7 minute read

SAF IN THE BIG SKY STATE

BY SUSANNE RETKA SCHILL

As of late February, Montana Renewables LLC claims the distinction of being the largest sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) producer on the continent, and expects to maintain that status when a planned expansion is completed next year. “We’re a couple weeks away from being North America’s largest SAF producer, and nobody knows it,” Bruce Fleming, executive vice president, tells SAF Magazine in late January. “We’re an operating company of engineers. We have our heads down, thinking about equipment all the time. And we didn’t tell our story.”

The story, he says, is that Montana Renewables is ahead of the curve. “Everybody’s talking about SAF. We’re doing it. Everybody wants to build a project. We’ve built it. And everybody talks about scaling up and supplying volumes. We’re supplying them.

“We’re going to get better at telling our story,” he continues. “Maybe someday, I’ll walk down a jetway and see our poster on the wall.”

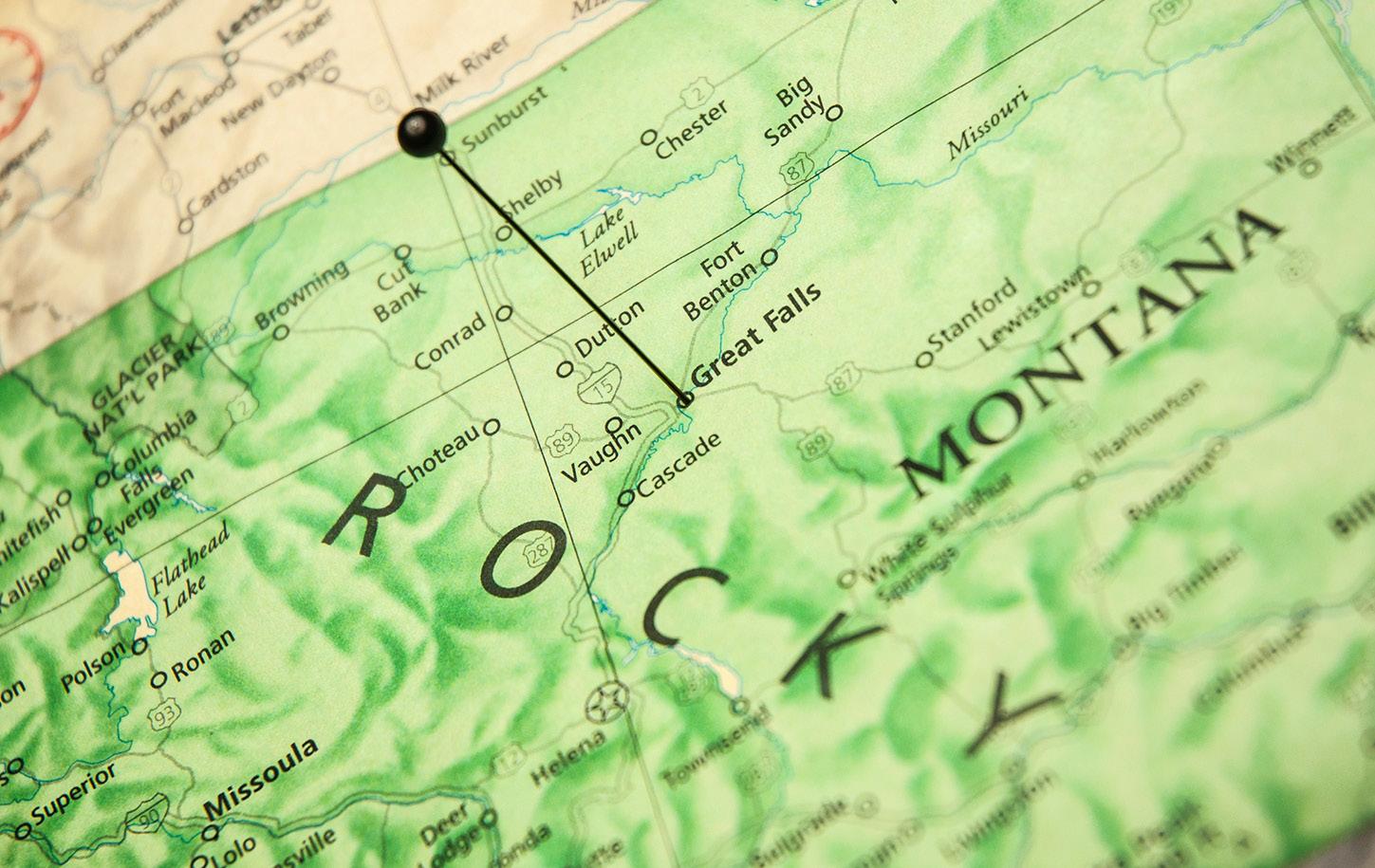

The story is one of fortunate timing, the ability to pivot from an initial focus on re- newable diesel to a greater focus on SAF, on top of a favorable location. Montana Renewables’ facility in Great Falls, Montana, is on the site of a 100-year-old refinery acquired in 2012 by parent company Calumet Specialty Products Partners LP. In early 2021, Calumet announced plans to reconfigure the oversized hydro cracker built in 2016 to process 10,000 to 12,000 barrels per day (bpd) of renewable feedstock into renewable diesel.Things moved quickly, and by fall, financing closed, a ribbon-cutting ceremony was held and an air permit approved. In November, Calumet announced the creation of Montana Renewables as a wholly owned, “unrestricted pure-play re- newables subsidiary.” A few months later, in next quarter’s earnings call, Calumet announced off-take contracts had been executed with three primary customers, including Phillips 66 and Chevron Renewable Energy Group, plus feedstock purchasing was progressing better than expected.

Montana Renewables’ retrofitted process came online at half capacity in December, starting up on tallow to produce renewable diesel. Full capacity was reached by the end of Q1 after the sequential commissioning of renewable hydrogen, SAF and feedstock pretreatment systems. “We’re advertising 12,000 bpd of renewable feedstock,” Fleming says. “That’s about 180 million gallons per year. Of that total, most is renewable diesel. The SAF portion that we sold is 30 million gallons per year.”

Engineering and procurement is underway for a 2024 expansion to process 20,000 bpd, with the ability to flex between all renewable diesel or all SAF, he continues. “There’s a huge, backed-up demand for SAF. We have the capability to offer SAF at a price parity with renewable diesel, which those with older generation technology can’t. They need a premium for SAF or they are not going to make any.”

Montana Renewable’s cost advantage is partly due to its decision to deploy the latest technology from Haldor Topsoe in its renewable diesel retrofit. “The new catalyst system has better yield performance, and it’s now economic to make SAF when it didn’t used to be,” Fleming says.

Topsoe Managing Director for the Americas, Henrik Rasmussen, attributes much of the improved SAF economics to the incentives in the Inflation Reduction Act that is leveling the competitiveness of SAF compared to renewable diesel. That said, Topsoe’s Hydroflex processes offer some advantages. The company has developed a new suite of proprietary catalysts for fats, oil and greases that includes optimizing the jet fraction, if desired. The

Topsoe process also utilizes catalysts for the hydrogenation process to remove oxygen from the triglycerides as water, unlike the more common decarboxylation process that removes oxygen as CO2. Not only does that keep the carbon in the fuel fraction, thus increasing yields, but it eliminates the need for an amine tower to scrub the CO2 , thus lowering energy consumption.

An added advantage for those retrofitting oil refineries is that much of the equipment is there, Rasmussen says. “We reconfigure them a little differently, but we use practically everything that’s there. And they have a lot of infrastructure: tankage, loading docs, control room, wastewater system—so there’s a lot of savings.” A revamp also saves time, taking less than half the time of a greenfield build.

“Calumet’s revamp is a great success,” Rasmussen says. “It’s a great revamp. We got it up and running very quickly with Bruce and his team. They’re running and making on-spec product. And now they’re ready for the next phase. I’m sure it will be just as successful, because it’s a great team. They understand how to run the units. It will be up and running in no time.” Adding the systems to enable jet optimization is done while the plant is running, he explains, with new equipment installed in parallel. Tie-ins are completed during a scheduled turnaround time. “It does require a little more equipment, more piping, extra catalyst and takes time,” he adds. “Is it difficult? No. Does it cost money? Yes.”

Fleming says the last piece of the needed financial package for the expansion is nearly complete. “We’re being thoughtful, but we think the Inflation Reduction Act has cleared the way for expansion to be economic.” SAF incentives in the IRA help the jet fuel economics compete with renewable diesel, starting with both fuels now eligible for the blenders credit for advanced biofuel. When the Clean Fuel Production Credit begins in 2025, SAF will be eligible for a tax incentive starting at $1.25 per gallon, increasing with each point of improved carbon reductions better than the 50% reduction threshold, to a maximum of $1.75 per gallon.

“The doors have opened for more people to get in,” Fleming continues. “But most have to make an investment, because the [renewable diesel] plants that are in existence don’t have the capability to recover the renewable jet, because it wasn’t economic. They’ll have to retrofit. Luckily for us, we had that capability in place when we did the conversion.” The retrofit is relatively simple, he explains, but takes time for engineering, ordering long-lead equipment, applying for permits as needed, plus the actual construction work. “That whole cycle, especially at a larger scale, takes 18 to 24 months,” Fleming says.

Logistics Advantages

Based in Great Falls (population 60,000) in central Montana, just 100 miles south of the Canadian border, Montana Renewable’s location is a strategic advantage for two reasons. One, being located on the Burlington Northern Santa Fe main line gives access to cities with major airports, including several in West

Coast low-carbon fuel markets. Reason two is that roughly 2 million acres of canola are grown in the northern tier counties of Washington, Montana, North Dakota and Minnesota, with 10 times that grown in Canada’s prairie provinces. Long approved as a biodiesel feedstock, the canola pathway for renewable diesel and SAF received EPA approval in December. In the U.S., canola’s carbon intensity (CI) score comes in at about 49 grams, compared to soybean’s at 53. In Canada, however, Fleming points out that canola scores a CI in the low 20s, which he understands is because of a different assessment of land use change in the Canadian models. One buyer, he adds, has specified Canadian canola oil be used in their fuels. “We’re in the right part of the world to run canola, while the guys on the Gulf Coast are going to run soybean oil. But those are food crops, so you’re headed for food versus fuel.” The airlines don’t want to get near that potential controversy, he points out. Their goal is to become carbon neutral. Thus, the company’s proximity to an emerging nonfood oilseed crop in the northern plains—camelina—is another strategic plus.

Camelina’s CI score of approximately 20 puts it on par with tallow and distillers corn oil, Fleming says, and it could score even better. “There’s a company in California, Global Clean Energy Holdings, that says it’s an 8 CI for them because they are going to integrate the camelina crushing with their renewable plant. They go further and say it could be negative. They’re burning natural gas to get the energy for the process, and if they tie in renewable natural gas, they could get a negative CI score.”

“There’s definitely a line of sight for carbon neutral,” Fleming says. For Montana Renewables, that will include camelina as crop production expands in the region. “The second you start paying farmers for something they were going to plow under in the spring, it’ll come into commerce,” he says, adding that one of the camelina developers is headquartered in Great Falls. Montana Renewables also has set aside land, working to attract an oilseed crusher to the site.

Another carbon reduction strategy deployed by Montana Renewables is eliminating natural gas in its process, Fleming adds. Catalysts aren’t perfect, he explains, converting roughly 95% of the feedstock into SAF, renewable diesel and renewable naphtha with the remaining byproducts consisting of renewable natural gas, propane and offgases. “We’re using the byproducts in a closed loop in our process, coming back to hydrogen production,” he explains. Next up is to figure out how to get credit for the plant’s electrical feed coming from hydroelectric dams, rather than using the average fuel mix.

The final value of carbon reduction remains to be seen, as the carbon market matures and the specifications around carbon accounting evolve. “Right now, it’s not level,” Fleming says. “Every LCFS geography wrote its own rule. California, Oregon, Washington and British Columbia rules are all incrementally different. The Canadian federal rule will be different yet.”

All of this is rapidly unfolding, according to Fleming. “We’re in on the ground floor. We’re producing it the way the industry wants it produced, so we can comply with this nest of specifications,” he says, listing the blenders tax credit, the LCFS credit, and RINs—all of which add value to the fuel. “The customer takes the environmental attributes,” he adds. “What they do with that is their business. They’re going to claim they reduced X amount of tons of CO2 , but X depends on which rule.”

Author: Susanne Retka Schill Freelance writer, SAF Magazine