In the footsteps of German architects in Krefeld & Cologne

17-18.12.2021

PROGRAM

Friday 17.12

07:30

Departure Gustav Mahlerlaan next to breakfast club

10:00 Urbane Nachbarschaft Samtweberei 11:30 Museum Haus Lange + Haus Esters

13:30 Ungers Archiv + surroundings

17:30 Check in hotel (Maison Marsil)

18:00 Weihnachtsmarkt + restaurant

DISTANCES BY CAR

Gustav Mahlerlaan - Urbane Nachbarschaft 2h30 Urbane Nachbarschaft - Haus Lange + Esters 0h15 Haus Lange + Esters - Ungers Archiv 1h00 Ungers Archiv - Aachener Straße 0h10 Aachener Straße - Christi Auferstehung Kirche 0h10 Ungers Archiv - Belgisches Viertel 0h15

Saturday 18.12

09:00 Breakfast

10:30 Walk through Künstlerviertel neighbourhood

11:00 Visit Heinze-Manke Haus

13:30 Visit Am Kölner Brett

14:00 Walk next to Dom

15:00 Kolumba Museum

17:00 Wallraf Richartz Museum

18:00 Departure Amsterdam

Hotel - Künstlerviertel 0h30

Künstlerviertel - Kölner Brett 0h40

Kölner Brett - Center 0h15 Köln - Amsterdam 3h30

Planned, built, destroyed - in the footsteps of Mies van der Rohe

Everything has been said about Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, right? Born in Aachen in 1886, he developed into one of the most renowned and well-known architects in the world - with iconic buildings such as the New National Gallery in Berlin and buildings such as the Seagram Building in New York. Many publications have appeared on his life and work. However, the North Rhine-Westphalian projects, with the exception of the Krefeld villas Lange and Esters, received astonishingly little attention, because these projects in particular give an impressive illustration of his life - from the Rhine craft apprentice to the Bauhaus director to the globally active architect. Within the architecture of the 20th century, his works in today’s North Rhine-Westphalia reflect the development from Jugendstil to International Style.

And even though Mies developed from Berlin and Chicago into one of the most influential architects of the 20th century, his ties to his homeland continue to be “ Rhinelander ”in North Rhine-Westphalia like a red thread through his entire life and work. He cultivated networks and worked on around a dozen projects in Aachen, Essen and especially in Krefeld. Many of them were realized, some remained a vision, others were destroyed.

The architecture in Krefeld occupies a special position within the work of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. For about eleven years he benefited from good contacts with the “Krefeld friends” around the silk manufacturer Hermann Lange. Together with Josef Esters and other representatives of the local textile industry, Lange founded the VereinigteSeidenwebereien AG (Verseidag) in 1920. This merger led to the construction of an industrial complex, which was implemented between 1925 and 1938 largely with the participation of Mies van der Rohe. Of the total of six Krefeld projects, three were realized with the houses for the Lange and Esters families and the silk factory. Three drafts were not implemented. The architecture in Krefeld is therefore very closely related to the work of an outstanding protagonist of the 20th century architecture.

01 Urbane Nachbarschaft Samtweberei, 2021

01 Urbane Nachbarschaft Samtweberei, 2021

housing commercial neighbourhood living room public courtyard garden traffic space/parking space

02 Haus Lange - Mies van der Rohe, 1928-30

Haus Esters, KrefeldGartentür (von außen, Detail)

stellung des Deutschen Werkbundes „Die Wohnung“

Fensteröffnungen Nutzgartens

Foto: Volker Döhne

KrefeldGartentür (von außen, Detail)

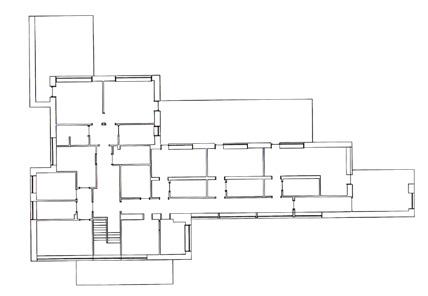

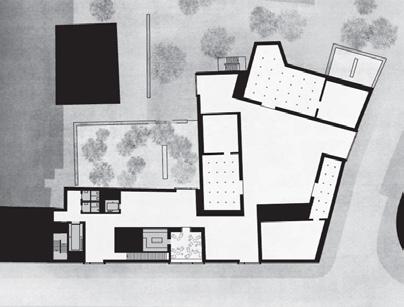

Haus Lange, first floor ground floor

Haus Lange, erste Etage (2019)

Zur Weltausstellung in Barcelona entwickelte er seine wohl radikalste Vision eines offenen, vom Material bestimmten Gebäudes, den Ausstellungspavillon des deutschen Beitrags, heute bekannt als BarcelonaPavillon. Parallel arbeitete er an der Villa Tugendhat in Brünn (heute Brno, Tschechien). Hier kann der Architekt viele visionäre Ideen, die er für die Häuser Esters und Lange ebenfalls angedacht hatte, Realität werden lassen. Gelernt hatte Mies van der Rohe bei Bruno Paul und Peter Behrens in Berlin. Als letzter Direktor sollte er 1933 das Bauhaus in Berlin schließen. Mit der Gründung seines Chicagoer Büros 1938 und seinen Hochhäusern, konstruiert aus Modulen, Rastern und Vorhangfassade, begann schließlich seine internationale Karriere in den Vereinigten Staaten.

02 Haus Esters - Mies van der Rohe, 1928-30

first floor

Between 1927 and 1930 the Lange and Esters houses were built in the north of Krefeld for the families of the two founding directors of the United Seidenwebereien AG. The choice to hire Mies van der Rohe probably went back to Hermann Lange, who got to know the architect in the field of avant-garde art and the German Werkbund.

The two-story houses are made up of staggered cubes. Its steplike structure is particularly evident on the back, while the street side looks closed and compact. The facades are made of reddish clinker brick, the construction is double-shelled and supported by steel beams. This is made possible by the large windows on the garden side. In the Lange house, the large, undivided glass surfaces can be lowered to a low parapet height in the floor. In this way, interior and exterior space almost merge, one of the contemporary principles of Mies van der Rohe.

In the first drafts from the summer of 1927, the interior spaces were formed by wall panels. This open, flowing floor plan, which is so characteristic of Mies, did not meet the needs of the two builders, so that a more conventional division of space prevails today.

In the interior design of both houses, Mies sometimes relied on pieces he designed. He designed his own ensemble for the lady’s room in the Lange House. However, the furnishings he designed with Lilly Reich for the entrance halls of the villas in 1930 were not implemented. The client’s extensive collection of contemporary art was integrated into the Lange building. At the client’s request, Haus Lange has been used as a museum for contemporary art since 1955, and Haus Esters has been used for this purpose since 1981. The ensemble is now part of the Krefeld art museums.

Before the Second World War, the flourishing textile industry gave Krefeld the nickname “a city like velvet and silk”. In 1930 the Verseidag planned their new headquarters there. The managing directors Josef Esters and Hermann Lang entrusted Ludwig Mies van der Rohe with the project, which was implemented in several construction phases.

As early as 1931, a steel-framed storage building for men’s feed, the HE building, and the adjoining dye works were completed. The facade of the HE building, built as a long transom, is structured by large, dark ribbon windows. Next to it is the single-storey hall of the dye works, spanned with a shed roof structure, which ensures uniform incidence of light from the north. From 1933, the hall was expanded from four to eleven shed roofs in further construction phases and the HE building was increased by two storeys.

By 1937, further buildings were built on the Verseidag site based on Mies ‘designs. At this point in time, the architect was only active in an advisory capacity. He later criticized some of the buildings because they did not correspond to his planning ideas. This may be one reason why the project was not one of Mies ‘favorite buildings.

The factory complex was listed as a historical monument in 1999 and partially renovated. The last production sites closed in 2009. The “Mies van der Rohe BusinessPark” is currently being built there at the instigation of a private investor. The individual buildings - based on designs by Mies and those based on his style - are now being renovated step by step and given new uses.

Fabrikgebäude der vereinigten Seidenwebereien AG03 Fabrikgebäude der vereinigten Seidenwebereien AG - Mies van der Rohe, 1930-38

04 Christi Auferstehung Kirche - Gottfried Böhm, 1968-70

04 Christi Auferstehung Kirche - Gottfried Böhm, 1968-70

Böhm was born into a family of architects in Offenbach, Hessen. After graduating from Technical University of Munich in 1946, he studied sculpture at a nearby fine-arts academy. After graduating in 1947, Böhm worked for his father until the latter’s death in 1955 and later taking over the firm. During this period, he also worked with the “Society for the Reconstruction of Cologne” under Rudolf Schwarz.

In 1951 he travelled to New York City, where he worked for six months in the architectural firm of Cajetan Baumann. While travelling in America he met two of his greatest inspirations, German architects Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Walter Gropius. He has been considered to be both an expressionist and post-Bauhaus architect, but he prefers to define himself as an architect who creates “connections” between the past and the future, between the world of ideas and the physical world, between a building and its urban surroundings. In this vein, Böhm always envisions the colour, form, and materials of a building in relationship with its setting.

Interesting movie about Gottfried Böhm and his three sons:

Concrete Love - https://www.archdaily.com/786213/concretelove-documentary-film-gottfried-bohm-the-son-grandson-husband-and-father-of-architects?ad_medium=gallery

Gottfried BöhmChristi Auferstehung Kirche

Christi Auferstehung is a Catholic church in the district of Lindenthal in Cologne. It was built between 1968-1970 by architect Gottfried Böhm and later consecrated in 1971. It is regarded as a typical example of sculptural buildings by the architect and there are similarities in the design with The Pilgrimage Church which was designed at the same time.

The plan for the new church designed by Böhm has an irregular polygonal shape. While the laterally projecting parish is made completely of reddish brick, which alternates in the actual church building from brick and concrete, which is a contrast continued through the interior. A slender spiral stair tower dominates the building on the northwest corner.

Originally, the sloping concrete surfaces of the roof were uncovered, however due to weather conditions the material has had to be covered with lead on the inclined surfaces.

Together with the neighboring building „Jobi“ (06), this multifamily building is one of the earliest works by O.M. Ungers, done in partnership with Helmut Goldschmidt. The front façade of the building presents a taunt, abstract, and smooth rendered plane with perfectly square window openings. The otherwise clearly symmetrical composition is disrupted by the location of the entrance, three windows at the entry level and landings between upper levels, and two small windows to the basement. The floor plan for the three levels is a simple adaptation of the nine-square grid: an apartment on either side of the staircase, with a smaller room facing the street and the larger one toward the court, separated by the bathroom and closet. The central third of the composition contains the common staircase, the kitchens of the two apartments, and the two terraces also facing the court. The clear composition of the front façade, foretells future explorations by Ungers, seen as early as in the building on Eckewartstraße in Köln-Nippes

The “Kleiderfabrik Jobi“ is one of the earliest projects by Ungers in partnership with Helmut Goldschmidt. The composition of both front and rear façades of the “Jobi“ building is an asymmetrical arrangement with the entrance and vertical circulation core, as well as services, on the extreme left side from the front, with three pairs of square window openings appearing as crisp voids. The first of the infill buildings designed by him, it is resolved in stark contrast to the later projects in Köln-Riehl, on Aachener Straße (07) and the Hansaring. Together with the multifamily building behind it, facing Hültzstraße (05), the building that was originally a clothing factory is among the earliest explorations by Ungers on the abstract composition based on the 1:1 (square) proportion. Today the building serves other purposes, but its rendered façade has been restored to nearly its original condition, save for the sculptural metal element added along its base.

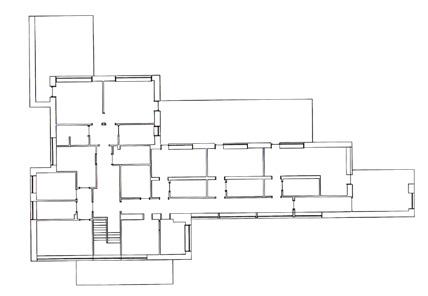

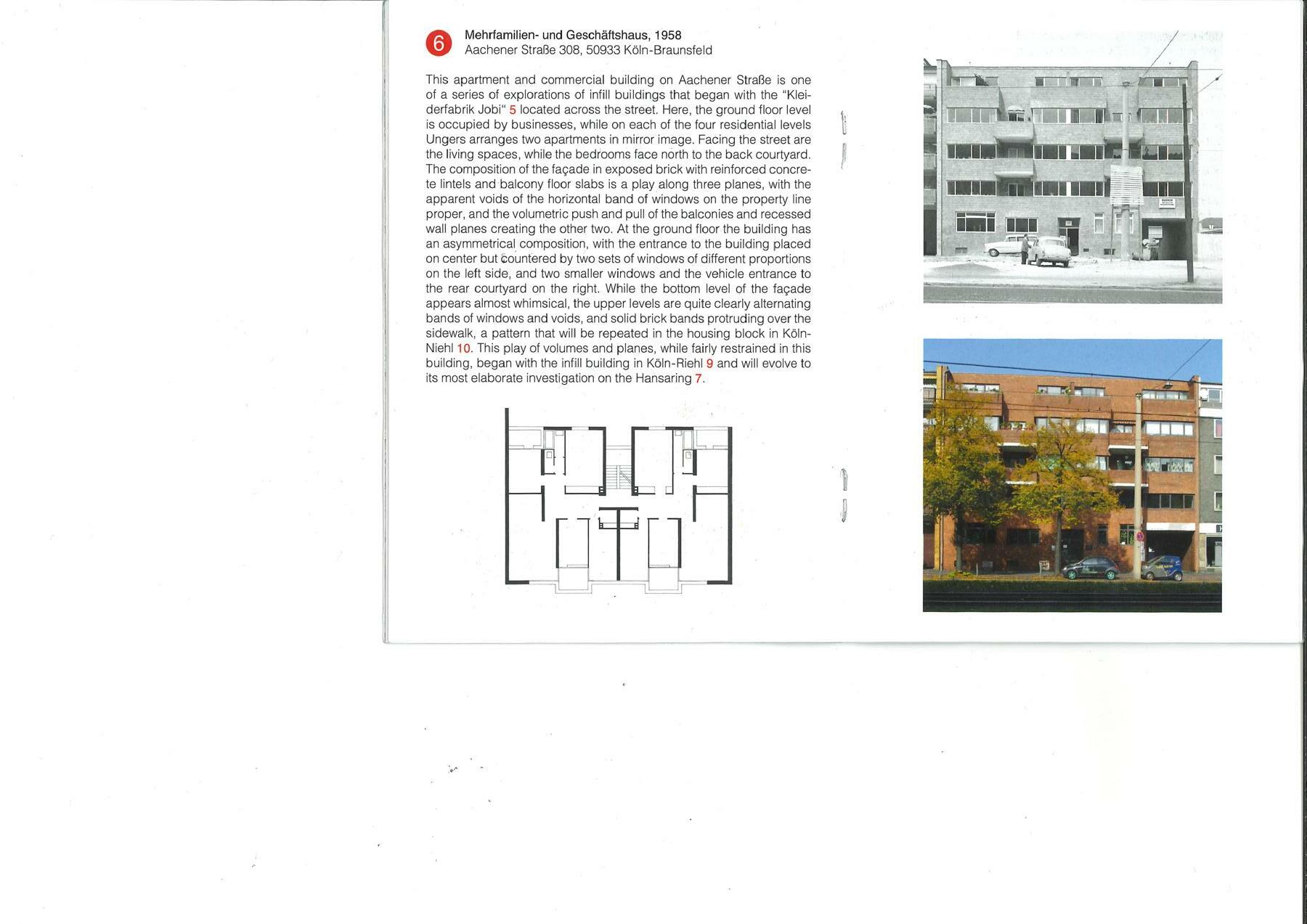

This apartment and commercial building on Aachener Straße is one of a series of explorations of infill buildings that began with the “Kleiderfabrik Jobi“ (06) located across the street. Here, the ground floor level is occupied by businesses, while on each of the four residential levels Ungers arranges two apartments in mirror image. Facing the street are the living spaces, while the bedrooms face north to the back courtyard. The composition of the façade in exposed brick with reinforced concrete lintels and balcony floor slabs is a play along three planes, with the apparent voids of the horizontal band of windows on the property line proper, and the volumetric push and pull of the balconies and recessed wall planes creating the other two. At the ground floor the building has an asymmetrical composition, with the entrance to the building placed on center but countered by two sets of windows of different proportions on the left side, and two smaller windows and the vehicle entrance to the rear courtyard on the right. While the bottom level of the façade appears almost whimsical, the upper levels are quite clearly alternating bands of windows and voids, and solid brick bands protruding over the sidewalk, a pattern that will be repeated in the housing block in Köln-Niehl. This play of volumes and planes, while fairly restrained in this building, began with the infill building in Köln-Riehl and will evolve to its most elaborate investigation on the Hansaring.

08 UAA (Ungers Archiv für Architekturwissenschaften) - O.M. Ungers, 1958-59

Called a “manifesto building” by Reyner Banham, O.M. Ungers’ house explores a variety of themes including mundane ones such as resolving a corner between Belvederestraße with building form restrictions, and one without such restrictions along Quadrather Straße. In responding to these, Ungers explores the plastic use of brick masonry to create a volumetric play of pushing and pulling masses that accentuate the internal spaces, with the corner punctuated by a cylindrical one-story element hidden today by the tall hedge along the garden wall. As originally built, the house presented certain ambiguity, whether it appeared to be in process of being added to or parts being removed from it. The structure was originally a three-family house, with two flats on half of the ground floor and first level against the party wall, and the studio/office on the other half of the ground floor, with the family house on the first and second levels. It was altered once when the two flats were vacated, and again when Ungers built his new library and archives in the back garden. The house also lost some of its three-dimensional characteristics when double glazing was added flush with the walls. These changes notwithstanding, this seminal building remains one of the most significant German structures built in the early postwar period and is designated a NRW historic building.

UAA - Haus Ungers Haus ohne EigenschaftenThe “house without qualities” (Haus ohne Eigenschaften) is a late work by German architect Oswald Mathias Ungers which the architect built for his wife and himself. Constructed in Cologne in 1995, the house is considered an experiment on the reduction of architectural elements and it materializes the research on abstraction which Ungers had developed over the years; in this sense, the building can by seen as a conceptual model for a house which has been made real through building.

The house has a rectangular plan based on a classical architectural scheme, a central space and two side-aisles. It consists of two floors with five rooms, a central double-height volume and four equal rooms in the side-aisles. Crucial in the design of the plan is the thickness of the exterior and the interior walls which are used to incorporate service facilities, like stairs, toilets, the elevator, bathrooms and storage spaces. The width of the walls is always the same through the whole plan.

The façades are identical by twos, symmetrical and constructed according to specific rules of proportions, no differentiation is pursued between the front and the back and the same window/door size is employed. The plan’s geometry is not made evident in the elevations in any way. The extreme synthesis, the reduction of elements (no decoration, no hierarchy, no style) makes evident Ungers’ obsessive research for the essence of architecture, which the architect identified in the strict rules of composition.

09 Haus ohne Eigenschaften - O.M. Ungers, 1996

O.M. Ungers

After completing his studies at the TH Karlsruhe in 1950, Oswald Ma-thias Ungers opened his architectural studio in Cologne with Helmut Goldschmidt in a partnership that lasted until 1955. Early in the part-nership, Goldschmidt and Ungers realized a number of projects for various clients, be they private homes or commercial buildings. The earliest existing works by Ungers are in Cologne and are from this pe-riod, including the multifamily building on Hültzstraße and its neigh-bour, the “Kleiderfabrik Jobi“ on Aachener Straße. These two projects represent one of the formal investigations followed by O.M. Ungers, based on the pure form and a compositional clarity.

By 1955, when O.M. Ungers began his independent practice, a num-ber of his projects were housing complexes for resettled families from the eastern zone of Germany (the “SBZ-Programm“). His reputation, in projects constructed between 1955 and 1959, was of one who, given the limited resources and constraints for social housing, was still able to provide more inventive solutions than the expectations for such housing and it established Ungers as one of the leading architects in post-war Germany. These projects illustrate a second formal inves-tigation, one of interlocking volumes that finds its early manifestation in the multifamily structure in Köln-Dellbrück, and its best in the Haus Ungers Belvederestraße 60. This direction evolves into one that de-fines figural space with clear solids, first clearly seen in the two-family house, which in a way also is a reinterpretation or transformation of the pure forms of the earliest projects. These are the projects of the first phase of his professional activities.

Ungers’ trajectory shifted in the 1960s when he was appointed to the faculty of architecture at the TU Berlin (1963), later becoming its dean (1965-1967). It was a period when he did not build but instead under-took significant research as part of his teaching, work that would have a major impact in coming decades. In 1968 he and his family moved to Ithaca, New York, USA, where he assumed the chairmanship of the Department of Architecture at Cornell Univer-

sity, remaining in that capacity until 1975 though he continued to teach there and elsewhere in the USA.

Seminal competition projects from this period include his submissions for student housing at the TH Twente in Enschede, NL (1964), the German Embassy to the Holy See (1965), the Museums of Prussian Culture in Berlin (1965), and the Roosevelt Island (NYC) Housing Competition of 1974, proposals that allowed him to investigate ideas of morphology and typology. His return to Cologne in 1978 marks the beginning of his most productive phase, a period whose maturity drew from the early phase of his career, intertwined with intellectual vigor of the middle phase in Berlin and Ithaca.

10 Haus Schütte - Heinz Bienefeld, 1978

10 Haus Schütte - Heinz Bienefeld, 1978

Haus Schütte (by Antonio Ortiz)

Haus Schütte (by Antonio Ortiz)

“A calm, closed brick wall is the opposite of the potpourri of detached single houses without any spatial cohesion in a new building land.” With this sentence Heinz Bienefeld comments on the outside view of his Schütte house. He describes what is behind this wall with analogies from urban development : The entrance hall of the house is therefore like a square, the corridor is like a street, parts and peculiarities of the building interior are described as if they had urban characteristics.

In a sense, this type of representation is nothing more than one of the aradoxa so valued by Bienefeld. Because to build a barrier against the city, despite the resistance to be expected when building such a fence in a suburban residential area, and then to repeat inside the house what was previously rejected - such a concept was rightly called a paradox or even call it perversion. It is like being over-tightened a screw, too much of a good thing, perhaps comparable to his approach to the stretcher house, pushing bathroom objects out of wall openings, inserting small windows within a large window, or similar examples from other work. Here we encounter the ‘pure’ Bienefeld, comprehensive and complex with its outstanding interest in the dissection of the detail. Much more important to me is the question of whether it was really his concern to recreate a piece of the city in the Schütte house; I am not talking about the urban development in the immediate vicinity of the house, but rather the character of the historic city, as a contrast to the suburban surroundings in which Bienefeld had to erect his building. So the analogies of house and city described by him would seem appropriate.

An author’s description of his own work does not necessarily have to be accurate or exclusively valid. Let us take a look at the reproduction of the urban with all the implementation and interpretation difficulties that arise from it. The actual dialectic of the Schutte House can be seen in the search for the contrast between outside and inside, between the strict geometry of the rectangle and the irregularity inside, between the Cartesian and the romantic and thus

between the pure and simple juxtaposition of two approaches. Let us note, therefore, that behind the brick wall there was no fruitless attempt to represent the city. The wall conceals a piece of architec ture that Bienefeld only became possible after he had freed himself from the restless heterogeneity that the modern city creates. In its defensive appearance, the Schütte house clearly reveals Bi enefeld’s attitude as an architect, his longing, his striving for the mysterious and for the increasingly difficult to achieve harmony. Here we encounter his main concern and the origin of his con sciously assumed loneliness and enormous independence that made him a unique, alluring personality.

Heinz Bienefeld - Local Heroes #12 (local heroes

is a initiative of Office Winhov)

Bienefeld was born on July 8, 1926 in Krefeld. Just like Mies van der Rohe, he comes from a family of artisans. One grandfather was a silk weaver, the other a bricklayer along with his uncles, and his father was a plasterer. As a sixteen-year-old, he started working as a student for a contractor from Krefeld, who also taught the inquisitive boy to draw, and Bienefeld took the opportunity to explore the library as well. There he found a trade magazine, which had a photo of the baptistery that Dominikus Böhm built in the Gedächtniskirche in Neu-Ulm in 1925. In the photo, we can see a star-shaped wall with light coming in from above that strikes the rough surface, creating a feeling of mystery. In 1945 was taken as a prisoner of war, ending up in Cambridge, England. There, he was given the opportunity to take an architecture course. He visited all kinds of modern buildings, including the London house that Walter Gropius built for Ben Levy in 1936. Initially, he was charmed by the Modern Movement, yet he remained under the spell of Dominikus Böhm. In 1948, he returned to Germany from internment and wrote a letter of application. He received a cool rejection and was advised to do a training first. He was taking the entrance exam at the Kölner Werkschule led by Böhm. Three years later, he obtained his Meist diploma and was the only student to receive a stipend. This time, Böhm hired him in his office, and Bienefeld soon became his assistant. Böhm was primarily a church builder, and Bienefeld designed many glass windows, and developed brick facades for him.

In the office of D. Böhm, he worked a lot with hisson Gottfried Böhm. He recognized a like-minded soul in him, and they will soon become lifelong friends. In 1953 the office won the competition for the cathedral of San Salvador. For the implementation, Bienefeld was sent to the US for six months, where the construction office was located. However, the contract was withdrawn and Bienefeld took the opportunity to look at modern architecture in New York and Chicago. He became enthusiastic about SOM’s Lever House and the Lake Shore Apartments, but when he saw the Woolworth Building, the 1957 neo-gothic skyscraper by Cass Gilbert, doubt

struck. He was also impressed by a Japanese house from the 17th century that is in the MOMA, and was convinced that modern architecture can be done with wood. Once back in Cologne, he designed a house for himself with wood on steel columns, masonry discs and glass facades entirely in the style of Mies. It was never realized. For Bienefeld, his interest in the modern starts to wane. To the dissatisfaction of his associate Gotfried Böhm, he began to delve into the ancient Greek and Roman architectural styles. He investigated the construction method, dimensional proportions and spatial qualities of the classics. In the discussions at the office, Bienefeld’s unceasing search for the essence and substance of architecture is dismissed as ‘nagging’.

After the death of Dominikus Böhm in 1955, Gotfried took over the office. Bienefeld stayed there until 1958 and then worked for Emil Steffann, who is primarily known as a church builder. Steffann stood for an architecture with modest means and a preference for simple geometric shapes. Steffann did not see him as an assistant but more as an equal, and he was permitted to work out projects independently. In 1963, Bienefeld received his first major assignment, the restoration of the St. Laurentius church in Wuppertal that was burnt down during the war. So he started his own firm.

In that time he was also a teacher at the Kölner Werkschule. There he met the jeweler Wilhelm Nagel and his wife. In 1966 he built a house with a workshop for them just south of Cologne. An anachronistic villa in Roman/Palladian style, it is one of the first post-Modern houses. If Charles Jencks had been aware of this house, it would have undoubtedly been given a prominent place in his book “The Language of Postmodern Architecture”. Bienefeld himself was always horrified to be associated with the concept of post-modernism.

Bienefeld has created around forty houses, built three new churches and restored a number of them, and participated in countless competitions of which he was the prizewinner several times. Due to his refusal to make concessions, a number of these winning designs never came to fruition, and if they did, he distanced himself

from the final result. Bienefeld has spent his entire life searching for the essentials of architecture. With every assignment he actually started from scratch, resulting in an ever-evolving style. His first houses are often Palladian or Roman, and later he evolved towards more contemporary views. One of his final houses is for his children in Berlin. This house is completely contemporary in style and design.

A constant factor in all his work is the traditional attitude and his tendency towards perfectionism. He referred to himself as a ‘detail fetishist’. For almost all his assignments, he also designed the door handles and lighting fixtures, so much so that a catalogue would be compiled of all the hardware he designed.

The priority in all his designs is the careful proportioning and arrangement of spaces. For Bienefeld, proportion means ‘connecting all aspects of harmony and uniformity’. Like Bruno Taut and Le Corbusier, Bienefeld developed his own measurement system. His children speak of how their father always measured buildings on holidays in Italy. He believes the Golden Section is beautiful, but lacks character. Due to its etymology, he controversially believes, the Golden Section is overrated and over-valued by lay-people who believe they can solve everything with it. Bienefeld was an admirer of the Modular by Le Corbusier, but he found it impractical. Like Palladio, he preferred proportions over fixed sizes, proportions such as 4:3, √2:1, √3:1, and so on.

A development can also be seen in the use of materials. Initially, he emphasized the purity of materials. For example, wood is left untreated because the treatment tends destroy the original appearance, and the natural patina created by use over time adds character. “Lieber Schönheit zeitlich begrenzen als sie nie haben” - It is better to limit the beauty than to not have it at all. Paint was rare in his buildings, as he preferred to use materials in their natural color. However, he made an exception in one of his last projects, the Kortmann house, where he uses a colorful range of bright colors. Brick is used backwards, so that the conveyor belt tracks adds visual texture to the stone. This was a trick Bienefeld used often. For

floors, he re-oriented the ceramic tiles in the non-slip portions. At the Boniface church in Wildbergerhutte, he alternated layers of flat crooked stones with irregular large bricks, with fitted walls.

Welded connections are avoided as much as possible with steel structures. Beams are continuous and are not interrupted by columns. The steel parts are often assembled from several narrow profiles instead of one profile, so that they appear slimmer. He often convinces clients using silhouette drawings of window frames. When making wall openings, the glass plates are sometimes placed in grooves in the masonry or concrete, but to dramatize the view to the outside a window takes the form of a picture frame to dramatize the view to the outside.

Tragically, he was diagnosed with liver cancer and passed away on April 18th 1995, at the height of his career. At this point, he was becoming widely recognized, there was international interest in him, and he was awarded high-profile projects. His son Nikolaus Bienefeld took over the office and completed his ongoing works.

Heinz Bienefeld was the first architect to receive the grand prize of the Bund Deutscher Architekten post-humously. In 1996, A major retrospective followed in DAM. Due to the oft-extensive construction time of his projects, he was still included in the German Architecture Yearbook for four consecutive years after his death.

11 Haus Heinze-Manke - Heinz Bienefeld, 1984

11 Haus Heinze-Manke - Heinz Bienefeld, 1984

Haus Heinze-Manke (a house like a city by Manfred Speidel)

The plan for the Heinze and Manke semi-detached house was clear from the start: The Manke house was to contain three rental apartments, each with separate entrances. A six-meter-deep long building with a gable roof and largely glazed long side, which required a corresponding distance from the neighboring border, was suitable for this. He turns away from the Heinze single-family house, which - largely turned inward - forms an inner courtyard with three rocks of different depths, with the back wall of the Manke house closing off the courtyard.

The semi-detached house is something like the test of Bienefeld’s design method. By dividing it into narrow-gabled house units, which enable the gable and eaves to be changed, it achieves a convincing, structurally coherent assembly of different spatial typologies that could at the same time form the urban element of a spatially merging settlement. This also includes the paved forecourt with the acacia trees planted like an avenue, which divide the public space into the street and intermediate area.

In the clearly worked out contrast of closed walls made of wide-jointed bricks and open roof trusses, a far extended roof and glazed apartments, not only exemplary basic forms of the architecture are formed - such as the thin roof, which rests on trusses that carry their loads on pillars -, but also the variety of ways of life that are part of our existence today is interpreted: living in closed, fixed rooms or in open, ambiguous in the transition from the inside to the outside under a tent-like, light roof like in a Japanese house.

The transition from the closed to the open house, exposed in its elements, so to speak dissected, reminds me of Carlo Scarpa’s inimitably beautiful conversion of the Verona Castel Vecchio, where a thin roof, supported by slender iron structures, continues the closed building of the castle wall and turns it into a fragment a new This creates an open space that provides space and air for a significant equestrian sculpture. In a different way, the garden side of the Heinze-Manke assembly forms an image of freedom and order

in the folds of the gable, eaves and bay-like protruding gable, a chain-like development that evokes the image of architecturally beautiful, rural villages that Emil Steffann created had noticed and drawn and which already served as a model for him. It is important to remember, not so much to prove the origin of the pictures, but rather, in the sense of Bienefeld and Steffann, not to forget these cornerstones of our architectural culture, which both did not become fashionable to reactivate.

The Heinze house should be examined more closely. The long hall and inner courtyard are the organizing center of its layout. They separate and connect the dining room such as the kitchen on the street side and the living room in the garden as well as the children’s and parents’ rooms on the upper floor. This simple, symmetrical arrangement is transformed in a number of ways into a magnificent and differentiated sequence of rooms. The hallway and the corridors that mediate between the courtyard and the rooms, plastered to unify them, created a multi-layered, rhythmically structured room that continues in the massive walls with door openings that are extended in relief in the living room by niches. The entrance in the axis of the transverse hall and courtyard forms with the latter a middle level between the street and the lower garden. Steps led the slope topography right through the hall and inner courtyard. The narrow two-story entrance hall is also the anteroom of the courtyard. With deep, two-storey brick pillars protruding in front of the glass wall, it forms a solemn room in its barreness. The opening to the sky above the circumferential edge of the eaves is proportioned in such a way that - like above the oculus of the Pantheon - the clouds moving in front of it appear as a framed picture, a phenomenon that the beehive field repeatedly brings with it tried to reach a construction.

The living room - largely closed in effect by wide pillars between tall glass ores - nevertheless lives from the tension between the courtyard and the garden. Between the pillars of the courtyard and the wall, a gallery-like intermediate area remains on the same level, a kind of suggested anteroom to the courtyard, while the room is suddenly oriented towards the garden with a large, portal-like

12 Haus Stupp - Heinz Bienefeld, 1977

12 Haus Stupp - Heinz Bienefeld, 1977

13 Haus Pahde - Heinz Bienefeld, 1972

13 Haus Pahde - Heinz Bienefeld, 1972

Haus Pahde (form as an idea to preserve an idea bv Vittorio Magnago Lampugnani)

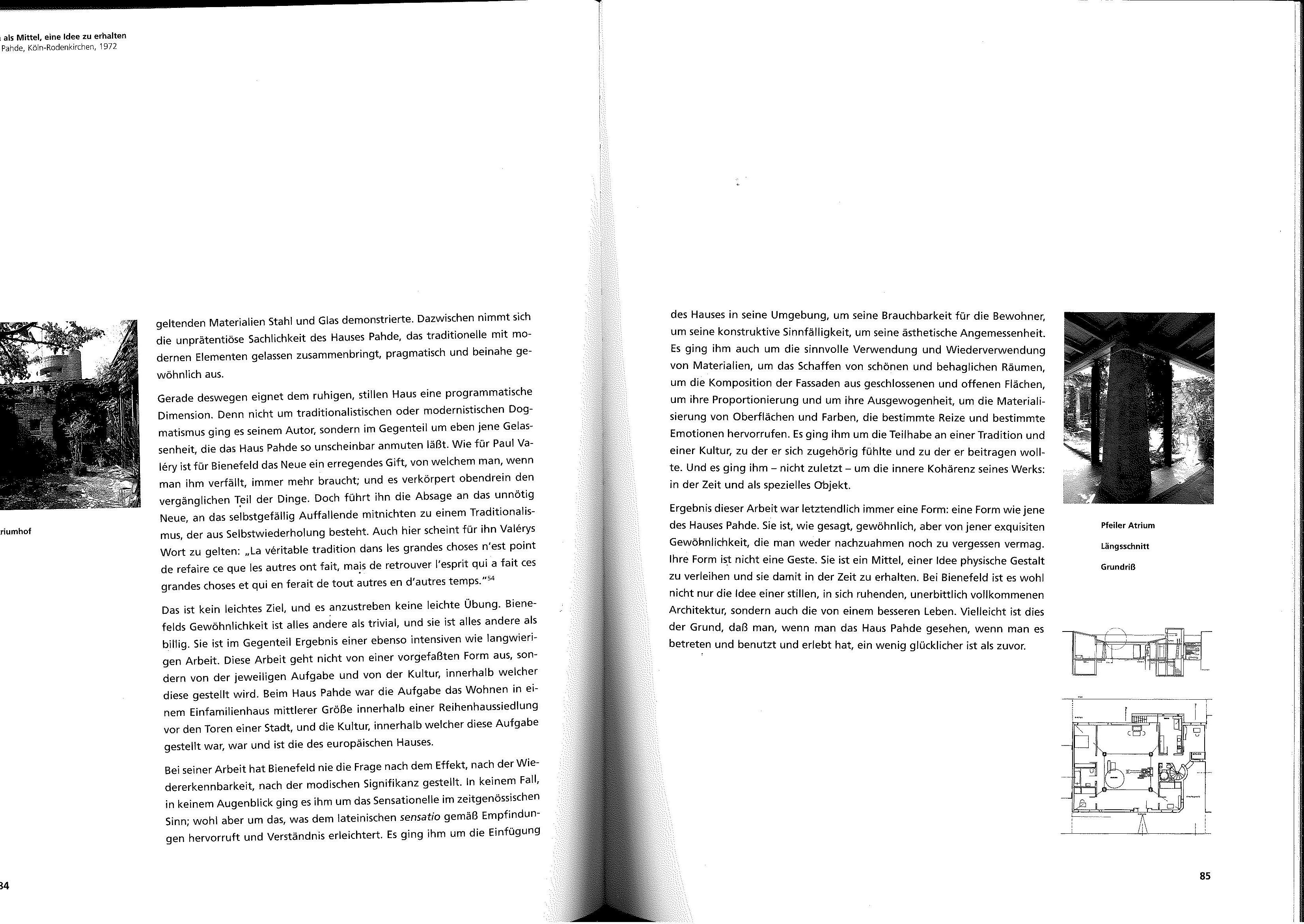

The house is hardly noticeable. It stands in a suburb of Cologne in a row of single-storey terraced houses, the building line and heights are precisely respected. The façade, made of brick masonry that has been left visible, is connected to that of the neighboring building only through two different incisions. It is almost completely closed and only two square windows, an equally square peephole and a narrow high door opening structure it in a restrained and inconspicuous way.

When entering, one waits for a simple sequence of rooms, which is arranged around a rectangular atrium - four brick pillars, which taper towards the top, support a circumferential wooden beam on which inward sloping pent roofs lie. Brick-colored hourdis plates are placed between the rafters that have been left visible. The inner walls consist of the light brick masonry like the outer facades. The floor is a split brick screed in which small, square, white marble stones are inlaid; In the kitchen and bathroom, old floor panels made from demolition material have been reused. Virtually all of the space-defining elements are made of the same material, which is simply processed in a different way. The result is an amazing uniformity, contributes to the calm spatial effect of the clearly cut and simply joined rooms.

The house is hardly noticeable not only in its urban (or, better, suburban) surroundings, but also in the oeuvre of the architect whose signature it bears. In Heinz Bienefeld’s work, the Pahde house is not a prominent building. This is more the case for the Nagel house in Wesseling-Keldenich, with which Bienefeld four years earlier heralded a simultaneously opulent and ascetic revival of the ancient Roman building tradition, or for the Dominick house in Walberberg, with which he is touring Surprise of all those who had accused him of lavish nostalgia, the disenchanted use of the commonly considered ‘modern’ applicable materials steel and glass demonstrated. In between, the unpretentious objectivity of the Pahde house, which calmly combines traditional with modern elements, appears pragmatic and almost ordinary.

This is precisely why the quiet, quiet house has a programmatic dimension. For his author was not concerned with traditionalist or modernist dogmatism, but on the contrary, it was precisely that serenity that makes the House of Pahde seem so inconspicuous. As for Paul Valery, for Bienefeld the new is an exciting poison, of which one needs more and more when one falls for it; and on top of that it embodies the past part of things. But the rejection of the unnecessarily new, of the self-obsessive, by no means leads him to a traditionalism that consists of self-repetition. Here, too, Valery’s word seems to apply to him: “La véritable tradition dans les grandes choses n’est point de refaire ce que les autres ont fait, mais de retrouver l’esprit qui a fait ces grandes choses et qui en ferait de tout autres en d’autres temps.

It is not an easy goal, and striving for it is not an easy exercise. Bienefeld’s habit is anything but trivial, and it is anything but cheap. On the contrary, it is the result of intensive and lengthy work. This work does not start from a preconceived form, but from the respective task and the culture within which it is set. With the Pahde house, the task was to live in a medium-sized single-family house within a row of houses at the gates of a city, and the culture within which this task was set was and is that of the European house.

In his work, Bienefeld never asked about the effect, about recognizability, about fashionable significance. In no case, in no moment was he concerned with the sensational in the contemporary sense; but probably about that which, according to the Latin sensatio, evokes feelings and facilitates understanding. It was about the insertion of the house in its surroundings, its usefulness for the residents, its constructive sensibility, its aesthetic appropriateness: he was also concerned with the sensible use and reuse of materials, the creation of beautiful and comfortable rooms, and the composition of the facades closed and open surfaces about their proportions and their balance, about the materialization of surfaces and colors that evoke certain stimuli and certain emotions. It was about participating in a tradition and a culture to which he felt he belonged and to which he wanted to contribute. And it was - not least - about the inner coherence of his work in time and as a

Ultimately, the result of this work was always a shape: a shape like that of the House of Pahde. As I said, it is ordinary, but of that exquisite habit which one can neither imitate nor forget. Your shape is not a gesture. It is a means of giving an idea physical form and thus of maintaining it in time. With Bienefeld it is probably not just the a quiet, self-contained, relentlessly perfect architecture, but also that of a better life. Perhaps this is the reason that when you have seen the House of Pahde, when you see it entered and used

14 Am Kölner Brett - Brandlhuber, 1997-2000

Am Kölner Brett

Am Kölner Brett

With the rise of private television programs in late 1990s Germany, the city of Cologne experienced a growing demand for alternative, modern work-live arrangements. Ehrenfeld, a former mixed use neighborhood with its industrial warehouses, houses, and carefree environment, met the demands of the creators and freelance professionals who were looking for spaces to live and work under the same roof. Despite the high demand for mixed use spaces in the spirit of loft apartments, their availability was very low. The client therefore commissioned the design of a “new loft” building on the property of Messing Müller, a long-standing craft business. The name Kölner Brett, as the street and building are also called, comes from a three-track curtain rail that is pre-assembled on a wooden board. The idea behind this configurable invention is adopted in many aspects of the building design, most notably in the exterior circulation and terraces. The building provides twelve individual dwellings, each consisting of two connected boxes: one upright double-height space and another horizontal single-height one. The L-shape of these two main zones makes several adjustments and extensions available to the users, including the possibility of joining neighboring units into an even larger space. The L-form also creates spatial continuity while differentiating functions. The apartments can be accessed via an exterior circulation system, hanging from the building like an oversized vendor’s tray, evoking the flexibility of the Kölner Brett. This facilitates the internal adaptability, reflecting the site’s ongoing urban development as a former commercial and industrial area in constant transition with uncertain ends. The external platforms and staircases also offer the building a non-city-like quality of a multilevel front garden. The interiors are characterized by the raw concrete walls and heavy oak floors; the absence of partition walls allows the user to individually configure the space. This idea of free use and self-development is also true for the bathroom and kitchen facilities since the only preinstalled elements are the shafts. The units are glazed on both the north and south sides, which emphasizes a sense of uninterrupted interior space.

The facade consists of reinforced fiberglass elements that cover the concrete surfaces with greenish reflections. The modular concept of the project was adapted by the German electronic postrock trio To Rococo Rot for an LP entitled Kölner Brett released by Staubgold records. This followed the idea that the building—and architecture more generally—can connect with other disciplines,

Dönges - Brandlhuber, 2003

16 Stavenhof - Brandlhuber, 1999-2000

16 Stavenhof - Brandlhuber, 1999-2000

Appartement and office building - Brandlhuber, 1996-97

18 Atelier and courtyard house - Brandlhuber, 1997-2000

18 Atelier and courtyard house - Brandlhuber, 1997-2000

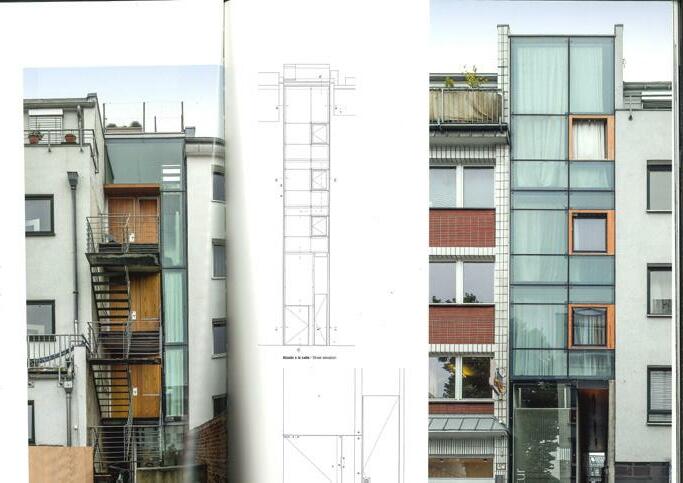

The living and working space on Geisselstraße addresses the array of legal conditions while generously providing a sequence of 360 light-flooded square meters on the extremely long and narrow plot. The volume closest to the street contains a three-story house with living quarters and the client’s atelier; at the rear there is a two-story garden house for their children. The two units are connected via a separable single-story link that contains shared spaces such as kitchens and bathrooms. The building’s irregular shape and connected volumes therefore make full use of this infill site. The building is understood as a living and working space which, despite the neighborhood’s high density, is still able to provide green and outdoor areas of varying sizes by using the terraces, roof garden, ground floor garden, and inner courtyard, which are in constant dialogue with the interior. The concrete structure is clad using two facade systems: the atelier is covered in multi-layered polycarbonate sheets and aluminum louver windows, while the garden house has an insulated glass facade with sliding wood elements.

19 St. Mechtern - Rudolf Schwarz, 1974-54

19 St. Mechtern - Rudolf Schwarz, 1974-54

20 St. Anna - Dominikus + Gottfried Böhm, 1954-56

20 St. Anna - Dominikus + Gottfried Böhm, 1954-56

16 Dominium - Hans Kohllhoff, 2009

17 Museum für Angewandte Kunst - Rudolf Schwarz&Josef Bernard, 1957

Museum für Angewandte Kunst

In 1957 some pioneering buildings were completed in Cologne, the previous buildings of which had been destroyed in the Second World War. This not only included the reception hall of the main train station, but also two of the most important cultural buildings in the city: the opera house on Offenbachplatz with its architect Wilhelm Riphahn and the Wallraf-Richartz-Museum, built by Rudolf Schwarz and Josef Bernard, which has been home to the museum since 1989 for applied arts Cologne is. As Rudolf Schwarz put it, “modestly built to last”, the museum building occupied an important position between the traditional and the modern. The building is still one of Cologne’s architectural icons today.

The building complex built on the former site of the Minorite Monastery, which was demolished in 1855, is built directly onto the preserved medieval Minorite Church as a four-wing complex around a central courtyard and thus consciously takes on the floor plan and the architectural appearance of the monastery complex. In addition, parts of the cloister were integrated into the complex. The inner courtyard, an oasis in the city center, with the fountain by the painter and sculptor Ewald Mataré (1887-1965) still conveys the contemplative idea of the cloister. This fountain with the sculpture of an angel with a painting palette was created as part of the competition for the 500th anniversary of Stefan Lochner’s death. The fountain (1953-1956) is just as much a part of the original equipment program as the pillars and beams, also designed by Mataré, which emphasize the window facade on the north side of the inner courtyard.

The three-storey brick building is strongly structured vertically with pilaster strips, rows of windows and parallel pointed gable roofs. The outwardly extremely simple and closed-looking building only reveals its cathedral-like effect after one has humbly stepped through the low entrance foyer in accordance with Rudolf Schwarz’s intention. The interior of the room is dominated by the central main hall with the open staircase and the galleries that lead to the exhibition rooms with impressive skylight halls.

The Museum of Applied Arts has been located in the building of the former Wallraff-Richartz Museum since 1989. This was built from 1953-57 to replace the previous building destroyed in the war on the same site.

The architects Rudolf Schwarz and Josef Bernhard created a clear, block-like structure that stands out from the neighboring Minorite Church. Red brick, interrupted by light window parapets, forms the facade. Five roof gables, alternately made of glass and brick, determine the structure of the building.

The entrance area is cautiously laid out, behind which the high and wide hall opens up a view of the square inner courtyard and the side wall of the Minorite Church. A spacious staircase in three steps climbs up from the two-story hall to the main floor.

When the Wallraff-Richartz Museum moved to a new building in 1986, the architect Walter von Lom carefully adapted the building for the collections of the Museum of Applied Art.

18 Kolumba Museum - Peter Zumthor, 2007

18 Kolumba Museum - Peter Zumthor, 2007

Kolumba

Although our lives take place everywhere, we remember some places in particular. One such place is Kolumba in Cologne’s city centre. A secret garden, stone ruins, a uniquely dense archaeological site: the ruins of the gothic church in the centre of rebuilt Cologne are the most impressive symbol of the city’s almost complete destruction during the Second World War. In 1949 the chapel of “Madonna in the Ruins” was created within the church ruins by the architect Gottfried Böhm as a near improvised shelter for a gothic Mary figure that had remained unscathed. Kolumba is intended to be a place for reflection. The occasion is the new building for the Cologne Diocese Museum, which was established in 1853 and which features an extraordinary collection spanning from early Christianity to contemporary art. A museum as a garden continually bringing a few alternately selected works of art to bloom. The guiding thread of the collection is the quest for overarching order, measure, proportion and beauty which connects all creative work. This quest is the precious material for an aesthetic laboratory which studies the anthropological connections lying beyond mere chronology. Kolumba allows visitors to immerse themselves in the presence of their memories and offers them their own experiences on their way.

As a “living museum” Kolumba enquires about the freedom of the individual in an exchange between history and the present day, at the intersection of belief and knowledge, and defends existential values by challenging them through art. The new building designed by Peter Zumthor transfers the sum of the existing fragments into one complete building. In adopting the original plans and building on the ruins, the new building becomes part of the architectural continuum. The warm grey brick of the massive building unite with the tuffs, basalt and bricks of the ruins. The new building develops seamlessly from the old remains whilst respecting it in every detail. In terms of urban planning, it restores the lost core of one of the once most beautiful parts of Cologne’s city centre. Inside the building a peaceful courtyard takes the place of a lost medieval cemetery. The largest room of the building encompasses the two thousand year structure of the city as an uncensored memory

landscape. Its “filter walls” create air and light permeable membranes which contain within them the functionally independent chapel. The chapel is removed from the changing cityscape and given a final location, in which it will be assured a dignified continuing existence. Located above – carried by slim columns, which gently prod the archaeological excavation like needles – is an exhibition floor. Its spatial structure was similarly developed from the idiosyncratic ground plan. It connects seamlessly to the northern building part, which – as a completely new building – will house further exhibition rooms and the treasury as well as the stairway, foyer, museum entrance and the underground storage areas. The sixteen exhibition rooms possess the most varying qualities with regard to incoming daylight, size, proportion und pathways. What they all have in common is the reduced materiality of the brick, mortar, plaster and terrazzo in front of which will appear the works of art. Kolumba will be a shadow museum which will evolve only in the course of the day and the seasons. Some of the wall-sized windows allow daylight to penetrate from all directions. The steel frames decorate the brick coat like brooches and segment the monumental facade. Though respectful of the location and the seriousness of its contents, Kolumba will emanate serenity and an inviting cheerfulness.

19 Wallraf-Richartz-Museum - O.M. Ungers, 1966-2001

19 Wallraf-Richartz-Museum - O.M. Ungers, 1966-2001

This building is the result of a architectural design competition. The site of the new Museum is the boundary of the historic Gürzenich complex towards the Rathausplatz. The Gürzenich complex consists of the gothic hall structure with various postwar additions and the ruined Church of St. Alban. This complex shows interventions by the famous architect Rudolf Schwarz. The focus of the competition was the approach to this heterogeneous architectural composition and the historic surroundings of the Rathausplatz.

The proposal by Oswald Mathias Ungers envisioned the division of the intendend building mass in two volumes. One building is adapted to the surroundings and integrated into the cleft in the existing buildings. The second volume is freestanding, and the juncture between the two building volumes occupies the site of a historic street. This juncture contains the circulation of the museum and is considered to be a revival of the circulation area. The new Wallraf-Richartz-Museum is now an augmetation and completion of the Gürzenich complex.

The entire exhibition area is accomodated in the main building on the Rathausplatz, while the other building colume houses the subsidary spaces. The exhibition area is conceived to allow a high degree of flexibility. The permanent collection is in the spaces of the first to third floors. The spaces of the first and second stories are illuminated by a high sidelight, while the exhibition spase on the third story is lit by skylights. The temporary exhibition is located in the basement level. This space has a separate access from the entrance hall.

Wallraf-Richartz-Museum

20 Gürzenich-Block - Rudolf Schwarz

20 Gürzenich-Block - Rudolf Schwarz

Rudolf Schwarz is of course best known for his church buildings. A building type where he developed throughout his life. Yet he thought that an architect couldn’t just build churches. He would thereby placing them outside society. The oeuvre of Schwarz is indeed broad. The museum and the reconstruction of the Gürzenich banquet hall in Cologne are there examples of. He made a large number of urban plans and was even Generalplaner for a long time the city of Cologne. The center of gravity, however, was clearly at churches and related programs. Already in the twenties he was interested in the architecture of the church. Right before the war he wrote the book ‘Vom Bau der Kirche’ (1938) with a completely new vision on the construction of churches. Schwarz’s writings are considered to be among the most important theoretical works on modern church building. He did not use the writing to grant his buildings clarify or explain. He has the word, just like the stone of his churches, used as an instrument to express his vision to wear. In addition, he was extremely interested in building technology. Reissues of the by Schwarz written ‘Kirchenbau, Welt for der Schwelle’ (1960) and ‘Wegweisung der Technik’ (1929) are still for sale.

These are in-depth investigations into the typology of the church building would take off like that after the war no one could have foreseen. In the post-war era, Germany was the country of great doubt, and crisis of the identity. Until then, Catholic church buildings were often grand and monumental. Built to handle the crowd impress. But the memory of the manipulation of the masses during the war were fresh in their minds of the citizens. The Catholic Church realized that it church building had to be redesigned. During the centuries before, the visitor had become spectator. After the war, within the Catholic Church more and more sounds that the crowd is up again community should be. Rudolf Schwarz was already then one of the architects who developed the typology of the Catholic church building and gave faith a new home. In the decades after the war, many churches, including in Netherlands, to get a new organization around the renewed liturgy.

Rudolf Schwarz by local heroesHowever, Schwarz was not only looking for a expression of the liturgy. He wanted a different experience express, the mystical. He always had this elusive goal in focus.

He built his first church building in 1930 and is curiously the most radical, the Fronleichnamskirche in Aachen. You could also say the most modern, the word Schwarz hated so much. Whoever enters here takes a breath. The church hall is high, empty and undecorated. The wall behind the altar is not painted, does not represent a –for the living unattainable - afterlife. He is white in his immense greatness. Rudolf Schwarz described it as follows: “here is nothing more than the silent presence of the Church and Christ.” It was the start of a long series of church designs. A lifelong quest, in which not being modern or innovative was paramount, but the quest for the right expression of space and the material.