12 minute read

Seeing Beyond Disability/My Vision for Ability Equality

Seeing Beyond Disability

Dr Paul Harpur’s Fulbright Future Scholarship originally aimed to critically examine how universal design systems are made to ensure that the most silent and vulnerable persons with disabilities are not excluded from this transformational reform agenda.

His project involved primary research on disability and technology, with plans to enhance links with overseas disability research centers, including the Harvard Law School Project on Disability and the Burton Blatt Institute at Syracuse University.

Yet face-to-face interviews, workshops and conferences became a sudden and abrupt impossibility with the social distancing caused by the COVID-19 pandemic that hit in full force two weeks into his three month project. The pandemic meant his method was impossible, but despite the setbacks, Paul still found a way to not only keep the project alive, but broaden its scope to include the impact that public health crises have on society’s most vulnerable.

“In my wildest dreams I would not have wanted to live through a pandemic, but what an opportunity to gather data on how society reacts to ability diversity when the institutions and rules in society fall apart.” Paul rapidly pivoted his plans to analyse how the pandemic was impacting upon people with a disability, and he immediately sought ethics clearance for a new project: Academics with disabilities during COVID-19. He reorganised meetings to source feedback from experts working in medical and data ethics at Harvard University, including the Harvard Law School Project on Disability, the Petrie-Flom Center, and the Berkman Klein Center, resulting in significant new connections and new publishing opportunities.

Across March and April, with the pandemic rapidly escalating in severity, Paul still forged ahead with meetings, workshops, and symposia making use of technology where social distancing prevented face-to-face meetings. His findings have resulted in research papers, articles, and even a speaking spot in an upcoming TEDx talk. In the midst of all this, he was nominated for, and won, an Australian Award for University Teaching through Universities Australia, for his work leading ability equality in the university sector and promoting universal design on campus.

But it wasn’t easy – Paul faced a number of challenges as a sightimpaired individual alone in a foreign country. The Harvard Law School Project on Disability had arranged exceptional supports, and when they fell apart with COVID-19, went above and beyond expectations in offering alternative assistance.

It turns out that support was needed. Paul had left his guide dog back in Australia and was navigating using only a white cane. He had worked out certain locations to source food and supplies, only to have the doors on several shops close when social distancing rules hit. Bus services and taxis became harder to source as services became suspended. When libraries shut their doors and most student and staff started working from home, it was unfortunately time for Paul to head home to Australia.

“My time at Harvard began with a splash – my hosts at the Harvard Law School Project on Disability had organised a fantastic workshop, jointfunded with the Harvard Committee on Australian Studies. Through this I was able to actually meet with the people tasked with drafting the new University-wide Digital Accessibility Policy.

“The policy aims to make information and resources more easily available to those who need it at Harvard, and while I believe the rules still need to be broader in scope, their commitment to improving information access should be applauded.” Now back home, Paul plans to maintain the links he forged during his time in Boston, and follow up on at least five new projects that have stemmed from his Fulbright research. Despite the dire circumstances that brought him home early, Paul’s thoughts on it all is refreshing and circumspect.

“Those of us who were privileged to be abroad in the first half of 2020 had the most unique of all experiences -- we are the only Fulbright cohort to have lived through a global pandemic. COVID-19 cut our projects short and caused us anguish, but it also bought us closer to our fellow Fulbrighters, those who we were visiting and provided new opportunities.

“This is a moment in time that washed away society’s veneer and laid stark prejudice, challenges and love.”

Paul’s vision for ability equality is closer than ever to being realised, thanks to his resilience in the face of overwhelming challenge; a hallmark of his approach to life thus far.

My Vision for Ability Equality | BY DR PAUL HARPUR

My Past Vision

When I lost my eyesight in a train accident at the age of 14, I realized you do not need sight to have vision. As a Paralympian and internationally competitive athlete I learned about creating a vivid vision. To create my vision, I first imagined what I wanted to achieve in the next 2 to 4 years. I did not imagine the outcome of standing on the podium, but instead the process that got me to the medals:

What would I eat on the day of the race and do before the race?What would the starting gun and crowd sound like?

What would it feel like when I was coming home in front?

How would it feel to have the adrenalin pumping through my system?

How would I pound my feet at the end of my burning legs?

How would I manage the moment to ensure I kept focused?

I imagined this experience in detail every day. Every time I trained, I imagined the sound, smell, taste and feel. I was there in that moment daily.

I shared this vision with my family friends and supporters. For me it was a reality. Then when the finals came in the 400m in the 2003 world titles I made this vision a reality. I ran the race and won silver. I ran the race of my dreams in the 2006 Commonwealth Games and achieved a career best performance. This approach has successfully translated to my academic career and can also be translated to my vision to improve society.

My vision is for a world where it is not us and them but just us.

There will always be a need for disability specific interventions, but Ability Equality will only be achieved when there is strategic commitment to designing in everyone in society, regardless of their abilities or disabilities. My vision is to align the frameworks that guide society with the new disability human rights paradigm swept in by the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. These frameworks can be designed by a single organization, across an industry, by local or national law makers, or situated in the international law arena. This might seem impossible, but remember, impossible is only a few characters from possible.

My vision for Ability Equality in Universities

As an academic and leader in Ability Equality I see universities as one powerful means of driving broader change. Universities train the leaders of tomorrow, provide the leaders of today employment and are uniquely positioned to produce high quality critical, operational, transformational and regulatory research to support a vision of ability equality.

In five years, we could be in a place where universities are welcoming of everyone. I like to illustrate my vision for Ability Equality by telling the story of five friends. A story that has not happened yet, but in five years could and should.

Five friends across the lifespan: the test for ability equality

Five students arrive for their first day of university. They all enter the campus office to collect their student cards, they all are assigned rooms, they collect their keys and cheer as they move into the university dorms.

These five students become friends and find they are all in the same course. They head off to social functions during orientation week and plan to go to the first lecture together.

At the first lecture the professor speaks of resources and course outlines and group work.

The five friends work together, get all the resources at the same pace, can access the individualised supports they require to realize their potential and after the first week of classes go to a dinner and wine bar on campus.

The fact one of the friends is blind, one is a leg amputee, one is in a wheelchair, one has autism and one is able-bodied, is irrelevant.

The university has embraced the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and its paradigm shifting model and has implemented systems to enable full ability equality. Ability equality means every student has an equal opportunity to succeed. Obstacles that disable people with impairments are actively sort out by operational and leadership teams and removed.

Some students and staff will have additional support, targeted advocacy and leadership training, but most importantly the system ensures that people can be judged upon their commitment and merits and not upon their disabilities.

Before the five friends commence, people with expertise have assessed the barriers, removed them, tailored programs to provide the support required by all students, regardless of their individual needs. All students have mentors in the academy and professions with the same disability as them and can see university leaders across the sector who have a disability. They can see their diversity counts, as it is counted in university and national statistics and inclusivity is mainstreamed through university life. They can see they have equal opportunities to become academics, professional staff members or leaders of universities.

Imagining how these five friends experience university life can be applied across their life experiences: to their careers, their experiences using public transport, accessing a library and its resources, using health care, finding a home or getting married and having children.

My role in this vision

I have a vision, but I also vividly imagine how this might apply to me. While this has not occurred yet, I believe it will.

In 2019 I was privileged to be nominated and be awarded a citation as part of the Outstanding Contributions to Student Learning, as part of the Australian Award for University Teaching program.

The citation, for "outstanding leadership in translating disability strategy into a vision of Ability Equality and core university business”, was awarded just prior to my 2020 Fulbright Future Scholarship, where I had the honour of spending time working with other experts at the Harvard Law School.

I am building upon these successes and I can imagine a future where my vision has become a reality. I can imagine how the press release would read following the launch of the “Universities Australia Disability Inclusion Group” and the appointment of Professor Paul Harpur as its first chair in 2025.

This press release would explain that the Universities Australia Disability Inclusion Group, formed and supported under Universities Australia’s Disability Action Plan, is fully funded by partners and competitive grants.It would outline the Group's aim to provide strategic advice and high-level guidance to Australian Universities and their governing bodies, relevant associated organisations and state/territory-based networks committed to realizing Ability Equality across the sector.

Further, it would detail more broadly how the Group's goal was to improve the representation of people with a disability, both academic and professional, throughout universities, including at executive levels of university leadership and governance.

This group would:

Perform and support research to develop theoretical and practical resources to realize Ability Equality in the higher education sector.

Sponsor/commission targeted investigations around strategies to address systemic barriers to advancement of persons with a disability through university ranks to executive level in the Australian university sector.

Actively promote and support university-led initiatives to enhance the representation of persons with a disability across the higher education sector, including in executive leadership roles.

Provide evidence-based briefings to relevant high-level groups such as Government, the Chancellors, Vice-Chancellors, Deputy Vice-Chancellors and other senior university stakeholders.

On request, provide advice and guidance to universities and their governing bodies, associated organisations and state/territory-based networks on initiatives they have planned or are implementing to assist the development of persons with a disability.

Help collect, collate and share information and good practice relevant to international and sector-wide strategic responses to Ability Equality in universities.

When we say “yes” to ability equality, we enable everyone in our community to innovate, inspire and lead.

- Dr Paul Harpur, Fulbright Scholar, University of Queensland

They Might Be a Liar, but They’re My Liar

BY SARA JAMES

Briony Swire-Thomson is a clinical psychologist whose field of research is so new, she’s helping to write the map.

“You’re completely in the wild west.”

Swire-Thomson studies “fake news” – how it spreads, and why we find it so enticing. The associate research scientist at Northeastern University’s Network Science Institute says its vital to help people separate “fact” from “fake” when it comes to the COVID-19 pandemic and the 2020 US election.

“One of the biggest differences between political disinformation and health [disinformation] is that the risk to people’s livelihoods and mortality is very real… we are only beginning to understand the ramifications.”

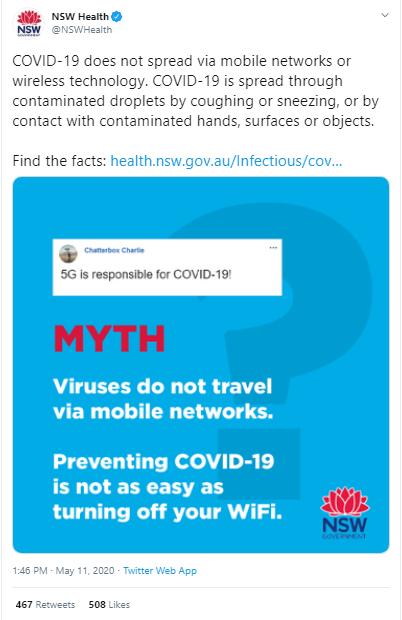

As the COVID-19 pandemic spread, governments have warned against ingesting bleach and dismissed as piffle a conspiracy theory that links the Coronavirus to 5G, including on Twitter: But misinformation seems to spread as quickly as the virus. Social media giant Facebook reported that during the month of April, it placed warning labels on some 50 million pieces of misleading content.

Why do we fall for it? Swire-Thomson says one reason we’re susceptible is that we humans, like nature, hate a vacuum.

“People are notoriously bad at understanding, ‘well we just don’t know yet….’ A lot of mis- and disinformation has rushed in to fill that void.”

Swire-Thomson, who studied political misinformation as a Fulbright Scholar at MIT, says an astonishing 80% of misinformation can be traced back to 0.1% of people.

“We call them Cyborgs,” she notes.

This fake news ricochets around the internet, gaining traction and credibility, because we share it with our friends.

The good news? When confronted with proof that they’d shared misinformation, Swire-Thomson says people will accept a correction, especially if the correction is kind.

“People updated their belief remarkably well.”

But there’s a catch.

“What we found was that didn’t change people’s voting intentions. People would acknowledge that these politicians were saying inaccurate statements but voting intentions would stay absolutely stable.”

She notes that this is true across the political spectrum.

Which might explain why Swire-Thomson’s 2019 article in Political Psychology about the 2016 US presidential election had the provocative title, They Might Be a Liar, but They’re My Liar.