6 minute read

Out and about

BY TOR HAUGAN

Magic of theater

If you’d like to take your kids to the theater but you know they’re not quite ready for the “Book of Mormon,” check out Fantasy Forum at the Lesher Center for the Arts in Walnut Creek. There, young thespians can take in interactive shows in a kid-friendly space. This past season featured “Wizard of Oz,” among other offerings. Fun fact: Jack Haley, the Tin Man from the 1939 film, reportedly attended a production of “Wizard of Oz” in 1978.

The Lesher Center for the Arts is at 1601 Civic Drive. For details, go to http://fantasyforum.org

Let’s bounce

If your kids are bouncing off the walls, take them to a place where it’s OK even encouraged for them to jump to their hearts’ content. San Francisco’s House of Air, one of several trampoline parks in the Bay Area, offers open jump time, as well as classes and programs for kids as young as 2 It also can host parties and other events.

House of Air is at 926 Old Mason St. in San Francisco. For details and tickets, go to www.houseofair.com.

Their natural habitat

Want to take the tykes to a place where they can play and learn? Check out Habitot Children’s Museum, in downtown Berkeley Toddlers will love all of the hands-on fun crammed into a relatively small space. Kids can explore the Wiggle Wall, a vertical maze of tunnels; check off items on their shopping list at the scaled-down pretend grocery store; and explore the Waterworks area, where they’ll discover the unique properties of the most abundant liquid on Earth.

Habitot Children’s Museum is at 2065 Kittredge St. For details, call 510-647-1111

Aday on the farm

Do you want to experience farm life without doing heavy labor? At Deer Hollow Farm in Rancho San Antonio Open Space Preserve, visitors can take selfguided tours of the 10-acre working farm, and young ones will enjoy looking at the livestock. On mornings of the third Saturday of the month, the Deer Hollow Farm Nature Center, in the old apple shed, is open to the public, and a Friend of Deer Hollow Farm docent is on hand to answer questions.

Deer Hollow Farm is at 22500 Cristo Rey Drive. For details, call 650-903-6430.

STORY BY JON WILNER

PHOTOGRAPHS BY JIM GENSHEIMER

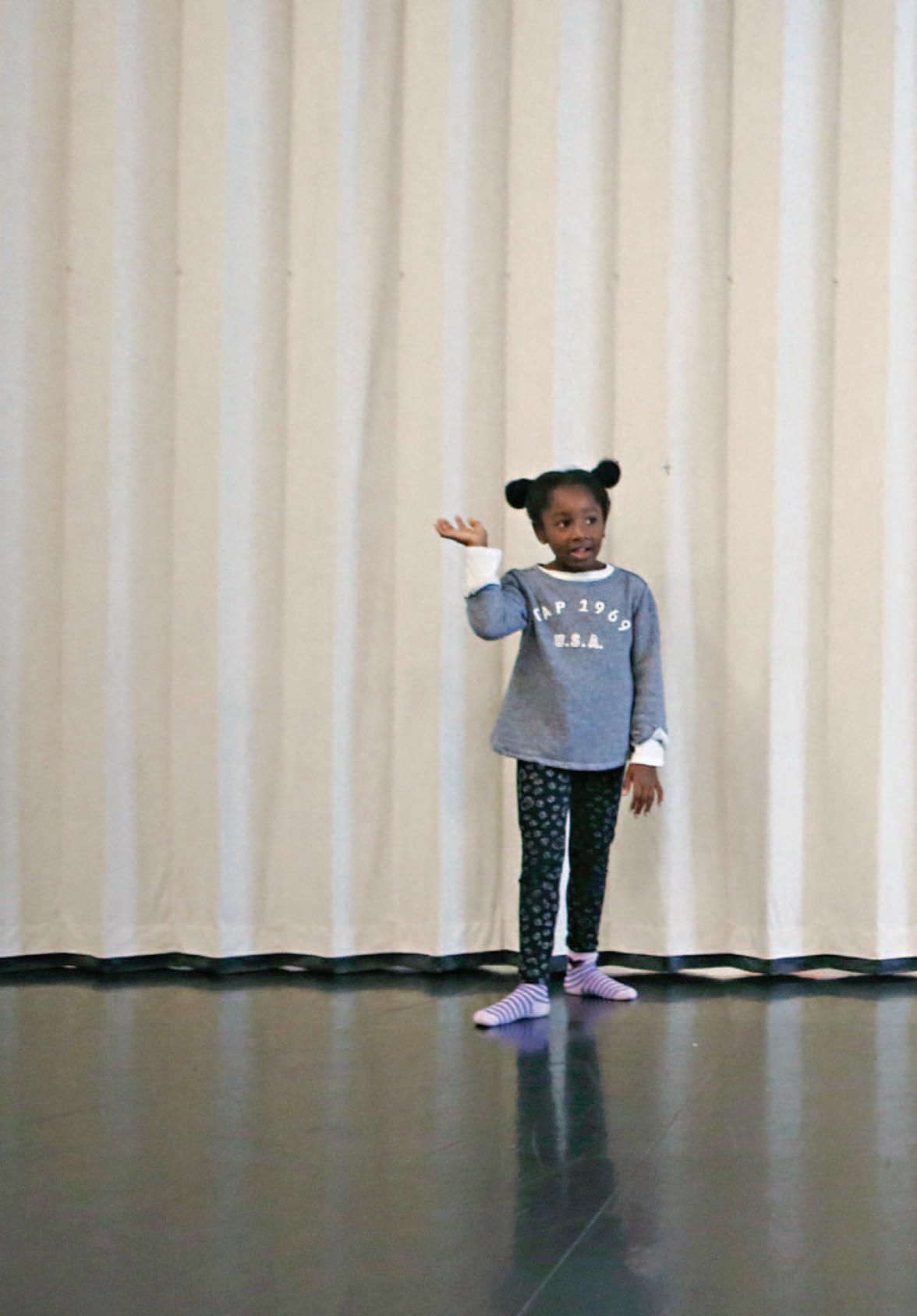

Bronwyn Brantley enjoys running track almost as much as she enjoys swimming Swimming is the best, of course, aside from chess There’s nothing better than chess well, except ballet. Ballet beats chess and everything else in Bronwyn’s busy life.

Just a few weeks ago, in fact, the 7-year-old went for her annual checkup. The pediatrician asked about her activities Bronwyn mentioned ballet.

“Tell me about it,” he said. She had no intention of telling him about it.

“Let me show you,” she said. With that, the Oakland native unleashed her best Misty Copeland impression — smack in the middle of the tiny exam room.

“She’s eager to show what she can do,” says Bronwyn’s mother, Helena. “She can see her own progress, and it seems to have emboldened her”

Bronwyn isn’t alone. She’s like millions of other elementary school children for whom activities are an essential part of their daily lives.

Is this thirst for action — through sports or music, art or dance — an instinctive desire to carve out an identity separate from those of their parents and siblings?

Is the explanation even simpler, rooted in nothing more than the urge to have fun?

From an evolutionary standpoint, taking part in sports and activities can be traced back millions of years, when socializing became necessary for early human survival.

Bronwyn Brantley, 7, pictured here and on the opening page, dances with her sister, Avery, 5, at Oakland School for the Arts. “She’s eager to show what she can do,” says Bronwyn’s mother, Helena.

But what does it mean in the age of iPhones and Xboxes?

Unfortunately, the research is a tad thin for ages 6 to 11, or what experts call middle childhood. This time lacks the breathtaking developmental leaps that dominate infancy and toddlerhood and is devoid of the drama that comes with adolescence. For every five books on infants, toddlers and teenagers, there is one on middle childhood.

“It’s the mellow period,” says San Jose State professor Maureen Smith, who specializes in child and adolescent development. “It’s an incremental adding of skills.”

MIDDLE CHILDHOOD ALSO IS the age when social comparison takes root. Toddlers are the center of their own world, with attributes painted in broad strokes: They are the fastest, the smartest, the strongest.

The transition into grade school brings a cognitive advance that allows for perspective: Joey learns he isn’t as fast as David; Emily discovers she’s smarter than Nicole but not as smart as Caitlyn.

Confidence, or lack thereof, is sure to follow

“They begin to compare their ideal self to their actual self,” says Emily Slusser, who has a doctorate in psychology and teaches at San Jose State “That can lead to good self-esteem and hard work, or to a feeling of helplessness.”

The development is best expressed by what experts call the theory of mind, which explores how children in elementary school become capable of differentiation: They’re able to grasp that other kids think, feel and act differently than they do

“The theory sets the roots for empathy and moral reasoning,” Slusser says. “That opens you up to other experiences, and you’re able to engage in more coopera- tive play — like sports.”

For a long time, experts believed self-esteem was the chief building block for success. Turns out, it’s the other way around: Success creates self-esteem, as the Gravink family of San Jose has come to realize

ANSLEY GRAVNIK, 10, HAD A knack for “hanging on stuff” as a young child, according to her father, Eric. One day in second grade, she came home from school able to do cartwheels She enrolled in a gymnastics class, and within six months was asked to join the acrobatic team. She now spends 12 to 14 hours a week at the gym and travels to competitions across the country.

Alex, 9, her sister, wasn’t as natural in the gym, but she was exposed to hockey at a Sharks Ice event for girls and took an immediate liking Now Alex plays for the Junior Sharks and during the season spends up to five hours per week on the ice. When possible, she also helps coach.

“Unstructured free time — daydreaming is how we find out identity. You stare at the cloud and think, ‘What do I want to be?’” San Jose State professor Maureen Smith says.

“We don’t compare one to the other Each has her own thing, and they’re in completely different sports,” Eric says. “The only rule we have for any activity is that if you sign up, you have to stick it out to the end of your commitment.”

The sisters’ confidence has skyrocketed since they became immersed in their respective sports. Ansley set a school record for situps and has been known to take on the boys in pushup contests. Alex wants to be the first female player in the NHL

“She’s recognized her progress,” Eric says, “and it’s motivated her”

Helena and Todd Brantley have noticed a similar trajectory with Bronwyn. One recent night at dinner, she noticed — and corrected her mother’s posture.

“In ballet,” she told her parents, “we learned that you have to sit up.”

In the year since Bronwyn transferred to a smaller, more structured class at the Oakland Ballet Company, she has felt more comfortable with her body and more determined not only with ballet but with everything in her life. “She wants to get it right,” Helena says.

This spring, the Brantleys cut back on Bronwyn’s activities and began scheduling more one-onone play dates. The concerns about overcommitting her were justified: Too much too often is one of the pitfalls when children begin to take an interest in sports and activities

They can’t self-regulate, so it’s up to the parents.

“Overscheduled kids lose the value of free play, whether it’s playing with Barbies or climbing a tree,” says Smith, the San Jose

State professor. “Unstructured free time — daydreaming is how we find out identity You stare at the cloud and think, ‘What do I want to be?’ ”

Another issue around sports and activities during elementary school can carry significant longterm consequences, and it runs counter to the parental instinct to protect: Performance is so closely monitored that children often aren’t allowed to fail.

“Failure is actually good for kids,” Smith says. “It builds resilience and an ability to cope: I can’t play basketball, but I can swim fast.

“We spent decades insulating our kids from failure, and the result is that we have 18-year-olds who crumple [at the first sign of adversity]. You don’t have to be good at everything ”

But it sure is fun trying