TONY LLOYD

HIGH PLAINS DRIFT

Benalla Art Gallery

17 March - 7 May 2023

Contributing Authors

Eric Nash

Dr Peter Hill

Tony Lloyd

Benalla Art Gallery would like to acknowledge the artist Tony Lloyd for his efforts in helping us realise this exhibition, and the logistical support provided through his commercial galleries MARS Gallery Melbourne, Hill Smith Art Advisory Adelaide, and Gallery 9 Sydney. Our thanks also to artist, writer, and independent curator, Professor Peter Hill (PhD), for so eloquently capturing the power of Tony’s painting practice.

Publisher

Benalla Art Gallery

Benalla Rural City Council PO Box 227

Benalla VIC 3671 gallery@benalla.vic.gov.au

Organised by Benalla Art Gallery

Eric Nash Director

Brenda Wellman Education & Public Programs Curator

Katherine Hauptmann Administration and Customer Relations Officer

Trish McGann Art Gallery Assistant

Tegan Nash Education & Public Programs Curator

Rachael O’Brien Art Gallery Assistant

Sonia Gherdevich Art Gallery Assistant

©Benalla Art Gallery, Benalla Rural City Council and the authors 2023

In stark contrast to Tony Lloyd’s epic landscapes which unfold before our eyes, the art world has a habit of becoming smaller.

I first had the pleasure of meeting Tony in 2017, having not long relocated to Melbourne. I had a limited network, and was amidst a period of both exciting and challenging professional change.

Tony, with fellow artist Sam Leach and writer Ashley Crawford, was preparing for the fifth instalment of |notfair|, an exhibition designed to “showcase independent artists who often do not fit the commercial mould and are overlooked and under-recognised.”

The event, staged in the derelict old Nuttelex factory in Windsor, presented conceptual and physical challenges for Tony and his contemporaries. My voluntary contribution was minor, but observing Tony in his role of event co-founder and curator, I recognised an intense drive and deep engagement with contemporary art. He held an evident passion for artists and audiences, and an openness to welcome people into the fold.

It is with pleasure I now have the opportunity to welcome Tony into the fold at Benalla Art Gallery, and do so with great confidence that our audience will marvel at his work.

Painted from both photographs and memory and inspired by hiking trips around Australia, New Zealand, and Switzerland, the works evoke the vast and epic landscapes of the High Country near to Benalla. Indeed, Mount Buffalo is the subject of one particular work. Tony’s hyperreal landscapes go beyond pictorial representation. They occupy the same rarefied air as the landscapes themselves, and through their exacting execution, have audiences questioning the slippery space between reality and fantasy.

I thank Tony for sharing High Plains Drift with Benalla Art Gallery audiences. I acknowledge Benalla Rural City Council’s support of the Gallery, and also wish to recognise the continued and skilled efforts of the Benalla Art Gallery team. That recognition is extended to our Members, Volunteers, Friends, and Committee.

Eric Nash Director, Benalla Art Gallery

Tony Lloyd at The Jungfrau, one of the main summits of the Bernese Alps, Switzerland

Photo: Sam Mikkelsen

Tony Lloyd at The Jungfrau, one of the main summits of the Bernese Alps, Switzerland

Photo: Sam Mikkelsen

I’m not the first person to begin an interview with Tony Lloyd with a simple two-word question. “Why mountains?” I asked. We’re sitting in the basement storage space of MARS Gallery in Windsor, surrounded by a selection of dazzling works about to travel north to Benalla.

“I had a really transformative experience when I did a residency at the British School in Rome in 2007,” Tony tells me. “Walking around this amazing city you are constantly surrounded by two thousand years of architectural ruins. This immersion in deep time influenced my paintings while I was there. But when I got back to my studio in Melbourne, I began to wonder, how much further back in time could I see? Archaeology led me to Geology and I began thinking of mountains as the manifestation of millions of years of tectonic forces. This was the deeper sense of time I could put in my paintings.”

Mountains are not the artist’s only subject matter1, but they do dominate his oeuvre. Early on he decided there would be no human presence at all in these works. Just raw mountains and weather. “But I broke this rule pretty quickly,” he told me, much to my

approval because I generally enjoy it when artists break their own rules.

“In some of these works you can see traces of a human presence, such as a vapour trail from a jet streaking diagonally across the sky, or human footprints in the snow.”

We were sitting in front of a painting in which one mountain is suspended upside down above another. At first glance it looked like a weird marriage between Magritte and M.C. Escher. Like a duck-rabbit illusion, profiles of two faces appeared, formed from the mountains, in the likeness of the artist and his partner. It is called The Improbability of Love (2022, overleaf). He tells me, “It is a highly improbable landscape, and Sam and I have been happy together for an improbably long time.” The painting features prominently in his Benalla Art Gallery show. I ask him to give me a broad-brush description of what else features in the exhibition, and why.

“When Eric [Nash, Benalla Art Gallery Director] came to me with the idea for a show we thought that with Benalla being so close to the Victorian high country it would make sense to centre the show around my mountainscapes.

The show will also feature other landscapes and adjacent themes that I like to depict, such as highways, architecture, fauna and space. There will be 38 works in High Plains Drift All are from the last ten years, with the exception of four paintings from the early 2000s. The paintings are mostly based on photographs from my travels in Australia, New Zealand, Switzerland and Tibet. There are also some partly invented views of landscapes I’d like to visit, and wholly invented views of landscapes that do not exist.”

I ask if his working methodology sees himself oscillating between being a hermit and a nomad, and if he is comfortable with that?

“I am neither a nomad nor a hermit, but I am comfortable spending a lot of time by myself working in the studio. The occasional epic trip can supply enough inspiration to fuel my work for a long time afterwards2. When I travel, the majority of my time is spent exploring natural environments with maybe a day or two in a city to visit galleries and museums. I am fortunate that my partner Sam enjoys exploring landscapes and art galleries as much as I do.”

We returned to the revelations he’d had in Rome. He’d thought deeply about it once he got back to Australia. “I went from the ruins of buildings to the ruins of the earth’s crust, which of course is what mountains are; one of the greatest embodiments of time that we can see. What was once the ocean floor now touches the sky.”

As we make a close-up examination of the paintings, studying the markmaking process as much as what the marks depict, I ask about his studio technique. His answer is workmanlike and to the point.

“I begin by locating the lightest and darkest parts of the composition on the canvas and then I paint from a photo on my iPad, blocking out the image in focused areas, zooming in to the screen as I require more detail. The larger canvases can take about two months to complete, but I sometimes work on more than one painting at a time.”

If this sounds over-mechanical, it also gives the lie to the fact that the painting surface is both lush and sensitive. He inhabits a painterly space between Caravaggio, Ingres and Gerhard Richter3. This aesthetic takes him back to a life-changing trip he made to New York while still

a student at RMIT in the 1990s. One of the artists who made the biggest impact on him was Ed Ruscha, exhibiting at Gagosian Gallery. But it was not for the mountain paintings that the Californian has become known, as we shall see in a moment.

“The paintings by Ruscha that excited me most looked like film stills. They depicted silhouetted shadows of elephants and wolves and trees, and the monochromatic palette and slightly blurred image gave the paintings a dreamy feel. These paintings seemed to powerfully embody the old adage of ‘less is more.’ The lesson I took from them was to strip back my own compositions, take out the anecdotal details and to focus on the elemental structure of the image and the atmosphere it generated.”

And what of the mountains?

“I have to admit that I am not as taken with Ruscha’s mountain paintings. They are powerful paintings from a distance, but up close you see that the paint is not applied with the same care as his cinematic works. Andy Warhol was once asked, ‘What makes a painting beautiful?’ to which he replied, ‘That’s easy, it’s the way the paint is put on.’ The artists whose work

made me want to paint mountains were Caspar David Friederich and Eugene Von Guerard. They knew what would make a powerful image and how to put the paint on beautifully.”

By one of those delightful coincidences, as I am writing this essay, I am also working on a profile of the Scottish-born painter Peter Doig who has lived and worked at different times in Canada, Trinidad, and London. Like Tony, he is a frequent painter of mountains and snow. As I write, his exhibition of monumental new work opened last week at London’s Courtauld Galleries. The reviews are just starting to come in. This comment from Laura Gascoigne: “Only in Alpinist (2019–22) – a postmodern spin on the sublime with its lone skier in a harlequin suit – does he pull out all the old painterly stops in evoking the snowy slopes patterned with pines…”

Tony and I spoke at length about this over-used phrase ‘the sublime’ and how he definitely did not want the human element of it to be central, or even tangential, to his canvases.

“I am always disappointed to see tiny figures in the foreground of sublime landscape paintings. Their presence prevents me from feeling

fully immersed in the image. It also makes the scene seem smaller to me, the picture becomes the tiny figure’s story rather than a place of potential narrative into which the viewer can project their own stories. A ‘point of view’ shot in cinematography is when you see through the protagonist’s eyes, and momentarily you become the protagonist. And if you are looking at an unpopulated landscape, you are potentially the only person in that world. I use this perspective as a way of heightening the emotional experience of landscape.”

Dr Peter Hill Artist, writer, and independent curator. Dr Peter Hill is an Enterprise Professor at University of Melbourne (VCA)

Endnotes

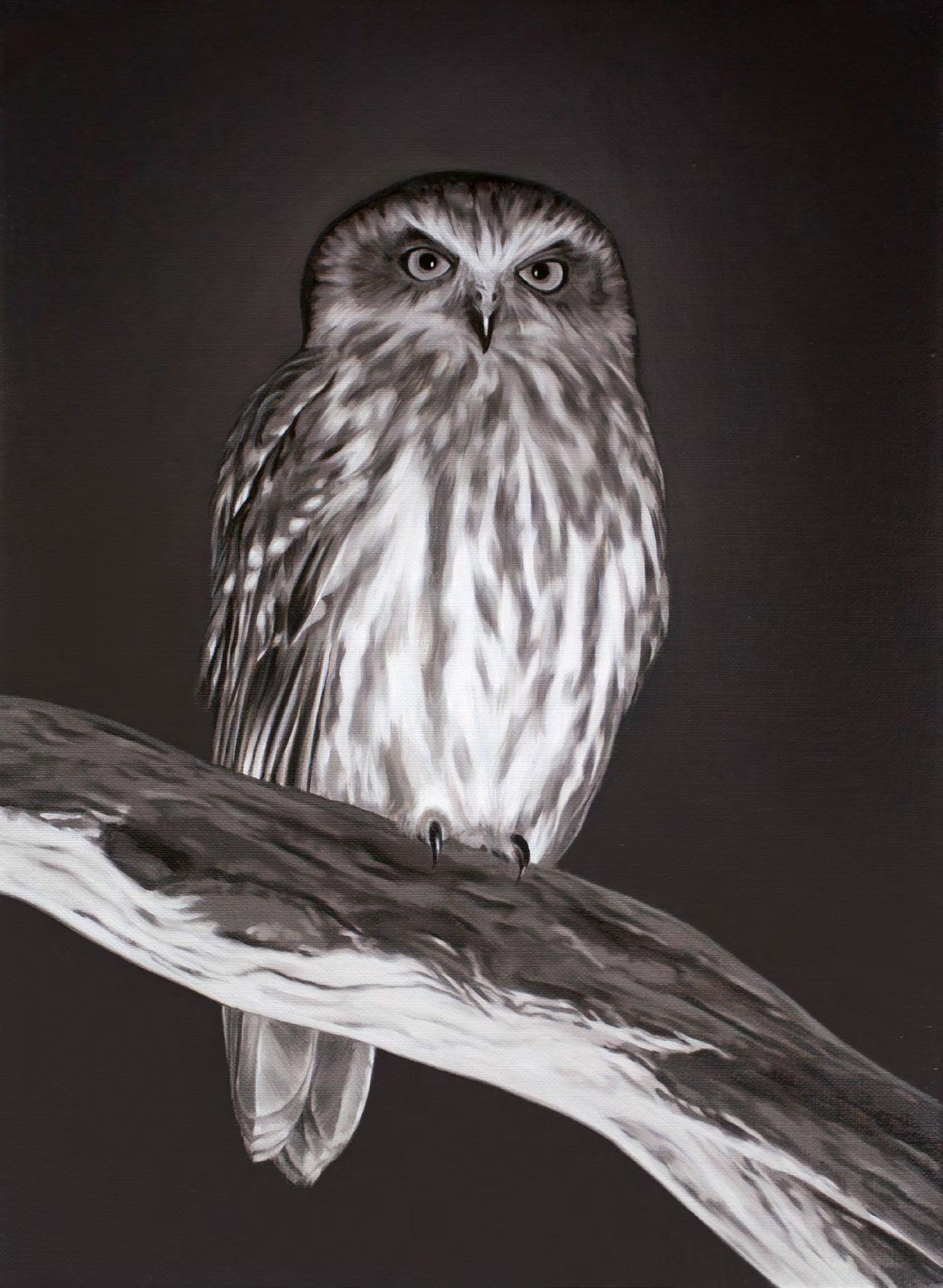

1. Other subjects include, but are not limited to: Cosmonauts, planets, owls, rhinos, night highways, meteorites, electrons, portraits (David Hicks, for example), film quotations (Un Chien Andalou, Night of The Hunter)

2. Some of his wildest trips have been in the company of his friends Sam Leach and Ashley Crawford, with whom he instigated the never-to-be-missed NotFair art fair, in Melbourne

3. He once spent months reverse-engineering Richter’s oil-painting techniques to find out what the magic material was. It turned out to be oil of cloves

High Plains Drift brings together for the first time a selection of my paintings from the past two decades. During this time I have painted hundreds of pictures and participated in over sixty exhibitions in Australia, Europe and Asia. This presentation of thirty-eight works focuses on the landscapes in which I love to immerse myself; it is also an overview of many of the themes I explore in my practice.

Every painting I make is a view of the world that I have actively sought out by watching the landscape and noticing how its character is transformed by light and time of day. This sometimes involves climbing a mountainside at dawn and waiting for the sun’s rays to creep across a rock face, or scrambling over rocks at low tide when the angle of light reveals deep shadow lines on granite cliffs, or driving for hours along remote highways at night with a camera recording the view through the windscreen.

I use photographs as a guide when painting, my intention is to convey something of what it felt like to be in those places at those moments in time. Invariably the act of translating photography into paint suggests

new ideas to me and sometimes the most exciting thing is when a painting becomes an unanticipated expression of the original idea.

I would like to thank Eric Nash and Benalla Art Gallery for this opportunity to show a more complete picture of the world I have been creating for years. I would also like to express my gratitude to Andy Dinan at MARS Gallery for her tireless work and enthusiastic support.

Tony Lloyd Artist

COVER IMAGE

Tony LLOYD

Pink Kailash [detail] 2019 oil on linen 46 x 61 cm courtesy of the artist and MARS Gallery