9 minute read

DIVE IN

We are experiencing a kind of collective trauma. How do we find our way through that? How do we heal? One of my favourite writers, Robin Wall Kimmerer, has written that if “we restore the land, we restore ourselves.” The same goes for water. If we restore the water, we restore ourselves; restore the ocean, restore ourselves. There is no quick fix and there are going to be many different ways to heal, but I do believe there is healing to be had in our connection to water.

As a surfer and marine social scientist, my life is lived in intimate relationship with the ocean, exploring the power of the ocean to help us reconnect with ourselves, each other and nature. In the crises we face, the loss of our emotional connection with the more-than-human world, especially the ocean in all its wonder and aliveness, is of deep concern. There is no part of the ocean that remains unaffected by the growing and interconnected pressures from climate change, biodiversity loss and further degradation caused by human activities and pollution. In turn, the impacts of the ocean (and marine environmental degradation) on human health are poorly considered. Not to mention the roll-back on progress made to tackle plastic pollution, with the huge environmental and public health risk posed by the millions of disposable plastic face masks entering our waterways and ocean every minute.

An interdisciplinary European collaboration called the Seas Oceans and Public Health In Europe (SOPHIE) Project, funded by Horizon 2020, has outlined the initial steps that a wide range of organisations could take to work together to protect the largest connected ecosystem on Earth. In a commentary paper published in the American Journal of Public Health, the researchers call for the current UN Ocean Decade to act as a meaningful catalyst for global change, reminding us that ocean health is intricately linked to human health.

The paper highlights 35 first steps for action by different groups and individuals, including individual citizens, healthcare workers, private organisations, researchers and policy-makers, presenting opportunities for new alliances and partnership building. Many of these actions emphasise the need to link knowledge with practice in a way that supports and promotes a culture of care. This is even more relevant in light of the global pandemic, highlighting just how catastrophic the consequences of our societal disconnect from our natural place in the Earth’s systems is and how essential the restoration of healthy, functioning natural ecosystems are for our survival.

These first steps emphasise how essential holistic collaboration is to make an impact. For example: large businesses can review their impact on ocean health, share best practice and support community initiatives; healthcare professionals could consider “blue prescriptions”, integrated with individual and community promotion activities; tourism operators can share research on the benefits of spending time by the coast on wellbeing and collect and share their customers’ experiences of these benefits; or individual citizens can take part in ocean-based citizen science or beach cleans and encourage school projects on sustainability.

The paper calls on planners, policy-makers and organisations to understand and share research into the links between ocean and human health and to integrate this knowledge into policy. It is commendable that Minister for Tourism Catherine Martin and Fáilte Ireland are finally investing funds into supporting the development of outdoor watersports, recognising the surge in year-round interest in these activities, especially since the pandemic began. The inclusion of the provision for wheelchair accessible facilities is especially welcome. Most of the emphasis is on physical infrastructure such as, “hot showers, changing and toilet facilities, storage, equipment wash-down and orientation points.” All are welcome facilities for the communities identified for funding, and although I agree with Minister Martin that Ireland is world-class when it comes to waterbased activities on offer along our “stunning coastline, rivers and lakes”, I couldn’t shake the feeling that this was an exercise in greenwashing.

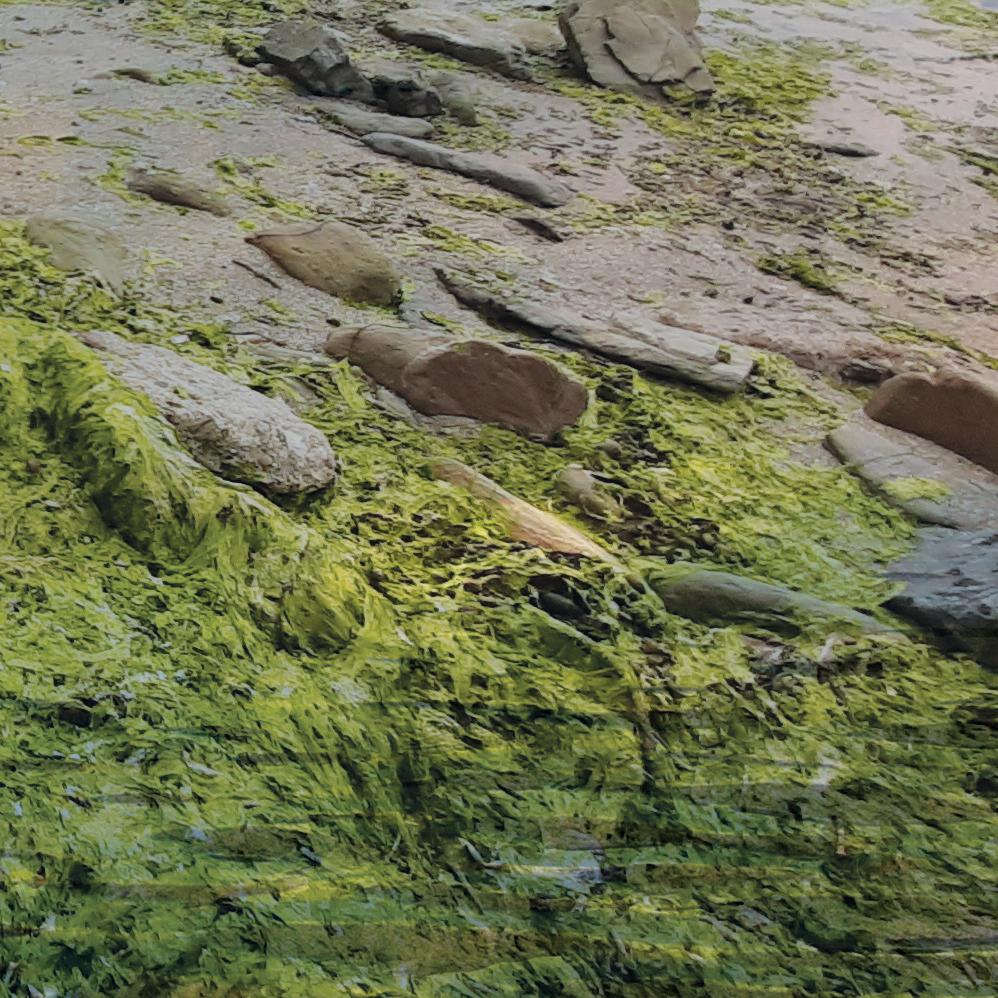

If we are to “ensure the Irish experience meets and exceeds visitor expectations”, would it not be an urgent priority to also ensure we are not swimming, bathing, paddling or surfing in our own waste? Ireland’s water environments are in crisis with water quality declining and water pollution rising at an unprecedented rate, primarily driven by the intensification of industrial agriculture, biodiversity and habitat loss and raw sewage from towns and cities. More than half of our rivers, lakes and estuaries are in an unhealthy state, failing to meet ecological targets set by the EU’s Water Framework Directive. Last year, there were 350 days when swimming was banned at bathing spots across Ireland. What value can ‘wild swimming’ have when ‘wild’ places don’t exist anymore? What healing benefit can ‘surf therapy’ offer when raw sewage is being pumped into the sea?

Image credit Victoria May Harrison Left to right: A West Cork beach fouled with algae; Galway Bay

With emerging community interest in local waterways and new river trusts, catchment and coastal groups being established and with this new-found interest from government, perhaps we could encourage policy makers, local authorities and businesses to adopt some of the steps supporting ocean and human health in our communities? Surfrider and various community groups across Europe are pushing for key changes to improve the legal framework in the EU and ensure greater protection of our bathing waters, such as the inclusion of all-yearround monitoring, extension of the monitored areas to include nautical recreational areas and improved public information. Given the growing uptake in citizen science initiatives since Covid-19 began, there is tremendous potential for widespread community engagement and a more participatory approach to managing and protecting our waterways, beaches, coasts and seas.

We can’t be well in a sick sea. There are profound health benefits to be realised from restoring ocean health and protecting healthy marine and coastal ecosystems and I don’t just mean from omega-3 fish oils and the incredible array of natural products from the sea, including medicines and green substitutes for plastics. Evidence shows that ‘blue spaces’ (outdoor bodies of water) are among the most restorative environments for humans. Recent studies show how healthy coasts are associated with lower risk of depression, anxiety and other mental health disorders, as well as greater relaxation in adults and improved behavioural development and social connection in children.

Water facilitates a full-bodied sense of connectedness with life. A recent national study on nature connection for health and wellbeing found sea swimming to be one of the most effective outdoor activities for significantly enhancing this sense of connectedness. This is linked to it being a highly immersive and multi-sensory stimulating activity — taking in all the movement, colour, sounds, sensations and textures through all of the senses.

Going into the water and inhabiting our bodies fully is about being able to cross a threshold and enter into your own world, sometimes being able to leave the worries of our land-life behind for even a moment. Lucy Jones, author of Losing Eden, describes immersing herself in water as “a portal to another world.” It’s a place where we can feel held by the water, where it is possible to express what we are feeling, to safely release whatever tension we’re holding, without judgement. Simply looking at the sea or listening to the sound of waves breaking has a measurable effect, calming our brain waves and soothing our frayed nervous systems.

With the huge influx of people taking to our waters and sea, there is a real need and opportunity for greater support for initiatives that promote ocean action, awareness and education. For those meeting the sea for the first time it can feel strange, unfamiliar, maybe even dangerous. Like any good relationship it takes time to understand the ocean, to develop the life-enhancing (and life-saving) skills to read the sea and to be safe. “It’s really important to educate people. It’s not just about your personal experience, it’s about the environment you’re in, knowing the tides, winds and geography of a place,” Caitriona Lynch, co-founder of Ebb and Flow Swimming in Galway, explains. “For me, what’s really important is helping people appreciate that it’s bigger than them and their experience. You’re a part of this amazing place and you protect it and mind it for yourself and other people.”

How might we restore our intimate relationship with water in our post-pandemic lives? How might it help us recover from the coronavirus by reconnecting us with what matters most? In healing the ocean, how might we heal ourselves?

‘Blue Health’, the potential benefits for health and wellbeing through connection to water and through these connections, engaging people in protection and conservation, is a ripe place for communities to be helping to ‘build back better’ following the societal upheaval caused by Covid-19. I believe the pandemic represents a unique opportunity to bring the ocean literacy principle of the interconnectedness between ocean and human health into mainstream culture, where the natural world isn’t some kind of frill but integral to our ability to survive and thrive. Where blue prescriptions such as ocean therapy, for example, are not a novelty, but offer a viable complimentary or alternative healthcare intervention when addressing the psychological distress of not only this pandemic, but climate breakdown and the complex challenges to come.

This will require cooperation and support on a global as well as local This will require cooperation and support on a global as well as local scale that we have now seen is possible. It will mean exploring ways that diverse perspectives recombine and accelerating awareness through shared experiences and storytelling of our intimate and emotional connection to the sea that give meaning and value to place – an ideal meeting place for science and arts. It will mean taking direct action in the form of citizen science and political engagement – making climate and the ocean a voting priority and, above all, fostering a culture of care for our ocean. For more information on actions you can take to improve your health and the health of the ocean, check out my new book: 50 Things To Do By The Sea..