25 minute read

The Impact of Social Media on the Short-Term Memory of Teenagers

from Scientia 2020

Katie Nelson¹, Pamela Miller, PhD.²

Advertisement

¹Department of Psychology & Neuroscience, Baylor University, Waco, TX ²Department of Psychology, University of Denver, Denver, CO

Social media sites such as Instagram have increased dramatically in popularity, especially with teenagers. However, there is still research to be done on how social media may influence important psychological growth or aspects of ordinary brain function, such as short-term memory. This experiment collected fifty voluntary participants and measured the impact that social media has on short-term memory in teenagers. Each volunteer was placed into a control (without social media) or experimental group (with social media). The participants were given two minutes to memorize as many words as possible from a 51-word list. Then, they sat in silence or used social media for five minutes. Finally, the participant has two minutes to write down as many words as they could recall. The hypothesis that social media would negatively influence the short-term memory in teenagers was proven correct. The teenagers from the control group recalled more words than those from the experimental group. A possible conclusion drawn from this experiment is that using social media will negatively influence short-term memory and impair recall, while learning or studying.

Abstract

Introduction

Social media platforms are used everywhere by practically everyone. Whether it is a mom waiting to pick up her child or a college student sitting in class, people are occupying themselves through social media. Every upcoming generation seeks for their attention to be captured all the time and social media is that medium. With more people using social media everyday, it is vital to research how this new media affects humans and more specifically their memory.

Memory

Professors Richard Atkinson and Richard Shiffrin has established that memory is divided into three general stages: sensory, short-term and long-term. This idea was first proposed in 1968 and was the subject of both professors’ ongoing studies until 2016. They revealed a new understanding that short-term memory includes the concept of conscious working memory (Shiffrin, 1977). Absorbing most information is done without intention, unconsciously, and the working memory is used to pick up stimuli to remember.

The memory process begins with sensory memory when immediate information is first recorded by senses. It quickly flows to the short-term (or working) memory, which is activated memory that holds information briefly. The working memory specifically is not just a temporary shelf for holding new information, but instead is an active “scratchpad” where the brain actively processes information by making sense of new inputs and connecting them to long-term memories. Long-term memory is a somewhat permanent and limitless storehouse for all information, including skills, knowledge, andexperiences (Myers & DeWall, 2018). Every human records information through this memory-process, but interference in any stage can change the way memories are recorded and stored. This threestep process is widely accepted and used to understand how humans document outside input.

Short-term memory usually requires information to be continually repeated to be retrieved later. Typically, information is held for about 20-30 seconds and then begins to fade. Effortful processing is used to encode new information but requires conscious effort and attention (Loftus, 2018) to keep information in the brain and later stored as long-term memory. These two stages of memory work together to help process and save new information.

A research experiment run by Alan D. Baddeley, British psychologist, and professor of psychology at the University of York explored how memory span is related to the length and occurrence of an English word. Participants in his experiment read aloud different words that had one of two lengths: one syllable and five syllables. He found that recall with the onesyllable length word set was more likely since the short-term memory has a limited life and the more information it is asked to hold, the less likely it will be remembered (Baddeley et al., 1975). It makes logical sense that Baddeley would find that words of shorter length were recalled more than longer ones. The ability to recall correlates with the length of the word in such a way that future experiments should use a variety of words to get a balanced experiment.

Though different aspects of human memory have been studied throughout the years, one thing is clear. Memory can be easily changed, and no memory recalled is a correct permanent representation of the prior event. With this, it is important to

Social Media

Humans are social creatures by nature. In the recent past, people have developed a new way to connect with others without actually being in the same physical location. Social media is a communication tool whereby people use technology to connect with others, share content and network. More importantly, social networking sites create a database for sharing information with others (Hanson, 2018). Examples of social media sites are platforms like Instagram and Facebook. Social media can be used to advertise products, learn new information, check-up on friends and much more. As technology expands, social media is becoming more prevalent around the world. When social media was created, it was intended to be used for giving access to content to those who wouldn’t usually have it, connecting scholars from around the world, helping create new ideas to build the future, and increasing collaboration between different people (Redecker et al., 2010). Depending on the user, social media can be positive. However, today more people are using social media for different reasons.

With the increase of social media users, the world is facing new problems. Distraction is a large problem for students in college and secondary school. Jessica Mendoza, a psychology professor at the University of Alabama, experimented with her colleagues to test how cell phones or social media may influence their learning abilities in the context of a lecture. There was a group of students who kept their phones and one that didn’t. The students who had the cellphones were sent distracting messages during the lecture and then both groups were tested over the lecture at the end. The researchers found that the group that was distracted by the technology performed worse on average than the control group, specifically over the material review at the end of the lecture (Mendoza et al., 2018). This is not a rare occurrence, though. Researchers in another study run by the University of North Texas found that social media interruptions and distractions during medical learning activities (live and recorded lectures) can have an important impact on learning outcomes. The students who were distracted by social media received lower test scores in medical school than their peers (Zureick, 2018). Social media has increased the use of cell phones in class, meetings, social interactions and almost everywhere else. Social media connects people but it should not be abused: evidently, social media can negatively impact people’s lives.

Today, numerous people are wondering what impact social media may have on memory. A study by Scott T. Frein, head of the department of psychology at Virginia Military Institution and his colleagues proved that the frequency usage of Facebook was correlated with memory recall. The researchers used 44 participants. By asking the average amount of hours a day the participant used social media, they were put into two groups: the low-frequency group and the high-frequency group. Then, they gave each person a recall test and compared data. Their results showed that on average, people in the high-frequency social media group had worse vocabulary recall than the other group. The high-frequency group recalled on average about 15% of the words and the low-frequency group recalled on average 22% (Frein et al., 2013). This study showed a correlation between lower recall ability and high usage of Facebook. Their correlation of social media and memory was based on the general previous usage that the participant noted. Even though this experiment was a general introduction, findings like these support more reason to research social media’s impact on human life, especially memory.

Social media becomes more popular with each generation. Teenagers use social media, especially Instagram, more than any other age group (Smith & Anderson, 2018). However, there are extremely few studies involving social media that use teenagers as subjects, instead prioritizing those that are 18 or older. There is a need for studies particularly involving teenagers and social media regarding to short-term memory. To evaluate social media on teenagers, a specific demographic was used for this study: participants ages 14-18 from one high school.

It is presumed that social media will negatively impact short-term memory in teenagers. The researcher hypothesizes that the experiment group using social media during the “study break” will recall fewer words overall. It is expected that the short-term recall of the control group will be higher than the experiment group using social media.

Methods

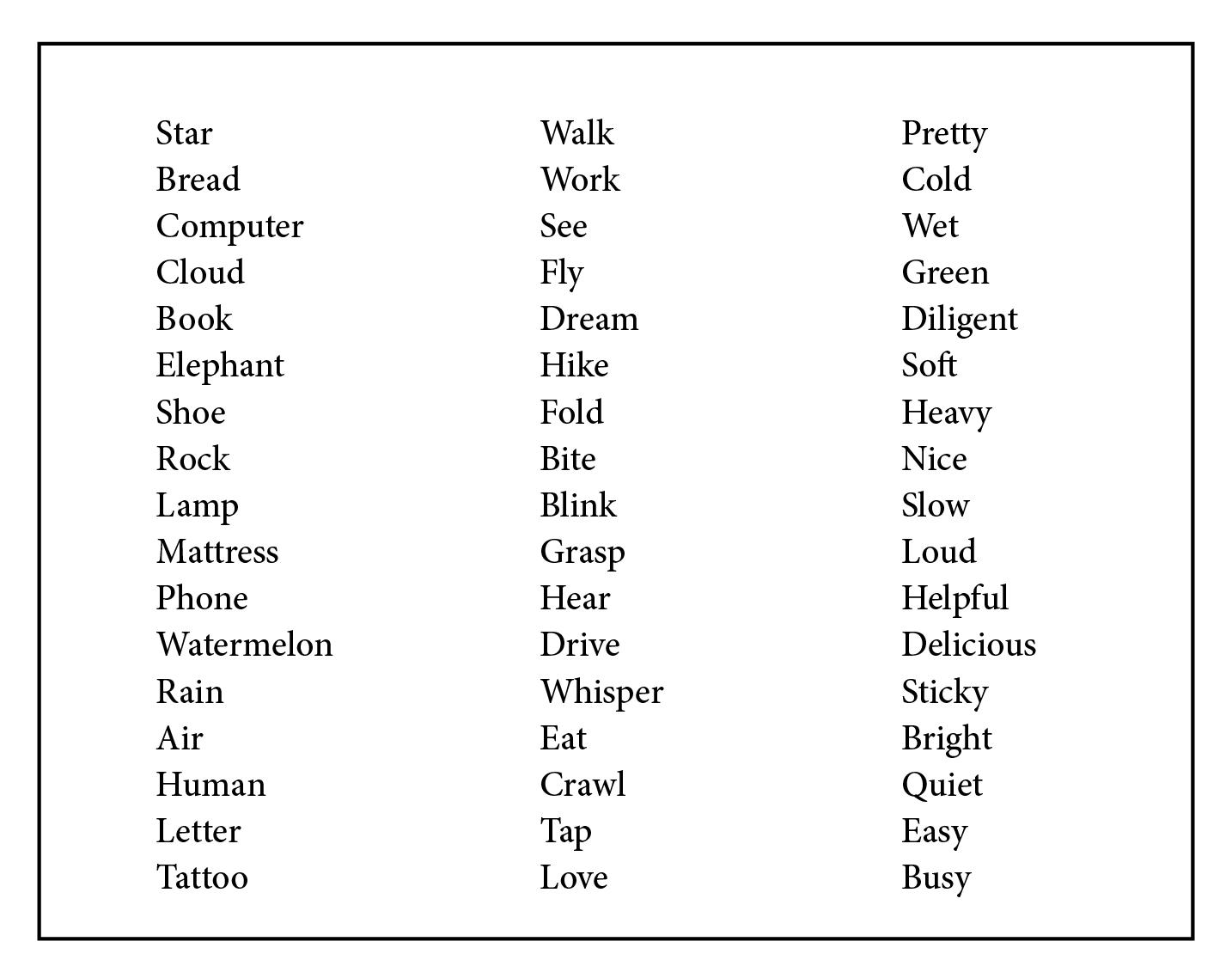

To test the effects of social media on short-term memory in teenagers, a group of fifty high school teenagers (ages fourteen to eighteen) were collected. The researcher publicly advertised for volunteers to participate in the study and participants contacted the researcher through email or in person. The participants gave informed consent to participate and have their data reported anonymously. Each participant studied a list of fifty-one words for two minutes, consisting of seventeen nouns, seventeen verbs, and seventeen adjectives. The nouns were listed on the left in one column, the verbs were listed in the middle column and the adjectives were listed in the right column (refer to Figure 1).

The participants were separated into two groups: the control and experimental group. After studying the list of words for two minutes, the control group participant sat in silence for five minutes, while the experimental group participant scrolled through an Instagram feed, using an account designed by the researcher (Appendix A). The Instagram account followed four accounts to create a feed: a Do-It-Yourself account (@ diy.learning), an account posting nature’s best (@nature), Instagrams official account (@instagram) and the account for the school’s public announcements. After the participant sat in silence or scrolled through the feed, a blank lined piece of paper was given to the participant to write as many words as they could recall for two minutes. If the word was on the list then it was considered correct when counting for total correct words. The participant was not marked down for words they wrote that were not listed or close misspellings. If the participant wrote a word that they had already written, it was only counted correctly once. After the two minutes had passed, the researcher thanked the participant and offered to sign off on one hour of volunteer service for their participation.

To justify this experimental research method, multiple sources regarding social media and memory was analyzed in relation to their method. Because it was observed that the average number of participants in studies of this caliber was around forty to eighty, this study used fifty participants (Frein et. al, 2013; Savill et al., 2018). By advertising publicly and requesting all students to participate, the sample bias (of choosing participants) was eliminated. The researcher chose fifty-one words only consisting of verbs, nouns, and adjectives because other memory tests given in previous studies used these grammatical categories (Baddeley, et al., 1975). This mitigated individual bias toward certain parts of speech. All the words on the list were chosen because of their non-triggering tendencies, varying syllable count and the simplicity of each word considering their neutral connotations. Participants alternated from the experiment to control group to further guarantee random assignment. The participant received two minutes to study the words and another two minutes to write down the recalled words. This is so the words would stay in the short-term working memory and not linger towards long term memory (Craik & Watkins, 1973). To recreate real study habits and circumstances, the break was five minutes, the average time for a teenage “study break” (Epstein et al., 2016) The Instagram account followed four accounts that guaranteed to not show provoking or triggering content, but offered a feed that still captured the audience’s attention. It was important for the Instagram feed to be engaging to resemble the real distractions social media may offer. The accounts used were verified through Instagram, meaning that the accounts had to be neutral and could not be controversial. Towards the end of the experiment, the researcher gave a blank piece of paper instead of a multiplechoice or fill-in-the-blank test to initiate a recall, not retrieval or review, of what the participant remembered.

How does the use of social media, specifically Instagram, influence short-term memory in teenagers? This experiment directly tested social media’s effect on teenagers’ shortterm memory by incorporating Instagram into the test. The time intervals chosen for the studying, break, and recall are complimentary to how long information remains in short-term memory. With the break being only five minutes, the brain kept the words in the working short-term memory for this short time. The study session was two minutes and the recall time was made equivalent to allow enough time for each participant to go over each word but not store into long-term memory. By only using teenagers ages fourteen to eighteen in this study, the method clearly connects to the targeted high school population.

This study followed the theoretical experiment method because it was testing the direct effect of one variable on another. Many studies referenced above were correlational studies, not specific cause and effect. This experiment was not a correlational study because a correlational study can only show whether two variables have a relationship but do not measure the extent to which they affect each other. By using social media during the test, the quantitative results will prove whether social media has a direct impact on the number of words recalled. This study was a one-time experiment because data was collected and analyzed to provide a clear conclusion.

One important limitation of this study is the population size because similar experiments usually utilize a larger sample size, which gives a better estimate of the targeted population. A larger sample size would give more accurate results if this study was being applied to various populations. The ages of the participants of this study range from fourteen to eighteen because few high school teenagers are thirteen or nineteen.

A small limitation to the method was that even though each experimental group participant saw content from the four accounts, that doesn’t mean every participant viewed all the same posts. The followed accounts posted videos and photos frequently so depending on the day, each participant saw similar posts but not necessarily the same photos as the other participants. This was only a small limitation because in the real world, depending on the day and time someone uses social media, they would see different posts no matter how often they use social media. So even though the posts themselves varied, the content was still similar among all participants because they only used social media through the four accounts during this experiment.

In future studies, this method could use alarger sample size to apply to different or larger populations. Due to the availability of resources used and close following of the scientific method, this study is replicable but can be altered in future experiments.

Results

Out of fifty participants, there were thirty-four females, fifteen males, and one unidentified tested. Regarding the specific ages of the teenagers, Figure 2 gives a visual demographic.

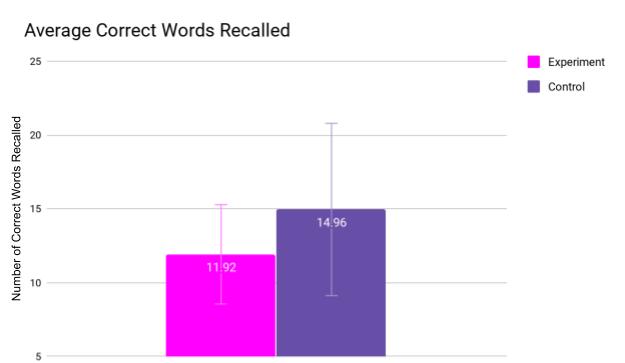

The total correct words recalled for each individual from each group were compared for the control and experimental group (Appendix B). A two-tailed two-sample t-test was used to see if the data collected was statistically significant, meaning the two groups have a relationship that is caused by something other than chance. For the data to be statistically significant, the p-value had to be less than the alpha-level of 0.05. The p-value for this test was 0.0297, showing the data was statistically significant. To detect the extent of the effect of social media on memory, a one-tailed two-sample t-test found the p-value to

10

5

0

14 15 16 17

Age of Participants 18

Figure 2. Age demographic of the participants in this study.

Average Correct Words Recalled

11.92 14.96 Group

Experiment Control

Figure 3. Number of average correct words recalled for each respective group. Error bars depict one standard deviation.

be 0.0148 (also significantly less than 0.05). The average correct words recalled and standard deviations for each group are shown in Figure 3. The standard deviation for both groups differs largely as well, as shown in Figure 3. For the experiment group (social media usage) the standard deviation was 3.3655 and for the control group, it was 5.8344.

The total average words recalled accounts for how many words the participant wrote down and is not dependent on whether the words are correct or not. The total average words recalled for the experimental group were 17.68 and for the control group, it was 15.28.

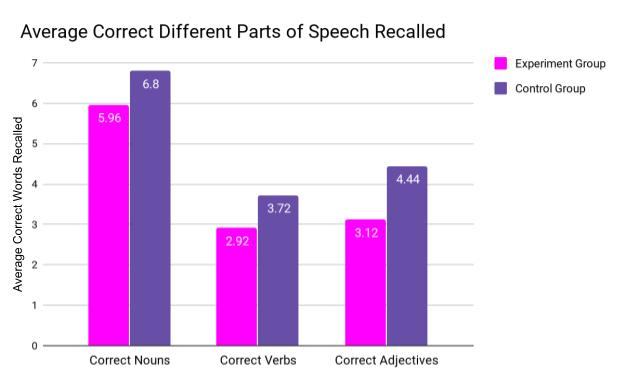

Regarding the actual words, nouns were the part of speech most likely recalled, next to adjectives and then verbs, on average. Refer to Figure 4 for the exact averages of the different parts of speech.

Another observation between both groups was that many of the words recalled on average, had double letters such as in green or mattress. A final observation about the types of words recalled often between both groups was that the participant would usually recall either the first or last term in the list. The first term was ‘star’ (noun) and the last term was ‘busy’ (adjective). Thirty-four out of the fifty participants recalled both

Average Correct Words Recalled

5

4

3

2

5.96

2.92

3.72 4.44

3.12

0 1

Nouns Part of Speech Verbs Adjectives

Figure 4. Number of average correct parts of speech recalled for each respective group.

or either of these terms when writing words on the paper.

These patterns of words recalled between the different groups does not pertain to the exact research the question addressed— how does social media impact short-term memory, in teenagers. However, it does provide insight into why the results may have produced this data.

Discussion

Interpretation and Significance of Results

As stated in the results, the standard deviation had a p-value ≤ 0.05, concluding the results to be statistically significant. The one-tailed t-test showed that the control group had less of an effect on short term memory compared to the experimental group. When analyzing the data collected, the existing hypothesis proved to be correct: social media would negatively impact short-term memory in teenagers.

Comparing the data sets more closely, the total average words recalled for the control group was 17.68 and for the experimental group, it was 15.28. These are all the words written on the piece of paper and counted whether they are correct or not. The total correct average words recalled for the control group were 14.96 and the experimental group was 11.92. The control group had a smaller difference between the correct and total average words recalled than the experimental group (2.72 vs 3.36). It was hypothesized that the neural networks required for short term memory (for students using social media in the experimental group) may have been overwhelmed and would not commit the correct words to memory. The students in the control group sat in silence during the five-minute break and could keep the words in their short-term memory without as much distraction.

Regarding the total correct words recalled, the standard deviation, or the extent of variance from the mean, for the control group was 5.8344 and for the experimental group was 3.3655. Even though both groups had 25 participants, there was a large difference in the standard deviations. A possible hypothesis for the differing standard deviations was that the sample from the control group had a large variance of distractions not controlled in this experiment. This might be because the participants in the control group could have had extremely varying internal

distractions (such as their emotions or thoughts while taking the test) and the experimental group had a similar variance in confounding distractions. If the sample size had been larger, the standard deviations would most likely be smaller. The standard deviations for the control and experimental group may have not been so different with a larger sample size.

When the actual correct words recalled were further examined, a few patterns were observed. By separating the nouns, verbs, and adjectives into three separate columns, it was clear which words were recalled more often. On average, nouns were the most correctly recalled words, then adjectives and lastly verbs. In multiple studies, nouns were recalled more often than any other part of speech because they are more specific than other parts of speech and can usually produce a clear image of the object upon reading (Earles & Kersten, 2000). This also explained why verbs were recalled less often than adjectives because verbs describe a general action that can be recalled with concentration but adjectives can bring a specific image to the brain when reading. Another pattern noticed was that words with double letters (such as mattress, see or pretty) were also recalled more often. A finding by two psychologists, Donna-Marie Wright and Linnea C. Ehri, who study word comprehension in children, found this to be common because people’s knowledge was constrained by certain word structures (Wright & Ehri, 2007). The most recurring pattern, however, was the high frequency of the serial-position effect. This term refers to the tendency to recall information that was presented first and last in a list better than information presented in the middle (Murdock, 1962). The serial-position effect is widely recognized among many studies and explains why thirty-four out of the fifty participants recalled either the first (star) or last (busy) word in the list. No matter which group the participant was in, they most likely exhibited the serial-position effect or most often recalled words with double letters.

Limitations and Implications

The most prominent limitation of the research results was the sample size. It was predicted to be a limitation in the method but was emphasized by the large standard deviations. A larger sample size would have provided more accurate results and a smaller variance from the mean, making the conclusions more applicable to wide general populations. This experiment used volunteer participants from one high school, which also limited the extent to which the study’s results may be applied to other populations. Because the participants were voluntary, there may have been a certain uncontrolled bias because the researcher could not control which students would participate.

If the study was to be repeated, the list of words presented in the three separate columns could be randomly assorted instead of separation by part of speech. This might show that the nouns were not significantly recalled more than the verbs and adjectives because of their positioning on the page. It would not have affected the results pertaining to the question of how social media impacts short term memory, but it could bring differing results involving the words’ certain parts of speech if this data was used for future experiments.

The participants were not tested all on the same day or at the same time of day. This slightly impacted the results or the sample demographic makeup. The date and time were confounding variables; however the testing environments were very similar in noise level and light exposure. The researcher deemed it more important for the testing environments to be similar but didn’t require the participants to all be tested on the same day or at the same time.

This study can draw many implications. Short-term memory was negatively impacted when teenagers used social media during their study break. In 2018, a study found that 89% of students describe their social media use to be almost constant or several times a day (Anderson et al., 2018). It can be inferred that since so many students use social media frequently, they may use it while studying, as a distraction, or simply use it in between study sessions. The information received while studying goes through the short-term memory, into working memory, and usually stored in long-term memory. This experiment clearly shows that using social media may negatively impact the way information travels through shortterm memory and eventually affects the amount of information stored in long-term memory. In turn, this could affect the recall of information and future test scores. This study does not show that bad test scores are caused by social media use, but future research could show a correlation.

Conclusion

Social media interfered with the recall of the words presented in this experiment, leading to the conclusion that social media negatively impacted the short-term memory in these participants. The hypothesis that predicted this result aligns with research that indicates short-term memory is not limitless. Social media use may have overwhelmed short-term memory. With the conclusion being that social media negatively impacted short-term memory in teenagers, further research could be done to investigate the universality of this conclusion.

Future Research

This experiment could be changed in multiple ways and the data could be used for different research questions. First, if keeping the original question, the sample size could be larger and/or gather participants from different places. By doing this, the results may be applied to a more general population.

Using different words, such as those that have a pattern in their structure or sound, could produce different results (Wright & Ehri, 2007). The words used in this experiment were random, neutral, and were not connected through meaning.

This experiment could also use other social media sites like Facebook or Snapchat. Instagram was used as the social media platform for this study because it is the most commonly used platform today for this age group (DeMers, 2017).

Different aspects of the raw data could be more closely studied. For example, the effect of gender and age differences in participants could be analyzed and correlated to short term memory. To analyze deeper, the actual words of an experiment could be examined more closely for patterns. For instance, a researcher could evaluate how many syllables are in the words most frequently recalled or determine which vowels are most frequently recalled.

There are a few related questions that could be asked based on these findings. What would happen if the sample population

was increased to all ages, not just teenagers? Since teenagers use social media more than any other age group, (Smith & Anderson, 2018) the results may be vastly different for someone older or younger. However, by limiting the sample size to just teenagers, this experiment could be focused on the group most affected by the distraction of social media. This research could be expanded to the correlation between study habits and test scores. If a student uses social media frequently while studying, their memory will be weakened, and the information may not be retained. When it comes time for the test, would the average student that studied with no social media distraction perform better than the average student that did use social media while studying? With further research, repeating experiments like this one, bigger implications and connections could be drawn to answer the real-world effects of social media on memory.

References

Anderson, M., Jiang, J., Anderson, M., & Jiang, J. (2018, November 30). Teens, social media & technology 2018. Pew

Research Center Baddeley, A. D., Thomson, N., & Buchanan, M. (1975). Word length and the structure of short-term memory. Journal of

Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 14(6), 575-589. Craik, F. I., & Watkins, M. J. (1973). The role of rehearsal in short-term memory. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal

Behavior, 12(6), 599-607. DeMers, J. (2017, March 28). Why instagram is the top social platform for engagement. Earles, J. L., & Kersten, A. W. (2000). Adult age differences in memory for verbs and nouns. Aging, Neuropsychology, and

Cognition, 7(2), 130–139. Epstein, D. A., Avrahami, D., & Biehl, J. T. (2016). Taking 5: work-breaks, productivity, and opportunities for personal informatics for knowledge workers. Frein, S. T., Jones, S. L., & Gerow, J. E. (2013). When it comes to Facebook there may be more to bad memory than just multitasking. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(6), 2179- 2182. Globerson, S., Levin, N., & Shtub, A. (1989). The impact of breaks on forgetting when performing a repetitive task. IIE

Transactions, 21(4), 376-381. Hanson, J. (2018). Social media. World Book Student. Loftus, E.F. (2018). Memory. World Book Student. Mendoza, J. S., Pody, B. C., Lee, S., Kim, M., & Mcdonough, I.

M. (2018). The effect of cellphones on attention and learning: The influences of time, distraction, and nomophobia. Computers in Human Behavior, 86, 52-60. Murdock, B. B., Jr. (1962). The serial position effect of free recall.

Journal of Experimental Psychology, 64(5), 482-488. Myers, D. G., & DeWall, C. N. (2018). Myers’ Psychology for the

AP® Course (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Worth. Redecker, C., Punie, Y., & Ala-Mutka, K. (2010). Learning 2.0 promoting innovation in formal education and training in europe. Sustaining TEL: From Innovation to Learning and

Practice Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 308-323. Savill, N., Cornelissen, P., Whiteley, J., Woollams, A., & Jefferies,

E. (2018). Individual differences in verbal short-term memory and reading aloud : semantic compensation for weak phonological processing across tasks. White Rose

Research Online. Shiffrin, R. (1977). Human memory: a proposed system and its control processes. Human Memory, 1-5. Smith, A., & Anderson, M. (2018, September 19). Social media use 2018: demographics and statistics. Pew Research Center Wright, D., & Ehri, L. (2007). Beginners remember orthography when they learn to read words: The case of doubled letters.

Applied Psycholinguistics, 28(1), 115-133. Zureick, A. H., Burk-Rafel, J., Purkiss, J. A., & Hortsch, M. (2018). The interrupted learner: How distractions during live and video lectures influence learning outcomes: Study interruptions and histology performance. Anatomical Sciences Education, 11(4), 366-376.