THESIS CONTAINS CD/DVD

Wonder and Horror: An Interpretation of Lee Miller's Second World War Photographs as "Surreal Documentary"

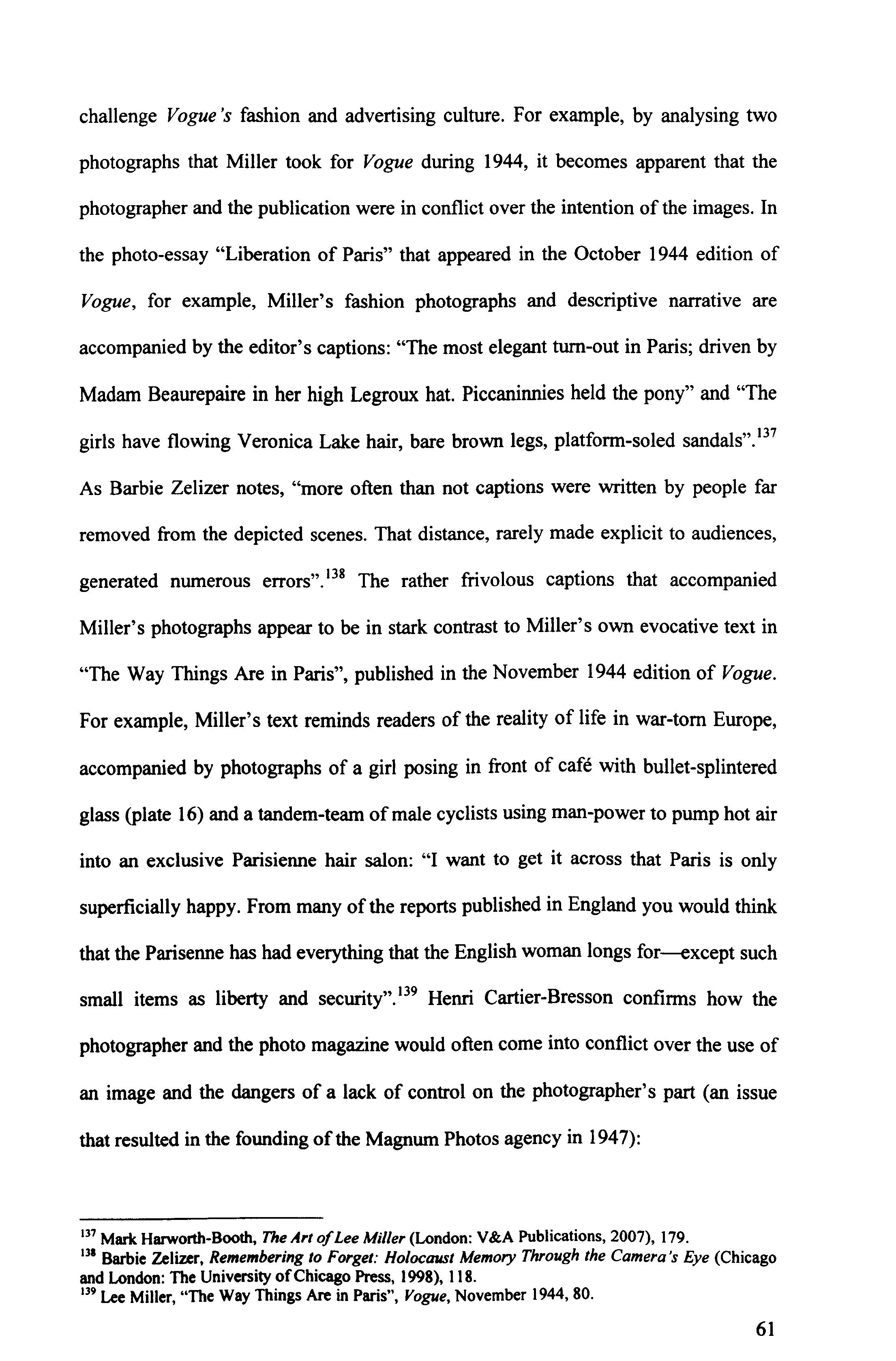

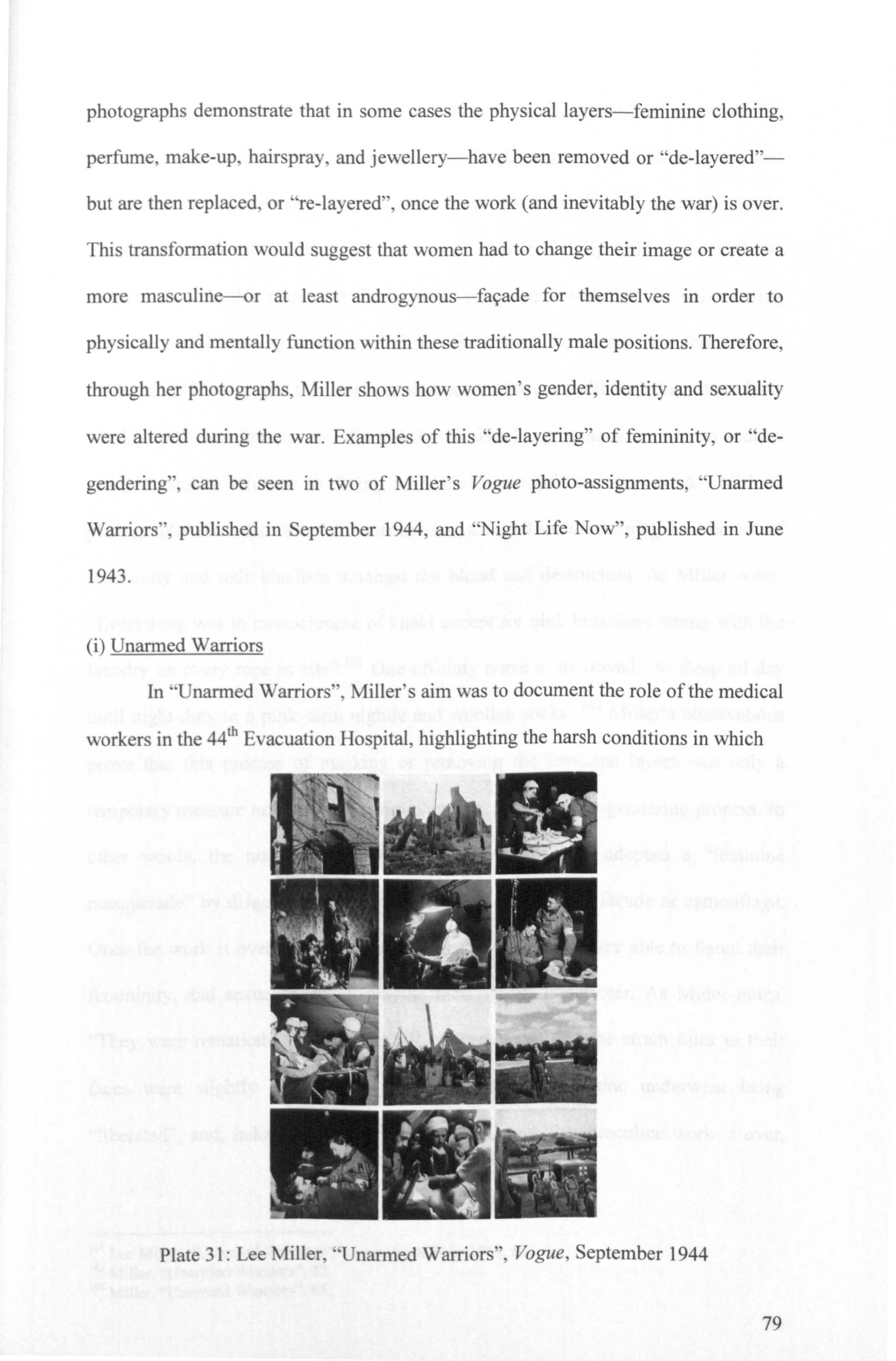

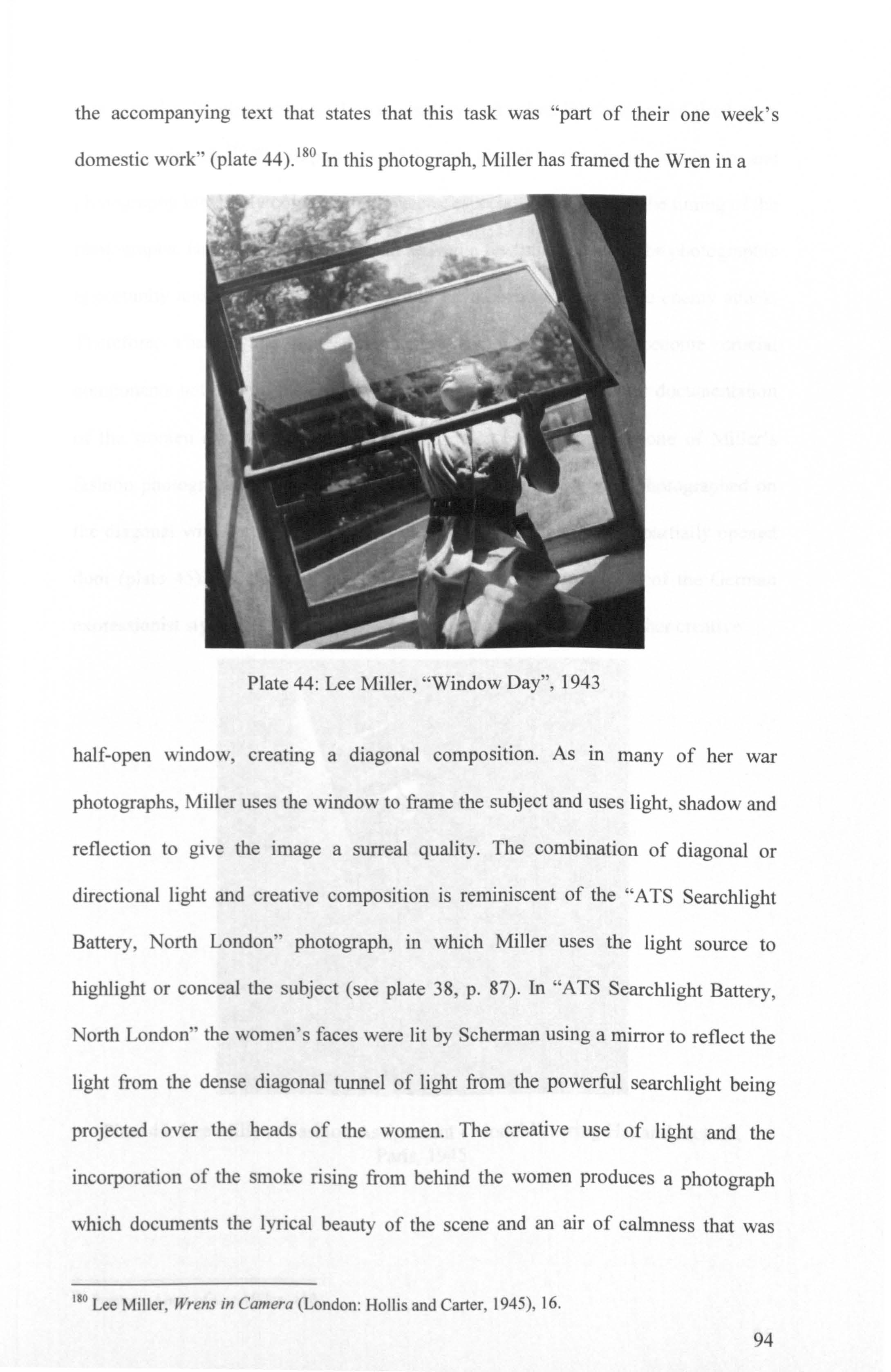

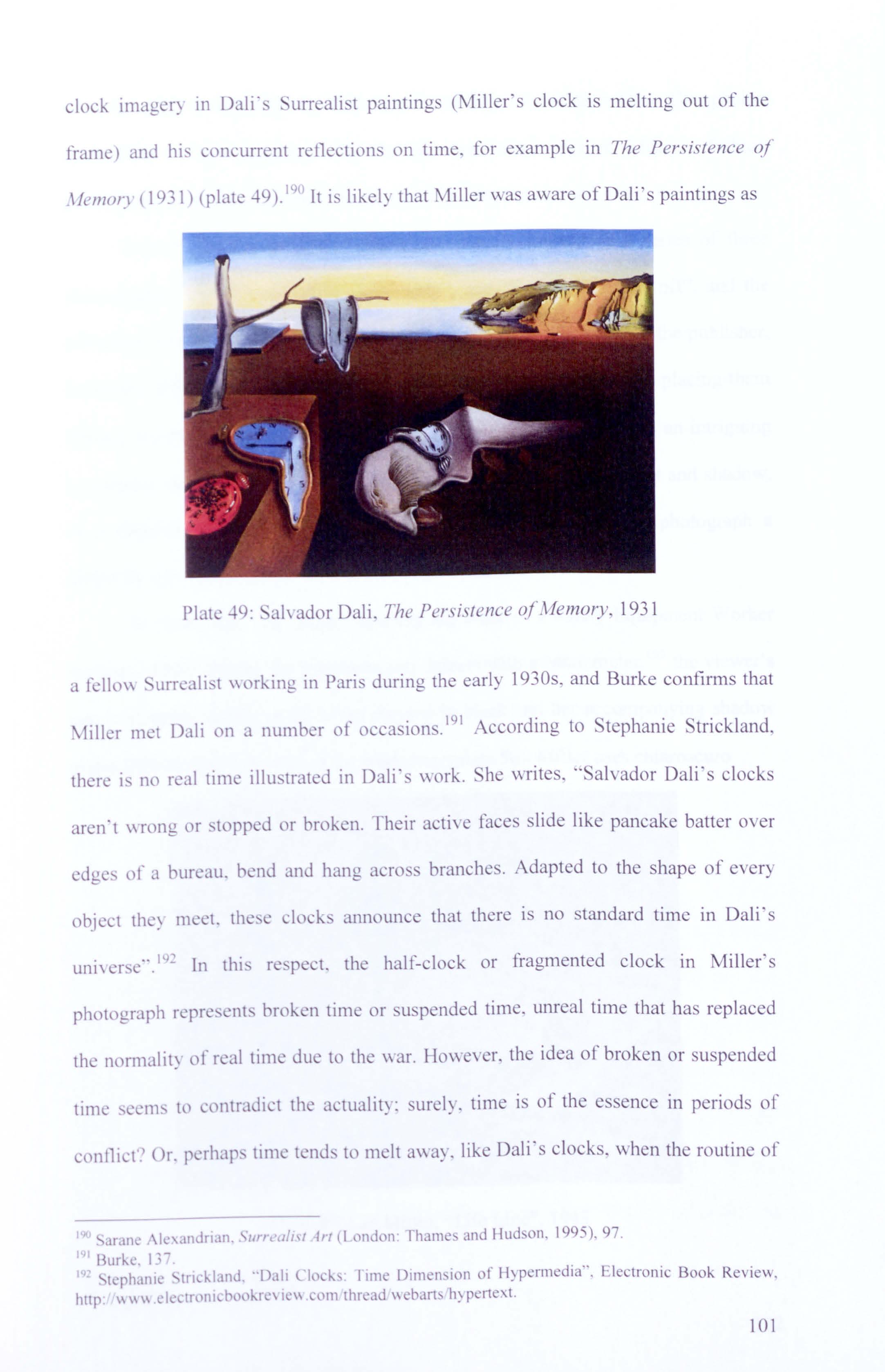

Lynn Hilditch

ABSTRACT

Lee Miller (1907-1977) was an American-born Surrealist and war photographer who became the apprentice of Man Ray in Paris and later one of the few women war correspondents to cover the Second World War from the frontline. Her in-depth knowledge and understanding of art enabled her to produce intriguing representations of Europe at war that embraced and adapted the principles and methods of Surrealism. This thesis examines how Miller's war photographs can be interpreted as visual juxtapositions of Surrealist devices and socio-historical reportage-or as examples of "surreal documentary". The methodology includes close analysis of specific photographs, a generally chronological study with a thematic focus, and comparisons with other photographers, documentary artists, and Surrealists, such as Margaret Bourke-White, Dorothea Lange, Walker Evans, George Rodger, Cecil Beaton, Bill Brandt, Henry Moore and Man Ray. In particular, Miller's photographs are explored using Andre Breton's theory of "convulsive beauty" and engaging with historical and cultural contexts.

Chapter One analyses a selection of Miller's wartime fashion photographs taken for Vogue magazine and images from her book Wrens in Camera (1945). Miller suggests a connection between art and war by capturing scenes with her camera reminiscent of Surrealist works by Rene Magritte, Henry Moore and Man Ray and uses her knowledge of Surrealism to provide an insightful commentary on the roles of women in fashion and war. Chapter Two explores Miller's photographs of the Blitz that were published in Ernestine Carter's wartime publication Grim Glory: Pictures of Britain Under Fire (1941). This collection of photographs illustrates Miller's aestheticisedreportage, or surreal documentary, displaying a creative interpretation of a broken city ravished by war. Not only do the photographs depict the chaos and destruction of Britain during the Blitz, they also reveal Surrealism's love for quirky or evocative juxtapositions while creating an artistic visual representation of a temporary surreal world of fallen statues and broken typewriters. In Chapter Three, Miller's war images are analysed within the context of Breton's theory of convulsive beauty, his idea that anything can be deemed beautiful, even the most disturbing or horrific of subjects, if convulsed, or willingly transformed, into their apparent opposite. In many of Miller's war photographs, particularly those taken at the Dachau and Buchenwald concentration camps, the disturbing nature of the subject illustrates the concept of convulsive beauty when Miller uses creative composition and form to transform the subject into an artistic representation of the horrors of war. The Epilogue concludes this thesis by considering the continuing value of Miller's war photographs and establishing how her photographs can be interpreted not only as examples of surreal documentary but also as "modern memorials"- important photographic documents that can be considered as aesthetically and historically-significant representations of war.

The analysis of Miller's photographs in these four chapters establishes how Miller, as a female, Surrealist photographer, was able to use her knowledge and understanding of art and art movements to juxtapose the concepts of the artistic (Surrealism) and the documentary (historical record) to create intriguing images of war through degrees of "wonder and horror".

ii

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Firstly, I would like to thank my supervisor at Liverpool Hope University, Dr. William Blazek, and my adviser at The University of Liverpool, Dr. Jonathan Harris, for their valued support, advice and guidance throughout the course of my research, and Dr. Neil Matheson at the University of Westminster for his additional advice on the aspects of Surrealism and documentary. I would also like to acknowledge Tony Penrose and the staff at the Lee Miller Archives in Chiddingly, East Sussex, who provided help and guidance during my research visits. Special thanks go to Michael Dunn FRPS, Martin Reece MBE ARPS and the members of The South Liverpool Photographic Society for their interest and encouragement during the past five years. Finally, I would like to thank my partner, Andrew Logan, and family for their love, support and understanding throughout the course of my research.

ill

CONTENTS Abstract Acknowledgements Contents List of Illustrations Page ii 111 iv V1 Introduction 1 Literature Review 6 Aims 13 Methodology 14 Key Concepts 18 i) Surreal Documentary 18 ii) Miller and Surrealism 25 iii) Bretonian Surrealism and "Convulsive Beauty" 27 iv) Chance and the Objet Trouve 31 a) Determined Chance 33 b) Accidental (Coincidental) Chance 35 v) Fragmentation, Polarisation and Juxtaposition 38 vi) Abjection 40 vii) Humour Noir 42 Structure 43 Chapter One: Women in War 47 Introduction 47 Women in Fashion, 1940-1944 49 i) Wartime Fashion in Vogue 52 Women in War, 1943-1945 78 i) Unarmed Warriors 79 ii) Wrens in Camera 90 Conclusion 111 Chapter Two: Grim Glory and the Aesthetics of Destruction 113 Introduction 113 The Grim and the Glorious 115 War's "Revenge on Culture" and the Concept of the "Fallen Woman" 125 Ancient versus Modem 147 A Surreal Humour (or Humour Noir) 157 A Blast from the Past 165 Conclusion 171 Chapter Three: Aesthetics of HorrorMiller's Photographs of Dachau and Buchenwald 175 Introduction 175 "BELIEVE IT" 177 Looking at War 180 Art and War 183 Composing the Horrors of War 191 iv

i) Applying Surrealist Practice 192 ii) SS Guard Portraits 208 The Concentration Camps as Subject for Art 214 Conclusion 227 Epilogue: Miller's War Photographs as "Modern Memorials" 230 Introduction 230 War Photographs as Modem Memorials 233 Miller's Photographic Legacy 245 Conclusion 263 Bibliography 266 V

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

Plates

Introduction

1. Unknown Photographer, "Lee Miller and Man Ray", circa 1930. Inscribed on reverse "For Lee-this souvenir-hoping we shall always see eye to eye. Love, Man". JaneLivingston, Lee Miller, Photographer (London: Thames and Hudson, 1989), 21.

2. Cecil Beaton, "London Bomb Damage", 1940. Ian Walker, So Exotic, So Homemade: Surrealism, Englishness and Documentary Photography (Manchester and New York: University of Manchester Press,2007), 151.

3. Walker Evans, "South Street, New York", 1932. Lloyd Fonvielle, Introduction to Walker Evans - Aperture Masters of Photography Number Ten (New York: Aperture, 1993), 17.

4. Pablo Picasso, Still Life with Chair Caning, May 1912. Oil and oil cloth on canvas with rope frame, 27 x 35 cm. Daix 466. Musee Picasso, Paris. Mark Harden, "Pablo Picasso: Still Life with Chair Caning", The Artchive, http: //www. artchive. com/ artchive/P/picasso/ chaircan.jpg. html.

5. Joseph Cornell, Untitled, circa 1949. Collage, 21.9 x 26.4 cm. Vivien Horan Fine Art, New York. Mark Haworth-Booth, The Art of Lee Miller (London: V&A Publications, 2007), 106.

6. Lee Miller, Untitled [Collage of Eileen Agar and Dora Maar], 1937. Collage, 24.5 x 17 cm. Lee Miller Archives. Katherine Slusher, Lee Miller and Roland Penrose: The Green Memories of Desire. Munich, Berlin (London, New York: Prestel, 2007), 42.

7. Man Ray, "Lee Miller", Paris, circa 1930. Solarised print, 23.3 x 18.8 cm. Lee Miller Archives. Haworth-Booth, 28.

8. Lee Miller, "Solarised Portrait of Dorothy Hill (Profile)", New York, 1933. Solarised print, 24.0 x 19.0 cm. Lee Miller Archives. Haworth-Booth, 95.

Chapter One

9. David E. Scherman, "Untitled [Lee Miller in Uniform]", London, 1944. Monochrome print, 25.5 x 20.2 cm. Lee Miller Archives. Haworth-Booth, 166.

10. Unknown Photographer, "Untitled [Lee Miller with Rolleiflex]", Egypt, 1935. Monochrome print, 13.6 x 9.0 cm. Lee Miller Archives. Haworth-Booth, 119.

11. Lee Miller, "Medium Price Fashion", London, June 1940. Photo Gallery, "Fashion", Lee Miller Archives, http: //www. leemiller. co.uk/imagedisp.aspx?id= 99&cat=7.

12. Lee Miller, "Women with Fire Masks", Downshire Hill, London, 1941. Modem Print by Carole Callow, 26.0 x 25.0 cm. Lee Miller Archives. Haworth-Booth, 150.

V1

13. Man Ray, "Noire et Blanche", 1926. Gelatin silver print, 15.7 cm (diameter). Private collection, Paris. Emmanuelle De 1'Ecotais and Alain Sayag, Man Ray (Corte Madera, CA: Gingko Press, 1998), 12.

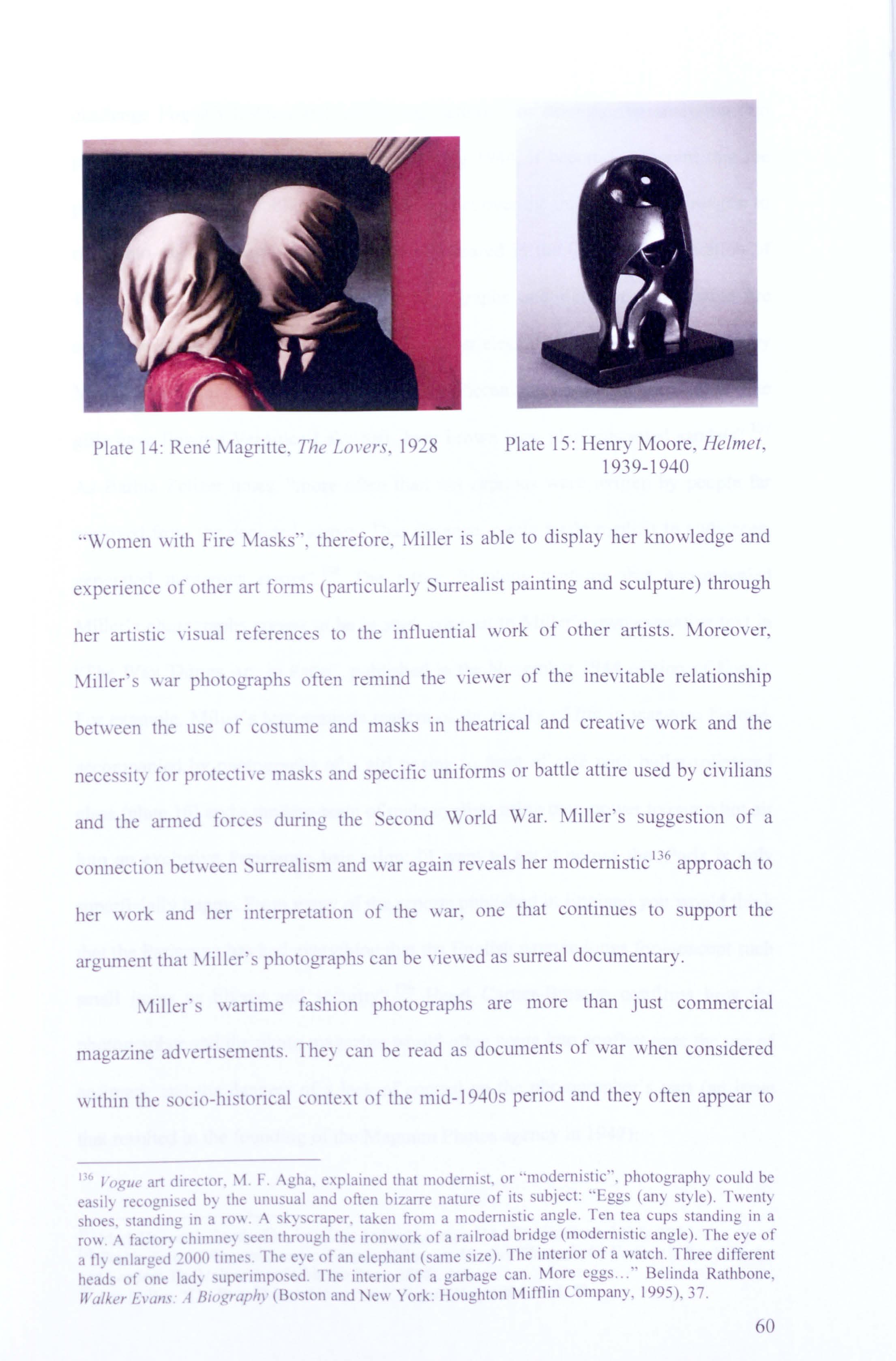

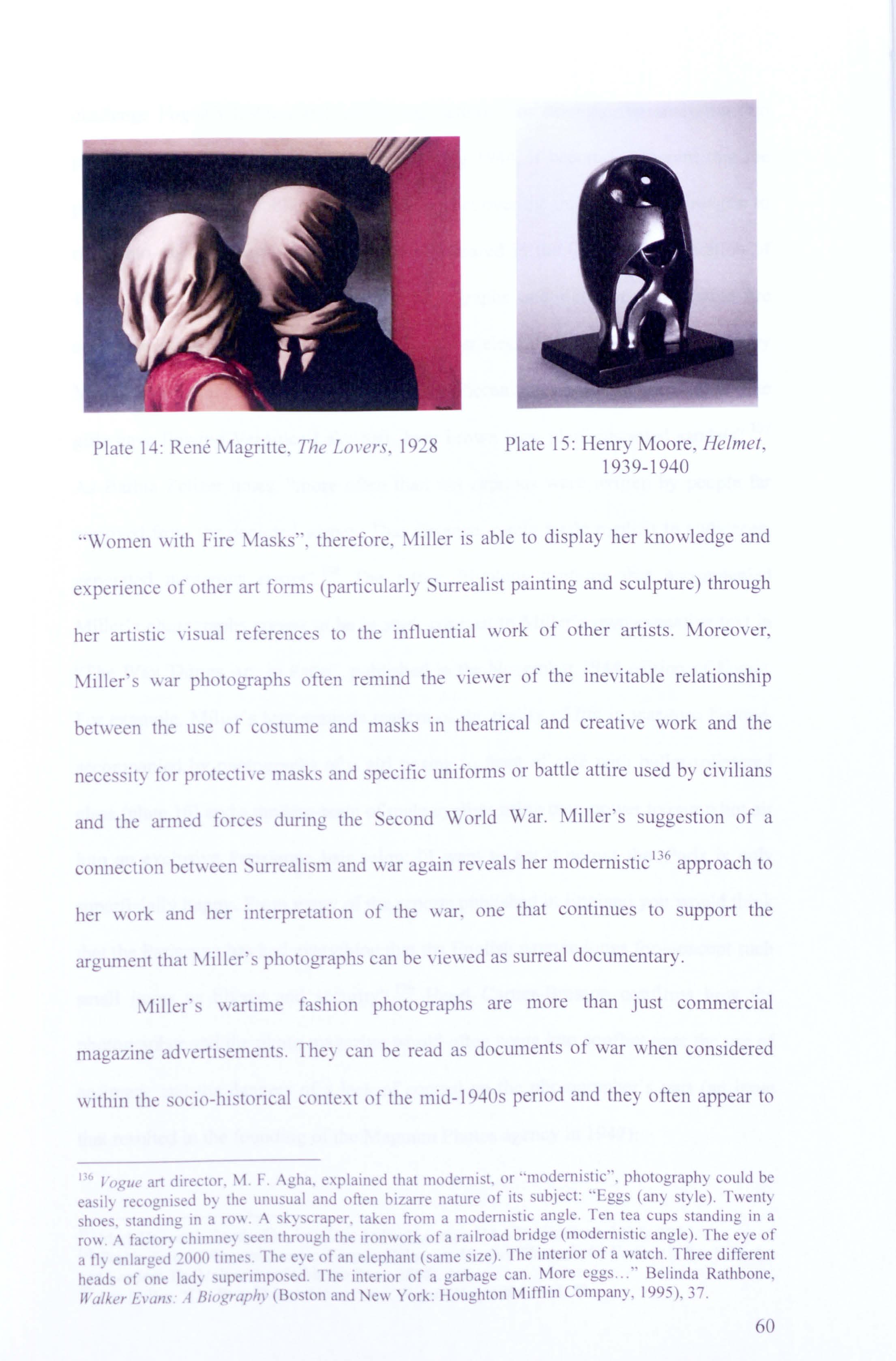

14. Rene Magritte, The Lovers, 1928. Oil on canvas, 54.0 x 73.4 cm. The Museum of Modem Art, New York. Jennifer Mundy, ed., Surrealism: Desire Unbound (Millbank, London: Tate Publishing, 2001), 86.

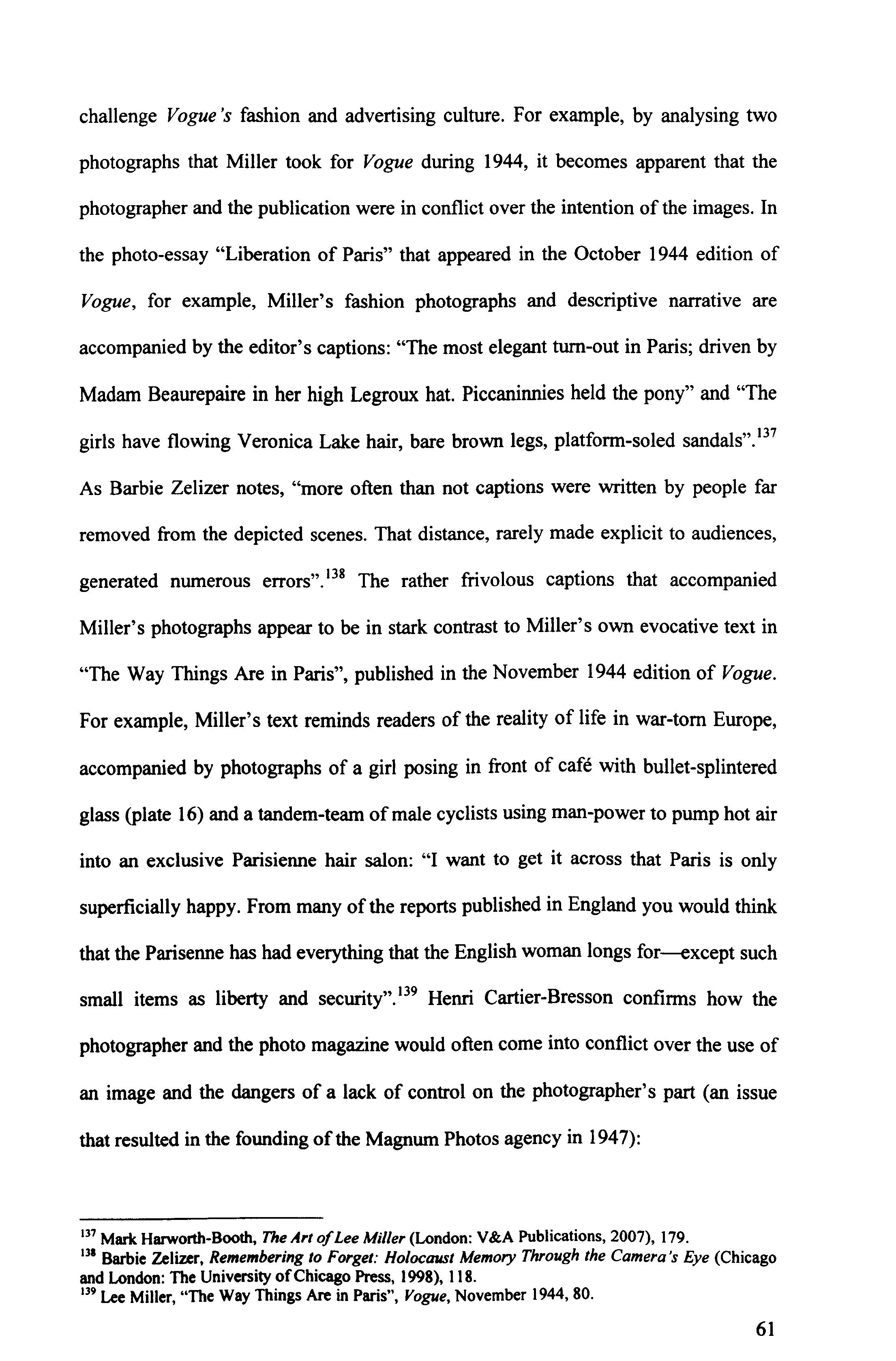

15. Henry Moore, Helmet, 1939-1940. Lead sculpture, 29.1 x 18 x 1605 cm (excluding base). Scottish National Gallery of Modem Art, Edinburgh. Antony Penrose, Roland Penrose and Lee Miller: The Surrealist and the Photographer (Edinburgh: National Galleries of Scotland, 2001), plate 56.

16. Lee Miller, "Mlle. Christiane Poignet, Law Student", Paris, 1944. Antony Penrose, ed. Lee Miller's War (London: Conde Nast Books, 1992), 68.

17. Lee Miller, "Models Relaxing Before a Fashion Show", Paris, 1944. Originally taken for "The Way Things Are in Paris", Vogue, November 1944. Penrose, Lee Miller's War, 82-83.

18. Lee Miller, "Henry Moore Sketching in Holborn Underground Station", London, 1943. Scene from the film Out of Chaos (Jill Craigie, 1944). Penrose, Surrealist and the Photographer, plate 80.

19. Lee Miller, "Model Preparing for a Millinery Salon, Salon Rose Descat", Paris, 1944. Andrew Nairn, ed. Wherever I Am: Yael Bartana, Emily Jacir, Lee Miller (Oxford: Modem Art Oxford, 2004), 70.

20. Auguste Rodin, The Thinker, 1880. Bronze and marble, 68.6 x 89.4 x 50.8 cm. Musee Rodin, Paris. Philadelphia Museum of Art, "The Thinker", Rodin Museum, http: //www. rodimnuseum.org/collection/103355. html.

21. Edward Steichen, "Rodin and The Thinker", 1902. Miles Orvell, American Photography (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2003), 86.

22. Lee Miller, "British Service Women at a Fashion Salon", Paris, 1944. Originally taken for "Liberation of Paris", Vogue, October 1944. Penrose,Lee Miller's War, 81.

23. Lee Miller, "Paquin's Navy-blue Woollen Dress, Place de la Concorde", Paris, 1944. Originally taken for "Liberation of Paris", Vogue, October 1994. Penrose, Lee Miller's War, 83,

24. Man Ray, "Blanc et Noir", circa 1929. Gelatin silver print, 11.1 x 7.2 cm. Centre Georges Pompidou. De L'Ecotais and Sayag, 94.

25. Lee Miller, "Untitled [Severed Breast from Radical Mastectomy]", Paris, circa 1930. Two photographs, left: 8.5 x 5.5 cm, right: 7.6 x 5.5 cm. Lee Miller Archives. Haworth-Booth, 89.

26. Frederick Sommer, "Untitled [Amputated Foot]", 1939. Trimmed 10 x8 inch contact print. Trustees of the Frederick and Frances Sommer Foundation, "Galleries",

vii

The Frederick and Frances Sommer Foundation, http: //www. fredericksommer. org/index. php?category_id=11&gallery_id=12 5&piece_id=104 5.

27. Lee Miller, "Gruyere's Quilted Windbreaker Outside the Bruyere Salon, Place Vendome", Paris, 1944. Modern print by Carole Callow, 26.0 x 25.0 cm. Lee Miller Archives. Haworth-Booth, 182.

28. Man Ray, "Leebra", Paris, circa 1930. Antony Penrose, The Lives of Lee Miller (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1985), 27.

29. Lee Miller, "Untitled [Eiffel Tower]", Paris, October 1944. Livingston, Lee Miller, Photographer, 72.

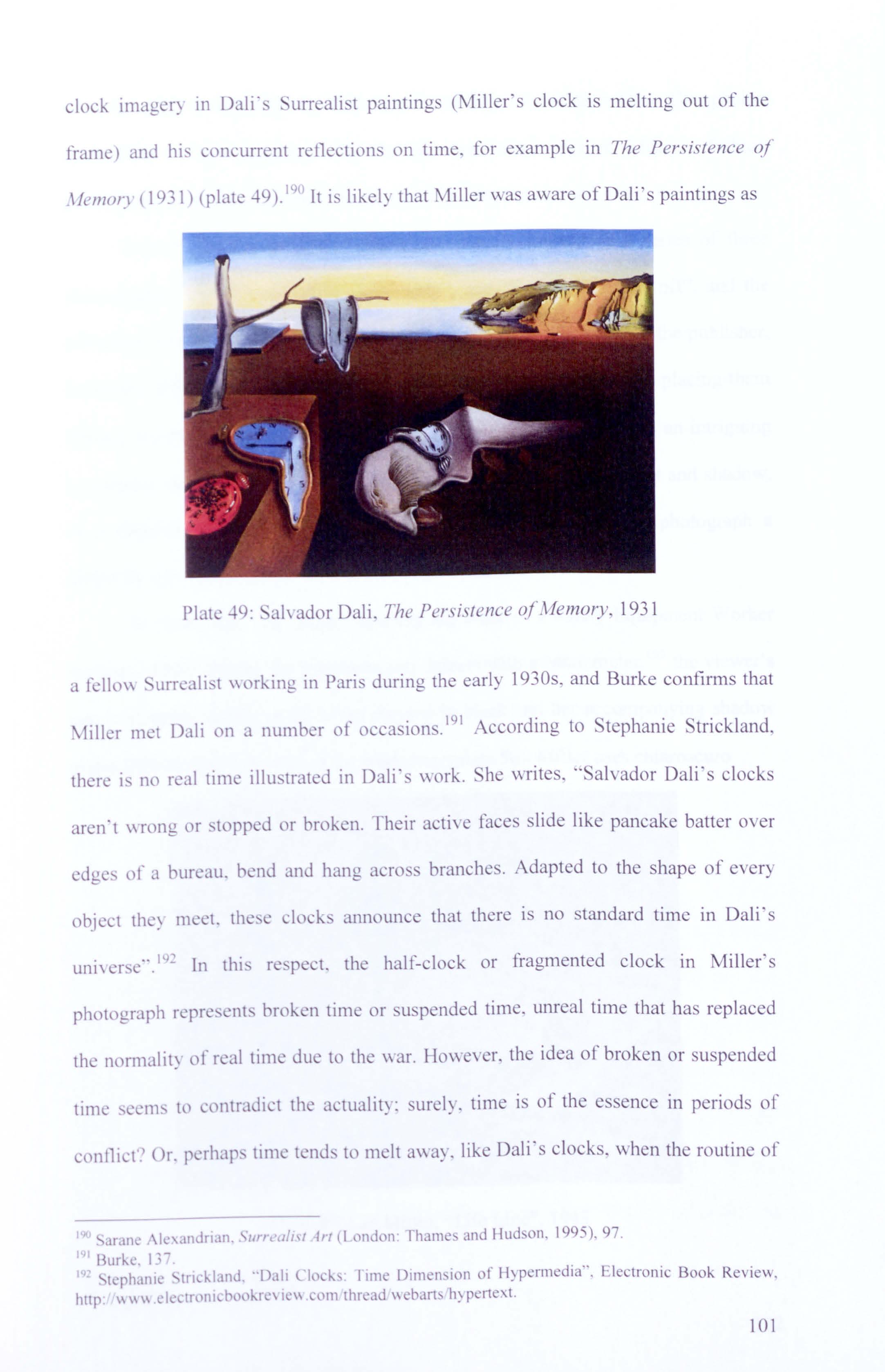

30. Lee Miller, "Untitled [Eiffel Tower]", Paris, October 1944 (cropped version). Lee Miller, "Liberation of Paris", Vogue,October 1944. Haworth-Booth, 178-179.

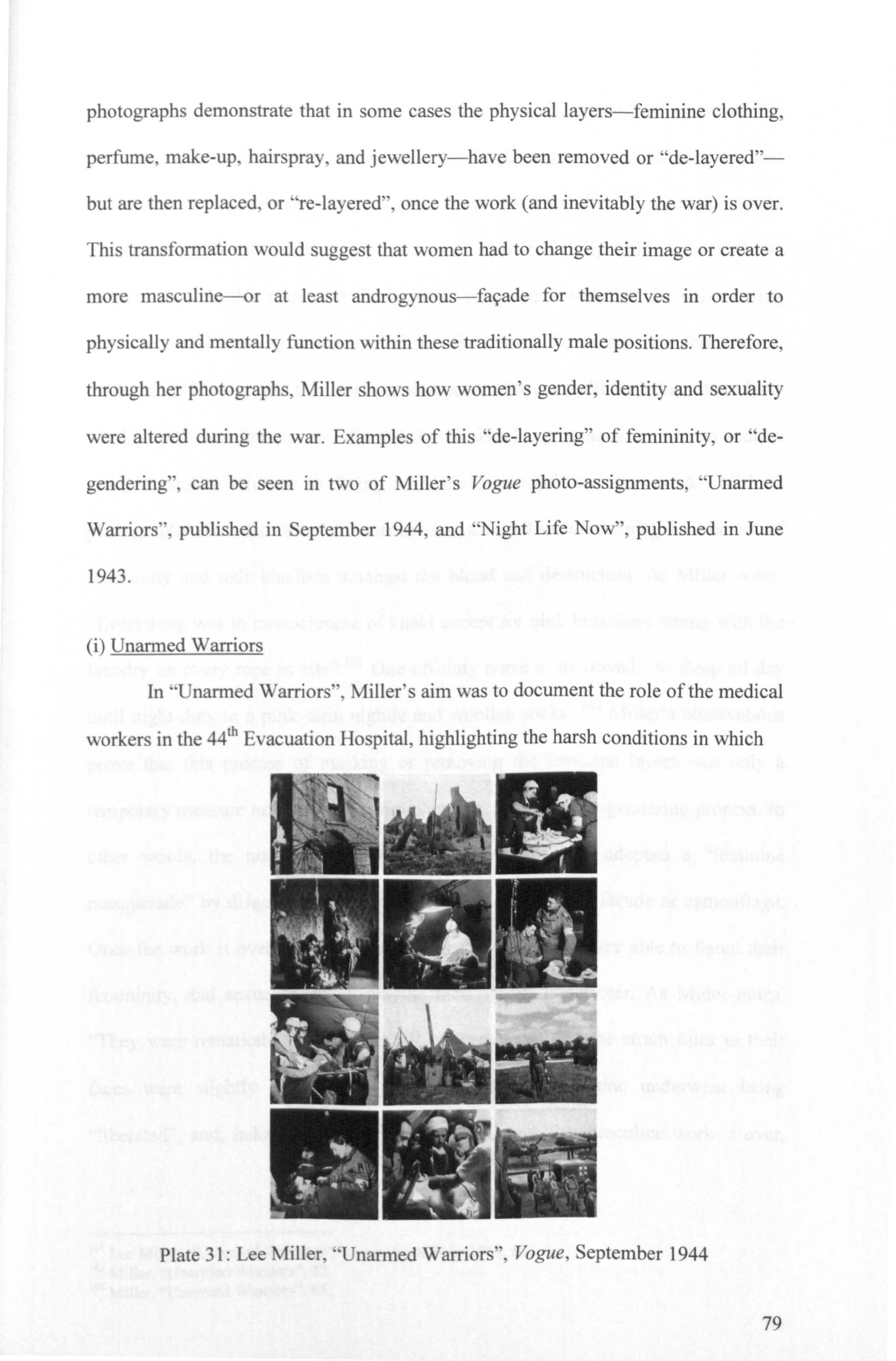

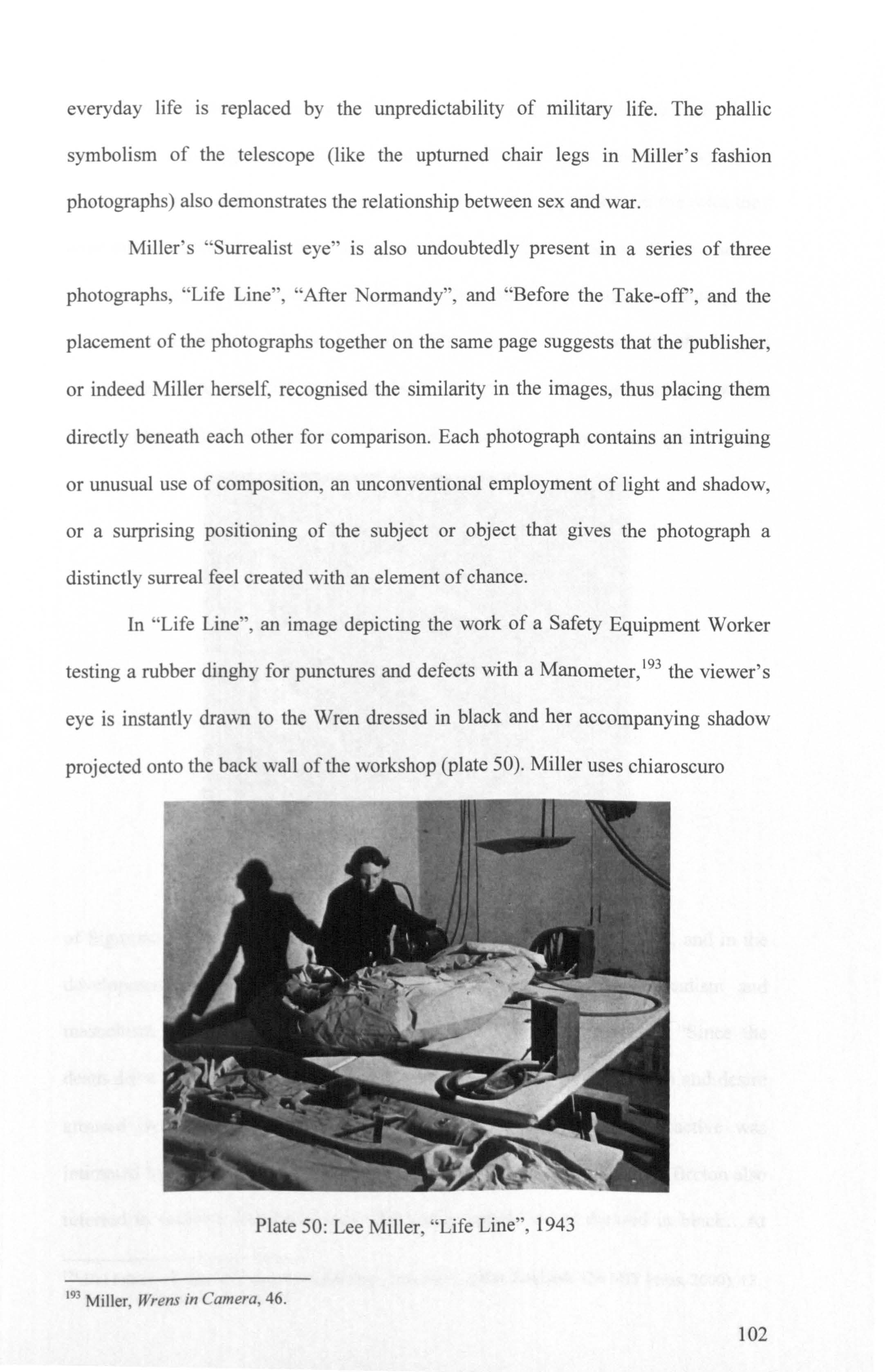

31. Lee Miller, "Unarmed Warriors", Vogue,September1944,37.

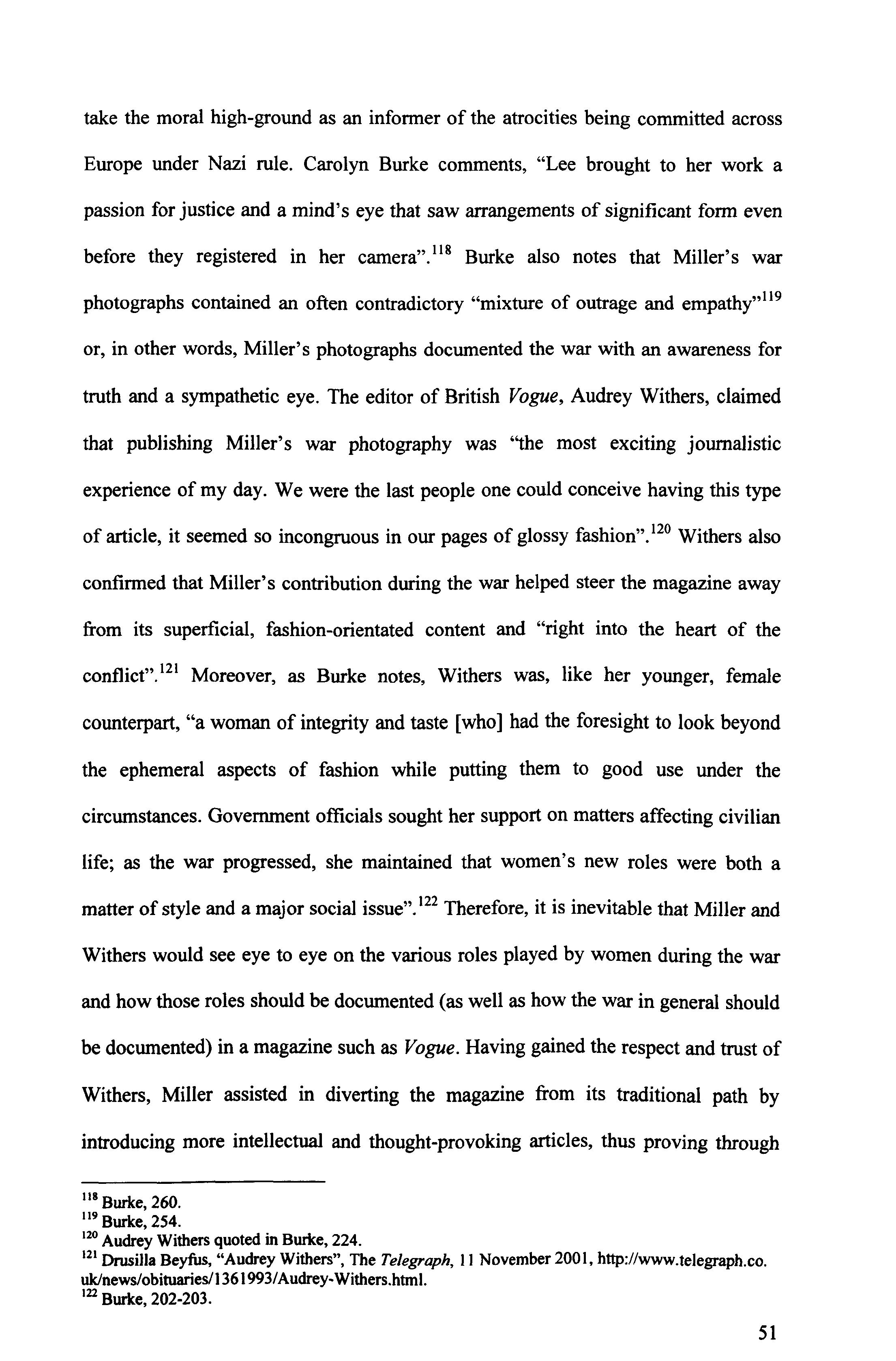

32. Lee Miller, "US Army Nurse's Billet", Oxford, 1943. Lee Miller, "American Army Nurses", Vogue, May 1943. Richard Calvocoressi, Lee Miller: Portraits from a Life (London: Thames and Hudson, 2002), 87.

33. Lee Miller, "Nurse, Exhausted After a Long Shift, 44th Evac.", Normandy, 1944. Originally taken for but not used in the photo-essay, "Unarmed Warriors", Vogue, September 1944. Penrose,Lee Miller's War, 20-21.

34. Lee Miller, "Off-duty Nurses Relaxing, 44th Evac. Hospital", Normandy, 1944 (original landscape format). Nairn, 68.

35. Lee Miller, "Off-duty Nurses Relaxing, 44`h Evac. Hospital", 1944 (cropped version). Originally taken for but not used in the photo-essay, "Unarmed Warriors", Vogue, September 1944. Penrose,Lee Miller's War, 24-25.

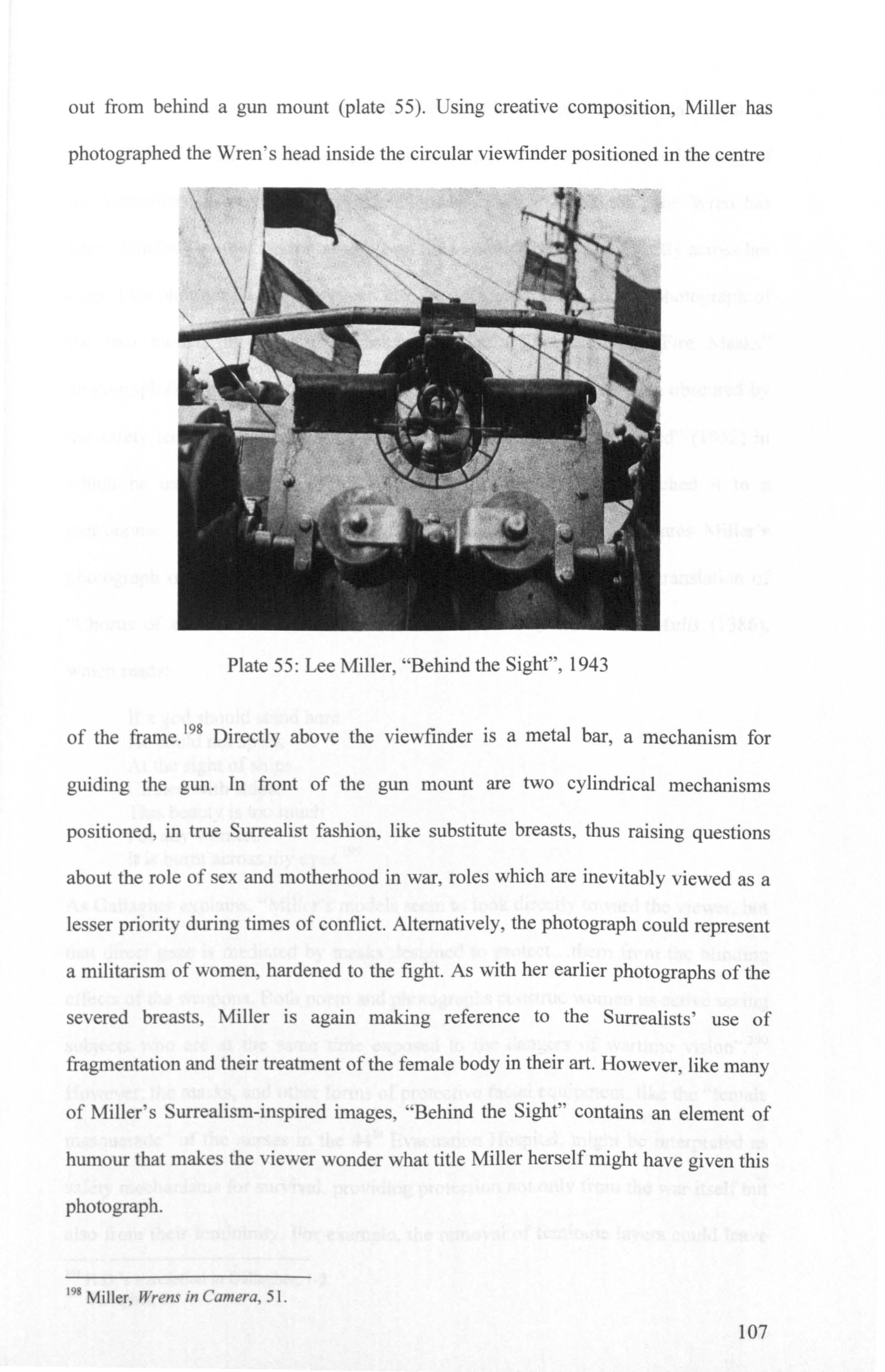

36. Lee Miller, "Paris Fashions", Vogue,November 1944,39.

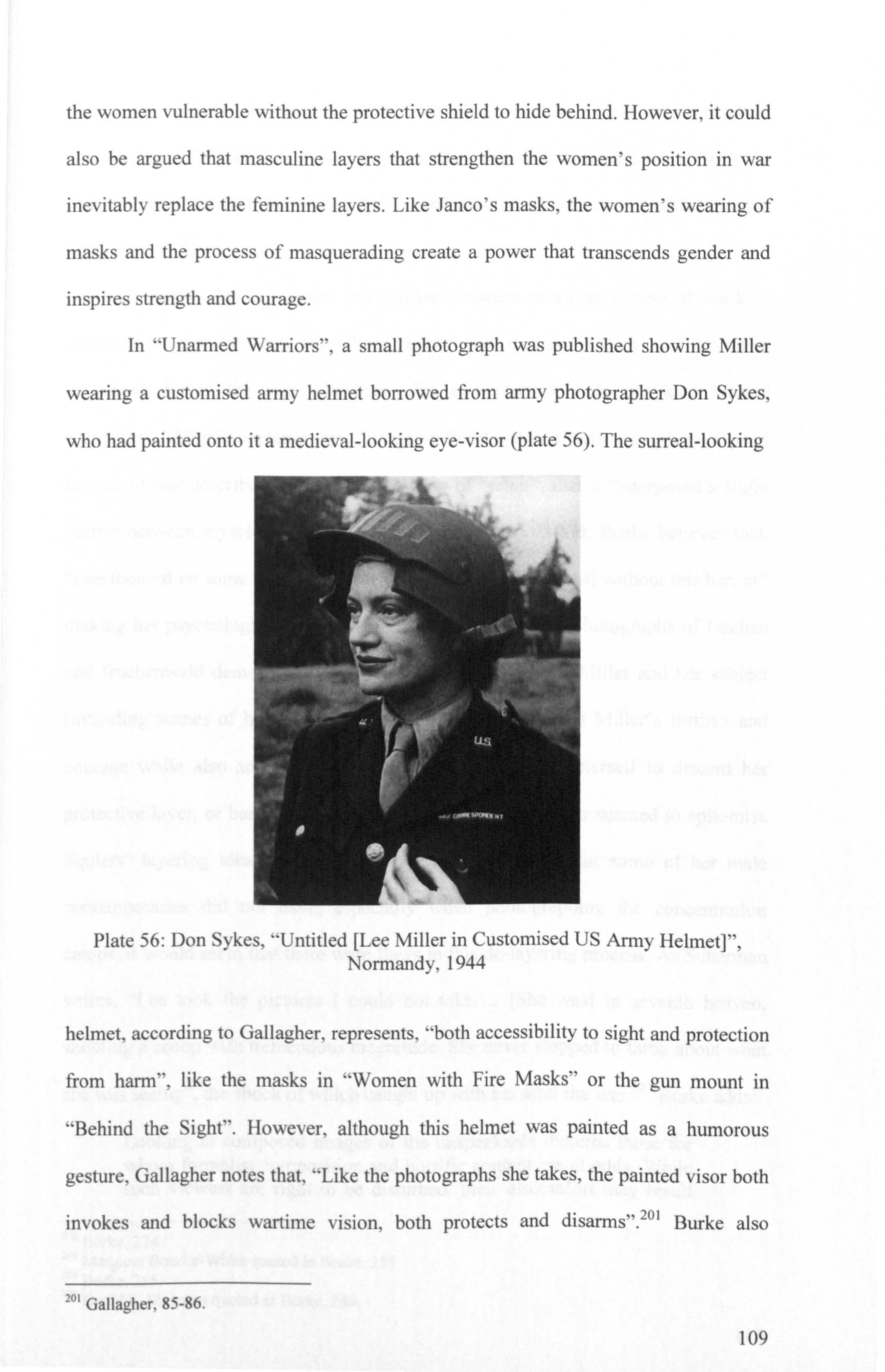

37. David E. Sherman, "Lee Miller at the Siege of St Malo", France, August 1944. Calvocoressi, Portraits from a Life, 90.

38. Lee Miller, "ATS Searchlight Battery", North London, 1943. Originally taken for but not used in the photo-essay "Night Life Now", Vogue, June 1943. Calvocoressi, Portraits from a Life, 82-83.

39. Lee Miller, "Untitled [Wrens Marching to their Placeof Work]", circa 1942.Lee Miller Archives. Photographreference4078-24. Lesley Thomasand Chris Howard Bailey, WRNSin Camera:the Women'sRoyal Naval Servicein the SecondWorld War (Stroud,Gloucestershire:SuttonPublishing,2000),ix.

40. Lee Miller, "A Dying ManBut Saved by Devoted Care", Normandy, 1944. Lee Miller, "Unarmed Warriors", Vogue, September 1944,37. (This image has also been entitled "Doctor Using Bronchoscope" in Calvocoressi, Portraits from a Life, 94, "Surgeon Using Bronchoscope, 44th Evac. Hospital" in Penrose,Lee Miller's War, 28-

viii

29, and "Field Hospital in Normandy. Emergency Surgery for a Patient with Chest Wounds", in Penrose,Lives of Lee Miller, 119).

41. Lee Miller, "Untitled [Figurehead]", 1943. Monochrome photograph, 9.6 x 3.9 cm. Lee Miller, Wrens in Camera (London: Hollis and Carter, 1945), iii.

42. Lee Miller, "H. R.H. The Duchess of Kent", 1943. Monochrome photograph, 20.3 x 15.0 cm. Miller, Wrens in Camera, v.

43. Lee Miller, "Untitled [Portrait of Vera Laughton Mathews]", 1943. Monochrome photograph, 8.0 x 6.6 cm. Miller, Wrens in Camera, viii.

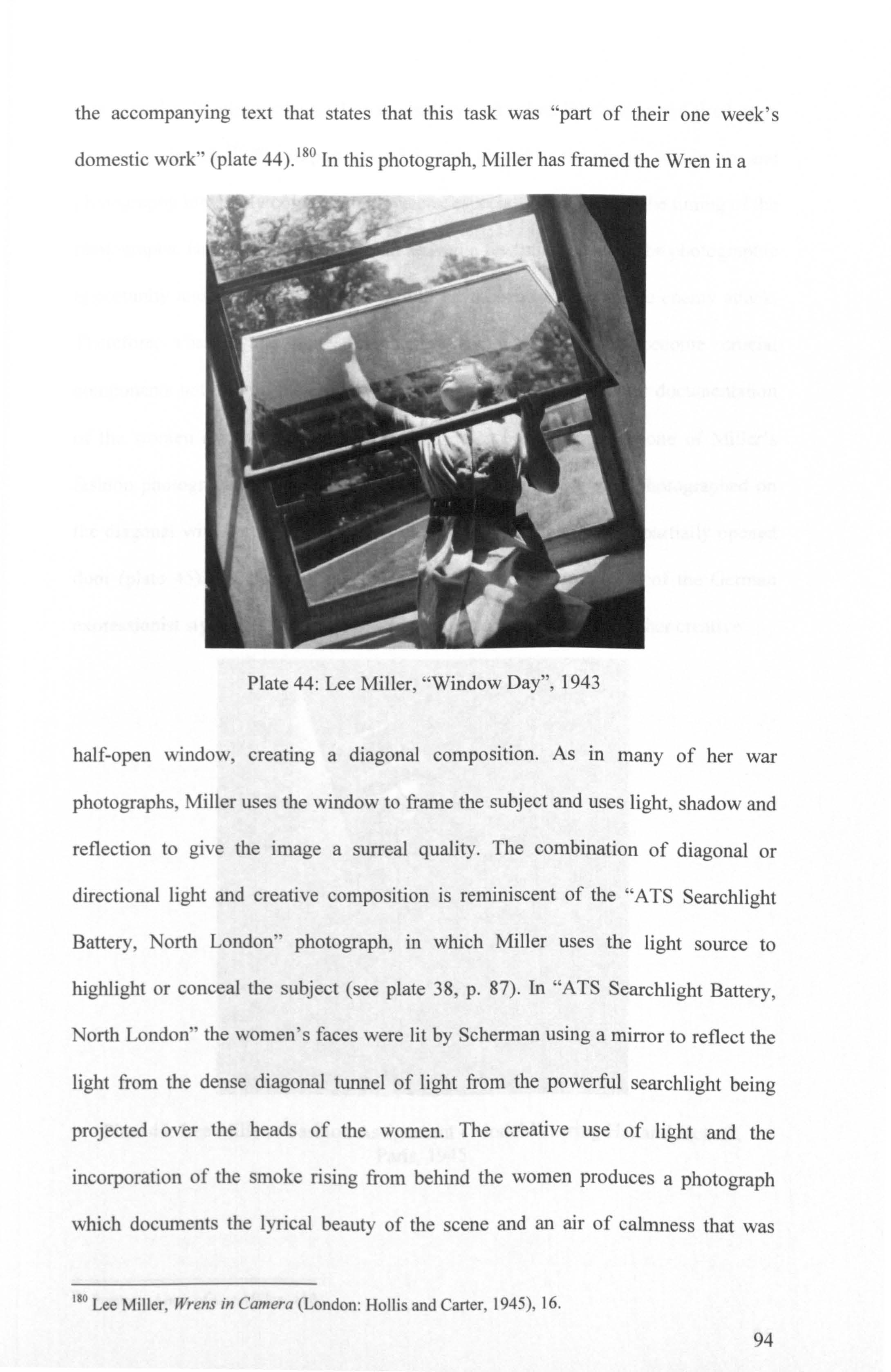

44. Lee Miller, "Window Day", 1943. Monochrome photograph, 17.0 x 16.4 cm. Miller, Wrens in Camera, 16.

45. Lee Miller, "Fashion AssignmentModel Wearing Hat and Jacket", Paris, 1945. Photo Gallery, "Fashion", Lee Miller Archives, http: //www. leemiller. co.uk/ imagedi sp . aspx?id=112&cat=7.

46. Lee Miller, "Water Off a Wren's Back", 1943. Monochrome photograph, 7.9 x 11.0 cm. Miller, Wrens in Camera, 63.

47. Lee Miller, "Ships at Sea", 1943. Monochrome photograph, 5.0 x 8.9 cm. Miller, Wrens in Camera, 23.

48. Claude Cahun, "Self-Portrait", 1928. Gelatine silver print, 30.0 x 23.5 cm. Musee des Beaux-Arts de Nantes. Mundy, Desire Unbound, 189.

49. Salvador Dali, The Persistence of Memory, 1931. Oil on canvas, 24.1 x 33 cm. The Collection, "Salvador Dali", The Museum of Modem Art, New York, http: //www. moma. org/collection/browse_results.php?object_id=79018.

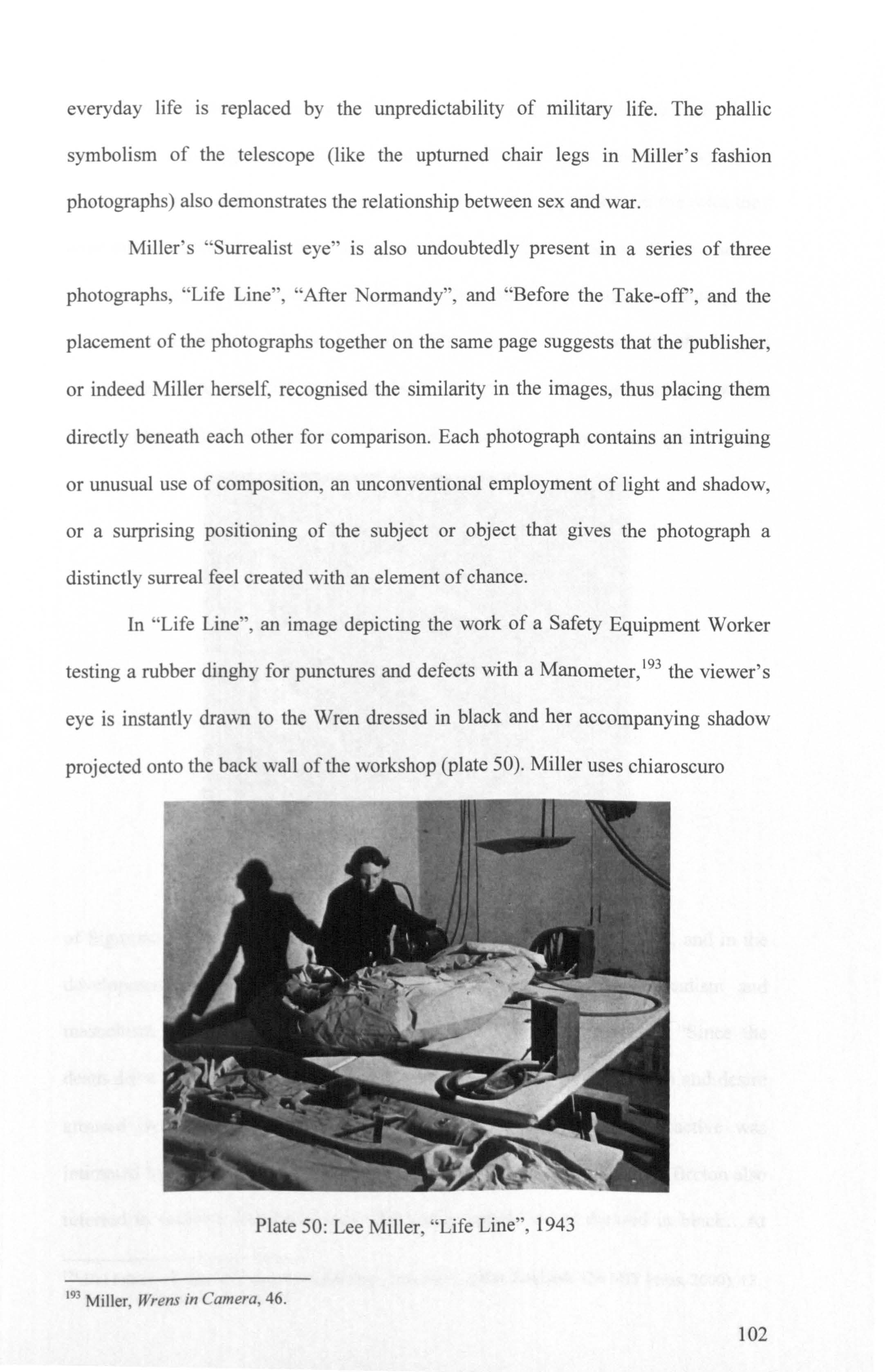

50. Lee Miller, "Life Line", 1943. Monochrome photograph, 9.4 x 11.8 cm. Miller, Wrens in Camera, 46.

51. Egon Schiele, Death and the Maiden, 1915-1916. Oil on canvas, 150 x 180 cm. Oesterreichische Galerie, Vienna. Mark Harden, "Egon Schiele", The Artchive, http: // www. artchive.com/artchive/S/schiele/schiele_death.jpg. html.

52. Lee Miller, "Untitled [FashionShot]", Sicily, 1949.Slusher,75.

53. Lee Miller, "Before the Take-off', 1943.Monochromephotograph,9.9 x 5.9 cm. Miller, Wrensin Camera,46.

54. Lee Miller, "After Normandy", 1943. Monochrome photograph, 10.0 x 6.9 cm. Miller, Wrens in Camera, 46.

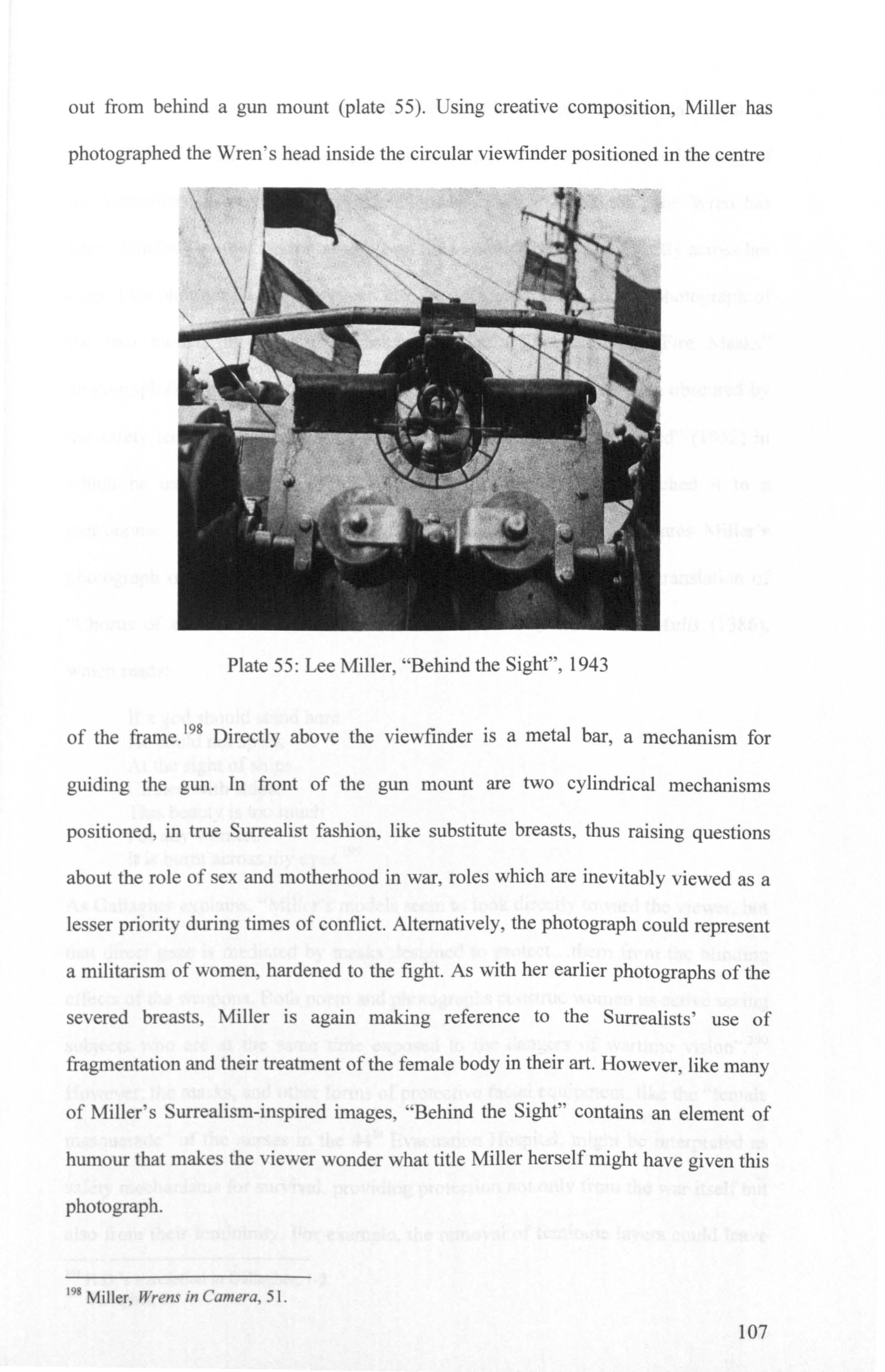

55. Lee Miller, "Behind the Sight", 1943. Monochrome photograph, 10.6 x 11.2 cm. Miller, Wrens in Camera, 51.

ix

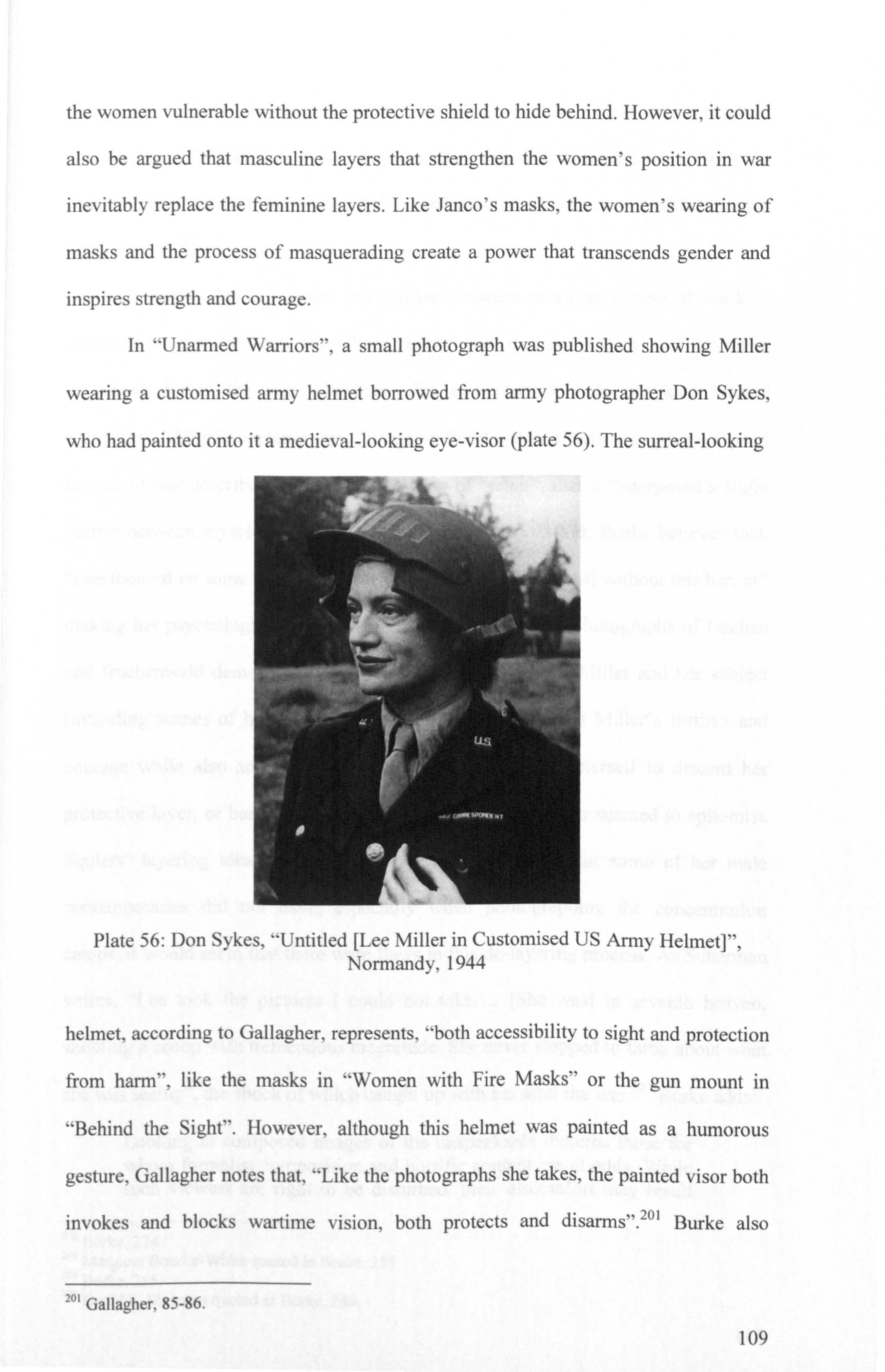

56. Don Sykes, "Untitled [Lee Miller in Customised US Army Helmet]", Normandy, 1944. The caption reads, "Sykes had painted on the stripes for fun". Carolyn Burke, Lee Miller (London and New York: Bloomsbury, 2005), 220, and Penrose, Lives of Lee Miller, 117.

Chapter Two

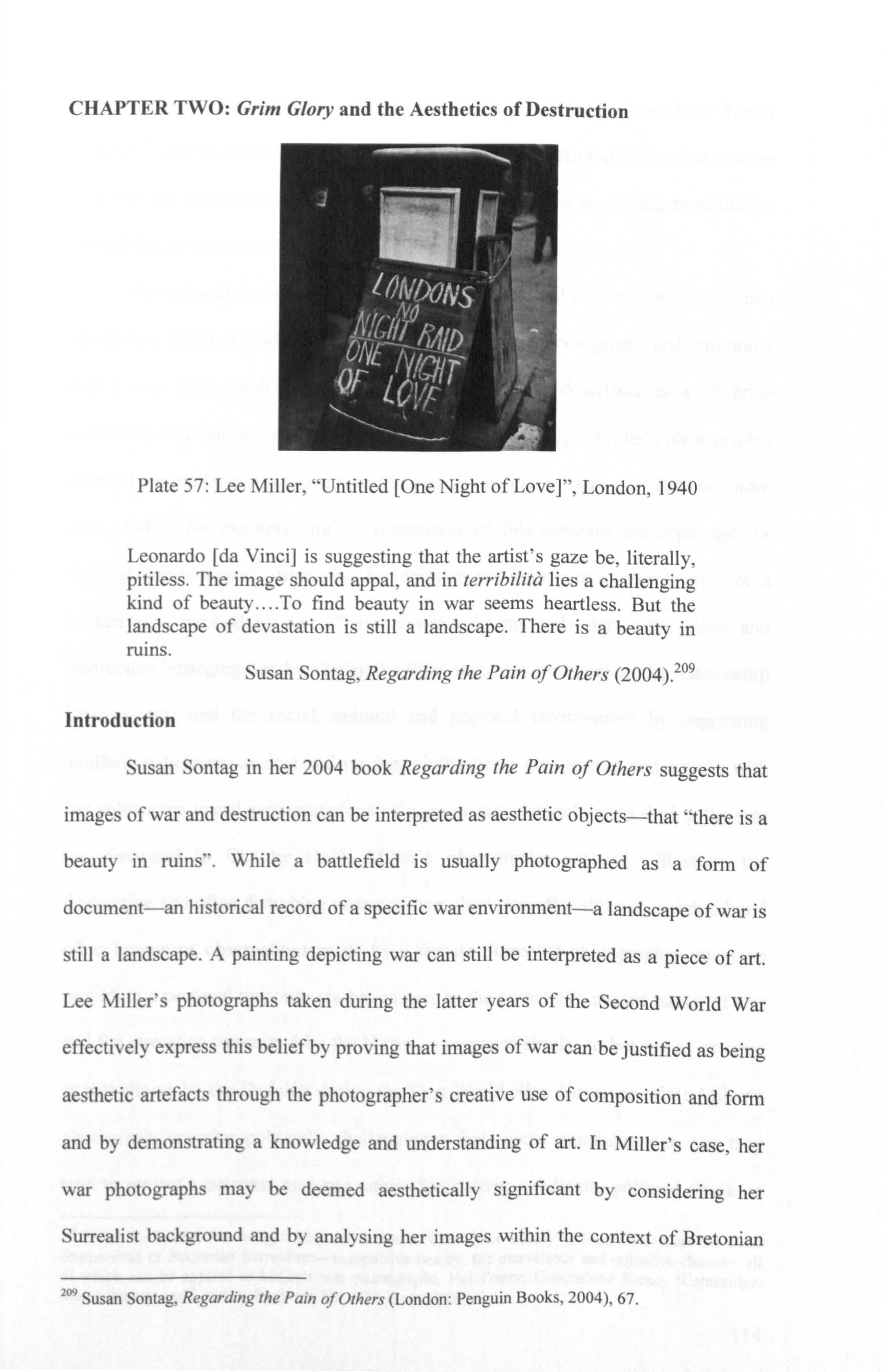

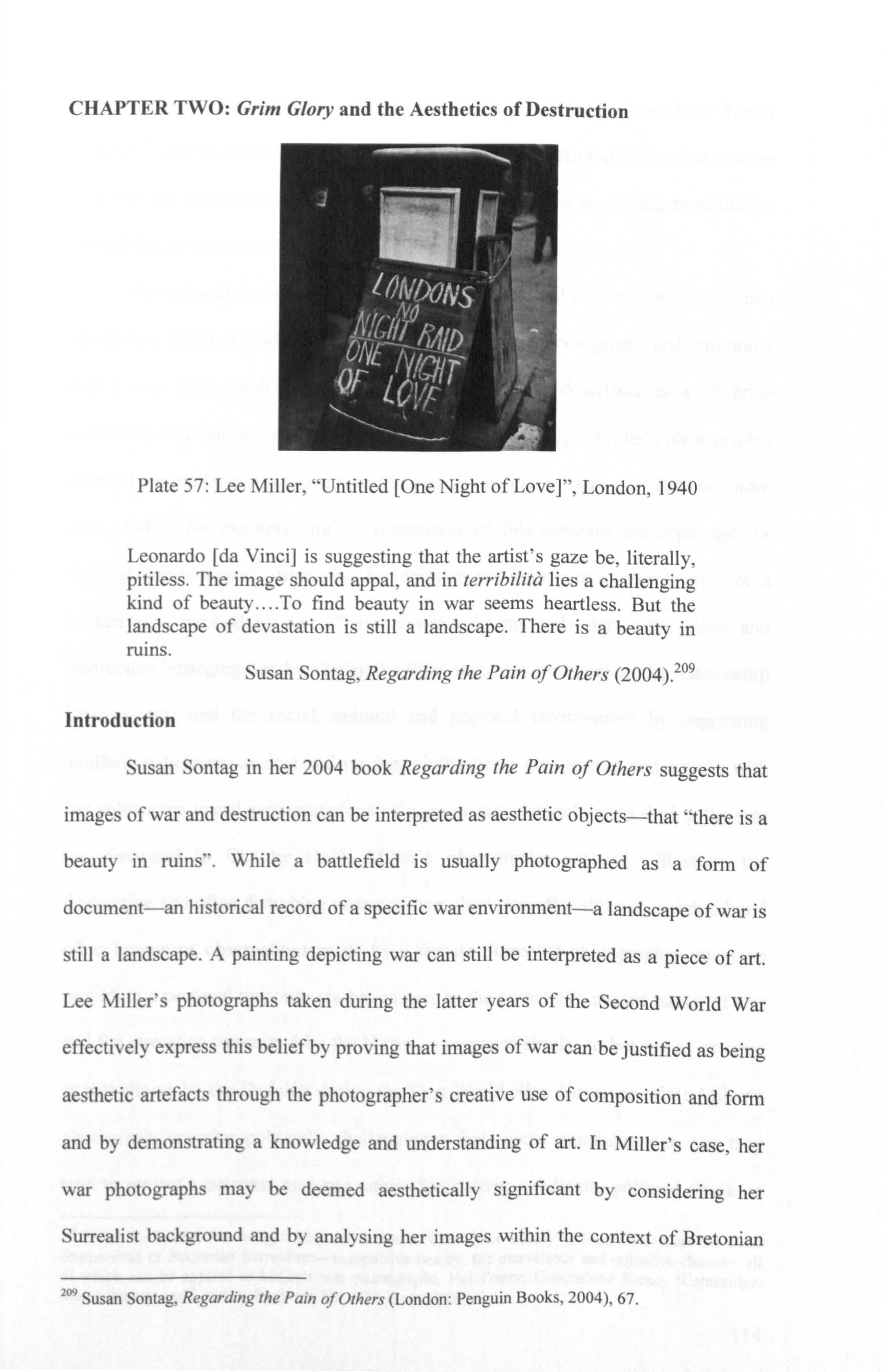

57. Lee Miller, "Untitled [One Night of Love]", London, 1940. Original caption in Grim Glory reads, "When no news is good news". Monochrome photograph, 10.2 x 11.1 cm. Ernestine Carter, ed., Grim Glory: Pictures of Britain Under Fire (London: Lund Humphries, 1941), plate 103. Antony Penroserefers to this photograph as "One Night of Love" in Penrose,Lives of Lee Miller, 108.

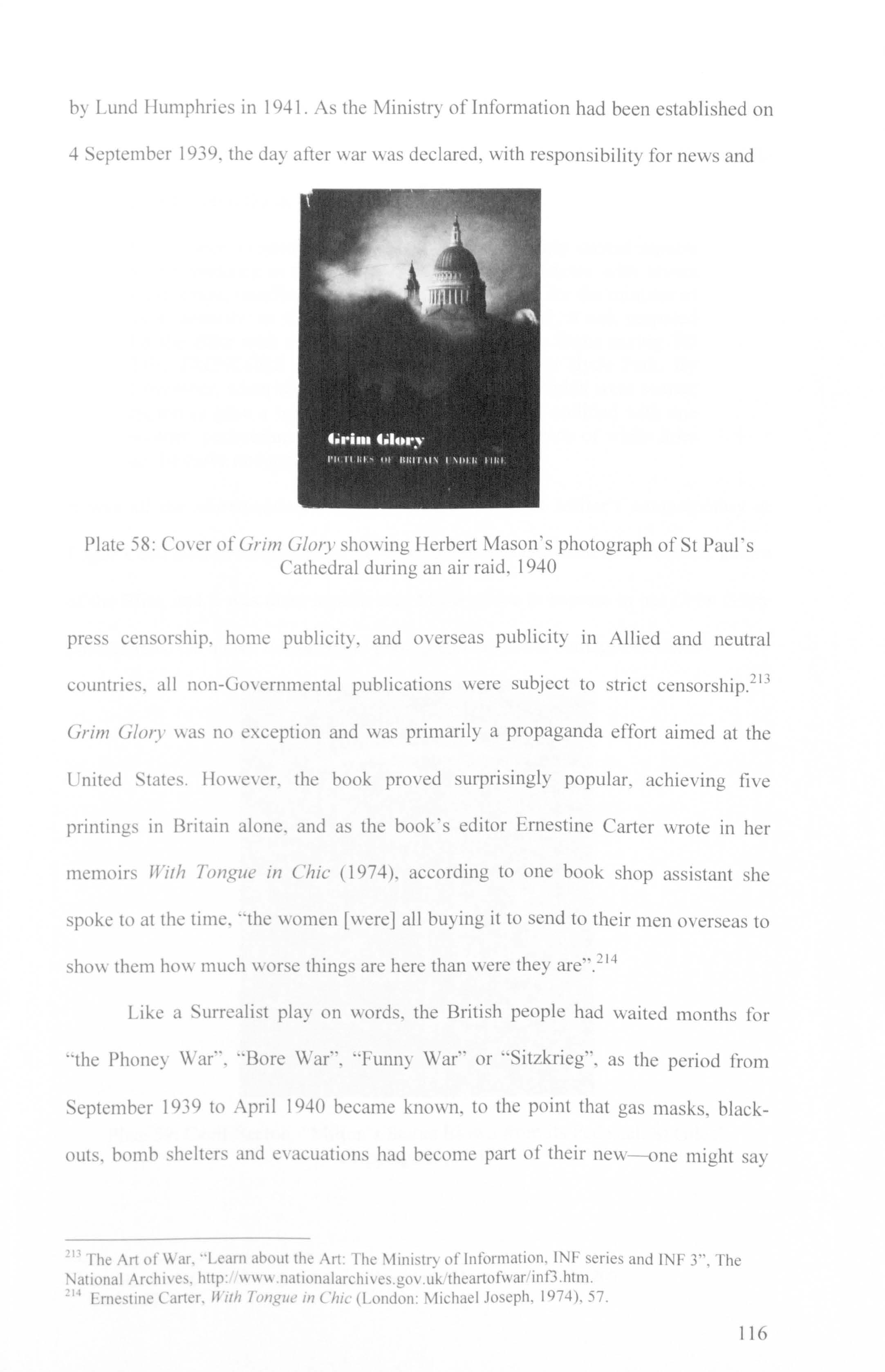

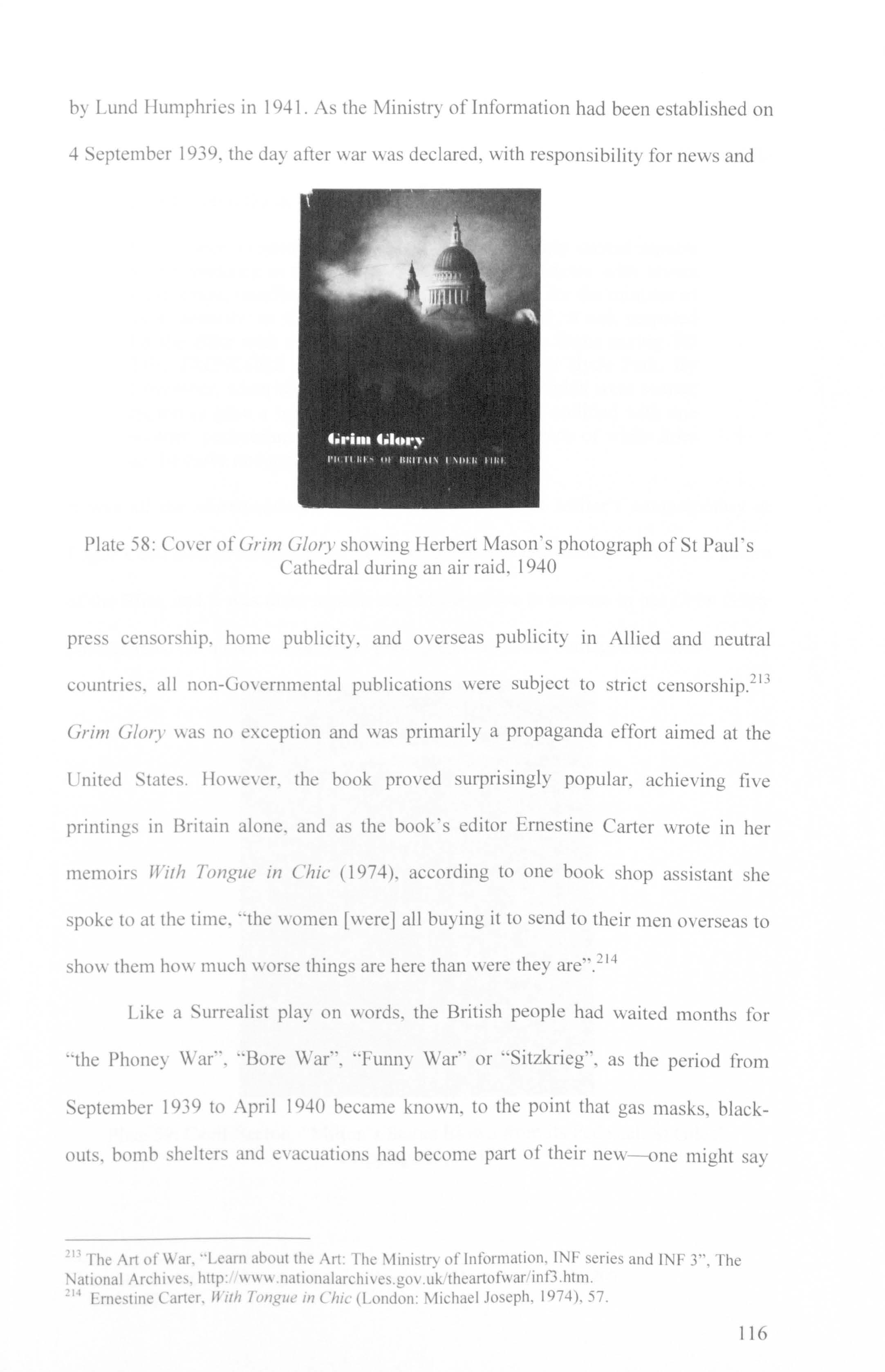

58. Cover of Grim Glory showing Herbert Mason's photograph of St Paul's Cathedral during an air raid, 1940. Ernestine Carter, ed., Grim Glory: Pictures of Britain Under Fire (London: Lund Humphries, 1941), cover plate.

59. Cecil Beaton, "Milton's Statue Blown from its Pedestal, St Giles', Cripplegate", 1940. James Pope-Hennessyand Cecil Beaton, History Under Fire (Mayfair, London: B. T. Batsford Ltd., 1941), 25.

60. Lee Miller, "Untitled [The Roof of St James's Piccadilly, Destroyed in the Blitz]", London, 1940. Originally taken for but not used in Grim Glory. Livingston, Lee Miller, Photographer, 134.

61. Lee Miller, "Untitled [Statues Covered by Camouflage Nets]", Schloss Linderhof, Bavaria, Germany, 1945. Penrosewrites, "Statues covered by camouflage nets make a landscape like a painting by Yves Tanguy, Germany, 1945". Penrose, Lives of Lee Miler, 136.

62. Lee Miller, "Untitled [Blast Pays Deserved Tribute to the Gas Light & Coke Company's Trademark, Mr Therm]", London, 1940. Monochrome photograph, 8.6 x 8.3 cm. Original caption from Grim Glory. Carter, plate 76.

63. Hans Belmer, Doll (La Poupee), 1935. Krauss and Livingston, L'Amour Fou, 194.

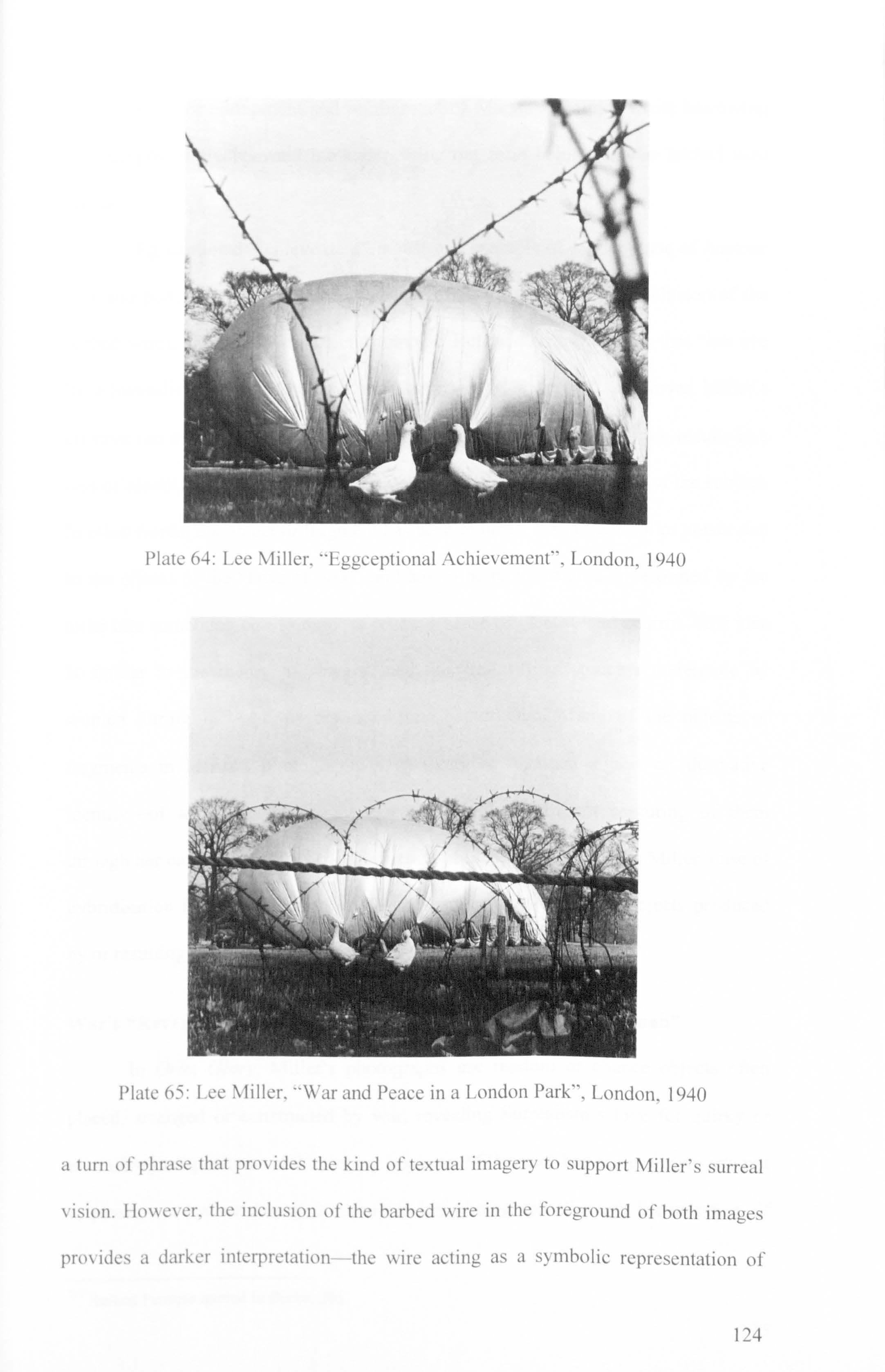

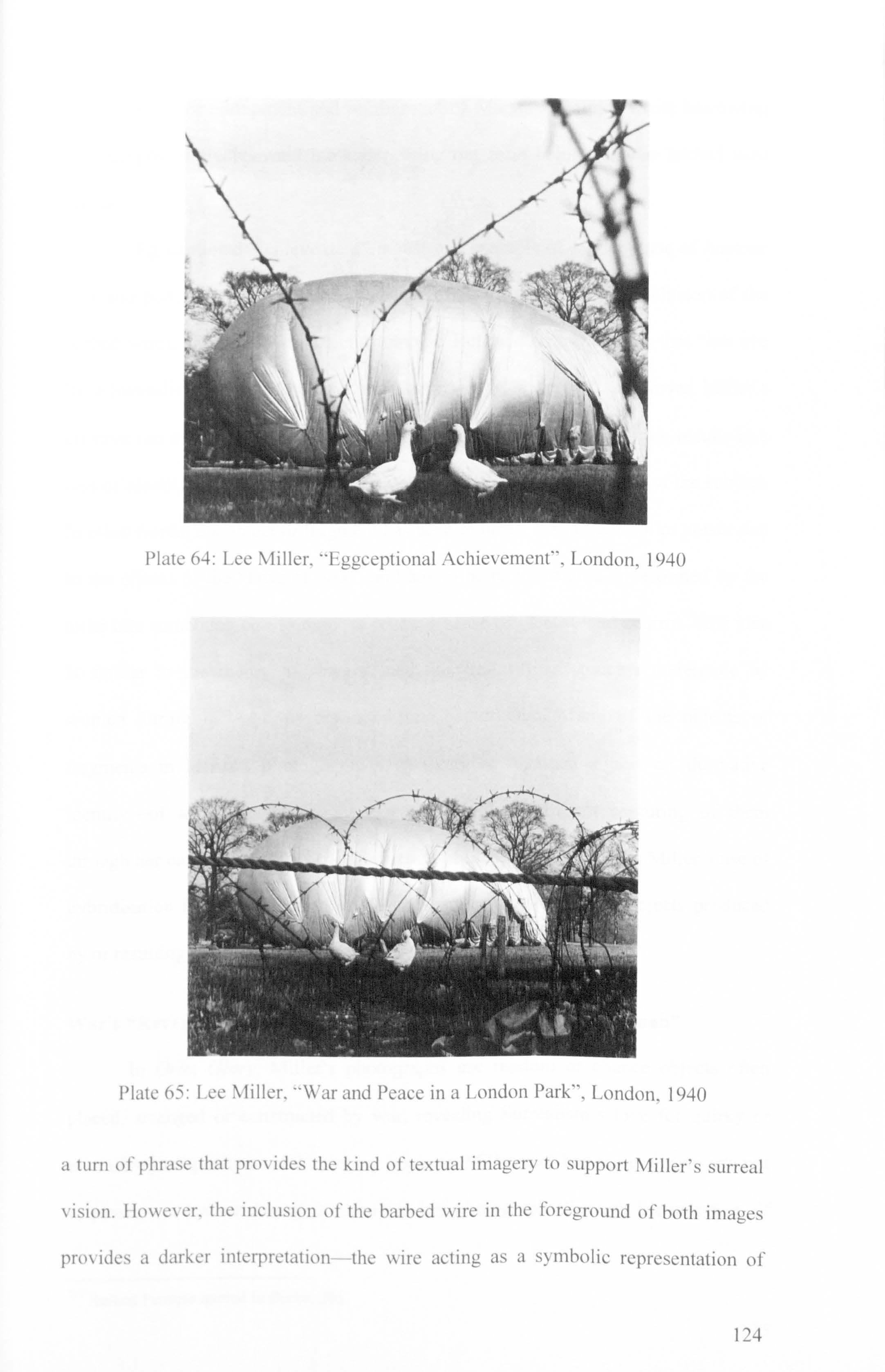

64. Lee Miller, "Eggceptional Achievement", London, 1940. Monochrome photograph, 15.4 x 16.5 cm. Original caption from Grim Glory reads, "The geesethat laid a silver egg". Carter, plate 104. (The title "Eggceptional Achievement" appears in Penrose,Lives of Lee Miller, 103, and Haworth Booth notes that this title was used by Miller herself in reference to this image. Haworth-Booth, 155).

65. Lee Miller, "War and Peacein a London Park", London, 1940.Originally taken for but not usedin Grim Glory. Haworth-Booth,158.

66. Lee Miller, "Remington Silent", London, 1940. Monochrome photograph, 8.5 x 7.8 cm. Original caption from Grim Glory. Carter, plate 72. (This title is used in Penrose, Lives of Lee Miller, 102, Penrose, Surrealist and the Photographer, 147, Haworth-Booth, 156 and Slusher, 56).

X

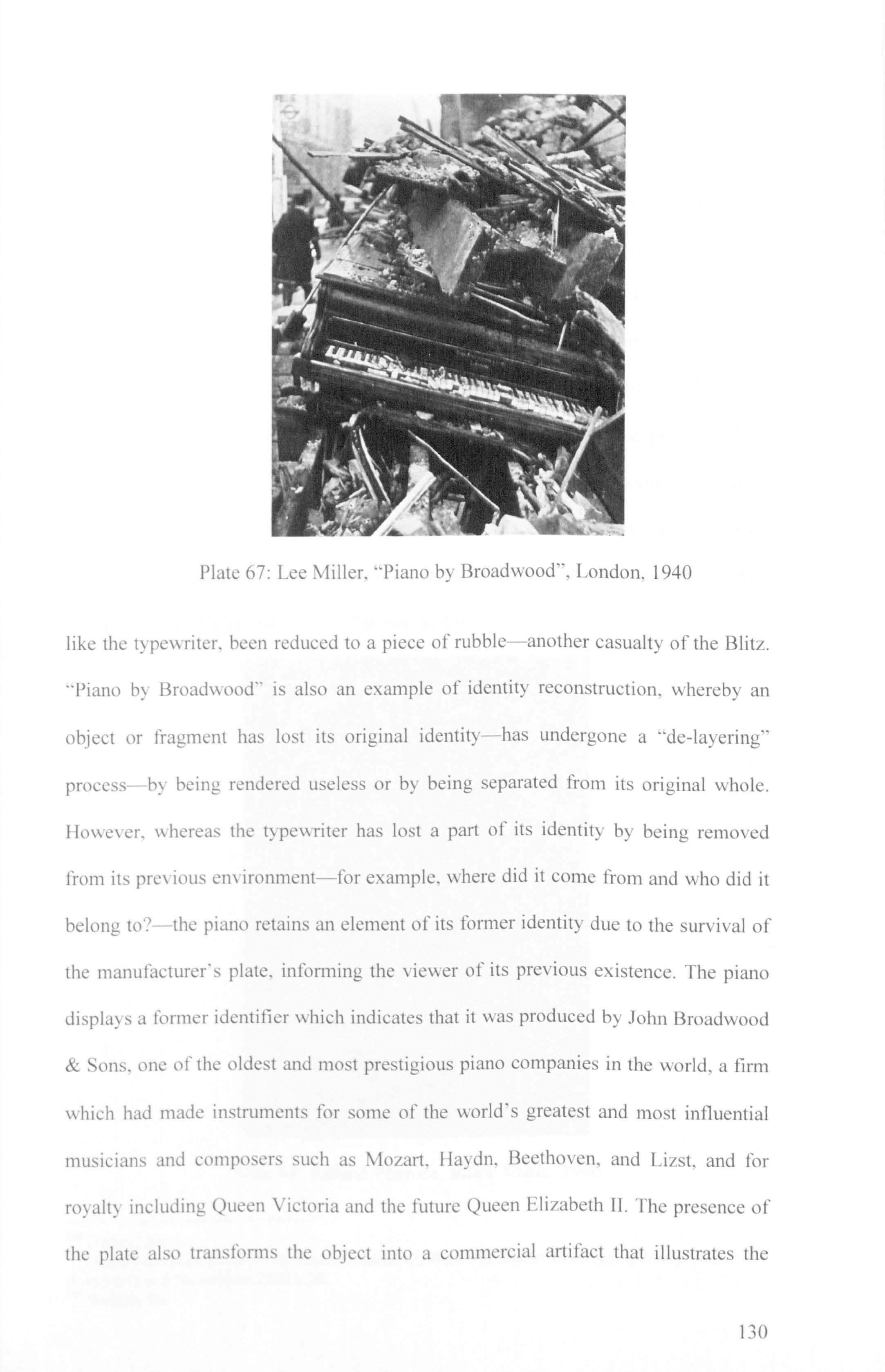

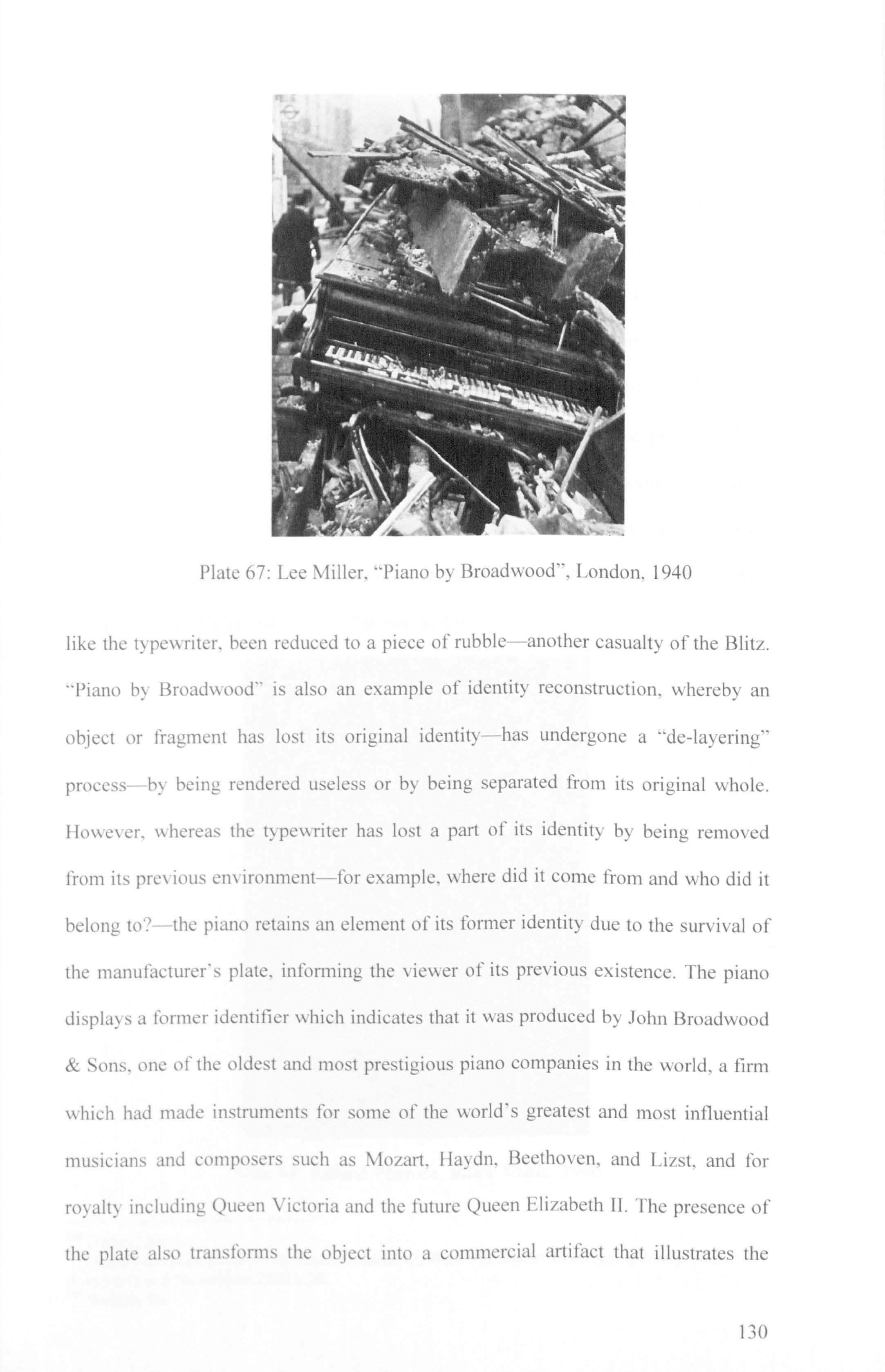

67. Lee Miller, "Piano by Broadwood", London, 1940. Monochrome photograph, 8.5 x7 cm. Original caption from Grim Glory. Carter, plate 73.

68. Roland Penrose, Black Music, 1940. Oil on plywood, 59.5 x 44.7 cm. Penrose, Surrealist and the Photographer, plate 27.

69. Man Ray, La Cadeau, 1919. Flat-iron with nails, 15.2 x 8.9 cm. Roland Penrose, Man Ray (London: Thames and Hudson, 1975), 71.

70. Man Ray, Dancer (Danger), 1920. Engraving on glass, 17.1 x 11.1 cm. Galleria Schwarz, Milan. Penrose,Man Ray, 19.

71. Lee Miller, "Revenge on Culture", London, 1940. Monochrome photograph, 17.8 x 16.0 cm. Original caption from Grim Glory. Carter, plate 71. (This title is used in Penrose, Lives of Lee Miller, 107, Livingston, Lee Miller, Photographer, 59, and Haworth-Booth, 157).

72. Man Ray, "Lee Miller in Cocteau's Film, The Blood of a Poet", 1930. Gelatin silver print, 9.8 x 6.2 cm. Private collection, Paris. De L'Ecotais and Sayag, 146.

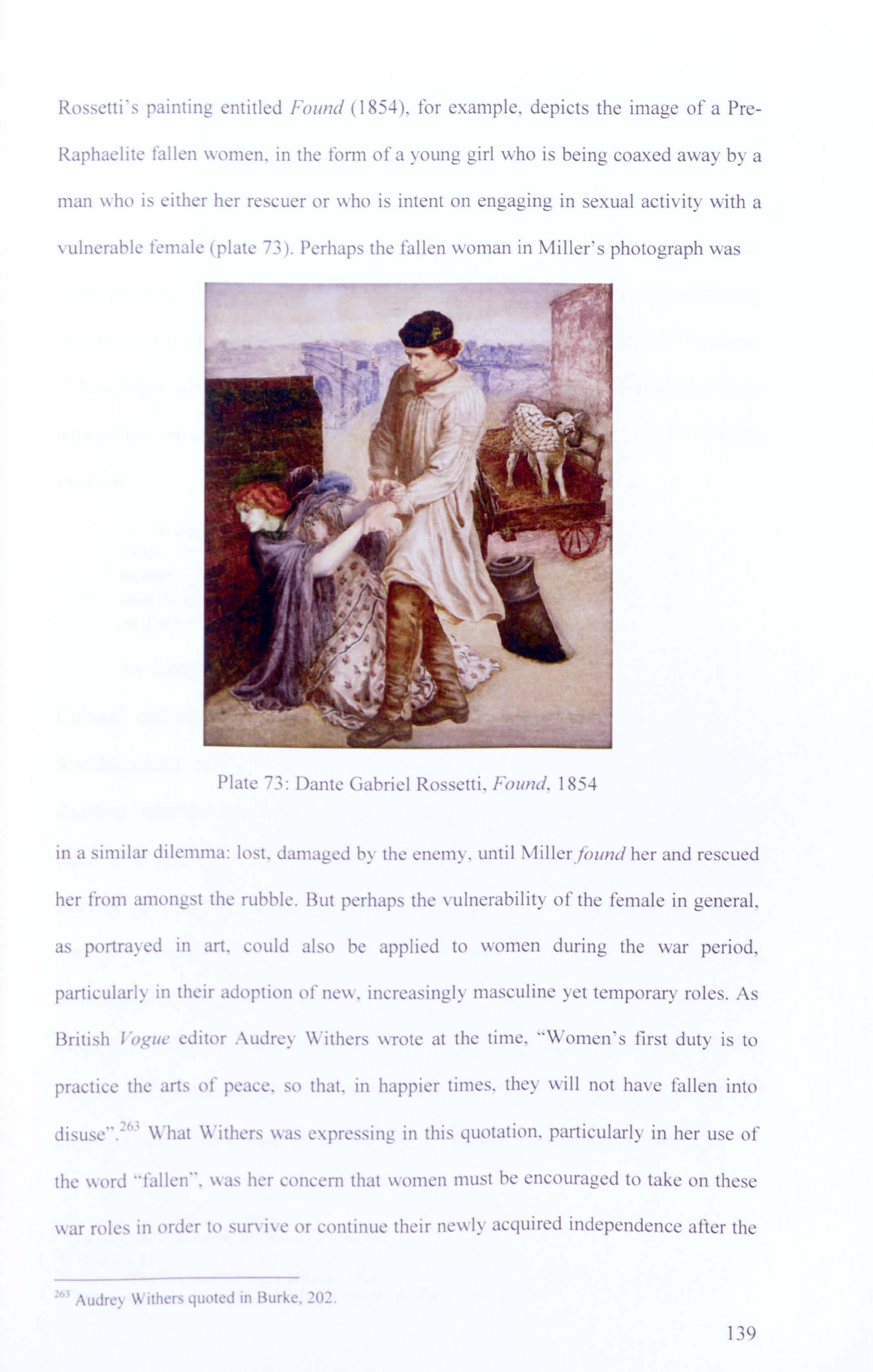

73. Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Found, 1854. Oil, 91.4 x 80 cm. Delaware Art Museum. Jerome J. McGann, "Found", The Rossetti Archive, http: //www. rossettiarchive. org/docs/s64.rap.html.

74: Lee Miller, "Untitled [Stadtkämmerer of Leipzig's Daughter Suicided]", Leipzig, Germany, 1945. SHAEF (Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force) censor stamp dated 30 April 1945, and typed caption: "Suicide: Leipzig Burgomaster's pretty daughter, a victim of Nazi philosophy, kills self'. Haworth-Booth, 195.

75. Vassily Grigorievitch Perov, The Drowned Woman, 1867. Oil on canvas, 67.9 x 108.6 cm. Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow. University Scholars Programme Project, "The Drowned Woman by Vassily Grigorievitch Perov", The Victorian Web: Literature, History and Culture in the Age of Victoria, http: //www. victorianweb. org/painting/misc/perovl. htrnl.

76. Margaret Bourke-White, "The Suicide of a Minor Nazi Official and His Family", Leipzig, April 1945. Chris Boot, Great Photographers of World War II (Avenal, NJ: Crescent Books, 1993), 95.

77. Lee Miller, "Untitled [Bombed Nonconformist Chapel]", Camden Town, London, 1940. Monochrome photograph, 9.5 x 9.7 cm. Original caption from Grim Glory reads, "1 Nonconformist chapel +1 bomb = Greek temple". Carter, plate 74.

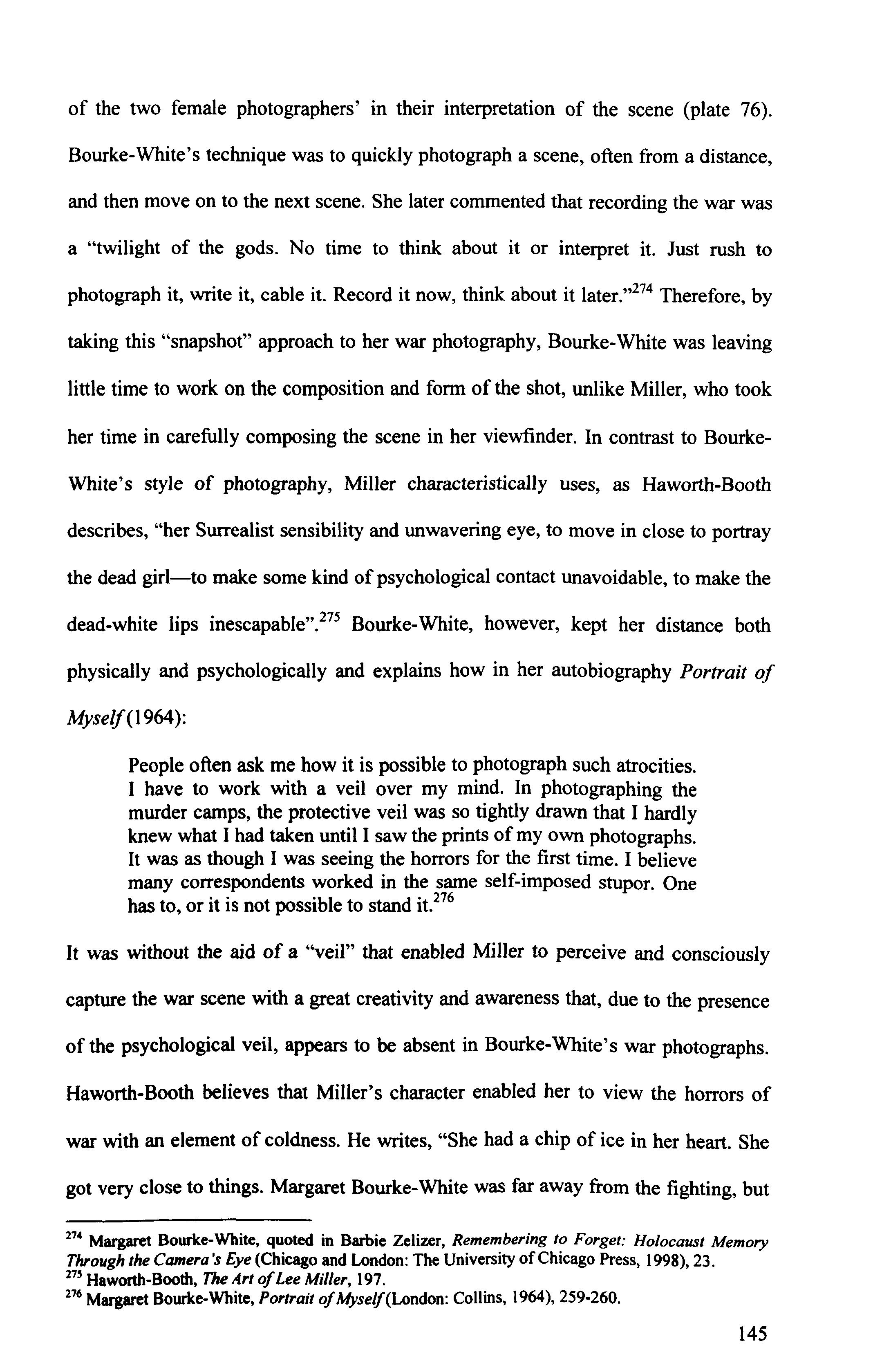

78. Lee Miller, "Restoration of Roman Ruins", El Kharga, circa 1936. HaworthBooth, 131.

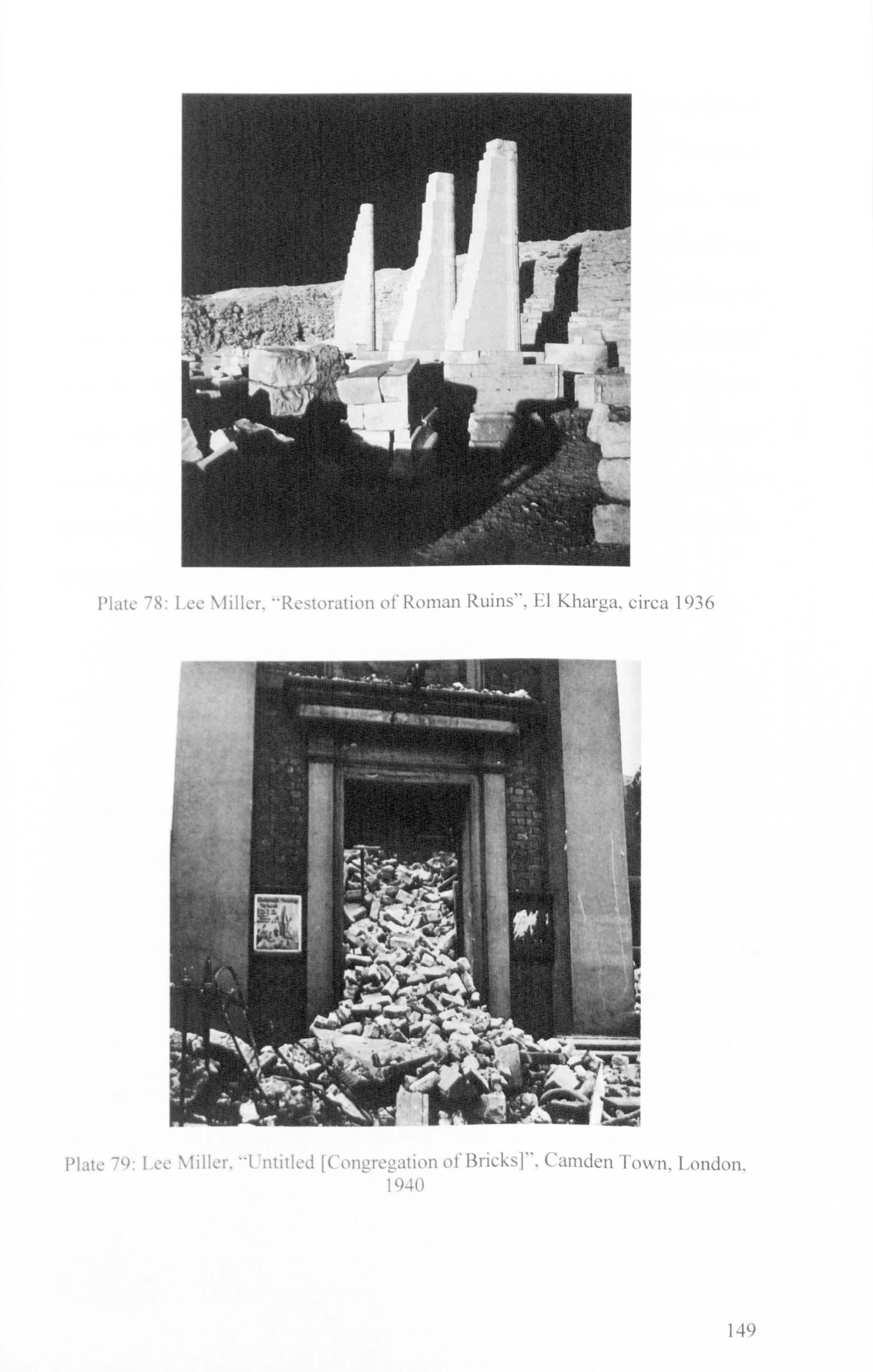

79. Lee Miller, "Untitled [Congregation of Bricks]", Camden Town, London, 1940. Originally taken for but not used in Grim Glory. Livingston, Lee Miller, Photographer, 61.

X1

80. Lee Miller, "Bombed Interior, Cologne Cathedral", Germany, 1945. Penrose, Surrealist and the Photographer, 89.

81. Lee Miller, "Untitled [Blocked Doorway]", Syria, 1938. Penrose, Lives of Lee Miller, 84.

82. Lee Miller, "Picnic", Ile Sainte-Marguerite, Cannes, France, 1937. HaworthBooth, 142.

83. Lee Miller, "Portrait of Space", Near Siwa, Egypt, 1937. Haworth-Booth, 136137. (This final photograph was the last of four frames taken. All frames in sequence have been printed in Haworth Booth, 134-137).

84. Edward Weston, "Harmony Borax Works, Death Valley", 1938. Geoff Dyer, The Ongoing Moment (London: Abacus, 2006), 234.

85. Lee Miller, "Untitled [Bomb Site on Charlotte Street]", London, 1940. Monochrome photograph, 9.4 x 9.5 cm. Original caption reads, "You will not lunch in Charlotte Street today. The bay trees that marked the entrance to Soho restaurants are mobilised to guard an unexpectedpatron". Carter, plate 68.

86. Lee Miller, "Indecent Exposure?" London, 1940. Monochrome photograph, 9.5 x 9.5 cm. Original caption from Grim Glory. Carter, plate 77.

87. Lee Miller, "Untitled [Sculpture in Window]", Paris, circa 1930. Inscribed: "lee miller, Paris 1930". Haworth-Booth, 57.

88. Lee Miller, "Untitled [Man in White Hat]", Paris, circa 1930. Haworth-Booth, 58.

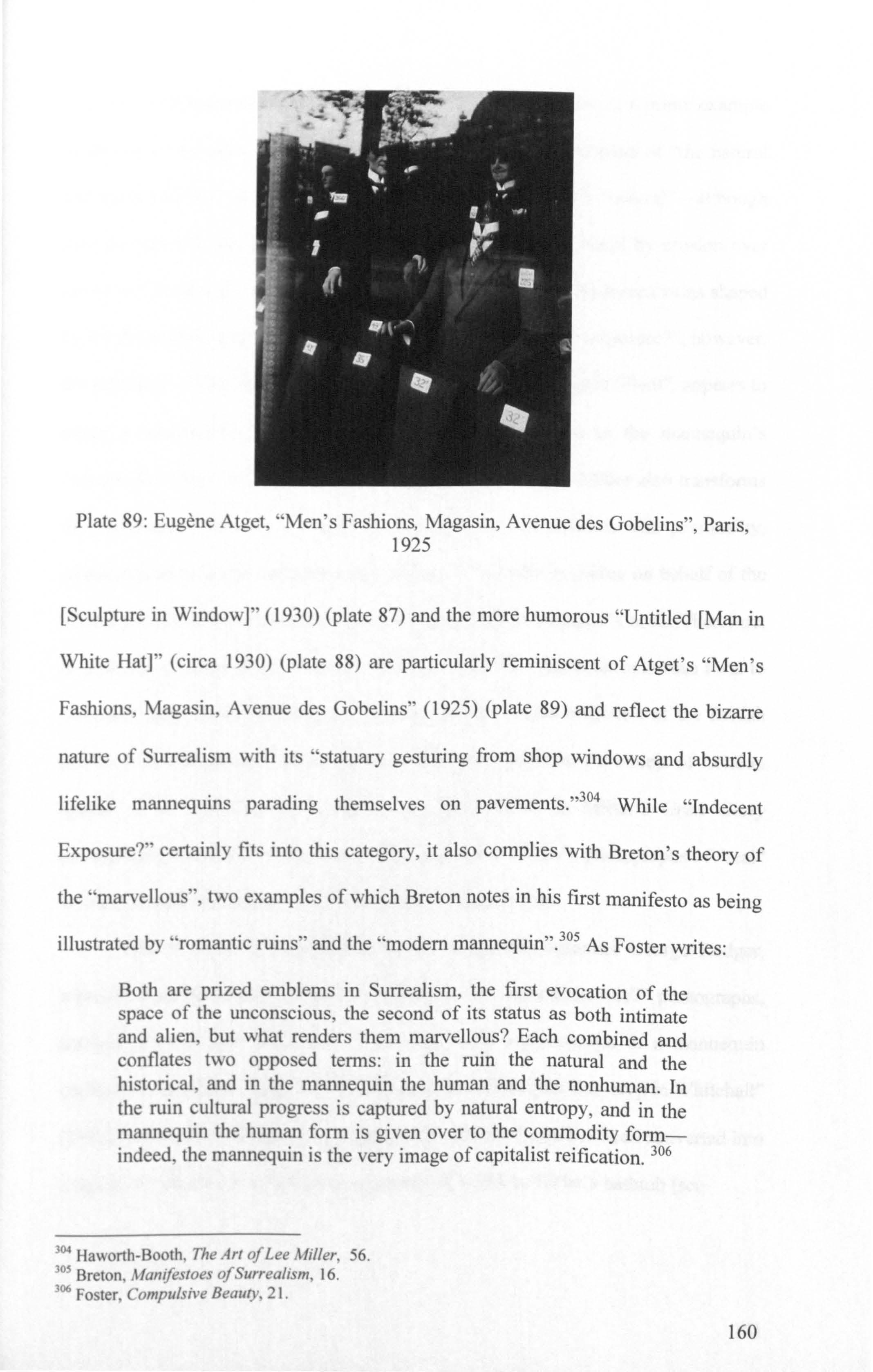

89. Eugene Atget, "Men's Fashions, Magasin, Avenue des Gobelins", Paris, 1925. Toned gelatin silver print, 22.7 x 17.0 cm. George Eastman House. The Collection, "Eugene Atget", The Museum of Modem Art, New York, http: //www. moma.org/ collection/browse _results.php?criteria=O%3 ADE%3 AI%3 A4%7C G%3AHO%3 AE% 3A 1&page_number=5&template_id=1 &sort_order= l.

90. Lee Miller, "Indecent Exposure... Please Take Me Away", London, 1940. Originally taken for but not used in Grim Glory. 17.9 x 17.8 cm. Lee Miller Archives. Haworth-Booth, 158.

91. George Rodger, "A Prescient Effigy of Hitler Hangs from a Shattered Bus-stop in Whitehall", London, 1940. Tom Hopkinson, The Blitz: The Photography of George Rodger (London: Penguin Books, 1990), 176.

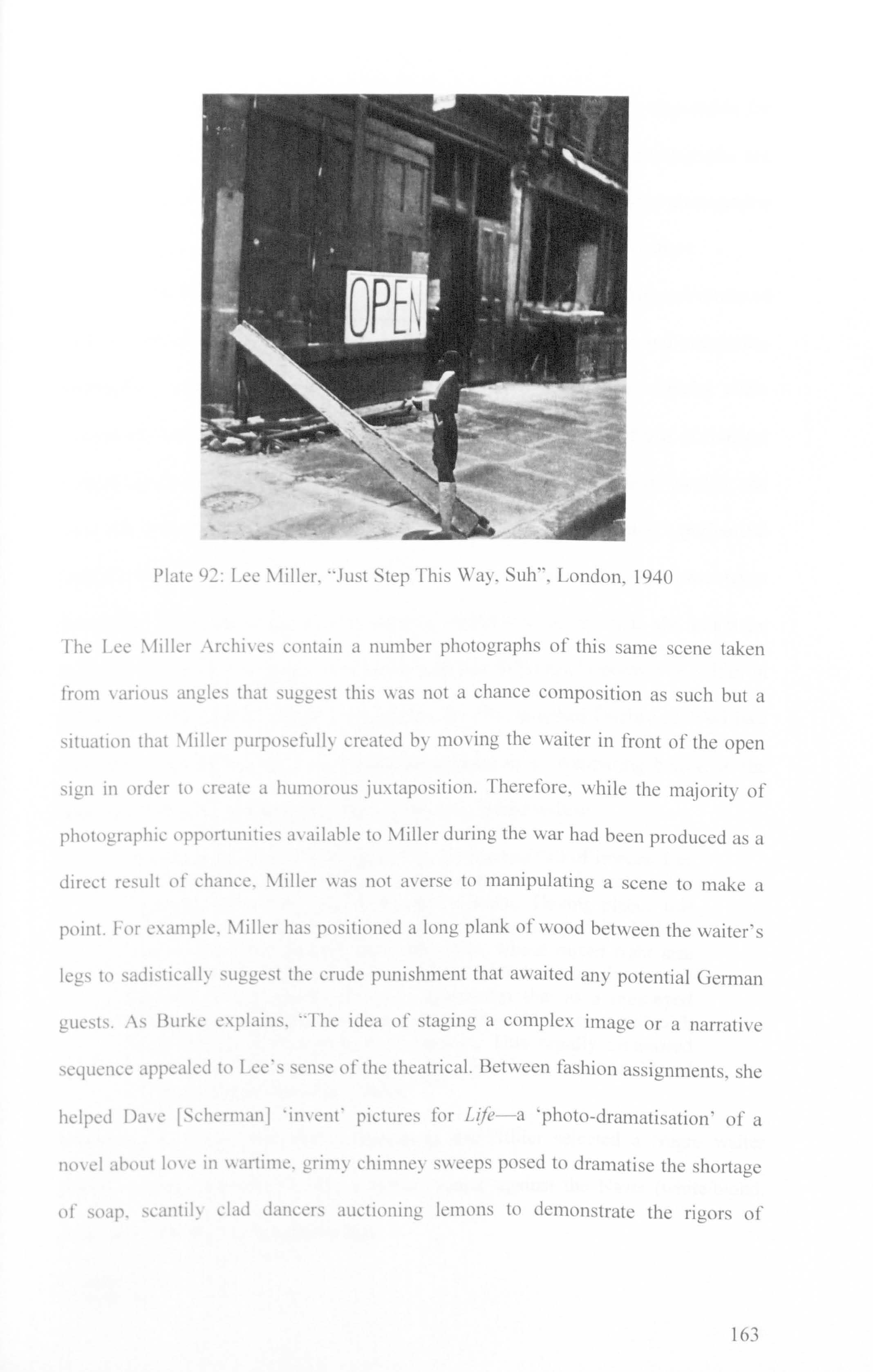

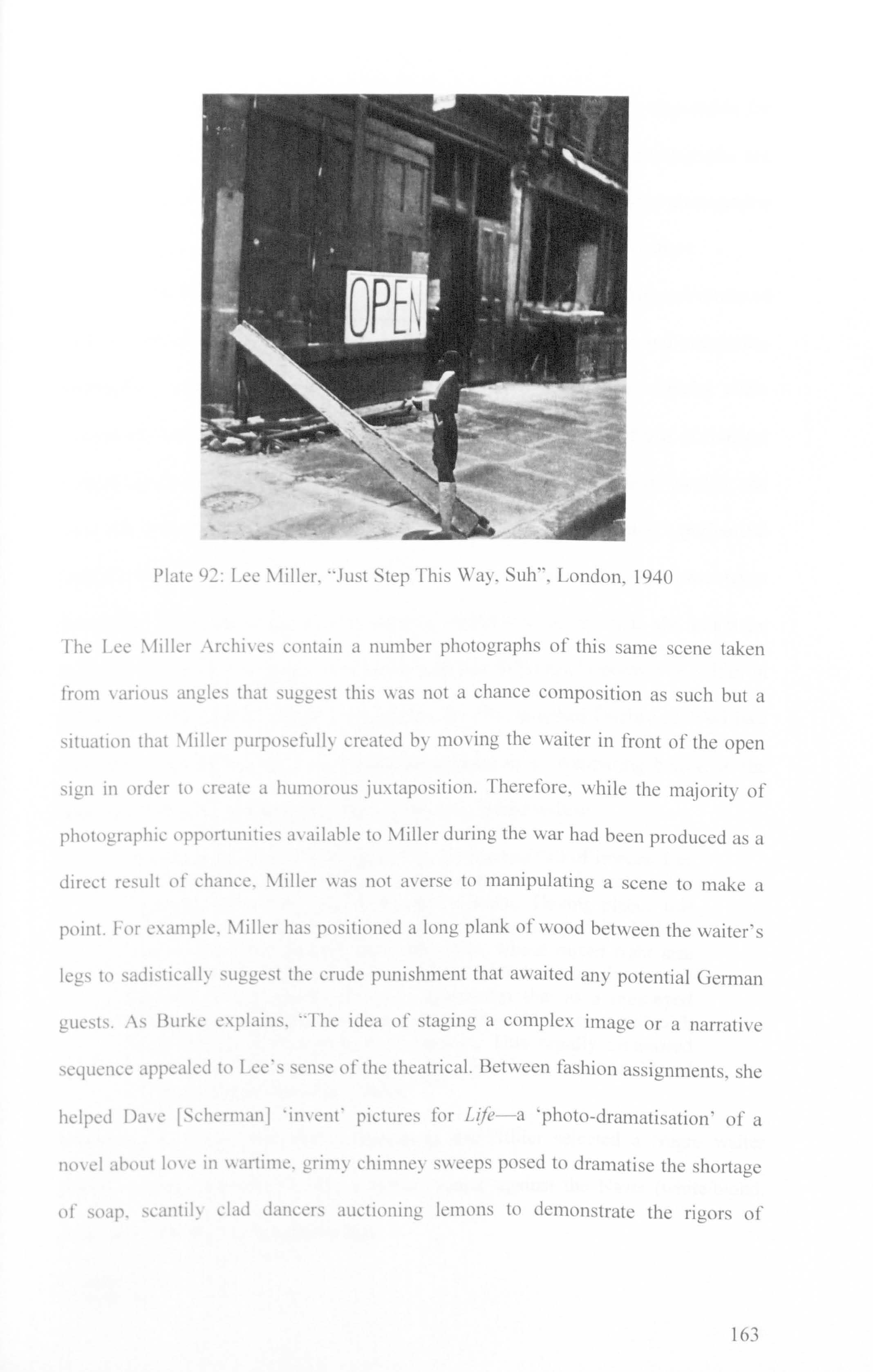

92. Lee Miller, "Just Step This Way, Suh", London, 1940.Monochromephotograph, 7.5 x 7.3 cm. Original caption from Grim Glory. Carter,plate 100.

93. Lee Miller, "Untitled [Site of St John Zachary Destroyed in the Great Fire of 1666]", London, 1940. Monochrome photograph, 16.5 x 15.7 cm. The original caption reads, "Above, a lone survivor of the Fire of 1940, a plaque commemorates an earlier holocaust". Carter, plate 62.

X11

94. Lee Miller, "Untitled [Burlington Arcade]", London, 1940. Monochrome photograph, 19.0 x 15.5 cm. The original caption reads, "Since the early 1800s the arcade has been a symbol of luxury and frivolity. Bombed, it achieves a Piranesian grandeur". Carter, plate 49.

95. Giovanni Battista Piranesi, Untitled [The Smoking Fire], from Carceri d' Invenzione, Plate VI, circa 1750. Etching. National Academy of Science, "Giovanni Battista Piranesi & Vik Muniz: Prisons of the Imagination", The National Academies: Advisers to the Nation on Science, Engineering, and Medicine, http: //www7. nationalacademies.org/arts/Piranesi_ Carceri_Plate_Vl. html.

96. Lee Miller, "Untitled [St James's Piccadilly]", London, 1940. Monochrome photograph, 19.0 x 15.5 cm. Part of the original caption from Grim Glory. Full caption reads, "St James's, Piccadilly. From the gutted shell of Wren's own favourite church, the angels raise their trumpets to the open sky". Carter, plate 50.

97. Lee Miller, "Untitled [Bridge of Sighs]", Lowndes Street, Knightsbridge, London, 1940. Monochrome photograph, 11.9 x 9.5 cm. Original caption reads, "A bridge of sighs finds itself an uncomfortable alien in the Victorian stucco regularity of Lowndes Street, Knightsbridge". Carter, plate 63.

98. George Rodger, "The Remains of a Building on Oxford Street After a Night-long Air Raid", London, 1940. Hopkinson, 39.

99. Graham Sutherland, Devastation, 1941: An East End Street, 1941. Crayon, gouache, pen and ink, pencil and watercolour on paper support, 64.8 x 110.4 mm. Tate Collection, (reference no. N05736), http: //www. tate. org.uk/servlet/ViewWork? workid=14017&searched=9180&roomid=3954&tabview= work.

100. Bill Brandt, "Elephant and Castle Shelter", London, 1940. Paul Delany, Bill Brandt: A Life (London: Jonathan Cape-Pimlico, 2004), 170.

Chapter Three

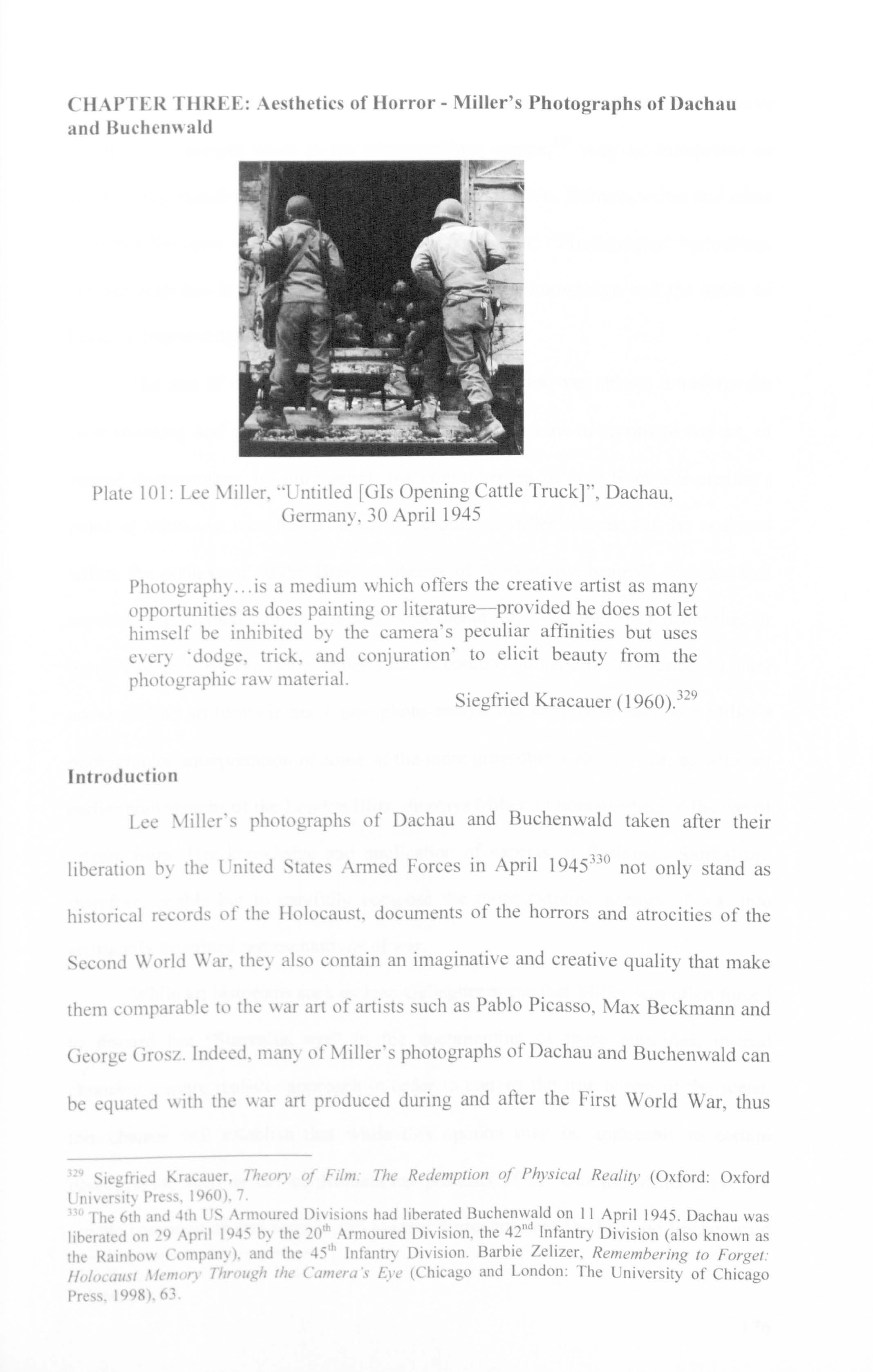

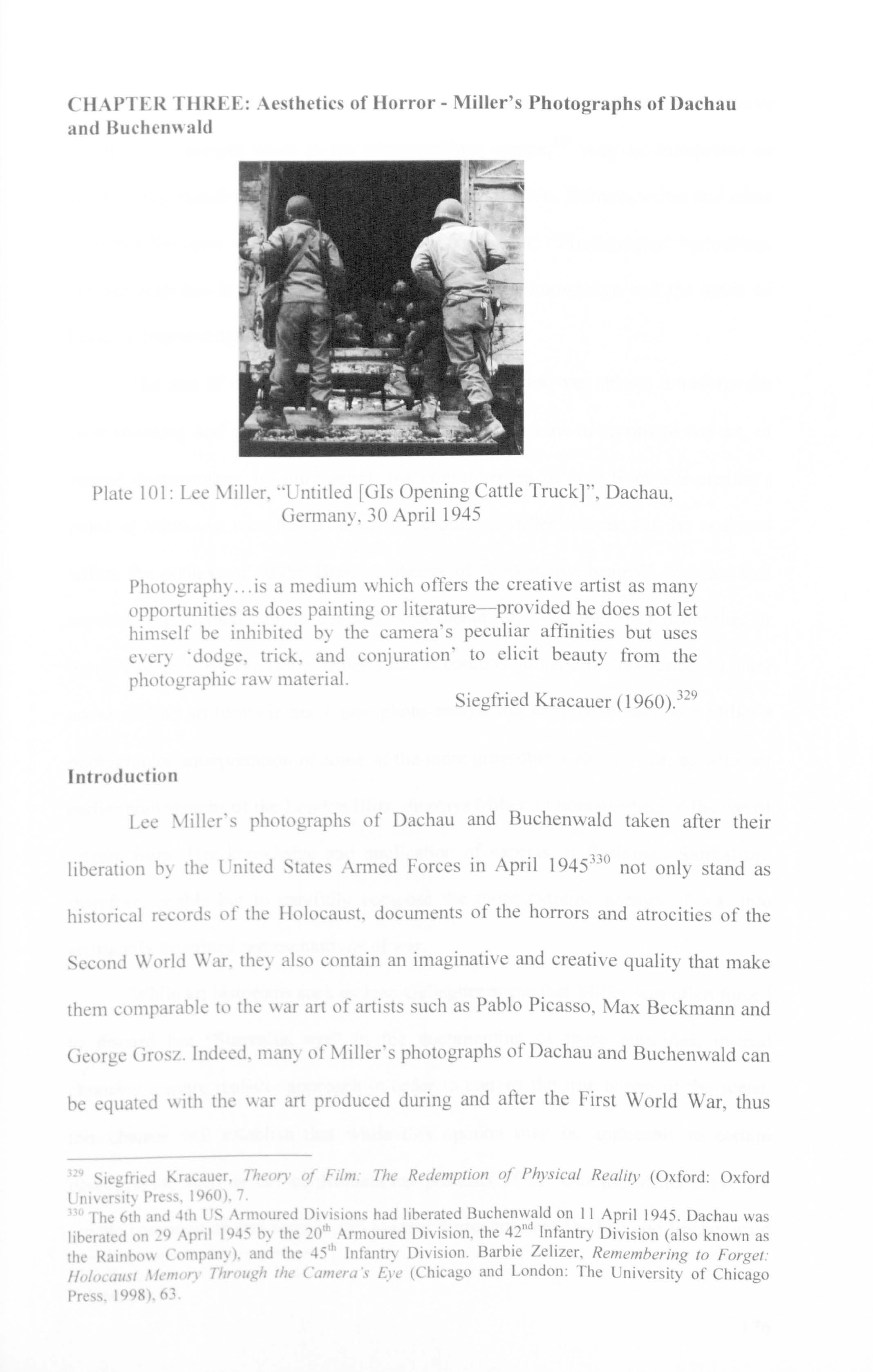

101. Lee Miller, "Untitled [GIs Opening Cattle Truck]", Dachau, Germany, 30 April 1945. Penrose,Lee Miller's War, 183.

102. Lee Miller, "Scales of Justice", Vogue,June 1945. Haworth-Booth, 188.

103. Susan Meiselas, "Cuesta del Plomo", Nicaragua, 1978. Sara Stevenson, Isabella Rossellini, Christiane Amanpour and Sheena McDonald, Magnum's Women PhotographersMagna Brava (Munich, London and New York: Prestel, 1999), 108.

104.RichardMisrach, "DeadAnimals #324,The Pit", Nevada,1987-1989.Orvell, 59.

105. Lee Miller, "Untitled [Hanging SS Guard]", Dachau, 30 April 1945. Livingston, Lee Miller, Photographer, 84.

X111

106. Matthias Grünewald, Crucifixion Detail from Isenheim Altar, circa 1515. Roland Penrose, Wonder and Horror of the Human Head. An Anthology (London: Lund Humphries, 1953), 27.

107. Matthias Grünewald, Isenheim Altarpiece, circa 1515. Artbible. info, "Ishenheim Altar", Art and the Bible, http: //www. artbible. info/art/isenheim-altar. html.

108. Georges Rouault, Guerre, 1926. Jay Winter, Sites of Memory, Sites of Mourning: The Great War in European Cultural History (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), 175.

109. Georges Rouault, Head of Christ, 1939. Oil on paper pasted on canvas, 65 x 50 cm. The State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg, Russia. The State Hermitage Museum Digital Collection, http: //www. hermitagemuseum.org/fcgi-bin/db2www/ fullSize. mac/fullSize? selLang=English&dlViewld=NS5B5S%2B23JJ$5JA 1E$&size= small&selCateg=picture&dlCategId=GLBTRE%2B400OQF WN$F2&comeFrom=br owse.

110. Lee Miller, "Hot Line to God", Cologne, Germany, 1945. Antony Penrose, The Home of the Surrealists (London: Frances Lincoln, 2001), 55.

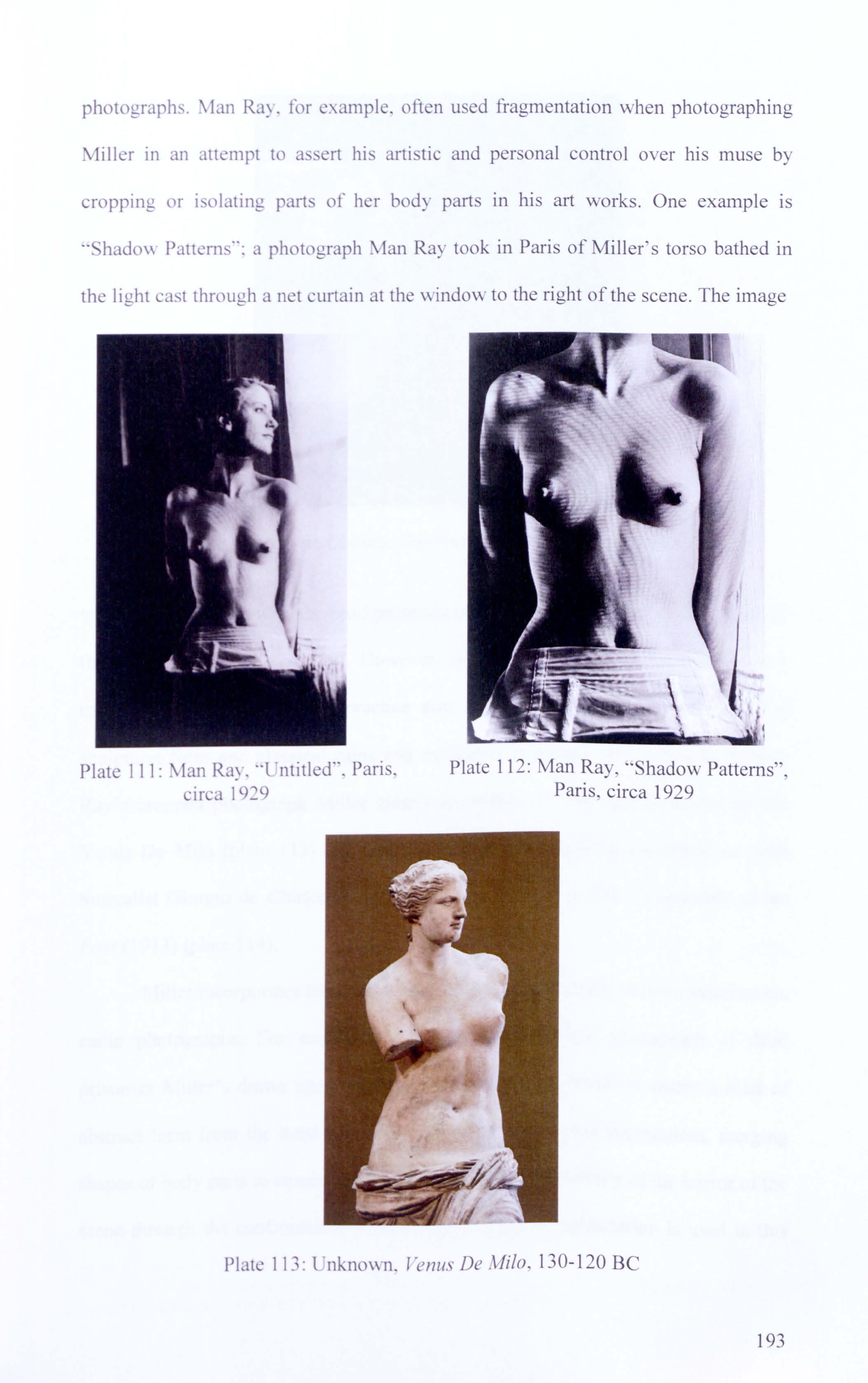

I 11. Man Ray, "Untitled", Paris, circa 1929. Rosalind Krauss and Jane Livingston, L'Amour Fou: Photography and Surrealism (New York and London: Abbeville Press, 1985), 143.

112. Man Ray, "Shadow Patterns", Paris, circa 1929. Gelatin silver print, 29.6 x 22.5 cm. Lee Miller Archives. Penrose,Lives of Lee Miller, 26.

113. Unknown, Venus De Milo, 130-120 BC. Parian Marble, H. 202 cm. Musee du Louvre, Paris. http: //www. louvre. fr.

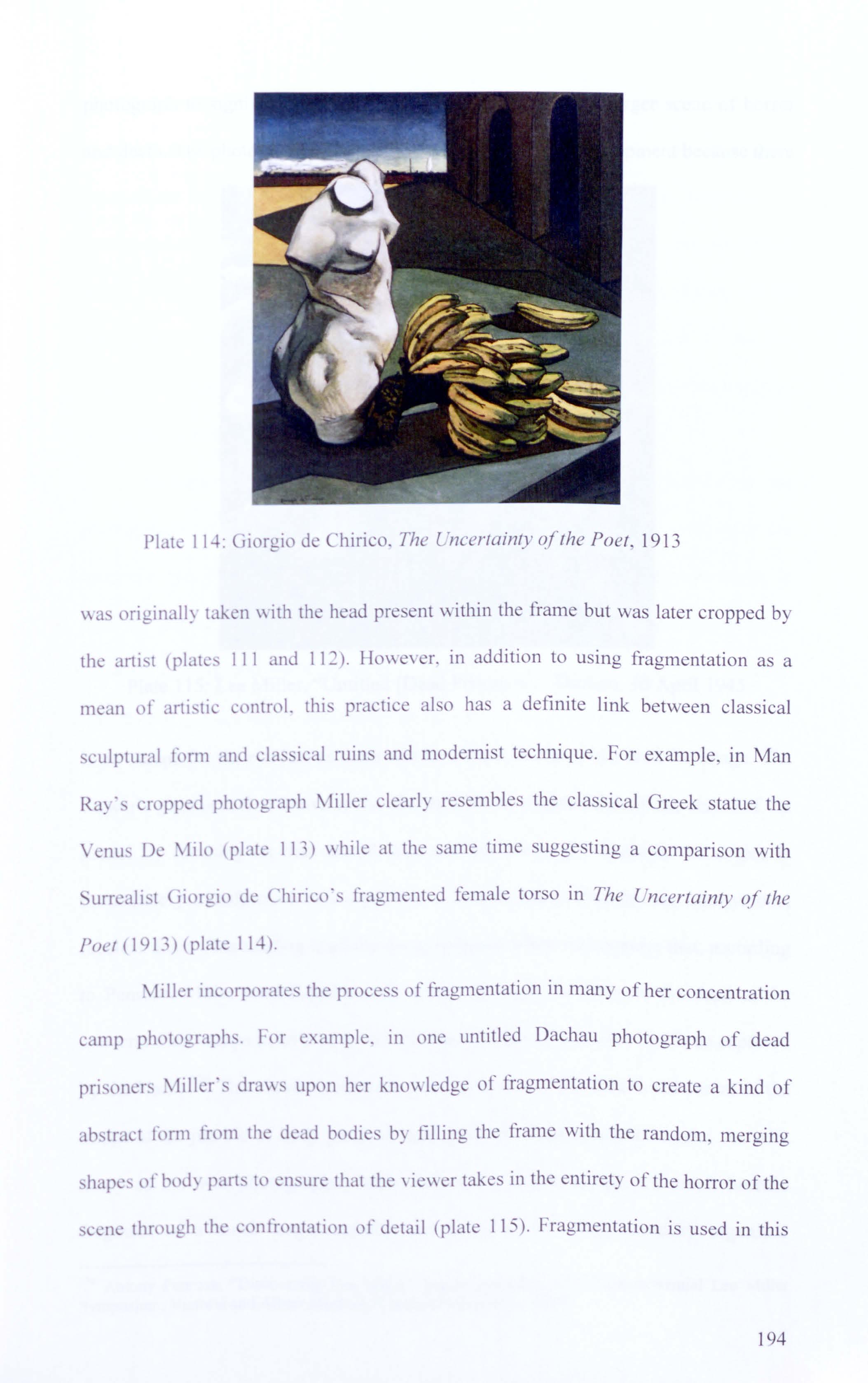

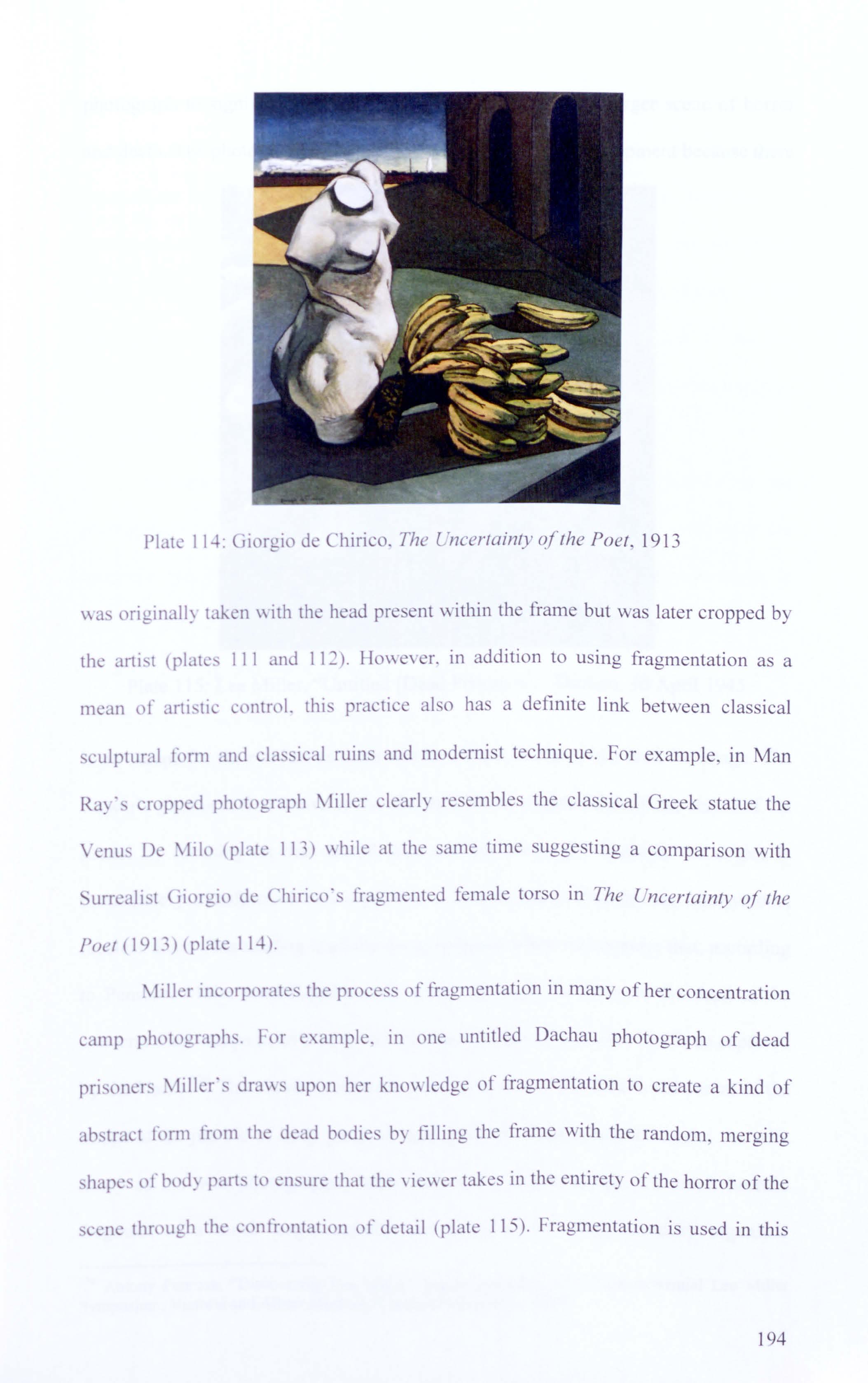

114. Giorgio de Chirico, The Uncertainty of the Poet, 1913. Oil on canvas, 1060 x 940 mm. Tate Collection, http: //www. tate.org.uk/servlet/ViewWork? workid=2204.

115. Lee Miller, "Untitled [Dead Prisoners]", Dachau, 30 April 1945. Penrose, Lives of Lee Miller, 140.

116. Lee Miller, "Germans Are Like This", Vogue, June 1945,102-103.

117. Lee Miller, "Untitled [Burned Bones of Starved Prisoners]", Buchenwald, April 1945. Lee Miller, "Germans Are Like This", 103.

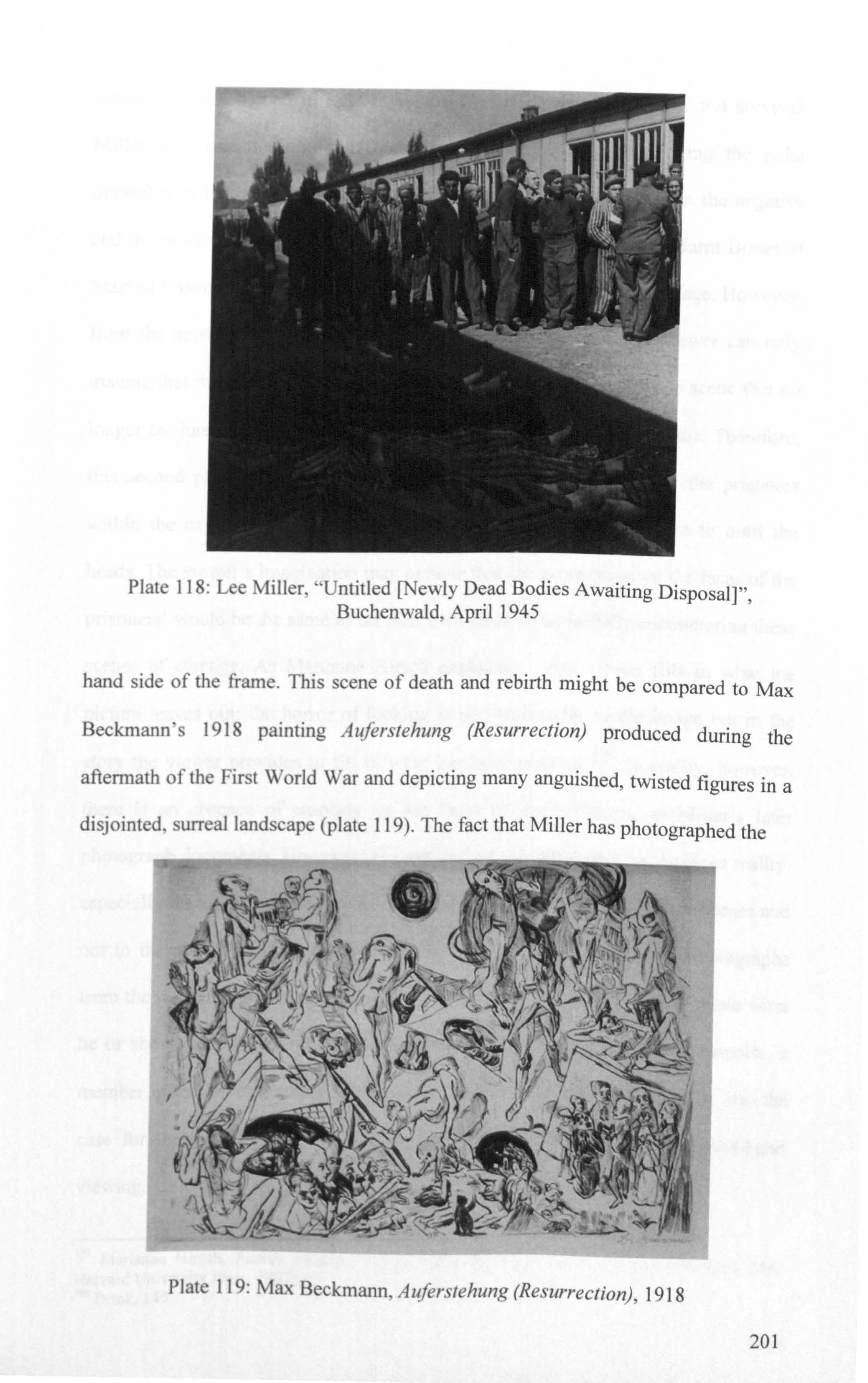

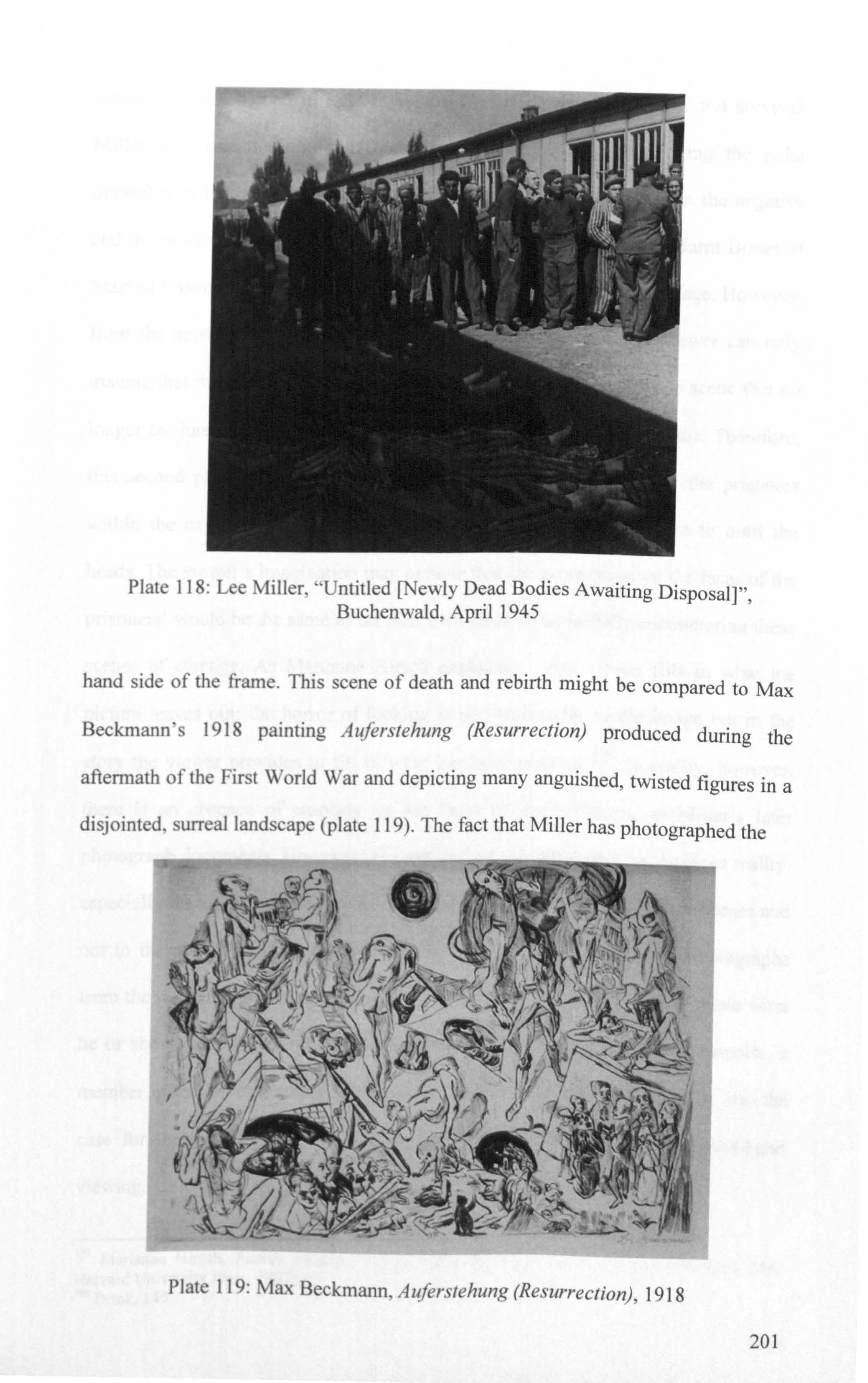

118. Lee Miller, "Untitled [Newly Dead Bodies Awaiting Disposal]", Buchenwald, April 1945.Penrose,Lee Miller's War, 185.

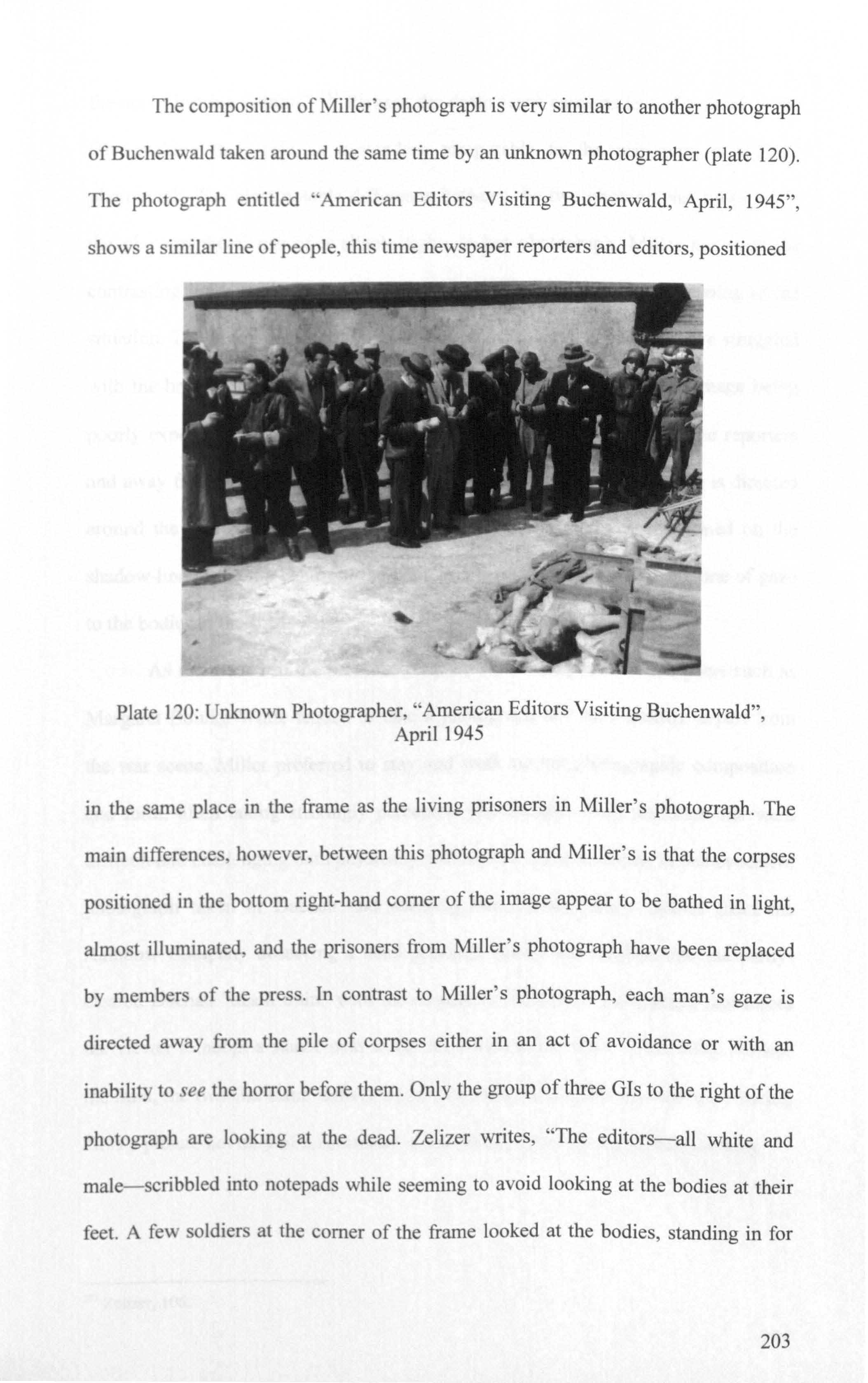

119. Max Beckmann, Auferstehung (Resurrection), 1918. Oil on canvas, 345 x 497 cm, Staatsgalerie, Stuttgart. "Max Beckmann", Art of the First World War, http: //www. art-wwl. com/gb/texte/I03text. html.

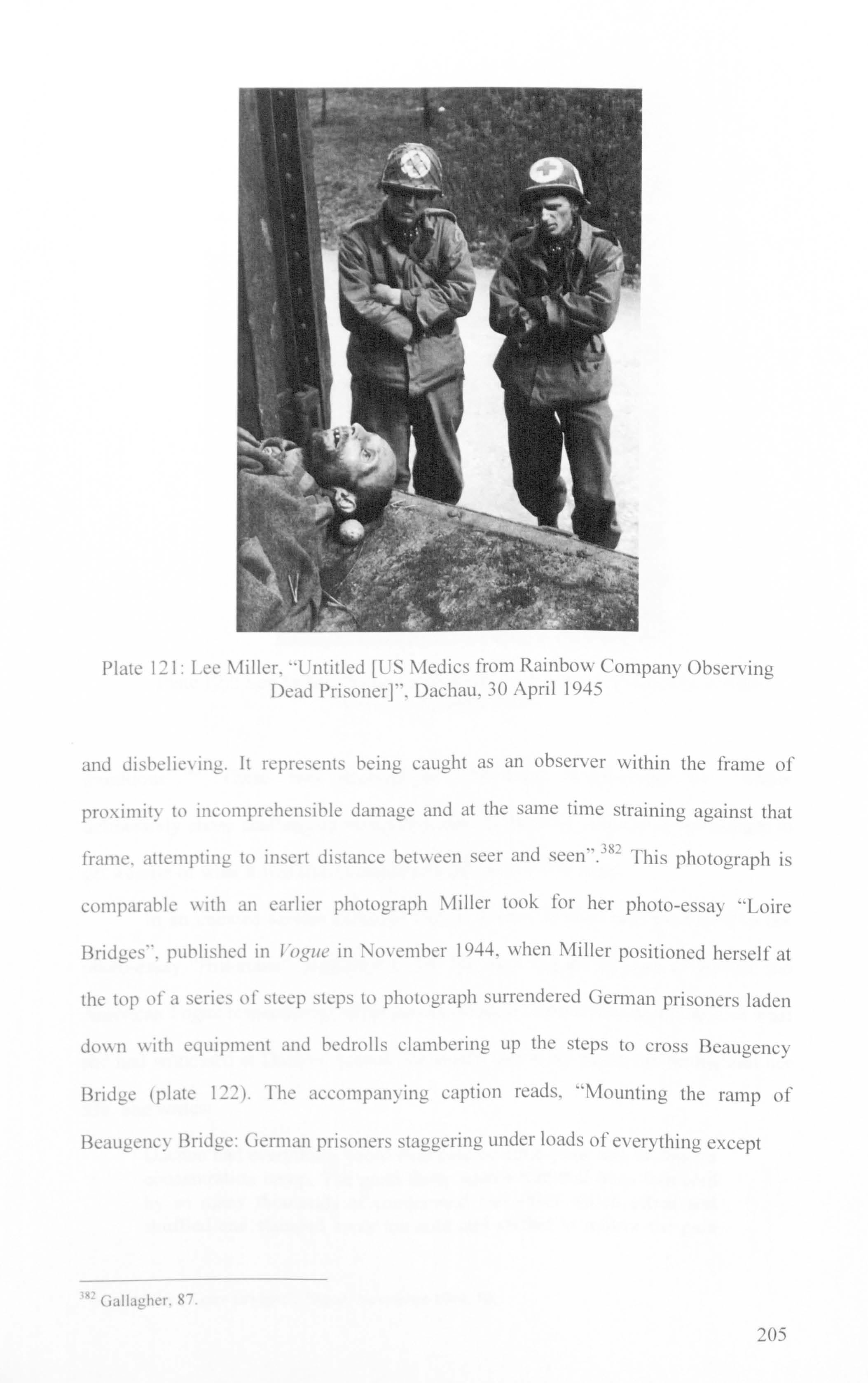

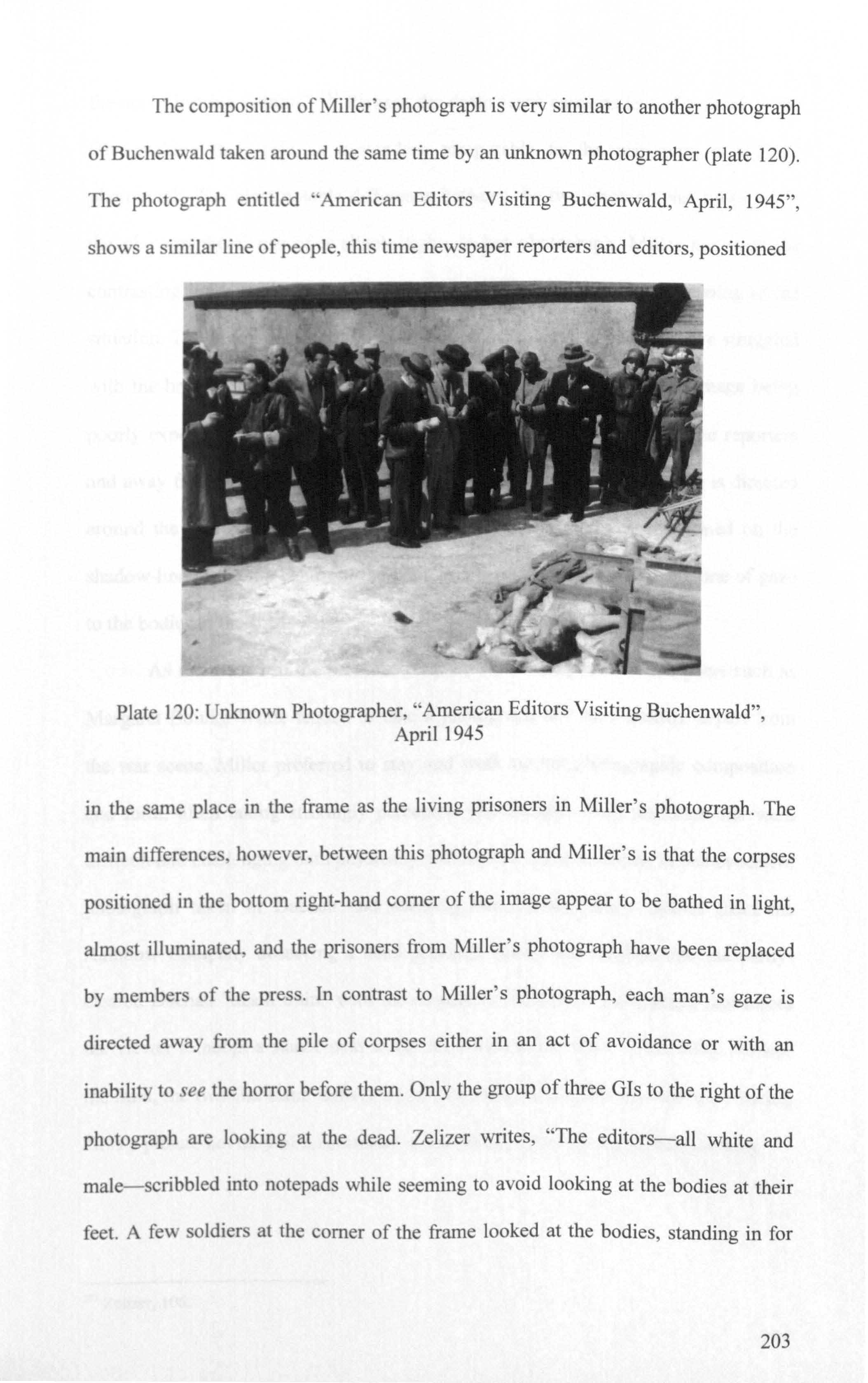

120. Unknown Photographer, "American Editors Visiting Buchenwald", April 1945. National Archives and Records Administration (NARA). This photographed appeared

xiv

on 3 May 1945 in both the Boston Globe under the caption "American Editors View Buchenwald Victims" and the Los Angeles Times as "Buchenwald". Barbie Zelizer, Remembering to Forget: Holocaust Memory Through the Camera's Eye (Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 1998), 107.

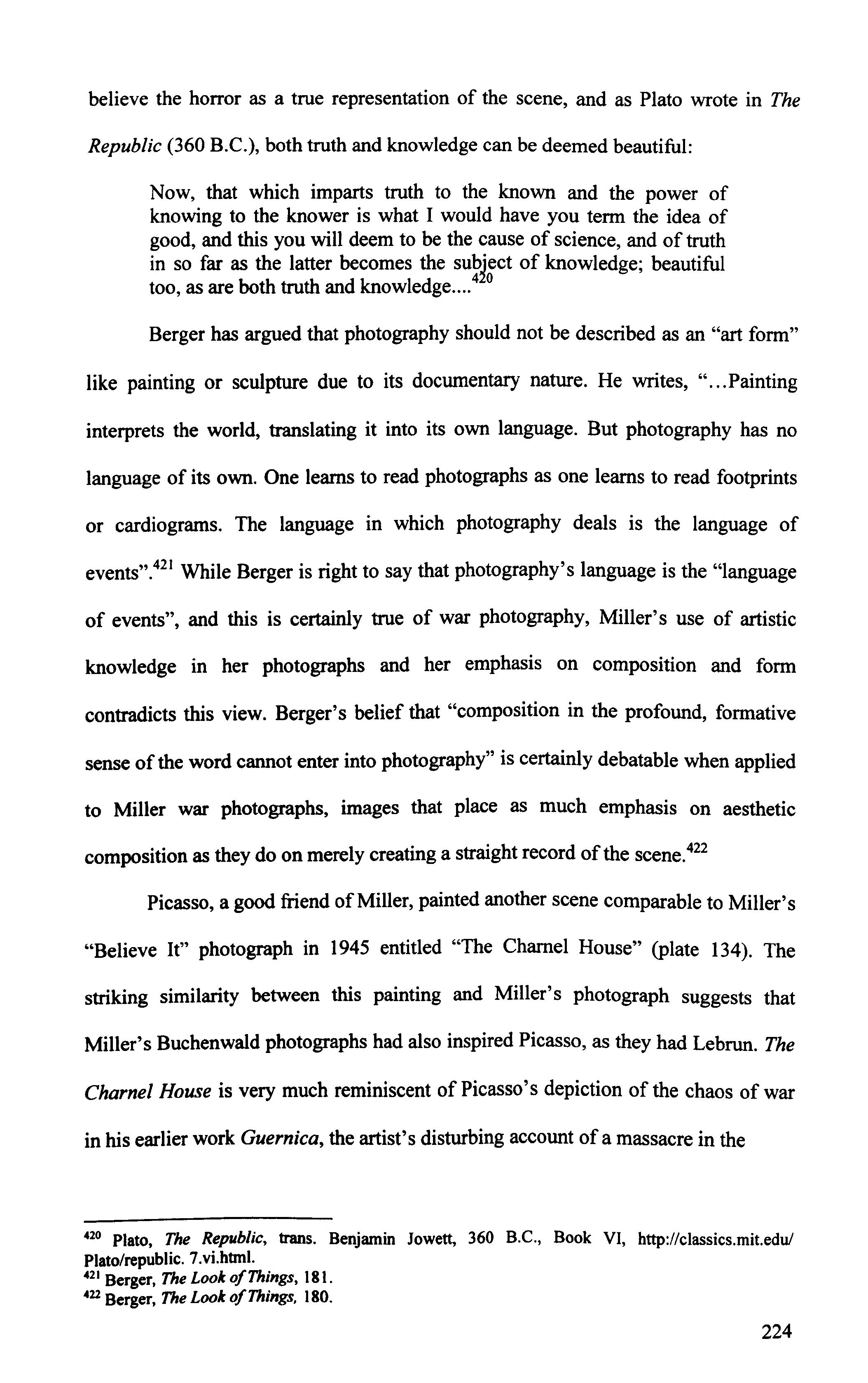

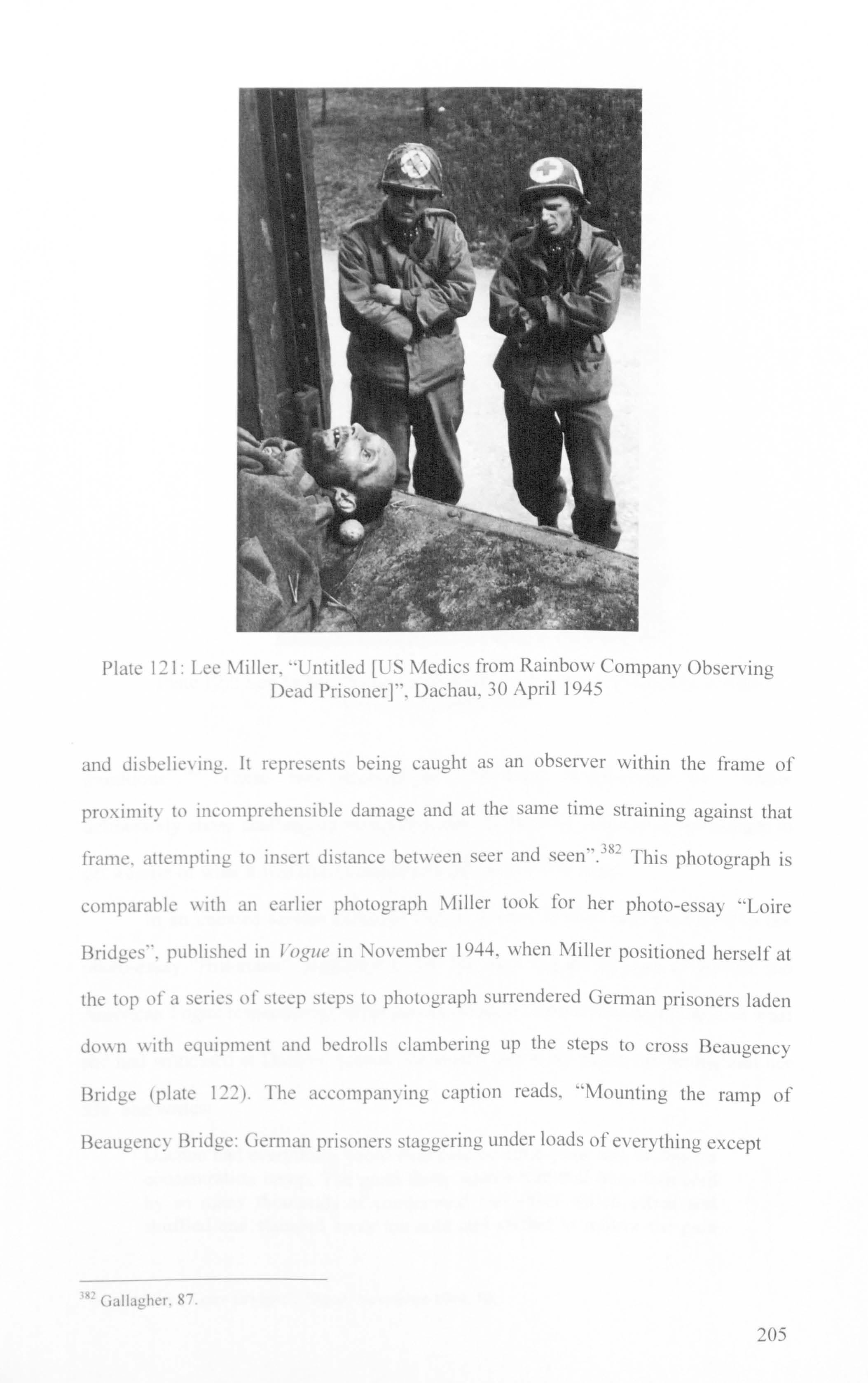

121. Lee Miller, "Untitled [US Medics from Rainbow Company Observing Dead Prisoner]", Dachau, 30 April 1945. Penrose,Lives of Lee Miller, 141.

122. Lee Miller, "Untitled [German Prisoners at Beaugency Bridge]", Loire, November 1944. Lee Miller, "Loire Bridges", Vogue,November 1944,50.

123. Lee Miller, "Untitled [Released Prisoner]", Buchenwald, April 1945. Slusher, 65.

124. Lee Miller, "Untitled [Beaten SS Guard]", Buchenwald, April 1945. Livingston, Lee Miller, Photographer, 84.

125. Lee Miller, "Untitled [Guards Beaten by Liberated Prisoners]", Buchenwald, April 1945. Livingston, Lee Miller, Photographer, 87.

126. Lee Miller, "Untitled [Defiant SS Guard in Prison Cell]", Buchenwald, April 1945. Penrose,Lee Miller's War, 165.

127. Lee Miller, "Untitled [Dead SS Guard in Canal]", Dachau, 30 April 1945. Haworth-Booth,196.

128. Hieronymus Bosch, The Carrying of the Cross, 1485-1490. Oil on panel, 76.7 x 83.5 cm. Musee des Beaux-Arts, Ghent. Mark Harden, "Hieronymus Bosch", The Artchive, http: // www. artchive.com/artchiveB/bosch/carrying. jpg. html.

129. Pieter Bruegel the Elder, The Triumph of Death, 1562-1563. Oil on canvas, 162 x 117 cm. Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid, http: //www. museodelprado.es/en/ education/education-proposes/15-interesting-details/pieter-bruegel-the-elder-thetriumph-of-death/.

130. Don McCullin, "Turkish Woman Grieving for Her Dead Husband", Cyprus, 1964. Mark Holborn, ed., Don McCullin (London: Jonathan Cape, 2003), 93.

131. Rico Lebrun, Floor of Buchenwald No. ], 1957. Casein and ink, 121.9 x 243.8 cm. Estate of Rico Lebrun. Van Deren Coke, The Painter and the Photograph: from Delacroix to Warhol (Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press), 111.

132.Lee Miller, "Untitled", Buchenwald,April 1945(croppedversion).Coke, 111.

133. Lee Miller, "Untitled", Buchenwald, April 1945 (original uncropped image). Lee Miller, "Believe It", Vogue, June 1945,104-105.

134. Pablo Picasso, The Charnel House, 1945. Oil and charcoal on canvas, 199.8 x 250.1 cm. The Collection, "Pablo Picasso", Museum of Modem Art, New York, http: //www. moma.org /collection/browse results.php?object_id=78752.

xv

135. Pablo Picasso, Guernica, 1937. Oil on canvas, 3.5 x 7.76 metres. Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, Madrid. The Collection, "Guernica", Museo Nacional Reina Sofia, http: //www. museoreinasofia.es/scoleccion/FormObra.php?idobra=32& idautor= 15.

Epilogue

136. Lee Miller, "Life Photographer David E. Scherman Equipped for War", London, 1943. Haworth-Booth, 165.

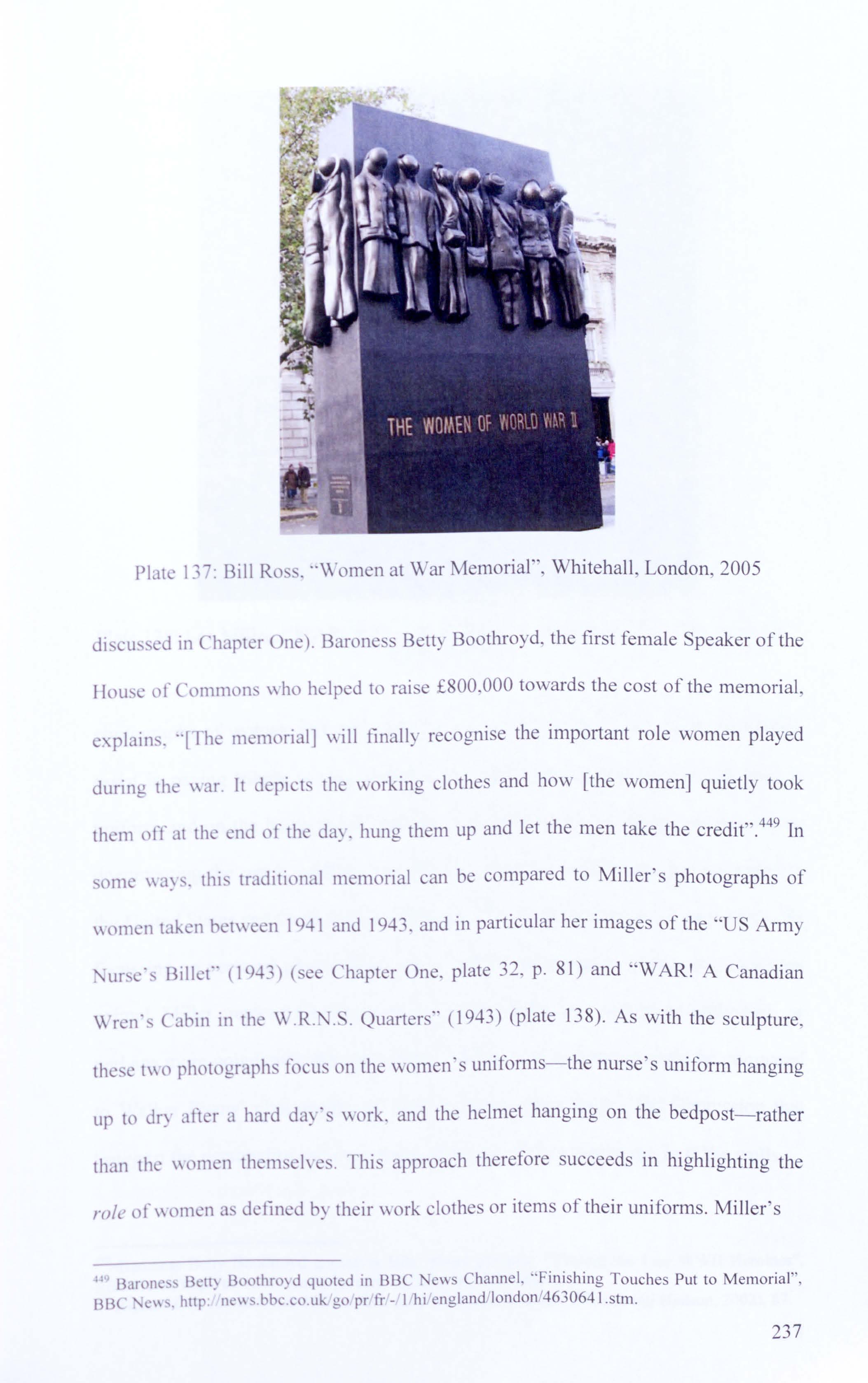

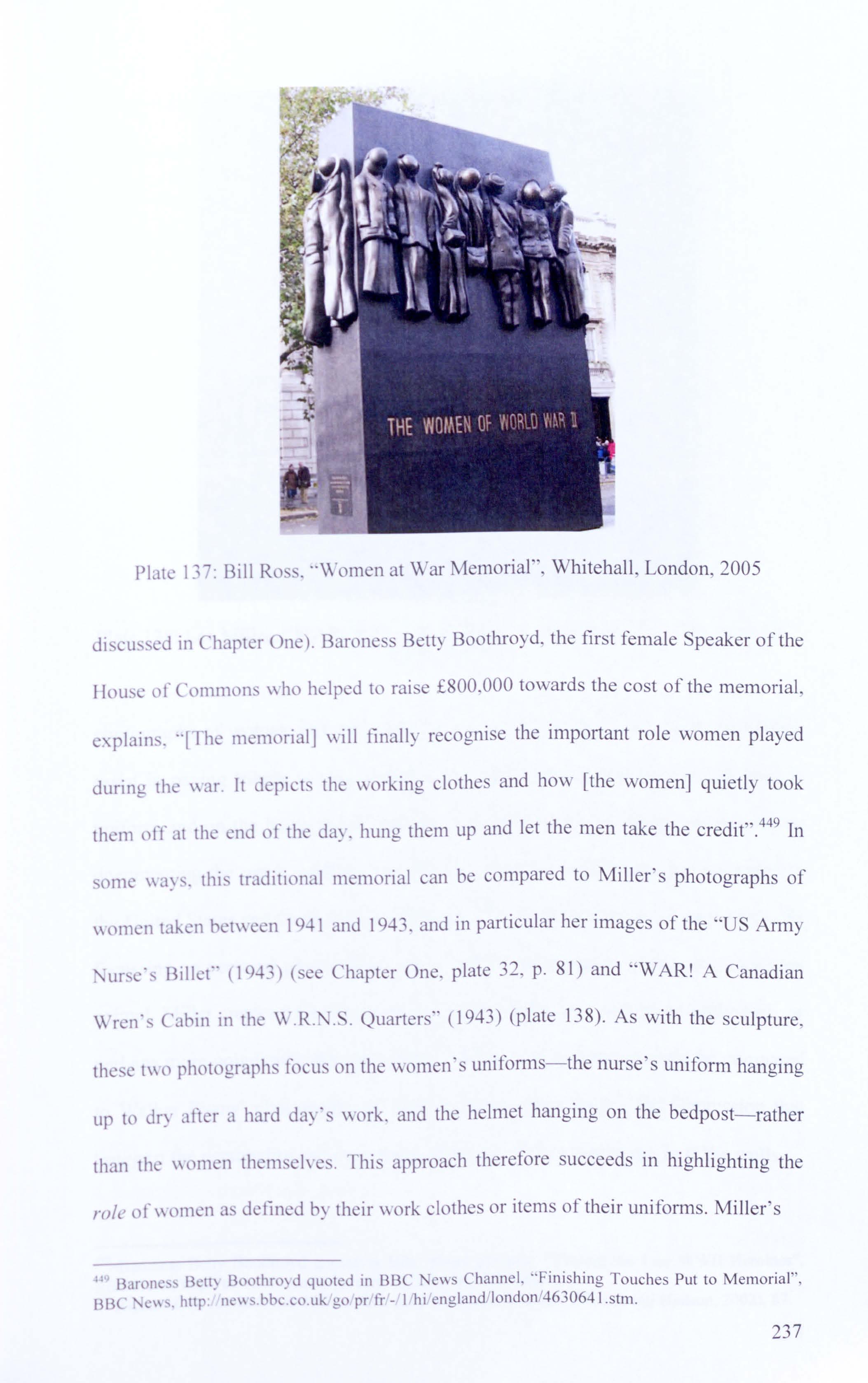

137. Bill Ross, "Women at War Memorial", Whitehall, London, 2005. Bill Ross, "WW2 People's War: An Archive of World War Two Memories - written by the public, gathered by the BBC", British Broadcasting Company, http://www. bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar/stories/ 84/a6589984.shtml.

138. Lee Miller, "WAR! A Canadian Wren's Cabin in the W. R.N. S. Quarters", London, 1943. Monochrome photograph, 16.5 x 16.4 cm. Miller, Wrens in Camera, 73.

139. Walker Evans, "Fireplace and Objects, Floyd Burroughs' Bedroom", Hale County, Alabama, 1936. Belinda Rathbone, Walker Evans: A Biography (Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1995), plate 16.

140. George Strock, "Three Dead Americans on the Beach at Buna", Papua New Guinea, 20 September 1943. Zelizer, 37.

141.Mathew Brady, "Dead Boy in the Road at Fredericksburg",3 May 1863.Orvell, 63.

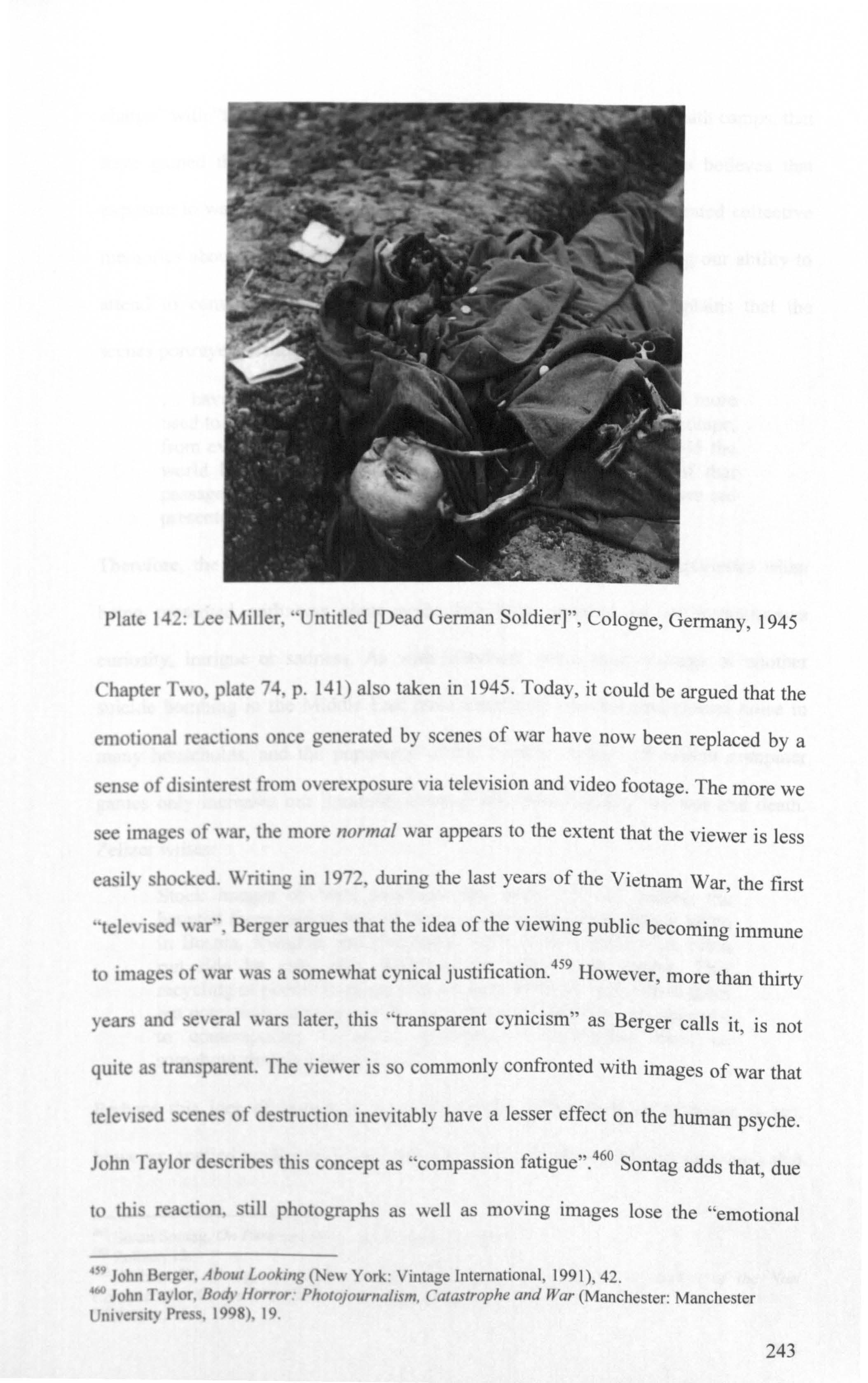

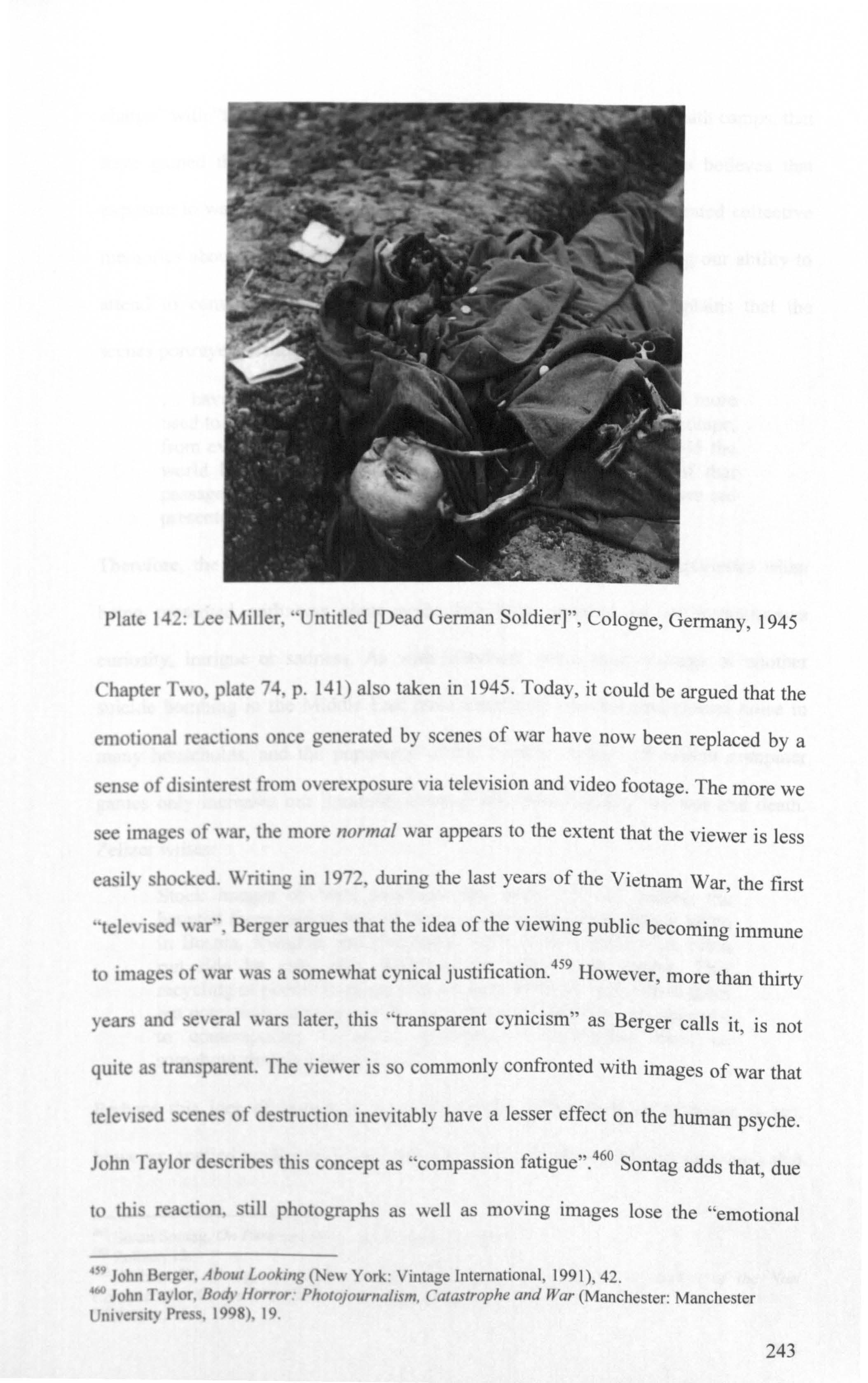

142. Lee Miller, "Untitled [Dead German Soldier]", Cologne, Germany, 1945. The caption reads, "This is a good German, he is dead. Artery forceps hang from his shatteredwrists". Penrose, Lives of Lee Miller, 134.

143. Lee Miller, "Untitled [US Bombs Exploding on the Fortress at St Malo]", France, 1944. SHAEF censorship stamp on reverse plus typewritten caption. Penrose, Lives of Lee Miller, 121. (Haworth-Booth has entitled the image "Bombs Bursting on the Cite d'Aleth", 181).

144. Lee Miller, "Untitled [Architectural Study]", Paris, 1931. Inscribed "lee miller Paris 1931". Haworth-Booth, 64.

145.Lee Miller, "Untitled [Walkway]", Paris,circa 1931.Inscribed"lee miller Paris". Penroserefers to this image as "Walkway" in Penrose,Lives of Lee Miller, 25. Haworth-Boothhasentitled it "Untitled [StreetScene]"in Haworth-Booth,78.

146. Lee Miller, "Untitled [Stairway]", Cairo, circa 1936. Signed in black ink on the print, 27.9 x 25.4 cm. Lee Miller Archives. Haworth-Booth, 127.

147. Lee Miller, "Untitled [Air-raid Warden in Window]", London, 1940. The air-raid warden has been identified as Freddie Mayor, founder of the Mayor Gallery in London that specialised in contemporary art. Calvocoressi, Portraits from a Life, 62.

xvi

148. Lee Miller, "Untitled [Hand in Silhouette]", Paris, 1931. Inscribed "lee miller Paris `31 $15 -". Philadelphia Museum of Art, museum no. 2001-62-816. HaworthBooth, 70.

149. Lee Miller, "St Malo", Vogue,October 1944,50.

150. David E. Scherman, "Lee Miller in Hitler's Bathtub", Prinzregentenplatz 27, Munich, 1 May 1945. Penrose,Lives of Lee Miller, 142.

151. David E. Scherman, "Lee Miller in Hitler's Bathtub", Munich, 1945. The caption reads, "Lee Miller, who scooped the story, luxuriates in Hitler's bath". Lee Miller, "Hitleriana", Vogue,July 1945,73.

152.Lee Miller, "Hitleriana", 36-37.

153. Lee Miller, "Untitled [Hitler's House the Berghof in Flames]", May 1945. Penrose,Lives of Lee Miller, 143.

154. Lee Miller, "Paris Under Snow", Vogue,January 1945. Haworth-Booth, 187.

155. Lee Miller, "Veiled Eiffel Tower", Paris, 1945. Livingston, Lee Miller, Photographer, 73.

156. Josef Sudek, "Prague in Winter", 1955. Eamonn McCabe, The Making of Great Photographs: Approaches and Techniques of the Masters (Newton Abbott, Devon: David and Charles, 2005), 61.

157. Henri Cartier-Bresson, "Place de l'Europe, Gare St Lazare", Paris, 1932. Henri Cartier-Bresson, Henri Cartier-Bresson: Aperture Masters of Photography (New York: Aperture, 1997), 39.

158. Edward Steichen, "The Flatiron", 1905. Mark Harden, "Edward Steichen", Masters of Photography, http: //www. masters-ofphotography.com/S/steichen/steichen flatiron full. html.

xvii

INTRODUCTION

Lee's Surrealist eye was always present. Unexpectedly, among the reportage, the mud, the bullets, we find photographs where the unreality of war assumes an almost lyrical beauty. On reflection I realise that the only meaningful training of a war correspondent is to first be a Surrealistthen nothing in life is too unusual. Antony Penrose, The Legendary Lee Miller (1998)I

Antony Penrose describes his mother, the American-born photographer Lee Miller (1907-1977), as "a paradox of irascibility and effusive warmth, of powerful talent and hopeless incapability. She loved to learn, create or take part, and then to move on to something else. Some of her `jags', as she called her current obsessions, would last only days; others stretched for years. Photography was her supreme jag, and she deserted it only when, after thirty years, she had exhausted all its abilities to provide excitement". 2 Miller's life and career was a complex mixture of "jags"; she was a polymorphic character, a chameleon with various personalities-teenage rebel, Vogue model, Surrealist's muse, studio portraitist, war correspondent, gourmet cook-and her photographs were just as complex and often contradictory in their hybrid form as combinations of Surrealist art and documentary. Miller could be

1 Antony Penrose, The Legendary Lee Miller: Photographer 1907-1977 (Chiddingly, East Sussex, England: The Lee Miller Archives, 1998), 19.

2 Antony Penrose, The Lives of Lee Miller (London and New York: Thames and Hudson, 1985), 8.

Plate 1: Unknown Photographer, "Lee Miller and Man Ray", circa 1930

pushed the boundaries both of art and war photography, often using unconventional methods (see, for example, Miller's modernist approach to lighting in her fashion photography as noted in Chapter One) to comment on such multifaceted issues as sex, gender, death, and war. In her role as war correspondent for Vogue magazine and one of the few female war photographers to see actual combat (the other notable example being American Life photographer, Margaret Bourke-White), 3 Miller uses her photographs of the Second World War to display what Penrose describes as an unforced "Surrealist eye", an artistic vision developed to great extent during her apprenticeship to Man Ray (plate 1) in Paris in the late 1920s and early 1930s-a relationship that enabled her to develop her knowledge of Surrealist art and photography, and that, in turn, helped her to create intriguing images of war that provide an aesthetically-shaped commentary of war. Therefore, in Miller's photographs art and documentary converge, resulting in images of war that can be interpreted as examples of "surreal documentary", thus supporting Steve Edwards' belief that "the document and the art-photograph are locked together: these are mutually determining categories that draw a great deal of their meanings from the antithetical relation". 4

The oeuvre of Miller's career as a photographer has only been publicly acknowledged and made available since her work came to light following her death

3 According to US Library of Congress records, Miller was only one of more than one hundred accredited US women war correspondents during the Second World War. Library of Congress, "Accredited Women War Correspondents During World War IIWomen Come to the Front: Journalists, Photographers, and Broadcasters During World War II", http: //www. loc.gov/ exhibits/wcf/wcJ0005.htm1. However, according to the Lee Miller Archives, only the US armed forces gave female photographers and correspondents formal accreditation (official status and rank). Most women war correspondents were not permitted to report on combatant events. However, on her second assignment at the siege of St Malo, Miller spent four days covering the battle, resulting in her arrest for violating the terms of her accreditation. Unlike Bourke-White, who worked mainly with the US Air Force, Miller's distinction was that she mainly reported the infantry war, in many cases from the front line. From a conversation with Antony Penrose at the Lee Miller Archives, Farley Farm, Chiddingly, East Sussex, 9 July 2003.

4 Steve Edwards, Photography: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), 14.

2

on 21 July 1977. Prior to that year, evidence of her fascinating past had been hidden away in cardboard boxes in her East Sussex farmhouse, Farley Farm (now home to the Lee Miller Archives), and forgotten about. Antony Penrose, Miller's only son, had been unaware of the extent of his mother's photographic career and the quality of her work: "I knew she was handy with a camera when I was little-but that was about it. She never talked about the war". 5 It was only during the year of Miller's death, when her daughter-in-law, Susanna,went into the attic of Farley Farm to find some photographs of her husband as a baby to show their children, that the full scope of Miller's work emerged when the boxes of approximately 60,000 photographs, negatives, original Vogue manuscripts and correspondence were rediscovered.

Penrose reveals in the postscript of his biography The Lives of Lee Miller, the first substantial biography specifically on Miller and published in 1985, that his volatile relationship with his mother that resulted in many years of estrangement meant having to get to know her again when writing of her life and work. He writes:

The Lee I discovered was very different from the one I had been embattled with for so many years, and I am left with the profound regret that I did not know her better. This regret is bound to be shared by many, as Lee revealed only a small part of herself to any one person. It has often been those who were closest to her who have been given the biggest surprises by my research almost as though Lee had carefully planned a little posthumous mischief. 6

It has, therefore, taken Penrose years of piecing together the available fragments of her life from the boxes, along with an inevitable frustration, to create an accurate picture of Miller's character, life and career. Penrose's long, ongoing search to discover "Miller the photographer" and rediscover "Miller the mother" is perhaps the foremost reason why it has taken so long for any substantial scholarly research to be published and why The Lives of Lee Miller has become one of the key non-scholarly

SAntony Penrose quoted in Janine Di Giovanni, "What's a Girl to Do When a Battle Lands in Her Lap?" The New York Times, 21 October 2007, http: //Www. nytimes. com/2007/10/21/style/ tmagazine/21miller. html.

6 Penrose,Lives of Lee Miller, 214.

3

sources for subsequent research on Miller. Although, characteristically, Miller was quite modest, and at times even dismissive, about her photographic accomplishments, Penrose has suggested that Miller must have been fully aware of the legacy she would be leaving behind and wished it to be preserved like a kind of time capsule only to be explored after her death.7

Richard Calvocoressi, author of Lee Miller: Portraits from a Life (2002), believes that there are three additional reasons for this apparent neglect of Miller's photographic work. Firstly, Miller's long loyalty to Vogue, for whom she worked as a model, photographer and war correspondent from 1927 until the mid-1950s, made it difficult for her to establish herself as a successful independent artist. Secondly, she did very little to promote her own work, having only one solo exhibition during her lifetime (at the Julien Levy Gallery in New York in 1933).8 Finally, her polymorphic career and fascinating life, while invaluably informing readers of her development as a photographer and a war correspondent, has often tended to overshadow her photographic work and talent as an artist.9 Therefore, it is important that Miller's photographic work, as opposed to her colourful life and varied career, continues to be explored in detail with a more in-depth, critical and theoretical analysis of her photographs.

Whatever the reasons for the delay in acknowledgement prior to the publication of Penrose's book, since 1985 interest in Miller's life and the popularity of her work has increased considerably through a number of significant exhibitions and publications, and this rising awarenessof Miller is another reason why a thesis of Antony Penrose,"FrequentlyAsked Questions",Lee Miller Archives,http://www. leemiller. co.uk. BLee Miller, Exhibition of Photographs ran from 30 December 1932 until 25 January 1933. The New York Post reviewed the exhibition describing Miller's photographic work as "quite direct and individual, with no hint of fashionable follies" and "as fresh and invigorating to the beholder as if he had never enjoyed the wonders of the camera plus brains before". Katherine Ware and Peter Barberie, Dreaming in Black and White: Photography at the Julien Levy Gallery (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art / Yale University Press, 2006), 80-81.

9 Richard Calvocoressi, Lee Miller: Portraits from a Life (London: Thames and Hudson, 2002), 6.

4

this nature is important at this particular time. An exhibition of Miller's portraits that coincided with the paperback publication of Calvocoressi's book was held at London's National Portrait Gallery from February to May 2005; and a comprehensive biography by Miller's official biographer, Carolyn Burke, was published in November 2005. Miller has been the subject of a musical entitled Six Pictures of Lee Miller that had its world premiere in July 2005 at the Chichester Festival Theatre; and she became the central "character" in a play entitled The Angel and the Fiend, written by Antony Penrose and based on the words of Miller, Man Ray, Roland Penroseand David E. Scherman10.Even a film of her life, written by the English playwright Sir David Hare, has recently been devised. In addition, a major retrospective at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London entitled The Art of Lee Miller took place in 2007,11 signifying a great milestone in Miller's legacy by marking the one-hundredth anniversary of her birth and the thirtieth anniversary of her death. However, it seems that Miller's gradual rise in popularity has been, to some extent, only a surface interest that often demonstrates a fascination with her colourful life rather than a true appreciation of her work as a photographer. As Mark Haworth-Booth, curator and author of The Art of Lee Miller (2007) comments, "I'm not sure people in some quarters have taken her that seriously as a photographer but she made a number of photographs that no one else made. They came out of something inside her that was unique", 12and as Harry Yoxall, Head of British Vogue magazine, asked after the Second World War, "Who else has written equally well about GIs and Picasso? Who else can get in at the death at St Malo and the rebirth of

10The Angel and the Fiend debuted in 2003 and continues to accompany many major exhibitions of Miller's work, including the recent exhibition The Art of Lee Miller at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

11The Art of Lee Miller exhibition ran from 15 September 2007 until 6 January 2008. The exhibition then travelled to the Philadelphia Museum of Art (from 26 January to 27 April 2008), the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (from 1 July to 21 September 2008), and the Galerie nationale du Jeu de Paume, Paris (from 14 October 2008 to 11 January 2009).

12Mark Haworth-Booth quoted in Louise Jury, "Lee Miller's Tale of Bohemia Celebrated in New V&A Photographic Exhibition", London Evening Standard, 13 September 2007.

5

the fashion salons? Who else can swing from the Siegfried line one week to the new hip line the next?"13 In this respect, a thesis that focuses specifically on Miller's war photography, concentrates on some of her lesser-known photographs, and explores her juxtapositions of Surrealist art and documentary rather than her biography, is an essential contribution to any future scholarly work on Miller's Second World War photographs.

This Introduction will consist of a Literature Review to outline the key sources available specifically on Miller-the biographical, art historical, scholarly and commercial-and a discussion of their value in the continuing research and understanding of Miller's photographic work. I will then state the aims of the thesis followed by a methodology and an explanation of the key concepts used throughout the chapters. Finally, I will explain the structure of each chapter and outline the key photographs, issues and concepts to be explored.

Literature Review

When I first began my research on Lee Miller in 2002 it quickly became apparent that sources written primarily on Miller were few and far between, and those that were available tended to omit or obscure the true quality and importance of her photography, avoiding any in-depth analysis of the Surrealism-inspired content of her war photographs in particular. Most of these early sources, such as Jane Livingston's Lee Miller, Photographer (1989), for example, published four years after Antony Penrose's The Lives of Lee Miller and only the second book to focus specifically on Miller's photographic work, were merely exhibition catalogues produced to accompany an exhibition of Miller's work. 14In comparison to Penrose's 13Carolyn Burke,Lee Miller (London and New York: Bloomsbury,2005),xii. 14Jane Livingston's work was published to coincide with a retrospective travelling exhibition that began at the Corcoran Gallery in Washington, D. C. in February 1989.

6

biography, Lee Miller, Photographer is a combination of text and photographs illustrating Miller's life and work. As a research source, the book is well written and informative, although, as one of the first substantial works on Miller, Livingston unavoidably draws considerably on Penrose's book for much of her information.

Without being overtly critical of Penrose's long struggle with the material available on Miller and his constructive research since 1977, it should be noted, however, that due to the fragmented nature of Miller's archive and her estrangement from her son, much of Penrose's research is unavoidably based on limited resources and some inevitable speculation. Consequently, there are some sources on Miller that have had to draw upon an element of assumption. Livingston honestly acknowledges her dependency upon The Lives of Lee Miller and largely biographical material in the Afterword to her book by stating, "I have drawn liberally on this resource, and on Sir Roland Penrose's autobiographical book, Scrap book, 1900-1981,1981. "15 This reliance on Antony Penrose's research ultimately encourages some criticism of Livingston's text as a dependable scholarly source. However, the lack of sources and organised archival material available at the time of writing in the late 1980s made it very difficult to conduct any in-depth, indeed original, research on her subject. In addition, the awkward layout, along with the lack of text, does produce a frustrating read, although Livingston may have had limited control in this area, and it becomes evident from the restricted content that a further body of material on Miller is needed and more scholarly work written in order to fill the gaps in the research.

One particularly useful source on Miller's war work is Penrose's Lee Miller's War (1992), based on Miller's original Vogue manuscripts and the selected war correspondencenow housed at the Lee Miller Archives. Although the book is edited by Penroseto incorporate an accumulation of additional notes, letters, and telegrams

15Jane Livingston, Lee Miller, Photographer (London: Thames and Hudson, 1989), 170.

7

written by Miller during the latter years of the war, the text contains quite an insightful elucidation of Miller's character by Miller's close friend and colleague, David E. Scherman, the American Life photographer who accompanied Miller on many assignments during the war and shared Miller and Penrose's London flat at 21 Downshire Hill during the early 1940s. However, the book could have benefited from drawing more closely on the original Vogue photo-essays, including a more thorough discussion on the selection of the photographs and layout of the articles, something Mark Haworth-Booth includes in some depth fifteen years later in The Art of Lee Miller (2007). Nonetheless, Lee Miller's War is by far the most comprehensive account of Miller's war work from 1941 to 1945, and it attempts to portray Miller's vision as an inspiring journalist as well as an accomplished Vogue photographer.16 The majority of the book, however, consists of articles (mostly reconstructed from the original manuscripts by Penrose with assistance from Scherman) written by Miller to support her photographs, and originally published in Vogue, thus broadening the magazine's content from being exclusively fashion orientated. However, these articles not only show Miller's ability to write vividly of the sights she witnessed during the war but also reveal, to some extent, an element of her complex character and personality, such as Miller's animated description of the bombs dropping on the citadel of St Malo, as discussed in the Epilogue (see pp. 246247).

The photographs in Lee Miller's War are not only useful as historical records of war, however. Some also reveal the inevitable technical difficulties encountered by Miller, often resulting in numerous out-of-focus shots, photographs taken in poor lighting and with inaccurate exposure, amongst other things. However, considering the circumstances and the lack of modem equipment available, the photographs, like 16It hasoften beenforgottenthat Miller wrote muchof the accompanyingtext for her photographs and thequality of her writing shouldthereforebe taken into account.

8

Robert Capa's blurred images of the D-Day landings in June 1944, effectively reflect the intense drama and chaotic nature of war. 17Nonetheless, neither Lee Miller's War nor The Lives of Lee Miller provides any useful bibliographical information, citing only a handful of sources, a shortcoming that again questions the accuracy and reliability of the content. Indeed, the majority of the material cited in the writing of both books tends to be reliant upon primary sources housed at the Lee Miller Archives.

In 1998, Penrose produced a shorter biographical history of Miller (28 pages) entitled The Legendary Lee Miller: Photographer 1907-1977 (1998) that was published through the Lee Miller Archives to coincide with the New Zealand and Australian tour of the exhibition "The Legendary Lee Miller - Photographs 19291964" in 1998 and 1999. The biography is essentially a short essay by Penrose entitled "Lee MillerMuse and Surrealist Artist", accompanied by selected photographs, a chronology of her life, a list of photographs exhibited on the tour, an exhibition history of Miller's work, and a very short bibliography. There is, however, a very useful technical note following the bibliography indicating the photographic equipment Miller used for the majority of her work. In fact, The Legendary Lee Miller is the first source, except for a few observations by Jane Livingston in Lee Miller, Photographer, to elaborate upon the technical aspects of Miller's work, even though the information is restricted to two short paragraphs at the end of the booklet.

For a more targeted approach to Miller's work, Richard Calvocoressi's Lee Miller: Portraits from a Life concentrates on Miller's portrait photography specifically, including some war portraits, and contains some previously unpublished " For example, Miller's out-of-focus but strangely amusing photograph of a badly burnt GI bandaged from head to toe taken at the 44th Evacuation Hospital in Normandy, France, in 1944. Antony Penrose, ed. Lee Miller's War (London: Conde Nast Books, 1992), 18-19.

9

images.'8 In Portraits from a Life, Calvocoressi assigns Miller's portraits to one of six main categories: commissioned sophisticated studio portraits of film stars, actors, models and society figures; more informal portraits of artists, writers, scientists and other intellectuals shot on location for Vogue; private portraits of friends, mostly artists; portraits of people, often unidentified, engaged in work or in action, taken on assignment in various locations for Vogueor for commissioned books such as Wrens in Camera; portraits of civilians, including victims of persecution and their oppressors (for example, Miller's portraits of beaten SS guards that resemble prison "mug shots" [see Chapter Three, p. 209]); and probably the most obscure category, the portraits of absent individuals who are represented by objects associated with them (for example, Miller's portraits of Picasso's studio and Joseph Cornell's surrealist `objects'). 19 Each photograph is accompanied by a brief but useful descriptive caption as opposed to just the title and date. Calvocoressi also includes quite a lengthy introduction, "An Unflinching Eye", which, while briefly providing an overview of biographical detail, examines Miller's portraiture in some depth. There is, in addition, a short but informative bibliography that cites the important key texts. Although the book may appear to be limiting Miller's work primarily to portraiture, the diverse nature of the portraits, which span Miller's entire career, is not solely restricted to her formal studio work, as Calvorcoressi indicates by placing the work into one of the aforementioned six categories in order to show the range of her photographic work.

Since 2005, a number of more scholarly texts on Miller have been published that have started to piece together more of the fragments to create a fuller picture of

IS

Richard Calvocoressi is the former Director of the Scottish National Gallery of Modem Art in Edinburgh and was the curator of Miller's photographs for "The Surrealist and the Photographer: Roland Penrose and Lee Miller", an exhibition held at the gallery from 19 May to 9 September 2001. A book to accompany the exhibition, with a Foreword by Antony Penrose, was published in 2001. " Calvocoressi,"Portraits from a Life", 9.

10

Miller life and photographic career. Carolyn Burke's 2005 biography, for example, contains in-depth research on Miller's complex life, drawing from a wide range of sources besidesthe archival material. The lengthy biography is evidence that Burke's book is not wholly reliant on The Lives of Lee Miller, and the substantial biography proves that Burke has drawn upon a wide variety of biographical and historical sources for accuracy and depth. Katherine Slusher's Lee Miller and Roland Penrose: The Green Memories of Desire (2007), on the other hand, attempts to do what Antony Penrose had originally done in his later books The Home of the Surrealists (2001)20and The Surrealist and the Photographer: Roland Penrose and Lee Miller (2001) (another exhibition catalogue), by paying mirroring homage to both Miller and Penrose's artistic achievementsand to give "an unprecedented insight into one of the most fascinating artistic relationships of the twentieth century". 21 In her book, Slusher does attempt to provide a more analytical reading of Miller's images, and includes several previously unpublished images, although the length of the book (a mere ninety-six pages, including illustrations) limits the scope for a detailed scholarly analysis.

Mark Haworth-Booth's The Art of Lee Miller is perhaps the most scholarly source that endeavours to produce a more thorough analysis of Miller's war photographs as works of "art" while considering them within a Surrealist context. I would generally agree with Ali Smith that Haworth-Booth's book is "by far the fullest and most satisfying consideration yet of Miller's art and Miller as artist. Beautifully illustrated, with many images that haven't been widely available before, it is a work of proper appraisal, particularly good on areas of her work that have, until

20The Home of the Surrealists is a fascinating historical study of Farley Farm. Now the Lee Miller Archives, which, due to Roland Penrose's influence and connections in the art world, Farley Farm became home to one of the most impressive modern art collections in Europe. 21Antony Penrose, Foreword, The Surrealist and the Photographer: Roland Penrose and Lee Miller (Edinburgh: National Galleries of Scotland, 2001), 7.

11

now, pretty much escaped critical attention". 22 Published to coincide with the retrospective exhibition at the V&A, Haworth-Booth's book is more that just a glorified exhibition catalogue; he analyses Miller photographs, such as Portrait of Space (1937), in a way no other researcher of Miller's work has done before, giving her photographs a scholarly reading and placing them into an historical and cultural context (such as the useful inclusion of the original Vogue spreads). Therefore, The Art of Lee Miller has somewhat succeeded The Lives of Lee Miller as the primary source for future research of Miller's photographic work by reproducing many previously unpublished works and analysing them as works of art-for example, Haworth-Booth's comparison of two Parisian street scenes, one of which Miller rotated through 90 degrees to "reconfigure the dreamlike sceneinto a nightmare". 23

While the most recent secondary sources on Miller, such as Haworth-Booth's book, have been of significant value in the writing of this thesis, the Lee Miller

Archives and accessto primary sources have been invaluable for this research. When I first visited the archives in August 2003 the majority of the primary material was still in the process of being archived and catalogued with handwritten notes on index cards relating to the many filing cabinets of negatives and prints (many of the prints copied from the original negatives by the archives' curator and printer, Carol Callow). Digitisation would only commence several years later. It was a timeconsuming process and even now, with many of Miller's photographs, original notes and correspondence now available digitally, it is still very much apparent that there are areas of Miller photographic oeuvre, including her Second World War photographs, that require further intensive research.

22Ali Smith, "The Look of the Moment". The Guardian, 8 September 2007, http: //www. guardian. co.uk/books/2007/sep/08/photography. art.

23Mark Haworth-Booth, The Art of Lee Miller (London: V&A Publications, 2007), 77-79.

12

Aims

The aims of this thesis are two-fold. The main aim is to demonstrate how Miller's Second World War photographs can be interpreted as visual juxtapositions of Surrealist devices and socio-historical reportage-photographs in which, as Carolyn Burke describes, "[Miller's] Surrealist imagination meets a shattered reality head-on".24 However, the juxtaposing of art and war photography is not a straightforward process, and the complexities and contradictions of combining these two seemingly diverse forms of media will be revealed through an analysis of Miller's photographs. I will establish how Miller's war images and photo-essays, many of which were originally published in Vogue magazine during the latter years of the war, often illustrate her in-depth knowledge and experience of various art forms and art works besides Surrealism, knowledge that she was able to utilise in order to create distinctive representations of war through her unique artistic amalgamation of subject, composition, form and text. As examples of documentary photography, Miller's war photographs are also explored within their cultural and socio-historical contexts to establish how Miller, as well as drawing on her artistic background, was able to produce photographs that are both social and historical records of the Second World War period as well as examples of war art. In addition, through an analysis of the complex relationship between the Surrealism-inspired and documentary elements of Miller's war photographs, I will ascertain how Miller produces revealing and often controversial photographic representations of such diverse issues as gender, sex, war and death. For example, in Chapter One I will demonstrate how Miller's photographs divulge the dramatic social effects of the war on women and their traditional roles, predominately those roles of wife and mother, by documenting how women adopted temporary masculine 24Burke, xiv.

13

working identities as they were encouraged by the British government to contribute to the war effort. In Chapters Two and Three, Miller's unconventional approach to photography is also revealed in her witty interpretations of the destruction caused during the London Blitz and, perhaps most controversially, in her evocative and informative yet artistically daring approach to documenting the consequencesof the atrocities committed at Dachau and Buchenwald.

By concentrating on these specific aims, I will establish that through her essentially modernist approach shown by her ability to break with convention, Miller, unlike many of her contemporaries (both male and female), was able to draw upon a well-developed artistic background in her surreal documentation of the events and consequencesof the Second World War. The result is a series of distinctive, artistically informed interpretations of war photographed with the presence of a Surrealist eye, a need to inform and often provoke, a great sensitivity, and technical excellence.

Methodology

To engage in a project of this nature, it is important to identify a clear framework on which to base any photographic analysis. In order to meet the objectives of this thesis, and due to the limitations in resources specifically on Miller, I will analyse Miller's photographs by applying various aspectsof art, photographic, aesthetic, feminist and gender theory, as outlined below.

While referring to the key sources written specifically on Miller (Burke, Haworth-Booth, Penrose, for example), much of the photographic theory in this thesis will draw on sources such as Susan Sontag's Regarding the Pain of Others (2003), an excellent scholarly study for analysing images of war and destruction and their significance as artistic and documentary artefacts. John Tagg's The Burden of

14

Representation: Essays on Photographies and Histories (1988) is used for his interpretation of various forms and uses of photographic portraiture and the use of photography within a socio-historical context. Roland Barthes' Camera Lucida (1980), John Berger's Ways of Seeing (1972) and About Looking (1980), and Geoff Dyer's The Ongoing Moment (2005) will also be applied as background texts providing guidance on how to read and interpret a photographic image, especially Berger's "absence" theory as noted in Way of Seeing and used, to an extent, in my interpretation of Miller's concentration camp photographs. John Taylor's critical analysis Body Horror (1998), an exploration into the use of photography as propaganda and the publication of and reaction to images of death and destruction in the press, Shelley Hornstein and Florence Jacobowicz's edited collection of essays

Image and Remembrance: Representation and the Holocaust (2003) and Janina Struk's Photographing the Holocaust: Interpretations of Evidence (2004) will all be considered in relation to Miller's photographic representations of Buchenwald and Dachau.

For analysing Miller's photographs as "surreal" or "Surrealism-inspired", Andre Breton's writings will form the foundation for discussion of Miller's work within the concept of "convulsive beauty" and the objet trouve, and other sources on Surrealism, such as the work of Dawn Ades, Roger Cardinal and Robert Short, will be applied. Squiers' collection of essayson photography The Critical Image (1990) and Hal Foster's Compulsive Beauty (2000) will also be cited as important sources when analysing the composition and form of Miller's work within the context of Surrealist art and in the use of semiotics and photographic theory, and Ian Walker's City Gorged With Dreams: Surrealism and Documentary Photography in Interwar Paris (2002) and So Exotic, So Homemade: Surrealism, Englishness and Documentary Photography (2007) are essential sources when considering Miller's

15

photographs as surreal documentary through an analysis of the images' social, cultural and historical context. Angus Calder's The Myth of the Blitz (1991) will be referenced as a cultural-historical source in relation to Miller's photographs of the London Blitz, and Miller's Grim Glory photographs will be compared with Cecil Beaton's images of destruction published in History Under Fire (1941).

In order to explore Miller's photographs from a feminist and gender perspective, sources including Judy Wajcman's Feminism Confronts Technology (1991) and TechnoFeminism (2004), Judith Butler's Gender Trouble (1999) and Undoing Gender (2004), and Jean Gallagher's The World Wars Through the Female Gaze (1998) provide opportunities for further discussion when exploring the argument that technology and war can be interpreted as gender-specific and result in elements of femininity being discarded for, or "de-layered" by, masculinity or a masculine facade. Carol Squiers' idea of the "layering" and "de-layering" process, in particular, will be analysed and developed in Chapter One. Many of Miller's photographs inevitably juxtapose masculinity and femininity, and her images will be discussed in regard to whether women who were involved either directly in the war or indirectly at home were forced to become, to an extent, "masculinised" or "degendered" for their cause.

Finally, in Chapter Three, Jay Winter's Sites of Memory, Sites of Mourning (1995) and Barbie Zelizer's Remembering to Forget: Holocaust Memory Through the Camera's Eye (1998) will be the key sources of reference when discussing the historical-political context of Miller's Second World War photographs and when considering the continuing value of her war photographs and their historical and cultural significance as examples of visual memory and "modern memorials".

It is important to note that due to Miller's abandonment of her work after the war and the consequentlack of detailed information available to researchers,some of

16

her images have been posthumously titled for the purpose of books, articles and exhibitions produced after her death, in many cases by Antony Penrose. In some instances, titles have been given to photographs from captions either with or without Miller's approval. For example, it was common practice for Vogue to provide the captions and accompanying text for Miller's photographs used in photo-spreads such as "Liberation of Paris", published in October 1944. However, for many of her wartime photo-essays, such as "Unarmed Warriors" and "Hitleriana", Miller appears to have contributed both the text and captions for her images. In regard to her photographs published in Ernestine Carter's pictorial booklet Grim Glory: Pictures of Britain Under Fire (1941), it is likely that Miller collaborated with editor Carter over the text and captions used alongside Miller's photographs, an opinion that is supported by Haworth-Booth. 25 Ian Walker agrees that this was the case and adds, "Like the book's inception, the titling was the result of a process of intense collaboration and titles like Remington Silent and The Bridge of Sighs are now integral to the pictures they accompany".26In Wrens in Camera (1945), however, the publisher officially acknowledges "Miss K. M. Palmer, who wrote the text accompanying the photographs".27 For this thesis, Miller's original titles are used whenever possible. However, when an original title is not available, or where a photograph has been published without a title (such as in Grim Glory), the image will be described as "Untitled" followed by the title given by the author of the text in square brackets.

Due to the limited biographical and critical sources available on Miller, I will draw upon the sources outlined above to analyse Miller's war photographs in relation

25Haworth-Booth, The Art of Lee Miller, 155.

26Ian Walker, So Exotic, So Homemade: Surrealism, Englishness and Documentary Photography (Manchester and New York: University of Manchester Press, 2007), 155.

27Lee Miller, Wrens in Camera (London: Hollis and Carter, 1945), ii.

17

to a number of key concepts, as explained in detail below, the main concept being the analysis of Miller war photographs as "surreal documentary".

Key Concepts

i) Surreal Documentary

The term "surreal documentary", as used in the title of this thesis, is a complex one. Initially intended to apply to literature and poetry, Patrick Waldberg writes, "... Surrealism at its inception was intended to be a way of thinking, a way of feeling and a way of life". 28Therefore, according to Waldberg, Surrealism was not a formal movement, as such, but more of "a spiritual orientation". 29Waldberg adds:

the term `Surrealism' can be interpreted in quite different ways, depending on whether it is taken in the orthodox sense which was championed by Breton and his circle [as outlined in his manifestoes], or in the extremely diluted sense in which it is currently used by some critics and by the public. In the latter case, it can be replaced without harm bbysuch expressions as `fantastic', `bizarre' `unusual' or even 'mad'. 3

In this respect, the terms "surreal" and "Surrealism-inspired" are used throughout this thesis both in relation to Miller's often surprising or bizarre use of composition, form and content (including the distinctive use of chiaroscuro lighting, or the play of light and shadows), and in her understanding of Bretonian Surrealism, for example, in the utilisation of Surrealist theories (convulsive beauty and the marvellous) and methods (including fragmentation, juxtaposition, polarisation, chance), as discussed below.

The use of the term "documentary" is in itself challenging and difficult to apply due to its generic nature. Steve Edwards notes that "Documentary is an incredibly elastic category-perhaps even more so than 'document' -which is frequently used to describe war photography, photojournalism, forms of social 28Patrick Waldberg, Surrealism (Cologne: Thames and Hudson, 1997), 7. 29Waldberg, 12. 30Waldberg, 12.

18

investigation, and more open-ended projects of observation"31; and Ian Walker writes, "I use the term `documentary' in ways that have become more common in recent years, as a genre that is broader and more ambiguous that has often been acknowledged in the past". 32 Tanya Barson agrees that "Documentary is far from straightforward or neutral and its influence on visual culture has been complex and multifaceted". 33 Likewise, Abigail Solomon-Godeau writes that "To speak of documentary photography either as a discrete form of photographic practice or, alternatively, as an identifiable corpus of work is to run headlong into a morass of contradiction, confusion, and ambiguity". 34Therefore, for the purpose of this thesis the term "documentary" will be used in relation to the process of creating the record -photograph, for example, in the actual producing and presenting of the final product, whereas the terms "document" or "documentation" will be used in reference to the product (for example, the historical record, such as a war photograph or an official wartime publication). 35

Solomon-Godeau believes that the "retrospective construction of the documentary mode" traditionally begins with the Danish-born reformist Jacob Riis in the 1880s and particularly demonstrated in his work How the Other Half Lives (1890), a documentation of immigrants and social life in New York City. 36Barson, however, claims that it was the British director, producer and writer John Grierson who first established the use of the term "documentary" as a film movement in the 1930s and, subsequently, he was the first to provide a definition and theory of documentary. Barson writes, "Through this movement Britain played a central role in

31Edwards, 26.

32Walker,So Exotic, SoHomemade,8.

33Batson,Making History, 25.

34Solomon-Godeau, Photography at the Dock, 169.

35 Ian Walker describes the "photo document" as the "cousin" of documentary photography, thus indicating a different yet close relationship between the two terms. Walker, So Exotic, So Homemade, 5.

36Abigail Solomon-Godeau, Photography at the Dock: Essays on Photographic History, Institutions and Practices (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 1994), 173.

19

the development of documentary; from the beginning artists were involved and made crucial contributions. In turn, artists have been influenced by documentary practitioners. The traditional opposition between art and documentary can therefore be considered a false dichotomy". 37 American photographer Dorothea Lange has provided a definition of the term "documentary" in relation to documentary photography specifically. She writes:

Documentary photography records the social scene of our time. It mirrors the present and documents for the future. Its focus is man and his relation to mankind. It records his customs at work, at war, at play, or his round of activities through twenty-four hours of the day, the cycle of the seasons, or the span of a life... Documentary photography stands on its own merits and has validity by itself. A single photographic print may be `news,' a `portrait, ' `art, ' or 'documentary'-any of these, all of them, or none. 38

Lange was essentially a "documentary photographer" in the sense that her work aimed to produce what Walker Evans referred to as "records" or "straight documentation"39-historical records of the Depression-era without foregrounding aesthetic composition or content. However, as Lange acknowledges, a photograph does not have to be strictly placed within just one genre and may be a combination of art and documentary, as can be seen throughout the work of photographers with artistic backgrounds such as Evans, whose aim was to photograph "the moral and aesthetic texture of the Depression",40 and Henri Cartier-Bresson who commented

37Tanya Barson,"Time Presentand Time Past" in Making History: Art and Documentaryin Britain from 1929to Now (Liverpool: Tate,2006), 9.

38 Dorothea Lange quoted in Karin Becker Ohm, Dorothea Lange and the Documentary Tradition (Baton Rouge and London: Louisiana State University Press, 1980), 37. Ohm also notes that "documentary photography" as a specific genre was first given significant recognition within the fine arts when the New York Museum of Modem Arts included examples of documentary photographs by Lange and others in a major 1940 exhibition. Ohm, 115.

39 Belinda Rathbone, Walker Evans: A Biography (Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1995), 57-58.

40 Walker Evans quoted in Rathbone, 2. Rathbone further notes that Evans' book American Photographs (1938) "would go down in history as his single achievement, establishing him as an artist and the very notion of documentary photography as an art". Rathbone, 167.

20

that "photography is not documentary, but intuition, a poetic experience".41 As Edwards writes:

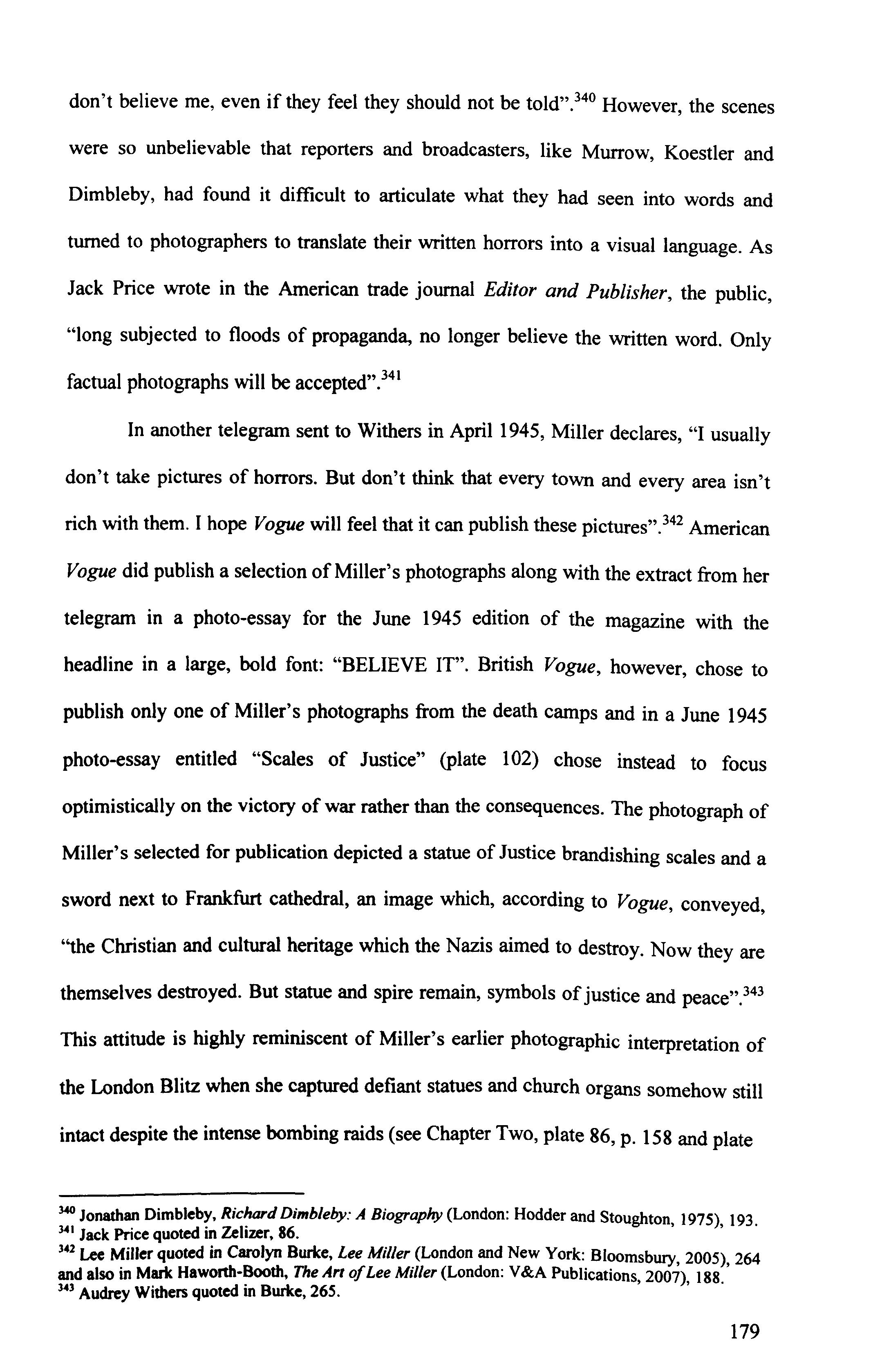

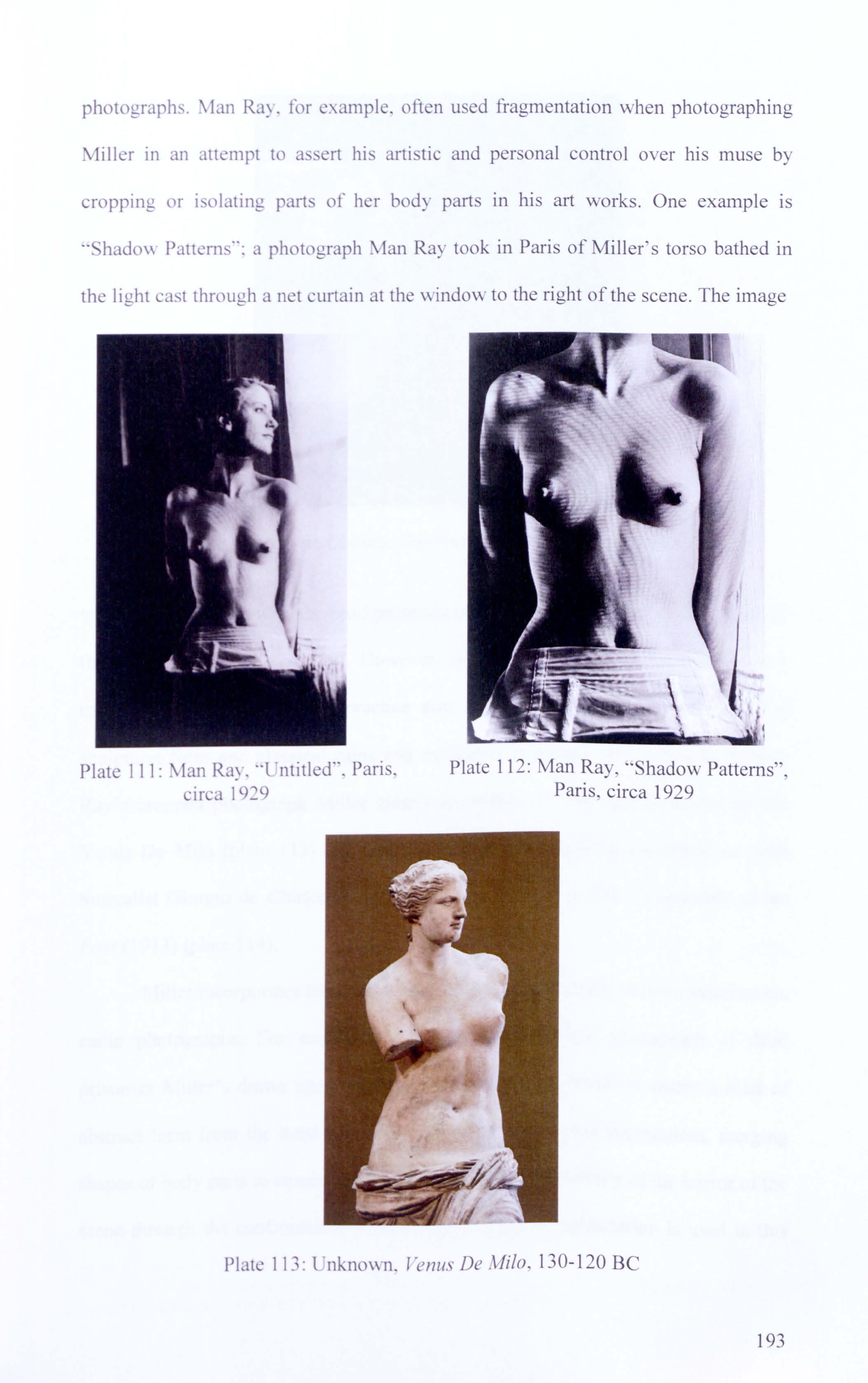

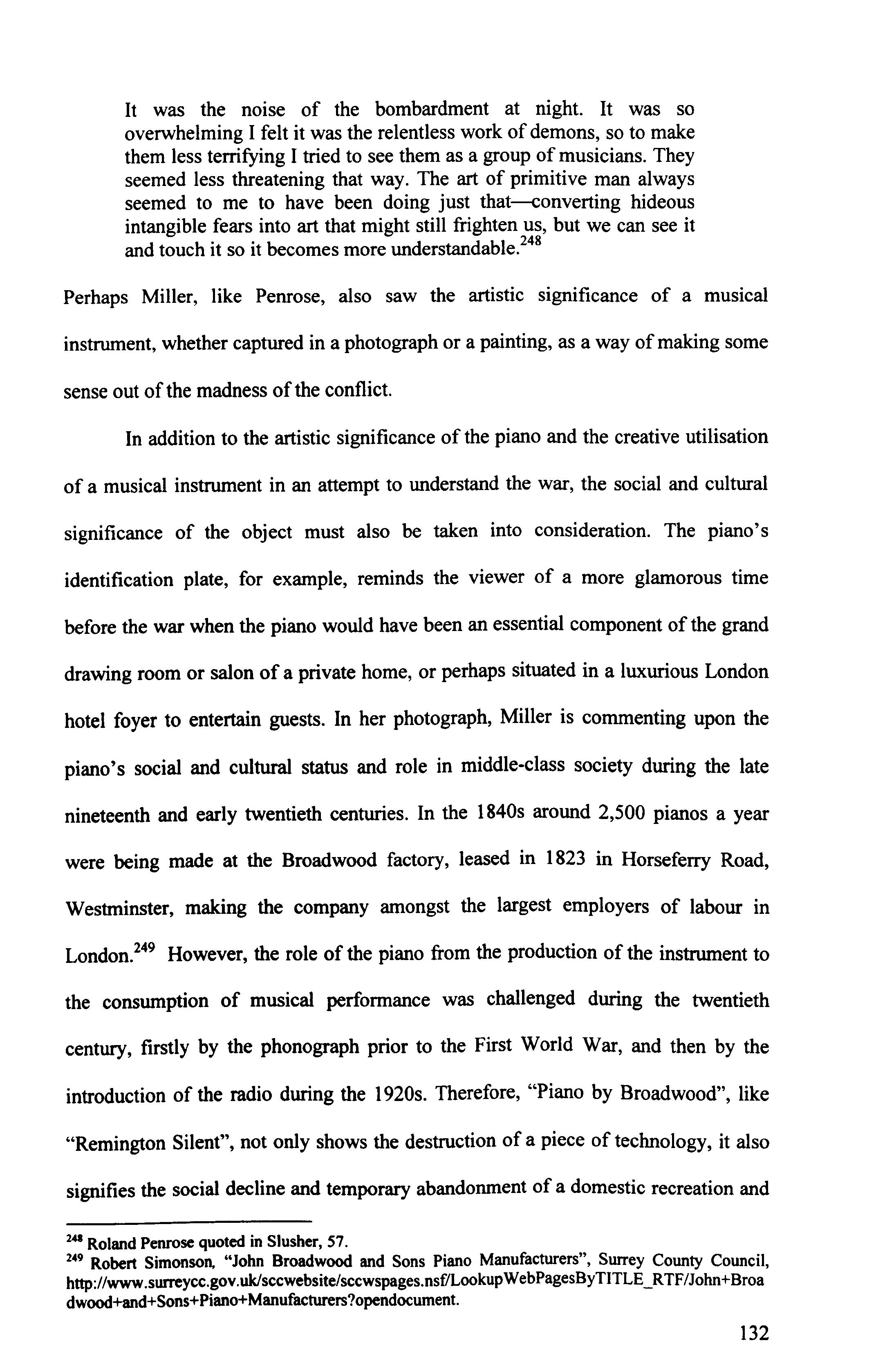

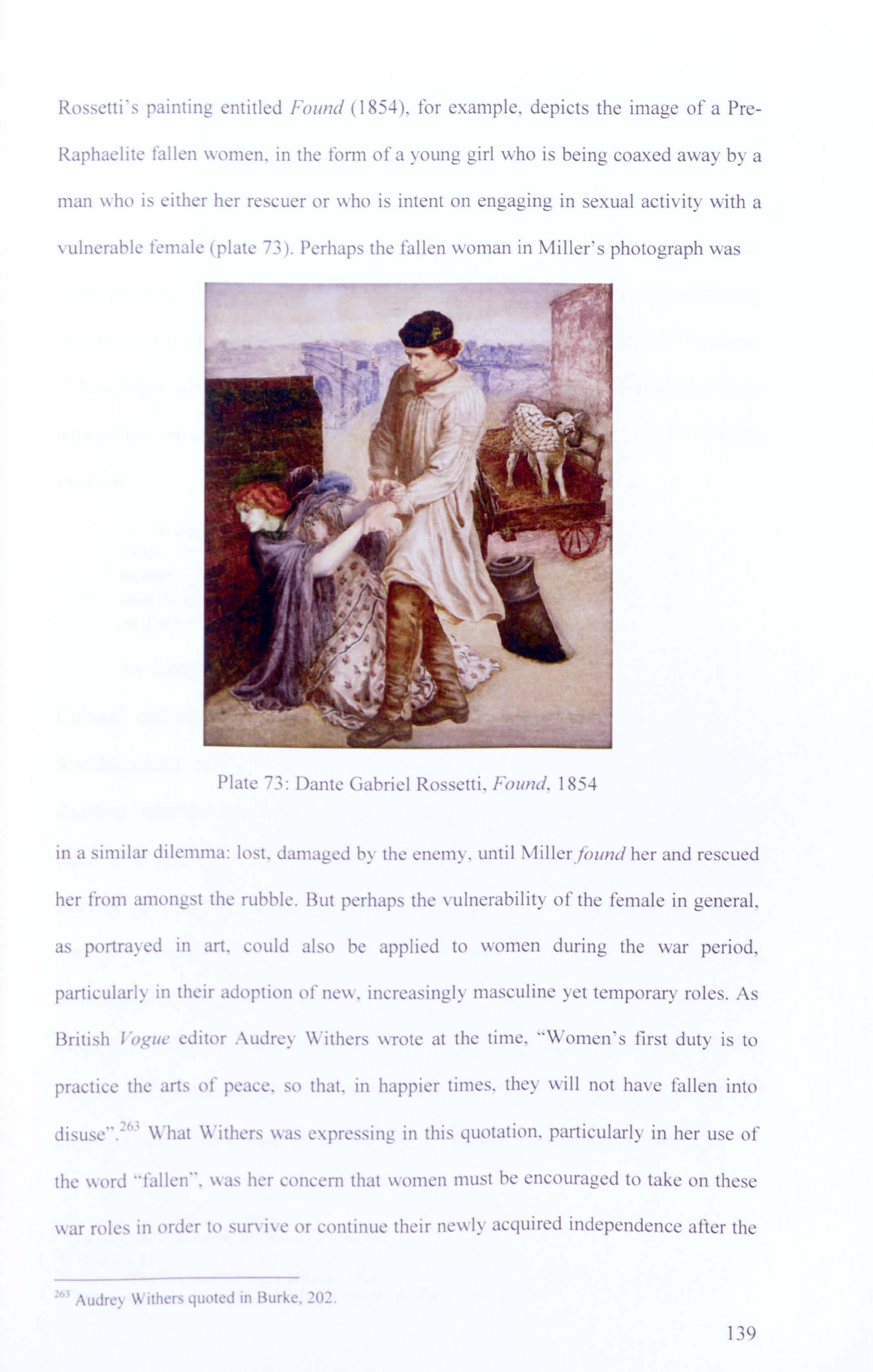

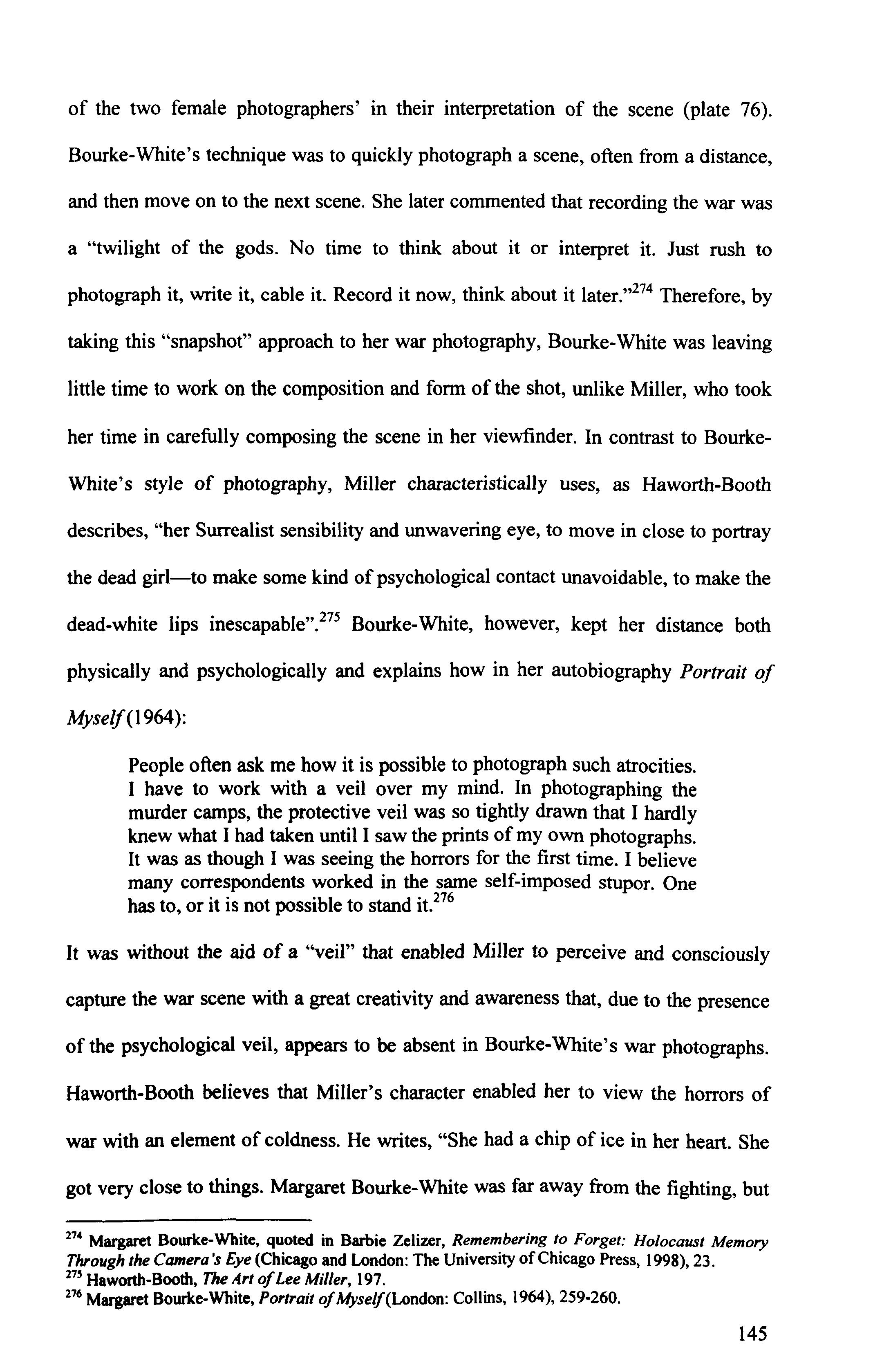

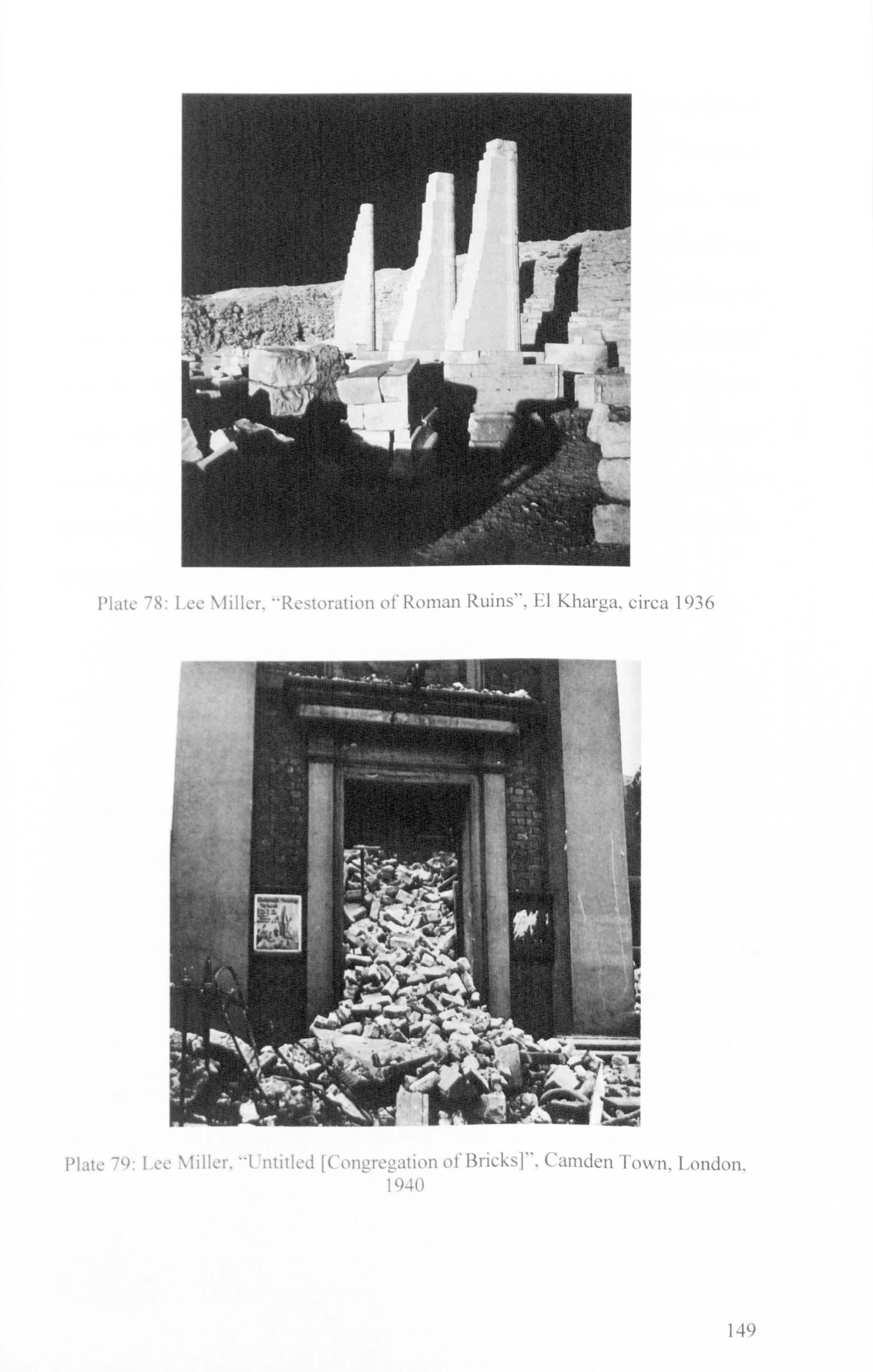

Many key documentary photographers-including Walker Evans, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Humphrey Spender, Brassai, and Andre Kertesz-thought of their work as a new kind of poetry. In this manner, much documentary photography combined a campaigning vision with an aesthetic of the everyday. In part, at least, this conception stems from the emergence of documentary photography alongside Surrealism. Documentary photographers were interested in finding the extraordinary in ordinary life. Rather than high-flown subjects, the vision focused on the way shadows fall on empty coffee cups, life on the streetsof the modern city, or the oddities associated with popular leisure.42