ATHLETICS COACH AUGUST 2017 In this Edition • Strength Training for Sport • Establishing a Business Model for a Running Groups • Belief of Free Will and Performance • Why Every Coach Should Care About Sleep • Performance Progression of Javelin Athletes

T able of C on T en T s

2 ATHLETICS COACH - AUGUST 2017

3

Editorial

In late January this year we released a survey to see what topics you were interested in for future Professional Development sessions. The results were surprisingly diverse with strong interest in Strength and Conditioning, Nutrition, Injury Prevention, Sports Psychology and Financial Advice. I have tried to cover all these areas in this edition of Athletics Coach to give coaches a taste of the current research. I trust that we will be able to explore these topics further in lectures and online material in the future.

You will notice that most articles include links to peer reviewed publications (full texts where rights allow) to introduce coaches to trustworthy sources of knowledge to support their coaching practise. I understand the amount of time each coach can dedicate to their coaching varies and I hope by including these links it will allow coaches to explore each topic in the depth that best fits their time and interest in the area.

Finally, I wish to thank Mike Hurst who has offered his time as this edition's expert for 'Ask the Experts.' If you have a question for Mike, please send it in via email and a selection of the best questions will be published in our next edition.

Thank you for taking the time to read this edition and I hope it will introduce new ideas or reinforce your confidence in your existing coaching practises.

4 ATHLETICS COACH - AUGUST 2017

Blair Taylor

Thank you to all coaches who took the time during the Australian Athletics Championships to attend one of the many Professional Development sessions and a special thank you to the expert facilitators who contributed their time and knowledge.

5

6

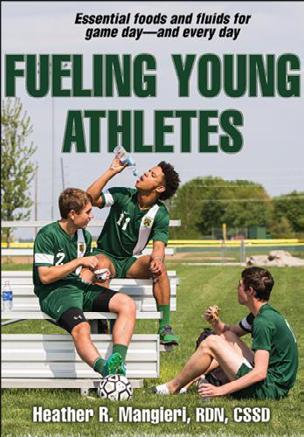

NEW RELEASE: FUELING YOUNG ATHLETES

In this edition we are once again delighted to offer all Accredited Coaches a special discount on a selected published coaching resource by Human Kinetics. In this edition, coaches are able to save 25% off 'Fueling Young Athletes' by award-winning food and nutrition expert Heather Mangieri. This text is a holistic

guide to all aspects of nutrition and hydration for junior athletes. It includes a thorough analysis of the importance of nutrition, nutrition and hydration plans, explanation of body composition, supplement information, recipes and 'game-day' advice. Suitable for any coach or parent working with developing athletes.

Click here for more information

Contents

Part I: Sport Nutrition for Today’s Athletes

- Building a Champion

- Day-to-Day Nutrition for Healthy Growth

Part II: Nutrition Needs for Sports and Individual Goals

- Fueling and Hydrating for Sport

- Adjusting Body Composition

- Fueling for Game Day

- Understanding Supplements

- Identifying and Dealing with Disordered Eating

Part III: Customize Your Sport Nutrition Plan

- Creating Your Personal Plan

- Breaking Down Barriers to Healthy Eating

Part IV: Recipes

- Liquid-Fuel Recipes

- Solid-Fuel Recipes

SAVE 25%: Join Human Kinetics Rewards for free and enter the promo code ‘ATHLETICS’ at the cart to receive 25% off books

7 HUMAN KINETICS

Establishing a Business for your Running Group

8

Business Model Group

Estimations on the number of runners in Australia vary depending on the criteria set by those gathering the data. When factoring in ‘active walkers’ the figure can balloon to as high as 8 million Australians engaging in running or walking activities, while it is believed that close to 2 million identify themselves as running at least once a week (Ausplay, 2016; Roy Morgan, 2016)

So what do these figures mean for coaches?

Well basically there is a market out there that has been underestimated and certainly under serviced by clubs and coaches alike. Obviously it is unreasonable to think that all of these runners are seeking out coaching as we well know the simplicity of running is one

of its key drawcards… a pair of shoes, some basic kit and the freedom of the roads or trails is all you need. But the market does exist, and so to the opportunity for running coaches to derive some level of income.

The new century has also seen a number of attitudinal changes that presents a changing dynamic for us coaches. These being the emergence of the user pays society and the acceptance that any coach with experience and education shouldn’t just do it for the love of the sport anymore.

Times are most definitely changing, so let’s take a look at some potential operating models and practical tips for establishing a business in coaching.

9

Establishing Your Business Model

We all know there are many ways to skin a cat and when looking around the country numerous models are emerging.

The Independent Coach

Operating as a sole trader there are already many coaches offering services as varied as kids running groups, one on one sessions through to online coaching. Generally registered as a business, these coaches provide all level of support which may include technique work, general conditioning, specific strength and agility and program writing.

Go Run’s Chris White has recently set up one such business, taking the leap into full time coaching and leaving the corporate world behind. Whilst a gamble for Chris, researching the demographics and particular needs of his local community has ensured a reasonably smooth transition into full time coaching. You are able to learn more about about Chris's story in the September 2016 edition of Athletics Coach (Building a Running Business)

The Personal Trainer

A common scenario we find with Personal Trainers is that their clients are entering running events and will look to their Trainer for support and guidance. Some will jump at the opportunity to help whilst for others it will move them out of their comfort zone. We then commonly find the latter group jumping on board the Recreational Running Coach Framework to give them the base knowledge to assist their clients. Once qualified, PTs can provide a great holistic service that includes both the endurance elements runners require together with the all important strength component. So whether working within a studio environment or outdoors, PTs are an ever increasing segment of the coaching market.

Figure 1: Growth of participation in jogging

(Source: Ray Morgan Resarch, 2016)

Online Coaching

The digital age and ‘never enough time’ in the number of runners seeking online communication channels, online coaching an emailed program and phone hook up to much more personal level of service while such as Strava provide more stats and Through an online program management there isn’t much a runner coached online coffee catch up!

Pat Carroll has been operating online sessions on the Gold Coast. Having his person to person coaching, Pat has great success.

32.5 16.7 8.7 1.8 48.5 35.6 22.2 6.1 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 14 - 24 25 - 34 35 - 49 50+ % WHO JOG OCCASSIONALLY OR REGULARLY AGE 2006 WOMEN

10 ATHLETICS COACH - AUGUST 2017

2016

between 2006 and 2016 by age and gender.

Health Studios/Fitness Centres

Diversity is good for any business and providing run groups is now seen as a great addition to other services offered by established studios and gyms. Once again, the provision of a full service is attractive to runners, or the prospect of a running race where other gym members may be involved can be the lure to attract people into running. Existing staff may or may not have the experience and skills to take run groups, so opportunities are certainly out there for qualified Recreational Running coaches to enter this environment.

Run Squads

Small, medium and large running squads are now a regular sight in our major population areas. The size of the squad will often dictate the number of coaches required and also the variety of services provided. Well organised squads provide a valuable service to runners through structured sessions, coaching guidance and program development.

Founded by Sean Williams, SWEAT Sydney is a great example of how a run squad has developed to service the needs of juniors, recreational runners and elites alike with Sean now branching out to form the Melbourne Pack.

society we live in has seen a boom assistance. With ever increasing now goes well beyond the old days of discuss. Skype and Facetime provide a online data recording from websites info than a coach will often require. via Training Peaks or Final Surge and misses out on, apart for the good old

services in parallel to his group established a great reputation through been able to extend reach online with

Run Squads

Similar to athletic clubs, recreational running clubs are generally run by committees with the coaches being central to the operation of any club. Each individual club will operate differently, some paying coaches for the sessions they conduct, others simply meeting the coach’s costs such as education, accreditation and uniforms.

A common theme amongst the recreational running clubs is developing coaching structures from within, often identifying potential new coaches and tapping them on the shoulder to start their own coaching journey. But that’s not to say that clubs aren’t also on the look out for experienced coaches to join them – particularly some of the newly formed groups who may lack coaches at the right level to provide a good hierarchical structure.

33.6 25.8 14.7 4.5 45.1 37.9 25.8 7.8 14 - 24 25 - 34 35 - 49 50+ AGE

MEN 11 ESTABLISHING A BUSINESS MODEL

12 ATHLETICS COACH - AUGUST 2017

Structuring the Training

There are also a variety of ways that coaches are able to deliver and monetise their services.

Yearly Membership

Applicable mainly within the club environment, a coach may have runners who sign up for a year and then get all services offered within that period. The service offerings may be scalable dependant on the fee paid – a full service may include all sessions, an individual program plus one on one time, while for a lower fee you may only get the sessions and only a generic program.

Monthly or quarterly payments

Common with PTs and gyms, this method doesn’t guarantee a long-lasting relationship but may be more cost effective for runners and lead to greater uptake than trying to lock people into longer term arrangements. Once again, these payments can be scalable based on what’s on offer and can provide the runner and coach a reasonable amount of flexibility.

The Campaign

This is an increasingly popular option for coaches across the industry. With the regularity of running races across Australia, tapping into one particular race and providing a range of services to prepare the runner is a strong model. A campaign fee can be charged, which from a runner’s perspective, means they are not locked in for a long term, with periods of 10 to 14 weeks being common for a campaign. For the coach, the advantage is that if well conducted you can almost guarantee when the runner embarks on a new campaign, generally over a longer distance, you know exactly where they’ll go for help!

13 ESTABLISHING A BUSINESS MODEL

Payment Considerations

Death and taxes are the two certainties in life, so be aware of your obligations in terms of structuring yourself, your business or your club.

When considering which of the business models you are likely to adopt, the best first stop for information or advice is the relevant government department in your state or territory. Look at what options are available then go about establishing yourself in the correct manner. It may be that you need an ABN, have to set up a business or incorporate a club.

Following on from this are the reporting requirements. If organising finances isn’t your forte perhaps consider getting an accountant or experienced financial advisor to make sure that this is all done correctly.

The physical act of collecting money also has many options. Getting cash via the coins in

the bucket system may work for you, but there are now many electronic payment options that simplify the process for both the runner and coach. Direct debit, direct deposits and Credit Card auto payments certainly make life simpler and are such common forms of payment that consumers rarely baulk from these options now. So consult with your bank or talk to other coaches who may have a payment collection system in place to see what best suits you. Electronic payment systems will attract fees, but the consensus is that it is money well spent when compared to cash handling or chasing people for debts.

There are a definitely a whole range of options available to coaches to establish themselves and become a legitimate business. As mentioned at the start of the article, there are plenty of runners out there and they are prepared to pay for a quality coaching service, so there is no reason to sell yourselves short.

Further Reading

Australian Taxation Office (2017). Starting your Own Business. Business.gov.au (2017). Register for an Australian Business Number (ABN).

Fitness Australia (2016). Profile of the Australian Fitness Industry 2016.

McCluskey, K. (2015). Fitness Australia & Current Industry Trends: Simplified Statistics, VFA Learning

Parrot, D. (1996). Whose Business is Fitness? Journal of Health Care Marketing, 16(3), 44-49.

14 ATHLETICS COACH - AUGUST 2017

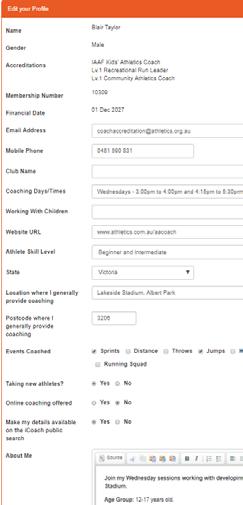

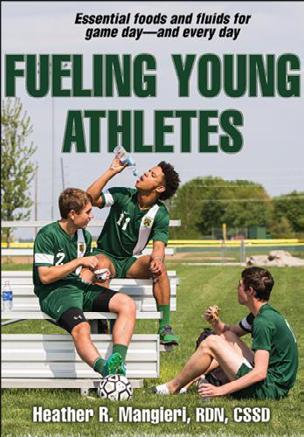

Setting Up Your iCoach Profile to Maximise Exposure

The new iCoach system is now up and running. It is important to ensure that your details have been updated to ensure that you are appearing in the searches where you want to appear.

Click here to login and update your details.

Enter your preferred contact details for new athletes/runners

Enter your availability

Enter your WWC Number

Enter your Website/Facebook etc.

Indicate the skill level of athletes that you wish to coach

Enter your training location(s)

Tick the event groups you coach

Click 'Yes' if you are accepting new athletes

Click 'Yes' if you offer online coaching

Write as little or as much as you'd like about yourself and your coaching services

15 ESTABLISHING A BUSINESS MODEL

IT’S NOT WHAT CHILDREN PLAY, BUT HOW THEY PLAY IT THAT MATTERS

Originally published by The Conversation

Sport is massive and it’s everywhere: on TV, in videogames, and on the streets. As a consequence, myths about the inherent greatness of sport have grown. One such myth is the belief that sport itself is ideally suited to help disadvantaged young people develop “socially” and “psychologically”. And that sport is capable of teaching “teamwork” or “leadership”.

It is frequent to hear phrases such as “rugby teaches discipline”, or “football teaches teamwork”. And what these sentences have in common is the assumption that there is an inherent, almost magical, quality in both rugby and football.

On the basis of this assumption, disadvantaged young people are encouraged to join youth sport programmes which use sport as an educational tool. The goal of these programmes – which are frequently run by charities – is to develop young people into “good citizens” by teaching them “life skills” – like teamwork or discipline.

Unfortunately though it isn’t quite that simple.

Ioannis Costas Batlle

Ioannis Costas Batlle

University of Bath

My research explores the extent to which youth sport programs can meet the needs of socioeconomically disadvantaged young people. I am particularly interested in youth sports programmes delivered by UK charities.

The Value of Sport

While hearing someone say “rugby teaches leadership” does not sound jarring, if one of your friends were to suggest that “finger painting teaches leadership”, you would stare at them in disbelief.

The source of this disbelief stems from what have become commonsense understandings about the value of sport. These understandings are that sport “naturally” teaches “leadership”, “teamwork”, or “critical thinking”.

In turn, these commonsense understandings have become deeply entrenched in the way society values sport. Though there is evidence that sport – when delivered appropriately – can help young people develop, the picture is more complex.

PhD Researcher

16 ATHLETICS COACH - AUGUST 2017

"Though there is evidence that sport – when delivered appropriately – can help young people develop, the picture is more complex."

For instance, one of the most popular perceptions about the value of team sports is that they teach “teamwork”. But what about when young players become frustrated at teammates for having inferior technical and tactical skills?

It may well be that not a great deal of teamwork is being learned when these proficient players make less skilled teammates feel inadequate and unwelcome because of their limited ability. And this is why we should be cautious about the assumed educational value of rugby (or any other sport) over any other activity – like finger painting.

17

I Respect You, You Respect Me

But despite all this, charities frequently document cases of young people developing life skills such as confidence and determination through sport. The voluntary sector are certainly not making these results up, so as part of my PhD research I wanted to explore this link between sport and young people’s development. I interviewed coaches and young people (aged 1215) at a youth sports charity as well as observing coaching sessions.

The young people I spoke to, highlighted their devotion for their coaches because they felt these adults cared about them as human beings. Coaches established a relationship summarised by a young girl as:

"It’s not you respect me. It’s an I respect you, you respect me thing."

It was clear that the young people also loved the activity they did. They loved playing a particular sport, alongside a particular coach. Young people also expressed why having a sense of belonging mattered to them. They liked the environment of their coaching sessions and felt welcomed in it. It was a space where they could participate in an activity they enjoyed, with people they liked, all while feeling part of something bigger.

18 ATHLETICS COACH - AUGUST 2017

The Hidden Variable

Through observing and talking to young people and their coaches, I found that while sport itself does not improve young people’s development, the “hidden” variables of passion, relationships and a sense of belonging, genuinely do. So when it comes to young people’s social and psychological development, the focus should not be on which sport to play, but on how sport is used.

If a youth sport programme focuses on unlocking young people’s passion, developing meaningful relationships and fostering a sense of belonging, these programmes can be extraordinarily powerful.

What this means is that sport can be a great educational tool, but so can many other interests or pursuits. And instilling passion, relationships, and a sense of belonging is something any activity – such as finger painting or stamp collecting – can achieve. As the saying goes “it’s not what you do, it’s the way that you do it”, and that couldn’t be more apparent.

More from The Conversation

Will there ever be a level playing field in visually impaired sport?

Exercise can be punishing - but here's how to stop thinking of it as punishment

Integrity in sport needs to grow from the grassroots level

19 IT’S NOT WHAT THEY PLAY

STRENGTH TRAINING FOR SPORT

Written by former Head Track and Field Coach at the Australian Institute of Sport Kelvin Giles

Kelvin Giles MA, CertEdA former UK National and Olympic Track & Field Coach, Kelvin spent 30 years in Australia’s high performance sport environment. He was Head T&F Coach at the Australian Institute of Sport in Canberra and Head of the Athletic Development department at the Queensland Academy of Sport in Brisbane. He spent 6 years at the helm of the Brisbane Broncos Rugby League team as Director of Performance and also led the Australian Rugby Union’s Elite Player Development section. He is a coach to 14 Olympic and World Championship athletes over a 40 year career. He is currently CEO of Movement Dynamics UK Ltd and currently consults across a range of National Governing Bodies and Federations and is the author of the Physical Competence Assessment resources.

"Getting weight-room strong is easy & very measurable. Applying that strength to sport is difficult & somewhat esoteric. That is why we need to take another look at whole approach to strength training."

Vern Gambetta – The GAIN network

This is a fascinating statement from Vern where he, again, raises the pertinent question about the role of strength training in sport. Finding an answer is the difficult part especially if you believe in the mantra that ‘there is never only one way of doing anything’.

Too often athletes enter into a strength training program that sees them getting generally strong by a variety of methods and then, at a later date – closer to competition, attempting to use this new-found strength in the actions and postures required by the sport. Let’s be frank – if you get generally stronger, fitter and more stable you will probably improve your sports performance. Even if all you do is the sports-specific stuff I am sure that some improvement in sports performance will show its face at some stage.

However, if your goal is to set a progressive, long term, ever-improving performance continuum that, hopefully, culminates in a major world championship or collectively in a full season of exemplary performance then the ‘general’ stuff on its own probably won’t be appropriate or sufficient.

20

Many athletes choose a theme of Olympic / Body-Building weightlifting type exercises as their main strength training tool. Often we see a progression of work-cycles from strength accumulation to strength maximisation and onto strength application. These cycles of work can be many weeks in duration which allow the body time to adapt to the load in question. These progressions are often sequenced in a linear manner where some periods are spent accumulating strength e.g. 3×5 > 4×5 > 5×5 > 6×5 at approximately 80% of 1RM. Weeks are then spent maximising the load e.g. 3×3 > 4×3 > 3×2 > 4×2 > 2211 at loads exceeding 90% of 1RM; athletes then attempt to weave this strength attainment into the sports-specific actions and postures as the competition phase approaches.

Often the exercises include Bench Press, Shoulder Presses, Machine Rowing; Squats; Cleans, Deadlifts, Snatches, Leg Presses, etc,

and they can appear to be a successful format i.e. athletes get ‘weight-room’ strong. Often these programs have other elements integrated such as Circuit Training, Plank work for stability and some type of ‘Pre-hab’ often generated by a physiotherapist under the heading of ‘injury-prevention’. All in all things look OK – athletes can get stronger in the exercises and they may even see injuries reduce a little.

They key question is that while an athlete ‘gets stronger in the exercises’ what is really happening with the sports-specific actions and postures that the final test is all about – the contest itself? This is the crux of the matter – how much of this all-round strength can the athlete apply across all the competition circumstances they will face? How strong is strong enough? Before looking at these questions it is pertinent to put things into perspective with regard to the journey the athlete is on.

21 STREGNTH TRAINING FOR SPORT

This brings to the fore the issue of the training-age of the athlete. I would suggest that the lower the training-age the more ‘general’ things will be. The higher the training-age the more specific one can be. This ‘training-age’ implication must be examined closely before decisions are made in haste. Training-age is not simply the number of years an athlete has been turning up at training. I describe training-age as the number of years of appropriate technical, tactical, physical and mental adaptation to appropriate prescription. In other words, the athlete must have a background of ‘earning the right’ to progress by accumulating effective and permanent adaptation to the many-sided aspects of appropriate training and competition.

In the early stages of the journey the exercise prescription should be an exposure to: Movements (every plane, direction, amplitude, speed and complexity); the full range of force experiences (general anatomical adaptation, general strength, maximal strength, power, RFD); a full range of metabolic challenges (alactic, lactic, aerobic); a full range of learning opportunities (implicit and explicit); a full range of ‘contest adaptation (personal tests, indirect competition, direct competition).

As the training years unfold so the prescription of training and competition begins to become more focused towards contest outcomes. In the early teenage years the athlete will also need to adapt to the ‘arenaskills’ and ‘life-skills’ associated with performance. Their ability to live the life of a performing athlete both outside the arena and within it must be experienced and progressed in the same way that the ‘hard’ skills of technical and physical training have been developed.

ATHLETICS COACH - AUGUST 2017

"Don't worry about training like the pros until you are one."

- Steve Myrland, 2009

23 STRENGTH TRAINING FOR SPORT

My colleague Steve Myrland illustrates the difference between the journey of the developing athlete and that of the seasoned athletes through the Youth Development Model, Continuing Model and Professional Model.

If the journey is assembled as mentioned, whereby the athlete has an all-round grounding in a wide and deep set of physical experiences, then the program can start to shift towards the required outcomes of performance enhancement. Strength training prescription, for example, may well begin to resemble movements that are closer to those experienced in the contest and the use of ‘complex’ training might be considered.

The previously mentioned linear progression of repetitions and sets is not appropriate to the

athlete not involved in Olympic Weightlifting or Powerlifting sports. There is far too long a gap between the strength stimulus (accumulation, maximisation) and the actual sports-specific actions, postures, force requirements, etc. As the journey narrows to performance enhancement and a rigorous competition cycle so the training should not venture too far from the sports-specific movement, actions, postures and force requirements. The role of ‘complex’ training can be effective at this time by linking the general movements, and all the forces experienced, to the sports specific movements.

Complex training in this instance is where the session exposes the athlete to a variety of stimuli from the force continuum and at the same time exposes them to movements that span from general to specific.

Youth Development Model (AGE 5-16 YEARS)

Competition

Specific

General Special

H"Learning to move; moving to learn"

- Steve Myrland, 2009

ere the developing athlete spends a large amount of time in ‘general’ work and less amounts of time in ‘special’, ‘specific’ and ‘competition’. All-round the picture is one of fun and experimentation.

24 ATHLETICS COACH - AUGUST 2017

H

Continuing Model (AGE 17-21 YEARS)

"Training to train (better, harder, longer); learning to compete"

- Steve Myrland, 2009

Competition

ere the athlete still uses general work as the cornerstone of their program. They also use competition, special and specific work as part of the plan to methodically hone their competitive cutting edge for when it really matters – at senior level.F

inally the athlete arrives at the part of their career when the outcome of the contest is the sole measurement. They use the ‘general’ periods as a time to renew and review the foundations of their training.Professional Model (AGE 22+ YEARS) Competition General Specific

"Training to survive, thrive and win"

- Steve Myrland, 2009

25 STRENGTH TRAINING FOR SPORT

General Special Specific

Special

Example from a Triple Jumper I Coached

This is for a senior athlete with a training age of 10 years. This example shows the period of about 8 weeks out from the start of competition season.

“There are many roads to Rome when trying to get the strength gains to work with the sport”

Session 1

Session 2

26 ATHLETICS COACH - AUGUST 2017 Exercise Set 1 Set 2 Set 3 Set 4 Double Leg Squat X6 @ 80% 1RM X5 @ 85% 1RM X4 @ 85-87% 1RM X4 @ 85-87% 1RM Barbell Jump Split Squat (BMS) 3 Each Leg @40% 1RM 3 Each Leg @30% 1RM 3 Each Leg @25% 1RM 3 Each Leg @25% 1RM Single Leg Hurdle Hops 4 Each Leg @100cm 4 Each Leg @100cm 4 Each Leg @100cm 4 Each Leg @100cm

Exercise Set 1 Set 2 Set 3 Set 4 Double Leg DB Snatch to Squat X4 Each Leg @80% 1RM X5 @ 85% 1RM X4 @ 85-87% 1RM X4 @ 85-87% 1RM Single Leg Clean (BMS) 3 Each Leg @40% 1RM 3 Each Leg @30% 1RM 3 Each Leg @25% 1RM 3 Each Leg @25% 1RM Single Leg Hurdle Hops 4 Each Leg @100cm 4 Each Leg @100cm 4 Each Leg @100cm 4 Each Leg @100cm

Exercise Set 1 Set 2 Set 3 Barbell Jump Split Squat 3 Each Leg @40% 1RM 3 Each Leg @30% 1RM 3 Each Leg @25% 1RM Single Leg Hurdle Hops 4 Each Leg @100cm 4 Each Leg @100cm 4 Each Leg @100cm Bounding 2H2St2H2St 6St HSJ X 2

Session 3

The Rationale

Three sessions per week under the ‘Strength’ banner.

Session 1 & 2 sees each set move from strength accumulation (Exercise 1 – heavy load) to a more ‘elastic’ power exercise (Exercise 2 – an ever decreasing ‘fast-strength component) to a bodyweight exercise with high RFR/D expectations (Exercise 3). There was about 2 minutes rest between exercises and 5 to 6 minutes between sets.

Hopefully this allowed the athlete to explore a variety of force levels within the same set and to finish with a movement (Single Leg Hurdle Hops) that was close to the movement / force pattern of the event.

With fatigue setting in as the week progressed the final session saw a reduction in volume (4 to 3 sets) and a major increase in rest between exercises and sets. The heavy load exercise was eliminated and the last exercise moved even closer to the movements and forces of the event – e.g.

Set 1 – 2 Hops into 2 steps into 2 Hops into 2 steps against the tape measure (8 landings)

Set 2 – 6 steps against the tape measure (6 landings).

I am hoping that this example gives just one idea of how to apply strength from the weight-room to the sport. Without knowing what scientific research said about all this I tried to get the body and brain to transfer gains created in the ‘general’ exercise – Double Leg Squat and Double Leg DB Snatch to Squat – all the way to the exercise that was closest to mimicking the actual event – Hurdle Hops and Bounding all within a short period of time in the session. Each of the chosen components had their own horizontal journey (increasing load, intensity, etc) over time while, at the same time, being linked vertically with the next exercise.

It was designed by me AND the athlete based upon previous history, current status, what had gone before, and what was yet to come. It certainly is open to much criticism from strength coaches better than I and is not being presented as something for anyone to follow with their athlete. It is an attempt to show that there are many roads to Rome when trying to get the strength gains to work with the sport.

Further S&C Reading

Moura, N. & Moura, T. (2001). Training Principles for Jumpers. Implications for Special Strength Development, New Studies in Athletics, 10, 51-61.

Painter, K., Haff, G., Ramsey, M., McBride, J. & Triplett, T. (2012).Strength Gains: Block Versus Daily Undulating Periodization Weight Training Among Track and Field Athletes, International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 7, 161-169.

27 STRENGTH TRAINING FOR SPORT

28 ATHLETICS COACH - AUGUST 2017 WORLD COACHES CONFERENCE LONDON Quayside Room, Hilton Hotel Canary Wharf CLICK TO VIEW THE BROCHURE

WORLD COACHES CONFERENCE

LONDON 2017

The IAAF will be holding the 3rd World Coaches Conference in London from the 7th to 10th of August. The sessions will be run in the mornings from 8:30am and 12:00pm while there are no competition events scheduled.

Coaches who are in London for the World Championships are able to register for each day of the conference by signing in at the Conference Hall from 8:30am.

9:30am Physiological and metabolic background of endurance training. Practical consequences for science based endurance training

7/8 10:45am Coaching Long Distance & Marathon World Class Athletes. Best practice of endurance training (Q&A)

8/8 9:30am Physiological and metabolic background of strength training. Practical consequences for science based strength training

8/8 10:45am Coaching World Class Athletes. Best practice of strength training

9/8 9:30am Physiological and metabolic background of speed training. Practical consequences for science based speed training

9/8 10:45am Coaching World Class Athletes. Best practice of speed training.

10/8 9:30am The brain as a performance limiting factor. Practical consequences for science based training.

10/8 10:45am Coaching World Class Athletes. Best practice of training.

10/8 12:00pm Closing Ceremony

Coe

Prof. Dr. Ullrich Hartmann

Victor Lopez & Gunter Lange

Shaun Pickering

Victor Lopez & Gunter Lange

Loren Seagrave

Victor Lopez & Gunter Lange

Neil Dallaway

Victor Lopez & Gunter Lange

29 WORLD COACHES CONFERENCE

Date Time Session Moderator 7/8 9:00am

Sebastian

Opening Ceremony

7/8

TAX MATTERS FOR COACHES, TEACHERS

AND PERSONAL TRAINERS

The start of a new financial year means it is time to complete your tax return yet again. For eligible coaches, teachers and other fitness professionals there are a number of opportunities to deduct expenses related to your athletics coaching. The best way to ensure that you are getting everything that you are entitled to is to speak to your accountant or a tax professional. To help you get started this article will take a look at who is eligible to apply for a deduction and the kind of expenses that you are able to include.

One of the key factors that will determine your ability to claim tax deductions for athletics coaching related expenses will be whether your coaching is done as a professional or as a hobby. If athletics coaching is part of your employment with an organisation that pays you a wage (e.g. school teachers, Sporting Schools coaches) you will most likely be eligible. For sole traders the distinction is a little more difficult. The Australian Taxation Office offers a guide to help you make the distinction between a hobby and a business for taxation purposes. If you are running a business you can claim for deductions on your business-related expenses.

30

31

Who is eligible to claim a tax deduction for Athletics coaching related expenses?

- An employee of an organisation who conducts athletics coaching as a part of their employment. The employee can be employed on a full time, part time or a casual basis.

Examples may include:

• A Primary School teacher who teaches athletics during a PE class.

• A Sporting Schools coach who has delivered a program as an employee of Athletics Australia during the financial year.

• A fitness professional employed by a gym who includes a running group as part of their professional services.

• A professional athletics coach employed by a club to deliver coaching sessions to club members.

• A university student employed on a casual basis to deliver athletics sessions at a local Primary school.

• A teacher who maintains their accreditation to be able to teach the Fosbury Flop to their students.

- A self-employed athletics coach or fitness professional who is coaching as part of their professional activity. To find out whether you are eligible to apply for tax deductions as a self-employed coach, take this short test on the business.gov.au website.

Examples may include:

• A professional coach running their own business and earning more than $25,000 in a financial year.

• A self-employed Personal Trainer renting a gym, who includes running training as part of their services.

• A running coach who employs staff members to assist their business operation.

- Individuals who coach only as a hobby are not eligible to claim tax deductions on athletics coaching related expenses. It is important to note that a hobby-coach is still able to charge for the cost of their work and doesn't have the reporting obligations of professional coaches. If you are unsure whether your coaching is considered a business or a hobby, see your financial advisor.

When claiming travel expenses, it is important to have a form of evidence supporting the reason for your travel. For example, keep a receipt of registration for PD sessions - even if it was a free session.

32 ATHLETICS COACH - AUGUST 2017

If eligible, what are some of things you might be able to claim on your tax deduction?

Car Expenses

The Australian Tax Office advises that you can claim deductions for your car expenses for travel from home to work if you carry bulky items that you are required to use and there is no secure area provided to leave them on the site. For example, professional coaches carrying heavy equipment such as Pole Vault poles to locations where there is no storage available should speak to their financial advisor about deducting car expenses for this trip.

Coaches can also claim deductions for car expenses when travelling directly from one work site to the next. For example, a Sporting Schools coach travelling directly from one school to another should keep a record of their travel for tax purposes.

For further information about what expenses you can claim as car expenses click here

Travel

Travel to work-related conferences, seminars and events can be deducted, provided it is sufficiently relevant to your professional activities. For example, a professional coach travelling to Sydney to manage their athlete at the Australian Athletics Championships may be eligible for deductions. Similarly, a Teacher coaching athletics as part of their role may be eligible to deduct expenses related to attending a coaching seminar to further their education.

Equipment

You can claim an immediate deduction for equipment that you use for your coaching for equipment cheaper than $300. For equipment above $300 you are able to claim a deduction for the decline in value of the product. The Australian Tax Office offers a guide to depreciating assets for equipment such as weights, blocks etc.

Clothing

Coaches who work outdoors are eligible to claim deductions for sun-protective items including sunscreen, sunglasses, hats or other protective headwear.

General fitness clothing cannot be deducted but if you are required to wear a uniform for your professional activities you can claim the cost of the clothing and the cost of laundering your uniform and protective clothing.

Coaching Accreditation Fees

You can claim deductions for subscriptions to trade, business or professional associations. Email Blair Taylor if you require a copy of your receipt for your reaccreditation payment from the 2016-17 financial year.

The advice provided is general advice only. It has been prepared without taking into account your objectives, financial situation or needs.

33 TAX MATTERS

HYDRATION ESSENTIALS

“Fluid intake and hydration… are critical and not to be taken lightly. There is no cheaper, simpler, or more effective way to help performance and protect health than staying hydrated during exercise.”

- Heather R. Mangieri

Hydration is critical for maintaining blood volume, body temperature and muscle function. Dehydration impairs athletic performance by increasing fatigue, heart rate and decreasing mental performance.

Suggested Reading

Costa, R., Teixeira, A., Rama, L., Swancott, A., Hardy, L., Lee, B., Camoes-Costa, V., Gill, S., Waterman, J., Freeth, E., Barrett, E., Hankey, J., Marczak, S., Valero-Burgos, E., Scheer, V., Murray, A. & Thake, C. (2013). Water and Sodium Intake Habits and Status of Ultra-Endurance Runners During a Multi-Stage UltraMarathon Conduted in a Hot Ambient Environment: An Observational Field Based Study, 12:13.

Daniels, M. & Popkin, B. (2010). Impact of Water Intake on Energy Intake and Weight Status: A Systematic Review, Nutrition Reviews, 68(9), 505-521.

How much water is the right amount that runners and athletes should be consuming? "Ahh...this is a question I always have difficulty answering" says dietician Joan Chua. "On one hand, when people exercise they can lose considerable amounts of fluid through sweating that must be replaced, at least partially, to

prevent dehydration. But on the other hand, overhydration of athletes is surprisingly common, especially for novices and can have very serious consequences for their health. So athletes need to get the balance right and there's no way of really knowing what that balance is without spending time with them to work out a personalised

Ukrainian 20KM Race Walker Nadiya Borovska at the 2016 Olympic Games (Photo by Bryn Lennon/Getty Images)

34 ATHLETICS COACH - AUGUST 2017

hydration plan."

The key information Chua wants to understand when working with a new athlete to design a personalised hydration plan is how heavily they sweat during exercise, their fitness level and their usual hydration habits. "Most people that come to me are already very conscious about how much they are drinking, so when they begin exercise they can afford to lose a bit of fluid without it having any effect on their performance. For these people I think it's more important that we focus on rehydrating after exercise to help recovery. I set up a plan with the athletes to ensure that they return to their pre-race weight within the next few hours - a hydration plan that fits in with their life."

Being based in Singapore, Chua is well aware of the effect the environment can have in influencing fluid loss. "For Singaporeans we are used to the humidity, but last year we had lots of people come from China and Europe [for the Singapore Marathon] who suffered from dehydration because they sweat much more than they usually do. My advice for

coaches is to consider the conditions that your athlete is going to be competing in and if you know it is going to be more humid or hotter than their training environment, plan for more regular fluid intake, especially in the second half of the race."

What does a hydration schedule look like?

Time Fluid Intake

Early morning Fill your water bottle as soon as you wake up

During the day Aim to consume 200mL every hour

2-3 hours before exercise

Prior to exercise

During exercise

After exercise

Aim to consume an extra cup of water during this time

Check your weight

Drink 500ml to 1 litre for every hour of exercise

Re-check your weight

- increase intake if required

Consider environmental factors that will effect your athlete on race-day and adjust the hydration plan as required - especially for events longer than one hour.

(Photo from the Gold Coast Marathon 2017 by Jason O'Brien/ Getty Images)

Consider environmental factors that will effect your athlete on race-day and adjust the hydration plan as required - especially for events longer than one hour.

(Photo from the Gold Coast Marathon 2017 by Jason O'Brien/ Getty Images)

35 HYDRATION

Adapted from Mangieri, 2017

W HAT THE EXPERTS ARE SAYING

“If used properly, sport drinks can be very beneficial”

Heather R. Mangieri, 2017

“Sports drinks should be trialled during training rather than competition”

Sports Dietitians Australia, 2017

“Caffeine and other stimulant substances contained in energy drinks have no place in the diet of children and adolescents.”

Schneider & Benjamin, 2011

“There is evidence to suggest that consuming a sports drink will improve performance compared with consuming a placebo beverage”

Coombes & Hamilton, 2012

ATHLETICS COACH - AUGUST 2017

SPORTS DRINKS

A necessary component for the proper hydration of your runners or a cleverly marketed bottle of sugary water? This article explores the science behind modern sports drinks and the role they serve for the modern athlete.

You've probably heard of the role sports drinks play in replenishing electrolytes - but what exactly does this mean?

Electrolytes refer to a chemical substance that produce an electrically conducting solution when dissolved in water. The reason they are so important for the human body is that many of our key functions such as the regulation of our heartbeat, blood pressure, cellular hydration, muscle contraction and tissue regeneration are reliant on the electrolytes in our bodily fluids to occur. For example, it is the electrolytes in our body that carry the electrical signals across a cell and into neighbouring cells to promote muscle contractions and nerve impulses.

When it comes to exercise, loss of sodium ions through sweating is considered the biggest challenge that runners and athletes face. Sodium is required for muscle contractions, nerve signalling and plays a role in maintaining a healthy fluid balance across our cells. An athlete suffering from a lack of sodium may notice muscle weakness, cramping, numbness, decreased awareness and in severe cases blood pressure changes, heart problems and seizures. Coaches need to be aware of these symptoms and adjust the intensity, duration or end the training session early

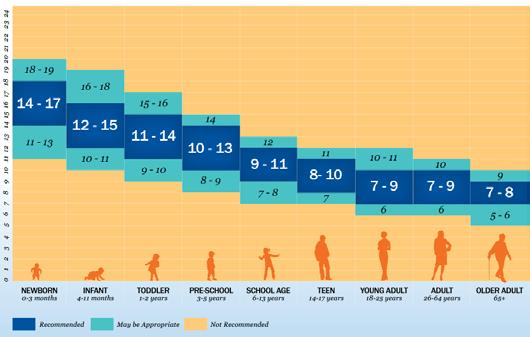

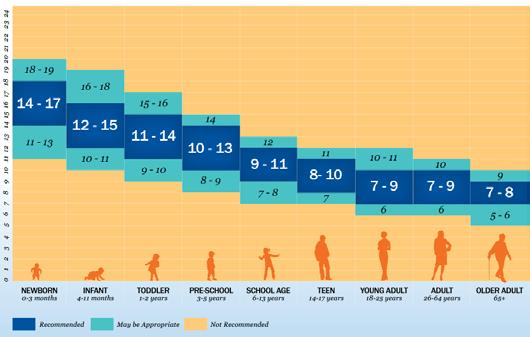

to prevent symptoms from worsening. Water alone will not replenish electrolytes and sports drinks are considered by the American College of Sports Medicine as a viable method of rectifying electrolyte deficit post-exercise. Evidence suggests that low carbohydrate concentration sports drinks are also effective at improving athletic performance (Coombes & Hamilton, 2012). However, when coaching young athletes it is important to consider whether or not it is beneficial to the individual based on their personal circumstances. Sports nutritionist Mangieri (2017) has no issue with young athletes drinking sports drinks when used appropriately. As a general guideline, Mangieri advises that when exercising for over an hour, a young athlete may benefit from drinking more than water alone. Sports drinks may also be appropriate for athletes that sweat heavily or when exercising in warmer conditions.

There is some opposition to the use of energy drinks from the scientific community that coaches should consider. The first argument against the use of sports drinks comes from a clinical report examining their appropriateness for children and adolescents by the Committee on Nutrition and the Council of Sports Medicine

37 HYDRATION

and Fitness (2011). They argue that for the average adolescent, sports drinks contain excessive carbohydrates that may lead to an increased risk of obesity. The report also warns against many sports drinks that contain caffeine or guarana as high doses of these stimulants can negatively affect developing neurological and cardiovascular systems. There is also the risk of addiction, leading to a reliance on these stimulants for the individual’s normal functioning. Finally, it is argued that the average adolescent’s electrolyte requirements are met sufficiently by a healthy balanced diet and therefore sports drinks offer little or no advantage over plain water. However, it should be noted that the authors explicitly state that young athletes who participate regularly in endurance or high-intensity sports are beyond the scope of the report and may have

additional electrolyte and energy demands that the average adolescent does not have. Coaches should also be aware of the effect sports drinks may have on their athlete’s dental health. Laboratory experiments have demonstrated the potential for acidic drinks, such as most popular sports drinks, to erode enamel and lead to a general deterioration of dental health (Rees, Loyn & McAndrew, 2005). However, studies conducted amongst the population of competitive athletes have shown no significant difference in dental health between sports drinks consumers and a control group (Milosevic, Kelly & McLean, 1997). Nevertheless, the study does warn that the erosive potential of acidic drinks is real and that additional consideration must be given of the effects over a longer period, especially for younger athletes.

What should you do if you suspect your athlete has an electrolyte imbalance?

The first step is to refer your athlete to their primary care practitioner. The most common correction for an electrolyte imbalance will be a change to the athlete's diet and hydration. In severe cases a practioner may recommend supplements.

38 ATHLETICS COACH - AUGUST 2017

39

COACHES MUST BE AWARE OF EXERCISE-ASSOCIATED

HYPONATREMIA

Exercise-associated hyponatremia is beleived to affect approximately 15% of runners and triathletes at major competitions and in severe cases has been the cause of several fatalities. All coaches, especially those working with distance athletes, must be aware of the warning signs.

What is it?

Athletes who drink excessive amounts of fluids during prolonged exercise - particularly novice marathon runners - can develop dangerously low sodium levels, called Exercise-Associated Hyponatremia (EAH)" (Hew-Butler et al., 2015). EAH occurs when excessive fluid dilutes the body's sodium level resulting in the inability to perform normal regulatory processes.

Gold Coast Marathon 2017 (Photo by Jason O'Brien/Stringer)

" 40 ATHLETICS COACH - AUGUST 2017

Key Resource

Rosner, M. & Kirven, J. (2007). Exercise-Associated Hyponatremia, Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology, 2, 151-161.

What should the coach be looking out for?

It is critical that coaches understand the causes and are able to recognise when their runners may be experiencing EAH. Although mild cases of EAH may have no symptoms, when more severe it can lead to bloating, nausea, headaches and puffiness in the face. If not treated promptly EAH can result in breathing difficulties, seizures or even death due to the swelling of the brain.

An effective tool for coaches is to monitor the weight of their runners before and after a run. One of the signs of a runner suffering from EAH is the increase in body weight over the duration of their exercise. Coaches are able to record pre and post-exercise weights of their runners during training to ensure that they are in the habit of consuming a healthy amount of liquid and avoiding overhydration. If you notice that your runners are gaining weight during a session, ensure that they are educated of the risks of EAH and encourage them to consume less fluids during exercise.

In

in warmer conditions

races

runners are at risk of overhydrating prior to the race in anticipation of heavy sweating. Coaches are advised to monitor fluid intake closely and avoid the assumption that EAH will not affect runners in a humid environment. (Photo: Rio Marathon by Ivo Gonzalez/Stringer)

41 HYDRATION

Who is at risk?

Everyone has the potential to suffer from EAH and it is believed to affect as many as 2% to 7% of participants of an average open-entry marathon. (Rosner, 2015). Female runners with a low body mass index are especially at risk. Novice marathon runners slower than four hours have been shown to have a higher likelihood of suffering from EAH than experienced runners.

Environment also plays a signifcant role in increasing the risk factor. Races held in extreme hot conditions increase the chances of athletes developing EAH, believed to be caused by pre-race overhydration in anticipation of sweating during the race.

“Prevention is based on widespread education regarding the risks of overhydration and judicious intake of fluids during endurance events”

Rosner, 2015

What do you do if your runner shows symptoms of EAH?

If you suspect your runner is suffering from EAH seek immediate medical treatment. In most cases, close monitoring and fluid restriction is enough for recovery, but severe cases can quickly result in mortality without the appropriate treatment. Doctors may prescribe a hypertonic saline to recover sodium levels in the affected runner.

How do you prevent EAH?

By reading this article you are already in a great position to prevent EAH affecting your runners. Awareness of the dangers of consuming too much water is one of the most effective preventions. Educate your runners of the potential risks and encourage them to avoid overhydration, especially pre-race overhydration.

Most races will ensure that hydration stations are adequately spaced out to help prevent EAH but if not, plan with your runners in advance where they should be taking fluids on the route.

Ultramarathon runners are at high risk of EAH.

(Photo of Australian David Byrne by Hagen Hopkins/Getty Images)

Ultramarathon runners are at high risk of EAH.

(Photo of Australian David Byrne by Hagen Hopkins/Getty Images)

42 ATHLETICS COACH - AUGUST 2017

Novice runners, especially females with a low body mass index are especially at risk

Rosner, 2015; Wagner & Knechtle, 2011

The Debate: When Should you Drink?

At the current time there is no consensus between peak bodies for the best practice regarding how much is the right amount to drink. The Third International Exercise-Associatted Hyponatremia Consensus Development Conference (2015) stated that "thirst should provide adequate stimulus for preventing excess dehydration." This contradicts the position of the American College of Sports Medicine (1996) who stated that individuals should "start drinking early and at regular intervals...consume the maximal amount that can be tolerated."

Coaches are encouraged to assess the evidence for themselves and regardless of which side of the argument you agree with, ensure that you are fully aware of the symptoms of EAH to protect the health and well-being of your runners.

43 HYDRATION

44

Trail Running and Ultra Marathon Coaching Module

The global growth in participation of trail and ultramarathon running is continuing. Event diversity and increased availability is providing new opportunities for runners wanting to experience a different challenge from road running events.

Trail running provides new excitement and physical challenges for runners keen to explore new horizons. Increasing distances to ultra-level and multi-stage events provides a diverse level of challenge and risk that coaches and athletes must factor into their training programs. To cater for this and ensure that coaches are prepared to handle the additional challenges trail and ultra-marathon runners face, we are in the process of releasing a new course tailored for coaches working in this space.

Topics include:

• Specific Training and Race Preparation

• Injury Prevention and Management

• Nutrition for Ultra-Marathon Runners

• Recovery

• Equipment

• Race Selection and Race Strategy

At the completion of the Trail and Ultra Runnning modules it is expected that coaches will be able to satisfy the following criteria:

• 1-ARR-TUR-1 Provide a training environment that is safe, inclusive and effective for the specificity of trail and ultra-athletes.

• 1-ARR-TUR-2 Demonstrate a thorough understanding of the specific demands and risks of these events.

• 1-ARR-TUR-3 Plan an effective training program that is multi-faceted in its approach.

• 1-ARR-TUR-4 Recognise the basic factors associated with athlete management and well-being.

45

PEAK PERFORMANCE JAVELIN

In the April 2017 edition of Athletics Coach we looked at the elite male sprinters from the 2016 Olympic Games and examined at what age they achieve their best performances over their career. This edition, we will look at the performance progression of Javelin throwers at National level and at what age elite female and male athletes hit their peak performance.

The age of peak performance was significantly higher for the throws than other track and field events studied

- Hollings, Hopkins & Hume (2014)

ATHLETICS COACH

(Photo by Mark

Heptathlete Alysha Burnett at the 2017 Australian Athletics Championships

Metcalf/Getty Images)

Key Facts

41.52m

The difference between the winning male throws of the U18 and U14 athletes at the 2017 Australian Athletics Championships.

25 years and 6 months

The mean and median age of male Javelin Olympic Champions since 1980.

26 years and 6 months

The mean and median age of female Javelin Olympic Champions since 1980.

19 years and 4 months

The youngest age of a male Javelin Olympic Champion

21 years and 2 months

The youngest age of a female Javelin Olympic Champion

34 years and 11 months

The oldest finalist at the 2016 Olympic Games.

The Australian Athletics Championships were a fantastic opportunity to observe the performance progression of athletes. Figure 1 shows the mean distance thrown of the top 5 athletes for each age group from the 2017 Australian Athletics Championships javelin finals.

Men Women

48 ATHLETICS COACH - AUGUST 2017

Statistics from Athletics Australia 79.23 67.29 54.07 48.77 43.44 32.86 55.13 49.98 43.77 40.41 41.93 34.83 OPEN UNDER 18 UNDER 17 UNDER 16 UNDER 15 UNDER 14 DISTANCE (M)

GROUP

AGE

Age Group Winning Distance (Women) Winning Distance (Men) Open 61.40m 84.36m Under 18 53.67m 77.57m Under 17 46.87m 56.59m Under 16 43.08m 50.37m Under 15 46.26m 46.37m Under 14 38.35m 36.05m

Figure 1: The mean furthest distance thrown of the top-5 Javelin athletes from the 2017 Australian Athletics Championships

Table 1: The winning throw from the Javelin at the 2017 Australian Athletics Championships

PERFORMANCE PROGRESSION OF JUNIOR THROWERS

The results from the Australian Athletics Championships show the progression of the nation's best Javelin throwers. The most interesting thing to note is that at Under 14 and Under 15 levels there is not a large difference between the best performing male and female athletes, but by Under 18 the mean result of male athletes was over 34% greater than the females. These results demonstrate

For coaches, this data highlights the importance of developing the fundamental movement patterns of throwing during an athlete's formative years. By establishing the basic technique while they are young, athletes will be much better placed to take advantage of their rapid physical development in their mid and late-teens (Lehmann, 2010; Sayers & Ingberg, 2009).

Coaches of female javelin throwers should also note the comparative lack of development observed during this period, especially between the Under 15 and Under 17 age group. This may be a frustrating period for female athletes in a mixed training group as boys they had previously out-performed begin to develop. Coaches should work with their athletes to set realistic expectations and goals to help them through this period.

Accredited Athletics Coach and F40 athlete

Kobie Donovan has kindly shared her career Javelin progression since commencing the event as a junior in 2009. As a later starter to the event, Kobie showed significant improvement between 2009 and early 2011 before remaining relatively consistent until the end of 2012. She then improved again significantly with Brett Green, culminating in her PB and World Record in 2015 at 20 years of age.

the rapid improvement of male athletes during this period driven by phsiological changes. This corresponds with existing literature which describes the onset of male puberty and the hormonal changes that occur around 14-17 years of age that promote muscle development (Lee, Guo & Kulin, 2001; Seger & Thorstensson, 2000) highlighting the importance of strength and speed for achieving success in the event.

49 PEAK PERFORMANCE

Accredited Coach Kobie Donovan at the 2017 Australian Athletics Championships (Photo by Mark Metcalfe/Getty Images)

Age Best Throw 15 9.12m 16 14.23m 17 16.43m 18 16.41m 19 19.39m 20 20.40m

Table 2: Kobie Donovan's Javelin progression

PERFORMANCE PROGRESSION OF ELITE THROWERS

Understanding the career progression of elite Javelin athletes assists coaches to design appropriate and successful longterm athlete development programs that gets your athletes performing at the right time.

Figure 2 shows the career progression of season best performances of the top 8 female Javelin throwers from the 2016 Olympic Games. The data shows a steady improvement of personal best throws up until 25 years of age for all athletes surveyed.

Of the six female athletes older than 25, all six achieved their Personal Best throws after turning 25. Four athletes had their best performance between 25-26 years of age, while Sunette Vilijoen and Kathryn Mitchell achieved their best throws at 29 and 34 respectively. These results mostly support the findings of Hollings, Hopkins & Hume (2014) that found the average female throwers peak in their late 20s between the age of 25 and 32, but also show improvement is possible well into an athlete's mid thirties.

The career progression of the top 8 men from the 2016 Olympics (Figure 3) are very similar to the women. Men show a consistent progression up until the age of 25, with some men continuing to improve up until their early 30s.

The results suggest that among the 16 athletes studied, improvement in an athlete's personal best between the ages of 20 and 26 is an essential factor for determining the success of the athlete.

While it is important to remember that this study only looks at a small group of elite athletes, it does highlight the importance of the early 20s for the success of these elite Javelin throwers. The results suggest coaches should approach the early 20s as a development period, preparing their athletes for their peak performance in their mid and late 20s.

50 ATHLETICS COACH - AUGUST 2017

47 52 57 62 67 72 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 DISTANCE (M) AGE

70 75 80 85 90 95 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 DISTANCE (M)

Figure 2: Season's Best performances of the top 8 women

Sara Kolak Sunette Vilijoen Tatsiana Khaladovich Kathryn Mitchell

Thomas Rohler Julius Yego Dmytro Kosynskyy Antti Russkanen

Figure 3: Season's Best performances of the top 8 men at the

Maria Andrejczyk's personal best is considerably better than any other of the top 8 had achieved at the same age. Can she continue to improve in her 20s or has she peaked earlier?

Barbora Spotakova Maria Andrejczyk Lu Huihui Christina Obergfoll

at the 2016 Olympic Games

Keshorn Walcott Johannes Vetter Vitezslav Vesely Jakub Vadlejch

2016 Olympic Games

Thomas Rohler has shown remarkably consistent improvement throughout his career, culminating in his victory at the 2016 Olympic Games. Mike Barber gave a fascinating insight into Rohler's unique training schedule in the Fourth World Javelin Conference Report (Athletics Coach - January).

Silver medallist Julius Yego showed the most improvement of all athletes studied from 20 to 26 - from a PB of 74.00m at 20 to 92.72m at 26.

PERFORMANCE 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 AGE

PEAK

25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 AGE

Kathryn Mitchell's fantastic performance at Rio highlights the potential of throwers to achieve their best performances into their 30s.

Statistics from the IAAF 51

ASK THE EXPERTS

WITH SENIOR OFFICIAL IAN COLQUHOUN

Your chance to connect with the experts of their field

In the April 2017 edition of Athletics Coach, Level 3 Track Official Ian Colquhoun and his team of leading Australian officials kindly offered their time to coaches to help answer any questions that you had regarding the rules of Track and Field.

Q: Dear Ian,

I've heard that when starting a race, if an athlete stumbles out of the blocks when the gun is fired, the starter can call them back as an unfair start but not as a false start.

Is this correct and what would be the finer rules of the situation?

Andrew Frend

Response provided by Starter Peter Sinfield

A: The short answer is yes as the Starter has 'entire control of the athletes on their marks' (IAAF Competition Rule 129.2) and this includes the entire start process.

"The starter...who is of the opinion that the start was not a fair one shall recall the athletes by firing a gun." Therefore, a Starter has the right to recall a race if in his or her opinion it was 'unfair'. This then becomes the point of judgement; is an athlete stumbling out of the blocks an 'unfair' start?

There can be technical reasons for a Starter to make this judgement call. They may have considered there had been block slippage, which resulted in the athlete stumbling. Alternatively, the Starter may discerned there was some other extraneous reason that caused the athlete to stumble at the moment of firing of the gun, such as a second 'retort' caused by the gun echoing off a grandstand.

Finally, it should be noted that a Starter may also consider that an athlete stumbling out of the blocks has been provided a fair start and therefore will not recall a race. It is a judgement call and one that experience and intuition play a factor in.

I hope this provides some guidance as to why a situation may have occured.

***

52 ATHLETICS COACH - AUGUST 2017

(IAAF gun." becomes

53

that have the

Q: Dear Ian,

In Long Distance (track and road) events, are there any restrictions on an athlete blocking another athlete? Is an athlete allowed to move across the track to make it more difficult for another athlete to pass? If not, how is this assessed by the officials?

Edward Chang ***

A: Thank you for a very thought provoking question. In any event an athlete is entitled to 'hold their ground' provided in doing so does not impede another athlete. This rule is very much open to interpretation as to what is accidental contact or obstruction. When I am lecturing on this area I say "think like an athlete and act like an umpire." What I am trying to say is that the umpire should place themselves in the shoes of the athlete involved in the incident and consider:

i. is it a normal part of racing?

ii. is it beyond what is considered fair racing?

If the answer to the latter question is yes, an umpire's report has to be made.

The Athletics Australia Umpire's Report Form that is used in these cases asks the official to judge whether the contact was deliberate and whether an advantage was gained by the offending athlete. An umpire will complete this form and pass it to the Track Referee to make a decision. The Track Referee can then consult the track umpire making the report, the athlete(s) involved in the incident, any video evidence that is available or any other means in order to make a fair decision on the matter.

I hope this clarifies the situation for you.

Ian Colquhoun

54 ATHLETICS COACH - AUGUST 2017

All Accredited Athletics Coaches have access to the Level 1 and Level 2 Officiating courses online through the Learning Portal. The courses introduce the technical rules and regulations of your selected event group and are a great way to ensure that you understand the finer regulations of the sport.

55 ASK THE EXPERTS

Q: Dear Ian,

At our LA Zone Competition, held at different grounds to our club, a fosbury high jump site was set up with the uprights and bar positioned approximately 30cm in front of the mat.The reason that the bar was placed that far in front of the mat was that the heavy uprights on wheels were used without the corner cut out mats. The uprights had large bases on them so the mats could not be placed on the base of the upright as the bar would be dislodged on the athletes landing.

I had two athletes that I coach in the competition find this difficult in judging their run up and identifying their take off position.

At our club we slide the metal base of the uprights under the mat so that the bar is over the front of the mat. With this type of set up the athletes obviously use the mats as a reference point in determining their take off position. With the mats being positioned 30 cm behind the crossbar the athletes had difficulty in judging their run up. Additionally no white line was drawn on the ground under the bar.

IAAF Rule 182(10) has a note stating "The uprights and landing area should also be designed so that there is a clearance of at least 0.1m between them when in use, to avoid displacement of the crossbar through a movement of the landing area causing contact with the uprights". This means that the site set up as it was is permissible in accordance with this rule. The only thing is that no line was drawn on the ground which is required under the IAAF Rule 182 2 (b).

This rule concerns me as if officials set up the bar say 50cm in front of the mat the site would be compliant with this rule. However, I am sure that most competitors would find this difficult.

Since then I have discovered that in the IAAF

Track and Field Facilities Manual at 6.2.3 it states that "the landing area may have cut outs to allow the front of the landing area to be placed immediately under the crossbar". At our Zone competition the adjoining site had cut out mats with the bar above the front of the mat. Had the competition been held at that site I am sure that my athletes would of performed to their usual ability.

Consequently, I take it that you can have two different types of set up. I further take it that I need to coach my athletes to be proficient at jumping at both types of site set up as when you compete at different grounds either type of site could be encountered. It is particularly a problem if the bar is set up more than 0.1m in front of the mat. After talking with Anne Masters, a Level 5 coach in Perth, she suggested coaching the athletes to use the upright as a reference point.

I would appreciate your thoughts on the above and also do you feel that the rule should be changed to state that the distance between the uprights and landing area be at or no more than 0.1m.

As clubs are starting to purchase cut out mats do you feel in the future that the rule will eventually be changed requiring the bar to be positioned over the front of the mat. I have noticed at the Olympics even though they are using cut out mats that they still place the bar approximately 0.1m in front of the mat.

John Cowan

***

Response provided by Jumps Official Marion Buchanan.

A: I understand coaches frustration in raising this question.

The IAAF rule 182.10 states that the uprights and landing area should be designed or

56 ATHLETICS COACH - AUGUST 2017

placed so that there is a clearance of at least 10cm between then in when use. That means having the landing area behind the line of the bar, however 30cm makes a huge difference to the intent and would create difficulty for the athlete in working out their run up as you have mentioned.

At senior level competition and Little Athletics West Australian events this will be the setup used and normal spacing will be approximately 10cm. However, when it comes to Little Athletics club competition days, set up is usually left to a few volunteers and competitions run by volunteers that are not necessarily educated to the correct set up or reasons for these regulations.

The IAAF rule 182 also indicates that there is a need to provide a 5cm wide adhesive tape placed between points 3 metres outside of each upright, the nearer edge of the line being drawn along the vertical plane through the nearer edge of the crossbar.

This assists the athlete to make and officials to judge legal jumps per the Rule

182.2b:“The athlete will fail if they touch the ground including the landing area beyond the vertical plane through the nearer edge of the crossbar, either between or outside the uprights with any part of the body, without first clearing the bar. “ The exception is if they are seen to touch the landing area but not to gain any advantage . The provision of the 5cm line and the understanding of the use of the line is also missed at normal Little A centre competitions .

At the end of the day the way to alleviate issues such as this is to have educated officials at all competitions. Officials are most commonly volunteer parents at many centres, as are the Technical managers and some will participate in education and others will not thus we have the circumstances which John has found.

I thank John for bringing this to our attention and suggest that he and other coaches and official volunteers attend a Workshop or Education Seminar that is run by either LAWA, AWA or the Officials club of WA.

57 ASK THE EXPERTS

Don’t miss a moment

Click or tap to visit

the

moment from London! the London 2017 Hub

Photo by Mike Hewitt/Getty Images

Photo by Mike Hewitt/Getty Images

Performance and a Belief of Free Will

What is the relationship between athletic performance and an athlete’s belief of free will?

Does a greater belief in one's ability to control their own behaviour and define their own outcomes influence what they can achieve?

How does a coach placing greater responsibility on the athlete for their own performance influence the athlete's attitude and motivation?

The presence or absence of free will has been a critical point of contention in psychological, biological, sociological and theological studies for hundreds of years. On the extreme sides of the debate, there are those who believe in complete free will, arguing that every action we take is the result of a series of choices that an individual makes (Libet, 1999). Conversely, others argue in support of a deterministic view where all actions taken are the unavoidable result of previous causes (Klein, 1990). An important component in this discussion is the understanding of whether there is any value for an individual to believe in free will. If one views all of their actions as the unavoidable consequences of past events, does that negate personal responsibility

and make an individual less likely to engage in conscious decision making? Understanding the benefits of the belief of self-determinism is important in explaining why it is a commonly held view that we have unimpeded choices over our own actions and what advantages that affords. This article will analyse published works on the topic to contend that the belief of free will is important in assisting people to engage in conscious thought to allow for greater regulation of their behaviour. This provides benefits in the improved physical performance, higher feelings of self-worth and increased pro-social behaviour.

60

“Individual differences in the endorsement of the belief in free will are a significant and unique predictor of achievement”

- Feldman, Chandrashekar & Wong (2016)

Excessive rationality restricts the belief of the athlete to push the boundaries of effort and belief in the incredible

- Yu, Gou & Xu (2008)

Translated from Mandarin

61 SPORTS PSYCHOLOGY

Belief of Free Will and General Performance

There have been numerous studies that have demonstrated that altering the level of personal responsibility that a person believes to have will alter the way that person actually behaves. In a study by Henderlong and Lepper (2002), it was suggested that children would improve their performance in tasks after receiving sincere praise for their competency or effort in previous attempts. In contrast, children who would receive feedback suggesting that they succeeded exclusively as a result of external factors such as the performance of others or the ease of the test would fail to improve their performance in subsequent tests. It is believed that this phenomenon occurs as a result of undermining the child’s intrinsic motivation and perseverance by removing the feeling of control that the child has on the outcome of the test. Therefore when the child encounters a similar test or challenge in the future, they may be less likely to be motivated or persevere with the challenge as they believe their success or failure is out of their control, determined by external factors.

Mueller and Dweck (1998) observed a similar outcome in a study where children who were praised for their hard work performed greater and reported higher levels of enjoyment in difficult tasks compared to children who were told their success was only a result of their natural abilities outside of their control. This study demonstrates how attributing responsibility to children in how they perform in a test can influence their future motivation in a similar task. For coaches, it is important to consider this effect when offering praise to their athletes after a good performance. By reinforcing the qualities that allowed athletes to achieve success such as their determination and hard work you can atrribute the success of the athlete to factors within their control and support their ongoing motivation to compete and perform at a high level.