6 minute read

Taking A New Crack at the CELLULOSIC CODE

By Luke Geiver

Blue Biofuels is trying to grow in multiple areas. From its home state of Florida, the aspirant advanced biofuel production company is trying to expand its knowhow and commercial readiness with a novel mechano-chemical cellulosic ethanol process. The Florida team is also working to streamline a feedstock growing and harvest operation that will allow for the use of king grass as its main source of cellulosic material. Outside of the Sunshine State, the Blue Biofuels leadership group is trying to gain the support of additional investors, all while working to crack the code to true, cost-effective commercial-scale cellulosic ethanol production. We checked in with two company executives to see where the company is at on its cellulosic journey and how much of that historically-tough cellulosic code they’ve figured out.

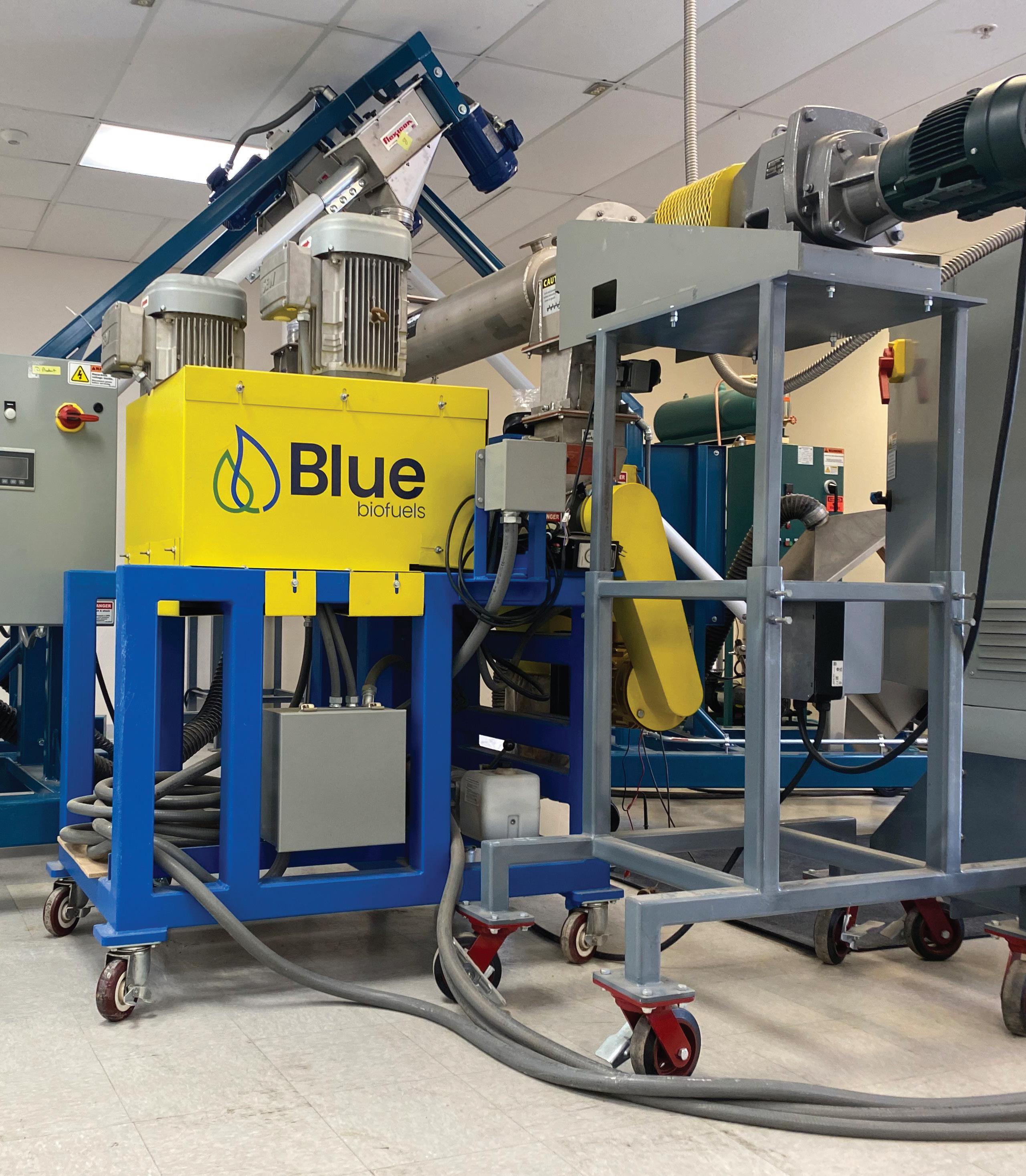

Blue Biofuels Production Approach

Using any biomass ranging from grass to agricultural waste, the process starts by shredding the feedstock down to size. A recyclable catalyst is added to the shredded biomass, fed into a new CTS Reactor, broken down into soluble sugars that are then fermented into ethanol. The byproduct is a high-purity lignin. As history in the cellulosic ethanol production space has proven, this concept or previous versions of it are easier said than done.

Both Ben Slager, the new CEO with a history in tech and chemicals and the commercial build-out of such related entities, and Anthony Santelli, the COO with a background in managing companies and working in venture capital, know that cellulosic ethanol isn’t easy.

“In the past a lot of other companies have tried to create cellulosic biofuels, and those processes used were not economical,” Santelli says. “But we have finally been able to crack the code. It is a new process we’re using that hasn’t been tried before.”

The new process is a combination of mechanical and chemical. On the mechanical side, Slager and team created a roller system that presses the shredded feedstock into the reactor with the catalyst mix.

“What we have done is to create molecular contact between the catalysts and cellulosic material,” Slager explains. “Under the right conditions, the cellulose breaks up into soluble sugars.”

According to Slager, the process creates “a very intimate contact with the catalysts,” and it goes very quickly. Reaction time hap- pens in under a minute, a vastly different time than the hours or days seen in other systems, he says.

Slager basically invented the new system— with a bit of help—when he took over as CEO, and the results have propelled Blue Biofuels to its current state of development. The new reactor was developed with strategic partner K.R. Komarek, a global industry leader in briquetting, compaction, and granulation equipment. According to Blue Biofuels, K.R. Komarek has extensive experience and knowledge on equipment design and production of machines at commercially relevant throughput of up to 50 tons/hr.

When Slager announced in August 2022 the results of pilot scale CTS reactor testing using the compaction and roller elements designed in part by K.R.Komarek, he said the new design features were scalable and should have the same success at commercial scale.

On the catalyst side, Blue Biofuels has turned to a licensing option with Vertimass LLC, a California-based company that obtained a license for its catalyst from Oak Ridge National Laboratory. The catalyst used has been proven to convert ethanol into a hydrocarbon blendstock for use in transportation fuels, including sustainable aviation fuel.

Vertimass obtained worldwide exclusive rights from ORNL in 2014. They call it the Consolidated Alcohol Deoxygenation and Oligomerization (CADO) tech. CADO is simple, Vertimass says, and requires a single reaction system that results in low capital and operating costs.

At the heart of CADO is an inexpensive catalyst known as a zeolite. The zeolite catalyst directly produces longer hydrocarbon chains from the original alcohol, including ethanol, and replaces a multi-step process with one that is more energy efficient.

In recent years, zeolite catalysts have been in the research spotlight by chemical engineers and chemists in the petrochemical space. As an alternative to fluid catalytic cracking of crude oil, petrochemical engineers have been studying the synthesis process known as methanol-to-hydrocarbon reaction, a process that can convert many biomass sources into methanol. The catalyst used for that process: zeolites.

The catalysts themselves are crystalline microporous structures that have regular pore size and are friendly to industrial processes.

Through the work of Vertimass, Blue Biofuels has found an option that works for its cellulosic production ambitions. Slager and Antonelli believe it gives them the lowest cost option to turn alcohol into jet fuel. Vertimass' version produces chemical building blocks BTEX (benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene and xylenes). Slager and team believe the advantages of the Vertimass option are many. It allows for a single step in production that can either be built from the ground up or bolted on to an existing process. There is no need for hydrogen. The entire process produces high liquid product yields with complete ethanol use. Reaction times can take place at an atmospheric pressure of 275 to 350 degrees Celsius. The catalyst itself is very robust. There is a possibility of replacing molecular sieves and potentially rectification through the ability to use 5 to 100 percent ethanol concentrations. Overall, the process uses less production energy across the plant and less water.

FLORIDA FEEDSTOCK: Blue Biofuels is handling its feedstock management mostly in-house. The company is currently working with growers to develop enough king grass in Florida to feed its future operation, a proposed 500,000 gallon per year biorefinery.

“We are working to industrialize it and manufacture larger volumes of the feedstock,” Slager says.

Growing Cellulosic Feedstock In Florida

To bring its cellulosic vision into fruition, Blue Biofuels is taking its feedstock in-house. The company is currently working with king grass, a 15-foot tall grass that grows well in Florida’s climate. The grass can be harvested twice per year and offers a significant carbon reduction compared to most other feedstocks. While corn provides the feedstock to produce roughly 500 gallons per acre, Slager says, the king grass option can provide up to 3,500 gallons an acre per year.

To ensure it has access to the feedstock, Blue Biofuels has leased a total of 182 acres in southwest Florida to grow, harvest and transport from the king grass it needs. According to the company, the land should provide sufficient feedstock to create around 500,000 gallons of ethanol per year. In addition, it will be optimized for planting, growing and harvesting at large volumes.

PRODUCTION PLANNING: To ensure it has access enough feedstock, Blue Biofuels has leased 182 acres of land in southwest Florida to grow, harvest and transport the king grass it needs. The company intends to lease additional land to allow for continuous cycles of king grass planting and harvesting, similar to what's shown here.

The growing team will stagger when the grass is planted. The amount of material that needs to be harvested at any given time will put the transport needs in the spotlight every two weeks or so, Slager says.

“We expect to sow this additional land in a manner to allow for continuous cycles of planting and harvesting to yield a regular, uninterrupted supply of ready-to-process king grass,” Slager says.

Someday, the company may look at other feedstock possibilities, but for now it is king grass in Florida. The goal is to use it at a 500,000 gallon/year demonstration plant in Florida using the mechano-chemical process already proven at pilot scale.

Blue Biofuels Continues Growing

Blue Biofuels is actually the second iteration of the company. Until mid-2021, it operated under the name Alliance Bioenergy Plus. But even before the name change, Slager and Antonelli were actively turning things around and resetting the company’s path to the trajectory they feel it is on today.

Slager, an investor with a unique background in tech, chemicals and helping companies go commercial, joined the company in 2016. Since then, he and Antonelli have turned the company around. The redesign of the bioreactor system, along with the Vertimass agreement and overall vision of feedstock usage has changed the trajectory. Despite Blue Biofuel's past challenges, Slager and Antonelli both say the company's preservation of existing investors, and the addition of new ones, after its realignment offer validation of its potential.

“The unique selling point is that we produce a fuel with 80-percent carbon reduction,” Antonelli says. “That is the main driver. That we make real clean biofuel.”

Slager says this is not the first time he or others on his team have done a job like this one. You know those little chips on your debit card? Slager was involved with designing and bringing that to market.

The current effort is different than all the rest, however. The market is bigger. Slager knows that. Ask him about the electric vehicle sector, European biofuel needs or any other big concept topic that will impact generations to come and he can wax poetic with facts and philosophies gleaned from his broad entrepreneurial experience. Antonelli connects the current version of the company to investors, both new and old. For the past few years they’ve been receiving several patents, adding team members from engineering and biopolymer sectors, leasing land and taking the expected steps of a confident, growing company.

They believe they have cracked the code like those before them weren’t able to. What happens in southwest Florida on 182 acres in combination with another site created to put that mechano-chemical process to the test will tell how much cellulosic code breaking they have truly done. The work and the effort it will require is something Antonelli agrees with Slager on.

“The scale and potential of this project,” Slager says, “will be the biggest of all my previous ones.”

Author: Luke Geiver Contact: editor@bbiinternational.com