ATLAS

STATEMENT OF SOLIDARITY WITH PALESTINE

This statement does not reflect the views of all Atlas Magazine members or all Emerson students.

Since 2011, Atlas Magazine has been for and by the people. We have prided ourselves on our ability to give the Emerson community a space to express themselves through their words, art, and photography. The word atlas means a collection of maps, intertwining stories and illustrations together, considering the Earth as whole, which is what we have always tried to do here.

We cannot say that we represent people’s stories and look the other way as the genocide in Gaza continues. The last few months have been incredibly painful to witness as 30,000 people have been killed and almost 2 million people displaced from their homes. The atrocities committed against the Palestinian people are a gross violation of human rights and we encourage each and every one of you to educate yourselves and support their right to resistance, freedom and peace.

The genocide in Gaza is not as far removed from our lives as people would like to pretend. As students in a higher-learning educational institution, it is our duty and responsibility to question the injustice around us and actively resist oppression. It is impossible to fathom that as we continue our daily lives, the worlds of ~3 million people have been decimated. It may feel fruitless to dedicate ourselves to a cause where the people capable of change refuse to do so, but it’s essential that we do. Educating yourself and actively supporting Palestinian freedom may feel heavy, but living through it is exponentially heavier.

We also want to express our disappointment in Emerson College and President Jay Bernhart for the institution’s treatment of students, particularly students of color, who have spoken out on these issues. We stand in solidarity with Emerson Students for Justice in Palestine, the Emerson Student Union, and the 13 students arrested for enacting their personal freedoms and peacefully protesting on Friday, March 22nd. We find it extremely distressing that many students do not feel safe or supported by this institution and we call on Emerson College, Jay Bernhart, and the Board of Trustees for accountability beyond discussions. We call for actions not words.

As we continue to work together as a magazine towards a place where people feel comfortable to express their stories, we aim for it to include the realities of the world around us. The struggle for liberation in Palestine is not a solitary issue and never will be.

The truth is, no one of us can be free until everybody is free. - Maya Angelou

PERMANENT CEASEFIRE NOW:

Annalisa Hansford, Annie Douma, Arshia Nair, Arushi Jacob, Audrey deMurias, Ayaana Nayak, Callan Whitley, Carli Bertonneau, Catherine Kubick, Cleo Laliberte, Diki Pattnaik, Elise Guzman, Ellye Sevier, Emilie Dumas, Emma Cahill, Erin Norton, Gandharvika Gopal, Hannah Hillis, Izabella Pitaniello, Jadyn Cicerchia, Jemma Sanderson, Kai Etringer, Kate Valentine, Lilli Drescher, Lily Suckow Ziemer, Liz Gómez, Lucy Latorre, Meg Boucher, Meggie Phan, Meredith Gross, Molly DeHaven, Paulina Poteet, Rebecca Calvar, Riya Patel, Rowan Wasserman, Sidnie Paisley Thomas, Sophie Rasmussen, Sophie Roberts-Fishman, Sydney Flaherty, Ugne Kavaliauskaite, Vara Giannakopoulos

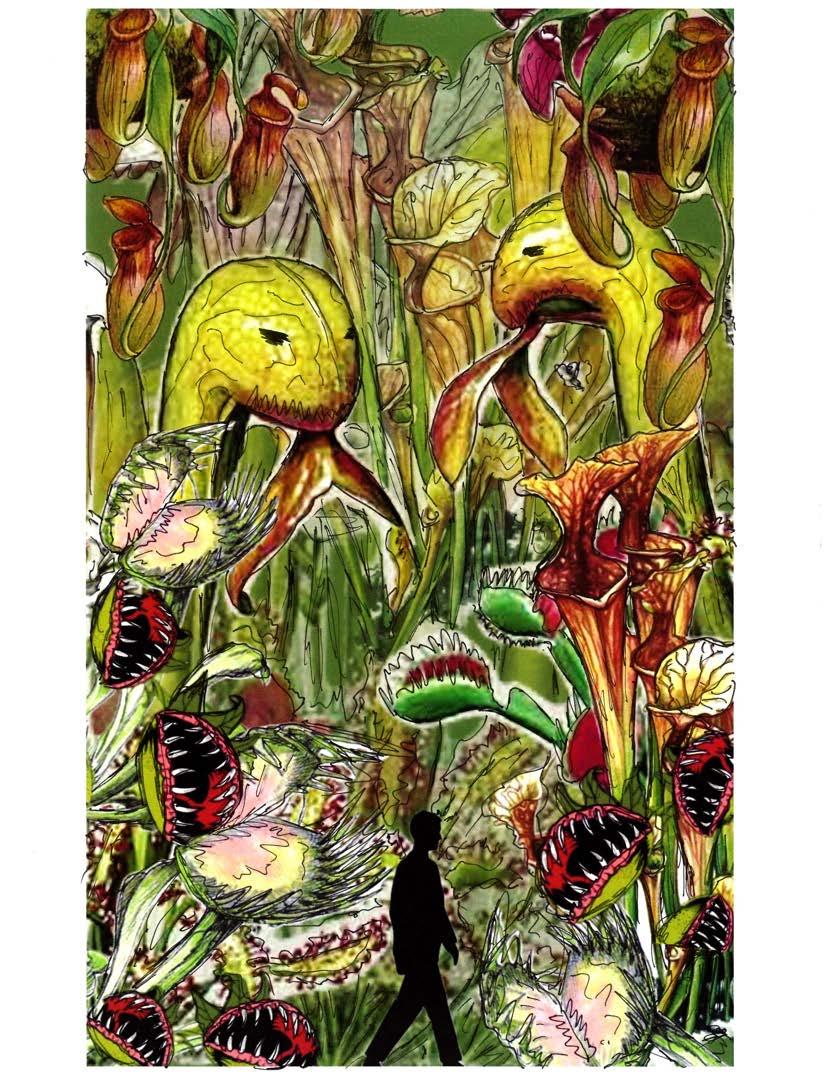

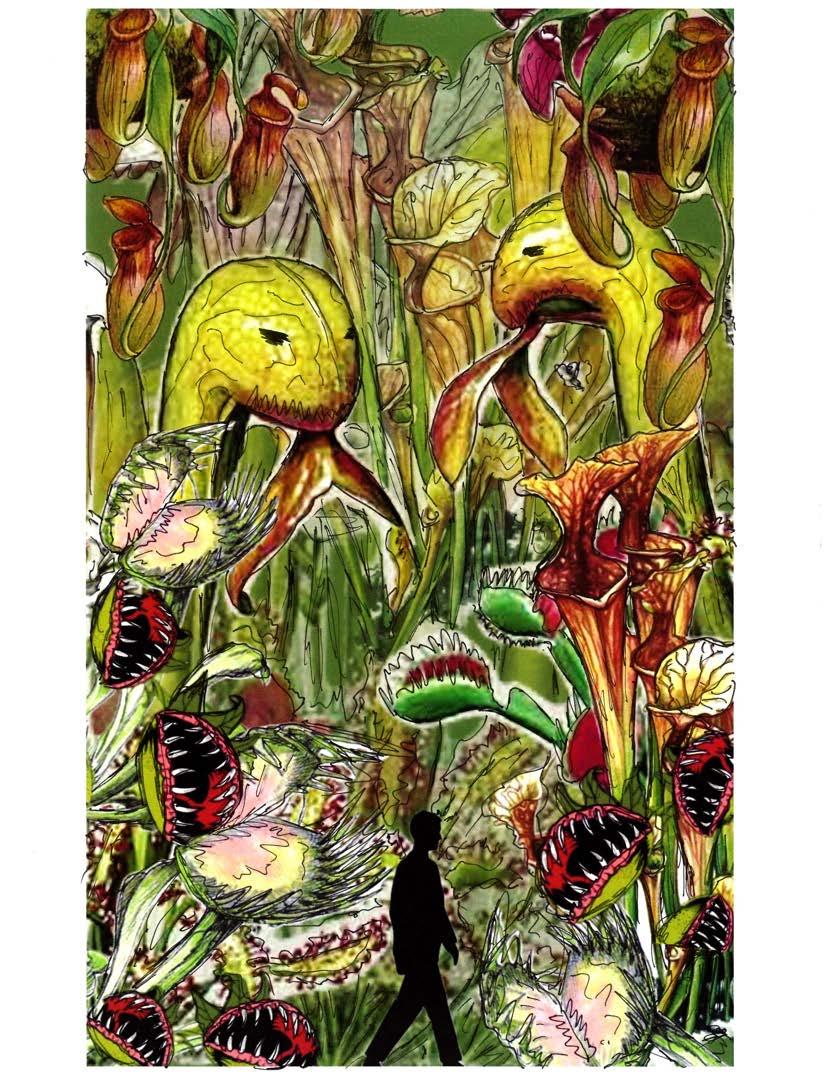

Devour

Welcome Arts Style

M eet The Executive Board

by Henna Cook

What are they devouring currently?

Annie Douma Treasurer & Social Media Director Chocolate Lava Cake

Meggie Phan Diversity Chair Croissant

Ellye Sevier Editor-in-Chief Pho

Erin Norton Creative Director Baklava

Annie Douma Treasurer & Social Media Director Chocolate Lava Cake

Meggie Phan Diversity Chair Croissant

Ellye Sevier Editor-in-Chief Pho

Erin Norton Creative Director Baklava

Rowan Wasserman City Editor Bahn Mi

Hannah Hillis Event Coordinator Petite Fours

Riya Patel Arts Editor Grilled Cheese

Catherine Kubick Globe Editor Pancakes

Emma Cahill Director of Photography Strawberries

Kate Valetine Head Copyeditor Hot Chocolate

Ayaana Nayak Illustration Director Strawberry Shortcake

Jemma Sanderson Style Coordinator Cherries

Angy Beare Beauty Director Fresas Con Crema

Sydney Flaherty Style Editor Spaghetti

Rowan Wasserman City Editor Bahn Mi

Hannah Hillis Event Coordinator Petite Fours

Riya Patel Arts Editor Grilled Cheese

Catherine Kubick Globe Editor Pancakes

Emma Cahill Director of Photography Strawberries

Kate Valetine Head Copyeditor Hot Chocolate

Ayaana Nayak Illustration Director Strawberry Shortcake

Jemma Sanderson Style Coordinator Cherries

Angy Beare Beauty Director Fresas Con Crema

Sydney Flaherty Style Editor Spaghetti

Our Writers and Creative Staff

Writers

Jadyn Cicerchia

Catherine Kubick

Sidnie Paisley Thomas

Audrey deMurias

Vara Giannakopoulos

Lily Suckow Ziemer

Paige Shepherd

Arshia Nair

Liz Gómez

Gandharvika Gopal

Meggie Phan

Meghan Boucher

Lucy Latorre

Reese Panis

Fer Cantu Z

Rowan Wasserman

Elise Guzman

Ayaana Nayak

Annalisa Hansford

Sophie Rasmussen

Sydney Flaherty

Copyeditors

Kate Valentine

Rachel Dickerson

Meggie Phan

Lilian Holland

Gray Gailey

Kai Etringer

Caroline White

Carli Bertonneau

Dikshya Pattnaik

Jadyn Cicerchia

Photographers

Emma Cahill

Luiza Lamkin

Lilli Drescher

Fiona Paige Brown

Emilie Dumas

Illustrators

Ayaana Nayak

Gandharvika Gopal

Josephine Fontana

Henna Cook

Designers

Erin Norton

Rebecca Calvar

Celeste Ocampo

Ugne Kavaliauskaite

Rheya Takhtani

Molly DeHaven

Lilian Holland

Josephine Fontana

Annie Douma

Cam McLean

Gianna Silar

Jade Cuza-Danelian

Aravind Kancherla

Paulina Poteet

Sofia Sarmanian

Celeste Ocampo

Socials Set Management

Cleo Laliberte

Jade Cuza-Danelian

Sara Bojarski

Sophie Rasmussen

Aravind Kancherla

Stylists

Jemma Sanderson

Cleo Laliberte

Meredith Gross

Chloe McAllister

Henna Cook

Makeup Artists

Angy Beare

Cleo Laliberte

Izabella Pitaniello

Elise Guzman

Chloe McAllistar

Sophie Roberts-Fishman

Letter From The Editor-in-Cheifs

Dear Reader,

I’ll admit, this letter has not been easy to write. I have struggled to encapsulate the duality of emotion that has come with my last semester at Atlas Magazine and Emerson College.

I am filled with so much love and gratitude when I look at all that we have accomplished this year with Atlas Magazine, and at the two beautiful issues we have produced. I have been involved with Atlas since I first came to Emerson, and there is a reason I have stuck with it. Here, I immediately found a community and a safe place for expression and exploration and learning. I hope that I, as a leader, have been able to continue this energy throughout the last three issues, a task which would have been impossible without the entirety of our amazing staff (over 50 students!), our committed Executive Board, and our leadership, Erin and Arushi, whom I love and respect so much. I know that I am leaving this magazine in the best possible care.

Though I am delighted and grateful to bring this new issue of Atlas Magazine into your hands, I must also be honest and speak to this moment in time and the distress many of us are experiencing.

Our community is in pain. We have been grieving, for the last six months and more, for the Palestinian people. We have also been outraged for our community here at Emerson, and the discrimination that many of our peers have experienced at the hands of this institution.

Devour was a theme we chose to reflect our collective zest for life after coming out of a pandemic, while also calling out our consumerist society. I feel that this also now calls attention to those in our world who are unable to share either sentiment, whose lives are continually jeopardized, ended, and displaced by American imperialism. I want to dedicate this issue, my last, to the people of Palestine, the Congo, Syria, Iran, and all other peoples being displaced and killed by forces of colonization.

Please consume the following creative works of our fellow students with care, and let this issue stimulate joy, grief, nostalgia, thought, and action. Thank you. Your readership means the world to us.

With love, Ellye

Dear Atlas readers,

I’ve been on the Atlas staff since I was a freshman, and I truly feel like I’ve grown with the magazine over the years. A large part of my journey at Emerson has been about wanting; wanting to learn as much as I could in these four short years, yearning to absorb new experiences and craving spaces for creativity and challenges. And that’s not a solitary feeling for anyone at Atlas.

The theme “Devour” speaks to us all, whether you look at it in a literal sense regarding food or instead think about the most intense crush you’ve ever had. It’s the adrenaline in your veins that forces your feet to move, the serotonin in your bloodstream as you find moments of happiness and the intense, desperate longing of wanting something so badly you can’t breathe.

This has been such an incredible journey to be part of as co-editor-in-chief for the first time ever! I want to thank the entire Atlas staff for their never ending supply of creativity, passion, and sense of community. You’ve all done such an incredible job and I can’t wait for you to see your work in print!! To Erin, thank you for being a creative genius and welcoming me into your world with such warmth. To Ellye, thank you for always being so steadfast, encouraging, and kind. And most of all, thank you for trusting me with your baby, I promise she’s safe with me :)

I hope you all love this issue as much as I do!

Love, Arushi Jacob Co-editor-in-chief

Arts

Photographed and styled by Fiona Paige Brown

Modeled by Taylor Paine and Loey Jones-Perpich

Makeup by Izabella Pitaniello

Artwork by Gandharvika Gopal

Designed by Rheya Takhtani and Celeste Ocampo

Swallow Me

By Jadyn CicerchiaIwas 12 years old the first time I realized I was fat. My friend and I were having our first grown-up trip to the mall. You know, the one where your parents finally leave you alone to pick out your own things. We were in an Old Navy and I followed my friend to the jeans section. I had never bought jeans for myself and was dumbfounded by the numbers on the tags. She turned to me and said, “I wear a size four, you’re probably the same as me,” so I picked up the size four and found my way to the dressing room. I didn’t understand when they barely made it past my knees, but I felt a subconscious burn of shame that left me too embarrassed to be seen grabbing a new size. I had never really considered my body before that moment. I don’t think most people do until a certain age.

A part of me had still absorbed the magazine covers and the celebrity gossip TV shows, so I had an inkling that these jeans not fitting me was somehow mortifying. With tears in my eyes, I ruined our grown-up shopping trip, picked up my phone, and called my mom, who had been shopping in a different store. She came bursting into the dressing room with a stack of brightly colored jeans and explained to me that people vary in size. For example, she was 00, which is not the sort of information that I found to be helpful at the moment. I ended up walking out of the store with a size 8 tucked discreetly under my arm, fearful that my friend would see. Our moms gave each other a look that I didn’t understand at the time.

The first time I fully understood that being fat was something bad was that summer. My friends had begun to wear bikinis, and I wanted to join in. My mom and I were standing in my room, trapped between my bed and my mirror, and my simple question about buying a two-piece bathing suit had turned into a hostile argument. She wouldn’t let me get one and refused to tell me why, but I wasn’t going down without a fight and shouted that all the other girls were doing it. Finally, my mom couldn’t take it anymore and screamed, “people who look like you can’t wear things like that!” I turned to my mirror and in my small 13-year-old brain, it dawned on me that people thought I was ugly, and those people even included my mother.

I hated my mom for a long time for saying that. But now I understand what it is like to grow up as a woman; all you are ever told is what you need to fix about yourself. My mom didn’t care about what I looked like, she only feared I would be torn apart for it the same way that she probably was, and the same way that all the women before her were. She feared society would swallow me.

There is not a day that has gone by since that moment where I haven’t thought about how I look. I let the thoughts devour me. I don’t have a single picture of myself from my first three years of high school because I feared being faced with the reality of what I looked like. I regret not having any memories from those years so much. I hate the way I allowed others to run my life.

People don’t understand how hard it is to find self-confidence when people look at you as though you are subhuman. I would see people like me in stores, on the street, and even on the beach, but never on a TV screen or a billboard. My body was never described by an author in a book. You can tell that the general public would prefer a reality where you didn’t exist. The one place I could be found was on the cover of a gossip magazine, bright yellow headlines screaming something like “random celebrity packs on the pounds!!!” I would never look at someone and think that being a certain weight makes them ugly, but when that is what everyone tells you, it begins to feel like the truth.

“She feared society would swallow me.”

“Damn. I would have killed it in 16th-century England.”

“They are fierce and strong and stunning and full. ”

I watched as all my thinner friends began receiving romantic attention, and it never came to me.

I stood in the jewelry section as they shopped because none of the clothes in the store fit me.

I felt pretty for the first time when a boy asked me out during my freshman year of high school only to find out that he was dared by his friends to ask out the fat girl.

I sat in silence during family movie nights when my Dad would point out which actresses had gained weight. I wonder if it ever occurred to him that I was even bigger than them.

I was either ignored or bullied, and I watched as all the girls on social media who were shaped just like me and that I thought were beautiful were torn to shreds in the comments.

And lastly, I remember when I lost some pounds at 16 years old, and the same friend that I went to buy jeans with all those years ago said “Jadyn, have you lost weight? You look so much better!”

It is really fucking hard not to let these things swallow you up.

My perspective slowly started shifting when I began spending more time in museums. My parents love art, so I grew up with that instilled in me. I always appreciated the colors, the techniques, and the way an artist could capture emotions. But it only dawned on me what I was really looking at once I was older.

My eyes, full of wonder, gazed at the portraits of women from hundreds of years ago. Some were painstakingly posed, sitting up straight on the edge of a plush chair, the occasional dog or child at their feet. Some were lounging, bored, eyes unfocused, and looking out into space. Some looked you dead in the eye like they were trying to seduce you or tell you a secret. Some appear so forlorn you can almost hear them sighing. Some are simply walking by in the background. Some are dying in the arms of another, clothes torn and bloody. I took in these women who were beautiful and important enough to be painstakingly replicated onto a canvas and hung on a wall for the world to see. But the thing that spoke to me the most was the way these artists had drawn what so many would currently consider flaws in extreme detail. These women have round faces, double chins, full squishy arms, and wide rounded shoulders. Their stomachs push against the fabric of their dresses. Some are even nude; painted from the back, the skin of their bum creased and puckered, the fat of their hips, and the rolls on their back, out for all to see. Painted from the front, their breasts and stomachs soft and hanging low, their thighs touching.

Damn. I would have killed it in 16th-century England.

They are fierce and strong and stunning and full. They take up space, and you cannot ignore them as they hang from the walls in their enormous frames—passersby oohing and aahing at their beauty.

Art can last forever and it will always be created. If you listen closely enough, art tells us that there is no such thing as ugly. Beauty standards fade in and out and are constantly changing. But to me, the human body never stops being art.

It is a strange thing to see people taking pictures of these women, wanting to keep the memories of seeing such beauty when I know that if one of these women came up to them in real life, they would probably consider her to be unattractive.

Art can last forever and it will always be created. If you listen closely enough, art tells us that there is no such thing as ugly. Beauty standards fade in and out and are constantly changing. But to me, the human body never stops being art.

None of this has changed how people treat me, but it’s helped me feel a bit less embarrassed about myself, and a bit more embarrassed at the callous actions of those around me.

So while people whisper their unkind words and diet plans in my ear, desperately trying to claw at my flesh and munch on my bones, dissolving me into nothing, so angry that they cannot fit me down their throat, I will sit back and relax, a smile crossing my face as I dab the corner of my lips with a napkin. Watch as I swallow them whole and then lick my fingers.

Just like those women in the museum, stomach hanging low, lips wrapped around an apple. Devour.

“Watch as I swallow them whole and then lick my fingers.”

“Watch as I swallow them whole and then lick my fingers.”

Vampires: Our Immortal Cultural Obsession

By Catherine KubickMany of us were just toddlers the first time we saw a vampire. No, not in the form of a blood-sucking beast or a sparkling sexy heartthrob. For many of us modern, Gen Z consumers, our first-ever exposure to a vampire came in the form of a puppet.

More specifically, a puppet who lived on Sesame Street. This specific vampire caricature played a surprisingly pivotal role in the development of young minds. Who is this fanged purple puppet with a little black cape and an outrageous Transylvanian accent who taught many of us the vital skill of counting? It is, of course, the aptly named vampire puppet: Count von Count. It is easy to forget that this vampiric image was introduced to the world far earlier than we could even imagine, in Bram Stoker’s world-famous novel, Dracula, or perched on the couch for a Twilight marathon. As silly as it sounds, puppets like Count von Count or even cereal box icons such as Count Chokula prove that vampire lore has sunk its fangs into our modern psyche in more profound ways than many of us may have realized.

For modern generations, it is not far off to say that the cultural depiction of vampires has undergone a massive transformation since the days of Nosferatu and Count Dracula. These creatures, once widely feared and renowned for their horrific nature in Victorian-era literature, are now more commonly associated with teen romance movies or horror dramas. Although it is unusual for someone to leave a movie theater trembling in fear after watching a vampire flick in the modern era, it is more than likely that they will depart feeling satisfied and entertained, proving that though no longer as frightening, vampires have not quite lost their allure. The mysterious qualities surrounding vampires ensure their continual presence in contemporary media. Their base characteristics—pale, fanged creatures of the night, sensitive to the sun,

thriving on a diet of human blood—are a goldmine for any storyteller, both traditional and modern. These distinctive components alone have sustained the vampire genre for centuries.

First presented as an allegory of repressed societal Victorian ideals, vampires were formulated as a means to demonstrate the manifestation and consequence of the perceived monstrosity of religious and sexual deviance. Though the first appearance of the vampire is widely thought to be in Bram Stoker’s Dracula, the first true literary record of a vampire in a work of literature is actually in the short story, The Vampyre by John Williams Polidori. The literary and Victorian origins of vampires ensured that the creatures were used as a monstrous motif to demonstrate how engaging in acts that quantify perceived evil or corruption can turn an ordinary human into a blood-sucking monster, a concept that has been riffed upon and restructured into a multitude of mediums.

Today, if you were to walk down the street and ask an average person to name a famous vampire character, their answers might include the usual modern suspects: Edward Cullen, Lestat De Lioncourt (the Tom Cruise version, of course), the Salvatore Brothers, and so on. These characters are notorious for their brash “heartthrob” and “sexy” personas and are written proof that the definition of vampires has shifted significantly to match the constantly changing expectations of contemporary audiences. The purely monstrous portrayal of vampires has notably evolved, with many narratives now adopting a brooding and romantic tone. Much of the vampire genre as we know it today is due to the work of Anne Rice and her series of vampire novels, the most iconic being “Interview with the Vampire.” Rice, during her career, garnered the title of the “Modern-Day Queen of Vampires.” Her reworking and restructuring of the vampire trope paved the way for other world-famous contemporary titles such as The Twilight Saga, Buffy the vampire slayer, The Vampire Diaries, and many more.

Rice’s work with her The Vampire Chronicles may be viewed as the saving grace of the modern vampire. The series possessed characters and relationships that transcended the villainous vampire tropes of old. Rice wrote her vampire characters as the protagonists of her narrative, which gave the vampire archetype new layers of depth and interiority. Each of her vampiric characters is unique and singular, possessing rich inner lives. This creative choice was a significant departure and subversion from the one-dimensional, evil vampire archetype that audiences were accustomed to seeing and paved the way for more nuanced portrayals of these creatures in popular culture. Rice imbued her vampires with a sense of vulnerability and romance, challenging conventional perceptions of the gothic monsters. The main relationship explored in her novel, featuring the characters Lestat and Louis, forged new ground for vampire fiction in late 20th and early 21st-century literature and culture. The queer relationship between these two vampiric characters was a significant marker in diverting from heteronormative tropes in the vampire genre. Through her work, Rice not only made vampires more sympathetic to readers but also expanded the boundaries of how these iconic creatures could be approached and. depicted, especially through a familial lens and partnership that resonates with a variety of audiences.

Love it or hate it, the modern vampire genre, as we know it today, boasts one of the most consistent and broad pop culture audiences ever known. There is an irresistible allure to the themes vampires represent. The struggles with mortality and relationships under the veil and constraints of nocturnal vampirism have proven to be excellent creative grounds for a prolific fiction genre that resonates across generations, with Rice being the revivalist author who gave vampires the modern twist they desperately needed to maintain their relevance in pop culture. The vampire genre has emerged as a flourishing cultural phenomenon, exuding a specific yet endearing amount of sappiness and romanticism. The loving depth that Rice explored with the queer vampire coupling of Louis de Pont du Lac and Lestat de Lioncourt was also a guiding light

that allowed vampires to become a fictional hallmark of the queer community. Their passionate and often tumultuous love affair in her narrative has inspired countless works of fiction and art that explore themes of love, desire, and longing within the context of vampirism. The brooding and rich character portrayals of these monsters with varying depictions of the nature of vampirism all take inspiration from Rice’s work. Her reinvention of the vampire as a romantic figure with complex emotions and moral struggles laid the groundwork for characters like Edward Cullen to take flight in the cultural landscape. Rice’s portrayal of vampires as brooding, tortured souls grappling with their immortality and the consequences of their existence laid the groundwork for contemporary authors and creatives, allowing for modern subversions of vampire tropes to reach new heights of cultural resonance.

The vampire renaissance of the early 21st century saw several iconic moments inspired by Rice’s work. Stephanie Meyer’s The Twilight Saga (2005), which sparked the Jacob vs. Edward phenomenon among teens, and the love triangle involving vampire brothers Damon and Stefan and their human muse Elena in The Vampire Diaries television series were central to this resurgence, followed by other works of television including True Blood (2009), What We Do in the Shadows (2014), and other works also played significant roles. None of these would have been possible without Anne Rice’s vampire remodeling. The brooding and complex vampires we know today, with their immortal existence and intricate relationships, offer readers and viewers a sense of escapism and fantasy. They allow people to immerse themselves in worlds where love knows no bounds, and the supernatural coexists with the mundane. In the effort among consumers to escape the pressures of everyday life, vampire fiction offers a space where true human emotion runs deep and where we can see elements of ourselves in even the sappiest and most absurd subsets of the supernatural. Vampires have become an undoubtedly integral part of popular culture. Whether they are found on a cereal box, on the cover of a teen romance novel, or as a puppet on a popular American children’s show, they have asserted themselves as the blood-sucking monsters we cannot help but love.

“In the effort among consumers to escape the pressures of everyday life, vampire fiction offers a space where true human emotion runs deep and where we can see elements of ourselves in even the sappiest and most absurd subsets of the supernatural.”

Unearthing the Sullen Girl

By Sidnie Paisley ThomasFiona Apple and her music have long been synonymous with female angst and passion, two things girls are taught to be ashamed of from a young age. Because of Apple’s radical ethos that it’s your right to be as loud and open with your emotions as you want, her listeners wear these titles with pride in the face of stigma. When her debut album “Tidal” was released in 1996 it was just that, a rush of unapologetic feeling and emotion washing over the culture.

On the opening track “Sleep To Dream”, she sings passionately about a love who wronged her; “This mind, this body, and this voice cannot be stifled by your devious ways; So don’t forget what I told you, don’t come around; I got my own hell to raise.” While the innocence of sleeping to dream is lost, the childlike belief in your right to raise hell remains. Apple doesn’t let this destruction of her life stop her from throwing a tantrum; it only enables her to make more noise. Apple was fourteen when she began writing this song and was eighteen by its release. At fourteen, I shared similar feelings of anger and angst, but not the same confidence in my right to rage. By eighteen, the belief that I had to quiet myself for the comfort of others had long been cemented in me. Through my relationship with her music in recent years, I’ve reconnected with the girl who knew her sadness was deeper than just “sullen”. Her poetic songwriting of powerful metaphors pulls you into her riptide and doesn’t wash you ashore until the last second. Once you’re released, you’re not overcome with Apple’s emotions, but immersed in your own.

At the 1997 MTV VMAs, Apple won the Best New Artist award and gave her iconic speech claiming, “This world is bullshit.” Speaking on the music industry, Apple, although fairly new to it all, had already had enough of the way young girls’ careers were micromanaged to ensure they were palatable for consumers. After her year of rapid success, she feared she was set on a path of superficiality to maintain her profitability. What Apple didn’t realize was that her dedication to raw emotion and truth regardless of the cost would keep her from selling out. Not only that, but the scrutiny of being a teenage girl in the spotlight was enough to keep her to keep her focused.

During her debut year, she defended herself from critics wielding comments about her body and navigated an industry full of men who wanted to control her behind the scenes. From the very beginning, Apple had to work overtime to establish control over herself both as an artist and a person. Her artful control of this dichotomy is seen during her interview on the Howard Stern Show after the release of “Tidal” in 1997, where he spent the interview hitting on Apple inappropriately. Stern asks about her weight, her boyfriend, and the length of her shirts; he even antagonizes her band members, asking if they’ve ever sexually pursued her. Through it all, Apple stays calm, not allowing Stern to make her uncomfortable. The only moment he has the decency to stop is when they discuss Apple’s assault, which he abruptly brings up when asking Apple if she’s “mentally disturbed.” She tells him that she was raped by a man in her building at only 11 years old, to which Stern responds, “That sucks, I’m sorry.” Apple speaks on it briefly saying that it doesn’t bother her anymore; “If you can’t say something about it then it has way more power than it deserves.”

This statement succinctly describes “Tidal” in its entirety. She sings in depth about emotions and situations that once had a hold on her, but will no longer because she’s able to acknowledge them, giving herself the power to be liberated and bestowing this same power onto her listeners. Hearing her sing and speak freely about her trauma rouses me to confront my own emotions with the same bluntness. It’s your right to raise hell when you’ve been wronged, no matter who feels uncomfortable or exposed. She’s learned through experience that the alternative is worse, something she touches on in the song “Sullen Girl”.

Is that why they call me a sullen girl? Sullen girl

They don’t know I used to sail the deep and tranquil sea

But he washed me ashore

And took away my pearl

And left an empty Shell of me.

a “sullen girl,” then take the time to help me. And so sullen I was; as my frown deepened and my voice lowered, I made myself as small as I could. After an onslaught of questions from my relatives and sparse answers from me, they gave up prying. “I guess that’s just young girls these days,” they said.

The expectation that young girls are one day full of life, then suddenly lose hope in the world and themselves, has come from generations of forced silence. We’re meant to let our emotions overcome us so that we drown underneath the weight of our feelings and submit to societal expectations of what we should be. Apple recognized from a young age that this wouldn’t do; she had no intention of being silent and even less intention of conforming. The act of being loud and unapologetic is terrifying because it’s only through our voices that we’re liberated. Apple’s declaration, “This world is bullshit,” sounded bratty to those who believe girls should be quiet. But in truth, it was meant to inspire girls to focus on themselves and what they feel is right, rather than the world they’re meant to aspire to. The world only seeks to diminish us, whether that be our hopes, our dreams, our melancholy, or our joy, in the end, leaving us with nothing. And in this lack, they assign us the label of “Sullen Girl,” removing our identities and individuality.

At the beginning of her VMA’s speech, Apple quoted Maya Angelou, saying “We as human beings at our best create opportunities,” and with every opportunity she’s been given Apple reminds us how vital it is to never be quiet or apologetic of ourselves and our emotions. She will not allow girls to be stripped of everything that makes them special and labeled sullen by the same people who took their joy away from them.

The History of Margiela Couture: A Path to the Innovation on the 2024 Spring Runway

By Audrey deMuriasFashion enthusiasts have known the Margiela name for decades, but more people around the world became fans of the great fashion house when the January 22, 2024 haute couture runway show grew to a viral sensation, and for good reason. Everybody everywhere has been buzzing about this show since the first model stepped out, yet many don’t know the man behind it all: Martin Margiela. Although many, including myself, have only heard the name from its recent spike in popularity, his unique fashion sense and inspiring personal journey that resulted in this latest spectacular show is essential to know when dissecting any important Margiela moment. your own.

Margiela was born in Belgium on April 9, 1957. He’s never specified exactly when he developed an interest in clothes, but at 22 he attended the prestigious Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Antwerp to study fashion. Before creating his own brand, he had the opportunity to work with the iconic designer Jean Paul Gaultier after graduation, undoubtedly an inspirational colleague for the young and ambitious Margiela.

In 1988, Margiela concocted Maison Martin Margiela, his own luxury fashion house based in Paris. His fame grew as the press talked about his extraordinary designs, calling him the “Father of the Sartorial Deconstruction Technique.” This approach popularized the utilization of non-clothing material to create wearable art, a concept us Bostonians will likely be seeing more of on the downtown streets sooner or later. He mainly designed muted, understated shades (especially varying hues of blacks, whites, and reds), a value still held by Margiela designers.

Another important aspect of his style is the theme of anonymity. He famously had his models wear headpieces to remain hidden, and Margiela himself was very mysterious, rarely doing press events or interviews or even appearing at his shows. The reasoning behind this was to keep focus on the clothing and their artistry rather than the models and himself, a prime example of how he cared about fashion for the art rather than for fame and fortune. He was also known for integrating traditional and modern style influences, a pattern that continued with his successors after his eventual retirement. Regarding his collaborations in the industry, he was important at Hermes from 1997 to 2003, a currently well-known luxury fashion brand and the home of the iconic Birkin Bag, while actively continuing to work on his Maison.

In 2002, Margiela was taken over by Diesel, a powerful and respected Italian-based luxury style company. This coincided with Margiela’s decision to leave fashion altogether, to the dismay of his admirers. I sometimes wonder what the brand would be like if Margiela was still involved, but as he didn’t seem to enjoy the work anymore, I understand his decision to pass his company down to worthy designers. He also reportedly stepped away due to creative differences with colleagues. After this, he began working in fine art and recently had his first art exhibition debut in Paris. For years, he chose to make no public statement on his leave, exiting the fashion world in the dark. At a deeper look, his decision to be very private adds to his desired mysterious reputation considering his famous emphasis on anonymity in his line.

Margiela’s brand is now curated under a head designer and opportunities in every new line and season for other creatives to show their worthiness in representing Margiela as co-designers. Anyone leading the creation of a line must hold the same passion and values as Margiela himself. It’s clear in an interview before his resignation that he viewed fashion design as more than just clothing, stating that “color is a temperature, an intensity, a clash and also a harmony.” He goes on to explain that “skin is a protective shield, fabric is a medium, texture is the result of time, construction is a means to a certain end, craftsmanship is a fruit of time…” These unconventional visions he had of fashion seeped into every one of his designs.

Margiela may not be considered a household name compared to Gucci or Prada, but it’s a trea sure appreciated by those with an enthusiasm for fashion. Pop culture references to Margiela’s brand sometimes cause small spikes in interest, one example being Kanye West referencing him in lyrics, like the line “What’s that jacket, Margiela ‘’ from one of his most famous songs. This line sparked some interest in the brand as West’s large fanbase dissected his lyrics. Tying back to the anonymity aspect of Margiela’s designs, Kanye West infamously covers his face. Considering his multiple references and seemingly high interest in the brand, this could very possibly be inspired by Margiela. The Luxury brand is unique and experimental, yet was always in the background of major fashion shows. Until now.

The Margiela name made a well-deserved and long-awaited boom in the haute couture fashion show conversation in January of 2024, despite its namesake having no direct connection to the recent designs. With a great start, the arguable “hook” of the show was a short film directed by Baz Luhrmann, most recently known for directing ‘Elvis’. Having a high-profile directed short film to kick off the show is only the cher ry on top of the entire assembly and execution. Despite the potential distraction from audience excitement that Luhrmann’s involvement could’ve created, the show production and clothing pieces themselves not only called for their own attention but arguably took it away from the Elvis director’s opening.

That is how iconic it was.

John Galliano was the main designer of the pieces displayed at this re cent show. He was an important figure in fashion design in the 20th century, eventually falling out of relevancy (he was “canceled” before it was a thing). His designs famously incorporated theatrical aspects, in cluding model choreography, set design, and costume-like pieces. He can be compared to Margiela for their quirky and creative similarities, including the aspect of anonymity and a darker, mysterious attitude in their style.

For his work on the Margiela show, Galliano combined the artistic theories and ideas Margiela himself favored, while also putting his own spin on the designs. As if that’s not enough for a positively memorable visual experience, the makeup looks were one of my favorite details of the production.

Pat McGrath was the leading makeup artist and created a porcelain doll look on the models that caused commotion on social media due to the skill, technique, and originality of the artistry that was seemingly impossible for people to recreate.

In a way, this makeup art was just another utilization of the anonymity aspect Margiela used, and while you could see the model’s faces, their humanity was diminished by McGrath’s unparalleled artistic makeup. Galliano himself seemingly incorporated medieval or renaissance-esque aspects to the designs, like corsets and lace. While that’s a fashion trope itself, he made it distinctive by creatively combining that with modern pieces, like oversized leather jackets, quirky headpieces, and 21st-century footwear.

A final talking point of the designs circulating on Instagram especially was the sewn-on pubic hair on undergarments. This was certainly an interesting approach to Margiela, but I didn’t hate it. Galliano, while pushed aside in the past, has certainly put his name back on the fashion map by taking the soul of early Margiela and integrating his own vision, while avoiding any exploitation or distastefulness, and with great respect to the original designer.

To emphasize the great power the 2024 Margiela Couture show held, it was arguably the most discussed among not only those interested in fashion but with people from all walks of life, especially on social media. The true genius of what we can consider a collaboration between Margiela’s design signatures of storytelling through art and the talented Galliano’s take on them created an unforgettable line that rightfully stole the attention from other fashion house’s shows. The product of a name made famous by anonymity and its mysterious designer combined with designs led by the once controversial John Galliano has proven that fashion is much less linear than it could seem. Utilization of futuristic and traditional ideas is what innovates and invigorates far more than churning out meaningless trend after trend. True fashion is timeless as an art form, and cannot be held back by labels. This was known by Margiela and Galliano, which resulted in a juggernaut powerhouse of a runway that absolutely devoured the competitors.

Audiences Are 'Eating Up’ Cannibalism

By Vara Giannakopoulos

If you’ve been on any online space in the last few months, you’ve likely heard about those scenes in Saltburn (2023). You know, the ones where the main character is consuming other people’s bodily fluids, arguably the catalyst for the virality of the film. This isn’t the first (or likely last) time that the idea of “consuming” another person, or at least remnants of them, has gained traction in film media in recent years. Cannibalism is an ongoing fascination amongst audiences, particularly when used as a metaphorical device to convey obsession, longing, and carnal desire.

While Gothic and Victorian literature spearheaded using cannibalism and vampirism to symbolize toxic desire and gendered power dynamics, visual media adds new potency. Cinema and television enable these once purely literary metaphors to play out in lurid color and intimate detail. Horror provides the best template for this transition from abstraction to brutal reality–it lets viewers revel in taboos from a safe distance while feeling the vicarious thrill. Cannibalism has existed in films for nearly as long as the horror genre has been around (from Gow the Head Hunter (1928) to The Silence of the Lambs (1999)); however, it is the first time we are noticing a meaty trend of audiences actively seeking out metaphorical cannibalism in media. This increases demand for their production, with other popular films partaking in the recent “trend” of cannibalism, including Raw (2016), Mother! (2017), and Fresh (2022).

The vampire craze of the early 2000s and early 2010s brought on by the Twilight film franchise (adapted from the novels by Stephanie Meyer) and hit show Buffy the Vampire Slayer (19972003) resurrected interest in the trope, making it desirable to preteens. As a direct result, in the late 2010s and early 2020s, cannibalism film media skyrocketed. Bones and All (2022) garnered attention due to its vulgarity and gory use of cannibalism. Maren, the protagonist with a particular proclivity towards finger food, meets Lee, another teenager struggling with the incessant compulsion to consume long pig (disgusted to report this is cannibalism lingo for human flesh). The two fall in love, momentarily distracting those with queasy stomachs from the nauseating displays of their dinners. I’m still scarred by the film portraying skin to have a gumlike stretchiness as it’s being chewed off. Seriously, I almost walked out after that. However, if we dig deeper, director Luca Guadagnino utilizes his protagonists’ ungovernable hunger for human flesh to explore the all-consuming compulsions that can overtake a person’s existence—whether it be substance dependence, passionate infatuation, or complete confusion of the “self.” It’s weird to think that someone eating human flesh can represent all that, but it somehow works. At the film’s end, Lee begs Maren to eat him, “bones and all.” We can infer the metaphor extends towards her being accepted entirely, not despite who she is, but because they are one and the same. This is Lee’s final act of autonomy, and he chooses her; he knows better than anyone that the most delectable and terminal sacrifice he can make for love is himself. It’s romantic as much as it’s horrific.

It would feel negligent of me not to stress the repetitive appearance of cannibalism in queer media. Apologies for the crudeness, but filmmakers just love having LGBTQ+ protagonists chow down on people, as seen in Hannibal (2013-2015), Yellowjackets (2021-), and more. Often, consuming another human on-screen lets these characters channel raw emotions that queer audiences often connect with. Feelings like wanting intimacy while living in a judgemental world telling you that your desires are wrong. Fears of losing yourself and becoming whatever “other” hostile society sees you as. It captures anger and defiance at bigoted culture trying to get diverse identities to conform. By committing the ultimate “sin” of eating people, they get to symbolically scream at the top of their lungs against having to fit in and hide. It makes the old saying “you are what you eat” pretty thought-provoking considering that what these characters consume is a potent metaphor in itself. Their shocking acts hold up a cracked mirror, reflecting society’s own hunger for normativity.

In the 2017 film adaption of André Aciman’s Call Me By Your Name, the sensual scene in which Oliver eats the peach after Elio’s intimate encounter with it encapsulates the story’s portrayal of erotic and emotional, merging through a motif of metaphorical consumption. In the novel, Oliver says, “I want every part of you. If you are going to die, I want part of you to stay with me, in my system, and that’s the way I’m going to do it.” I mean... put it like that, it’s romantic. We can’t deny we all want a devotion that would make someone willing to eat a peach we defiled (if you do, you’re just lying). Aciman conveys the sense of limitless longing between the two men by Oliver devouring the sticky peach, which now symbolically represents Elio himself. It is an act of intimacy mimicking the sexual union that cannot openly occur between two queer lovers in 1980s Italy.

This act of “consuming” the peach echoes an innate, primal need to take Elio into himself, fusing into one being (correlating with the reason the film and novel are titled after the line “Call me by your name and I’ll call you by mine”). Aciman captures the metaphysical intertwining of these souls during one ephemeral summer through this single gesture rife with unspoken meaning. It was a curious choice for director Luca Guadagnino to not show Oliver’s literal consumption in the film, likely under the assumption that audiences wouldn’t grant a physical depiction of the act the same gracious reaction as the one in print. This choice mirrors that of many queer sex scenes: hinted at but not shown. In an interview with Pride Source, Armie Hammer (I’m not even going to get into that) states that there were more takes where he took bites out of the peach than ones that he didn’t, but the take that worked the best overall was one where he didn’t. Some ironies just write themselves.

What drives the enduring allure of watching fictional characters consume human flesh or drain blood, even as these acts repulse us in reality? Beyond “I don’t know, it’s a guilty pleasure?”, cannibalism metaphors channel societal tensions about dangerous desires and the urge to consume beyond reason. They symbolically devour victims, reflecting human struggles for intimacy, identity, and control—all while navigating norms declaring such cravings taboo. Audiences vicariously revel in the forbidden through horror scenes and villains, or invest in antihero protagonists that drag heroes into the darkness.

The recent popularity of Dahmer biopics proves so long as real monsters emerge, fiction will warp their shadows into new nightmares. Showcasing inhuman acts with human motivation compels both through relatable psychology and dramatic irony, knowing this violent urge outwardly faces judgment. Yet these characters indulge anyway, providing viewers temporary relief lending toward Aristotelian catharsis. As consumerism and desire drive culture ever forward, the need for cautionary tales about unrestrained appewtite will likely persist. Though audiences may grow fatigued of the cannibalism motif, the core hunger at the dark heart devouring moderation seems unlikely to starve. I know, I know, cannibalism jokes are in bad taste. Last one: no matter how repetitive the ingredients get, audiences keep gobbling up these cannibals—our appetite for the abnormal is apparently bottomless.

Style

Photographed by Emma Cahill Designed by Rebecca Calvar Modeled by Cleo Laliberte Styled by Jemma Sanderson

The Main Character at Panda Express

By Lily Suckow ZiemerAt least once a month, my friend Sydney and I take a pilgrimage to the George Sherman Union Panda Express. A lot of people criticize us for liking Panda Express, but every time I eat it I’m taken back to my childhood of mall food courts and days spent with friends. We don’t think of it as authentic Chinese food like most people fear, but as a taste of home. I can count on one hand the number of midwesterners I’ve met in Boston, and Sydney is one of them. We share similar tastes; we love Olive Garden, snow, malls, and of course Panda Express. Most people we meet from the coasts don’t understand it, so it’s comforting to have someone who has a shared idea of home.

Our trips to Panda Express have quickly become about more than just the food. Of course we’re motivated by a craving for orange chicken, but this Panda Express is like no other. The GSU is like a food court, only cleaner, fancier, and one of the Boston University dining halls. BU students have their pick of multiple chain restaurants in which they can pay with meal plan dollars or regular money, but unlike Emerson buildings, there’s no tap desks or security guards. The GSU is practically a public establishment, only plastered with pictures of BU’s Boston Terrier mascot Rhet.

When Sydney and I first arrived at the GSU after following Google Maps to the nearest Panda Express, it felt as if we were doing something wrong. We whispered and pushed each other to be the first to open the door, and foolishly walked up to the counter to order before being pointed into the direction of a kiosk. At every turn we were fawning over something new: the canned water, the wooden forks, the booth seating. If anyone had been looking closely, it would have been obvious we were out of place. We didn’t try to fit in, to disguise our behaviors. In a way, we wanted to be special in this special place. Even today the mystique remains when we enter the building and know everyone must assume we are BU students. We order our food feeling like undercover agents.

There’s an anonymity we find at the GSU, charading as people we aren’t by going to a place non-BU students don’t frequent. We sit for hours talking about whatever we want, knowing that no one we know is listening. But there’s also a sense of self importance. We feel mysterious, new, the center of attention. We aren’t just hungry for Panda Express, we’re hungry for this mixture of anonymity and attention that is hard to find.

This borderland between fitting in and sticking out exists no matter how many times we go. Sydney and I pride ourselves in being dressed up in comparison to BU students. We would look completely normal at Emerson in our wide leg pants and thrifted shirts. But in the world of Champion sweatpants and sports merchandise that is BU we like to think we stand out. It’s as though all eyes are on us. Who are they? Why have I never seen them before, they’re so cool! We’re anonymous, new characters in these peoples’ lives, and the main characters in our own.

know that we are not alone in this desire. Everyone’s heard of romanticizing your life, or convincing yourself that you’re the “main character.” TikTok is flooded with videos on how to dress like the main character. Some of them even feature sneaky and likely staged videos of a person in class or on the street. The text will read something along the lines of “in love with this girl who always dresses like the main character.” There’s also videos suggesting how to dress in such a way. But the sentiment is larger than the trends associated with it. Particularly in American culture, individuality is valued. We’re often jealous of those who have something we deem somewhat rare, whether it be attractiveness, wealth, or intelligence.

One of the easiest ways to take control of your individuality is with your style. At times, everyone has chosen whether or not to conform to the way others dress. Up until high school, I meticulously planned every outfit so as not to stand out. My friends and I would text to see if others would also be wearing leggings to school, and I leaped to buy the same shorts everyone wore under their middle school uniform skirts. As I got older, I felt more in control of my insecurities by wearing bold outfits. Even after uniforms disappeared in high school, it was the standard to wear leggings and sweatshirts every day. I’ll never forget wearing a dress to school for the first time. I’m not kidding when I say I’d never seen anyone do it before. But even at my most insecure, I found that it felt better to receive compliments on my outfit than to avoid attention in my sweatshirt. My style was how I controlled how others saw me. It was how I made people see me at all.

If you’ve ever stepped foot on Emerson’s campus you’ll know the majority of the population is extremely well dressed. I don’t mind being one of many dyeing their hair or layering shirts; if anything it has made me bolder with my choices. But I can’t help wanting to stand out every once and a while, even if it’s all in my head. Let’s be honest, BU students likely don’t even give me a passing glance, but it’s nice to think they do. I get to coast by as an anonymous BU student while still feeling as if my presence means something more. Maybe that makes me self centered, but I think deep down we all want to be noticed for our favorite things about ourselves.

To Shape and Embrace

By Arshia NairNew York Fashion Week. One of the most iconic, anticipated, and exclusive projects in the world of fashion.

Unless you’re a buyer, you work in the press, or are a celebrity, there is a slim chance you’ll be able to snag a seat in front of the runway. The artworks that pass through this bi-annual catwalk are created and curated by the top designers in the industry.

Originally founded by Eleanor Lambert in 1943, with the intention to showcase American fashion during wartime when French fashion was inaccessible, New York Fashion Week (NYFW) has transformed into a massive collaboration that, according to Forbes, brings in $900 million in annual revenue to the city. While over the decades NYFW has progressed economically, it has been slower to progress in thought, specifically in terms of diversity and inclusion. With time, though, NYFW is making strives towards creating a larger space for the fashion inventions and innovations brought forth by designers of color. Hema Patel and Shirpa Sharma, two successful designers, decided that the moment had arrived for New York Fashion Week to serve as representation and allow designers of color to receive a spotlight on their works. In September of 2022, NYFW witnessed the emergence of a new representative initiative: South Asian New York Fashion Week (SANYFW).

Made up of the countries India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Afghanistan, and Nepal, South Asia is a region jam-packed with cultural diversity, like no other. This is a region with more than 650 individual languages. For reference, there are around 7,000 living languages in the world, so that means South Asia alone hosts 10% of the world’s living languages. When it comes to traditional clothing and fashion, the most common styles involve the draping or wrapping of garments. Examples of this include the sari, or saree, with a choli, the salwar kameez, and the lengha. These forms of South Asian garments have a deep history, the sari being the most enduring of all. The Sanskrit word “sari,” translates to “strip of cloth” and there are approximately 30 versions of the sari across South Asia, with over a hundred different ways to drape it. This term is first mentioned in the book of Hindu hymns, Rig Veda, from back in 3000 BC. The design of the sari was created to fit the hot climate of the South Asian region and allow for the wearer to move comfortably while abiding by the modest dress style of both Hindu and Islamic culture. To this day, the sari is a traditional staple in the wardrobes of Nepal, Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan.

The SANYFW initiative has allowed for many talented designers to step into the limelight and showcase their works, many of which are connected to their South Asian roots in some way or another. RAAS, a Chicago-based Desi brand whose motto is “where tradition meets contemporary elegance,” is one transformative brand that took to the runway at SANYFW. An aspect of RAAS’ mission is to create pieces that exemplify the “colors, royalty, tenderness, emotions, nature, and above all, creation.” Like RAAS, there are a variety of South Asian designers around the globe, who work towards such creations, and SANYFW has given them a notable stage to present that on. While the existence of such brands within the western world is a monumental success for people of color, bringing them onto a runway like NYFW takes these brands to another level. When a brand is given the opportunity to be a part of NYFW, there is an automatic credibility established amongst the members of the fashion industry and those who observe NYFW from the outskirts of the industry. The power and respectability that comes with a brand establishing itself through NYFW, is why it is so important for South Asian designers to have their own stage.

However, there should be more to SANYFW than designers of color having the opportunity to demonstrate their skills. With the rise of this representation, this should have meant that there would also be a greater scope for South Asian models to walk because those wearing the clothing play just as much a role in representation as the designers do. Divya Raj, a dancer and model based out of New York City, walked the 2023 South Asian runway for Akriti by Shakun. “As a model I thought it was really cool because it gave an opportunity for South Asian models like me to walk a runway for such an esteemed organization and such an esteemed event,” Raj explained during a sitting. Further in conversation, Raj said “the push for diversity, it’s starting, but I feel like we have a really long way to go. Yes, there were South Asian models that were cast but I think there could have been more.” Raj elaborated that, in her opinion, this issue lies within the lack of size inclusivity and the fact that much of high fashion apparel is not stitched in consideration of a variety of shapes and sizes. For South Asian models, height can be the dominant hindering factor as the average height for a South Asian woman is approximately 5 ’4, whereas the ideal model’s height on the high fashion runway is between 5 ’7 and 5 ‘9. So, as this wave of racial diversity takes over the world of design, the same should be applied to those who present those garments. This underwhelming representation on the runway cannot be blamed on a lack of talent as there are plenty of South Asian creatives in the modeling circuit. Raj confirmed, “I know so many South Asian models [in New York] and they were not cast in the show.”

It is a frustrating thing to know the work you’re seeing before you is made by someone who looks like you, but you can’t see it worn on someone who looks like you. This initiative has created the space for something amazing, however it is crucial that we do not allow this representation to be hollow. There should be space and opportunity provided for all kinds of South Asian creatives, not just the designers, because there is so much creative work that goes into putting on a show at such an important scale. SANYFW should show South Asians that they can be not only designers, but models, make-up artists, set designers, and more. It should be like a cultural explosion, inside and out. While South Asian New York Fashion Week has been a powerful display of South Asian culture and genius, it is also critical to continue to call out the industry for its shortcomings, so that we can see truer representations as the years go on.

The Way It Devoured Me:

How My Journey Back to Dance Was A Journey Back to My Body

By Paige ShepherdWondering if everyone’s eyes are on me, Knowing that they’re probably not But I still can’t seem to get over it. I feel like I have something to prove here, I know I don’t, I know it’s fine, But it doesn’t feel like it.

There is something so unique about danceyour mind stops running at a million miles an hour and your body takes over, and you become something almost above human for just a few minutes. But it takes an incredible amount of time to get there. Growing up as a serious dancer is complicated. It has ups and downs - one moment you’re soaring through the air, feeling so beautiful under the stage lights and loving the way your body moves. The next, someone makes an offhand comment and it all comes crashing down. Weight and body image were topics that no one liked to talk about directly at the studio, but we all knew, despite the fact that most of us were younger than 17, that professional ballet companies expected dancers under a certain weight.

For the older girls, this looked like teachers making comments like, “You’re going to need to lose a little weight before audition season.”

For us younger dancers, it looked like, “Hold yourself up, I can see your lunch,” or reminding us that salads were better choices than fast food. And for an 11-year-old, those kinds of words get to you after a while. As a kid, I spent about 25 hours in a studio a week.

It was hard, but because I was so dedicated, it always felt so worth it. Our standard uniform, a black leotard and pink tights, was what I lived in, and for a kid with body image issues, that can be difficult - it can feel so very exposing. We felt lucky if teachers let us wear shorts or skirts in classes. I didn’t spend a lot of time outside of class wearing normal clothes, so I had absolutely no idea how to dress myself outside of ballet.

I’m young and I’m scared.

I used to hate the word impressionable,

But I didn’t realize it was so useful until I was older.

There are some moments when you realize,

You just didn’t know as much back then,

But you can’t blame yourself for not knowing.

You didn’t know the way you looked wasn’t your fault,

That the way you were wasn’t your fault,

That while almost everything is possible,

The universe has its limits.

That it’s okay to feel the way you feel,

That you don’t always have to change

Just because someone told you to.

I think we’d all like to go back and tell ourselves:

You’re okay the way you are.

Dance was so beautiful, so freeing, but when I turned 14, I knew that it was time to give it up. I felt that I wasn’t meant to be a professional dancer. While I loved dance, I had so many other interests that I wanted to explore. When I knew I wanted to do other things with my life, all the pain and all the hours didn’t seem as worth it anymore. I wanted to go to a normal high school with normal kids. This wasn’t easy for someone who spent all her time outside of school at the studio. I wore a uniform at school and then a leotard and tights until I went to sleep at night.

Figuring out who I was outside of the studio, the life that I’d known, was not easy. Getting dressed every day was a battle because I had no idea how to begin navigating it. It’s a well-known fact that high school is a hellscape, and for someone who’d never had to learn to dress, it was a shock. I learned to like jeans like everyone else and learned to wear sweaters and dresses and makeup because that was what everyone else did. For some reason, it never really felt like me.

Wandering, but not lost.

Confused, but not falling apart. It is hard when the world isn’t wide enough for you to know that You’re doing it okay.

Take another picture, Make another friend, Laugh another laugh, Make another mistake, Because it’s okay to muddle through. No one’s got it all figured out, So live a little, And if it’s messy it’s fine, It’ll be okay some other time.

But then high school was over, and I was a different person. I moved halfway across the country to pursue art, and I started to figure out that I really missed the way dance made me feel. Despite all of the trials it put me through, it brought me joy - it was a part of me, part of who I am. I missed the feeling of being under the lights, using my body to tell a story, the beautiful shapes I could create, and the feelings that I could feel through my choreography. So I tried again. Just a little, dipping my toe in two hours a week. And it was hard. Really hard. It took time to work through all the insecurities that I’d learned to associate with danceabout my body, about the way I looked, about my weight and the way I dressed in class, about what I wanted to cover up - but then, all of a sudden, all of that disappeared, and I would lose myself in the movement and the music.

I finally learned to forget that it mattered that people were watching, and learned that this was for me. I guess you could call that growing up. It’s taken me a couple of years, but now when I dance, I feel good. I feel powerful. I feel in control, confident in my body, and I let my mind go and just move. But now came a new challenge: what do I do about my clothes? How do I find something that really feels like me, not like I’m just doing a bad imitation of what everyone else is? How was I going to feel wearing a sports bra in front of 50 people? Wearing spandex shorts in a filled theater?

City

Photographed by Lilli Drescher

Design by Molly DeHaven

Josephine Fontana

Makeup by Lilli Drescher

Modeled by Anushka Dixit

Alexa Latzman

Bianca Todini

Stories for Myself by Liz Gomez

They met in college through a mutual friend planning a blind date.

At first, she was hesitant; blind dates were a reality in movies, not in her actual life. The rom-coms she watched, wistfully but critically, as a teenager seemed a viable and appropriate environment for them. She was just a regular, boring college student, not a secret assassin or a beautiful milkmaid.

Furthermore, how could she fully trust a stranger? A man, or more so a boy, who her friend has mentioned a few times. He could easily have secrets, bad secrets, secrets that ex-girlfriends would reveal to her at a party with worry stained on their lips.

She loved her friend, but she thought him to be too trusting, easily misled by false promises and hollow smiles. He was excited, however; it had been his dream to be a successful matchmaker.

Her love for him, or more accurately his constant pestering, won in the end, and she found herself on a cool October evening sitting on a bench in the Boston Commons, studying the statues of ducks frozen before her. She was worried—not from the looming date, but from the lack of anxiety she felt about meeting her friend’s friend’s friend. More than anything, she looked forward to the walk back to her apartment in the North End, right across the street from Bova’s Bakery, where she’d surely grab an éclair and large hot chocolate to drown her embarrassment in.

While imagining the warmth of her bed and the company of her ten-year-old cat, she saw him. He stepped into the light of the lamppost, his smile obscured by a frayed, knitted scarf wrapped tightly across his neck and mouth.

Dark and hazy, it crashed through her chest and clambered up to her brain, breaking every stone that was delicately placed around her vulnerability. She thought it was unlikely—hell, impossible—that anyone could feel this. An emotion only written in books or shown in movies. A gilded emotion so many yearn for: true love.

It was his idea to move in together, which made sense since his apartment was about double the size of hers, and it stood just beside the Commons—anytime she looked out the kitchen window, she could always find the lamppost where she first saw him in that hazy yellow light. After the long, terrible move from North End, when her cat refused to leave the unfurnished bedroom, hissing at them with its tail straight and back hairs spiked, when she almost forgot to pack her one and only phone charger and bounded up her apartment building’s steps as he waited patiently in a rented minivan, with a line of cars behind him honking and swerving and flashing their lights, they decided a picnic in the Commons was a well-deserved award.

At least, that’s what I thought when I saw a couple sitting on a knitted blanket right next to the pond, a large charcuterie board and a bottle of red wine sitting at their feet, and a golden

retriever racing around them, a blurred flash of yellow hair. As I walked past them, their dog stopped me by leaning on my left leg, demanding attention with its puppy eyes and sopping tongue. The couple apologized in unison, and I just laughed—I later decided the woman’s then eleven-year-old cat died peacefully in its sleep a few months before, and the man adopted a golden retriever just a few days later as an outlet for her grief and his life-long dream of owning a dog.

I can’t recall the first time I created a story of a stranger for my amusement—some latent memory tells me it was when I first went to Disneyland and had to find an easy activity to keep me from succumbing to boredom while waiting in line for It’s a Small World, but I can’t guarantee the validity of this. All I know is that from that time on, when out in public and away from a book or my phone, people-watching was the way I passed my time.

Some of my favorite childhood memories were of me convincing myself that the unbelievable stories of strangers were true. Once, at our local diner, I believed the waitress who took my order—she was beautiful, wearing bright red lipstick and a gold septum piercing that sparkled in the morning light—was secretly a princess who escaped from her evil stepmother and found an inconspicuous job to pay her taxes. I’d just recently learned what those were and saw this as the perfect opportunity to implement my knowledge of the adult world. As my family and I left the diner, I turned to her and did my best curtsy. She laughed and curtseyed back, which fully convinced me that my story was true.That night I prayed that she would earn enough money to pay her taxes and buy a home and maybe find her Prince Charming.

As I grew older and more awkward, these stories grew silly and embarrassing. Mature people don’t make up stories about others; that’s just weird and ridiculous. Mature people, because I really did believe I was one, worked minimally paid jobs, did their taxes, and went on silence-filled dates. Therefore, people-watching became a humiliating secret of mine, one that I did my best to repress and forget. That is until I started college in Boston.

Maybe it’s because I was in a new environment. Maybe it’s because I encountered new people, cultures, and traditions. Maybe it’s because I gained some actual maturity. Regardless of the cause, the Boston Commons became my sanctuary, and new faces shone beautifully everywhere I walked. No matter how hard I tried—staring at the cracks swimming across the asphalt path or at the squirrels fighting over a Tatte croissant—the stories came flooding in, irrevocable and unavoidable.

I couldn’t help myself. The woman feeding ripped-up pieces of bread to squirrels had to be from a rural town where she owned a farm, who moved to Boston to be near her sister and found herself missing the constant companionship of animals. Everyone had to have a story, a story that contained my hopes and dreams.

The couple’s story was a projection of my dream of undeniable love. The waitress’s story was an opportunity to imagine myself as a secret princess. The woman feeding the squirrels experienced my desire to live in a rural town, on a farm filled with fluffy cows, huge apple trees, and gardens filled with tomatoes.

I process the world through stories—I process myself through stories. My time in Boston revealed this to me. I can only understand my need for a loving, steadfast relationship by painting a portrait of it through the couple that I saw only once.

Others use journaling, therapy, or self-help books to grasp their nuanced thoughts, desires, and secrets. I use Boston and the people who exist in its chaotic beauty to understand myself. Maybe that’s weird. Maybe that’s awkward. Maybe that’s immature. But it works for me, and I find it helpful to see the endless possibilities sparkle in others because eventually I see them glimmer in me.

I Am Finally My Mother’s Daughter

by Gandharvika Gopal

by Gandharvika Gopal

My mother once told me being able to cook is one of the most powerful things a person can know. And not because a woman must know how to cook to be powerful, or must be capable of domesticity to be valued. My mother believes cooking is life giving, the ability to heal and sustain the body and soul… it’s like magic. And the way she cooks, it really is like magic.

I was like my mother in many ways growing up. People said we looked alike, that I had the same thick hair and dark eyes. She’d pull me close to her, our cheeks pressed together like a mirror for greater scrutiny, and people would marvel at the same slanted eyebrows and crooked lips. I look even more like her now. My dad would say we are fiery in the same way—hot to the touch and quick to anger. This hasn’t changed. We love the same books, harcovers she saved with notes written in my dead great grandmother’s cursive on the first blank page. We love the ocean in the same way, like we need it, and there hasn’t been a year of my life we didn’t spend at least a day together by the seaside.

For all our similarities, there was one way I was never compared to my mother: her cooking. She tried to teach me; there are photos of us in matching frilled aprons holding spatulas above our heads. But once the results actually began to hold some weight—after the years of playdough bakes and salt dough cookies—I lost interest. I was an impatient student with very few natural instincts, but with a need to do everything right and on my own. This contradiction between character and practice meant I did very little cooking at all.

My mother grew up cooking. My grandfather is a chef, and his cooking is the reason my mom grew up in so many corners of this country, spending a year or two in each before moving to the next hungry place. She worked in my grandparent’s restaurant when she was younger than I am now, pregnant with me, in Greensboro, North Carolina. She likes to tell me about all the smells that triggered her morning sickness the summer before I was born, how she had to run out of that greasestained kitchen day after day. She couldn’t eat any of their food by her third trimester. It’s now a vegetarian Vietnamese and Thai restaurant, and I spent many birthdays ordering fried tofu and thick brown noodles from that kitchen.

I grew up around food, and people who loved it, but I didn’t grow up cooking. Instead of my mother, I was compared to my grandmother when it came to the kitchen. She’s been married to a chef for decades, so she possesses neither the need nor the impulse to cook. On Thanksgiving, she makes the cranberry sauce, and when she doesn’t I do. As my family points out, “the cooking gene” skips from boy to girl and girl to boy. My grandfather, my mother, and now my brother. He is the natural cook between us, and a lover of food in many ways. As kids, we agreed he would be the cook and I, the baker. This was the compromise to a frequent bicker between children too close in age not to compare their every move. He was better at cooking than I was, but unable to accept defeat I gave myself another title, one I rarely lived up to and less often enjoyed.

A decade later, I now live in an apartment in South Boston with a few pots and pans and a cupboard packed with spices. I spent every day this summer chopping vegetables and boiling rice, making sauces and salads and anything to be covered in goat cheese. I amazed my girlfriend with the kind of cooking that seemed to her like magic—my mother’s magic. She couldn’t understand how I knew what to add when, or if I’d need her to pick a leaf of basil from the yellow pot that sits on our bedroom windowsill. I told her I’m not sure how I know these things either.

I amazed my girlfriend with the kind of cooking that seemed to her like magic—my mother’s magic.

I amazed my girlfriend with the kind of cooking that seemed to her like magic—my mother’s magic.