14 minute read

Artists of the Holocaust

The artists of the Holocaust era had a story to tell. Though much has been lost, the remaining art is a testimony to the lives they lived and the horrors they encountered. Liz Elsby is determined to share their stories and preserve their legacies. Elsby is an artist, educator and tour guide at Yad Vashem the World Holocaust Remembrance Center Holocaust Museum in Jerusalem, Israel. Elsby has been working at the International School for Holocaust Studies at Yad Vashem (ISHS), since 2006. ISHS provides Holocaust education to diverse audiences from Israel and across the world, including training for educators to teach the Holocaust. It is the only school of its kind, utilizing an interdisciplinary approach of educating through art, music, literature, theology and drama.

“I was always really fascinated by the Holocaust,” shares Elsby. “My dad’s whole family came from Grodno, Poland and from Riga. Almost all of them were murdered either in Treblinka or Auschwitz…so that was always kind of there in the background. It’s not something my dad felt comfortable talking about, but I was always fascinated by the subject.”

Advertisement

Born in New York, Elsby and her family moved to Texas when she was 12. Illustrating and painting since she was a little girl, she was a National Scholar in the Arts and attended an art high school in Houston. She received a full scholarship and attended university for a year and a half in Philadelphia. Discontented in with Jewish life in Philadelphia and Houston in early 1980’s, Elsby decided to join a Kibbutz Ulpan in Israel for six months. She made Aliyah to Israel in April 1984.

“That ‘six months’ turned into 36 years -- I’ve been here ever since. I was a little Jewish kid from Long Island when we moved to Houston and I was the only Jewish kid in the class. I felt very disconnected. My family was very Zionistic and I always kind of dreamed of going to Israel.”

Elsby served as a graphic artist in the Israel Defense Forces from 1985 to 1987. She went on to The Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design, graduating in 1991 with a BFA degree in illustration and graphic design. She worked as freelance illustrator and artist for many years, and served as a courtroom artist at the 1996 trial of Yigal Amir, who assassinated Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin.

In 2006 Elsby’s career took a new path when a friend told her about an opening at Yad Vashem as a content writer in the web department. Elsby was grateful to be accepted with no background in history. Once Yad Vashem learned of her graphic design background, she was recruited for that role as well. By 2007 Elsby took the course to become a museum tour guide. “I absolutely fell in love with teaching and educating and teaching people about the Holocaust.”

At Yad Vashem, Elsby’s love of art

As I stand on the border between life and death, certain that I will not remain alive, I wish to take leave from my friends and my works…My works I bequeath to the Jewish museum to be built after the war. Farewell, my friends. Farewell, the Jewish people. Never again allow such a catastrophe.

gave birth to a unique form of holocaust education. Art is not only as a portal to the past but as a memorial for those who would have otherwise been completely erased…?

“As fascinated as I am with the Holocaust, I began to really really hone in on what it meant to create art during this terrible time. That as an artist you could still create art under such terrible circumstances and that the art wouldn’t only be what people think it would be – kitschy images of barbed wire and yellow stars – that people could go beyond that a find a place inside themselves. I became fascinated by Holocaust art and got into it more and more. I was very grateful that I had a platform at Yad Vashem.”

“Holocaust” art refers to the art created during the period of 1933- 1948, from the year the Nazis came to power until three years after the war ended in 1945. Yad Vashem houses the world’s largest and most comprehensive Holocaust-era related collections, with a few smaller collections housed at other museums. Between ten and eleven thousand pieces of art survived, and Elsby explains that it is a mere fraction of what was created over those years, with most being lost or destroyed. Some artwork was entrusted to friends or hidden, but most was never retrieved, and many pieces were confiscated and destroyed by the Nazis as Jewish art. Much of the surviving Holocaust art comes from Theresienstadt.

Though her family originated from Poland, Elsby became very focused on Czech Jewry and Theresienstadt. Before her parents passed away last summer, Elsby would meet them yearly in Prague to visit the city and study Jewish life and the art of Terezin.

Theresienstadt/Terezin was a camp 30 miles north of Prague in the Czech Republic. Considered the “better“ ghetto, Theresienstadt was a hybrid concentration camp, transit camp and ghetto established by the Nazis during World War II in the fortress town Terezín, located in a

Entrance to Terezin Concentration Camp

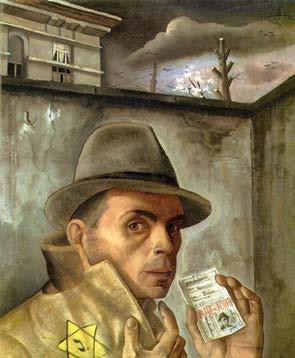

Felix Nussbaum, The Refugee, 1939. Yad Vashem

Liz Elsby talking to the Finnish Parliament on International Holocaust Remembrance Day

German-occupied region of Czechoslovakia. It was named after Empress Maria Theresa who expelled the Jews from Prague during her rule in the 18th century.

Terezin’s prisoners included scholars, philosophers, scientists, artists and musicians, some of whom had achieved international renown, and many of these contributed to the camp’s cultural life. Many Nazi propaganda films were made at Terezin. Jewish artists were forced to create artwork for the Nazis, and many Jewish artists fought back by creating their own artwork. Some of the art served to document reality, while some served as a means to find temporary refuge.

“For me, a piece of artwork that someone left behind who was murdered is almost like their tombstone,” says Elsby. “There’s nothing left of those people. Most of them didn’t leave anything written about themselves and some we don’t even know their name, but they left this beautiful piece of art or some kind of expression behind and that’s a monument to the fact that they lived. The more I talk about them, the more I give them symbolic life again. That’s why I do it.”

By 2013 Elsby decided to focus on the educational aspects of art and keep her own art more recreational and personal. Personally Elsby loves illustration, children’s illustration in particular, and is currently working on illustrating a book about a little girl in pre-war Krakow. She aims to portray Jewish life and show that the Jews had their own lives and identities just like any of us, not only through the lens of history and the Holocaust.

Elsby lives with her family in Kiryat Yovel, Jerusalem, not far from Yad Vashem. Elsby’s passion for the arts runs in the family. “My dad was very artistic even though he never really pursued it. Dad was in love with opera and classical music. Both of my daughters are artists.”

Her days are typically immersed in Holocaust education, filled with guiding in museum, giving seminars usually about art and Theresienstadt. Elsby leads tours to Poland and Auschwitz and attempts to show visitors Jewish life before the war - she has gone 23 times to date. Several times a year she is sent by Yad Vashem to visit cities across the US to teach about antisemitism and Holocaust education. She also works with “Echoes and Reflections”, an educational organization which would send her to the States to teach teachers, both Jewish and non-Jewish, about the Holocaust and how to teach it accurately and correctly. Elsby had recently taken on some of the social media responsibilities for the International School as well. These busy days are much quieter now with Yad Vashem temporarily closed to visitors and many of her other teaching and touring duties cancelled due to the coronavirus pandemic.

She relishes every opportunity to teach, even virtually. Elsby, who spent part of her childhood in the Five

There’s nothing left of those people. Most of them didn’t leave anything written about themselves and some we don’t even know their name, but they left this beautiful piece of art or some kind of expression behind and that’s a monument to the fact that they lived. The more I talk about them, the more I give them symbolic life again.

Towns of Long Island, New York, recently presented an online Zoom lecture to The Marion and Aaron Gural JCC of Cedarhurst. In introducing the lesson on “Art in The Shoah”, Elsby explains Holocaust artists were regular artists caught in the wheels of history, and likens the art of the Holocaust period to “the gravestone for those who don’t have a grave.”

One such artist was Felix Nussbaum. Nussbaum was an up and coming German Jewish artist who studied in Rome until the Nazis came to power. Nussbaum went into hiding. “The Refugee” is Nussbaum’s 1939 painting depicting imagery of a wandering Jew in despair. Another evocative work several years later is Nussbaum’s “Self Portrait with Jewish Identity Card” (1943). This work is a dark and haunting self-portrait surrounded by smoke and shadows. Far off in the distance Nussbaum places a small blooming tree, possibly representing a glimmer of hope that he still may have been holding on to. Nussbaum was found and sent to Auschwitz and murdered in 1944.

Another notable artist was Ilka Gedo (May 26, 1921 – June 19, 1985). Gedo was a talented Hungarian painter and graphic artist. One early work was a self-portrait, faded and with darkness over her eyes, though she was only in her early twenties at the time. Elsby shares the story that Gedo’s name was called for deportation from a group of Jews staying together in a home in the Budapest ghetto, when an older man steps up and takes her place. This selfless unknown rabbi was a remarkable example of the Jews who saved other Jews. Gedo’s later work was a portrait with no head and with twisted hands; perhaps an expression of survivor’s guilt. Gedo doesn’t paint again for 20 years. When she resumes in the 1960’s, her art is all in the abstract style.

Elsby explains how art served as a testimony, and was especially valuable at times when several artists portrayed the same scene. Some of the art from Terezin bears witness to the horrors of the life of the ghetto, for example five artists who depicted the arrival of 1091 kids from Bialystok that were sent to Auschwitz a month later. Another illustrated incident was that of a public hanging in 1942. Leo Haas was one artist who depicted the punishment of young men arrested for writing letters home to their parents in his drawing “The Hanging of a Ghetto Inmate”.

In places like Terezin, the artists

that were forced to work for the Nazis would steal supplies and make secret art at the risk of their lives. Elsby tells of a July 1944 incident. “Four of the artists were caught for creating what the Nazis called “horror propaganda”, in other words, artwork showing the horrors of the ghetto. The group, including an art dealer and an architect, were arrested and sent to prison in a concentration camp called “The Little Fortress”. Only one of the artists survived the war.”

The horrific conditions in concentration camps like Auschwitz-Birkenau made it virtually impossible to create art in the other camps. There were some artists, however, who had been selected by their talent to work for the Nazis. Halina Olomucki was taken and forced to work, stenciling wallpaper by hand and making signs. Olomucki would steal paper and pencil and draw the women in her barracks at night. Knowing most

of them wouldn’t survive, the women would beg her to draw them so that there would be some memory of them left behind. Olomucki was one of the very few Jewish artists who were able to create art in the extermination camps.

Much of the Holocaust art that was recovered was hidden in the ghettos. The Warsaw Ghetto in particular had a treasure trove hidden under the ghetto as depicted in Who Will Write Our History?, a 2018 film Felix Nussbaum, Self-Portrait with Jewish Identity Card, 1943. Yad Vashem

executive produced by Nancy Spielberg and based on a book by Samuel Kassow. The book chronicles the valiant initiative of Dr. Emanuel Ringelblum and the secret archive he created and curated in the Warsaw Ghetto under the codename “Oneg Shabbat”, or Oyneg Shabes in Yiddish.

More than thirty-thousand pieces of documentation was hidden by this group in their quest to leave evidence of their lives and experiences – artwork, interviews, essays and letters – all hidden under the city of Warsaw. Though almost all of the participants were murdered, many of the documents and art survived.

“This group of people knew that something terrible was going to happen in the ghetto. They wanted their voice to be the voice that would tell the story of the Jews, and not the Ilka Gedő, Self-Portrait, 1947. Yad Vashem

voice of the Nazis. The Nazis showed Jews as rats in the sewers; they wanted the actual voice of the people so they went on this initiative to collect documentation. It’s an amazing story.”

Elsby remarks how the art had to come out of the artist even under unsafe and very limiting circumstances. “It’s an amazing testament to the human spirit that you can’t squash that expression – they still created. What I also think is amazing is that one of the things the Nazis said is that Jews bring no beauty into the world, they only bring ugliness and they don’t create -- and every single piece of artwork is like a slap in the face of that Nazi ideology. Every piece of artwork brings some kind of beauty, brings something new into the world – that’s if they’re making art or making music or writing poetry or teaching kids-- that’s all ways of bringing something positive into the world against everything the Nazis said. It’s a real act of resistance.”

Most communities didn’t have the ability to have an uprising like in Warsaw and there were about 100 uprisings in Nazi occupied Poland and most were doomed for failure from the start. Elsby views the art as a means of fighting back – both as a form of survival and rebellion.

Elsby is concerned for the education of the younger generations who won’t be growing up with Holocaust survivors. “You have to tell the story through the first person narrative; it has to be the human story and art is such a human expression. Writers write, diarists write diaries and artists tell their stories through their artwork -- that’s their witness and that’s how they become an individual. So artwork really shows us that these were individual human beings and I think that’s the most important way to remember the Holocaust, not only through numbers and statistics …who were they and what were the individual stories? It makes it much more relevant for younger people.”

Elsby feels a loss of not being able to educate now, with Yad Vashem closed to visitors and most of her regular educational programing on hiatus. Two of her trips, a March of the Living tour and United Synagogue Youth trip kids to Prague, Berlin and Poland, were unfortunately cancelled for 2020.

“I think it’s really important to talk about because I think now, with all these things happening, this whole story is kind of getting lost -- and we’re not going to have survivors soon. Everyone is so wrapped up with everything else happening in the world that it’s really the time to stand up now and remember these people and make sure their stories are told. We owe it to them; they won’t be here to tell their own stories soon.”

“The ignorance is so astonishing with all of the terrible things coming out now – we have to be vigilant,” cautions Elsby. “We have to teach young people they’re our hope for the future, and I think to teach them to be able to relate to this is through the stories of individuals.”

One can look to the Diary of Anne Frank to see how much impact came through telling of the human story, and how her story helped masses of people understand history on a more personal level. In a modern age where images hold so much value, art can certainly play a tremendous role in bringing the history and the horrors to light.

“Every time they take the Holocaust and make it into a story of a person or a community or a family then people can understand it and relate to it and that’s what art does also. Art makes it much more of human story. “

Art and additional resources can be found at www.yadvashem.org/ education