14 minute read

JEWISH THOUGHT

Torah Thought Man of the World

By Rabbi Zvi Teichman

Advertisement

There are certain flaws that are chronic and cannot be cured. The male members of the nation of Ammon and Moav, the products of the incestuous act of desperation when the daughters of Lot thinking the world was coming to an end mated with their father Lot, are forever condemned, despite having converted to Judaism, from entering the congregation of G-d, prohibited from ever marrying a standard Jewish women.

The reason for their being so ostracized stems from their ancestors lack of gratitude to the descendants of Avraham Avinu. Despite the fact that Avraham saved their patriarch Lot and their mothers — the daughters of Lot, first from captivity in the hands of the four kings in the battle of the four and five kings and once again years later from the upheaval of Sodom, owing their entire existence to his intervention and merit on their behalf, they betrayed this loyal ‘brother’ when Avraham’s descendants left Egypt, ignoring this beaten relative, never offering them bread and water, nor any brotherly concern.

It would seem then, that this trait of ingratitude is anathema to the essence of what comprises a Jew. Could it be that simply not going forward in greeting their relative and offering food and drink disqualifies all its male descendants for all of posterity from ever attaining a full status as a member in the congregation of G-d?

The Torah though adds one more reason why the Moabites are to be shunned. The Moabites fearing being overtaken by their ‘cousins’, hired Bilaam to curse and eradicate the Jewish nation. rather minor offense of their not having reached out to them in kindness? Why would the Torah even mention their lack of brotherhood as a sign of their ungratefulness when they displayed a much harsher display of this character flaw in wanting to affect them with terrible curses?

There is a famous Yiddish expression that goes: איהם איך האב וואס אזוי פיל גוטס געטאן אז ער האט מיך אזוי ?פיינט —What great favor have I done to him that he hates me so much?

It is one thing to lack appreciation for a kindness done, but when one’s ego doesn’t let him rest in the knowledge that he is indebted to someone else, prodding him not merely to defensively ignore the favor that came his way but to develop a hatred for the one that exposes ‘my’ vulnerability, that is when ingratitude becomes a fatal flaw.

One who is totally absorbed with himself and his wants, needing constant validation, will be incapable not only of gratitude but in valuing another person at all.

Lot is saved from the upheaval of Sodom. The angel directs him to seek refuge on the mountain. Lot begs to let him stay in Tzoar instead, which is closer by. The Midrash explains that Lot feared being in the proximity of Avraham which would make him pale in significance and preferred being among others of lesser stature so that he may appear righteous. The angel accedes to his request.

Did the angel err in directing him to a location that might endanger Lot due to his diminished standing? Certainly not. His concession was an affirmation of Lot’s inability to see beyond himself, which didn’t permit him to be portrayed as saved solely in the merit of Avraham. How indignant! Even when his very life is at stake Lot’s narcissistic attitude pleads desperately for a meager portion of merit, enabling him to ‘survive’ on his own credit, denying the merit of his loving, selfless and devoted Uncle/brother-inlaw, Avraham. How pathetic.

One who is blind to anyone but oneself is undeserving of kindness. In fact, regarding this nation specifically the Torah forewarns — You shall not seek their peace or welfare, all your days, forever. The Targum Yonoson on this verse asserts that this prohibition extends not only to the gentile members of these nations but even to a Ammonite or Moabite who converted and is now fully Jewish is afflicted with this ‘genetic’ flaw and one must refrain from acting kindly toward him so as not to violate this prohibition to ‘not seek his welfare’.

Is it possible to fathom that the ‘Torah of Kindness’ could expect someone to survive amongst our people without ever being the recipient of kind-heartedness?

Rabbi Eliezer of Metz, the 12th century French Tosafist, asserts that kindness may not be initiated to the members of this corrupt nation but one may repay acts of benevolence they have extended our way, with kindness in turn. He brings proof from an episode where King David acted kindly towards Chanun, the son of the Ammonite king Nachash, in gratitude to his father Nachash who gave refuge to a member of King David’s family.

Perhaps the antidote to this inherent defect is to force a member of these imperfect nations to become so devoted and selfless towards their fellow Jews so that others in turn will be permitted to respond to them in kind. to my beloved and my beloved is to me, is the word אני’ ,I’.

We must first discover ourselves. Who am ‘I’, indeed?

The great Gaon, Rabbi Shimon Shkop writes that our job is to expand the who ‘I’ am to include our family, friends, community and the world, coming to the understanding that we were placed in this world to define who we are by the yardstick of how far reaching our actions are in impacting the world around us.

“If I am not for myself, who is?”— Each one of us must take ownership of that responsibility, to define the ‘I’ — for no one else can.

“But if I am for myself, who am I?” — If we only seek to placate our personal needs and stoke our ego, existing solely within the space from the top of our heads to the sole of our feet, then we are indeed nothing, and have .identity true no )הקדמה שערי יושר(

One of the tactics of Elul in assuring a successful Day Judgment, the great scholar and ethicist, Rabbi Yisroel Salanter suggests, is to become a person, לו צריכים שרבים , whom the masses need him.

In the words of the famed Mashgiach, Rabbi Shlomo Wolbe: The masses need him - one who is not an egoist, one who does not live for himself! His attributes: kindness, patience, love for humanity. Pure in fear, who toils in Torah. One doesn’t have to be an Askan, a community official but just to share in the burden of others even if he never leaves the walls of his four cubits. The true image of a Jew is one who is valued and needed by others.

May we each become ‘men of the world’ in defining the special role we each play in promoting the honor of Heaven. In that merit we are guaranteed a favorable judgment on Rosh Hashana.

100 Years

1,000S

DAILY BY ARIEL VALE

Life

for a Shabbos-observing Jew in the early 20 th century was not easy in America. Friday after Friday, men would be fired from their jobs. It took a courageous group of men to make the move upstate where it would be easier to find an occupation that would not interfere with their values. In the summer of 1920, the Woodbourne Shul was founded.

The shul was not just a place where people came to daven. It was an active center for an active Jewish community. What better place to hold a slaugh

terhouse for kosher meat than the back room of the shul?

The years passed with much victory and advancement for the Shabbos Jew. The city boasted large communities with many job opportunities. Slowly, the children of so many ended up moving back, seeking their fortune there. Across America, hundreds of shuls were forced to close their doors, boarding them up or selling them to others. The glorious Woodbourne Shul did not escape that fate. At the turn of the millennia, eighty years after opening, saturated with thousands of teffilos and

dozens of bar mitzvah celebrations, the shul had no choice but to close its beautiful doors forever. The board members were adamant that a holy edifice as such should not be sold or defiled. For ten long years, the shul sat boarded up in silence, waiting.

There was an elderly woman, well into her eighties, devotedly caring for the kever of the Menuchas Asher, Rav Asher Anshil, of blessed memory. When asked what prompted this, she replied: “When I was in my forties, the doctors had already given up on my life. I prostrated myself on the kever and tear

fully davened. Ever since then, I devotedly maintain the upkeep of this special tzaddik’s resting place.”

The legacy of this miracle worker continued when his son replanted his father’s community in Crown Heights. The kehilla was of great acclaim and merited an annual visit from the Satmar Rav, Rav Yoel. It was in this setting that the next generation, Rav Mordechai Zev Jungreis, Nikolsburger Rebbe, was born.

Every alumnus of Yeshivas Rabbeinu Chaim Berlin will remember his year with Rabbi Jungreis with ease. Giving and loving are the two traits that are oft repeated when describing that unusual time. Just recently, a talmid brought his grandson to the Rebbe for an upsherin, a sure example of the type of bond that is formed between rebbi and talmid.

But there’s more. A young married man with a few children of his own revealed something fascinating. When he was a young boy in Yeshivas Chaim Berlin, he was known as a troublemaker. Rebbi upon rebbi would send him out of class to wander the halls. However, every boy knew “that if you get kicked out, you go to Rabbi Jungreis’ class.” The man attributed his success in staying frum and bringing up a family to that safe haven where everyone was unequivocally loved and accepted for who he is. Where others struggled in the area of chinuch, the Rebbe thrived and achieved. It is with this background that we begin to understand the miracle that occurred. The Rebbe heard the silent plea of that forlorn building standing erect on Main Street and decided that the time had come to reinstate it. The building that had served its members faithfully for eighty years and lay dormant for ten was about to fulfill a role not unlike its original one.

There were Jews, tens of thousands of them, making the trip up to the Catskills to vacation. Camps and bungalow colonies were bursting at the seams, and it seemed that there was a lot more freedom, and loneliness, for children at risk. They were there, roaming the streets; hollow, sad eyes, but who even noticed them? Did anyone even care?

The Rebbe cared. The Rebbe’s heart was open for them.

But here’s the secret.

The Rebbe loves them because he loves everyone. Be he a fellow Rebbe, Litvishe Rosh Yeshiva, at-risk teen, or anyone in between, you are a diamond in the eyes of this defending angel.

So he worked hard. He bargained, cajoled, and begged the skeptical board members to reopen.

“There is a need, it’s time, and we’re ready,” he claimed, but there was a lot of red tape, ill feelings, and disbelief to work through.

He got the call while sitting in Chaim Berlin

with his precious talmidim.

“Are you still interested?” they wanted to know.

“I’m driving right up!” he exclaimed as he jumped into his car for the long trip.

There were a lot of conditions and obstacles, but soon enough, they were in business. The Rebbe got to work ceremoniously placing a cardboard box in front of the shul proclaiming: “Minyan Mincha.” Passing cars rolled down their windows, unabashedly sharing their opinion: “vus machstu meshuga?” [Why are you making yourself crazy?] they wondered. “Nothing will come of it.”

But the Rebbe pulled through, and the shul would open after one more necessary step.

The Rebbe ran to a printing store and ordered a large laminated sign. With this, the shul was fully operational. The sign read: “EVERYONE IS WELCOME.” Only with this can the doors open.

With the purchase of the building, the expenses started mounting. Electricity, water, refreshments, as the crowd quickly grew. To everyone’s disbelief, over 1,000 people entered through those doors in 2010, the first year they were reopened. By 2011, there were 10,000.

Today, there are thousands entering daily. Just count the used cups.

“Why is the Rebbe’s gartel wet?” people wanted to know. Come on over at 5:30 in the morning, you’ll see the Rebbe, rag in hand, wiping down each outside table in the aftermath of a downpour. There’s a full day of learning and davening ahead.

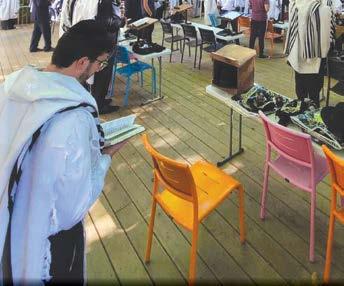

Shacharis starts at 6:05 a.m. When’s the next minyan? “As soon as there’s a minyan!” says the Rebbe. Come in at any given time, and you are likely to see six minyanim in full swing.

See only five? That means you’re a tzenter!

Don’t be fooled if you’re told that Nikolsburg closes at two in the morning. That’s just the inside. Outside, the minyanim are in full swing. The three hours of closure are very important for a Rebbe who never leaves his post during opening hours. He makes sure to use some of the time for sleeping. Don’t see the Rebbe? He must have gone to the bakery to buy more cake. Maybe he’s running low on lollipops for the children. There is no Nikolsburger gabbai. The Rebbe trusts nobody with this holy task.

“Why don’t you lie down for a few minutes?” urges his son.

“I rest in the car on the way to the bakery,” responds the Rebbe. “That’s when I get to sit down.”

Soon enough, the building got too crowded. It was time to extend.

“If there’s room in the heart, there’s room in the building,” he proclaimed after being offered money for renovations. Last year, the Rebbe acquiesced to building a deck behind the shul. Nobody was quite sure what changed. Then the world turned upside down. Will there be a shul this year? What about the people who don’t want to daven inside? The new deck held all the answers. Those concerned about Corona can stay outside. Those with antibodies come right in. While the Rebbe himself is always makpid to wear a mask, the open-door policy will remain regardless. The sign on the door urges all entering to follow suit; nobody is turned away.

“We must listen to the government and make a Kiddush Hashem,” the Rebbe says.

There is one thing that is never tolerated in Nikolsburg. One thing so appalling that even the Rebbe cannot bear. Machlokes is unwelcome here. Just look around the shul. It’s self-explanatory; only harmony.

Take a look at the Rebbe’s shtender. There are lists of names. People come for tefillos and brachos from this humble man. After all, he is a Rebbe.

Recently, a boy was lost in the forest. Bochurim came down to speak to the Rebbe. “Go back to camp and tell everyone to calm down,” he said with a forcefulness those closest to him didn’t know he possessed. “Tell everyone that he will be found.”

Sounds typical of a Rebbe. Now let me tell you about atypical miracles.

Every amud has a chiyuv. Would these people have been able to get one every day in a typical shul? Many admit that they would’ve missed davening with a minyan if not for this shul. Forgot your tefilin? Maybe you just never had any? Help yourself to a pair from the gemach. Don’t be shy. Nobody’s looking at you. Looking to make up a few missed minyanim? Just walk around the shul and stock up on kaddish.

This is the legacy passed down in the Jungreis family. Miracle workers. The minyan is culled together from Kew Garden Hills to Satmar. Nobody stares at you. Nobody cares what you’re wearing. All are loved and accepted.

Miracles!

Do you have another way to describe a day in Nikolsburg?