5 minute read

CRANK UP THE WAYBACK M ACHINE

The Bay Area’s rich baseball history predates the Giants and A’s by a looong shot

Ifthe baseball gods were to grant you a trip in their time machine to attend a game at any ballpark in Bay Area history, which one would you choose?

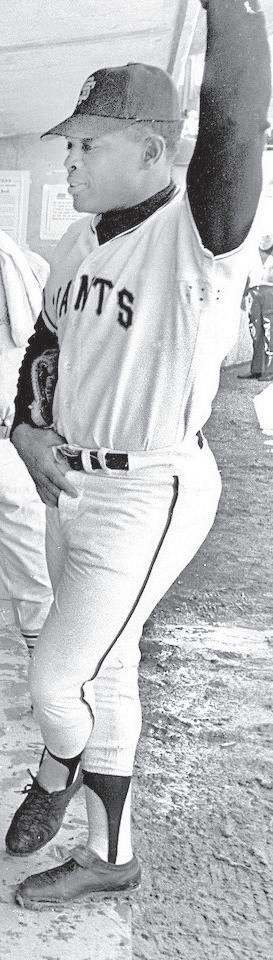

As a historian of ’70s baseball, I find the prospect of witnessing the Oakland A’s in action at the Coliseum during their dynastic “Mustache Gang” years incredibly alluring, and I’d gladly risk the possibility of frostbite to catch the flamboyant John “The Count” Montefusco on the mound at Candlestick Park during the 1975 season, when he won the National League’s Rookie of the Year award.

Going back a decade earlier, it would be pretty sweet to watch Catfish Hunter break MLB’s 46-year perfect game drought under the Coliseum lights on the night of May 8, 1968, or see Willie Mays, Orlan-

STORY BY DAN EPSTEIN

ILLUSTRATION BY DAVIDE BARCO

do Cepeda and the rest of that incredibly loaded 1962 Giants squad take on the New York Yankees at the pre-enclosed (and even chillier) incarnation of the ’Stick.

But while Giants and A’s history obviously gives us plenty of colorful and fascinating moments to pick from, the Bay Area’s rich baseball legacy began well before the arrival of major league franchises. The first baseball game in San Francisco may have been played as early as 1851, and the first “o cial” contest occurred on February 22, 1860, at a spot called Center’s Bridge, located near 16th and Harrison in the Mission district. That game, between the Eagles and Red Rovers, ended in a 33-33 tie, though the Eagles were awarded a forfeit win after the Red Rovers complained of shoddy umpiring and went home.

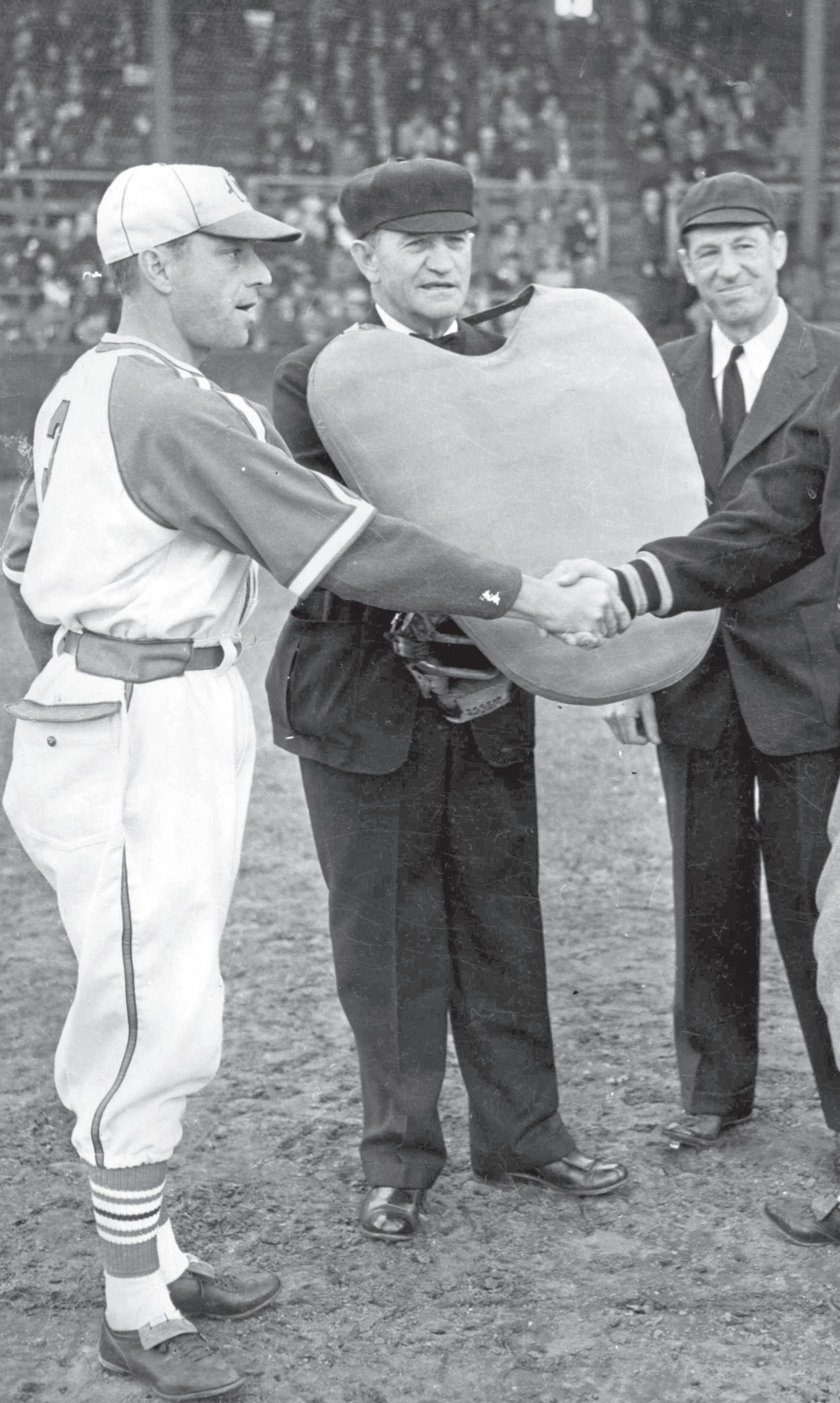

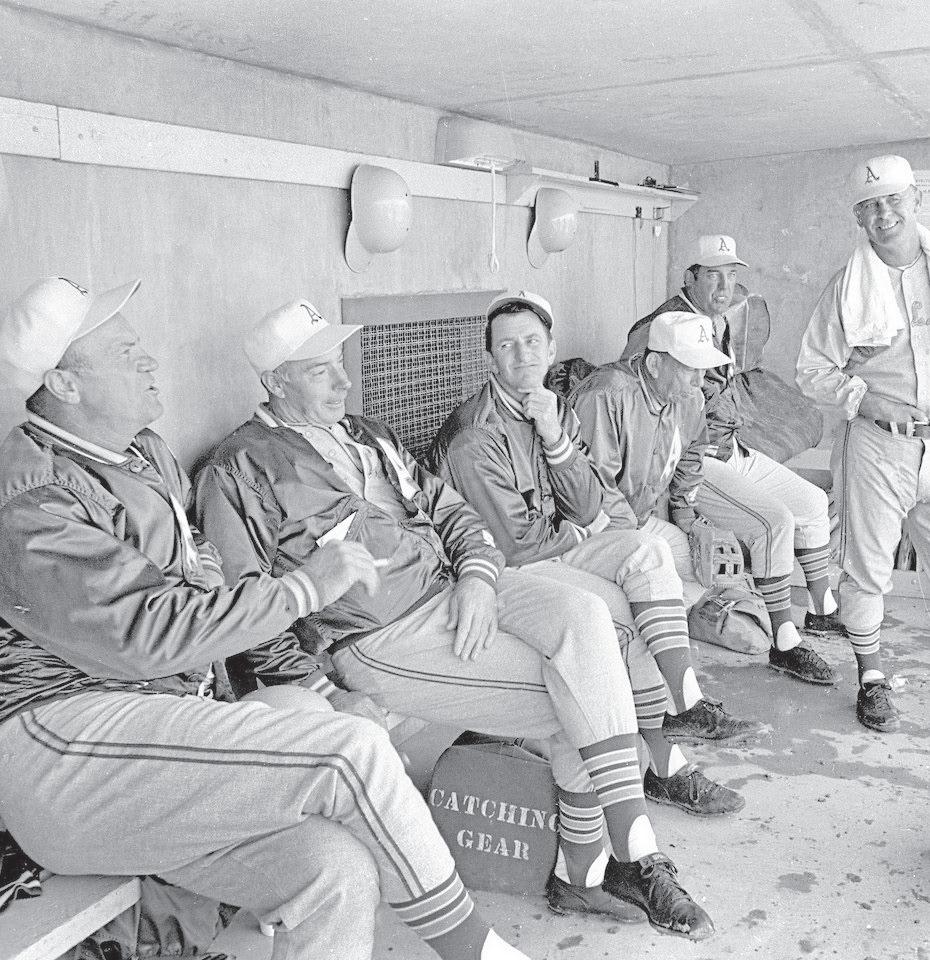

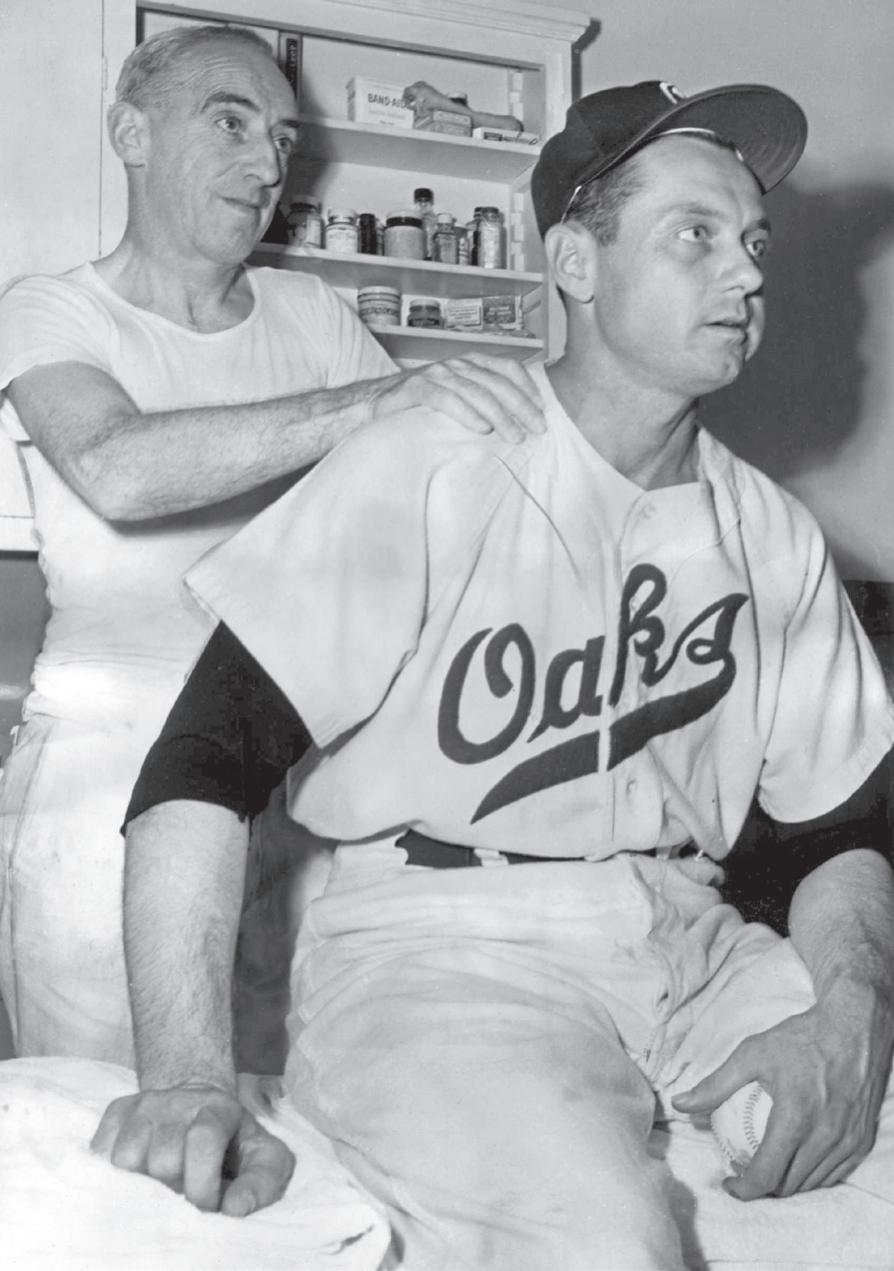

Opening game of the Pacific Coast League with the San Francisco Seals against the Oakland Oaks.

As baseball (or “base ball,” as it was known in those days) grew in local popularity, so did calls to establish uniformity of competition, and in 1866, the six-club Pacific Base Ball Convention became the Bay Area’s first o cial “league.” PBBC games occurred at a variety of sandlots in San Francisco and the East Bay, though the most games were initially played at the Pioneer Race Course, located approximately at Capp and 24th in the Mission — at least until Recreation Grounds, the city’s first “proper” ballpark, was opened near the present-day site of Garfield Square in 1868.

The 1880s saw the construction of two 15,000-capacity ballparks in San Francisco — Recreation Park a.k.a. Central Park, which was located at Eighth and Market near City Hall, and the HaightStreet Recreation Park at Stanyan and Waller streets in the Haight.

Early California League teams like the San Francisco Californias, the San Francisco Haverlys and the San Francisco Pioneers regularly played at these parks, as did their East Bay rivals the Oakland Colonels. Both parks were also the scene of exhibition games featuring major league teams from New York, Boston and Chicago. The Haight-Street ballpark closed in 1895, but Recreation/Central Park continued on as the city’s main baseball venue until it was destroyed by the 1906 earthquake.

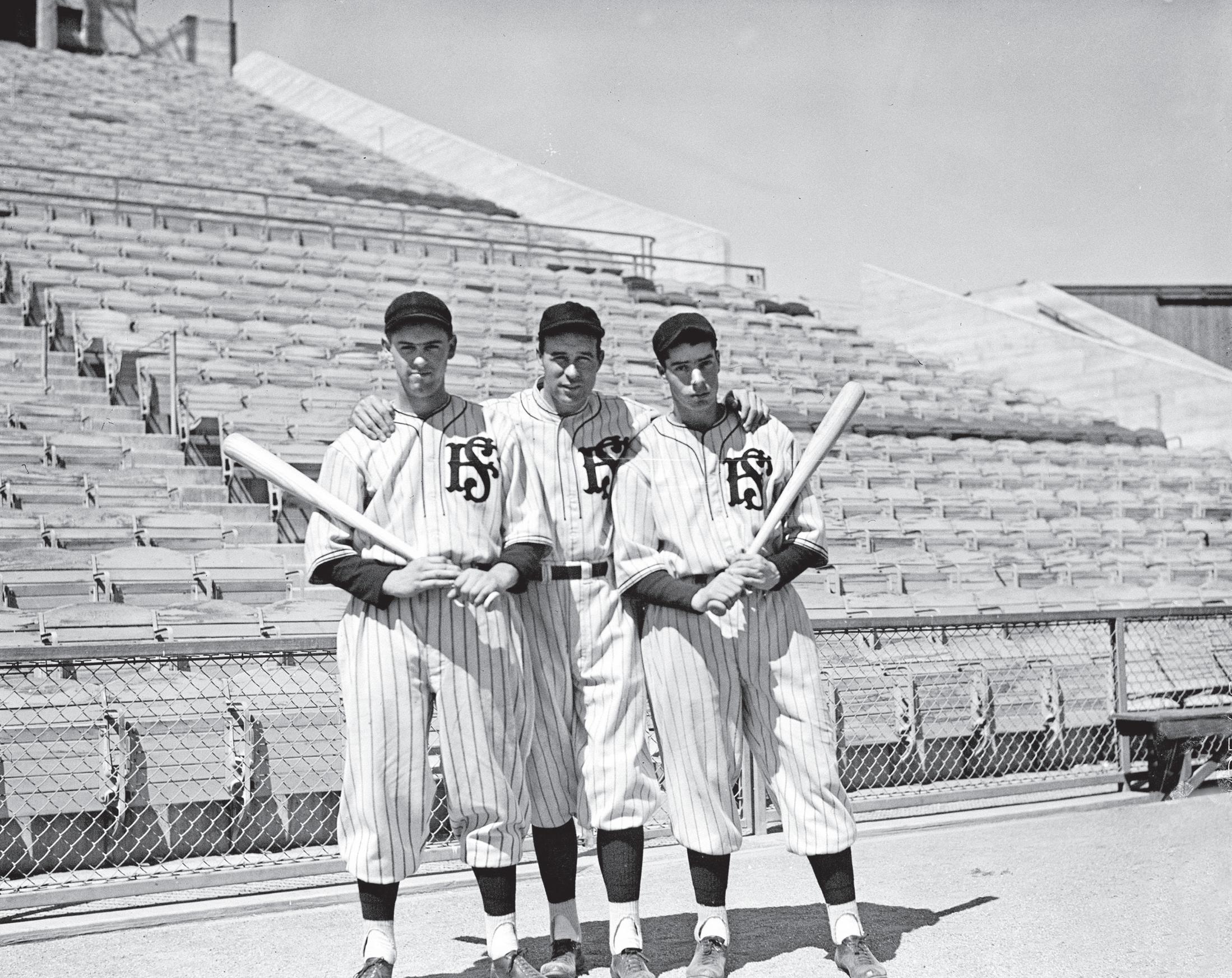

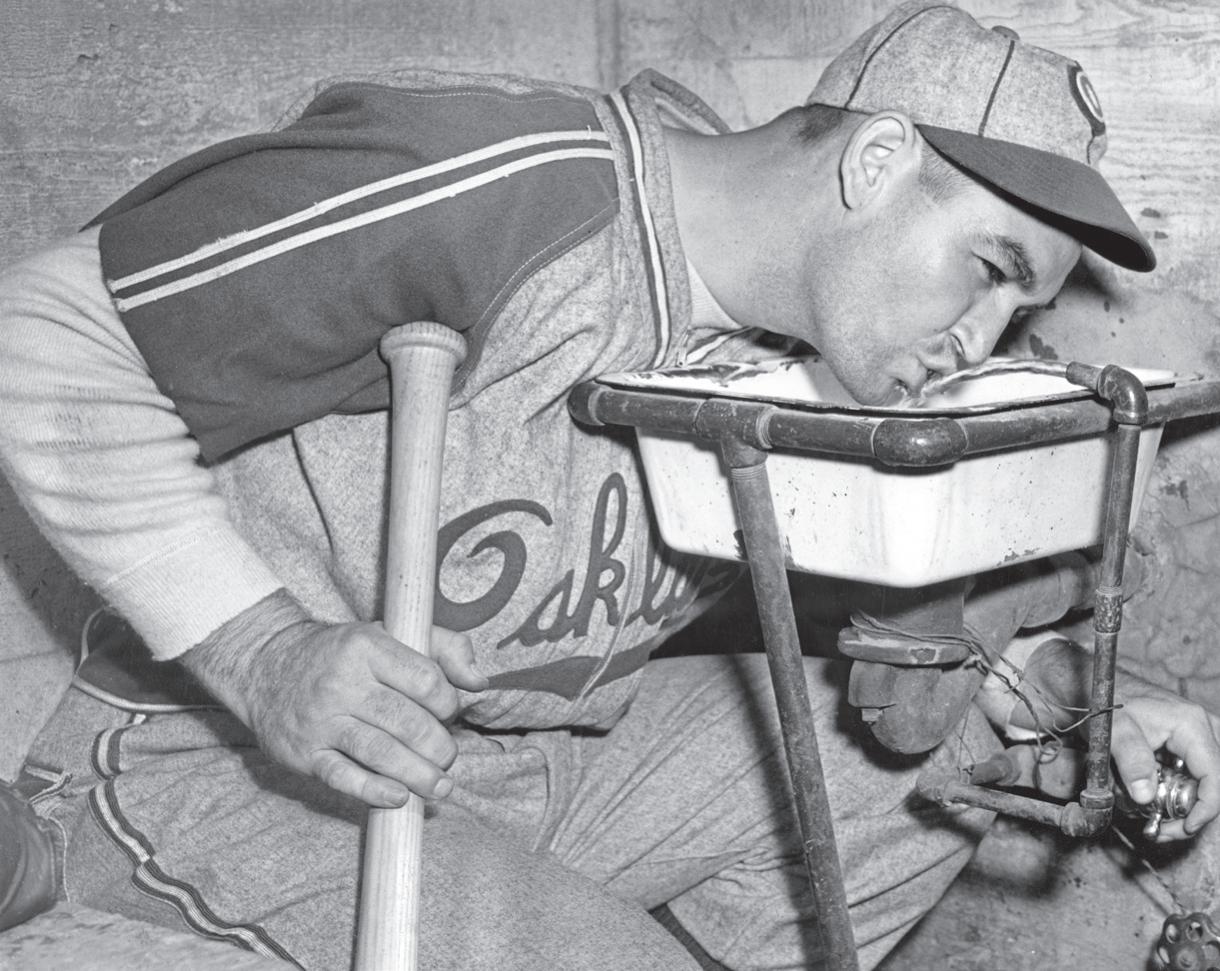

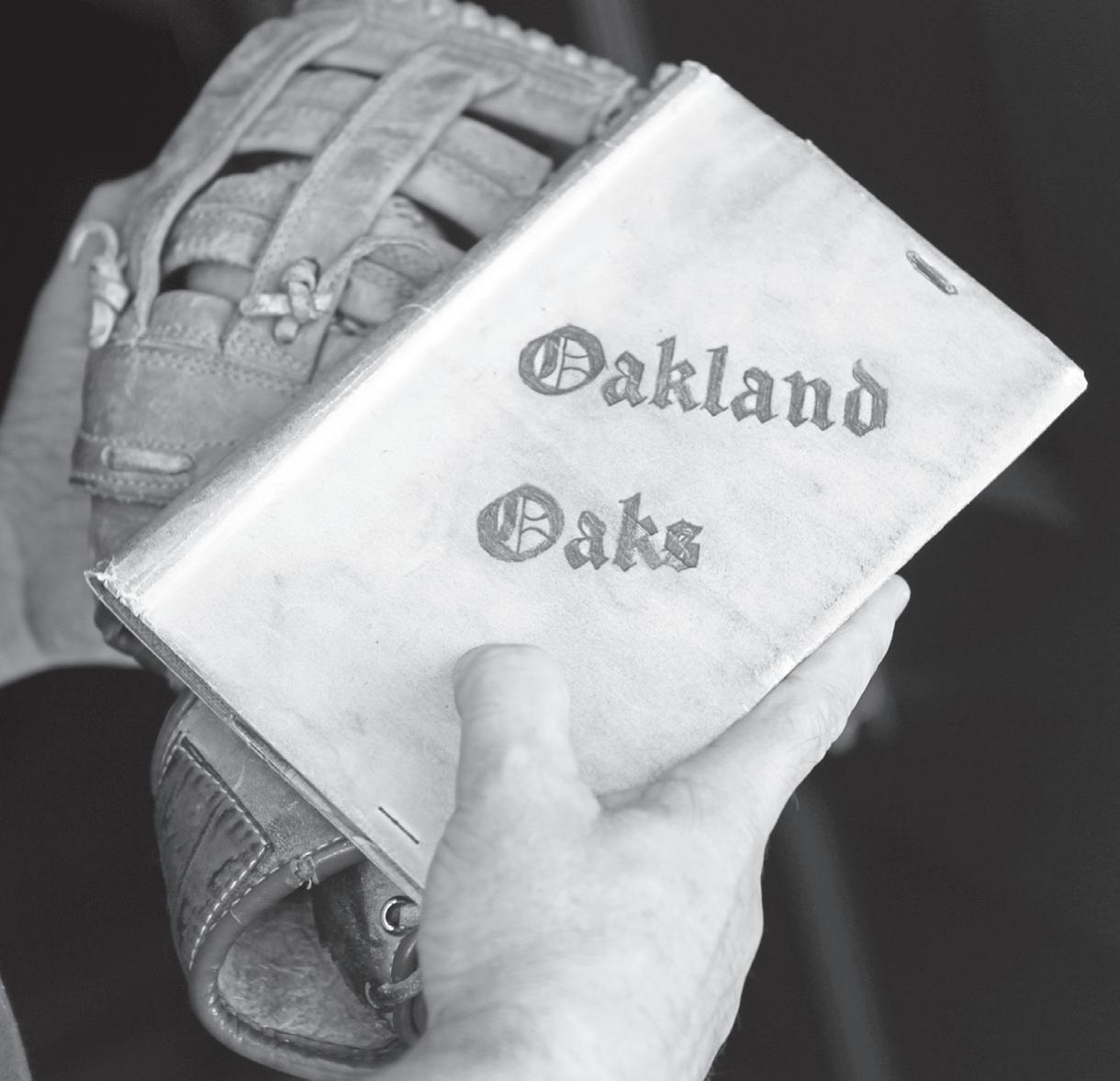

In 1903, the Pacific Coast League was born, and its two Bay Area charter franchises — the San Francisco Seals and the Oakland Oaks — delighted countless local baseball fans over the next 50plus years. The Seals won 14 PCL titles during their existence, and the Oaks five, and both teams contributed a wealth of great players to the majors, including Hall of Famers Earl Averill, Joe DiMaggio, Ferris Fain, Lefty Gomez, Billy Herman, Ernie Lombardi, Mel Ott, Albie Pearson and Paul Waner. In fact, the consistently high level of play exhibited throughout the PCL earned it a reputation as

“the third major league,” though its attempts to o cially join the American and National leagues were soundly rebu ed.

The Oaks played the majority of their home games in Emeryville, first at Freeman’s Park at 59th Street and San Pablo Avenue, and then from 1913 to 1955 at the 11,000-capacity Oaks Park, located at 45th and San Pablo. In 1946, the intimate park was also briefly home to the Oakland Larks of the West Coast Baseball Association, a short-lived all-Black league. The

Larks, who finished first during the WCBA’s lone season, featured two notable players on their pitching sta — Sam “Toothpick” Jones, who would go on to win 102 games in the majors, and Lionel “Lefty” Wilson, who would go on to become Oakland’s first Black mayor.

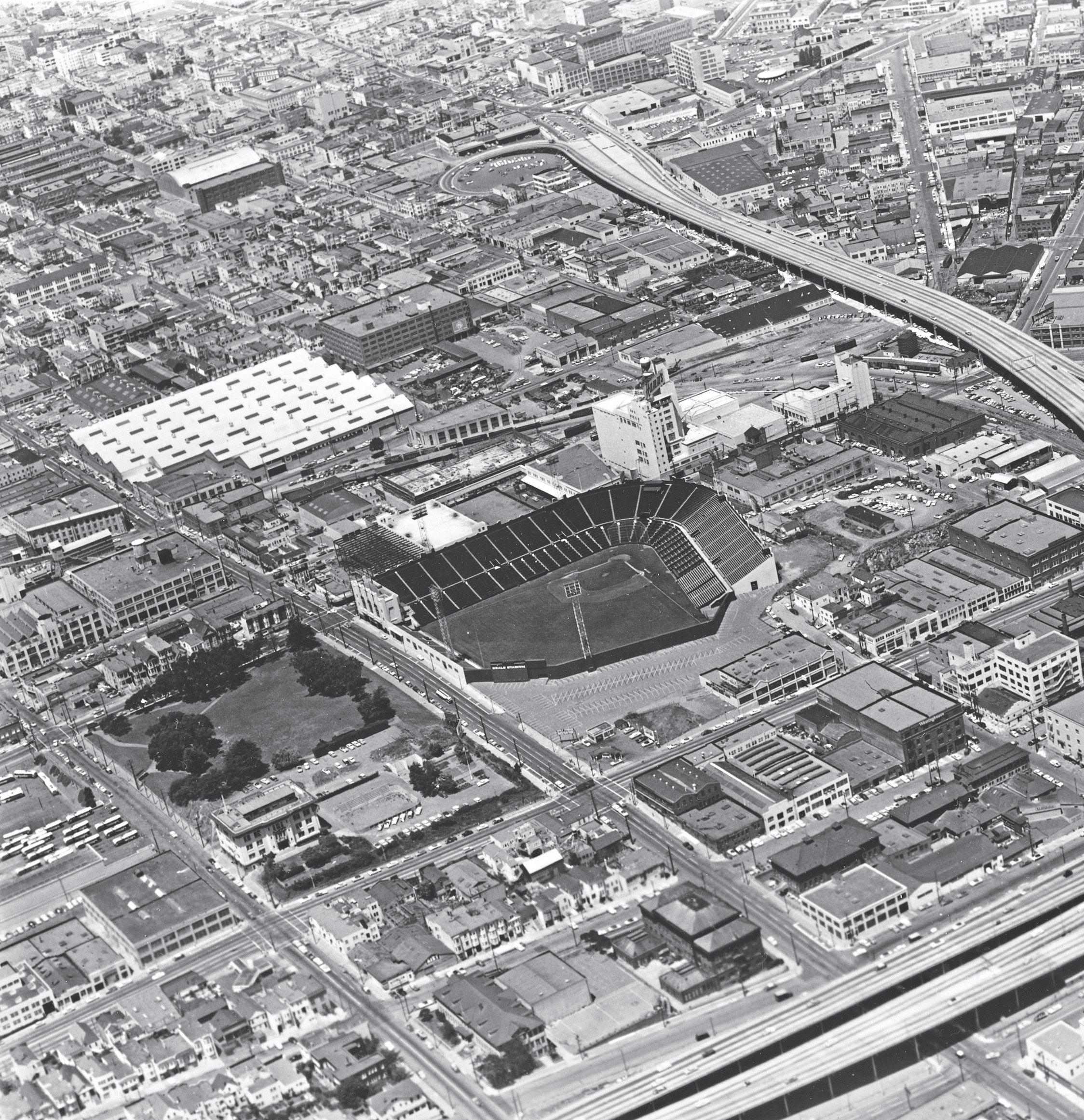

The Seals, arguably the PCL’s premier franchise, also boasted what many considered to be the league’s premier ballpark. From 1931 to 1957, they played their home games at Seals Stadium, an elegant and intimate venue located at the corner of 16th and Bryant, not far from the site of that initial Eagles-Red Rovers contest in 1860. The concrete-and-steel Art Deco structure o ered seating for 16,000 fans, clear sightlines, a gorgeous view of the Mission district from the grandstand and three spacious clubhouses — one for the Seals, one for opponents and one for the Mission Reds, the Seals’ far-less-popular local rivals, who only lasted from 1926 to 1937. (The park was also home in 1946 to the WCBA’s San Francisco Sea Lions.)

Another unique feature of Seals Stadium was that its neighbors included the Lagendorf Bakery and the Rainier (later Hamm’s) Brewery, which meant that day games were often fragrant with the comforting scents of freshbaked bread and warm beer.

“When we played in the afternoons at Seals Stadium, these big beer suds would come floating over the field,” Portland Beavers outfielder Nino Bongiovanni told PCL historian Dick Dobbins in the latter’s wonderful book, “The Grand Minor League: An Oral History of the Old Pacific Coast

League.” “It made you want to have a beer.”

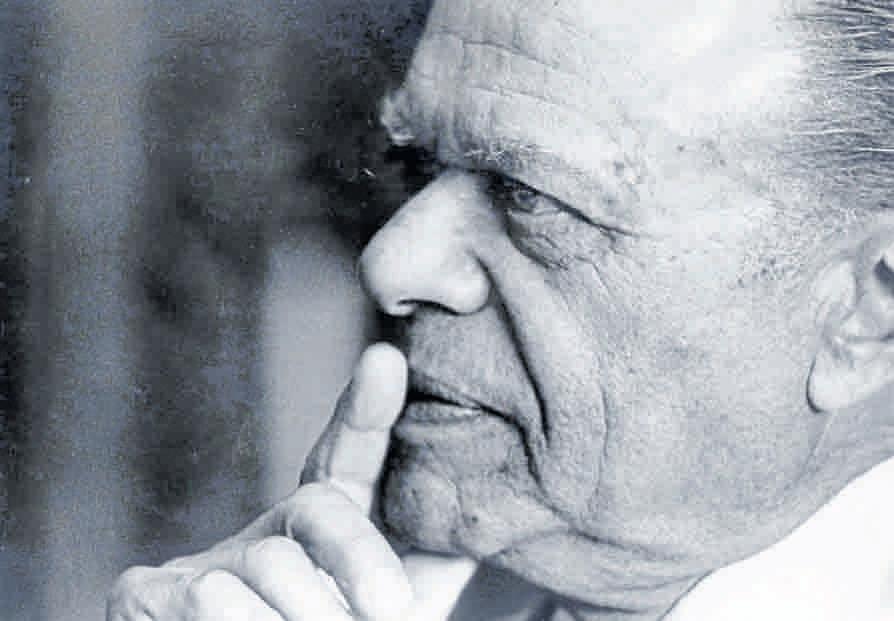

For Lefty O’Doul, this was most certainly a feature and not a bug. A legendary character who liked to dress entirely in green o the field — and even drove a green Cadillac — the San Francisco native won the PCL’s Most Valuable Player award in 1927 (when he hit .378 with 33 homers for the Seals) before going on to win two batting crowns in the National League. He returned in 1936 to manage the Seals and bagged five PCL pennants during his 15-year stint as skipper. A goodwill ambassador to Japan before and after World War II, O’Doul was so vital to the growth of baseball in that country that he was enshrined in the Japanese Baseball Hall of Fame, the only American to achieve such an honor.

In 1958, after the arrival of the Giants (who played their first two seasons at Seals Stadium) spelled the end of the PCL in the Bay Area, O’Doul opened up his own restaurant and cocktail lounge in San Francisco’s Union Square neighborhood, where he was a regular, green-suited presence until his death in 1969. O’Doul was buried in Colma’s Cypress Lawn Memorial Park. His headstone, which is emblazoned with a baseball and regulation-sized bat, bears the epitaph, “He was here at a good time and had a good time while he was here.”

If I had a ticket for that aforementioned time machine, I’d set the controls for Seals Stadium, somewhere during Lefty O’Doul’s managerial tenure. Though it would be fun to watch a 20-year-old Joe DiMaggio in 1935— his final year with the Seals, when he hit .398 with 34 home runs — it wouldn’t have to even be a specific game or season. I just want to sit in that grandstand, watch some classic PCL action, soak up the San Francisco sunshine, sni the beery, bready aromas as they float by and listen to O’Doul as he hilariously harangues the umpires. That sure sounds like a good time to me.

STAFF ARCHIVES

Left: The empty Seals Stadium in San Francisco is shown in this aerial view on June 13, 1957. AP PHOTO