DAVID AARON

“Goodbyes are only for those who love with their eyes. Because for those who love with heart and soul there is no such thing as separation”

This publication is dedicated to Dr Kathrin Lindner, someone more family than friend.

A remarkable and inspirational human with tremendous passion, love, intellect, care and humour. She was the type of person who would do everything and anything for her family, friends and those less fortunate. Her character, strength and principles were unshakeable. It is impossible to put into words how much she was loved and how much she will be missed. We are eternally grateful to have known her, and for all the wonderful memories we were lucky enough to have with her.

The world is far poorer without her, but her beautiful spirit will survive for eternity. Our thoughts are with Andreas, Marc and Natalie.

DAVID AARON

london | 2024

All items in this catalogue have been checked against the Art Loss Register and Interpol Database.

CONTENTS

6

MODEL OF A BOAT

Middle Kingdom, Dynasty XI–XII, 2087–1759 b.c., Egypt

12

USHABTI FOR TA-MIAT

Second Intermediate Period–Early 18th Dynasty, 1630–1540 b.c., Egypt

16

USHABTI FOR UDJARENES

Late 25th–early 26th Dynasty, Thebes, Late Dynastic Period, c.670–650 b.c., Egypt

20

LARGE BRONZE FIGURE OF OSIRIS

Circa 664–332 b.c., Late Period, Egypt

26

BUST OF AMENHOTEP III, RE-EMPLOYED BY RAMSES II 1540–1190 b.c., 18th–19th Dynasty, Egypt

32

GREYWACKE SERAPIS

Circa 1st–2nd Century a.d., Roman

38

BRONZE SIREN

Circa 5th century b.c., Archaic Period

42

GRIFFIN PROTOME

Circa 7th Century b.c., Greek

46

CORSICAN BRONZE HOARD

Circa 900 b.c., Late Bronze Age, Corsica

50

THE ALBRIGHT-KNOX SARDINIAN WARRIOR

Circa 7th–6th century b.c., Sardinia

56

MONUMENTAL TORSO OF A CYCLADIC IDOL, POSSIBLY BY THE COPENHAGEN MASTER

2500–2000 b.c., Bronze Age, Greece

62

OVER-LIFESIZED TORSO OF MERCURY

Circa 2nd Century a.d., Roman

68

TORSO OF A YOUTH

1st–2nd century a.d., Roman

72

HEAD OF HERCULES

1st–2nd century a.d., Roman

76

HEAD OF HADRIAN

120–130 a.d., Roman

82

EPITAPH FOR QUIRINIA FELICIA

1st Half of the 1st Century a.d., Roman

86

ASSYRIAN RELIEF PANEL

Circa 669–631 b.c., Reign of Ashurbanipal, Ninevah

92

MONUMENTAL AMLASH IDOL

Circa 9th–8th Century b.c., Iran

96

THE ‘ STOCLET ’ CAUCASIAN PLAQUE

Circa 1st–2nd Century a.d., Caucasian

100

KHORASAN TRAY WITH ELEPHANTS

12th–13th Century, Khorasan, Iran

104

MAMLUK CANDLESTICK

Circa 1320–1360, Egyptian or Syrian

108

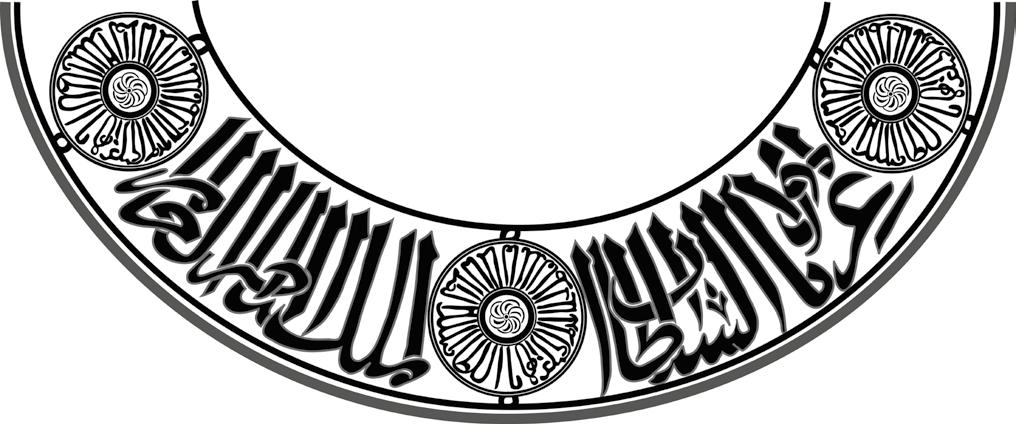

CALLIGRAPHIC FRAGMENT FROM THE ALHAMBRA

Second half 14th century, Spain

112

PAIR OF FATIMID KILGAS

12th Century, Egypt, Cairo, Fatimid

116

MAMLUK PILGRIM FLASK

Mid-13th to mid-14th Century, Near East or Egypt

122

IBEX FRIEZE

3rd Century b.c.–1st Century a.d., Qataban

126

HEAD OF A WOMAN

3rd century b.c.–1st century a.d., Yemen

130

BULL STELE

3rd century b.c.–1st century a.d., Qataban

134

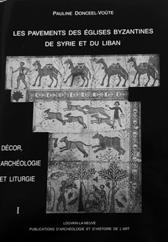

BYZANTINE MOSAIC PANEL

Circa late 4th Century a.d., possibly near Antioch

138

BYZANTINE MOSAIC PANEL

Circa Early 5th Century a.d., possibly Antioch or Apamene

142

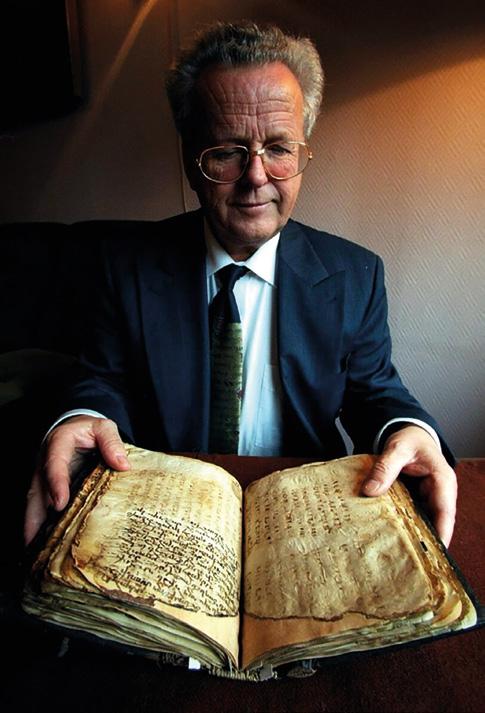

FRAGMENT OF GENESIS FROM A VERY EARLY HEBREW BIBLE

Circa 9th–10th Century

148

EXTRAORDINARY GREEN RIVER TURTLE

Axestemys byssinus. Early Eocene (50 million years)

152

PACHYCEPHALOSAURUS SKULL ‘P. WYOMINGENSIS’

Maastrichtian, Late Cretaceous Period (68–66 million years ago)

156

JUVENILE TYRANNOSAURUS REX SKELETON

Maastrichtian, Late Cretaceous Period (68–66 million years ago)

MODEL OF A BOAT

Middle Kingdom, Dynasty XI–XII, 2087–1759 b.c., Egypt

Wood, l : 79.5 cm

exhibited

Museum of Victoria, Melbourne, Australia, 1984–1987

published

The Herald, Australia, Tuesday 26 July 1949, p. 7.

Ancient Glass; also Roman, Greek and Egyptian Antiquities, Leonard Joel Pty. Ltd., Melbourne, 29 July 1949, Lot 26.

Colin A. Hope and Ron Miller, ‘Life and Death in Ancient Egypt: Tjeby, an Egyptian Mummy in the Museum of Victoria’ (Melbourne, 1984), pp. 10-11. Antiquities, Christie’s, London, 13 October 2008, Lot 69.

MINERVA, 20:2, March-April 2009, p. 43.

David Aaron, 2021, No.17.

provenance

Sold at: Ancient Glass; also Roman, Greek and Egyptian Antiquities, Leonard Joel Pty. Ltd., Melbourne, 29 July 1949, lot 26.

Dannett Collection, Melbourne, Australia acquired from the above sale. Acquired by descent to Simon Walters and Pamela Turnbull from the above.

Sold at: Antiquities, Christie’s, London, 13 October 2008, Lot 69.

Private Collection of Sheikh Saud al Thani (1966-2014), acquired from the above sale. Thence by descent.

With David Aaron Ltd, acquired from the above 19th May 2018. Private Collection, France, acquired from the above 11th April 2020. Accompanied by French cultural passport, number 242494

ALR: S00139170, with IADAA Certificate, this item has been checked against the Interpol database.

condition

Overall in very good condition with natural weathering, flaking and chips present. Some areas of repair including top of mast, and to parts of some of the figures. A more complete and detailed description report available upon request.

The sailing boat manned by six crew seated in the prow, four sailors standing by the mast raising or lowering the linen sail, a seated bald-headed figure behind, and three standing sailors including the helmsman in the curved stern with rudder, four of the standing sailors wearing white painted chest bands, the deck painted with a red and white chequerboard design.

Boats were an essential part of life in ancient Egypt, whether for carrying supplies, or transporting troops, pilgrims or mourners up and down the Nile. They varied in design according to function; reed boats being used for light use such as hunting in the marshes and lakes, papyrus boats being connected with the gods and royalty and used for entertainment or religious events (such as carrying statues of gods in religious ceremonies and pilgrimages), and sturdier wooden boats for heavier use such as trading voyages across the Mediterranean, Red Sea and beyond. Essential and exotic commodities and livestock were all imported by river and sea traffic.

From Predynastic times, ships are depicted on rocks and pottery vessels, and continue to be represented in abundance throughout later periods on paintings, reliefs and models. The story of the Shipwrecked Sailor is one of the best-known tales in Egyptian literature; written during the Middle Kingdom around 2000 B.C., it is the original castaway story, telling of a fantastic journey into the Indian Ocean to the mythical land of Punt, a shipwreck on an island of enchantment, and encounters with a giant serpent, rounded off by rescue and salvation.

Egyptian tombs often contained representations of activities and daily life, the images and models fulfilling a magic and religious function and assuring the continuation of such activities for the benefit of the deceased in the afterlife. The Pilgrimage to Abydos, the resting place and cult centre of Osiris, which every

Egyptian hoped to perform during his life or in the afterlife, was made by boat; to arrive in Abydos was to share in the death and resurrection of the god, a belief particularly important in the Middle Kingdom. Just

Model (top centre) reproduced in The Herald, Australia, 26 July 1949. 1949.

as the life of an ancient Egyptian was spent mainly on the Nile ("a man without a boat" being listed as one of the ills of life), so in death his spirit might travel in a boat upon the waters of the 'Godly West' or make the voyage to Abydos. To this end, model boats were placed in tombs during the Middle Kingdom (circa 2041-1750 B.C.), usually in pairs - one rigged with a sail as well as oars for sailing upriver (southward) with the prevailing wind from the Mediterranean, the other with oars alone for the journey downstream against the prevailing north wind.

The ancient Egyptians saw the blue sky as a celestial river and believed the gods, particulary the Sun god Ra, travelled by special barques across the

river of the sky by day (me'andjet-barque), and the waterways of the Underworld by night (mesektet barque). The model boats placed in tombs provided the souls of the deceased with a magical means of accompanying the Sun on its cyclical journey around the world.

Other examples of funerary wooden boats from Middle Kingdom tombs are to be found in the British Museum, Berlin, and Cairo, one of the finest being in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, cf. W. C. Hayes, The Scepter of Egypt, I, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1990, pp. 267-275, figs 175-179.

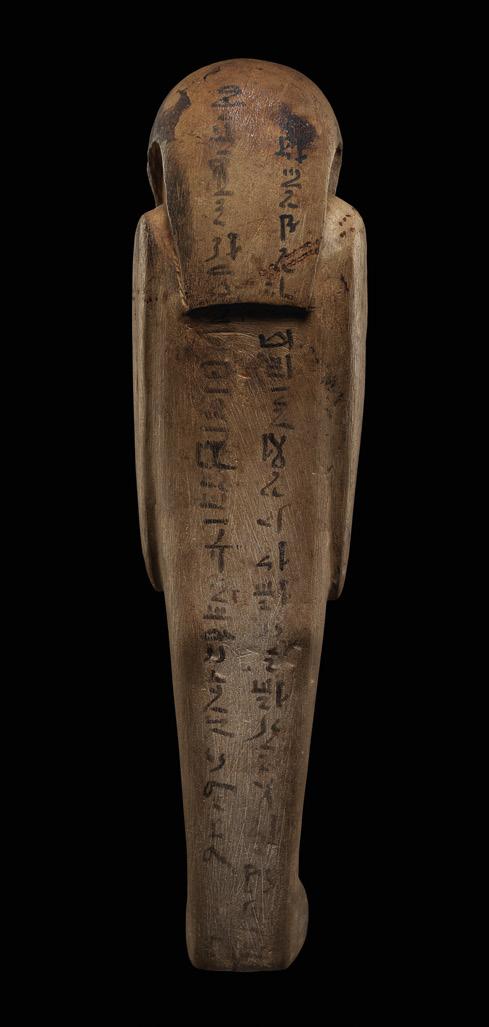

USHABTI FOR TA-MIAT

Second Intermediate Period–Early 18th Dynasty, 1630–1540 b.c., Egypt

Limestone, h : 25.3 cm

published

Antiques, Drouot Richelieu, 6-7 December 1995, cover and Lot 214 B. 12, RWAA, 2012, Lot 6. XXX, RWAA, 2017, Lot 20.

provenance

Previously in the Private Collection of Egyptologist Alexandre Varille (1909-1951), France, acquired prior to 1951. With RWAA, London, from 2011.

Private Collection, London, acquired from the above 5th October 2017.

ALR: S00213001, with IADAA Certificate, this item has been checked against the Interpol database.

condition

In excellent condition, with discolouration and encrustations to the surface as expected with age.

A limestone mummiform ushabti. The elongated face projects forwards above the body, lending it great prominence. The sharp features are detailed with deep lines. The interconnected eyebrows and nose are carved in high relief, framing the lower relief eyes with cosmetic lines. Both ears sit in front of the straight wig, which falls just below the length of the small false

beard under the chin. The arms are crossed over the chest, in the typical posture for ushabtis. A lotus bud is held in the proper left hand, while the hieroglyph ‘sa’ is held in the right. The sa was a protective symbol with power in both life and death. The ankh, symbol of life and revival in the afterlife, may have been a modified version of the ‘sa’.

The reverse of the ushabti is painted with two columns of hieratic text, to be read left to right, as a short form of Chapter VI of the Book of the Dead:

1) “O ye (lit. these) Shawabty of Ta-Miat, if I am counted, if Ta-Miat is counted in the Necropolis 2) in order to do work there, in order to convey sand of the East to the West, I will do (it)! Here am I! thus shall you (.k, masculine pronoun***) say.”

Ta-Miat is a feminine name, meaning ‘the she-cat’. Male pronouns and the masculine word ‘shawabty’ itself occur across funerary objects belonging to women – it was not until the 19th Dynasty that ushabtis attempted to differentiate according to sex, except in the occasional use of female pronouns. Egyptian rebirth was framed within the masculine; to be reborn, the deceased body must be shaped into the form of the god Osiris. Coffins identified the deceased with male gods, Osiris and Re, and presented largely androgynous forms. The false beard on this ushabti is in keeping with the Osirian transformation.

Varille worked on the Karnak-North temple with Robichon from 1940 to 1943. During this period, they met René Adolphe Schwaller de Lubicz and together they founded the ‘Luxor Group’ in 1943. In 1944, after being expelled from the Institut Français, Varille was taken on as an expert by the Service des Antiquités Orientales. In this capacity, he served as a technical advisor at excavations in Saqqara and Karnak, and continued researching with the Luxor Group. Varille’s interest in the Egyptian philosophy of symbols was the focus of these later excavations and their publications. He only returned to France for short periods, including to publish En Egypte with Robichon. In 1951, Varille presented his symbolic theory at the Academy of Sciences, in the midst of the Egyptologist’s dispute over historical vs symbolist approaches. He died shortly after in a car accident at the age of 42.

Many pieces from the Varille collection are now in the Louvre Museum, Paris.

note on the provenance

Alexandre Varille (1909-1951), born in Lyon in 1909, initially directed his studies towards Economics and Letters. Whilst attending the University of Lyon, he met Victor Loret, the Egyptology professor, and this connection sparked his interest in Egyptian philology and archaeology. After continuing his studies in Paris, Varille began working in Egypt in 1931 alongside Clément Robichon (1906-1999). The following year, he was made a member of the Institut Français d'Archéologie Orientale, an appointment he maintained until 1943. In 1939, Varille participated in the excavation of the temple of Medamoud with Fernand Bisson de la Roque, and acquired the monumental doors of Ptolemy III and Ptolemy IV for the Musée des beaux-arts de Lyon. He then ran the site in Zaouiet el-Maïetin with Raymond Weill.

Alexandre Varille (1909–1951).

USHABTI FOR UDJARENES

Late 25th–early 26th Dynasty, Thebes, Late Dynastic Period, c.670–650 b c., Egypt

Serpentine, h : 18.5 cm

published

Catalogue of The Collection of Egyptian Antiquities formed by the late Colonel Evans of Merle, Slinfold, Sussex, Sotheby, Wilkinson & Hodge, 30th June 1924, London, Lot 100, plate II. Antiquities, Christie’s, 15th April 2015, London, Lot 51. Egyptian Antiquities, Charles Ede Ltd, 2016, pp. 24-27.

provenance

Previously in the Private Collection of Colonel Evans of Merle (1828-1903), most likely acquired at some point between 1850-1900. Sold at: Catalogue of The Collection of Egyptian Antiquities formed by the late Colonel Evans of Merle, Slinfold, Sussex, Sotheby, Wilkinson & Hodge, 30th June 1924, London, Lot 100.

Private Collection of Alton Edward Mills (1882-1970), La Tour-de-Peilz, Switzerland, from at least 1970.

Thence by descent.

Sold at: Antiquities, Christie’s, 15th April 2015, London, Lot 51. With Charles Ede Ltd, acquired from the above sale.

Private Collection, USA, acquired from the above 3rd November 2018.

ALR: S00229526, with IADAA Certificate, this item has been checked against the Interpol database.

condition

Chipping to the nose, right hand and feet. Mounted on old collection marble base.

A mummiform ushabti wearing a plain wig with extended lappets tucked behind large ears. The broad face has precisely carved details including cosmetic lines and eyebrows. Folded arms with hands protruding from the wrappings hold the usual agricultural implements of crook and flail, with a seed bag over the left shoulder. Seven lines of hieroglyphic text are inscribed on the body, dedicating the shabti to Mistress of the House, Udjarenes, and quoting Chapter Six of the Book of the Dead. Old inventory number ‘26’ on the base.

Udjarenes (or Wadjrenes) was the daughter of PiankhyHar and granddaughter of Piye (d. 714 BC), Kushite king and the founder of the 25th, or Nubian, Dynasty of Egypt. A Priestess of Hathor and Singer of Amun, Udjarenes held a highly elite position. Ten other ushabtis dedicated to Udjarenes are known, including two in the British Museum (EA68986 and EA24715), two in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, and one in the Berlin Museum (10663)( M L Bierbrier, 1993).

Udjarenes was the wife of Montuemhat (c. 700-650 BC), Fourth Prophet of Amun and Count of Thebes, in a politically advantageous match – Udjarenes’ uncle, the pharaoh Taharqo, made Monteumhat Governor of Upper Egypt. Following the Assyrian invasion of Egypt and the sack of Thebes in 663 BC, the city was virtually autonomous. In a shrewd political move during the ninth year of his reign, Montuemhat invited Nitocris, the daughter of Psammetichus I, to take the role of God’s Wife of Amun (the highest-ranking priestess of Amun). Montuemhat therefore allied himself with both the 25th and the Northern 26th Dynasty. Montuemhat’s tomb in El-Assasif (TT34) is one of the largest ever constructed in Egypt for a private person, and had some of the finest reliefs in archaising style of the Late Period. Although Udjarenes was one of three wives of Montuemhat, she was the only one mentioned in his tomb, where she was probably buried (B Porter and R L B Moss, 1973).

Several statues of Montuemhat exist in museums today, in which he is portrayed in the style of the pharaohs of the Old Kingdom.

note on the provenance

Lieutenant-Colonel John ‘Bashi’ Evans (b. 14 June 1828, d. 1903) was born to a family of prominent bankers and industrialists. During his service for the Crimean war, he learned Turkish and was given command of the Ottoman Bashi-Bazouks (lit ‘crazy heads’). Earning him the nickname ‘Bashi’ for his various daring missions with the group.

He continued his army career until 1861 when he retired from active service to work as a banker. He married Lucy Jane Martha Hamilton in 1865, and they lived in Horsham, Sussex, until his death in 1903. A memorial tablet in Darley Abbey eulogises Evans as ‘one of bravest soldiers of the great Queen’.

Egyptology was among Evans’ wide-ranging interests. The core of his collection was formed in the late 1850s and early 1860s, while he was stationed in Egypt. Evans frequently revisited Egypt between 1870 and 1900 and added substantially to his collection at these times.

Alton Edward Mills (b. 9th September 1883, d. 1970) travelled to Egypt at age 20 to work for the ‘Societé de Pressage et de Dépots’, an Egyptian company specialising in cotton production. Mills served as managing director of the Societé de Pressage until 1946, when he became Chairman of the Board until the outbreak of the Suez War in 1956.

Mills had a keen interest in Egyptology and assembled an extensive library on the topic. Between the World Wars, Mills gathered an important collection of ancient Egyptian objects, and of Chinese porcelain.

Lieutenant-Colonel Evans of Merle (1828–1903).

Alton Mills (1882–1970).

LARGE BRONZE FIGURE OF OSIRIS

Circa 664–332 b c., Late Period, Egypt

Bronze, h : 55 cm

provenance

Reputedly from the Great Temple of Osiris at Karnak, according to Blanchard’s Egyptian Museum Certificate of Antiquity and bronze plaque on stand. Blanchard’s Egyptian Museum, Cairo, from at least c. 1911.

In the Private Collection of Olive Farnworth and her mother, Graiseley Cottage, Wolverhampton, acquired from the above in c. 1911 and kept there until at least 1921, and later moved to Sainsfoins, Little Shelford, Cambridge, as recorded in her house inventory, dated 5th May 1921.

Thence by descent.

ALR: S00237433, with IADAA Certificate, this item has been checked against the Interpol database.

condition

The side plumes of the crown; head of the uraeus; false beard, and implements are missing. There are traces of copper inlay remaining in the eyebrows and cosmetic eye-line. Microstructural and compositional evidence demonstrate that the bronze was subject to pervasive long term corrosion under natural, albeit uncommon condition, likely in alkaline ground waters. The piece has been subject to electrolyte reduction treatment at some point historically. A full report by Dr John Twilley is available.

The figure has been attached to the wood base with a Blanchard’s Museum certificate of authenticity attached to the underside and a bronze plaque on the front, engraved ‘Osiris Temple Karnak, XXVI Dynasty’.

Inventory from Little Shelford, Cambridge, dated 5th May 1921

A bronze statuette of mummiform Osiris on a wooden base. The god wears the White Crown of Upper Egypt, with a central uraeus and chin strap, which would have originally attached to a false beard (now missing). The facial features are cast in fine detail, with slender eyebrows over recessed almond-shaped eyes with prominent cosmetic lines. The hands are crossed over the chest, and the lower ends of the crook and flail remain below the fists – originally these implements would have extended upwards towards the shoulders. Statuettes such as this were made in a range of sizes, and this is a notably large example. One of similar size is now in The Metropolitan Museum, New York (61.45).

As firstborn child of the earth god Geb and sky goddess Nut, Osiris was one of the oldest gods in the Egyptian pantheon. Myth positioned him as one of the first pharaohs of Egypt, who, along with his consort Isis, taught agriculture and crafts to mankind. After his death at the hands of his brother Seth and subsequent resurrection, Osiris ruled as Lord of the Underworld, god of reincarnation and judge of the dead. He is often depicted in mummified form, holding the royal implements of the crook and flail and wearing the White Crown in reflection of this role. By the first millennium B.C., statues and statuettes of Osiris were offered in temples in great numbers, reflecting his importance. Statues of Osiris have been found in sites identified as temples and shrines dedicated to the god, but others have been found as offerings in contexts which are less clear.

Large Bronze Osiris, sold at Christie’s, New York in 2008, price realised $422,500.

note on the provenance

Ralph Huntington Blanchard (b. 1875–d. 1936) was an American antiquities dealer in Cairo, Egypt. Born in Fulton, NY on 25 June 1875, he was the son of Seymour Bailey and Anna Louise Franklin. He came to Egypt in 1905 and worked in the American Consular Service until 1910. He later became a ‘top tier’ antiquities dealer with a formal licence to sell ancient artefacts, with his shop located next to the entrance of the famous old Shepheard’s Hotel. In addition to his stock, he had a large private collection of scarabs, some of which were published by Newberry, A Handbook of Egyptian Gods and Mummy-amulets (Cairo, 1909). His collection was dispersed after his death in 1936, with many being acquired by dealers Matouk and Michailides.

Blanchard’s Egyptian Museum, Cairo, c. 1911.

Original label found on the base of the bronze Osiris from ‘Blanchard’s Egyptian Museum, Cairo’.

BUST OF AMENHOTEP III, RE-EMPLOYED BY RAMSES II

1540–1190 b c, 18th–19th Dynasty, Egypt

Limestone, h : 36.7 cm; w : 48.3 cm

published

Günther Roeder, Hermopolis 1929-1939; Ausgrabungen der Deutschen Hermopolis-Expedition in Hermopolis, Ober-Ägypten, in Verbindung mit zahlreichen Mitarbeitern, 1959, pp. 11 and 257, pl. 43 f.

provenance

Most likely from Hermopolis.

Recorded in March 1930 by Günther Roeder (1881-1966) as being in the possession of a local dealer named Gelâl in the village of al-Idara, later published in his 1959 book.

Private Collection of Eleanor Rixson Cannon (1896-1985), New York, prior to c. 1976.

Private Collection of Frances Lown Crandall (1927-2015), New York, who was a close friend of Eleanor Cannon’s and received this head from the above as a gift in the early 1970s and certainly prior to c. 1976 (accompanied by a photograph of Frances’ son Christopher Crandall, aged 12, with the head in the background dated c. 1976 and a note, diary entry and photos of the statue from Richard Keresey of Sotheby’s dated August 1989). The head was kept at the family residence in Cherry Hill, NJ, until 1986 when it was moved to their new home in Brookfield, CT, before they moved again in 1994 to Princeton, NJ.

Thence by descent to her husband Maxson Crandall Jr. (1929-2016), 15th July 2015.

Thence by descent to their children Maxson Ray Crandall III, Brooks Christian Crandall and Christopher Carson Crandall, 19th December 2016, kept at the home of Christopher Crandall in West Milford, NJ. ALR: S00223332, with IADAA Certificate, this item has been checked against the Interpol database.

condition

Drilled through from top to bottom and across proper left shoulder and side of wig. Top of head carved flat. Beard fragmentary and front of neck gouged out. Vertical channel running continuously through nose and forehead. Proper left side of wig repaired, with remains of plaster fill along join. Surface weathered and /or abraded overall and with seemingly intentional damage to facial features. Comes with vintage concrete base roughly shaped to receive bottom of head.

1959.

Frances’ son Christopher Crandall, aged 12, with the head in the background. New Jersey, USA, dated c. 1976.

Monumental head of an Egyptian king, originally most likely Amenhotep III, 1390-1353 B.C., later re-cut and re-employed by Ramses II, 1279-1213 B.C. Wearing a broad beaded collar and striped nemes-headcloth with fragmentary queue behind. The uraeus and postiche missing, with the incised beard-strap lines still visible. A circular recess is cut into the top of the head, probably to hold the Crown of Upper and Lower Egypt.

The hard cream-colored stone from which this head is carved was particularly favoured by Amenhotep III, however, the head bears evidence of modification. The carved vertical recess on the front of the head would have served to secure the addition of a nose, and the alteration and addition of an uraeus designated by Ramesside stylistic preference. The apparent addition of other royal accoutrements, perhaps streamers or additional cobras, is suggested by several narrow drilled recesses on the sides and back of the head. Another modification is the indication of recesses to indicate pierced ears, which did not appear in royal statuary until the time of Amenhotep III’s son, Akhenaten, and his successors. The drilled recesses at the corners of the lips visually assisted the transformation of what was originally a wider mouth to the smaller mouth preferred by King Ramses II.

Amenhotep III, father of Akhenaten and grandfather of Tutankhamun, presided over a rich and prosperous reign of almost thirty-nine years which saw a flowering of grand art and architecture, best exemplified by the two enormous statues of the king outside his mortuary temple Thebes, known since classical Greek times as the Colossi of Memnon.

note on the provenance

This head was first recorded in March 1930 by the German Egyptologist Günther Roeder (1881-1966), who was engaged in an archaeological dig at Hermopolis at the time. He writes in his 1959 publication on the excavation that the head was at the time in possession of a local dealer named Gelâl in the village of al-Idara, and having been undoubtedly found on the Tell (meaning hill, presumably the ancient site). It is one of a number of such objects that Roeder records as having been found by locals outside of the sanctioned dig. He describes how the inhabitants of the villages around the Tell found many such objects, and that good pieces were sold by them to museums and private collections.

The head is next recorded as being in the possession of Eleanor Rixson Cannon (1896-1985), in New York. She was an artist and collector who lived with her

Eleanor Rixson Cannon (1896-1985).

Photos from 1989.

husband, Victor Hamlin Cannon, in Canyon Ranch, Woodstock, NY. She was part of the artists colony there, and is recorded as having a work included in an 1923 exhibition, alongside that of George Bellows. In 1932 she funded the publication of a small edition of Reeves Brace’s story ‘Within Silence’. Her husband Victor studied mining and was at one time supervisor of gold mines in Siberia. He first married a Russian woman, Kapa Chesnokova, from whom he separated, and in January 1936 he met Eleanor on a boat coming from Finland, marrying her seven days later. They developed land and farmed Aberdeen Angus cattle on their 109 acres along the Hudson before Victor died in 1950. Eleanor is mentioned in several lists of donors to major museums, including MOMA.

She was a close personal friend of Frances Lown Crandall (1927-2015), a watercolour painting and interior designer who was the niece of Charles Lang Freer, from whom she inherited a great love of the arts. She studied at Cornell, graduating with a degree in Human Ecology/Design and Environmental Analysis (Interior Design). She worked as an interior designer all her life, whilst also being an accomplished watercolourist, and was active in numerous historical and philanthropic societies, as well as being a talented and passionate equestrian.

Eleanor gifted Frances the head sometime in the early 1970s, and it remained within the family, passing to her husband, Max, when she died in 2015, and then their three sons on his death in 2016.

GREYWACKE SERAPIS

Circa 1st–2nd Century a d., Roman Greywacke, h : 25.7 cm; w : 17.8 cm

provenance

With Panayotis Kyticas (fl. 1890-1924), Cairo, from at least 1923.

Previously in the Private Collection of Ernest Brummer (1891-1964), Paris and New York, purchased from the above in 1923, and possibly on consignment with him from the above, prior to 1921. (accompanied by 1921 photograph of the bust in Brummer’s store front in Paris, and records from 1952 listing acquisition information. Set in a wooden base by the maker Kichizô Inakagi (1876-1951)).

Thence by descent to his wife, Ella Laszlo Baché Brummer (1900-1999), New York until 1973, then Durham, North Carolina, from 1964 to 1999. Thence by descent to her nephew, Dr. John Laszlo (b. 1931), Atlanta, Georgia.

ALR: S00240878, with IADAA Certificate, this item has been checked against the Interpol database.

condition

Inspected under UV light and 10x loupe. Some chips and losses along edges and to hair. Encrustations in crevices and pitted areas. Generally smooth surface with some uneven patination. Overall in fine and attractive condition. Attached to stand. Height with stand 32.07 cm. Sticker on stand with handwritten inventory number ‘376’.

Detailed list and invoice of objects shipped Paris- NY, May 26, 1952. The bust is listed as no. 15.

Highlighted list of objects, bought in France for NY gallery, April 11, 1952. Photographs of the bust on 35 mm roll film, The

Brummer Gallery Records, Metropolitan Museum of New York.

A bust of the Graeco-Egyptian god Serapis, carved from dark greenish-grey stone. The god is depicted with his typical shoulder-length hair, falling in thick curls on either side of his face and parted in the centre. He also has a thick, curled beard and moustache. The face is carved smoothly and cleanly, with a long straight nose and deep set eyes below a prominent brow ridge. The god wears a loose fitting garment, with a cloak affixed with a round brooch on the proper right shoulder. At the reverse, the locks of hair are tightly moulded to the shape of the head, and flow over the shoulders and down the back in five distinct curled points. Below the hair a rough, uncarved surface angles down to meet the front of the bust, creating a gently curved silhouette when viewed from the side. The deep hole in the top of the head would most likely have held the attachment for a modius, one of Serapis’ key attributes.

This bust conforms to the standard iconography of Serapis, with thick moustache and beard, and attachment hole for a modius atop the head. According to Tacitus, the cult of this syncretistic deity was promoted in Egypt during the 3rd Century B.C. by the Ptolemaic pharaoh Ptolemy I Soter (r. 305304/282). This policy was designed to bring together the disparate elements of Greek and Egyptian worship, by highlighting the pre-existing deity who combined aspects of mortuary gods from Egypt, like the Apis bull and Osiris, with the chthonic figures of Hades and Persephone, and the hedonism and joy of Dionysus. Serapis continued to increase in popularity during the Roman Empire, even replacing Osiris as the consort of Isis outside some temples in Egypt. Serapis was also a god of fertility. He is often depicted with his head crowned by a modius or basket/grain-measure, a Greek symbol for the land of the dead.

The cult of Serapis was centred around the city of Alexandria. The grand Serapeum there is most commonly attributed to the reign of Ptolemy III

Euergetes (r. 246-222 B.C.), however, Welles makes a compelling argument that the temple was, in fact, founded by Alexander the Great (r. 336-323 B.C.) himself (Bradford Welles, 1962). Ancient historians record that, when founding Alexandria, Alexander sought out an oracle at the Ammonium to receive instructions as to where and under what divine protection he should found his city. Following this advice, Alexander visited the island of Pharos to seek out the god, and was guided by an eagle to the shrine of ‘Sarapis’. Here Sarapis himself appeared to Alexander in a dream, identifying himself by spelling out his name in numbers. The god assured Alexander that the city would perpetuate his name for all time, and worship him as a divinity. When he awoke, Alexander ordered the architect Parmenion to build a temple and a statue for Sarapis, and proceeded to conquer Egypt and beyond. Further evidence connects Alexander the Great with Serapis during his lifetime; for instance, Plutarch mentions the god and his cult three separate times in his biography of Alexander. Sarapis is also referenced as the god evoked by Alexander at his death. However, it is debated whether this ‘Sarapis’ is the same as the later Serapis or a different Babylonian deity. It is certain that some form of the god existed prior to the Ptolemaic period, and this god may have been the patron deity of the small fishing and trade port of Rhatokis, which became the site of Alexandria.

Whether or not Serapis was introduced to Alexandria during Alexander’s lifetime, the Ptolemaic promotion of the cult embodies the spirit of Alexander’s campaigns. Ptolemy I adopted Alexander’s work of blending the different cultures within Egypt, focusing on religion to promote a Hellenistic unity across the city. The prolonged popularity of the Serapis cult is a tribute to Alexander’s legacy: ‘In the city on the borders of Egypt which boasts Alexander of Macedon as its founder, Sarapis and Isis are worshipped with a reverence that is almost fanatical’ (Macrobius, 2013).

note on the provenance

Panayotis Kyticas (fl. 1890-1924) was one of the major dealers in Cairo. His original shop was located at Midan Kantaret el-Dikka, opposite Thomas Cook & Sons and Shepheard’s Hotel. In 1896, he relocated to the Halim Pasha Buildings on the same street, just south of the hotel. According to Egyptologist Valdemar Schmidt,

In his rather small shop one could often find interesting and important antiquities at appropriately high prices. Around closing time Cairo archaeologists tended to drop by Kytikas, where one could often find officials from the Egyptian Museum. Consequently Kytikas’ shop was a place to get good information about antiquities finds and discoveries all over Egypt. (Schmidt, 1925)

Flinders Petrie also describes Kyticas as ‘the principal dealer for fine things in Cairo’, and records that he sold many pieces to the Egyptian Museum in Cairo (W. M. Flinders Petrie, 1931). He was also one of the main suppliers for the British Museum while E.A. Wallis Budge was Keeper of the Egyptian collection, with around 3,000 objects acquired through him. During one trip to Egypt in 1919, Budge even stayed in Kyticas’ home. Kyticas also acquired the grand collection of

predynastic flints owned by Captain C. S. Timmins in 1919. After Kyticas died in 1924, his son, Denis, took over running the business.

The bust is mounted in a wooden base stamped with the maker’s mark of renowned artisan and cabinet and stand maker Kichizô Inagaki (1876-1951).

Inagaki carried out several projects for Ernest Brummer between 1922 and 1925, as recorded in the letters and invoices shared between the two and now in the Brummer Digital Archives, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. This further supports the case that Brummer acquired this piece in the early 1920s.

Born in former Yugoslavia, Ernest Brummer (1891–1964) moved to Paris to study art history at the Sorbonne and the École du Louvre, where he studied with Salomon Reinach, who had recently been appointed director of the Musée des Antiquités Nationales. Later, with his brothers, Joseph (1883–1947) and Imre (1895–1928), he opened an antiquities shop.

Ernest remained in Paris after Joseph and Imre left for

Ernest Brummer (1891-1964).

Serapis in the window of the Brummer gallery, France, photo dated 1921.

the United States in 1914 at the beginning of the First World War. The gallery would remain at 3, boulevard Raspail until the early 1920s, when Ernest would relocate it to 36, rue de Miromesnil, after Ernest and Joseph had a falling out. After the war, Joseph opened a second shop at 203 bis, boulevard Saint Germain. The brothers were reconciled by 1924 and participated in a transatlantic partnership until Joseph's death in 1947. After joining the business in Paris, Ernest travelled extensively throughout Europe to acquire works of art for the gallery. The Brummers dealt initially in African tribal arts before branching out into ancient, medieval, contemporary French, and pre-Columbian art.

Ella Baché Brummer (1900-1999, née Laszlo) was a Jewish woman born in 1900 and raised in Hungary. She wanted to study medicine like her brother, Dr. Daniel Laszlo, but she was not allowed to attend medical school. Because of this, she studied at the University of Budapest and became the first woman to graduate as a pharmacist there at the age of 26. She pursued a career in pharmacy and went on to produce her own scientific skin-care products. After a brief and unhappy arranged

marriage to a Hungarian banker by the name of Bacher, she moved to Paris, where she worked as a consultant for a top skincare company. Following this, she founded her own company, Ella Baché and opened her own shop on rue de la Paix in 1936. A salon bearing her name still operates at this location today.

Around 1941, Ella was forced to flee the Nazi invasion of Paris. After her brother obtained her a visa, Ella left France for the United States, leaving Europe on the last ship out of Lisbon in 1942. Ella met Ernest Brummer the day after she arrived in America, at a dinner with her brother and his patient (Ernest). Ella and Ernest lived together for eight years in Manhattan before marrying. Ella established a new laboratory for her cosmetics company on 55th Street, and the couple split their time between New York and Europe, to allow Ernest to continue running the gallery, and Ella her shop at rue de la Paix. Apparently, their decision to marry was sparked by their time travelling – often on their long transatlantic sea voyages, Ernest would be invited to sit at the Captain’s table to dine, but Ella was not allowed to join him due to their marital status.

After Ernest’s death, Ella moved with his collection to a new home in Durham, North Carolina. After five years Ella decided to return to New York to resume running her business, but she left the collection in the Durham house. Prior to Ernest’s death, Ella took no part in the running of the gallery, but afterwards she took over the management of his collection, representing it to Brummer’s clients, museums, and other contacts. Brummer allowed staff from the Metropolitan Museum, New York, with whom all the Brummer brothers worked closely, to visit the collection for research. She also helped in the development of the ‘Medieval Art in Private Collection’ exhibition which ran between October 1968 and January 1969, loaning thirteen small objects under the name Mrs. Ernest Brummer. She also contributed to ‘The Secular Spirit: Life and Art at the End of the Middle Ages’ exhibition in 1975, and sponsored another in 1981. She continued to donate objects to the Met, including 48 pieces of French medieval stained glass in 1977. She also donated and sold objects to the Cleveland Museum of Art, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and the Brooklyn Museum, as well as numerous academic institutions, and private collectors.

Dr. John Laszlo (b. 1931) was born on 28 May 1931 in Cologne, Germany, son of Ella Brummer’s brother, Dr. Daniel Lazslo. He moved to New York with his parents on 21 September 1938, the date of ‘The Long Island Express’ hurricane. The storm prevented them from

docking at Ellis Island, and they had to be pulled by tugboats into New York harbour. Daniel Laszlo, who specialised in cardiovascular physiology, found a job in cancer research at Mount Sinai Hospital. Here he studied folate antagonists in mice, and found the derivative folic acid could produce reductions in breast cancer in mice. John would go in on the weekends and help to change the mice’s cages. When Babe Ruth was admitted to the hospital with symptoms of throat cancer, Dr. Laszlo’s boss suggested treating Ruth with the cancer drugs tested on the mice. Despite Laszlo’s ethical concerns, the treatment went ahead and Babe Ruth went into remission. Following this, Dr. Laszlo chose to leave the hospital, and was offered an opportunity to start a new programme at Montefiore Hospital in New York. Here he established the Neoplastic Disease Division.

Following in his father’s footsteps, John also studied to become a doctor. He joined the Acute Leukemia Service at the National Cancer Institute in 1956, at a time when a cure for childhood leukaemia seemed far beyond possibility. He worked as part of a team providing as much palliative care as possible as they researched a cure. Building on this experience, Laszlo went on to write the book The Cure of Childhood Leukemia: Into the Age of Miracles. Dr. Laszlo served for a time as national vice president for research in the American Cancer Society, and is now Professor emeritus at the Duke University Medical Center.

Maker’s seal of Inagaki.

Kichizô Inagaki (1876-1951).

7

BRONZE SIREN

Circa 5th century b.c., Archaic Period

Greek or Etruscan Bronze, h : 5.5 cm

provenance

Previously in the Private Collection of museum curator, publisher and director of the Presses Universitaires de France between 1934-1976 Mr Paul-Joseph Angoulvent (1899-1976), France, prior to 1976. Thence by descent, France (accompanied by French cultural passport 238899).

ALR: S00226288, with IADAA certificate, this item has been checked against the Interpol database.

condition

In excellent condition, with vibrant green and blue encrusted acquired patination over large areas of the surface. With old collection label on the base of stand, reading ‘—27’.

Sirens were dangerous bird-like females who tempted sailors with their hauntingly beautiful song. In Homer’s Odyssey (XII, 39) Odysseus and his sailors were warned about the lethal consequences of succumbing to the music of the sirens. Odysseus had to be lashed to the mast of his ship, and his sailors filled their ears with beeswax in order to avoid the sirens’ allure.

After centuries of verbal story-telling in the region, the Homeric epics were written down around the end of the 8th century or the beginning of the 7th century B.C. And although no visual description was given by Homer, by the 7th century B.C., sirens were regularly depicted in art as human-headed birds, possibly influenced by the Ba -bird of Egyptian religion. In early Greek art, the sirens were generally represented as large birds with women's heads, bird feathers and scaly feet.

This beautifully modelled figure was possibly an attachment or terminal to a bronze vessel or mirror. Although the shaping and lack of attachment loops or flat surface plates suggest that this could also have been a stand-alone votive figure. With a placid face, upright body, slightly flaring incised wings and clawlike talons, this female siren has close comparables found in the metropolitan museum, New York (1996.42) and the British Museum (1865,0720.46), although both are lacking the definition and beauty of the present example.

note on the provenance

Paul-Joseph Angoulvent (b.1899-d.1976), was a museum curator and collector. It is known that he attended the Succession de M Enkiri sale at Drouot in 1937, where he made various purchases. There is an entry for ‘two bronze sirens’ in this sale, however there is no way to tell for certain that either are the example presented here.

Possibly from this 1937 sale as part of lot 220 “Deux sirènes. Un canard archaïque et un porc”, it is documented that P-J. Angoulvent acquired at least one other object from this auction.

GRIFFIN PROTOME

Circa 7th Century b c., Greek

Bronze, h : 12 cm

published

Antonio García y Bellido, Los hallazgos griegos de España (Madrid, 1936), pp. 22-23, pl. 1

Antonio García y Bellido, ‘La colonización phókaia en España des de los orígenes hasta la batalla de Alalíe (siglo VII-535)’, in Empúries: revista de món clàssic i antiguitat tardana (1940: 2), p. 55, pl. 1, fig. 2

Antonio García y Bellido, Archäologische Ausgrabungen und Forschungen in Spanien von 1930 bis 1940, in Archäologischer Anzeiger (Berlin, 1941: 1/2), p. 223

Antonio García y Bellido, Hispania Graeca (Instituto Espanol de Estudios Mediterraneos, Barcelona, 1948), p. 83, pl. 2

provenance

Private Collection, Madrid, by repute, acquired in Madrid in 1933.

Thence by descent.

Madrid art market, acquired from the above in 2022.

Private Collection of Mr. Carlos Piñel Sánchez, Zamora, acquired from the above in 2022.

Spanish art market, acquired from the above in 2022 (accompanied by Spanish export licence 2022/11956).

ALR: S00218751, With IADAA Certificate, this item has been checked against the Interpol database.

condition

Left ear missing, now restored, and tip of right ear missing, now restored. The surface is stable with an acquired green and brown patination across its entirety.

A Greek protome in the shape of a griffin, with a flanged base for attachment to the shoulder of a cauldron via the three rivets. The sinuous serpentine neck leads to the head of an eagle, with a wide-open beak and pointed tongue. The elliptical eyes are cut through for inlays. A round top knot rises from the crown of the head. The base of the remaining ear reveals that it followed the standard form of the ears seen in other griffin protomes: a long vertical outturned ear, which is frequently compared to that of a hare or a horse. Incised details of overlapping scales run the length of the neck. This protome evinces the Greek griffin, with its bird and serpent-like features, which differs from the Near Eastern leonine version of the creature.

Griffins featured in Greek art since the Aegean culture of the Bronze Age, but returned en masse in

the 7th and 8th centuries following the Geometric Age, in what became known as the Orientalising Period. Trade of goods and raw materials, such as tin, meant that Greek craftsmen were exposed to Near Eastern iconography, techniques, and materials, and adopted them into their own work. Artists looking to reintroduce figural forms into their work turned to countries like Assyria and Anatolia for inspiration. Some scholars have argued that griffin protomes were imported into Greece from the Near East, despite the lack of archaeological evidence to support this. Others have argued that the griffins were produced by eastern craftsmen living in Greece, and others that they were a solely Greek creation. Evidence suggests that griffin protomes were manufactured at Samos, Olympia, Etruria, and they have also been found in Athens, Argos, Ephesus and Rhodes.

This protome would have been part of a group of identical bronzes that would have been attached to the shoulder of a large, circular bronze cauldron supported by a bronze tripod. These cauldrons were costly objects, and were frequently dedicated to sanctuaries of gods and goddesses. In his Histories, Book 4, Chapter 152, Herodotus describes how the first Greek to land in Iberia, Kolaios, dedicated ‘a bronze vessel in the shape of an Argive crater; griffin heads projecting all around the rim’ to Hera on his return to Samos (c. 650 BC). It is possible that griffin protomes were thought to have apotropaic properties. According to myth, griffins lived far away in the north and east, building their nests near sources of gold which they guarded closely. They are also associated with good eagle demons who drove away evil eagle demons and thus protected people from illness and death. The use of griffin cauldrons as burial

urns may be tied to these beliefs.

note on the provenance

Antonio García y Bellido (1903-1972), Spanish archaeologist and art historian, suggested that this griffin protome may have been found in Andalusia. Along with other finds, such as a Rhodian oinochoe found in the province of Granada, a Corinthian helmet found in Huelva, a centaur from Rollos, and a bronze satyr from Llano de la Consolación, the griffin supports Herodotus’ record of relationships between Phocaean travellers and the Tartessian king Arganthonios (c. 670 – c. 550 BC). Because of its strategic position at the southernmost tip of Europe and its plentiful natural resources, ancient Andalusia served as an important intersection for trade for the Greeks, Phoenicians, Carthaginians, and Romans.

CORSICAN BRONZE HOARD DISCOVERED NEAR AJACCIO BETWEEN 1880

AND 1890

Circa 900 b.c., Late Bronze Age, Corsica Bronze, Varying Sizes

max. l : 27.8 cm, max. diam. : 7.7cm

published

R Forrer, ‘Un trésor de bronzes préhistoriques decouvert en Corse’, Bulletin de la Société préhistorique de France, 10, 1924, pp. 224-232.

provenance

Discovered c. 1880-90 near Ajaccio, Corsica. Private Collection of Mr Ducasse. Thence by descent to Jean Dimitri Ducasse (b. 1883), Sarrebourg. Thence by descent.

(accompanied by French cultural passport 237816)

ALR: S00228228, with IADAA Certificate, this item has been checked against the Interpol database.

condition

In excavated condition, all items have a naturally acquired green patina.

A collection of unique bronzes found together on the bed of the Gravona river in the French territorial collectivity of Corsica, during the construction of the Ajaccio-Bastia railway line, which first opened in 1888. This provides two possible precise locations for the find, at the two points where bridges were constructed for the line to cross the river: either in Carbuccia, 10 km north-east of Ajaccio, or at Bocognano, 10 km further in the same direction along the valley. This discovery was published in 1924, in an 8-page essay in the bulletin of the Société Préhistorique Française by Dr Robert

Forrer, the director of the Musée préhistorique et galloromain in Strasbourg.

Various reasons for the discovery of this group in one place have been suggested. It may have been part of a funerary hoard, or perhaps several burials along the banks of the Gravona, a trader’s wares, or even the hidden treasure of a warrior. Both potential discovery sites are in inland mountainous regions. Forrer posits that the bronzes were brought in from Sardinia, via Ajaccio and up the river, and were the property of a Sherden warrior.

However, recent research indicates that the Torrean civilisation in the south of Corsica – previously thought to have begun in the second millennium BCE when Sherden warriors landed on the island – was in fact an indigenous population. There is at least one confirmed example of the distinctive megalithic towers (torri) built by this civilisation in the Gravona valley, northeast of the capital. Therefore, these bronzes may have been produced near the discovery site.

The group contains: a dagger; a luniform bronze that may have been a belt-buckle; a pommel; a disc with a projecting spike, which may have been part of a horses harness or brooch; three bow fibula of various sizes; and three simple rings of differing sizes, possibly a form of proto-currency. The style of these objects suggests a burial date of around 900 BCE.

The dagger is in the style of swords of the late Bronze Age, featuring a leaf-shaped blade with a raised medial rib down its length. The blade and hilt appear to have been cast as one. The hilt joins the blade via a raised semi-circle and is adorned with five raised round rivets.

The crescent-shaped object features five similar rivets along the arc, and a pointed hook on the reverse. A short cross with rounded ends extends from the inner centre of the arc. The rivets and hook could have served as a means of affixing the bronze in place, suggesting that this object may have been a belt-buckle, or perhaps part of a scabbard or horse harness.

The circular disc features a large, rounded spike projecting from its centre, recalling the shields held by warriors in Nuragic bronze statues. Small holes are pierced around the circumference, four of which contain chain links, suggesting that this disc was previously part of a larger object. The disc may have been a phalera on a horse harness or perhaps the centrepiece of a brooch, as in a contemporaneous example in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (2007.498.2).

The pommel takes the form of a hollow ovoid, pierced longitudinally with a hole about 1.3-1.4 cm in diameter, and with another very small hole through one side. This would allow a stick to be inserted through the pommel and held in place by a small nail, so that the pommel could be wielded as a part of a sceptre or other weapon. However, at only 69 g, it seems most likely that this pommel served a decorative, rather than a martial, function.

This collection contains three brooches, including one of remarkable size. The largest brooch is of the typical violin-bow form, with a long pin and spiral coil. The broad catch plate is adorned with raised points of hammered decoration, with a few horizontal lines incised on the bar connecting the plate to the spiral. The median-sized P-shaped brooch, now missing its pin, features an incised pattern of a cross across the arch. Three thin rings attached in a chain at the foot of the brooch suggest an additional ornament of some kind was originally affixed here. The smallest brooch curves towards a pronounced raised rib in the centre of the bow.

Each of the three rings in this find are formed from a single bronze rod, bent into its circular shape. The largest is made from a cylindrical rod, while the others are each formed from a rhomboid rod. It is unlikely that these would have been bracelets, as their diameters are too small. Forrer proposed that, due to their simple forms and the relationship between each of their weights (the weight of the smallest is about 2/3 of the second smallest, which is approximately 1/4 of the largest), these rings

may have been a form of currency, of the kind found in other Bronze Age settlements in Europe.

note on the provenance

Jean Dimitri Ducasse (b. 1883), resided in a sub-prefect of Sarrebourg in north-east France, he inherited this group from his father who lived in Corsica for several years.

THE ALBRIGHT-KNOX SARDINIAN WARRIOR

Circa 7th–6th century b.c., Sardinia Bronze, h : 16 cm

exhibited

Contemporary Art: Acquisitions 1962-1965, Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York, 30th September – 30th October 1966. ¿Kid Stuff?, Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York, 25th July – 6th September 1971.

Kunst und Kultur Sardiniens: vom Neolithikum bis zum Ende d. Nuraghenzeit, Badisches Landesmuseum Karlsruhe, 18th April -13th July 1980, then Museum für Vor- u. Frühgeschichte d. Staatlichen Museen Preussischer Kulturbesitz Berlin in Berlin-Charlottenburg, 31st July – 14th September 1980.

published Art Quarterly, vol. 29. no. 1, 1966, p. 71.

Contemporary Art: Acquisitions 1962-1965, Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York, 30th September – 30th October 1966, pp. 28, 84.

Stephen A. Nash, with Katy Kline, Charlotta Kotik, and Emese Wood, Painting and Sculpture from Antiquity to 1942, Albright-Knox Art Gallery, New York, 1969, p.73, illus. Charlotte B. Johnson, Color and Shape, A-KAG, 1971, illus., pp. 11-12.

Kunst und Kultur Sardiniens: vom Neolithikum bis zum Ende d. Nuraghenzeit, Badisches Landesmuseum Karlsruhe im Karlsruher Schloss vom 18. Apr.-13. Juli 1980, Museum für Vor- u. Frühgeschichte d. Staatlichen Museen Preussischer Kulturbesitz Berlin in Berlin-Charlottenburg vom 31. Juli-14. Sept. 1980, no. 104.

Miriam S. Balmuth, "Sardinian Bronzetti in American Museums", Studi Sardi (1975-1977), Vol. 24, 145-52, passim, figs. 1 and 2.

provenance

Previously in a Private Collection, Germany, from at least 1960.

With Jacques O Matossian (1893-1963), Egypt, acquired from the above, until 1960. With Marguerite (1900-1977) and Paul Mallon (1884-1975), living at that time at Hotel Hassler, Rome, 1960 to 1965. Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, NY, USA (inv. no. 65.22), acquired from the above 30th December 1965 with the George B. and Jenny R. Mathews Fund (includes a dated acquisition record).

ALR: S00218849, with IADAA certificate, this item has been checked against the Interpol database condition

Corroded as shown. Tips of horns and upper end of sword fragmentary. Cracks across proper left elbow and proper right forearm probably indicating repairs.

1969.

1980.

An exceptionally rare and important Sardinian bronze figure of a warrior. The highly stylized figure is depicted standing, holding a club resting on his shoulder in the right hand and a round shield with central boss in the left. The warrior wears leggings under a short kilt, a cuirass, ringed neck-guard, and crested helmet with fragmentary horns. The statue was produced in the Nouragian (from ‘nuraghe’, the type of ancient Bronze Age building found across the island), or Geometric, period of Sardinian art. This is one of very few of its type outside Sardinia.

Different types of Nuragic statuettes depicting human figures have been identified: the ‘tribal leaders’, the shepherds, the warriors, the archers, the worshipper(s), groups (mother and child, wrestlers, etc.). These are recognised as representing the higher classes of a hierarchical social structure – those with religious, political or militaristic responsibilities. This figure is of the warrior type. The statuette likely had a votive function; many similar figures have been discovered in the famous Nuragic sacred wells of the island.

Accompanied by a detailed condition report, inventory notes from the Albright-Knox Art Gallery, and a chemical analysis report carried out by Arthur Beale in 1975 when he was Acting Chief Conservator of the Fogg Art Museum, in preparation for the inclusion of the bronze in a publication by Dr. Miriam S. Balmuth (‘Sardinian Bronzetti in American Museums’, Studi Sardi (1975-1977), Vol. 24).

Photos taken by Albright-Knox Art Gallery, 1965 and undated.

Albright-Knox Art Gallery Inventory, undated.

Acquisition record, 1965. Albright-Knox Art Gallery Inventory record, 1993.

note on the provenance

Jacques O Matossian was born in Alexandria, Egypt, in 1893 to a family of well-established Armenian Catholic tobacco merchants. His father, Hovanhess Motassian, founded a tobacco workshop in 1882, and later merged this with his brother’s shop to form the family business. When Hovanhess died in 1927, his sons Jacques, Joseph, and Vincent took over the management of the company. They successfully merged with British American Tobacco in July 1927 under the umbrella of Eastern Company, without becoming a subsidiary of the larger company.

Jacques Matossian was known for his collection of Coptic textiles and Islamic art, which he displayed in his villa in Neroutsos street. He contributed to the formation of the Islamic collection in the Louvre and many objects from his collection are now in the Metropolitan Museum, New York, from a series of bequests made between 1949 and 1959. He moved to Paris in his later years, and is buried there in the Cimetière de Passy.

Paul Mallon was born in Le Havre, France in 1884. As Mallon was not interested in his father’s shipping business, at a young age he began working for a family friend who imported coffee and other goods from Asia. In this role he developed a connoisseurly taste for coffee and experienced his first foray into collecting art. Mallon began working for the Orientalist Charles Vignier in his twenties, and quickly became known in the art world

Kids Stuff? Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Bufallo, New York, 25th July to 5th September 1971, featuring the Sardinian Warrior on the wall on the right.

for his keen interest in Chinese art. By 1926, Mallon had opened Le Lotus gallery on Rue de Cirque and hired a new secretary Marguerite (Margot) Nabaud Girod, who he married shortly after.

The Mallons had moved their residence and their gallery to the Rue Raynouarz near the Trocadero by around 1934, and Marguerite Mallon took over the running of the gallery. They sold works to many American museums, including the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, the Cleveland Museum of Art, the Brooklyn Museum, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and the Freer Gallery of Art, Washington.

In 1946, the family (including Margot’s son Billy from her previous marriage) obtained permits to travel to Egypt. Here they developed an important relationship with Jacques Matossian. While the Mallons’ funds had been depleted during the Second World War, Matossian had both money and sources for objects. As the Mallons had clients eager to buy, this worked very well for both parties. Their son Billy also became involved in the art trade, travelling to places like Beirut and Tehran – first with Matossian, and then on his own.

The Albright-Knox Art Gallery (now the Buffalo AKG Art Museum) is the sixth oldest public art institution in the United States. It was founded in December 1862 as the Buffalo Fine Arts Academy, who declared in their first public meeting that ‘Buffalo is to have a permanent Art Gallery at once’. However, it was not until the 20th century that the gallery was to find a permanent home.

John J Albright donated funds for the construction of the museum building next to Delaware Park in 1900, and the Albright Art Gallery opened on 31 May 1905 in the new Greek revival building designed by Edward B Green. The gallery was later renamed and reinvented after major donations from Seymour H Knox Jr. and his family, along with hundreds of other donors, facilitated the addition of a new wing designed by Gordon Bunshaft of Skidmore, Owings and Merrill of New York. The new addition opened in January 1962, and the museum became the Albright-Knox Art Gallery.

MONUMENTAL TORSO OF A CYCLADIC IDOL

POSSIBLY BY THE COPENHAGEN MASTER

2500–2000 b.c., Bronze Age, Greece Marble, h : 32 cm

provenance

Previously in the Private Collection of the Marquis de Chasseloup-Laubat, most likely acquired by one of the three main collectors: François de Chasseloup-Laubat (1754-1833), Prosper de Chasseloup-Laubat (1805-1873), or Louis de Chasseloup-Laubat (1863-1954), prior to 1939 (photographed in the album of the family art collection, created between 1918 and 1939).

Thence by descent, France.

Accompanied by French cultural passport 246051

ALR: S00240643, with IADAA Certificate, this item has been checked against the Interpol database.

condition

Large fragment of a larger idol, with small chips to the surface as expected.

Photographs of the torso in the album of the Marquis de Chasseloup-Laubat art collection, created between 1918 and 1939.

A large torso, broken off at the base of the neck and the midriff, carved from marble with a beige patina. The broad, slightly angular shoulders taper towards a slim waist. The true left arm is folded across the body above the true right arm. Two widely spaced breasts are modelled above the hands and long, straight line representing the spine is carved vertically down the otherwise unadorned back. This probably falls into the Spedos group of Cycladic sculptures and is very close to those grouped by Pat Getz-Gentle as the works of the ‘Copenhagen Master’, she believes this artist came from the island of Naxos, and examples of works attributed to this master can be found in museums around the world.

The Cyclades are an archipelago of around 30 small islands, islets, and rocks formed from the exposed summits of two submerged mountain ridges in the Aegean Sea. In classical times the name Cyclades referred specifically to the islands thought to form a circle around the holy island of Delos, the birthplace of Artemis and Apollo (the modern name includes other islands that were previously grouped separately). The Cyclades took an important role in the culture of the Early Bronze Age civilisation of the Aegean Basin, as the islands form a natural stepping stone between Brete, mainland Greece, and Asia Minor. Much of the evidence we have for the Early Cycladic period comes from goods and objects that were found in tombs on the islands. Tombs contain a range of objects in different materials: tools and weapons of Melian obsidian and bronze; shell, stone, bone, bronze and silver jewellery; elaborately carved soapstone boxes. However, marble was clearly the preferred material for sculpting. The marble came mainly from the islands of Naxos and Keros, and some from Paros and Ios.

Figures of the so-called ‘canonical’ type were exclusively produced in the period known as Early Cycladic II, or Keros-Syros phase (c. 2700-2400/2300 B.C). Five

different categories of folded-arm figures have been identified, though there is a great deal of overlap between them. The Spedos variety (named after a cemetery on the island of Naxos) is the type produced and disseminated most widely, which seems to have covered the longest period of time. Studies of the consistent proportions of these figures have suggested that they were planned out with a compass to ensure compliance with the canonical form. The meaning and use of such figures remains uncertain, and may have changed across the five centuries in which they were produced. Some archaeologists have suggested that they were produced solely for funerary use, and may have fulfilled the same role as ushabtis in Egyptian graves (to perform work for the owner in the afterlife), as substitutes for human sacrifice, or as guides for the soul of the deceased. Others have suggested they had apotropaic qualities. Another theory is that they represent figures from Cycladic mythology, and even could have been images of the ‘Great Mother’ goddess. There is little evidence for this deity in Cycladic culture, however, and androgynous figures such as this, and some with male genitalia have also been excavated. Some figures were found broken and repaired prior to their placement in the tomb –this suggests that they were used prior to their burial, perhaps within a domestic shrine.

note on the provenance

François de Chasseloup-Laubat (1754-1833) was born at Saint-Sornin to a noble family, and joined the French engineers in 1774. When the Revolution broke out in 1781, he was still a subaltern, but was promoted to captain in 1791. His skills were recognised in the campaigns of 1792 and 1793, and he was promoted to chef de battaillon and then colonel in the following year. Chasseloup-Laubat was chief of engineers at the siege of Mainz in 1793, before being sent to Italy to work in the advance of Napoleon Bonaparte’s army. Due to his successes in Italy, he was made general of

division, and was chosen by Napoleon as engineer general in 1800. In the peacetime between 1801 and 1805, Chasseloup-Laubat worked to reconstruct the defences of northern Italy, including the great fortress of Alessandria on the Tanaro. Napoleon again called him to serve in the Grande Armée in the Polish Campaign in 1806-1807. Chasseloup-Laubat reconstructed many of the fortresses in Germany during Napoleon’s occupation of the region. In 1810 he was made a councillor of state. He retired after the 1812 Russian campaign, but did occasionally work in the inspection and construction of fortifications. Louis XVII made him a peer of France and a knight of St Louis, as well as a marquis. Chasseloup-Laubat spent his final years organising his collection of manuscripts, until his eyesight began to fail. He married AnneJulie Fresneau de La Gataudière, through whom he acquired the Château de la Gataudière at Marennes, Charente-Maritime.

Their youngest son, Prosper de Chasseloup-Laubat (1805-1873) inherited the title of marquis after his elder brother, Justin, died in 1847. His godparents were Emperor Napoleon I and Empress Josephine. He was educated at Lycée Louis-le-Grand before becoming a civil servant. From 1828, he used his father’s connections to gain a position working for the Conseil d’État. Following the July Revolution of 1830, Chasseloup-Laubat became aide-de-camp of the commander of the National Guard, Marquis de La Fayette. He continued working at the Conseil d’État despite the regime change, and was even promoted. In 1836, he worked as an assistant to Jean-Jacques Baude, Royal commissary in Algeria, for whom he worked at Alger, Tunis, Bône, and Constantine. He returned to France after the failed siege of Constantine in November 1836, and was appointed a councillor at the Conseiller d’État in 1838. He also began his political career at this time, and was elected deputy of Charente-Inférieure (the department in which

the Château de la Gataudière was located), and was reelected in 1839, 1842, and 1846. He was also a member and later president of the Château de la Gataudière of the departmental council of the Charente-Inférieure.

Despite the Revolution of 1848, he was again elected as deputy for the department in 1849, and he voted with the Conservatives of the Party of Order during the Second Republic. He also served briefly as Minister of Marine under President Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte. After the coup d’état of December 1851, he was appointed to the consultative commission replacing the Chambre des Députés, and reelected to the government in Charente-Inférieure. An enthusiastic supporter of the French imperial project, he campaigned for the restoration of the Empire, which was approved by referendum in November 1852. He

François de Chasseloup-Laubat.

was made a minister in 1859, and appointed a Senator of the Empire in 1862. He retained this position until the fall of the Empire in 1870, making him a key figure of French early colonial expansion. Chasseloup-Labat was Minister at the time of the French conquest of Vietnam, and threatened to resign if Napoleon III agreed to return captured territories in exchange for a French protectorate over the whole of the country. It was during his time in Vietnam that Chasseloup-

Labat began to collect objects of art and archaeology.

Along with his wife, Marie-Louise Pilié, he was a key figure in the elaborate social life of the Second Empire, during the period known as the fête impériale. On 13 February 1866, he hosted one of the most flamboyant receptions: a masquerade ball in which he dressed as a Venetian noble to receive his 3,000 guests (including the Emperor and the Empress) in the restored salons of the ministry on the Rue Royale. The reception continued until half past six in the morning, and featured a ‘Cortege of the Nations’, as a symbolic expressions of the host’s political stance and the country’s imperial aspirations.

In 1869, Chasseloup-Laubat was recalled to government, and worked on the constitutional changes to transform the country into a parliamentary monarchy. He was not, however, restored to his position in

Prosper de Chasseloup-Laubat (1805–1873).

the new cabinet formed in 1870. The marquis was also President of the Société de géographie from 1864 until his death. He died in 1873 and is buried at the Père Lachaise Cemetery.

Their eldest son, Louis de Chasseloup-Laubat (18631954), 5th Marquis of Chasseloup-Laubat, was an engineer who specialised in ship design. He expanded the family collection during his travels across Asia, especially in Japan. He was also president of the French Fencing Federation, and co-wrote the rules for international fencing competition.

Louis’ son, François, inherited his father’s interest in travel and archaeology, becoming a recognised explorer. He travelled extensively across Asia, and was on the first journey to the centre of English Malaya, from which he brought back unpublished documents on the still unknown tribes of the Sakai. He spent several years in French Indochina and China, where

This piece was in the private Collection of Manuel de Posada y Garduño (1780-1846), priest and later Archbishop of Mexico from 1839-1846. It was acquired by Prosper de Chasseloup-Laubat (1805-1873) in the 1860s and kept in his collection. Passed down the family by descent until 1947 when it was acquired by the renowned Guennol Collection of Alastair B. Martin. It was consigned on long-term loan to the Brooklyn Museum of Art, New York, and remained on view until 2014. Now with Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, Texas, acquired from the above in 2023.

he compared archaeological finds with those of his friend, Father Theillard de Chardin. He also travelled to Japan and Korea.

His sister Magdeleine and her husband Achille, Prince Murat, also contributed to the collection, during their world-tour through America and Asia in 1926 and 1927.

Louis de Chasseloup-Laubat (1863–1954).

Standing Figure Holding a Were-Jaguar Baby, C. 900-300 B.C., Olmec Culture, Mexico, Middle Preclassic Period, Jade, H: 21.59 cm

OVER-LIFESIZED TORSO OF MERCURY

Circa 2nd Century a.d., Roman Marble, l : 104.7 cm

exhibited

Cantor Arts Center, Stanford University, Stanford, 2002-2022 (Loan no. L.93.21.2002).

published

Fairy-Tale Palace in Spain, Listing no. 451732, Previews Inc., New York, 1985 brochure. Sotheby’s, 1998 brochure.

provenance

With Douglas Fisher (1917-2006), London and Marbella, acquired 1950s-1960s. Private Collection, West Coast, USA, acquired from the above in 1978, accompanied by 1980 photographs and 1993 Christie’s appraisal.

ALR: S00240281, with IADAA Certificate, this item has been checked against the Interpol database.

condition

Intact as preserved. With some losses and associated cracks to the left buttock, as visible in the illustration. With some minor losses to the drapery. With overall minor surface wear, abrasions, chips and incrustation throughout. Some small areas of iron staining near navel, to the proper-right side and proper-right buttock.

A small amount of modern white paint to the brooch and to the drapery near the figure’s back.

Christie's appraisal, 1993.

Photograph of the torso taken in 1980

The torso on display in the ‘Salona’. Fairy-Tale Palace in Spain Listing by Previews Inc., 1985.

Torso pictured in Sotheby’s 1998 brochure for the sale of the house.

An over-lifesize torso of the Roman god Mercury, carved from creamy white marble. He is depicted nude, except for a chlamys that is secured with a circular brooch at his right shoulder. The heavy drapes of the fabric fall across the muscular pectorals at the front, and in a large swoop over the back. The body is highly idealised, with emphasised muscles, a prominent Adonis belt, and smooth, rounded buttocks. The form exhibits the graceful proportions, modelling, and contrapposto introduced by the sculptor Polykleitos in the fourth century B.C.. The arch of the back and slight forward tilt of the torso creates a deep crease in the abdomen, dividing the well-articulated ribs and the lower musculature.

Mercury’s popularity began in the Roman Republic around the fourth century B.C., incorporating some of the attributes of the native Etruscan god Turms. Mercury served as the god of commerce, travellers, doctors, and merchants. He was also the messenger of the gods and the guide who took souls to the underworld. Because of his many roles, Mercury was depicted with a variety of attributes and poses. One similar to this sculpture is now in the Boboli Gardens in Florence, depicting an athletic Mercury with wings emerging from his head, holding a staff in his lowered left hand and the infant Dionysus in his right.

note on the provenance

This torso was on public display from 2002 until 2020 at the ‘Cantor Arts Centre’, an art museum on the campus of Stanford University in Stanford, California, United States. The museum first opened in 1894 and consists of over 130,000 sq. ft of exhibition space, including sculpture gardens.

Torso on display at the Cantor Arts Centre, 2016.

TORSO OF A YOUTH

1st–2nd century a.d., Roman Marble, h : 82 cm

provenance

Previously in the Private collection of Franz Trau (1881-1931) Vienna, from circa 1900. Possibly acquired by descent as part of the family collection, both his grandfather, Carl Trau (1811-1887), and his father, Franz Trau Snr (1842-1905), collected artworks including antiquities during their lifetimes.

With Mr Van der Fecht, Spittelberg, Vienna from before 1960.

Private Collection of Dr Peter Wolf, Böcklinstraße, Vienna, old master’s dealer and specialist, since before 1960, originally acquired from the above.

London art market, acquired from the above 14th August 2017 (but kept in Vienna).

Austrian art market, acquired from the above 2nd October 2023 (accompanied by Austrian export license).

ALR: S00241523, with IADAA Certificate, this item has been checked against the Interpol database.

condition

Intact torso, the sculpture breaks below the knees and is missing arms and head. Chips and abrasions overall, with areas of discolouration and weathering. Drilled and mounted on a base.

The torso in Dr. Wolf’s apartment, circa 2017.

A marble statue of a youth in contrapposto position. The torso is idealised but has only softly suggested muscles, giving the impression of youth. The beginnings of the slender arms and legs further contribute to this impression, as does the languid pose which runs throughout the body.

Statues such as this draw their inspiration from those attributed to the fourth-century B.C. Athenian sculptor Praxiteles. Praxiteles was known for his languid,

youthful, and sensuous male figures. He deployed contrapposto posture, with one taut leg bearing the body’s weight and the other relaxed and bent at the knee. This produced a curve through the figure’s torso and a tilt to the hips and shoulders.

note on the provenance

With Franz Trau Junior (1881-1931), Mr Van der Fecht, and Prof Dr Peter Wolf (See Item 14, Head of Hercules).