ATLAS

Epiphany in literature refers to an epic visionary moment when a character has a sudden insight or realization that alters their perception or understanding of the world around them. It completely changesthe way they operate in the universe from that point on.

This is a popular motif in television, film, and literature. We see it everywhere, but it’s easy to forget that this is not just a phenomeon that exists outside of our daily lives.

It can also be as simple as a thought or memory that crosses the mind as blissfully as a paper airplane cutting accross a bright blue sky. Epiphanies happen on the daily. They’ve happened to us, and we’re certain that they’ve happened to you too.

Welcome to the Epiphany Issue. We hope that you take away from this issue what we learned from creating it. Specifically, that you too, are capable of being something bigger than yourself, something much larger than life.

Spring is upon us, and yet another semester has passed as life slowly creeps back to whatever we remember “normal” to be. When Erin and I took on our new roles of leadership with Atlas at the start of the semester, we thought about what spring means to us, and to our community. It is a time of freshness and light, new perspectives, a breath of fresh air. It is a time of change.

And so came Epiphany.

Epiphanies are moments of almost divine or spiritual inspiration. They are the sudden realization of an idea that has been ruminating deep within our subconscious. When I visualize an epiphany, I see the city of Boston bursting, overnight, into blooms of pink and white, magnolia and cherry blossoms. Epiphanies bring us new perspectives and often have a profound impact on our lives. This time in our life, the breath between childhood and adulthood that is college, is filled with these epiphanies and transformations. Every day is a new discovery about ourselves, our life, and our place in the world. I hope that you carry this energy of discovery, growth, and possibility with you as you read this issue.

I am so grateful for the incredibly talented Atlas staff, my other half, Erin, and everyone else involved in making this semester’s issue possible. And thank you to everyone who welcomed me into this role with such kindness, love, and support. This magazine has always held a dear place in my heart and in the Emerson community, and I am honored to be presenting you with our newest issue, Epiphany.

With love,

Ellye Sevier Editor-in-ChiefHello friends!

I used to think that in order to have an epiphany, I needed to watch the sun rise with a cup of hot green tea in my hands. I thought that I especially needed to be in a state of calmness, perhaps even serenity. But even at my busiest and most chaotic, I’ve found myself having epiphanies here and there.

As I am writing this, I happen to be watching the sun bring light over the skyscrapers this morning, and I am so grateful.

But just a few days ago, I was sprinting to the T, late for work, with an old fashioned donut in one hand and my Charlie Card at the ready in the other. Still, I was grateful.

I suppose what I’m trying to say is, not one epiphany is identical. Anyone could say that, it’s not profound in the slightest. But what I hope is profound, is the incredible art that was created for this issue of Atlas in order to portray a powerful sense of individual thoughts, dreams, memories, and beyond. I am so grateful and proud to be a part of such a wonderful and talented group of people.

To Ellye, you are so wonderful, I can’t wait to do this all over again. To the Atlas Community, I am just so blown away. I am so proud to be on this team. You all have always been a home.

Thank you for absolutely everything.

Hugs,

Erin Norton Creative Director The Creative DirectorEditor in Chief

Creative Director

Managine Editor

Photography Director

Illustration Director

Beauty Director

Online Director

Style Editor

City Editor

Arts Editor

Wellness Editor

Globe Editor

Head Copyeditors

Social Media Director

Academic Advisor

Ellye Sevier

Erin Norton

Brynn O’Connor

Sophia Roberts

Sofia Goldfarb

Angelee Gonzalez

Angelee Gonzalez

Ellye Sevier

Annalisa Hansford

Kathleen Nolan

Elisa Davidson

Abigail Ross

Christine Chin & Emma Shacochis

Rebecca Calvar

Kyanna Sutton

Style Writers

Daphne Bryant

Elisa Davidson

Lyanna Rose

Lily Suckow Ziemer

City Writers

Christopher Fong Chew

Morgan Gaffney

Dharvi Gopal

Erin Norton

Arts Writers

Claire Fairtlough

Christina Horacio

Catherine Kubick

Kate Rispoli

Eden Unger

Wellness Writers

Fernanda Cantu

Sisel Gelman

Hannah Hillis

Habeebh Sylla

Globe Writers

Sydney Flaherty

Liz Gomez

Annalisa Hansford

Arushi Jacob

Copyeditors

Ellen Hatfield

Ocean Muir

Minh-Thu (Meggie) Phan

Photographers

Emma Cahill

Ali Lin

Liz Farias

Lily Farr

Sophia Roberts

Visual Artists

Dharvi Gopal

Julia Lippman

Abigail Nash

Designers

Emma Albright

Rebecca Calvar

Lily Farr

Abigail Nash

Erin Norton

Sophia Roberts

Style & Prodution

Renee Mundra

Jemma Sanderson

Beauty

Angy Beare

Angelee Gonzalez

Izabella Pitaniello

Social Media & Marketing

Kelly Chan

Julieta Crissien

Annie Douma

Ellisha Jia

Nicole Levine

Xi Liang

Renee Mundra

Grace Murphy

Paulina Poteet

Ryley Tanner

Cindy Wang

Danielle Webb

Tian Tian Xia

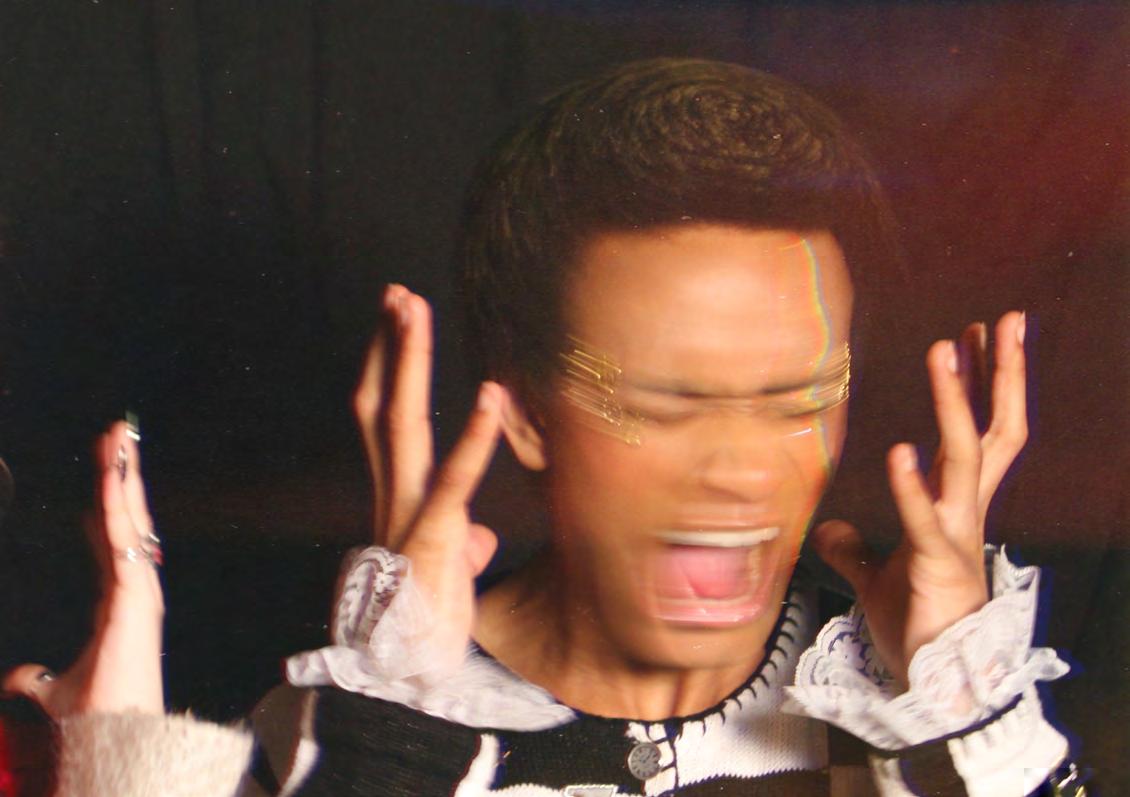

Photographed by Liz Farias

Design by Erin Norton

Makeup by Angelee Gonzalez and Izabella Pitaniello

Styled by Liz Farias

Assisted by Breazy Rowlands

Modeled by Jonah Hodari Bianca Weston

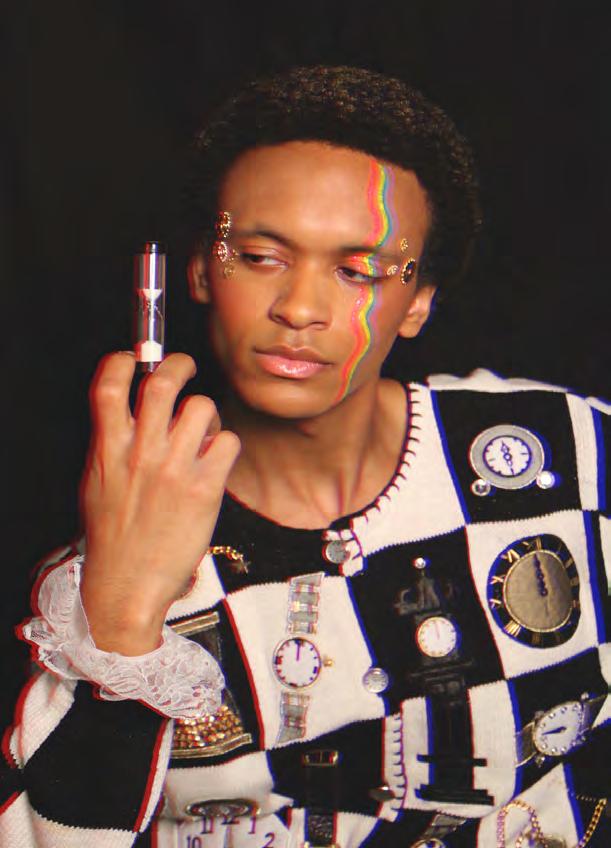

Photographed by Liz Farias

Design by Erin Norton

Makeup by Angelee Gonzalez and Izabella Pitaniello

Styled by Liz Farias

Assisted by Breazy Rowlands

Modeled by Jonah Hodari Bianca Weston

Ibought my first crop top in eighth grade. This may seem like a trivial detail, but I’ll never forget it; everything I’ve worn since connects back to that single shirt.

It was spring break and I was in an H&M with my parents. My dad had wandered off while my mom remained to compliment or reject the clothes we browsed. Then I saw it: a white and navy striped shirt — reminiscent of what an oldtimey sailor might wear — with flowers embroidered on the ends of the short sleeves. Most notably, however, it was cropped. Ordinarily, I’d look longingly at a shirt like this, then move on, thinking, I can’t wear something like that. I’ve loved clothes for as long as I can remember, and this shirt appealed completely to my style at the time. I don’t know what changed that day, but something overtook my body. I grabbed the shirt and decided to try it on.

My mom was excited (she loves striped shirts) and gave me a short, black, A-line skirt to try on with it. Although she tends toward the side of minimalist, conservative clothing herself, she’s always encouraged me to find my own style. She sewed my baby clothes, hemmed dresses I thrifted, knit the same six-foot scarf each time I lost it, and taught me how to sew. I’m always sending her pictures of clothes, and asking if she can make things I’ve seen online. Even when she’s appalled at how revealing my clothes are, she still pushes me forward to craft my own style, which I am forever grateful for.

All my life I’ve wanted to control how people see my body. Ever since I was bullied in fourth grade for the way I looked, I have had rules about what I wear. Before this special crop top, they were incredibly strict. Shirts had to be long enough to cover my butt, sports bras were a must in order to cover my breasts, and zip-up hoodies (which I wore even in summer) were essential to hide my hips. I hid as much as possible in an attempt to keep people from ever seeing my body again. By eighth grade, “no crop tops” was the most important rule.

Looking in the mirror on that fateful, spring day, I noticed the ways the outfit followed my rules. The sleeves were loose and went to my elbows, hiding the bumps on my upper arms. The skirt was loose enough to erase my hip dips. And, despite being cropped, the shirt didn’t reveal much of my midriff. To many, this would be considered a failure as an attempt to get out of one’s comfort zone. But to me, it was revolutionary. The moment I slipped on that shirt, I became someone else. I had never worn anything like this. I walked out of the dressing room, proud to show my mom. It was a little uncomfortable, but I was happy. For the first time, I admired something on myself just as much as I admired it on the hanger.

“I love it!” my mom exclaimed. I couldn’t hide my smile and we bought the outfit. I didn’t wear it at first; it felt somewhat sacred. I wouldn’t touch it for fear of the magic disappearing. But, finally, I did wear it on Easter Sunday. It was the perfect outfit for spring and it felt like I was entering a new world the minute I walked out of the house.

If 14-year-old Lily could see me now, she’d be shocked. At 19, I wear things that expose most of the features I used to want to hide. I barely wear shirts that aren’t cropped, my skirts and dresses are much tighter, and I wear an obscene amount of see-through shirts.

Since my crop top revelation, I have started taking more risks by trying clothes I’d only ever admired from afar. It’s a process of trial and error. Sometimes I’ll try something new only to hate the way it accentuates my insecurities. But over time, I’ve grown to look past that and appreciate the way I look and dress just as much as I appreciate fashion influencers I see on TikTok.

I now feel comfortable actually choosing my clothes. I’ve grown a sense of control over the negative parts of my brain that tell me I shouldn’t dress like I do — the parts that tell me bad things about my body. My style is now a physical manifestation of my rebellion against those insecurities. To be honest, I would never choose that crop top

for myself today; it’s definitely no longer my style. Yet it still sits in my closet, and I know I’ll never give it away. No matter how insecure or elated I feel after putting on an outfit, it will never match the intensity of emotions I felt in H&M that day.

Getting dressed in the morning is now one of the most important and exciting moments in my day. I love creating something uniquely me out of lots of different pieces. I’m most happy leaving my dorm room wearing tons of jewelry, platform shoes, and worrying that it’s too cold out for the skirt I’m wearing.

Maybe it sounds silly that something as simple as clothing has such importance to me, but I wouldn’t be myself without my style autonomy. If I never took the leap of wearing that shirt, I might have never gotten to this point of freedom and self-confidence. I would still be appreciating clothing from afar but not participating. One shirt changed the way I look at myself, and I am so much happier because of it.

I love creating something uniquely me out of lots of different pieces.

Fashion is integral to the craft ing of a story in film. Wheth er it be the expression of a character’s inner turmoil through a closet of muted grays, or simply the color green being used to denote envy or greed, costume design is a visual language storytellers use to communicate with their audiences.

While fashion and costume design play a vital role in the world of cin ema, films also have a large influ ence on the fashion world. Charac ters’ wardrobes in Andrew Fleming’s witch-horror movie The Craft de fined a wave of alternative fashion in the late ‘90s. TheVirginSuicides a film made nearly 25 years ago now, has continued to serve as inspiration for collections from major names in fashion today. The most sumptuous styling in film makes use of fash ion to further the story, enhancing a movie’s lasting power. When design ers employ such fashion, they help create something bigger. It is then that an individual piece or a char acter’s wardrobe is deemed timeless or iconic, thus immortalizing the fictitious worlds they are home to.

Piecing together such a wardrobe to reflect a character’s complex interior world is no easy feat. It requires the work of a historian as much as that of a storyteller or designer. The characters’ wardrobes must be situated within their exact social and historical moments, all while evoking the desired emotional response. Such work was notably done by designer Deborah Everton on The Craft. The movie follows a girl with magic powers as she transfers to a high school in Los Angeles, where she meets three wannabe witches. The film, exploring themes of depression and self-acceptance (and witchcraft, of course), was a hit with “alternative” girls worldwide. The bulk of the film’s lasting appeal, though, comes from Everton’s careful styling of the girls.

Despite the main characters spending most of the film in uniforms, Everton worked within these parameters to curate timeless costumes that would accentuate the varying identities of the four girls. The magic of Everton’s design is found in those minute details that bring to life both the four main girls and the world around them. For Nancy, played by Fairuza Balk, clothing became her armor. Nancy’s iconic PVC coat and spiky, black dog collar were noticeable staples of her closet throughout the film — her character adorned by accessories that mirror how she engages with and experiences the world as a misfit teenage witch.

In her designs, Everton sought authenticity by sourcing clothing that would’ve been accessible to other real-life teenagers. In doing so, she created a series of looks that conveyed the varying emotions of teenage girls who’ve been rejected by society and, in turn, reject it right back through their fashion and attitudes. This notion was so powerful that it resonated with “misfits” around the world, inspiring them to do the same and subsequently shaping a wave of alternative fashion to come.

The most sumptuous styling in film makes use of fashion to further the story, enhancing a movie’s lasting power.

In Sofia Coppola’s TheVirginSuicides , the costume design and styling enhance the film’s dreamlike quality. Following the story of the short yet mystifying lives of the conservative and reclusive Lisbon sisters, the film centers on the repression of female sexuality and the traditional place of women in society. Taking a unique approach to the usually overtly retro style of the 1970s, designer Nancy Steiner centered the girls’ wardrobes around real photographs of everyday people of the ‘60s and ‘70s. Steiner also took into account conversations she and Coppola had about each of the girls’ individual personalities and character traits. In her styling, Steiner externalized the inner turmoil the girls’ experience by outfitting them in demure garments. A dazzling portrayal of ‘70s girlhood, the Lisbon girls’ wardrobes are built upon the quiet fashion of the time period and the suffocating fabric of innocence.

Throughout the film, the four sisters can be seen adorned in dainty lace dresses, barely-there floral patterns, and traditional-yet-ever-boxy school uniforms. The most outspoken pieces in the film are the four “identical sacks” (as the narrator calls them) that the girls wear to the homecoming dance. These “sacks” are a collection of vintage floor-length dresses, to which their mother adds additional fabric to make them even less revealing. With babydoll necklines and puff sleeves, these long, pale dresses speak for themselves — mirroring the repression they face in their day-to-day lives for simply existing as young girls.

This notion is furthered by the styling of the girls’ counterpart, Trip Fontaine. The burgundy velvet suit he wears to homecoming as Lux’s date entirely juxtaposes the lifeless vintage gown her mother placed her in. He stands out next to her, reminding the audience of the striking contrast between them. Trip’s character is free of the expectations and pressures that are placed upon the Lisbon girls, and his dress and attitude reflect such freedoms.

The resounding impact of such careful and intricate costume design on these two films is evident. In an interview with Dazed magazine, Deborah Everton shared her experience of going to a press junket for The Craft in Paris. She describes being shocked to see young girls going to the theater dressed up as the main characters that she had styled. The impact of her design work on the film was felt by audiences globally and had manifested itself into something tangible. Young Parisian girls dressing up like the characters showed how her work had been brought to life.

As for Coppola’s TheVirginSuicides , the 1999 film is still relevant today through its cult following and stellar costume design. Just two years ago, the film was given new life in the fashion world by Marc Jacobs’ sub-brand Heaven and their Fall/Winter collection, which paid homage to the film. The collection takes the film’s dreamy, ephemeral nature and spotlights it with iconic stills of star Kirsten Dunst’s face screen-printed on midi skirts and half-mesh long sleeves. The evanescence of the film speaks for itself through the clothing, and the collection brings a new understanding of what it means to recognize a timeless work of styling by bringing it into the world of fashion.

The relationship that exists between film and fashion is a symbiotic one. Costume design often acts as a sweetening agent that brings to life the characters and worlds that make up a film. Cinema, in turn, broadcasts the fashion of these narratives to their audiences, throttling forward the fashion of time periods long forgotten and immortalizing certain styles and pieces forever, shaping waves of fashion to come. As observed through the design work of The Craft and The Virgin Suicides , it is meticulous care towards such work that fosters the creation of wardrobes that can act as secondary storytellers within a film. Only then can such media reach beyond the bounds of the silver screen and impact the world of fashion around it.

What does it mean to “dress like a gay person”? How does one even go about doing so? Can you even tell if someone is queer by the way they dress?

Ever since I came out, I’ve asked myself these questions and many more like them. Before, I had been living as a straight girl, and so, naturally, I supposed I had presented as one too. After I came out, I secretly longed to fit into the archetypes that exist in the LGBTQIA+ community in some way so that I would be recognizable as someone who is queer. I’m not alone, and “dressing queer” isn’t a foreign concept. The idea of signaling through style has been around for a while.

There is an extensive queer history surrounding the cultural communication of sexuality in a safe and covert way. Much of what is considered stereotypical queer fashion today was originally used by people in the community to signal their sexual orientation to others during times when saying it aloud might have been dangerous or not socially accepted. Sometimes this was done as an act of rebellion against frameworks that pushed a cis and heteronormative fashion sense, and other times it was done to safely and subtly let others know, “I am one of you.”

Certain style codes and symbols conveyed certain things. For example, in the 1930s, global staples in lesbian coding were tuxedos and short hairstyles. Even now, in the United States there are still specific queer symbols that are used to “identify” a queer person. Many have evolved into even more niches to address a wide range of gender identities and sexualties. Chains and snapbacks are often associated with more masc-presenting folks, the artist girl in red is associated with sapphic listeners, and rainbows are a common way to express queerness for all.

This might all seem arbitrary to an outsider, hidden to the straight eye, but for people inside the community these can be genuine tells. Sometimes I’ll be walking down the street and I’ll spot a super fly girl fitted out in a Carhartt beanie, flannel and cuffed jeans. Even though it’s mostly unconscious (and sometimes inaccurate), I’ll absorb those subtle cues and clock that person as queer. In some ways, embracing these archetypes can be liberating for queer people, and allowing tropes to shape your identity as you go can be exciting.

“I don’t mind [the tropes] honestly,” says stylish freshman Communications Studies major Averie Morren, who loves both traditionally masculine and feminine clothing. “I do find that gay people are more creative with their styles than anybody else. So if there’s one thing I could ask for, it’s that as I continue to grow my gay identity that my style just keeps evolving.”

At the same time, these stereotypes can also feel othering. Junior Marketing Communications major Nathan Manaker describes his style as “rooted in nostalgia.” His rule of thumb is: “If your grandma would wear it, so would I.”

“Coming out as gay helped me feel safer in the way that I wanted to dress,” Manaker says, “but it also started to make me feel like a stereotype. My sexuality, something that was intimate and special to me, was a stereotype.” He reflects on the trope, often found in movies, where a group of girls goes on a shopping trip with their fashionable gay best friend.

“I wonder if, in a way, I was offsetting [tropes like that] by assuming this more reserved style with muted tones. I was more comfortable wearing bright colors when it wasn’t part of my ‘gay-ness,’” he says.

Many people in the LGBTQIA+ community feel an intense push-back against labels entirely, rebelling against society’s framework for queer individuals. Sophomore Business of Creative Enterprises (BCE) major Anna Swisher — a lover of streetwear fashion, L.A. thrifting, and a self-proclaimed “sneaker girl” — expresses her dislike of labels and the assumptions that come with them. “When it comes to style I get a lot of ‘Oh! I’d never guess you were gay, you look really straight,’ and so I think a big part for me is just honestly dressing the way that I want to dress and showing people that it doesn’t matter how you dress. I’ve learned what looks good with my hair color, my eyes, my skin tone, and I love that,” she says.

Junior BCE major Annabel Kavetas, who describes her fashion as a mixed bag with everything from Lululemon athleisure to cottagecore hyperfemininity, has a nuanced and complex relationship with style. Kavetas sets out her rules for her clothes: “[something that] flatters my body, honors my queerness, feels authentic.” But she admits, “All of those boxes are hard to check at the same time.”

There are also people who don’t necessarily identify with the gender binary, which for so long has been a ‘distinguishable’ way to sort queer-identifying individuals. Eliyaju Levinson, who uses they/he pronouns and identifies as gender-queer, likes existing out of the stereotypical box. “In regards to clothing style, my personal style is very fluid and can range anywhere from ‘little toddler boy’ to ‘raging-hyper-fem-lesbian,’” says Levinson. At Emerson, they feel the freedom to experiment with different aesthetics and vibes, and to display it however they choose.

This is a common thread among students: a respect and appreciation for Emerson College’s fashion culture, where the streets are our runway and we are free to experiment with style and take risks. For students like Kavetas and Levinson, Emerson has provided a safe space for queer people and their style, especially. For me, I first felt truly safe to don my six-inch Demonia 311s and miniskirts the second I stepped foot on Boston’s campus. Surrounded by people who genuinely wear what they want to, I feel motivated and inspired daily. Kavetas furthers this thought, saying, “No one’s apologizing for what they’re wearing. If people are wearing something they’re wearing it. They’re wearing the fuck out of it.”

Style is just as fluid as sexuality, and if you are a queer person your fashion is queer, period. The clothes aren’t what make an outfit, it’s the individual that does. There are many different avenues you can go down to express yourself, and style is just one of a million. It’s okay to dispel indicators, and it’s okay to love them with all your heart. There is no one way to dress or present as gay. In the end, it doesn’t matter if you love Doc Martens, color-coordinated suits, wife beaters, flowy vintage garments, rainbow earrings, or if you couldn’t care about fashion at all. Our style is a spectrum, and it’s all beautiful.

Style is just as fluid as sexuality, and if you are a queer person your fashion is queer, period.

One random day in December, I learned of the “pink comeback.” I’d been sitting with some friends, bantering about our childhood favorites: toys, games, colors, etc. I turned to one of them, and said, “You know, I really used to hate pink when I was younger, but it’s one of my favorite colors right now.”

She immediately agreed with me, saying her experience had been very similar. Her story with pink was just as complex, and included a similar intense hate for the color in her childhood. I ended up having the same conversation with five other female friends that same day.

It was obvious to me then: pink is having a resurgence. But why? What is it about this color that made it go from one of the most hated colors in an elementary schooler’s palette to one of the college kids’ favorites?

Elementary school was an idyllic time when boys and girls played together in the courtyard, kicking balls around, swinging on the monkey bars, and chasing each other in games of tag. It was at some point in the middle, however, when things started to change for me. It all started with pink.

For a while, being a kid felt like it had no rules. I loved running around on the field, playing tag with my friends, and beating everyone in races and games of kickball. Being loud and rambunctious was for everyone, and I, for one, was talented at the craft. However, at some point, we started realizing there were differences between us, that some of us were boys and some were girls. Why was being a girl so much less fun than being a boy? All of a sudden, I needed to be polite, wear dresses, and sit quietly. None of the boys received similar treatment and were allowed to continue roughhousing. Coaching our “girlhood” seemed to be a way for the teachers to keep half of the student population under control. At least this way they could focus on the other, more raucous group.

My parents told tales of how a “good little girl” should act, and teachers read us stories about “sweet” girls like Angelina Ballerina and Clementine. And of course, the boys’ behavior changed too. Unconsciously adhering to those societal standards and gender roles, they repeated things like “girls are boring and stupid!” and “they only like glitter and pink!” The dismissal in their tone was clear. All of a sudden, I no longer felt welcome. From this moment on, pink was a trap. It bled into my life, and stained me with girlhood. The color was everything girls “should” be, but I wanted to be so much more. Like for many other girls, pink became a source of anger and resentment for me.

In middle school, in protest of a world that didn’t take me seriously, I dressed in dark blues, bright and alarming reds, and empty blacks and grays. I buried pink, like I buried my toys and my cartoon shows, and I pushed them to the back of my mind.

As I grew up, it drove me crazy that femininity was societally synonymous with weakness. I was fed the false belief that you’ve got to just “toughen up” if you want to be heard. Being “girly” wouldn’t get you seen. Being calm and kind — qualities traditionally associated with femininity — felt as if they held very little power in this world. The color pink, buried in my mind as it was, was now suppressed nearly altogether. It was synonymous with society’s treatment of my identity.

The wall that I had built between femininity and myself began to slowly crumble in college. Gender norms began to muddle, getting mixed and churned as gender identity became less fixed, queer fashion took hold in my community, and different styles included anyone and everyone regardless of identity. As I looked to my social media for fashion inspiration, my Pinterest boards began to fill up with fun, little poofy skirts and fluffy boots, geared towards everyone. Leaving behind the world of “boys rule, girls drool,” femininity has started to take on a more loved and appreciated stand in modern fashion and in my life. Going in the opposite direction from our edgy, e-girl and alternative styles of 2020, people around me started dressing in cropped tops, furs, earmuffs, hats with animal ears, and even put cute charms on their phones. Starting on social media — specifically through Tiktok and Instagram — “softcore,” “aliyahcore,” and other styles emerged, all different and more modern iterations of traditional “femininity.” After feeling dark and gray, it seems the world of fashion wanted to lean in a new, lighter direction.

All of a sudden, being feminine has started to feel good to me again. Being a girl is not just being emotional and cute, but it’s okay to be those things too. Wearing what makes you feel good is okay, even important, and having a nice outfit on does not make you less intelligent or strong. Pink has its own kind of power.

I went home over winter break and looked around my room. I hadn’t been home in a while, and I felt that desire to re-immerse myself in a world that had been completely absent from my mind until now. I started noticing my walls, my decorations, my old clothes. I thought it was funny that throughout the time when pink was my least favorite color, my walls were covered with it.

Now, I like pink. I like hot pink, bright and colorful, demanding you see it, demanding you find it fun and cool. I like bubblegum pink, sweet and gentle, light and fun. I like peach. I like salmon: that mix between pink and orange, reminiscent of bagels with cream cheese and slabs of fresh fish tasting salty on my tongue. I like the pink lip gloss colors my lips, warm and bright. I like pink.

Wearing what makes you feel good is okay, even important, and having a nice outfit on does not make you less intelligent or strong. Pink has its own kind of power.

Photographed by Ali Lin

Design by Rebecca Calvar and Sophia Roberts

Makeup by Nicky Xia and Seeso Chen

Assisted by Mia Liang

Modeled by Anastasia Petridis

Photographed by Ali Lin

Design by Rebecca Calvar and Sophia Roberts

Makeup by Nicky Xia and Seeso Chen

Assisted by Mia Liang

Modeled by Anastasia Petridis

I step out into the cool morning air, feeling the breeze sting my bare face as I make my way over to the Harvard Avenue T station. The sun is just beginning to rise as I join the many commuters waiting at the platform for a Green Line train that will take us downtown. At Harvard Avenue, there are no platform lights, no light-up signs announcing the arrival of the next train. Some of us check our phones, hoping the transit app we downloaded might be correct; some of us just stand, waiting, trusting that something will soon arrive.

Eventually, I see the familiar shape of the Green Line trolley appear in the distance, slowly rolling up to the platform, squealing as it comes to a stop and the double doors creak open. As I board, I am greeted with the familiar wood paneling and the beeps of the fare machines as riders scan their Charlie Cards. Taking a seat by the window, I stare out as the city passes by, just one of the many commuters on this early morning train.

Boston’s public transit system is one of the oldest in the nation, opening the first subway line in America in 1897. Revolutionary for its time, and run by an electric motor, this system meant it was possible to have an entirely underground train as it avoided the soot spewed from the common steam engines at the time.

Over a century (and several changes of leadership) later, the Massachusetts Bay Transit Authority (MBTA) runs just under 70 miles of track and 170 bus lines across the greater Boston area. It carries about 600,000 riders during the weekdays, taking them to and from work, school, doctor’s appointments, and other important errands around the city.

For the many individuals in the city, public transit is their lifeline. It is the only way to get around the city quickly, efficiently, and affordably. However, accessibility to the public transit system is not equal. For those that live near a train or bus line, traveling around the city is relatively convenient. However, for those that have to traverse long distances to ride public transit, or navigate multiple transfers to their destination, it can be a pain.

Stella Gitelman Willoughby, 22, is a current student at Berklee College of Music where she majors in Contemporary Classical Composition. She is a native to the greater Boston Area, growing up just north in Cambridge. Stella uses the bus to commute to and from school, and takes public transit to and from other parts of the city. When asked about growing up in Cambridge, she replied, “Some of my earliest memories with public transportation were going on the MBTA. I don’t even remember where, probably the Cambridge or Boston Public Library.”

She mentioned how her school would take field trips and use public transit to reach places around Boston and Cambridge. “I think that it helped me be able to learn my city better,” she adds.

As a college student, Stella transits between Berklee and Tufts, where she has cross-registered in the past and still frequently visits to work in the library or visit professors and friends.

When asked about what the T meant to her, Stella brought up the topic of accessibility. How it allows for people of all backgrounds to have greater access in the city. Also for students like Stella who don’t drive, the T is a way to get around the city independently. “I’ve become very attached to public transit and how nice it is to have very well-connected public transit within a city,” she says. “I know a lot of people rely on it for their daily life.”

Li Yin, 18, a freshman at Wellesley College, takes the T to and from the city several days a week. She often switches between taking shuttle buses that Wellesley provides and taking the commuter rail. Once she is in the city, she often takes the subway or buses to get around. Li, who was born in China, and went to high school in California, also shared her experiences with public transit (or the lack thereof) in the places she has lived. “When I used to live near the LA area, it was very inaccessible because everywhere you had to drive,” she says, contrasting this to her time living in China, where “my school used to be like a 20, 30-minute ride away from my house [via public transit],” which was something she had to adjust to coming to the states.

She added that, “Driving is just a hassle sometimes, because you have to find parking; it kind of clogs the whole city…I feel public transportation in Boston connects the city in a different way and allows students to go places very quickly.” For Li, public transit is essential to a city like Boston, where students make up a significant part of the population. She expressed that “I feel like the public transportation in Boston connects the city in a different way and allows students to go places very quickly, and with an affordable price…I feel that Boston wouldn’t be as good of a city for students without its public transportation system.”

For all the benefits it provides, the MBTA has sadly faced an onslaught of issues in the past few years. The COVID-19 pandemic led to drastic drops in ridership in 2020 and 2021, and the transit system is still recovering. In 2022, the system was investigated by the Federal Transit Authority following several incidents reporting that the “MBTA’s long-term projects jeopardized daily operations and safety.” This led to an order from the authority to address “53 problem areas ranging from staffing and safety management to communications and operating policies, and called for an overhaul of safety culture inside the T.” The agency is still working to address these issues months after the initial report.

The T is the lifeline of the city. The bus and rail lines are like the blood vessels and veins that keep the city alive

In 1997, then-mayor Tom Menino developed a task force to implement Transit Oriented Development (TOD), which has led to the study and development of several projects from the MBTA and other companies. Their goal is “to enhance their quality of life by turning parking lots and underuti lized land near public transportation into vi brant mixed-use districts, diverse housing, and attractive entertainment venues.” These projects have led to significant urban development with over 50 projects sold or leased by the MBTA in the last 10 years.

For now, we can only wait and see if any of these projects will bring about mean ingful change to the city’s infrastructure and develop ment.

As I sit here, staring out the trolley window, I realize how the T is the lifeline of the city. The bus and rail lines are like the blood ves-

sels and veins that keep the city alive, ensuring that people have a way to and from their destinations. Without public transit, thousands of commuters would be left behind, unable to get where they need to go. The city is alive, and public transit keeps its heart beating strong.

As I roll through the stops to my destination, passengers from all walks of life get on and off. The students rushing to class, parents accompanying their kids to school, grandparents out to run errands, nine-to-five office workers on their way downtown.

For me, that is the beauty of public transit: no matter our age, our background, or where we are from, we are all here together, squished between the panels and seats making our way into the beating heart of this city.

By Morgan Gaffney

By Morgan Gaffney

Medication was something I thought about for a while before beginning. My brother had been taking Prozac for years, and it seemed to help him drastically. But if he missed it even for a day, his mood completely changed. I was scared of how much it could affect his demeanor and how much he relied on it. It was frightening how much one little pill could change a person.

I remember a day I couldn’t stop crying and feeling negative about the world, as if life was colorless. These dips from my normal, generally-upbeat mood were few and far between, but they were debilitating. I couldn’t understand why this happened, and couldn’t wrap my head around the fact that no specific thing was causing it. The day that I couldn’t stop crying was actually my birthday: a beautiful, sunny summer day. The leaves were blowing in the soft, warm wind, making the sun glitter and shimmer through the trees reflecting. The birds were chirping, the stream in the woods near my house was bubbling and flowing; all I could hear were the beauti ful, calming sounds of nature, yet tears continued to uncontrollably stream down my face.

I really scared my mom, who worries and takes it to heart if she can’t make my sadness go away. But in that moment, the reality was that nothing was going to make my sadness go away except waiting it out. That day, my sixteenth birthday, is when she knew we had to do something for my mental health.

My parents got me on a bunch of waiting lists for therapists, and after a few months, one responded. I remember being so anxious to see my new therapist for the first time, I sobbed uncontrollably in our first

appointment. I thought I surely scared her off for good. However, during my next appointment she said I didn’t frighten her, and that my reaction was a normal response to starting something new. I began seeing her regularly, and after a few months, I really felt like talking to her was helping my anxiety and depression. I would go through rough patches, but for the most part, I felt mentally leveled out, up until last year.

During my sophomore year of college, my anxiety began to ramp up around the end of the first semester, creeping into all areas of my life. There were a few outside, personal factors that might have been affecting its increased intensity, but it was unlike anything I had felt before. Instead of short spurts of heightened anxiety every now and then, it was constant. It felt like when your ears are ringing for no reason: sometimes you can ignore it, but there is always that continuous noise. Sometimes, it’s all you can hear.

I struggled for the last year and a half, while still seeing my therapist, which helped in some ways. She validated the way I was feeling, which was reassuring, and vocalizing my feelings to someone took a weight off my shoulders. But this only slightly soothed the dread I felt at all times.

When colder weather and darker days rolled around this year, I felt my seasonal depression sneaking up on me, which only made my anxiety worse. It was especially hard in Boston, where I don’t get to partake in the winter activities I grew up enjoying in Vermont like skiing, sledding and snowshoeing. Boston was so cold, windy and gloomy without any picturesque, snowy landscapes that resembled home. I knew it was time to make a change. I started taking a selective serotonin uptake inhibitor (SSRI), a medication to treat depression, anxiety and other psychological disorders.

Within weeks, I noticed changes. Life felt welcoming every day; the world

looked brighter; problems that came up were less stressful. I could not believe how much had changed in such a short time, and how I had lived for so long in the state of constant anxiety I was in. This was what I was missing.

…

Depression and anxiety are common in people everywhere, but a higher rate of people can experience these mental health conditions in cities like Boston. The busyness and fast pace of city living can be extremely overstimulating, causing people’s bodies to constantly go into fight or flight mode. This can overwork the psyche, and make people more vulnerable to mental illnesses like anxiety, depression or psychosis. The uncontrollable noise and movement can make it hard for city dwellers to cope with stress, and sometimes leads to anger management issues or substance abuse. The noise and bright lights can also contribute to a lack of sleep which affects energy and overall function of the body, further putting residents of urban areas at risk.

Kate Gustafson lives with depression and anxiety, and saw her mental state worsen when she moved from her small town to Boston for college. When talking about the energy of the city, Gustafson says “everybody’s kind of down,” and that “energy radiates.”

Michelle Mele, a native to Raynham, MA, used to notice her anxiety ramp up when she came to visit Boston. “I can definitely see a difference. If I wasn’t medicated right now, and in Boston, I’d probably be crying on the floor at the moment,” she says.

In addition to higher levels of mental health concerns, a higher-than-average amount of Boston residents experience seasonal depression. Thriveworks, a national mental health organization with many locations in Boston, conducted a study analyzing trending Google searches in correlation with weather patterns over the last several years. They looked specifically for searches related to seasonal depression and mental illness to narrow down when the worst of seasonal depression would be experienced by people this year; they found that the first few weeks of November are the worst for

those who suffer from seasonal depression, when the weather is just beginning to get a lot colder, and the sun begins setting earlier.

Boston is among 15 cities with the highest rates of seasonal depression. Seasonal depression can cause a lack of motivation, irritability, general bad moods, and high stress. This can affect college students especially who have school work and extracurricular activities to complete, coupled with finals as their semester comes to an end in the month of December.

“There’s a lot of just being in the dark inside, which triggers the loneliness and anxiety,” says Juliana Ferolie.

“If I’m going to have a really bad episode, it’s going to be during that time,” says Leah Kaliski, referring to periods when her mental illness especially affects her overall function during the cold, dark winter months.

Antidepressants or anti-anxiety medication work to increase the activity of neurotransmitters, molecules that transfer information throughout parts of the brain and body. Increasing activity of neurotransmitters like serotonin, norepinephrine and dopamine—all neurotransmitters linked to mental well-being—can reduce symptoms of anxiety and depression.

When Gustafson got to college, she knew she wanted to make a change to help her anxiety and depression. A few weeks after beginning to take medication, when doing her laundry—a task that used to feel draining and stressful to her—she realized it was helping her cope with her mental illness.

For Tarby, the effects of the medications helped her anxiety almost immediately. “The first time I took it, I was actually able to go to sleep at a decent time,” she says. “I woke up and I felt like it still had an effect on me, because I didn’t wake up with a high heart rate.” Tarby’s anxiety affects her most at night, making it hard for her to sleep, so she sees drowsiness as a side effect of her medication as a benefit.

Mele’s anxiety hindered her from participating in many social spaces, such as a workplace. In high school, when she decided she really wanted a job, she tried medication to help her operate in such situations; after a while, she could feel herself become more outgoing. “It wasn’t like I was a different person, it was just more of myself,” she says.

Kaliski could “see color again,” when she started antidepressants for her mental illness. “They made life liveable.”

In three months, I’ll spend my first summer hundreds of miles away from home. Which means that home will become a city 700 miles from what that word used to mean, because home is wherever my feet land at the start of June.

When people ask where I’m from, I think of the first house that felt like home: the long, cramped hallway and saffron living room with a green futon couch, and the sun-baked wood of a porch that looks out over nothing. I think of the plastic white step stool in a bathroom that barely fits one person, but was still used by four people, and a baby, for years. My memory drags me out to the fig tree my brother and I helped plant, the one that grew taller than we did. In my dreams, I am in this house more often than the bright new house almost double its size that I lived in for three years.

My family moved to that first home, on Dimmocks Mill, after I turned eight. My first home, not my first house, and the first of either my parents ever owned. 1819 Dimmocks Mill Road, Hillsborough, North Carolina. It was just after my birthday, and my last party in the house before that, on Apple Lane, was a picnic set on packed cardboard boxes instead of chairs. Five little girls ate cupcakes and drank tea, and I wore a navy blue dress with white lace flowers. We moved between October and November, and my first memory of visiting Dimmocks Mill is rooms filled with brown and stacked with airplane models. My parents brought my brother and I when they viewed the house, a long rectangle on one acre of land surrounded by the tallest trees I’ve ever loved. The house looked nothing like the one we had visited a few months later. My dad and two of his oldest friends spent every day working on our house for as long as it took. They ripped up brown carpet and painted over brown walls, and we each cast our votes on which

less-brown granite countertop we liked best. We hadn’t been there for long by the beginning of the year. My parents invited two or three other families to watch President Obama’s inauguration on a fold out couch in front of a tiny TV. I sat with a bunch of other kids, who are now my family, and somehow knew this was history. That day in January is one of my few memories from Dimmocks Mill that was set in wintertime. When I think about that home, meaning when I think about my childhood, it is always summer. I grew up in heat and sunburns and clay that hardens and cracks and grass that wilts under a blow up pool that occupied our Augusts. I lived at least ten winters in that house, but none of those are what I think about because there are no fireflies or lasting light in wintertime, and most of all no creek. The creek in the woods behind our house was more my home than the tiny space we crammed ourselves into for close to a decade. This creek didn’t belong to us, but didn’t really belong to anyone — the state maybe, which couldn’t mean less to a 10-year-old. I used to take the little path my dad cleared the summer he lost his job, and run to the biggest rock there was and count crawdads. I grounded colors out of stones and painted over broad leaves that floated down the tide to someone or something wherever my creek ended. Every part of the little girl I was remains in those trees that made up the woods, and in those rocks that made up a channel that swelled with thunderstorms, flooded its banks, and spilled with my secrets. Those Dimmocks Mill summers happened later in my life, when I was so unsure of myself but positive I was becoming something, the way many young teenagers believe the most important parts of life are happening to them. My summers then were weeding garden beds, weekly farmers markets, and the day camp I was supposed to be helping my mom with. My mom ran a summer camp out of the studio across our backyard

My memory drags me out to the fig tree my brother and I helped plant, the one that grew taller than we did.

every year that promised around a hun dred dollars, which, to me, could buy any thing. In return, I sweated in a sandbox and cleared children’s plates, waiting to win capture the flag at the end of the day. I was fast as a kid, and competitive enough to want to prove it. We played a couple games every day during pickup while the little kids had to stay inside, and one day our friend Caroline’s older brothers came with their moms to pick her up. Caroline and her brothers “had two moms,” as my own mother would say, which meant an awful lot to a kid who knew hardly a thing about herself or why that meant so much. When there weren’t camps, summer was spent on the back porch that burned and splintered in the heat. Summer was popsicle drips and a towel laid out next to a frosted ma son jar of iced tea. I could spend the whole day on that deck, until my skin was pink and the slats of wood left marks on the backs of my legs. I followed pools of sunlight from one end of the deck to the next, tracing the sun’s path over me. One warm day, I paced those sunspots on the phone with my best friend, a girl with bright blonde hair who I haven’t spoken to in years. I walked back and forth, letting my feet burn and blister as

she gushed about how the boy she liked had kissed her for the first time just hours before. My first kiss was years later, in my most recent house on Butler Road in my turquoise bed, close to midnight. I laid next to a girl with pitch-black hair who I convinced myself I didn’t love for months. We fell in love and kept it a secret, and then didn’t anymore and loved each other less. But that was not in summertime, which may be the biggest difference between Dimmocks Mill and Butler Road. Butler Road is mostly winters. It was winter when I learned how to fall in love, and chose to, winter when my heart was broken on the very first day of the new year, and winter when I finally felt like living again. It is mostly winter when I leave school to go home, to Butler Road, and our house is filled with lights and plants and our dark blue kitchen glows. My room stays almost exactly the same — the one I fell in love in and had my heart broken in and also started living again in — but the walls are bare and the air is stale. Butler Road is home because my family is there and because it’s a place to come back to, but only for a sliver of the year.

Now I live in a place that is almost always winter — real New England winter — and it’s as far from those Dimmocks Mill summers as I can get. I’ve spent two winters in this city and left as soon as the leaves turned green again. This year, I’ll stay to see the trees fill up again and the sky turn blue for the first time. I’ll learn where the sun pools at different times of the day and find moving water to tell my secrets to. Home will be a studio apartment and a girl with light brown hair and the best heart I’ve ever known. This year, I’ll make summer my home.

Icould make a whole playlist of songs that were ruined by my freshman year. Not only can I associate them with specific people or moments, but they’re tied to deeper roots. Pressing the play button on just one could pull up a system of memories, tightly woven and impossibly knotted. It’s impossible to escape the all-consuming emotions that come with just the first few notes of a song because suddenly, I find myself back in the same place I was a year ago.

What comes to my mind most often is a dorm room full of faces I’ve tried to forget, and specifically how a snowstorm in January bound us together. The cool blue haze coated the room as if in a dream. Remembering the familiar smell of dorm room carpet, laundry detergent and takeout stings my nose. How could a memory so potent also evoke strange feelings of comfort? In the present, we cross paths on the street, in various hallways and in the dining hall, and it feels like I’m reliving a nightmare.

I wanted to believe in the longevity and realness of our friendship. Still saved on my phone are screenshots of text messages from each of them that made me laugh until my stomach cramped. Still saved in my camera roll are pictures of everywhere we went together: Veggie Galaxy for my birthday, SkyZone to cheer ourselves up during midterms, and their suite where we simply enjoyed each other’s company. Also saved on my phone are messages from a randomly-generated number that were sent by people who had once been family, be-

littling me for the things they once praised me for. Suddenly, my camera roll, similar to old playlists and little pieces of memorabilia left behind, all places full of rich memories, became an emotional minefield. At first, moving forward seemed like an impossible task: in our friendship, they promised me forever, a distorted version of the future I desperately held onto. But in a split second, everything I had ever confided in them was used against me—my vulnerability, honesty and care were each weaponized. I learned to hate myself for being so trustworthy. Trauma has the unfortunately clever ability

to seep into the cracks of life. But experiencing it in a place far away from home is isolating. I remember the first time I felt it creep into my skin like some unshakable thing. Never before did I spend so much time keeping myself occupied in my own room, suddenly too timid to leave. In those moments, I constantly questioned myself and my emotions—was what I was feeling real? It was bizarre that the people stuck in memories had better authority over my feelings than I did at the time. I tried my best to avoid reliving the nightmare that they’d created for me. But time after time,

my efforts to remove myself and move on were ruined by their seemingly inescapable presence in my life. Perhaps this is from my own mind’s inability to forget. Maybe it’s from catching a glimpse of their face and wondering if that laugh came from them.

As someone who thought that a life completely different from their own growing up was the ultimate antidote, experiencing trauma in a place I pinned all of my hope on was one of the most devastating experiences. I spent half of my adolescence yearning for experiences that I could never have had in my home town. College was the perfect opportunity for excitement: a real life, parties, friendships that would last a lifetime. Growing up, I often found myself in a cycle of confusing familiarity with hurt. Every time I experienced some sort of hardship, I blamed it on the unchangeable factors that were all I knew at the time. I blamed my home town because it was all I knew and I hated it. I applied for Emerson wondering how I could ever experience sadness in a place that held so much hope and excitement. I believed in the absence of pain in a future life. Constantly placing such high ex-

pectations on the future locked me into a cycle of not knowing when I’ll experience authentic joy again. In just a year, I rewired my brain to believe in a life that holds wounds just waiting to happen at every corner.

Being unexpectedly hurt away from home can be an extremely othering experience. Never before had I ever felt so removed from a place after I experienced what I did. But as the months have passed and I’ve physically removed myself from the source of the trauma, I’ve taught myself ways to ease the hurt. Recently, I picked up an old habit that should

have remained constant in my life: journaling. The more I wrote and transferred onto a piece of paper, the more I felt like I belonged again. Suddenly, I felt myself believe in the power of my words. The feelings that I once questioned so heavily were my own again. Trauma silences everyone who experiences it, and I am determined to not let that happen to me. But in times when I feel like a piece of paper couldn’t hold everything I need it to, I found comfort in quietly speaking under my breath until my body felt lighter. Talking to others and making new friends along the way has added a tremendous amount of light to my life in places where it once felt so dark. I couldn’t be more grateful.

This past year may have been filled with doubts, dejection and reflection, but at the same time, I’ve taught myself to celebrate the little successes that come with healing. I’ve learned to embrace the present especially. I may not be able to revisit certain memories or moments, but I like to think it’s a sign that they’re not meant to be revisited anyway. Each new day is filled with new songs, new pictures and new experiences. While they can’t rewrite what’s already been put into the past, I find comfort in going to bed grateful every night knowing with confidence what is behind me and what is to come. Everything is constantly changing, and always for the better.

Photographed by Lily Farr

Design by Lily Farr and Abigail Albright

Assisted by Renee Mundra and Jena Roseman

Modeled by Khatima Bulmer Jessica Zhang

Photographed by Lily Farr

Design by Lily Farr and Abigail Albright

Assisted by Renee Mundra and Jena Roseman

Modeled by Khatima Bulmer Jessica Zhang

More and more, we identify ourselves by the media we consume. If you haven’t listened to/watched/read the latest thing, good luck making small talk or keeping up with social media.

I know I’ve spent my fair share of time checking out artists, shows, and movies I wouldn’t otherwise be interested in just to stay informed, and you probably have too. Look in any corner of the internet, turn over a proverbial rock, and an army of devout fans will come scurrying out. Almost every content creator and piece of media has some sort of devoted following.

Being a fan is no longer an act of passive enjoyment or engagement; it’s a behavior, a trait to be incorporated into one’s sense of self. At this point, doing so has almost become a source of cultural capital — to know more about a particular creator or piece of media is to have more clout to wield against the less-informed. And the price we pay for not buying into this practice goes beyond falling out of touch with the cultural mainstream. It can feel really alienating, too. What effect is the commodification and commercialization of our very identities having on our sense of self?

According to scholars, this trend can be traced back to the rise of consumerism and the growth of marketing and advertising over the course of the past century and a half. Ronald L. Jackson II, a professor of communication, culture, and media at the University of Cincinnati, calls the sense of identity that results from increasing commodification and consumerism the “commodity self.” In other words, “one’s own subjective identity arising from the commodities (goods or services) one purchases and uses” (106). People are seen as consumers rather than individuals, and over time this has contributed to the merging of “commodity and consumerism with subjectivity,” giving rise to this new “commodity self,” rather than an individual identity based on somebody as a person (Jackson II 106). Joseph E. Davis, a professor of sociology at the University of Virginia, says that because we make sense of ourselves through the “choices we make

from […] the market,” these choices, be they movies, shows, music, fashion, food, or otherwise, become the means “by which we perceive others and they us.”

One of the most prevalent effects of the commodification of our identities is the conflation of the media one consumes with the person themselves. The result of this is that the morality and quality of the media comes to stand in for the morality and quality of the person consuming it.

Music is an obvious candidate when talking about media with wild amounts of wild fans. Taylor Swift, the third most streamed artist of all time on Spotify, has over 42 billion streams to her name. A single person can generate multiple streams, however, so it’s not as though 42 billion different people have streamed her music. With that said, she currently has more than 80 million monthly listeners on Spotify. On October 22, 2022, Twitter released “The Swift Report,” an evaluation of Swift’s impact on the platform that says a lot about both the artist herself, and music fans the world over. According to the report, Taylor Swift had been mentioned in 329 million tweets since 2010, and when “Red (Taylor’s Version)” came out in November 2021, the tweets about Swift outnumbered those about football and basketball, combined. The word for Swift’s fan, “Swifties,” had been tweeted 18 million times over the 12 years preceding the report.

You can’t talk about music fans without talking about BTS and their army of fans, who appropriately refer to themselves as ARMY (which stands for Adorable Representative M.C. For Youth). In 2021, BTS were “the #1 most tweeted-about musicians in the U.S. for the fourth year in a row,” according to Rolling Stone. When their single “Butter” was released, BTS fans generated 300 million tweets over a one-month period from April 24, 2021, to May 23, 2021. And if that wasn’t enough, five million tweets were generated in a single hour between midnight and 1 a.m. on May 21, 2021, when the single actually released.

Since the invention of the internet, and particularly the creation of social media, we’ve all gained a new facet to our identities: our online self. Because this version of ourselves is entirely curated, rather than organic, the most prominent components of it are frequently the things we like and want to show off that we like.

It would be impossible not to discuss the Walt Disney Company in an article about how the media we consume has come to represent a person’s identity. Disney is one of the driving forces between the monopolization and sanitization of cinema. Additionally, regardless of how one feels about the Disney company or the movies, they likely don’t think very highly of so-called “Disney adults.” If you’ve made it this far without encountering a Disney adult, consider yourself lucky and think about buying a scratch-off. Disney adults are grown people who, in the generous words of NPR, “spend vast amounts of money and time on Disney-related products and experiences.” Think of the sort of person who incredulously, but a little too seriously, says, “What! You’ve never seen [insert movie here]? I don’t know if we can be friends anymore.”

I’m not personally a fan of the Marvel Cinematic Universe; however, I’ll admit that I’ve seen a few of the films for the sake of keeping up with popular culture, moreso than out of any personal interest. They are inevitable. Appropriately, and unfortunately, the franchise is owned by Disney. Four of the top 10 highest-grossing movies of all time are Marvel movies, and eight of the 10 highest-grossing superhero movies were also made by Marvel. Going once again by Twitter metrics, in 2018, “Black Panther” became the most tweeted about movie of all time at 35 million tweets, until it was surpassed by “Avengers: Endgame” in 2019, at 50 million.

Gamers are a group that one might not necessarily categorize the same way as music stans and diehard Marvel fans, but I think it’s an important example. People who make a hobby of playing video games and think of them as a facet of their identity sometimes call themselves “gamers.” There’s no set level of being “into” video games someone must meet to call themselves a gamer, but the nomenclature is telling; it reinforces the idea that what you consume is what you are.

Videogames have a huge community that’s not limited by language barriers, like music and film often are. PUBG Mobile, a mobile version of the battle royale PC game PlayerUnknown’s Battlegrounds (PUBG), has reportedly been downloaded over one billion times outside of China since its launch in 2018 (Li). Riot Games, the developers of League of Legends — a game for which the world tournaments payout over $2 million — tweeted in November 2021, that in the month of October, they had reached 180 million monthly players. That’s like if more than half of the population of the United States each played the game once. And it wasn’t a one time thing either; in 2022, Esports.net reported that almost every month of that year, more than 150 million active players had played the game each month.

Ultimately, the driving factor behind the commodification of identity has and continues to be corporate greed, and the ability of corporations to worm their way into every facet of public life and monetize it. While the process requires buy-in from consumers, it’s an inescapable product of the capitalist system we live under, rather than the result of individual choices. Our commodity selves aren’t who we truly are, but it’s really hard to separate ourselves from them. Not liking or engaging with a popular piece of media doesn’t necessarily make you better than someone who does though. If you make it into some sort of litmus test for morality, you’re just reproducing the system. It’s important to be aware of our place in society, and how we make sense of ourselves in relation to others — don’t limit your conception of self to the things you consume. We’re more than that, we’re not just consumers, we’re human beings.

Ultimately, the driving factor behind the commodification of identity has and continues to be corporate greed, and the ability of corporations to worm their way into every facet of public life and monetize it. While the process requires buyin from consumers, it’s an inescapable product of the capitalist system we live under, rather than the result of individual choices.

Igot into college on the basis of an essay I wrote about expressing gratitude for the intensity of my emotions. The 2018 film Thoroughbredssparked my interest in their importance. The film follows two friends, Lily and Amanda, who set out to murder Lily’s stepfather. In the end, Lily plans to frame Amanda for the murder, on account of Amanda’s pre-existing reputation of being a sociopath. Lily asks Amanda what purpose her life has if she cannot feel. It is this question that prompts Amanda to allow Lily to frame her for the murder, sending her to the psych ward indefinitely.

I wasn’t Amanda. I existed on the opposite side of the spectrum. Like Lily, I felt too much. Everything seemed to overwhelm me. I was either consumed by an urgent restlessness or too encumbered by my own despondency. Examining Amanda’s numbness and realization of her lack of purpose caused an epiphany of my own: perhaps these overpowering feelings are what qualify me most to perceive reality through human eyes. After all, this innate ability also meant that I experienced joy just as deeply, even if it wasn’t as frequent. I concluded that I was lucky, for it is these feelings, as Lily proposed, that make life purposeful.

Now that I’ve been on antidepressants for three years, I’m struggling with—or rather, fearing— the idea of my writing not living up to its previous emotion-riddled state. When I read old pieces of mine or scroll through excerpts in my notes app, I can’t help but feel that I’ve lost that certain poetic touch that my pain routinely seemed to add. The subject matter hasn’t changed all that much—I still predominantly write about my own struggles—but I can’t seem to grasp the same attention to detail. My previous suffering supplied a depth that is specific to emotion so strong that it’s tangible.

Being on antidepressants masks that. I can only feel it at a distance. While the medication has enabled me to function, I often wonder what the caliber of my writing would look like if I stopped taking them altogether.

Believing that suffering produces my best work is not exactly a niche opinion. Emily Rice, a junior journalism major, says, “It’s a stereotype, but every writer is afflicted with pain. There’s just something stewing in there all the time. Writing is simply just the means of taming the beast.”

As Rice points out, the stereotype is true to a degree. A lot of us fall under the “tortured artist” category. We are constantly attempting to understand and morph our pain into something beautiful, to “tame the beast,” as it were. But I figure that there must be a reason why so many renowned artists are the most depressed people, or why some of the greatest works are tragedies and dramas.

Junior media studies major Marisa Drogo explains that she believes it’s because art is often used as a tool of release.

“When things are good, there is no outlet that I need to [use to] relieve myself. Art is very grounding for me, and [usually] I need grounding when I’ve gone through something painful or have something to work through,” says Drogo.

Rice, in agreement, adds, “You never want to release happiness. You just want to hold on to it.”

Art begins with the urge to create. It’s difficult to find that urge when happiness can feel so fleeting. Many of us just want to savor an experience rather than immediately turning to illustrate it. Intensity exists on both sides of the emotional spectrum, but the difference lies in the desire to vent, to splatter it all over the page in an act of catharsis.

Rice explains that the most profound pieces she has written have been borne from past trauma. “It really helped me to compartmentalize not only the memories, and why those have stuck with me, but how they’ve impacted me now. I love that I have it as a tangible thing for me to look back on and know that I’ve [grown].”

Satisfaction and healing can drive us to create, making our work especially gratifying. While this is undoubtedly positive, we can often equate meaning or depth exclusively to art that contains suffering. There’s an increasingly popular notion, as ridiculous as it may sound, that happiness is overrated.

“When I am writing creatively, I want nothing about it to feel perfect. When I write from a place of happiness, it pulls me more toward the idea of painting a perfect picture. And to a degree, it’s just not relatable, and almost boring,” says Rice.

The idea of happiness being overrated is enforced by consumers just the same. There is a growing obsession with the expression of sadness, especially within music. Rice attributes this to a need for consolation through shared experience: “How openly do we really

talk about pain in our everyday lives? Music is such a form of escapism. You [can] listen and feel like ‘Oh, the Weeknd also got dumped.’”

Consuming this kind of art allows us to interact with and process our own pain without having to actually have that conversation aloud. While this is important, the demand for music of this nature can negatively impact the artist. How many times have we seen people celebrate musicians’ breakups in anticipation of an especially good album? People cheered upon hearing of Adele’s divorce. Some even criticized Lorde’s most recent album, Solar Power , for lacking the depressive attributes of predecessors

In her documentary drivinghome2u , Olivia Rodrigo admitted: “I’m terrified that since I’m not gonna be devastated for the rest of my life, I’m no longer gonna make a good album.” When the audience agrees with the notion that your work is better when you’re in a bad place, it’s hard not to believe them.

“Having expectations for artists to always produce something based [on] their emotions can get a little bit rocky, because you’re kind of praying on their downfalls,” says Drogo.

This overwhelming sentiment gives impetus to an internal war. Drogo acknowledges that some of her best work comes from when she’s feeling the worst—but at what cost? “Would I rather feel bad and create good, or feel good and create [nothing]? That’s something that I have to wrestle with a lot.”

Using art as a means of coping can be beneficial, if not life-saving. As Rice points out, it can be a tangible testament to growth. But it can also keep us stagnant—perpetually trapped in crisis or a state of melancholy. Not only do we risk wallowing for an unhealthy amount of time, but we practically invite more pain in. The more we believe that we can only create within these specific parameters, the more we will manifest our own misery.

But how do we get out of this bubble? It sounds contradictory, but there can be a sense of comfort in sulking and bearing that sadness onto the page or canvas. In order to leave this comfort zone, we need to reprogram how we think about our own art and ability to create. Art that is made from a place of joy doesn’t have to be one-dimensional or corny; it can be just as thought-provoking as art made from a place of anguish.

Stepping out of the bubble doesn’t need to start with creating right away. Exposing yourself to media that conveys something other than sadness can enable more confidence in creating from a similar headspace. Even watching sitcoms like Schitt’s Creek has shown me that there is a way to write joy in a way that can be just as impactful to an audience. While that can be difficult to immediately emulate, I have recently found that journaling about a particularly good day or even a small moment has made me less apprehensive of my ability to write from a happier place.

It is a continuous effort to not fall into old patterns. This is not to say that I will stop writing about my own pain. Even with the medication, I still feel like I am not exactly happy most of the time. They always say, “Write what you know,” and that’s what I’ve done thus far. But if we limit ourselves strictly to what we know, we learn nothing. I might not know happiness as intimately, but I would certainly like to try it.

Do not complain about growing old. It is a privilege denied to many.”

Aging is a privilege. A privilege that is often forgotten. Women who are on social media today are constantly bombarded with TikToks about anti-aging products that don’t work and Instagram posts that highlight new body parts that they should be insecure about. Women’s bodies go in and out of fashion every season, and right now, the big trend is anti-aging.

Social media plays a massive role in this, but it’s not the only factor in why most women are so scared to age. The fear of aging has been around way before the rise of social media, with media depictions and advertisements drilling in the belief that it’s imperative for women to do everything in their power to look as young as possible. I’ve seen TikToks of girls warning their followers about smiling “too much,” because that will give them wrinkles. There are a plethora of beauty influencers who promote overconsumption with their 12- step skincare routines, which consist of lotions and oils specifically promoted as preventing wrinkles. This influx of social media has created a shift in anti-aging discourse that I believe to be relatively new. Instead of wanting to reduce the appearance of wrinkles that we already have, the beauty industry is actively pushing to prevent getting wrinkles in the first place. Not only are there products for when you’re older, there now are products that are created with the purpose of “aging gracefully.” The desire to look younger is no longer being advertised: the goal is now to never age in the first place.

It’s clear that this fear of natural aging is more profitable than being comfortable in one’s own skin. The selfconsciousness that many women feel about their bodies changing can often lead to them projecting their insecurities onto other women, instead of the systems that encourage their self-loathing. An example of this is the “Snow White” syndrome.

Everyone knows the story of Snow White. She’s a beautiful princess (at the mature age of 14!) who suffers at the hands of her old stepmother, who’s envious of Snow White being “the fairest of them all.” The stepmother used to be the fairest woman in the kingdom, but was ultimately replaced by someone younger than her. This envy that the stepmother feels, leads her to do anything in her power to get rid of Snow White. Snow White Syndrome is a term coined by author Betsey Cohen, who utilizes her social work and psychiatry background to deconstruct our society’s current understanding of beauty standards. Cohen uses the fable of Snow White to demonstrate how envy is weaponized against women, turning fellow women against each other. The envy that many older women feel toward younger people is intentionally constructed in favor of the beauty industry.