6 minute read

29 Julie Curtiss, Jazoo Yang

The Millennial Art Star Julie Curtiss’s Paintings Now Sell for Half a Million Dollars. It’s Kind of Freaking Her Out

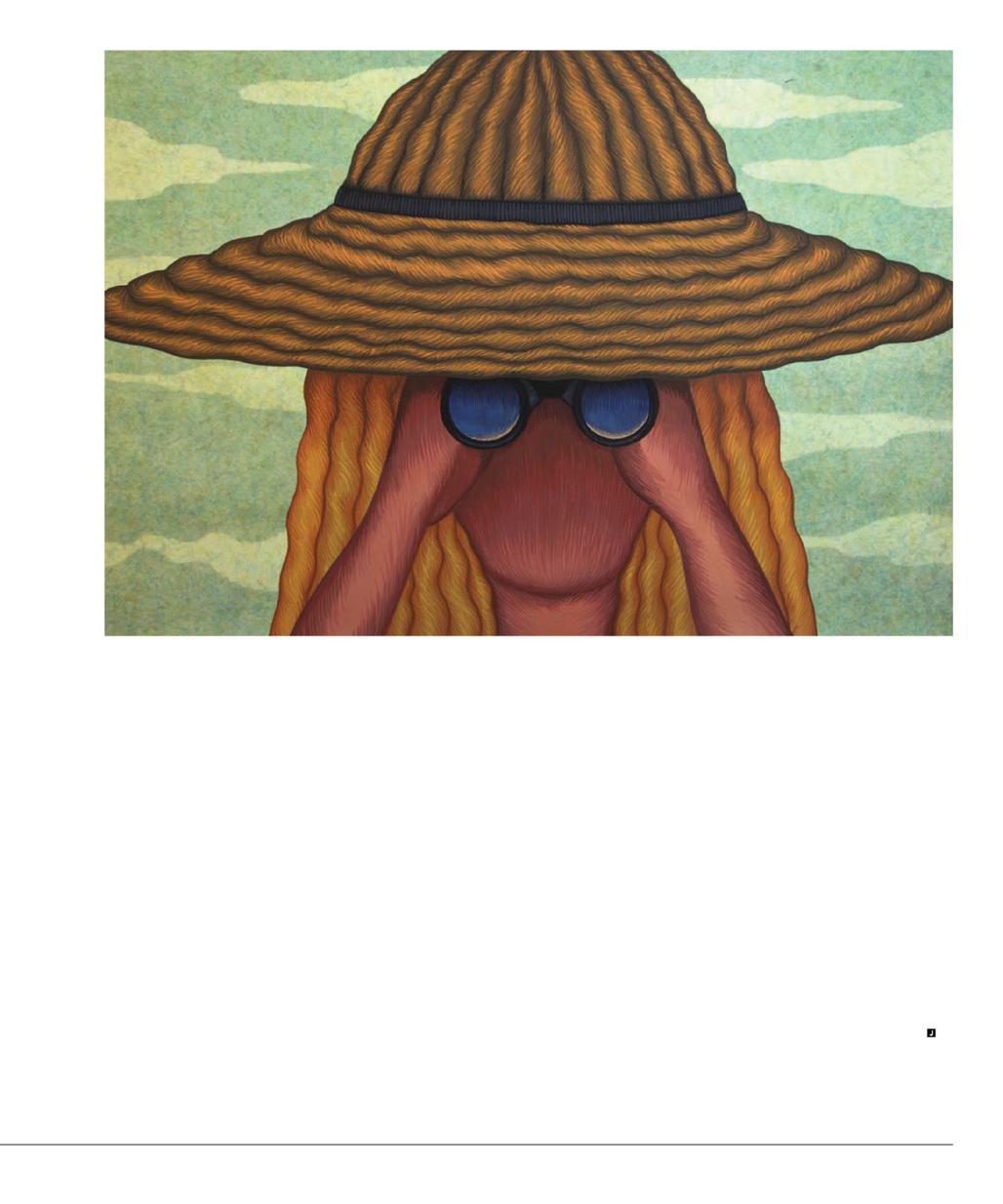

On a Wednesday in the middle of May, the artist Julie Curtiss was at her studio in a converted Bushwick warehouse live-streaming the afternoon contemporary art sale at Phillips. Slated at lot 16 was a one-by-onefoot painting that Curtiss had made about three years earlier, estimated to sell for between $6,000 and $8,000. Princess (2016) is typical of her output: a painting of a woman’s head, seen from behind, her hairdo done up in side cinnamon buns. It was the first Curtiss picture to be auctioned anywhere, and the young artist watched the stream with some trepidation. When the bidding on her worked opened, paddle-wielders in the room and buyers on their phones quickly pushed the price past the high estimate, higher and higher, until it hammered at an astounding $85,000 ($106,250 with fees)—a 7,770 percent increase over the $1,350 paid by the collector who first bought it from an artist-run project space just two years ago.

Advertisement

In the span of minutes, Julie Curtiss became an art star, and she was giddy and also a bit horrified.

“I was thinking, it’s scary, and I’m not making a buck on this,” she told me in her studio earlier this month.

She was sitting on a stool, dressed in painting clothes and a coat. She chose her words carefully but they came out fast, tinted by a French accent chipped barely away by a decade in New York. A playlist was streaming on

Such immediate validation from the art market means that an artist is doing something right. Most never get close. There are people who want a Julie Curtiss, even if they just want to sell one to someone else who wants a Julie Curtiss. Some say she’s the prototypical young artist blowing up in a vicious art market. Curtiss’s naysayers—and she has a few—predict that the auction result was a flash in the pan, and that the feverish speculation will die down before the next cycle. Julie Curtiss was born in France in 1982, and is of French and Vietnamese descent. After growing up in Paris, she studied at the École nationale supérieure des BeauxArts, and then at the Hochschule für Bildende Künste in Dresden. She then made her way to the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, where she first encountered Imagists such as Jim Nutt, Ray Yoshida, and Roger Brown. But it’s Christina Ramberg, more than anyone else, whose aesthetic most resembles Curtiss’s—a comparison she acknowledges, though she said she developed her own style before ever coming into contact with the elder artist’s work.

“I was doing works that were so similar to Ray Yoshida and Christina Ramberg, and when I saw her work I was so shocked,” she said. “For artists, it’s hard because sometimes you do something on your own and you see someone who’s doing it 10 times better than you, and their work is always there. So I was like, what’s the fucking point?”

While studying in Chicago, Curtiss met her husband, the artist Clinton King. After graduating, they went to Japan for a year, where she came under the influence of comics and Manga, which led her to a more graphic style. The couple later moved to New York, and for a fraught year, Curtiss worked as a studio hand for Jeff Koons. “It wasn’t exactly conducive for an art career,” she said. She quit after she turned 30.

When you think about the notion of time, the present and the past, about artists, streets and walls, one way or another you will find yourself staring at the image of the Berlin Wall – a wall which was always a symbol of the ut- terly physical line between the present and the past; between the world with a future and the one which was destined to be inevitably lost.

In 1989, when the wall fell, on the oth- er side of the continent the family of the 10-year-old Jazoo Yang moved to the new small apartment in the middle of a large-scale redevelopment area. The urban landscape of South Korea was rapidly changing at that time, so there was always some construction work near Jazoo’s home. It’s not hard to imagine how she used to spend the time with her younger brother by ex- ploring the ruins on the site or simply watching the workers shifting between destruction and construction. Ironically, today Jazoo Yang is based in Berlin, and the big part of her artistic

Jazoo Yang

Through her artistic practice, Jazoo Yang tries to understand the nature of time and to explore the special kind of nostalgia – a longing for the unfamil- iar past. Jazoo is wander- ing through the streets of different cities with a great care for details and the objects around her. This is the way she collects the fragments of urban environment in order to transform the broken pieces into framed works. Whether it is a layer of the peeled pale paint, the piece of wood or a tile, these “specimens” are meant to maintain the certain time and place in the hands of an artist. When German

artist Kurt Schwitters was collecting the fragments of the ruined country dur- ing the interwar period, those pieces were scream- ing in his collages. But times have changed and the modern age is mere- ly one step away from being overwhelmingly noisy; there is no use from screaming here anymore. Jazoo’s pieces are not screaming; instead, they are gently whispering a promise never to forget.

Street art

In 2015, back in the days when Jazoo Yang was still living in South Korea, she started the Dots series. She simply covered the house which was set to be demolished with her finger- prints. Meticulously day by day, fingerprint by fingerprint, she marked the entire house with INJU (traditional Korean ink-soaked pad used for taking thumbprints on the docu- ments, since it has a legal effect similar to a personal signa- ture). It was Jazoo’s poetical act against the redevelopment crisis in the port town of Motogol. It was her very own way to overcome the personal trauma and the common sorrow of local inhabitants who were forced to witness the wreckage which they once called home.

And do you know who actually taught Jazoo Yang how to use INJU in a proper way? It was the manager working at this particular redevelopment area. From the very beginning, the man wanted to get rid of the uninvited artist on the site, but soon he somehow became friendly with her. Maybe it was caused by support of local inhabitants or perhaps by her charm which naturally comes with such a sensitive persona. Whatever the reason might be, the manager opened to her through many stories and he was the one who made a valua- ble advice – to mix the ink with water in order to have a clear fingerprint. He surely knew the case, since all the documents regarding redevelopment were validated by INJU thumb- prints. Made by the hands of residents… The artistic practice of Jazoo Yang varies between the studio work, street intervention and live painting. Therefore, she can simultaneously fit into the “uncontaminated” gallery show or the “street art” event. Lately, she partic- ipated in the 8th edition of Bien Urban, a French festival which is currently consid- ered as one of the most gen- uine and forward-thinking events in the field of urban art. This year, the festival was co-curated by American art- ist Brad Downey, thus Jazoo Yang had a chance to discov- er the streets of Besançon in a company of Santiago Sier- ra, Helmut Smits, Vladimir Turner and other artists who are known for their uncon- ventional perception of the street.