5 minute read

A public eye on the private eye

UC Berkeley curator keeps tabs on a collection of California crime fiction

STORY BY CHUCK BARNEY

ILLUSTRATION BY HELENA PEREZ GARCIA

about to interrogate, er, interview, Randal Brandt, who has the lowdown on a big, valuable stash of mystery books at UC Berkeley. And it’s so tempting to roll up a stogie full of Bull Durham tobacco, break out a fierce scowl and hit him with my best Sam Spade/ Humphrey Bogart impersonation.

“OK, wise guy, you look like you swallowed the canary. Now, don’t be a sap. Come clean and give me the straight dope!”

Brandt, to his credit, is willing to play along.

“I can get a big light and shine it in my face if you

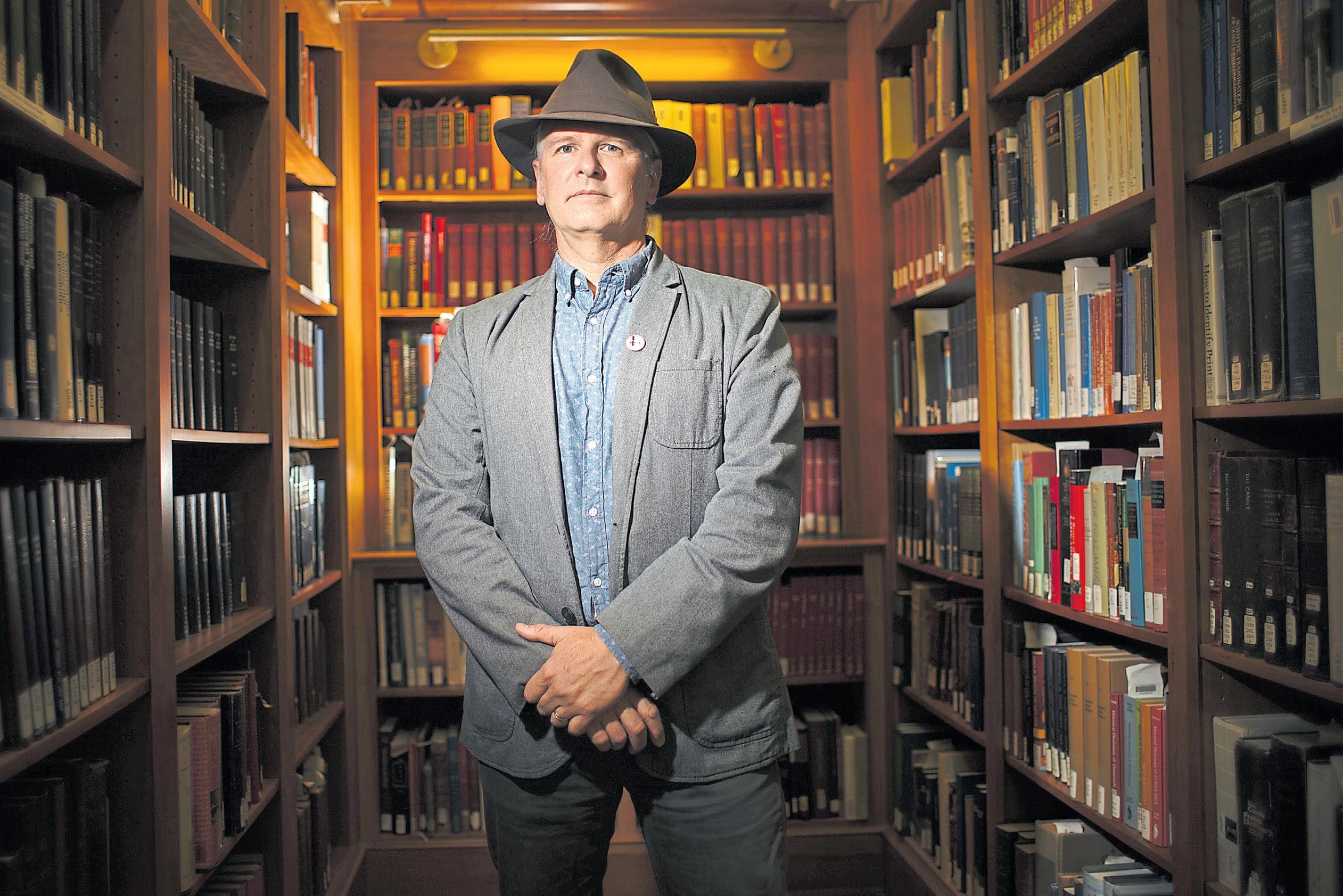

Randal Brandt is the curator of the California Detective Fiction Collection at UC Berkeley’s Bancroft Library.

ANDA CHU/STAFF

want,” he says.

Hmm. This guy ain’t no chump. He knows the game. And as curator of the Bancroft Library’s massive California Detective Fiction Collection, he has spent endless figurative hours hanging out in dark shadows while rubbing elbows with ruthless gangsters, ex-cons, tough dames, skid rogues and shady button men.

So maybe I’ll hold off on the chin music. Instead, we can just talk turkey. Friendly, like.

As for this California Detective Fiction Collection? It’s about 4,000 volumes and growing. And it’s a labor of love for Brandt, whose main duties are heading up Bancroft’s cataloguing department.

“I collect mysteries in the broadest sense,” he says “There are a lot of different sub-genres. You’ve got the hard-boiled. You’ve got private eyes. Police procedurals. The cozies — amateur detective type stuff. I collect all of that. If it’s California, it doesn’t matter.”

Yes, the Golden State is key. To qualify for the collection, tomes must either be set in California (i.e., Raymond Chandler’s “The Big Sleep”) or written by Californians who do their literary gumshoeing beyond state lines. Bay Area authors such as Cara Black (France) and Laurie R. King (England) fall into that category.

Bancroft’s literary loot is full of marvelous gems, including two first editions of “The Maltese Falcon,” Dashiell Hammett’s Sam Spade detective novel. The moody 1930 classic, set in San Francisco, inspired the Bogart film, which many movie buffs regard as the first real example of film noir.

What made Hammett and Spade such cool customers? They were “so new and fresh and different,” Brandt insists.

“Now, so many writers have been influenced by Hammett, and they’ve developed characters that have traits of Sam Spade,” he says. “But at the time, there wasn’t really anything like Sam Spade — at least not outside the pulp magazines. Earlier (literary) detectives were much more in the armchair detective mode. Nero Wolfe. Hercule Poirot. The gentleman armchair detective kind of thing. Hammett took crime out of the drawing room and put it in the streets. And the writing is so spectacular — so bare. The story just keeps moving.”

Other highlights: Bancroft was able to acquire, via purchase, a vast collection of Erle Stanley Gardner (of Perry Mason fame) first editions and was gifted with most of the works of Ross MacDonald, creator of the Lew Archer detective series.

More recently, an “incredible gift” came from Oakland mystery writer Mark Coggins, who forked over a complete set of Chandler and Hammett first editions.

Talk about a big score. Coggins, known for his August Riordan private eye novels, which are also in the Bancroft collection, had been acquiring the books since the early ‘90s. He viewed himself as “sort of a custodian.”

“We all pass on eventually, and I thought Bancroft was the best place for them to go. It’s a great fit,” he says.

Coggins, who has studied and written extensively about Raymond Chandler, believes it’s important to preserve examples of the genre for future researchers and/or publishers looking to produce new editions of certain works. He also thinks critics who regard the genre as a lesser art — unworthy of study — are “totally wrongheaded.”

“When done well, it’s every bit as good as what people consider to be literary fiction,” he says.

“Besides that, so many works of fiction contain elements of crime. Just look at ‘The Great Gatsby.’”

It’s no wonder then that Coggins — a proud Stanford grad — handed over his treasures to Cal.

“Stanford has not chosen to elevate crime fiction in the same way,” he says with a trace of disdain in his voice. “Berkeley has simply shown better judgment in their literary acquisitions.”

Of course, there is always more to acquire. High on Brandt’s want list are a few first editions of James M. Cain, the author of a number of classic and influential noir mystery novels, including “The Postman Always Rings Twice,” “Double Indemnity” and “Mildred Pierce.”

And then there’s Erle Stanley Gardner’s debut novel, “The Case of the Velvet Claws.”

“A first edition of that is going to have to come as a gift, because we’re never going to be able to afford to buy it,” Brandt says. “We’re talking, like, around $35,000. There aren’t that many out there.”

Whodunits and thrilling page-turners have intrigued Brandt since his childhood years in the small San Joaquin Valley town of Reedley. Growing up there, he didn’t have easy access to movie theaters, so he became a voracious reader. His mother introduced him to Agatha Christie, and he eventually fell hard for the James Bond spy novels of Ian Fleming.

“Going to see a movie was a pretty big deal, and we didn’t do it very often,” Brandt recalls. “I

These crime fiction thrillers are all included in the California Detective Fiction Collection at UC Berkeley's Bancroft Library in Berkeley.

ANDA CHU/STAFF

found out that there were these James Bond movies out there, and they looked pretty cool. I couldn’t see them, but I discovered that the library had a whole bunch of books about Bond. So that was the next best thing.”

Brandt attended college just up the road at Fresno State, where he majored in English. He went on to earn his master’s in library and information studies from UC Berkeley in 1990 and began working at Bancroft in 2001.

After wallowing for years in enticing mysteries, does Brandt have the itch to write one of his own? Not really.

“I do like to write,” he says. “But more about authors and their books.”

To that end, he has written a great deal about the late David Dodge, his favorite author. A Berkeley native, Dodge penned “To Catch a Thief,” a 1952 romantic thriller that inspired the Alfred Hitchcock film of the same name. Brandt became a huge fan years ago while reading Dodge’s “The Long Escape” during a vacation in Mexico.

“I would love to write a fulllength biography about him,” says Brandt, who created a website devoted to Dodge, www.daviddodge.com.

So why are we so drawn to mysteries anyway? Brandt believes it’s all about escapism — and the chance to play backseat detective.

“I think there’s something very satisfying about the solving of crime,” he says. “When you read a book, or watch something on TV, it’s just satisfying and enjoyable to follow along and pick up on clues. People also love puzzles — and being surprised by fun twists.”

Spoken like a man who has spent many an hour cracking wise, talking tough and strolling the literary mean streets.