Clipping the Budget-Hawks Wings

Author: Jason Cannistraro ‘23

The Budget-Hawk

On a chilly autumn day in 1932, a crowd of Pittsburghers huddled together on Forbes Field as the Governor of New York, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, took to the stage in the midst of his first presidential campaign. Addressing the history of the US federal budget, Roosevelt described how the “apparent national income” skyrocketed from $35 billion annually in 1913 to $90 billion in 1928. Mindful of all the levels of government’s role in maintaining a balanced budget, Roosevelt attributed the reckless spending of “all three of our Governmental units,” being the federal, state, and local governments across the nation, to this increase in national income. To this point, he showed that the total spending of these “classes” rose from $3 billion to almost $13 billion or from 8.5% of the national income, to 14.5%.1 Roosevelt accredited the rising federal budget deficit to that which he called governmental “extravagance” or ine cacy in conducting itself on a yearly basis. He stated that “there can be no extravagance when starvation is in question.” The main problems with “extravagance,” as Roosevelt saw it, were twofold: American citizens cannot carry the “excessive burdens of taxation,” and secondly, the government’s “credit structure” is damaged because of the “unorthodox financing” brought on by huge deficits. These ideas were supported when the government absorbed a billion-dollar deficit in 1931 and credit became harder to obtain, forcing banks to absorb the shortages and therefore lose resources.2

Roosevelt further expressed his belief that he had a path forward to reach a balanced budget to the Pittsburgh crowd. “The one sound foundation of permanent economic recovery,” he exclaimed to the masses, was a balanced budget. The first step was to “reduce expense” by the federal government in all aspects.3 Standing on behalf of his party and platform, Roosevelt pledged to lessen the financial burden of all current “operations” of

the government by 25%, if elected.4

FDR continued this ethos when nominated as the democratic candidate for president. In Chicago Illinois, 1932, before the democratic national convention, FDR gave his acceptance speech, having been elected the democratic nominee. While covering many topics, Roosevelt put emphasis on taxes, claiming that he “knows something about taxes.”5 He described his e orts campaigning across the country “preaching that government –federal and state and local – costs too much.”6 Furthermore, he stated his intentions as president, provided he be elected to the oval o ce. Roosevelt maintained that “as an immediate program of action we must abolish useless o ces. We must eliminate actual prefunctions of government... we must... give up luxuries which we can no longer a ord.”7

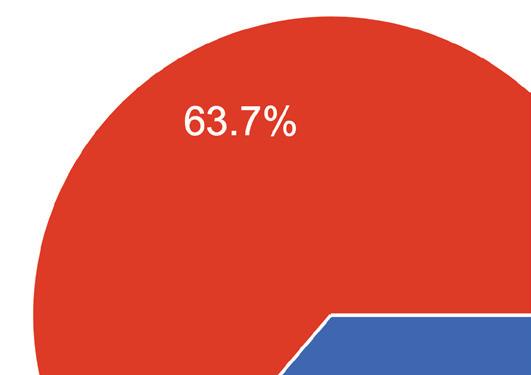

In spite of his budget-balancing beliefs, FDR became a prolific spender when faced with the Great Depression. His plan for saving the country from economic turmoil: the New Deal, used vast amounts of federal funds in the formation and funding of its various agencies. Costing $41.7 billion, or $653 billion in today’s dollars, the New Deal became the most expensive stimulus program in the nation’s history. The New Deal furthermore cost approximately 40% of America’s output, and the increase of federal debt between 1931-1938 as a fraction of GNP (gross national product) was a whopping 30.3%.8 Roosevelt’s reputation became that of reckless spending, as one political cartoon titled “Old Reliable!” depicted the president as a magician pulling a rabbit labeled “spending” out of a hat, claiming: “this is one rabbit that never failed me!”9

Despite being a fiscal conservative, FDR embraced deficit spending because of his views on the social duty of government and the recession of 1937. FDR unequivocally believed that the role of government was to help its citizens in need. Instituting programs which reflected this belief, FDR aided Americans unemployed from the Great Depression. The Roosevelt Recession cemented FDR’s

Volume VIII • Edition I May 2023 14

deficit spending policy. Referred to derisively as the Roosevelt Recession, when Roosevelt attempted to revert to his budget-balancing beliefs, a recession nearly as bad as 1929 followed. This led the president to completely abandon his hopes of a balanced budget and follow a deficit-spending program. Ultimately Roosevelt’s evolution from budget hawk to deficit spender relied on both his moral beliefs and the consequences of contractionary policy.

Business as Usual

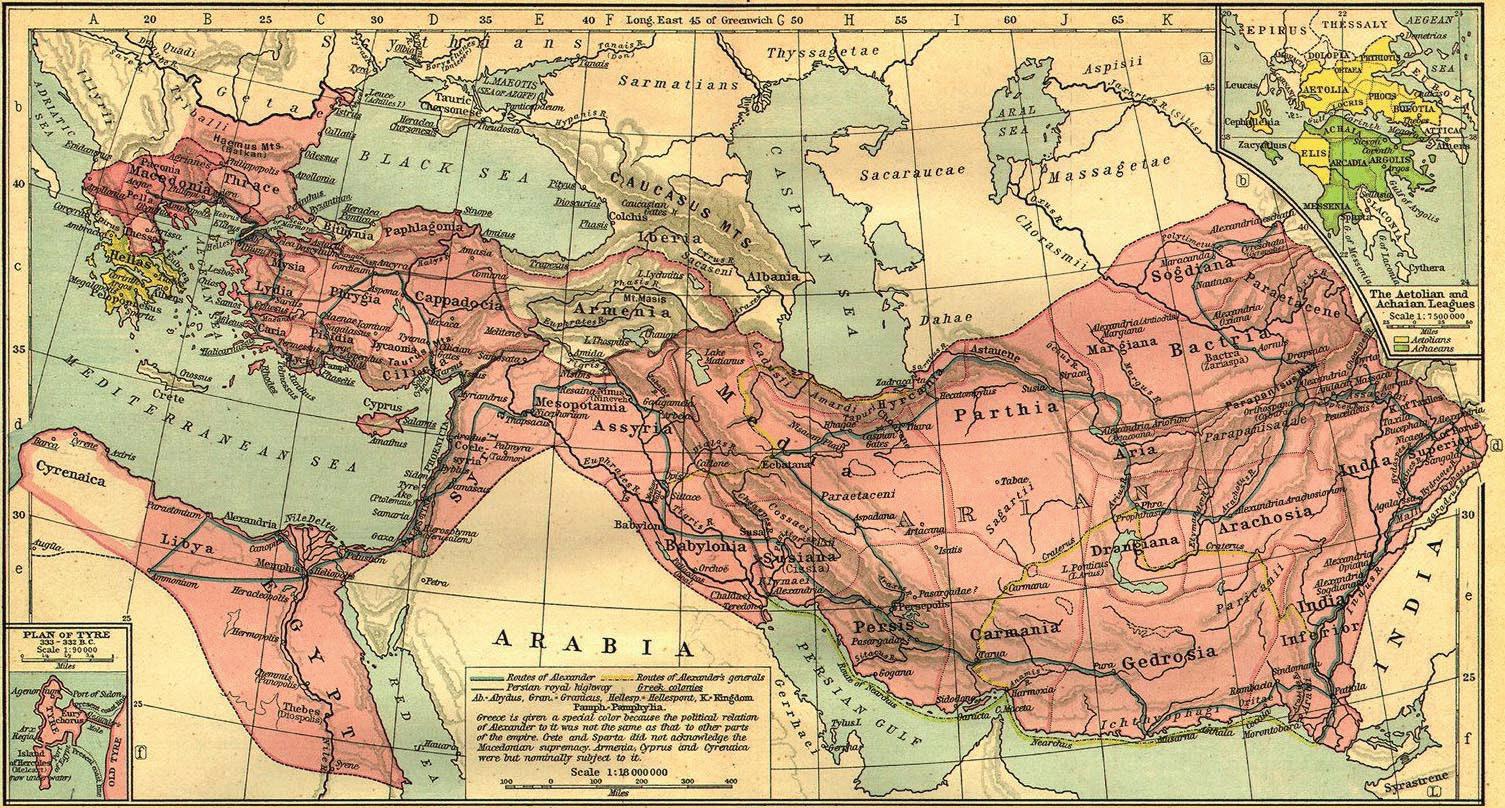

FDR’s speeches in Pittsburgh and Chicago reflect America’s traditional economic policy, favoring business and geared around market forces. In the early Republic, Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton’s financial plan supported the rise of business. Armed with the first tari in the nation’s history, the Tari Act of 1789, and a light excise tax on a few goods to boost federal funds, Hamilton sought to finance his capstone: a national bank. This entity would print paper money when necessary and act as a legitimate bank, supporting the rise of business by supplying a stable currency and providing loans.10 As the nation expanded westward in the mid-1800s, the federal government allowed “wildcat banks,” or unregulated state-chartered lenders, to spring up. These bodies allowed profiteering entrepreneurs to turn a hefty profit with no governmental obstacles. Later, the emergence of subsidized railroads propelled the nation into a new realm of industrialization and urbanization aptly named the “Gilded Age” for its rampant inequality.11

Despite the obvious consequences of unregulated capitalism, government regulation lagged behind. This notion was demonstrated by the first regulatory body, the Interstate Commerce Commission of 1887, which, designed to combat high rates of railroads and government corruption, became highly

ine ective due to its vague language demanding “just and reasonable” rates.12 It was not even until 1913 that President William H. Taft established a federal income tax, a burden which most Americans initially refused to carry, as only 2% of American households paid the tax for the first few years after its creation.13 Even in the face of recession, presidential administrations have historically been stubbornly conservative, withholding federal action and allowing the market to correct itself. Andrew Jackson’s response to the Panic of 1837 began this tradition. In 1832, Jackson withdrew $10 million of federal funds from the Bank of the United States and placed these in state and private banks. This sparked large economic growth coupled with inflation, as banks began printing currency to loan. As a result of this inflation, the national currency depreciated, and runs on the bank ensued as citizens rushed to save their savings. Jackson’s administration did nothing to aid the citizens, despite many losing their life savings, waiting in breadlines for morsels of food.14

Grover Cleveland continued this trend with his lack of response to the Panic of 1893. When America’s gold reserves fell to $100 million to $190 million in 1890 following a slow period of economic growth, many were concerned for the safety of their banknotes, taking them out of the bank and converting them into gold. As withdrawals increased in number, fear and panic spread. Bank runs once again pervaded the country, forcing 440 banks to fail from June-August. Despite proposals from the American Bankers Association, the secretary of the Treasury, and the comptroller of currency, Congress and President Grover Cleveland refused to act. It was not until gold influxes from Europe lowered interest rates that banks resumed operations.15

The traditional American values of laissez-faire carried over into the

Volume VIII • Edition I May 2023 The Podium | Research Papers 15

1920s. At the height of this era of low taxes and industrial expansion stood President Calvin Coolidge and his Secretary of the Treasury Andrew Mellon. So strong was Mellon’s presence in the White House that William Allen White, author/editor, and leader of the progressive movement, deemed the administration the “reign of Coolidge and Mellon.”16 Coolidge-Mellon policies followed a straightforward recipe for a healthy economy: deregulation of business, government spending reduction, tax, and debt cuts.17

Coolidge believed in traditional American laissez-faire values benefiting business. In his Inaugural Address, on March 4th, 1925, Coolidge expressed his belief that taxes were a tool to be used to allow business to flourish. He a rmed that “The method of raising revenue ought not to impede the transaction of business; it ought to encourage it.”18 Coolidge continued to demonstrate his pro-business ideology in a speech before the Chamber of Commerce. He explained that: “It is the important and righteous position that business holds in relation to life which gives warrant to the great interest which the National Government constantly exercises for the promotion of its success.”19

Analogous to President Coolidge, Secretary of the Treasury Andrew Mellon unequivocally believed in a low tax system. Following his Commander-in-Chief’s beliefs on the “constructive economy,” Coolidge’s term to describe an economy with a more e cient government under the principle of reduced spending, Mellon believed that low tax rates stimulate business and bring in higher revenue.20 Using American history as his tool, Mellon claimed that the American people do not pay “inherently excessive” tax rates, forcing businessmen to invest their money into “tax-exempt securities,” rather than their own “productive businesses,” slowing down the market’s gears.21 A low-income tax, however, eradicates the incentive to avoid taxes and motivates productivity. These tax cuts rested upon the foundation of a budget surplus formed by a lowering of governmental expenditures. The maintenance of this low tax system within a constructive economy,

Mellon believed, would create widespread prosperity and job opportunities. He wrote in his novel, Taxation: The People’s Business, that “If a sound system of taxation is adopted and the present policy of economy in government is continued, the country may look forward during the present generation not only to a decrease in the tax burden but to increased prosperity in which everyone will share.”22

Acting on these beliefs, Coolidge and Mellon instituted large tax cuts throughout their time in power to balance the federal budget. Coming out of World War I, the tax rate for income over $1 million sat at a lofty 77%. When Coolidge was elected in 1923, he worked to reduce these rates with the Revenue Act of 1924, bringing the top income tax rate to 46% for incomes over $500,000. Only two years later Coolidge and Mellon promoted the Revenue Act of 1926, firmly placing the top income tax rate to 25% for incomes over $100,000. As a result of these drastic measures, the federal debt and budget improved. When Coolidge left o ce in 1929, the national debt had been lowered to $16.9 billion from $22.3 billion in 1923. Furthermore, the federal budget had been reduced to $3.3 billion from $5.1 billion in 1921.23

A decade of strong economic growth followed Mellon and Coolidge’s tax cuts. In the eight years from August 1921 - September 1929, The Dow Jones Industrial Average rose 6 times over, peaking at 381 on September 3.24 Such prosperity captivated the nation and generated incredible optimism, leading economist Irving Fisher to denote the inflated stocks as at a “permanently high plateau.”25 Unemployment was low and new markets such as the automobile industry exploded with vigor, bringing innovative technology to everyday citizens. Working class laborers of these industries became investors in stocks that just simply kept rising.26

Following a decade of economic expansion, catastrophe set in on Wall Street. On Thursday, October 24, 1929, the very same year Coolidge had left the oval o ce, Wall Street traded a record 12.9 million shares as panicked investors scrambled to salvage what little savings they had. Four days later, on

Volume VIII • Edition I May 2023 16

Monday October 28, the Dow Jones Industrial Average plummeted 13%, and another 12% the following day.27 These drops became known as the Stock Market Crash of 1929, resulting in the greatest economic downturn in American History, with unemployment reaching record heights, and a Gross National Product which remained below pre-contraction levels for eleven years.28 Friedman and Anna Schwartz wrote in their universally acclaimed Monetary History of the United States: “The contraction from 1929 to 1933 may well have been the most severe in the whole of U.S. history.”29 Investor overconfidence and the actions of the Federal Reserve caused the Stock Market Crash of 1929. As stocks rose, confidence in the market grew, and banks became increasingly lenient with their lending practices. Buying on margin allowed everyday workers to play the stock game. They paid as little as 10% of the cost of the stock and borrowed the rest from a bank or broker, with the only collateral being the stock itself.30 From the years 19221929, the stock market increased 20% annually as easy credit allowed for prolific stock purchasing from all socio-economic statuses. Yet due to the ability of financially inexperienced citizens to invest, a societal overconfidence in the market to grow, an increasing amount of borrowed money became recklessly invested.31 In August 1929, the New York Federal Reserve Bank raised interest rates from 5% to 6%, cooling investor enthusiasm.32 When some stocks failed, the value of the collateral went down as well, forcing banks to make “margin calls,” or a request for an investor to pay back the loan immediately or add more collateral, to make up their losses.33 Scrambling to find money to fulfill these margin calls, investors sold their stocks, causing the stock prices to fall, and inevitably forcing banks to make more margin calls. When customers were unable to pay back their margin call, defaults, or failure to pay back a loan, skyrocketed, and the American public blamed the banks. At this time bank deposits were uninsured, forcing banks to follow a “first come first serve” policy in which only the first investors to make it to the bank were able to successfully save their money. As the public became aware of the possibility that

they may not be able to retrieve their money, runs on the bank became commonplace and mobs demanding the return of their deposits surrounded banks across the nation.34

The Great Depression brought incredible poverty and struggle to the American people. As businesses continued to fail, by 1932, 1 of 4 workers were unemployed.35 Exacerbating the burden of joblessness, bank shutdowns lost thousands of Americans’ life savings. Swarms of these Americans, forced to leave their houses, congregated in small cardboard house communities. Those younger and able to travel roamed the country, stealing rides on boxcars in search of any kind of work. Public morale disintegrated as mobs of citizens blamed bankers, speculators, and the government for this catastrophe which seemed to happen out of nowhere.36 The poor raided food stores and protested in the streets. When 5,000 veterans protested in the capital, in 1932, President Hoover forcefully broke up the crowd using the military, led by General Douglas MacArthur and Major Dwight Eisenhower.37 One onlooker described the brutality, stating:

“The police encircled them. A man was killed and another seriously wounded….To my right… military units were being formed….A squadron of cavalry was in front of this army column. Then, some sta cars, and four trucks with baby tanks on them, stopped near the camp. They let the ramps down and the baby tanks rolled out into the street….The 12th Infantry was in full battle dress. Each had a gas mask and his belt was full of tear gas bombs….They fixed their bayonets and also fixed the gas masks over their faces. At orders, they brought their bayonets at thrust and moved in.” 38

President Herbert Hoover embodied the US traditional response to depressions. Keeping in line with the philosophy of limited government, Hoover initially refused to give out “handouts,” a form of direct governmental aid. In the spirit of “rugged individualism” Hoover encouraged the American people to make do with the temporary struggle, as he proclaimed that “the worst is behind us.”39 Refusing regulatory action, Hoover summoned the nation’s leading capitalists to the White House, asking them to keep their current wages and promising that the recent crash was not a part of a

Volume VIII • Edition I May 2023 17

larger economic downturn.40 A president so disliked for his lack of aid, those small shantytowns filled with destitute citizens were derisively labeled “Hoovervilles.”41

Despite Congress’s attempts to introduce relief bills, Hoover stood fast, refusing to allow these programs to arise. In 1930-31, a $60 million bill formed to aid drought victims with federally provided food, fertilizer, and animal feed passed through Congress and awaited presidential enactment. Refusing to sign the bill in as it was, Hoover slashed the bill to $47 million, removing all the food components and making it inadequate in dealing with the crisis. Not to be deterred, Congress attempted direct relief again with the Federal Emergency Relief Bill, intending to provide $375 million for states to supply food and shelter for the homeless. Once again Hoover refused, citing the balance of power between the states and federal government, and the bill failed to pass.42

In dealing with this depression of epic proportions, not everyone believed in the recovery of the market. The gem of Cambridge University, John Maynard Keynes’ views on economics revolutionized economic thought. With belief in himself, if not anyone else, Keynes, having scored the lowest score for economics of all examinees on the British civil entrance exam, claimed: “‘I evidently knew more about economics than my examiners.”43 Refusing to let contemporary thought in the belief of free markets contain him, Keynes criticized the popular conventional ideas perpetuated by economists, considering the Great Depression. Keynes rejected the notion of the self-righting market, believing that a government must grow its way out of depression, rather than cut.44 Pre-Keynesian economists thought that changes in societal demand led to temporary unemployment as the market adjusted itself. Their logic followed the concept that low wages, in the times of a recession, led to less jobs, raising the demand for labor, which then brought wages back up to the previous level, if not higher.45 Keynes, however, believed that after a big market shock, such as a collapse in investment, the economy will continue to shrink until it reaches a stability

at a lower level, named the “unemployment equilibrium.” Economic output and employment depended on spending power, or “aggregate demand.” Therefore, in a decrease of societal spending, output and unemployment will fall subsequently. To prevent this course of events, the government must spend to counter the public deficit, no matter the cost.46 To fund these government expenditures, Keynes prescribed the use of “open-market operations,” or the process of central bank buying or selling securities in the market.47

As Roosevelt entered the oval o ce in 1933, he found himself between two contrasting ideologies on dealing with the depression. Strongly on one side of the spectrum, FDR continued the traditional conservative mindset towards the economy in the beginning of his presidency. Like his predecessors, FDR valued a balanced budget for its contributions to business and investment. Healthy business was a prerequisite for a healthy economy, and Roosevelt regarded a balanced budget as “the most direct and e ective contribution” to business the Government could produce.48 On March 10, 1933, Roosevelt addressed the government, inaugurated only a few months prior, stating that the government was “on road to bankruptcy” for the past three years under the presidency of Herbert Hoover, and that federal deficits had caused unemployment and stagnation.49 He furthermore described the federal government’s “not in order,” warning his colleagues: “Too often in recent history liberal governments have been wrecked on the rocks of loose fiscal policy. We must avoid this danger.”50 Reflecting this ethos, Roosevelt’s first legislation ever passed was the Economy Act of 1933, reducing federal expenditures by $500 million and broadening executive power to make budget cuts in his administration. Finally it became time for FDR to address the strife of the Great Depression with his New Deal.

The Moral Man

Faced with a time of incredible human su ering, Roosevelt embraced deficit spending because he unequivocally believed that the duty of government was to provide for its

Volume VIII • Edition I May 2023 18

citizens in times of need.

FDR expressed his conviction of the social duty of government even before obtaining the presidency. As a governor in New York, FDR addressed the legislature in 1931, rhetorically questioning the very role of the State. He answered that it had a responsibility to its citizens a ected by external circumstances. He claimed that “one of the duties of the State is that of caring for those of its citizens who find themselves the victims of such adverse circumstances as make them unable to obtain even the necessities of mere existence without the aid of others.”51 Roosevelt continued these sentiments on the campaign trail for president. On one radio address in Albany, New York, FDR commentated on unemployment and the government’s role in alleviating it. He maintained that “modern society, acting through its Government, owes the definite obligation to prevent the starvation or the dire want of any of its fellow men and women who try to maintain themselves but cannot. To these unfortunate citizens aid must be extended by the Government — not as a matter of charity, but as a matter of social duty.”52

Once elected president, FDR continued to express his belief that the duty of government was to aid its needy citizenry. Roosevelt’s inaugural address on March 4th, 1933, reflected this ideal. Roosevelt designated the “greatest primary task” of the nation to be “to put people back to work.” This duty he claimed could “be accomplished in part by direct recruiting by the Government itself, treating the task as we would treat the emergency of a war.”53 Eight weeks later, May 7th, 1933, FDR announced his plans for continuing to relieve the su ering felt by a ected citizens. He emphatically stated that ”our next step in seeking immediate relief is a grant of half a billion dollars to help the states, counties and municipalities in their duty to care for those who need direct and immediate relief.”54

In the same style, FDR addressed the nation again on June 28th, 1934, exhibiting his moral beliefs on government’s duty. He claimed that ”the primary concern of any Government dominated by the humane ideals of democracy is the simple principle that

in a land of vast resources no one should be permitted to starve.”55 FDR continued these sentiments in another fireside chat three months later, in which he justified government expenditures for the creation of jobs for unemployed citizens. Roosevelt stated that ”I answer that no country, however rich, can afford the waste of its human resources. Demoralization caused by vast unemployment is our greatest extravagance. Morally, it is the greatest menace to our social order.”56 Pushing this ethos further, three days before the election of 1936, FDR spoke at Madison Square Garden, defending his government and reminding his citizens of its moral standing. He a rmed to the American people that ”your Government is still on the same side of the street with the Good Samaritan and not with those who pass by on the other side.”57

FDR enacted policies reflecting this belief on the social duty of government to aid the needy citizenry. Based on the three “R’s,” relief, recovery, and reform, FDR sought to immediately address the impact of the Great Depression, and to prevent another recession of that magnitude. On March 31, 1933, Congress passed Roosevelt’s Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), providing employment to over 3,000,000 men, undertaking manual labor from reforestation to swamp drainage.58 In his second Fireside Chat to the nation on May 7th, 1933, Roosevelt commented on the success of the government so far in the creation of this agency which relieved “an appreciable amount of actual distress.”59 Establishing the Civil Works Administration (CWA) on November 8th, 1933, Roosevelt attempted to relieve joblessness by providing temporary jobs during the winter months, funded by the federal government. The CWA used and received $400 million from the Public Works Administration, Roosevelt’s public works construction agency, and $345 million from a Congressional grant.60 At a Civil Works Administration meeting, on November 15th, 1933, Roosevelt encouraged the audience that their e orts will alleviate the misery of the masses. He declared that he was “very confident that the mere fact of giving real wages to 4,000,000 Americans who are today not getting wages is going to do

Volume VIII • Edition I May 2023 19

more to relieve su ering and to lift the morale of the Nation than anything that has ever been undertaken before.”61 In terms of expansionary policy, however, both programs paled in comparison to Roosevelt’s Work Progress Administration, established on May 6th, 1935. Under the leadership of Roosevelt’s trusted advisor Harry Hopkins, his body spent $11 billion on public infrastructure and provided almost 9 million jobs.62

FDR defended this loose fiscal policy, citing the responsibility of both the President and the Federal government to aid those citizens in need. At the very same field he had spoken four years prior, FDR spoke in Pittsburgh, 1936, reflecting on his few years of presidency. Addressing the criticism of his failure to balance the budget despite his previously expressed intentions, FDR fired back, insisting that it “would have been a crime against the American people,” to do so from 1933-1935. He reminded the people that budget-balancing would rely upon a levy of America’s capital, or to ignore the su ering of citizens. Roosevelt emphatically declared that “humanity came first,” placing his economic views on hold.63 In front of Congress at the State of the Union FDR similarly defended his programs against harassing budget-balancers, as he argued that proponents of reducing government expenditures could not decide which programs to eliminate, rather just complaining about the principle. He revealed that “to many who have pleaded with me for an immediate balancing of the budget, by a sharp curtailment or even elimination of government functions, I have asked the question: What present expenditures would you reduce or eliminate? And the invariable answer has been ‘that is not my business -- I know nothing of the details, but I am sure that it could be done.’ That is not what you or I would call helpful citizenship.”64

Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s morality motivated him to use federal funds to aid his destitute citizenry. Ultimately FDR’s own sense of right and wrong outweighed his personal political and economic beliefs and led him to embrace deficit spending.

Receding Roosevelt

In addition to his moral motivations, the failure of the Roosevelt Recession cemented FDR’s deficit spending policies. The catastrophe which followed the contractionary policy of 1937 forced Roosevelt to abandon hopes of balancing the federal budget and embrace a budget-deficit spending program.

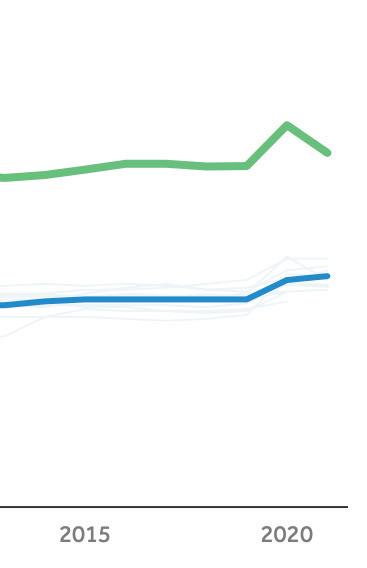

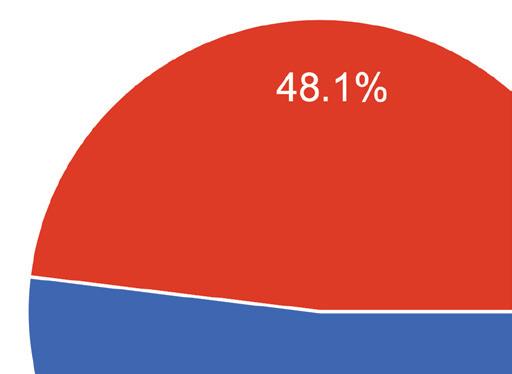

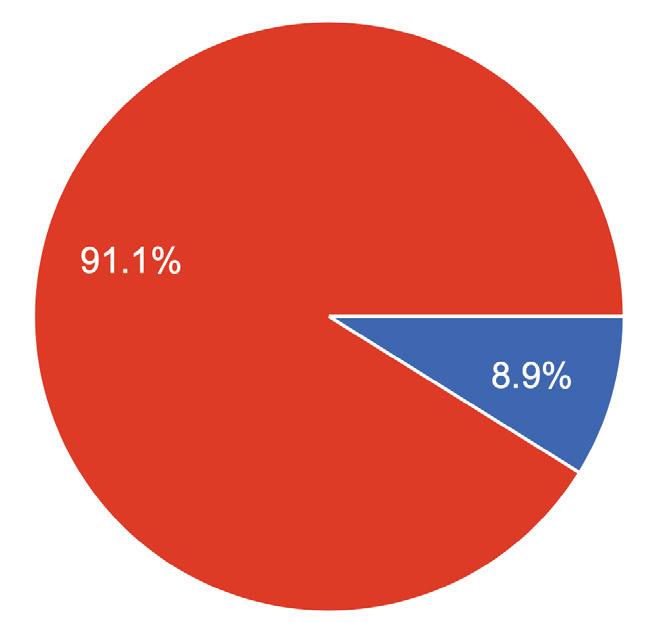

After his reelection in 1936, Roosevelt and the federal government felt confident in the state of the economy. Strong economic growth occurred in the four years after Roosevelt’s inauguration, as GDP grew 9% per year, and unemployment dropped from 25% to 14%.65 The belief that expansionary policy was no longer needed prevailed, as for the first time since 1929 commercial loans rose, indicating a rise of new business and a healthier economy.66 A proponent of this thought, Roosevelt intended to reduce expenditures in his proposed budget for 1938, stating to Congress on January 7, 1937, that economic “gains make it possible to reduce for the fiscal year 1938 many expenditures of the Federal Government which the general depression made necessary.”67

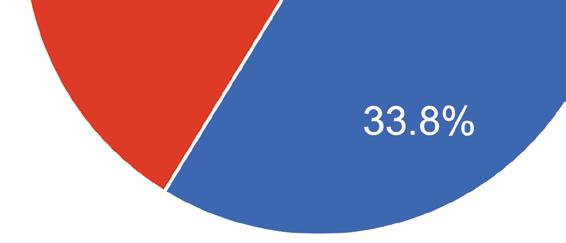

Faced with a recovering economy, the federal government introduced contractionary monetary and fiscal policy. Altogether, real government spending declined by $250 million, from September 1936 to October 1937. This decrease caused roughly 50% of the real GDP’s $690 million fall, from April 1937 to May 1938.68 Furthermore, the federal government collected social security taxes for the first time, funding Roosevelt’s new long-term welfare system.69 This dip in government spending and tax increase caused contractionary pressure, which was worsened by the Federal Reserve’s fear about inflation and a strategy to reel in the rising rate. After a few years of loose monetary policy, banks’ reserves were far over their legislated limit, and the Federal Reserve feared that it would be di cult to curb spending if inflation continued to rise or if “speculative excess” returned in the stock market.70 In July 1936, the board of governors at the Fed claimed that these excess reserves would create an “injurious credit expansion,” and that they “decided to lock it up,” as a “mea-

Volume VIII • Edition I May 2023 20

sure of protection.”71 Following this statement, the Fed doubled reserve requirements, reducing the ability of banks to have large reserves. Looking to keep their safety-cushions to avoid insolvency in times of economic downturn, banks reduced their lending, leading to a large monetary contraction.72

Reverting to hawkishness, Roosevelt refused to acknowledge warning signs of the recession as a problem, stubbornly holding the course of his budget-balancing plans. The country began to worry following a series of drastic stock declines in October, as telegrams poured into the White House attempting to persuade Roosevelt to close the stock market, as even his close advisor Henry Morgenthau complained that he was “terribly worried.”73 When asked to comment upon the “business situation” in a press conference on October 8, 1937, Roosevelt bluntly responded: “No.”74 Despite having been questioned on the deteriorating economy, Roosevelt proudly announced on October 19 that “the estimated expenditures under the recovery and relief program will be $1,139,000,000 less than in 1937.”75 Roosevelt’s Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau, a fiscal conservative, defended his commander-in-chief from those called for government spending once again, as he asserted in a speech to the Academy of Political Science on November 10, 1937, that “the emergency that we faced in 1933 no longer exists” and that “the domestic problems which us today are essentially di erent from those which faced us four years ago.”76

Having faced intense pressure and the advice of a trusted advisor, Roosevelt turned to government spending to end the Roosevelt Recession. One always willing to bend an ear, Roosevelt often followed the advice of his advisors when making decisions.77 One Harry Hopkins, a presidential advisor and a strong proponent of government spending, arranged a meeting with Roosevelt in Warm Springs, Georgia, arguing that a renewed spending program would allow the “whole culture” of America to express itself “through actions of individual consumers,” and to eventually reach “the abolition of poverty in the United States.”78 The argument, e ectively tailored

to Roosevelt’s ideals, apparently succeeded, as Roosevelt announced in a Fireside Chat on April 14, 1938, that “it has become apparent that government itself can no longer safely fail to take aggressive government steps to meet it [recovery],” and that “we have all learned the lesson that government cannot a ord to wait until it has lost the power to act.”79 Roosevelt furthermore demanded that “all the energies of government and business must be directed to increasing the national income,” and that since there is “a failure of consumer demand because of lack of buying power,” the government “must create an economic upturn.”80

With the Roosevelt Recession in hindsight, Roosevelt returned to his deficit spending ways. The signing of the second Agricultural Adjustment Act in February 1938 altered agricultural support programs of the Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1933 deemed unconstitutional in 1936 for overstepping federal jurisdiction in United States vs. Butler. 81 This act provided price support for farmers’ crops, paying them to not plant certain crops such as cotton, corn, and wheat to regulate output.82 Roosevelt designated this legislation an “e ective instrument to serve the welfare of our agriculture and all our people.”83 On April 2nd, 1938, Roosevelt requested $3.75 billion to support existing New Deal programs, splitting the funds among the Public Works Administration, the Works Progress Administration, and other relief bodies, while also giving loans to states and other public agencies.84

Roosevelt, furthermore, created the National Resources Planning Board (NRPB) in 1939, the fourth iteration of the previous National Planning Board (1933-1934), to develop new programs and provide advice. While his motivations remain unclear, it is widely believed that FDR endorsed and submitted its two largest reports to Congress to lay the foundation of post-war policy and for the 1944 election. Firstly, the Security, Work, and Relief Policies, 85 Their second report, National Resources Development, Report for 1943, Part I. Post-War Plan and Program, strongly pushed the need for full employment, in America’s “dynamic expanding economy” with “increasingly higher standards of living.”86 The Post-

Volume VIII • Edition I May 2023 21

War Plan and Program furthermore declared that “it should be the declared policy of the United States Government” to “promote and maintain a high level of national production and consumption,” to “underwrite full employment for the employables,” to “guarantee a job for every man released from the armed forces and the war industries at the close of the war, with fair pay and working conditions,” and to “guarantee and, when necessary, underwrite... equal access to security, equal access to education .... equal access to health and nutrition..., and wholesome housing conditions for all.”87

Conclusion

Although fiscally conservative at heart, FDR instituted deficit spending policy because of his beliefs on the social duty of government and the recession of 1937. FDR unequivocally held the opinion that the role of government was to aid its needy citizenry. Forming expansionary policies which reflected this ideology, FDR supported Americans unemployed from the Great Depression. The Roosevelt Recession secured FDR’s deficit spending policy. Referred to derisively as the Roosevelt Recession, when Roosevelt regressed to his budget-balancing beliefs, another dramatic recession followed, leading the president to completely abandon his budget-balancing agenda and commit to deficit spending. Ultimately, his evolution from budget hawk to deficit spender rested on both Roosevelt’s moral beliefs and the ramifications of contractionary monetary and fiscal policy.

FDR’s embrace of deficit spending continued with the emergence of a new crisis. With the prospect of a World War on the horizon in the late 1930s and early 1940s, President Roosevelt instituted deficit spending policies once again for national security.

From 1939-1940, war erupted in Europe, threatening the possibility of American involvement. On September 1st, 1939, Nazi Germany, led by their Dictator Adolf Hitler, invaded their bordering country Poland. This action forced Poland’s allies, Britain, and France, to declare war on Germany, e ectively beginning World War II.88 Two days later,

FDR delivered a fireside chat to the American people regarding the European war, warning them of the implications of this event. Roosevelt claimed that: “when peace has been broken anywhere, the peace of all countries everywhere is in danger.”89 Understanding the American public’s desire for neutrality, he continued to remind his listeners that: “passionately though we may desire detachment, we are forced to realize that every word that comes through the air, every ship that sails the sea, every battle that is fought does a ect the American future.”90

Believing in the inevitability of American involvement in the European war and the need for strengthening the American military, FDR brandished his deficit spending once again, bolstering the American munitions industry. As the war in Europe raged on, in a fireside chat on May 26th, 1940, FDR acknowledged the state that America’s military was in, and the reputation associated with it. He stated that “it is a known fact, however, that in 1933, when this Administration came into o ce, the United States Navy had fallen in standing among the navies of the world, in power of ships and in e ciency, to a relatively low ebb.”91 This weakness was reflected in FDR’s requests for the defense budget appropriation which skyrocketed from $1.3 billion in 1939, before the beginning of the war, to $4 billion in 1940.92 Furthermore defense spending as a percent of GDP rose dramatically as well from 1.2% in 1938, to 1.7% in 1940, to 5.1% in 1941.93 In a fireside chat on December 29th, 1940, FDR called Americans to further their e orts in production of munitions. He announced that “all of our present e orts are not enough. We must have more ships, more guns, more planes -- more of everything.”94

Motivated by these words and funded by federal spending, before the United States had entered the war, American factories had produced 4,383 tanks and self-propelled guns, over 10,000 planes, and almost 200,000 military trucks.95 These sentiments culminated on March 11th, 1941, with the passage of the landmark Lend-Lease Bill, which, created to produce and send the allied powers military aid, allowed Roosevelt to “sell, transfer title to, ex-

Volume VIII • Edition I May 2023 22

change, lease, lend, or otherwise dispose of, to any such government any defense article.”96 This bill was so e ective, that by the end of its use in 1945, America had produced and sent abroad nearly $50 billion worth of military equipment and arms.97 Thus, the advent of a new crisis, one of national security, drove President Roosevelt back into the arms of deficit spending.

Endnotes

1) Franklin Delano Roosevelt, “Address of Governor Franklin D. Roosevelt,” speech presented in Forbes Field, Pittsburg, PA, 1932, FDR Library

2) Ibid

3) Ibid

4) Ibid

5) Franklin Delano Roosevelt, “Address of Governor Franklin Delano Roosevelt Accepting the Presidential Nominee,” speech presented at Democratic National Convention, The Stadium, Chicago, IL, July 2, 1932, FDR Library, http://www.fdrlibrary.marist.edu/_resources/ images/msf/msf00494.

6) Ibid

7) Ibid

8) “Which Was Bigger: The 2009 Recovery Act or FDR’s New Deal?,” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, last modified May 2017, https://www.stlouisfed.org/ on-the-economy/2017/may/which-bigger-2009-recovery-act-fdr-new-deal.

9) Cli ord Kennedy Berryman, Old Reliable!, April 12, 1938, illustration, https://www.loc.gov/ item/2016679190/.

10) Kennedy, David, “The American Pageant,” Cengage Learning Inc., 2020, 188-189

11) William Janeway, “The Evolution of American Capitalism,” Project Syndicate, https://www.project-syndicate.org/onpoint/review-ages-of-american-capitalism-by-william-h-janeway-2021-08.

12) “Interstate Commerce Act (1887),” National Archives, https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/interstate-commerce-act.

13) Patrick Kiger, “Hate Paying Income Tax? Blame William H. Taft,” History, https://www.history.com/news/ income-tax-howard-taft.

14) “Panic of 1837,” Ohio History Central, https://ohiohistorycentral.org/w/Panic_of_1837#:~:text=In%20 1832%2C%20Andrew%20Jackson%20ordered,the%20 Ohio%20and%20national%20economies.

15) Gary Richardson and Tim Sablik, “Banking Panics of the Gilded Age,” Federal Reserve History, https://www. federalreservehistory.org/essays/banking-panics-ofthe-gilded-age.

16) Robert Keller, “Supply-Side Economic Policies during the Coolidge-Mellon Era,” Journal of Economic Issues 16, no. 3 (1982): 777, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4225215.

17) Ibid 773

18) Calvin Coolidge, “Inaugural Address,” speech, March 4, 1925, The American Presidency Project, https://www. presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/inaugural-address-50.

19) Calvin Coolidge, “Government and Business,” speech

presented at Chamber of Commerce of the State of New York, New York, November 19, 1925, Calvin Coolidge Presidential Foundation, https://coolidgefoundation. org/resources/government-and-business/.

20) Keller, “Supply-Side Economic,” 777-778

21) Ibid 780

22) Andrew W. Mellon, Taxation: The People’s Business (New York: Macmillan, 1924), 138

23) Rushad Thomas, “Tax Policy, Coolidge Style,” Coolidge Foundation, last modified January 26, 2015, https://coolidgefoundation.org/blog/tax-policycoolidge-style/.

24) Marks, Julie. “What Caused the Stock Market Crash of 1929.” History. Last modified April 27, 2021. https:// www.history.com/news/what-caused-the-stock-market-crash-of-1929.

25) Ibid

26) Ibid

27) Ibid

28) Parker, Je rey. “Case of the Day: The Great Depression.” Reed College. https://www.reed.edu/economics/ parker/201/cases/depression.html.

29) Marks, “What Caused,” History.

30) Parker, “Case of the Day,” Reed College.

31) Marks, “What Caused,” History.

32) Parker, “Case of the Day,” Reed College.

33) Ibid

34) Ibid

35) “Americans React to the Great Depression,” Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/classroom-materials/ united-states-history-primary-source-timeline/greatdepression-and-world-war-ii-1929-1945/americans-react-to-great-depression/.

36) Ibid

37) Jerry D. Marx, “American Social Policy in the Great Depression and World War II,” VCU Libraries, https:// socialwelfare.library.vcu.edu/eras/great-depression/ american-social-policy-in-the-great-depression-andwwii/.

38) Michael B. Katz, In the Shadow of the Poorhouse, 10th ed. (New York: BasicBooks, 1996), 224

39) “The Great Depression and President Hoover’s Response,” Couse Hero, https://www.coursehero.com/ study-guides/atd-fscj-ushistory2/brother-can-youspare-a-dime-the-great-depression/.

40) Ibid

41) “Herbert Hoover,” History, https://www.history. com/topics/us-presidents/herbert-hoover.

42) “The Great,” Couse Hero.

43) Niall Kishtainy, A Little History of Economics (New

Volume VIII • Edition I May 2023 23

Haven: Yale University Press, 2017), 104

44) “Keynes vs. Hayek: Two economic giants go head to head,” BBC

45) Victoria Chick. Macroeconomics After Keynes : A Reconsideration of the General Theory. Cambridge, Mass: The MIT Press, 1983, 8-9

46) “Keynes vs. Hayek: Two economic giants go head to head,” BBC

47) Ibid 318

48) Franklin Delano Roosevelt, “Address of Governor Franklin D. Roosevelt,” speech presented in Forbes Field, Pittsburg, PA, 1932, FDR Library

49) Julian E. Zelizer, “The Forgotten Legacy of the New Deal: Fiscal Conservatism and the Roosevelt Administration, 1933-1938,” Presidential Studies Quarterly 30, no. 2 (2000): 335, http://www.jstor.org/stable/27552097.

50) Ibid 336

51) Franklin Delano Roosevelt, “Radio Address on Unemployment and Social Welfare,” speech presented in Albany, NY, October 13, 1932, The American Presidency Project, https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/radio-address-unemployment-and-social-welfare-from-albany-new-york.

52) Ibid

53) Franklin Delano Roosevelt, “First Inaugural Address of Franklin D. Roosevelt,” speech presented at U.S. Capitol, District of Columbia, United States of America, March 4, 1933, The Avalon Project, https://avalon.law. yale.edu/20th_century/froos1.asp.

54) Franklin Delano Roosevelt, “Outlining the New Deal Program,” speech, FDR Library, http://docs.fdrlibrary. marist.edu/050733.html.

55) Franklin Delano Roosevelt, “Review of the Achievements of the Seventy-third Congress,” speech, June 28, 1934, FDR Library, http://docs.fdrlibrary.marist. edu/062834.html.

56) Franklin Delano Roosevelt, “On Moving Forward to Greater Freedom and Greater Security,” speech presented in The White House, District of Columbia, September 30, 1934, FDR Library, http://docs.fdrlibrary.marist. edu/093034.html.

57) Franklin Delano Roosevelt, “Speech at Madison Square Garden,” speech presented at Madison Square Garden, New York, NY, October 31, 1936, UVA Miller Center, https://millercenter.org/the-presidency/presidential-speeches/october-31-1936-speech-madisonsquare-garden.

58) Kennedy, The American, 751-752

59) Franklin Delano Roosevelt, “Outlining the New Deal Program,” speech, FDR Library.

60) Harry L. Hopkins, Spending to Save: The Complete Story of Relief, New York: W.W. Norton & Co., Inc., 1936, p. 117

61) Franklin Delano Roosevelt, “Speech to C.W.A. Conference in Washington.,” speech presented in District of Columbia, November 15, 1933, The American Presidency Project, https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/ speech-cwa-conference-washington.

62) David Kennedy, The American Pageant, 17th ed. (n.p.: Cengage Learning, 2020), 752-3.

63) Franklin Delano Roosevelt, “Speech of the President,” speech presented in Forbes Field, Pittsburgh, PA, October 1936, FDR Library, https://www.fdrlibrary.org/ documents/356632/390886/smCampaign_10-1-1936.pdf/ f10a1d08-6eaf-466e-86e8-99b4678c69bc

64) Franklin Delano Roosevelt, “Annual Message,” speech presented at State of the Union, Washington DC, United States of America, January 3, 1938, FDR Library, https://www.fdrlibrary.org/documents/356632/390886/ smAnnual+Message_1938.pdf/cbd75ed8-a5fa-4e47-a1c2fe56f97649d7.

65) Christina Romer, “The lessons of 1937,” Economist 66) Rafti, Jonian. 2015. Roosevelt’s Recession: A Historical and Econometric Examination of the Roots of the 1937 Recession. Inquiries Journal/Student Pulse 7 (06), http://www.inquiriesjournal.com/a?id=1053

67) Ibid

68) Ibid

69) Christina Romer, “The lessons of 1937,” Economist

70) Ibid

71) Ibid

72) Ibid

73) Transcript of Phone Call between Morgenthau and FDR, October 20, 1937, Volume 93: October 20-October 31, 1937; Page 21, The Diaries of Henry Morgenthau, Jr., Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library & Museum, Hyde Park, NY.

74) “Press Conference #401,” April 2, 1937, Page 1, Press Conferences of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, 19331945, Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library & Museum.

75) Roosevelt, “Statement Summarizing the 1938,” The American Presidency Project.

76) Complete Set of Speech Drafts, Volume 97: November 10, 1937; Page 142, Diaries of Henry Morgenthau, Jr., Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library & Museum, Hyde Park, NY.

77) Zelizer, “The Forgotten,” 333

78) “Recession of 1937 .” Encyclopedia of the Great Depression. . Encyclopedia.com. (March 28, 2022). https:// www.encyclopedia.com/economics/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/recession-1937

79) Roosevelt, Franklin. “On the Recession.” Speech, Washington, DC, April 14, 1938. Miller Center. https:// millercenter.org/the-presidency/presidential-speeches/april-14-1938-fireside-chat-12-recession

80) Ibid

81) United States v. Butler, 297 U.S. 1 (1936), Oyez

82) Lisa Thompson, “Agricultural Adjustment Act (1933, Reauthorized 1938),” The Living New Deal, https:// livingnewdeal.org/glossary/agricultural-adjustment-act-1933-re-authorized-1938- 2/#:~:text=The%20 Agricultural%20Adjustment%20Act%20(AAA,to%20 struggling%20farmers%20%5B2%5D.

83) Franklin Delano Roosevelt, “Statement on Signing the Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1938.,” speech, February 16, 1938, The American Presidency Project, https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/statement-signing-the-agricultural-adjustment-act-1938.

84) Robert Goldston, Great Depression: The U.S. in the

Volume VIII • Edition I May 2023 24

Thirties (1968) page 229

85) Je ries, John W. “The ‘New’ New Deal: FDR and American Liberalism, 1937-1945.” Political Science Quarterly 105, no. 3 (1990): 398–399. https://doi. org/10.2307/2150824.

86) Ibid 399

87) Ibid 413

88) “World War II Major Events Timeline,” PBS, https:// www.pbs.org/wgbh/masterpiece/specialfeatures/ world-war-ii-major-events-timeline/#.

89) Franklin Delano Roosevelt, “On the European War,” speech, September 3, 1939, FDR Library, http://docs. fdrlibrary.marist.edu/090339.html.

90) Ibid

91) Ibid

92) https://www.thebalance.com/fdr-economic-policies-and-accomplishments-3305557

93) Price Fishback, “World War II in America: Spending, Deficits, Multipliers, and Sacrifice,” Vox EU CEPR, last modified November 12, 2019, https://voxeu.org/article/ world-war-ii-america-spending-deficits-multipliers-and-sacrifice#:~:text=The%20federal%20government%20ramped%20up,high%20unemployment%20 and%20unused%20capacity.

94) Franklin Delano Roosevelt, “On National Security,” speech, December 29, 1940, FDR Library, http://docs. fdrlibrary.marist.edu/122940.html.

95) “U.S. Arms Production,” WW2-Weapons, https:// www.ww2-weapons.com/u-s-arms-production/.

96) Lend Lease, H.R. 1776. https://www.archives.gov/ milestone-documents/lend-lease-act.

97) Kennedy, The American, 784

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Berryman, Cli ord Kennedy. Old Reliable! April 12, 1938. Illustration. https://www.loc.gov/item/20166791 90/.

Complete Set of Speech Drafts, Volume 97: November 10, 1937; Page 142, Diaries of Henry Morgenthau, Jr., Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library & Museum, Hyde Park, NY.

Coolidge, Calvin. “Government and Business.” Speech presented at Chamber of Commerce of the State of New York, New York, November 19, 1925. Cal vin Coolidge Presidential Foundation. https:// coolidgefoundation.org/resources/governmentand-business/.

Lend Lease, H.R. 1776. https://www.archives.gov/mile stone-documents/lend-lease-act.

Mellon, Andrew W. Taxation: The People’s Business. New York: Macmillan, 1924.

Roosevelt, Franklin Delano. “Inaugural Address.” Speech, March 4, 1925. The American Presidency Project https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/docu ments/inaugural-address-50.

Roosevelt, Franklin Delano. “Address of Governor Franklin Delano Roosevelt Accepting the Presidential Nominee.” Speech presented at Democratic National Convention, The Stadium, Chicago, IL, July 2, 1932. FDR Library. http:// www.fdrlibrary.marist.edu/_resources/images/ msf/msf00494.

Roosevelt, Franklin Delano. “Address of Governor Franklin D. Roosevelt.” Speech presented in Forbes Field, Pittsburgh, PA, 1932. FDR Library.

https://www.fdrlibrary.org/documents/356632/ 390886/smCampaign_10-19-1932.pdf/eda3f6904176-4d1f-8 f-7b432964f34f.

Roosevelt, Franklin Delano. “Annual Message.” Speech presented at State of the Union, Washington DC, United States of America, January 3, 1938. FDR Library. https://www.fdrlibrary.org/ documents/356632/390886/smAnnual+Mes sage_1938.pdf/cbd75ed8-a5fa-4e47-a1c2-fe56f9 7649d7.

Roosevelt, Franklin Delano. “First Inaugural Address of Franklin D. Roosevelt.” Speech presented at U.S. Capitol, District of Columbia, United States of America, March 4, 1933. The Avalon Project. https://avalon.law.yale.edu/20th_century/froo s1.asp.

Roosevelt, Franklin Delano. “On Moving Forward to Greater Freedom and Greater Security.” Speech presented in The White House, District of Columbia, September 30, 1934. FDR Library. http://docs.fdrlibrary.marist.edu/093034.html.

Roosevelt, Franklin Delano. “On National Defense.” Speech, May 26, 1940. FDR Library. http://docs. fdrlibrary.marist.edu/052640.html.

Roosevelt, Franklin Delano. “On National Security.” Speech, December 29, 1940. FDR Library. http:// docs.fdrlibrary.marist.edu/122940.html.

Roosevelt, Franklin Delano. “On the European War.” Speech, September 3, 1939. FDR Library. http:// docs.fdrlibrary.marist.edu/090339.html.

Roosevelt, Franklin Delano. “Outlining the New Deal Program.” Speech. FDR Library. http:// docs.fdrlibrary.marist.edu/050733.html.

Volume VIII • Edition I May 2023 25

Roosevelt, Franklin Delano. “Press Conference #401,” April 2, 1937, Page 1, Press Conferences of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, 1933-1945, Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library & Museum.

Roosevelt, Franklin Delano. “Radio Address on Un employment and Social Welfare.” Speech presented in Albany, NY, October 13, 1932. The American Presidency Project. https://www. presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/radio-ad dress-unemployment-and-social-welfare-fromalbany-new-york.

Roosevelt, Franklin Delano. “Review of the Achieve ments of the Seventy-third Congress.” Speech, June 28, 1934. FDR Library. http://docs.fdrli brary.marist.edu/062834.html.

Roosevelt, Franklin Delano. “Statement on Signing the Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1938.” Speech, February 16, 1938. The American Presidency Project. https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/statement-signing-the-agricultural-ad justment-act-1938.

Roosevelt, Franklin Delano. “Speech at Madison Square Garden.” Speech presented at Madison Square Garden, New York, NY, October 31, 1936. UVA Miller Center. https://millercenter.org/ the-presidency/presidential-speeches/october31-1936-speech-madison-square-garden.

Roosevelt, Franklin Delano. “Speech of the President.” Speech presented in Forbes Field, Pittsburgh, PA, October 1936. FDR Library. https://www.fdrlibrary.org/documents/356632/390886/sm Campaign_10-1-1936.pdf/f10a1d08-6eaf-466e86e8-99b4678c69bc.

Roosevelt, Franklin Delano. “Speech to C.W.A. Conference in Washington.” Speech presented in District of Columbia, November 15, 1933. The American Presidency Project. https://www. presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/speech-cwaconference-washington.

Roosevelt, Franklin Delano. “Statement Summarizing the 1938 Budget, October 19, 1937.” The American Presidency Project.

Transcript of Phone Call between Morgenthau and FDR, October 20, 1937, Volume 93: October 20October 31, 1937; Page 21, The Diaries of Henry Morgenthau, Jr., Franklin D. Roosevelt Presiden tial Library & Museum, Hyde Park, NY.

Secondary Sources

“Americans React to the Great Depression.” Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/classroom-mate rials/united-states-history-pri mary-sourcetimeline/great-depression-and-world-war-ii1929-1945/americans-react-to-great-depression/.

Chick, Victoria. Macroeconomics after Keynes: A Recon sideration of the General Theory. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1983.

“F.D.R., Budget Hawk.” The New York Times (New York, NY), July 29, 2011. https://www.nytimes.com/ roomfordebate/2011/07/20/presidents-andtheir-debts-fdr-to-bush/fdr-budget-hawk.

“FDR: From Budget Balancer to Keynesian.” Franklin D. Roosevelt. https://www.fdrlibrary.org/budget.

Fishback, Price. “World War II in America: Spending, Deficits, Multipliers, and Sacrifice.” Vox EU CEPR. Last modified November 12, 2019. https:// voxeu.org/article/world-war-ii-america-spend ing-deficits-multipliers-and-sacrifice#:~:tex t=The%20federal%20government%20 ramped%20up,high%20unemployment%20 and%20unused%20capacity.

“From WWII to the Treasury-Fed Accord.” Federal Re serve History. Last modified November 22, 2013. https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/ wwii-to-the-treasury-fed-accord.

“The Great Depression and President Hoover’s Re sponse.” Couse Hero. https://www.coursehero. com/study-guides/atd-fscj-ushistory2/brothercan-you-spare-a-dime-the-great-depression/.

Hamilton, David E. “Herbert Hoover: Impact and Legacy.” Miller Center. https://millercenter.org/pres ident/hoover/impact-and-legacy.

“Herbert Hoover.” History. https://www.history.com/ topics/us-presidents/herbert-hoover.

Hopkins, Harry L. “Spending to Save: The Complete Story of Relief,” New York: W.W. Norton & Co., Inc., 1936.

“Interstate Commerce Act (1887).” National Archives. https://www.archives.gov/milestone-docu ments/interstate-commerce-act.

Irwin, Douglas. “What caused the recession of 1937-38?” VoxEu CEPR. Last modified September 11, 2011. https://voxeu.org/article/what-caused-reces sion-1937-38-new-lesson-today-s-policymakers.

Janeway, William. “The Evolution of American Capi talism.” Project Syndicate. https://www.projectsyndicate.org/onpoint/review-ages-of-ameri

Volume VIII • Edition I May 2023 26

can-capitalism-by-william-h-janeway-2021-08.

Je ries, John W. “The ‘New’ New Deal: FDR and American Liberalism, 1937-1945.” Political Sci ence Quarterly 105, no. 3 (1990): 398–399. https://doi.org/10.2307/2150824.

Keller, Robert. “Supply-Side Economic Policies during the Coolidge-Mellon Era.” Journal of Economic Issues 16, no. 3 (1982). http://www.jstor.org/sta ble/4225215.

Kennedy, David. The American Pageant. 17th ed. N.p.: Cengage Learning, 2020.

“Keynes vs. Hayek: Two economic giants go head to head.” BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/busi ness-14366054.

Kiger, Patrick. “Hate Paying Income Tax? Blame William H. Taft.” History. https://www.history.com/ news/income-tax-howard-taft.

Kishtainy, Niall. A Little History of Economics. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2017.

Koehn, Nancy F. “The Tale of the Dueling Econo mists.” The New York Times. https://www. nytimes.com/2011/10/23/business/keyneshayek-views-origins-of-an-economics-debatereview.html.

Marks, Julie. “What Caused the Stock Market Crash of 1929.” History. Last modified April 27, 2021. https://www.history.com/news/what-causedthe-stock-market-crash-of-1929.

Marx, Jerry D. “American Social Policy in the Great Depression and World War II.” VCU Libraries. https://socialwelfare.library.vcu.edu/eras/greatdepression/american-social-policy-in-thegreat-depression-and-wwii/.

Michael B. Katz, In the Shadow of the Poorhouse, 10th ed. (New York: BasicBooks, 1996)

Morgenthau, Henry. “Henry Morgenthau Diary, Micro film Roll #50f.” May 9, 1939. Franklin Delano Roosevelt Library, Hyde Park, NY.

“Panic of 1837.” Ohio History Central. https://ohio historycentral.org/w/Panic_of_1837#:~:text= In%201832%2C%20Andrew%20Jackson%20or dered,the%20Ohio%20and%20national%20 economies.

Parker, Je rey. “Case of the Day: The Great Depression.” Reed College. https://www.reed.edu/economics/ parker/201/cases/depression.html.

Rafti, Jonian. “Roosevelt’s Recession: A Historical and Econometric Examination of the Roots of the 1937 Recession.” Inquiries Journal/Student Pulse 7, no. 6 (2015). http://www.inquiriesjournal.com /articles/1053/roosevelts-recession-a-histori cal-and-econometric-examination-of-the-rootsof-the-1937-recession.

Richardson, Gary, and Tim Sablik. “Banking Panics of the Gilded Age.” Federal Reserve History. https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/ banking-panics-of-the-gilded-age.

Romer, Christina. “The lessons of 1937.” Economist. https://www.economist.com/finance-and-eco nomics/2009/06/18/the-lessons-of-1937.

Roosevelt, Franklin Delano. “Address of Governor Franklin Delano Roosevelt Accepting the Presidential Nominee.” Speech presented at Democratic National Convention, The Stadium, Chicago, IL, July 2, 1932. FDR Library. http:// www.fdrlibrary.marist.edu/_resources/images/ msf/msf00494.

Thompson, Lisa. “Agricultural Adjustment Act (1933, Reauthorized 1938).” The Living New Deal. https://livingnewdeal.org/glossary/agricultural -adjustment-act-1933-re-authorized-1938-2/#:~ :text=The%20Agricultural%20Adjustment%20 Act%20(AAA,to%20struggling%20farmers%20 %5B2%5D.

Thomas, Rushad. “Tax Policy, Coolidge Style.” Coolidge Foundation. Last modified January 26, 2015. https://coolidgefoundation.org/blog/tax-policycoolidge-style/.

“U.S. Arms Production.” WW2-Weapons. https://www. ww2-weapons.com/u-s-arms-production/.

Wapshott, Nicholas. Keynes Hayek: The Cash That Defined Modern Economics. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2011.

“Which Was Bigger: The 2009 Recovery Act or FDR’s New Deal?” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Last modified May 2017. https://www.stlouisfed. org/on-the-economy/2017/may/which-bigger2009-recovery-act-fdr-new-deal.

“World War II Major Events Timeline.” PBS. https:// www.pbs.org/wgbh/masterpiece/specialfea tures/world-war-ii-major-events-timeline/#.

Zelizer, Julian E. “The Forgotten Legacy of the New Deal: Fiscal Conservatism and the Roosevelt Ad ministration, 1933-1938.” Presidential Studies Quarterly 30, no. 2 (2000). http://www.jstor.org/ stable/27552097.

Volume VIII • Edition I May 2023 27

The Ignored Illness

Author: Davis Woolbert ‘25

Many may guess that missing limbs, gunshot wounds, or infections were the most debilitating conditions su ered by British soldiers in the bloody battles of World War I. In fact, shell shock was the most prevalent condition endured by British soldiers during WWI, and yet it was largely ignored for years on end. Shell shock was a term used to describe the psychological e ects of combat on soldiers during World War I. The condition was prevalent among soldiers who had experienced prolonged exposure to the horrors of trench warfare, including constant shelling and the threat of enemy attack. Many soldiers su ering from shell shock were unable to return to combat, and the condition was a significant contributor to the high rates of illness and injury among British soldiers during the war. There were 80,000 cases of shell shock reported by the British Army between 1914 and 1918. The sheer number of cases forced both doctors and the British public to reckon with their understanding of the illness.1 As a result, World War I led to significant changes in how both doctors and the British public perceived shell shock, as well as advancements in the diagnosis and treatment of the condition.

During WWI, shell shock emerged as a significant issue as soldiers experienced the intense and prolonged combat of the war. The term “shell shock” was first used in 1915 by the British physician Charles Myers to describe soldiers su ering from a range of symptoms, including “loss of memory, vision, smell, and taste,” according to the British medical jour-

nal, The Lancet.2 However, the concept of shell shock and its symptoms have likely existed for as long as humans have experienced traumatic events. Yet, the first formal attempts to treat shell shock were not until the American Civil War (1861-1865) and the Franco-Prussian War (1870-1871), when military veterans suffering from the condition were given medical treatment.3 By WWI, despite decades of attempts at treatment, British soldiers with shell shock were often looked down upon and faced di culty obtaining disability payments from the government.

British soldiers unable to return to fighting struggled to cope, and often received little support from a government seeking to avoid payments for psychological illness.4 With the government reluctant to pay out pensions, many traumatized war veterans were unable to hold down jobs or return to their pre-war lives.5 However, despite the ongoing struggles victims of shell shock faced, WWI did engender a shift in the perception and treatment of shell shock.

First, World War I catalyzed significant change in the medical perception of shell shock in the United Kingdom. Before World War I, the term “shell shock” was used to describe a range of symptoms that were observed in soldiers who had been exposed to the intense stress of combat.6 As stated in an article by the American Psychological Association, “Symptoms included fatigue, tremor, confusion, nightmares and impaired sight and hearing. [Shell shock] was often diagnosed when a soldier was unable to function and no obvious cause could be identified.”7 Initially, doctors believed that the symptoms were a

Volume VIII • Edition I May 2023 28

result of the physical e ects of being near explosions, but as the war continued, it became clear that the symptoms were actually a form of psychological trauma.8 Pre-WWI medical perceptions of shell shock included Disordered Action of the Heart (DAH) and Railway Spine.9 In 1864, W. C. Maclean, a professor of military medicine at the Army Medical School, Netley, suggested that the weight and distribution of soldiers’ equipment was responsible for functional heart disorders such as palpitations and “a ections of the lungs and heart.”10 Maclean surveyed 5,500 soldiers admitted to the Royal Victoria Hospital, Netley, between 1863 and 1866 and concluded that the o cial nomenclature in use in the service did not have a heading to include what he called “irritable heart.”11 He believed that the belts and pack-straps worn by soldiers caused a “most injurious system of constriction” that led to these heart disorders.12 By 1900, another theory called Railway Spine was suggested.13 Dr. Morgan Finucane, a civil surgeon at Connaught Hospital during the Boer War, observed soldiers displaying similar nervous and motor symptoms to those observed after railway accidents.14 This led to the theory that concussion caused by explosions led to chronic inflammation of the spinal cord and a general disturbance of the central nervous system.15 DAH and Railway Spine are two examples of somatic medical diagnoses that were o ered for shell shock symptoms prior to World War I. However, when soldiers exposed to battle during World War I began exhibiting symptoms of shell shock at increasingly alarming rates, psychological, rather than physical causes became the focus of medical study. In 1915, the British Army assigned Charles S.

Myers, a medically trained psychologist, as a consultant to the British Expeditionary Force to “o er opinions on cases of shell shock and gather data for a policy to address the burgeoning issue of psychiatric battle casualties.”16 The first cases Myers studied exhibited physical symptoms such as impaired hearing and sight, tremors, loss of balance, headache, and fatigue.17 However, despite the physicality of the symptoms he recorded, Myers concluded that these men “were psychological rather than physical casualties” and believed that the symptoms were “overt manifestations of repressed trauma.”18 In 1917, Myers convinced the British War O ce to set up training courses “in the principles and practice of military psychiatry” in order to treat shell shock.19 This marked a shift in the medical perception of shell shock, as it was now recognized as a form of psychological trauma rather than physical injury.20 The recognition of shell shock as a psychological injury had significant implications for the treatment of soldiers su ering from this condition. Previously, soldiers with shell shock were often

seen as malingerers or cowards, and they were often punished or ostracized.21 With the shift in medical perception, however, soldiers with shell shock were now seen as brave men who had endured the horrors of war and needed proper medical care. This change in attitudes towards shell shock and the development of treatment methods for this condition were important steps towards a better understanding of psychological trauma and its e ects on individuals.

The British public’s perception of shell shock in the UK also changed significantly as a result of World War I. Before the war, shell

Volume VIII • Edition I May 2023 29

shock was not well understood and was often seen as a sign of weakness or cowardice, reflecting British society’s deeply embedded ideas of masculinity and the expectation that soldiers display bravery at all times.22,23 Tracey Loughran, Senior Lecturer in History at Cardi University, describes the pressure that young men felt concerning military service in WWI by highlighting Oscar Wilde’s eldest son, Cyril.24 She writes of Cyril’s worry “over how others might judge his ability to live up to masculine ideals” as evidenced by his own words upon enlisting, “’first and foremost, I must be a man. There was to be no cry of decadent artist, of e eminate aesthete, of weak-kneed degenerate.’”25 Often soldiers who experienced shell shock viewed their own symptoms as weakness and cowardice, reflecting society’s belief, as exemplified by Cyril Wilde, that shell shock was indeed perceived as a want of bravery and masculinity.26 Many civilians prior to and in the early stages of WWI speculated that “those a ected by it were faking the condition to get out of having to fight.”27 British Private Walter Grover, who served on the Western front in Germany from 1916 to 1919, wrote that many in the army and those back home claimed that men su ering from shell shock “were in fact cowards.”28 Indeed, from the start of the war up until 1917, at least 346 British soldiers were shot on orders from their commanding ocers, accused of desertion or cowardice.29 In truth, many were actually su ering from shell shock.30 However, as the war progressed and more soldiers began experiencing symptoms of shell shock, it became clear that the condition was not an excuse to avoid fighting; it was

psychological illness.31 This realization led to a shift in the public’s perception of shell shock, with more support given to soldiers who experienced it and a greater understanding of the psychological e ects of war.32 After World War I, British civilians began to understand that shell shock was a real medical condition and not indicative of character weakness.33

The reality of the trauma their soldiers faced was widespread and undeniable, leading to a push for the government to pay remuneration to soldiers su ering from shell shock symptoms. The

public pressured their representatives in government until “MP’s of all parties” sought “to grant compensation to those with mental disorders.”34 Such public pressure demonstrates a clear shift in the public’s perception of shell shock. As a result of this public pressure, more support was given to soldiers who experienced shell shock, and they were treated with more compassion and understanding.

The diagnosis and treatment of shell shock in the UK underwent significant changes as a result of the immense number of shell shock incidents that occurred during World War I. Initially, doctors had believed that shell shock was caused by physical injuries sustained from the explosion of artillery shells, and therefore focused on treating the condition’s physical symptoms.35 However, as the war went on and more and more soldiers began to exhibit the symptoms of shell shock, doctors began to realize that the condition was caused by psychological as well as physical injuries.36 “By 1917, local newspapers reported ‘much mental derangement among young soldiers’ and by 1918, ‘numbers treated at Craig

Volume VIII • Edition I May 2023 30

House were greater than they had ever been’,” indicating the increasing prevalence of psychiatric disturbance among soldiers and the need for more e ective treatment methods. This shift in understanding led to a change in the way that shell shock was diagnosed, with doctors coming to recognize it as a form of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder that required psychological support and therapy.38 Edgar Jones and Simon Wessely highlight the challenges faced by medical professionals in accurately diagnosing the condition by stating, “Traumatized soldiers presented in a variety of ways during World War One, although the diagnosis doctors had the greatest di culty understanding and therefore treating was shell shock.”

In addition to a shift from physical to psychological-based diagnoses, the treatments for shell shock also changed dramatically as a result of WWI, with doctors experimenting with a range of therapies including hypnosis, psychoanalysis, and rest cures in an e ort to help patients manage their symptoms.39 Tracey Loughran, in her novel Shell-Shock and Medical Culture in First World War Britain, states, “The uneven and complex e ects of the war on British psychological medicine are perhaps most evident in the therapies deployed, created, revived, and adapted to manage and cure ‘shell-shock’,” indicating an expanded variety of approaches attempted in an e ort to address the problem.40 Overall, doctors developed many more e ective methods of diagnosis and treatment of shell shock as a result of World War I. The combat in the UK during WWI helped “troubleshoot” shell shock treatment for doctors in Britain, allowing for the development of new approaches and therapies that could better address the psychological e ects of combat on soldiers.41 The recognition of shell shock as a form of PTSD and the shift towards psychological support and therapy marked a significant change in the way the condition was approached by medical professionals, and helped improve the care and treatment available to soldiers su ering from the e ects of combat.

World War I brought shell shock into the limelight for British doctors and citizens.

The new understanding of the condition as psychologically based resulted in significant improvements in the British medical and public perception of soldiers su ering from it. Diagnosis and treatment shifted focus from physical rehabilitation to psychological analyses and therapies.42 The modern treatment of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder is largely based on the way shell shock treatment was adapted and refined during WWI.43 It is clear that World War I played a pivotal role in shaping the understanding and treatment of PTSD today. For example, the Medical superintendent of the Red Cross Military hospital at Maghull (Liverpool) began exploring connections between soldiers’ memories and shell shock symptoms during WWI. The Superintendent would explore the patients’ personal histories and connect emotional traumas to symptoms, gently explaining the connections to the soldiers.44 These “talking cures” used at Maghull are viewed as the precursors for modern PTSD treatments such as individual and group therapy and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy.45 The latter utilizes the ideas implemented at Maghull— helping patients to confront reminders of trauma in order to reduce stress.46 Overall the legacy of World War I and the changes in the understanding and perception of shell shock continue to shape modern approaches and perceptions of PTSD, benefitting soldiers all over the world.

Volume VIII • Edition I May 2023 31

Endnotes

1) Close, Jobe. n.d. “Vera Brittain and the Shell-Shocked Women of World War One.” Historic UK. Accessed January 5, 2023. https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/ HistoryofBritain/Vera-Brittain/.

2) ”From shell shock and war neurosis to posttraumatic stress disorder.” https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3181586/. Accessed 3 Jan. 2023.

3) Friedman, Matthew J. 2022. “History of PTSD in Veterans: Civil War to DSM-5 - PTSD: National Center for PTSD.” National Center for PTSD. https://www.ptsd. va.gov/understand/what/history_ptsd.asp.

4) Loughran, Tracey, and Wilfred Owen. 2018. “Shell shock - World War One.” The British Library. https:// www.bl.uk/world-war-one/articles/shell-shock.

5) Ibid

6) “From shell shock and war neurosis to posttraumatic stress disorder: a history of psychotraumatology.” n.d. NCBI. Accessed January 5, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm. nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3181586/.

7) “Shell shocked.” 2012. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/monitor/2012/06/shellshocked.

8) Friedman, Matthew J. 2022. “History of PTSD in Veterans: Civil War to DSM-5 - PTSD: National Center for PTSD.” National Center for PTSD. https://www.ptsd. va.gov/understand/what/history_ptsd.asp.

9) Jones, Edgar. 2005. Shell Shock to PTSD: Military Psychiatry from 1900 to the Gulf War. N.p.: Psychology Press. #8

10) Ibid

11) Jones, Edgar. 2005. Shell Shock to PTSD: Military Psychiatry from 1900 to the Gulf War. N.p.: Psychology Press. #9

12) Ibid

13) Jones, Edgar. 2005. Shell Shock to PTSD: Military Psychiatry from 1900 to the Gulf War. N.p.: Psychology Press. #14

14) Ibid

15) Ibid

16) “Shell shocked.” 2012. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/monitor/2012/06/shellshocked.

17) Ibid

18) Ibid

19) Ibid

20) “From shell shock and war neurosis to posttraumatic stress disorder.” https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/ articles/PMC3181586/. Accessed 3 Jan. 2023.

21) Ibid

22) “Shell shocked.” 2012. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/monitor/2012/06/shellshocked.

23) “Masculinity, trauma and ‘shell-shock’ | BPS.” 2015. British Psychological Society. https://www.bps.org.uk/ psychologist/masculinity-trauma-and-shell-shock.

24) Ibid

25) Ibid

26) “Shell Shock After The First World War.” n.d. Imperial War Museums. Accessed January 3, 2023. https:// www.iwm.org.uk/history/voices-of-the-first-worldwar-shell-shock.

27) Ibid

28) Ibid

29) “From shell shock and war neurosis to posttraumatic stress disorder: a history of psychotraumatology.” n.d. NCBI. Accessed January 5, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm. nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3181586/.

30) Ibid

31) Park, Joanna, Louise Neilson, and Andreas K. Demetriades. 2022. “Hysteria, head injuries and heredity: ‘shell-shocked’ soldiers of the Royal Edinburgh Asylum, Edinburgh (1914–24).” The Royal Society Publishing. https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/ rsnr.2021.0057.

32) “From shell-shock to PTSD, a century of invisible war trauma.” 2018. PBS. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/nation/from-shell-shock-to-ptsd-a-century-of-invisible-war-trauma.

33) Jones, Edgar. 2005. Shell Shock to PTSD: Military Psychiatry from 1900 to the Gulf War. N.p.: Psychology Press. #14

34) Jones, Edgar. 2005. Shell Shock to PTSD: Military Psychiatry from 1900 to the Gulf War. N.p.: Psychology Press. #143

35) Jones, Edgar. n.d. “‘Shell shock’ Revisited: An Examination of the Case Records of the National Hospital in London.” NCBI. Accessed January 5, 2023. https://www. ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4176276/.

36) “From shell shock and war neurosis to posttraumatic stress disorder: a history of psychotraumatology.” n.d. NCBI. Accessed January 5, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm. nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3181586/.

37) Park, Joanna, Louise Neilson, and Andreas K. Demetriades. 2022. “Hysteria, head injuries and heredity: ‘shell-shocked’ soldiers of the Royal Edinburgh Asylum, Edinburgh (1914–24).” The Royal Society Publishing. https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/ rsnr.2021.0057.