Marc Chagall’s Apocalypse en Lilas, Capriccio (1945)

A Visual Language for the Holocaust

A Dissertation submitted as part of the requirements for the Degree of BA with Honours in History of Art

By Milly AllweisMay 2023

Abstract

This dissertation will explore Marc Chagall’s Apocalypse en Lilas, Capriccio and show how the artist developed a visual language for the Holocaust. Chagall created the work in 1945 when he was in New York, havingfledfrom Europetoavoid persecutionbytheNazisas hewas Jewish.At thistime, Chagall was also aware of the wide-scale extermination of Jews in concentration camps which had been publicised in mass media. In Apocalypse, Chagall responds to the Holocaust by presenting a complex composition of Christological imagery, Jewish symbols, and political caricature. His depiction of the Crucifixionisparticularlyunusualandanalysingitshowshowtheartistdistortstraditionalartisticforms to represent the chaos caused by the Holocaust. This is significant as Chagall depicted the Crucifixion in many works throughout the 1930s and 1940s. One may compare the Crucifixion works Chagall kept private, such as Apocalypse, with those which were put on public display to consider how Chagall intended for his Crucifixion works to be perceived by the viewer. It is key to note that Chagall was not the only artist to use Christological imagery to represent the terrors of World War II. Comparing Apocalypse with works by other émigré artists therefore gives insight into how Chagall was not alone in developing a visual language for the Holocaust. Furthermore, as the Jewish symbols which Chagall uses in Apocalypse also appear in other of his works, the presence of Chagall’s visual language for the Holocaust across the artist’s wartime practice may be considered.

Introduction

Marc Chagall was born to a Hassidic Jewish family in 1887 in Vitebsk, Belarus. In 1910, Chagall went to France to work as an artist, and he gained French citizenship in 1937 However, in 1941, following the outbreak of World War II, the artist and his family were forced to flee from Europe to New York to avoid persecution by the Nazis.1 In 1943, Chagall discovered that German soldiers had destroyed his birthplace, Vitebsk, and learned about the extermination of Jews at Nazi concentration camps.2 Also, in 1944, Chagall’s wife, Bella Rosenfeld, passed away from a virus. Though the virus could have been cured by penicillin, Rosenfeld was unable to obtain antibiotics as the limited supplies available in America were retained for military use.3 Having directly experienced the hardships of World War II, in 1945, Chagall created Apocalypse en Lilas, Capriccio (fig. 1). In the work, one can see imagery which represents the contemporary political moment, for example, the depiction of a Nazi officer in the foreground. However, much of the imagery in Apocalypse, is abstract and ambiguous Most of the composition is taken up by a representation of the Crucifixion in which Christ is presented to be wearing a prayer shawl and phylacteries. One may question why Chagall uses biblical imagery to represent the extreme suffering of Jews in this moment. Throughout the 1930s and 1940s, Chagall created many works which used the Crucifixion as a subject matter, such as White Crucifixion (fig. 2), The Martyr (fig. 3), and Yellow Crucifixion (fig. 4). Apocalypse greatly differs from these works as it contains explicit political symbols, for example, the distorted swastika on the Nazi officer’s armband, and as Christ is depicted to be naked. One may therefore question why Apocalypse appears to be so different from other of Chagall’s Crucifixion paintings Many émigré artists, like Chagall, fled to New York during the war and created works in response to the contemporary political violence. Their influence on Chagall’s wartime outputs can therefore be considered. It is key to note that during the Holocaust, Chagall also made many works that did not depict the Crucifixion but did include other imagery that appears in Apocalypse. For example, in Apocalypse, the figure of Christ overlays a sketch

1 Susan Compton, ‘Chagall, Marc’, Oxford Art Online (2003) <https://doi.org/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.T015694> [accessed 30 April 2023]

2 Susan Tumarkin-Goodman, ‘The Fractured Years of Marc Chagall: The 1930s and 1940s’, in Chagall: Love, War and Exile, ed. by Susan Tumarkin-Goodman (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013), pp. 14-88 (pp. 51-56)

3 Monica Bohm-Duchen, Chagall (London: Phaidon, 1998), p. 262

of a rooster (fig. 5) which is a symbol that Chagall also used in works such as The Flying Sleigh (fig. 6) and Day and Night (fig. 7). One may therefore explore the significance of such symbols across Chagall’s wartime practice.

It is key to consider whether literature on Chagall has explored these issues and, if not, why this may be. Most scholarship on Chagall comes from biographic and curatorial sources. In Monica Bohm-Duchen’s biography, Chagall, and Franz Meyer’s catalogue raisonne, Marc Chagall: Life and Work, both scholars acknowledge that Chagall’s Crucifixion works from the late 1930s to mid-1940s were responses to the Holocaust. For example, Bohm-Duchen states, ‘White Crucifixion of 1938 represents the first… in a long series of Crucifixion images produced by Chagall in this period of his career. Each of these can be seen… as a direct response to specific historical events [that took place during the Holocaust].’4 Meyer also writes, ‘White Crucifixion is the first of a long series… full of contemporary history’.5 However, Bohm-Duchen and Meyer generally focus on Chagall’s finished paintings, such as White Crucifixion, and do not explore how they differ from sketches like Apocalypse Additionally, Bohm-Duchen and Meyer do not consider how other works by Chagall from this period that do not depict the Crucifixion may similarly be representative of the Holocaust Meyer recognises that Chagall uses darker colours and more obscure imagery in works he created following fleeing to America, stating, ‘the bright airy world of [Chagall’s pre-war works] … was transformed into a region of mysterious, nocturnal magic… [which is] more secretive and ambiguous.’6 However, Meyer does not suggest why Chagall’s practice may have changed. Bohm-Duchen, on the other hand, argues changes in the artist’s practice in this moment can be understood as responses to the death of his wife, Bella Rosenfeld 7 Therefore,neitherMeyer nor Bohm-Duchenconsiderthe political nature of Chagall’s wartime practice.

4 Bohm-Duchen, p. 227

5 Franz Meyer, Marc Chagall: Life and Work (New York: Abrams Books, 1964), p. 416

6 Meyer, p. 451

7 Bohm-Duchen, p. 286

There have been two major exhibitions of Chagall’s works in the United Kingdom in the last 25 years. These were Chagall: Love and the Stage at the Royal Academy of Arts in 1998 and Chagall: Modern Master at Tate Liverpool in 2013 Chagall: Love and the Stage focussed on the period between 1914 and 1922 when Chagall was working between Vitebsk and Moscow. It displayed paintings which depict couples embracing, scenes from everyday life in Vitebsk and canvases which were intended to decorate a Jewish theatre in Moscow. In the catalogue, Susan Compton states these works, ‘formed the core of Chagall’s art for the remainder of his life… the loves they embody and the way he expressed them continued to inspire him.’8 Compton thus implies Chagall’s most important and influential work was created in his birthplace and explores the themes of home, relationships, and leisure. Overall, the exhibition therefore presents Chagall’s work as optimistic and uplifting, ignoring the poignant works he created around the time of the Holocaust. Chagall: Modern Master mainly focussed on how the artist’s style developed when he travelled to Paris and Berlin before World War II. In the catalogue, Simonetta Franquelli draws attention to how Chagall was simultaneously influenced by Jewish folklore and the practices of European avant-gardists, stating, ‘His [Chagall’s] artistic brilliance rested to a great extent on his ability to create a counterpoint between his own rich cultural heritage and the prevailing modernist art disciplines’ 9 Similarly to Chagall: Love and the Stage, the resultant scholarship from Chagall: Modern Master hardly gives any consideration to the significance of Chagall’s works created in response to the Holocaust.

However, more recent exhibitions have focused on the works Chagall created in the 1930s and 1940s, namely, Chagall: Love, War and Exile at Jewish Museum in New York from 2013 to 2014 and Chagall: World in Turmoil at the Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt from 2022 to 2023. In the catalogues for both exhibitions, scholars draw attention to Chagall’s use of the Crucifixion to represent Jewish suffering. For example, in the catalogue for Chagall: Love, War and Exile, Susan Tumarkin-Goodman states, for Chagall, ‘the Crucifixion image was an expedient means of conveying the pain of Jews in a

8 Susan Compton, ‘Introduction’, in Chagall: Love and the Stage, ed. by Susan Compton (London: Merrell Holberton, 1998), p. 9 (p. 9)

9 Simonetta Fraquelli, ‘Logic of the Illogical’, in Chagall: Modern Master, ed. by Simonetta Fraquelli (London: Tate Publishing, 2013), pp. 13-28 (p. 24)

Christian world’.10 Similarly, in the catalogue for Chagall: World in Turmoil, Ilka Voerman states, in Chagall’s works, ‘The depiction of the crucifixion and the Jewish Christ… became the central allegory for the suffering of European Jews’.11 However, in both catalogues, there is no exploration of the differences between Chagall’s various Crucifixion works. For example, in the catalogue for Chagall: World in Turmoil, Leon Joskowitz states, in Chagall’s Crucifixion works, ‘Even though details vary, Jesus is always wearing a tallit, the white prayer shawl with black stripes and tzitzit (ritual fringes) on its edge, which shows him to be a Jew.’12 Though Joskowitz notes that there are differences in how the prayer shawl is represented, he does not explore how this may influence the meaning of paintings. One may suggest that such specificities are key to understanding the complex imagery in Chagall’s wartime works.

This dissertation will consider how Chagall developed a visual language for the Holocaust by analysing Apocalypse and comparing it with other works created around World War II by Chagall and fellow émigré artists. Chapter One will explore the significance of the Crucifixion in Apocalypse In Holocaust Representation: Art within the Limits of History and Ethics, American philosopher Berel Lang conceives that in all forms of art made in response to the Holocaust, creators often distort traditional subjects, styles, and genres. He argues this is because conventional forms of art are, ‘quite inadequate for the images of a subject with the moral dimensions and impersonal will of the Holocaust.’13 The chapter will use Lang’s idea to consider the different ways Chagall adapts the traditional art historical subject of the Crucifixion in Apocalypse to represent the Holocaust. Chapter Two will begin by comparing Apocalypse with Chagall’s more finished Crucifixion paintings, such as White Crucifixion and The Martyr, to show how they have different effects on the viewer It will then explore the similarities between Apocalypse and the preliminary sketches for these works as they all contain overt political imagery. Subsequently, the chapter will question why Chagall seems to self-

10 Tumarkin-Goodman, p. 43

11 Ilka Voerman, ‘Chagall: World in Turmoil’, in Chagall: World in Turmoil, ed. by Ilka Voerman (Munich: Hirmer Verlag, 2022), pp. 26-35 (p. 28)

12 Leon Joskowitz, ‘The Jewish Jesus’, in Chagall: World in Turmoil, ed. by Ilka Voerman (Munich: Hirmer Verlag, 2022), pp. 48-55 (p. 51)

13 Berel Lang, Holocaust Representation: Art within the Limits of History and Ethics (Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press, 2000), p. 10

censor his public works. To consider this, it will look both to Chagall’s biography and Lang’s ideas about the pedagogical function of Holocaust art. Chapter Three will show how Apocalypse shares similarities with works by other émigré artists that fled to New York following the outbreak of World War II. In The Archetypal Nature of Crucifixion, Jennifer Swan argues, in works created by nonChristian artists, the Crucifixion functions, ‘as a visual metaphor to establish or support the nature of an individual's suffering'.14 In response to this, the chapter will explore how Chagall, Jacques Lipchitz and Roberto Matta all bring Christological imagery together with symbols from their own religions and cultures to represent the horrors of war. Subsequently, the chapter will consider how and why scholarship on Lipchitz and Matta greatly differs from that on Chagall. This is because, though scholars often interpret Lipchitz and Matta’s wartime works to be representative of contemporary political turmoil, many of Chagall’s works from this period are often interpreted biographically as responses to his romantic relationships. The chapter will then challenge such scholarship on Chagall by reinterpreting examples of his wartime works as responses to the Holocaust.

Overall, the dissertation will argue that Chagall developed a visual language for the Holocaust, made up of Christological and Jewish symbols. It will show that Chagall adapts this visual language in his private and public works to different effects. The dissertation will also demonstrate how Chagall’s visual language for the Holocaust can be recognised, not only in the artist’s Crucifixion works, but in many of his wartime and postwar paintings. Moreover, it will show that, to gain a better understanding ofChagall’spractice,onemustcompareChagallwithhiscontemporaries. Thesecomparisonswillmake it evident that Chagall was not alone in creating a visual language for the Holocaust as many émigré artists were similarly developing distinctive ways to represent their direct experiences of political turmoil.

14 Jennifer Swan, ‘The Archetypal Nature of Crucifixion’, in Cross Purposes: Shock and Contemplation in Images of the Crucifixion, ed. by Nathaniel Hepburn (London: Mascalls Gallery and Ben Uri Gallery, 2010), pp. 14-17 (p. 15)

Chapter One: The Significance of the Crucifixion in Apocalypse en Lilas, Capriccio

The focal point of Apocalypse en Lilas, Capriccio is a representation of the Crucifixion. One may question why Chagall chose to depict a subject matter so entrenched in Christian ideology to represent the plight of Jews during the Holocaust. Lang states, ‘traditional forms… are quite inadequate for the images of a subject with the moral dimensions and impersonal will of the Holocaust. Thus the constant turning in Holocaust images to difference’. 15 It can be argued that this is shown in Apocalypse as Chagall presents the traditional art historical subject of the Crucifixion in an unusual context by surrounding it with imagery relating to contemporary politics and Jewish culture. One may suggest that this is why Chagall subtitles the work ‘capriccio’ as the term refers to a composition that combines depictions of real and imagined features.16 This chapter will explore how Chagall merges the figure of Christ withpolitical imageryandJewish symbolstoshowdifferent waysinwhichJewswerepersecuted during the Holocaust. It will firstlyconsider how Chagall emphasisesthe suffering of Christ bybringing the Crucifixion into a contemporary context Secondly, the chapter will explore how Chagall draws attention to Christ’s Jewishness through the prayer shawl and the symbol of the rooster. It will then consider how the idea of Christ’s Resurrection is implied to emphasise the repeated persecution of Jewishpeople The chapterwill ultimatelyconcludethat these varyinginterpretations of theCrucifixion in Apocalypse are all significant and that the Crucifixion is a key image in Chagall’s visual language for the Holocaust.

Much of the existing scholarship on Chagall’s Crucifixion works argues that the artist presents Christ as human as opposed to divine, thus making the Crucifixion an apt symbol to represent the Holocaust as it draws attention to the suffering caused by religious persecution. Meyer, for example, writes that in White Crucifixion (fig. 2), ‘Chagall's Christ figure lacks the Christian concept of salvation... This Christ is a man who suffers pain in a thousand forms.’17 Bohm-Duchen also states that

15 Lang, p. 10

16 John Wilton-Ely, ‘Capriccio’, Oxford Art Online (2003) <https://doi.org/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.T013901> [accessed 27 February 2023]

17 Meyer, p. 416

Chagall presents, ‘Jesus as a Jewish martyr, human rather than divine’ 18 It can be argued this is also the case for Apocalypse when one explores the imagery which surrounds the Crucifixion. In the work, Chagall depicts a Nazi at Christ’s feet. This is evident as the figure wears an armband with a symbol closely resembling a swastika, and as his moustache looks like Adolf Hitler’s. His hunched posture makes him look as though he has just climbed down the ladder having crucified Christ. By presenting a Nazi to be responsible for the Crucifixion, Chagall emphasises the prolonged suffering the Nazis caused to Holocaust victims. This is because the extremely slow and painful process of crucifixion draws the viewer’s attention to how the Holocaust was a drawn-out programme which developed from the passing of antisemitic legislation, such as the Nuremberg Laws, to the ghettoization of Jewish people, to their ultimate extermination in concentration camps.19 Bringing the Crucifixion into this contemporary context shows how, for Holocaust art, distorting aesthetic conventions is, as Lang states, a ‘harsh way in which the… distinction between content and form is shown… to be a function of their relatedness’ 20 Chagall further brings the Crucifixion into the contemporary moment through the imagery on the right-hand side of Apocalypse Just below the clock, one can see a woman who looks as though she is falling and reaching towards stone tablets. They resemble those which were thought to have been inscribed with the Ten Commandments. To her left, Chagall depicts a man clutching onto a Torah scroll. By depicting the couple’s attempts to cling onto these items, Chagall represents the desperation with which Holocaust victims tried to retain their religion and culture in a moment when the Nazis were trying to destroy it, for example, during events such as Kristallnacht 21 Beneath the couple, one can see symbols of a mother nursing a child, houses which resemble those found in Jewish, eastern-European villages, known as shtetls (fig. 8), people fleeing in boats and a hanged man. Chagall juxtaposes symbols with connotations of family and home with those relating to refugeeism and mortality, thus drawing attention to the threat and danger posed to Jewish people who attempted to escape German-occupied countries. These images would have been of personal resonance to Chagall

18 Bohm-Duchen, p. 232

19 ‘Timeline of Events’, Holocaust Encyclopedia (2019) <https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/timeline/holocaust> [accessed 22 April 2023]

20 Lang, p. 47

21 ‘Kristallnacht’, Holocaust Encyclopedia (2019) <https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/kristallnacht> [accessed 2 April 2023]

who, following the enactment of anti-Jewish laws in France, fled to Madrid with his family, and then to Lisbon from where they travelled to New York.22 By surrounding the figure of Christ with images and symbols relating to the plight of Jewish refugees, Chagall equates their hardship to the pain caused by the Crucifixion.

Existing scholarship which argues that Chagall represents Christ’s humanity rather than his divinity to emphasise his suffering also suggests the artist may have been influenced by documentary photographs from concentration camps. Bohm-Duchen has cited figure 9, a photograph taken during the liberation of Bergen-Belsen, to demonstrate why postwar artists associated the bodies of Holocaust victims with the figure of Christ.23 Though we cannot be certain Chagall saw this specific photograph, it is evident he knew of similar images and reports which revealed the mass extermination of Jews at concentration camps By the end of 1942, New York newspapers were reporting on the systematic murder of Jews in Europe and by 1944, it was known that 1.7 million had been killed at Auschwitz Tumarkin-Goodman writes, ‘Chagall was wracked with guilt at sitting out the war in physical comfort in America. In answer to a questionnaire in 1943… he responded, ‘To my shame, I have not helped them [the Jews] in the critical moment’ ’24 Given Chagall’s awareness of the horrors of concentration camps, it is likely that such documentation influenced how Chagall painted the Crucifixion in Apocalypse. The figure of Christ has outstretched arms and his gaping mouth makes him look as though he is screaming or yelling It can be argued that Chagall representing Christ as such shows the artist’s attempt to draw attention to the extreme suffering caused to concentration camp victims.

More recent scholarship on Chagall’s Crucifixion works has shown how the artist draws attention to Christ’s Jewishness to emphasise the Crucifixion’s relevance for visual representations of the Holocaust. For example, Tumarkin-Goodman states, ‘For most Jews, Jesus was perceived as the

22 Bohm-Duchen, pp. 237-238

23 Bohm-Duchen, p. 234

24 Tumarkin-Goodman, pp. 51-52

emblem of Christian antisemitism; for Christians, the image was inseparable from its sacred status as an icon of Christian faith. Chagall thus deliberately chose the most contested visual expression possible to articulate a specifically Jewish crisis.’25 Jews perceived Jesus to be the ‘emblem of Christian antisemitism’ because, as Tamar Garb writes, ‘in Western Christian culture... the Jew has had to be punished not only for… deicide but also for ‘his’ continued refusal to acknowledge the truth of Christianity.’26 Though Tumarkin-Goodman articulates how the figure of Christ draws attention to this archaic hostility, she does not explore how Chagall may have been responding to the Church’s antisemitism at the time he was creating his Crucifixion works. Eric Weitz argues, ‘Perhaps more than anything else, the rhetoric deployed by the Christian establishment made the Nazis… acceptable in polite society.’27 Such rhetoric included both the Lutheran and Catholic Churches’ use of the word ‘volkstum’ which, ‘by the 1920s carried profound racial connotations… [as it] signified that defined characteristics lay ‘in the blood’, that German Volkstum was something innate and transmitted through the generations.’28 Weitz also states that at the 1924 Lutheran conference, the major speaker, German theologian Paul Althaus, ‘claimed the church had to take a clear stand against ‘the Jewish threat to our national character’’ 29 It is evident that Chagall was aware of the Church’s antisemitism as he gave a speech at the Conference of the Committee of Jewish Writers, Artists and Scientists in February 1944, in which he stated, ‘after two thousand years of “Christianity” in the world… with few exceptions, their hearts are silent... I see the artists in Christian nations sit still - who has heard them speak up? They are not worried about themselves, and our Jewish life doesn't concern them.’30 Therefore, as Chagall combines Christian iconography with the figure of a Nazi in Apocalypse, the artist does not just explore the Nazis’ persecution of Jews, but also the Church’s complicity in that persecution This may be considered when analysing how Chagall emphasises Christ’s Jewishness in Apocalypse

25 Tumarkin-Goodman, p. 43

26 Tamar Garb, ‘Introduction: Modernity, Identity, Textuality’, in The Jew in the Text: Modernity and the Construction of Identity, ed. by Tamar Garb and Linda Nochlin (London: Thames and Hudson, 1995), pp. 20-30 (p. 20)

27 Eric Weitz, Weimar Germany: Promise and Tragedy (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007), p. 339

28 Weitz, p. 340

29 Weitz, p. 340

30 Marc Chagall, ‘Unity – Symbol of Our Salvation: Speech at the Conference of the Committee of Jewish Writers, Artists and Scientists, February 1944’, in Marc Chagall on Art and Culture, ed. by Benjamin Harshav (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2003), pp. 87-91 (pp. 89-90)

Ziva Amishai-Maisels states, Jewish and anti-Fascist artists ‘used [Christological symbolism] to attack the Church either for sympathizing with Fascism or for not doing anything to avert the Holocaust’ . 31 One can argue that, in Apocalypse, Chagall does this by drawing attention to Christ’s Jewishness through elements such as the prayer shawl. In Chagall’s other Crucifixion works, such as White Crucifixion (fig. 2), the artist depicts Christ to be wearing a prayer shawl around his waist, like a loincloth, however,in Apocalypse, he shows Christ wearing one over his head, so it falls down his back.

In the catalogue for the BenUri Gallery’s 2010 exhibition, Cross Purposes, JackieWullschläger writes, in Apocalypse, ‘Christ’s hips curve sensually like a woman’s, and recall Chagall’s depictions of his wife Bella [Rosenfeld], who had died six months earlier. His recurring images of Bella as a bride are also echoed in the full-length white prayer shawl coursing down Christ’s back like a bridal gown.’32 It can be argued that this biographical interpretation of the prayer shawl’s significance is unconvincing as Apocalypse’s biblical subject matter and explicit political connotations do not overtly, if at all, relate to the theme of matrimony Also, as there are no known instances of Chagall painting Rosenfeld nude, the suggestion that Christ’s curved hips bear a resemblance to Rosenfeld’s body does not seem plausible It may instead be suggested that, as Jewish prayer shawls are supposed to be worn over the head, so they drape down the back, Chagall painting Christ to be wearing one as such emphasises his Jewishness 33 This would have been particularly contentious at a time when the Church was persecuting Jews by means of othering them By presenting Christ as inherently Jewish at a time when the Church wanted to distance themselves from Jews, Chagall thus, as Lang states, ‘challenge[d]… [aesthetic] conventions to find a means adequate for representing the specific features of [the Holocaust]’ 34

Another way in which Chagall draws attention to Christ’s Jewishness is through the symbol of the rooster. Amishai-Maisels identified that underneath thefigure of Christ, Chagall sketched a rooster (fig. 5). One may argue this alludes to kapparot, the Jewish ritual carried out on Yom Kippur, the Day of

31 Ziva Amishai-Maisels, ‘Christological Symbolism of the Holocaust’, Holocaust and Genocide Studies, 3 (1988), 457-481 (p. 478)

32 Jackie Wullschläger, ‘Marc Chagall: Apocalypse en Lilas Capriccio’, in Cross Purposes: Shock and Contemplation in Images of the Crucifixion, ed. by Nathaniel Hepburn (London: Mascalls Gallery and Ben Uri Gallery, 2010), pp 42-43 (p. 43)

33 ‘Tallit’, Encyclopaedia Judaica, 19 (2007), 465-466 <link.gale.com/apps/doc/CX2587519534/GVRL?u=bham_uk&sid=bookmark-GVRL&xid=701fb9fb> [accessed 12 March 2023]

34 Lang, p. xi

Atonement, in which the sins of a person are symbolically passed over to a rooster which is then sacrificed 35 This custom can be compared with the narrative of Christ being martyred for humankind’s sins. By bringing together Jewish and Christian images of mortality and sacrifice, Chagall further emphasisesthedevastatingconsequencesofreligiouspersecutioncausedbytheNazisandChurchalike.

A final aspect of the Crucifixion which scholars have not previously explored in relation to Chagall’s work is the Resurrection. One may argue that the idea of the Resurrection is significant in Apocalypse when considering its composition. As Chagall has arranged the figurative elements of the work in a circular format, Apocalypse can be read in a clockwise direction. One may start reading it from the right-hand side with the couple trying to keep hold of the stone tablets and Torah, representing howtheNazisforcedJewishpeopleawayfromtheirreligionandculture. Theimagesbeneaththecouple represent how, in response to experiencing such persecution, Jews in German-occupied countries tried to seek refuge. In continuing to read the work in a clockwise direction, one then sees the image of a Nazi and, in the bottom left-hand corner, Chagall depicts people who were not able to seek refuge but were captured. One figure at the base of the ladder is being crucified, some wear armbands with a star of David, classifying them as Jewish prisoners, and some are naked, emphasising their vulnerability. They are depicted behind a fence which is evocative of those which surrounded the perimeters of concentration camps. The figure of Christ marks the end of this narrative and represents the ultimate elimination of Holocaust victims However, if the ideaof the Resurrection is considered, one may argue that the figure of Christ not only represents the end of this narrative, but also its rebeginning, making this cycle of oppression seem ceaseless This idea of endlessness is further emphasised by the grandfather clock in the top, right-hand corner of Apocalypse. Chagall makes the clock appear uncanny to the viewer by showing it to be upside down, distorting its shape and depicting two of its hands to be floating to the right of the clockface. As the grandfather clock is there presented to be unequipped to function, one may argue it draws attention to the idea of timelessness in Apocalypse.

35 ‘Kapparot’, Encyclopaedia Judaica, 11 (2007), 781-782 <link.gale.com/apps/doc/CX2587510735/GVRL?u=bham_uk&sid=bookmark-GVRL&xid=e7c634f6> [accessed 2 March 2023]

Itiskeytoconsiderhowthetitleofthework,whichdescribesitasrepresentingan‘apocalypse’, complicates this interpretation. The word, ‘apocalypse’, refers to the events described in the New Testament of Christ’s Second Coming and the subsequent destruction of the world. It can also be used more generally to describe, ‘a disaster resulting in drastic, irreversible damage to human society or the environment, especially on a global scale.’36 One may understand why Chagall felt it was appropriate to use the word ‘apocalypse’ in the work’s title as it draws attention to the finality of the events of the Holocaust.Ifthetitleofthework thussuggeststhat Chagall isrepresentinganultimateendtotheJewish people, it seems contradictory to imply that the artist is presenting antisemitism to be unending through the imagery of the Resurrection (for one would assume that the complete elimination of the Jewish people would mark the end of antisemitism). However, it can be argued that this paradox is key to understanding the work as it draws attention to the repeated attempts made to eliminate the Jewish people throughout history. Such events have happened since Antiquity with, for example, the Romans killing over half a million Jewish civilians in the Third Jewish Revolt, the Massacre of 1391 in Spain in which approximately 50,000 Jews were murdered, pogroms in nineteenth-century Eastern Europe and, ultimately, the Holocaust 37 One may therefore argue that by alluding to the Resurrection in this apocalyptic work, Chagall draws attention to the fact that Jews have repeatedly faced elimination.

To conclude, one may agree with Lang’s argument that artists often, ‘challenge… [aesthetic] conventions …to find ameans adequate for representing the specific features of[the Holocaust]’, when considering how Chagall represents the Crucifixion in Apocalypse 38 The inclusion of the Nazi officer andrefugeeimagerybringstheCrucifixionintoacontemporarycontext and supports previousscholars’ arguments that, in his Crucifixion works, Chagall presents Christ as human, as opposed to divine, to highlight his suffering and thus represent the anguish ofHolocaust victims. This interpretation is further supported by the suggestion that Chagall’s depiction of Christ’s body alludes to documentary images

36 ‘apocalypse, n.’, OED Online (2022) <www.oed.com/view/Entry/9229> [accessed 3 March 2023]

37 Steven Beller, Antisemitism: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), pp. 11-17

38 Lang, p. xi

of concentration camp victims In Apocalypse, Chagall also emphasises Christ’s Jewishness by presenting him to be wearing a Jewish prayer shawl in the correct way and to be overlapping a rooster, which symbolises sacrifice. This may be perceived to be a response, not just to the Nazis’, but also to the Church’s antisemitism during World War II as Chagall resists the othering of Jews from Western Christian society. Finally, it can be argued that the idea of the Resurrection is displayed through Apocalypse’s circular composition, which allows it to show an unending narrative cycle, and through the distorted clock which emphasizes this idea of timelessness. In asserting that the work represents an ‘apocalypse’ in the title, Chagall draws attention to how Jewish people have repeatedly had to face the end of their existence as they have consistently been targets of massacres, pogroms, and genocide.

Overall,it isevident that theCrucifixion is a significant image inthe visual language Chagalldeveloped in response to the Holocaust. This is because, by reframing an iconic art historical subject, Chagall demonstrates the ineptitude of traditional forms for the representation of such a horrific moment in history.

Chapter Two: Apocalypse en Lilas, Capriccio and the Crucifixion in Chagall’s Oeuvre

Chagall repeatedly depicted the Crucifixion in paintings throughout his artistic career. From the late 1930s to the mid-1940s, Chagall produced a particularly great amount of Crucifixion works in response to the Holocaust.39 In Chagall’s lifetime, some of these works, such as Apocalypse, were kept in the artist’s own, private collection. Apocalypse was eventually sold by the estate of the artist two years after Chagall passed away.40 However, other of Chagall’s Crucifixion works were sold and publicly displayed in the artist’s lifetime, for example White Crucifixion (fig. 2) and The Martyr (fig. 3).41 It is key to note that, although Chagall does not depict a crucifix in The Martyr, Kenneth Silver states, ‘the artist obviously felt few constraints on his imagining of a Judaic version of the passion… in The Martyr, the horizontal bar of the cross has been eliminated.’42 This chapter will explore the key differences between Chagall’s private and public Crucifixion works. It will begin by comparing Apocalypse with White Crucifixion and The Martyr, exploring the different affects they have on the viewer. The chapter will then explore the similarities between Apocalypse and the preliminary sketches for White Crucifixion and The Martyr and consider how these works show the influence of George Grosz. Finally, this chapter will consider why Chagall seems to self-censor his public Crucifixion works. It will conclude that Chagall does so to engage the Western Christian viewer with the terrors of the Holocaust, and this shows that Chagall’s visual language for the Holocaust has an important pedagogical function.

One may compare Apocalypse with White Crucifixion and The Martyr to gain an understanding of how Chagall’s private and public works have different effects on the viewer. A first way in which Apocalypse differs from White Crucifixion and The Martyr is in how Christ’s body is represented.

39 Bohm-Duchen, p. 226

40 David Glasser, ‘Apocalypse on show with fifty selected master works from the Ben Uri Museum Collection’, in Apocalypse: Unveiling a Lost Masterpiece by Marc Chagall, ed. by David Glasser, Suzanne Lewis, Kate Drummond and Bilma Harree (London: Ben Uri Gallery, 2010), pp. 2-3 (p. 3)

41 ‘White Crucifixion’, The Art Institute of Chicago <https://www.artic.edu/artworks/59426/white-crucifixion> [accessed 22 April 2023] and ‘Le Martyr’, Kunsthaus Zürich <https://collection.kunsthaus.ch/en/collection/item/739/> [accessed 22 April 2023]

42 Kenneth Silver, ‘Fluid Chaos Felt by the Soul: Chagall, Jews, and Jesus’, in Chagall: Love, War and Exile, ed. by Susan Tumarkin-Goodman (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013), pp. 102-131 (p. 117)

Chapter One explored how, in Apocalypse, Chagall emphasises Christ’s Jewishness by depicting him to be wearing a prayer shawl correctly; over the head, so it drapes down the back. By depicting Christ to be wearing a prayer shawl as such, his body is exposed. This contrasts with White Crucifixion, where Chagall depicts Christ wearing a prayer shawl around his waist, and The Martyr, in which Christ is presented to be wearing a prayer shawl around his torso and groin. On the covering of Christ’s genitalia in Christian art, Robert Couzin argues, ‘Important elements of religious doctrine and widespread antiJewish polemic made it undesirable to show and uncomfortable to view biblical Jews, especially Jesus, as they really were [as circumcised].’43 One may therefore argue that, in Apocalypse, Chagall further drawsattentiontoChrist’sJewishnessbypresentinghim asnaked.Thisisbecausetheartistgoesagainst the convention in Christian art of covering Christ’s genitalia to hide the fact he was circumcised. In White Crucifixion and The Martyr, Chagall conforms more with this convention by using the prayer shawl to cover Christ’s genitals Another way in which Apocalypse differs from White Crucifixion and The Martyr is in how Chagall depicts Christ’s facial expression. Chapter One argued that, in Apocalypse, Christ’s gaping mouth makes him look like he is screaming, thus indicating the torment concentration camp victims experienced. Furthermore, though Chagall depicts one of Christ’s eyes to be closed,theother looksdirectlyat theviewer. Onemay arguethis puts the viewerin an uncomfortable and upsetting position as they are directly faced with an image of extreme suffering. This contrast with White Crucifixion and The Martyr as, in both works, Chagall depicts Christ with his eyes closed and his head tilting downwards. The artist thus makes Christ seem more passive. It can therefore be suggested that White Crucifixion and The Martyr are less distressing for the viewer to look at Apocalypse also differs from White Crucifixion and The Martyr as it includes a depiction of a Nazi officer. Chapter One explored how, by presenting a Nazi to be responsible for the Crucifixion, Chagall draws attention to the prolonged suffering the Nazis caused to the Jewish people during the Holocaust. However, Chagall does not include any imagery which relates as explicitly to the Nazi party, such as swastikas, in White Crucifixion or The Martyr. One may therefore argue that these works are less frightening for the viewer. Overall, it seems as though the works which Chagall created for public

43 Robert Couzin, ‘Uncircumcision in Early Christian Art’, Journal of Early Christian Studies, 26 (2018), 601-629 (p. 602)

display show a more traditional and less distressing representation of the Crucifixion This is evident when one compares White Crucifixion and The Martyr, which present Christ as passive and clothed, with Apocalypse, in which Christ is depicted as naked, screaming, and being killed by a Nazi.

However, it is key to consider that the preliminary sketches for White Crucifixion (fig. 10) and The Martyr (fig. 11) more overtly draw attention to Christ’s Jewishness and contemporary political violence. One may therefore find similarities between them and Apocalypse. For example, in the sketch for the Martyr, Chagall wrote the German phrase, ‘Ich bin Jude’ (‘I am a Jew’) above Christ’s head. In the sketch for White Crucifixion, the sign around the neck of the man in the bottom left-hand corner reads the same. Though, in these sketches, Chagall does not go as far as presenting Christ to be naked, one may compare these overt references to Judaism with Chagall’s assertion of Christ’s Jewishness in Apocalypse. This is because, in all theseinstances,theartist highlights how Jews werethetarget of Nazi persecution. Also, in the sketch for White Crucifixion, Chagall drew an inverted swastika on the banner above the burning synagogue On the right-hand side of the sketch for The Martyr, Chagall depicted a Nazi officer shooting a child in front of their mother These images can be compared with the Nazi officer in Apocalypse as they all bring the Crucifixion into a contemporary context and draw attention to the barbaric actions of the Nazis Therefore, although the comparison of Apocalypse with White Crucifixion and The Martyr makesitseemlike Apocalypse isanomalousamongstChagall’sCrucifixion works due to its frightening and upsetting imagery, these preliminary sketches show Chagall was consistently representing scenes of political violence from the 1930s onwards.

Literature on Chagall’s wartime practice does not tend to account for the artist’s use of explicit, violent imagery as scholars who write about the artist’s Crucifixion paintings often focus on his public works, such as White Crucifixion. One may argue Chagall’s representations of political violence show how he was influenced by the Berlin based artist, George Grosz. Chagall visited Berlin from May 1922 to August 1923.44 Bohm-Duchen writes that, during his stay, ‘Grosz... appears to have been one of the

44 Bohm-Duchen, pp 159-175

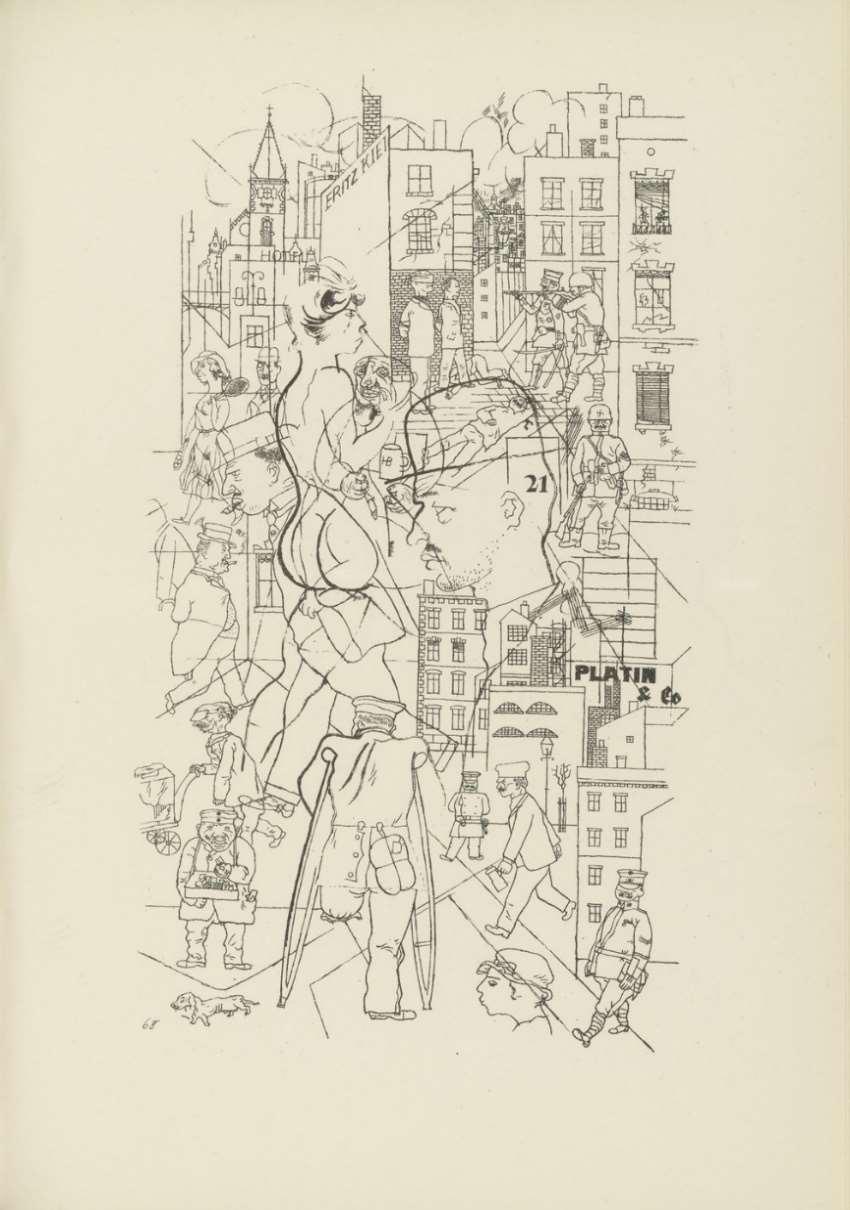

few visual artists with whom he [Chagall] established a personal relationship.’45 In 1933, Grosz emigrated to New York to avoid persecution by the Nazis 46 Following Chagall’s arrival in New York in 1941, works by the two artists were exhibited together in exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art, such as, 20th Century Portraits in 1942 and Modern Drawings in 1944 47 Furthermore, Grosz created a portrait of Chagall in 1958 (fig. 12). One may therefore suggest that Chagall would have had an awareness of Grosz’s work before and during World War II when he created White Crucifixion, The Martyr and Apocalypse. A first way in which Chagall may have been influenced by Grosz is in the composition of his works. One can see this when comparing Chagall’s sketches with a print such as Cross-Section (fig. 13). Though Grosz originally created Cross-Section in 1920, it was published as part of a book, entitled Ecce Homo, in 1922; the same year Chagall arrived in Berlin.48 Cross-Section shows depictions of various types of people who inhabited Berlin at the time of the Weimar Republic. For example, one can see a naked woman in the centre, representing a prostitute, a war veteran towards the bottom of the composition and depictions of paramilitaries dispersed around the work Grosz presents these figures to be overlapping each other and on top of buildings with shattered windows, drawing attention to how frenzied and intimidating the streets of Weimar Berlin were. One may argue this is similar to the chaotic compositions of Chagall’s Apocalypse and preliminary sketches for White Crucifixion and The Martyr, which emphasise the turbulent experience of Jews living in Europe during theHolocaust.Furthermore,in Cross-Section,detailssuchasfigure14ofparamilitariesshootingaman, may evoke the image of a child being shot in Chagall’s sketch for The Martyr Another way in which Chagall may have been influenced by Grosz is in his caricaturing of Nazi officers. In Grosz’s The Voice of the People is the Voice of God (fig. 15), the artist represents Nazis as animals. For example, in the bottom right-hand corner, one can see a figure with a donkey’s head and a swastika between its eyebrows and, in the bottom left-hand corner, one can see a figure with a hippopotamus-like head and a swastika on its earlobe. Grosz thus implies the Nazis are bestial and brutish. Chagall uses similar

45 Bohm-Duchen, p. 164

46 Ursula Zeller, ‘Grosz, George [Georg]’, Oxford Art Online (2003) <https://doi.org/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.T035094> [accessed 6 April 2023]

47 Monroe Wheeler, 20th Century Portraits (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1942), pp. 135-137, Monroe Wheeler, Modern Drawings (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1945), pp. 89-91

48 ‘George Grosz. Querschnitt (plate, folio 83) from Ecce Homo.’, MoMA <https://www.moma.org/collection/works/151600> [accessed 7 April 2023]

imagery in Apocalypse as he presents the Nazi officer to have a tail which makes him seem doglike, drawing attention to the aggressive, animalistic actions of the Nazi Party. Also, in 1927, Grosz made Shut Up and Do Your Duty which shows Christ on the cross wearing a gas mask and combat boots (fig. 16) One may argue Grosz therefore likens soldiers who fought in World War I to the figure of Christ, drawing attention to the suffering they had to endure. This would have been of personal resonance to Grosz as he volunteered as a soldier in World War I but was discharged as unfit for service in 1917 due to a nervous breakdown.49 One may liken the way Grosz adapts the figure of Christ to how Chagall emphasises Christ’s Jewishness in Apocalypse and the preliminary sketches for White Crucifixion and The Martyr. This is because both Grosz and Chagall bring the Crucifixion into the contemporary moment to highlight the respective, distressing experiences of being a soldier during World War I and a Jew during the Holocaust. Overall, it can therefore be suggested that Chagall was greatly influenced by Grosz as he emulates his compositional techniques and use of caricature to represent the frightening experience of Jews who suffered at the hands of the Nazis.

It is key to note, however, that Grosz’s influence on Chagall is less apparent in his public Crucifixion works. In the final version of The Martyr, Chagall ultimately did not include the image of a child being shot or the inscription, ‘Ich bin Jude’, above Christ’s head. Also, although Chagall did include swastikas and the inscription ‘Ich bin Jude’ on the sign around the man’s neck in White Crucifixion, he later painted over these. This is evident when one compares the work as it is now with figure 17, a photograph of White Crucifixion in its original state One may therefore question why Chagall self-censors his work. On White Crucifixion, Amishai-Maisels states, although exactly when Chagall altered the painting is unknown, ‘it is clear that the changes had been made by May 1944, at which time a photograph of the work was published in Liturgical Arts.’50 She suggests, ‘The changes… could… have been made either after Germany's invasion of France in May 1940, or after its defeat in June, because such clear symbols would have endangered the painting's safety if it had fallen into Nazi

49 George Grosz, Autobiography, trans. by Nora Hodges (New York: Macmillan, 1983), pp. 111-112

50 Ziva Amishai-Maisels, ‘Chagall's “White Crucifixion”’, Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies, 17 (1991), 139-181 (pp 140-142)

hands. Another possible date for the changes – again to safe-guard it – would be April 1941, when Chagall crated the painting for shipment via Lisbon to New York.’51 One may suggest this would also account for why Chagall did not include political symbols in The Martyr as the work was made during World War II and, at this time, the Nazis sought to control artistic and cultural production. In 1937, the Nazis opened the Degenerate Art Exhibition in Munich which presented over 650 avant-garde works as examples of art that was unacceptable and un-German.52 In the inventory of works confiscated by the Nazis, one can see at least twenty of Chagall’s paintings were taken and figure 18 shows the artist’s A Pinch of Snuff displayed in the exhibition (fig. 19).53 As Chagall was evidently a high profile figure, one may agree it is possible he censored works, such as White Crucifixion and The Martyr, to help ensure their safe transportation from German-occupied France to New York.

However, although this argument may apply to the Crucifixion works Chagall created before he left France, it does not bear much relevance when considering why Chagall continued to censor his works in New York In wartime America, propaganda overtly displayed anti-Nazi imagery. One can see this, for example, in a poster which shows a snake covered in swastikas with a moustache like Hitler’s and long fangs, presenting the Nazis as evil (fig. 20) Another example is figure 21, which shows a Nazi soldier clutching a knife with sharp teeth and blood dripping from his mouth, implying the Nazis are terrifying and dangerous. Due to the production and display of such propaganda, one wouldassumethat,inAmerica,Chagall couldhavepresentedimagerythatwascritical oftheNazi party without putting his work at risk of being seized or destroyed However, on White Crucifixion, AmishaiMaisels writes, ‘It is… evident that the changes [he made] were not meant to be temporary: Chagall did not repaint the details [of the swastikas and ‘Ich bin Jude’ inscription] upon arrival in New York’.54 He also continued to create works which were similar to the final versions of White Crucifixion and The Martyr. For example, in 1942, Chagall painted Yellow Crucifixion which contains no overt political

51 Amishai-Maisels, ‘Chagall's “White Crucifixion”’, p. 140

52 Stephanie Barron, ‘1937: Modern Art and Political in Prewar Germany’, in Degenerate Art: The Fate of the Avant-Garde in Nazi Germany, ed. by Stephanie Barron (New York: H.N. Abrams, 1991), pp. 9-24 (p. 9)

53 “Entartete” Kunst: digital reproduction of a typescript inventory prepared by the Reichsministerium für Volksaufklärung und Propaganda, ca. 1941/1942 (V&A NAL MSL/1996/7) (London: Victoria and Albert Museum, 2014)

54 Amishai-Maisels, ‘Chagall's “White Crucifixion”’, p. 142

symbols and presents a passive, partially clothed Christ (fig. 4). Furthermore, Chagall kept Apocalypse his own private collection and never developed the composition into a more finished painting. One may therefore suggest another reason why Chagall self-censored his works. Lang states that Holocaust art has, 'a significant pedagogical function… [as it brings] the fact of the Holocaust to the attention of a broad and diverse public who might otherwise know little about it.'55 One may argue this is the case for Chagall’s Crucifixion works. Most of Chagall’s audience in wartime and postwar New York would have been American, so were not subjected to Nazi persecution, like the artist was. The fact that Chagall’s American audience would have largely been Christian may account for why in his public works, such as White Crucifixion, The Martyr and Yellow Crucifixion, the artist presented Christ as partially clothed and did not include violent, political imagery. This is because, if the artist supposedly intended for the works to encourage the Western Christian viewer to engage and sympathise with the experience of Jews during the Holocaust, presenting Christ as naked and surrounded by images of political violence may have the adverse effect of making the viewer uncomfortable.

Toconclude, Apocalypse greatlydiffersfrommanyofChagall’sfinishedCrucifixionpaintings, such as White Crucifixion and The Martyr. This is because, in Apocalypse, Chagall presents Christ to be naked, thus emphasising his Jewishness, and creates a greater sense of terror by depicting Christ to be screaming and including a depiction of a Nazi officer. On the other hand, in White Crucifixion and The Martyr, Chagall represents Christ as passive and clothed and does not surround the Crucifixion with political imagery. However, Apocalypse shares many similarities with the preliminary sketches for White Crucifixion and The Martyr as all these works overtly draw attention to how Jewish people were the target of Nazi persecution and include depictions of Nazi officers engaging in violent acts. Furthermore, Apocalypse and these preliminary sketches show how Chagall was influenced by the compositional and caricatural techniques of Grosz. The differences between Chagall’s preliminary sketches and finished paintings lead one to question why Chagall seems to self-censor his Crucifixion works. Prior to fleeing German-occupied France, the artist may have censored his works to keep them

55 Lang, p. 49

safe from being seized or destroyed by the Nazis. However, this does not account for why Chagall continued to censor his works in New York where he could have been more openly anti-Fascist. It can therefore be suggested Chagall censored his works to engage a Western Christian audience. Chapter One concluded that Chagall developed a new visual language to aptly represent the Holocaust, and this is shown by how he makes the iconic image of the Crucifixion unfamiliar in Apocalypse One may still agreethisisthecasewhenconsideringthesimilaritiesbetween Apocalypse andthepreliminarysketches for White Crucifixion and The Martyr. However, one can argue the finished versions of White Crucifixion and The Martyr show another reason why Chagall may have done this. As it is evident Chagall adapted his representations of the Crucifixion in his public works to engage his American audience, it can be suggested Chagall also developed a new visual language to effectively inform the Western Christian viewer about the Holocaust. This further shows why the Crucifixion is such a significant image in Chagall’s visual language as it can be adapted to suit both functions.

Chapter Three: Apocalypse en Lilas, Capriccio as Émigré Art and Jewish Symbolism in Chagall’s Wartime Practice

When Chagall was in New York, he associated himself with many other artists who, like him, had fled to America following the outbreak of World War II to avoid persecution by the Nazis. For example, he attended gatherings of émigré artists held at the studios of the French painter, Amédée Ozenfant, and Polish-French painter, Moïse Kisling. In 1942, Chagall was included in an exhibition at the Pierre Matisse Gallery,entitled Artists in Exile, where his paintings were displayed alongside works by other artists who had also fledfrom Nazi Europe.56 Figure 22 shows a group photograph of the artists who contributed to the exhibition. Bohm-Duchen states, ‘any impression of unity or community conveyed by this photograph is misleading… Chagall kept firmly to himself.’57 Bohm-Duchen thus implies the only thing relating Chagall to these other artists is the fact they were all émigrés and that they bore no influence on one another’s practices. However, one may challenge this idea by comparing Chagall’s works with those by other artists who were included in this exhibition, namely, Jacques Lipchitz and Roberto Matta. This chapter will firstly compare Chagall’s Apocalypse with Lipchitz’s The Sacrifice (fig. 23) and Matta’s A Grave Situation (fig. 24). It will explore how Chagall, Lipchitz and Matta all mix Christological imagery with symbols from their own cultures in response to World War II. The chapter will then consider how scholars have written about these artists’ uses of personal, cultural imagery. It will question why, unlike literature on Lipchitz and Matta, scholarship on Chagall does not present his use of religious imagery as a response to the Holocaust. The chapter will then challenge this scholarship by reinterpreting Chagall’s wartime works which focus on Jewish symbols, such as The Flying Sleigh (fig. 6) and Day and Night (fig. 7). It will conclude that Chagall’s visual language for the Holocaust is not only apparent in his Crucifixion works, such as Apocalypse, but in many other of his wartime paintings.

56 Bohm-Duchen, p. 250

57 Bohm-Duchen, p. 250

Jennifer Swan states, for artworks created independent of an organised religious commission, 'the crucifixion… functions as a visual metaphor to establish or support the nature of an individual's suffering' 58 It can be argued that this is the case for Apocalypse, as Chagall brings the Crucifixion together with Jewish imagery to draw attention to Jews’ suffering during the Holocaust. One may compare Chagall’s mixingof the Crucifixion and Jewish symbols with the practices of other artists who similarly blend Christian imagery with symbols from their own culture to represent the events of World War II. This can be seen, for example, in sculptures by Jacques Lipchitz. Lipchitz was born to a Jewish family in Lithuania and spent most of his life working as an artist in France. The German occupation of France in 1940 caused him to flee to New York.59 Matthew Affron states that Lipchitz, ‘was very concerned with the social and political functions of sculpture. He endeavoured to fashion works… as responses to the social and political conflicts of the age.’60 One may argue this is the case for The

Sacrifice. Lipchitz depicts a figure grabbing a screaming rooster by the neck with one hand and holding a dagger in the other. As the dagger is pointed towards the rooster’s breast, it is evident the rooster is about to be killed Lipchitz thus represents the Jewish ritual of kapparot In doing so, he draws attention to the brutal slaughtering of Jews during the Holocaust, much like Chagall does through his depiction of a rooster in Apocalypse Although Lipchitz does not represent the Crucifixion in The Sacrifice, at the feet of the figure, he depicts a lamb. Affron states, ‘[an] important facet of the émigré sculptor's [Lipchitz’s] response to current events [was] his use of biblical… subjects as vehicles for symbolic reflection on the struggle against tyranny.’61 It can therefore be suggested that, in The Sacrifice, the lamb represents Christ This is because, in the Gospel of John, Christ is described as, ‘the Lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world.'62 By bringing the lamb, a Christian symbol of sacrifice, together with the Jewish symbol of the rooster, Lipchitz further emphasises the ruthless killing of Jews during the Holocaust. This is similar to how Chagall fuses the figure of Christ with a rooster in Apocalypse to

58 Swan, pp 15-16

59 Alan Wilkinson, ‘Lipchitz, Jacques [Chaïm Jacob]’, Oxford Art Online (2003) <https://doi.org/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.T051259> [accessed 13 April 2023]

60 Matthew Affron, ‘Constructing a New Jewish Identity’, in Exiles + Emigres: The Flight of European Artists from Hitler, ed. by Stephanie Barron, Sabine Eckmann and Matthew Affron (Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1997), pp. 114-127 (p. 121)

61 Affron, p. 123

62 John 1:29

represent the suffering of Holocaust victims One may therefore agree with Swan’s argument that, in non-Christian art, Christ functions, ‘as a visual metaphor to establish or support the nature of an individual's suffering' 63 This is because, in their works, both Chagall and Lipchitz mix Jewish symbols with representations of Christ to emphasise the anguish of their people during the Holocaust.

Another artist that can be compared with Chagall and Lipchitz is Roberto Matta as, in his paintings, he mixes Christian imagery with symbols from his own culture. Matta was a Chilean artist who worked around Europe in the early 20th century. Matta was in Paris when World War II broke out and he subsequently fled to New York.64 He created a number of works in response to the horrors of the war, including A Grave Situation. 65 In the painting, Matta depicts a cruciform figure with a body that lookslike atotem pole.Thisis evident when one comparesit with figure 25,which showsMapuche totempolesinChile.Inpre-HispanicChile,totemshada socialfunctionofcommemoratingtheancestry of tribes.66 They thus, as Celia Rabinovitch states, ‘formed a protective, emblematic image for kinship’.67 It can be argued that, by fusing the image of a totem with the Crucifixion, Matta draws attention to the destructive nature of war on families and communities. This is similar to how, in Apocalypse, Chagall surrounds the Crucifixion with imagery relating to family, such as a mother nursing a child and houses from shtetls, thus emphasising the chaos war causes to domestic life One may therefore agree with Swan’s argument that wartime and postwar Crucifixion artworks, 'created independent of an organised religious commission… present the emergence of an archetype through creative expression.'68 This is evident when comparing Matta’s A Grave Situation with Chagall’s Apocalypse and Lipchitz’s The Sacrifice Although Chagall and Lipchitz use Jewish symbols whereas

63 Swan, p.15

64 Paul Overy, ‘Matta (Echaurren), Roberto (Antonio Sebastián)’, Oxford Art Online (2020) <https://doi.org/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.T055993> [accessed 14 April 2023]

65 ‘Surrealism Comes to America: The Totemic Mind’, Cornell University Library (2014) <https://rmc.library.cornell.edu/surrealismandmagic/exhibition/america/totemicmind.html> [accessed 14 April 2023]

66 Richard Latcham, ‘The Totemism of the Ancient Andean Peoples’, The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, 57 (1927), 55-87 (p. 59)

67 Celia Rabinovitch, ‘Surrealism Through the Mirror of Magic’, Cornell University Library (2014) <https://rmc.library.cornell.edu/surrealismandmagic/essay.html> [accessed 14 April 2023]

68 Swan, p. 16

Matta uses imagery relating to Chilean history, they all comparably mix imagery from their own cultures with representations of Christ to draw attention to the horrors of war.

It is key to consider how scholars have responded to these artists’ uses of imagery from their own cultures. Most literature on Lipchitz implies that in his works created around World War II, the artist uses Jewish symbols to represent the Holocaust. For example, on Lipchitz’s The Prayer (fig. 26), Affron states, ‘This sculpture represents the enactment of an ancient and esoteric ritual [kapparot]...

Conceived… during the darkest days of the war, this work was offered as a prayer for the Jews of Europe.’69 As this isalso thecasefor The Sacrifice, onemayagree with Affron’sargument that Lipchitz uses the symbol of the rooster to emphasise the desperate situation of Jews during the Holocaust. Comparably, most scholarship on Matta suggests the artist uses symbols from pre-Hispanic Chilean culture to represent the disruption caused by World War II. For example, on the painting How-Ever (fig. 27), Christopher Knight states, the work shows, ‘a kind of mechanized, assembly-line horror that characterized Auschwitz, as robot-like totems perform monstrous deeds.’70 One may agree with Knight’s interpretation as, in Matta’s paintings, totems, which represent kinship, are presented in extremely disturbing and upsetting contexts, thus drawing attention to the disruptive and dehumanising acts of the Nazis Literature on Chagall, however, differs from that on Lipchitz and Matta. Around the time of World War II, as well as his Crucifixion paintings, Chagall made many works which focused on Jewish symbols. For example, in the same year as Apocalypse, Chagall created The Flying Sleigh and Day and Night Although scholars have interpreted Chagall’s Crucifixion paintings to be responses to the Holocaust, these works are rarely presented as bearing any relation to contemporary politic turmoil For example, on the paintings Chagall made immediately after World War II, Voerman states, ‘his [Chagall’s] new love for Virginia Haggard and the birth of their son drastically altered his life circumstances in the first years after the war ended. Chagall addressed this new phase in his life… in [his] works’ . 71 Bohm-Duchen similarly suggests the main influence on Chagall’s work in 1945 was his

69 Affron, p. 124

70 Christopher Knight, ‘‘Matta in America’: Decade of Creativity Leaves a Lasting Mark’, Los Angeles Times (2001) <https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2001-oct-13-ca-56628-story.html> [accessed 15 April 2023]

71 Voerman, p. 35

new relationship with artist, Virginia Haggard, following his wife, Bella Rosenfeld, passing away. On The Flying Sleigh (fig. 6), Bohm-Duchen argues, ‘Chagall's relationship with Virginia goes a long way to explain the joyous and almost disconcertingly life-affirming element that exists in much of the work he produced shortly after Bella's death... the couple and young child The Flying Sleigh of 1945 triumphantly defy the forces of gravity ’72

One may question why, unlike in literature on Lipchitz and Matta, scholars tend to interpret such works by Chagall biographically, suggesting they represent his personal relationships, as opposed to considering how they may be responses to contemporary political violence. It can be argued this is because recent scholarship has been greatly influenced by the understanding of Chagall’s practice that waspromotedintheartist’slifetime.Forexample,in1946,amajorretrospectiveexhibitionofChagall’s work was put on at the Museum of Modern Art. In the catalogue, curator, James Johnson Sweeney states, ‘Chagall arrived from the East with a ripe color gift, a fresh, unashamed response to sentiment, a feeling for simple poetry and a sense of humor.’73 Sweeney thus characterises Chagall’s work as joyous, bright, and nostalgic. Sweeney also states, ‘In September 1944, Madame Chagall died. The loss was a staggering one to Chagall. His thoughts and work for months seemed fixed irremediably on the past.’74 Sweeney therefore implies Chagall’s works can be understood as responses to events which took place in the artist’s personal life. One can see how recent scholars, such as Bohm-Duchen, may have been influenced by how Sweeney presents Chagall’s works when considering how she interprets The Flying Sleigh One may, however, challenge such scholarship which predominantly considers how Chagall’spersonallifeinfluencedhiswork.ChapterTwoexploredhowChagallself-censoredhispublic Crucifixion works by following conventions of Christian art and removing violent political imagery to engage a largely Western Christian audience in America. Such acts of self-censorship show that, even if it is not initially apparent in Chagall’s public works, the artist was consistently representing the devastation caused by the Holocaust. One may argue this is the case for paintings such as The Flying

72 Bohm-Duchen, p. 268

73 James Johnson Sweeney, Marc Chagall (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1946), p. 7

74 Johnson Sweeney, p. 71

Sleigh and Day and Night as, although they contain no apparent references to the politically violent acts of the Nazis, Chagall alludes to such horrors through Jewish symbolism.

In The Flying Sleigh, one can see a rooster with the hind legs of a horse guiding a sleigh away from a group of houses which resemble a shtetl (fig. 8). On the sleigh, Chagall has depicted a family with a father, mother, and child. The dark night sky makes the setting seem ominous and the ghostly faces in the top right corner create a sense of foreboding. The analysis of Apocalypse and exploration of Lipchitz’s work have shown how Jewish artists use the symbol of the rooster to draw attention to the loss of Jewish life during the Holocaust. It can therefore be suggested The Flying Sleigh represents a family being led away from their home to their death, drawing attention to the fate of many Jewish families during the Holocaust. Additionally, it is key to note that sleighs were the focus of a work Chagall created in 1943, entitled, The War (fig. 28). At the bottom of this painting, Chagall uses bold red paint on top of a white ground, making it look as though one of the sleighs is sitting on top of bloodsoakedsnow. Thesleigh above hovers over upturned housesandabodylyinginthe middleof the street, creating a sense of chaos. Due to the work’s title, it is therefore evident that Chagall associates sleighs with the upheaval caused by war. This further supports the interpretation of The Flying Sleigh representing Jewish families being killed during the Holocaust. Moreover, Chagall’s Day and Night may also be interpreted as a response to the Holocaust (fig. 7). In the painting, one can see the figure of a woman fused together with a rooster. This composition is similar to Apocalypse, in which Chagall overlaps the body of Christ with a rooster, drawing attention to the idea of sacrifice. One may thus suggest that, in Day and Night, Chagall implies the woman has passed away. This is emphasised by her face being depicted in a bluish white, making her seem ghostly to the viewer. The setting is very similar to The Flying Sleigh as it has a dark, ominous sky and a shtetl at the bottom of the composition. Also, above the shtetl and to the right of the rooster, Chagall depicts a sleigh, which the artist evidently associated with war. One may therefore suggest Day and Night, like The Flying Sleigh, represents the loss of Jewish life caused by the Holocaust.

To conclude, one may agree with Swan’s argument that wartime and postwar Crucifixion artworks, 'created independent of an organised religious commission… present the emergence of an archetype through creative expression.'75 This is evident when one considers how émigré artists, like Chagall, Lipchitz, and Matta, mix Christological imagery with symbols from their own cultures to represent the horrors of World War II In Chagall’s Apocalypse and Lipchitz’s The Sacrifice, roosters are depicted alongside representations of Christ. By bringing together Jewish and Christian symbols which represent sacrifice, both Chagall and Lipchitz emphasise the devastating loss of Jewish life during the Holocaust. Comparably, in A Grave Situation, Matta fuses the Crucifixion with a totem, which were used to commemorate ancestry in pre-Hispanic Chile. One may compare this with how, in Apocalypse, Chagall surrounds the Crucifixion with imagery relating to domesticity, such as depictions of a mother nursing a child and a shtetl. Both artists thus draw attention to the destruction war causes tofamiliesandcommunities. Itistherefore evident that,likeChagall,manyémigréartists usedreligious and cultural imagery to develop visual languages in response to World War II. This chapter also exploredhow, althoughscholarship onLipchitzandMatta presentstheir depictionsof personal,cultural imagery to be representative of war, this is not the case for Chagall. Although scholarship on Chagall presents his Crucifixion works to be representative of the Holocaust, other wartime works of his, such as The Flying Sleigh, have been interpreted biographically, as responses to his romantic relationships However, paintings like The Flying Sleigh can be reinterpreted when one considers how Chagall may have been using the rooster as a symbol of sacrifice. Overall, it is therefore evident that Chagall’s visual language for the Holocaust is not only apparent in his Crucifixion works, such as Apocalypse, but in many of his wartime paintings

75 Swan, p. 16

Conclusion

This dissertation has shown the significance of Apocalypse en Lilas, Capriccio in Chagall’s oeuvre as the analysis of the work provides insight into how the artist developed a visual language to respond to the Holocaust. The dissertation set out to understand why the artist uses Christological symbolism, consider Apocalypse’s deeply political nature, compare Chagall’s work with that of other émigré artists and explore whether these elements can influence the interpretation of other works by Chagall. The first chapter considered the significance of the Crucifixion in Apocalypse. It showed that Chagall draws attention to Christ’s suffering to represent the hardship of Jewish concentration camp prisoners and refugees, emphasises Christ’s Jewishness to challenge the othering of Jews by the Nazis and the Church, and alludes to the Resurrection, signifying the repeated attempts made to eliminate Jews throughout history. The chapter concluded that, as Chagall adapts such an iconic image to represent the Holocaust, the artist showed the need for a new visual language to aptly represent such a horrific period in history

The second chapter compared Apocalypse with other of Chagall’s wartime Crucifixion works It showedthat althoughfinishedpaintings,suchas White Crucifixion and The Martyr,appear tobemore traditional and less engaged with contemporary politics than Apocalypse, their preparatory sketches reveal that this idea is flawed It argued that the politicised imagery in both Apocalypse and these preparatory sketches show how Chagall was influenced by Grosz. The chapter subsequently questioned why Chagall did not include violent, political imagery in his public works, arguing Chagall selfcensored his Crucifixion paintings to engage a Western Christian audience who would not have directly experienced the Holocaust. The second chapter therefore concluded that Chagall’s visual language for the Holocaust also has an important pedagogical function.

The third chapter began by exploring the similarities between Apocalypse and works by other émigré artists in New York. It compared Apocalypse with Lipchitz’s The Sacrifice and Matta’s A Grave Situation and showed how all these artists mix symbols from their own culture with Christological

imagery to represent World War II. It is therefore evident that Chagall was working and exhibiting alongside a number of artists who were similarly creating their own visual languages for the Holocaust. The chapter then explored why, unlike literature on Lipchitz and Matta, scholars consider many of Chagall’s wartime works, such as The Flying Sleigh, to be responses to his romantic life. It argued that such interpretations may be challenged when considering how Chagall, like Lipchitz, uses Jewish symbolism to represent the suffering of Jewish people during the Holocaust. The chapter ultimately concluded that Chagall used his visual language for the Holocaust across his wartime outputs and not just in his Crucifixion paintings.

The comparison of Chagall’s work with that of other artists who also responded to the advents of World War II has been a key element of this dissertation. The second chapter explored Grosz’s influence on Chagall and the third chapter considered Chagall’s work alongside Lipchitz’s sculptures and Matta’s paintings One may therefore consider the effectiveness of Chagall’s work as a response to the Holocaust in comparison with that of other artists The final chapter showed how Chagall, Lipchitz and Matta all representedthe terrors of the Holocaust by mixing biblical imagery with personal, cultural symbols. It can therefore be argued that their works all respond to the Holocaust to the same effect. The dissertation also showed that other Crucifixion works by Chagall, such as White Crucifixion and The Martyr, are not as explicitly political as Apocalypse and argued this is because Chagall intended for his public Crucifixion works to engage the Western Christian viewer. It is key to note that works by Lipchitz, like The Sacrifice and The Prayer, and works by Matta, like A Grave Situation and How-Ever similarly do not contain overt political imagery such as swastikas. One may therefore argue Chagall’s public Crucifixion works respond to the Holocaust as effectively as Lipchitz and Matta’s artworks. However, one may question the effectiveness of other wartime works by Chagall, such as The Flying Sleigh and Day and Night in comparison with works by Lipchitz and Matta. It is evident that scholars have not understood paintings by Chagall that do not depict the Crucifixion to be responses to the Holocaust. This would seem to suggest such works are therefore not as effective. However, this assumption may be challenged as it is evident that scholars have understood works by other Jewish artists, such as Lipchitz, to use cultural symbols, like the rooster, in response to theHolocaust. One may

suggest that more research therefore needs to be done on Chagall’s general wartime output and how it was understood by the artist’s contemporaries.

It is key to note that Chagall’s interactions with other artists were the most difficult elements of the dissertation to research due to the limitations of existing scholarship. The literature review in the introduction drew attention to how scholarship often focusses on the work Chagall created in Belarus, France, and Germany before World War II. This made researching the development of Chagall’s practice in wartime and postwar New York challenging. However, what became more evident when writing the dissertation was the great extent to which scholars have isolated Chagall from his contemporaries. The attitude that Chagall was detached from modern art history is shown by BohmDuchen, for example, who describes him as, ‘virtually alone among the major twentieth-century artists’ 76 Also, in the catalogue for Chagall: Love, War, and Exile, which set out to combat the lack of exhibitions on Chagall’s political works, Tumarkin-Goodman writes, ‘Chagall was a unique and idiosyncratic artist at odds with the century in which he lived.’77

This dissertation has contrarily shown that exploring Chagall’s engagement with his contemporaries is crucial for understanding the visual language he developed for the Holocaust. It may thereforebesuggestedthattofurtherresearchthistopic,itwouldbeproductivetocontinueinvestigating Chagall’s interaction with fellow artists A starting point for this could be greater exploration of the Artists in Exile exhibition. As well as Chagall, Lipchitz and Matta, major surrealist painters, Yves Tanguy, Max Ernst, and Andre Masson, were included in the show, as were abstract painters, Fernand Leger, and Piet Mondrian. One could find numerous ways to compare their works. For example, as scholarship has often suggested that Chagall’s work has, as Meyer states, a sense of ‘mysterious nocturnal, magic’, his engagement with Surrealist practices could be considered.78

76 Bohm-Duchen, p. 4

77 Tumarkin-Goodman, p. 15

78 Meyer, p. 451

To conclude, the analysis of Apocalypse en Lilas, Capriccio causes a rupture in scholarship on Chagall which seeks to root him in early 20th century European art history and present him as an individualist. Apocalypse shows that Chagall was complexly engaging with contemporary political turmoil using many visual tropes such as biblical imagery, political caricature, and Jewish symbolism The violent clashing of these features imbues them with newfound significance and forms a visual language for the Holocaust. This may lead one to reconsider the elements Apocalypse shares with other works by Chagall and fellow émigré artists. This line of research is pivotal for the reassessment of Chagall’s influence on and involvement in wartime and postwar art.

Bibliography

Primary sources

Chagall, Marc, ‘Unity – Symbol of Our Salvation: Speech at the Conference of the Committee of Jewish Writers, Artists and Scientists, February 1944’, in Marc Chagall on Art and Culture, ed. by Benjamin Harshav (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2003), pp. 87-91

“Entartete” Kunst: digital reproduction of a typescript inventory prepared by the Reichsministerium für Volksaufklärung und Propaganda, ca. 1941/1942 (V&A NAL MSL/1996/7) (London: Victoria and Albert Museum, 2014)

Johnson Sweeney, James, Marc Chagall (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1946)