13 minute read

Frequency of Binge Watching and its Emotional Impact

from Scientia 2020

Katie Soudek, Shawn J. Latendresse, Ph.D.

Advertisement

Abstract

This study examined whether there was an association between participants’ frequency of binge watching and the emotions they associate with it. An online survey was administered to 66 college students and assessed emotions commonly associated with binge watching, such as loss of control, dependency, and positive emotions. A correlation analysis and three simple regression analyses were conducted on the data. There was a significant association between frequency and all three subcategories of the questionnaire, with negative emotions having a higher association than positive emotions. These results suggest that higher frequencies of binge watching have predominantly negative effects on viewers, and implications for future research are discussed.

Introduction

There are many activities available on the internet, and the amount of content accessible to users grows every day. Watching video content is the fourth most prominent activity that Americans engage in, following only email, text/instant messaging, and social networking (National Telecommunications and Information Administration, 2017). TV shows have doubled in number in the last seven years with 487 shows premiering in America in 2017 (Shaw, 2018). Historically, TV watching was on a schedule dictated by the network that premiered the content. New platforms such as Netflix and Hulu, however, began releasing entire seasons of TV shows at one time to allow viewers to decide their own viewing schedule, encouraging a new viewing method called binge watching, which allows consumers to watch concurrent episodes without interruption (Jenner, 2016). Netflix (2013) defines binge watching as viewing two to six episodes of a TV show in one sitting. For this study, watching the appropriate amount of episodes (as mentioned in Netflix’s definition) in a single sitting qualifies as a binge, no matter what device or content provider the subjects use.

Binging video content is an individualized activity, and it is difficult to determine the point at which TV watching becomes problematic (Jenner, 2017). In some cases, binging can have positive effects on viewers. One study researched effects of uplifting content on viewers’ emotions and overall outlook on life, finding that viewing uplifting content more often than others caused viewers to be more benevolent in their everyday lives (Neubaum, Kramer, & Alt, 2019). Also, Rubenking and Campanella (2018) found that binge watching was used to aid in viewers’ emotion regulation, allowing viewers to indulge in whatever emotions they preferred depending on what content they decided to watch. The ability to choose from so many types of content escalates instant gratification for the viewer, and instant gratification has been identified as a motivating mechanism for binge watching. According to Roberts (2014), in an impulsive society, we are inclined to amplify gratification in any given moment and ignore future repercussions because we constantly progress from one plane of gratification to another. Because gratification is now at our fingertips, it is more difficult than ever to delay satisfaction. Vast amounts of content on different platforms and ease of gratification are likely to cause a decline in consumers’ self-control, which leads to negative effects of binging.

Reinecke and Hofmann (2016) suggest that media consumption falls into two categories: recreational and procrastinatory. Those with less self-control are more likely to use media to procrastinate their responsibilities, while recreational users are more goal oriented and are able to delay gratification. Panek (2014) suggests that one’s self-control concerning amount of media usage for leisure is affected by how many options are available. Because there are so many platforms of content available, viewers are more likely to give in to temptation despite having more important tasks to complete (Reinecke & Hofmann, 2016).

As a result of instant gratification and lack of self-control, those who binge watch were more likely to impede their own goals (Walton-Pattinson, Dombrowski, & Presseau, 2016). One study found that TV watching was negatively associated with academic performance, which could be because many viewers report watching video content while attempting to finish important tasks simultaneously (Jacobsen & Forste, 2011). Procrastination and declines in productivity due to binge watching often result in the viewer experiencing guilt (Mehra & Gujral, 2018). In some cases, resulting guilt from binge watching causes the consumer to engage in more binging to postpone their responsibilities even longer (Panda & Pandey, 2017). Riddle, Peebles, Davis, and Xu (2018) suggest that at a certain point, binging could reveal characteristics of addiction

in viewers. This specific point where binging is problematic was researched in a study that suggested there was a possible threshold at which binging goes from enjoyable to guiltinducing, with three to four episodes being the optimal binge (Feijter, Khan, & Gisbergen, 2016). Once viewers passed the threshold, guilt increased and the viewing experience was less enjoyable. The addictive potential and decreased satisfaction found in longer binges emphasize the importance of frequency and duration of binge watching.

Binge watching video content has become the new norm in video consumption (Matrix, 2014), and while research has been conducted on its impact on daily activities and productivity, few studies have investigated the emotional outcomes of various frequencies of binging. This study aimed to explore how one’s frequency of binge watching is associated with their emotions toward it. It was hypothesized that there would be a positive association between frequency of binge watching and emotions. Specifically, we hypothesized that a higher frequency of binge watching would be associated with both an increase in loss of control and dependency and a decrease in positive emotions.

Methods

Participants

Participants consisted of 66 students (58 women, 8 men, M age = 19.54 years, age range: 18-23 years) enrolled at a private Baptist university. They were recruited through snowball sampling. There were 9 freshmen, 29 sophomores, 13 juniors, and 15 seniors.

Measures

The scale used to measure emotional effects of binge watching was the Binge Watching Engagement and Symptoms Questionnaire (BWESQ Billieux et al., 2019). Frequency of binge watching is measured by the number of days the participant binge watches per week, scaled from 0 to 7.

Binge watching engagement and symptoms questionnaire

The Binge Watching Engagement and Symptoms Questionnaire (Billieux et al., 2019) is a measure of the emotions and symptoms associated with binge watching. It uses a 7-factor model that evaluates engagement, positive emotions, desiresavoring, pleasure preservation, binge-watching, dependency, and loss of control. These were developed from the literature on addiction, impulse control, and emotion regulation. Items include “I sometimes fail to accomplish my daily tasks so I can spend more time watching TV series” (Billieux et al., 2019, p. 2). Responses are recorded on a 4-point Likert scale that range from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). The questionnaire presented with an alpha reliability coefficient of α = 0.62-0.83, which is sufficient.

Procedure

Each participant completed a Qualtrics survey that consisted of the BWESQ, one question to obtain the frequency of each subject’s binges, and another to assess how long their binges last on average. Demographic information was included

Results

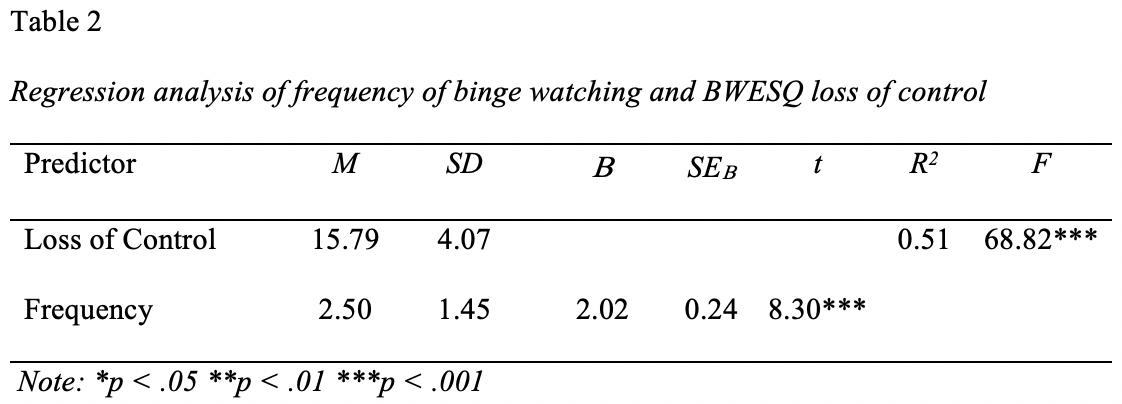

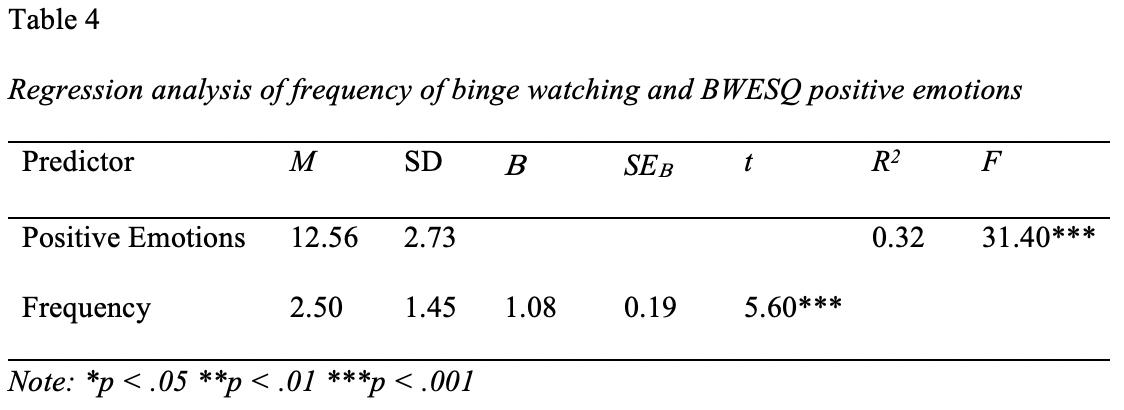

Analyses focused on the participants’ scores in frequency of binge watching and three subcategories of the BWESQ: loss of control, dependency, and positive emotions. Frequency of binge watching had the highest correlation with loss of control, followed by positive emotions and dependency (see Table 1). A simple regression analysis was conducted using R software to determine if there was an association between frequency of binge watching and the three categories of emotions (see Tables 2-4). Frequency of binge watching and loss of control resulted in a significant association with R 2 = 0.51, df = 68.82, p < .001. Frequency accounted for 51% of variance in loss of control. Next, the simple regression analysis for frequency and dependency resulted in an association with R 2 = 0.23, F(1, 64) = 20.47, p < .001. Frequency accounted for 23% of variance in dependency. The final regression was conducted on frequency and positive emotions, resulting in an association of R 2 = 0.32, F(1, 64) = 31.4, p < .001. Frequency accounted for 32% of variance in positive emotions. These results partly support our hypothesis because, as hypothesized, frequency accounted for some increase in loss of control and dependency. However, frequency also accounted for an increase in positive emotions, which does not support the hypothesis.

The results of these tests suggest that the frequency of one’s binging is associated with emotions often connected to binge watching. Loss of control had the highest association, followed by positive emotions, then dependency. Due to the BWESQ subcategories’ significant associations with frequency of binge watching, it is suggested that one’s frequency of binge watching has an effect on their emotions toward it.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to find associations between the frequency of one’s binge watching and various emotions. It was hypothesized that those who binge watch more frequently would experience more feelings of loss of control and Table 1

Table 1. Correlation coefficients between frequency of binge watching and participant scores in three subcategories of the BWESQ

C.

Tables 2-4. Regression analyses of frequency of binge watching and three subcategories of the BWESQ

dependence and less positive emotions.

The statistical analyses conducted supported part of our hypothesis, with positive associations between frequency and loss of control, frequency and dependency, and frequency and positive emotions. Loss of control had the largest association with frequency, followed by dependence and positive emotions. Although positive emotions also had a positive correlation with frequency, the association was smaller than the loss of control. This suggests that those with higher frequencies of binge watching can experience more negative emotions than positive ones. As a result of the higher association between frequency and negative emotions like loss of control and dependency, binging is more likely to have more negative impacts on viewers as their frequency increases.

These findings are consistent with other conclusions in research concerning the negative effects of binge watching such as Mehra and Gujral’s binge watching study (2018). Loss of control and frequency presented with the strongest association, which could be related to the negative correlation between selfcontrol and use of instant media (Panek, 2014). The association between frequency and dependency supports the idea that binge watching can have addictive potential (Riddle et al., 2017). Also, while the association between frequency and positive emotions was not as hypothesized, it could support the suggestion from Gujral and Mehra (2018) that instant gratification offered by binge watching can sometimes overpower the viewer’s guilt over postponing more important tasks and result in an increase of positive emotion.

The current study encountered a few limitations. First was the sample size and demographics. With only 66 participants, a larger sample would increase confidence in the results. The sample also consisted solely of college students and may not generalize to older samples. Lastly, race was not gathered in the demographics, and future research could include race to account for any racial differences that may be present. Another limitation of this research is that only linear regression was analyzed for the variables. A nonlinear analysis on positive emotions and frequency could reveal a nonlinear association to support the idea of a threshold for gratification as mentioned in the study done by Feijter and Gisbergen (2016).

The survey methodology was a slight limitation in this study. Participants were asked to answer the questionnaire as accurately as possible based on the memory of their feelings concerning binge watching. Future studies could employ an observational or experimental approach to obtain information from participants immediately after they binge watch. This would provide more accurate responses because the participants would be reporting the emotions they are feeling in real time rather than recalling how they felt after previous binges. Additionally, our measure for frequency of binging (ranging from never to every day) did not consider the duration of the subjects’ binges. Further research could go beyond frequency to find effects on different durations and time spent binging. Finally, this study’s questionnaire had multiple subcategories for negative emotions, but only one for positive emotions. Future research might benefit from using another measure of positive emotions to provide more equal information on varieties of emotions.

While this study was one of the first to use frequency as a predictor for the emotions often associated with binge watching, the results reflect those of past research, suggesting that higher frequency of binge watching has a predominantly negative emotional impact on viewers. Also, a major implication of past research on binge watching is its effect on sleep. Those who binge watch at a higher frequency tend to have more trouble sleeping, which suggests that not only can binging have negative emotional impacts but also negative physical impacts (Exelmans & Van den Bulck, 2017). Future research done on binge watching could investigate the addictive potential of binge watching in more detail. Also, because binge watching is such a new activity, current research is limited to analyzing short term effects. In the future, researchers will be able to observe long term effects that are not yet present in viewers.

Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge Victoria Anozie for her substantial support and patience in completing this study and her willingness to think outside of the box.

References

Exelmans, L. & Van den Bulck. (2017). Binge viewing, sleep, and the role of pre-sleep arousal. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 13(8), 1001-1008. doi:10.5664/jcsm.6704

Feijter, D., Khan, V., & Gisbergen, M. (2016). Confessions of a ‘guilty’ couch potato: Understanding and using context to optimize binge-watching behavior. Proceedings of the ACM International Conference of Interactive Experiences for TV and Online Video, 59-67. doi:10.1145/2932206.2932216 Jacobsen, W., & Forste, R. (2011). The wired generation:

Academic and social outcomes of electronic media use among university students. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 14(5), 275-280. doi:10.1089/ cyber.2010.0135 Jenner, M. (2016). Is this TVIV? On Netflix, TVIII and binge watching. New Media and Society, 18(2), 257-273. doi:10.1177 Jenner, M. (2017). Binge-watching: Video-on-demand, quality

TV and mainstreaming fandom.International Journal of Cultural Studies, 20(3), 304-320. doi. org/10.1177/1367877915606485 Matrix, S. (2014). The Netflix effect: Teens, binge watching, and on demand digital media trends. The Centre for Research in Young People’s Texts and Cultures, 6(1), 119-138. doi:10.1353/jeu.2014.0002 Mehra, A. & Gujral, A. (2018). Binge watching: A road to pleasure or pain? Indian Journal of School Health, 4(1), 2-13. Retrieved from http://expressionsindia.org/cbse_ programs/health_journal/2018/jan_apr18.pdf#page=10 National Telecommunications and Information Administration. (2018). Most popular online activities of adult internet users in the United States as of November 2017. Retrieved from https://www.statista.com/statistics/183910/internetactivities-of-us-users/ Netflix. (2013).Netflix declares binge watching is the new normal. Retrieved from Netflix.com:https://pr.netflix.com/

WebClient/getNewsSummary.do?newsId=496 Neubaum, G., Kramer, N., & Alt, K. (2019). Psychological effects of repeated exposure to elevating entertainment: An experiment over the period of 6 weeks. Psychology of

Popular Media Culture, 8(1). doi:10.1037/ppm0000235 Panda, S. & Pandey, S. (2017). Binge watching and college students: Motivations and outcomes. Young Consumers, 18(4), 425-438. doi:10.1108.yc-07-2017-00707 Panek, E. (2014). Left to their own devices: College students’

‘guilty pleasure’ media use and time management. Communication Research, 41(4), 561-577. doi:10.1177/0093650213499657 Reinecke, L. & Hofmann, W. (2016). Slacking off or winding down? An experience sampling study on the drivers and consequences of media use for recovery versus procrastination. Human Communication Research, 42(3), 441-461. doi:10.1111/hcre.12082 Riddle, K., Peebles, A., Davis, C., & Xu, F. (2018). The addictive potential of television binge watching: Comparing intentional and unintentional binges. Psychology of Popular

Media Culture, 7(4), 589-604. doi:10.1037/ppm0000167 Roberts, P. (2014). Instant Gratification. The American Scholar.

Retrieved from https://theamericanscholar.org/instantgratification/#.XJQLk6fMzu0 Rubenking, B. & Campanella, C. (2018). Binge-Watching: A suspenseful, emotional habit. Communication Research Reports, 35(5), 381-391. doi:10.1080/08824096.2018.15253 46 Shaw, L. (2018). There are more new TV shows than ever in

America. Retrieved from https://www.bloomberg.com/ news/articles/2018-01-05/netflix-propels-tv-productionsurge-dethrones-hbo-with-critics Walton-Pattinson, E., Dombrowski, S., & Presseau, J. (2018).

‘Just one more episode’: Frequency and theoretical correlates of television binge watching. Journal of Health and Psychology, 23(1), 17-24. doi:10.1177/1359105316643379