7 minute read

Where have you gone, Rickey Henderson?

BY JON BECKER

Major League Baseball may never see a man stealing bases quite like Rickey Henderson or Duane Kuiper ever again.

Now that you’ve probably reread the previous sentence, we’ll explain their unlikely connection on the basepaths in a moment.

First, it’s important to recognize baseball’s fascination with home runs has done more than just lead to an obsession with exit velocity and launch angles. It’s essentially causing the sport to power down on another appealing aspect of the game: the stolen base.

For fans who enjoy the art of the steal, the 2021 season brought more disappointment than ever. For the first time since the MLB began counting stolen bases in 1886, its yearly number of steals has declined for four consecutive years. Worse yet, last year’s total stolen bases were the fewest in a full major league season in nearly 50 years.

It’s no secret why the stolen base is steadily disappearing from the game — the numbers no longer add up, say the analytics guys. A risk-averse mentality has taken over the thought process of baseball’s decision-makers. From the front o ce to the dugout, the message is clear: The risk of getting thrown out on the bases really isn’t worth it. After all, one more out means one less chance to hit a home run.

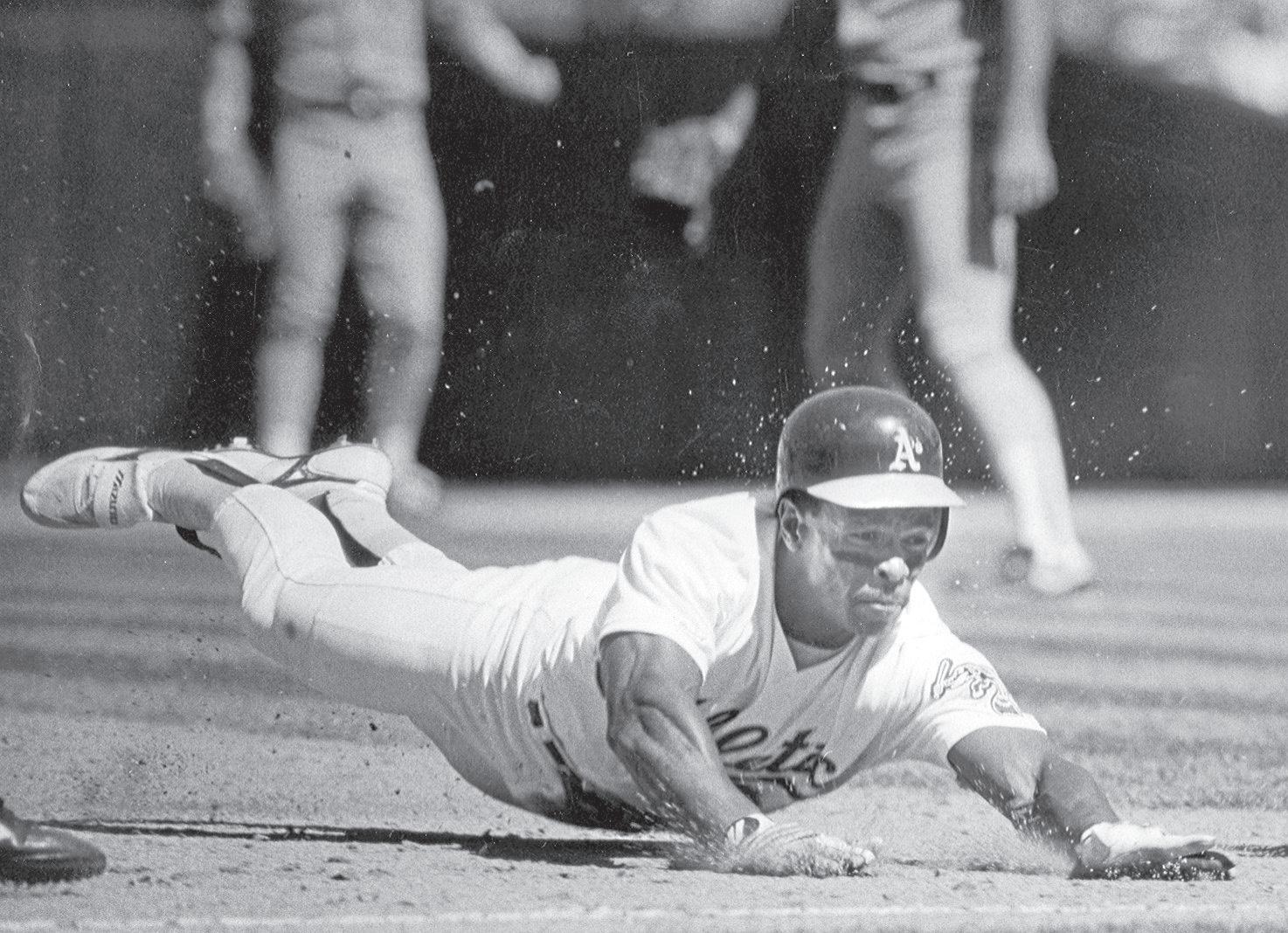

Left: Rickey Henderson stole a modern day record 130 bases for the Oakland A’s in 1982. Last season, the Kansas City Royals led all Major League teams with 124 stolen bases. MLB hasn’t had a player steal 70 bases in a season since Boston’s Jacoby Ellsbury in 2009.

TOM DUNCAN/ STAFF ARCHIVES

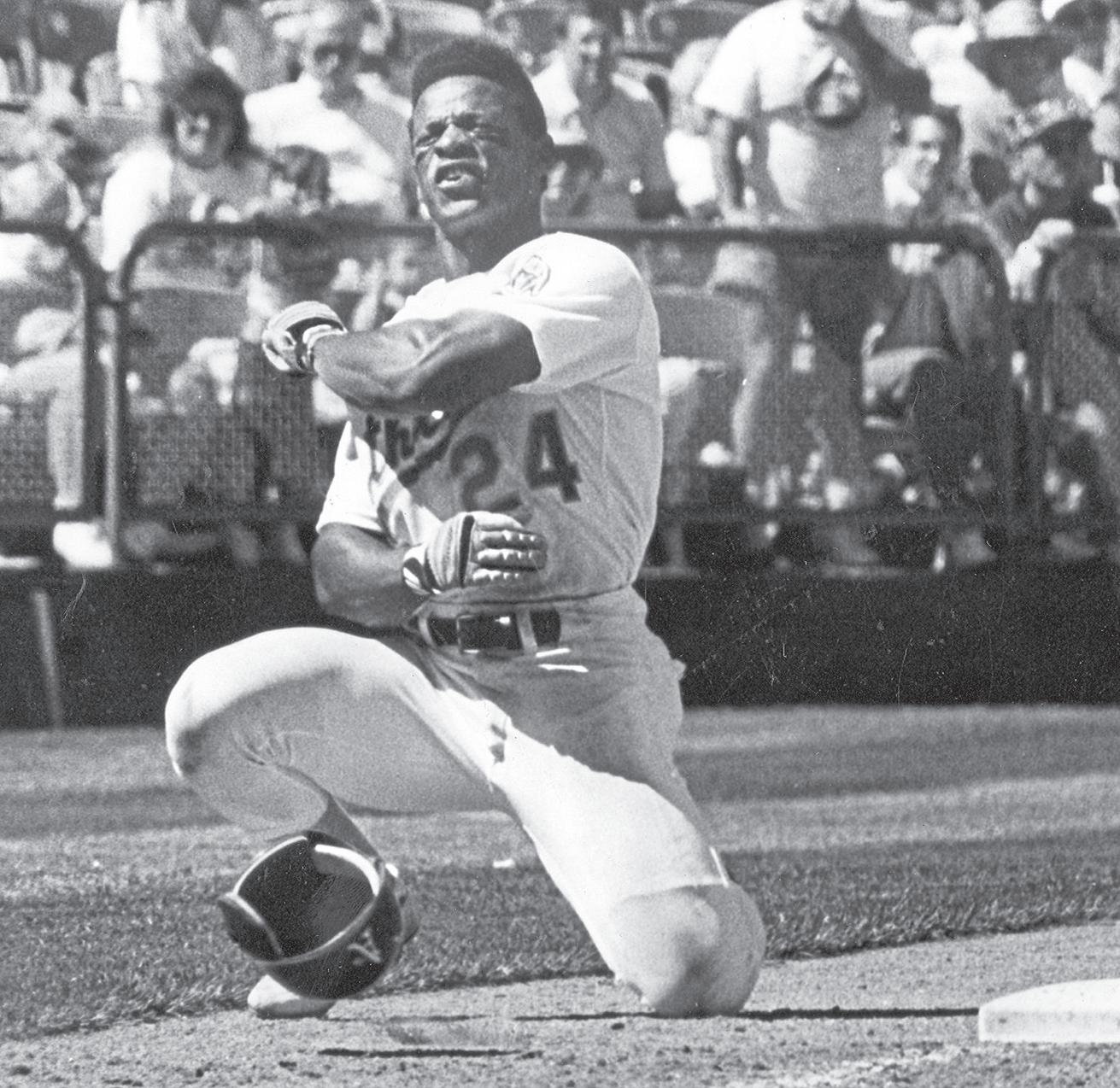

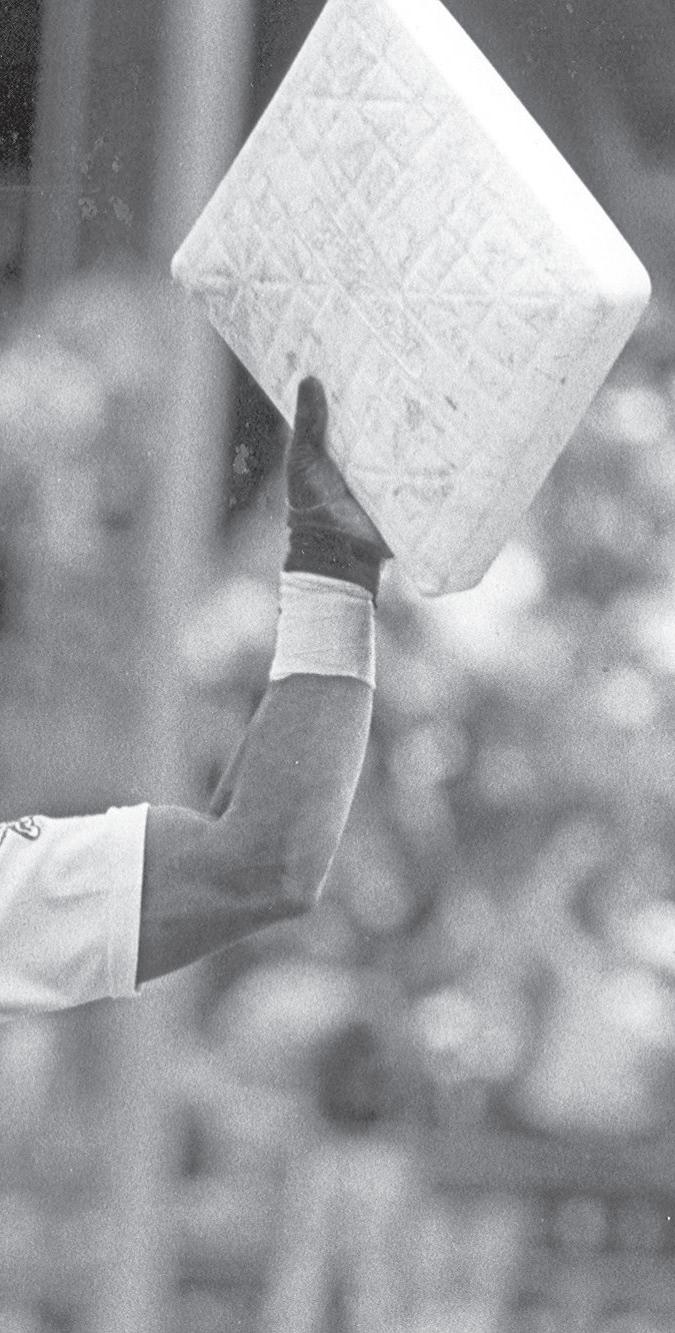

Rickey Henderson holds the MLB career and single-season records for stolen bases but also holds the record for being caught. Here, he tosses his helmet after being picked o by Texas’ Kenny Rogers during a 1990 game.

ROY H. WILLIAMS/ STAFF ARCHIVES

Henderson spent most of his career with the A’s, and it was Oakland’s executive vice president, Billy Beane, who played a significant role in putting stop signs up across the majors.

“It’s not exactly revolutionary,” Beane once told ESPN. “If you’re last in the league in steals, you’re also last in the league in caught stealing, too, and you’re saving yourself a lot of outs. If you break it down, which is more valuable: a potential out or one more base?”

If this kind of caution had been in play in the 1980s and ’90s, life would have been much easier for opponents having to deal with Henderson, baseball’s most accomplished base thief ever. The Oakland-born Hall of Famer terrorized teams on his way to a Major League record of 1,406 career steals, including a record-breaking 130 bags with the A’s in 1982.

At the risk of bombarding you with more numbers, consider that in Rickey’s heyday in ’82, there were 3,379 home runs hit and 3,176 bases stolen MLB-wide. Last season, there were nearly three times as many homers (5,944) as there were stolen bases (2,213).

Henderson acknowledges he played a di erent game in a di erent era. He told Sportsnet there’s no way he could come close to duplicating his stolen base numbers if he played today — and not just because he’s now 63 years old.

“The kids today, they say ‘How’d you do it?’ And I say, I couldn’t do it the way they’re doing it now because they’re making your call, they’re making the decision before you’re making decisions … They’re too worried about giving up an out,” Henderson said.

In previous eras, even the threat of a stolen base was considered a weapon.

“I would have much rather faced (Mark) McGwire or (Jose) Canseco in a clutch moment than I would to play defense with Rickey Henderson on base — 100 percent,” Braves Hall of Fame third baseman Chipper Jones told Athlon Sports in 2019. “Those guys had holes. They could be pitched to. Rickey could dominate a game. I felt the same way about Jose Reyes in his heyday. When he got on base, he wreaked havoc, and it was disconcerting to have him on base.”

Considering baseball’s current trends, it seems unfathomable that either of Henderson’s records will be broken anytime soon. To wit, the Kansas City Royals led the majors in stolen bases last season with fewer steals than Rickey had by himself in ’82. The Royals’ 124 steals were not only six fewer than Rickey’s total in ‘82, they represented the lowest MLB-leading total by a team in a full season since 1963.

Thievery, though, can have its conse- quences. Rickey’s record-breaking run on the bases contained a fair share of missteps. He still holds the MLB career record with 335 times caught stealing during his 25 seasons. He was thrown out 42 times in 1982, which remains a single-season record.

Hall of Famer Rod Carew, who played first base for the Angels during Henderson’s reign of terror on the bases, always said there was an easy way to figure out whenever Rickey was about to steal — not that it helped a lot. You just had to keep your ears open for the man speaking in the third person.

“He’d say, ‘Rickey’s gotta go,’” and he’d be o , Carew said.

Henderson’s success rate of 75 percent in ’82 wouldn’t quite measure up in today’s game. A general consensus of teams nowadays is that only something closer to an 80 percent steal rate is acceptable.

Using that as a gauge, there’s little chance a base stealer such as Kuiper, the beloved Gi- ants announcer and former second baseman, would be given a green light to attempt many steals now.

Kuiper struggled to steal a base well before teams began studying pitchers’ pitch sequencing or delivery time to the plate or a catcher’s “pop time” to catch and throw to a base. Kuiper stole 52 bases during his 12-year career but was thrown out 71 times — nearly 60 percent of the times he tried to steal.

His 42.3 percent success rate on stolen base attempts is the second-worst percentage in Major

League history for players who attempted at least 100 steals. Since his former Cleveland teammate, Buddy Bell, holds the all-time record for lowest stolen base percentage (41 percent) among qualifiers, maybe Cleveland’s managers are the ones to shoulder the blame for turning Kuiper and Bell loose so often.

Given the correlation between stolen bases and home runs, perhaps there’s a bit of irony that Kuiper’s lone home run in 3,379 career at-bats came on the same night in 1977, when Lou Brock passed Ty

Duane Kuiper, right, here with longtime broadcasting partner Mike Krukow last season, stole 52 bases in his career, but was thrown out 71 times, among the lowest success rates in modern baseball.

MONDON/ STAFF ARCHIVES

Cobb to (temporarily) become the all-time stolen base leader.

While homering can be challenging for some, A’s shortstop Elvis Andrus said last season he couldn’t understand why it’s been so di cult for players to steal bases, even with today’s heightened obstacles.

“It’s not that hard. Stealing bases isn’t rocket science,” said Andrus, whose 317 career stolen bases were the most of any player in the majors last season.

Andrus’ beliefs were validated during the 2021 postseason, when base stealers enjoyed a record-setting time. Whether it was picking on slow pitchers, poor catching or just utilizing fast runners for a change, teams stole a combined 45 bases, good for the sixth most ever in a single postseason. And the 91.8 percent success rate — compared with the 75.7 percent rate in the regular season — was an all-time record for a single postseason.

The Giants and A’s weren’t the league’s busiest base stealers last season, but they were among the most successful at getting away with it.

The A’s 88 stolen bases were tied for seventh in the Majors, but their 81.5 percent success rate ranked fourth. Much of the credit goes to Starling Marte, who arrived in a midseason trade and did a tremendous Henderson impersonation, swiping 25 bases in 56 games. He was only caught twice. The Giants were 16th in the Majors in stolen bases (66) but were only caught 14 times and ranked third in success rate (82.5 percent).

Nonetheless, there’s no real expectation we’ll see a change in the game’s dynamics this season. More likely, we’ll continue to see the kind of modest stolen base numbers turned in last year, which were further illuminated by the Dodgers’ Trea Turner winning the National League title with just 32 steals. It was the fewest steals needed to win the N.L. crown since Willie Mays swiped 27 bags for the Giants in 1959. Henderson, by comparison, stole at least 32 bases in 20 of his first 22 MLB seasons, including in 2000 with the Mets and Mariners, when he was 41 years old.

Chicago White Sox manager Tony La Russa doesn’t need to be convinced there’s still room for smallball in today’s game. Whether it’s a well-timed stolen base or merely a productive out that moves a runner up a base, the Hall of Famer believes the little things can make a big di erence.

“I’ve seen guys get the leado man on base three or four times a game, never get him over, always trying to hit a two-run homer, then lose the game by a run,” La Russa said. “Then if a manager tries to play for a run, the metrics guys say, ‘Hey, the percentages are against that.’ But the percentages are the averages; that’s why I say the variability, the dynamics of what happens on an everyday basis, it’s actually easier to win now than ever.”

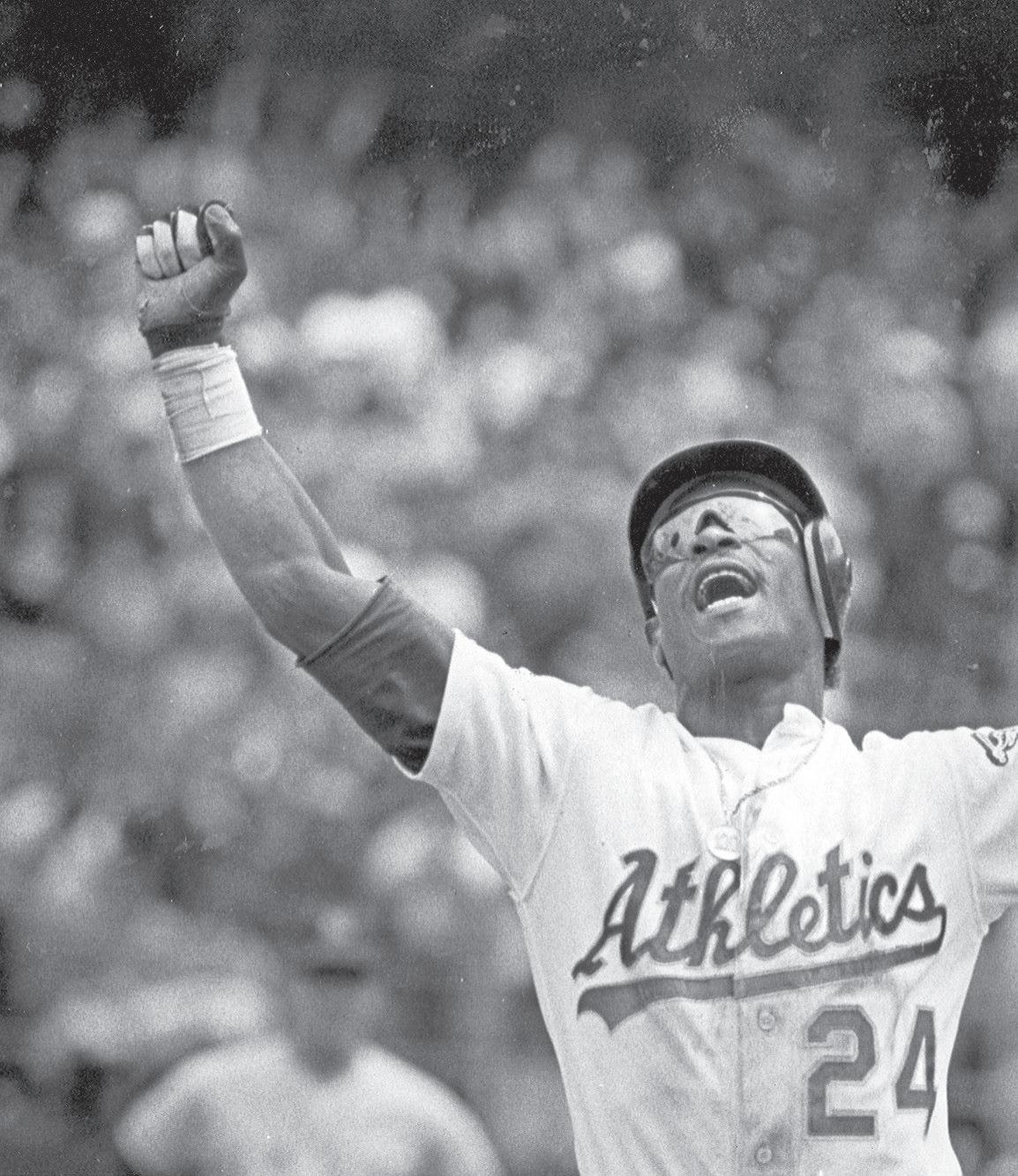

Left: Starling Marte provided the A’s a huge spark on the bases after he was acquired in a July trade, stealing 25 bases in 56 games and getting caught just twice. In all, he swiped a MLB-best 47 bases between the A’s and the Marlins.

Bottom: Austin Slater was a big reason the Giants ranked third in the Majors in stolen base percentage in 2021. Slater stole 15 bases and was thrown out just twice, and his 86.66 success rate led the National League.