31 minute read

Higher Education in a Post-COVID-19 World

Higher Education in a Post-COVID World

Dr Gwilym Croucher and Professor William Locke

The COVID pandemic is magnifying existing pressures for universities but is also providing new possibilities. How universities respond will determine their future. What the coming months and years will mean for higher education in Australia and around the world depends on the response of governments and providers to the unfolding disruption caused by the coronavirus pandemic. While the speed of developments during the pandemic makes prediction fraught, past experiences of similar economic, political and social ‘shocks’ to the provision of higher education in advanced economies provide some hints to where we might be heading. The pandemic is magnifying existing pressures for universities but is also providing new possibilities.

We outline here some trends and their implications for Australian higher education and public policy.

Diminishing student capacity and preference for travel to undertake international education

For many students their preference for traveling to another country for study will diminish because leaving their home country for study becomes perceived as less safe. Growing nationalism may also promote studying domestically, exacerbated by the relationship between a home country and the one where students study. This will be framed by shifting geopolitical tensions that are almost entirely divorced from people-to-people or educational relationships. Moreover, many students will face stricter rules and regulations in gaining entry to a chosen host country for study and, possibly, poststudy residence and employment.

For Australia, this means the international student market may recover somewhat but, at best, slowly, and the incentive for studying abroad will be much diminished because of the perceived risks. This will likely have most impact on laboratory and practice-based disciplines, some of which have high proportions of international students. The impact could also be particularly acute for business and commerce disciplines, which have the most international students and are usually in the higher margin range of offerings. Australia may be better positioned to attract students than the two other large destination countries, the UK and U.S, if there is continuing success in Australia mitigating the worst effects of the pandemic. China and one or two other Asian countries may take advantage to retain students who might have gone abroad to study, as well as attracting more international students from the region and beyond. Much depends on how and when the government is in a position to lift travel restrictions. Yet, as international education has particular cultural dimensions and is not just another trade in services, sociopolitical factors may inhibit recovery of the market even if the government does open the borders. The reputational effects following the uneven initial response have yet to be fully known. So, too, is the impact of the sudden shift to online teaching and learning and how engaged international students continue to feel, especially when those students already in Australia start to return to campus.

There are uncertain prospects for university-delivered transnational education, too, such as at international branch campuses. Despite Australia’s success over several decades, there may be little practical option to grow new largescale provision overseas in the immediate term. Existing markets may become increasingly challenging as more countries and multi-national companies look for new opportunities outside their own markets. For Australian international and transnational education, the future may be uneven. One factor affecting this is the growth of online study.

Growing student acceptance of online study

Many, if not most, large institutions in major higher education systems have made this shift to more online study with a likely growth in students’ acceptance of it, even if it does not remain their preference. Yet, the perception of online course delivery as inferior to face-to-face delivery will likely remain for many students, as will concerns that it is not equivalent or equally valuable to face-to-face no matter how well it is done.

"The global

For many the cognitive learning may be deemed to be as good but not the rest of the educational experience. Some disciplines have not been able to transition as easily, especially those relying on experiences out of the classroom, nor can some cohorts of students transition as well due to limited access and capability of technologies.

Australia is unevenly positioned to respond. In many ways its universities have been at the forefront of online education provision and some have developed sophisticated modes of delivering wholly online programmes. For instance, universities now partner with MOOC (Massive Open Online Courses) platforms (e.g. Coursera, EdX, FutureLearn) or dedicated online programme managers (e.g. 2U, Wiley, Pearson, Keypath Education) to support wholly online programme delivery. Australia’s proximity to key markets (in the Asia-Pacific especially) and a shared time zone with Asia are advantages in terms of enabling synchronous communication, service and support. For example, strong demand for English language courses continues, particularly from some Asian countries, such as Vietnam.

Yet the online capacity that has been built in this crisis will allow international brands and leading universities to offer courses without the need for residence. An increasingly competitive landscape raises questions about which areas of demand universities should focus on and what are realistic expectations about demand and growth. There are also challenges in implementing innovative pedagogies for wholly online courses, particularly when some students will continue to prefer a more traditional, classroom approach. Nonetheless universities can benefit from economies of scale in the development of online delivery across their offerings.

Diminishing attractiveness of certain degrees and programs

Deteriorating economic circumstances in most countries and growing unemployment affect decisions about what to study and whether it will provide financial benefit and employment security in the future. While recession often means that study is an attractive option for those unemployed or underemployed, it also means students are more likely to select courses perceived to lead to professional entry or to enhance their employment prospects.

The global lockdown and disruption to many industries may affect the future trajectory for some, such as accelerating and amplifying use of automation, data analytics (including Artificial Intelligence) and online systems, and so reduce the requirements for some skills sets and degrees, such as accounting.

For Australia, there may be less domestic and international student demand for courses not perceived to lead to professional entry or to enhance employment prospects, such as arts, some pure science and commerce degrees such as marketing. Australian providers that specialise in professional and vocational subjects may be well placed to accommodate the shifts in student demand.

These trends have significant implications for universities and higher education policy, which we examine below, as well as compounding factors including the diminishing capacity for governments to invest in education and research and the reorganisation of universities and their workforces.

Greater reliance on areas of expertise deemed relevant to economic and social recovery

Governments and other actors may come to rely on areas of expertise seen as relevant to economic and social recovery as the scale of the social and economic disruption is akin in many crucial ways to the Great Depression and is the largest outside of wartime, meaning that expertise becomes a valuable part of the response, as it has been for previous crises. While genuine debate will continue as to the best response, the differing responses to the pandemic to date in different countries shows the importance and effectiveness of expert advice for those governments that have followed it. Many news media organisations have given a high profile to expert commentary, in contrast to disinformation spreading on social media.

The importance of experts in advising governments amplifies the status of science, expertise and research as bedrock of the evidence-base for policy. As universities are central providers of expertise and research, their social, economic and public policy purposes are clear, as academics with expertise in infectious diseases, public health, mental wellbeing, social media, economic recovery, etc, are being seen as important sources of advice for ministers and premiers. The role of expertise in assisting recovery and reconstruction presents an important opportunity for universities and their academics to lead public debates and shape outcomes on multiple fronts.

However, there are risks to university finances that may make this harder.

Diminishing capacity for governments to invest in higher education and research

Governments in many countries will have less capacity to invest in higher education. The public policy response to the coronavirus has seen governments outlay huge sums for health, social and employment programs, as well as for other measures. It is likely that these stimulus and safety net programs will need to be funded for several years following the initial pandemic. Along with reduced taxation revenue due to recessions across most advanced nations, governments are in a difficult position as citizens demand that areas of public policy and public service delivery other than higher education, such as healthcare and school education, be prioritised.

In Australia there will likely be little scope for additional government support for higher education. While it is possible government will need to consider radical policy options to focus public outlays, these would cause massive disruption. In the immediate term there could be significant disruption from the introduction of higher student fees, targeting equity and other support programs to particular institutions, mandating student contributions differentiated by mode and level of study, separating research funding from teaching funding even further, and funding some institutions at a reduced rate to only teach. More certain is that universities will employ a range of measures to reduce outlays in the immediate term and will reconfigure their offerings and business models.

Reorganisation of universities and their workforces

The significant disruption to operations during 2020 means that many casual staff and those on short term contracts may be forced to seek employment outside the sector.

Changing student demand for particular courses, reduced activity in some areas and the shift to online may mean universities require more staff in some areas and fewer in others, especially where there is a shift in the skills requirements. Over the longer term this may mean the nature of much academic work may change, with larger roles played by learning designers, educational technologists and study support staff, for example. We may even see the rise of global academic ‘superstars’ going freelance and offering content to a number of universities.

There is the risk that, as Australian higher education reduces its workforce, the next generation of academics and researchers are lost to other careers and that they will need to be replaced to avoid a permanently reduced capacity. Equally, career progress of early career academics could be stalled due to the lack of opportunities to develop their research and move between universities, including internationally. There is a case for prioritising support for the next generation of teachers and researchers.

Uncertain future opportunities for research and collaboration

The prospects for future opportunities for research collaboration are uncertain. There are uncertainties about how the global research system will cope with restricted international travel and the shift to online communication may inhibit some forms of collaboration and will reduce opportunities for visiting researchers. The forced use of teleconferencing for collaboration may mean that Australia’s distance from Northern America and Europe is less of a disadvantage as face-to-face collaboration ceases. Both philanthropic donors and government programs that support the generation of new ideas and international collaborations, such as Horizon Europe, may have diminished funds and capacity to support new projects.

Research associated with dealing with the pandemic and post-pandemic recovery will likely be the focus of many academics, and so will present new opportunities.

The growth in international collaboration may slow and stagnate, with long term implications for the pace and direction of advancement in some fields. There will be an opportunity for Australian researchers as online communication ‘levels the playing field’. For Australia, like other countries, collaborators may come to rely more heavily on government support in their own countries and advancements in knowledge may be more tied to where researchers are all located in a single country than at present.

There will potentially be fewer students traveling for international doctoral study because of difficulties gaining visas and entry and where universities cannot afford to offer the same level of internally funded scholarships for international students. Australian higher education could benefit from reduced provision of doctoral programs at international competitor institutions. Yet it may also suffer as students either decide against, or are not allowed to, travel for study. The combined impact of the pandemic on international research students and the reduction in fees from all international students may have a serious knock-on effect on Australia’s research and development capacity.

Policy questions

The possible trends summarised here suggest a range of outcomes and questions for Australian higher education. The international market may be slow to recover, and a number of strategies for growing revenue and activity, such as philanthropy, transnational education and commercial research contracts will be less viable. Some difficult public-policy choices become more likely and are contingent on the return of the international market.

This begs the question of what is a realistic funding model that covers the teaching component of university spending where universities come to rely more heavily on public funding in Australia? And of how many universities might face severe to catastrophic financial problems? Depending on what the future holds this may present hard choices for governments.

Originally published on John Menadue – Pearls and Irritations

The DANGERS of DISINFO

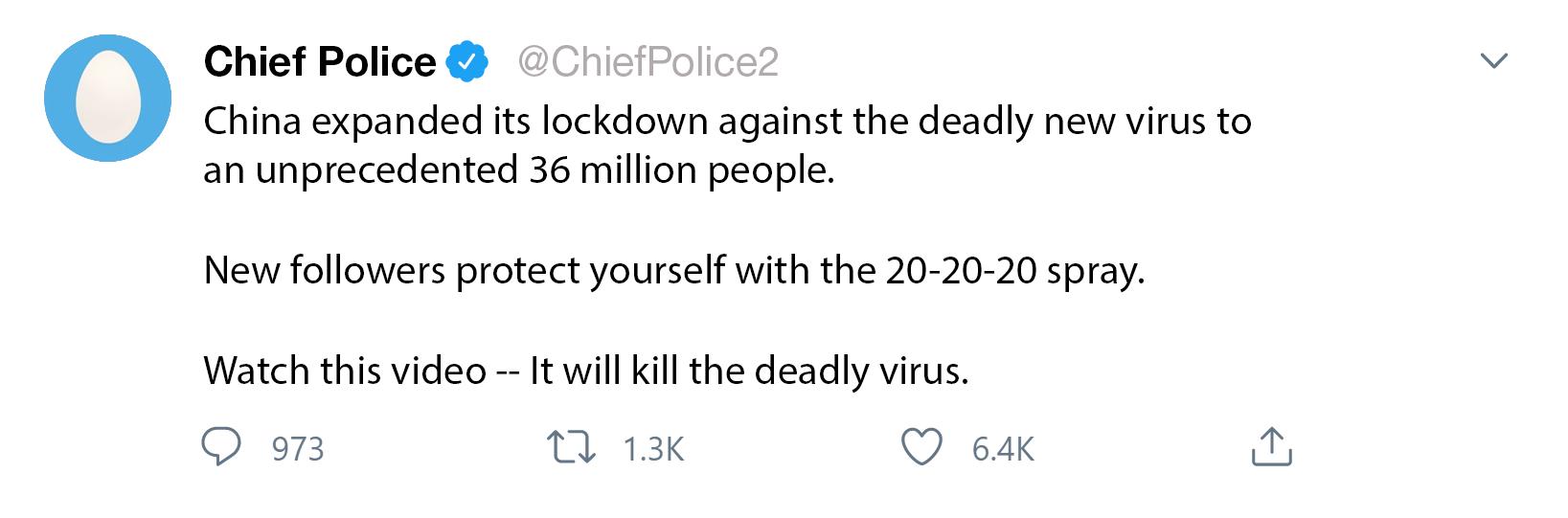

This Tweet, and the YouTube video referenced have both been scrubbed from the internet, and ChiefPolice, a prominent anonymous conspiracy theorist Twitter handle with close to 20,000 subscribers, has been suspended – all for violating guidelines aimed at preventing the spread of dangerous or harmful misinformation.

“20-20-20 spray” is Miracle Mineral Supplement (MMS) – an extremely toxic solution of chlorine dioxide touted by grifters and frauds across the globe as a miracle cure-all for everything from HIV to autism.

“It cures nothing.” Said Jim Humble in 2016, a decade after self-publishing the book that first coined the MMS name, The Miracle Mineral Solution of the 21st Century.

There are always groups trying to exploit any "

Worse than curing nothing, MMS can actually cause life-threatening injuries if ingested.

“It’s a bit like drinking concentrated bleach.” According to Naren Gunja, director of the New South Wales, Australia Poisons Information Centre.

Humble had performed no clinical trials, and had no scientific evidence to back up the claims in his original book.

Yet thousands of people liked and shared ChiefPolice’s tweet about MMS before it was taken down, and the YouTube video explaining how to concoct or buy the deadly elixir already had tens of thousands of views, despite being based on disinformation that had been debunked and re-debunked many times over the past ten years. This is why disinformation can be so dangerous today: its presence online is prolific, it spreads quickly, it’s difficult to find and fact-check in realtime, and the most successful examples of it tend to reappear, even years after being corrected. It also seems to propagate most during times of crisis or uncertainty.

But why? Who benefits when swathes of people poison themselves by gargling bleach? The answer to this is rather complicated.

“There are always groups and people who are trying to exploit any crisis or opportunity to try and push their agenda, including by propagating questionable information,” said Arjun Bisen, a Fulbright Scholar who studied disinformation at Harvard University, and now works as an information quality expert in the U.S. tech sector.

“This pandemic is no different, and in fact, the stakes are much higher.”

The motives for people spreading disinformation online generally fall into four broad categories – ignorance, spite, profit, and political benefit. The first two warrant no real analysis – some people will share an entirely erroneous fact online simply because they find it interesting and don’t realise that it is untrue. Some people will go out of their way to confuse or mislead others with misinformation online, simply because they enjoy doing so (see trolling).

Others, however have more concrete objectives, and these are arguably the most dangerous actors.

This pandemic is no different, and in fact, the

stakes are much higher. "

A Silver Bullet for COVID

In some ways, the advent His diatribes against of the internet made the nefarious activities life rather challenging of concocted enemies for career-conmen and such as the Deep State purveyors of snake oil inevitably end with a pitch – the ability to simply for a dubious safeguard Google search claims in the form of a dietary to prove or disprove supplement or patented their veracity made it device, conveniently sold difficult to get away with through his online shop, claiming that a miracle InfoWarsLife. tonic actually worked. With greater access to expert information, people become more sceptical and discerning. Last month the U.S. Food and Drug Administration issued a cease and desist to Jones for claiming that a colloidal silver toothpaste However attacks on expert would prevent his viewers opinion from a variety of from catching COVID-19. sources (including current world leaders) combined with the growth of closed loops and echo chambers via social media has opened the door for a new kind of conman to operate – one who doesn’t need to "The patented Nano Silver we have, the Pentagon has come out and documented, and homeland security have said this stuff kills the whole SARS corona family, at point blank range." go door to door anymore and can find new audiences with a few easy clicks. He said, in a video posted March 10. Alex Jones is one of these. His website, InfoWars, peddles misinformation and far-right conspiracy theories to a massive audience of nearly 10 million visitors/month. In another video Jones promoted the products as a way to boost users' immune systems, saying that "regardless of how deadly this virus is … if it kills you, it's bad news." Laboratory tests of products sold for premium prices on InfoWarsLife have demonstrated that the contents, while not harmful, contain quantities of active ingredients that are "too low to be appropriately effective" and claims to their positive health benefits are highly dubious.

During court proceedings in 2014, Jones revealed that his site generates annual revenues of over $20 million.

At the time of writing, Jones’ name was in the headlines again for his assertion that should society collapse, he would happily eat his neighbors.

Jones is one of the most prolific cyber-grifters around, but he is by no means the only one.

There are literally thousands of actors seeking to profit off of the uncertainty and lack of authoritative information on COVID-19.

In March Kenneth Why, then, can these hoax “For example, if you do Copeland, a prominent U.S. cures continue to generate a web search for ‘does televangelist, claimed that profits, when their broccoli cause COVID?’ you he could cure COVID via efficacies have already would only be presented "spiritual healing" – viewers been disproven? with very low quality needed to touch their television screens for the treatment to be effective. In a previous show, Copeland had called One issue is that this disinfo can continue to circulate in closed loops, or echo chambers where expert opinion doesn’t information, because there are no authoritative or credible sites that are actually commenting on this point.” COVID a ‘weak strain of easily penetrate. So tech companies are the flu’ and that fear of it was putting faith in the power of the devil. Both broadcasts encouraged donations from viewers. Copeland’s net worth is over $300 million, and his tax-exempt church owns The InfoWars network is a prime example of this, where the audience is rarely, if ever, exposed to legitimate scientific expertise (and are also to some extent inoculated against expert opinion having to play catch up – it’s impossible to dispel every possible myth in advance, so they essentially need to play whack-a-mole with these hoaxes as they gain traction or go viral one-by-one. five private jets. through consumption “Tech companies are Individual actors are also lining up to profit from phoney COVID treatments. Researchers from the Australian National University in April found hundreds of COVIDrelated products circulating online, including reputed animal-trial vaccines, blood from purported COVID recoverees, and vials of hydroxychloroquine – the of the site’s conspiracy content, which regularly attacks scientific institutions). Another issue is that disinfo thrives in ‘data voids’ where there is no scientific discussion taking place. “A data void is where there is no authoritative information in a particular narrative,” said Arjun Bisen. actually becoming much better at identifying these data voids, and helping users navigate them by either providing more context around the issue, or enabling better access to more credible sources such as the CDC, WHO, or even doctors on the front line.” The old adage about leading a horse to water ‘miracle cure’ speciously comes to mind, though. promoted by the U.S. president. There are literally thousands of actors seeking "

They might be a liar, but they’re MY liar

So what of the politically-motivated disinfo actors? Well, they could potentially be the most dangerous of all. They have better access to resources and authoritative voices, and their true motives are often murkier.

Coordinated, state-sponsored disinfo campaigns are not a new phenomenon – propaganda has been deployed by Western and non-Western governments alike for decades in efforts to modify public opinion, both at home and abroad. There is obvious benefit in having the power to control the narrative of a political wedge issue, either for partisan, diplomatic, financial, or electoral gain. Briony’s new research focuses on COVID, and she agrees that data voids are facilitating a greater spread of disinfo than ever before, particularly in political spaces. “What makes this a really tricky time to be studying COVID misinformation is that there’s not a lot of what we know to be true. “In a way it’s a perfect storm – people are notoriously bad at accepting ‘we simply don’t know just yet’ as an answer, so a lot of mis and disinformation can rush in to fill the void before science catches up.” State actors have been taking advantage – the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI) found that Chinese Communist Party (CCP)-linked social media accounts had been exploiting tensions with the WHO to cast their response to the pandemic in a positive light, and instigate unrest in Taiwan. Their legitimate diplomatic channels have also been propagating conspiracy theories about the origins of the COVID virus. Kremlin-linked news organisations, too, have seized upon confusion to foster negative perceptions of Western responses to COVID, undermine public trust in national healthcare systems and control the narrative to their benefit. Even some Western leaders have been accused of deliberately spreading misinformation to confuse or obfuscate the issue. Fulbright Scholar Briony Swire-Thompson has been studying the psychology behind disinformation for over ten years. Her 2017 research paper, They might be a liar, but they’re my liar, was focussed on disinformation in the political sphere, and it suggested that even when erroneous talking points from political figures were fact-checked, support for the politician continued relatively consistently.

“We found that people are great at updating their opinions when provided with new information, however their voting preferences tend to remain completely stable. We found this replicated on both

the political right and the left.”

The 'GREAT AWAKENING'

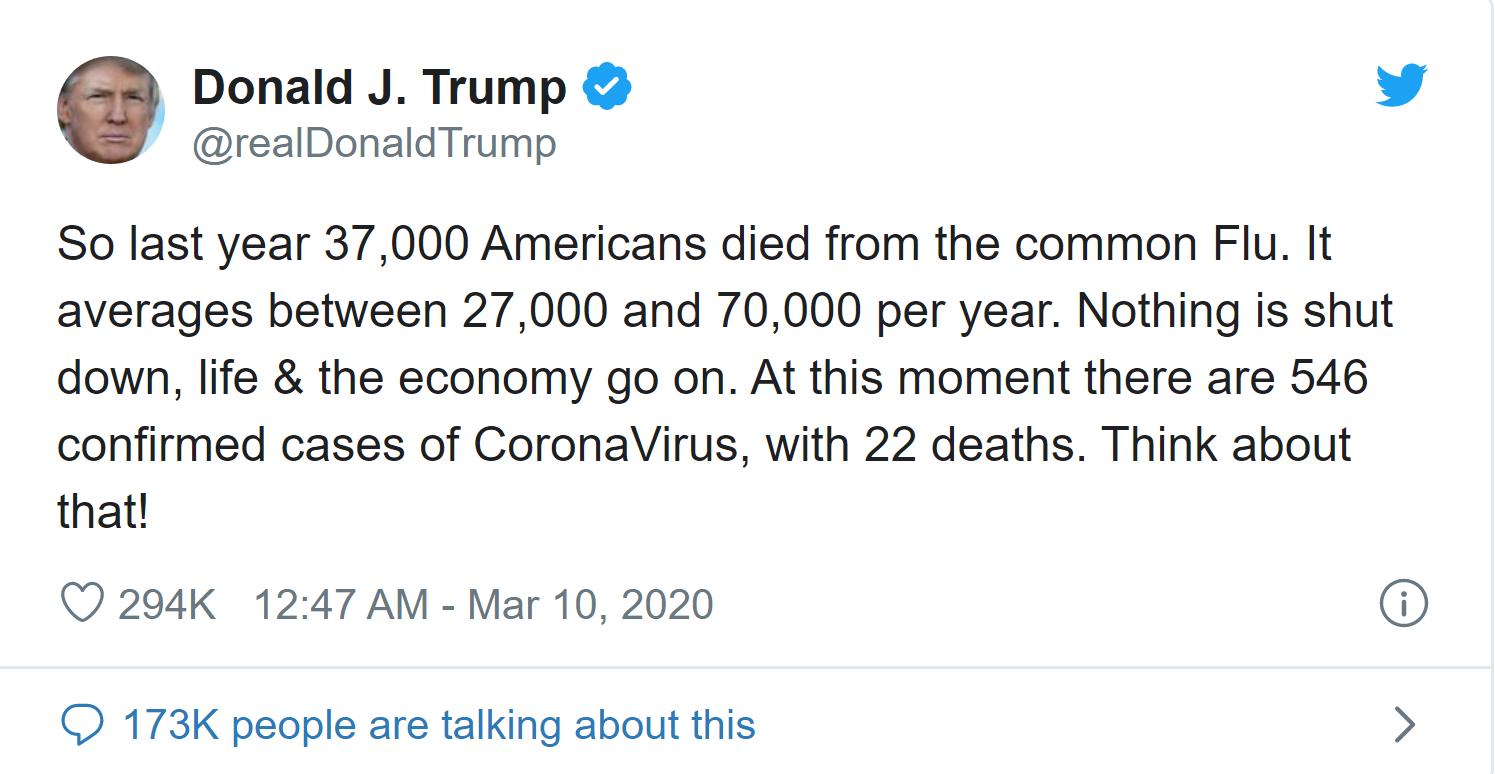

Why would a leader be deliberately providing inaccurate information about a deadly pandemic, and confusing or contradicting their own administration’s response? The explanation will vary depending on who you ask.

If you ask Trump why he recommended injecting disinfectant to see if it could cure COVID, he’ll tell you that he was being sarcastic to troll a hostile media pack. If you ask the media, they will explain that he has a history of freewheeling, streamof-consciousness rants during press conferences, and was simply riffing via his extremely limited knowledge of medicine.

If you ask a follower of QAnon, a rapidly growing U.S. conspiracy network, they’ll tell you that it’s all part of the plan.

QAnon is a prolific group of anonymous conspiracy theorists founded upon the idea that an omnipotent, malevolent government entity, the Deep State, are the puppet-masters behind everything from global warming to autism-inducing vaccines, and whose goal is to suppress the general public through propaganda and mind control.

‘Q’, the leader of the movement, is supposedly a high-ranking member of the U.S. military who communicates purported 'classified information' to his followers. ‘anons’, via encoded ‘intel drops’ – cryptic messages, sometimes just a few seemingly-random phrases sent out via Twitter or through encrypted messaging apps.

The basic narrative of Q's 'intel' suggests that President Trump is engaged in some form of clandestine war with the Deep State, and that his impeachment, as well as the preceding Special Counsel investigation, are evidence of Deep State retaliation against him.

Q's plot is the type of convoluted that would make Dan Brown blush. It brings in a variety of familiar characters--many of whom have starring roles in previous conspiracy features such as Pizzagate- -and conveniently, all of whom sit at the top of Trump's list of enemies. The Clintons (of course) play major antagonists, who lead a cabal of Hollywood cannibal/ child molestors. Various branching narratives have them arranging for the murder of Jeffrey Epstein, working with the Ukraine mafia to implicate Russia in 2016 election meddling, and dispose of the allimportant email server.

Supporting roles include former President Obama, former FBI head James Comey, and Presidential candidate Joe Biden, all of whom are implicated in a plot to bring down the President.

Even Australia has a cameo, as UK High Commissioner Alexander Downer plays a doubleagent who frames a member of Trump's campaign team and feeds damaging information to the FBI.

On the 'protagonist' side, convicted criminals such as Gen. Michael Flynn (who pled guilty to lying to the FBI about his contact with Kremlin officials), and Roger Stone (also convicted and jailed for providing false statements, as well as witness tampering) are portrayed as war heroes who became collateral damage in the Deep State efforts to remove a lawfully-elected president from office. Trump has amplified a number of these claims, and retweeted various QAnon twitter handles, despite the movement being declared a domestic terror threat by the FBI in 2019.

Why would President Trump be promoting wild conspiracy theories that undermine his own administration?

Well, for him the benefits likely outweigh the risks. The idea that he is waging a battle against an unseen, unknown, nefarious institution is of obvious appeal to his base, and undermining faith in the justice system (yes, even his own justice system) actually works in his favour.

As of 2019, there were 30 ongoing investigations into the Trump Administration and Trump Election Campaign looking into issues such as potential foreign influence, hush money payments, abuse of power and obstruction of justice. Destabilising the agencies tasked with carrying out these investigations increases the chances that Trump could shrug any impending convictions.

Absolving all of the aforementioned Trump allies of their own convictions is also of immediate and obvious appeal, and helps vindicate his longstanding assertion that none of them did anything wrong ('no obstruction, no collusion', 'total exoneration', et cetera), and that his judgement was always perfect ('the best people').

So what does QAnon get out of portraying Trump as a hero of the people?

Well, this is a little murkier, however it’s worth noting that many of Q’s ‘intel drops’ are only accessible via encrypted Q apps. Until recently, if you searched for the letter ‘Q’ on the Google Play store website, the top result was for the ‘Q Alerts!’ app, which purported to provide ‘anons’ with “the most up-to-date info for sharing and researching Q”.

Apps such as this were finally removed in May 2020 for violating Google's policies against "harmful information". So how do we combat disinfo and make sure that the information we're consuming is accurate? Arjun Bisen stresses the importance of being conscious of where we get our news, and why. "Misinformation really thrives on our biases, and targets divisions to stoke our emotion and drive further disunity. We need to make sure we're not just blindly trusting any one source for news." To do this, he has a cheat-sheet to help people become their own factfinders-in-chief: Master Good Consumption Habits We all know eating a well-rounded diet is crucial. What we “consume” online is also important. In a global pandemic, Bisen says succumbing to misinformation or disinformation could be dangerous for your health. Seek out the news equivalent of green, leafy vegetables: legitimate sources. Triangulate Information Intake Make it a practice to check three sources. For added certainty, check a few more. Then, just for the heck of it, check a few — You get the idea. Before removal, 'Q-Alerts' alone had over 10,000 downloads, and was rated 5 stars. The price:$4.89.

Prior to their Twitter suspension, ChiefPolice2, responsible for the tweet at the beginning of this article, posted prolifically about Q, and the ‘Great Awakening’ that would follow Trump’s crusade against the Deep State. These were alongside tweets that attempted to sell poisonous bleach spray to hapless followers, and other endorsements of theories and products sold by InfoWars and Alex Jones.

You know what they say about birds of a

Becoming your own Factfinder-in-Chief | BY SARA JAMES

feather. Beware the Dangers of the “Data Void”

It’s easy to stumble into a data void during unprecedented, uncertain and alarming situations — such as a new virus that causes a global pandemic. Conspiracies and misinformation lurk in these murky waters. Be vigilant. Cross-check data with multiple reputable news organisations.

Guard Against Your Greatest Vulnerability

No matter who we are or where we live, one thing makes all of us more vulnerable to misinformation. If it fits our bias.

Bisen spent seven years as a diplomat. He navigated geopolitics and trade discussions and drafted Australia’s cyber strategy. He knows it’s crucial to hear from multiple points of view. Open your network to those who disagree. And pay extra attention when information is provocative.

And Remember…

There are always groups which seek to exploit divisions and inflame tensions. Such groups thrive during challenging times, Bisen warns. To foster understanding and solve problems, it’s important to share accurate information – whether it’s on a family email chain, or to the world at large.

Down

2......The prevention of an increase or spread of something, especially nuclear weaponry. 3......Something that combines contradictory features or qualities. 5......Of, or relating to, the brain or the intellect. 10.....A milky fluid found in many plants, such as poppies and spurges, which exudes when the plant is cut and coagulates on exposure to the air.

Across

1......A feeling of worry, nervousness, or unease about something with an uncertain outcome - see eg. the latest season of Game of Thrones. 4......The scientific study of the properties, distribution, and effects of water as a liquid, solid, or gas on the Earth's surface, in the soil and underlying rocks, and in the atmosphere. 6......Meringue-based cake of disputed Australian/New Zealand origin, named after a Russian ballerina. 7......Concerning the role of genetics in the development and function of the nervous system. 8.....The the prevention or treatment of disease through substances that stimulate an immune response. 9.....An animal that moves fertilising elements from the male anther of a flower to the female stigma of a flower.

December Solutions: Down: 1. Los Angeles 2. Portugal 4. Ziggurat 5. Organic 6. Harp Across: 3. Aesop 7. Paris Hilton 8. Snotted

Donate to Fulbright

The Fulbright Program changes lives and transforms careers in its support of binational cooperation and cultural exchange. You can support us in our mission by sponsoring a scholarship or making a donation to one of our alumni or state scholarship funds. Please see overleaf for more information.

Salutation Given Name Family Name

I would like my donation to remain anonymous

Donation Amount I would like information on making a bequest or annual donation

Payment Details:

Online (preferred option) Please navigate to the Donate page on our website: www.fulbright.org.au/donate

Credit Card Visa | Mastercard (circle one)

Cardholder name

Card number

/ Expiry date

Cardholder signature Contact number/email address

Electronic Funds Transfer I have made an electronic fund transfer to the following account: Australian American Educational Foundation St George Bank, BSB: 112-908 Account: 001365589

Cheque Enclosed is my cheque payable to the Australian-American Fulbright Commission CCV

The Fulbright Commission is specifically legislated as a deductible gift recipient (DGR) under section 30-25(2), item 2.2.28 of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1997. Donations of $2 or more supporting Fulbright Scholarships are tax-deductible.

To find out more about supporting a Fulbright Scholarship or making a bequest to the Commission, please contact us via 02 6260 4460 or send an email to fulbright@fulbright.org.au

Fulbright Scholarship Funds (please select one) 70th Anniversary Scholarship in honour of Jill Ker Conway

Dr Jill Ker Conway AC is one of the most outstanding alumni of the Australian-American Fulbright Program. In this 70th Anniversary year, the Commission is seeking to endow a Fulbright scholarship fund in her honour. Dr Jill Ker Conway AC grew up in the Australian outback and in 1960 she won a Fulbright scholarship to study at Harvard, where she earned a PhD in History. Jill was the first female vice-president of the University of Toronto, president of Smith College and chair of the property group Lendlease. She authored bestselling memoir books The Road from Coorain, True North and A Woman’s Education. In 2013 she was both awarded the National Humanities Medal by President Obama and appointed an Honorary Companion of the Order of Australia by the Australian Government for “eminent service to the community, particularly women, as an author, academic and through leadership roles with corporations, foundations, universities and philanthropic groups”.

Fulbright State Scholarship Funds

Fulbright state scholarships aim to encourage and profile research relevant to each state/ territory, and assist in the building of international research links between local and U.S. research institutions. These scholarships were established by state governments, companies, universities, private donors and other stakeholders. Endowed state funds currently exist for New South Wales, Western Australia, South Australia, Victoria, and Queensland. I’d like to donate to the State Fund.

Fulbright WG Walker Memorial Alumni Fund

The Inaugural President of the Australian Fulbright Alumni Association was Professor Bill Walker, a two-time Fulbright awardee. It was his energy and enthusiasm that was the driving force behind the establishment of the Association. To acknowledge Bill Walker’s significant contributions to the Association and the Fulbright program, it was decided in 1992 to fund the WG Walker Memorial Fulbright Scholarship in partnership with the Fulbright Commission. The fund sponsors one Australian scholarship each year, awarded to the highest-ranked postgraduate candidate.

Fulbright Coral Sea Fund

Established in 1992 by the Coral Sea Commemorative Council to recognise the 50th anniversary of the Battle of the Coral Sea, this scholarship was designed to acknowledge the friendship, cooperation and mutual respect which has developed between the United States and Australia since the Battle of the Coral Sea. Each year, recipients of the scholarship research identified problems or opportunities relevant to Australian business or industry, through 3-4 months of study in the United States.

Salutation

Scholarship Title

Home Institution

Address

Update your details

Given Name Family Name

Award Year

Host Institution

Contact Number

NSW

QLD

VIC

WA

SA

NT

TAS

ACT

Fulbright State & Territory Sponsors

In-Kind Supporters

Core Sponsors

Fulbright Scholarship Sponsors

Scholarship Sponsors

Visit Fulbright.org.au to apply for a scholarship

Annual Deadlines:

Australian candidates (all)........................4 February – 6 July

U.S. Postdoctoral/Scholar/Distinguished Chair candidates........4 February – 15 September

U.S. Postgraduate candidates....................31 March – 6 October

Fulbright Specialist Program.................1 July – 30 September