RECONTEXTUALIZING SPATIAL NARRATIVES

Thesis Documentation

Bachelors of Architecture

2023-2024

School of Architecture

Virginia Tech

This thesis could not have been developed without the help of my advisor, parents, peers, friends, and family.

Thank you to my advisor, Aki Ishida for always pushing me further.

Thank you to my studio-mates and friends, Maya Smith, Holly McNielly and Nathan Brannon, for being a part of this journey.

And, thank you to the other architecture faculty and friends who have provided me with advice and motivation along the way including Henri DeHahn, Ron Daniel, and Jim Bassett.

In an era marked by social and spatial inequalities, architects possess a unique opportunity to channel social justice by facilitating conversations

and reflection through their work.

This thesis investigates the adaptive reuse of prisons, focusing on the challenge of preserving historical narratives while repurposing these spaces. The backdrop is the U.S. trend of declining incarceration

rates, which has led to a 25% reduction in the prison population over the past decade and the closure of many facilities. Through case studies, such as prisons transformed into community centers, museums, and luxury hotels, it evaluates how each

The research is influenced by Michel Foucault’s study of the evolution from physical to psychological methods of punishment, shaping the principles guiding the reuse of such buildings. Kingston Penitentiary in Ontario, which closed in 2013 due to multiple operational failures, serves as a case study for reimagining a space that once epitomized control and isolation. The proposed design transforms this historic site into

Memory does not equal preservation.

It implies a re-representation or understanding of the past, as memories constantly shift and change as one experiences life.

project handles or disregards its historical context. This analysis also introduces a discussion on how architecture can highlight and challenge the issues of control and inaccessibility traditionally associated with this building typology. In addressing these transformations, the study underscores the importance of sensitive design approaches that respect the architectural integrity and the sociohistorical significance of the sites.

a blend of educational and communal spaces, specifically incorporating a Montessori school and a public library. This transformation aims to replace isolation with integration, using architecture to foster community engagement and

learning, while provoking a critical examination of control and accessibility within these historically restrictive spaces. The integration of educational functions not only utilizes the existing architectural elements but also introduces a dynamic environment conducive to new modes of interaction and learning.

Historically, a palimpsest referred to a manuscript page, either from a scroll or a book, made of parchment or vellum, that had been written on, scraped off or washed to remove the original text, and used again for another document. The original content, however, is never fully able to be erased. This paradigm challenges ordinary narratives of history and instead embraces a more complex, layered understanding of people and place.

“Personal growth happens through change. What if to make things better, to enable people to cope creatively with the traumas of change, we have to make things more difficult, more risky, less secure?.“

This reimagining is particularly significant as it not only recasts the space’s function but also its narrative, from one of confinement to one of enlightenment and community support. The design respects the penitentiary’s original limestone structure while transforming the interiors to create “ghost cells”— open, accessible spaces that serve as reminders of the site’s past. Externally, the introduction of motifs resembling cell bars nods subtly to the building’s history, balancing preservation with innovation. The conversion of the surrounding walls into green, welcoming areas signifies a transformation from exclusion to inclusion, highlighting the potential of adaptive reuse to both conserve and reinterpret historical sites for community benefit.

Ultimately, this thesis advocates for a design philosophy that embodies a balance between remembering the past and embracing the future, urging architects to consider the profound impact of their work on societal narratives and community identity. By fostering an environment where historical awareness and future aspirations converge, the project serves as a model for how architecture can engage with and transform community spaces.

To begin, the research delves into the significant decrease in incarceration rates across the United States, highlighting a movement towards less punitive and more rehabilitative approaches in the criminal justice system. In 2021, the U.S. prison population was noted at 1,204,300, representing a 1% decrease from 2020 and a dramatic 25% decrease since 2011. This trend is underscored by decreases in 32 states, where proactive measures and the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic have accelerated the reduction in both jail and prison populations. 1

The relationship between declining incarceration rates and crime rates has also been noteworthy. For example, states like New York have seen significant reductions in their prison populations accompanied by drops in violent crime rates, challenging the traditional notion that higher incarceration rates are necessary for safety. New York, alongside California, has been at the forefront of this shift, both states having implemented extensive policy reforms and

showing some of the most significant decreases in incarceration numbers. These progressive states serve as models for how systemic changes can lead to substantial impacts on both social justice and public safety.

These demographic and policy shifts have led to the closure or repurposing of numerous correctional facilities, sparking debates on the best uses for these spaces. The broader movement toward reducing incarceration rates involves a blend of decarceration efforts and legislative reforms, aimed at adjusting sentencing practices and managing non-violent offenses more leniently. This context sets the stage for exploring architectural opportunities that align with societal trends and policy decisions, emphasizing the complex interplay between reducing incarceration rates and repurposing institutional spaces. 2

New York State Closed Prisons Since 2009

Punishment as a Public Spectacle in Historical Context

Punishment as an Abstraction in Historical Context

Before delving into the history of prisons, this thesis explores the evolution of punishment, heavily influenced by Michel Foucault’s seminal work, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Foucault’s analysis provides a critical framework for understanding how punitive practices have transitioned from public spectacles of torture and execution to more covert, psychological forms of discipline. Historically, punishment was not just about deterring crime but also served as a visceral display of authority and power, with public executions and corporal punishments being common. This form of punishment was designed not only to punish the offender but also to serve as a deterrent through public spectacle.

However, Foucault argues that in the 18th and 19th centuries, society shifted towards a system where punishment became less about physical pain and more about controlling the mind and behavior, reflecting a broader transformation in how power and discipline were exercised. This marked a move from overt, spectacular forms of punishment to ones that operate through surveillance and normalization, epitomized by the concept of the Panopticon—a theoretical design for a prison where inmates are constantly visible to a central watchtower, yet cannot see whether they are being watched. This architectural design ensures a state of conscious and permanent visibility that assures the automatic functioning of power. 3

Foucault uses the Panopticon as a metaphor to explore how disciplinary mechanisms operate in various institutions, such as schools, hospitals, and factories, embedding a subtle control over individuals’ everyday lives. By making inmates or subjects of surveillance always aware of their observability, the Panopticon creates a sense of permanent visibility that is crucial to the exercise of power. The genius of this architectural concept lies in its simplicity; the power to see without being seen multiplies the disciplinary effect while reducing the need for force.

Panopticon Diagram extracted from Michel Foucault Discipline and Punishment

This system of surveillance becomes a central theme in Foucault’s critique of modern societies. He suggests that such surveillance is not confined to penal institutions but is pervasive throughout society. Surveillance, according to Foucault, is the primary method of control in a disciplinary society, which extends beyond prisons and permeates various facets of social life. This concept of panopticism illustrates how modern societies implement control through “invisible” means, where the power to punish shifts from being public and direct to private and insidious, with surveillance becoming a fundamental tool of social control.

The transition to discipline through surveillance represents a significant evolution in the theory and practice of punishment. It shifts the focus from punishing the body to reforming the soul, where the ultimate goal is not just to prevent crime but to transform individuals into lawabiding citizens. The modern penal system, therefore, does not simply punish but seeks

to transform the soul of the prisoner through a calculated regime of observation and psychological pressure. 4

In this light, the thesis examines the historical shifts in penal philosophy and architecture influenced by Foucault’s ideas, exploring how these changes reflect broader societal transformations in the understanding and implementation of power and discipline. Through this lens, the transition from physical punishments to psychological strategies in the penal system is seen not merely as progress but as a complex reconfiguration of how society enforces norms and exercises control, often under the guise of rehabilitation and correction. This analysis sets the stage for a deeper discussion on how contemporary prison architectures can embody or resist these dynamics of visibility and surveillance, ultimately influencing the design and function of spaces intended for reform and punishment.

The history of prisons from the 12th century through the 1700s shows a significant evolution in the purposes and methods of incarceration, reflecting broader societal changes in views on punishment and reform. Initially, during medieval times, prisons were not primarily used for punishment but rather as holding facilities for individuals awaiting trial or execution. These early facilities were often part of existing structures like castle keeps or undercrofts in community buildings. Over time, the functions of these facilities expanded as local authorities sought more structured ways to deal with crime and punishment, often influenced by the fluctuating priorities of justice and public order.5

By the 1700s, the concept of using imprisonment as a form of punishment began to take a more defined shape, particularly influenced by philosophical and humanitarian advancements during the Enlightenment. This period saw the development of the “houses of correction” in England, which were institutions that aimed to reform petty criminals through hard labor and strict discipline. These ideas gradually spread to the American colonies, where they influenced the early development of the penal system. The correction houses, initially designed to instill discipline through labor, began to incorporate more elements aimed at rehabilitation, reflecting a shift from a purely punitive approach to one that included efforts to reform behavior.

In America, the late 18th and early 19th centuries marked a shift towards a more systematic use of prisons for reform, particularly under the influence of reformers who believed in rehabilitation through isolation, labor, and moral instruction. This period led to the establishment of the first state prisons which attempted to implement these new ideas about penology and correction. Notably, facilities like the Walnut Street Jail and later, the Auburn and Pennsylvania systems, reflected these evolving ideologies which emphasized not only punishment but also the potential for inmate rehabilitation. The architectural and operational refinements of these institutions aimed to enhance security while also facilitating the rehabilitative process, incorporating structured activities, and increasingly humane treatment of prisoners.

Throughout these changes, the architecture and management of prison facilities also evolved, with increasing focus on surveillance and control, yet with an underlying aim towards reforming the inmates rather than merely detaining them. This historical perspective sheds light on how deeply ingrained the philosophy of punishment and rehabilitation has been in the development of modern penal systems, and continues to influence contemporary discussions on the role and effectiveness of incarceration. 6

Exterior Site Photo of Kingston Penitentiary

Published by Queens University Canada. (2023)

Exterior Site Photo of Kingston Penitentiary

Published by Queens University Canada. (2023)

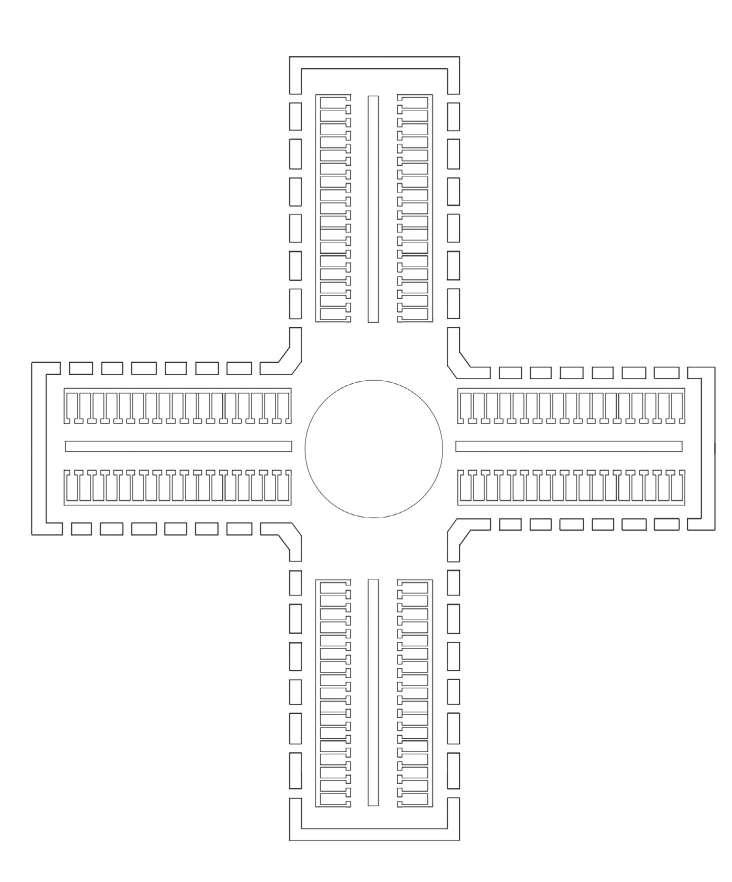

The cruciform typology in prison architecture is distinguished by its cross-shaped layout, where the main building splits into four arms radiating from a central core. This design is not only symbolic, reflecting Christian moral ideologies, but also practical in segregating inmates into manageable groups based on classification. The central observation area facilitates extensive oversight with minimal staff, allowing guards to monitor the wings from a single point. Architecturally, this typology often features grandiose designs with

In terms of wayfinding, the cruciform layout simplifies navigation due to its intuitive, symmetrical design. Each wing can be uniquely identified by its direction (north, south, east, west), which aids in quick orientation for both inmates and staff. However, this design can sometimes lead to inefficient circulation patterns, as movement between wings typically requires returning to the center. The separation and isolation inherent in the design also serve a disciplinary purpose, reinforcing the separation between different inmate populations and reducing interactions that could lead to conflict or unrest. 7

The cruciform typology utilizes a cross-shaped layout that facilitates centralized surveillance and embodies moral and disciplinary purposes with its distinctively religious architectural symbolism.

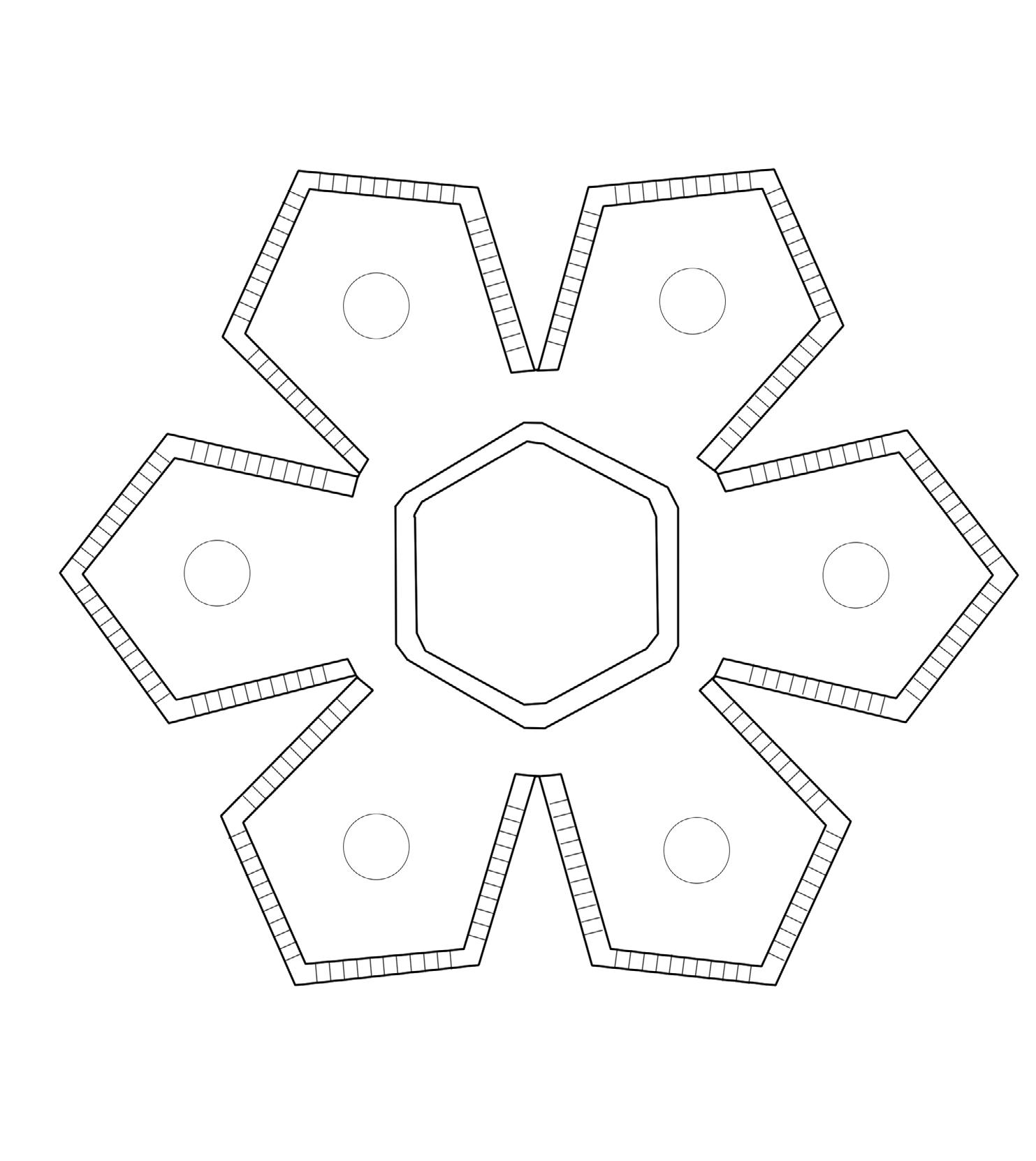

The octagonal prison design incorporates eight cell blocks radiating from a central surveillance hub. This structure optimizes the line of sight for prison staff, allowing them to observe all sections without blind spots. The octagonal design also maximizes the use of space, accommodating more cells within a compact area, which can be crucial in urban settings. The central hub is typically elevated, giving staff a commanding view of the entire facility, which is both a security measure and a psychological tool, as inmates are aware of the constant possibility of observation.

Wayfinding within an octagonal prison is facilitated by the geometric clarity of its design. Each segment or wing is directly accessible from the central hub, making the layout relatively easy to memorize and navigate. However, the complexity of having multiple wings can sometimes be confusing, particularly for new inmates and visitors. The octagonal shape also allows for more natural light to penetrate deeper into the facility, which can have positive effects on inmate mood and health, factors increasingly considered in modern prison design. 7

The octagonal prison design enhances surveillance capabilities through a central observation point surrounded by cell blocks arranged in an octagon, optimizing both security and space use.

Image of Millbank Prison, photographed from a balloon by Griffith Brewer in 1891, shortly before its demolition.

Image of Millbank Prison, photographed from a balloon by Griffith Brewer in 1891, shortly before its demolition.

Image of Presidio Modelo of 1931 Titled “Five Panopticons 2019.” Photographed by David Kutz

Image of Presidio Modelo of 1931 Titled “Five Panopticons 2019.” Photographed by David Kutz

The panopticon is a seminal design in prison architecture that focuses on maximum surveillance capabilities with minimal effort. The architectural form consists of a central watchtower surrounded by a circular arrangement of cells. This setup ensures that a single guard can observe all inmates, who cannot know when they are being watched, creating a constant sense of surveillance. The panopticon is highly efficient in terms of staff allocation and control, reducing the prison’s operational costs while maintaining high security.

The main elements of the panopticon include the central tower and the surrounding ring of cells, each designed for visibility from the center. Wayfinding in the panopticon is inherently limited, as inmates do not generally move freely. The layout emphasizes containment and oversight rather than mobility or interaction. Modern interpretations of the panopticon have sought to mitigate its psychologically harsh implications by integrating better living conditions and allowing for more humane inmate treatment while retaining its surveillance advantages. 7

Famous for its centralized surveillance potential, the panopticon allows a single watchman to observe all inmates from a central tower without them knowing whether they are being watched, emphasizing psychological control.

Radial prisons, featuring a central administrative area from which several housing wings radiate outward like spokes on a wheel, offer unique advantages in terms of control and operational efficiency. This layout is particularly effective in maximizing oversight while minimizing the required movement of guards. Each wing, extending from the core, can be seen from the central point, which houses the main control room. This centralized observation capability ensures that staff can quickly assess situations in multiple wings simultaneously, facilitating rapid response and communication.

The wings themselves are typically uniform in design, which simplifies construction and maintenance. This uniformity also extends to security measures, where each wing can be equipped with similar control mechanisms, making system-wide updates more feasible. The radial design also naturally segments the prison population, which can be strategically used to separate different groups based on criteria such as security level, behavior, and rehabilitation stage. This segregation helps in managing inmate dynamics and reducing conflicts. 7

The radial layout features a central hub from which prison wings radiate outward like spokes, facilitating efficient management and direct line-of-sight surveillance across the facility.

Inmates walk near the top of the Metropolitan Correctional Center on April 2012. Photographed by Antonio Perez / Chicago Tribune

Inmates walk near the top of the Metropolitan Correctional Center on April 2012. Photographed by Antonio Perez / Chicago Tribune

The triangle form in Chicago represents an innovative and contemporary approach to prison design, which integrates modern architectural principles with a focus on rehabilitation and social reintegration. This design uses a triangular layout to optimize the use of space, creating a more compact facility that allows for efficient management while reducing the physical footprint of the prison.

Architecturally, the triangle form facilitates enhanced surveillance with fewer blind spots due to the angular views provided by the triangular configuration. Each corner of the triangle can serve as a strategic point for security, allowing guards comprehensive visibility into the intersecting corridors. This layout also allows for the incorporation of more communal and rehabilitative spaces within the triangular sections, which are designed to be multifunctional, serving as areas for education, therapy, and social interaction.

From a wayfinding perspective, the triangle form offers an intuitive layout with three main sections that can be easily distinguished. 8

The triangle form is a modern approach that uses triangular layouts to improve space efficiency and sightlines for surveillance while fostering better communal spaces for rehabilitation.

The campus style prison typology represents a significant evolution in the design and philosophy of correctional facilities. This design paradigm is characterized by a decentralized layout that promotes a more open and less restrictive environment compared to traditional, highly fortified prison architectures. In a campus-style prison, buildings and facilities are spread out over a broad area, with separate structures dedicated to different functions such as housing, educational programs, vocational training, and recreational activities.

The aim of the campus style is to reduce the institutional feel typical of traditional prisons, thereby helping to normalize the environment for inmates. This normalization is crucial as it supports the rehabilitation process by providing inmates with a setting that resembles outside life and creates movement and social interaction within its boundaries, which can significantly improve mental health and enhance social skills. For instance, inmates might move between buildings for different activities, much like students or employees on a university or business campus, which can help mitigate feelings of confinement and isolation.

Educational and vocational training centers are central to the campus style, often featuring state-of-the-art technology and teaching resources that mirror those found in noncorrectional educational institutions. These facilities are designed to provide inmates with valuable skills and qualifications that can aid in their reintegration into society upon release. Recreational areas and green spaces are also integral to this prison model, offering inmates space for physical activity and relaxation, which are essential for mental and emotional well-being.

Overall, the campus style typology fosters a sense of community and personal development, which are key to reducing recidivism rates and encouraging positive behavior changes. By breaking away from the harsh confines of traditional prison designs and adopting a more humane and rehabilitative approach, the campus style sets a new standard for correctional facility architecture, reflecting a more enlightened and effective approach to dealing with crime and rehabilitation. 9

The campus style typology represents a shift towards a more humane and rehabilitative approach in prison architecture, featuring spread-out buildings that mimic a college campus, designed to foster education, personal growth, and better social interactions.

An artist’s rendering of the redesign for Las Colinas Detention and Re-Entry Facility in San Diego County, California. KMD Architects

An artist’s rendering of the redesign for Las Colinas Detention and Re-Entry Facility in San Diego County, California. KMD Architects

Inaccessible Typologies in Historical Context

Adaptive Reuse and Preserving History

Defensive typologies in prison architecture are fundamentally designed to enforce control and restrict accessibility, embodying principles that prioritize security and management over mobility and freedom. These architectural forms, such as the panopticon, radial, and telephone pole layouts, are meticulously planned to create environments where surveillance is maximized and inmate autonomy is minimized. The panopticon, for instance, is a prime example of architectural control, where its unique circular structure and central watchtower allow for continuous observation of inmates, reducing the need for a large number of guards while heightening the sense of being constantly watched. This design is not merely functional but psychological, reinforcing a power dynamic that emphasizes surveillance and the inaccessibility of private spaces for the inmates.

The radial and telephone pole designs further illustrate the concept of control through their strategic use of space and sightlines. Radial prisons, with their huband-spoke layout, enable guards to monitor multiple wings from a central location, effectively reducing the areas that are out of sight and thus harder to control. Similarly, the telephone pole design, with its long, straight corridors flanked by cells, simplifies the surveillance process by providing clear, unobstructed views down the length of the corridor. These designs are not just about observing the inmates but about managing their movements—limiting their ability to gather, interact, or attempt escape. Every aspect, from the width of the corridors to the placement of cell doors, is calculated to enhance control and limit inmate accessibility to one another and to parts of the facility without direct supervision.

Prison architecture is a complex discipline that melds security needs with the requirements of daily life behind bars. Central to this discipline are the cells, the fundamental units of inmate housing. Each cell is meticulously designed to maximize security while providing a minimal level of habitability. Constructed from reinforced materials such as steel and tamper-resistant alloys, these cells are engineered to prevent escape and ensure easy maintenance.

Within the larger framework of a prison, cells are grouped into cell blocks, which are crucial for organizational and management purposes. Cell blocks allow for the classification of inmates based on various criteria, including security level and behavioral history, which facilitates more tailored rehabilitation programs. This segmentation helps manage prison populations more effectively, ensuring that inmates with similar profiles are housed together, which can enhance safety and reduce incidents. 10

The design of cell blocks is influenced by the overall architectural style of the prison—whether it adopts a radial, panopticon, or other layout.

Each style impacts the daily operations and surveillance capabilities of the facility. For example, radial layouts allow guards stationed at a central hub to monitor multiple wings at once, enhancing control without necessitating a high number of on-foot patrols. This efficient use of human resources underscores the importance of architectural planning in prison management.

Connecting the network of cells and cell blocks are the corridors, the lifelines of any prison facility. These are not merely passageways but critical components of the prison’s security apparatus. Designed to be narrow and easily surveillance, corridors facilitate the movement of guards and restrict the flow of inmates, reducing the potential for unauthorized congregation and ensuring quick responses to emergencies. The strategic placement and construction of these corridors are essential for maintaining order and operational flow within the facility.

The architectural configuration of cell blocks and corridors can either positively or negatively influence the rehabilitative aspects of prison life. By designing these spaces to facilitate program delivery prisons have the potential to support inmate rehabilitation and prepare them for eventual reintegration into society.

Surveillance is further integrated into the design of corridors through the installation of cameras and one-way observation windows, allowing staff to monitor inmate activity without making their presence felt continuously. This subtle form of supervision helps maintain a balance between security and the oppressive feeling that can arise from overt surveillance, which is crucial for inmate mental health.

The interaction between cell blocks and corridors also has significant implications for social dynamics within the prison. The balance between security and socialization is a critical aspect of prison architecture, reflecting broader goals beyond mere containment. 11

Typically, a standard prison cell measures approximately 6 feet by 8 feet, with a ceiling height of around 9 feet. These dimensions provide just enough space for basic daily activities but are deliberately limited to reduce the comfort levels as a form of control. The spatial constraints are a fundamental aspect of the psychological environment in a correctional facility, designed to minimize privacy and maximize manageability.

Within these confined quarters, the layout and furnishing of a cell are meticulously planned to balance functionality with security. The cell generally contains a bed, which is often a single piece of molded concrete or a metal platform with a thin mattress, a toilet-sink combo made from stainless steel to prevent vandalism and facilitate easy cleaning, and a small table or shelf attached to the wall. Storage space is minimal, usually consisting of a small locker for personal items, reflecting the controlled environment where personal belongings are kept to a minimum.

Architecturally, one side of a prison cell typically features a window, which is usually narrow and placed high on the wall to prevent tampering and escape attempts while allowing natural light to enter. This window is often made of unbreakable glass or covered with heavy bars or mesh. The opposite side of the cell is usually composed of bars, allowing guards to observe the inmate without entering the cell. This design ensures continuous visibility and reinforces the power dynamics inherent in prison architecture, where surveillance is constant and privacy is almost non-existent.

Every aspect of the cell’s architecture is designed to withstand abuse, prevent damage, and discourage defacement, ensuring the facility remains secure and functional over time. These architectural choices not only reflect the priorities of security but also the underlying approach to penal philosophy that prioritizes containment and control over comfort. 12

Defensive architecture and more particularly, the use of solitary confinement, has profound psychological impacts on inmates, shaping their mental health and behavior in significant ways. The design of these facilities often prioritizes security over human needs, leading to environments that can be psychologically harsh and isolating.

Solitary confinement, a stark example of such architecture, involves placing inmates in a small, often windowless cell for 22 to 24 hours a day. This extreme isolation can lead to a range of negative psychological effects, including anxiety, depression, and a sense of disorientation in time and space.

The sensory deprivation that comes with solitary confinement exacerbates these issues. Human beings are inherently social creatures, and the lack of interaction can hinder psychological and emotional development. 13

Inmates in solitary confinement often experience a deterioration in social skills and may struggle with interpersonal interactions both during and after their incarceration. The absence of visual and auditory stimuli not only dulls the senses but can also lead to hallucinations and a decline in cognitive functions, making reintegration into society even more challenging.

The enforced idleness and lack of stimuli creates an environment where negative thoughts can fester, potentially leading to mental health crises. Inmates often report feelings of despair and hopelessness, which can escalate to suicidal ideation. The physical environment, characterized by stark, unadorned walls, and minimal outside contact, reinforces these feelings, embedding a sense of powerlessness and punishment that extends beyond physical confinement. 14

Defensive typologies in prison architecture not only impact the inmates contained within but also extend their influence to the broader society by enhancing the opacity of penal institutions. These architectural styles, designed primarily for security and control, inherently limit transparency, making it challenging for the public to understand or scrutinize what happens behind prison walls. This inaccessibility serves as a form of societal control, maintaining a barrier between the general public and the realities of life inside these facilities. By restricting access and visibility, prisons ensure that the daily operations and living conditions of inmates remain largely unseen and unexamined by those outside the system.

The design and placement of facilities like the panopticon, with its inward-facing structure, or the high walls and isolated locations common to many prisons, are not merely functional but symbolic. They represent a clear demarcation between the world of the incarcerated and the free, reinforcing a physical and psychological separation.

This architectural exclusion creates a disconnect in public perception, where prisons become abstract concepts rather than real institutions with daily impacts on human lives. Consequently, the lack of visibility and understanding can lead to public apathy or misconceptions about the penal system, undermining accountability and the push for humane treatment and reform.

This architectural control extends to the information that flows out of prisons. With media access severely limited by strict regulations and the physical barriers of the prison itself, the narrative about prison life and the state of penal institutions is often controlled by those in power. This control over information can lead to a sanitized or distorted public image of what incarceration entails, potentially skewing public policy and justice reforms. It can mask systemic issues such as overcrowding, inadequate healthcare, and abuse, delaying critical interventions and reforms needed to address these problems. 15

Adaptive reuse of historically charged spaces, such as prisons, raises complex ethical considerations. These structures often embody difficult histories, having served as sites of confinement and, at times, human rights abuses. Repurposing these spaces responsibly involves balancing the preservation of their historical integrity with the transformation into a space that serves contemporary societal needs. The ethical challenge lies in maintaining a respectful acknowledgment of the past while ensuring that the new use contributes positively to the community. It’s crucial that such projects do not erase or trivialize the often painful histories associated with these locations, but instead find ways to honor and remember them.

Preserving history while adapting old prisons into new uses can serve as a powerful reminder of societal progress and the shifts in our approach to justice and rehabilitation. These spaces can be transformed into educational centers, museums, or community hubs, providing the public with direct engagement with the past.

However, there is also a need to ensure that the adaptive reuse of prisons does not lead to commercialization that detracts from the gravity of what these buildings represent. Turning a former prison into a boutique hotel or entertainment venue, for example, could be seen as insensitive or disrespectful to those who suffered within its walls. It’s essential that redevelopment projects are led with sensitivity and involve stakeholders, including historians, local communities, and potentially even former inmates, to navigate the ethical landscape effectively.

Ultimately, adaptive reuse of charged spaces like prisons should strive to provide reparative benefits to society. This might include creating spaces that contribute to the healing of communities affected by the histories of these sites, such as offering community services, hosting social justice organizations, or creating memorial spaces that facilitate reflection and commemoration.

Constitution Hill in South Africa stands as a poignant example of adaptive reuse, where a former prison complex has been transformed into a museum and home to the country’s Constitutional Court. This site in Johannesburg has a deep historical significance, having once confined both ordinary criminals and political prisoners, including notable figures like Nelson Mandela and Mahatma Gandhi. Its conversion into a museum and a symbol of freedom is a powerful testament to South Africa’s tumultuous journey from a deeply segregated society to a democracy grounded in human rights and justice.

The transformation of Constitution Hill into a museum serves not only as a preservation of its grim past but also as an educational resource that promotes understanding and reflection about South Africa’s history. The museum offers visitors a stark glimpse into the lives of the prisoners once held there, displaying the harsh conditions, artifacts, and narratives that paint a vivid picture of what life was like under apartheid. This aspect of the adaptive reuse project is crucial in educating the public, particularly younger generations, about the struggles that shaped their nation, ensuring that the memories of those who suffered are neither forgotten nor repeated.

Beyond serving as a museum, Constitution Hill is also the site of the Constitutional Court of South Africa, the highest court in the country on constitutional matters. The decision to locate the court here is deeply symbolic and reflects a deliberate choice to transform a site of oppression into a beacon of justice. The court itself is architecturally integrated with the old prison complex, incorporating materials from demolished sections of the prison to preserve its historical essence. This integration serves as a poignant reminder of the site’s past while symbolizing the country’s commitment to justice and human rights. It is here where the nation’s most important legal decisions are made, under the shadow of a history that underscores the importance of protecting and valuing human dignity.

In addition to housing the Constitutional Court, Constitution Hill has become a vibrant cultural

hub and a venue for various events, discussions, and celebrations that engage both the local community and visitors. It hosts art exhibitions, performances, and civic engagements that repurpose the former prison’s space into one of inspiration and dialogue. This transformation showcases adaptive reuse at its best, where the site’s original purpose is reimagined to contribute to societal education and cultural enrichment. Through these events, Constitution Hill transcends its historical role as a place of confinement, redefining itself as a central stage for democracy and creativity in South Africa. 16

Constitution Hill’s role in the community extends to being a space for reflection and healing. Its ongoing programs and initiatives aim to address historical injustices by promoting reconciliation and understanding among South Africa’s diverse populations.

of Exterior Plan for The Women’s Building

Published by Maestrapeace Artwork Records

The Women’s Building in San Francisco is a striking example of adaptive reuse, where the former Women’s Building, initially constructed in 1910 as a women’s jail and later serving as a YWCA, has been transformed into a vibrant community center. This transformation is particularly poignant given its history of once confining women and now serving as a beacon for female empowerment and community service. The building, located in the Mission District, has become a hub of activity and support, offering a range of services that focus on the needs of women and girls, promoting gender equality and social justice.

Architecturally, The Women’s Building stands out with its vibrant murals that wrap around the exterior, symbolizing the freedom and creativity now thriving within its walls. These murals, known as the MaestraPeace Mural, were painted in 1994 by seven women artists and several

helpers, depicting famous women and feminine icons from history and mythology, reflecting the building’s mission to inspire and empower women. This colorful facade not only beautifies the neighborhood but also acts as a symbol of the building’s new role as a sanctuary and a place of inspiration for the local community.

Inside, The Women’s Building continues to embody its principles through its use. The center provides a variety of services such as low-cost office space for non-profits, conference and meeting rooms, and a community resource room. These facilities host over 170 womenfocused nonprofits that provide direct services to thousands of women and families. It is a place where women can find counseling, career guidance, health-related services, and legal assistance, all under one roof, supporting their personal growth and professional development.

The Women’s Building is not only a physical space but also a cultural and social one, actively engaging with the community through events and workshops that range from arts to human rights education. The center organizes celebrations, educational sessions, and cultural events that are open to the entire community but are particularly focused on uplifting women. By hosting such diverse activities, The Women’s Building ensures it remains a dynamic and inclusive environment, fostering a sense of community and mutual support among those who visit.

As a case study in adaptive reuse, The Women’s Building exemplifies how a space with a complex history can be reimagined and repurposed to serve a profoundly positive role in the community. This transformation from a women’s jail to a community center dedicated to women’s rights and community support stands as a testament to the power of architectural and social reinvention. It highlights the potential of adaptive reuse projects to not only preserve historical structures but also redefine their meanings and uses in ways that reflect and serve current community values and needs. 17

The Ottawa Jail Hostel, once the Carleton County Gaol, serves as a fascinating example of adaptive reuse, where a historical prison has been transformed into a unique accommodation experience for visitors. Originally constructed in 1862 and operational as a jail until 1972, this building witnessed the confinement of inmates under often harsh conditions. The transformation of such a space into a hostel preserves its stark history while repurposing it for modern use, thereby maintaining the architectural integrity and historical significance of the site.

The transformation process involved maintaining many of the original features of the jail to preserve its historical essence and authenticity for guests. Visitors can stay in converted cells that retain original elements such as iron bars and heavy metal doors, providing an immersive experience that starkly contrasts with typical lodging options. This direct encounter with history not only educates guests about past penal practices but also deepens their appreciation for the preservation of such sites. 18

The hostel offers a variety of accommodations, from traditional dormitory-style rooms in former inmate cells to more comfortable and modern rooms that were once guards’ quarters. The retention of the building’s original structure offers guests a unique glimpse into the day-to-day conditions that inmates faced, with some cells left in their original state as part of the hostel’s museum. This setup allows the hostel to operate as both a place of accommodation and a site of informal education, where the history of the penal system is both preserved and critically engaged with by visitors.

The Ottawa Jail Hostel organizes daily tours that delve into the history of the building and its inmates, highlighting significant events such as the aforementioned last public hanging. These tours are crucial in providing context to the guests’ stay, enriching their understanding of the site’s past and the broader history of justice and punishment in Canada.

This adaptive reuse offers a compelling example of how buildings with challenging pasts can be repurposed in imaginative and educative ways. This project not only conserves an architectural landmark but also transforms it into a vibrant part of the community that invites reflection, discussion, and discovery. 19

The success of the Hostel highlights the potential for other historical and decommissioned buildings to be creatively repurposed. The integration of history with modern functionality serves both as a cultural enrichment and as a means of sustainable development. By maintaining the jail’s original architecture and coupling it with contemporary hospitality services, the hostel serves as a model for balancing historical preservation with economic viability. As such, this adaptive reuse not only preserves the past but also breathes new life into it, allowing historical narratives to continue in a new and dynamic context.

The Liberty Hotel in Boston, Massachusetts, provides a striking example of adaptive reuse, where the former Charles Street Jail has been transformed into a luxury hotel. Originally constructed in 1851, the Charles Street Jail housed notorious criminals and was known for its grand, cruciform architectural style, complete with arched windows and a soaring central rotunda. However, due to overcrowding and inhumane conditions, the facility was closed in 1990 after a federal court ruling declared the conditions unconstitutional. Its transformation into The Liberty Hotel has since turned a place of incarceration into a space of opulence, blending rich history with high-end modern amenities.

The design strategy involved preserving much of the original structure, including the historic facade and parts of the interior such as wrought ironwork and the iconic rotunda. 20

Inside, the hotel capitalizes on its unique history with themed decor and a restaurant called “Clink”, which, retains some of the original jail cells as part of its seating area, complete with bars on the windows and doors, offering guests a dining experience amidst reminders of the building’s former use. These elements are designed to provide an edgy yet luxurious atmosphere that glamorizes and romanticizes the jail’s history.

However, the transformation of a former prison into a luxury hotel raises significant ethical questions, particularly concerning the glamorization of incarceration. While The Liberty Hotel offers a unique experience, it also commodifies a space that was once a site of suffering and deprivation. This glamorization can be seen as insensitive to those who experienced the harsh realities of life behind bars, potentially trivializing the serious issues associated with incarceration such as systemic injustice and human rights abuses.

By turning a former jail into a place of leisure and luxury, there is a risk of creating a narrative that disconnects from the historical truths of the space. While guests enjoy high-end amenities and themed entertainment, the deeper stories of those who lived and suffered within the walls may be overshadowed or overlooked. It is crucial for such projects to navigate these ethical waters carefully, ensuring that they respect the history and experiences associated with the site. 21

The Liberty Hotel exemplifies the complexities of adaptive reuse, particularly when converting spaces with challenging pasts like prisons. While it showcases how historical buildings can be preserved and given new life, it also highlights the delicate balance required to respect the past without oversimplifying or glamorizing it. The Liberty Hotel serves as a case study in the potential and pitfalls of transforming sites of incarceration into commercial spaces, reminding us of the need for sensitive and thoughtful approaches to adaptive reuse that honor history while looking to the future.

Adaptive reuse projects, particularly those involving historically charged sites like prisons, navigate complex terrain between erasure and remembrance. This delicate balance is crucial as it influences how history is preserved and communicated to future generations. When transforming these spaces, the question arises: how should the past be integrated into the new use in a way that honors and acknowledges historical truths without becoming overwhelmed by them?

The transformation of prisons into luxury hotels, for example, often raises ethical concerns regarding the potential erasure of painful histories. These projects may prioritize commercial success and aesthetic appeal, overshadowing the site’s historical narrative. This approach can lead to a form of historical amnesia, where the unpleasant realities of the past are glossed over or repackaged as novel experiences for guests. Such a disregard for the historical narrative may be viewed as unethical, especially if the original purpose and the stories of those impacted by the site are marginalized or romanticized in ways that trivialize their suffering.

On the other hand, converting a prison into a museum represents a form of adaptive reuse that directly engages with the site’s history. Museums dedicated to their former function as prisons explicitly preserve and interpret their past, educating the public about the social and historical contexts of incarceration. This approach ensures that the narrative remains present and impactful, allowing for a deeper public understanding of past injustices and fostering a collective memory that acknowledges historical realities.

However, the feasibility of turning every decommissioned prison into a museum is questionable due to practical considerations such as financial sustainability, relevance to the community, and the sheer number of such sites. Not every old prison holds enough historical significance or public interest to function effectively as a museum, making it necessary to find alternative ways to preserve historical narratives without relying solely on this model.

Thus, the challenge lies in finding innovative ways to balance the act of remembrance with adaptive reuse. This might involve integrating elements of the site’s history into the new design in subtle but meaningful ways. For example, architectural features of a former prison could be preserved and interpreted within a new context, perhaps as part of the hotel’s design or through informational displays that explain the significance of these features. Such strategies allow the site to retain a connection to its past without being solely defined by it.

There is a role for art and commemoration in striking a balance between erasure and remembrance. Art installations, commemorative plaques, or dedicated spaces within the redevelopment that tell the history of the site can create a bridge between the past and the present. These elements can enhance the educational aspect of any adaptive reuse project, providing visitors and users with insights into the site’s former function and its impact on society.

The incorporation of narrative-driven design elements can also play a crucial role in this balance. By designing spaces within the adaptive reuse project that tell stories—whether through guided tours that recount the history of the site, or through curated exhibits that display artifacts from the prison—developers can create a richer, more engaging experience. This approach ensures that while the building serves a new purpose, its historical essence is not only preserved but also celebrated, allowing for a respectful remembrance that educates and informs all who come into contact with the space.

Adaptive reuse of prisons into either luxury hotels or museums poses significant challenges and opportunities in terms of ethical responsibility and historical preservation. The key lies in thoughtful approaches that respect the site’s past, integrate historical elements in ways that enrich the new use, and create a space that remains connected to its historical roots while serving modern functions.

Playground Area of The Landschaftspark in Germany.

Landschaftspark Duisburg-Nord in Germany is an exemplary model of adaptive reuse that masterfully balances between erasure and remembrance, transforming a former industrial site into a public park while retaining its industrial heritage. The park, once home to the Thyssen steel mill in Duisburg-Meiderich, ceased operations in 1985. Instead of demolishing the vast industrial structures, the site was repurposed into a multifunctional park that integrates the historical architecture with green spaces and public amenities. This project highlights how industrial sites, often seen merely as eyesores or relics of environmental degradation, can be creatively reimagined to serve new, beneficial purposes without erasing their historical significance.

The design of Landschaftspark, led by landscape architect Peter Latz, is particularly noted for its sensitivity to the site’s industrial past. Instead of removing the remnants of the steel mill, the structures have been incorporated into the park’s landscape. 22

This multifunctional use not only revitalizes the area but also attracts visitors from beyond the local community, increasing awareness and appreciation of industrial history. The variety of recreational activities available ensures that the site remains relevant and valued, preventing it from becoming a static monument and instead transforming it into a living part of the city.

The success of Landschaftspark Duisburg-Nord in achieving a balance between erasure and remembrance offers valuable lessons for other adaptive reuse projects worldwide. It shows that historical sites can be repurposed in ways that add new value while honoring their past. Instead of erasing history, the park magnifies it, allowing new generations to interact with the past in meaningful ways. This project underscores the potential of adaptive reuse to foster a sustainable future through innovative design and thoughtful integration of historical elements, ensuring that history is preserved and celebrated as a central part of the community’s evolving narrative. 23

Site Photo of Zigzagging Extension to Jewish Memorial Museum in Berlin. Photo by Guenter Schneider

Site Photo of Zigzagging Extension to Jewish Memorial Museum in Berlin. Photo by Guenter Schneider

Architecture, by its very nature, serves as a profound medium for storytelling, capturing the essence of a society’s cultural, social, and historical narratives within its structures. More than just functional spaces, buildings and their designs often reflect the values, aspirations, and collective memories of the people who inhabit them. Through the strategic use of design, materials, and spatial organization, architects can tell stories that are as varied and dynamic as any written narrative.

The aesthetic choices made in architecture— from the grandiose of skyscrapers to the humble simplicity of residential homes— communicate different aspects of human experience. For instance, the Gothic arches and stained glass of medieval cathedrals convey spiritual aspirations and religious devotion, while the sleek, glass facades of modern skyscrapers reflect technological progress and the fast-paced nature of contemporary life. Each architectural style evolves from a context, serving as a physical manifestation of specific cultural periods and their underlying ideologies.

Architecture captures and preserves historical moments. Buildings can serve as enduring witnesses to the past, whether they are centuries-old castles still standing against the backdrop of modern cities or industrial mills that have been repurposed into loft apartments. These structures carry the imprints of the eras they have survived, each layer telling its own story of the past, from periods of prosperity to times of hardship. This historical storytelling not only informs but also connects current generations to their heritage, fostering a sense of continuity and identity.

Architecture also functions as a storyteller in the way it shapes human behavior and interactions. The design of a space can influence how people move, interact, and feel within it. For example, open-plan offices tell a story of collaboration and transparency, aiming to foster a sense of community and shared purpose among workers. In contrast, a labyrinthine museum layout might create a narrative of discovery and wonder, guiding visitors on a journey through different cultures and histories. The way spaces are crafted can significantly dictate the social narratives that unfold within them.

The power of architecture to tell stories is perhaps most evident in memorial and commemorative spaces. Monuments, memorials, and dedicated museums are designed to tell very specific narratives, often related to remembrance and reflection. These spaces are carefully crafted to evoke emotional responses and to honor historical figures, events, or cultural achievements. Through solemnity and symbolic design elements, these architectural works create lasting impressions on visitors, encapsulating the collective memories and shared grief or pride of a society.

In sum, architecture serves as a versatile and powerful tool for storytelling, capable of conveying complex narratives across time. It encapsulates human achievement, preserves our history, expresses cultural identity, advocates for environmental care, influences social interactions, and commemorates important events—all through the silent language of space and form.

The Jewish Museum in Berlin, designed by architect Daniel Libeskind, stands as a poignant example of how architecture can be used to tell powerful stories. Libeskind’s design does not simply house historical exhibits; it embodies the emotional and historical narrative of Jewish life in Germany, making the architecture itself a part of the storytelling process.

Libeskind’s architectural approach, known as “Between the Lines,” is a reflection of the disjointed history of Jewish Germans. The building’s zigzagging plan and its exterior, which is covered with a zinc facade and cut with slashes representing wounds, create a disorienting experience that mirrors the feelings of exile and dislocation that marked the Jewish experience in 20th-century Europe. The museum’s layout, with its angular walls and sharp corners, forces visitors to travel along jagged paths that abruptly end, symbolizing dead ends in history and the numerous disruptions in the life paths of many Jewish individuals.

Inside, the museum’s spaces are a testament to architectural storytelling. One of the most striking features is the Holocaust Tower, an empty 24-meter tall concrete silo, which visitors enter to experience a sense of isolation and echoing silence, interrupted only by a sliver of light from above. This stark, sensory experience evokes the terror and confinement felt by victims of the Holocaust. Another significant element is the Garden of Exile, where forty-nine concrete stelae are placed on a sloping ground, disorienting visitors and giving them a sense of the dislocation and instability felt by exiles.

Libeskind integrates voids throughout the structure, which are empty spaces that cut through the entire museum, inaccessible yet visible. These voids serve to represent the voids left in Jewish culture and history after the Holocaust. They are a narrative tool that makes the absence felt, a poignant reminder of the lives lost and the cultural void that those losses left behind. 24

Memory Void and Shalekhet Installation

Architecture, like art, holds the potential to provoke thought and stimulate public discourse, yet it often remains underutilized as a tool for sparking controversial conversations. Traditionally, architecture has been valued for its aesthetics and functionality rather than its capacity to engage with societal issues. However, as public art has demonstrated, integrating provocative themes and ideas into public spaces can profoundly impact social awareness and cultural dialogue. Architecture, therefore, has an untapped potential to not only house activities but to actively participate in and shape societal debates.

The role of architecture in evoking meaningful dialogue is exemplified by structures like the 9/11 Memorial, which, while primarily serving as a site of remembrance, also invites reflection on broader themes such as global politics, security, and human rights. However, the scope for architecture to initiate conversation should extend beyond memorials. Everyday buildings and public spaces can be designed to challenge societal norms, question prevailing practices, and stimulate debate on a range of contentious issues from environmental sustainability to social equity.

Consider, for example, an office building designed with entirely glass walls that not only use natural lighting but also act as a metaphor for transparency in corporate governance. Or imagine public housing that prioritizes shared spaces to promote community interactions, subtly advocating for a shift away from individualism towards a more collective living approach. These are not just design choices; they are ideological statements that invite debate and discussion about broader societal values.

Incorporating interactive elements that engage the public can transform buildings from static structures into dynamic spaces that encourage participation and dialogue. Facades that display real-time environmental data can provoke conversations about sustainability and climate change, while adaptable public spaces that change based on user interaction can challenge conventional notions of urban planning and community engagement.

The process of designing such spaces should itself be open and inclusive, involving community input not just at the planning stage but as an ongoing dialogue. This participatory approach ensures that the architecture not only serves but also evolves with its community, fostering a continuous exchange of ideas that can lead to a deeper understanding and re-evaluation of societal issues. Community workshops, feedback sessions, and interactive design charrettes can become routine parts of architectural practice, transforming the design process into a dialogue that values and integrates diverse perspectives. This can be particularly impactful in neighborhoods undergoing significant changes, where architecture can serve as a catalyst for involving residents in shaping the transformations that affect their daily lives and environments.

By embracing its role as a medium for social commentary, architecture can do more than house functions; it can inspire, challenge, and engage minds. It can transform everyday experiences into opportunities for reflection and debate, making every space a potential ground for learning and discussion. In this way, architecture can fulfill a critical role in shaping and reflecting societal values, much like the most compelling pieces of public art.

the Memorial

and

Exterior Photo of for Peace Justice. Photograph Published by Audra Melton / New York Times / Redux“Guided by Justice” statue located at the Memorial for Peace and Justice. Photograph published by Equal Justice Initiative, Montgomery, AL

National Lynching Memorial

The Memorial for Peace and Justice, located in Montgomery, Alabama, serves as a poignant example of how architecture can be used to prompt deep and meaningful conversations. This site is dedicated to the legacy of enslaved Black people, people terrorized by lynching, African Americans humiliated by racial segregation, and people of color burdened with contemporary presumptions of guilt and police violence. The design is both a memorial and a place of reflection on America’s history of racial inequality.

The structure comprises over 800 corten steel monuments, each representing a county in the United States where a racial lynching took place. These monuments are suspended from above, creating a powerful visual impact as visitors walk beneath them, confronting the scale and gravity of the racial terror inflicted upon African Americans. This physical arrangement invites visitors to engage with the history physically and emotionally, sparking conversations about the past and its continuing impact on the present. 25

The memorial’s design incorporates a narrative journey for visitors, beginning with sculptures that convey the brutality of slavery and racial segregation. As one progresses through the site, the path leads them through the monument field, and finally to a reflection space where names of known victims are commemorated. This journey is designed to evoke a range of emotions, facilitating a deeper understanding and awareness among visitors, which in turn promotes discussions on racial history, justice, and reconciliation. The space does not just recount history; it immerses visitors in the narrative, making the experience personal and evocative. 26

By creating a space that confronts visitors with harsh realities, the memorial serves as a catalyst for discussion and education and stands as a significant example of how thoughtful architectural design can engage public sentiment and stimulate critical conversations.

Kingston Penitentiary, one of Canada’s most notorious correctional facilities, has a storied history that spans from its opening in 1835 to its closure in 2013. Originally constructed to incarcerate individuals of all ages, including children as young as eight, the facility was a pioneer in the Canadian penal system, embodying the shift from punitive measures to a more reformative approach, though it often fell short of these ideals in practice.

The penitentiary was initially influenced by the Auburn system from the United States, which advocated for strict discipline, hard labor, and enforced silence, believed to foster repentance and moral improvement. However, the harsh implementation of these principles frequently resulted in punitive conditions rather than the intended rehabilitation, reflecting the complexities and challenges of enacting genuine reform within such institutions.

Throughout its nearly two centuries of operation, Kingston Penitentiary was the site of numerous riots, with one of the most significant occurring in 1971. This riot involved inmates taking control of the prison, resulting in a tense standoff that highlighted the dire conditions within the walls. The event drew national attention to the need for prison reform and spurred subsequent changes in inmate treatment and facility conditions, marking a shift towards policies that emphasized rehabilitation and humane treatment.

Despite these reforms, the facility continued to struggle with problems such as overcrowding, outdated infrastructure, and recurring violence. These persistent issues underscored the difficulties of managing a high-security prison and fueled ongoing debates about the efficacy and ethics of such establishments in modern correctional practice.

Inmates getting ready for a Sunday baseball game in the exercise yard in August 1954 used cigarette lighters to set buildings on fire. Published by Toronto Star (1954)

Entrance Photo of Kingston Penitentiary Published by Internet Archive Book Images. (1901)

The decision to close Kingston Penitentiary in 2013 was influenced by these factors, alongside the rising costs associated with maintaining and updating the facility. The closure was viewed by many as a progressive step towards a more humane and effective correctional system in Canada, one that prioritized rehabilitative over punitive approaches and sought to ensure better conditions for inmates.

In the years following its closure, Kingston Penitentiary has been transformed into a historical site that offers public tours, allowing visitors to explore its complex legacy. These tours do more than showcase the prison’s history; they provoke thoughtful discussion on the evolution of penal practices in Canada. They encourage reflection on how the justice system can better balance the goals of punishment and rehabilitation, and how historical insights might inform contemporary correctional strategies.

Additionally, the site serves as a poignant reminder of the ongoing challenges in the field of criminal justice. It sparks dialogue among policymakers, scholars, and the public about the future of incarceration, emphasizing the need for continued reform and innovation in the way society handles crime and rehabilitation. The lessons learned from Kingston Penitentiary’s long history are crucial in these discussions, offering both warnings and guidance for future corrections policy.

Though Kingston Penitentiary’s transformation into a museum and heritage site underscores the importance of preserving such historical institutions as educational resources, the tours are sparse and more can be done to preserve and convey the charged history. Kingston Penitentiary has the ability to contribute to a broader public understanding of penal history and its implications for current and future justice systems. 28

Exterior Site Photo of Kingston Penitentiary Published by Queens University Canada. (2023)

Kingston Penitentiary stands as a monumental example of historic prison architecture in Canada, showcasing distinct design choices that reflect its era and intended function. When it was constructed in 1835, the penitentiary’s architecture was heavily influenced by contemporary ideas about correctional facility design, which favored imposing structures meant to inspire both deterrence and reform through their sheer presence and rigor.

The building itself was primarily constructed using local limestone, giving it a robust and enduring quality. The use of this material not only made the structure formidable but also integrated it with the surrounding landscape of Kingston, Ontario, known for its abundant limestone quarries. This choice of material contributed to the penitentiary’s imposing appearance, with its thick, masonry walls serving both functional and symbolic purposes. These walls were intended to signify permanence and inescapability, underlining the institution’s role as a place of unyielding correction. 29

Architecturally, Kingston Penitentiary was designed with a panoptic structure, inspired by the principles of Jeremy Bentham’s Panopticon. The radial layout of the cell blocks allowed for a centralized observation point, a design choice that maximized surveillance capabilities. Guards could monitor inmates without the inmates knowing whether they were being watched at any given moment. This architectural feature was intended to control and modify inmate behavior through the omnipresent threat of surveillance, reinforcing discipline and order within the facility.

Inside, the penitentiary was organized meticulously. The interior layout included cell blocks arranged in long corridors with cells on either side, which maximized the use of space while allowing for efficient surveillance and control. Each cell was small and sparsely furnished, emphasizing the facility’s focus on punishment and penitence over comfort. Over the years, as the prison evolved, so did its interior structures, adapting to new penal philosophies and increasing demands for inmate rehabilitation and humane treatment.

The presence of the penitentiary on its site was commanding. Positioned on the shores of Lake Ontario, the institution was both isolated from and yet integral to the community of Kingston. Its location was strategically chosen to leverage the natural barriers provided by the lake, enhancing the security and isolation of the facility. The penitentiary’s architecture, with its crenelated battlements and arrow slit windows, borrowed elements from medieval fortresses, reinforcing its function as an impenetrable place of confinement. 30

Kingston Penitentiary, once one of Canada’s most notorious correctional facilities, provides a compelling study in the spatial experience of prison cells. Built in 1835 and operational until its closure in 2013, the architecture and design of its cells reflect the penal philosophies over nearly two centuries. Understanding the layout and sensory environment of these cells offers insights into the daily experiences and challenges faced by the inmates who lived within its walls.

The cells at Kingston Penitentiary were notoriously small, measuring roughly 8 by 5 feet. Originally designed to hold one person per cell, changes in prison population over time occasionally forced adjustments to this policy. The limited space was intentionally restrictive, reinforcing the principles of isolation that were believed to encourage repentance. The cramped quarters severely restricted inmates’ physical movement and personal privacy, contributing to an environment of control and suppression.

Materials used within the cells were stark and durable, reflecting the institution’s priorities of security and maintenance over comfort. The walls were typically made from limestone, a material chosen for its robustness and abundance in the local area. Floors were often bare concrete, and furniture was minimal and fixed to the floor or walls, including a metal bed, a small desk, and a toilet. The choice of these hard, unyielding materials made the cells not only austere but also acoustically harsh, as sounds echoed off the hard surfaces, amplifying the noises of the prison environment.

Lighting and ventilation in the cells were minimal, with small windows placed high up on the walls to prevent escape and reduce communication with the outside world. These windows provided little natural light, creating a dim environment that could contribute to psychological challenges such as depression or sensory deprivation. The lack of adequate fresh air circulation further compounded the discomfort, with the air quality often being poor and contributing to a sense of confinement and suffocation.

The acoustics of the cell environment at Kingston Penitentiary were also a significant aspect of the spatial experience. The sounds of the prison—keys clanging, doors slamming, shouts from inmates or commands from guards—were constant and pervasive. For many inmates, these sounds were a continuous reminder of their environment, providing neither solace nor escape from the reality of their imprisonment. This auditory experience played a critical role in the sensory world of the inmates, affecting their psychological state and sense of time.

Overall, the spatial experience of the cells at Kingston Penitentiary was designed to exert maximum control over the inmates, limiting physical and social interaction and minimizing distractions from the external world. The architecture of these cells—small, stark, and robust—was a physical manifestation of the penal philosophy of the era, emphasizing punishment and control.

Kingston Penitentiary’s cell blocks are emblematic of traditional penitentiary design, where the arrangement and structure of space are crucial to enforcing discipline and maintaining order. The spatial experience of navigating these cell blocks provides insights into the functional and psychological aspects designed to control and manage the inmate population effectively.

The architecture of the cell blocks was primarily dominated by long, narrow corridors flanked by rows of cell doors on either side. These corridors served as the main arteries of movement within the facility, designed to allow guards to monitor inmates efficiently and enforce the strict regulations of the penitentiary. The corridors’ length and narrowness enhanced the sense of confinement and control, visually emphasizing the strict order and hierarchy that governed the institution.

Flooring in these corridors was typically made of stone or concrete, materials chosen for their durability and ease of maintenance. The hard surfaces contributed to an environment where sound traveled quickly and easily, amplifying footsteps, voices, and other noises that constantly echoed throughout the space. This auditory characteristic of the corridors played a dual role; while it helped guards detect any unusual activities, it also added to the oppressive atmosphere felt by the inmates.

Lighting within the cell blocks was minimal, often provided by small windows placed high up on the walls or by artificial lights that gave off a harsh, industrial quality of illumination. The placement and quality of lighting were calculated to prevent any shadowy corners, ensuring that guards had unobstructed views along the entire length of the corridors. This continuous visibility was crucial for surveillance but also intensified the panoptic nature of the penitentiary, where inmates felt constantly watched.

The layout of the corridors also facilitated a regimented routine, where inmates moved in controlled flows from their cells to various parts of the prison for meals, yard time, or work assignments. The spatial design of these passageways meant that movements could be easily contained and directed, minimizing the opportunities for inmates to interact unsupervised or attempt breaches of security. This control over movement was fundamental to the penitentiary’s operation, reflecting the broader goal of imposing order and discipline.

Moreover, the aesthetic and functional aspects of the cell blocks at Kingston Penitentiary were a constant reminder of the institution’s authority and the inmates’ subjugation. The stark, unadorned appearance of these corridors, coupled with their surveillance-oriented design, reinforced the power dynamics within the penitentiary, underscoring the institution’s control over the inmates’ lives.

The design and use of the yard at Kingston Penitentiary, along with its unique internal courtyards, played a critical role in both the daily routines and overall control of the inmate population. These spaces, while providing necessary breaks from the confines of cell blocks, were meticulously crafted to maintain strict security and surveillance, reflecting the overarching goals of the institution.

Kingston Penitentiary’s main yard was an expansive outdoor area surrounded by the imposing limestone walls. This traditional yard was designed to serve as a recreational and social space for the inmates, but it was far from a place of leisure. High walls topped with barbed wire ensured security while allowing only limited views of the world outside, a constant reminder to the inmates of their isolation from society. The yard’s size enabled group activities and exercise, crucial for inmate health and morale, yet its layout and the omnipresent guard towers strategically placed around the perimeter made privacy impossible and supervision constant.