distinguished painter’ (‘pictor egregius’). Pisanello worked in Verona, Pavia, Rome, Ferrara, Milan, Mantua and Naples and enjoyed the patronage of some of the most powerful and sophisticated courts in Italy, receiving important commissions from the Gonzaga in Mantua, the d’Este in Ferrara and Alfonso V of Aragon, King of Naples, as well as Filippo Maria Visconti, Duke of Milan, and Popes Martin V, Eugenius IV and Nicholas V. Despite his fame, however, very few of his paintings have survived to this day. Indeed, only four or five panel paintings and three frescoed mural compositions – two in churches in Verona and the other in the Palazzo Ducale in Mantua, all in poor condition – exist today from his oeuvre as a painter.

As a draughtsman, however, Pisanello is better known. Around four hundred drawings by Pisanello and his workshop are known today, of which by far the largest group is now in the Louvre. (Almost all of the Louvre drawings come from an album acquired by the museum in 1856 from the Milanese print publisher and dealer Giuseppe Vallardi.) The range and variety of extant drawings by Pisanello and artists of his circle allow for a closer understanding of the master’s working methods. When planning a composition, Pisanello ‘would employ his own ‘pattern’ drawings from stock, often very finished and beautiful – drawings above all of birds and animals – and also make new sketches for specific elements for the project in hand…Pisanello would also execute a series of finished studies on a particular theme. These would provide him with a corpus from which he could select one or more drawings to be used in the final painting, and which he could use again as workshop patterns in the future. Such drawings usually represent animals, drawn from life – for example hounds…and, above all, horses.’3

As has recently been noted, Pisanello ‘can be considered the most imaginative and versatile artist of the early Quattrocento, as his drawings show an unparalleled range of subjects and inventions. Around 400 sheets from his workshop have survived, and at least 100 of these are by Pisanello himself. Through his elegant and distinctive individual style, the figure of a master, separate from the members of the workshop, emerges for the first time.’4 However, there has long been scholarly debate around the extent of Pisanello’s drawn oeuvre5. The artist ‘had a large workshop, and he needed to be able to rely on its

members to be able to reproduce his motifs and his techniques. To this end they were trained, partly in the traditional way, by copying drawings. But Pisanello also appears to have taught his pupils to draw from life.’6

Pisanello was ‘one of the keenest observers and finest delineators of men’s features and animals’ forms that the art of the Western world has produced.’7 Many of his surviving drawings, and those of his school, are of animals that appear in larger works. This fine drawing of a greyhound, of exceptional quality, was long attributed to Pisanello himself. Greyhounds and other hunting dogs are found in a number of the artist’s paintings and drawings8, and a very similar head of a hound appears, albeit in reverse, in the foreground of Pisanello’s small panel painting of The Vision of Saint Eustace (fig.1), where it is depicted coursing a hare. Probably painted between 1438 and 1442, the painting is today in the National Gallery in London9. The position of the head of the hound in the present sheet is nearly identical to that of the dog in the painting, and both animals wear very similar collars.

Among the large corpus of surviving drawings by Pisanello and his circle are several studies of greyhounds and other dogs, some seemingly drawn from life and others taken from model books or copied from the work of earlier artists. These include a number of autograph drawings of greyhounds from the Vallardi album in the Louvre10, which also contains drawings of several other breeds by Pisanello11. An interesting comparison may also be made with a similar dog that appears in a drawing of three hounds chasing and devouring rabbits from the Vallardi album12. Drawn in pen and brown ink with watercolour on vellum, although in a manner somewhat more naïve and much less refined than the present sheet, the Louvre drawing was formerly attributed to Pisanello but is now given to the earlier Lombard painter and illuminator Michelino da Besozzo (c.1370-c.1455).

Given its undeniable quality, it is unsurprising that this 15th century drawing has long held an attribution to Pisanello, under whose name it was exhibited in Paris in 1932. The naturalistic representation of the muzzle of the greyhound, beautifully drawn in a subtle combination of black and red chalks, has something of the characteristics of a formal profile portrait, characterized by an innate nobility and dignity. The close study of the creature’s nose and ear and intensely focused sharp eye, as well as the finely drawn smooth coat and studded leather collar with a buckle, all point to an artist of considerable skill.

SPANISH SCHOOL

Circa 1550

A Decorated Initial V from an Antiphonary

Manuscript in red, blue and grey ink on vellum. Inscribed with part of a rubric [As]censione dni in red ink on the verso.

288 x 285 mm. (11 3/8 x 11 1/4 in.)

PROVENANCE: Maggs Bros. Ltd., London, in 1967; Anonymous sale, London, Sotheby’s, 24 June 1980, part of lot 16 (‘Two Very Large Decorated Initials, “V” and “S”, in elaborately ornamented red and blue with very detailed infilling and surround in both colours, cut from vellum leaves of an Antiphoner, portions of text and music on the verso (each approx. 295 mm. by 290 mm.) [Spain, c.1550]’ bt. Maggs); Maggs Bros. Ltd., London; Stuart Cary Welch, Jr., New Hampshire.

LITERATURE: London, Maggs Bros. Ltd., European Miniatures and Illumination: Bulletin No.5, April 1967, pp.51-53, no.37 (as ‘Spanish Illuminator, c.1550’).

The present sheet is one of a group of four matching ornamental initials from a large 16th century Spanish antiphonal manuscript that were offered for sale by Maggs Bros. in London in 19671. This cutting of an initial V, with traces of text and ruling for music, incorporates a foliate pattern in red and blue outlined with white, surrounded by a repeated pattern of circles with flower heads inside them. While the ornament of the present sheet and another from the group, with the initial A, is based entirely on circles, the other two cuttings, with the initials C and S, also incorporated lozenges. Indeed, the initial S adds squares to the design, creating a pattern quite reminiscent of Islamic ornament, which in turn would suggest a possible origin in southern Spain for the parent manuscript.

The reverse of this decorated initial V includes the rubric ‘[As]censione d[omi]ni’ (‘Ascension of the Lord’), so it is likely that this initial was meant to begin the introit lines ‘Videntibus illis elevatus est’ (‘When they saw him, he was lifted up’) or ‘Viri Galilaei, quid aspicitis in caelum’ (‘Men of Galilee, why are you looking up to heaven?’) in the text of the antiphonary. The very large scale and repeated ornament of the present sheet, as well as the three related initials, is typical of late medieval and 16th century Spanish liturgical choirbooks. They may be likened in particular to the ‘letras de compas para illuminadores’ (or ‘casos quadrados’) (fig.1) illustrated by Juan de Yciar in his famous writing book Arte Subtilissima, published in Spain in 15502, and may thus be tentatively dated to around the same time.

This cutting was once part of the collection of Stuart Cary Welch (1928-2008), a noted scholar and curator of Islamic and Indian art who had a long professional relationship with both the Harvard University Art Museums in Cambridge (MA) and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

Sant’Angelo in Vado 1529-1566 Rome

Design for a Pendentive with Saint Luke

Pen and brown ink and brown wash, with touches of white heightening, and squared in red chalk, within brown ink framing lines, on blue paper. The verso with figure studies in brown ink. 147 x 142 mm. (5 3/4 x 5 5/8 in.) at greatest dimensions.

PROVENANCE: Purchased in Florence around 1830 by the Rev. John Sanford, London and Florence1; By descent to his daughter Anna Horatia Caroline and her husband Frederick Henry Paul Methuen, 2nd Baron Methuen, Corsham Court, Wiltshire; By descent to Paul Ayshford Methuen, 4th Baron Methuen, Corsham Court, Wiltshire; Thence by family descent until 1996; Sale (‘Drawings from the Collection at Corsham Court’), London, Sotheby’s, 3 July 1996, lot 17; Private collection, Europe.

LITERATURE: John Gere, Taddeo Zuccaro: His Development Studied in his Drawings, London, 1969, p.65, p.129, no.25, pl.60; John Gere, Dessins de Taddeo et Federico Zuccaro, exhibition catalogue, Paris, Musée du Louvre, 1969, p.26, under no.13; Cristina Acidini Luchinat, Taddeo e Federico Zuccari: fratelli pittori del Cinquecento, Milan and Rome, 1998-1999, Vol.I, p.50, fig.14, p.57, note 22; Zdeněk Kazlepka and Martin Zlatohlávek, Magie kresby / The Magic of Drawing Italska Kresba Vrcholné Renesance a Manýrismu v Ceských a Moravských Verejných Sbírkách / Italian Drawings of the High Renaissance and Mannerism from Bohemian and Moravian Public Collections, exhibition catalogue, Olomouc and Kroměříž, 2023, pp.162-165, pp.303-304, under no.87.

Among the most gifted Mannerist artists working in Rome, Taddeo Zuccaro had a relatively brief career, lasting less than twenty years. He was a superb draughtsman, whose drawings reveal a highly original and inventive artist. His figure studies, in particular, are drawn with a vitality and exuberance that ranks them among the most remarkable graphic statements of Roman Mannerism. The present sheet is a study for what is arguably Zuccaro’s most important surviving work, the fresco decoration of the Mattei Chapel in the church of Santa Maria della Consolazione in Rome, painted between 1553 and 1556. The decoration of the small chapel was the result of a commission from the nobleman Jacopo Mattei, who several years earlier had engaged the young Zuccaro to paint the façade of the Palazzo Mattei in Rome. As Giorgio Vasari records, ‘M. Jacopo Mattei, having caused a chapel to be built in the Church of the Consolazione below the Campidoglio, allotted it to Taddeo to paint, knowing already how able he was; and he willingly undertook to do it, and for a small price, in order to show certain persons, who went about saying that he could do nothing save façades and other works in chiaroscuro, that he could also paint in colour. Having then set his hand to that work, Taddeo would only touch it when he was in the mood and vein to do well, spending the rest of his time on works that did not weigh upon him so much in the matter of honour; and so he executed it at his leisure in four years…The whole work, which was uncovered in the year 1556, when Taddeo was not more than twenty-six years of age, as held, as it still is, to be extraordinary, and he was judged by the craftsmen at that time to be an excellent painter.’2 Zuccaro must have produced a large number of preparatory drawings for this important commission, but only a few are known today.

This fine drawing is an early preparatory study for one of the four Evangelists (fig.1) painted by Taddeo Zuccaro on the pendentives of the vault of the Mattei Chapel3. The pendentives are very damaged today, and only three of them are still reasonably legible4. Since the frescoed Evangelists are halflength figures, this squared drawing of a full-length seated figure of Saint Luke, as Gere has noted, ‘can reasonably be identified as a discarded design for one of the pendentives on the entrance-wall’5 of the chapel. Another preparatory drawing for the same pendentive figure of Saint Luke, which also shows the figure full-length and is very similar in stylistic terms to the present sheet (fig.2), is in the collection of the Archdiocesan Museum in Kroměříž in the Czech Republic6

Four other preparatory drawings by Taddeo related to the Evangelists in the Mattei Chapel are known. A drawing for the full-length pendentive figure of Saint John is in the Louvre7, while a pen and wash

study of a half-length figure of Saint Matthew with an Angel appears on the verso of a drawing in the Uffizi8. What seems to be another early study for the Saint Matthew pendentive is in the collection of the Kunsthaus in Zurich9. A sheet of red chalk figure studies of full-length Evangelists, on the verso of a drawing of a sibyl in a private collection10, may also be related to the Mattei Chapel pendentives. As Julian Brooks has pointed out, based on the surviving drawings for the pendentives, ‘it is obvious that Taddeo initially wished to portray the evangelists full-length, although in the end he decided to show only their upper bodies and heads. Taddeo’s struggles to overcome the problem of showing the full body from below – while keeping the head visible and including an attribute… – are evident.’11 Certainly, the visually striking pose of the Evangelist in the present sheet, like those of the saints in the related drawings in the Louvre and in Kroměříž, is quite different from the much more restrained half-length figures that were eventually frescoed in the chapel.

Among stylistically comparable drawings by Taddeo Zuccaro is a study of an angel seated on a cloud, likewise drawn in pen and brown ink and wash on blue paper, in the collection of the Raclin Murphy (formerly Snite) Museum at the University of Notre Dame in Indiana12, and a drawing of Saint Paul Restoring Eutychus to Life in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York13. Also similar in medium and technique is a drawing of Two Youths Asleep in a Landscape in the Kunsthaus in Zurich14, which is a study for another fresco in the Mattei Chapel, as well as a Seated Sibyl in the Hamburger Kunsthalle in Hamburg15 and a drawing of a Roman soldier in the Biblioteca National in Rio de Janeiro16, both of which can also be related to the same commission.

The studies of arms and torsos drawn in brown ink on the verso of the present sheet may likewise be tentatively related to the Mattei Chapel decorations, and in particular the vault fresco of The Arrest of Christ (fig.3)17. When the sheet is turned 180 degrees, the study of a bent arm near the top edge of the verso can perhaps be regarded as a first idea for the arm of Saint Peter, holding a knife and attacking the fallen Roman soldier Malchus, near the centre of the painted composition. This figure also appears in Taddeo’s more elaborate compositional drawing for The Arrest of Christ, in the Kupferstichkabinett in Berlin18

Sant’Angelo in Vado c.1540/41-1609 Ancona

The Submission of the Emperor Frederick Barbarossa before Pope Alexander III in Venice

Pen and brown ink and brown wash, over an underdrawing in black chalk, on varnished (or oiled?) paper. Numerous additions and corrections inserted by the artist into the composition on separate pieces of paper.

528 x 458 mm. (20 3/4 x 18 in.)

PROVENANCE: Anonymous sale, London, Sotheby’s, 8 December 1972, lot 28; Ian Woodner, New York; Thence by descent; The posthumous Woodner sale, London, Christie’s, 7 July 1992, lot 18; Anonymous sale, London, Sotheby’s, 22 April 1998, lot 27; James Fenton, New York.

LITERATURE: George R. Goldner, Master Drawings from the Woodner Collection, exhibition catalogue, Malibu and elsewhere, Fort Worth and Washington, D.C., 1983-1984, pp.68-69, no.25; Roger Ward, ‘Washington D.C., Master Drawings from the Woodner Collection’ [exhibition review], The Burlington Magazine, April 1984, pp.251-252, fig.105; George R. Goldner, European Drawings 1: Catalogue of the Collections. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Malibu, 1988, p.132, under no.55; E. James Mundy, Renaissance into Baroque: Italian Master Drawings by the Zuccari 1550-1600, exhibition catalogue, Milwaukee and New York, 1989-1990, pp.260-263, no.88; William M. Griswold and Linda Wolk-Simon, SixteenthCentury Italian Drawings in New York Collections, exhibition catalogue, New York, 1994, p.95, under no.85; Cristina Acidini Luchinat, Taddeo e Federico Zuccari: fratelli pittori del Cinquecento, Milan and Rome, 1998-1999, Vol.II, p.150, note 80; Dominique Cordellier et al, De la Renaissance à l’Age baroque: Une collection de dessins italiens pour les musées de France, exhibition catalogue, Paris, 2005, p.96, under no.60; Ursula Verena Fischer Pace, Italian Drawings in the Department of Prints and Drawings, Statens Museum for Kunst: Roman Drawings before 1800, Copenhagen, 2014, p.53, under no.25; Rhoda Eitel-Porter and John Marciari, Italian Renaissance Drawings at the Morgan Library and Museum, New York, 2019, p.382, under no.123.

EXHIBITED: Malibu, J. Paul Getty Museum, Fort Worth, Kimbell Art Museum, and Washington, D.C., National Gallery of Art, Master Drawings from the Woodner Collection, 1983-1984, no.25.

This very large and complex drawing – drawn on several sheets of paper, and with numerous pentimenti and corrections inserted by the artist on separate pieces of paper – is a working compositional study for Federico Zuccaro’s monumental painting of The Submission of Emperor Frederick Barbarossa before Pope Alexander III (fig.1) in the Sala del Maggior Consiglio of the Palazzo Ducale in Venice1. Begun around 1582, the painting, over six metres in height, was not completed until the artist made a return visit to Venice more than twenty years later, in 1603.

The event depicted in this drawing took place in front of the Basilica of San Marco in Venice in July 1177 and marked the reconciliation of the Holy Roman Emperor and the Pope after a long period of conflict between the two men, arising from the Pope’s excommunication of Frederick in 1160. Following the capture of the Emperor’s son Otto by the Venetian fleet, Doge Sebastiano Ziani was able to bring Pope Alexander III and the Emperor Frederick Barbarossa together in Venice to establish peace. Zuccaro’s canvas depicts the Pope standing beneath a baldacchino or canopy in front of San Marco, his foot on the neck of the prostrate Emperor, who kisses the Pope’s other foot, and shows the Piazzetta beyond and the island and church of San Giorgio Maggiore in the distance.

The present sheet is quite close to the composition of the final canvas, although it displays numerous pentiments and, in particular, alters the length of the façade of the Palazzo Ducale. As the scholar Roger Ward has noted, this large drawing is ‘of great historical importance [and] technical complexity…It is vital to an understanding of the function of this drawing to realise that it was not made on a single sheet, but on

several smaller pieces of paper that have been joined. Furthermore, some figures or whole groups of figures were drawn on separate fragments and then, like giant pentimenti, stuck down onto the principal sheet (perhaps most easily discernible in reproduction is the soldier seated in the bottom left corner). Also the Doge’s Palace was significantly altered by bleeding out most of its visible extension beyond the façade of San Marco. In other words, this drawing, though made well beyond the invenzione stage, is nevertheless a record of work still in progress.’2 Indeed, the present sheet allows for a fascinating insight into Zuccaro’s artistic process as he developed the composition of this significant public commission.

Several other preparatory drawings by Zuccaro for The Submission of Emperor Frederick Barbarossa before Pope Alexander III have survived. Perhaps the earliest drawing related to the project is a large horizontal composition that appeared at auction in 20103, which depicts the scene within an elaborate architectural setting, viewed from the Piazzetta with the Torre dell’Orologio in the background and San Marco at the right of the scene. However, the drawing’s horizontal orientation would have been unsuitable for the narrower vertical space intended for the painting. It has been suggested, therefore, that the drawing may represent a first idea by Federico for the composition, drawn either before he knew precisely the dimensions of the space to be painted, or perhaps as an attempt to persuade the Senate to allow him to decorate a much larger, horizontal space in the Sala del Maggior Consiglio. The next drawing in the sequence is a compositional study in the Pierpont Morgan Library in New York4, which likewise differs from the final painting in showing the scene from the other side, looking towards the Torre dell’Orologio with the façade of San Marco at the right.

Each of the other known compositional drawings for The Submission of Emperor Frederick Barbarossa before Pope Alexander III depict the scene as it was actually painted; that is, looking towards the lagoon with the façade of San Marco at the left edge of the composition5. A compositional study in pen and ink for The Submission of Emperor Frederick Barbarossa before Pope Alexander III is recorded in a private English collection in 19706, while another compositional drawing is today in the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Lille7. A third, highly finished drawing, very close to the present sheet in composition and slightly larger (fig.2), is in the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles8. A study for the group of spectators at the left edge of the composition is in the Statens Museum for Kunst in Copenhagen9, while a handful of chalk studies for individual figures in the painting are also known10

A studio copy of either the present sheet or the closely related Getty drawing is at Christ Church in Oxford11

Attributed to ANNIBALE CARRACCI

Bologna 1560-1609 Rome

The Head of a Young Child

Red chalk. A small made-up area on the upper forehead of the child and another above the child’s proper right eyebrow and the upper left side of his head. Laid down on an 18th century English (Richardson) mount, inscribed Annibale. in brown ink in the lower margin. The reverse of the mount inscribed with Richardson’s shelfmarks B.10. / AA.60. / 61. / A.22. / f in brown ink, and, in a different hand, the Saint-Morys sale code 41 and 1D. L. 64 (Lugt 3510) in brown ink.

137 x 118 mm. (5 3/8 x 4 5/8 in.) [sheet]

PROVENANCE: Jonathan Richardson, Senior, London (Lugt 2184 and on his mount); Probably his posthumous sale, London, Covent Garden, Christopher Cock, 22 January to 8 February 1747; Charles Paul Jean-Baptiste de Bourgevin Vialart de Moligny, Comte de Saint-Morys, Paris and Hondainville (with his collector’s mark [Lugt 474] stamped three times); By descent to his son, Charles Étienne Bourgevin Vialart, Comte de Carrière, London (with the related collector’s mark C.D.C. [Lugt 525]); His sale (‘The Collection of Drawings, The Property of Count de Carriere’), London, Henry Phillips, 10-14 June 1797, part of lot 64 (‘Fifteen, A. Sacchi &c.’, bt. Legoux for 7s.); Art market, France, in c.2006; Private collection, France.

LITERATURE: Julian Brooks and Casey Lee, ‘The Identification of the “Pseudo-Crozat” Mark (Lugt 474)’, Master Drawings, Autumn 2021, pp.404-405, figs.20-21 (as Italian School Seventeenth-Century, location unknown); Transcription of Auctioneer Henry Phillips’s Annotated Catalogues of the 1797 and 1799 Sales of the Drawings of the Comte de Carrière [https://masterdrawings.org/content/digitalresources/], p.7, fig.11.

As Daniele Benati has pointed out, although he never married or had children of his own, ‘Annibale [Carracci] was the author of several enchanting and extraordinarily tender images of children.’1 The present sheet would appear to be a study for the head of the Christ Child in Annibale’s devotional canvas of The Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine, a youthful work painted in c.1585-1587 and today in the Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte in Naples2. Commissioned by Duke Ranuccio Farnese in Parma and then sent by him to Rome for his younger brother Cardinal Odoardo Farnese, the painting was for many years kept in the Palazzo Farnese in Rome but by 1680 is recorded in the Palazzo del Giardino in Parma. However, it had lost its attribution to Annibale Carracci by the time it entered the collections at Capodimonte at the beginning of the 19th century, and was only identified as an early work by him, by the art historian Ferdinando Bologna, in 1956. The painting reveals the particular influence of Correggio on Annibale; as has been noted, ‘At this age the young artist admired Correggio’s work over anything else, even Raphael’s, and his drawings and paintings of the mid-1580s attest to this devotion.’3 As Donald Posner has described the Capodimonte Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine, ‘[it] is perhaps Annibale’s purest re-creation of Correggio’s visual poetry. The intimacy and melodious flow of the forms, the touchingly sweet, gentle types, and the sfumato, creating a unifying, all-enveloping, warm and golden atmosphere, amount to a kind of Correggesque tour de force ’4

A very similar head is also found in the Christ Child in another early painting by Annibale Carracci; a Holy Family in the collection of the National Trust at Tatton Park in Cheshire5 that is likewise datable to c.1585. Among stylistically and thematically comparable drawings by Annibale is a small red chalk study of A Child Held in the Arms of its Mother in the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford6

The earliest known owner of this drawing was the English portrait painter, author and connoisseur Jonathan Richardson the Elder (1667-1745), whose mark is found at the lower left corner of the sheet. The drawing is also laid down on a typical Richardson mount, with the collector’s handwritten attribution ‘Annibale’ at the bottom7. Richardson’s remarkable collection of nearly five thousand drawings, mostly Italian works of the 16th and 17th centuries, was assembled over a period of some fifty years, and

included around four dozen drawings by or attributed to the Carracci. The scholar Catherine Loisel, who has accepted the attribution of this drawing to Annibale Carracci, has suggested that the two small made up and restored areas on the present sheet were done by Richardson when the drawing was mounted for him.

This drawing also bears the distinctive collector’s mark (Lugt 474) that has been recently identified as that of Charles Paul Jean-Baptiste de Bourgevin Vialart, Comte de Saint-Morys (1743-1795), and which was applied on drawings acquired by him after he went into exile in England in September 1790, during the French Revolution, and until his death five years later8. After Saint-Morys’s death, the collection of drawings, numbering over three thousand sheets, was inherited by his only son, Charles Étienne Bourgevin Vialart de Saint-Morys, Comte de Carrière and later Comte de Saint-Morys (1772-1817)9, who sold them at auction in two sales held in London in 1797 and 1799. It is thought that the Lugt 474 stamp was applied to the drawings in the Saint-Morys collection before the 1797 sale, at which time a code written in ink was also added to the versos of the drawings or their mounts. On the present sheet, the code ‘1D. L. 64’ indicates that this drawing was sold on the first day of the auction (10 June 1797), as part of lot 64, which contained fifteen drawings by different artists10.

The unidentified collector’s mark C.D.C. (Lugt 525) stamped on the present sheet is also found on a very small number of Italian and Netherlandish drawings, all of which also bear the Lugt 474 mark. Interestingly, each of the nine known drawings that have both the Lugt 474 (floral ‘C’) and Lugt 525 (‘C.D.C.’) marks were sold as part of lots 63 (containing twelve drawings) and 64 (fifteen drawings, including the present sheet) on the first day of the 1797 sale of the Comte de Carrière’s collection in London. It has been suggested that the C.D.C. stamp may have been a proposed collector’s mark applied to some of the drawings at the time of the sale. As Julian Brooks and Casey Lee have pointed out, in the present sheet ‘the floral “C” mark was stamped haphazardly no fewer than three times, twice without ink. What could be the purpose of this, and what could be the intention of the “C.D.C” mark?... Is it possible that these lots [ie. lots 63 and 64 of the 1797 sale] were “guinea pigs” for testing how the mark would look, both as a dry stamp and an inked stamp, and that the “C.D.C” mark was presented as an alternative, subsequently rejected option? It seems unlikely that a French aristocrat would propose a “C.D.C” mark for the Comte de Carrière, but might an English auction house employee have done so? At least part of the mystery continues.’11

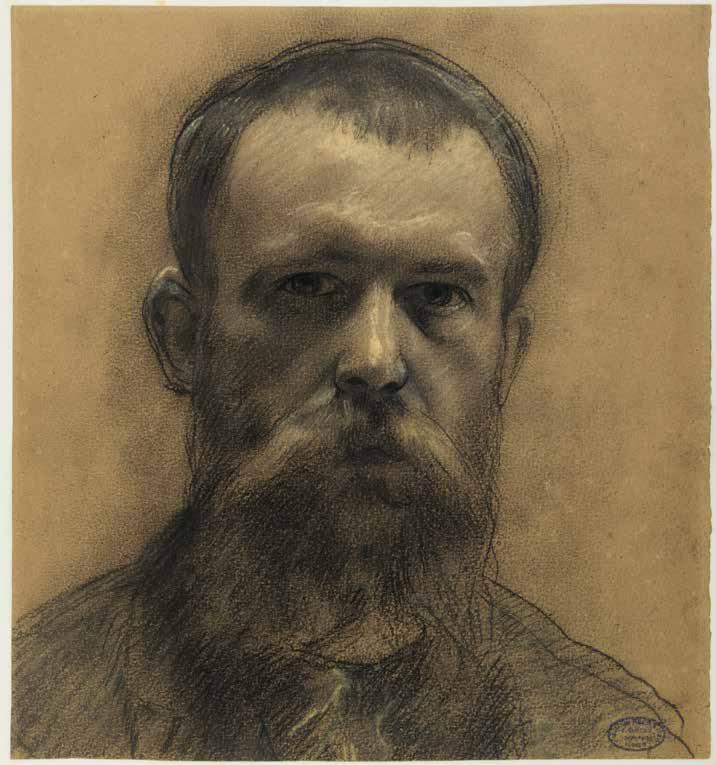

AGOSTINO CARRACCI

Bologna 1557-1602 Parma

Recto: A Wooded Landscape with a Man Resting by a Path Verso: Nine Studies of Pendants and a Sketch of a Spider

Pen and brown ink and brown wash. Inscribed Titiaen in brown ink on the verso. 213 x 287 mm. (8 3/8 x 11 1/4 in.)

PROVENANCE: Anonymous sale, New York, Sotheby’s, 12 January 1990, lot 21 (as Annibale Carracci); Anonymous sale, London, Christie’s, 2 July 1991, lot 264 (as Agostino Carracci); Pierre de Charmant, Geneva; His sale, Paris, Christie’s, 21 March 2002, lot 46 (as Attributed to Agostino Carracci); Anthony Powell, London1

Perhaps the least well known of the three Carracci, Agostino Carracci has long been overshadowed by his more famous younger brother Annibale, who was three years his junior, and his cousin Ludovico, who was two years older. He is best known today as one of the finest Italian engravers of the 16th century, with an oeuvre of over two hundred prints, many of which were after the work of other artists. As a painter, Agostino studied with Prospero Fontana and Bartolomeo Passarotti, and was also trained as an engraver in the studio of Domenico Tibaldi, producing his first engravings in the early 1580s. Agostino worked alongside Annibale and Ludovico on the frescoed friezes of the Palazzo Fava in Bologna, completed in 1584. By now firmly established as a successful printmaker, Agostino also received a handful of commissions for altarpieces, such as a Virgin and Child with Saints painted in 1586 for a church in Parma. Following a stay to Venice, he again collaborated with his brother and cousin on the decoration of the Palazzo Magnani in Bologna around 1590. A few years later he completed an altarpiece of The Last Communion of Saint Jerome for the Bolognese church of San Girolamo alla Certosa, a painting described by the 17th century biographer Giovan Pietro Bellori as the artist’s masterpiece.

In the middle of the 1590s Agostino joined his brother Annibale in Rome, where the latter was engaged on the decoration of the galleria of the Palazzo Farnese. While the bulk of the decorative scheme of the Farnese Gallery was the work of Annibale, Agostino was responsible for the design and execution of two prominent frescoes on the long walls of the room; the Cephalus and Aurora and the so-called Galatea. After an argument with his brother, however, Agostino left Rome in 1599 for Parma, where he was commissioned by Duke Ranuccio Farnese to paint frescoes for the Palazzo del Giardino, but he died before the project was completed.

A prolific draughtsman, Agostino Carracci worked mainly in pen and ink. As Rudolf Wittkower has noted, ‘This is not astonishing, since he was first and foremost an engraver, and the careful engraver’s technique, characterized by the ample use of parallel and cross-hatching, remains apparent in his drawings throughout his whole life…[The 17th century Bolognese biographer Carlo Cesare] Malvasia, no doubt on good authority, tells us of his tireless and penetrating work as a draughtsman: how he cleared up step by step every detail of his compositions, how he made an over life-size model of an ear or clay models of arms and legs from corpses he had himself dissected to serve as reference when needed.’2 Nevertheless, Agostino does not seem to have valued his drawings particularly highly, to judge from Malvasia’s comment that he once saw one of the artist’s drawings in the possession of another Bolognese painter which the latter had saved from Agostino, who was about to use it to wipe clean a cooking pan.

According to early sources, both Annibale and Agostino Carracci drew landscapes outdoors, although very few drawings can be specifically related to landscape paintings by either artist. The practice of landscape painting and drawing was a significant part of the work of the Carracci studio and was carried through to the teachings of the Accademia degli Incamminati, the academy that the three Carracci established in Bologna in the early 1580s. As Clare Robertson has written of the Carracci, ‘They seemed

to have made numerous drawings for landscapes from the very beginning of their careers. This activity must be seen in the wider context of their general interest in drawing from nature, and their interest in Venetian forms of art…part of the curriculum of the Carracci Academy was to go out into the country and make landscapes.’3 Landscape paintings and drawings by Agostino are mentioned in many Seicento inventories, and a volume of landscape studies by both Agostino and Annibale was part of a very large group of some six hundred drawings by the Carracci assembled by the 17th century Roman antiquarian Francesco Angeloni. While numerous landscape studies have been attributed to each artist, it seems that, of the two brothers, Agostino was in his day regarded as more dedicated to the practice of landscape drawing. In a 1603 funeral oration for Agostino, Luca Faberio noted of the artist and fellow members of the Carracci academy that ‘they drew hills, fields, lakes, rivers, and anything else that was beautiful or arresting in sight.’4

As Clovis Whitfield has observed, ‘In contrast with Annibale, Agostino in his landscape drawings reveals a concern with a careful definition of space and perspective; in many ways his brother’s manner was more direct, looking at individual planes and single motifs.’5 Agostino’s landscape studies owe much to the example of drawings and prints by such 16th century Venetian artists as Titian and Domenico Campagnola, and several of his drawings of this type have long been attributed to the latter in particular. The present sheet, which bears an old attribution to Titian, exemplifies the influence of the Venetian landscape tradition on Agostino, whose drawings were in turn influential on the succeeding generation of painters such as Domenichino and Giovanni Francesco Grimaldi. Among stylistically comparable pen drawings by Agostino Carracci is a Landscape with the Flight into Egypt(?) in the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris6 and a Rocky Landscape with Figures in the collection of the Dukes of Devonshire at Chatsworth7, as well as a Landscape with Saint Francis in the Städelsches Kunstinstitut in Frankfurt8

A number of Agostino’s prints from the early 1580s are of decorative designs for friezes or coats of arms, and several of his drawings include quick sketches of decorative ornaments akin to the studies of what appears to be jewellery on the verso of the present sheet. The schematic study of a spider on the verso is also echoed in a handful of drawings by the artist, such as a sheet of studies in the Royal Collection at Windsor Castle, which includes a quick sketch of a crab9.

FRANCESCO BRIZIO

Bologna c.1574-1623 Bologna

A Vision of the Virgin and Child with Angels Appearing to Saint Jerome Pen and brown ink and brown wash, heightened with white, on buff paper, laid down on an 18th century English mount. Inscribed St Mathew, Julio Cesari(?) and Cosways stamp in pencil on the mount. Further inscribed Lady Sidmouth / Presented to Eliza Hobhouse 1842 in brown ink formerly at the top of the mount and now cut out and attached to the reverse of the mount. 344 x 235 mm. (13 1/2 x 9 1/4 in.)

PROVENANCE: Richard Cosway, Stratford Place, London (Lugt 628 and probably on his mount); Probably his posthumous sale (‘The Cosway Collection’), London, George Stanley, 14-22 February 1822 [lot unidentified]; Possibly Henry Addington, 1st Viscount Sidmouth, London and Richmond Park; His second wife, Marianne Townsend, Lady Sidmouth; Given by her to her goddaughter Eliza Hobhouse in 1842 (according to the inscription on the old mount); Possibly her brother, Henry Hobhouse, Hadspen House, Castle Cary, Somerset, and thence by descent in the Hobhouse family; Anonymous sale, London, Christie’s, 1 July 1997, lot 44; Private collection.

Francesco Brizio was a pupil of Bartolomeo Passarotti in Bologna before transferring at the age of eighteen to the Accademia degli Incamminati, the Carracci academy in Bologna. He learned the art of engraving from Agostino Carracci and developed into a talented printmaker, producing a number of engravings after works by Ludovico and Agostino Carracci, Parmigianino and Correggio. Following Agostino’s departure for Rome in 1597, Brizio seems to have taken over his printmaking business in Bologna. At the same time he began to work closely with Ludovico Carracci, whom he assisted on some major public commissions, notably the decoration of the Palazzo Fava in Bologna between 1598 and 1600 and the cloister of the monastery of San Michele in Bosco, completed in 1605. Brizio was given charge of the Carracci studio when Ludovico went to Rome in 1602, and among his earliest significant independent commissions was the fresco decoration of the Negri-Formagliari chapel in the Bolognese church of San Giacomo Maggiore, completed in 1602. Together with Leonello Spada and Lucio Massari, Brizio worked on the fresco decoration of the Palazzo Bonfioli Rossi in Bologna and the Oratorio della Santissima Trinità at Pieve di Cento. Other churches in Bologna decorated with frescoes, paintings or altarpieces by the artist include San Colombano, San Domenico, San Martino Maggiore, San Michele in Bosco, San Petronio and San Salvatore. Brizio painted decorative frescoes for other villas and palaces in Bologna and the surrounding area, and also worked in Modena and Cento. Towards the end of his life he worked on an extensive cycle of fresco decorations in the Palazzo Orlandini-Marescalchi.

In his brief account of Brizio’s career, the 17th century Bolognese biographer Cesare Malvasia noted the artist’s small-scale works in particular, which he praised for their ‘delicacy and grace’ (‘delicatezza e leggiadria’). By the end of the 18th century, however, Brizio had been almost forgotten as a painter, and when he was occasionally noted in documents it was mainly for his work as an engraver. It is only in the last two or three decades that Brizio’s work as a painter and draughtsman has been the subject of renewed scholarly attention.

Brizio’s drawings are, like his paintings, particularly indebted to the example of Ludovico Carracci. He had a distinctive manner of drawing, with an emphasis on the depiction of form through brown wash and white heightening to achieve a painterly effect, and the present sheet may be compared stylistically with such drawings by the artist as a Virgin and Child with Saints Francis of Assisi and Carlo Borromeo (fig.1) in the Hamburger Kunsthalle in Hamburg1, a Saint Benedict in Ecstasy in the Nationalmuseum in Stockholm2 and a Saint James the Greater and a Hermit Saint Kneeling Before a Statue of the Virgin and Child (fig.2) in the Albertina in Vienna3

The largest extant group of drawings by Francesco Brizio, amounting to around nine or ten sheets, is today in the Koenig-Fachsenfeld collection at the Staatsgalerie in Stuttgart. Other drawings by the artist are in the collections of the Harvard University Art Museums in Cambridge (MA), the Hessisches Landesmuseum in Darmstadt, the National Gallery of Scotland in Edinburgh, the Uffizi in Florence, the British Museum, the Courtauld Galleries and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, the Staatliche Graphische Sammlung in Munich, Christ Church in Oxford, the Louvre in Paris, the Biblioteca Nacional in Rio de Janeiro, the Fondazione Giorgio Cini in Venice and the Royal Collection at Windsor Castle.

This drawing bears the distinctive collector’s mark of the English portrait painter and miniaturist Richard Cosway RA (1742-1821), a leading artistic figure of the Georgian era. A noted connoisseur, collector and marchand-amateur, Cosway assembled fine collections of Old Master paintings, decorative arts, books, furniture, armour, sculpture and objects, as well as around 8,000 prints and some 2,700 drawings. Most of his drawings were acquired at auctions in London, and he had a particular penchant for Italian works of the 16th and 17th centuries and Flemish drawings of the 17th century. Cosway’s collection of drawings – which included groups of works by Correggio, Giulio Romano, Jordaens, Parmigianino, Michelangelo, Raphael, Rembrandt, Rubens, Titian and Van Dyck, among others – was much admired by such fellow collectors and connoisseurs as Sir Thomas Lawrence. (Despite himself assembling arguably the finest collection of Old Master drawings ever formed in England, Lawrence appears to have been quite envious of Cosway’s collection, to judge from his comments in a letter to Joseph Farington of 1811: ‘I have been out…to see Cosway’s Drawings, and I am returned most heavily depressed in spirit from the strong impression of the past dreadful waste of time and improvidence of my Life and Talent…’4) Stored in portfolios and albums, Cosway’s collection of prints and drawings were dispersed at auction over a period of eight days in February 1822, a few months after his death. Only a small percentage of Old Master drawings from Cosway’s collection have been identified today, however.

The present sheet may have been acquired at the Cosway sale in 1822 by Henry Addington, 1st Viscount Sidmouth (1757-1844). It is certainly known to have been in the possession of his second wife, the Hon. Marianne Townsend (d.1842), whom he married in 1823, the year after the Cosway sale. According to the inscription on the old mount, Lady Sidmouth in turn presented this drawing to her goddaughter Eliza Hobhouse in 1842, the year of the former’s death5

DANIEL DUMONSTIER

Paris 1574-1646 Paris

Portrait of Cardinal Jacques Davy du Perron

Red and black chalk. Inscribed LE CARDINAL DU PERRON and dated 1613 in brown ink at the top of the sheet. Traces of an erased inscription and date in black chalk near the centre right edge. Further inscribed J. Niel (Lugt 1944) in brown ink on the verso. 441 x 343 mm. (17 3/8 x 13 1/2 in.)

PROVENANCE: Philippe de Béthune, Paris and Selles-sur-Cher, and by descent to his son, Hippolyte de Béthune, Comte de Selles; Paul-Gabriel-Jules Niel, Paris (Lugt 1944, with his signature on the verso); Comte Alfred-Louis Lebeuf de Montgermont, Paris; His posthumous sale (‘Collection L. de M...’), Paris, Galerie Georges Petit, 16-19 June 1919, lot 230 (‘Dumonstier (Daniel). Le Cardinal du Perron. En buste, grandeur nature, de trois-quarts à gauche; il porte la barbe, est coiffé de la barrette et vêtu d’un costume orné de fourrure à col de lingerie. Dessin au crayon noir, sanguine et lavis. En haut, l’inscription, en lettres capitals: LE CARDINAL DU PERRON, 1613. Haut., 44 cent.; larg., 34 cent.’, bt. Lang for 7,000 francs); Private collection; Anonymous sale, (‘Provenant de la Collection de Madame B…’), Paris, Galerie Charpentier [Ader], 12 June 1959, lot 95; Private collection.

LITERATURE: Daniel Lecoeur, Daniel Dumonstier 1574-1646, Paris, 2006, p.96, no.27 (as location unknown).

The son of the portraitist Cosme Dumonstier and nephew of the artists Pierre and Etienne Dumonstier, Daniel Dumonstier worked mainly in Paris and enjoyed a long and successful career as a court painter and valet de chambre to King Henri IV and his successor, Louis XIII. Given lodgings in the Louvre, he made portrait drawings of both male and female members of the French royal family, the aristocracy and nobility, as well as prominent civil servants and many members of the upper classes. Dumonstier was friendly with such writers as François de Malherbe, Nicolas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc and Gédéon Tallemant des Réaux who described the artist as well-read and noted that he wrote poetry, spoke Italian and Spanish as well as French, and had a wicked sense of humour. Tallemant des Réaux added that, ‘When he painted people, he let them do whatever they wanted; sometimes he would just say to them, “Turn around”. He made them more beautiful than they were, and for this reason he said: “They are so foolish that they think they are like I make them, and pay me better for it.”’1 In 1626 Dumonstier was named peintre et valet de chambre to Gaston d’Orléans, the King’s younger brother. He assembled a fine library of books and manuscripts, part of which was acquired after his death by Cardinal Mazarin.

The present sheet can be situated within a long artistic tradition of portrait drawings executed in black, red and white chalks by French artists extending from Jean Clouet around 1500 to Daniel Dumonstier and Nicolas Lagneau in the first half of the 17th century. Dumonstier’s portrait drawings were generally larger in scale than those of earlier artists, at about half life-size and usually in three-quarter profile, and display a more pronounced interest in physiognomy and somewhat less of a focus on costume. The artist often dated his drawings; the earliest was done in 1600 and the latest are dated 1642 and 1644. The most important groups of drawings by Dumonstier are today in the Louvre and the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris, the Musée Condé in Chantilly, the Hermitage in St. Petersburg and the James A. de Rothschild Collection at Waddesdon Manor in Aylesbury, Berkshire.

The sitter of this portrait drawing, the French politician and Catholic cardinal Jacques Davy du Perron (1556-1618), was born to a noble family in Saint-Lô in Normandy. The son of a Protestant minister, he was raised and educated in Bern in Switzerland, where his family had fled to escape religious persecution. By 1578, however, du Perron seems to have renounced his Protestant upbringing and had

entered royal service at the court of King Henri III, by whom he was appointed lecteur de la chambre du Roy, and also served as a royal scholar of languages, philosophy and mathematics. He took religious orders in the late 1580s, and in 1591 was appointed Bishop of Évreux by the new King Henri IV, whom he instructed in the Catholic faith. In 1604 du Perron was created a cardinal by Pope Clement VIII, and served in Rome between 1605 and 1607, participating in two papal conclaves in quick succession and serving as cardinal priest of the church of Sant’Agnese in Agone. Du Perron sent many letters to Henri IV reporting on events at the papal court, and acted for the King as a mediator between the Republic of Venice and Pope Paul V. In 1606 the King named him Archbishop of Sens, although he did not take up the position until October 1608, a year after he had left Rome and returned to France. Du Perron died in 1618, at the age of sixty-three.

The present sheet was part of a large group of portrait drawings by Daniel Dumonstier assembled by the diplomat and ambassador Philippe de Béthune (1561-1649), the younger brother of the Duc de Sully, minister to King Henry IV. Béthune was a noted collector, and during the period of his appointment as the French ambassador in Rome between 1601 and 1605 he acquired a number of important Italian paintings. He is thought to have purchased several hundred drawings by Dumonstier from his family, shortly after the death of the artist, and at his own death in 1649 these passed to his son, Comte Hippolyte de Béthune (1603-1665), along with a library of manuscripts, letters and documents assembled in some 1,500 volumes. (As Daniel Lecouer has pointed out, the signatures and dates on many of the drawings by Dumonstier that he owned were scraped off by Hippolyte de Béthune in the middle of the 17th century, as is evident in the present sheet.) Having turned down an offer of 300,000 livres from Queen Christina of Sweden in 1652, Hippolyte de Béthune bequeathed the entire collection to King Louis XIV for the Bibliothèque du Roi. However, the drawings by Dumonstier were soon dispersed, and only fourteen portrait drawings by the artist from the Béthune collection are still today in the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris. Other Dumonstier drawings with the same provenance are in the Louvre, the Musée Condé at Chantilly, the Hermitage in St. Petersburg and at Waddesdon Manor in Berkshire.

The present sheet was among a group of very fine portrait drawings belonging to Jules Niel (18001872), the librarian at the Ministry of the Interior and a collector of prints and drawings. As Frits Lugt has noted, ‘at a time when they were still little appreciated, [Niel] was one of the first to collect excellent portraits drawn by the schools of Clouet and Dumonstier. Several were later bought from him by the Louvre, others are now in Bonnat’s collection.’2 In 1849 Niel sold three drawings by Dumonstier to the Louvre, while in 1848 and 1856 he published two volumes entitled Portraits de personnages français les plus illustrées, containing facsimile reproductions of some of the finest 16th century portrait drawings in French public collections. This portrait of Cardinal du Perron does not appear in the posthumous sale of Niel’s collection in Paris in March 1873, and is likely to have been acquired directly from Niel or his heirs by the French diplomat Comte Alfred-Louis Lebeuf de Montgermont (1841-1918), from whose estate it was sold at auction in 1919.

A copy of this drawing is at Waddesdon Manor3, while a related engraving by Michel Lasne4, shows the sitter in reverse, wearing different vestments and with the order of Saint-Esprit.

Florence 1583-1643 Florence

The Holy Family in the Carpenter’s Shop, with an Angel Pen and brown ink and blue wash, over an underdrawing in black chalk. Squared for transfer in black chalk, and with double framing lines in brown ink. Inscribed b[racci]a. 2 2/3 in brown ink at the lower left and b[racci]a. 3 1/3 in brown ink at the lower right. Further inscribed IvB (in ligature) I:o LXXV in brown ink in the bottom margin of the sheet. Inscribed by the artist ‘levar via quel cappanello di legnietto e in quell’ca[m]bio farvi che il cristo abbia cavato da u[n] / paniere de ferri il martello, le tanaglie, e de chiodi’ in brown ink on the verso.

213 x 171 mm. (8 3/8 6 3/4 in.) [image]

264 x 214 mm. (10 3/8 x 8 3/8 in.) [sheet]

PROVENANCE: Sigismondo (and Giovanni?) Coccapani, Florence (Lugt 2729), the mark embossed twice at the upper centre and lower centre of the sheet; By descent to Giovanni Coccapani’s son, Regolo Silverio Coccapani, Florence; Probably dispersed with the rest of the Coccapani collection in the third quarter of the 17th century; Anonymous sale, London, Christie’s, 7 July 1998, lot 79 (as Attributed to Sigismondo Coccapani); Anonymous sale, London, Phillips, 9 July 2001, lot 153 (as Attributed to Jacopo da Empoli, later changed to Coccapani); Jean-Luc Baroni Ltd./Colnaghi, London, in 2001; Alan Lam, Ipswich; Thence by descent.

LITERATURE: Miles Chappell, ‘The Assumption of the Virgin and the Holy Family in Joseph’s Workshop by Sigismondo Coccapani’, Notes in the History of Art, Summer 2004, pp.22-23, fig.3; Elisa Acanfora, Sigismondo Coccapani. Ricomposizione del catalogo, Florence, 2017, p.212, no.D144, p.193, under no.D75, p.209, under no.D131, illustrated p.76, fig.131 and p.234, fig.156.

EXHIBITED: London, Jean-Luc Baroni Ltd./Colnaghi, Old Master and Nineteenth Century Drawings, 2001, no.14.

The son of a goldsmith, Sigismondo Coccapani studied with the architect Bernardo Buontalenti and the painter Ludovico Cardi, known as Cigoli. He was one of Cigoli’s last pupils, and the only Florentine apprentice working closely with the master on his late Roman commissions; as Miles Chappell has noted, Coccapani ‘could be described as the most dedicated and also the most dependent of Cigoli’s disciples.’1 Between 1610 and 1612 he assisted Cigoli on the fresco decoration of the dome of the Cappella Paolina in the church of Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome, and also in the villa of Cardinal Scipione Borghese on the Quirinal hill. On his return to Florence Coccapani began his independent practice, and he seems to have worked almost exclusively in and around the city for the remainder of his career. Among Coccapani’s earliest known independent commissions were an altarpiece for the church of San Ponziano in Lucca, now lost, and a lunette fresco in the cloister of San Marco in Florence, painted in 1613. Four years later he completed a painting of Michelangelo Crowned by the Arts for the Casa Buonarroti in Florence, which was soon followed by an Adoration of the Magi for the church of Santa Maria in Castello in Signa, just outside the city. Between 1622 and 1623 he also painted a lunette fresco for the Casino Medico di San Marco. However, many of Coccapani’s documented works are no longer extant, such as the decoration of two chapels for the cathedral in Siena, commissioned by the Piccolomini family in 1638. The artist’s last known work is the decoration of the Cappella Martelli in the Florentine church of Santi Michele e Gaetano, begun in 1635 and completed in 1642.

Coccapani’s paintings show his debt to the manner of his master Cigoli, an influence that may also be seen in the relatively few surviving drawings by the younger artist that are known. Nevertheless, the fact that many more drawings by Coccapani must once have existed is shown by the comments of the Florentine collector and biographer Francesco Maria Niccolò Gabburri, who knew of an album of drawings by the artist that had been sold abroad; ‘un grosso libro, nel quale disegnò ogni sorta di animali, che riuscì cosa di gran pregio, il quale poi fù mandato oltre ai monti.’ The use of blue wash in many of

his drawings is a characteristic feature of Coccapani’s draughtsmanship which he adopted from the late compositional studies of Cigoli. Indeed, many of his drawings were once attributed to the elder artist, and many of the most Cigolesque drawings by Coccapani date from the early part of his career, when he was working with his master in Rome, and again at the start of his independent career in Florence.

This fine drawing by Sigismondo Coccapani is closely related to a less-finished version of a nearly identical composition by the artist, drawn in pen and brown ink (fig.1), in the collection of the Uffizi in Florence2. As the scholar Miles Chappell has noted of these two drawings, ‘The [Uffizi] sketch depicts Mary, Joseph, a youthful assistant, and the Christ Child in a somewhat open composition. Joseph and the youth concentrate on their work while Mary looks with dismay as the young Christ, seated on the ground, forms a cross with some sticks…This composition in brown pen is a preparatory study for the more finished drawing in pen and brown and blue washes over black chalk of Mary, Joseph, the Christ child, and an angel in the workshop…The composition is now more compact and centralized. While the figures of Mary and Joseph retain their poses, the youth has been transformed into an angel…This definitive composition drawing seems to have had some importance for Coccapani, and he preserved it in his collection and identified it with his mark. The degree of finish, the size…the squaring in black chalk, and the inscriptions giving the projected measurements of 3 1/3 x 2 2/3 braccia…suggest that the drawing had a specific purpose, perhaps as a presentation drawing or model, and is documentation for a hitherto unknown painting.’3 Given the dimensions in braccia noted on the present sheet, the lost painting for which both this and the Uffizi drawing must have been preparatory would have had dimensions of approximately 195 x 155 cm.

The present sheet may also be compared stylistically with such drawings by Coccapani as a Rest on the Flight into Egypt in the Istituto Centrale per la Grafica in Rome4 and a Susanna and the Elders in the collection of the Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center at Vassar College in Poughkeepsie, New York5

This drawing twice bears a drystamp (Lugt 2729), which denotes it as being part of a collection of 17th century Florentine drawings assembled by Sigismondo Coccapani, possibly with the aid of his younger brother and fellow painter Giovanni Coccapani. (It has been suggested that some of the drawings bearing the stamp may have been acquired earlier by Sigismondo and Giovanni’s father, Regolo Coccapani.) The stamp, which reproduces the coat of arms of the Coccapani family, is found on over a hundred extant drawings, most of which are by Cigoli, with the bulk of the remainder by the Coccapani brothers and their contemporaries within Cigoli’s studio and circle6.

Busto Arsizio c.1598-1630 Milan

Recto: Study of a Right Arm Verso: Studies of Shoulders and Arms

Black chalk on faded blue paper. The verso in brown ink. Inscribed Daniel in brown ink at the lower left. 426 x 274 mm. (16 3/4 x 10 6/8 in.)

PROVENANCE: A release stamp of the Austrian Central Commission for the Protection of Historical Monuments [Bundesdenkmalamt] (not in Lugt) on the verso; Anonymous sale, London, Christie’s, 27 March 1974, lot 253 (as Giacomo Cavedone); Mathias Polakovits, Paris (Lugt 3561); Rosella Gilli, Milan; Anonymous sale, London, Christie’s, 7 July 1992, lot 168; P. & D. Colnaghi, London, in 1993; Private collection.

LITERATURE: Nancy Ward Nielson, Daniele Crespi, Soncino, 1996, p.85 no.D36, p.66, under no.84, verso only illustrated p.203, fig.61A; Catherine Monbeig Goguel, Musée du Louvre: Département des arts graphiques. Inventaire général des dessins italiens IV: Dessins toscans, XVIe-XVIIIe siècles, pt.2: 16201800, Paris, 2005, p.416, under no.617.

EXHIBITED: Milan, Galleria Rosella Gilli, Disegni Lombardi dal XV al XVIII secolo, n.d. (1985?), no.49; New York, Paris and London, Colnaghi, Master Drawings, 1993 no.23.

Although he had a relatively brief career of ten or eleven years, Daniele Crespi may be counted among the most significant painters working in Milan in the first quarter of the 17th century. While nothing is known of his early training, he was certainly a precocious artist, for by 1619 he was assisting the painter Guglielmo Caccia, known as Moncalvo, on the frescoes of the dome and pendentives of the church of San Vittore al Corpo in Milan. Among Crespi’s earliest documented independent works is the fresco decoration of a chapel in the Milanese church of Sant’Eustorgio, completed in 1621, and an Adoration of the Magi of around the same date in Sant’Alessandro. This was followed a few years later by work in the church of San Protaso ad Monachos in Milan, while between 1623 and 1627 he painted several works for Santa Maria di Campagna in Piacenza and also decorated the organ shutters in the Milanese church of Santa Maria della Passione. An altarpiece of The Martyrdom of Saint Mark for San Marco in Novara was completed in 1626.

There followed commissions from two of the most important Carthusian monasteries in Lombardy, which represent the culmination of Crespi’s activity as a fresco painter. An extensive series of frescoes

for the nave, entrance hall and ceiling of the Certosa of Garegnano, in the outskirts of Milan, depicting scenes from the early history of the Carthusian order and its founder Saint Bruno of Cologne, was completed in 1629 and is regarded as probably the artist’s finest work. A larger and equally impressive cycle of frescoes for the Certosa in Pavia, begun in 1629, was left unfinished at Crespi’s death from the plague the following year, at the age of about thirty-two.

As a painter and draughtsman, Crespi’s work combines both Lombard and Emilian influences. As Rudolf Wittkower has written of the artist, ‘In his best works Daniele combined severe realism and parsimonious handling of pictorial means with a sincerity of expression fully in sympathy with the religious climate at Milan.’1 Similarly, another scholar has noted that ‘Crespi was a true artist: learned, original, richly diverse and devoted to his art, well able to establish his artistic standpoint amid the cultural and religious preoccupations of his time. He was also a perfectionist in technique and execution…the young Crespi early distanced himself from the Milanese academy in order to seek out new directions: mastering the rules of composition and accuracy of drawing and the absorption of ‘academic tradition’ were only foundations, to which he added a marvellous attention to form and a sincere and versatile pursuit of the ‘natural’.’2

Although Daniele Crespi was among the most gifted draughtsmen working in Milan in the 1620s, only about seventy drawings by him are known. Unusually for a Lombard artist of his generation, almost all of his extant drawings appear to be preparatory studies for paintings or frescoes. No independent, finished drawings by the artist seem to have survived, however.

The recto of this large drawing is a study for the arm of Saint John the Baptist in Crespi’s lunette fresco of Saint Hugh of Grenoble Blessing the First Carthusian Monastery in the Valley of Chartreuse (fig.1) in the Certosa di Garegnano, outside Milan3. Painted near the end of the artist’s brief career, the fresco is one of a series of six lunette scenes from the life of Saint Bruno that were part of the extensive decoration executed by Crespi between 1627 and 1629 on the nave and vault of the monastery church at Garegnano. Two further preparatory studies by the artist for the fresco of Saint Hugh of Grenoble Blessing the Monastery are known. A study in pen and ink for the entire lunette composition is in the Biblioteca Ambrosiana in Milan4, while a drawing in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York5 depicts the figures of John the Baptist, King David and other heavenly witnesses seated in clouds above the main scene6. A closely comparable drawing of the Risen Christ, likewise drawn in black chalk on blue paper, is in the Galleria dell’Accademia in Venice7, and is a preparatory study for another fresco at Garegnano.

The studies of arms and shoulders drawn in pen and ink on the verso of the present sheet have been tentatively related to a painting of Salome Receiving the Head of John the Baptist (fig.2), thought to be one of Crespi’s earliest known works, which appeared at auction in New York in 19938. A similar sheet of Studies of Arms is on the verso of a drawing by Crespi in the Biblioteca Ambrosiana9

GELLÉE, called CLAUDE LORRAIN

Chamagne c.1600/04-1682 Rome

The Garden Wall of the Villa Medici in Rome, with Part of the Aurelian Wall

Pen and brown ink and brown wash. Inscribed claudio lorenese in brown ink at the lower left. 101 x 157 mm. (4 x 6 1/8 in.)

PROVENANCE: The Rev. Dr. Henry Wellesley, Oxford; His posthumous sale, London, Sotheby’s, 25 June 1866 onwards, lot 1023 (Claude: ‘AN ITALIAN VILLAGE. Houses running from the right to the centre; a stone wall to the left, with trees, pen and sepia, 6 in. by 4.’, bt. Robinson for 16s); Sir John Charles Robinson, London and Swanage; His sale, Paris, Hôtel Drouot, 7-8 May 1868, lot 115 (‘Claude Lorrain, Paysage. Les dehors des murailles d’une ville italienne, effet de soleil de midi. Haut., 10 cent.; larg. 15 cent. ½. Collection Wellesley.’, unsold at 180 francs); Acquired from Robinson by John Malcolm of Poltalloch, Argyll and London; Given before 1876 to his daughter Isabella Louisa Malcolm and son-in-law The Hon. Alfred Erskine Gathorne-Hardy, London; By descent to his son, Geoffrey Malcolm GathorneHardy; Thence by descent to The Hon. Robert Gathorne-Hardy, Stanford Dingley, Berkshire; His sale, London, Sotheby’s, 24 November 1976, lot 27; Alain Delon, Chêne-Bougeries, Switzerland.

LITERATURE: J. C. Robinson, Descriptive Catalogue of the Drawings by the Old Masters, forming the Collection of John Malcolm of Poltalloch, Esq., London, 1869, p.168, no.475 (‘Landscape View outside the Walls of an Italian Town, probably a study from nature. Brilliant effect of midday sun. Pen drawing washed with bistre. Signed in the left, “Claudio Lorenese”.’); A. E. Gathorne-Hardy, Descriptive Catalogue of Drawings by the Old Masters in the Possession of the Hon. A. E. Gathorne-Hardy, 77 Cadogan Square, London, 1902, p.31, no.58; Marcel Roethlisberger, Claude Lorrain: The Drawings, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1968, Vol.I, p.122, no.143, Vol.II, fig.143; Elizabeth A. Pergam, ‘John Charles Robinson in 1868: a Victorian curator’s collection on the block’, Journal of Art Historiography, June 2018, p.30.

‘The first and greatest French artist to specialize in landscape painting’1, Claude Gellée, more commonly known as Claude Lorrain, was born around 1600 in the village of Chamagne, south of Nancy in the Duchy of Lorraine in northeastern France. He is thought to have arrived in Rome around 1617, and trained there with the artist Agostino Tassi. Between 1618 and 1620 Claude completed his training in Naples with the German landscape painter Goffredo Wals. After a brief period in Nancy, where he worked on the fresco decoration of the Carmelite church, he was back in Rome by the end of 1626, and there spent the remainder of his career. Claude became known as a landscape painter and draughtsman, working extensively en plein-air in Rome and on sketching expeditions to the surrounding Campagna, notably at Tivoli and Subiaco. As the painter and art historian Joachim von Sandrart, who met and befriended the artist early in his career and often accompanied him on such tours, recalled of Claude, ‘He tried by every means to penetrate nature by all the means at his disposal, stretched out in the fields from dawn to dusk, so as to learn how to represent accurately daybreak, sunrise, sunset and the eventide.’2 At the height of his career, Claude enjoyed a reputation as perhaps the most successful landscape painter in Europe. He counted numerous important patrons and collectors – including Popes Urban VIII and Clement IX, King Phillip IV of Spain, and Princes Camillo Pamphili and Lorenzo Onofrio Colonna – among his clients, and his paintings fetched high prices.

Throughout his long career, the practice of drawing was of great importance to Claude, occupying a central role in his artistic process. Almost five times as many drawings as paintings by him are known, amounting to some 1,200 sheets, ranging from nature studies and compositional drawings to figure and animal studies and independent landscapes, as well as records of finished paintings. He was, as the Claude scholar Marcel Roethlisberger has written, ‘a born draftsman who, during his whole life, took an evident pleasure in producing his drawings...But all his drawings are at the same time much more than mere working stages for the paintings…They are works of art in their own right. Unlike the majority of the drawings by Carracci and even Poussin, there are hardly any sketchy or unfinished-looking drawings

by Claude…A conscientious perfectionist in the design and execution of his paintings, he deployed the same effort and attention to the last of his sketches…The autonomy of Claude’s drawings derives from his profoundly pictorial vision, thanks to which every sketch became a little picture of its own.’3

Claude valued his drawings highly, rarely parting with them. He seems to have kept almost all of his drawings in his studio until his death, and, despite the interest of contemporary collectors, apparently never sold them. The artist or his heirs seem to have assembled many of his drawings into albums, and the inventory of the contents of his studio after his death lists, alongside bundles of loose sheets, twelve ‘books of sketches’. Much of this material has since been dispersed, however, and only a handful of albums or sketchbooks remain intact today. Nevertheless, his drawings became well known for some time after his death, since several hundred of them were reproduced in the form of mezzotint prints in the 18th and early 19th centuries.

The present sheet may be included among a large group of drawings by Claude produced simply as exercises in the study of nature, for the most part done in a twenty-year period between 1630 and 1650. As Richard Rand has noted, ‘These are studies presumably made in the open air in front of the motif, created as part of Claude’s process of observing and recording natural phenomena that he would then use when painting his canvases back in the studio…by the 1650s he had assembled a large cache of nature studies that he could return to as inspiration or aide-mémoire when painting. By drawing in the open air Claude was continuing a longstanding tradition of artists in Italy – particularly those who had traveled from the north – for landscape sketching was seen as an important component of one’s education and training. Claude pursued the practice with particular dedication and enthusiasm, and his studies of nature remain his most innovative and appealing drawings.’4