14 minute read

BOOKS

from MONEY ISSUE 61

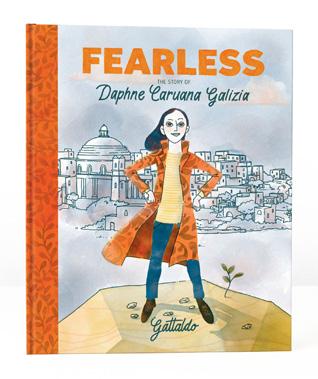

FEARLESS

Malta: 6 October 2017—a leading Maltese journalist is killed in a car bomb. MONEY delves into press freedom and how one can communicate its importance to children in a simple manner. One attempt is a picture story book by Gattaldo celebrating Daphne’s life, to be launched soon here and in the UK…

Advertisement

M It is vital to teach children on the importance of Press Freedom and bring about awareness that journalists are out there to give us an accurate picture on the goings-on, including scrutinising the work of the Government and Opposition. But do you feel that young children will get the gist in the end?

G Think of the numerous times in history that disclosures by journalists helped to change things for the better, to impeach corrupt political leaders or to bring about change through elections and yet, for some reason, polls indicate that journalists are very unpopular now. In this era of challenge to professional journalism, its contribution deserves highlighting. I believe that a big part of the reason for the public’s mistrust of journalists is borne of the public’s inability to distinguish between true and fake news, information and propaganda. Social media has put a spotlight on our lack of media literacy. How do we make sure our children are more prepared?

It’s best here to specify the age range (6–11) that my book is targeted at. It’s an essential time of a child’s development when they are spending more time away from their parents and interacting with media more independently, therefore suddenly encountering a lot more unsupervised information. They also start to develop an understanding of abstract concepts like poverty, unfairness, and emotions.

Don’t underestimate children. They don’t need anyone telling them what to think. I believe children need guidance but above all what they need is a safe space for discussion.“Fearless, The Story of Daphne Caruana Galizia”tells the life story of a journalist with whom we are all familiar. The book aims to encourage children to be independent thinkers, to inform their opinions and to persevere in fighting for what they believe in. The book provides context and perspective, and that is what children need to make sense of what journalism brings

to society. From experience, I warn parents that this book will whip up plenty of questions from their children—the learning certainly doesn’t end with the book.

M The murder of Daphne shocked the whole nation. What were your first thoughts on hearing what had happened? Such murders are not synonymous with Malta. Did you ever imagine something of this sort would happen on our tiny island?

G I was confused and couldn’t think straight. My first thoughts were those of someone who’s just lost a dear friend. It was the pain of personal loss. I don’t recall thinking much What I hope is for the book to spark a conversation between children and their parents, which leads to an appreciation of the value of journalism to a progressive democracy about the circumstances at the time. The shock was the one that you experience when tragedy hits you personally. We go about life thinking bad things happen to other people. When the loss is close, it’s a rude awakening. To make things worse, I’d had a rough year during which my mum died, and a close friend had committed suicide. In terms of the archipelago, I can’t help but feel that the rot had been a long time coming. To the Maltese, the word ‘morality’ has always been limited to sexual virtue. I’ve found Malta can sometimes be indifferent to ethical principles. I believe that a country gets what its people sow, so the pickle the archipelago finds itself in, and the vacuum in political representation is only a reflection of its culture. Let me give you some examples of the crisis in values, and I apologise beforehand if they seem like sweeping generalisations. Most people locally look at the European Union as a cash cow rather than as a tool for solidarity between a group of countries. Most would gladly avoid paying VAT or tax if they could get away with it and never make a link between tax and the provision of services. A significant number feel no empathy for anyone who they consider different to them. I know this sounds harsh, but we’ve brought this upon ourselves, and there is no other way about it. We have become complacent about corruption because we believe we might lose our privileges.

M The murder exposed Malta’s dark side. In your storybook, what do you try to bring out for children to connect to the story? Is your aim to have the late journalist emerge as a storybook hero although this

happened for real?

G It’s about a girl, a young woman, a mother who believed her country could do better and did something about it. Like any other human being, she will inevitably have her weaknesses, but that is beside the point. I wanted to celebrate that which Daphne excelled in. Yes, the book does portray her as a heroine as much as she stood firm even when it seemed she was on her own in sticking her neck out. It takes great courage in not giving up when you could have an easier and more comfortable life by acquiescing. This is how great people change things, not by going with the flow.

The story starts with her childhood and those events which formed her character. This is important in getting young readers to connect. Representing the evils which Daphne stood up to with her writing presented a challenge. How do you explain corrupt power, for example? In one spread, that power is depicted as an all-male Hydra monster in suit trousers. I also wanted this to represent the strong element of misogyny in those critical of Daphne. She’s always been characterised by her detractors as a witch (is-saħħara tal-Bidnija), that centuries-old stereotype of misogyny.

M Do you feel this book will spark more enthusiasm among children to pursue journalism as a career—something that isn’t pushed much here in Malta in schools—or will it instil fear among them?

G I had many a discussion as to whether I should include the assassination in the story. I concluded that the book aimed to celebrate her life and journalism not focus on her demise. What I hope is for the book to spark a conversation between children and their parents, which leads to an appreciation of the value of journalism to a progressive democracy. Who knows if it touches something more profound and, because of it, end up with more investigative journalists with a desire to change the world for the better? Personally, I’d be happy if the book inspires just one child to pursue journalism or even hold it in high regard.

M Tell us more about your informative website which tallies with your storybook on the late journalist?

The websitefearlessdaphne.comstarted as an online presence for the book, but the more I worked on the book, the more I felt the need for a website that had a broader purpose. Two years ago, a report by a UK all-party group found that 60.9% of teachers in primary and secondary schools believe that children’s wellbeing is impacted heavily by fake news. It also found that only 2% of children have the critical literacy they need to tell if a news story is real or fake. This is where the problem lies, or rather, where the solution lies. If children are given the tools to interpret information, the problem would no longer exist. Fearless Daphne is an attempt at a journey of discovery in journalism, and it is one I hope children, parents and educators will join me in.

Ed tells stories for a living, running a bustling brand and digital agency called Switch. When he’s not there, he engages in a host of activities that don’t involve actual physical activity—mainly related to food, film, travel, and photography.

DESIGNING FOR UNCERTAINTY

It is in times of uncertainty that we need to rise to change and to design a better future. Ed Muscat Azzopardi explains.

After the second world war, there was hope and loss and a community that was closer than it had ever been, united by a feeling that collective will could help lift the planet out of its misery. All the technology that had served the war effort was being repurposed— faster airlines so we could travel the world economically, more efficient and affordable cars, and we even had the promise of a man on the moon. Imagine that.

But that feeling of unity took just a decade to dissipate once the Cold War gripped the world and imbued it with fear. Product and technology design was on an accelerating spiral of innovation, driven by one of two broad sentiments that pervaded the developed world—the optimism of the space race and the fear of the bomb.

Design and creative were broadly split into two, echoing the main sentiments of this polarised zeitgeist. One did not replace the other. They coexisted and spoke to the audiences that identified with each side. The pessimistic mostly engaged with design and story based on fear while the optimistic gobbled up the tales of a space-faring species.

You couldn’t buy a toaster that didn’t look like it belonged on the highly stylised illustrations of what man’s first base on the moon would look like. From Dr Strangelove to The Sound of Music, movie posters told the tale of two stories that competed for the attention of a public that was willing to pay to watch a story that reinforced their position.

How do we tell the story of our brand or product during a time of collective concern? Which side would we like to take? What matters is that we pick a direction and create remarkable, functional creative. This is not a time to be silent.

We start by looking at our audience. Who are we speaking to? What’s on their mind right now? What’s the collective sentiment?

And what version of reality is most likely to resonate? During the best of times, there is no single sentiment that is likely to echo with everyone. But during the worst of times, it is easier to have a finger on an almost ubiquitous pulse.

Uncertainty is the one certainty. It is on the minds of many, and it is an unnatural state for the human condition—we like to know where we are and where we’re going, at least most of the time.

Economic hardship is also a widespread state or cause for concern, a state that’s compounded by general uncertainty. If I’m in a financial pickle now and can’t see when this will end, the concern is even more acute.

Where does design fit in? Well, good design always fits in. Every epoch left its mark by producing work that was right for its time, and that survived to tell the tale. The excesses of the Art Nouveau movement during the glittering 20s quickly gave way to the more restrained Art Deco style that was considered more appropriate to the Great Depression. The 1950s, a decade that we keep drawing design inspiration from to this day, was a period of great optimism sandwiched between the crippling effects of WWII and the grip of fear of the Cold War. It gave us bold colour, optimistic product design, an unusually rich spread of typography, and the

feeling that all will be forever good with the world.

And good design that is entirely in tune with the times can leave effects that linger decades after the original work was produced. Consider the incredible canon of Dieter Rams’ work for Braun. It has been cited as the significant influence for the design of an incredible spread of products, including overt tributes by the likes of Jony Ive when presenting the iPod—arguably the big bang for everything Apple that succeeded it. Le Corbusier’s beautiful functionality and unashamed portrayal of structures endure— can we look at a building like Renzo Piano’s parliament in Valletta without seeing what Le Corbusier pioneered in the 20s?

In a reality where our homes have suddenly become the majority of our surroundings, how do we react to the sweeping tide of minimalism that has been rearing its head for a long time now, aided and abetted by the likes of Marie Kondo? Now that we are captives in our own home, design has the opportunity to focus far less on pure utilitarianism and must bring joy and comfort into our lives. Empathy is at the core of designing for uncertainty, so our design must show plenty of empathy and have the ability to do the elusive and manage to ‘warm the heart’.

There are broad thematic principles to consider during uncertain times. These could include the notion of solidarity in design that shows a clear sense of camaraderie, the kind of work that reassures us that ‘we’re all in this together’.

Then there’s distraction. There’s no harm in taking our minds off things for a while. We will look back at this time as one where our thumbs took the shape of whatever device we use to control Netflix and consume social feeds.

A third approach to design could be described as understated aspiration. Of course, we don’t want to see too much work that places beauty out of our reach, but we do want something to look forward to when times are less uncertain. This might be the toughest to approach with sensitivity, but it has the potential to be a rugged route, showing our

audiences that if we hang in there, a reward will be forthcoming.

There is always the get-out-of-jail-free card that’s designing for instant gratification. This is a bit of a cheat-card, but it can tide us over while we plan design that’s more forwardlooking and empathetic. After all, little bumps of gratification during our day can help stave off the anxiety and the uncertainty. This is design for concise time preference—it addresses the bit of our monkey brain that would like something to make us happy right now, even if we know it won’t last.

Then there’s design for longer time preference, the work that we produce with the intent of a longer consumption moment and a more prolonged sense of satisfaction with the consumer of our design. In effect, the world has slowed down; it has time to breathe. We are taking a break from a society that had reached a fever-pitch. That was rushing along at a pace that was the most

manic in human history. Depending on what your area of specialisation maybe, this might be the time to push for that project that expected a little more of your audience but would ultimately deliver more reward.

In general, this is a time to design for good— we ought to design with the future in mind, and we need to design with good intent. But we also need to design what’s relevant, timely, and useful. Design that serves an immediate purpose and that will vanish ones the times have changed is useful, but we can’t expect it to last. Beautiful face masks are a delightful way to distract us from the minor annoyance of wearing a mask, but we look forward to a time when we don’t have to think about them anymore.

However, those designing a better way to combine our living space with a functional working area will likely be remembered for a long time. Some shifts in the way we work. In the manner in which we interact, and in the way we regard the functional spaces we inhabit (home/office/retail/etc.) will last longer and, hopefully, form part of the fabric of the society we will come to regard as usual.

Let’s learn lessons from the past as we design a better future. I’m pretty sure that during WWII, there were plenty who wished the world would go back to what it was before the war. Looking back, it is pretty evident that the world could not and would not simply revert to a previous state. Retail environments have changed and will continue to do so, the way we interact indoors and shift to the outdoors will remain. We’re crafting new ways to be connected. We are revisiting education, workplaces, and commutes around this, and this is just a handful of examples of contextdriven design that’s being demanded on all fronts.

Let’s put design to good use. Whether the world acknowledges it or not, design has pulled us out of the toughest of times and has left beauty and functionality in its wake, creating movements that have defined the visual landscape of the times. This time around, the world is once again asking for certainty, functionality, and relevance. And once again, it is time for designers to step in and, in a distributed and cumulative way, save the planet.