ADVENTURE STARTS HERE

SURF | IRELAND GRAVEL BIKE | AUSTRIA SKI TOUR | SWITZERLAND CANOE | CANADA

CYROX 2L DOWN JKT

Light, warm, waterproof down jacket with TEXAPORE ECOSPHERE membrane.

HIGHLY WATERPROOF

Extremely waterproof to keep you dry in extreme weather conditions.

HIGHLY BREATHABLE

Sweat and moisture evaporate efficiently through the TEXAPORE ECOSPHERE membrane.

AN EXCEPTIONAL YEAR-ROUND DESTINATION FOR SPORTS AND ACTIVITIES

Ideally located in the heart of the French Alps and a paradise for mountain lovers, Savoie Mont Blanc (the Savoie and Haute-Savoie départements) with its unspoilt nature, gorgeous snow-covered slopes, astonishing history and delicious food, is an exceptional area for a huge array of sports and activities in all seasons. With 110 resorts (including Val d’Isère, Chamonix and those of the 3 Valleys and the Portes du Soleil), Savoie Mont Blanc is also the largest ski area in the world.

To come to SMB this winter, book your ski trip with Go Savoie Mont Blanc, a door-to-door, multi-mode travelbooking service that allows visitors to a destination to book and pay for all their travel from A to B, in the same online basket and with the same means of payment. The options given are displayed with the estimated CO2 emissions of each means of transport, making the travel experience not only more efficient (by giving the best travel time and cost) and simple, but also greener.

gosavoiemontblanc.com/en 01

TOP 3 UNUSUAL ACTIVITIES IN SAVOIE MONT BLANC

01 –GO BACK UP THE SLOPES!

In Arêches-Beaufort – the French ski-touring mecca, famous for its international competition the Pierra Menta (13–16 March 2023) –you can swap the chairlift for skis fitted with synthetic seal skins in introductory sessions run in partnership with Dynafit during the school holidays, including trail loops, guided outings, and safety and best practice advice.

areches-beaufort.com

02 –CHALLENGE YOURSELF BY CLIMBING AN ICE WATERFALL

Fancy climbing ephemeral ice structures and pushing your limits? Try ice climbing in the Vallée de Peisey (peisey-vallandry. com) or in Bessans (hautemaurienne-vanoise.com), winter canyoning in the Haut-Giffre (latitudecanyon.fr) or even dry tooling (a dry version of an ice waterfall, using crampons and an ice axe to climb the rock) in the Alpes du Léman (alpesduleman. com).

03 –SPEND THE NIGHT ON A GLACIER

This mind-blowing descent of the legendary Vallée Blanche beneath a full moon is a true fairytale experience for highly experienced skiers, who descend 20km and 2000m between ice ridges and crevasses, amidst the peaks and spires of the Mont Blanc massif.

Led by the high-mountain guides of the Compagnie des Guides de Chamonix, the descent ends with a warming dinner in the Refuge du Requin. The same Compagnie des Guides offers a night’s camping on the Glacier du Géant at the heart of the Vallée Blanche.

chamonix-guides.com

01 ©️ Simon Hurion 02 ©️ cd.cuvelier_bessans 03 ©️ OT Chamonix

02 04

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Features

14 TRAILS FOR WALES

A closer look at the challenges faced by mountain biking trail builders.

Tom Laws

18 EDGE OF SANITY

A six-week Southern Ocean sailing expedition in the footsteps of Ernest Shackleton.

Danya Schwertfeger

24 GRAVEL LIKE A LOCAL: EXPLORING THE AUSTRIAN ALPS BY BIKE

Getting to know the gravel cycling paradise of Salzburg.

Katherine Moore

30 WE ARE ALL PROTAGONISTS

An all-women team take on the infamous unsanctioned running race from LA to Las Vegas.

Ashley Stewart

36 TRANSLAGORAI

Hiking what could be the last remaining true wilderness of the Italian Alps.

Francesco Guerra

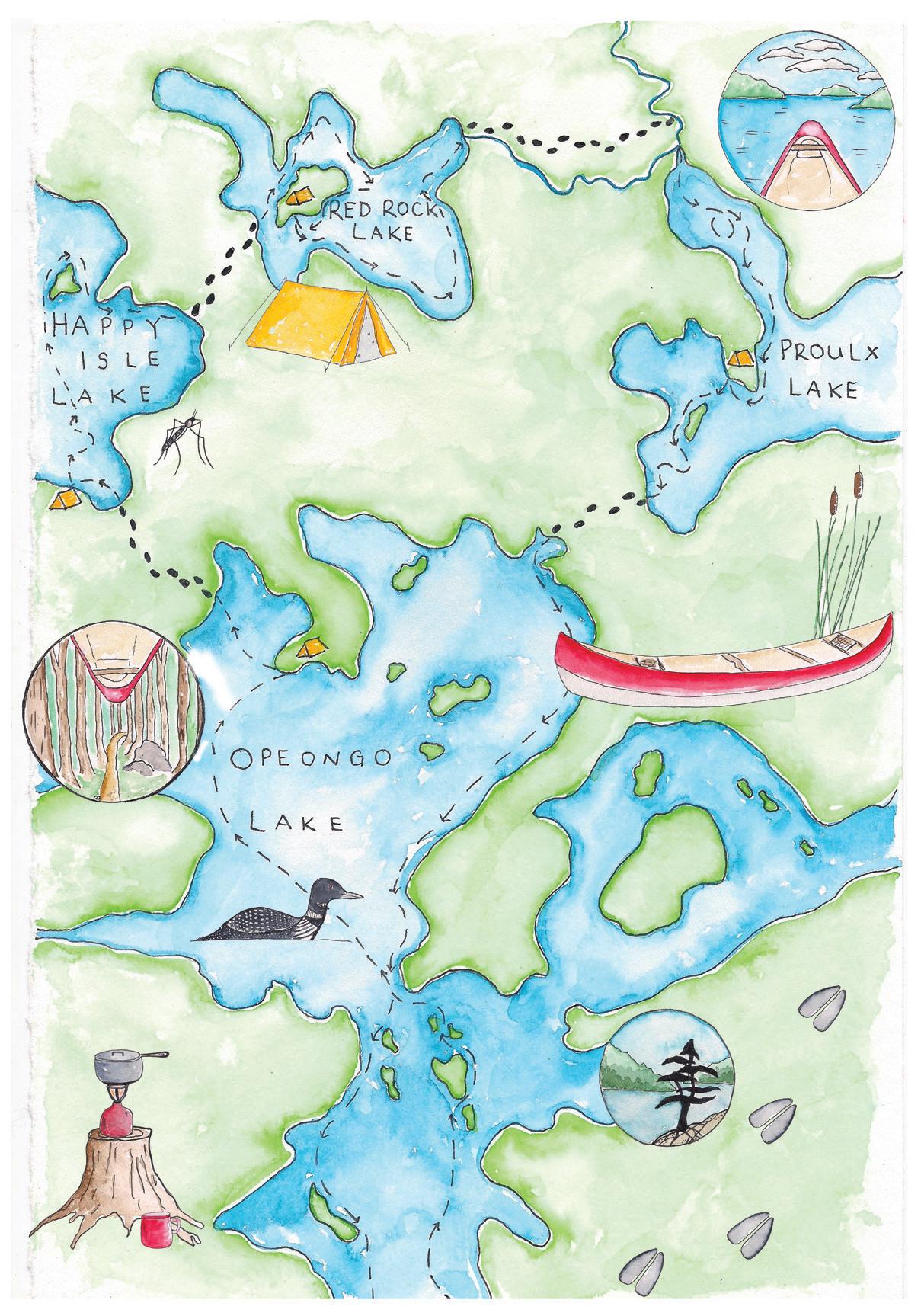

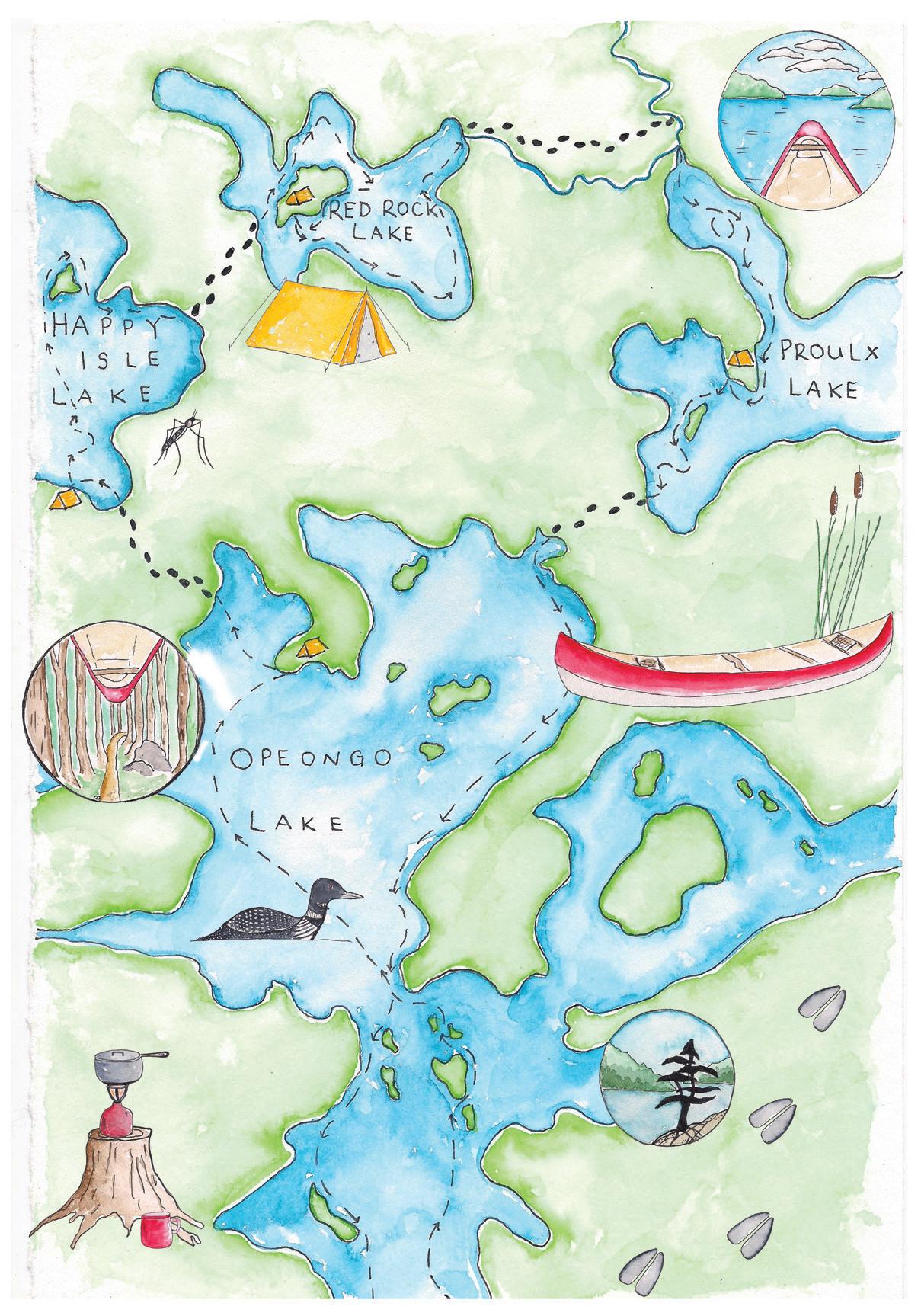

42 AT HOME ON THE WATER

Discovering a sense of place out on the lakes of southeastern Ontario.

Carmen Kuntz

52 FOOTSTEPS

An exploration of how heritage can shape our appetite for adventure.

Francesca Turauskis

54 URNER IN A ONER

Setting the fastest known time on Switzerland’s infamous skitouring route, across the Urner Alps.

Aaron Rolph

Contributors

Interviews

08 FINDING FLOW: GEORGE KING

The man known as The Shard Climber on sensation and freedom free-soloing the world’s tallest buildings.

Hannah Mitchell

46 THE CHANGING OF THE GUARD: MEGAN GAYDA

The photographer making waves in Ireland shooting the raw power of the Atlantic.

Luke Gartside

Regulars

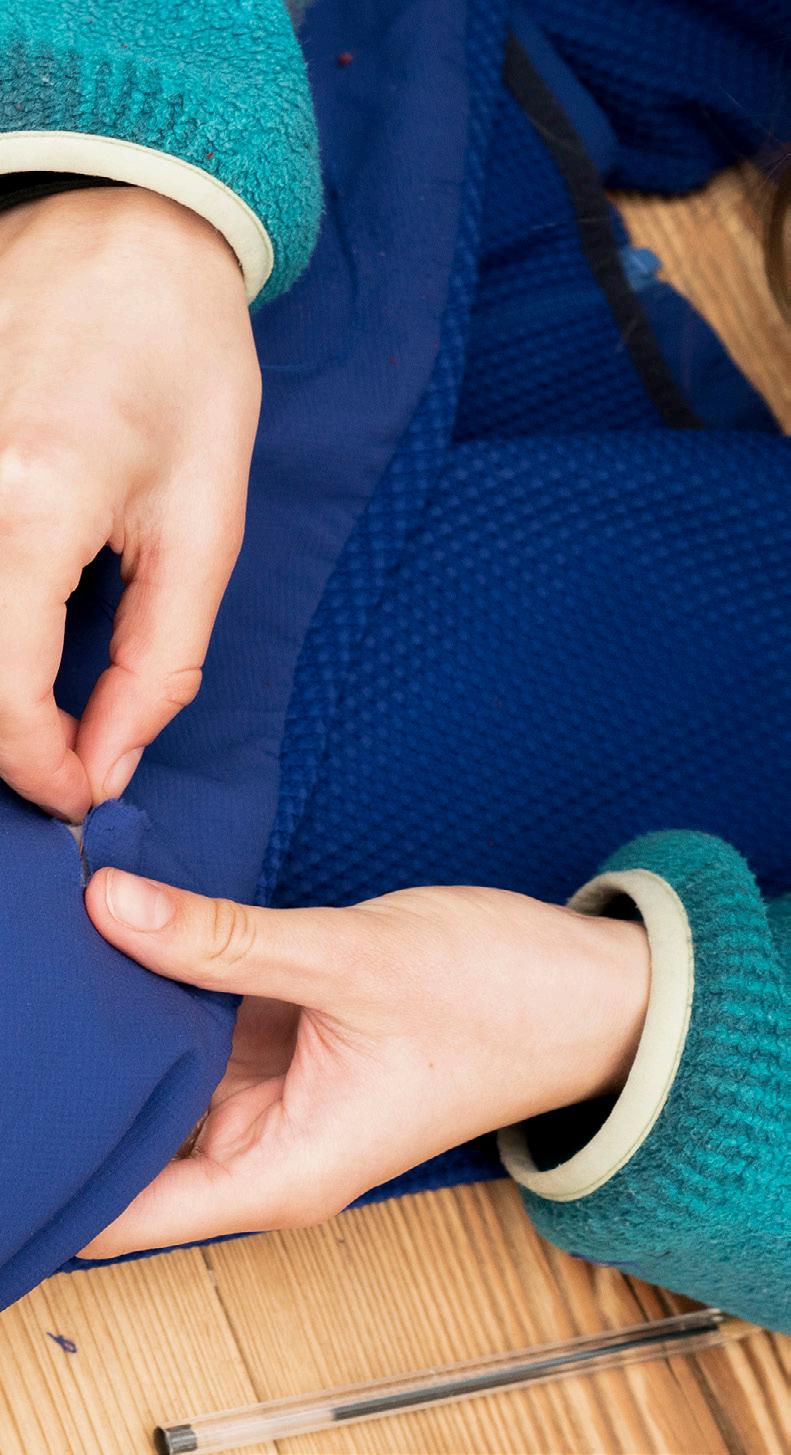

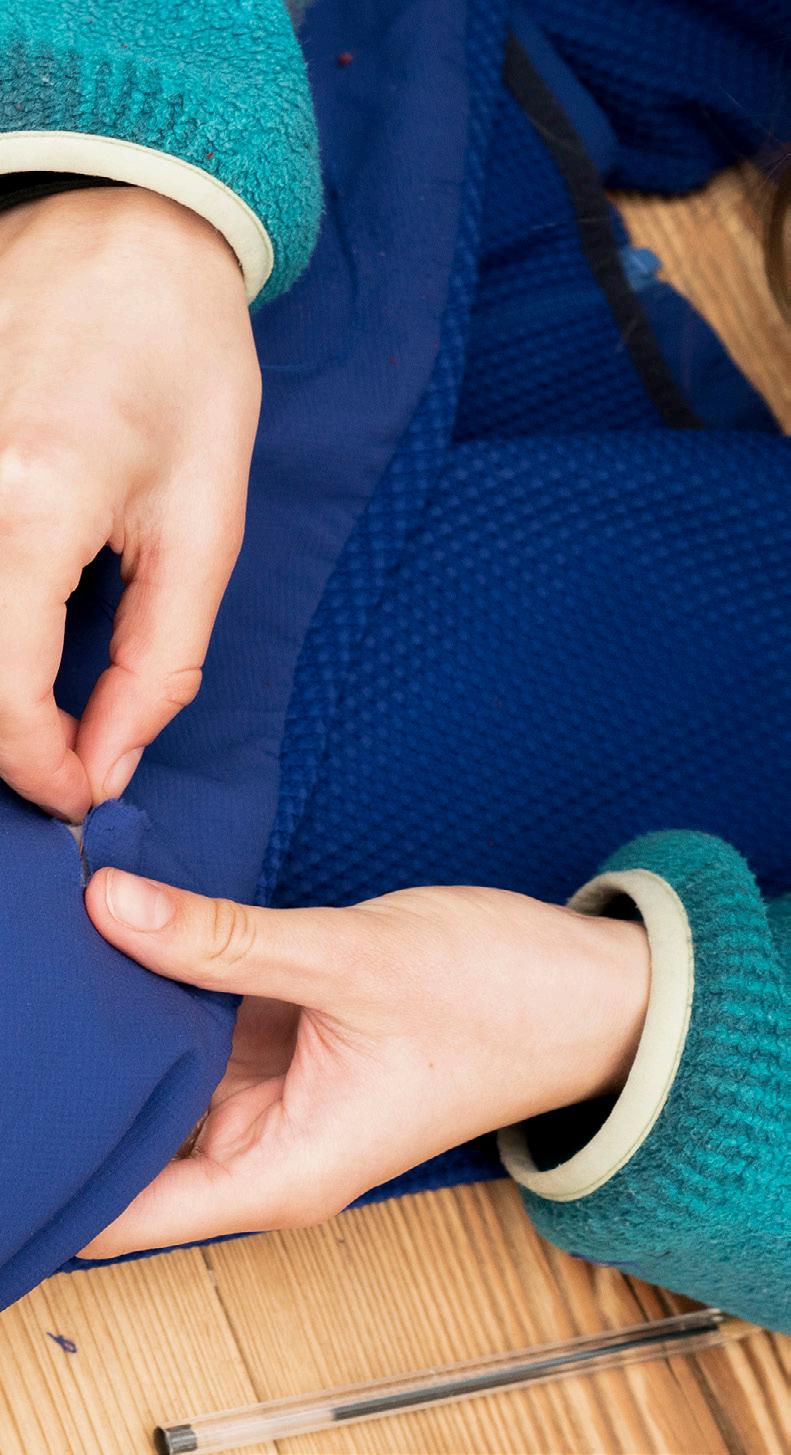

60 MAKERS & INNOVATORS: IF IT’S BROKE…

A deeper look at Patagonia’s campaign to reshape the lifecycle of their products

Chris Hunt

Hannah Bailey

Mark Chase

Tim Davis

Luke Gartside

Megan Gayda

Francesco Guerra

Editor Chris Hunt

Digital Writer and Content Editor Hannah Mitchell

Commercial Lead Ross Jones

Travel Lead Dom Eddon

Donald L. Hedden

George King

Carmen Kuntz

Tom Laws

Hannah Mitchell

Community Lead Bronte Dufour

Publishing Director Emily Graham

Brand Director Matthew Pink

Publisher Secret Compass

Katherine Moore

Ashley Stewart

David Robinson

Aaron Rolph

Danya Schwertfeger

Francesca Turauskis

Enquiries hello@base-mag.com

Submissions submissions@base-mag.com

Advertising ross@base-mag.com

Distribution emily@base-mag.com

4

COVER: Cillian Ryan in his element at his favourite wave, Rileys on the west coast of Ireland, in the depths of the winter. Shot taken from our interview with Megan Gayda on page 44 © Megan Gayda

©2023 POLARTEC, LLC. POLARTEC® IS A REGISTERED TRADEMARK OF MMI-IPCO, LLC.

TIKKACORE&ACTIKCORE

ThenewTIKKACORE&ACTIKCOREarecompact,powerfulandeasyto usewithlightingsuitedtoavarietyofoutdooractivities.Withasimplesingle buttonbothheadlampsalsohaveredlightingandcomewiththeCORE rechargeablebattery.petzl.com

6

EDITOR’S COMMENTS

Autumn 2023 – Legacies

In the same issue, Em Linford wrote of her personal connections to Dartmoor as she campaigned for the right to wild camp there. In recent weeks, because of the relentless work of her and others, we see the decision overturned.

And long-term followers of BASE will be plenty familiar with the work of Hamish Frost – one of the best mountain photographers in the game right now and a BASE Collective member. At the centre of a new short film, Hamish shares his experiences as a queer man in the outdoor space. It’s another strong step towards the dismantling of a notoriously uniformed scene. If you haven't already seen the film, I highly recommend you do. You can find it online via the BASE website.

It’s with this framing then that we plunge into issue 11. Through the voices and stories you'll find in the following pages, we explore this notion of legacy and what it means to the contemporary adventurer.

In Trails for Wales, secondary school teacher and fervent mountain biker Tom Laws dives into the world of wild trails, exploring the challenges faced, from conflict with land owners to extreme weather and the available solutions when it comes to their preservation. Earlier in 2023, Ashley Stewart joined an all-female team of runners to run from LA to Las Vegas. In her piece, We Are All Protagonists, Ashley pays tribute to those women and the bonds they formed crossing Death Valley.

In The Changing of The Guard, Luke Gartside catches up with surf photographer Megan Gayda, busy rewriting the rulebook when it comes to the status quo in surf photography; while Hannah Mitchell talks with George King from Seoul where he faces trial for attempting to free-solo and BASE jump from South Korea’s highest building.

Adventure is awash with BIG concepts. Mortality, purpose, friendship, identity, place – all notions many of us find ourselves navigating when we’re out there chasing whatever it is that makes us tick.

Eternally entwined with adventure and its documentation, is a sense of legacy. It could be breaking new ground, smashing records or flipping stereotypes. It could also be far more lowkey: leaving the trail in better shape than we found it, helping to educate and enable others or opening up the door for others to follow. And the best examples transcend adventure.

Of course we can’t mention legacy without a nod to a few of the modern-day pioneers sitting right within our own network. In issue 10, we caught up with Norwegian powerhouse Kristin Harilla after she was forced to abandon her 14 peaks campaign, just two summits short. We knew she’d be back, and in July she cut the record, previously held by Nims Purja, in half.

In Footsteps, Francesca Turauskis considers how her heritage informs her affinity for covering long distances on foot, while, following in the steps of Ernest Shackleton, in The Edge of Sanity, Danya Schwertfeger embarks on a sixweek expedition in the Southern Ocean, challenging his own relationship with sailing.

In Translagorai, Francesco Guerra strides out to explore what could be the last remaining truly wild space in the Italian Alps and in At Home on the Water, Collective member and regular BASE contributor, Carmen Kuntz explores why it is that with a canoe and a tent, she feels so content.

And of course it’s not just the individuals that have access to shaping this sense of legacy, it’s a notion that permeates all parts of this industry through all sorts of stakeholders. In Makers and Innovators, I take a look at how Patagonia’s Worn Wear campaign attempts to reshape the life cycles of the products they make.

As ever, a huge thank you to everyone who's been involved with this issue of BASE. I hope you enjoy and find inspiration in the following pages.

Chris Hunt, BASE Editor

7

An interview with George King who’s made a name for himself climbing some of the world’s largest structures. And then jumping off them.

FINDING FLOW

WITH THE SHARD CLIMBER

Intro and interview | Hannah Mitchell Photos by | George King

MAIN: I struggle finding the best words to describe ‘why’ for projects like this. In the words of Philippe Petit (the man who walked between the twin towers using a tightrope): ‘there is no why.’ Simply put, for the Blade Runner project, this was just an idea that had been annoying me for two years.

In the early hours of the 12th of June 2023, George King left his hotel room in the South Korean capital of Seoul. Equipped only with climbing shoes and a small backpack containing a single parachute, he was heading for a lifetime dream: the Lotte World tower, which he would climb before BASE jumping from the top. At 7.56am, he reached the 72nd floor of the 123-storey, 555m tall building, where he was detained by the South Korean authorities, his attempt thwarted after a security guard in the building spotted him through a window.

I spoke to George from Seoul, where he faces legal trial for his urban free BASE attempt. Steeled for a conversation with the Shard Climber (a title he earned in 2019 after his ascent of the UK’s tallest building), often presented by mainstream media as a wreckless, slightly unhinged adrenaline junkie, I was pleasantly surprised by George’s cool, level-headed rationale. Perhaps even more surprising, was the relatability I found to his reasoning for climbing some of the world’s highest structures – and jumping off them.

You’re currently ‘stuck’ in Korea awaiting trial – how’s it going out there?

There’s actually something very romantic about my current situation. It's this feeling that I'm sort-of stranded, but I'm also very free. Normally I have so many responsibilities, so many things for me to uphold with what I do and what I need to achieve. But it's almost like all that's been put on pause. I'm left to roam, and although I’m physically constrained, in my mind I'm free.

Had you anticipated this being a potential outcome, when you set out to climb the Lotte World Tower?

Absolutely not. I set out my ambition – and it is still my ambition – to climb to the top, jump off, land, and flee the

10

ABOVE: Ascending Europe's tallest rollercoaster with the intention of jumping off from the top. What we call urban freeBASE. The day before on my morning reconnaissance I saw that they do a test ride at 7am… I was climbing at 6:30am. What if they did the test ride a bit earlier?

“All those thoughts and that chatter just goes –it's a beautiful state of mind.”

country without a trace. Unfortunately, I failed in doing so. Retrospect is a haunting thing, but also it's a window into wisdom. Now I know there are so many things I could have done a bit differently, but really what happened is, I just wasn't quick enough and the authorities were able to trap me with a window cradle. That put my dream to an unfortunate end, and I was devastated when it first happened. I’d dreamed about this idea for so many years – urban free BASE – to climb a building and to fly off it. I planned and trained for so many months, I had it in my head, it was almost like I saw it and it was already done in my head. It just didn't happen the way I saw it.

But over the last couple of weeks, I've not had my phone, and I've been able to really think about things. I've seen so

many lessons in this whole process which I would never have seen if I hadn't failed. So I've actually come away from this whole experience with a new level of wisdom, far more than if I had succeeded. I'm actually in some way quite happy with the result now.

Can you give a bit more of an insight into that day – when you set off to climb the tower? Obviously there's an extensive planning process and the dream started years ago, but how did it feel on the day when you woke up, knowing that it was all finally materialising?

I felt extremely confident. Waking up that morning, walking to the tower from a hotel just a mile away from it. It was still nighttime, still dark. I’d planned to start the climb at sunrise.

One of the first things I’ve noticed in the past with all the buildings I've climbed in Europe is the level of humidity. So the sweat was dripping off me as I was walking to the building, and I was like, ok, this could be an issue, because I've never experienced something quite like this before. So that was one thing in my head, but besides that, I was invigorated with energy. I've had times in my life where I've really felt fear about something I'm going to do. But it wasn't the case with this, I was actually just soaking it all up and very excited to begin.

And if you had woken up and you had a bad gut feeling, is that something that you're very tuned in to? And if something felt slightly off, would you say: ok, not today, or would you push through it?

Because I'd actually planned for this one for quite some time, I think all that sort-of gut feeling, intuition stuff had already been done. I have had occasions in my life where I've been in London in the dead of night, about to free solo a skyscraper, no one knows but me, and I've had to walk away because of that gut feeling. Sometimes you can't really put your finger on what that feeling is, but you trust it because it's kept you alive this long. So yeah, there's absolutely been times where I've

11

ABOVE: One day I spontaneously went on the Park Inn rooftop for sunrise. Tilting my head over the edge, instantly the unknown dream I was looking for revealed itself: A building-to-building BASE jump from Berlin's tallest building.

walked away from a BASE jump exit solo, because I've felt something was wrong. You can't really explain why you must walk away, but often that feeling is enough.

Humans have been tuned into that gut instinct historically for survival, but I feel like nowadays, we live in this really micro-managed, health and safety kind of culture. Everyone's obsessed with blame. And we're almost completely dependent on something external to tell us what's a suitable level of risk for us. Do you think over time, humans have lost touch with their ability to register that gut feeling or to make their own risk assessments and judgments?

I think that's a really good way of putting it – I never thought of it that way before. I 100% agree with you. Our biology has changed since we were hunter-gatherers. And those sorts of instincts were the things that kept us alive. But because like you say, we live in this world where everything is very easy in the sense that you don't have to hunt your food, it's all done for you, then absolutely, you lose touch with that survival instinct and ability to judge risk.

I imagine for a lot of people that’s why when someone does something like what you're doing, for example, they just feel this sense of horror. They can't fathom being able to make that judgement themselves or take that risk. Definitely. It's a funny one, because what I do is so normal to me. A lot of people will say what I do is crazy, but the thing is, I've been inclined to do these things ever since I've been cognitively able to – ever since I've been able to think and feel and breathe. I've always done things which scare me and put me in this state of mind. So while for a lot of people it seems crazy, it's so natural and normal for me.

If you Google your name or look at reports in the mainstream media, the headlines are often daredevil, thrill seeker, or adrenaline junkie… how do you feel about those terms? Is there any truth in any of them or do you think it's just sensationalism?

I've had a lot of time to think about the connotations of those terms, it's just a very naive perspective. I understand how someone could interpret me as being an adrenaline junkie or whatever, but it is so much more complex. There are so many different parts to it.

Yes, I like the feeling of adrenaline, but I also love the process. I love the preparation, the details, the journey. It's not all about the adrenaline. So I can understand why people say that, but it’s far more complex. To the point that, even though I've spent my life trying to understand why I do the things I do, I still don't have a finite answer. I probably never will.

Within adventure sports or activities, there's often talk of this flow state that people experience. It's that feeling of calm in what is perceived as a risky situation. I think for a lot of people, it's quite hard to believe that free soloing a skyscraper, you could ever experience that clarity of mind, but is that something you experience when you're climbing?

TOP: It took approximately three weeks to find this particular turbine. Sitting above a remote valley without a cloud in sight, the setting fit the dream perfectly.

12

“A way for me to channel my internal energy into something positive.”

ABOVE: Freesolo on Tower Agbar, Barcelona: 15 minutes in aerial solitude, a stranger setting foot in another world, gazing down at the normality below. It’s mystical, like I’d entered another different dimension.

Absolutely. That flow state is actually far from what adrenaline is, it's total peace of mind. It's this tranquil energy you kind-of lose yourself in, you're like a passenger. You're not really thinking about what's going on, it's just happening. And for someone who has so-called ADHD, it's like, all those thoughts and that chatter just goes – it's a beautiful state of mind. I think I'm more addicted to that than I am to adrenaline and the euphoric thrill from doing what I do.

That flow state can be found in so many ways, it doesn't have to be climbing without a rope or BASE jumping or whatever. Artists can experience this painting, writers, businessmen, speakers; this flow state is available to anyone. I think the way to explain it is when your skill level and level of challenge are met at a certain point, and it puts you in a state where you're not so over-challenged that you're becoming dwarfed by the moment, and you're not so under-challenge that it’s less stimulating, but you're finding that perfect alignment.

I think in recent years, everyone has been really chasing that zen or mental health boost in some way, particularly relating to the outdoors or outdoor sports or activities. Do you feel like that state is helping you to process challenging internal or external factors?

100%, because if you were to take it away from me, then I would replace it with negative means. You know, alcohol, whatever. So yeah, it's absolutely a way for me to channel my internal energy into something positive. It gives me freedom, and also relief.

A lot of the criticism that you receive, particularly in relation to your most recent climb in Korea, is the use of emergency services resources in those scenarios. What are your thoughts on that?

Yeah, it's one I get a lot, and it's actually quite an unarguable one. I totally respect the emergency services on all levels and when I do meet them, they're not complaining, they're very respectful towards me and I'm always very respectful to them. We actually bond in a very interesting way. The way I perceive it, the relationship between myself and the emergency services has never been one which is spiteful. I understand the views of the public, wasting emergency services times and all the rest of it, and it is unarguable. But there's mutual respect always.

Humans have historically had a bit of a fixation on pushing boundaries and the limits of what they can do physically and mentally. What do you think it is that drives humans generally towards that? And what is it personally for you?

For me it's always the question of what I’m capable of. How far can I take it? Sometimes that can be crippling because it can take you into this obsessive mindset that can affect other areas in your life. You become so single-minded in seeing how far you can push it. That's something I've had to learn to control over the years. I can't speak for other people, but for me, it’s seeing how far I can push myself mentally or physically. It's curiosity for the unknown.

So once you leave Korea, where are you thinking of heading? Do you have a plan?

So I didn't achieve my dream of urban free BASE with this building, and for me, it's less about the building and more about the concept. So the dream is still the same – to climb and jump off a building. The next building I climb however I won’t bring the parachute. I want to just free solo a building, to get that momentum up again. And then once I do that, I'll pick a target, and I'll get it done. I don't know what that building will be, there's a long list! Will it be done by the end of the year? Potentially. It's hard to say absolutely, but within 2024, it’ll be done.

13

On two wheels or on two feet, spend any time in the forest and you’re likely to have come across mountain biking trails of some sort at some point. But how much do you really know about the life of a trail – how it got there, the people who built it and the land on which it exists?

14

Story and photography by | Tom Laws

The order of the cultivated clashing with the chaos of nature, the term wild trails means a lot and nothing all at once. Yet it’s just one way to describe a particular flavour of mountain biking. Wild trails have been part of the landscape for years, often hiding in plain sight, their locations kept as the loosest of closely guarded secrets by the pioneers of the sport. The best were built by riders with an understanding of the natural landscape – choosing venues which would avoid other users, that wouldn’t be washed away by winter storms, and would go unnoticed by landowners. The absolute best of these survive to this day, across the country, as classics.

Depending on who you ask, a number of these trails were willingly adopted or hijacked by the Forestry Commission and developed into the trail centres that we know today. Coed y Brenin, Glentress and pretty much any other managed set of singletrack started life as a collection of home-cut and often illegally crafted trails.

Fast-forward a decade or two and the trail centre has become the obvious gateway for many new mountain bikers. Starting from an easily accessible car park, a typical centre will have a number of waymarked routes of a variety of lengths and grades. Built to stand up to years of riders and weather, the trails will usually be stone clad, hard-packed singletrack, linked together by easily navigated existing forest roads. They’re a great way to get your fix. They have also brought mountain biking into the fringes of cities – Ashton Court in Bristol and Leeds Urban Bike Park both mean urban riders can grab a two-wheel fix in their lunch break. But for many riders, trail centres are just the beginning.

During the COVID19 pandemic, as riders sought to get more from their mountain biking experience, there was enormous growth in wild trail discovery. Forced to stay close to home, with time to explore, many were shocked to discover that their local hillside was already home to trails they never knew existed. At the same time fresh lines were popping up faster than ever. Add to the mix the popularity of apps like Strava, and it was becoming hard to turn a blind-eye to the vast network of trails or the scores of riders enjoying them, and in 2019 Natural Resources Wales sought to map the trails on their estate.

The bulk of this surveying was carried out by Dave Evans of Bike Corris, a rider with an understanding of the importance of these trails to the communities who build and maintain them. He took time to chat to the builders and riders and found both a community and a network of trails drenched in history. Certain wild trails it seemed were seeing far more riders than their sanctioned counterparts in the same valley!

15

“The idea of losing trails served to drive these dedicated builders deeper into the shadows and solidified a distrust of landowners.”

TOP: Ed Roberts on Skulls. The whole trail was lost in a night to a storm. Months of hard work gone in an instant.

ABOVE: Tom Laws enjoying the week of dust Wales is gifted each year. Photo © Sam Piper. FACING PAGE: Ross Lambie, Mid Wales.

At the same time, former downhill World Champion Manon Carpenter released her film, Trails on Trial which explored some of the issues around unsanctioned trails.

Until you’ve spent hours swinging a mattock, it’s hard to understand just how much work goes into the creation of a trail. With so much time and literal sweat invested into them, they become more than just ribbons of dirt, cherished by their custodians potentially for decades to come, and much of the riding community were becoming suspicious of this sudden spotlight on previously secret trails.

Storm damage, erosion from riders, and conflict with other land-users can all conspire to bring an end to these trails’ existence. Add in the fear of a law-suit following an incident and it’s a wonder any survive at all!

Many of the unsanctioned trails in Wales are built in commercial forestry, many of which notoriously lack resilience due to the increasing number of storms we’re seeing. Recently one of the most popular trails in North Wales was completely destroyed in a single night, with such a network of fallen trees that there is little hope for its repair.

16

“Their locations kept as the loosest of closely guarded secrets by the pioneers of the sport.”

Potentially as destructive is the massive increase in riders using these trails. Over time, a trail will evolve and erode, requiring running repairs or even a total rebuild, and at times the maintenance can be more than a solitary trail builder can cope with. This can lead to animosity between riders and those who build and maintain the trails.

In the past, fearing litigation or worse, landowners have been quick to shut down unsanctioned trails on their land. This gave rise to a deep sense of paranoia that all could be lost, seeing trail builders enter a game of cat and mouse with forest rangers. On one hillside, a land manager could turn a blind eye to half a dozen trails, whilst in the next valley, an overly fastidious worker would have a dozen healthy trees felled across a trail.

There are however next to no examples of lawsuits against landowners for injuries while riding such unsanctioned trails. The consensus seems to be that if you have chosen to ride it, any injury you might sustain is your sole responsibility and fault. Crashing into a dog walker or some other third party however, would be much more of a problem! Gaps at speed over footpaths, fast or blind exits and poorly constructed features can all cause issues.

The idea of losing trails served to drive these dedicated builders deeper into the shadows and further solidified a distrust of landowners. Clearly it was time to form relationships with landowners to secure the future of these trails.

By forming organisational bodies that can formally manage some of these trails, riders are hoping to ensure that they are not only protected, but also enhanced and developed. Through the coming together of the community, there is hope that these issues can be better managed both within the riding community and more formally with landowners to ensure the legacy of these riding spots is secured for future generations.

One such organisation, working towards a management plan for some of the area’s most popular riding spots is Trail Collective North Wales. The key thing that they are keen to stress is that they are not setting out to take credit for any trail builder’s hard work – a lot of the trails in the area can be attributed to the countless hours of a minority of builders. Instead, they aim to act as a single point of contact for landowners, riders, and trail builders – making it easier to ensure that trails are maintained.

Should an issue arise with a trail or feature, the organisation will also be able to act as the first point of contact for landowners, allowing them to liaise efficiently with trail builders to reach a solution. Trails that might have simply been felled over in the past might simply require a tweak to slow the exit in order to be tolerated. Collisions with other forest users could be prevented by the implementation of clear signage on the most popular trails. Why you would want to try and walk a dog down a rowdy bike trail however, is beyond me!

Across the small number of trails under their management, TCNW also looks to facilitate public maintenance events. These dig days not only allow the original trail builders access to help to keep their trail running great, but would allow riders, who previously felt unable to take part, the opportunity to work alongside skilled and experienced trail builders, even paying back a little for that ride perhaps! And as more riders develop a greater appreciation for the hard work and dedication they require, the hope is that we’ll foster a deep respect for the trails and the spaces in which they exist.

So where does this leave us at present? Across Wales, TCNW and other organisations are working on management plans to present to landowners. But our trails are always in need of some love, so here are a few things you can do to help.

1. Find out if your riding area has a trail group associated with it, and reach out to them.

2. If you know who the builders of your local trails are, drop them a message and see if they need a hand, or maybe a beer. Their hard work means you have somewhere to ride.

3. Should you happen across a trail builder on a ride, take the time to stop and chat, maybe even offer to swing a mattock for a few minutes. More often than not they have sacrificed a bike ride to build something you are riding.

4. When you ride, think about the impact you are having. After rain some trails can really suffer from heavy traffic. It’s always worth using resources such as Trailforks to find out if there are any closed trails where you are planning to ride.

5. Enjoy your access to wild places responsibly. The team at Trash Free Trails have great sets of resources to help you add some purposeful adventure to your ride.

For further reading check out trailcollective.co.uk and trashfreetrails.org

17

CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT: Wild trails don't have to be sanitised to be accepted by landowners – Dom and The Lion deep in a North Wales classic; It's not just the trails that are wild. Marv Davies pulling faces in Mid Wales; Clare Mitchell relishing another superb trail in Dyfi Forest.

EDGE OF SANITY

Story and photography by | Danya Schwertfeger

Story and photography by | Danya Schwertfeger

Unimpeded by landmass, with huge storms circling these lower latitudes, the Southern Ocean is notoriously home to some of the world’s most treacherous waters. So, considering his own disdain for sailing, agreeing to join a six-week sailing expedition in Antarctic waters, following in the footsteps of Shackleton, was a surprising choice for photographer and filmmaker Danya Schwertfeger.

ABOVE: My buddy Dominik Petel during one of our three-hour shifts at some time in the morning heading through a rather windy section.

ABOVE: My buddy Dominik Petel during one of our three-hour shifts at some time in the morning heading through a rather windy section.

Early one morning, I'm alone on shift at the helm of the boat, somewhere in the middle of the Southern Ocean. As the rest of the crew sleeps, the cold wind and rain blasts me from the stern but the music blasting in my headphones is enough to lighten my spirits. As the boat sways rhythmically, Anemone by The Brian Jonestown Massacre sets the perfect vibe. Suddenly I’m pushed off-balance, tilted 45-degrees. As the boat rights itself, another wave slams into us from behind and before I know it, I'm waist-deep in water. Another tilt, this time nearly 70 degrees. The chill of the Southern Ocean rushes past, and I have a stark realisation. Lost at sea is inevitable. This might just be how it ends.

20

CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT: Waiting for better weather in the South Orkneys; After the first person on the rowing boat had been rescued the rowers were pulling two-man shifts; Looking down at a herd of sea lions, basking in the sun; Scottish adventure photographer Ewan Harvey, in the evening light of an exceptional evening in Antarctica; Angel investor and adventurer Stefan Ivanov during one of his shifts on deck; Icebergs floating in the Southern Ocean; Glacier, South Orkney on Orcadas Base; Fur sea lions in what was going to be a blizzard.

Then, a jolt. My harness pulls me back. It's connected to the boat. I'm saved. As water drains away, adrenaline surges, replaced swiftly by euphoria. With white knuckles, I grip the helm once more. Sailing never felt more thrilling.

A shout from below abruptly breaks my elation. ‘What did you do!?’ Ewan's outrage is unmistakable. He appears for a moment. ‘We're flooded!’ I dismiss his panic as an overreaction. Unfazed, I finish my shift.

At this point, I’ll rewind to where this adventure began: Ushuaia, a surprisingly populous city of 80,000 people. This was our launch pad for the six-week journey to the planet's end. Here, I'd meet my 13 companions – Adam, a camera operator from New York, Ewan, a Scottish photographer, Captain Piotr, three sailors, and six athletes – within the next 24 hours and for the next three days we’d prepare our gear.

Eventually, we were introduced to Selma, a 20-metre, battle-hardened ketch. Its worn sails and robust rigging were reminiscent of the Millennium Falcon – a veteran of countless adventures. Home for the next six weeks.

Despite unsettling tales of boat sinkings, the Drake Passage welcomed us with mild, two-metre waves and northerly winds. After six days at sea, we arrived at King George Island.

Here, we split with the rowing team we were here to document, and at the Polish Scientific base, we realised the high value of fresh produce. With just a box of bananas and some veggies, Captain Piotr secured us showers, accommodations, and meals.

Within two days, the team cleaned and prepped the eightmetre rowing boat, packing food, water, and necessities for the next 20 days at sea. The boat had two cabins that could shelter five, meaning that while the rest huddled for warmth, at all times, one crew member would have to endure the harsh weather.

With rudimentary quarters, essential electronics, and survival gear in place, we embarked, following in Ernest Shackleton's footsteps, following the rowers as they set off to traverse 900 nautical miles to South Georgia, putting into practice years of planning, countless Zoom calls, and substantial investment.

With the first strokes underway, the energy on both boats was ecstatic… which lasted all of about 20 minutes before the

21

“The constant sway of the waves makes six-hour breaks feel eternal, yet rest remains elusive.”

cold set in and we were forced to shelter with tea and huddle for warmth.

Life aboard Selma is simple but gruelling. We sleep until we can't, eat, and then sleep again. The constant sway of the waves makes six-hour breaks feel eternal, yet rest remains elusive. With the boat's batteries failing and the heater useless unless stationary, survival trumps routine.

In the frigid interior, my sleeping bag rated for -7 degrees is no match. Navigating the narrow corridors without bumping my head becomes a daily challenge as I find comfort in the trip to the kitchen, brewing tea, and the never-ending campaign to dry my slippers.

I relieve Dominik at the helm, where our task is capturing images of the rowers or passing icebergs. One rower seems particularly miserable, slumped over his oars. It's a mystery to us on Selma, but seasickness is the suspected culprit. As my shift ends, I grapple with my own meal, hoping not to douse my already overworn trousers.

Our surroundings are a monotonous expanse of waves, punctuated by the occasional albatross or updates from the rowing boat. Attempting to read or watch movies just aggravates our seasickness. We sleep.

By day three, slumped over his oars, Mike, our seasick rower, resembles a croissant. We pass the formidable Elephant and Clarence Islands and indulge in fantasies of conquering their untamed summits.

Sailing in Antarctica is a paradox – breathtaking wildlife sightings clash with a burning desire to escape the relentless waves, the cold, and the wet. While I yearn to relish every moment in this awe-inspiring wilderness, reaching South

Georgia to conclude our expedition becomes my overriding focus. As each knot gained delivers us closer to the end of our journey, wind direction and its impact on the speed of the rowers becomes our obsession.

Day four takes a dramatic turn as a 4am wake-up call kicks off a rescue mission. Unable to keep any food down for the past four days, Mike is critically hypothermic. His tenacity kept him on the rowing boat until the point of physical extraction. Aboard Selma, we devote the morning to nursing him back to health, dwarfed by the enormity of surrounding icebergs.

By day six, a shift in wind direction prompts a change in our plan. Given the rowers' deteriorating physical and mental state, we're to aim for the South Orkney Islands, just oneday's sail away. The decision, obvious enough to us, is a bitter pill for the rowing team, forced to confront bruised egos.

22

“Breathtaking wildlife sightings clash with a burning desire to escape.”

At the Orcadas base, we're warmly welcomed by the Argentinian crew, their football-loving spirits high on their recent World Cup victory. The base is rudimentary but comfortable, equipped with a communal kitchen and shared bathrooms, its warmth a stark contrast to the harsh outdoor elements. The scientists, builders, cooks and cleaners live in what feels like a university halls of residence. Homemade liquor is their communal religion.

Having picked up the rowing team, the Argentinian Coast Guard's arrival marks our last opportunity to interview them. But in a whirl of rapid events, the team is whisked away by a warship, leaving us stunned and interview-less.

Days later, bracing for a stormy night with gale-force winds, we find ourselves anchored in the narrow bay of Signy Island. Retreating to the cosy cabin, we succumb to a nostalgic spell, regaling each other with tales over a selection of spirits.

Awaking collectively hungover, our mission for the day is to find grass for Piotr's scientist friend back in Poland. As we step foot on Signy Island, we set our sights on an unclimbed mountain, braving a perilous climb up a rocky chute. Our triumphant anticipation quickly deflates when we find the summit already marked by flags. Regardless, the adventure instils a sense of camaraderie and good-humoured absurdity.

Back onboard, Piotr, our serene captain, surrounds himself with the collected grass by his favoured sleeping spot. Despite its location by the helm and the constant chatter, he sleeps peacefully, sporadically monitoring the course and sail position with a single eye. A cup of tea or coffee from a crewmate is all he needs to keep his spirits high.

So here we are a few weeks into the trip, on our way home, still almost two weeks from Ushuaia. It’s 7am and I’m on the helm. I need not reiterate how a momentary lack of concentration and skill almost landed me in the Southern Ocean and almost cost me my life.

Climbing down into the cabin, I find the rest of the boat in chaos. Water floods in, the bilge pump in overdrive, tomato juice is splattered across the kitchen, and my oncedry cabin is awash with water. My electronics submerged, my bed drenched, and the contents of my 'dry bag' of clothes, a waterlogged mess. The crew had been too engrossed in damage control to notify me sooner. Side glances and a disappointed gaze from the captain were all I needed to realise my blunder.

With my poor sleeping bag damp and miserable, sleep became a series of brief 45-minute spells, punctuated by shivering awakenings and foot-rubbing sessions. After three of these cycles, I'd surrender to the cold, retreating to the pilot house to contemplate the ocean and count down our remaining days, returning to the dank depths of my cabin only when exhaustion took over.

Eventually, fatigue became overwhelming, and my existence was reduced to simply staring out at the ocean, counting down the remaining days. Sleep-wrecked days seemed endless. The key was finding a way to stay positive. Laughing, making pancakes for the boys and lifting their spirits became my escape.

Through the damp exhaustion, one fundamental truth resonated deeply: Sailing becomes your way of life. You don't just guide the ship, you commune with the elements, allowing the vessel to find its own path. The quietude of sailing, without motor, invites an intimate dialogue with wildlife while nature graciously reveals itself to us. This unique interaction is what makes sailing through Antarctica such an enthralling journey.

23

CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT: Looking down at the glacier in South Orkney; Ice cave looking at one of the many glaciers on Laurie Island, South Orkney; The whole rowing team at Orcadas base, had won 12 world records; Selma, our sailing boat with Arcadas base in the background. Waiting for permission to land; Antarctica locals.

GRAVEL LIKE A LOCAL: EXPLORING THE AUSTRIAN ALPS BY BIKE

24 IN PARTNERSHIP WITH

Story by | Katherine Moore Photography by | David Robinson

With more than 60% of the country’s landmass belonging to the Eastern Alps, Austria's stunning network of winding gravel roads, glacial rivers and high passes, could just be the ultimate Alpine destination for the adventure cyclist. To test the theory, gravel aficionado Katherine Moore teams up with Salzburg mensch-in-the-know Max Riese to discover what makes his home city of Salzburg the perfect one-stopshop for a long weekend in the saddle.

I’d been hearing all about the riding in Salzburg for years after one of my best friends emigrated there, so when the chance arrived to explore it myself, naturally, I jumped at it. Surrounded by mountains and the gateway to the Austrian Alps, it’s become one of the definitive European adventure hubs where a savvy international crowd has flocked. With gravel also really taking off there, I wanted to see what could be possible within a long weekend or a week’s revitalising break.

To get a proper feel for the place, I tasked Salzburg local (and trusted friend of BASE) Max Riese with not only sharing some of his most-revered local gravel routes, but also introducing me to a few of the key characters at the heart of the Salzburg cycling community.

As a known ultra-cyclist himself, Max has been instrumental in nurturing the burgeoning gravel scene here. His knowledge and passion for the area shines through, pointing out each peak, path, valley and hidden waterfall with stories having spent every free moment of the last 12 years exploring these mountains.

Max regularly rides with a crew of local pals, around half Austrian nationals and half international professionals, who have adopted Salzburg as their new mountain home. John Braynard is one such character. Hailing from the US, he now heads up global social media at Red Bull HQ and can certainly be credited with sharing the appeal of riding in Salzburg with a larger community.

When John arrived here 11 years ago, the scene was purely racing-focussed. With a keen eye for a killer image and a penchant for exploration over simply tackling passes as fast as legs and lungs would allow, he cultivated an alternative attitude to riding here, and has since taken many more along with him for the ride.

25

ABOVE: High mountain pasture gravel from Postalm. Even my steed is Austrian; a carbon fibre, custom painted 1of1 gravel bike from Mondsee.

Hopping on the bike really is the best way to get to know the city. While the baroque plazas are breathtakingly beautiful to ride around, we hauled up the steep cobbled climb on the castle-topped city mountain, Mönchsberg, for the best views. From this vantage point at eye level with the bell towers, copper domes, spires and turrets, you look across the old city and the patchwork of terracotta, slate and metal roofs.

Besides the urban centre, Salzburg feels genuinely relaxed, lush and green. Locals sunbathe and dip next to The Almkanal (the mountain water canal), gravel trails line the river and gorgeous estate parks are open to the public. There are plenty more quirky places to visit and where local riders love to hang out, from speciality coffee at Kaffee Alchemie to FUXN’s buzzing beer garden.

Max assures me that a rider’s tour of Salzburg wouldn’t be complete without a trip to Fanzy Bikes. Behind the bright mural frontage and racks of retro mountain bikes stands Jakob Deutschmann, all bouffant, moustache, unbuttoned overalls and a broad smile. Much like his character, the shop is anything but ordinary; kitted out only with salvaged old bikes given proper TLC and a new lease of life.

In the time it takes to sip an Almdudler (often considered the national drink of Austria) a dozen people have popped in for a drink or a quick hello. Besides offering something truly unique (and frankly a little barmy by modern standards) it’s clear that Jakob, alongside Dani Herlbauer (another cycling nut who runs local shop Bikepalast), is a much liked and respected player in Salzburg’s vibrant cycling scene.

Sticking with a theme, my base for the week is Hotel Jakob, a pioneering sports hotel on the edge of Lake Fuschl, just half

GLOSSARY

-see: lake

-tal: valley

-alm: pasture

-weg: way

-berg: mountain

-ach: river

-burg: castle

-wald: forest

26

“Surrounded by mountains and the gateway to the Austrian Alps, it’s become one of the definitive European adventure hubs.”

CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT: Sipping a pre-ride coffee by the river at Kaffie Alchemie; Jakob Deutschmann of Fanzy Bikes with one of his current retro ride; Cooling off with a dip in the Almkanal; Skirting the shores of Fuschlsee.

60%

an hour from Salzburg and also the site for Red Bull HQ. A passionate cyclist and triathlete himself, fifth generation hotelier Jakob Schmidlechner saw the opportunity to create a dedicated offering for cyclists here in the mountains.

Equipped with everything you might need from secure bike storage and hire to sports massage offerings, Jakob and his team have not only created a cyclist’s paradise in this mountainous adventure playground, but also fostered a community of like-minded souls.

And the riding? Well, while you can access plenty of excellent gravel trails directly from the city, the out-and-back can add significant mileage if you’re planning on exploring deeper into the mountains. Thankfully, Salzburg is super well connected with trains that offer regular services and free bike carriage, so you can save your legs for the long Alpine climbs and sublime balcony gravel roads instead.

Here are four of Max’s local tried and tested favourites that you can use to form the backbone of a trip, whether that’s a long weekend or a full week of gravel riding in SalzburgerLand. You’ll find everything from an easier loop straight from the city to longer days climbing to high Alpine pastures, with refreshing lake dips and many traditional mountain huts to stop by for the authentic Austrian mountain experience.

27

MORE THAN 60% OF AUSTRIA'S LANDMASS BELONGS TO THE EASTERN ALPS

Route The Haunsberg trail

Route Strubklamm

to Gaisberg Figure of Eight

↗ 67 km, 650 m climbing, 4.5 hours

↗ Intermediate

↗ POIs: Haunsberg viewpoint

The perfect acclimatisation ride for your first day, the Haunsberg trail eases you into the vertiginous landscape with lush green hills rather than high mountain passes. Don’t think that you’ll be sacrificing scenery though; the views from the summit are arguably the best around Salzburg.

After the climb and a fantastic section of flowing singletrack trail, you reach a tiny chapel and crown-topped monument commemorating the visit of Emperor Joseph II in the late 1700s. To the east, there’s the iconic shark-fin mountain of the Schafberg, while the glacial peak of Dachstein can be seen beyond. Closer-by, the mound-like mountain of Gaisberg on the edge of the city is the go-to climb for local cyclists before or after work.

Looking north-east, there’s a gorgeous vista over Seenland, the Salzburg Lake District. Turn 180 degrees for a more agricultural scene, Germany’s Bavaria clearly seen over the snaking River Salzach.

INSIDER TIP: There’s a perfect reason that this is one of Max’s favourite rides to do before or after work. An early start is rewarded by a glorious sunrise over the mountains, while sunset is savoured over the German border before a delicious twilight descent back to the city.

↗ 46.8 km, 900 metres climbing, 4 hours

↗ Intermediate ↗ POIs: Hintersee, Vordersee, Felsenbad and Strubklamm gorge

Starting from the Alchemie coffee shop on the banks of the Salzach River, this figure of eight loop gives you the option for a shorter loop totalling 27km, or the full double loop taking in two iconic lakes and an outstanding balcony road through the Strubklamm gorge.

Soon out of the city, serene forest gravel tracks lead you to Koppl, before riding beside charming old water mills and lush pastures. From Ebenau the second loop begins, with flowing tarmac interspersed with thrilling gravel sectors leading you through Faistenau to the edge of Hintersee. Pop off your socks for a refreshing paddle.

INSIDER TIP: For a more secluded swim spot, head to Felsenbad a little further along, with a spectacular series of natural pools carved into the rock bed of the river.

A real treat is in store for you after you pass the Vordersee, as you continue onto the supreme tarmac road through the Strubklamm gorge. The road is pure bliss, though you’ll want to stop by the side of the quiet road to take in the magnitude of the sheer rock faces surrounding you.

Forested gravel tracks form the final climb with some testing gradients of up to 15%, though you’re mightily rewarded while descending on tarmac between wildflower meadows back towards the city.

28

With thanks to Hotel Jakob for providing accommodation during this trip.

↗ Learn more at Austria.info

Route Alte Postalmstrasse

Route Lake Seewaldsee

↗ 69.4 km, 1,620 metres climbing, 6.5 hours

↗ Advanced

↗ POIs: Old Postalmstrasse gravel climb, Huberhütte mountain hut, Postalm pastures

Featuring one of the most scenic old pass roads taking you up into Austria’s largest Alpine pasture, this route is truly worthy to be named the queen stage of any SalzburgerLand gravel riding holiday. From Salzburg, you can take a 30-minute local train directly to Golling with your bike that delivers you straight into the heart of the mountains. The first climb of the day sticks to the pristine tarmac heading west. The main event begins when you reach Pichl, where the old road up to Postalm starts. With the modern, tarmac toll road now on the other side of the Einberg, you can enjoy this 16-kilometre gravel track in peace, taking in the many waterfalls along on your ascent.

The last push up to Huber Hütte gets pretty steep, but it’s certainly worth it. The gravel doubletrack snakes up through the pasture, Fleckvieh and Pinzgauer cattle nonchalantly grazing, cowbells tinkling.

INSIDER TIP: There’s a generous menu of local specialties on offer at the hut, which is one of the oldest on the Postalm. Kaspressknödelsuppe, a sort of cheesy bread dumpling served in a broth-like soup, comes highly recommended.

After refuelling, it’s time to relish the incredible descent from 1,350 metres back down to the Lammer Valley, this time taking some sublime tarmac on the toll road, Postalmstrasse. The single carriageway descent twists and turns as you head down through the forest and through more farm pastures, weaving between traditional mountain chalets. You’ll struggle to keep your eyes on the road though, with the spectacular jagged silhouette of both the Tennen Mountains and the Gosaukamm range’s high peak of Bischofsmütze — the Bishop’s Hat — before you.

↗ 39 km, 940 metres climbing, 3.5 hours

↗ Intermediate

↗ POIs: Aubachfall waterfall, Lake Seewaldsee, Auerhütte mountain hut

Glorious gravel, breathtaking mountain views, a serene lake, waterfalls and the traditional mountain hut experience; the Seewaldsee loop really does have it all.

From Golling train station, an easy journey out of the city, you take the gravelly bike path through the Lammer Valley to awaken the legs. After Volgau there’s a short detour to visit the impressive Aubachfall waterfall which you simply can’t miss.

Here the ascent begins in earnest, with some classic tarmac Alpine hairpins that gloriously crumble into a gravel track after the farms. Not only does this doubletrack offer marvellous mountain views as you climb, but the sheer rock face beside you is a mighty sight in itself.

Seven kilometres after the waterfall, you earn your first sweet glimpse of Lake Seewaldsee. Much unlike the expansive, bright aqua waters of Lake Fuschlsee, pretty Seewaldsee is modest in appearance. The lake’s edge laps over onto the pasture, creating a marshy margin flanked by pine forests. It truly is a hidden gem up here, and reaching it by pedal power makes that feel all the more special.

Auerhütte sits proudly just above the lake, offering its patrons — and wonderful menagerie of livestock — spectacular views over the water. Whether you’re in need of a hearty meal or something a little lighter, there’s plenty of traditional Austrian cuisine to savour here. I opted for the Topfenstrudel, best described as apple strudel meets egg custard tart. Divine.

Complete the loop back to Golling by descending through the enchanted forest on the smooth sliver of paved road. Pastures, chalets and farmsteads set the scene for your final descent; pure joy in the shadow of the Tennen Mountains.

29

WE ARE ALL PROTAGONISTS

30

Story and photography by | Ashley Stewart

2023 marked the tenth year of The Speed Project : an unsanctioned 300-mile running race from Los Angeles through the Mojave Desert to Vegas. There are no rules, no prizes, no spectators, and no set route to follow. At the starting line on Santa Monica Pier this year, was a relay team of eight women – none of whom had previously met. What could possibly go wrong?

We were a team of fourteen. Two filmmakers, four support crew, and eight runners, who set out to run across Death Valley over the course of two and a half days. Fuelled by gummy bears, sports gels and adrenaline, we came together as complete strangers from all over the world. Most of us had never even heard of The Speed Project until we were asked to join the team.

Creative, role model, inspiration, leader, and a friend to each and everyone of us; an accurate description of Tilly doesn’t come easily. Carefully crafted and based on our individual strengths, weaknesses, goals, stories, and personalities, she was the force behind our team. Somehow she knew that the fourteen of us would be the perfect fit.

Setting out across this barren land with only cacti in sight, the agitated, aggressive, stray dogs stalking the runners had us on edge. The quietness lingered in the midnight air, and we drove closely to the runners at night to ensure their safety as we ran through deserted towns.

It’s pitch black and there’s nothing to see but the glowsticks bouncing along with the runner and the headlights of cars whizzing through the darkness. Exactly where we are I’m not sure, but we’re a long way from home. The sun peeks out over the mountains and a warm orange glow with a purple sky leads us into the morning. We leave the darkness behind us.

Half asleep, half delirious, as night turns to day, we’ve got Dolly Parton on repeat, pumping loud from the speaker. Collectively we belt out 9-to-5 at the top of our lungs as Meera paces on. Despite the fact they still won’t see a finish line for hundreds of miles, the smiles on the faces of these women are unwavering. Their joy is infectious and as they continue to put one foot in front of the other, a sense of hope replaces the restless butterflies in my stomach. I’m hanging out the side of the minivan window, shooting the runners as the new day instils a fresh energy in us all following the attrition of the night.

The dawn colours are at their most vibrant and it’s Tilly’s turn to run. She chooses the music that blares out the speakers and this time around she's practically flying. I can’t hide the smile behind my viewfinder. Tears trickle down my cheek as I realise my privilege, not only to be in this moment, but to be able to capture her beauty. I’ve never witnessed a smile so big and it hits us all. Our hearts warm as we bask in this magic. With the sun cast upon her, cheers from the window, a strong stride, I photograph Tilly in her truest form. I can't believe I’m here.

I’ve never been a part of anything like this. I wasn’t there to run but to provide support alongside three incredible women. We took turns to drive the RV through the night, wake the team in the early hours, craft the ultimate peanut butter and jelly sandwiches, refill the water bottles and document those extraordinary moments. In the end it was so much more than that. Joining this team for 300 miles, we shared their highs and lows and the battles against sleep deprivation, a teammate as well as a supporter. I am so honoured to have witnessed the triumphs of all these women.

31

MAIN: As the sun started to rise Tilly felt elated. The right pace, the right song being played out the van window, and warmth hitting her skin. The team had just finished running hundreds of miles through the cold desert night.

ABOVE: Esme, Eden, Shelly, and Ocean link hands to cheer Eden on as she decides to push on and run another mile uphill.

TILLY GOMPERTS

Running is about mind and body, trust, dedication and intention. It takes place within us and therefore it is not anyone’s right to dictate how, what, where it is done, what it should look like, and who does and does not belong.

I wanted to create a team that might not be expected or be presumed able to do something like this. Everybody on this Earth has the capacity to tap into and experience the magic that running can bring, if their environment allows them to. For me, The Speed Project is about creating that environment, challenging the stereotype, demonstrating that this thing belongs to us all and embodying our mental and physical power, collectively. Running does not fit in a box. And neither do we. That’s why we can be creative in our expression, we can be artists, scientists, politicians, medics, leaders, wanderers and dreamers. We can all be runners. We are all protagonists.

ESME AKINSTALL

It feels as if the whole journey has been building to this moment. Seven miles in the middle of the Mojave. A can of pepper spray is our only assurance.

It’s the first night and the moon is barely a crescent. I look away from our headlights and into the darkness. I notice how heavy it feels, omnipresent. We step into it. I am acutely aware that we are two women running at night into the unknown but there is no one I would rather have by my side than Shelley Howard. Her voice unwavering, she is betrayed only by her shaking hands.

24-years of learned experience screams at me to turn around. We run. Soon the screaming dulls and there is nothing but the sound of breath and falling feet as we surrender to the desert.

32

MEERA JOSHI

Although they were just minutes at a time, the moments we experienced crossing the desert, will feed the days, weeks and months and likely years that follow us reaching the Las Vegas sign. One such moment was running as a group down a neverending hill into Vegas. But you can’t simply parachute into moments like this. We first had to spend the 48-hours prior, running through the dark, sleep deprived, battling the heat and the cold, turning strangers into lifelong friends. Only then does the thrill of the downhill pack truly kick in.

These are the moments that take me out of the daily grind of life, complex decision making, intricate fact patterns and the constant need to strategically plan. They remind me we are not in control. The world is full of unexpected adventures, I just need the willingness to try, put some trust in others and to keep running.

SARAH LEGRAND

Under the stars on a dead straight road, Death Valley surrounded us, the atmosphere was special, the experience was unique. I set off at cruising pace long enough to warm my legs and adapt to the dark. The first night scared me but this time it was different. My body had recovered during the

33

“Running does not fit in a box. And neither do we. That is why we can be creative in our expression.”

TOP: An inevitability of running in the dry heat, but ruptured blood vessels inside the nose barely slowed Tilly Grompert.

MAIN: The last few miles as a pack before reaching Vegas.

BOTTOM LEFT: Eden and Tilly embrace after the run.

day and I was in good shape for the night shift. Joanna, a wonderful woman from the support crew, was running by my side to reassure me and warn me when a car was approaching from behind. I was calm, focussed on the sensations, where I put my foot and my prosthesis, because but for the stars above me, my eyes were not distracted. My mind and body were connected. Little by little, I felt really good and I increased the pace. My legs were on fire. As if the stars aligned, the girls blasted the song This Girl is on Fire by Alicia Keys through the rolled down windows of the minivan.

The moment was magical. I felt so comfortable with my prosthesis, like I had my two feet again! Right-left-rightleft- no differences, no gap between the two strides. I was running and dancing with my arms. I felt free, limitless, fearless, confident and strong in my body; a fluid, neverending moment.

34

RIGHT: Ocean with tears of pride and fatigue swigs prosecco to celebrate her amazing accomplishment.

MAIN: Reaching a runner’s high, Tilly, Ocean, and Marianne run through the desert at full speed. Since this was one of the few no vehicle access routes they ran together through the desert all on their own. Listening to techno, looking stronger than ever.

INSET: The entire team had reached 500km at the finish line together. Bypassing the line of tourists, they ran straight to the sign where bottles of processco were sprayed all over the team in celebration.

EDEN BEYLARD

Born in the French Alps, I never thought too deeply about my relationships with the outdoors, until I actually challenged myself and started training for The Speed Project

My first run with Tilly felt like an awakening from the boundaries I had built for myself over the years, believing my body and my mind weren’t capable of such a crazy idea. Running is all about commitment to the plan and consistency and this is something I now apply in other areas in my life.

Another favourite moment is also the saddest because it kind of marked the end of this adventure: the final seven miles towards the sunrise, arriving in Las Vegas. We were all exhausted from a tough journey. I got out of the car to do a mile and then just thought ‘Fuck it, let’s do it! I’m stronger than I know. I can do whatever I want!’

Our team coach used to write in my weekly training plan ‘mind over matter’. I really wanted it. To go beyond all expectations and I knew my legs and heart would follow. In the end I did seven miles straight up hill, slow and steady. I found a state of peace and meditation, a deep calm and happiness, my heart rate was slow. After seven months of struggling and dedication, I had my first runner’s high. I made it to the top with my teammates, it was a special moment and even better to share it with these people I respect, who inspire me.

I witnessed greatness in The Speed Project, with great women being part of a team alongside marathon and ultrarunners. It was an emotional journey because I had the realisation that whatever my fitness level, I belong here with them.

35

“I was running and dancing with my arms. I felt free, limitless, fearless, confident and strong in my body; a never-ending moment.”

TRANSLAGORAI

“I have blisters on my feet, and my right heel oozes with blood. But as the sun sets behind the mountains, I’m overcome by a sense of gratitude.”

36

Story and photography by | Francesco Guerra

Stretched some 70km across the autonomous province of Trentino in northern Italy, the distinctive volcanic formations of the Lagorai mountains in the Eastern Alps, date back more than 275 million years.

Far more recently, this rugged landscape is one bound by bloodshed. In World War 1, these peaks formed part of a natural front line, and between 1916 and 1918 were the site of the notoriously torturous mine warfare. Here, high up in the mountains, the unforgiving terrain proved as cruel as the industrial arsenals the military units brought with them. After heavy snowfall in December of 1916, avalanches are understood to have buried as many as 10,000 Italian and Austrian troops in just two days.

With only one paved road dissecting it, today, the Lagorai remains one of the last truly wild places in the Italian Alps, where, besides the perfectly preserved sites of these fierce battlefronts, the footprint of humanity is almost totally absent. In July of this year, Francesco Guerra set out to trek the Translagorai, a thru-hiking route that crosses the entire range with more than 5000m of elevation gain.

It’s 5.30am. The sun is rising behind the mountains, projecting hues of orange, pink and red across the Adamello peaks as I watch from a small window of the Fravòrt bivouac, where I spent the night.

The previous afternoon, after just 4km, I was forced to cut the day short having reached the bivouac with the arrival of a violent hailstorm. I decided to stay there for the night, reworking the route, to squeeze the journey into four days rather than the original five I had planned. Due to the extreme heatwave in Italy, the weather was unstable, but ahead of me, three-and-a-half days of decent weather were forecasted before thunderstorms would return.

With the sun still behind the mountains, I’m already out on the trail with the plan to cover about 20kms. The air is still fresh, and morale is super high: it's the first day after all, and I still have no sores – how naive of me.

37

MAIN: Latemar Dolomites at sunrise.

ABOVE LEFT: First planned day, I got stuck in Fravort bivouac. I killed time reading and gazing outside but sometimes that’s exactly what it’s all about.

ABOVE RIGHT: Planning and replanning.

CLOCKWISE FROM BELOW: An old military barrack from the First World War; Hiking near Brutto lake, which literally translates as Ugly Lake. Before being engulfed totally by clouds, the last light of sunset hits my tent; Dolomites at sunset; Old and rusty barbed wire – leftovers from the First World War.

FOLLOWING PAGE: Sharing the navigation of a technical ridge at sunset with the only hikers I met during this journey.

38

I discovered Translagorai a few years ago, reading about a potential development project for these mountains. In order to stimulate tourism, local politicians proposed a huge restaurant with a refuge and a parking lot right in the middle of the range. But there’s a fierce sense of custodianship among locals, who led a successful campaign to oppose the plans. While for now, the idea has now been dismissed, considering the development and overcrowding of the Dolomites so closeby, I’m not confident it’ll always stay that way. Will I be one of the last lucky few to experience the true wilderness of the Lagorai mountains? I guess time will tell.

I follow ridge lines, traversing huge scree slopes at the foot of dark grey peaks, and head deep into the cover of lush pine forests. Finally, I reach Rifugio Sette Selle – a quiet refuge nestled in a narrow valley among the mountains – where I pause for lunch.

Over the next five hours, I met only two day hikers. Besides them and three hikers I’d met briefly at the trailhead the day before, there’s no one out here. My only real interaction was with a viper, that, with a stand-off on the trail, temporarily forced me to stop in my tracks.

As the sun starts to set and the air is sharpening, I arrive at the ANA Mangheneti bivouac. But from the gusting wind and my own steps on the uneven ground there’s no sound at all. In our hyper-fast, overly stimulating world, this peace is exactly what I was looking for. Silence and solitude at its best.

Cooking inside the cosy wooden bivouac, I hear voices outside. Before I know it, the place is assaulted by a group of 20 or more noisy teens who make it clear they’ll too be spending the night here. Talking with them, I discover that there's a simpler path also leading to that bivouac. I quieten the voice of my inner grumpy old man. I smile and get to bed, trying to sleep as my new roommates shout the place down.

With everyone else still sleeping, I let myself out at the crack of dawn. I walk as fast as my heavy backpack allows me, and soon arrive at Passo Manghen – the only paved road that crosses the Lagorai. Here, the landscape is grand, more open than the previous day. Mountain passes, alpine lakes, flourishing nature all around and, in the distance, the impressive grandeur of the Dolomites.

39

“What scares me most is hailstone, which this year in Italy have been big enough to destroy cars.”

Not far beyond the pass, I find the first traces of human passage. But it’s not footprints, not drawings on the rocks, not even bones. Instead, these are the mementos of the worst traits of human nature. Military barracks, rusty barbed wire and metal scraps are strewn across the landscape, long trench lines built on hillsides, mountain passes, or perched on cliffs.

The legacy of these mountains is one defined by the 1st World War, where Italian soldiers fought against AustroHungarian forces, both sides living, fighting and dying on these rocks for what must have seemed never-ending. Stood here amongst the silence, it’s hard to imagine the gunfire, grenades and the blood-curdling screams. Perhaps I’ve found the limit of my imagination, or maybe it’s my subconscious, unwilling to break the tranquillity, not even in my mind.

It's about 2pm when I meet Sandro, Arianna and Matteo on the trail, the three hikers I’d met previously and I decide to join them for the rest of the afternoon. Together, we traverse steep, stony passages, climb on steel cables and scramble on scree as we navigate the most technical terrain of the Translagorai trail. Approaching the final alpine pass, thick, low clouds close in, and we are wrapped in a cold, white cloak.

Upping the pace, I suddenly realise I’ve lost them. Too concerned by keeping the speed that I hadn't paid attention to anything else. I pause for a few moments but decide to keep moving, I pause for a few moments but decide to keep moving, knowing that rather than risking getting lost myself, it's better to get to safety and then wait for them or make a call for help.

I reach the mountain pass and begin the steep hike down the gravel path, eventually re-emerging from the clouds. Almost at the camping spot, I turn to see their distant silhouettes descending from the mountains. I give them a wave, and prepare camp for the night.

Before bedding down, I take a moment to stand before the landscape: my legs and my shoulders are sore, I have blisters on my feet, and my right heel oozes with blood. But as the sun sets behind the mountains, I’m overcome by a sense of gratitude. I know I’m lucky to experience such a magnificent place in all of its untouched purity, all too aware that it won’t remain this way for long.

The next morning, I cheer my fellow campers as they prep their gear for the trail, and kick off the day solo. I do my best to ignore the pain in my feet, but find myself checking the route

“Its beauty just stood right there, a wild island of stunning

stunning mountains, detached from the hand of greedy men.”

for the first possible escape into the valley. I was prepared to fail. Happy to surpass my ego to accept my fallibility, I could have abandoned the hike with good grace. But a voice inside me wouldn’t let it go. You can't abandon the hike for some sore feet. Come on, you can do it, I heard on repeat.

I pass Lago Brutto which literally translates as Ugly Lake and dwell on how this small beautiful alpine lake sat like a gemstone in this perfect spot had earned itself such a name.

At some point in the afternoon, I noticed that somehow, as if by magic, my body is no longer sore. I reach a signpost indicating a one-hour hike from where I am to the next bivouac: I time it, reaching it in 45 minutes. The components of my body, working together in unison, no longer protesting the long days in the mountains.

Waking at dawn, I have decisions to make about what lies ahead. I’m keen to avoid potential thunderstorms, so with rain forecasted, I need to be careful. What scares me most is hailstones, which this year in Italy have been big enough to destroy cars. I play it safe, choosing the lower path that runs along the hillside of the mountains. Like the previous days, the route is a variation of scree, gravel and high grass, and

before long, my feet are soaked through. I’m moving fast, but I take time to indulge a little, to admire the fauna of these surroundings, the toads, marmots, chamoises and horses.

Akin to driving on a straight, familiar, highway, on the final few kilometres of the trail, my mind has already wandered elsewhere. As Norwegian explorer Erling Kagge writes in his book Silence: ‘Being on the road almost always gives more satisfaction than arriving at your destination. We prefer hunting to the prey.’ I feel a deep sense of anticlimax as I arrive at the end of the trail. Unsurprised at this lack of joy, I was exhausted, eager to find a shower and something to eat other than dried rice.

In the four days I spent on the trail, I crossed paths with just ten other hikers. The phone signal is poor and often absent for hours and there is barely a sign of human development. Its beauty just stood right there, a wild island of stunning mountains, detached from the hand of greedy men. My only hope for Lagorai is that it will remain this way: a fragile and wild environment to be experienced on its own terms, for us and for the generations to come.

AT HOME ON THE WATER

In the comfort of the wilderness that shaped her, with a canoe, a tent and a simple objective, Carmen Kuntz ponders and paddles her way across four lakes where she revels in the simplicity of solitary adventures and considers what ‘being at home’ means to her.

Only a thin layer of mesh and nylon separates me from an army outside. The pine-infused summer air is vibrating with mosquitoes, swarming the mesh and bouncing off the tent walls, trying to find a way in. But the zippers are closed tight, and a breeze off the lake cools me as I prepare for the luxury of a pre-dinner nap. I lay back and close my eyes. A tent is a wonderful tool. As a kid, my tent was a place of secrets, a private place to hide out in the forests of rural Canada. Somewhere I could practise survival skills, play pretend and get lost in daydreams. Today, a tent offers a similar kind of refuge, yet the security a tent provides extends past protection from blood-sucking insects. Somehow, being in a tent I feel safe. Even though I’m alone. I have the entire lake to myself – the nearest person is probably on the next lake, more than five kilometres and one portage away. This kind of solitude is why I’ve come home to Algonquin Park in southeastern Ontario. Every day when the sun descends behind the jagged tree tops of the gnarled white pines, I climb into my thin fabric dome, I feel protected. And I feel at home.