SUBLIME

Egyptian, Greek and Roman sculptures

Galerie Chenel

Galerie Chenel

MMXXIII

SUBLIME

Sitting in the spolight of the projectors, pertched up on a metalic column, these sculptures are sublime!

The perfection of a fne tuned picture, the interplay amongst the shadows, a black and white contrast, a minimalist scene in an immaculate studio, they face an elegantly defned light. The lens captures their profound aesthetic. Through their magical aura, these works of art awaken a deep seated desire towards the beautiful, simultaneously they harken a return to classical.

Here we have our elegant Egyptian who radiates beams of light. Discovered within the Hadrian’s villa, this piece draws our attention by her presence and her beauty. An altar shaken up by time tells us its extraordinary story. The almighty Hercules’ muscular physique is highlighted under the rays of the spot lights. His formidable strength exudes from his heroic stance. Venus can be perceived completely disrobed, her fesh and voluptuous curves so sensually depicted. Suspended ever so delicately around Venus’s neck, a Medusa in chalcedony of soft azure looks towards the lens with a determined gaze. A marbled portrait of such rare exquisiteness comes to life with a singular and unique expression. And here we can behold an Amazonian’s arm and shield that stirs one’s imagination in contrast with the obscurity of her missing body.

These sculptures evoke the Sublime! We cannot help but admire them. These works of art denote the genius behind the sculptors of this time period and the sheer magnimity of antiquity. We fnd ourselves utterly fascinated!

To fnd the work of art that will capture our attention. To weave together a collection. Enquiring into their provenance. Delving into the research. Discussing together with colleagues and experts alike. Exploring other comparative works. Guiding the restorative process and creating the complentary piedestal that create the framework through which these sculptures emmanate their splendour once again. To photograph them and present them to you in their best lights. All these phases defne the essence of general chemistry of our profession, and continues to inspire us.

This catalogue is our 18th, and it is with great honor that we can present to you our vision of classical antiquity. We hope to share our profound passion that these works of art incite in us daily.

PINAX WITH A THEATRE MASK

PROVENANCE:

FORMERLY IN THE COLLECTION OF MR JACQUES BULLIOT (1817-1902), ARCHAEOLOGIST AND ART CONNOISSEUR.

PASSED DOWN AS AN HEIRLOOM IN THE SAME FAMILY.

This incredible marble relief has the particularity of being sculpted on both sides. The frst depicts a theatre mask in high relief, the face almost entirely detached from the surface. The masculine character looks elderly, in a way that is almost caricatural. His cheekbones are prominent while his straight, wide nose dovetails with two thick eyebrows, exaggeratedly lifted at the corners, accentuating his tragic expression. The wide open, partly hollowed out mouth and full lips accentuate its dramatic side and lend it an amazing expressiveness. The almond-shaped eyes are framed by fne eyelids and follow the curve of the brows, again translating the dramatic expression sought by the sculptor. The mouth is nestled within a full beard, each individually

sculpted strand ending in a small curl and creating further volume. Moreover, his thick hair is made up of curly locks, small ringlets fowing down his face. The mask has a pointed top with a man’s rounded head emerging from the back, creating a very realistic play of superposition and depth.

The other side, meanwhile, is adorned with a bearded satyr, exquisitely sculpted in low relief, in a frame with wide margins. The face, also in profle, is grotesque: the nose is exaggerated and the forehead bulging while the eyebrows seem contracted, hiding the satyr’s eyes almost entirely. The beard was probably depicted long and pointy, just like his abundant hair, with long locks curling across his forehead. This satyr has a very wild, very expressive

ROMAN, 1 ST - 2 ND CENTURY AD MARBLE

HEIGHT: 16 CM.

WIDTH: 15 CM.

DEPTH: 8 CM.

appearance. All the artist’s skill shines through in the intensity evident in both faces. Despite the lack of context or even gestures, the sculptor was able to convey two sets of strong emotions purely through facial expressions – particularly in the case of the theatre mask. Likewise, their talent is apparent in the way the marble was cut, and the play of depth, which difers completely from one side to the other. Finally, a lovely brown patina adorns the marble, attesting to the passing of time.

perishable materials such as wood, wax and painted fabric. However, thanks to the immense popularity of these motifs, many replicas were made from terracotta, bronze and even marble. Moreover, as for our sculpture, many masks were used as motifs in reliefs, as shown by gorgeous examples conserved at the Vatican, in Copenhagen and in Rome (ill. 1-3). These new decorative elements were thus used either as votive oferings in sanctuaries and tombs or as decorations placed in villas to play an apotropaic role. These rectangular reliefs then took on the name of pinakes. Derived from circular oscilla, they were also exhibited in the gardens of villas, generally on columns (ill. 4).

In ancient Greece then in the Roman Empire, theatre was a much appreciated activity, which was widely represented in the arts. At the time, the actors, exclusively men, wore all kinds of masks, enabling them to play several roles and the spectators to quickly recognise the protagonists. Often with caricatural traits, they were divided between the two theatrical genres: comedy and tragedy. For the stage, the masks were made in

Ill. 1. Double-faced relief, Roman, 2nd century AD, marble, H.: 37.5 cm. Galleria Chiaramonti, Vatican Museums. Ill. 2. Double relief with masks, Roman, 1st century AD, marble, H.: 22 cm. Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen.

Ill. 3. Pinax, Roman, 2nd century AD, marble, H.: 30 cm. Centrale Montemartini, Rome, inv. no. 2129.

Ill. 4. Pinax, Roman, end of the 1st century AD, marble, H.: 130 cm. Garden of the House of Gilded Cupids, Pompeii. Ill. 5. Relief, Roman, 1st-2nd century AD, marble, H.: 22 cm. Villa Albani, Rome, inv. no. 652.

Ill. 1. Double-faced relief, Roman, 2nd century AD, marble, H.: 37.5 cm. Galleria Chiaramonti, Vatican Museums. Ill. 2. Double relief with masks, Roman, 1st century AD, marble, H.: 22 cm. Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen.

Ill. 3. Pinax, Roman, 2nd century AD, marble, H.: 30 cm. Centrale Montemartini, Rome, inv. no. 2129.

Ill. 4. Pinax, Roman, end of the 1st century AD, marble, H.: 130 cm. Garden of the House of Gilded Cupids, Pompeii. Ill. 5. Relief, Roman, 1st-2nd century AD, marble, H.: 22 cm. Villa Albani, Rome, inv. no. 652.

The repertory of the theatre and satyrs was a subject of predilection generally tied to the Dionysian universe, particularly appreciated by the Romans, as shown by the previously mentioned examples and the Villa Albani one (ill. 5).

Our double relief was originally in the collection of Jacques-Gabriel Bulliot (1817-1902, ill. 6), archaeologist and art connoisseur. A scholar and member of the Société Éduenne des Lettres, Sciences et Arts, he is known for having discovered the ancient site of Bibracte, capital of the Aeduans, a people of Celtic Gaul. In 1867, Napoleon III tasked him with heading the digs that would lead to the discovery of complex groupings of buildings, private dwellings, public buildings and artisanal workshops. Our sculpture stayed in his family’s collections as an heirloom until the present day. An old collection label is still visible on the marble base.

Ill. 6. Jacques-Gabriel Bulliot (1817-1902).

Ill. 6. Jacques-Gabriel Bulliot (1817-1902).

STATUETTE OF VENUS

PROVENANCE:

FORMERLY IN THE COLLECTION OF DEALER PHOCION J. TANO (1898-1972 ), TANO ANTIQUITIES, CAIRO, EGYPT, SINCE AT LEAST THE 1940S

JUDGING BY THE OLD LABEL AND THE WOODEN BASE. THEN FORMER FRENCH PRIVATE COLLECTION.

This delicate statuette represents Venus, Roman goddess of love and beauty, with her sensual body covered by a lovely, folded drapery. The statuette is sculpted from marble with deep yellow hues and brown and white touches, attesting to the passing of time and giving the work a certain aura. The goddess is represented standing, the weight of her body on her straight left leg. This position, known as contrapposto, leaves her right leg bent, slightly turned inwards in a movement intended to shield her privates and thus creating a slight tilt of her hips. Venus has just emerged from her bath, entirely nude and only wearing a drapery that falls gracefully from her pelvis, falling along her thighs and covering her buttocks and legs. The fabric, sculpted in a realistic manner, seems wet, each fold slipping

while hugging the shape of her body, accentuating her feminine attributes. Her torso is tilted, her left shoulder lowered and her stomach slightly creased. Her bosom is left naked, revealing two rounded, delicately shaped breasts. Her stomach and hips are plump and she has a discreetly etched navel. The fnely shaped groin leads the viewer’s gaze to our goddess’s private parts, accentuating the sensuality inherent to the goddess of beauty. Her back is smooth, the line of her spine slightly etched, following the curve created by her tilted hips and going down to her buttocks. Her hourglass fgure is thus well defned, with her small waist and round hips. The fabric, which cascades down her body, covers her buttocks in a very elegant gesture of modesty. Her left arm is intact almost up to

1

ROMAN,

ST - 2 ND CENTURY AD MARBLE

HEIGHT: 11.5 CM.

WIDTH: 5 CM.

DEPTH: 2 CM.

her wrist. Her elbow is bent and her hand would probably have held locks of hair, while a swathe of fabric went over it. A fragment is still visible just below her shoulder. Given the position of her right shoulder, her right arm was probably raised along her head, her right hand holding back locks of hair. This very position is illustrated by a sculpture currently conserved at the Vatican (ill. 1).

appearance inherent to the goddess of beauty, sculptors often represented her partially clothed in a drapery that is frequently slipping delicately, almost uncovering her privates, sparking the public’s curiosity. This is the case in our sculpture, the drapery subtly revealing the goddess’s voluptuous curves and smooth skin. Other gorgeous examples are currently conserved in several international museums (ill. 3-6).

Ill. 3. Aphrodite, Hellenistic, 1st century BC - 1st century AD, marble, H.: 29 cm. Musei Capitolini, Rome, inv. no. 2124.

Ill. 4. Torso of Aphrodite, Hellenistic, 1st century BC 1st century AD, marble, H.: 97.8 cm. Harvard Art Museums, Massachusetts, inv. no. 1900.17.

This statuette is based on the Aphrodite of Knidos model, the frst entirely nude portrayal of the goddess, carried out by the Greek sculptor Praxiteles in the 4th century BC. The original statue, the existence of which is confrmed by antique sources, represented the goddess bathing, surprised during her ablutions and shielding her privates in a gesture of modesty (ill. 2). The now vanished masterpiece was a source of inspiration for many sculptors, bringing about countless sculptures with varied postures and draperies. To accentuate the sensuality and intimate

Ill.

1053.

Ill. 5. Statue of Aphrodite, Roman, marble, H.: 59 cm. Arkeoloji Müzesi, Izmir, inv. no. 630.

6. Two Statuettes of Aphrodite, Hellenistic, 3rd–2nd century BC, marble, H.: 42.5 cm. Arkeoloji Müzeleri, Istanbul, inv. no.

Ill. 1. Venus Anadyomene, Roman, mid-2nd century AD, marble, H.: 149 cm. Musei Vaticani, inv. no. MV.807.0.0.

Ill. 2. Venus, Roman sculpture, 1st-2nd century AD, found in Ostia, Parian marble, H.: 107 cm. British Museum, London, inv. no. 1805,0703.15.

This delicate statuette of Venus once belonged to the antiquities collection of the Tano gallery in Cairo, Egypt. It belonged to Phocion J. Tano (1898-1972), a dealer specialising in Egyptian antiquities (ill. 7). Our sculpture is mounted on a pretty black wooden base stamped with “Venus” in golden letters. Just above the stamp is another faint impression of the goddess’s name, without any gold highlighting. At the bottom of the base was an old label from the Tano gallery, which says “N. Tano, Antiquities, no. 721, Cairo — Egypt” (ill. 8).

HEAD OF A WOMAN

ROMAN, JULIO-CLAUDIAN DYNASTY, 1 ST CENTURY BC - 1 ST CENTURY AD

MARBLE

UPPER LIP RESTORED.

HEIGHT: 27 CM.

WIDTH: 16 CM.

DEPTH: 18.5 CM.

PROVENANCE:

IN A EUROPEAN COLLECTION FROM THE 18 TH CENTURY, BASED ON THE RESTORATION TECHNIQUES. THEN IN THE FRENCH PRIVATE COLLECTION OF THE ACADEMICIAN ÉMILE GIRARDEAU (1882-1970), ACQUIRED BEFORE 1970. BY DESCENT IN THE SAME FAMILY.

This head represents an elegant young woman. Sculpted from white marble, her oval, delicate featured face is made striking by large, strongly carved eyes. Her eyebrows are delicately arched, softening her gaze. Her closed mouth and calm, composed gaze bestow upon the young woman a serene, almost pensive expression. Her missing nose shrouds our statue in a veil of mystery, giving free reign to the viewer’s imagination. Her features, hairstyle and the lack of a nose not only make the charm and elegance of this statue, they make it

unique. Her hairstyle, which was originally topped with a greater volume of hair, is made up of several plaits that are fattened and held back. Her hair is parted down the middle, with the braids forming a low chignon at the nape of her neck. On her crown, a band encircles her hair, adorned with small circular berries that add extra charm. Wavy locks that have come free fall elegantly across her forehead. Her chignon is tied with a plait from which well defned curls have come loose on either side of her nape. Each type of hairstyle reveals a hair fashion from a certain

period. This one enables us to date our sculpture to the Julio Claudian era. Our delicate feminine head has traces of concretion and a brown patina, giving the marble very elegant, golden highlights.

The infuence that imperial portraits, idealised and representing the patron’s position, had on private portraits is obvious. Individuals eagerly embraced the trends adopted by their sovereigns or their spouses, particularly as far as hair was concerned. Although the art of private portraiture was generally subject to less restrictive rules, it still needed to give a certain image. As an example, the bust of Livia, wife of the emperor Augustus and mother of Tiberius, currently conserved at the J. Paul Getty Museum, displays a smooth, full, oval face, giving her a gentle, candid appearance (ill. 1). Presented as a young woman, she embodies modesty and stability — key themes as Augustus asserted his power after years of political confict and civil war. And yet, at the time the bust was crafted, Livia was about 60 years old. The bust thus perfectly illustrates the idea of the idealised portrait, making it possible to infer that our delicate statue did not portray its owner realistically, but rather idealistically. Moreover, our elegant, plait wearing young woman displays features similar to those of Livia. Both faces are oval and full, with high cheekbones and gentle, delicate traits, the delicately arched brows following the lines of the eyes. The assimilation of physical features and hairstyles was common among the aristocratic elite, whose portraits, arranged in their interiors, served to assert their social status and display their

wealth. As for our portrait, other representations of young women depicted in the fashion of the time are currently conserved in Italy (ill. 2-3).

Ill. 1. Portrait of Livia, Roman, ca. AD 1-25, marble, H.: 40 cm. J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, inv. no. 74.AA.36.

Ill. 2. Portrait of a young woman, ca. AD 10, marble, H.: 52 cm. Capitoline Museums, Rome, inv. no. 1081.

Ill. 3. Bust of a woman, Roman, ca. AD 13, marble, H.: 35 cm. Palazzo Malatestiano, Fano, no. 5674.

Ill. 1. Portrait of Livia, Roman, ca. AD 1-25, marble, H.: 40 cm. J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, inv. no. 74.AA.36.

Ill. 2. Portrait of a young woman, ca. AD 10, marble, H.: 52 cm. Capitoline Museums, Rome, inv. no. 1081.

Ill. 3. Bust of a woman, Roman, ca. AD 13, marble, H.: 35 cm. Palazzo Malatestiano, Fano, no. 5674.

The other particularity of our portrait is the discreet presence of a band adorned with berries that dresses the hair of our young woman. Fruit adorned crowns are generally associated with Dionysus, the Greek god of wine and immoderation, and, more broadly speaking, his Dionysian suite, which included maenads, satyrs and wild animals. A gorgeous example of a portrait of a maenad whose forehead is adorned in the same way is currently conserved in Italy (ill. 4). The use of such an attribute in private Roman portraits was not uncommon, conveying the patrons’ desire to be associated with either the god himself or his companions and all that they represent: abundance, the pleasures of life and prosperity. This is what we fnd in our portrait. The association of the facial features following the trend of the time with a mythological attribute celebrates virtues inherent to the Dionysian world and confrms the patron’s high social status. This very typology can be found in various examples conserved in diferent collections across the world (ill.

Our gorgeous portrait was initially in a European collection from the 18th century, as shown by the restorations carried out on the nose, now removed, and the upper lip, still visible. It then joined the collection of the engineer and academician Émile Girardeau (1882-1970, ill 6) and stayed within his family as an heirloom.

5).

Ill. 4. Maenad, Roman, 2nd century AD, marble, H.: 30 cm. Museo Civico, Italy, inv. no. 699. Ill. 5. Child crowned with ivy, Roman, 2nd century AD, marble, H.: 60 cm. Gallerie degli Ufzi, Florence, inv. no. 1914.260.

Ill. 6. Émile Girardeau (1882-1970).

5).

Ill. 4. Maenad, Roman, 2nd century AD, marble, H.: 30 cm. Museo Civico, Italy, inv. no. 699. Ill. 5. Child crowned with ivy, Roman, 2nd century AD, marble, H.: 60 cm. Gallerie degli Ufzi, Florence, inv. no. 1914.260.

Ill. 6. Émile Girardeau (1882-1970).

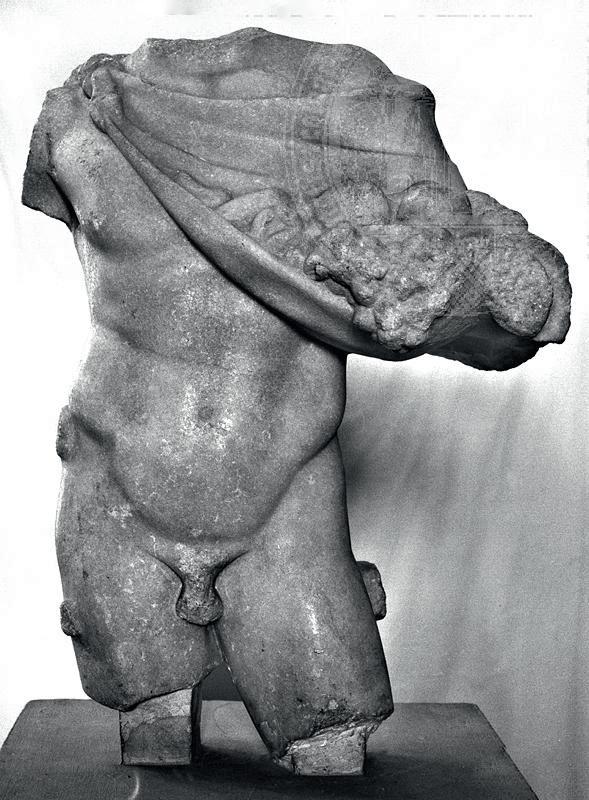

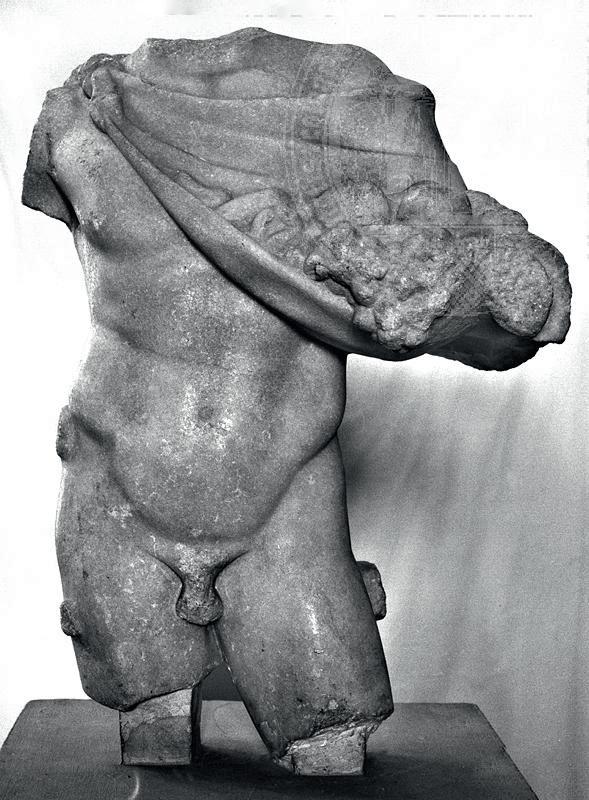

TORSO OF DIONYSUS

PROVENANCE:

FORMER COLLECTION OF MR AND MRS BETHAM, LONDON. WITH THE URAEUS GALLERY, 24 RUE DE SEINE,

6 TH ARRONDISSEMENT, PARIS, SINCE AT LEAST NOVEMBER 1975. THEN FRENCH PRIVATE COLLECTION OF MR F., ACQUIRED FROM THE ABOV E.

This captivating sculpture depicts the torso of Dionysus in an aged white marble. The god, of whom only a torso and thighs remain, is represented by a young athletic man in heroic nudity. The muscles are subtly marked, the abdomen in front, reinforcing this juvenile appearance. The play of curve and counter-curve is present here, the body taking the S-shape characteristic of the contrapposto position. The left leg is stretched while the right is slightly bent, the line of the pelvis creating an oblique thus contorting the torso. The left hip, full, moves forward into the space, reinforcing the athletic aspect of our young god. Finally, the line of the pelvis is opposed to the line of the shoulders, the left shoulder slightly lowered creating again a very singular torsion. The back, quite fragmentary, reveals muscular buttocks

while a tree trunk remains serving as support for the whole sculpture. Our young god is thus represented in heroic nudity, simply dressed in a skin of an animal. Attached to his left shoulder, it falls on his right hip in thick waves. The animal drape, commonly called nebride (in ancient Greek “deer”), is a skin of panther, fawn, or goat, a characteristic of the cult of Dionysus. It was worn by the god himself and by his companions: the satyrs, the maenads and the Bacchante. The attention brought by the artists in the representation of clothing is marked by the rendering of folds, giving an impression of gravity and a quite singular play of matter. Finally, on his right shoulder is preserved a lock of hair typical of the hairstyle worn by the god. Our torso in sculpted in a marble marked with an

ROMAN, 1 ST - 2 ND CENTURY AD MARBLE

HEIGHT: 84 CM.

WIDTH: 31 CM.

DEPTH: 18 CM.

ancient patina and traces of brown, a testament to the passage of time on the stone. Its fragmentary characteristics as well as the browns on the surface of the marble testify to its past history and give our torso a very distinctive aura.

Dionysus, later called Bacchus by the Romans, is the son of Zeus and the mortal Semele. Provoked by jealousy, Hera, the wife of Zeus, kills Semele whom was still pregnant with the young Dionysus. Zeus saves his son by sewing him into his thigh until he was born. Once born, Hermes delivered Dionysus to the Bacchantes and maenads to be raised. Dionysus is one of the most celebrated divinities in the ancient world, associated with vines and wine, to excessiveness and also wild nature. He is also commonly represented surrounded by his companions in the famous Dionysus procession, including wild animals such as panthers or leopards. This representation of Dionysus in such heroic nudity and his hip, echoes the work of the famous Greek sculptor Praxiteles who developed his art in the 4th century BC. One of his masterpieces, the Satyr at Rest, a roman copy which is the most known in the Capitoline Museum (ill. 1), shows the attention the artists was rendering for the muscularization and details of the body. The contrapposto position that we fnd in this work and in other sculptures thus allows artists to show their dexterity in the rendering of fesh. Faithful companion of Dionysus, the Satyr sculped by Praxiteles, also wears an animal skin refecting the outft of our young deity. This iconography is also

found in beautiful examples in New York, Rome, Madrid, and Santa Barbara (ill. 2-5).

Our torso was frst housed in the private collection of Mr and Mrs Betham, in London and later joined the collection of Galerie Uraeus, located at 24 rue de Seine in the 6th arrondissement of Paris. It was then photographed for a Maison & Jardin company advertisement, published in n°285 of the

Ill. 1. The Resting Satyr by Praxiteles, Greek, marble, H.: 170.5 cm. Musei Capitolini, Rome, inv. no. MC0739.

Ill. 2. Statuette of a Young Dionysus, Roman, 1st-2nd century AD, marble, H.: 38 cm. The MET, New York, inv. no. 2011.517.

Ill. 3. Statue of Dionysus, Roman, 1st half of the 2nd century AD, marble, H.: 86.5 cm. Musei Vaticani, inv. no. MV.2394.0.0.

Ill. 4. Dionysos and a Panther, Roman, AD 130-140, marble, H.: 97 cm. Museo del Prado, Madrid, inv. no. E000105.

Ill. 5. Dionysos Lansdowne, Roman, 2nd century AD, marble, H.: 134,5 cm. Museum of Art, Santa Barbara, inv. no. 2009.1.1.

Ill. 1. The Resting Satyr by Praxiteles, Greek, marble, H.: 170.5 cm. Musei Capitolini, Rome, inv. no. MC0739.

Ill. 2. Statuette of a Young Dionysus, Roman, 1st-2nd century AD, marble, H.: 38 cm. The MET, New York, inv. no. 2011.517.

Ill. 3. Statue of Dionysus, Roman, 1st half of the 2nd century AD, marble, H.: 86.5 cm. Musei Vaticani, inv. no. MV.2394.0.0.

Ill. 4. Dionysos and a Panther, Roman, AD 130-140, marble, H.: 97 cm. Museo del Prado, Madrid, inv. no. E000105.

Ill. 5. Dionysos Lansdowne, Roman, 2nd century AD, marble, H.: 134,5 cm. Museum of Art, Santa Barbara, inv. no. 2009.1.1.

magazine Connaissance des Arts, in November 1975 (ill. 6). The torso was fnally acquired on 18 October 1976 by Mr F., a French private collector (ill. 7).

Ill. 6. Connaissance des Arts, n° 285, November 1975, p. 1.

Ill. 7. Invoice of the Uraeus gallery, 16 October 1976.

Ill. 6. Connaissance des Arts, n° 285, November 1975, p. 1.

Ill. 7. Invoice of the Uraeus gallery, 16 October 1976.

LIBATION TABLE

MARBLE RESTORATIONS.

PROVENANCE:

FORMERLY IN THE COLLECTION OF GIAMPIETRO CAMPANA (1809-1880), IN THE GARDENS OF VILLA CAMPANA, ROME. THEN IN THE FRENCH PRIVATE COLLECTION OF GUSTAVE CLÉMENT-SIMON (1833-1909) AT HIS CHÂTEAU DE BACH, NAVES, CORRÈZE. PASSED ON TO GEORGES COUTURON WHEN THE CASTLE AND ITS COLLECTION WERE SOLD IN 1938. BY DESCENT IN THE SAME FAMILY SINCE THEN.

This once quadrangular marble fragment presents a Latin inscription with a hollow circular motif in the middle. The whole piece is bordered with a carved line that forms a frame. The inscription is laid out over six straight, regular lines, written in Roman square capitals also known as capitalis monumentalis. Considered the most advanced form of Latin writing, they were used from the 5th century BC and really perfected from the 2nd century BC. They then acquired a more regular, rigorous appearance, alternating between thick and

thin strokes and punctuated with triangular serifs. The ceremonial writing was then mainly used for inscriptions on public monuments and, as illustrated by our example, in funerary contexts.

The text of our inscription reads as follows:

D(is) M(anibus)

Cornelius

Dignus Mussiae

Horaeae

Coniugi Dul

Cissimae B(ene) M(erenti) F(ecit)

ROMAN, 1 ST - 2 ND CENTURY AD

HEIGHT: 28.5 CM.

WIDTH: 32.5 CM.

DEPTH: 3.5 CM.

We can translate it as:

To the Manes.

Cornelius Dignus had this made for his very gentle and deserving wife Mussia Horaea.

Our inscription begins with a dedication to the Manes, deities likened to genies, which were considered, in the pagan religion of Rome, to symbolise the souls of the dead. Next comes the patron, Cornelius Dignus, who had the inscription engraved for his dead wife Mussia Horaea. Our inscription was once a libation table, commonly called mensa sepulchralis. In the middle of it is a hollowed out, circular area, itself perforated with fve small holes. The circle is adorned with a pattern delicately carved around the edge, imitating the shape of the cups used in funerary cults. Such plaques were once placed on tombs, and the central perforations made it possible to pour oferings over them. This religious ritual, popular under the Roman Empire, consisted in honouring the dead by serving them sustenance, generally milk, wine, honey or oil. These were poured over the plaque and fowed through the holes to feed the dead in the afterlife. Gorgeous examples of such libation tables are currently conserved in England and France (ill. 1-5).

which appears on most of the funerary inscriptions from that period. These deities, which symbolised the spirits of the dead, were the physical anchors of commemorative ceremonies, particularly during the festival of Parentalia in February, when people took care to honour the tombs of dead family members to appease the gods. Secondly, it shows the importance of the honorary practice of libations to the Romans through the object’s very typology, as it was created for that specifc purpose.

Our inscription is thus a fne illustration of the importance of private religion in the Roman Empire, frst with the dedication to the Manes,

This libation table is sculpted from gorgeous white marble and has a slightly brown patina. Despite the

Ill. 1. Libation table, Roman, 1st-2nd century AD, marble, H.: 26 cm. Wellcome Collection, London, inv. no. 1655529.

Ill. 2. Libation table, Roman, 1st-2nd century AD, marble. Wellcome Collection, London, inv. no. 1655527.

Ill. 3. Libation table, Roman, 1st-2nd century AD, marble, H.: 32 cm. Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, inv. no. C3.45.

Ill. 4. Libation table, Roman, 1st-2nd century AD, marble, H.: 15.5 cm. Musée du Louvre, Paris, inv. no. Ma 3910.

breaks, the inscription is still completely legible and extremely well conserved, each letter standing out very distinctly. It is presented in a wooden frame, attesting to the piece’s old provenance.

Our inscribed plaque was in the collection of Marquis Giampietro Campana (1809-1880), who lived in Rome and was one of the greatest collectors of the 19th century. As a papal banker and art enthusiast, over several decades, he accumulated a collection of close to 12,000 archaeological pieces, paintings and sculptures. These artworks were divided between a few of his residences, where they adorned rooms and gardens, jealously hidden from the eyes of the public. Our inscription is mentioned in Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum (“Corpus of Latin inscriptions”), with its location given as the gardens of his villa in Laterano (ill. 6). The book illustrates the growing interest in epigraphic science in the 19th century, which led several archaeologists to undertake the ambitious endeavour of listing every Latin inscription. Giovanni Battista de Rossi thus wrote, in Volume 6: “Tabula marmorea in hortis Campanae prope Lateranum” (“marble

plaque in the gardens of Villa Campana, near Laterano”). The marquis of Campana ultimately met with an outlandish fate. Accused of having stolen from the cofers of the Papal State, he was banished for life. The Pope then decided to put his collection up for sale and it was divided between private collections as well as the collections of some of the most prominent museums in the world. Our inscription joined the collection of the French Scholar, Gustave Clément-Simon, born in 1833 and died in 1909. After magistracy studies and holding various positions throughout France, he fnally settled in Corrèze in 1879 and acquired the Château de Bach. He then devoted the last years of his life to his art collection, including our libation table. Passionate about archeology, he took an interest in the various excavations around Corrèze and traveled frequently to Italy, Greece, and Turkey, bringing back a number of souvenirs that would en-rich his collection. The inscription

Ill. 6. Giovanni Battista de Rossi, Inscriptiones urbis Romae latinae (“Inscriptions of the Latin city of Rome”), Vol. IV.3, Berlin, 1886, p. 1832, no. 16189.

Ill. 5. Libation table, Roman, 1st century AD, marble, H.: 26 cm. Musée du Louvre, Paris, inv. no. Ma 3896.

Ill. 6. Giovanni Battista de Rossi, Inscriptiones urbis Romae latinae (“Inscriptions of the Latin city of Rome”), Vol. IV.3, Berlin, 1886, p. 1832, no. 16189.

Ill. 5. Libation table, Roman, 1st century AD, marble, H.: 26 cm. Musée du Louvre, Paris, inv. no. Ma 3896.

remained to his descendants and then passed onto George Couturon when he bought the Château, furniture, and art collection in 1938. Our libation table passed down within the same family thereafter.

Ill.

Publication:

- G. Battista de Rossi, Inscriptiones urbis Romae

latinae (“Inscriptions of the Latin city of Rome”), Vol. IV.3, Berlin, 1886, p. 1832, no. 16189.

Ill. 6. Marquis Giampietro Campana (1809-1880).

7. Château de Bach, Naves, Corrèze.

Ill. 6. Marquis Giampietro Campana (1809-1880).

7. Château de Bach, Naves, Corrèze.

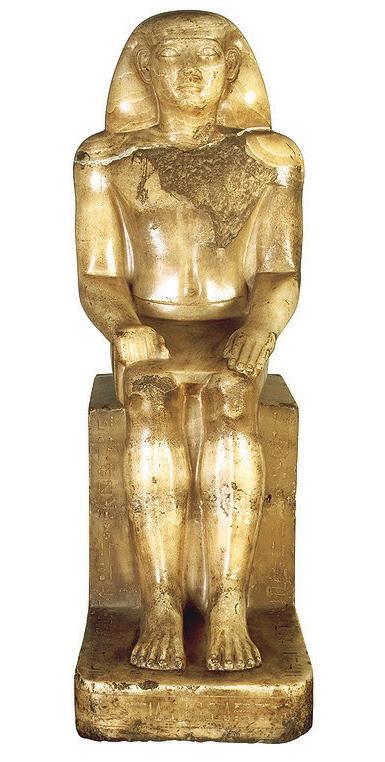

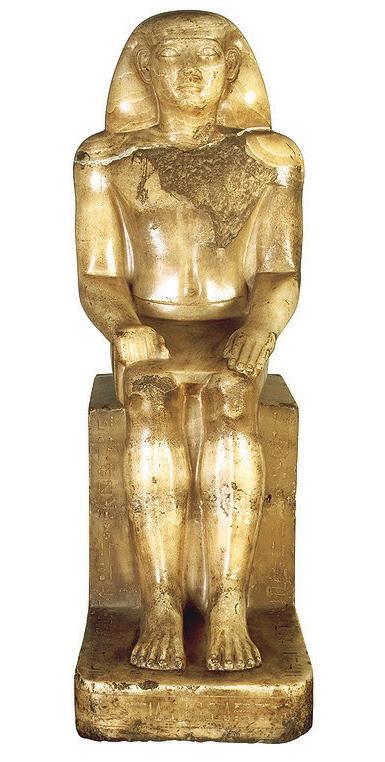

SEATED STATUE OF INEFER

EGYPTIAN, LATE PERIOD, DYNASTY XXV OR XXVI

ASWAN GRANITE

HEIGHT: 32 CM.

WIDTH: 25.5 CM.

DEPTH: 11 CM.

PROVENANCE:

SOLD IN A PUBLIC ANTIQUES SALE IN 1950-1960, LOT 41, ACCORDING TO AN EXTRACT OF THE CATALOGUE.

ACQUIRED BY MARGUERITE BORDET (1909-2014), VISUAL ARTIST. THEN IN A PARISIAN PRIVATE COLLECTION FROM 1999.

Sculpted from a single block of Aswan granite, our magnifcent sculpture represents a man seated on a throne. Without a head, his hands are resting on his thighs, the right one fat while the left is holding a piece of fabric. Our fgure is depicted bare chested, dressed only in a masculine loincloth commonly called a schenti, a traditional ancient Egyptian garment worn frst by peasants then frequently represented in sculptures of gods, pharaohs and individuals. The loincloth is made up of two superposed swathes and a triangular fap that goes down between the legs. Represented in a stylised, very symbolic way, the folds are depicted through straight lines as though squashed fat and follow the delicate curve

of the pelvis, ending just above his knees, leaving them bare. The rest of his body is also bare, revealing powerful muscles. His torso has broad, square shoulders, his arms are impressive and his chest is proudly pufed out, abdominal muscles contracted, giving our sculpture an athletic, majestic appearance. Additionally, his lower legs and feet are represented in a manner that is both symbolic and monumental. The geometric austerity, both in the composition and in the sculptor’s work, thus imbues our sculpture with a certain power and an unrivalled poise.

In ancient Egypt, when a fgure was represented, the point was not to portray them in the modern

sense of the term, but rather to depict a sublimed, timeless image that followed canons elaborated in those very ancient times. Private Egyptian statuary ofers an almost complete overview of the rich range of materials, from stone to ivory to wood, Egyptian sculptors used from the very frst dynasties. With its dark colour, the speckled granite gives depth and majesty to our delicate statue. The light marks soften the hardness of the stone and add an unparalleled ardour and human warmth. Two principles govern Egyptian art: aspectivity and frontality. The frst is a concept whereby the artist represents the defnition of the object and not its visible aspect; the second translates to the axiality and symmetry of the construction. The frst is illustrated by the fact there is a mortice in the place of the neck, allowing for a head to be inserted. The statue could thus change heads and identities, illustrating the idea of not representing the visible aspect, but an ideal that suited whoever wished to be thus identifed. Moreover, not a single physical feature individualises our statue, revealing a universal physique. The second concept is illustrated by the perfectly symmetrical and frontal aspect of our work.

The Late Period is marked by a certain instability. It is a troubled period politically because of the rise in power of various kingdoms whose infuence can be felt in the artistic production. Our sculpture can be dated more precisely to the dynasties XXV or XXVI. The last two dynasties, from 774 BC to 525 BC, were characterized by an intense intellectual

and artistic activity that sought its references in the ancient forms of the past, particularly those of the Old and Middle Kingdom. These new artistic researches give rise to eclectic works that can be qualifed as archaizing—our sculpture being a perfect example. Indeed, at frst glance, our seated statue of Inefer resembles works of the Dynasty XII, taking up the rather schematic representation of the body that we fnd, for example, in works conserved in New York (ill. 1-2). However, certain artistic liberties taken lead us to believe that our statue is in fact later, especially from acknowledging the proportions. Thus, the body of our fgure is more slender and elongated than the canons of the Middle Kingdom. In the same way, the style and way of representing the details of the limbs testify to this combination of styles and to the will of the artists of the time to create an eclectic

Ill.

Ill. 1. Seated Statue of the Steward Sehetepibreankh, Egyptian, Middle Kingdom, Dynasty XII, reign of Amenemhat II, limestone, H.: 94.5 cm. The MET, New York, inv. no. 24.1.45.

2. Seated Statue of King Senwosret I, Egyptian, Middle Kingdom, Dynasty XII, greywacke, H.: 103.5 cm. The MET, New York, inv. no. 25.6.

Ill. 1. Seated Statue of the Steward Sehetepibreankh, Egyptian, Middle Kingdom, Dynasty XII, reign of Amenemhat II, limestone, H.: 94.5 cm. The MET, New York, inv. no. 24.1.45.

2. Seated Statue of King Senwosret I, Egyptian, Middle Kingdom, Dynasty XII, greywacke, H.: 103.5 cm. The MET, New York, inv. no. 25.6.

artwork marked by the past. Fine examples of these diverse infuences during the XXVth and XXVIth dynasties are preserved in Cairo today (ill. 3-4). The original head had to be either broken or removed from the body in ancient times. The head was attached by means of a mortise carved into the bust of the fgure. A horizontal plane was carefully prepared for this purpose at the height of the neck so that a new head could be placed on the body.

Ill. 3. Seated statue of Horouda, Late Period, Dynasty XXVI, reign of Wahibre Psamtik I, limestone, H.: 78 cm. The Egyptian Museum, Cairo, inv. no. JE 37403.

Ill. 4. Seated statue of Padiamenope, Late Period, Dynasty XXV or Dynasty XXVI, reign of Wahibre Psamtik I, calcite, H.: 97 cm. The Egyptian Museum, Cairo, inv. no. CG 48620.

While the body of our fgure was painstakingly represented, there is also much delicacy and precision to be admired in the hieroglyphs adorning the stone. The seated position was an Egyptian tradition for more than 800 years. Its advantage was the fat surface it created for inscriptions, which were of a crucial importance to the Egyptians. The right side of the seat shows two standing

fgures, depicted in profle. The frst masculine fgure is depicted holding a sceptre in one hand and the same object our seated fgure is holding in the other, difcult to identify. The inscription reads: “His son who carries on his name, the divine father and prophet of Amun in northern Heliopolis, Aatj, son of the divine father Inefer, son of the divine father Imes”. The second fgure represents a woman whose inscription reads: “The mistress of the house and musician of Ra-Atum… daughter of the prophet, divine father and governor of Heliopolis, Aatj, son of Tjanefer”. The left side of the throne is decorated with four seated fgures, the frst two of whom bear inscriptions. The frst man is accompanied by the caption: “The divine father and prophet of Amun in northern Heliopolis, Aatj”, while the second is inscribed: “The divine father Inefer”. It is interesting to note that this side is partly eroded, yet the inscriptions follow the surface perfectly and have not sufered the same alterations. This shows that the inscriptions are later additions.

The identity and parentage of the person represented is indicated through two inscriptions along the belt of the loincloth and at his feet. The frst states: “It is the divine father Inefer”, and the second: “It is the divine father Inefer, son of the divine father Imes, son of the divine father Inefer”

The hieroglyphs are fnely engraved, contrasting with the monumentality of our statue. This type of statue would have been placed in the tomb of the deceased, where the family could leave oferings and say prayers.

Our magnifcent sculpture was part of the collection of the visual artist Marguerite Bordet (1909-2014), who acquired it at auction between 1950 and 1960. The extract of the French catalogue thus refers to it as lot 41: “Grey granite statue of a seated fgure, dressed in a folded loincloth […], Middle Kingdom, H: 0m32” (ill. 5). It was then added to a Parisian private collection from 1999.

Ill. 5. Extract of the sales catalogue.

Ill. 5. Extract of the sales catalogue.

AMAZON’S ARM

PROVENANCE:

FORMERLY IN THE FRENCH PRIVATE COLLECTION OF GUSTAVE CLÉMENT-SIMON (1833-1909), AT CHÂTEAU DE BACH, NAVES, C ORRÈZE.

PASSED TO GEORGES COUTURON WHEN THE CASTLE WAS SOLD IN 1938 ALONG WITH HIS ENTIRE COLLECTION. PASSED DOWN WITHIN THE SAME FAMILY THEREAFTER.

This impressive statue fragment represents a left arm holding a shield. The weapon is attached to the folded arm by a thick band around the wrist. There is also a strap with two rows of stitches over the hand, moulded to the shape of the palm. The fngers are thus curled over the thin strap, while the thumb meets the index in a gripping movement. The fngers are individualised, with space carved between them for added realism. The nails, with fnely carved contours, are also faithfully represented. The shield is in the shape of a crescent moon, making it a very particular type of shield called a pelta. It is known to have had two diferent shapes: the crescent moon shape with only one semicircular notch, or two notches. In mythology, this type of shield was

wielded by the Amazons, a tribe of female warriors. By their shape, small size and lightness, the shields were adapted to the female morphology. On the inside, the shield has one or several handles as well as straps, allowing it to be worn across the back. It has consequently been attributed to the Amazons, equestrians who strapped their shields across their backs. The artist’s mastery is evident in the attention to detail, as well as their desire to ground their work in such realism. It is only accentuated by the large size of this anatomic fragment — almost life-sized –which, despite its subject, presents an incomparable gentleness. This very lovely marble is adorned with an old patina, which attests to the passing of time and gives it a most poetic appearance.

1 ST - 2 ND CENTURY

ROMAN,

AD MARBLE

HEIGHT: 40 CM.

WIDTH: 48 CM.

DEPTH: 12 CM.

During antiquity, the theme of the Amazons was frequently represented, particularly in Greek art and in Rome. As they were female warriors, their well established iconography is particular and specifc to them: they are depicted wearing short tunics called chiton, the same type as that worn by the hunter goddess Artemis, the only female deity to wear a short garment. Very often, part of their anatomy is bared (a breast, a shoulder or a foot), while, in the Hellenistic period, there were representations of completely nude Amazons.

The iconographic themes in which they appeared varied little: Amazonomachy, the fght opposing Greeks and Amazons, or the fght that opposed them to Hercules. As the subject was very popular in Greek and Roman art, artists delighted in using it to express their virtuosity on all kinds of supports. There are thus images of Amazons in a variety of media, such as paintings (ill. 1-3) and sculptures in bas relief (ill. 4-5), haut relief (ill. 6-7) and in the round (ill. 8). While the last category is rarer, there is a fragmentary sculpture that is thought to represent an Amazon (ill. 9). Found in the peristyle court adjoining the theatre of Corinth, built in the early 2nd century AD, the statue is believed to have been part of a complex iconographic set. The work, almost true to scale (H.: 160 cm, supposed total H.: 189 cm), represents a young woman wearing a chiton secured by a broad belt around her waist and two bands crossing over her chest, as well as knee high laced boots. She is standing in a classic contrapposto position. The work is fragmentary,

but it seems her left arm was slightly raised and folded, holding an object that worked as a counterweight. It is possible, then, that our arm fragment belonged to that statue — or, at least, that it is an example of that statuary type.

Ill. 1. Oinochoe attributed to the Mannheim Painter, depicting Amazons in combat, Greek, Attic, ca. 440 BC, terracotta. The MET, New York, inv. no. 06.1021.189.

Ill. 2. Kylix fragment with an Amazon and her shield, Greek, ca. 515 BC, terracotta. Musei Vaticani, inv. no. MV.35101.0.0.

Ill. 3. Fragmentary kylix with an Amazon and her shield, Greek, ca. 520-500 BC, terracotte. Musei Vaticani, inv. no. MV.17845.0.0.

Ill. 4. Oil lamp decorated with an Amazon, Roman, 3rd century AD, clay. Musée du Louvre, Paris, inv. no. CA 694.

Our superb anatomic fragment was once part of the collection of Gustave Clément-Simon (1833-1909).

A magistrate by training and a public prosecutor for the appeals court in Aix en Provence, he acquired the Château de Bach in Naves in 1879 and devoted the last 30 years of his life to historical research and amassing a collection in his castle (ill. 10). His property in Corrèze contained his vast collection of archives and his eclectic collection of artworks, including an “archaeology gallery”.

In the monograph on the town of Naves published in 1905, Victor Forot stated that Gustave Clément-Simon “travelled widely (Italy, Greece, Turkey) and brought artworks back, unfortunately uncategorised”. In 1938, the entire collection was sold to Georges Couturon along with the rest of the castle and all its furniture, then passed down.

Ill. 7. Relief of the temple of Apollo Epikourios at Bassai depicting a battle between the Amazons and the Greeks, Greek, ca. 420-400 BC, marble. British Museum, London, inv. no. 1815,1020.23.

Ill. 5. Campana plaque depicting an Amazonomachy, Roman, 1st century BC-1st century AD, clay. Musée du Louvre, Paris, inv. no. S 6609.

Ill. 6. “Viennese” sarcophagus decorated with an Amazonomachy, 19th century plaster casting based on a Greek original, 4th century BC. Musée du Louvre, Paris, inv. no. Gy 0416.

Ill. 8. Wounded Amazon, Roman, 2nd century AD after a Greek original ca. 450-425 BC attributed to Kresilas, marble. Musei Vaticani, inv. no. MV.2252.0.0.

Ill. 9. Statue of an Amazon(?), Roman, probably from the early Antonine period, ca. AD 138-160, marble. Archaeological Museum of Ancient Corinth, inv. no. S 3723.

Ill. 10. Alexandre Bertin, Portrait of Gustave Clément-Simon, 2nd half of the 19th century, once in the library at Château de Bach, H.: 171 cm. Musée du Cloître, Tulle, inv. no. MC.2010.0.10.

Ill. 7. Relief of the temple of Apollo Epikourios at Bassai depicting a battle between the Amazons and the Greeks, Greek, ca. 420-400 BC, marble. British Museum, London, inv. no. 1815,1020.23.

Ill. 5. Campana plaque depicting an Amazonomachy, Roman, 1st century BC-1st century AD, clay. Musée du Louvre, Paris, inv. no. S 6609.

Ill. 6. “Viennese” sarcophagus decorated with an Amazonomachy, 19th century plaster casting based on a Greek original, 4th century BC. Musée du Louvre, Paris, inv. no. Gy 0416.

Ill. 8. Wounded Amazon, Roman, 2nd century AD after a Greek original ca. 450-425 BC attributed to Kresilas, marble. Musei Vaticani, inv. no. MV.2252.0.0.

Ill. 9. Statue of an Amazon(?), Roman, probably from the early Antonine period, ca. AD 138-160, marble. Archaeological Museum of Ancient Corinth, inv. no. S 3723.

Ill. 10. Alexandre Bertin, Portrait of Gustave Clément-Simon, 2nd half of the 19th century, once in the library at Château de Bach, H.: 171 cm. Musée du Cloître, Tulle, inv. no. MC.2010.0.10.

HEAD OF AN EMPEROR

ROMAN, ANTONINE DYNASTY, AD 96-192

MARBLE

HEIGHT: 34 CM.

WIDTH: 24.5 CM.

DEPTH: 22 CM.

PROVENANCE:

IN A EUROPEAN COLLECTION FROM THE 18 TH OR 19 TH CENTURY, BASED ON THE OLD RESTORATION TECHNIQUES.

IN A FRENCH COLLECTION FROM THE BEGINNING OF THE 20 TH CENTURY, JUDGING BY THE BASING TECHNIQUE.

THEN IN A FRENCH PRIVATE COLLECTION IN A RESIDENCE IN VAUCLUSE, FRANCE.

This sumptuous sculpted portrait represents a Roman emperor. His fne featured face is fnished of with thick hair and facial hair. His extremely smoothly shaped forehead contrasts with his large, deeply carved eyes. His very thick lower and upper eyelids frame his almond-shaped eyes, which have incised irises etched in their centres and drilled pupils. They are surmounted by a fne, discreet brow line and very thin eyebrows that start at the bridge of his nose and extend almost to his temples. Beneath his eyes, there are hollows at the junctures of his cheekbones, accentuated by his very thick lower eyelids. His nose, now broken, was probably narrow and well proportioned. It dovetails with a rather big mouth, although the lips are thin and

partly concealed by his moustache, which joins a thick beard covering the entire lower part of his face. His very discreet cheekbones, too, are partly hidden by his beard, which starts at the middle of his cheeks and gets thicker as it goes, covering his chin and the top of his neck. The strands are almost individually shaped, refecting a deep desire for realism, and they are grouped here and there, representing wavy locks. His neck is thick and muscled, as wide as his face with slight bulges that correspond to the diferent muscles, showcasing a certain physical strength.

Thick, curly hair puts the fnishing touch to the portrait. It is made up of individualised locks that are messily tangled, giving our portrait a striking

realism and appearance of life. The considerable volume of the hair is due to the way the groups of locks were separately shaped, and especially the use of a drill, which makes it possible to carve down into the marble, simultaneously creating plays of shadow and light. The importance given to the hair indicates that it is a key element in deciphering this portrait. The ears are clearly visible, as only their tips are hidden by his hair. Perfectly proportioned, these, too, attest to the attention to realism that guided the sculptor in their creation. On the back of the head, there are traces of old restoration work. The technique is characteristic of the European craftsmen of the 18th and 19th centuries. We can thus infer that this magnifcent portrait was in a European collection at that time. It would then have belonged to a French collection at the beginning of the 20th century, judging by the rather particular basing technique.

This portrait is admirable on more than one level. More than its aesthetic qualities, the model appears to have been a relatively young man who was portrayed with physical characteristics generally reserved for more mature men, following the iconographic traditions of ancient Roman art. In ancient Rome, beards were worn by young adults, then shaved and ofered to the gods from the age of 24.

While the tradition of Roman portraits was very codifed from its inception, it is still possible to see an evolution, particularly with Emperor Hadrian’s assumption of power in AD 117. He was the frst to

grow a beard, following the trend of the philosophers, which then became the fashion at court. Four years after being named emperor, Hadrian was named eponymous archon, or, in other words, supreme magistrate of the city of Athens, the reason for his particular taste for Greek culture. When he rose to power in Rome, he was soon nicknamed greculus, “the little Greek”, by his peers. In his portraits, his beard thus has a moral connotation recalling Greek identity. The tradition of bearded portraits swiftly spread through the Empire and was no longer limited to philhellenes. The circulation of many portraits and coins bearing Hadrian’s efgy was unquestionably behind the new style of representation, which was adopted by all of Hadrian’s successors in the Antonine dynasty: Antoninus Pius, Marcus Aurelius (who was, incidentally, the frst to grow a long beard) and Commodus.The major novelty in these portraits, besides the beard, is the more detailed, carved shaping of the hair and eyes. Representing the pupils with carved circles was also a novelty that commenced under Hadrian’s reign.

Ill. 1. Portrait bust of Hadrian, Roman, Athens, ca. AD 130, marble. National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Ill. 2. Colossal portrait of Hadrian, Roman, AD 130-138, marble, H.: 55 cm. National Archaeological Museum, Athens.

Finally, the detailed locks of hair coupled with the use of a drill indicate that this portrait was the work of a Roman craftsman.

Our magnifcent bearded head, idealised and noble, thus represents an emperor from that dynasty whose identity cannot be pinpointed. If we compare it with very fne examples such as the two portraits of Hadrian conserved in Athens (ill. 1-2), those of Antoninus Pius in New York and Berlin (ill. 3-4), those of Marcus Aurelius in London and Paris (ill. 5-6) and those of Commodus in Copenhagen and London (ill. 7-8), we can easily glimpse many similarities in the facial features and the way the hair and beard are represented.This luxurious portrait, a similar example of which was sold at Sotheby’s in 2021 (ill. 9), is sculpted from particularly fne grained marble, allowing for an absolutely perfect polishing. The practically immaculate white stone has a few concretions and a very slight patina, which only add to its elegance.

Ill.

Ill.

Ill.

Ill. 5. Portrait bust of Marcus Aurelius, Roman, ca. AD 160 170, H.: 73.5 cm. The British Museum, London, inv. no. 1861,1127.15.

6. Portrait of Marcus Aurelius, Roman, Asia Minor, 3rd quarter of the 2nd century AD (after 161), marble, H.: 27 cm. Musée du Louvre, Paris, inv. no. Ma 4884.

Ill. 7. Portrait of Commodus, Roman, late 2 nd century AD, marble, H.: 26 cm. Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen.

8. Portrait of Commodus, Roman, ca. AD 185-190, marble, H.: 38 cm. British Museum, London, inv. no. 1864,1021.9.

9. Masculine portrait, Roman, reign of Antoninus Pius, mid 2nd century AD, marble, H.: 29 cm. Private collection.

Ill. 3. Marble portrait of the emperor Antoninus Pius, Roman, ca. AD 138-161, marble, H.: 40 cm. The MET, New York, inv. no. 33.11.3.

Ill. 4. Portrait of Antoninus Pius, Roman, mid 2 nd century AD, marble. Staatliche Museen, Berlin.

TORSO OF SILVANUS

ROMAN, CIRCA 2 ND CENTURY AD

MARBLE

HEIGHT: 60.5 CM.

WIDTH: 38 CM.

DEPTH: 23 CM.

PROVENANCE:

BRUMMER GALLERY COLLECTION, NEW YORK, ACQUIRED BY 1948.

SOLD BY SPINK & SON AND GALERIE KOLLER, “ THE ERNEST BRUMMER COLLECTION: ANCIENT ART”, VOL. II, ZURICH, 16-19 OCTOBER 1979, LOT 638. SOTHEBY’S NEW YORK, “ ANTIQUITIES”, 9 DECEMBER 1981, LOT 231.

SOTHEBY’S NEW YORK, “ ANTIQUITIES”, 14 DECEMBER 1993, LOT 73. THEN AMERICAN PRIVATE COLLECTION. SOTHEBY’S NEW YORK, “ ANTIQUITIES, PROPERTY FROM AN AMERICAN PRIVATE COLLECTION”, 14 DECEMBER 1994, LOT 82. THEN IN THE COLLECTION OF EVELYN AIMIS FINE ART, DELRAY BEACH, FLORIDA. THEN PROPERTY OF A PRIVATE COLLECTION, ACQUIRED FROM THE ABOVE IN 1999.

This striking marble torso depicts the Roman god Silvanus, patron of the forest and uncultivated lands. Our majestic statue is made of a white marble that has elegantly aged in time with a refned aura. The brown patina decorates the left shoulder all the way down to the back of the left thigh, displaying the efects of time on the marble. Originally with a head, our sculpture now presents a sophisticated manner. The nude torso is gently carved in a contrapposto position with a pronounced v-line, subtle abs, and

prominent pecs, giving a youthful appearance. The backside of the torso reveals stifened shoulders thus contributing to the torso’s defned muscularization.

Here, Silvanus stands in an upright and fexed posture, giving him an almost confdent attitude. Tied to his right shoulder is an animal skin that gently drapes over his left shoulder and arm. The delicate and life-like folds in the drapery attests to the artist’s pursuit to depict the god realistically.

His left arm is bent, holding a cornucopia full of grapes, apples, and other fruits, symbolizing a bountiful harvest.

Silvanus, whose name translate to “of the woods” was a Roman tutelary deity. God of the forests, Silvanus protects shepherds and labourers, ensuring their health and the prosperity of their focks. Along with the Lares, Faunus and other woodland deities, he was one of the protectors of rural domains and was widely worshipped from the end of the Republican era. This rustic god did not have any temples or holidays dedicated to him; however, his popularity rose during the 2nd century AD under the rule of Emperor Hadrian. During his reign, Hadrian decorated his countryside villa with numerous Silvanus statues to express his passion for hunting. The god’s image was also used later in agricultural campaigns. Numerous works of Silvanus have survived throughout the centuries.

Full depictions of Silvanus commonly show the god with a muscular body, animal skin drape, bundle of fruits, and a luscious beard, as is the case for the sculpture in Berlin and the one in Rome (ill. 1-2). Similar to ours, there is another torso of Silvanus sharing the same attributes—animal skin and cornucopia— housed in Algeria (ill. 3). A last one with the same iconography was part of the collection of Mr. Mariaud de Serre (ill. 4).

Ill. 1. Statue of Silvanus, Roman, 2nd century AD, marble, H.: 195 cm. Antikensammlung, Berlin, inv. no. Sk 282. Ill. 2. Silvanus, Roman, 2nd century AD, marble, H.: 44.4 cm. Museo Nazionale Romano, Baths of Diocletian, Rome.

Our torso once belonged to the Brummer Gallery in New York. Joseph (1883-1947), Imre (1889-1928), and Ernest (1891-1964) Brummer were major art dealers widely specialized from classic antiquity to modern art (ill. 5-6). Born in Austria-Hungary, the brothers moved to Paris and opened their frst gallery in 1906. Shortly after, in 1914, Joseph and Imre moved to New York to open another gallery (ill. 7).

Ernest joined his brothers in New York following the outbreak of the First World War. It was at the Brummer’s gallery in New York that our torso was

Ill. 3. Silvanus, Roman, between 1st - 3rd century AD, marble, H.: 62 cm. National Museum of Antiquities, Algiers. Ill. 4. Torso of Silvanus, Roman, 2nd century AD, marble, H.: 74 cm. Ex-Mariaud de Serre collection.

proudly displayed. Indeed, several photographs dated back from 1948 show our Silvanus posed next to a case flled with numerous bronzes (ill. 8).

After Joseph’s death in 1947, Ernest began selling most of the collection in New York auctions in 1949 and later in London and Paris. In 1979, the torso was auctioned in Zurich as part of the “The Ernest Brummer Collection”. Then by Sotheby’s in 1981 and again in 1993. Within a year, the Silvanus was sold from a private American collection at Sotheby’s in 1994 before joining a private collection in 1999.

Publications:

- The Ernest Brummer Collection Ancient Art, Vol. II, Spink & Son and Galerie Koller, Zurich, 16-19 October 1979, lot 638.

- Sotheby’s New York, Antiquities, 9 December 1981, lot 231.

- Sotheby’s New York, Antiquities, 14 December 1993, lot 73.

- Sotheby’s, New York, Antiquities: Property from an American Private Collection, 14 December 1994, lot 82.

Ill. 5. Joseph and Imre Brummer, 1917. The MET: Watson Library Digital Collections.

Ill. 6. Ernest Brummer. The MET: Watson Library Digital Collections.

Ill. 7. Brummer Gallery, New York, 1925. The MET: Watson Library Digital Collections.

Ill. 8. Our torso in the Brummer Gallery, 1948. The MET: Watson Library Digital Collections.

CINERARY URN

ROMAN, 1 ST CENTURY AD

MARBLE

PROVENANCE: BY TRADITION, FOUND IN CAPUA.

IN THE COLLECTION OF THE ART DEALER RAFFAELLO BARONI, NAPLES. THEN FORMER COLLECTION OF ROBERT BERKELEY (1794-1874), SPETCHLE Y PARK, WORCESTER, ENGLAND, ACQUIRED IN JUNE 1851 FROM THE ABOVE. BY DESCENT IN THE SAME FAMILY.

This marble cinerary urn is exquisitely decorated on all four sides, as well as the cover. The front represents an interlace of plant motifs commonly called scrolls. Branches burst out of a large crater and twine around each other, ending in large fowers with rounded petals for those in the lower part and pointed petals for the two in the upper part. Large leaves unfold, following the movement of the branches and creating a rather spectacular play of curves and reverse curves. A central trunk surmounted by a pine cone motif also surges vertically from the crater, structuring the whole design. Finally, the scrolls are decorated with various creatures: a winged fgure playing pan pipes is sitting on one branch while various birds inhabit

the scrolls. The periphery of the scene is decorated with classical geometric motifs. The sides are also lavishly decorated with plant motifs: large leaves unfurl from a central branch, while the whole design is surrounded by serrated leaves. Once again, both panels are framed with regular geometric motifs, which give a sense of structure. Likewise, the back of the urn displays a signifcant ornamental repertory. Again, scroll motifs burst out of a crater and criss cross in a more disorderly way. Large, heart-shaped leaves and round fruit thus occupy all of the space. Finally, the cover displays an abundant plant repertory. Scrolls burst from the forets sculpted at the corners, unfolding in volutes and ending in four petal fowers. Lastly, a fower is sculpted in the

HEIGHT: 26 CM.

WIDTH: 36.5 CM.

DEPTH: 29 CM.

centre and framed with three borders of abstract geometric motifs. On the underside of the cover, there is still a collection label with the inked words: Grecian Sarcophagus/from Capu (ill. 1).

of the mausoleum show an interlace of acanthus leaves, wreaths and ivy, peopled with animals such as lizards and birds. Magnifcent examples of urns using that very decorative repertory are currently conserved in museums in Paris, Cologne, the Vatican and the United States (ill. 3-7).

In ancient Rome, there were two main burial rites, inhumation and cremation. From the Republican period, cremation was predominant. Urns were frst made of terracotta and then marble. They became ubiquitous from the reign of Augustus. Their decoration was increasingly meticulous and detailed and reached its height in the 1st and 2nd centuries AD. The decorative repertory was quite common: wreaths of fruit, interlaced scroll motifs, fowers, various creatures and animals and motifs linked to funeral rites such as bucrania (ox skulls). These motifs were symbolic of human hopes regarding life after death and the soul’s journey to luxuriant funerary gardens. These decorative elements on funerary urns would adorn the monuments of ancient Rome over the centuries. The Ara Pacis Augustae, for instance, a monument Emperor Augustus had built between 13 and 9 BC, is one of the best known examples of a monument decorated with particularly detailed scrolls. It signifcantly infuenced the decoration of cinerary urns at the time (ill. 2). Similarly to our urn, the panels

Ill. 2. Ara Pacis, 13-9 BC, marble. Rome.

Ill. 3. Cinerary urn, Roman, 1st century AD, marble, H.: 38.5 cm. Musée du Louvre, Paris, inv. no. Ma 1604.

Ill. 1. Collection label on the underside of the cover.

Ill. 4. Cinerary urn, Roman, 2nd century AD, marble, H.: 33 cm. Römisch-Germanisches Museum, Cologne, inv. no. 164. Ill. 5. Cinerary urn, Roman, 1st - 2nd century AD, marble, H. : 22.5 cm. Museo Gregoriano Profano, Vatican, inv. no. 10519.

Ill. 6. Cinerary urn, Roman, 1st century AD, marble, H.: 22 cm. Museo Gregoriano Profano, Vatican, inv. no. 10577.

Ill. 7. Cinerary urn, Roman, 1st century AD, marble, H.: 35.5 cm. RISD Museum, Rhode Island, inv. no. 46.083.

Ill. 2. Ara Pacis, 13-9 BC, marble. Rome.

Ill. 3. Cinerary urn, Roman, 1st century AD, marble, H.: 38.5 cm. Musée du Louvre, Paris, inv. no. Ma 1604.

Ill. 1. Collection label on the underside of the cover.

Ill. 4. Cinerary urn, Roman, 2nd century AD, marble, H.: 33 cm. Römisch-Germanisches Museum, Cologne, inv. no. 164. Ill. 5. Cinerary urn, Roman, 1st - 2nd century AD, marble, H. : 22.5 cm. Museo Gregoriano Profano, Vatican, inv. no. 10519.

Ill. 6. Cinerary urn, Roman, 1st century AD, marble, H.: 22 cm. Museo Gregoriano Profano, Vatican, inv. no. 10577.

Ill. 7. Cinerary urn, Roman, 1st century AD, marble, H.: 35.5 cm. RISD Museum, Rhode Island, inv. no. 46.083.

Our cinerary urn was acquired by Robert Berkeley during his trip in Naples on Wednesday 11 June 1851 to Rafaello Baroni, an antique dealers of the Strada Constantinopoli. Berkeley mentions it on his honeymoon journal: “Wednesday June 11 [Naples] - Bought of Rafaello Baroni dealer in antiquities in the Strada Constantinopoli an antique marble bust of Antoninus Pius - He asked 500 dollars I ofered 200 which he eventually took on condition that I bought a terracotta Etruscan sarcophagus & a marble sepulchral urn - The latter cost respectively 25 & 30 dollars - I gave 6 for the packing & transport to Turners bank - ... - The urn he declares to have heen found in a columbarium at Capua. The sarcophagus has an inscription in Etruscan characters - We preferred the urn to a bas relief on which I had at frst decided” (ill. 8).

The urn is mentioned again in their 1949 inventory: “[…] Two marble Roman [sic] cinerary urns and covers, rectangular shape, 14½” x 12” (one cover cracked)”. The Berkeley family is an ancient English noble family that owns Spetchley Park in Worcestershire (ill. 9). The residence was purchased by Rowland Berkeley in 1605, but was burnt down at the Battle of Worcester in 1651. The Palladian house we know today, with its Ionic portico, was built in 1811 by a descendent, Robert Berkeley (1764-1845). The project, which was both colossal and extravagant, was carried out in harmony with Robert’s desire to decorate the interior tastefully: portraits of ancestors, sculptures probably acquired on a Grand Tour, furniture, wallpaper from China and antique sculptures. In 1830, the estate was transferred to his son, Robert Berkeley (1794-1874), who continued to develop and decorate the residence. With his son, Robert Martin Berkeley, they sustained their love for art and established the Spetchley private museum in the 1840s (ill. 10). The collections continued to grow under Rose and Robert Valentine Berkeley,

Ill. 8. Robert Berkeley Honeymoon Journal, 1851.

Ill. 8. Robert Berkeley Honeymoon Journal, 1851.

then John Berkeley. The urn remained at Spetchley Park, passed down as an heirloom, until now.

Ill. 9. Spetchley Park, Worcester, England.

Ill. 10. Drawing-room and Staircase Hall, Spetchley Park in Country Life, 8 July 1916, vol XL, no. 1018, p. 45-46.

Ill. 9. Spetchley Park, Worcester, England.

Ill. 10. Drawing-room and Staircase Hall, Spetchley Park in Country Life, 8 July 1916, vol XL, no. 1018, p. 45-46.

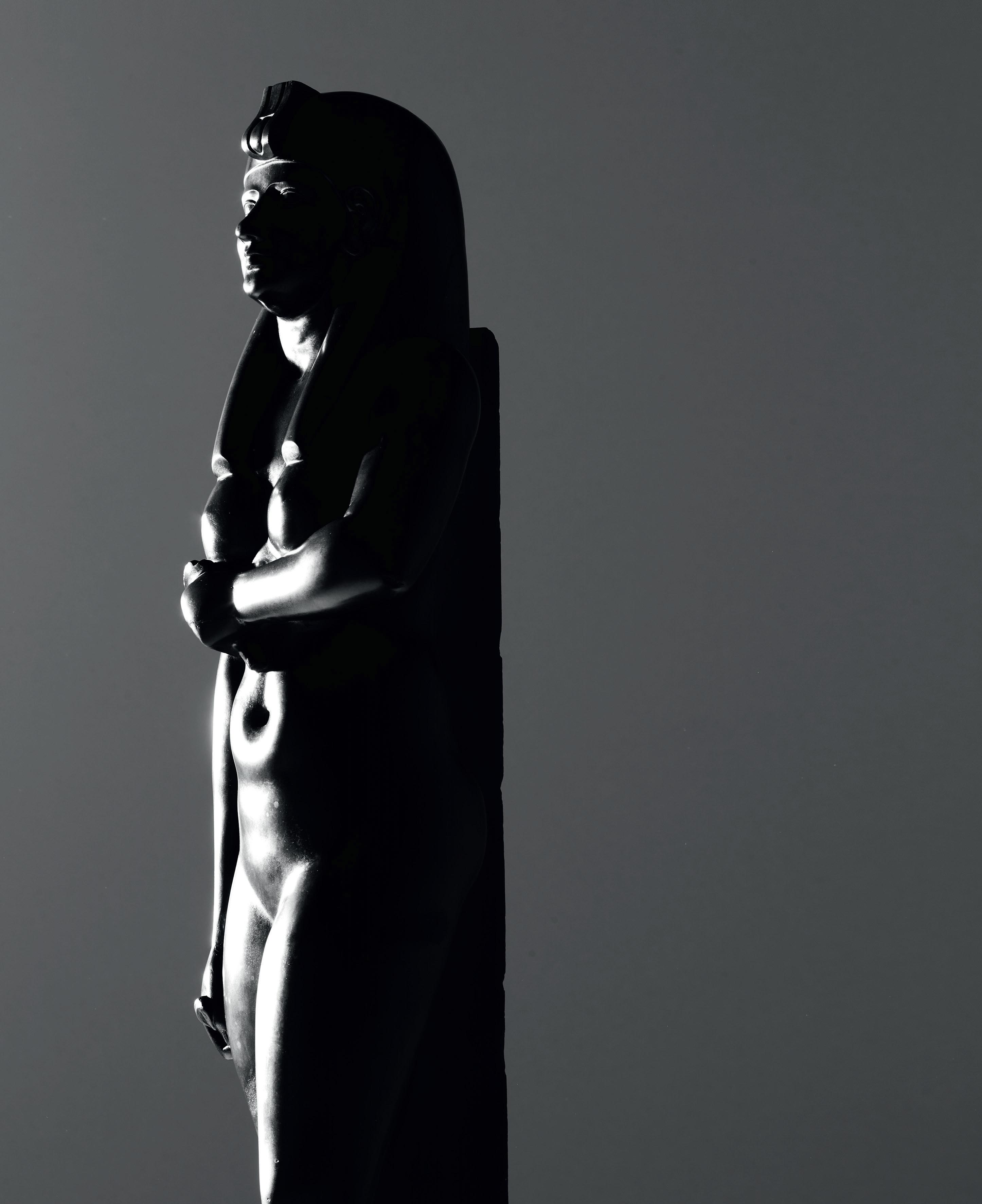

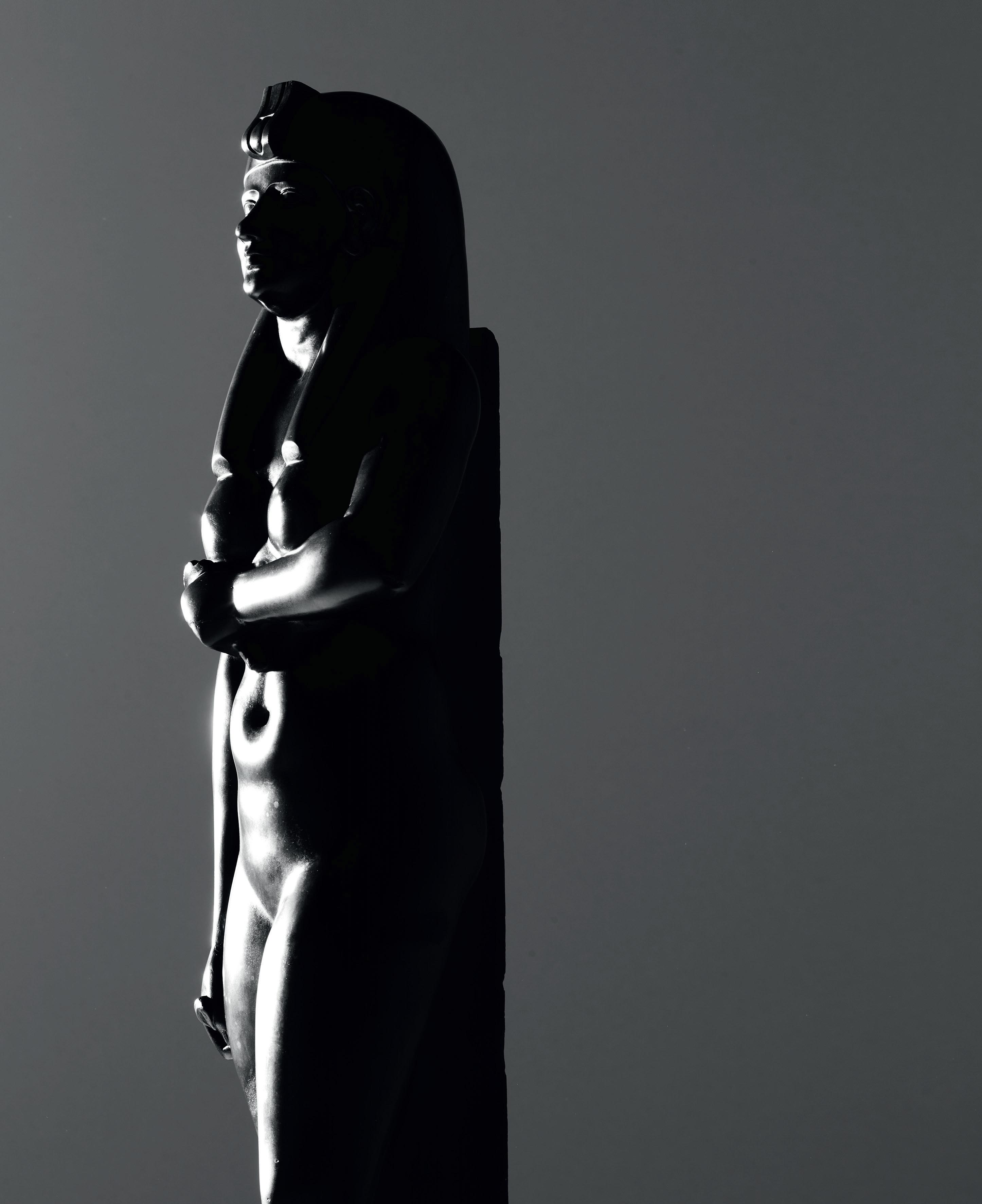

TORSO OF APHRODITE OF KNIDOS

ROMAN, CIRCA 2 ND CENTURY AD

PROVENANCE:

FORMER EUROPEAN COLLECTION SINCE AT LEAST THE 18 TH - 19 TH CENTURY BASED ON THE OLD RESTORATIONS TECHNIQUE. THEN IN THE COLLECTION OF COMMANDER PAUL LOUIS WEILLER (1893-19 93)

SINCE AT LEAST 1948.

This elegant torso represents Aphrodite, Greek goddess of love and beauty, known to the Romans as Venus. Born from sea foam, the deity was widely represented in the Greek then Roman worlds as the symbol of femininity and sensuality. Our magnifcent, life-sized sculpture alludes to the mythological scene in which the nude goddess was surprised bathing. The sculptor was able to showcase the deity’s elegant curves through the slight forward tilt of her bust and the tilt of her hips, characteristic of contrapposto. The harmonious proportions are particularly striking, with fne

shoulders, small, round, closely spaced breasts, a slight waist and widening hips forming a perfect balance. The positioning of her left shoulder enables us to infer that the goddess’s arm was raised to the side, while her right shoulder, which is lower, dovetails with the beginning of an arm that undoubtedly lay along her body. A small excess of fesh between her right breast and shoulder attests to the sculptor’s desire for realism, as do the very slight creases to either side of the neck, intricately depicting her collarbones. Her very smooth abdomen, which has a barely perceptible

MARBLE

RESTORATION.

HEIGHT: 78 CM.

WIDTH: 35 CM.

DEPTH: 23 CM.

line running down the middle, as well as her navel, fully carved and portrayed in depth, again display the artist’s technical mastery. The pubis is not represented in detail, but we may infer that the goddess was shielding it with one of her hands. The fold of her groin is, however, clearly visible upon her right leg, which, judging from the position of the bust, was the goddess’ supporting leg. Her back, once again most elegantly sculpted, displays a line carved vertically down the middle, following the general curve of the body. Both shoulder blades subtly stand out and bring our sculpture to life by giving the shoulders a sense of movement. Two small dimples mark the small of the goddess’ subtly muscled back. Her buttocks, perfectly round and delicately shaped, are separated by a deep furrow, while a slight fold is visible to the right, representing the transition between buttock and thigh. At the very top of the back, at the junction with her neck, the remnant of a lock of hair is just visible. The goddess’ hair was undoubtedly up in an elegant chignon, from which some thick locks of curly or wavy hair would have escaped.Narrow shoulders, slightly contracted muscles, a small bosom, a slight, delicate waist, an ample pelvis and the curve formed by her back are just a few details used by the artist to illustrate the beauty and sensuality of the female body. All the femininity and sensuousness inherent to the goddess of love and beauty emanate from her spellbinding, elegant form.

4th century BC: the Aphrodite of Knidos, one of the most renowned models in antiquity. It was the frst representation of a female nude.

Our elegant Venus was inspired by a Greek original sculpted by the Athenian sculptor Praxiteles in the

In keeping with ancient tradition, Praxiteles is said to have crafted two statues of Aphrodite, each with perfect proportions, one clothed and one nude. The frst was purchased by the city of Kos, while the second was chosen by the inhabitants of Knidos to adorn the goddess’ sanctuary in which, by way of a second door, it could be observed from all angles. The Aphrodite of Knidos model was thus a fgure of the nude goddess having fnished her bath, standing, dropping her garment over a vase placed on the ground. Her folded right arm holds a cloth, while her left hand shields her sex in a gesture traditionally interpreted as modest. The position of the shoulders of our magnifcent sculpture leave very few doubts as to the arrangement of the arms, as does her bosom, which seems to be sculpted along the same horizontal line. Consequently, as for the complete examples of Praxiteles’ work, the movement of the arms only slightly — or not at all,

Ill. 1. Torso of the Aphrodite of Knidos, Roman, Imperial period, 2nd century AD, marble, H.: 121 cm. Musée du Louvre, Paris, inv. no. Ma 2184.

in some cases — impacts that of the breasts, which stay at the same level, contrary to anatomic reality. Moreover, the contrapposto sets the left leg in motion while the right is immobile, as is the case for all the other known examples of the Aphrodite of Knidos (ill. 1-3). Furthermore, the movement of the shoulders, sloping forwards slightly, gives her a delicately stooped posture.

appearance. The choice of this very fne grained marble bestows upon the goddess an incomparable sensuality and grace. The very light patina on the marble distinguishes itself as a major testament to the passing of time.

Our superb torso of Aphrodite was once in the collection of Paul-Louis Weiller (1893-1993), aviation hero during the First World War and businessman thereafter (ill. 4). Behind the biggest aeroplane engine construction business in Europe, he also created airlines that would shortly be nationalised to become Air France. As a Jewish Alsatian, he fed France for Cuba and Canada during the Second World War. Upon his return, he became a great patron of the arts, namely contributing to the restoration of the Palace of Versailles, establishing a ballet company, supporting many artists and actors and amassing a sizeable collection of more than 750 artworks. In 1965, he was elected to the

As it enjoyed immense popularity, we know several examples of this work, despite the fact the original is now lost. In his work Natural History, Pliny the Elder (Book XXXVI, 6, 9) wrote that the statue was not only the sculptor Praxiteles’ most beautiful, but also the most beautiful in the world. Incidentally, Pliny added that the statue was “visible from every angle”, which explains why our Aphrodite’s back and buttocks are so well shaped. The white marble in which our Aphrodite is sculpted is gorgeously polished, not to mention a very delicate milky colour, giving her a youthful

Ill. 2. “Belvedere Venus”, Roman, 1st-2nd century AD, marble. Museo Pio Clementino, Vatican, inv. no. 4260. Ill. 3. Statuette of Aphrodite, the Aphrodite of Knidos type, Roman, 1st-2nd century AD, marble. The MET, New York, inv. no. 42.201.8.

Ill. 4. Paul-Louis Weiller, photograph taken on the occasion of his election to the Académie des Beaux-Arts in Paris on 24 February 1965.

Académie des Beaux-Arts. Upon his death, his collection would be sold twice, in 1998 and 2011. According to original documents signed by Paul-Louis Weiller (ill. 5), the torso was ftted to a marble base in about December 1948 and seen by Jean Charbonneaux, curator at the Musée du Louvre, at Paul-Louis Weiller’s residence in March 1948. In a letter addressed to the latter, the curator marvelled at the quality of the sculpture and expressed his satisfaction at seeing such a work remain in France (ill. 6).

Ill. 5. Letter from Paul-Louis Weiller to Mr Benezech, stonemason, dated 10 December 1948, accompanied by a photograph of the work on its old wooden base.

Ill. 6. Handwritten letter from Jean Charbonneaux, curator at the Musée du Louvre, addressed to Paul-Louis Weiller, dated 15 March 1948.

Ill. 5. Letter from Paul-Louis Weiller to Mr Benezech, stonemason, dated 10 December 1948, accompanied by a photograph of the work on its old wooden base.

Ill. 6. Handwritten letter from Jean Charbonneaux, curator at the Musée du Louvre, addressed to Paul-Louis Weiller, dated 15 March 1948.

FUNERARY ALTAR OF CAIUS COMISIUS HELPISTUS

ROMAN, 1 ST CENTURY AD

MARBLE

HEIGHT: 74 CM.

WIDTH: 64.5 CM.

DEPTH: 46 CM.

PROVENANCE:

FORMERLY IN THE COLLECTION OF CARDINAL DOMENICO PASSIONEI (1682 -1761).

PASSED DOWN AS AN HEIRLOOM IN THE COLLECTION OF HIS NEPHEW, BENEDETTO PASSIONEI (1719-1787), FOSSOMBRONE, ITALY.

THEN IN THE COLLECTION OF BARTOLOMEO CAVACEPPI (1716-1799), ROM E.

ACQUIRED BY THOMAS ANSON (1695-1773), SHUGBOROUGH HALL, STAFFOR DSHIRE. BY DESCENT TO HIS GREAT NEPHEW THOMAS ANSON (1767-1818), 1 ST VISCOUNT ANSON. SOLD BY GEORGE ROBINS, “ THE SPLENDID PROPERTY OF EVERY DENOMINATION APPERTAINING TO SHUBOROUGH HALL”, 1 AUGUST 1842, LOT 50.

PROBABLY ACQUIRED IN THAT SALE BY WILLIAM LOWTHER (1787-1872),

2 ND EARL OF LONSDALE, LOWTHER CASTLE, PENRITH, CUMBRIA. PASSED DOWN AS AN HEIRLOOM WITHIN THE FAMILY UNTIL

LANCELOT LOWTHER (1867-1953), 6 TH EARL OF LONSDALE, LOWTHER CASTLE.

PROBABLY SOLD BY MAPLE & CO. LTD AND THOMAS WYATT, “ LOWTHER CASTLE [...].

THE MAJOR PART OF THE EARL OF LONSDALE’S COLLECTION”, 29 APRIL – 1 MAY 1947. THEN IN AN ENGLISH PRIVATE COLLECTION, ACQUIRED AT THE END OF THE 1940S – BEGINNING OF THE 1950S. PASSED DOWN AS AN HEIRLOOM IN THE SAME FAMILY UNTIL THE PRESENT DAY.

This exceptional marble altar, rectangular in shape, is decorated on all four sides. The frst is undoubtedly the panel with the richest iconographic repertory. A thick festoon composed of fruit and leaves is suspended, ends tucked into the top two corners of the panel. Each element is sculpted in high relief and individualised, the marks made by the drill creating a play of depth that contrasts with the elements sculpted in lower relief. Delicate knotted ribbons fall to the ground, the folds of fabric giving a striking impression of thickness and realism. Two winged putti are sculpted at the corners. Represented nude, each have one leg forward on the main panel and one back, going over onto the side panel. Moreover, each have one arm folded while the second is raised aloft, holding their end of the festoon. Their bodies are plump, with generous curves and full cheeks, emphasising the youthful appearance characteristic of putti. They, like the festoon, are sculpted in high relief, their bodies almost completely detached from the altar, lending the scene a certain vibrancy. Below them, four eagles are represented, wings outstretched, each feather individually sculpted. Other small birds sculpted in lower relief are pecking at fruit beneath the festoon, while two cockerels face each other above it. Finally, three lines of a Latin inscription adorn the higher part of the panel, declaring:

C(aio) Comisio Helpisto

V(ixit) a(nnos) IIII m(enses) III

Comisia C(ai) f(ilia) delicio suo

To Comisius Helpistus

Who lived 4 years and 3 months

Comisia, daughter of Caius, [had it built] for his “pleasure”.

The side panels of the altar are decorated with classic ritualistic elements. On one side is a patera, a shallow wine vase, and on the other, a ewer, both the items used for libations. They are framed by a laurel wreath, its long, narrow leaves punctuated with small, round fruits. As for the frst side, the wreaths are fastened to the top corners with delicate knots and held aloft by the putti. Ribbons again escape, while birds peck fruit in the lower parts of both sides. The back of the altar is decorated more sparsely. Again, the panel is adorned with a festoon made up of fruit with ribbons escaping, while putti and eagles with outstretched wings decorate the corners. Finally, the borders are decorated with heart and dart friezes (this type of motif is also known as Lesbian kymation), lending the whole piece an undeniable elegance.

Under the Roman Empire, funerary altars were commonly used, because they made it possible to commemorate the dead. Originally, the altars were votive, dedicated to deities and heroes, but, over the centuries, they were erected for the dead and placed in funerary complexes and private tombs. They were adorned with an inscription stating the name, function and age of the deceased upon their death and, sometimes, the name of the person who had it built in their honour, generally a family member

or freed slave. Our altar matches this description. These altars were thus placed in private places of worship where loved ones could bring oferings and carry out funeral rites.

the Augustan period. The profusion of fruits and plants symbolises abundance and prosperity after death, the eagles are symbols of Jupiter and the cockerels facing each other represent victory — all iconographic elements linked to Roman funerary art that adorn many altars currently conserved in various international museums (ill. 1-3).

They were frequently decorated, generally with a portrait of the deceased, fruit adorned festoons, various animals and objects recalling funerary rites such as the patera and ewer. This iconographic repertory was also freely inspired by the decoration used for sacrifcial altars, particularly those of