The Difficulties of Naming White Things

Eddie Chambers

Recently, the Kingston-based curator Petrine Archer-Straw and I had a series of e-mail exchanges that centered on the difficulties of naming white things. What, Petrine wanted to know, might be an appropriate name for the white equivalent of black memorabilia, black Americana, African Americana, and so on? Such material, utilizing the image of the black person in no end of guises—many of them decidedly problematic—existed in many places, from flea markets and antique malls through Internet auction sites. But what name might we assign to the white equivalent of such material? Lamely perhaps, I suggested memorabilia, though even as I sent the e-mail I knew the term was inadequate. Petrine eventually settled on a term that she felt might do the trick, but our exchange stayed with me as being a particularly instructive one. It seemed to me that there were things, and there were black things; there was history, and then there was black history; there was art, and there was black art. Simply put, white people did not need to prefix their stuff as white art, white history, white memorabilia, because history, art, memorabilia, and a host of other things carried with them, in the single unracialized or deracialized word, abundant references to, and presumptions of, whiteness and white people. In order for something to exist in contrast to these unnamed white things, they had to be labeled as black or some other such term signifying difference. In considering Kobena Mercer’s recent series—Annotating Art’s Histories—I am reminded of the frustration of not being able to call what generally passes as art history white art history, even though, with its consistent omissions and its partial accounts, that is what the universities

small axe 38 • July 2012 • DOI 10.1215/07990537-1665623 © Small Axe, Inc.

Small Axe Published by Duke University Press

of the country are by and large serving up within their art history departments. As a concession to diversity, a number of art history departments now have racially named Africanists, African Americanists, or African diasporaists—oftentimes thinly veiled references to black faculty. There is perhaps something of a circular argument at play here. University art history departments are oftentimes the embodiment of whiteness, albeit in an unnamed form. But to what extent is that complacency of unnamed whiteness troubled by the presence of one or several black faculty, whose specialist areas are invariably black art history? Black faculty and black art history exists, in part, to counter the dominance of whiteness and all that it invisibalizes. But black faculty and black art history invariably leave real (i.e., white) art history intact, untroubled, and, in many instances, happy to be decorated or adorned by a sprinkling of color or diversity. The key question is, of course, what might the alternative be? How can white art history be damned, troubled, questioned, interfered with, if not through the production of alternative narratives and the proffering of counterpositions? The bookshelves of this country’s university libraries are groaning under the weight of sloppy, partial, racially biased, white scholarship that masquerades as objective and canonical knowledge. How to disturb or affect that partiality, if not through the production of volumes such as these?

The hegemony within university art history departments is one in which what purports to be real art history takes priority. That is to say, the classic fields of art history such as

38 • July 2012 • Eddie Chambers | 187

Small Axe Published by Duke University Press

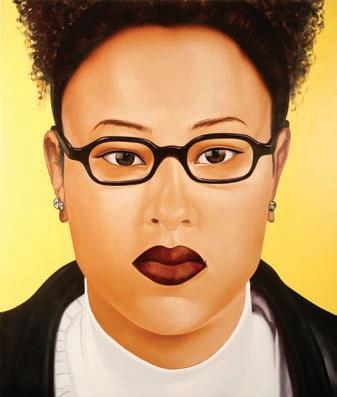

Ebony Patterson (b. 1981, Jamaica), Savilian Gaze, ca. 2004. Mixed media on paper, 48 x 108 in. Collection of Eddie Chambers.

Baroque, Roman, renaissance, Byzantine, medieval, and so on. These are the supposedly core disciplines or fields of enquiry around which the country’s major art history departments are built. In many universities, it is a struggle for even early modern art to have a foothold, much less art that is firmly located in the early, middle, and late twentieth century, and on into the new millennium. Invariably though, those professors whose areas of interest and teaching are African, African American, and African diaspora will be drawing from and looking at art practice of these twentieth- (and indeed, twenty-first-) century periods. This clash of the modern and the contemporary, versus real art history from way back when, points to what in some instances amounts to an uncomfortable and frequently unacknowledged racialized schism within art history and academia. Mercer’s four volumes—Cosmopolitan Modernisms; Discrepant Abstraction; Pop Art and Vernacular Cultures; and Exiles, Diasporas, and Strangers—underline and draw attention to that schism, consisting as they do of investigations into art practices that are decidedly twentieth century in their existences, thereby arguably rendering them peripheral, but tolerable as far as real art history is concerned.1

Within the historical body of investigation, research, and documentation around black artists’ practice, there exists the troubling issue of lack of context. Simply put, those academics and researchers, from James Porter onward, who have studied and presented material on African American artists, have tended to do so in ways that have quarantined or isolated the subjects from the concurrent wider art practice, at the time in which the artists studied were working. Time and again we have been denied the opportunity to look at generations of black artists’ work in a range of wider contexts. In that regard, the bulk of the alternative art histories that have been served up in the past by James Porter, David Driskell, Samella Lewis, Elsa Honig Fine, and Judith Wragg Chase, among others, necessary and valuable though they may have been, have ultimately existed as partial black versions of partial white texts. Of course, the partial white texts have obviously carried a great deal more weight, but even this should not detract from the ways black artists have consistently been decontextualized, and the ways this decontextualization has arguably further served to marginalize black artists rather than challenge their marginalization. Supposedly canonical and authoritative volumes of (white) art history have decontextualized their subjects by disregarding the work of black artists. It is possible to read no end of weighty tomes on “American art” from most any period without a single reference to Edward Mitchell Bannister, Robert Scott Duncanson, Henry Tanner, Rashid Johnson, Romare Bearden, Jacob Lawrence, Augusta Savage, or whichever black artists were practicing in the period these tomes related to. Simultaneously however, supposedly canonical and authoritative volumes of (black) art history have decontextualized their subjects by disregarding the work of white artists. It’s possible to read no end of weighty tomes on “black American art” from most any period without a single reference to Asher B.

1 Kobena Mercer, ed., Cosmopolitan Modernisms (2005); Discrepant Abstraction (2006); Pop Art and Vernacular Cultures (2007); and Exiles, Diasporas, and Strangers (2008). These volumes are part of the series Annotating Art’s Histories: CrossCultural Perspectives in the Visual Arts (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; London: Institute of International Visual Arts).

The Difficulties of Naming White Things 188 |

Small Axe Published by Duke University Press

Durand, Norman Rockwell, Andy Warhol, Winslow Homer, Thomas Eakins, and so on. In this sense, this corpus exists as a problematic black yang to an equally problematic (and much bigger) white ying. Refreshingly, within Mercer’s volumes, we are given invaluable opportunities to consider the range of subjects within contexts that have, previously, been largely unavailable to us. In this regard the books are invaluable in giving us substantial contexts in which to locate and consider the assorted topics.

The Annotating Art’s Histories series stands in marked and refreshing contrast to much of the scholarship—from whichever quarter—that preceded it. There is, though, one particular unfortunate consequence of this. That is, the volumes highlight not just how much previous scholarship has been shallow, reductive, or lacking; the volumes also highlight the enormity of the task of producing a more balanced, nuanced, textured art history that stands any chance whatsoever of countering the dominant body of scholarship from which plurality is excluded. (We can though, be assured that these volumes will positively supplement the previously alluded to works by the likes of James Porter, David Driskell, Samella Lewis, Elsa Honig Fine, Judith Wragg Chase, and so on. After all, those scholars, researchers, and others who acquired or read Modern Negro Art, Two Centuries of Black American Art, The Afro-American Artist, and Afro-American Folk Art and Crafts, and a host of other such volumes are very likely to be the sorts of people to read or acquire this series.2 Conversely, we can be assured that those university professors who set for their students such standard texts as E. H. Gombrich’s The Story of Art as course readings are unlikely to even know of, or be interested in, the existence of the Annotating Art’s Histories series.)

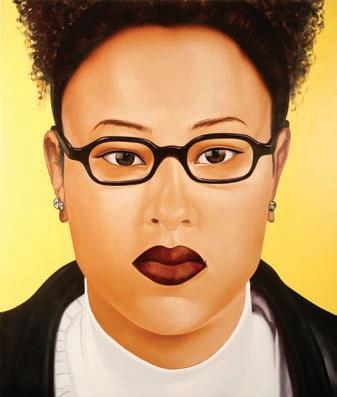

Eugene Palmer (b. 1955, Jamaica), Copy Series (One of Six), ca. 1999. Acrylic on canvas, 48 x 41 in. Collection of Eddie Chambers.

38 • July 2012 • Eddie Chambers | 189

2 James A. Porter, Modern Negro Art (Washington DC: Howard University Press, 1992); David C. Drikell, Two Centuries of Black American Art (Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1976); Elsa Honig Fine, The Afro-American Artist: A Search for Identity (New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1973); William R. Ferris, ed., Afro-American Folk Art and Crafts (Boston: G. K. Hall, 1983).

Small Axe Published by Duke University Press

When it comes to the artists, art, and subjects covered in this series, there is a virtually incalculably large amount of “stuff” that still needs to be researched, written about, and published. A measure of the enormity of the task can be ascertained by looking at the Guyananborn painter Frank Bowling. Half a century of consistent activity as a painter has produced for the artist no end of catalogues, from relatively modest affairs through to more substantial documentation. However, Bowling is only now the subject of his first monograph, published in 2011. This at a time when countless of his (white) contemporaries on both sides of the Atlantic have been the subjects of no end of published scholarship. There is a pronounced partiality that Mercer’s series seeks to counter, but in so doing, it throws into sharp relief the scale of what still needs to be done. (Bowling is in many ways, notwithstanding a lack of substantial scholarship on his practice, relatively fortunate. Within Britain there is a pronounced tradition whereby black artists have to wait until they are dead to be the subjects of major publications and major scholarship.) Bowling’s Guyanese contemporary, Aubrey Williams, is a compelling case in point.

This posthumous historicizing and recognizing black artists has become an aspect of the British art world’s strategy for dealing with black artists. Nowhere has this been more visible, more opportunist, and more naked than Tate Britain’s muddled attempts to engage with black artists, by, among other things, seeking to posthumously incorporate them into narratives of British art. This was certainly the case for Aubrey Williams.

Williams was born in Georgetown, British Guiana’s capital, in 1926. After settling in London in his late twenties, he enrolled at St. Martin’s School of Art and soon thereafter established a career as a prolific and widely exhibited artist. An active member of the Caribbean Artists Movement, Williams came to be closely associated with the presence of Caribbean art and artists in London, and his work was featured in a significant number of Caribbean art exhibitions as well as other group and solo shows.

A passionate believer in humanity’s art and culture in its many and varied forms, Williams was responsible for a substantial body of work and his paintings have latterly found their way into a number of important collections, including that of the Arts Council. It might in some ways be difficult to characterize Williams’s work, as the work for which he is perhaps best known and celebrated contains both figurative and nonfigurative elements. On the one hand, his paintings reflected his interests in such things as aboriginal South American culture, cosmology, and the music of the Russian composer Dmitri Shostakovich. On the other hand, his work also declared an interest in form, shape, color, and composition. London-based critic Guy Brett, a longtime admirer of Aubrey Williams’s work, noted, “Williams’ paintings fluctuate between representational references and abstraction.”3 Alongside such paintings

3 Guy Brett, “A Tragic Excitement: The Work of Aubrey Williams,” in Aubrey Williams, exhibition catalogue (London: INIVA, 1998), 24; published in conjunction with the Aubrey Williams retrospective at Whitechapel Art Gallery, London, 12 June–16 August 1998.

The Difficulties of Naming White Things 190 |

Small Axe Published by Duke University Press

exist Williams’s sensitive and faithful renderings of bird life. In his concluding remarks in one of his essays on Williams, Brett cautions against the instinct to typecast Williams’s practice:

It may be futile to try to explain painting. But it is also true that merely to name a motif in Williams’ painting as “pre-Columbian” or Mayan does not suggest the complicated life it leads in its changed form within his work, where it moves between past and present, between natural and artificial beauty, between excitement and warning. To grant Aubrey Williams’ paintings their enigma only awakens one to their links with the actual, contemporary world.4

In 1986, UK filmmaker Imruh Caesar made Mark of the Hand, a documentary that looked at the life and work of Williams, who as mentioned was a major force among Caribbean artists living and working in the United Kingdom during the second half of the twentieth century.5 The film followed Williams as he left his home in London and returned to his native Guyana to restore one of his murals, located on an outside wall of the capital’s airport terminal building, to be honored for his contributions to art and culture by the Guyanese government, and to make a journey deep into the country’s interior to revisit the places and the indigenous people he knew and worked among before he left Guyana. As much as anything else, the film was a look at the consequences of relocation, migration, memory, and return, and the difficulties and disappointments that can come from these things. Further to this, Mark of the Hand gave valuable insight into Williams’s strikingly original practice as a painter whose work was frequently, but by no means exclusively, characterized by the range of figurative and nonfigurative elements referred to earlier. The film was a pioneering work, and to this day sympathetic and sensitive documentary film studies of black British artists, such as Mark of the Hand, remain a rarity. One hugely important aspect of the film is the exploration of Williams’s respect and fondness for the indigenous peoples of the Guyanan interior. In this regard, the film positively complicates and challenges assumed notions of Caribbean identity.

Williams arguably still does not occupy a significant position in the declared history of British postwar painting. He himself recounted the despondency he felt upon realizing that his position in the British art world was perhaps more marginal than he would have liked:

But then, after two years all my shows were ignored. I began to ask myself what was wrong with me, what was wrong with my work. For the next five years I was in a terrible confusion. You know, I thought I had hit the level which would see me through both economically and respectably as a recognized artist in the British community.6

Two years before Williams died in 1990, Guy Brett wrote, with barely concealed frustration, of the “glaring injustice that Williams’s work was ignored and invisible in the country, Britain,

4 Guy Brett, introduction to Aubrey Williams, exhibition catalogue (Tokyo, 1988), n.p.; published in conjunction with the Aubrey Williams exhibition at Shibuya Tokyu Plaza, Japan, 1988.

5 The Mark of the Hand: Aubrey Williams, dir. Imruh Bakari (London: Arts Council/Kuumba Productions), color, 16mm, 52 mins.

6 Aubrey Williams, quoted in Rasheed Araeen, ed., The Other Story: Afro-Asian Artists in Post-War Britain, exhibition catalogue (London: Hayward Gallery/South Bank Centre, 1989), 111; originally quoted in Rasheed Araeen, “Conversation with Aubrey Williams,” Third Text, no. 2 (1987–88).

38 • July 2012 • Eddie Chambers | 191

Small Axe Published by Duke University Press

where he has lived for nearly 40 years, as if it could not be compared with the work of his ‘English’ contemporaries.” Brett continued, in parentheses,

No work by Williams has ever been bought by the Tate Gallery—the national contemporary collection—despite the fact that he has lived in Britain since the early ’50s. There has therefore never been the opportunity to compare his handling of abstraction directly with his contemporaries like Davy, Lanyon, Hoyland, Hodgkin: such comparisons would be revealing artistically, and socially, but we have been continually denied them.7

Within a couple of years of Williams’s death however, the Tate had incorporated Williams, now describing him as

an important British artist who responded to American abstract art when it was first shown in London in the 1950s. Williams immediately took on board the expressive power of the mark, as seen in the works of Jackson Pollock and Arshile Gorky. He married this style of painting with a palette forged in the equatorial light of his homeland British Guiana (now Guyana).8

Unable to interest the Tate in his work during his long career, Williams had a posthumous display at the Tate, consisting of a selection of his figurative and nonfigurative work, drawn from his estate. One of Williams’s most distinguished works from the early 1980s, Shostakovich 3rd Symphony Opus 20 (1981) was purchased by the Tate in 1993, some three years after his death. In September 2007, the Tate held an event titled “In Profile: Aubrey Williams,” to “reconsider [Williams’s] role and legacy in British art,” in which the gallery described him as “a key figure in the establishment of black visual culture in Britain and one of the founders of the Caribbean Arts Movement in the 1960s,” and posited that “his work and life continue to provoke debate, revealing as much about [his] work as about the cultural and political context in which it is viewed today.”9

The Tate was not the only major London gallery to accord Williams belated respect. In 1998, the Institute of International Visual Arts (Iniva), in association with Whitechapel Art Gallery, mounted the major exhibition Aubrey Williams, complete with a monograph that surpassed any publication on Williams’s practice produced during his lifetime.10 The major difficulty with these posthumous initiatives was that they were, arguably, by and large disingenuous, since they failed to acknowledge the ways the institutions involved, and others, had ignored artists such as Williams during their lifetimes. This perceived disingenuousness and revisionism on the part of institutions such as the Tate left unaddressed considerations

7 Guy Brett, “The Art of Aubrey Williams,” in Anne Walmsley, ed., Guyana Dreaming: The Art of Aubrey Williams (Sydney: Dangaroo, 1990), 97–100.

8 Tate Britain, “Collection Displays,” Aubrey Williams (past display), www.tate.org.uk/servlet/CollectionDisplays?roomid=4334 (accessed 25 March 2012).

9 In Profile: Aubrey Williams, 21 September 2007, Tate Britain, www.tate.org.uk/britain/eventseducation/coursesworkshops/ 9740.htm. “To coincide with a display of the artist’s archive, this study day brings together key critics, curators and artists including Guy Brett, Anne Walmsley, Dr Hassan Arero, Sonia Boyce, Dr Leon Wainwright, and film maker Imruh Bakari.”

10 Aubrey Williams, 12 June–16 August 1998, Whitechapel Art Gallery, London. Andrew Dempsey, Gilane Tawadros, and Maridowa Williams, eds., Aubrey Williams (London: Iniva/Whitechapel Art Gallery, 1998). Just over a decade later, Williams was again the subject of a major exhibition, complete with another substantial catalogue. Aubrey Williams: Atlantic Fire took place at Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool, January 2010–April 2010.

The Difficulties of Naming White Things 192 |

Small Axe Published by Duke University Press

of how an artist’s practice might have evolved under other, perhaps more favorable, circumstances. The ability to compare black artists’ work with their white contemporaries was a valid and important one that challenged the racial, ethnic, or cultural quarantining of certain visual practices. One of the texts in Discrepant Abstraction relates to Williams. It is “Black Atlantic Abstraction: Aubrey Williams and Frank Bowling,” written by Mercer himself. Within the text, Mercer (quoting from the Whitechapel exhibition catalogue) notes that “the Tate rejected an offer of Williams’ work by collector Dr Charles Damiano in 1961 and did not reverse its decision until the 1990s.”11 Notwithstanding this critical reference to the Tate’s indifference to Williams’s work during his lifetime, and notwithstanding that one-half of the subject of Mercer’s investigation, Frank Bowling, was very much alive and kicking, Mercer’s text makes no substantial mention of the shabby treatment meted out to Williams during his lifetime, preferring instead to offer a crafted and considered appraisal of particular aspects of work by these two giants of Guyanese art practice. But the material conditions of marginalization and invisibility under which so many black artists labor during their lifetimes cannot, in any reasonableness, be excluded from posthumous assessments of their practice, no matter how crafted, considered, and empathetic such texts might be. In this regard, curatorial, art historical, and critical attention paid to artists while they live and breathe is arguably of far greater importance and significance than that which is posthumously secured. In this regard, Rasheed Araeen’s “Conversation with Aubrey Williams” is of incalculable importance, coming as it did the greater part of two years before Williams’s death.12 We might, in similar terms, value and appreciate Imruh Caesar’s 1986 film Mark of the Hand. This is not to say that there is a wholesale absence of living artists from Mercer’s series. All sorts of contemporary artists—Bhupen Khakhar, Betye Saar, and David Hammons, among many others—are discussed in substantial essays that provide the reader with new information on these artists’ practices and seek to embed them and their work into weighty historical contexts. Again, however, we are brought back to considerations of what these books will do, and how they will function, within academia. They do of course have multiple validities beyond academia, but it is within an academic context—for both students and professors—that the series will have its biggest impact. Those of us who work in the realm of African diaspora art history—in my own case, with a particular emphasis on British-based art practice—are constantly faced with the curious, absurd, but sobering challenge of researching that which happened, in a manner of speaking, very recently. In 1977, a group of London-based black artists (including Sue Smock, an African American artist living in London at the time) sent/took an exhibition of their work to Festac ’77, a major international festival of arts and culture from the black world and the African diaspora. The artists were Winston Branch, Mercian Carrena,

11 Kobena Mercer, “Black Atlantic Abstraction: Aubrey Williams and Frank Bowling,” in Mercer, Discrepant Abstraction, 187; Mercer is quoting Anne Walmsley, “Chronology,” in Aubrey Williams, 75. Within Mercer’s corresponding footnote, the year of Williams’s 1998 Whitechapel exhibition is erroneously given as 1997.

12 Araeen, “Conversation with Aubrey Williams,” 25–52.

38 • July 2012 • Eddie Chambers | 19 3

Small Axe Published by Duke University Press

Uzo Egonu, Armet Francis, (Emmanuel) Taiwo Jegede, Neil Kenlock, Donald Locke, Cyprian Mandala, Ronald Moody, Ossie Murray, Sue Smock, Lance Watson, and Aubrey Williams. A small catalogue accompanied the exhibition. The introduction was written by the exhibition officer, Yinka Odunlami:

The works of artists from the United Kingdom and Ireland Zone who are represented in this exhibition as a substantial contribution to the 2nd World Black & African Festival of Arts and Culture are not just a collection of nostalgic frolic. They are an appreciation of artists originally from widely varying backgrounds; their present human, cultural and environmental conditions focus on the direction of their future development. The concept of black Art in this exhibition, whilst insisting on the unique contribution of traditional African Art to the general scene, is also committed to the projection of a new image based on the understanding of a common humanity, hope and struggle of people everywhere. It would therefore be wrong to brand this theme racial.13

This exhibition took place just a few years before a new generation of black British artists such as Claudette Johnson, Eugene Palmer, Denzil Forrester, and Mowbray Odonkor made such a dramatic contribution to art practice of the 1980s. Attempts to historicize or meaningfully assess black British artists’ practice of the 1980s have tended to fall flat for a number of reasons, though perhaps one of the most compelling has been a reluctance or inability to locate this practice within the context of that which came before it, as well as that which followed thereafter. In part, the isolation is a willful act, but in other ways, it reflects a profound not knowing: not knowing about what came before the 1980s, even though the mid-1970s to the early 1980s was in so many ways a blink of an eye. Black artists have been particularly susceptible to being excised from all manner of narratives, even, ludicrously, their own. We tend to know little to nothing about the London contribution to Festac ’77 simply because the exhibition has not been adequately recorded, cataloged, archived, or documented. Bluntly put, with so much of our history consigned to obscurity, sympathetic and competent art historians have much important work to do. Mercer’s series of books reminds us, and stands as an object lesson, of how much art history has yet to be excavated and created.

There is a wearying and hugely dangerous pathology in which that which is created by black people and black artists is deemed to be of less value or worth than that which is created by others. As mentioned earlier, the bookshelves of this country’s university libraries are groaning under the weight of sloppy, partial, racially biased, white scholarship that masquerades as objective and canonical knowledge. In large part, this mostly spurious sense of gravitas and canonical knowledge comes about through the implication that these books carry within their pages precious, valuable, worthwhile knowledge. By implication, that which does not exist has no value. Or, value is only assigned when that which does not exist is brought into

The Difficulties of Naming White Things 194 |

Small Axe Published by Duke University Press

13 Yinka Odunlami, introduction to Festac ’77: The Work of the Artists from the United Kingdom and Ireland, exhibition catalogue, n.p.

existence. This, in large measure, is the challenge facing historians of visual culture, whose areas of interest lie with and among black artists.

The Black-Art Gallery in North London was established in 1983 by Shakka Dedi and a close group of associates (who went by the acronym OBAALA).14 Under Dedi’s directorship, a significant number of black artists had their first London solo exhibitions, which came with catalogues, posters, opening view cards, press releases, and so on. In that regard, the gallery did much to present the work of a wide range of artists of African background and origin in a professional environment. Early exhibitions included ones by Keith Piper and Donald Rodney, among others. A passionate believer in the potential of “Black Art” to be a driving, guiding, and illuminating force in the lives and destiny of black (African, or Afrikan) peoples, Shakka Dedi and his colleagues created one of the first British manifestos of black art, which appeared in the catalogues accompanying several early exhibitions at the Black-Art Gallery, beginning with Heart in Exile, the gallery’s opening exhibition in the autumn of 1983.

For the next six years, the Black-Art Gallery was in a position to impact on the ongoing debate about the nature, relevance and validity of “Black Art” in Britain. OBAALA’s view of black art was to some extent a reworking of the black art manifestos offered ten to fifteen years earlier by the African American poets and prophets:

We believe that Black art is born of a consciousness based upon experience of what it means to be an Afrikan descendant wherever in the world we are. “Black” in our context means all those of Afrikan descent. “Art”; the creative expression of the Black person or group based on historical or contemporary experiences. Black-Art should provide an historical document of local and international Black experience. It should educate by perpetuating traditional art forms to suit new experiences and environments. It is essential that Black artists aim to make their art “popular”—that is an expression that the whole community can recognise and understand.

The gallery manifesto continued,

We also believe that artistic creativity should extend itself to functional and common usage artefacts (e.g. Household furniture and artefacts). Overall honesty should be the mark of Black-Art, Therefore it cannot afford to be elitist or pretentious. We believe that Black-Art can, should and will play a very important role in community education and positive development, and that it is by having their work recognized by the general community that Black artists draw their strength. OBAALA exists therefore, to stimulate and implement discussion and activity which will bring about the desired close relationship between consciousness, art and positive community development.15

One of the ways in which Dedi and his colleagues strove to maintain what they considered to be a clear position was in the naming of the gallery. While some artists and activists were starting to shy away from the term black art, Dedi mounted a spirited defense of the term by

14 OBAALA—Organization for Black Arts Advancement and Leisure Activity.

15 OBAALA Committee, “A Statement on Black Art and the Gallery,” in Heart in Exile, exhibition catalogue (London: Black-Art Gallery, 1983), 4.

38 • July 2012 • Eddie Chambers | 19 5

Small Axe Published by Duke University Press

calling his gallery space the Black-Art Gallery. This was not meant to be just a “black” gallery. It was meant to be a unique exhibition space, dedicated to the promotion of “Black-Art.”

Capital B, hyphen, capital A. The gallery refused to use or recognize any variation of this. The first exhibition organized and presented at the Black-Art Gallery, Heart in Exile, featured the work of twenty-two artists. Every one of them was of African Caribbean origin. For almost a decade, the gallery maintained its Afrikan Caribbean position and no other artists were exhibited there. Nonfigurative or abstract painting was conspicuously absent from the gallery exhibition program because such work could be seen as being “elitist or pretentious.”

Though the gallery had its detractors, for a period of a decade or so it made enormous—if not unproblematic—contributions to black British visual arts activity. The Black-Art Gallery received its core funding in large part from Islington Borough Council. When the gallery closed, its entire contents—archive material included—was simply junked or gotten rid of, to make way for the building’s new tenants. Islington Local History Centre, Finsbury Library, has no information relating to the Black-Art Gallery in any of its catalogues and indexes, thereby depriving local people, researchers, and others of information about what had been a hugely important initiative. A decade’s worth of catalogues, posters, press cuttings, and other documentation has simply and irreversibly disappeared. Time and again, black artists’ practice has found itself susceptible to the most brutal and oftentimes emphatic invisibalization, sometimes

The Difficulties of Naming White Things 196 |

Small Axe Published by Duke University Press

Charles Campbell (b. 1970, Jamaica), Two Ships, 1998. Oil on canvas, 18 x 28 in. Collection of Eddie Chambers.

within a very short space of time, between activity and obscurity. Perhaps this is what Mercer meant when, in another context, he wrote, “Without museums, collections, and institutions to preserve the materials of shared cultural history, the past is vulnerable to selective erasure—a symbolic threat that the cultures of the Black Atlantic diaspora have had to contend with from their inception.”16

Sensing, or appreciating, the enormity of the weight of white art history, many black British artists have made work that critiques or challenges the stifling and invisiblizing hegemony of that art history. Donald Rodney, Lubaina Himid, Yinka Shonibare, Georgia Belfont, Eugene Palmer, and others have taken to task the ways in which art history (as in, white art history) has either rendered black people peripheral or invisible as subjects within art history, or has discounted the contributions of black artists. In critiquing this art history, in assorted manifestations, these artists seek not so much to make work that stood outside of this history as to make work that critiqued that history, while simultaneously demanding for themselves a place within it. Much of this art practice has yet to be properly or adequately documented and written about, even though there is much we can learn from artists such as these, in their critiques of art history.

Returning to considerations of the tasks facing academics and researchers of black artists’ practices, ultimately the challenge must be to create art history that does more than compliment that from which it is excluded. Time and again, I find myself returning to the knotty question of the difficulties of naming white things (and by extension, the pitfalls of naming black things.) If that (art history) which is white and unnamed is central, then it follows that that (art history) which is black and named must, by definition, exist in some sort of peripheral or secondary space. How to get around this? Possibly the answer lies in how black things are named. Instead of Cosmopolitan Modernism, Discrepant Abstraction, Pop Art and Vernacular Cultures, and Exiles, Diasporas, and Strangers, perhaps the books’ titles should have been along the lines of Modernism, Abstraction, Pop Art, and so on. In laying claim to the center, and not the margins, the Africanists, African diasporaists, and African Americanists among us ought to learn from our (white) colleagues and follow their example of not naming themselves into a corner.

16 Kobena Mercer, “‘Diaspora Didn’t Happen in a Day’: Reflections on Aesthetics and Time,” in R. Victoria Arana, ed., “Black” British Aesthetics Today (Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars, 2009), 69.

38 • July 2012 • Eddie Chambers | 197

Small Axe Published by Duke University Press