16 minute read

Rising to the challenge of Monstrous mountains

by Audax UK

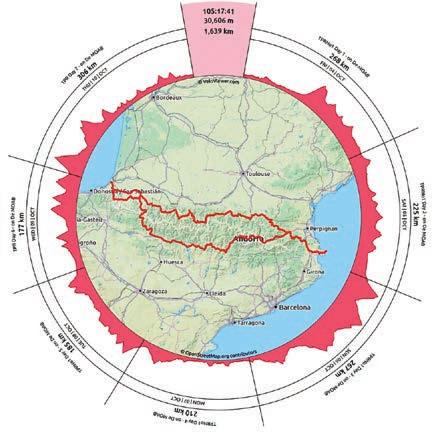

From the Mediterranean Sea to the shores of the Atlantic Ocean – and back, the Trans Pyrenees Race is a 1,500km ordeal of epic proportions across one of Europe’s most spectacular mountain ranges. Aware that his preparations had been less than ideal, Joss Ridley wasn’t even sure he’d finish. This is the story of how he tackled the 2019 race. Rising to the challenge of monstrous

NOT BEING A NATURAL CLIMBER, this race didn’t really suit me, but I’d always wanted to cycle in the Pyrenees, and this would give me a flavour of big unsupported bike races, so I entered on a bit of a whim.

Advertisement

The event, at the beginning of October 2019, was the first to be organised by Lost Dot, the people behind the famous Transcontinental Race.

My preparation wasn’t ideal. All my training had been focussed on my attempt at Paris-Brest-Paris. I didn’t even have a suitable bike for the Trans Pyrenees as I did almost all of my Audax rides on a fixed wheel bike.

Being accepted on to TPR in early March gave me the perfect excuse to buy a new “super-bike”. I settled on a bespoke steel frame built by Jaegher in Belgium. The bike was designed to be somewhere between a road bike and a gravel bike, with a SRAM Force eTap AXS groupset, SWS carbon wheels and finished in a glorious metallic burnt orange paint job. It was stunning.

The only problem was it arrived in the UK while I was riding PBP – and only six weeks before TPR. My feet and hands weren’t great after PBP, and I wasn’t very motivated to go out and train, even with the new bike. So, come the end of September, I panicked and went out and did about 500km in the week before TPR, but mostly in the rolling Essex countryside.

In Biarritz a couple of days before the start of the race, I was still tired, stressed THE TRANS PYRENEES RACE is a self-supported, single stage race in which the clock never stops. Riders plan, research and navigate their own course and choose when and where to rest. They take only what they can carry and consume only what they can find. Four mandatory control points and associated parcours, plus four separate parcours, guide the route from west to east and back again, through 1,500 km of the most remote routes of the Pyrenees.

and nervous. My neck ached and I really didn’t feel in great shape. I met fellow competitors who looked super fit. Some had even shaved their legs!

The day before the race, the riders gathered to show insurance documents, make sure our bikes were safe and to pick up our GPS spot tracker. Every competitor had to carry a spot tracker so that the “dot watchers” at home could keep an eye on us and make sure we were following the designated routes and not cheating.

Every competitor had to plan a route between these controls and parcours, minimising distance and elevation gain, while making sure we could resupply along the route. After working out my route, taking in the parcours and controls, I was facing about 1,600km with 32,000m of climbing. To qualify for an official finish I had exactly one week to make it back to Biarritz.

My plan was to cover roughly 250km a day, and leave 100km for the last day. I felt this gave me enough contingency in case of bad weather or other problems. I had scoped out potential places to stop for the night, and was hoping to make it to a hotel most nights. At the last minute I decided to take a sleeping bag and a bivvy in case I got stuck in the mountains and had to sleep by the side of the road.

All the competitors gathered together to pick up their race cap and listen to the race briefing delivered by Anna Haslock. I was going to be cap number 89 – #TPRNo1cap89 – my first personal hashtag! Looking around the room of roughly 100 people, I realised I was definitely in the heavyweight division. I thought to myself: it doesn’t matter, just go out and enjoy the first few days. I went to bed early, anticipating the 4.30am alarm clock and the imminent start of the race.

DAY ONE: BIARRITZ TO SABIÑÁNIGO

268.43KM, 4,441M

It was still dark and starting to spit with rain when we lined up at the start. We were let off in waves of about 20 people. I was in the last wave to set off – obviously

Joss Ridley is a 44 year old Essex-based rider who runs The Compasses public house in Littley Green near Chelmsford. He describes the pub as the “spiritual home” of the Audax club ACME. He’s been cycling seriously since 1995 but only started riding Audax events in 2018

mountains

❝I was in the last wave to set off – obviously the “fatties wave” at the back ❞

the “fatties wave” at the back. I promised myself to go very slowly to begin with. Everyone else seemed so strong. They raced off up the first few hills out of Biarritz.

The sun came up and I settled into my work, trying to keep everything easy and light. I passed one or two cyclists and was overtaken by plenty more, but I just tried to relax and ride my own race.

I’m not built for hills, but I didn’t disgrace myself, and I’m not ashamed to say I got off and walked on some inclines. While recognising I wasn’t in the mix for the win, I still needed a good night’s sleep to be able to go again the next day.

The descents were epic – the bike was so stable that I made up some of the time I lost on the up-hills. Strangest story of the day? Someone crashed into a cow and broke their frame.

In hindsight, I probably went off too hard, even though I spent some time walking up the steep gradients. It’s difficult not to get overexcited when there are lots of other cyclists around.

DAY TWO: SABIÑÁNIGO TO ALINS

224.85KM, 3,528M

Though not as steep as yesterday, it was relentlessly up and down all day, and the sun took its toll. I got a pinch flat going over a cattle grid. The heat really caught up with me and I had to stop more than I wanted to, mainly for drinks. My hydration strategy was getting a little better as the race progressed, but I was now starting to get into a deficit. But 485km out of 1,600 in two days wasn’t too bad.

DAY THREE: ALINS TO LA JONQUERA

266.88KM, 5,122M

A 4am start, and a puncture at 4.10am. You tend to question your life choices when you’re mending a puncture in the pitch dark. It was difficult to pick your line in the dark, and the descent into La Massana and CP2 was freezing. It took me a long time and two cups of tea to thaw.

Then there was the small matter of the 28km climb out of Andorra past “El Pas De La Casa”. It was long. My coordination had gone and I found it hard to clip in or rest my bike without it falling over.

I didn’t get into my hotel until about midnight. It had been a really tough day and I was proud that I kept going considering my poor balance while climbing up to Port d’Envalira. The exhilarating downhills certainly helped my mental state. I had to dig deep to get over Col de Palomere. My feet were playing up, but sizeable chunks of walking certainly helped. My strategy was to keep moving, either on the bike or on foot – and by that stage there wasn’t much difference in speed between the two.

DAY FOUR: LA JONQUERA TO MOLITG-LES-BAINS

210.41KM, 3,156M

This was supposed to be the “easy” day – a nice flat run down to the coast, over a small headland, get my brevet stamped, and then head back into the hills. Unfortunately, someone had obviously upset the gods as we were faced with 45mph northerlies gusting to 60mph.

It was tough just trying to stay upright. The last few kilometres to Cap De Creus was so windy that I had to walk, at one point my bike taking off into a horizontal position like a kite. When I was having my photo taken, my glasses blew off and went over a cliff. Fortunately we managed to scramble down and find them.

❝Sabiñánigo to Alins… though not as steep… it was relentlessly up and down all day, and the sun took its toll… The heat really caught up with me and I had to stop more than I wanted to, mainly for drinks ❞

I’d felt a bit sick all day. I was dehydrated from the day before and was playing catch up. The climb up through Oms to La Bastide was pretty good though – it really is beautiful countryside. My feet were getting worse each day, and my neck hurt badly on the descents, especially in the dark.

I wasn’t sure I had enough left in the tank to finish. But with 650km left over three days, it wasn’t impossible, even though there was 5,000m of climbing each day. I planned to enjoy my night in Le Grand Hotel in the spa town of Molitg-les-Bains, have an early breakfast and see how I felt. DAY FIVE: MOLITG-LES-BAINS TO CASTET-D’ALEU

184.81KM, 3,701M

Another puncture almost did it for me, but I managed to patch a spare. There was 470km to do in two days – which included over 10,000m of climbing.

And this was the toughest start so far.

The hotel bed was big and comfortable, my neck was really bad and I was in a Spa Hotel for goodness sake! I told my wife Linda that I was going to spend another night there and then slowly cycle back to Biarritz and try to make the party on Friday night. Linda encouraged me to go and have breakfast, even if I had given up. It was important, she said.

At the breakfast buffet I helped myself to everything – about three times! On my third coffee and umpteenth croissant, having watched numerous riders pass me on trackleaders and having contemplated whether I was going to go for a swim first or maybe have a massage, I started to feel better. Before I knew it, I was back in my slightly damp and sweaty top, packed and ready to go.

The climb up to Col de Jau was one of the most picturesque of the entire week. A group of TPR riders had gathered at the bakery in Belesta. People started talking about whether they could get back in time. Three or four decided there and then, they weren’t going to make it.

Talking to Dan Sparrow afterwards, we both agreed that the fact others were giving up spurred us on to keep going, even if there was only a small chance of

us making it back in time.

A lot of people had decided to stop in Tarascon-sur-Ariege for the night. Eating a pasta dinner in the Lidl car park, I pondered whether to go on or not. By this point of the day, I’d only done 135km or so, and it was only 7pm – far too early to turn in. Normally at this time of day I’d book a hotel, but there didn’t seem to be any left on the road ahead. I decided to carry on without a plan. I’d dragged my bivvy and sleeping bag over countless hills so I had to use them at least once. Once I got going, I resolved to get over the ❝ … The climb up to Col de Jau was one of the most picturesque of last couple of big lumps of the day and then find a the entire week. A group of riders had gathered at the bakery in suitable place to camp, Belesta… three or four decided somewhere there and then, they weren’t before St-Girons. DAY SIX: going to make it ❞ CASTET-D’ALEU TO SAINTE-MARIE DE CAMPAN

176.97KM, 4,229M

Mark Christy came out to cheer me on the Col De Menté. I was so in the zone, I couldn’t even work out if he was speaking English. I thought he was a crazy Basque. All I could understand was my name, so I gave him a thumbs up. It was a fabulous effort by him, and made a course would be enough. A third of the big difference to my day. field had already pulled out.

I fell short of my target owing to the I managed to bag the last hotel in rain. I just couldn’t keep anything warm or Sainte-Marie De Campan but it wasn’t dry, so had to cut it short before getting easy to find. When I got there it was all hypothermia. But there was still 300km to shut up. Eventually, I found a door and an go on the last day. Just to complete the envelope with my name on it. I made so

much noise that the owner came out. He took one look at me and immediately offered me hot soup, bread and cheese. I can’t tell you how much of a life-saver that was. Looking back, it was the single most important moment in my race.

DAY SEVEN: SAINTE-MARIE DE CAMPAN TO BIARRITZ

306.15KM, 6,429M

What a last day. More than 300km to ride, 6,429m of climbing (including Tourmalet and Aubisque) and a little under 22 hours in which to do it. Despite intending an early start, I enjoyed a decent breakfast and finally set off at 8am.

My legs felt sluggish and the bike felt like it was made of lead. But I soon got into a rhythm on the Tourmalet. It has a formidable reputation, but for me it was the perfect warm up – between 7 per cent and 9.5 per cent all the way up for about 17km. There’s a bludgeoning constancy about it that works for the way I like to climb.

Getting to the top without stopping or going into the red, gave me the confidence that I might be able to pull this off if I kept pushing all day. Somehow I’d ridden myself into form and now it was all possible.

Having got to the top of the Tourmalet with an average of less than 10kmh, I knew I had to push the downhills, thrash the transitions between climbs and minimise stopping time. I got to the foot of the Soulor having raised my average to 15kmh. The climb up the Soulor and then on to the Aubisque was totally different from the Tourmalet – lots of changes of gradient which I found hard.

Having got up and over the two big climbs of the day I was feeling optimistic. The only wrinkle was my phone, which was playing up after all the rain the day before. I use it for navigation, and if I couldn’t follow the parcours correctly, my ride wouldn’t have counted. It was the thing that stressed me out most all day. I put it on airplane mode and turned the screen brightness down to preserve it for as long as I could, but it seemingly died with about 100km to go.

I stopped at about 10pm to charge it at a hotel whilst munching on frites. Unfortunately, I couldn’t breathe any life into the phone and I was resigned to trying to navigate using my watch at night, which can best be described as a little vague!

Although I was out of the high Pyrenees, there was still the 500m climb over the Col D’Ispeguy into Spain and then back over the Puerto d’Otxondo. Miraculously my phone came back to life for about half an hour which allowed me to navigate around the tricky gravel roads in Spain, but finally died on the downhill after Otxondo but I felt confident I could get back from there.

I rode with other cyclists to the finish. It was a relaxed ride in, knowing we had plenty of time in hand. Sharing the moment with other people I’d bumped into over the last seven days made it extra special. We rolled in at about 4am. Hugs all round, a few tears, and amazement in realising what we had just pulled off.

I’ve had some epic days on a bike, but this was a new level. I’d never pushed so hard for so long without needing to stop. I was completely in the moment. It’s one of the reasons I ride a bike. And to do it in the Pyrenees, over some legendary climbs – well, it just doesn’t get better. I finished with two hours to spare. There were only 45 finishers out of a field 107. My final position was 37th after starting time adjustments – six days, 22 hours and 27 minutes. By comparison, the winner did it in four days, seven hours and 28 minutes.

I was on a high for about three days afterwards. Biarritz was buzzing and everything felt so visceral. However, the incredible high was met by an unbelievable low for a couple of days when I got home.

It took me a good two months to feel normal again. I think the problem was that I didn’t take proper care of my recovery straight after the race which prolonged the time I needed. Plus my knees and pelvis haven’t been quite the same since.

Would I recommend TPR to other cyclists? Yes, of course. Would I do it again? I’m not sure. But I’d like to go back one day when I’ve stopped racing and take a little time over the “Route du Fromage” – with a couple of empty panniers and a cheeky bottle of vin rouge.

OTTAVIO BOTTECCHIA The inspirational Le Geant du Tourmalet at the top of the Col du Tourmalet depicts Ottavio Bottecchia on stage 6 of the Tour de France 1924. In spite of losing time after hitting a stray dog, Bottecchia became the first Italian cyclist to win the TdF, and the first cyclist to wear the yellow jersey on every stage from start to finish. Why he is represented without his jersey (or anything else, save a little hat, for that matter) Wikipedia doesn’t tell but it looks pretty parky to me [ed].